Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Cleaning Mic Capsules

Cleaning Mic Capsules

Uploaded by

LordECopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- Places and Landscape in A Changing World - South AmericaDocument11 pagesPlaces and Landscape in A Changing World - South Americajohn diolaNo ratings yet

- NAGRA 4.2: Portable Analogue Audio Tape RecorderDocument26 pagesNAGRA 4.2: Portable Analogue Audio Tape RecordernotaminorthreatNo ratings yet

- Altec-Peerless 4665 Audio Transformer Addendum 10-12Document2 pagesAltec-Peerless 4665 Audio Transformer Addendum 10-12Robert GabrielNo ratings yet

- 2015 Les Paul Deluxe SpecsDocument6 pages2015 Les Paul Deluxe SpecsuiupartNo ratings yet

- Engleza volII - 74 - 97 PDFDocument11 pagesEngleza volII - 74 - 97 PDFAndreea Radulescu33% (3)

- Liquid SO2.1Document13 pagesLiquid SO2.1Musyafa WiryantoNo ratings yet

- 5 Flight Planning 210Document20 pages5 Flight Planning 210Cahangir QanizadeNo ratings yet

- Audible Amplifier Distortion Is Not A Mystery-Baxandall - WW-1977-11Document4 pagesAudible Amplifier Distortion Is Not A Mystery-Baxandall - WW-1977-11attapapaNo ratings yet

- 01-Building A 1929 Style Hartley TransmitterDocument4 pages01-Building A 1929 Style Hartley Transmittermax_orwell100% (1)

- A Biblia Do P.A. - Sonorizacao - The P.A. Bible - em Ingles PDFDocument79 pagesA Biblia Do P.A. - Sonorizacao - The P.A. Bible - em Ingles PDFCarlos Henrique Otoni FerrerNo ratings yet

- Em The Rem inDocument10 pagesEm The Rem injamato75No ratings yet

- Twelve Microphones That Changed HistoryDocument3 pagesTwelve Microphones That Changed HistoryChristopher Full Purpose HaiglerNo ratings yet

- Mutual Coupling Between LoudspeakersDocument40 pagesMutual Coupling Between LoudspeakersDenys FormigaNo ratings yet

- Driving Electrostatic TransducersDocument8 pagesDriving Electrostatic TransducersHữu Thịnh ĐỗNo ratings yet

- Rohde & Schwarz - Loudspeaker Measurements With Audio Analyzers (M. Schlechter)Document41 pagesRohde & Schwarz - Loudspeaker Measurements With Audio Analyzers (M. Schlechter)RafaelCostaNo ratings yet

- Keele (1974-04 AES PublishLow-Frequency Loudspeaker Assessment by Nearfield Sound-Pressure Measuremented) - Nearfield PaperDocument9 pagesKeele (1974-04 AES PublishLow-Frequency Loudspeaker Assessment by Nearfield Sound-Pressure Measuremented) - Nearfield PaperlaserzenNo ratings yet

- Building An AnalogDocument10 pagesBuilding An AnalogRosita AzzamNo ratings yet

- Addition Number Six The Con'-Stant Di-Rec-Tiv'I-Ty White Horn White PaperDocument4 pagesAddition Number Six The Con'-Stant Di-Rec-Tiv'I-Ty White Horn White Paperjosiasns5257No ratings yet

- Valve Types and Characteristics With AppendixDocument30 pagesValve Types and Characteristics With AppendixJoãoAraújoNo ratings yet

- Dummy Head, Micro ArrayDocument193 pagesDummy Head, Micro ArrayMishell Torres100% (1)

- Palmer Cab 112 B ManualDocument116 pagesPalmer Cab 112 B ManualRick BlokzijlNo ratings yet

- Ease 43 HelpDocument706 pagesEase 43 HelpLuigiNo ratings yet

- Choosing A Microphone: Microphone Types and Uses: Dynamic MicrophonesDocument7 pagesChoosing A Microphone: Microphone Types and Uses: Dynamic Microphonesgeraldstar22No ratings yet

- Hiraga Onkens English PDFDocument6 pagesHiraga Onkens English PDFbeepx1No ratings yet

- A Review of Digital Techniques For Modeling Vacuum-Tube Guitar AmplifiersDocument16 pagesA Review of Digital Techniques For Modeling Vacuum-Tube Guitar AmplifiersΔημήτρης ΓκρίντζοςNo ratings yet

- 6C33C-B OTL Amplifier - Background and OTL CircuitsDocument14 pages6C33C-B OTL Amplifier - Background and OTL CircuitsettorreitNo ratings yet

- AKG Brochure 2011Document68 pagesAKG Brochure 2011extiscalinetNo ratings yet

- Mike HarwoodDocument26 pagesMike HarwoodPraveen AndrewNo ratings yet

- Microphone GuideDocument33 pagesMicrophone GuideMarrylyn ArcigaNo ratings yet

- Sample Submissions For Test Bench: ND RDDocument7 pagesSample Submissions For Test Bench: ND RDfb79No ratings yet

- Ampex Recording TheoryDocument121 pagesAmpex Recording TheoryKevin Haworth100% (1)

- Single Metallized Film Pulse Capacitor, Polypropylene Dielectric - According To IEC 60384-16, Grade 1.1Document12 pagesSingle Metallized Film Pulse Capacitor, Polypropylene Dielectric - According To IEC 60384-16, Grade 1.1Hwalam Lee100% (1)

- Capacitor PDFDocument5 pagesCapacitor PDFsathyakalyanNo ratings yet

- Applied Radio Labs: Group Delay Explanations and ApplicationsDocument6 pagesApplied Radio Labs: Group Delay Explanations and Applicationsaozgurluk_scribdNo ratings yet

- RV1Document23 pagesRV1Arasu LoganathanNo ratings yet

- Why Do Audio Transformers Sound Different From Model To Model?Document16 pagesWhy Do Audio Transformers Sound Different From Model To Model?Charles AustinNo ratings yet

- A 40Hz Bass HornDocument2 pagesA 40Hz Bass Hornszolid79No ratings yet

- Basic Capacitor FormulasDocument1 pageBasic Capacitor FormulasvasiliyNo ratings yet

- LOUDSPEAKERDocument29 pagesLOUDSPEAKERMarrylyn ArcigaNo ratings yet

- Understanding Microphone SensitivityDocument3 pagesUnderstanding Microphone SensitivityEric SkinnerNo ratings yet

- Ampeg SVT-GS Gene Simmons Punisher Bass Amp Owner's GuideDocument8 pagesAmpeg SVT-GS Gene Simmons Punisher Bass Amp Owner's GuideAlexandre S. CorrêaNo ratings yet

- Introduction To Vocal Microphones: A Basic Overview of All The Different Types of MicrophonesDocument21 pagesIntroduction To Vocal Microphones: A Basic Overview of All The Different Types of Microphonesdavebass66No ratings yet

- CrossoverDocument15 pagesCrossoverGeorge LunguNo ratings yet

- Pultec HistoryDocument4 pagesPultec HistoryAndresGelvezNo ratings yet

- Mixing With BFDDocument39 pagesMixing With BFDsergioleitNo ratings yet

- Hoffman AB763 2 PDFDocument8 pagesHoffman AB763 2 PDFMa LeiNo ratings yet

- How To Paint Swirl A GuitarsDocument4 pagesHow To Paint Swirl A Guitarstoneskupang100% (1)

- ZombieDocument1 pageZombieJoaquín BasquezNo ratings yet

- Effects Masterclass With Pete CornishDocument10 pagesEffects Masterclass With Pete Cornishshu2uNo ratings yet

- Oct14 PGDistortion BuildGuide Final R2Document33 pagesOct14 PGDistortion BuildGuide Final R2Andrès LandaetaNo ratings yet

- The Arrl Radio Amateur's Handbook - From Its BeginningDocument39 pagesThe Arrl Radio Amateur's Handbook - From Its BeginningMircea PetrescuNo ratings yet

- By Thomas Henry ©2003, 2007 Thomas Henry First Edition Second Printing (Updated, Prepared For PDF Output)Document31 pagesBy Thomas Henry ©2003, 2007 Thomas Henry First Edition Second Printing (Updated, Prepared For PDF Output)CristobalzqNo ratings yet

- Altec Tranny MotionPicJournalDocument13 pagesAltec Tranny MotionPicJournalRobert GabrielNo ratings yet

- Hi-Vi Re Search Loud Speak ErsDocument11 pagesHi-Vi Re Search Loud Speak ErsDomingo AngelNo ratings yet

- Low-Latency Convolution For Real-Time ApplicationDocument7 pagesLow-Latency Convolution For Real-Time ApplicationotringalNo ratings yet

- Beyerdynamic 2006-2007 CatalogDocument60 pagesBeyerdynamic 2006-2007 Catalogbrn80No ratings yet

- PCM81 User Guide Rev2Document173 pagesPCM81 User Guide Rev2fsarkNo ratings yet

- 1959 - 1960 Tape Recorder DirectoryDocument28 pages1959 - 1960 Tape Recorder DirectoryOliver NauckNo ratings yet

- On The Specification of Moving-Coil Drivers For Low Frequency Horn-Loaded Loudspeakers (W. Marshall Leach, JR) PDFDocument10 pagesOn The Specification of Moving-Coil Drivers For Low Frequency Horn-Loaded Loudspeakers (W. Marshall Leach, JR) PDFDaríoNowakNo ratings yet

- The Guitar Amp Handbook: Understanding Tube Amplifiers and Getting Great SoundsFrom EverandThe Guitar Amp Handbook: Understanding Tube Amplifiers and Getting Great SoundsRating: 2 out of 5 stars2/5 (1)

- Audio Bandwidth Extension: Application of Psychoacoustics, Signal Processing and Loudspeaker DesignFrom EverandAudio Bandwidth Extension: Application of Psychoacoustics, Signal Processing and Loudspeaker DesignNo ratings yet

- Disaster Risk Reduction and Management AwarenessDocument38 pagesDisaster Risk Reduction and Management AwarenessMary Jane BuaronNo ratings yet

- Energy Performance Measurement and Indicators: Insert Trainer Names, Location and DateDocument256 pagesEnergy Performance Measurement and Indicators: Insert Trainer Names, Location and DateValentina FlamencoNo ratings yet

- English Chapter 1 A Letter To God Long Anser and Objective Questions AnswerDocument5 pagesEnglish Chapter 1 A Letter To God Long Anser and Objective Questions AnswerREENA SHAKYANo ratings yet

- Evaporation and CondensationDocument3 pagesEvaporation and CondensationHadi AskabanNo ratings yet

- Stonecutters Bridge 2Document10 pagesStonecutters Bridge 2raisa ehsanNo ratings yet

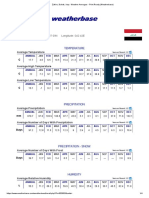

- Zakho, Iraq Travel Weather Averages (Weatherbase)Document4 pagesZakho, Iraq Travel Weather Averages (Weatherbase)gazi shaikhNo ratings yet

- DocumentDocument7 pagesDocumentSyed HusnainNo ratings yet

- Report HydrologyDocument21 pagesReport HydrologyMaryann Requina AnfoxNo ratings yet

- Part B - Religion CPT Rough DraftDocument2 pagesPart B - Religion CPT Rough DraftStealth --No ratings yet

- Cricket ThermometerDocument1 pageCricket ThermometerS. SpencerNo ratings yet

- 08 Chapter 1Document44 pages08 Chapter 1IbrahimNo ratings yet

- Analysis of Adverse Weather For Excusable Delays - ASCE Journal of Construction EngineeringDocument10 pagesAnalysis of Adverse Weather For Excusable Delays - ASCE Journal of Construction EngineeringAdam JonesNo ratings yet

- Madeira - Portugal - (In English)Document72 pagesMadeira - Portugal - (In English)DreamsAvenue.comNo ratings yet

- Ada261900 1Document42 pagesAda261900 1ksshashidharNo ratings yet

- Natural DisastersDocument22 pagesNatural DisastersAnonymous r3wOAfp7j50% (2)

- Chapter 6: How To Do Forecasting by Regression AnalysisDocument7 pagesChapter 6: How To Do Forecasting by Regression AnalysisSarah Sally SarahNo ratings yet

- Student UTC Time CombineDocument139 pagesStudent UTC Time Combinemehran mahjoubNo ratings yet

- Programme: Science, Technology, Research and Innovation DayDocument14 pagesProgramme: Science, Technology, Research and Innovation DayMarian LaurentiuNo ratings yet

- ExperimentDocument48 pagesExperimentmaryamsyuhadaNo ratings yet

- Inline and On Line InstrumentsDocument9 pagesInline and On Line InstrumentsMuhammed Sulfeek100% (2)

- Solution Manual For Essentials of Meteorology An Invitation To The Atmosphere 7th Edition DownloadDocument8 pagesSolution Manual For Essentials of Meteorology An Invitation To The Atmosphere 7th Edition DownloadMrKyleLynchwtjo100% (43)

- Briefing Paper No 2 NRMM Market Update 31 10 17 PDFDocument5 pagesBriefing Paper No 2 NRMM Market Update 31 10 17 PDFAlex WoodrowNo ratings yet

- Quesada Hernandez Et Al 2019 Dynamic Delimination of The Central American Dry CorridorDocument17 pagesQuesada Hernandez Et Al 2019 Dynamic Delimination of The Central American Dry CorridorPascal Girot PignotNo ratings yet

- A Monument To Outlast HumanityDocument28 pagesA Monument To Outlast HumanityadenserffNo ratings yet

- 1079Document3 pages1079Mahmoud MohamedNo ratings yet

- Hot Humid ClimatesDocument47 pagesHot Humid ClimatesAzmi PatarNo ratings yet

Cleaning Mic Capsules

Cleaning Mic Capsules

Uploaded by

LordEOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Cleaning Mic Capsules

Cleaning Mic Capsules

Uploaded by

LordECopyright:

Available Formats

Newsgroups: rec.audio.

pro

Subject: Re: Microphone Cleaning

Date: 22 Oct 1995 20:41:31 GMT

Organization: Josephson Engineering

Lines: 96

Message-ID: <46ea9r$8l9@bug.rahul.net>

References: <0000062F000068CB@nashville.com> <466amg$6sc@news.vcnet.com> <46cqj2

$v0i@inn.aball.de> <DGuuno.187@world.std.com>

NNTP-Posting-Host: foxtrot.rahul.net

NNTP-Posting-User: davidj

It might be the wiser course to let this thread expire, but it

doesn't seem to be doing so. I guess the thing that always gets me

riled is when people say stuff they know, or should know, isn't true.

Now, as in most fine polite circles, these things are said in order

not to offend, and the same is the case here.

>>If microphone diaphragms are so fragile, can't they deteriorate

>>just by aging and normal use?

Microphone diaphragms aren't so fragile(1). The big problem with this

issue is that most people don't know what's inside the microphone,

past the diaphragm, are terrified that they'll damage something, and

as a result get all spooky and do more damage than they otherwise

would. So they get shaky hands and oops, there goes the q-tip through

the diaphragm.

(1) Note, some early Neumann and AKG diaphragms were made of PVC rather

than PET and are subject to embrittlement due to loss of plasticizer

compounds. These diaphragms *are* fragile.

Microphones are cleaned all the time (when, and only when needed) _by

people who know what they are doing_ and can afford to make mistakes.

You have to allow yourself the mindset that if you break it, you can

afford to fix or replace it. Otherwise, leave it alone. The gap between

the diaphragm and the backplate varies from 10 microns to about 50

microns (that's 2/1000 of an inch maximum). Any pressure you put on

the diaphragm with any device like cotton, or a swab, will crash it into

the backplate. Get over it. So will a door slam, or a sharp snare drum

hit. If this causes damage, the diaphragm is already deteriorated to

the point where it can't be depended on for studio service. Make no

assumptions about the diaphragm unless you're able to check them yourself.

There is a lot of junk out there, particularly now that old studio mics

that were once tossed in a pile are worth $5000 and up. I have seen a

lot of mics that sellers claimed were "factory original" that were in

fact rather recently re-made (and the whole gamut from fraudulent junk

to factory-equal-or-better).

The accumulation of spittle and smoke on a large-diaphragm vocal mic

is often at least as heavy as the diaphragm itself. This causes readily

audible changes in response, and never (in my experience) for the better.

That it doesn't make it sound like an entirely different microphone is

proof that diaphragm mass isn't everything (in fact, the main controlling

component is the air cushion behind the diaphragm, but that's a topic

for another rant.) You need to remove this if the mic is going to sound

right. You also need to be sure that all external surfaces that may have

accumulated conductive deposits are clean so that you don't get fizzy

noises whenever the weather is damp. Particularly troublesome in this

regard are the Neumann and other mics that have a conductive spot in

the middle of the diaphragm, with an un-metallized band between it and the

diaphragm support ring. A thin film of spit, atmospheric crud, smoke, etc.

condenses on this ring-shaped band of clear plastic, and it doesn't

take much to bridge the gap. This deposit is often hydrophilic -- when

dry the mic works fine, but when breathed on, the moisture from your

breath combines with the salts in the deposit to form a conductive bridge.

Before you begin, scrub your hands absolutely clean with some harsh,

oil-removing soap. The object of the exercise is to avoid leaving

conductive or hydrophilic (water-attracting) deposits on the insulators.

My solvents of choice are isopropyl alcohol and distilled water. For really

awful cases, xylene is the backup solvent. I use a wooden-handled cotton

swab with an extra layer, about 1/2" thick, of long fiber cotton (rolled

cotton from the drugstore) wound on over the tip. Use a #2 or so sable

artists' watercolor brush, yes, the $20 kind, to remove the dust you can

brush off. Getting the brush a little damp by breathing on it (or better,

putting it in the steam from a tea-kettle so you don't make the deposits

worse) will make more dust stick to it. Almost all remaining deposits can

be removed with just water. Take your time, and keep the cotton damp but

not dripping so you have some control. When you think you have most of

the junk off, STOP. All solvents including the distilled water should be

kept in tightly closed bottles; pour out what you need into a dish and

throw it out when you're done. If the water isn't getting all the crud,

add a little alcohol (this is 91 or 99% isopropyl alcohol, with no other

chemicals in it, preferably lab technical grade at least but USP is good

enough if at least 91%) to the water, about 50% is usually enough. You

use long fiber cotton so you can see all the fibers you left behind, and

remove them before you reassemble the mic. On Neumann and other large

diaphragm mics with the clear band of plastic diaphragm between the

metallized center spot and the support ring, be particularly careful that

this band gets clearn.

Often, you'll see some particle caught between the diaphragm and the

backplate making a sort of "tent." You have to make a decision -- are

you going to tear the whole capsule apart, or send it to a good mic lab,

or buy a new one. Most of the screwed-together mic capsules can be taken

apart and put back together with no special tools except screwdrivers

that really fit the screws, and pin wrenches that fit the threaded rings.

Make a drawing of how it came apart, it has to go back together the same

way. Note however that some of these have the diaphragm tension held

constant only by the pressure of the ring -- no glue (these cannot be

disassembled safely unless you have a means to re-tension the diaphragm).

Measure the capacitances between each terminal and every other

terminal (for instance, a CK12 capsule has two diaphragms and two

backplates, that's four capacitances to measure) and confirm when you

put it back together than you're within a few percent of where you

started.

Modern diaphragms are made of mylar (PET, polyethylene terephthalate)

or PC (polycarbonate) and don't deteriorate much. However the metallization

may or may not be adhered well to the plastic. If you see pieces of it

coming off, or getting thin, STOP. A little missing gold won't hurt,

but if you lose some more it's not a microphone anymore. Metal diaphragm

mics use aluminum, nickel, cobalt alloys, stainless steel or titanium, all

of which can react with junk in the air to form corrosion products, which

are often conductive. If you see pinholes or cracks in the diaphragm, STOP,

use it as is if you can, otherwise get a new one.

Disclaimer and notice: Obviously these are delicate devices easily damaged

by people who don't know what they are doing. I'm not responsible if you

use this information and damage your (or someone else's) microphone. Only

you can make the determination whether you're qualified to attempt such

procedures as I have described here. Also, I don't do microphone repairs or

"upgrades" -- there are several people in the US and Europe who do, you're

on your own in selecting one.

Be patient, pay attention, take your time...

--

Josephson Engineering

You might also like

- Places and Landscape in A Changing World - South AmericaDocument11 pagesPlaces and Landscape in A Changing World - South Americajohn diolaNo ratings yet

- NAGRA 4.2: Portable Analogue Audio Tape RecorderDocument26 pagesNAGRA 4.2: Portable Analogue Audio Tape RecordernotaminorthreatNo ratings yet

- Altec-Peerless 4665 Audio Transformer Addendum 10-12Document2 pagesAltec-Peerless 4665 Audio Transformer Addendum 10-12Robert GabrielNo ratings yet

- 2015 Les Paul Deluxe SpecsDocument6 pages2015 Les Paul Deluxe SpecsuiupartNo ratings yet

- Engleza volII - 74 - 97 PDFDocument11 pagesEngleza volII - 74 - 97 PDFAndreea Radulescu33% (3)

- Liquid SO2.1Document13 pagesLiquid SO2.1Musyafa WiryantoNo ratings yet

- 5 Flight Planning 210Document20 pages5 Flight Planning 210Cahangir QanizadeNo ratings yet

- Audible Amplifier Distortion Is Not A Mystery-Baxandall - WW-1977-11Document4 pagesAudible Amplifier Distortion Is Not A Mystery-Baxandall - WW-1977-11attapapaNo ratings yet

- 01-Building A 1929 Style Hartley TransmitterDocument4 pages01-Building A 1929 Style Hartley Transmittermax_orwell100% (1)

- A Biblia Do P.A. - Sonorizacao - The P.A. Bible - em Ingles PDFDocument79 pagesA Biblia Do P.A. - Sonorizacao - The P.A. Bible - em Ingles PDFCarlos Henrique Otoni FerrerNo ratings yet

- Em The Rem inDocument10 pagesEm The Rem injamato75No ratings yet

- Twelve Microphones That Changed HistoryDocument3 pagesTwelve Microphones That Changed HistoryChristopher Full Purpose HaiglerNo ratings yet

- Mutual Coupling Between LoudspeakersDocument40 pagesMutual Coupling Between LoudspeakersDenys FormigaNo ratings yet

- Driving Electrostatic TransducersDocument8 pagesDriving Electrostatic TransducersHữu Thịnh ĐỗNo ratings yet

- Rohde & Schwarz - Loudspeaker Measurements With Audio Analyzers (M. Schlechter)Document41 pagesRohde & Schwarz - Loudspeaker Measurements With Audio Analyzers (M. Schlechter)RafaelCostaNo ratings yet

- Keele (1974-04 AES PublishLow-Frequency Loudspeaker Assessment by Nearfield Sound-Pressure Measuremented) - Nearfield PaperDocument9 pagesKeele (1974-04 AES PublishLow-Frequency Loudspeaker Assessment by Nearfield Sound-Pressure Measuremented) - Nearfield PaperlaserzenNo ratings yet

- Building An AnalogDocument10 pagesBuilding An AnalogRosita AzzamNo ratings yet

- Addition Number Six The Con'-Stant Di-Rec-Tiv'I-Ty White Horn White PaperDocument4 pagesAddition Number Six The Con'-Stant Di-Rec-Tiv'I-Ty White Horn White Paperjosiasns5257No ratings yet

- Valve Types and Characteristics With AppendixDocument30 pagesValve Types and Characteristics With AppendixJoãoAraújoNo ratings yet

- Dummy Head, Micro ArrayDocument193 pagesDummy Head, Micro ArrayMishell Torres100% (1)

- Palmer Cab 112 B ManualDocument116 pagesPalmer Cab 112 B ManualRick BlokzijlNo ratings yet

- Ease 43 HelpDocument706 pagesEase 43 HelpLuigiNo ratings yet

- Choosing A Microphone: Microphone Types and Uses: Dynamic MicrophonesDocument7 pagesChoosing A Microphone: Microphone Types and Uses: Dynamic Microphonesgeraldstar22No ratings yet

- Hiraga Onkens English PDFDocument6 pagesHiraga Onkens English PDFbeepx1No ratings yet

- A Review of Digital Techniques For Modeling Vacuum-Tube Guitar AmplifiersDocument16 pagesA Review of Digital Techniques For Modeling Vacuum-Tube Guitar AmplifiersΔημήτρης ΓκρίντζοςNo ratings yet

- 6C33C-B OTL Amplifier - Background and OTL CircuitsDocument14 pages6C33C-B OTL Amplifier - Background and OTL CircuitsettorreitNo ratings yet

- AKG Brochure 2011Document68 pagesAKG Brochure 2011extiscalinetNo ratings yet

- Mike HarwoodDocument26 pagesMike HarwoodPraveen AndrewNo ratings yet

- Microphone GuideDocument33 pagesMicrophone GuideMarrylyn ArcigaNo ratings yet

- Sample Submissions For Test Bench: ND RDDocument7 pagesSample Submissions For Test Bench: ND RDfb79No ratings yet

- Ampex Recording TheoryDocument121 pagesAmpex Recording TheoryKevin Haworth100% (1)

- Single Metallized Film Pulse Capacitor, Polypropylene Dielectric - According To IEC 60384-16, Grade 1.1Document12 pagesSingle Metallized Film Pulse Capacitor, Polypropylene Dielectric - According To IEC 60384-16, Grade 1.1Hwalam Lee100% (1)

- Capacitor PDFDocument5 pagesCapacitor PDFsathyakalyanNo ratings yet

- Applied Radio Labs: Group Delay Explanations and ApplicationsDocument6 pagesApplied Radio Labs: Group Delay Explanations and Applicationsaozgurluk_scribdNo ratings yet

- RV1Document23 pagesRV1Arasu LoganathanNo ratings yet

- Why Do Audio Transformers Sound Different From Model To Model?Document16 pagesWhy Do Audio Transformers Sound Different From Model To Model?Charles AustinNo ratings yet

- A 40Hz Bass HornDocument2 pagesA 40Hz Bass Hornszolid79No ratings yet

- Basic Capacitor FormulasDocument1 pageBasic Capacitor FormulasvasiliyNo ratings yet

- LOUDSPEAKERDocument29 pagesLOUDSPEAKERMarrylyn ArcigaNo ratings yet

- Understanding Microphone SensitivityDocument3 pagesUnderstanding Microphone SensitivityEric SkinnerNo ratings yet

- Ampeg SVT-GS Gene Simmons Punisher Bass Amp Owner's GuideDocument8 pagesAmpeg SVT-GS Gene Simmons Punisher Bass Amp Owner's GuideAlexandre S. CorrêaNo ratings yet

- Introduction To Vocal Microphones: A Basic Overview of All The Different Types of MicrophonesDocument21 pagesIntroduction To Vocal Microphones: A Basic Overview of All The Different Types of Microphonesdavebass66No ratings yet

- CrossoverDocument15 pagesCrossoverGeorge LunguNo ratings yet

- Pultec HistoryDocument4 pagesPultec HistoryAndresGelvezNo ratings yet

- Mixing With BFDDocument39 pagesMixing With BFDsergioleitNo ratings yet

- Hoffman AB763 2 PDFDocument8 pagesHoffman AB763 2 PDFMa LeiNo ratings yet

- How To Paint Swirl A GuitarsDocument4 pagesHow To Paint Swirl A Guitarstoneskupang100% (1)

- ZombieDocument1 pageZombieJoaquín BasquezNo ratings yet

- Effects Masterclass With Pete CornishDocument10 pagesEffects Masterclass With Pete Cornishshu2uNo ratings yet

- Oct14 PGDistortion BuildGuide Final R2Document33 pagesOct14 PGDistortion BuildGuide Final R2Andrès LandaetaNo ratings yet

- The Arrl Radio Amateur's Handbook - From Its BeginningDocument39 pagesThe Arrl Radio Amateur's Handbook - From Its BeginningMircea PetrescuNo ratings yet

- By Thomas Henry ©2003, 2007 Thomas Henry First Edition Second Printing (Updated, Prepared For PDF Output)Document31 pagesBy Thomas Henry ©2003, 2007 Thomas Henry First Edition Second Printing (Updated, Prepared For PDF Output)CristobalzqNo ratings yet

- Altec Tranny MotionPicJournalDocument13 pagesAltec Tranny MotionPicJournalRobert GabrielNo ratings yet

- Hi-Vi Re Search Loud Speak ErsDocument11 pagesHi-Vi Re Search Loud Speak ErsDomingo AngelNo ratings yet

- Low-Latency Convolution For Real-Time ApplicationDocument7 pagesLow-Latency Convolution For Real-Time ApplicationotringalNo ratings yet

- Beyerdynamic 2006-2007 CatalogDocument60 pagesBeyerdynamic 2006-2007 Catalogbrn80No ratings yet

- PCM81 User Guide Rev2Document173 pagesPCM81 User Guide Rev2fsarkNo ratings yet

- 1959 - 1960 Tape Recorder DirectoryDocument28 pages1959 - 1960 Tape Recorder DirectoryOliver NauckNo ratings yet

- On The Specification of Moving-Coil Drivers For Low Frequency Horn-Loaded Loudspeakers (W. Marshall Leach, JR) PDFDocument10 pagesOn The Specification of Moving-Coil Drivers For Low Frequency Horn-Loaded Loudspeakers (W. Marshall Leach, JR) PDFDaríoNowakNo ratings yet

- The Guitar Amp Handbook: Understanding Tube Amplifiers and Getting Great SoundsFrom EverandThe Guitar Amp Handbook: Understanding Tube Amplifiers and Getting Great SoundsRating: 2 out of 5 stars2/5 (1)

- Audio Bandwidth Extension: Application of Psychoacoustics, Signal Processing and Loudspeaker DesignFrom EverandAudio Bandwidth Extension: Application of Psychoacoustics, Signal Processing and Loudspeaker DesignNo ratings yet

- Disaster Risk Reduction and Management AwarenessDocument38 pagesDisaster Risk Reduction and Management AwarenessMary Jane BuaronNo ratings yet

- Energy Performance Measurement and Indicators: Insert Trainer Names, Location and DateDocument256 pagesEnergy Performance Measurement and Indicators: Insert Trainer Names, Location and DateValentina FlamencoNo ratings yet

- English Chapter 1 A Letter To God Long Anser and Objective Questions AnswerDocument5 pagesEnglish Chapter 1 A Letter To God Long Anser and Objective Questions AnswerREENA SHAKYANo ratings yet

- Evaporation and CondensationDocument3 pagesEvaporation and CondensationHadi AskabanNo ratings yet

- Stonecutters Bridge 2Document10 pagesStonecutters Bridge 2raisa ehsanNo ratings yet

- Zakho, Iraq Travel Weather Averages (Weatherbase)Document4 pagesZakho, Iraq Travel Weather Averages (Weatherbase)gazi shaikhNo ratings yet

- DocumentDocument7 pagesDocumentSyed HusnainNo ratings yet

- Report HydrologyDocument21 pagesReport HydrologyMaryann Requina AnfoxNo ratings yet

- Part B - Religion CPT Rough DraftDocument2 pagesPart B - Religion CPT Rough DraftStealth --No ratings yet

- Cricket ThermometerDocument1 pageCricket ThermometerS. SpencerNo ratings yet

- 08 Chapter 1Document44 pages08 Chapter 1IbrahimNo ratings yet

- Analysis of Adverse Weather For Excusable Delays - ASCE Journal of Construction EngineeringDocument10 pagesAnalysis of Adverse Weather For Excusable Delays - ASCE Journal of Construction EngineeringAdam JonesNo ratings yet

- Madeira - Portugal - (In English)Document72 pagesMadeira - Portugal - (In English)DreamsAvenue.comNo ratings yet

- Ada261900 1Document42 pagesAda261900 1ksshashidharNo ratings yet

- Natural DisastersDocument22 pagesNatural DisastersAnonymous r3wOAfp7j50% (2)

- Chapter 6: How To Do Forecasting by Regression AnalysisDocument7 pagesChapter 6: How To Do Forecasting by Regression AnalysisSarah Sally SarahNo ratings yet

- Student UTC Time CombineDocument139 pagesStudent UTC Time Combinemehran mahjoubNo ratings yet

- Programme: Science, Technology, Research and Innovation DayDocument14 pagesProgramme: Science, Technology, Research and Innovation DayMarian LaurentiuNo ratings yet

- ExperimentDocument48 pagesExperimentmaryamsyuhadaNo ratings yet

- Inline and On Line InstrumentsDocument9 pagesInline and On Line InstrumentsMuhammed Sulfeek100% (2)

- Solution Manual For Essentials of Meteorology An Invitation To The Atmosphere 7th Edition DownloadDocument8 pagesSolution Manual For Essentials of Meteorology An Invitation To The Atmosphere 7th Edition DownloadMrKyleLynchwtjo100% (43)

- Briefing Paper No 2 NRMM Market Update 31 10 17 PDFDocument5 pagesBriefing Paper No 2 NRMM Market Update 31 10 17 PDFAlex WoodrowNo ratings yet

- Quesada Hernandez Et Al 2019 Dynamic Delimination of The Central American Dry CorridorDocument17 pagesQuesada Hernandez Et Al 2019 Dynamic Delimination of The Central American Dry CorridorPascal Girot PignotNo ratings yet

- A Monument To Outlast HumanityDocument28 pagesA Monument To Outlast HumanityadenserffNo ratings yet

- 1079Document3 pages1079Mahmoud MohamedNo ratings yet

- Hot Humid ClimatesDocument47 pagesHot Humid ClimatesAzmi PatarNo ratings yet