Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Druckman in Keren

Druckman in Keren

Uploaded by

Chryssy AngelCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Druckman in Keren

Druckman in Keren

Uploaded by

Chryssy AngelCopyright:

Available Formats

Whats It All About?

: Framing in Political Science*

by

James N. Druckman

Payson S. Wild Professor

druckman@northwestern.edu

Department of Political Science

Northwestern University

!" University Place

#vanston$ %& !'!(

Phone) (*+,*-",+*.!

Fax) (*+,*-",(-(.

/ctober '0$ '!!-

1o appear in 2ideon 3eren$ ed.$ Perspectives on Framing. New 4ork) Psycholo5y

Press 6 1aylor 7 8rancis.

9% thank Denis :ilton and 2ideon 3eren for e;tremely helpful comments$ and Samara

3lar and 1homas &eeper for research assistance.

:ow do people form preferences< 1his =uestion is fundamental for social

scientists across disciplines. Psycholo5ists seek to understand how people think$ feel$ and

act$ and preferences often reflect or determine these activities. Sociolo5ists e;plore how

preferences stem from and impact social interactions. #conomists$ particularly in li5ht of

the trend towards behavioral economics$ often study the causes and conse=uences of

preferences that deviate from well,defined$ self,interested motives. Political scientists$ for

whom citi>ens? preferences serve as the basis for democratic 5overnance$ investi5ate the

roots of political preferences as well as the e;tent to which 5overnin5 elites respond to

and influence these preferences.

%n some ways$ there is fruitful inter,disciplinary collaboration on understandin5

the causes and conse=uences of preferences@ in other ways$ cross,discipline

communication is lackin5. Aoth these perspectives are apparent when one considers the

idea of Bframin5.C 8ramin5 receives substantial attention across the social sciencesDfor

many$ it plays an important role in e;plainin5 the ori5ins and nature of preferences. 4et$

Bframin5C continues to be used in different and sometimes inconsistent ways across Eand

even withinF disciplines. 8or e;ample$ some reserve it to refer to semantically distinct but

lo5ically e=uivalent portrayals$ such as -.G unemployment versus .G employment$

while others employ a rela;ed definition that includes emphasis on any alternative

consideration Ee.5.$ economic concerns versus humanitarian concerns when thinkin5

about welfareF. %n short$ althou5h more than a decade old$ Nelson$ /;ley$ and Hlawson?s

E"--+) '''F claim that the Bhei5htened interest in frames... conceals a lack of conceptual

clarity and consistency about what e;actly frames areIC still seems accurate Ealso see

8a5ley and Jiller "--+) 0.+$ 3Khber5er "--($ &evin$ Schneider$ and 2aeth "--() "."$

'

Druckman '!!"a) '','0"$ '!!*$ JcHombs '!!*) (-$ Sniderman and 1heriault '!!*F.

%n this chapter$ % attempt to reduce this conceptual ambi5uity. % be5in by offerin5

a simple model of preference formation that makes clear e;actly what frames are and

how they mi5ht work. 1his enables me to draw a distinction between prominent usa5es of

the framin5 concept. % then focus on a particularly relevant conceptuali>ation used in

political science. % review work that shows how political elites Ee.5.$ politicians$ the

mediaF en5a5e in framin5$ and how these frames influence political opinion formation. L

brief summary concludes.

What Is A Frame?

1o e;plain what framin5 is$ % be5in with the variable of ultimate interest) an

individual?s preference. L preference$ in essence$ consists of a rank orderin5 of a set of

obMects or alternative actions. 8or e;ample$ an individual mi5ht prefer the socialist party

to the environmental party to the conservative party$ the immediate withdrawal of forei5n

troops in %ra= to piecemeal withdrawal$ a defined benefit retirement pro5ram to a defined

contribution one$ or chocolate ice cream to vanilla to strawberry. %n some definitions$

particularly those used by economists$ the rank orderin5s must possess specific properties

includin5 transitivity Ee.5.$ if one prefers chocolate to vanilla$ and vanilla to strawberry$

then he6she must prefer chocolate to strawberry tooF and invariance where different

representations of the same choice problem should yield the same preference Ee.5.$ a

person?s preference should not chan5e if asked whether he6she Bprefers chocolate to

vanillaC as compared to bein5 asked if he6she prefers Bvanilla to chocolateCF E1versky

and 3ahneman "-(+F.

Preferences over obMects derive from comparative evaluations of those obMects

0

E:see "--F@ for e;ample$ an individual prefers the socialist party to the conservative

party if he6she holds a relatively favorable evaluation of the socialists EDruckman and

&upia '!!!F. Social psycholo5ists call these comparative evaluations attitudes$ which is

Ba person?s 5eneral evaluation of an obMect Ewhere NobMect? is understood in a broad

sense$ as encompassin5 persons$ events$ products$ policies$ institutions$ and so onFC

E/?3eefe '!!') F. %t is these evaluations Ei.e.$ attitudesF that underlie preferences.

L common portrayal of an attitude is the e;pectancy value model Ee.5.$ LM>en and

8ishbein "-(!$ Nelson$ /;ley$ and Hlawson "--+F where an attitude toward an obMect

consists of the wei5hted sum of a series of evaluative beliefs about that obMect Ethis

portrayal is akin to utility theoryF. Specifically$ Attitude = v

i

*w

i$

where v

i

stands for the

evaluation of the obMect on attribute i and w

i

stands for the salience wei5ht EOw

i

P "F

associated with that attribute. 8or e;ample$ one?s overall attitude$ A$ toward a new

housin5 development mi5ht consist of a combination of ne5ative and positive

evaluations$ v

i$

of the proMect on different dimensions i. Ln individual may believe that

the proMect will favor the economy EiP"F but harm the environment EiP'F. Lssumin5 this

individual places a positive value on both the economy and the environment$ then v

1

is

positive and v

2

is ne5ative$ and his attitude toward the proMect will depend on the relative

ma5nitudes of v

1

and v

2

discounted by the relative wei5hts Ew

1

and w

2

F assi5ned

respectively to each attribute ENelson and /;ley "---F.

1he 5eneral assumption of the e;pectancy value model that an individual can

place different emphases on various considerations about a subMect serves as a useful

abstraction for discussin5 framin5. 1his conceptuali>ation applies to any obMect of

evaluation Eand$ thus$ any set of obMects over which individuals have preferencesF. 8or

*

instance$ a voter?s attitude toward a party may depend on whether the voter favors the

party on dimensions such as platform issues and leadership that are of varyin5

importance Ee.5.$ economic issues may be seen as bein5 more important than forei5n

affairs and leadership e;perienceF Esee #nelow and :inich "-(*F. 1he voter mi5ht prefer

one party Ee.5.$ conservativesF when the evaluations are based on forei5n affairs Ee.5.$

forei5n affairs receives considerable wei5htF but another when based on economic

considerations Ee.5.$ socialistsF. Ls another e;ample$ the e;tent to which an individual

assi5ns blame to a welfare recipient may depend on evaluations of the recipient?s

personal efforts to stay off of public assistance Edimension "F and the situational factors

that the recipient has faced Edimension 'F Esee %yen5ar "--"F. Similarly$ one?s tolerance

for a hate 5roup rally may hin5e on the perceived conse=uences of the rally for free

speech$ public safety$ and other values$ with each value receivin5 a different wei5ht. 8or

these e;amples$ if only one dimension matters$ the individual places all of the wei5ht Ew

i

P "F on that dimension in formin5 his attitude. Without loss of 5enerality$ i

can be thou5ht

of as a dimension EQiker "--!F$ a consideration ERaller "--'F$ a value ESniderman "--0F

or a belief ELM>en and 8ishbein "-(!F.

1he dimension or dimensionsDthe Bi?sCDthat affect an individual?s evaluation

constitute an individual?s frame in thought. 1his is akin to 2offman?s E"-+*F depiction of

how frames or5ani>e e;periences or Johnson,&arid?s E"-(0F mental model. %f an

individual$ for e;ample$ believes that economic considerations trump all other concerns$

he6she would be in an BeconomicC frame of mind. /r$ if free speech dominates all other

considerations in decidin5 a hate 5roup?s ri5ht to rally$ the individual?s frame would be

free speech. %f instead$ he6she 5ave consideration to free speech$ public safety$ and the

.

effect of the rally on the community?s reputation$ then his6her frame of mind would

consist of this mi; of considerations. 1he e;amples 5iven thus far constitute what

scholars call BemphasisC frames$ BissueC frames$ or BvalueC frames. 8or these cases$ the

various dimensions of evaluation are substantively distinctDthat is$ one could reasonably

5ive some wei5ht to each consideration such as free speech and public safety or the

economy and forei5n affairs. 1he varyin5 wei5hts placed on the dimensions often play a

decisive role in determinin5 overall attitudes and preferences Ee.5.$ more wei5ht to free

speech leads to more support for the rallyF.

Lnother type of frame is Be=uivalencyC or BvalenceC frames. %n this case$ the

dimensions of evaluation are identical@ this typically involves castin5 the same

information in either a positive or ne5ative li5ht E&evin$ Schneider$ and 2aeth "--()

".!F. 1he most famous e;ample is 1versky and 3ahneman?s E"-("F Lsian disease

problem. 1his problemDwhich is described in detail in the introductory chapterDshows

that individuals? preferences shift dependin5 on whether e=uivalent outcomes are

described in terms of the number of lives saved out of !! Ee.5.$ '!! are savedF as

opposed to the number of lives lost Ee.5.$ *!! are lostF. Lnalo5ous e;amples include more

favorable evaluations of an economic pro5ram when the frame EdimensionF is the

employment rate rather than the unemployment rate$ a food product when the frame is the

percenta5e fat free rather than the percenta5e of fat$ and a crime prevention pro5rams

when the frame is the percenta5e not committin5 crime instead of the percenta5e of

criminals Ee.5.$ &evin$ Schneider$ and 2aeth "--($ PiSon and 2ambara '!!.$ /?3eefe

and Jensen '!!F. Qelated to e=uivalency or valence framin5 effects are =uestion

wordin5 effects in surveys Esee Druckman '!!"a$ Aartels '!!0 for discussionF.

Unlike emphasis or value frames$ the dimensions in e=uivalency frames are not

substantively distinct and are in fact lo5ically e=uivalent. 1hus$ one?s evaluation should

not inherently Eor ideallyF differ based on the dimension of evaluation Ee.5.$ one should

not chan5e his6her evaluation of an economic pro5ram when he6she thinks about it terms

of -.G employment instead of .G unemploymentF. 1he fact that preferences tend to

differ reflects co5nitive biases that also violate the aforementioned invariance a;iom of

preference formation.

%n sum$ a frame in thou5ht can be construed as consistin5 of the dimensions on

which one bases his6her evaluation of an obMect. 1hese dimensions involve either

substantively distinct considerations Ei.e.$ emphasis framesF or lo5ically e=uivalent ones

Ei.e.$ e=uivalency framesF. %n both cases$ the frame leads to alternative representations of

the problem and can result in distinct evaluations and preferences.

Frames in Communication

1he frame that one adopts in his6her mind Ee.5.$ the dimensions on which

evaluations are basedFDand that$ conse=uently$ can shape preferencesDstems from

various factors includin5 prior e;periences$ on5oin5 world events$ and so on. /f

particular relevance is the impact of communications from others includin5 friends and

family$ and in the case of politics$ politicians and the media. %n presentin5 information$

speakers often emphasi>e one dimension or another@ in so doin5$ they offer alternative

frames in communication. 8or e;ample$ if a speaker$ such as news outlet$ states that a

hate 5roup?s planned rally is Ba free speech issue$C then the speaker invokes a Bfree

speechC frame Eemphasis framesF. Llternatively$ in describin5 an economic pro5ram$ one

can emphasi>e its conse=uence for employment or unemployment Ee=uivalency framesF.

+

8rames in communication and frames in thou5ht are similar in that they both

concern variations in emphasis or salience Esee Druckman '!!"bF. :owever$ they differ

with the former usa5e focusin5 on what a speaker says Ee.5.$ the aspects of an issue

emphasi>ed in elite discourseF$ while the latter usa5e focusin5 on what an individual

thinks Ee.5.$ the aspects of an issue a citi>en thinks are most importantF Ealso see #ntman

"--0F. %n this sense$ the term frame refers to two distinct$ albeit related entities@ as 3inder

and Sanders E"--) "*F e;plain$ Bframes lead a double lifeI frames are interpretative

structures embedded in political discourse. %n this use$ frames are rhetorical weaponsI

Lt the same time$ frames also live inside the mind@ they are co5nitive structures that help

individual citi>ens make sense of the issuesIC When a frame in communication affects

an individual?s frame in thou5ht$ it is called a framing effect.

When it comes to studyin5 frames in communication and concomitant framin5

effects$ a few clarifications are in order. 8irst$ it makes sense to define a frame in

communication as a verbal or non,verbal statement that places clear emphasis on

particular considerations Eon non,verbal frames$ see 2rabe and Aucy '!!-$ %yen5ar

'!"!F. /ther types of communications that do not e;plicitly hi5hli5ht a consideration

Ee.5.$ a factual statement such as Ba hate 5roup has re=uested a permit to rallyCF may still

affect individuals? frames in thou5ht$ but such an effect does not make the statement a

frame in communication Ei.e.$ the speech act should not be defined based on its effectF

Esee Slothuus '!!( for a more 5eneral discussionF. 8rames in communication sometimes

will and sometimes will not influence individuals? frames in thou5ht. 8or e;ample$ a free

speech activist or a Mournalist who possesses stron5 beliefs in free speech are unlikely to

be influenced by a public safety frame when it comes to a hate 5roup rallyDin other

(

words$ such individuals have clearly defined prior beliefs that prevent a frame in

communication from e;ertin5 an effect Ealso see$ e.5.$ 8urnham "-(' on how values

condition attributionsF.

Second$ many scholars employ the concept of frames in communication to

analy>e trends in elite discourse. 8or e;ample$ 2amson and Jodi5liani E"-(+F show that$

over time$ opponents of affirmative action shifted from usin5 an undeserved advanta5e

frame to a reverse discrimination frame. 1hat is$ the discourse chan5ed from =uestions

such as Bhave Lfrican Lmericans earned or do they deserve special ri5hts<C to the

=uestion of Bis it fair to sacrifice the ri5hts of whites to advance the well,bein5 of Lfrican

Lmericans<C Lnalo5ous e;amples include studies on support for war Ee.5.$ Dimitrova$

3aid$ Williams$ and 1rammell '!!.F$ stem cell research ENisbet$ Arossard$ and 3roepsch

'!!0) *(F$ cynicism toward 5overnment EArewer and Si5elman '!!'F$ and the obesity

epidemic E&awrence '!!*F. 1hese analyses provide insi5ht into cultural shifts ESchudson

"--.$ Qichardson and &ancendorfer '!!*) +.F$ relative media biases E1ankard '!!"F$ and

public understandin5 EAerinsky and 3inder '!!F. 8or now$ however$ % turn to a

discussion of how frames in thou5ht e;ert their effects on attitudes$ as this provides

insi5ht into when a frame in communication will influence one?s preference. E%n what

follows$ % do not re5ularly distin5uish frame Bin thou5htC from those Bin communicationC

as it should be clear from the conte;t to which % am referrin5.F

Psychology of Frames in Thought

1he conceptuali>ation of frames in thou5ht as constitutin5 the dimensions on

which one bases his6her attitudes leads strai5htforwardly to a psycholo5ical model of

framin5 EHhon5 and Druckman '!!+aF. 1he startin5 point is that individuals typically

-

base their evaluations on a subset of dimensions$ rather than on the universe of possible

considerations Ee.5.$ LM>en and Se;ton "---F. Lt the e;treme$ they focus on a sin5le

dimension such as forei5n policy or economic affairs in evaluatin5 a party$ free speech or

public safety when considerin5 a hate 5roup rally re=uest$ or lives saved or lives lost in

assessin5 medical pro5rams. #ven when they incorporate more than one dimension$ there

e;ists a limit such that individuals rarely brin5 in more than a few considerations Ee.5.$

Simon "-..F. 1he dimensions used are available, accessible$ and applicable or

appropriate EPrice and 1ewksbury "--+$ Llthaus and 3im '!!@ also see :i55ins "--$

Hhen and Hhaiken "---F. EQecall % construe frames in thou5ht as consistin5 of the

dimensions of evaluation.F

L consideration must be stored in memory to be available for retrieval and use in

constructin5 an attitude Ee.5.$ :i55ins "--F. 8or instance$ an individual needs to

understand how a hate 5roup rally mi5ht threaten public safety$ or how the 8irst

Lmendment pertains to unpopular political speech for these considerations to matter.

Similarly$ the individual must understand how the unemployment Eor employmentF rate

connects to a 5iven economic pro5ram. L consideration is available only when an

individual comprehends its meanin5 and si5nificance.

Accessibilit refers to the likelihood that an available consideration e;ceeds an

activation threshold to be used in an evaluation Ee.5.$ :i55ins$ Qholes$ and Jones "-++F.

Put another way$ the available consideration stored in lon5,term memory enters an

individual?s mind when formin5 an evaluation. %ncreases in accessibility occur throu5h

Bpassive$ unconscious processes that occur automatically and are uncontrolledC E:i55ins

and 3in5$ "-(") +*F.

"

"

Just how accessible a consideration needs to be for use$ however$ is uncertain@ 8a>io E"--.) '+0F states

"!

Lccessibility increases with chronic or fre=uent use of a consideration over time

or from temporary conte;tual cuesDincludin5 communications Ee.5.$ frames in

communicationFDthat re5ularly or recently brin5 the consideration to mind EAar5h$

Aond$ &ombardi$ and 1ota "-($ Aar5h$ &ombardi$ and :i55ins "-((F. Qepeated

e;posure to a frame$ such as fre=uently hearin5 someone emphasi>e free speech or lives

lost$ induces fre=uent processin5$ which in turn increases the accessibility of the frame.

'

1he impact of an accessible consideration also can depend on its applicabilit or

appropriateness to the obMect bein5 evaluated Ee.5.$ Strack$ Jartin$ and Schwar> "-((F.

8or instance$ concern that a rally will tie up traffic may be available and accessible$ but

the individual may view it as irrelevant and 5ive it no wei5ht. 1he likelihood that a

consideration raised by a frame will be Mud5ed applicable and shape an individual?s

opinion increases with conscious perceptions of its stren5th or relevance E#a5ly and

Hhaiken "--0$ Nelson$ Hlawson$ and /;ley "--+F.

%ndividuals do not$ however$ always en5a5e in applicability evaluations Eas it

re=uires conscious processin5F@ doin5 so depends on personal and conte;tual factors

E:i55ins "--$ Druckman '!!*F. %ndividuals motivated to form an accurate attitude will

likely deliberately assess the appropriateness of a consideration E8a>io "--.$ 8ord and

3ru5lanski "--.$ Stapel$ 3oomen$ and Reelenber5 "--(F.

0

1he information conte;t also

matters$ as the introduction of conflictin5 or competitive information Ee.5.$ multiple$

that the Bmodel is limited to makin5 predictions in relative terms.C

'

Ls intimated earlier$ an accessible consideration Ethat is emphasi>ed in a frameF will be i5nored if other

chronically accessible considerations are deemed more salient Ee.5.$ Shen and #dwards '!!.F. 8or e;ample$

Mud5es and lawyers who are trained in constitutional law are more likely than ordinary citi>ens to set aside

security concerns and be tolerant in controversies over civil liberties if there is a constitutional norm that

supports their attitude EHhon5 "--F. /r$ an individual who is presently unemployed may not be moved

from fre=uently hearin5 about the employment rates 5enerated by a new economic pro5ram. %n these cases$

stron5 prior beliefs and e;periences determine the frame in an individual?s mind.

0

%ndividuals also need to have the opportunity to deliberate$ meanin5 that they have at least a brief amount

of time Ee.5.$ secondsF to consider alternatives.

""

alternative framesF can stimulate even less personally motivated individuals to en5a5e in

conscious$ deliberate assessments of the appropriateness of competin5 considerations

E&ombardi$ :i55ins$ and Aar5h "-(+$ Strack$ Jartin$ and Schwar> "-(($ Jartin and

Lchee "--'$ Jou$ Shanteau$ and :arris "--F. /n the other hand$ individuals lackin5

personal motivation or the stimulus of competition likely rely uncritically on the

considerations made accessible throu5h e;posure to a messa5eDapplicability or

appropriateness is a non,factor in these cases. 1hey base their preferences on whichever

frames happen to be accessible.

When conscious processin5 occurs$ the perceived applicability or strength of a

frame depends on two factors. Stron5 frames emphasi>e available considerations@ a frame

focused on unavailable considerations cannot have an effect Ei.e.$ it is inherently weakF.

1he other factor is the Mud5ed persuasiveness or effectiveness of the frame. 1his latter

factor is akin to what Pan and 3osicki E'!!") *-F call Bframin5 potencyC Ealso see

JcHombs '!!*) -",-+ on Bcompellin5 ar5umentsCF.

#mpirically$ frame stren5th is established by askin5 individuals Ee.5.$ in a pre,

testF to rate the effectiveness or persuasiveness of various frames in communication$ on a

particular issue. 8or e;ample$ study participants may view a hate 5roup rally frame

emphasi>in5 free speech as effective and one hi5hli5htin5 traffic problems as less

compellin5. %f so$ then$ when individuals are motivated Eby individual interest or the

conte;tF to en5a5e in applicability evaluations$ only the free speech frame should have an

impact since they will assess and follow stron5 frames only. %f$ however$ motivation to

evaluate applicability is absent$ then either frame mi5ht matter since individuals rely on

any accessible frame. While this approach to operationali>in5 frame stren5th is

"'

empirically practicalDsince it allows a researcher to isolate stron5 as opposed to weak

framesDit leaves open the important =uestion of why a particular frame is seen as stron5.

1his is a topic to which % will later return.

Equivalency Frames Versus Emphasis Frames

1he portrayal of an individual?s frame as dependin5 on the availability$

accessibility$ and$ at times$ applicability of distinct dimensions applies to emphasis Ei.e.$

issue or value framesF and e=uivalency Ei.e.$ valenceF frames. %t also accentuates the

difference between them. #=uivalency frames have their differential effects when an

individual bases the evaluation on whatever dimensionDsuch as lives saved or

employmentDhappens to be accessible Esee Jou$ Shanteau$ and :arris "--) -$ &evin$

Schneider$ and 2aeth "--() "*,"$ Druckman '!!*F. Lccessibility can increase due to

the description of a problem Ewhich is akin to a frame in communicationF$ as when an

individual learns of medical pro5rams described in terms of lives lost. %f an individual

en5a5es in applicability evaluations due to motivation or conte;tual conditions$ the

differential impact of the lo5ically e=uivalent frames should dissipate. 1his occurs

because the individual will consciously reco5ni>e that deaths can be thou5ht of as lives

saved or employment e=uals unemployment$ and thus$ will not focus on 5ains or losses

Ee.5.$ he6she will reco5ni>e the e=uivalencyF. 1his renders the framin5 effect mute. 1he

individual will not be in losses frame of mind$ but rather$ will consider losses and 5ains.

*

Druckman E'!!*F offers evidence alon5 these lines. Specifically$ he replicates

traditional framin5 effectsDusin5 four distinct problems

.

Dfindin5$ for e;ample$ that

those e;posed to a ne5ative frame Ee.5.$ money lostF e;hibit distinct preferences from

*

%n such a situation$ there is a possibility of a ne5ativity bias where ne5ative information receives 5reater

wei5ht@ this bias$ while related$ is distinct from a framin5 effect.

.

Problems came from the domains of disease$ crime$ investment$ and employment.

"0

those receivin5 an e=uivalent positive frame Ee.5.$ money 5ainedF Ealso see :see "--F.

1he effects disappear$ however$ amon5 participants who receive multiple competin5

frames Ee.5.$ both the 5ain and loss framesF. 1he competitive information conte;t

presumably stimulates applicability evaluations leadin5 participants to reco5ni>e the

e=uivalency of the frames$ makin5 them ineffective. /ther work shows that$ even in non,

competitive environments$ motivated individualsDsuch as those with hi5h co5nitive

ability EStanovich and West "--(F or stron5ly held attitudes E&evin Schneider$ and 2aeth

"--() "!FDe;hibit substantially less susceptibility to e=uivalency framin5 effects Ealso

see 8a5ley and Jiller "-(+$ Jiller and 8a5ley "--"$ 1akemura "--*$ Sieck and 4ates

"--+F. 1his further supports the idea that when stimulated to assess applicability$

individuals reco5ni>e alternative ways of viewin5 the problemDthey appreciate that one

can construe the problem as lives lost or lives savedDand the e=uivalency framin5

effects vitiate. %n other words$ motivation leads one to reco5ni>e the e=uivalent ways of

viewin5 the problem.

1he effect of applicability evaluations differs when it comes to emphasis framin5$

where individuals consider substantively distinct dimensions Ee.5.$ free speech and public

safety$ or forei5n affairs and the economyF. Honscious reco5nition and evaluations of

these dimensions will not lead individuals to view them as identical Eas with e=uivalency

framesF@ instead$ individuals will evaluate the dimensions? stren5ths. Ls e;plained$

stren5th involves availability$ but perhaps more importantly$ persuasivenessDwhich

dimension is most compellin5< %n their study of opinions about limitin5 urban sprawl$

Hhon5 and Druckman E'!!+bF e;posed some participants to a communication usin5 both

a pro community frame Ee.5.$ limitin5 urban sprawl creates dense$ stron5er communitiesF

"*

and a con economic costs frame Ee.5.$ limitin5 sprawl will increase housin5 pricesF. Ls

with e=uivalency framin5 effects$ e;posure to multiple competin5 frames likely

stimulated applicability evaluations.

:owever$ unlike the e=uivalency framin5 case$ with

emphasis framin5 the evaluations do not mute the effects. 1his is the case because

thinkin5 about alternative frames does not lead one to conclude they are lo5ically

e=uivalent Esince they are notF@ instead$ individuals evaluate the substantive stren5th of

the alternative dimensions.

Hhon5 and Druckman had previously identified the economic frame as bein5

stron5 and the community frame as bein5 weak Ebased on the previously discussed pre,

test approach where individuals rate the effectiveness of various framesF. Ls e;pected$

then$ only the economic costs frame influenced opinions@ competition did not cancel out

competin5 frames but rather led to the stron5 frame winnin5. Unfortunately$ Hhon5 and

Druckman E'!!+bF$ like most others$ offer little insi5ht on what factors lie behind relative

stren5th.

1he effect of individual motivation similarly differs in its effect for the distinct

types of framin5 effects. Unlike with e=uivalency frames$ emphasis frames often have

lar5er effects on motivated individuals. 1hese individuals have the ability to connect

distinct considerations to their opinions Ei.e.$ they have a broader ran5e of available

considerationsF EHhon5 and Druckman '!!+a) ""!,"""F. %n the urban sprawl study$

Hhon5 and Druckman E'!!+bF find that a sin5le e;posure to the open space frame only

affected knowled5eable participants because open space was relatively more available.

Hhon5 and Druckman E'!!+b) *+F e;plain that Bless knowled5eable individuals re=uire

Direct psycholo5ical evidence on this is lackin5@ however$ the results are consistent with a theory that

posits such stimulation Eand is consistent with psycholo5ical work on e;ternal cues promptin5 conscious

processin5 beyond accessibility@ see Jartin and Lchee "--'F.

".

5reater e;posure to the open spaceI frame before their opinion shiftsI. 3nowled5eable

individuals may be =uicker to reco5ni>e the si5nificance of a frame.C

Conceptual Clarification

Jany communication scholars distin5uish framin5 effects from primin5$ a5enda

settin5$ and persuasion Ee.5.$ Scheufele '!!!F. 1he utility of these distinctions remains

unclear EHhon5 and Druckman '!!+cF. 1he term Bprimin5C entered the field of

communication when %yen5ar and 3inder E"-(+) 0F defined it as) BAy callin5 attention

to some matters while i5norin5 others$ television news influences the standards by which

5overnments$ presidents$ policies$ and candidates for public office are Mud5ed. Primin5

refers to chan5es in the standards that people use to make political evaluationsC Ealso see

%yen5ar$ 3inder$ Peters$ and 3rosnick "-(*F. 8or e;ample$ individuals e;posed to news

stories about defense policy tend to base their overall approval of the president Eor some

other political candidateF on their assessment of the president?s performance on defense.

1hus$ if these individuals believe the president does an e;cellent Eor poorF Mob on defense$

they will display hi5h Eor lowF levels of overall approval. %f$ in contrast$ these individuals

watch stories about ener5y policy$ their overall evaluations of the president?s

performance will tend to be based on his handlin5 of ener5y policy.

%mportantly$ this connotation of primin5$ in the political communication literature$

differs from how most psycholo5ists use the concept. 8or instance$ Sherman$ Jackie$ and

Driscoll E"--!) *!.F state that Bprimin5 may be thou5ht of as a procedure that increases

the accessibility of some cate5ory or construct in memory.C 1he typical BprocedureC for

increasin5 accessibility is not the same as e;posin5 individuals to continual media

emphasis of an issue. 4et$ %yen5ar and 3inder and many others assume$ to the contrary$

"

that media emphasis on an issue passively increases the accessibility of that issue. Jiller

and 3rosnick E'!!!F present evidence to the contrary in claimin5 that the effects of media

emphasis on an issue do not work throu5h accessibility and thus is not akin to primin5 as

defined by psycholo5ists Efor discussion$ see Druckman$ 3uklinski$ and Si5elman n.d.F.

%n my view$ the psycholo5ical model of framin5 presented above can be

5enerali>ed to political communication primin5 by assumin5 that each consideration

constitutes a separate issue dimension or ima5e EDruckman and :olmes '!!*F on which

the politician is assessed. When a mass communication places attention on an issue$ that

issue will receive 5reater wei5ht via chan5es in its accessibility and applicability. %f this

is correct$ then framin5 effects and what communication scholars have called primin5

effects share common processes and the two terms can be used interchan5eably Ealso see

Hhon5 and Druckman '!!+a) "".F. EL5ain$ this ar5ument does not apply to how

psycholo5ist employ the term primin5.F

L similar ar5ument applies to a5enda settin5$ which occurs when a speaker?s

Ee.5.$ a news outlet or politicianF emphasis on an issue or problem leads its audience to

view the issue or problem as relatively important Ee.5.$ JcHombs '!!*F. 8or e;ample$

when a news outlet?s campai5n covera5e focuses on the economy$ viewers come to

believe the economy is the most important campai5n issue. 1his concept

strai5htforwardly fits the above psycholo5ical model$ with the focus Ei.e.$ dependent

variableF lyin5 on assessments of the salience component of the attitude Erather than the

overall evaluation of the obMectF. 1he aforementioned e;ample can be construed as the

news outlet framin5 the campai5n in terms of the economy$ and the researcher simply

5au5in5 the specific salience wei5hts Ew

i

F as the dependent variable.

"+

L final conceptual distinction concerns framin5 and persuasion. Nelson and

/;ley E"---F differentiate framin5 from persuasion by referrin5 to the former as a chan5e

in the wei5ht component$ w

i

$ of an attitude in response to a communication$ and the latter

as a chan5e in the evaluation component$ v

i

Ealso see Johnston$ Alais$ Arady$ and Hrete

"--') '"'$ Jiller and 3rosnick "--) ("$ Wood '!!!F. 8or e;ample$ in assessin5 a new

housin5 proMect$ framin5 takes place if a communication causes economic considerations

to become more important relative to environmental considerations. Persuasion occurs if

the communication alters one?s evaluation of the proposal on one of those dimensions

Ee.5.$ by modifyin5 one?s beliefs about the proMect?s economic conse=uencesF. 1his

distinction stems from the focus in most persuasion research on the evaluation

components of an attitude. 1he key$ yet to be answered =uestions$ is whether the

processes Eand mediators and moderatorsF underlyin5 chan5es in the wei5ht and

evaluations components differ@ if they do not$ then perhaps the concepts should be

studied in concert. 1hese are not easy issues to address$ however$ since piecin5 apart the

specific process by which a communication influences overall attitudes is not

strai5htforward.

Jy ar5ument that these various concepts$ unless evidence can be put forth to

establish meditational and6or moderator distinctions$ can all be enveloped under a sin5le

rubric Eand psycholo5ical modelF should facilitate further theoretical development Ealso

see %yen5ar '!"!F. %t will enable scholars studyin5 primin5$ a5enda settin5$ and framin5

to avoid redundancy and focus more on pressin5 unanswered =uestions.

Frames in Politics

Politics involves individuals and 5roups$ with conflictin5 5oals$ reachin5

"(

collective a5reements about how to allocate scarce resources Ee.5.$ how to fund social

security or health care$ which candidate to support 5iven that only one can win$ and so

forthF. When it comes to makin5 such political choices$ three features stand out. 8irst$ the

bulk of decisions involve ill!structured problems that lack Bcorrect answers$C involve

competin5 values$ and can be resolved in distinct ways. Lt the e;treme$ there is no clarity

on what the decision even is Ee.5.$ is a terrorist attack a war<F. Purkitt E'!!") F e;plains

that most political problems are Bill,structuredI typically there is little or no a5reement

on how to define or frame the problemC Ealso see 2uess and 8arnham '!!!) 0.F.

Honse=uently$ emphasis framin5 applies to a broader ran5e of political decisions where

parties ar5ue over which of many substantively distinct values or considerations should

carry the day Ee.5.$ Aerelson$ &a>arsfeld$ JcPhee "-.*$ Schattschneider "-!F.

+

Sniderman and 1heriault E'!!*) "0.,"0F e;plain)

8ramin5 effects$ in the strict sense$ refer to semantically distinct conceptions of e;actly the same

course of action that induce preference reversals. L classic e;ample is an e;periment by

3ahneman and 1verskyI %t is difficult to satisfy the re=uirement of interchan5eability of

alternatives outside of a narrow ran5e of choices. Hertainly when it comes to the form in which

alternatives are presented to citi>ens makin5 political choices$ it rarely is possible to establish e;

ante that the 5ains Eor lossesF of alternative characteri>ations of a course of action are strictly

e=uivalent. %t accordin5ly should not be surprisin5 that the concept of framin5$ for the study of

political choices$ typically refers to characteri>ations of a course of action in terms of an

alternative Ncentral or5ani>in5 idea or story line that provides meanin5 to an unfoldin5 strip of

events? E2amson and Jodi5liani "-(+) "*0F.

1his is an important point insofar as it means that the bulk of studies on political

communication$ includin5 those discussed below$ employ a conception of framin5 effects

Ei.e.$ emphasis framin5F that differs from that common in the behavioral decision and

psycholo5y literatures Ei.e.$ e=uivalency framin5F.

Second$ the notable material and symbolic conse=uences of political decisions

+

#=uivalency framin5 may be relevant in some circumstances Esee$ e.5.$ JcDermott "--($ Aartels '!!0F.

#=uivalency framin5 likely matters more on structured problems when the descriptions are clearer and

consensual but can be construed in distinct but lo5ically e=uivalent ways.

"-

mean multiple actors attempt to influence decision,makin5. 1hese actors$ includin5

politicians$ interest 5roups$ and media outlets$ strive to shape preferences of ordinary

citi>ens whose opinions shape electoral outcomes and often 5uide day,to,day policy

decisions Ee.5.$ #rikson$ Jac3uen$ and Stimson '!!'F. 1his results in a strategic political

environment of competing information.

1hird$ in most circumstances$ and in spite of the importance of many decisions$

citi>ens possess scant information and have little motivation to en5a5e in e;tensive

deliberation. #vidence alon5 these lines comes conclusively from the last fifty years of

public opinion and votin5 research Ee.5.$ Delli,Harpini and 3etter "--F. %n the remainder

of this chapter$ % e;pand these latter two points by reviewin5 selected e;amples of

research on strate5ic EemphasisF framin5 and its effects.

(

Political Frames in Communication

1here e;ists a virtual cotta5e industry in communication studies that traces the

evolution of particular frames over time. While there is value in this descriptive

enterprise$ it provides little insi5ht into what Scheufele E"---F calls the framin5 buildin5

process of how speakers choose to construct frames in communication. :ere % provide

three e;amples from my own work that reveal how strate5ic concerns shape frame

choices by politicians. % then briefly discuss media framin5.

1he first e;ample comes from Druckman and :olmes? E'!!*F study of President

Aush?s first post,'!!" State of the Union address Edelivered on January '-$ '!!'F. 1he

State of the Union provides a Bonce,a,year chance for the modern president to inspire and

persuade the Lmerican peopleC ESaad '!!'F and to establish his a5enda EHohen "--+F.

(

Notice that the identified features of political decision,makin5 involve the nature of the choice$ the

conte;t$ and the individual. 1hese dimensions also constitute central elements to theories of decision,

makin5 more 5enerally EPayne$ Aettman$ and Johnson "--0) *F.

'!

Aush faced a fairly divided audience@ citi>ens were movin5 their focus away from

terrorism and homeland security towards more of an emphasis on the economy and the

impendin5 recession. Lccordin5 to the January '!!' 2allup poll$ 0.G of respondents

named terrorism or related problems as the most important problem facin5 the nation

compared to 00G who named some sort of economic problem Efollowed by education at

GF. Prior to Aush?s address$ analysts predicted that he would focus e=ually on

terrorism6homeland security and the economy. 8or e;ample$ HNN predicted that Aush

would Bfocus on war$ economy$C while JSNAH described Aush as preparin5 for a

Bbalancin5 actITdealin5U with terrorism$ recessionC EDruckman and :olmes '!!*) +!F.

While this made sense$ 5iven the aforementioned national focus on

terrorism6homeland security and the economy$ it made little strate5ic sense. Aush?s issue,

specific approval on security Erou5hly (GF was substantially hi5her than on the

slumpin5 economy Erou5hly 0"GF ESaad '!!'F. Ay framin5 the country?s situation in

terms of terrorism6homeland security$ Aush could potentially induce people to add wei5ht

to terrorism6homeland security in their evaluations of Aush and the nation?s overall

situation. Lnd$ this is e;actly what Aush did. %ndeed$ a content analysis of the speech

reportin5 the percenta5e of policy statements devoted to various cate5ories shows$ that

contrary to pre,debate e;pectations$ Aush framed the bulk of his policy discussion E*-GF

in terms of terrorism6homeland security. :e devoted only "!G to each of the economy

and the war in Lf5hanistan Ewith the remainin5 parts of the speech focusin5 on various

other domestic and forei5n issuesF. 1his is stark evidence of strate5ic framin5 and it had

an effect on subse=uent media covera5e. "he #ew $or% "imes headline the day after the

address stated) BAush$ 8ocusin5 on 1errorism$ Says Secure U.S. %s 1op PriorityC ESan5er

'"

'!!'F.

Ldditional evidence su55ests that Aush?s behavior reflects a 5eneral pattern.

Druckman$ Jacobs$ and /stermeier E'!!*F e;amine Ni;on?s rhetorical choices durin5 his

first term in office E"--,"-+'F. 1he authors measure frames in communication by

codin5 a lar5e sample of Ni;on?s public statements and countin5 the amount of space

devoted to distinct issues Ee.5.$ welfare$ crime$ civil ri5htsF. Ls with the Aush study$ this

codin5 captures how Ni;on framed his administration and the nation?s 5eneral direction.

&inkin5 the rhetorical data with pollin5 results from Ni;on?s private archives$ Druckman

Jacobs$ and /stermeier find that$ on domestic issues$ Ni;on carefully chose his frames in

strate5ically favorable ways. 8or e;ample$ if public support for Ni;on?s position on a

particular domestic issue Ee.5.$ Ni;on?s ta; plans$ which a lar5e percenta5e of the public

supportedF increased by "!G over the total avera5e$ then$ holdin5 other variables at their

means$ Ni;on increased attention to that domestic issue by an avera5e of .(G

EDruckman$ Jacobs$ and /stermeier '!!*) "'"+,"'"(F. Ni;on did not$ by contrast$

si5nificantly respond to chan5es in issues the public saw as BimportantC Ee.5.$ he would

use a ta; frame even if most of the public did not see ta;es as an important problemF. %n

short$ Ni;on framed his addresses so as to induce the public to base their presidential and

5eneral evaluations on the criteria that favored him Ei.e.$ issues on which the public

supported him$ such as ta;esF. :e i5nored the salience of those issues and$ in fact$

presumably hoped to re,frame public priorities so as to render favorable issues to be most

salient. Ls Ni;on?s chief of staff$ :.Q. :aldeman$ e;plained$ usin5 frames that hi5hli5ht

Bissues where the President is favorably receivedC would make BLmericans reali>e that

the President is with them on these issuesC EDruckman$ Jacobs$ and /stermeier '!!*)

''

"'"(F.

Hon5ressional candidates also strate5ically choose their frames. /ne of the most

salient features of con5ressional campai5ns is the incumbency advanta5e that provides

incumbents with up to a "! percenta5e point advanta5e ELnsolabehere and Snyder '!!*)

*(+F. 1he incumbency advanta5e stems$ in part$ from three particular candidate

characteristics) voters find incumbents appealin5 because they possess e;perience in

office$ they are familiar Ee.5.$ have ties to the districtF$ and they have provided benefits

for the district or state Ee.5.$ or5ani>in5 events concernin5 a local issue$ casework$ pork

barrel proMectsF Ee.5.$ Jacobson '!!*F. What this means$ from a framin5 perspective$ is

that incumbents have a strate5ic incentive to hi5hli5ht e;perience$ familiarity$ and

benefits. %n contrast$ challen5ers will frame the campai5n in other terms$ emphasi>in5

alternative considerations that tend to matter in con5ressional elections$ includin5 issue

positions$ partisanship$ endorsements$ and polls Ee.5.$ to show the candidate is viableF.

Druckman$ 3ifer$ and Parkin E'!!-F test these predictions with data from a

representative sample of U.S. :ouse and Senate campai5ns from '!!'$ '!!*$ and '!!.

1hey do so via content analyses of candidate websites of which they coded the terms

candidates used to frame the campai5n Ei.e.$ the e;tent to which they emphasi>e different

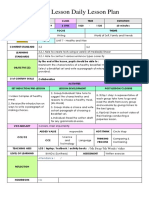

criteriaF. 8i5ure " presents the results from the content analyses$ reportin5 predicted

probabilities of candidates employin5 the distinct types of frames on their websites. E8or

some variables$ the probability is the likelihood of employin5 the frame anywhere on

their site. 8or other variables$ the probability is the likelihood of usin5 the frame more

often than the overall avera5e@ details and more refined analyses are available in

Druckman$ 3ifer$ and Parkin '!!-F. 1he fi5ure provides clear evidence of strate5ic

'0

framin5) incumbents frame their campai5ns in ways that benefit them$ emphasi>in5

e;perience in office$ familiarity$ and district ties$ while challen5ers frame the campai5n

in alternative terms. 1he normative implications are intri5uin5$ since campai5n frames

that often establish subse=uent policy a5endas Ee.5.$ Jamieson '!!!) "+F are driven$ in no

small way$ by strate5ic considerations that may bear little relationship with pressin5

5overnmental issues.

[Figure 1 About Here]

#ach of the three e;amples focuses on Must one side of a more comple; framin5

environment. 1here is little doubt that$ followin5 Aush?s '!!' State of the Union address$

Democrats responded by increasin5ly framin5 the country in terms of the economy$ and

that Ni;on?s opponents emphasi>ed alternative issues that were less favorable for Ni;on.

%n the case of the Hon5ressional data$ attentive voters would be e;posed to competin5

frames from incumbents as opposed to challen5ers. 1o see the e;tent to which

competition between frames is the norm$ Hhon5 and Druckman E'!"!F content analy>ed

maMor newspaper covera5e of fourteen distinct issues over time$ countin5 the number of

frames put forth on each issue Eas well as other features of the framesF.

-

While the data do

not provide insi5ht into strate5ic incentives$ the findin5s reveal a comple; mi; of frames

for each issue.

Hhon5 and Druckman computed a score to capture the wei5hted number of

frames on a 5iven issue$ with frames employed more often receivin5 5reater wei5ht.

Lcross the fourteen issues$ the avera5e number of wei5hted frames is ..!- Estandard

-

%ssues included the Patriot Lct$ 5lobal warmin5$ intelli5ent desi5n$ same,se; marria5e in U.S. and in

Hanada$ social security at two points in time$ the &ush v' (ore Supreme Hourt case$ the Lbu 2hraib

controversy$ an immi5ration initiative$ a Na>i rally$ two 3u 3lu; 3lan rallies$ and a proposal for a state

sponsored casino.

'*

deviation P "."-F. 1he issue with the fewest wei5hted frames was covera5e of a "--( 3u

3lu; 3lan rally in 1ennessee Ewith 0.!0 wei5hted frames includin5 free speech$ public

safety$ and opposin5 racismF. 1he issue with the most wei5hted frames was covera5e of

the '!!* Lbu 2hraib controversy concernin5 prisoner abuse by members of the United

States Lrmed 8orces Ewith .- wei5hted frames$ includin5 military responsibility$

presidential administration responsibility$ individual responsibility$ military commander

responsibility$ ne5ative conse=uences for international relations$ positive conse=uences

for international relations$ ne5ative domestic conse=uences$ positive domestic

conse=uences$ and othersF. Details on the other issues are available in Hhon5 and

Druckman E'!"!F.

%mportantly$ on each issue$ many of the frames employed competed with one

another$ meanin5 they came from opposin5 sides. 8or e;ample$ a free speech frame of a

hate 5roup rally likely increases support$ while a public safety frame decreases it.

Similarly$ the Lbu 2hraib individual responsibility frame su55ests that fault lies with the

individuals involved$ whereas the administration or military commander frames put the

bulk of the blame on the culture established by hi5her level actors. /pposin5 sides

simultaneously employ contrary frames which make their way into media covera5e. :ow

individuals process these mi;es of frames is the topic to which % now turn.

Political Frames in Thought

1he typical EemphasisF framin5 effect e;periment randomly assi5ns individuals to

receive one of two alternative representations of an issue. 8or e;ample$ in studies of

people?s willin5ness to allow hate 5roups to conduct a rally$ individuals learn of the issue

framed either in terms of free speech or in terms of public safety. %n this case$ the

'.

relevant comparison is the difference of opinion between individuals in the two

conditions. 1he modal findin5 is a si5nificant effect$ such that individuals e;posed to the

free speech frame are si5nificantly more likely to view free speech considerations as

important and conse=uently allow the rally Ecompared to individuals who receive the

public safety frame@ see Nelson$ Hlawson$ and /;ley "--+F.

"!

1his is an e;ample of

framin5 since presumably the overall effect on rally support occurred via an increase in

the salience of the free speech consideration.

Jy above ar5ument su55ests that these one,sided desi5ns miss a definin5 feature

of most political situationsDcompetition between frames. Lcknowled5in5 this$ some

recent work e;plores competitive settin5s. %n their pioneerin5 study$ Sniderman and

1heirault E'!!*F demonstrate$ with two e;perimental surveys$ that when competin5

frames are presented alon5side one another Ee.5.$ a free speech and a public safetyF$ they

mutually cancel out$ such that the frames do not affect individuals? opinions Ee.5.$ those

e;posed to both frames do not differ from a control 5roup e;posed to no framesF. Hhon5

and Druckman E'!!+a$b$cF build on Sniderman and 1heirault E'!!*F@ as mentioned

above$ they show that in competitive settin5s$ a key factor concerns a frame?s stren5th$

with stron5 frames winnin5 out even a5ainst weaker frames that are repeated. %ndeed$ in

the urban sprawl e;periment described above$ when respondents received the community

frame multiple times Ee.5.$ twiceF$ it was the economic frame$ even when presented only

once$ that drove opinions.

Lnother e;ample of the importance of stren5th comes from Druckman?s E'!"!F

study of support for a publicly funded casino. Aased on pre,test data that employed the

"!

1here is substantial research on the moderators of framin5 effects in one,sided situations. 8or a review$

see Hhon5 and Druckman E'!!+c) """,""'F Ealso see &echeler$ de Vreese$ and Slothuus '!!-F. Qelated to

this is the lar5e literature on persuasion moderators in one,sided situations Esee #a5ly and Hhaiken "--0F.

'

previously discussed approach to assessin5 stren5th$ Druckman identified two stron5

EBstrCF frames) a pro economic benefits frame EBeconC@ e.5.$ revenue from the casino will

support educational pro5ramsF$ and a con social costs frame EBsoc costsC@ e.5.$ casinos

lead to addictive behaviorF. :e also found three weak EBwkCF frames) a pro entertainment

frame EBentertCF$ a con corruption frame EBcorrCF$ and a con morality frame EBmoralCF. :e

then e;posed a distinct set of participants to various mi;es of these frames@ a summary of

the results appears in 8i5ure '$ which 5raphs the shift in avera5e opinion$ by frame

e;posures$ relative to a control 5roup that received no frames. %n every case$ the stron5

frame moved opinion and the weak frame did not. 8or e;ample$ the final condition in

8i5ure ' shows that a sin5le e;posure to the stron5 economic benefits frame substantially

moved opinion Eby *"GF even in the face of two con weak frames. 1his accentuates the

findin5 that stren5th is more important than repetition. ESimultaneous e;posure to the two

stron5 competin5 frames did not si5nificantly move opinion.F

[Figure 2 About Here]

1hese results be5 the aforementioned =uestion of what lies beyond a frame?s

stren5th. Why are some frames perceived as stron5 and others weak< #ven the lar5e

persuasion literature offers scant insi5ht) BUnhappily$ this research evidence is not as

illuminatin5 as one mi5ht supposeI %t is not yet known what it is about the Nstron5

ar5uments?I that makes them persuasiveC E/?3eefe '!!') "*+$ ".F. Qecall that %

previously mentioned that a common$ if not definin5$ element of opinion formation in

political settin5s is that individuals lack information and motivation. Ln implication is

that$ when it comes to assessin5 a frame?s stren5th Eor applicabilityF$ individuals will

often Eunless e;tremely motivatedF i5nore criteria seen as normatively desirable Ee.5.$

'+

lo5ic$ factsF and instead focus on factors that many theorists view as less than optimal.

1he little e;istin5 research on frame stren5th supports this perspective. 8or

e;ample$ Lrceneau; E'!!-) "F finds that Bindividuals are more likely to be persuaded by

political ar5uments that evoke co5nitive biases.C Specifically$ he reports that frames that

hi5hli5ht avertin5 losses or out,5roup threats resonate to a 5reater e;tent than do other$

ostensibly analo5ous ar5uments.

""

Druckman and Aolsen E'!!-F report that addin5

factual information to frames does nothin5 to enhance their stren5th. 1hey focus on

opinions about new technolo5ies$ such as carbon nanotubes EHN1sF. Druckman and

Aolsen e;pose e;perimental participants to different mi;es of frames in support and

opposed to the technolo5y. 8or e;ample$ a supportive frame for HN1s states BJost a5ree

that the most important implication of HN1s concerns how they will affect ener5y cost

and availability.C Ln e;ample of an opposed frame is BJost a5ree that the most

important implication of HN1s concerns their unknown lon5,run implications for human

health.C Druckman and Aolsen report that each of these two frames shifts opinions in the

e;pected directions. Jore importantly$ when factual information is added to one or both

frames Ein other conditionsFDsuch as citin5 a specific study about ener5y costs Ee.5.$ a

study shows HN1S will double the efficiency of solar cells in the comin5 yearsF$ that

information does nothin5 to add to the power of the frame. %n short$ frames with specific

factual evidence are no stron5er Ein their effectsF than analo5ous frames that include no

such evidence. 1his may be troublin5 insofar as one mi5ht view facts as an important

type of information to consider.

/ther work on frame stren5th su55ests it increases in frames that hi5hli5ht

""

:e also finds these effects are moderated by participants? level of fearDmore fearful individuals find the

ar5uments stron5er.

'(

specific emotions ELarWe '!!(@ Petersen '!!+F$ include multiple$ fre=uently appearin5$

ar5uments EAaum5artner$ De Aoef$ and Aoydstun '!!(F$ and6or have been used in the

past E#dy '!!F. 1he initial studies on frame stren5th make clear that one should not

confound Bstren5thC with Bnormative desirability.C What e;actly is normatively desirable

lies outside the purview of this chapter$ but is a topic that demands careful consideration

as scholars continue empirical forays into frame stren5th.

"'

onclusion

% have attempted to provide clarity to e;istin5 applications of the framin5 concept.

% draw a distinction between e=uivalency and emphasis framin5$ but su55est that the two

types fit into a sin5le psycholo5ical model. When it comes to political situations$

emphasis framin5 likely plays a more important role. 8uture research is needed to better

understand how competition works and how individuals evaluate a frame?s stren5th. 1hat

is$ why do some frames seem effective or compellin5 to people and others not.

%n terms of competition$ there are two relevant a5endas. 1he first concerns the

production of frames and how strate5ic actors not only respond to one another$ but also

how political actors interact with the media and ensure that their chosen frame receives

covera5e Esee #ntman '!!*F. 1his will entail a more e;plicit consideration of the

motivations of different media outlets. 1his parallels recent work on e=uivalency frames

that e;plores speakers? choices Ee.5.$ van Auiten and 3eren '!!-F and how those choices

affect evaluations of the speaker Ee.5.$ 3eren '!!+F. Second$ work on how competition

influences information processin5 and preference formation continues to be in its infancy.

While the model offered above provides some insi5ht$ much more work is needed. 1his

"'

/ne intri5uin5 direction for future work on frame stren5th is to build on :aidt?s E'!!+F foundational

moral impulses.

'-

echoes Aar5h?s E'!!) ".-F recent call that studies addressin5 accessibility and the

associated processes need to e;plore the impact of competition. 8uture work will also

benefit from incorporatin5 more e;plicit political considerations$ such as parties

competin5 to define issues and campai5ns ESlothuus and de Vreese '!!-F. %n terms of

stren5th$ it should be clear that more work is needed. Understandin5 what stren5thens a

frame is perhaps the most pressin5 =uestion in framin5 research. %ndeed$ frame stren5th

5oes a lon5 way towards determinin5 who wins and loses in politics.

0!

!e"erences

LarWe$ &ene. '!!(. B%nvesti5atin5 8rame Stren5th) 1he Hase of #pisodic and 1hematic

8rames.C Unpublished paper$ Larhus University.

LM>en$ %cek$ and Jartin 8ishbein. "-(!. )nderstanding Attitudes and Predicting *ocial

&ehavior. #n5lewood Hliffs$ NJ) Prentice,:all.

LM>en$ %cek$ and James Se;ton. "---. BDepth of Processin5$ Aelief Hon5ruence$ and

Lttitude,Aehavior Horrespondence.C %n Shelly Hhaiken$ and 4aacov 1rope Eeds.F$

+ual!Process "heories in *ocial Pscholog. New 4ork) 1he 2uilford Press.

Llthaus$ Scott &.$ and 4oun5 Jie 3im. '!!. BPrimin5 #ffects in Homple;

#nvironments.C ,ournal of Politics (ENovemberF) -!,-+.

Lnsolabehere$ Stephen$ and James J. Snyder. '!!*. BUsin5 1erm &imits to #stimate

%ncumbency Ldvanta5es When /fficeholders Qetire Strate5ically.C -egislative

*tudies .uarterl '-) *(+,."..

Lrceneau;$ 3evin. '!!-. BHo5nitive Aiases and the Stren5th of Political Lr5uments.C

Unpublished paper$ 1emple University.

Aar5h$ John L. '!!. BWhat :ave We Aeen Primin5 Lll 1hese 4ears<C /n the

Development$ Jechanisms$ and #colo5y of Nonconscious Social Aehavior.C

/uropean ,ournal of *ocial Pscholog 0) "*+,"(.

Aar5h$ John L.$ Qonald N. Aond$ Wendy J. &ombardi$ and Jary #. 1ota. "-(. B1he

Ldditive Nature of Hhronic and 1emporary Sources of Honstruct Lccessibility.C

,ournal of Personalit and *ocial Pscholog .!) (-,(+(.

Aar5h$ John L.$ Wendy J. &ombardi$ and #. 1ory :i55ins. "-((. BLutomaticity of

Hhronically Lccessible Honstructs in Person X Situation #ffects on Perception.C

,ournal of Personalit and *ocial Pscholog ..E/ctoberF).--,!..

Aartels$ &arry J. '!!0. BDemocracy With Lttitudes.C %n Jichael Aruce Jac3uen$ and

2eor5e Qabinowit> Eeds.F$ /lectoral +emocrac. Lnn Lrbor) 1he University of

Jichi5an Press.

Aaum5artner$ 8rank Q.$ Su>anna &. De Aoef$ and Lmber #. Aoydstun. '!!(. "he +ecline

of the +eath Penalt and the +iscover of 0nnocence. New 4ork) Hambrid5e

University Press.

Aerelson$ Aernard$ Paul 8eli; &a>arsfeld$ William N. JcPhee. "-.*. 1oting2 A *tud of

3pinion Formation in a Presidential 4ampaign. Hhica5o) Univ. Hhica5o Press.

0"

Aerinsky Ldam J.$ and 3inder Donald Q. '!!. BJakin5 Sense of %ssues 1hrou5h Jedia

8rames) Understandin5 the 3osovo Hrisis.C "he ,ournal of Politics () *!,.

Arewer$ Paul Q.$ and &ee Si5elman. '!!'. BPolitical Scientists as Holor Hommentators)

8ramin5 and #;pert Hommentary in Jedia Hampai5n Hovera5e.C Press5Politics

+) '0,0.

Hhen$ Serena$ and Shelly Hhaiken. "---. B1he :euristic,Systematic Jodel in %ts Aroader

Honte;t.C %n Shelly Hhaiken$ and 4aacov 1rope Eeds.F$ +ual!Process "heories in

*ocial Pscholog. New 4ork) 1he 2uilford Press.

Hhon5$ Dennis. "--. BHreatin5 Hommon 8rames of Qeference on Political %ssues.C %n

Diana H. Jut>$ Paul J. Sniderman$ and Qichard L. Arody Eeds.F$ Political

Persuasion and Attitude 4hange. Lnn Lrbor) 1he University of Jichi5an Press.

Hhon5$ Dennis$ and James N. Druckman. '!!+a. BL 1heory of 8ramin5 and /pinion

8ormation in Hompetitive #lite #nvironments.C ,ournal of 4ommunication .+)

--,""(.

Hhon5$ Dennis$ and James N. Druckman. '!!+b. B8ramin5 Public /pinion in

Hompetitive Democracies.C American Political *cience 6eview "!" E*F) 0+,...

Hhon5$ Dennis$ and James N. Druckman. '!!+c. B8ramin5 1heory.C Annual 6eview of

Political *cience "! E"F) "!0,"'.

Hohen$ Jeffrey #. "--+. Presidential 6esponsiveness and Public Polic 7a%ing. Lnn

Lrbor) University of Jichi5an Press.

Delli Harpini$ Jichael X.$ and Scott 3eeter. "--. 8hat Americans 9now About Politics

and 8h it 7atters. New :aven) 4ale University Press.

Dimitrova$ Daniela V.$ &ynda &ee 3aid$ Lndrew Paul Williams$ 3aye D. 1rammell.

'!!.. BWar on the Web) 1he %mmediate News 8ramin5 of 2ulf War %%.C

Press5Politics "!) '',**

Druckman$ James N. '!!"a. B/n 1he &imits /f 8ramin5 #ffects.C "he ,ournal of

Politics 0ENovemberF) "!*","!.

Druckman$ James N. '!!"b. B1he %mplications of 8ramin5 #ffects for Hiti>en

Hompetence.C Political &ehavior '0ESeptemberF) ''.,'..

Druckman$ James N. '!!*. BPolitical Preference 8ormation.C American Political *cience

6eview -(ENovemberF) +",(.

Druckman$ James N. '!"!. BHompetin5 8rames in a Political Hampai5n.C %n Arian 8.

Schaffner$ and Patrick J. Sellers$ eds.$ 8inning with 8ords2 "he 3rigins and

0'

0mpact of Framing. New 4ork) Qoutled5e.

Druckman$ James N.$ and 1oby Aolsen. '!!-. B8ramin5$ Jotivated Qeasonin5$ and

/pinions about #mer5ent 1echnolo5ies.C Unpublished paper$ Northwestern

University.

Druckman James N.$ and Justin W. :olmes. '!!*. BDoes Presidential Qhetoric Jatter<)

Primin5 and Presidential Lpproval.C Presidential *tudies .uarterl 0*) +..,++(

Druckman$ James N.$ &awrence Q. Jacobs$ and #ric /stermeier. '!!*. BHandidate

Strate5ies to Prime %ssues and %ma5e.C "he ,ournal of Politics ) "'!.,"''+.

Druckman$ James N.$ Jarktin J. 3ifer$ and Jichael Parkin. '!!-. BHampai5n

Hommunications in U.S. Hon5ressional #lections.C American Political *cience

6eview "!0) 0*0,0

Druckman$ James N.$ James :. 3uklinski$ and &ee Si5elman. N.d. B1he Unmet Potential

of %nterdisciplinary Qesearch) Political Psycholo5ical Lpproaches to Votin5 and

Public /pinion.C Political &ehavior$ 8orthcomin5.

Druckman$ James N.$ and Lrthur &upia. '!!!. BPreference 8ormation.C Annual 6eview

of Political *cience 0) ",'*.

#a5ly Llice :.$ and Shelly Hhaiken. "--0. "he Pscholog of Attitudes. 8ort Worth)

:arcourt Arace.

#dy$ Jill L. '!!. "roubled Pasts2 #ews and "he 4ollective 7emor of *ocial )nrest.

Philadelphia) 1emple University Press.

#nelow$ James J.$ and Jelvin J. :inich. "-(*. "he *patial "heor of 1oting. Aoston)

Hambrid5e University Press

#ntman$ Qobert J.. '!!*. Pro:ects of Power2 Framing #ews, Public 3pinion, and )'*'

Foreign Polic. Hhica5o) University of Hhica5o Press

#ntman$ Qobert J. "--0. B8ramin5.C ,ournal of 4ommunication *0E8allF) .",.(.

#rikson$ Qobert S. Jichael A. Jac3uen$ and James L. Stimson. '!!'. "he 7acro Polit.

New 4ork) Hambrid5e University Press.

8a5ley$ N.S.$ and Paul J. Jiller. "--+. B8ramin5 #ffects and Lrenas of Hhoice.C

3rgani;ational &ehavior and <uman +ecision Processes +"ESeptemberF) 0..,

0+0.

8a5ley$ N.S.$ and Paul J. Jiller. "-(+. B1he #ffects of Decision 8ramin5 on Hhoice of

Qisky vs. Hertain /ptions.C 3rgani;ational &ehavior and <uman +ecision

00

Processes 0-) '*,'++.

8a>io$ Qussell :. "--.. BLttitudes as /bMect,#valuation Lssociations.C %n Qichard #.

Petty$ and Jon L. 3rosnick Eeds.F$ Attitude *trength2 Antecedents and

4onse=uences. :illsdale) #rlbaum.

8ord$ 1homas #.$ and Lrie W. 3ru5lanski. "--.. B#ffects of #pistemic Jotivations on

the Use of Lccessible Honstructs in Social Jud5ment.C Personalit and *ocial

Pscholog &ulletin '") -.!,-'.

8urnham$ Ldrian. "-('. B1he Protestant Work #thic and Lttitudes 1owards

Unemployment.C ,ournal of 3ccupational Pscholog ..) '++,'(..

2amson$ William L.$ and Lndre Jodi5liani. "-(+. B1he Hhan5in5 Hulture of

Lffirmative Lction.C %n Qichard D. Araun5art Eed.F$ 6esearch in Political

*ociolog. Vol. 0. 2reenwich$ H1) JL%.

2offman$ #rvin5. "-+*. Frame Analsis2 An /ssa on the 3rgani;ation of /xperience.

Hambrid5e$ JL) :arvard University Press.

2rabe$ Jaria #.$ and #rik P. Aucy. '!!-. 0mage &ite Politics2 #ews and the 1isual

Framing of /lections. /;ford) /;ford University Press.

2uess$ 2eor5e J.$ and Paul 2. 8arnham. '!!!. 4ases in Public Polic Analsis '

nd

#dition. Washin5ton D.H.) 2eor5etown University Press.

:aidt$ Jonathan. '!!+. B1he New Synthesis in Joral Psycholo5y.C *cience 0") --(,

"!!'.

:i55ins$ #. 1ory. "--. B3nowled5e Lctivation) Lccessibility$ Lpplicability$ and

Salience. %n #. 1ory :i55ins$ and Lrie W. 3ru5lanski Eeds.F$ *ocial Pscholog.

New 4ork) 2uilford Press.

:i55ins$ #. 1ory$ and William S. Qholes$ and Harl Q. Jones. "-++. BHate5ory

Lccessibility and %mpression 8ormation.C ,ournal of /xperimental Pscholog

"0) "*",".*.

:i55ins$ #. 1ory$ and 2illian 3in5. "-(". BSocial Honstructs.C %n Nancy Hantor$ and

John 8. 3ihlstrom Eeds.F$ Personalit, 4ognition, and *ocial 0nteraction.

:illsdale) #rlbaum.

:see$ Hhristopher 3. "--. B1he #valuability :ypothesis) Ln #;planation for Preference

Qeversals between Joint and Separate #valuations of Llternatives.C

3rgani;ational &ehavior and <uman +ecision Processes +$ '*+,'.+.

%yen5ar$ Shanto. "--". 0s Anone 6esponsible> Hhica5o) 1he University of Hhica5o

Press.

0*

%yen5ar$ Shanto. '!"!. B8ramin5 Qesearch) 1he Ne;t Steps.C %n Arian 8. Schaffner and

Patrick J. Sellers Eeds.F$ 8inning with 8ords2 "he 3rigins and 0mpact of

Framing' New 4ork) Qoutled5e.

%yen5ar$ Shanto$ and Donald Q. 3inder. "-(+. #ews "hat 7atters2 "elevision and

American 3pinion. Hhica5o$ %&) University of Hhica5o Press.

%yen5ar Shanto$ Donald Q. 3inder$ Jark D. Peters$ Jon L. 3rosnick. "-(*. B1he #venin5

News and Presidential #valuations. ,ournal of Personalit ? *ocial Pscholog'

*) ++(,+(+

Jamieson$ 3athleen :. '!!!. /verthing $ou "hin% $ou 9now About Politics@ And 8h

$ouAre 8rong. New 4ork) Aasic Aooks.

Jacobson$ 2ary. '!!*. "he Politics of 4ongressional /lections, *ixth /dition. New 4ork)

Pearson &on5man.

Johnson,&aird$ Philip N. "-(0. 7ental 7odels2 "oward a 4ognitive *cience of

-anguage, 0nference and 4onsciousness. :arvard University Press

Johnston$ Qichard$ Lndre Alais$ :enry #. Arady$ and Jean Hrete. "--'. -etting the

People +ecide2 +namics of a 4anadian /lection. Stanford$ HL) Stanford

University Press.

Jou$ Jerwen$ James Shanteau$ and Qichard Jackson :arris. "--. BLn %nformation

Processin5 View of 8ramin5 #ffects.C 7emor ? 4ognition '*EJanuaryF) ","..

3eren$ 2ideon. '!!+. B8ramin5$ %ntentions$ and 1rust,Hhoice %ncompatibility.C

3rgani;ational &ehavior and <uman +ecision Processes "!0) '0(,'...

3inder$ Donald Q.$ and &ynn J. Sanders. "--. +ivided & 4olor2 6acial Politics and

+emocratic 0deals. Hhica5o) University of Hhica5o Press.

3Khber5er$ Lnton. "--(. B1he %nfluence of 8ramin5 on Qisky Decisions.C

3rgani;ational &ehavior and <uman +ecision Processes +.EJulyF) '0,...

&awrence$ Qe5ina 2. '!!*. B8ramin5 /besity) 1he #volution of News Discourse on a

Public :ealth %ssue.C Press5Politics -) .,+.

&echeler$ Sophie 3.$ Hlaes :. de Vreese$ and Qune Slothuus. '!!-. B%ssue %mportance as

a Joderator of 8ramin5 #ffects.C 4ommunication 6esearch 0E0F) *!!,*'..

&evin$ %rwin P.$ Sandra &. Schneider$ and 2ary J. 2aeth. "--(. BLll 8rames Lre Not

Hreated #=ual.C 3rgani;ational &ehavior and <uman +ecision Processes

+ENovemberF) "*-,"((.

0.

&ombardi$ Wendy J.$ #. 1ory :i55ins$ and John L. Aar5h. "-(+. B1he Qole of

Honsciousness in Primin5 #ffects on Hate5ori>ation.C Personalit and *ocial

Pscholog &ulletin "0ESeptemberF) *"",*'-.

Jartin$ &eonard &.$ and John W. Lchee. "--'. BAeyond Lccessibility.C %n &eonard &.

Jartin$ and Lbraham 1esser Eeds.F$ "he 4onstruction of *ocial ,udgments.

:illsdale) #rlbaum.

JcHombs$ Ja;well. '!!*. *etting the Agenda2 "he 7ass 7edia and Public 3pinion.

Jalden$ JL) Alackwell.

JcDermott$ Qose "--(. 6is% "a%ing in 0nternational 6elations2 Prospect "heor in

American Foreign Polic' Lnn Lrbor) University of Jichi5an Press.

Jiller$ Joanne J.$ and Jon L. 3rosnick. "--. BNews Jedia %mpact on 1he %n5redients

of Presidential #valuations) L Pro5ram of Qesearch on the Primin5 :ypothesis.C

%n Diana H. Jut>$ Paul J. Sniderman$ and Qichard L. Arody Eeds.F$ Political

Persuasion and Attitude 4hange. Lnn Lrbor) University of Jichi5an Press

Jiller$ Joanne J.$ and Jon L. 3rosnick. '!!!. BNews Jedia %mpact on the %n5redients of

Presidential #valuations) Politically 3nowled5eable Hiti>ens are 2uided by a

1rusted Source.C American ,ournal of Political *cience **) '-.,0!-.

Jiller$ Paul J.$ and N.S. 8a5ley. "--". B1he #ffects of 8ramin5$ Problem Variations$

and Providin5 Qationale on Hhoice.C Personalit and *ocial Pscholog &ulletin

"+) ."+,.''.

Nelson$ 1homas #.$ Qosalee L. Hlawson$ and Roe J. /;ley. "--+. BJedia 8ramin5 of a

Hivil &iberties Honflict and %ts #ffect on 1olerance.C American Political *cience

6eview -"E0F) .+,.(0.

Nelson$ 1homas #.$ Roe J. /;ley$ and Qosalee L. Hlawson. "--+. B1oward a

Psycholo5y of 8ramin5 #ffects.C Political &ehavior "- E0F) ''",'*.

Nelson$ 1homas #.$ and Roe J. /;ley. "---. B%ssue framin5 effects and belief

importance and opinion.C ,ournal of Politics ") "!*!,"!+.

Nisbet$ Jatthew H.$ Domini=ue Arossard$ and Ldrianne 3roepsch. '!!0. B8ramin5

Science) 1he Stem Hell Hontroversy in an L5e of Press6Politics.C Press5Politics'

() 0,+!

/?3eefe$ Daniel J.$ and Jakob D. Jensen. '!!. B1he Ldvanta5es of Hompliance or the

Disadvanta5es of Noncompliance< L Jeta,Lnalytic Qeview of the Qelative

Persuasive #ffectiveness of 2ain,8ramed and &oss,8ramed Jessa5es.C

4ommunication $earboo% 0!) "Y*0.

0

/?3eefe$ Daniel J. '!!'. Persuasion. '

nd

#dition. 1housand /aks) Sa5e.

Pan$ Rhon5dan5$ and 2erald J. 3osicki. '!!". B8ramin5 as a Strate5ic Lction in

Publication Deliberation.C %n Stephen D. Qeese$ /scar :. 2andy$ Jr.$ and Lu5ust

#. 2rant Eeds.F$ Framing Public -ife. :illsdale) #rlbaum.

Payne$ John W.$ James Q. Aettman$ and #ric J. Johnson. "--0. "he Adaptive +ecision

7a%er. New 4ork) Hambrid5e University Press.

Petersen$ Jichael Aan5. '!!+. BHauses of Political Lffect) %nvesti5atin5 the %nteraction

Aetween Political Ho5nitions and #volved #motions.C Unpublished paper$ Larhus

University.

PiSon$ Ldelson$ and :ilda 2ambara. '!!.. BL Jeta,Lnalytic Qeview of 8ramin5 #ffect)

Qisky$ Lttribute$ and 2oal 8ramin5.C Psicothema "+) 0'.,00".

Price$ Vincent$ and David 1ewksbury. "--+. BNews Values and Public /pinion.C %n

2eor5e L. Aarnett$ and 8ranklin J. Aoster Eeds.F$ Progress in 4ommunication

*ciences$ Vol. "0. 2reenwich$ H1) Lble; Publishin5 Horporation.

Purkitt$ :elen #. '!!". BProblem Qepresentation and Variation in the 8orecasts of

NPolitical #;perts.?C Paper presented at the

th

%nternational Hommand and

Hontrol Qsearch and 1echnolo5y Symposium$ Lnnapolis$ JD.

Qichardson$ John D.$ and 3aren J. &ancendorfer. '!!*. B8ramin5 Lffirmative Lction)

1he %nfluence of Qace on Newspaper #ditorial Qesponses to the University of

Jichi5an Hases.C Press5Politics. -) +*,-*

Qiker$ William :. "--!. B:eresthetic and Qhetoric in the Spatial Jodel.C %n James J.

#nelow$ and Jelvin J. :inich Eeds.F$ Advances in the *patial "heor of 1oting.

Hambrid5e$ JL) Hambrid5e Univ. Press

Saad$ &ydia. '!!'. BAush Soars into State of the Union with #;ceptional Public

Aackin5.C "he (allup 3rgani;ation$ Poll Lnalyses. '- January '!!'.

San5er$ David #. '!!'. BAush 8ocusin5 on 1errorism$ Say Secure U.S. %s 1op Priority.C

#ew $or% "imes. 0! January '!!'. Sec. L

Schattschneider$ #.#. "-!. "he *emisovereign People. New 4ork) :olt$ Qinehart$ and

Winston.

Scheufele$ Dietram L. "---. B8ramin5 as a 1heory of Jedia #ffects.C ,ournal of

4ommunication *-) "!0,"''.

Scheufele$ Dietram L. '!!!. BL5enda,settin5$ Primin5$ and 8ramin5 Qevisited) Lnother

0+

&ook at Ho5nitive #ffects of Political Hommunication.C 7ass 4ommunication ?

*ociet 0) '-+,0".

Schudson$ Jichael. "--.. "he Power of #ews. Hambrid5e$ JL) :arvard University

Press.

Shen$ 8uyuan$ and :eidi :atfield #dwards. '!!.. B#conomic %ndividualism$

:umanitarianism$ and Welfare Qeform) L Value,based Lccount of 8ramin5

#ffects.C ,ournal of 4ommunication ..) +-.,(!-

Sherman$ Steven J.$ Diane J. Jackie$ and Denise J. Driscoll. "--!. BPrimin5 and the

Differential Use of Dimensions in #valuation.C Personalit and *ocial

Pscholog &ulletin ") *!.,*"(.

Sieck$ Winston$ and J. 8rank 4ates. "--+. B#;position #ffects on Decision Jakin5.C

3rgani;ational &ehavior and <uman +ecision Processes +!EJuneF) '!+,'"-.

Simon$ :erbert L. "-... BL Aehavioral Jodel of Qational Hhoice.C .uarterl ,ournal of

/conomics -) --,""(.

Slothuus$ Qune. '!!($ BJore 1han Wei5htin5 Ho5nitive %mportance) L Dual,Process

Jodel of %ssue 8ramin5 #ffects.C Political Pscholog '-E"F) ",'(.

Slothuus$ Qune$ and Hlaes :. de Vreese. '!!-. BPolitical Parties$ Jotivated Qeasonin5$

and %ssue 8ramin5 #ffects.C Unpublished paper$ University of Larhus.

Sniderman$ Paul J. "--0. B1he New &ook in Public /pinion Qesearch.C %n Lda 8inifter

Eed.F Political *cience2 "he *tate of the +iscipline,'"-,'*.. Washin5ton$ DH)

Lmerican Political Science Lssociation.

Sniderman$ Paul J.$ and Sean J. 1heriault. '!!*. B1he Structure of Political Lr5ument

and the &o5ic of %ssue 8ramin5.C %n Willem #. Saris$ and Paul J. Sniderman

Eeds.F$ *tudies in Public 3pinion. Princeton$ NJ) Princeton University Press.

Stanovich$ 3eith #.$ and Qichard 8. West. "--(. B%ndividual Differences in 8ramin5 and

HonMunction #ffects.C "hin%ing and 6easoning *) '(-,0"+.

Stapel$ Diederik$ Willem 3oomen$ and Jarcel Reelenber5. "--(. B1he %mpact of

Lccuracy Jotivation on %nterpretation$ Homparison$ and Horrection Processes.C

,ournal of Personalit and *ocial Pscholog +*) (+(,(-0.

Strack$ 8rit>$ &eonard &. Jartin$ and Norbert Schwar>. "-((. BPrimin5 and

Hommunication) Social Determinants of %nformation Use in Jud5ments of &ife

Satisfaction.C /uropean ,ournal of *ocial Pscholog "() *'-,**'.

1akemura$ 3a>uhisa. "--*. B%nfluence of #laboration on the 8ramin5 of Decision.C "he

0(

,ournal of Pscholog "'() 00,0-.

1ankard$ James W.$ Jr.. '!!". B1he #mpirical Lpproach to the Study of Jedia 8ramin5.C

%n Stephen D. Qeese$ /scar :. 2andy$ and Lu5ust #. 2rant Eeds.F$ Framing

Public -ife. Jahwah$ NJ) &awrence #rlbaum Lssoc.