Professional Documents

Culture Documents

NIH Public Access: Author Manuscript

NIH Public Access: Author Manuscript

Uploaded by

Kiana TehraniCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- Biochemistry CasesTeenage Weakling 2015Document5 pagesBiochemistry CasesTeenage Weakling 2015Neel KotrappaNo ratings yet

- PRES3 RecallsDocument9 pagesPRES3 RecallsAhmed GendiaNo ratings yet

- Siegel ArticleDocument24 pagesSiegel ArticleAnon YmousNo ratings yet

- Abuse and Neglect in Nonparental Child CareDocument12 pagesAbuse and Neglect in Nonparental Child Carechamp8174782No ratings yet

- CP H58 Histology Competency ManualDocument61 pagesCP H58 Histology Competency ManualInn MironNo ratings yet

- Perpetrators Sexually: Characteristics Child Sexual Victimized Children Craissati, 1,2Document15 pagesPerpetrators Sexually: Characteristics Child Sexual Victimized Children Craissati, 1,2Eu DenyNo ratings yet

- Watkins 1992Document53 pagesWatkins 1992Gabriel Mercado InsignaresNo ratings yet

- Gender Differences in The Characteristics and Outcomes of Sexually Abused PreschoolersDocument21 pagesGender Differences in The Characteristics and Outcomes of Sexually Abused PreschoolersConstanza Torres JeldresNo ratings yet

- Brief Research ReportDocument10 pagesBrief Research ReportTramites GuardianesNo ratings yet

- Sosial,, Teori Sosial Kognitif BanduraDocument15 pagesSosial,, Teori Sosial Kognitif BandurasalwalfinaNo ratings yet

- Research Paper On Male RapeDocument19 pagesResearch Paper On Male RapesinemaNo ratings yet

- Early Child Maltreatment, Runaway Youths, and Risk of Delinquency and Victimization in Adolescence: A Mediational ModelDocument10 pagesEarly Child Maltreatment, Runaway Youths, and Risk of Delinquency and Victimization in Adolescence: A Mediational ModelJardan EcaterinaNo ratings yet

- Predicting Teenage Girls' Sexual Activity and Contraception Use: An Application of Matching LawDocument16 pagesPredicting Teenage Girls' Sexual Activity and Contraception Use: An Application of Matching LawPedro Pablo OchoaNo ratings yet

- HPE1023 Civil Engineering (Construction Safety) : Assignment 3: Term PaperDocument21 pagesHPE1023 Civil Engineering (Construction Safety) : Assignment 3: Term PaperJames AdrianNo ratings yet

- The Sexual Preferences of Incest OffendersDocument6 pagesThe Sexual Preferences of Incest OffendersSabrina PB100% (1)

- Crime & Delinquency 2008 Cernkovich 3 33Document31 pagesCrime & Delinquency 2008 Cernkovich 3 33Teodora RusuNo ratings yet

- JOUR175 Final Paper ExampleDocument10 pagesJOUR175 Final Paper ExampleLucy MurrayNo ratings yet

- Attachment, Abuse,: AmongDocument9 pagesAttachment, Abuse,: AmongJosé Augusto RentoNo ratings yet

- Eileen Vizard JCPP Review 171112Document27 pagesEileen Vizard JCPP Review 171112Ecaterina IacobNo ratings yet

- Is Earlier Sex Education HarmfulDocument10 pagesIs Earlier Sex Education Harmfulmac202123No ratings yet

- Cohen 2002Document14 pagesCohen 2002Victoria PeopleNo ratings yet

- Child Sexual Abuse - Michael Salter 2017 PDFDocument21 pagesChild Sexual Abuse - Michael Salter 2017 PDFHanashaumy AvialdaNo ratings yet

- JIV Version Preliminar Uso Interno UdecDocument36 pagesJIV Version Preliminar Uso Interno UdecMaruzzella ValdiviaNo ratings yet

- Available From Deakin Research OnlineDocument12 pagesAvailable From Deakin Research OnlineDanna MartínezNo ratings yet

- Why Prevention Why NowDocument7 pagesWhy Prevention Why NowDefendAChildNo ratings yet

- Offenders: Characteristics and TreatmentDocument22 pagesOffenders: Characteristics and TreatmentKiana TehraniNo ratings yet

- A Model of Vulnerability For Adult Sexual VictimizationDocument17 pagesA Model of Vulnerability For Adult Sexual VictimizationTramites GuardianesNo ratings yet

- The Experience of "Forgetting" Childhood Abuse A National Survey of PsychologistsDocument9 pagesThe Experience of "Forgetting" Childhood Abuse A National Survey of PsychologistsKathy KatyNo ratings yet

- Comparing Female - and Male - Perpetrated Child Sexual Abuse A Mixed-Methods AnalysisDocument21 pagesComparing Female - and Male - Perpetrated Child Sexual Abuse A Mixed-Methods AnalysisJeric C. ManaliliNo ratings yet

- InTech-A Review of Childhood Abuse Questionnaires and Suggested Treatment ApproachesDocument19 pagesInTech-A Review of Childhood Abuse Questionnaires and Suggested Treatment ApproacheskiraburgoNo ratings yet

- Regarding: InvestigationDocument14 pagesRegarding: InvestigationJosé Augusto RentoNo ratings yet

- A Counselor's Guide To Child Sexual Abuse: Prevention, Reporting and Treatment StrategiesDocument7 pagesA Counselor's Guide To Child Sexual Abuse: Prevention, Reporting and Treatment StrategiesReine Raven DavidNo ratings yet

- 5427 4350 1 PB PDFDocument18 pages5427 4350 1 PB PDFNurusshiami KhairatiNo ratings yet

- Female Sexual Abuseres of ChildrenDocument7 pagesFemale Sexual Abuseres of ChildrenFernando QuesadaNo ratings yet

- Cutajar CSA Psychopathology CAN Paper Proof 2010Document10 pagesCutajar CSA Psychopathology CAN Paper Proof 2010Cariotica AnonimaNo ratings yet

- Socio Cultural Factors and Young Sexual Offenders A Case Study of Western Madhya Pradesh IndiaDocument23 pagesSocio Cultural Factors and Young Sexual Offenders A Case Study of Western Madhya Pradesh IndiaMadalena SilvaNo ratings yet

- The Impact of Victim Alcohol Consumption and Perpetrator Use of Force On Perceptions in An Acquaintance Rape VignetteDocument13 pagesThe Impact of Victim Alcohol Consumption and Perpetrator Use of Force On Perceptions in An Acquaintance Rape VignetteZyra D. KeeNo ratings yet

- Determinants of Risky Sexual Behaviours Among Secondary School Students in Delta State NigeriaDocument12 pagesDeterminants of Risky Sexual Behaviours Among Secondary School Students in Delta State NigeriaEdlawit DamessaNo ratings yet

- Psychological Consequences of Sexual TraumaDocument11 pagesPsychological Consequences of Sexual Traumamary engNo ratings yet

- Artmother sonincestMichiganChildWelfareJl3 13PDFDocument8 pagesArtmother sonincestMichiganChildWelfareJl3 13PDF謝華寧No ratings yet

- Blurred Lines? Sexual Aggression and Barroom CultureDocument9 pagesBlurred Lines? Sexual Aggression and Barroom CultureJesseFerrerasNo ratings yet

- 008 - Estimating Age College Males Versus ConvictedDocument20 pages008 - Estimating Age College Males Versus ConvictedauranidiaherreraNo ratings yet

- Effectof Early Exposure On Pornography of Grade 12laurenceDocument16 pagesEffectof Early Exposure On Pornography of Grade 12laurenceJessie SaraumNo ratings yet

- Psychopathics Traits in Adolescent OffendersDocument25 pagesPsychopathics Traits in Adolescent OffendersТеодора ДелићNo ratings yet

- Physical Intimacy and Sexual Coercion Among Adolescent Intimate Partners in The PhilippinesDocument21 pagesPhysical Intimacy and Sexual Coercion Among Adolescent Intimate Partners in The PhilippinesMulat Pinoy-Kabataan News NetworkNo ratings yet

- 17108290Document20 pages17108290Johan Morales100% (1)

- AR TeenDatingViolenceDocument15 pagesAR TeenDatingViolenceKrisna Novian PrabandaruNo ratings yet

- Finkelhor1986 Risk Factors Child Sexual Abuse-DikonversiDocument29 pagesFinkelhor1986 Risk Factors Child Sexual Abuse-DikonversinurindahNo ratings yet

- Turchik 2015Document16 pagesTurchik 2015Rindha WidyaningsihNo ratings yet

- Child Sexual AbuseDocument36 pagesChild Sexual AbuseWislay 'sivivatu' Obwoge100% (1)

- Trends & Issues: Adolescence, Pornography and HarmDocument6 pagesTrends & Issues: Adolescence, Pornography and Harmbellydanceafrica9540No ratings yet

- RUNNING HEAD: Chemical Castration of Sex OffendersDocument25 pagesRUNNING HEAD: Chemical Castration of Sex OffendersSirIsaacs GhNo ratings yet

- Cumulative Trauma: The Impact of Child Sexual Abuse, Adult Sexual Assault, and Spouse AbuseDocument12 pagesCumulative Trauma: The Impact of Child Sexual Abuse, Adult Sexual Assault, and Spouse AbuseMaría Soledad LatorreNo ratings yet

- Harvey, T., & Elizabeth, L. J. (2020) - Attenuation of Deviant Sexual Fantasy Across The Lifespan in United States Adult MalesDocument20 pagesHarvey, T., & Elizabeth, L. J. (2020) - Attenuation of Deviant Sexual Fantasy Across The Lifespan in United States Adult MalesmarcaulesNo ratings yet

- Dissociation and Memory For Perpetration Among Convicted Sex OffendersDocument12 pagesDissociation and Memory For Perpetration Among Convicted Sex OffendersBłażej PorwołNo ratings yet

- J of Research On Adolesc - 2011 - Trickett - Child Maltreatment and Adolescent DevelopmentDocument18 pagesJ of Research On Adolesc - 2011 - Trickett - Child Maltreatment and Adolescent Developmentregina georgeNo ratings yet

- Wilson RiskofearlysexualinitiationchildwelfareDocument22 pagesWilson RiskofearlysexualinitiationchildwelfarejosawoodNo ratings yet

- Child Sexual Abuse - Demography, Impact, and InterventionsDocument15 pagesChild Sexual Abuse - Demography, Impact, and InterventionsraminemekNo ratings yet

- Adolescent Attitudes About RapeDocument4 pagesAdolescent Attitudes About RapeKiana TehraniNo ratings yet

- Cognitive Schemas and Sexual Offending - Differences Between Rapists, Pedophilic and Nonpedophilic Child Molesters, and Nonsexual OffendersDocument12 pagesCognitive Schemas and Sexual Offending - Differences Between Rapists, Pedophilic and Nonpedophilic Child Molesters, and Nonsexual OffendersFrancois BlanchetteNo ratings yet

- Juvenile Sex Offenders A Complex PopulationDocument6 pagesJuvenile Sex Offenders A Complex PopulationRoberto GalleguillosNo ratings yet

- CDC Inmunization ScheduleDocument4 pagesCDC Inmunization ScheduleppoaqpNo ratings yet

- A Pathologic Study of 924 Unselected Cases: The Attribution of Lung Cancers To Asbestos ExposureDocument6 pagesA Pathologic Study of 924 Unselected Cases: The Attribution of Lung Cancers To Asbestos ExposureKiana TehraniNo ratings yet

- 316 - A New Classification of NecrophiliaDocument5 pages316 - A New Classification of NecrophiliaKiana TehraniNo ratings yet

- Detection of Hepatitis C Virus RNA in Saliva of Patients With Active Infection Not Associated With Periodontal or Liver Disease SeverityDocument7 pagesDetection of Hepatitis C Virus RNA in Saliva of Patients With Active Infection Not Associated With Periodontal or Liver Disease SeverityKiana TehraniNo ratings yet

- Immunization To Protect The U.S. Armed Forces: Heritage, Current Practice, ProspectsDocument42 pagesImmunization To Protect The U.S. Armed Forces: Heritage, Current Practice, ProspectsKiana TehraniNo ratings yet

- How Proposition 9 (Marsy'S Law) Impacts LifersDocument1 pageHow Proposition 9 (Marsy'S Law) Impacts LifersKiana TehraniNo ratings yet

- Infectious DemoDocument26 pagesInfectious DemoKiana TehraniNo ratings yet

- 335 FullDocument14 pages335 FullKiana TehraniNo ratings yet

- The Manson Myth Debunking Helter Skelter and Exposing LiesDocument335 pagesThe Manson Myth Debunking Helter Skelter and Exposing LiesKiana Tehrani60% (5)

- Zeigler-Hill Southard Besser 2014Document6 pagesZeigler-Hill Southard Besser 2014Kiana TehraniNo ratings yet

- Chapter 3 PDFDocument13 pagesChapter 3 PDFKiana TehraniNo ratings yet

- EVC 2015 ProgrammeDocument24 pagesEVC 2015 ProgrammeguajacolNo ratings yet

- Blood Vessels CH 13Document86 pagesBlood Vessels CH 13Nalla Mirelle CarbonellNo ratings yet

- Communication Skills - Keys To Understanding by DR Fayza 2016Document121 pagesCommunication Skills - Keys To Understanding by DR Fayza 2016MohammadAbdurRahman100% (1)

- Clara CVDocument3 pagesClara CVClaraNo ratings yet

- JahnaviUdaikumar RESUME FinalDocument12 pagesJahnaviUdaikumar RESUME Finaljudaikumar1994No ratings yet

- Oneill Health Status Canada Vs UsDocument45 pagesOneill Health Status Canada Vs UsKhalid SukkarNo ratings yet

- Patient Specific Dental Hygiene Care PlanDocument8 pagesPatient Specific Dental Hygiene Care Planapi-354959885No ratings yet

- DiphtheriaDocument49 pagesDiphtheriasultanNo ratings yet

- BaOH2 PDFDocument5 pagesBaOH2 PDFGhana Cintai DiaNo ratings yet

- Amentia in Medical DiagnosisDocument10 pagesAmentia in Medical DiagnosisMónica C. GalvánNo ratings yet

- Perbedaan Waktu Pembekuan Darah Kapiler Dan Vena Pada Ibu Hamil Trimester IiiDocument11 pagesPerbedaan Waktu Pembekuan Darah Kapiler Dan Vena Pada Ibu Hamil Trimester IiiMuthia Qonita Khafidza TitaniaNo ratings yet

- Forensic Odontology A Review.20141212073749Document8 pagesForensic Odontology A Review.20141212073749Apri DhaliwalNo ratings yet

- Re Ca VADocument9 pagesRe Ca VAmanudanuNo ratings yet

- Insertion of Suppositories 2Document17 pagesInsertion of Suppositories 2Gayathry VijayakumarNo ratings yet

- The American Journal of Public HealthDocument3 pagesThe American Journal of Public HealthgautamkurtNo ratings yet

- ProvengeDocument7 pagesProvengeapi-675909478No ratings yet

- CHN Famorca SummaryDocument137 pagesCHN Famorca SummaryMIKAELA DAVIDNo ratings yet

- 5yj1qevlq - RUBRICS FOR CHN ACTIVITIES 2021Document8 pages5yj1qevlq - RUBRICS FOR CHN ACTIVITIES 2021Rovenick SinggaNo ratings yet

- PD QUALITY STANDARDS - 07082019 Edit - Ong SBDocument24 pagesPD QUALITY STANDARDS - 07082019 Edit - Ong SBNor Afzan Mohd TahirNo ratings yet

- Back Pain MaintenanceDocument61 pagesBack Pain MaintenanceVamierNo ratings yet

- Surgery PearlsDocument2 pagesSurgery Pearlspatriciaatan1497No ratings yet

- URINALYSIS & BODY FLUIds Pericardial Analysis.Document48 pagesURINALYSIS & BODY FLUIds Pericardial Analysis.Syazmin KhairuddinNo ratings yet

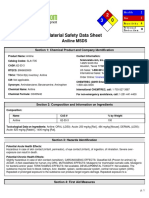

- Msds AnilinDocument6 pagesMsds Anilinikaa70No ratings yet

- LASA Blood SamplingDocument4 pagesLASA Blood SamplinggursinNo ratings yet

- General Care Ear Mould Hearing AidDocument16 pagesGeneral Care Ear Mould Hearing AidJess D'SilvaNo ratings yet

- Nursing Skills Checklist - RTDocument6 pagesNursing Skills Checklist - RTapi-309674272No ratings yet

- Preventive Therapy of Migraine: Pembimbing: Dr. Anyeliria Sutanto, SP.SDocument39 pagesPreventive Therapy of Migraine: Pembimbing: Dr. Anyeliria Sutanto, SP.SClaudia TariNo ratings yet

NIH Public Access: Author Manuscript

NIH Public Access: Author Manuscript

Uploaded by

Kiana TehraniOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

NIH Public Access: Author Manuscript

NIH Public Access: Author Manuscript

Uploaded by

Kiana TehraniCopyright:

Available Formats

Sex differences in childhood sexual abuse characteristics and

victims emotional and behavioral problems: Findings from a

national sample of youth

Andrea Kohn Maikovich-Fong

a

and Sara R. Jaffee

b

a

University of Pennsylvania, 3720 Walnut Street, Philadelphia, PA 19104, USA

b

Institute of Psychiatry, Kings College London, London, U.K

Abstract

ObjectiveThe first objective of this study was to test for sex differences in four childhood

sexual abuse characteristics---penetration, substantiation, perpetrator familial status, and multi-

maltreatment---in a national sample of youth. The second objective was to test for sex differences

in how these abuse characteristics were associated with victims emotional and behavioral

problems.

MethodsThe sample was drawn from the National Survey of Child and Adolescent Well-

Being, a sample of children investigated by United States child welfare services. Youth in the

current study (n =573, including 234 adolescents) were investigated for alleged sexual abuse.

Logistic regression and multivariate analysis of covariance were used to test for sex differences in

abuse characteristics, and to determine whether sex moderated associations between abuse

characteristics and emotional and behavioral problems.

ResultsGirls were more likely than boys to have their abuse substantiated and to experience

penetrative abuse (although differences in penetration status did not emerge among adolescents).

Substantiation status and child age were positively associated with caregiver-reported internalizing

and externalizing symptoms. Sex did not moderate the relationship between abuse characteristics

and youth emotional and behavioral problems.

ConclusionsSexual abuse characteristics might not be highly predictive factors when making

decisions about services needs. Furthermore, there may not be a strong empirical basis for

operating on the assumption that one sex is more vulnerable to negative consequences of abuse

than the other, or that abuse affects girls and boys differently. The processes explaining why some

victims exhibit more impairment than others are likely complex.

Introduction

Although childhood sexual abuse (CSA) was an unacknowledged and rarely studied

phenomenon until approximately thirty years ago, research has now firmly established that it

is a significant public health concern (e.g. Finkelhor, Hotaling, Lewis, & Smith, 1990).

Correspondence to: Andrea Kohn Maikovich-Fong.

The information and opinions expressed herein reflect solely the position of the authors. Nothing herein should be construed to

indicate the support or endorsement of its content by ACYF/DHHS.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our

customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of

the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be

discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

NIH Public Access

Author Manuscript

Child Abuse Negl. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2011 J une 1.

Published in final edited form as:

Child Abuse Negl. 2010 June ; 34(6): 429437. doi:10.1016/j.chiabu.2009.10.006.

N

I

H

-

P

A

A

u

t

h

o

r

M

a

n

u

s

c

r

i

p

t

N

I

H

-

P

A

A

u

t

h

o

r

M

a

n

u

s

c

r

i

p

t

N

I

H

-

P

A

A

u

t

h

o

r

M

a

n

u

s

c

r

i

p

t

Many victims experience pervasive developmental problems such as enuresis, somatic

complaints, sexually reactive behavior, and academic delays (Beitchman, Zucker, Hood, da

Casta, & Ackman, 1991; Kendall-Tackett, Williams, & Finkelhor, 1993; Trickett &

McBride-Chang, 1995), and sexual abuse victims are especially at risk for psychopathology

(Putnam, 2003; Trickett & McBride-Chang, 1995). While estimates vary widely, it is likely

that around 1 in 5 girls and 1 in 6 boys are victimized prior to age 18 (Centers for Disease

Control, 1997). However, despite evidence that a substantial number of victims are boys,

sexual abuse research findings are based disproportionately on female samples.

Consequently, the extent to which findings generalize to male victims is unclear. In addition,

the clinical utility of much of the existing literature is limited by heavy reliance on adult

retrospective reports of childhood abuse, and on case studies or qualitative studies whose

findings have not been empirically validated with quantitative research. The objectives of

the present study are to briefly review these limitations, and then to test empirically in a

national sample whether 1) there are sex differences in four childhood sexual abuse

characteristics---penetration versus non-penetration, substantiation status, perpetrator

familial status, and experiencing multiple forms of maltreatment, and 2) whether there are

sex differences in how these sexual abuse characteristics are associated with victims

emotional and behavioral problems (as measured by internalizing, externalizing, and trauma

symptoms).

Limitations to the extant literature

Preponderance of female samplesMuch of what is known about the developmental

correlates and sequelae of childhood sexual abuse is based on samples of exclusively female

victims (Bailey & McCloskey, 2005; Finkelhor, 1984; Valente, 2005). Due in large part to

the historical under-reporting and subsequent lack of awareness of male CSA, it was not

until the 1980s that researchers began to make concerted efforts to include male victims in

their samples (Finkelhor, 1984). Most sexual abuse researchers agree that the sexual abuse

of boys is still grossly under-reported (Briggs & Hawkins, 1995; Cermak & Molidor, 1996;

Porter, 1986). At least three factors likely contribute to this under-reporting. First, when the

abuser is male, boys may not report the abuse for fear they will be identified as gay (Cermak

& Molidor, 1996; Valente, 2005). Second, if the abuser is female, boys might interpret the

abuse as a culturally condoned sexual initiation experience for which they should feel

lucky rather than victimized (Dimock, 1988; Hunter, 1990). Third, sexual offenders

typically utilize more force and threats of violence with male than with female victims when

warning them not to report the abuse (Pierce & Pierce, 1985), so boys might feel more

intimidated than girls about reporting.

Although studies of sexually abused boys are becoming more common, exclusively male

samples are rare, usually consist of fewer than thirty participants (Feiring, Taska, & Lewis,

1999), and typically comprise adult men reporting retrospectively on their childhood abuse

experiences (Briggs & Hawkins, 1995; Dhaliwal, Gauzas, Antonowicz, & Ross, 1996;

Etherington, 1995). Furthermore, due to the low frequency with which males report sexual

abuse outside of a therapeutic or research setting (Valente, 2005), male sexual abuse

samples often comprise specialized groups such as incarcerated pedophiles, prison inmates,

and members of institutions such as the armed forces or boarding schools (Darves-Bornoz,

Choquet, Ledoux, Gasquet, & Manfredi, 1998), which are not necessarily representative of

the population of male victims.

Finally, due to small sample sizes of male victims, many current theories about how sexual

abuse affects boys and how various features of the abuse experience affect girls and boys

differently have been generated from case studies, anecdotal reports, and qualitative studies

(Dimock, 1988; Durham, 2003; Gilgun & Reiser, 1990; Krug, 1989). This important, in-

Maikovich-Fong and J affee Page 2

Child Abuse Negl. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2011 J une 1.

N

I

H

-

P

A

A

u

t

h

o

r

M

a

n

u

s

c

r

i

p

t

N

I

H

-

P

A

A

u

t

h

o

r

M

a

n

u

s

c

r

i

p

t

N

I

H

-

P

A

A

u

t

h

o

r

M

a

n

u

s

c

r

i

p

t

depth work has generated many useful observations and hypotheses; however,

complementary quantitative research is needed to test these hypotheses empirically.

Retrospective reporting of childhood sexual abuseMany studies of CSA and its

negative developmental sequelae have involved adults retrospectively reporting childhood

abuse (Finkelhor et al., 1990). Although these studies are valuable because they may include

individuals who never reported abuse as children (Kendall-Tackett & Becker-Blease, 2004),

Widom and others have highlighted the importance of also conducting research with youth

samples because findings often differ from those of retrospective studies (Raphael, Widom,

& Lange, 2001; Widom, Weiler, & Cottler, 1999). Moreover, Hardt and Rutter (2004)

identified significant measurement error in retrospective studies, particularly when

individuals were asked to recall how they felt about events at the time they were happening.

As many studies aim to identify associations between the experience of CSA and

psychological well-being, there is clearly a need for additional studies in this field that

utilize youth samples.

Current research needs

Some evidence suggests that sexual abuse might affect boys and girls differently, and that

the prevalence of certain characteristics of the sexual abuse experience might differ for boys

and girls (Bauserman & Rind, 1997; Darves-Bornoz et al., 1998; Feiring et al., 1999;

Finkelhor et al., 1990; Fontanella, Harrington, & Zuravin, 2000; Friedrich, Urquiza, &

Beilke, 1986; Gold, Elhai, Lucenko, & Swingle, 1998; Kendall-Tackett & Simon, 1992). For

example, female adolescent sexual abuse victims have been shown to display more somatic

complaints and mood disorders than male victims, whereas males have been shown to

display more behavioral problems than females (Darves-Bornoz et al., 1998). However,

some researchers have not found sex differences in the effects of CSA (Calam, Horne,

Glasgow, & Cox, 1998; Young, Bergandi, & Titus, 1994), and at least one study has found

that male adolescent victims tend to exhibit more emotional, behavioral, and suicidal

problems than their female counterparts (Garnefski & Diekstra, 1997).

Characteristics of the abuse experience have also been shown to differ for girls and boys.

One review paper found that the estimated percentage of male victims perpetrators who are

themselves male ranges from 18 to 97, depending on the study, and that the estimated

percentage of male perpetrators for female victims ranges from 80 to 100 (Dhaliwal et al.,

1996). Another study of early childhood victims found that boys were more likely to

experience fondling and oral intercourse than girls, whereas girls were more likely to

experience penetrative abuse (Fontanella et al., 2000). Finally, girls may be more likely to

be sexually abused by family members, whereas boys may be more likely to be abused by

strangers (Finkelhor et al., 1990; Gold et al., 1998). Existing studies suggest that certain

characteristics of the abuse experience, including the use of force and coercion, penetration,

familial perpetrators, and longer duration of abuse, are associated with more negative

outcomes (Beitchman et al., 1991; Browne & Finkelhor, 1986; Estes & Tidwell, 2002;

Friedrich et al., 1986; Molnar, Buka, & Kessler, 2001).

In short, given how little is known about male sexual abuse victims in general, and how little

is known about sex differences in the experience and consequences of childhood sexual

abuse, it is important to test empirically whether potentially important abuse characteristics

differ in their rates and consequences for males and females in a national sample of victims

still in their youth. Social workers and clinicians working with sexually abused children

within the confines of limited time and resources need a solid body of evidence to which

they can refer in order to implement the most empirically-grounded assessments and

treatments possible. Furthermore, some researchers and clinicians continue to operate on the

Maikovich-Fong and J affee Page 3

Child Abuse Negl. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2011 J une 1.

N

I

H

-

P

A

A

u

t

h

o

r

M

a

n

u

s

c

r

i

p

t

N

I

H

-

P

A

A

u

t

h

o

r

M

a

n

u

s

c

r

i

p

t

N

I

H

-

P

A

A

u

t

h

o

r

M

a

n

u

s

c

r

i

p

t

assumption that boys are, in general, less adversely affected by childhood sexual abuse than

are girls, but this may be a potentially dangerous assumption to operate on without solid

empirical supporting evidence.

While it is important to examine how abuse characteristics affect boys and girls differently

across childhood, it may be especially important to focus on the subpopulation of

adolescents, as it is during this stage of life that youth experience the normative emergence

of sexuality and sexual identity. These processes may be compromised and complicated by

sexual abuse, leading to symptoms of psychopathology (Berliner & Conte, 1990; Durham,

2003). Furthermore, adolescence is a time of emerging self-identity and self-awareness

(Erikson, 1968), and adolescents may question their own motives more and experience more

self-blame for abuse than younger children (Celano, 1992; Myers, 1989).

The current study addresses the questions of whether the prevalence of different abuse

characteristics differs for male and female victims, and whether there are sex differences in

the association between sexual abuse characteristics and youth emotional and behavioral

problems. We first examine these questions in a sample of children ranging in age from 4 to

16 years, and then focus on youth aged 11 years and older. In light of the existing literature,

we predict that girls will experience higher rates of penetrative abuse and will more

frequently have familial perpetrators than boys, and that because these are the characteristics

most associated with psychopathology, girls will have higher rates of psychopathology

symptoms than boys. However, we also predict that child sex will not moderate the

association between different abuse characteristics and childrens difficulties (i.e., that these

characteristics will be equally associated with psychopathology in boys and girls).

Nonetheless, given the limitations to the existing literature in this field, this study is largely

exploratory.

Method

Participants

The National Survey of Child and Adolescent Well-Being (NSCAW) is a nationally-

representative sample of United States children who have had contact with Child Protective

Services (Dowd et al., 2004). The full cohort includes 5,501 children (50% female), less

than 1 year to 16 years of age when sampled, who were subjects of child abuse or neglect

investigations conducted by CPS from October 1999 to December 2000. Participants in the

NSCAW study gave informed consent to enroll in the study, and the study procedures were

approved by the participating universities Institutional Review Boards. Additional

information about sample composition is available from Dowd and colleagues (Dowd,

Kinsey, Wheeless, & NSCAW Research Group, 2004). The present studys sample is

restricted to children who, according to caseworker reports, were investigated as alleged

victims of sexual abuse. Interviews were collected 26 months following the close of the

CPS investigations. Children who were members of the same household as a previously

selected child were not eligible to participate in the study, in order to limit the burden on

families. Therefore, there are not any siblings included in the NSCAW sample.

Analyses were conducted with two subsets of youth. The first subset, the child and

adolescent sample (n =573; 72% female), comprised children 4 years or older (M =9.46

years; SD =3.28). Fifty percent of children in the child and adolescent sample were White

(non-Hispanic), 23% were Black (non-Hispanic), 18% were Hispanic, and 8% were of other

races or ethnicities. The second subset, the adolescent sample (n =234; 82% female),

consisted of youth 11 years or older (M =12.82 years; SD =1.28). Forty-eight percent of

children in the adolescent sample were White (non-Hispanic), 26% were Black (non-

Maikovich-Fong and J affee Page 4

Child Abuse Negl. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2011 J une 1.

N

I

H

-

P

A

A

u

t

h

o

r

M

a

n

u

s

c

r

i

p

t

N

I

H

-

P

A

A

u

t

h

o

r

M

a

n

u

s

c

r

i

p

t

N

I

H

-

P

A

A

u

t

h

o

r

M

a

n

u

s

c

r

i

p

t

Hispanic), 20% were Hispanic, and 7% were of other races or ethnicities. 90% of caregivers

in the sample were female, and the average annual income of families was $19,000.

Measures

Internalizing and externalizing symptomsCaregivers were administered the Child

Behavior Checklist (CBCL), which includes an externalizing scale comprising delinquent

and aggressive behavior domains, and an internalizing scale comprising withdrawn

behavior, somatic complaints, and anxious/depressed domains (Achenbach, 1991a).

Caregivers were asked 113 questions on a 3-point Likert-type scale (0 =not true, 1 =

somewhat or sometimes true, 2 =very true or often true). Internal consistency reliabilities

were high for both externalizing ( =.92) and internalizing ( =.90) scales. Childrens age-

and gender-standardized T scores were used in all analyses. T scores at or above 65 are

considered clinically significant because this cut-off has been shown to significantly

discriminate between children referred for mental health treatment and matched children

who are not referred (Achenbach & Rescorla, 2001).

Youth in the adolescent sample were administered the Youth Self-Report (Achenbach,

1991b), which contains 113 questions similar to those in the CBCL. Internal consistency

reliability was high ( =.90 externalizing, =.90 internalizing). Youths age- and gender-

standardized T scores were used in all analyses. The correlation between caregiver and

youth reports of externalizing symptoms in the adolescent sample was 0.40, and the

correlation for internalizing symptoms was 0.39 (both significant at the p <.01 level). This

magnitude of agreement among informants is standard (Achenbach, McConaughy, &

Howell, 1987). Given that parent and child reports of psychopathology do not correlate

perfectly, and that adolescents may be in a better position to report on their own emotional

and behavioral functioning than caregivers, it is important to examine both youth and

caregiver reports of psychological functioning when available.

Trauma symptomsYouth in the adolescent sample were administered the Post

Traumatic Stress Disorder section of a version of the Trauma Symptom Checklist for

Children adapted for NSCAW (Briere, 1996). The measure included ten questions asking

children to describe how often they experienced various symptoms (1 =never; 2 =

sometimes; 3 =lots of times; 4 =almost all of the time). For example, youth were asked

how often they have bad dreams or nightmares, and how often scary ideas or pictures just

pop into [their] head. Internal consistency reliability on this measure was adequate ( =

0.84). Again, youths age- and gender-standardized T scores were used in all analyses, and T

scores at or above 65 are considered clinically significant (Briere, 1996).

Abuse characteristicsCaseworkers indicated whether or not the alleged abuse was

substantiated (0 =no; 1 =yes). They also categorized the nature of the childs sexual abuse

experience, which we transformed into a dichotomous variable indicating whether the abuse

was penetrative (1) or non-penetrative (0). Penetrative abuse included vaginal/anal

intercourse, digital penetration of the vagina/anus, and oral copulation of an adult if the

perpetrator was male. Non-penetrative abuse included fondling/molestation, masturbation,

oral copulation of the child, oral copulation of an adult if the perpetrator was female, and

other less severe types. Finally, caseworkers indicated other types of maltreatment

children experienced. We transformed this information into a dichotomous variable

indicating whether children experienced multiple forms of maltreatment (physical, neglect,

or emotional in addition to sexual; 1) or only sexual abuse (0). Caseworkers also indicated

who the alleged perpetrator was, from which we classified them as familial (1) or non-

familial (0). Familial perpetrators included mothers, fathers, step-mothers, step-fathers,

grandmothers, grandfathers, aunts, uncles, brothers, sisters, and other relatives. Non-familial

Maikovich-Fong and J affee Page 5

Child Abuse Negl. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2011 J une 1.

N

I

H

-

P

A

A

u

t

h

o

r

M

a

n

u

s

c

r

i

p

t

N

I

H

-

P

A

A

u

t

h

o

r

M

a

n

u

s

c

r

i

p

t

N

I

H

-

P

A

A

u

t

h

o

r

M

a

n

u

s

c

r

i

p

t

perpetrators included mothers boyfriends, neighbors, strangers, friends, and child care

providers.

Analysis approach

Logistic regression was used to test the hypotheses that girls were more likely than boys to

have experienced penetrative abuse and to have familial perpetrators. Two multivariate

analyses of covariance (MANCOVAs) were conducted to test whether there were sex

differences in the association between abuse characteristics and youth emotional and

behavioral problems in the child and adolescent sample and the adolescent sample.

Statistical approaches that require omnibus test significance before examining specific

contrasts are most appropriate when the research question has yielded limited and/or mixed

results in the extant literature (Burchinal & Clarke-Stewart, 2007), such as the current

research question. This type of conservative analysis approach minimizes the risk of Type I

error, unlike alternative a priori comparison approaches such as regression (Kirk, 1982).

Given that the NSCAW weights are highly variant whole sample weights, they are not

appropriate to use with small subsamples, and so were not used in these analyses. All

analyses were conducted using SPSS 14.0 (2005).

Results

Missing data

Missing data ranged from less than 1% for measures of emotional and behavioral problems

to 26% for characteristics of the sexual abuse. Because analyses based on listwise-deleted

data have been shown to generate biased and inefficient parameter estimates (Schafer &

Graham, 2002), multiple imputation was used to generate a set of complete observations for

all sample members. Five multiply imputed data sets were created using the Stata 9.0

(StataCorp, 2005) user-written add-on program ICE (Imputation by Chained Equations)

(Royston, 2005). ICE imputes missing values using an iterative regression switching

procedure (Royston, 2004; Royston, 2005). By default, ICE uses linear regression to

estimate values for any incomplete continuous variable, and logistic regression to estimate

values for any incomplete dichotomous variable. The imputed values are obtained by

sampling from the distribution of the incomplete variable, given the observed values and

explanatory variables included in the predictive model. One advantage of ICE is that it does

not assume normality of the joint multivariate distribution of variables, so different types of

variables (e.g., continuous, categorical) can be imputed simultaneously. For a description of

how ICE combines the estimates and obtains standard errors, see Carlin, Li, Greenwood, and

Coffey (2003).

Descriptive data and correlations among variables

Tables 1 and 2 provide descriptive statistics for abuse characteristics and childrens

psychopathology symptoms. Table 3 provides a correlation matrix displaying relationships

among all analysis variables. Statistically significant correlations were small in magnitude,

indicating that multicollinearity was not a problem.

Sex differences in the likelihood of experiencing different abuse characteristics

Logistic regression analyses revealed some sex differences in the likelihood of experiencing

different sexual abuse characteristics. Girls in the child and adolescent sample had

significantly higher odds of having their abuse substantiated and of experiencing penetrative

abuse (Table 1). Girls and boys were equally likely to have a familial perpetrator and to

experience multiple forms of maltreatment. In the adolescent sample, girls were more likely

Maikovich-Fong and J affee Page 6

Child Abuse Negl. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2011 J une 1.

N

I

H

-

P

A

A

u

t

h

o

r

M

a

n

u

s

c

r

i

p

t

N

I

H

-

P

A

A

u

t

h

o

r

M

a

n

u

s

c

r

i

p

t

N

I

H

-

P

A

A

u

t

h

o

r

M

a

n

u

s

c

r

i

p

t

than boys to have their abuse substantiated, but did not differ from boys on any of the other

three abuse characteristics.

Sex differences in associations between abuse characteristics and youth emotional and

behavioral problems

The MANCOVA conducted with the child and adolescent sample included the dependent

variables of caregiver-rated internalizing and externalizing symptoms. The childs age was

entered as a covariate, and five variables were entered as fixed effects: child sex, penetration

status, substantiation status, perpetrator familial status, and multiple maltreatment status.

The multivariate test (Wilks Lambda) was significant for substantiation status and child age

(Table 4). The univariate tests of substantiation and age were significant for externalizing

and internalizing symptoms. Children with substantiated abuse cases had higher

externalizing (M =60.75, SD =12.09) and internalizing (M =57.96, SD =11.35) scores than

children with unsubstantiated cases (externalizing M =57.84, SD =12.64; internalizing M =

55.31, SD =11.74). Older children had more externalizing and internalizing symptoms than

younger children. No other multivariate test for main or interactive effects was significant.

A second MANCOVA was conducted to investigate sex differences in the association

between abuse characteristics and youth emotional and behavioral problems within the

adolescent sample. The dependent variables were caregiver-reported internalizing and

externalizing symptoms and youth-reported internalizing, externalizing, and trauma

symptoms. Covariates and fixed effects were identical to those in the analysis of the child

and adolescent sample. No multivariate test for main or interactive effects was significant,

with the exception of one uninterpretable result. Specifically, the multivariate test (Wilks

Lambda) was significant for penetration. However, the univariate test of penetration was not

significant for any outcome measure (full analyses available upon request).

Discussion

This study contributes to the limited body of quantitative research that examines sex

differences in the experience and psychological sequelae of childhood sexual abuse in youth

samples. The study had several methodological strengths. First, the samples were relatively

large by sexual abuse sample standards, and were drawn from a national sample of children

involved with the United States CPS system. Second, the samples included enough male

victims to allow for tests of sex differences in the rates and correlates of specific abuse

characteristics. Third, the NSCAW dataset included information about a number of

potentially important sexual abuse characteristics. Fourth, the sample was large enough to

allow for tests of sex differences in the effects of abuse specifically among adolescents, for

whom issues of sexual identity are especially salient. Youth reports of their own emotional

and behavioral functioning were also available for adolescents in this sample.

Implications for future research

The analyses revealed sex differences in the prevalence of two abuse characteristics: girls

were more likely than boys to have their abuse substantiated, and girls in the child and

adolescent sample were more likely to experience penetrative abuse. The sex differences in

substantiation rates is interesting, and might reflect either a true sex difference, or a bias in

what types of cases end up substantiated by CPS. While differentiating between these two

potential explanations is outside the scope of the present paper, it is an important question to

examine in future studies because there may be a subset of victims, such as boys,

particularly at-risk for having their abuse unsubstantiated. Furthermore, there may be a

subset of victims at risk for having their abuse undetected and/or unreported in the first

place. For example, perhaps young boys who experience penetrative abuse are particularly

Maikovich-Fong and J affee Page 7

Child Abuse Negl. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2011 J une 1.

N

I

H

-

P

A

A

u

t

h

o

r

M

a

n

u

s

c

r

i

p

t

N

I

H

-

P

A

A

u

t

h

o

r

M

a

n

u

s

c

r

i

p

t

N

I

H

-

P

A

A

u

t

h

o

r

M

a

n

u

s

c

r

i

p

t

at-risk for not having their abuse detected and reported to CPS, due in part to societal lack of

awareness of sexual abuse of young boys, and/or perpetrators more concerted efforts to

hide their abuse of boys.

Despite some sex differences in the prevalence of abuse characteristics, there were not any

sex differences in the severity of internalizing, externalizing, or trauma symptoms. Although

other studies have shown that males and females respond differently to sexual abuse (e.g.,

Bauserman & Rind, 1997; Friedrich et al., 1986), many of those studies identified sex

differences in specific symptoms like nightmares and somatic complaints (Darves-Bornoz et

al., 1998), whereas the present study examined broad categories of mental health symptoms.

Thus, there may be sex differences in the association between sexual abuse and specific

psychopathology symptoms, but not many differences at more global levels. Methodological

differences among studies could also account for discrepant findings. Many studies that have

found sex differences either utilized child samples with smaller age ranges than the present

sample (Fontanella et al., 2000), or used samples of adults reporting retrospectively on

childhood abuse (Bauserman & Rind, 1997; Dhaliwal et al., 1996). Although these

methodological differences make cross-study comparisons difficult, the present results,

combined with those from other studies that failed to find sex differences in how sexual

abuse affects childrens mental health (Calam et al., 1998; Young et al., 1994), suggest that

further study is needed before researchers, social workers, and clinicians can conclude that

sexual abuse is more psychologically damaging for one sex than the other.

Furthermore, it is possible that small sample sizes have detracted researchers from

publishing studies about sex differences in the experience and consequences of sexual abuse.

For example, if analyses that yield null results have been attributed to small sample sizes

and have remained unpublished, and if the few studies that have yielded sex differences

(true differences or those produced as a result of Type I error) have been published, then the

literature base in this field may be biased. In other words, it is possible that the file drawer

problem, in which researchers fail to publish non-significant findings (Rosenthal, 1979),

may be operating within this field due to the small sizes of samples that include males. It is

important, then, that more studies such as the present one enter the literature base not only

for the information they contain individually, but also to inform future meta-analyses.

This study did not examine the role of perpetrator sex in sexually abused girls and boys

symptomatology, because information on perpetrator sex was missing for many children and

the number of youth with known female perpetrators was very small. However, researchers

with access to samples that include more youth with female perpetrators should test the

qualitatively-derived hypothesis that having a male perpetrator may be particularly

damaging for male adolescent victims because they are in a stage of development in which

issues related to sexuality are normatively expected to emerge (Durham, 2003; Erikson,

1968). For example, in one practitioner study, male victims sexually abused by men during

adolescence expressed significant concerns about their sexuality, and fear that their peers

would learn of the abuse and consider them gay as a result of it (Durham, 2003). Given that

there is a natural biological increase in sexual drives and sexual awareness during

adolescence (Moore & Rosenthal, 1993), male victims sexually abused by men often report

feeling some physical pleasure during the abuse, which is associated with extreme shame

and confusion about the experience, their sexuality, and their sexual identities (Durham,

2003). Furthermore, it is possible that boys sexually abused by women may be particularly

unlikely to report their abuse. Thus, this is an important domain of study for future research

efforts.

Maikovich-Fong and J affee Page 8

Child Abuse Negl. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2011 J une 1.

N

I

H

-

P

A

A

u

t

h

o

r

M

a

n

u

s

c

r

i

p

t

N

I

H

-

P

A

A

u

t

h

o

r

M

a

n

u

s

c

r

i

p

t

N

I

H

-

P

A

A

u

t

h

o

r

M

a

n

u

s

c

r

i

p

t

Implications for clinical intervention

Although victims in the child and adolescent sample whose abuse was substantiated had

more externalizing and internalizing symptoms than victims with unsubstantiated abuse,

these results did not replicate within the adolescent sample. Furthermore, neither familial

perpetrator status nor multiple maltreatment predicted differences in emotional or behavioral

problems in either sample, despite the relatively large sample sizes. These findings suggest

that it may be problematic to assume that a child is a low priority for intervention services

because he/she did not have his/her abuse substantiated (especially among adolescents), or

because the abuse did not fit a profile of what is typically perceived of as more severe.

Assuming that an adolescent is less at risk for behavioral, emotional, and social difficulties

because their sexual abuse was not substantiated, for example, may result in missing

multiple survivors in need of treatment.

The present study also tested whether the association between sexual abuse characteristics

and emotional and behavioral problems differed in males and females. In the child and

adolescent sample and in the adolescent sample, there were no significant interactions

between child sex and sexual abuse characteristics. Thus, although certain characteristics of

sexual abuse are more common in females than males, these characteristics appear to affect

girls and boys similarly. In sum, this study suggests that it may not be particularly

straightforward to design abuse severity profiles for risk assessments based on abuse

characteristics or victim sex alone or in combination. Furthermore, it is important for

clinicians to assess for various types of psychopathology as comprehensively in males as in

females, given that child sex does not appear to be a moderator of the relationship between

abuse characteristics and child outcomes. Finally, although age was not a focal variable of

this study, age did emerge as a significant predictor of childrens psychopathology

symptoms. This suggests that it may be important to ensure that young adolescents mental

health needs are not neglected, and that age-appropriate treatments for older youth continue

to be developed and implemented.

Limitations

Although the sample sizes were relatively large by previous study standards, power to detect

sex differences in emotional and behavioral problems, abuse characteristics, and the

association between abuse characteristics and emotional and behavioral problems was still

limited in the adolescent subsample. Second, while this study considered four characteristics

that can differ among sexual abuse experiences, there are other potentially important

characteristics that were not examined, such as duration, age-of-onset of abuse, and

perpetrator sex. Third, it is likely that the children in this sample were also experiencing

other types of stressors, such as poverty and community violence, that may also have been

contributing to their emotional and behavioral problems, and that may have been

differentially predictive for males and females. This study does not tease apart the unique

contribution of sexual abuse or shed any light on how childrens contexts further moderate

experiences of abuse on their psychological well-being. Fourth, this study examined

childrens emotional and behavioral symptoms, not explicit diagnoses.

Fifth, there was not enough statistical power to consider how girls and boys of different

races and ethnicities were affected by characteristics of the abuse experience, and the only

variable related to race or ethnicity in the NSCAW dataset was the childs race, identified by

caregivers as one of a limited set of forced choices. The cultures in which children of

different races and ethnicities grow up may shape very different understandings of sexual

abuse experiences, and the balance of risk and protective factors that characterize sexually

abused boys and girls may vary greatly as a function of race and ethnicity. Thus, it is not

clear that our findings will generalize to racial and ethnic subgroups. Whereas child sex did

Maikovich-Fong and J affee Page 9

Child Abuse Negl. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2011 J une 1.

N

I

H

-

P

A

A

u

t

h

o

r

M

a

n

u

s

c

r

i

p

t

N

I

H

-

P

A

A

u

t

h

o

r

M

a

n

u

s

c

r

i

p

t

N

I

H

-

P

A

A

u

t

h

o

r

M

a

n

u

s

c

r

i

p

t

not emerge as a moderator in this study, it is possible that other demographic and contextual

factors---such as the childs ethnicity and/or culture---may serve as moderators. Sixth, the

imputation procedure we used assumes that data are missing completely at random

(MCAR). To the extent that this is not true, our results may be biased. Seventh, one of our

hypotheses (that child sex will not moderate the association between abuse characteristics

and childrens difficulties) was a null hypothesis. One possibility is that this hypothesis was

confirmed due to limited power to detect a moderating effect, rather than a true lack of

moderation.

Despite these limitations, the present study provides new quantitative data on sex differences

in the likelihood of experiencing different sexual abuse characteristics, and the ways in

which sex moderates the association between these characteristics and childrens emotional

and behavioral problems. The national nature of the sample, the samples size, and the fact

that victims in the sample were still in their youth contribute to the novelty and strength of

the study. Nonetheless, significantly more research on sex differences in childrens

responses to sexual abuse (and other types of abuse and trauma) is needed before clinicians

and intervention specialists can design and implement the most empirically-grounded

assessments and treatments possible for this vulnerable population of youth. Given the

inherent dangers of the file drawer problem, in which researchers fail to publish findings that

show few significant differences (Rosenthal, 1979), it is crucial that studies such as the

present one enter the literature base.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grant HD050691 fromthe National Institute of Child Health and Human Development

to S. J affee. This document includes data fromthe National Survey of Child and Adolescent Well-Being, which

was developed under contract with the Administration on Children, Youth, and Families, U.S. Department of

Health and Human Services (ACYF/DHHS). The data have been provided by the National Data Archive on Child

Abuse and Neglect.

References

Achenbach, TM. Manual for the child behavior checklist 418 and 1991 profile. Burlington:

Department of Psychiatry, University of Vermont; 1991a.

Achenbach, TM. Manual for the youth self-report and 1991 profile. Burlington: Department of

Psychiatry, University of Vermont; 1991b.

Achenbach TM, McConaughy SH, Howell CT. Child/adolescent behavioral and emotional problems:

Implication of cross-informant correlations for situational specificity. Psychological Bulletin

1987;101:213232. [PubMed: 3562706]

Achenbach, TM.; Rescorla, LA. Manual for ASEBA school-age forms & profiles. Burlington, VT:

University of Vermont, Research Center for Children, Youth, & Families; 2001.

Bailey J A, McCloskey LA. Pathways to adolescent substance use among sexually abused girls. J ournal

of Abnormal Child Psychology 2005;33:3953. [PubMed: 15759590]

Bauserman R, Rind B. Psychological correlates of male child and adolescent sexual experiences with

adults: A review of the nonclinical literature. Archives of Sexual Behavior 1997;26:181210.

[PubMed: 9101033]

Beitchman J H, Zucker KJ , Hood J E, da Casta GA, Ackman D. A review of the short-term effects of

child sexual abuse. Child Abuse & Neglect 1991;15:537556. [PubMed: 1959086]

Berliner L, Conte J R. The process of victimization: The victims perspective. Child Abuse & Neglect

1990;14:2940. [PubMed: 2310971]

Briere, J . Trauma symptom checklist for children: Professional manual. Florida: Psychological

Assessment Resources, Inc; 1996.

Briggs F, Hawkins RMF. Protecting boys from the risk of sexual abuse. Early Child Development and

Care 1995;110:1932.

Maikovich-Fong and J affee Page 10

Child Abuse Negl. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2011 J une 1.

N

I

H

-

P

A

A

u

t

h

o

r

M

a

n

u

s

c

r

i

p

t

N

I

H

-

P

A

A

u

t

h

o

r

M

a

n

u

s

c

r

i

p

t

N

I

H

-

P

A

A

u

t

h

o

r

M

a

n

u

s

c

r

i

p

t

Browne A, Finkelhor D. The impact of child sexual abuse: A review of the research. Psychological

Bulletin 1986;99:6677. [PubMed: 3704036]

Burchinal MR, Clarke-Stewart KA. Maternal employment and child cognitive outcomes: The

importance of analytic approach. Developmental Psychology 2007;43:11401155. [PubMed:

17723041]

Calam R, Horne L, Glasgow D, Cox A. Psychological disturbance and child sexual abuse: A follow-up

study. Child Abuse & Neglect 1998;22:901913. [PubMed: 9777260]

Carlin J B, Li N, Greenwood P, Coffey C. Tools for analyzing multiple imputed datasets. Stata J ournal

2003;3:226244.

Celano MP. A developmental model of victims internal attributions of responsibility for sexual abuse.

J ournal of Interpersonal Violence 1992;7:5769.

Centers for Disease Control. Adverse Childhood Experiences Study. 1997. Retrieved February 22,

2009, from http://www.cdc.gov/nccdphp/ace/prevalence.htm

Cermak P, Molidor C. Male victims of child sexual abuse. Child & Adolescent Social Work J ournal

1996;13:385400.

Darves-Bornoz J M, Choquet M, Ledoux S, Gasquet I, Manfredi R. Gender differences in symptoms of

adolescents reporting sexual assault. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology

1998;33:111117. [PubMed: 9540385]

Dhaliwal GK, Gauzas L, Antonowicz DH, Ross RR. Adult male survivors of childhood sexual abuse:

Prevalence, sexual abuse characteristics, and long-term effects. Clinical Psychology Review

1996;16:619639.

Dimock PT. Adult males sexually abused as children: Characteristics and implications for treatment.

J ournal of Interpersonal Violence 1988;3:203221.

Dowd, K.; Kinsey, S.; Wheeless, S. NSCAW Research Group. National survey of child and adolescent

well-being (NSCAW): Wave 1 data file users manual. Research Triangle Park, NC: Research

Triangle Institute; 2004.

Dowd, K.; Kinsey, S.; Wheeless, S.; Thissen, R.; Richardson, J .; Suresh, R.; Mierzwa, F.; Biemer, P.;

J ohnson, I.; Lytle, T. National survey of child and adolescent well-being (NSCAW): Combined

waves 14 data file users manual. Ithaca, NY: National Data Archive on Child Abuse and

Neglect; 2004.

Durham A. Young men living through and with child sexual abuse: A practitioner research study.

British J ournal of Social Work 2003;33:309323.

Etherington K. Adult male survivors of childhood sexual abuse. Counselling Psychology Quarterly

1995;8:233241.

Erikson, E. Identity, youth, and crisis. New York: Norton; 1968.

Estes LS, Tidwell R. Sexually abused childrens behaviours: Impact of gender and mothers

experience of inra- and extra-familial sexual abuse. Family Practice 2002;19:3644. [PubMed:

11818348]

Feiring C, Taska L, Lewis M. Age and gender differences in childrens and adolescents adaptation to

sexual abuse. Child Abuse & Neglect 1999;23:115128. [PubMed: 10075182]

Finkelhor, D. Child sexual abuse: Theory and research. New York: Free Press; 1984.

Finkelhor D, Hotaling G, Lewis IA, Smith C. Sexual abuse in a national survey of adult men and

women: Prevalence, characteristics, and risk factors. Child Abuse & Neglect 1990;14:1928.

[PubMed: 2310970]

Fontanella C, Harrington D, Zuravin SJ . Gender differences in the characteristics and outcomes of

sexually abused preschoolers. J ournal of Child Sexual Abuse 2000;9:2140.

Friedrich WN, Urquiza AJ , Beilke RL. Behavior problems in sexually abused young children. J ournal

of Pediatric Psychology 1986;11:4757. [PubMed: 3958867]

Garnefski N, Diekstra RFW. Child sexual abuse and emotional and behavioral problems in

adolescence: Gender differences. J ournal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent

Psychiatry 1997;36:323329. [PubMed: 9055512]

Gilgun J F, Reiser E. The development of sexual identity among men sexually abused as children.

Families in Society 1990;71:515523.

Maikovich-Fong and J affee Page 11

Child Abuse Negl. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2011 J une 1.

N

I

H

-

P

A

A

u

t

h

o

r

M

a

n

u

s

c

r

i

p

t

N

I

H

-

P

A

A

u

t

h

o

r

M

a

n

u

s

c

r

i

p

t

N

I

H

-

P

A

A

u

t

h

o

r

M

a

n

u

s

c

r

i

p

t

Gold SN, Elhai J D, Lucenko BA, Swingle J M. Abuse characteristics among childhood sexual abuse

survivors in therapy: A gender comparison. Child Abuse & Neglect 1998;22:10051012.

[PubMed: 9793723]

Hardt J , Rutter M. Validity of adult retrospective reports of adverse childhood experiences: Review of

the evidence. J ournal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry 2004;45:260273. [PubMed: 14982240]

Hunter, M. Abused boys: The neglected victims of sexual abuse. New York: Fawcett Columbine;

1990.

Kendall-Tackett K, Becker-Blease K. The importance of retrospective findings in child maltreatment

research. Child Abuse & Neglect 2004;28:723727. [PubMed: 15261467]

Kendall-Tackett KA, Simon AF. A comparison of the abuse experiences of male and female adults

molested as children. J ournal of Family Violence 1992;7:5762.

Kendall-Tackett KA, Williams LM, Finkelhor D. Impact of sexual abuse on children: A review and

synthesis of recent empirical studies. Psychological Bulletin 1993;113:164180. [PubMed:

8426874]

Kirk, RE. Experimental design: Procedures for the behavioral sciences. 2. Monterey, CA: Brooks/Cole

Publishing Co; 1982.

Krug RS. Adult male report of childhood sexual abuse by mothers: Case descriptions, motivations, and

long-term consequences. Child Abuse & Neglect 1989;13:111119. [PubMed: 2706553]

Molnar BE, Buka SL, Kessler RC. Child sexual abuse and subsequent psychopathology: Results from

the National Comorbidity Survey. American J ournal of Public Health 2001;91:753760. [PubMed:

11344883]

Moore, S.; Rosenthal, D. Sexuality in adolescence. London: Routeledge; 1993.

Myers MF. Men sexually assaulted as adults and sexually abused as boys. Archives of Sexual

Behavior 1989;18:203215. [PubMed: 2751415]

Pierce R, Pierce LH. The sexually abused child: A comparison of male and female victims. Child

Abuse & Neglect 1985;9:191199. [PubMed: 4005659]

Porter, E. Treating the young male victim of sexual assault: Issues and intervention strategies.

Syracuse, NY: Safer Society Press; 1986.

Putnam FW. Ten-year research update review: Child sexual abuse. J ournal of the American Academy

of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry 2003;42:269278. [PubMed: 12595779]

Raphael KG, Widom CS, Lange G. Childhood victimization and pain in adulthood: A prospective

investigation. Pain 2001;92:283293. [PubMed: 11323150]

Rosenthal R. The file drawer problem and tolerance for null results. Psychological Bulletin

1979;86:638641.

Royston P. Multiple imputation of missing values: Update of ice. Stata J ournal 2005;5:527536.

Royston P. Multiple imputation of missing values. Stata J ournal 2004;4:227241.

StataCorp. Stata statistical software: Release 9. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP; 2005.

Trickett PK, McBride-Chang C. The developmental impact of different forms of child abuse and

neglect. Developmental Review 1995;15:311337.

Valente SM. Sexual abuse of boys. J ournal of Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Nursing 2005;18:10

16. [PubMed: 15701094]

Widom CS, Weiler BL, Cottler LB. Childhood victimization and drug abuse: A comparison of

prospective and retrospective findings. J ournal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology

1999;67:867880. [PubMed: 10596509]

Young RE, Bergandi TA, Titus TG. Comparison of the effects of sexual abuse on male and female

latency-aged children. J ournal of Interpersonal Violence 1994;9:291306.

Maikovich-Fong and J affee Page 12

Child Abuse Negl. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2011 J une 1.

N

I

H

-

P

A

A

u

t

h

o

r

M

a

n

u

s

c

r

i

p

t

N

I

H

-

P

A

A

u

t

h

o

r

M

a

n

u

s

c

r

i

p

t

N

I

H

-

P

A

A

u

t

h

o

r

M

a

n

u

s

c

r

i

p

t

N

I

H

-

P

A

A

u

t

h

o

r

M

a

n

u

s

c

r

i

p

t

N

I

H

-

P

A

A

u

t

h

o

r

M

a

n

u

s

c

r

i

p

t

N

I

H

-

P

A

A

u

t

h

o

r

M

a

n

u

s

c

r

i

p

t

Maikovich-Fong and J affee Page 13

T

a

b

l

e

1

S

e

x

u

a

l

A

b

u

s

e

C

h

a

r

a

c

t

e

r

i

s

t

i

c

s

:

D

e

s

c

r

i

p

t

i

v

e

a

n

d

I

n

f

e

r

e

n

t

i

a

l

S

t

a

t

i

s

t

i

c

s

S

a

m

p

l

e

s

u

b

s

e

t

(

n

)

P

e

r

c

e

n

t

s

u

b

s

t

a

n

t

i

a

t

e

d

(

n

)

P

e

r

c

e

n

t

p

e

n

e

t

r

a

t

i

v

e

(

n

)

P

e

r

c

e

n

t

f

a

m

i

l

i

a

l

p

e

r

p

e

t

r

a

t

o

r

(

n

)

P

e

r

c

e

n

t

e

x

p

e

r

i

e

n

c

i

n

g

m

u

l

t

i

p

l

e

m

a

l

t

r

e

a

t

m

e

n

t

(

n

)

C

h

i

l

d

a

n

d

a

d

o

l

e

s

c

e

n

t

(

4

2

3

)

6

6

.

9

(

2

8

3

)

4

3

.

5

(

1

8

4

)

6

7

.

1

(

2

8

4

)

2

7

.

4

(

1

1

6

)

B

o

y

s

o

n

l

y

(

1

1

7

)

5

0

.

4

(

5

9

)

3

0

.

8

(

3

6

)

6

5

.

8

(

7

7

)

2

3

.

9

(

2

8

)

G

i

r

l

s

o

n

l

y

(

3

0

6

)

7

3

.

2

(

2

2

4

)

4

8

.

4

(

1

4

8

)

6

7

.

6

(

2

0

7

)

2

8

.

8

(

8

8

)

O

R

[

9

5

%

c

o

n

f

i

d

e

n

c

e

i

n

t

e

r

v

a

l

]

1

2

.

4

7

*

*

[

1

.

6

9

,

3

.

6

1

]

2

.

0

5

*

*

[

1

.

3

1

,

3

.

2

0

]

1

.

0

9

[

0

.

6

5

,

1

.

8

2

]

1

.

2

6

[

0

.

8

7

,

1

.

8

5

]

A

d

o

l

e

s

c

e

n

t

(

1

7

6

)

7

3

.

3

(

1

2

9

)

5

0

.

6

(

8

9

)

6

5

.

9

(

1

1

6

)

2

9

.

0

(

5

1

)

B

o

y

s

o

n

l

y

(

3

0

)

6

3

.

3

(

1

9

)

5

3

.

3

(

1

6

)

6

3

.

3

(

1

9

)

3

6

.

7

(

1

1

)

G

i

r

l

s

o

n

l

y

(

1

4

6

)

7

5

.

3

(

1

1

0

)

5

0

.

0

(

7

3

)

6

6

.

4

(

9

7

)

2

7

.

4

(

4

0

)

O

R

[

9

5

%

c

o

n

f

i

d

e

n

c

e

i

n

t

e

r

v

a

l

]

1

2

.

4

5

*

[

1

.

2

2

,

4

.

9

2

]

1

.

0

5

[

0

.

5

0

,

2

.

2

4

]

1

.

3

7

[

0

.

5

5

,

3

.

3

8

]

0

.

7

4

[

0

.

3

7

,

1

.

5

0

]

N

o

t

e

:

P

e

r

c

e

n

t

a

g

e

s

a

r

e

b

a

s

e

d

o

n

n

o

n

-

i

m

p

u

t

e

d

d

a

t

a

;

o

d

d

s

r

a

t

i

o

s

a

r

e

b

a

s

e

d

o

n

i

m

p

u

t

e

d

d

a

t

a

.

1

O

d

d

s

r

a

t

i

o

s

r

e

f

l

e

c

t

t

h

e

o

d

d

s

o

f

e

x

p

e

r

i

e

n

c