Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Generativna Sintaksa

Generativna Sintaksa

Uploaded by

meri_actually2230Original Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Generativna Sintaksa

Generativna Sintaksa

Uploaded by

meri_actually2230Copyright:

Available Formats

LECTURETTE #1

LABELS

The framework we're going to be discussing before any others, the one

above all others without knowledge of which it is impossible to do any

responsible work in syntactic theory nowadays, suffers from a high degree

of terminological infelicity in that there is no short lable for it that

is completely and unambiguously acceptable to everybody. I've listed in

(1) a number of labels that have been used by various people, at various

times. All of these are objectionable on some grounds or other.

(1) 'the framework that is associated with Noam Chomsky and his

students (in that Department of Linguistics and Philosophy)

at MIT'

Standard Theory

Government & Binding (GB)

Revised, Extended Standard Theory (REST)

The Principles & Parameters Approach (P&P or PPA)

Minimality/Minimalist Program (MP)

We might try to shorten the first label while retaining its essential

content by calling it 'Chomskyan theory', but this is not often done and

would convey an inaccurate impression. Unlike 'Newtonian theory' of

gravitation, 'Einsteinian theory' of relativity, and 'Darwinian theory'

of evolution, this framework of syntactic theory did not burst full-blown

like Athena from the brain of a single, eponymous scientist, in this case

Noam Chomsky. In many respects, the development of the framework has

more in common with quantum theory, being the result of fruitful interac-

tion between a variety of researchers often at odds with each other. In

fact, less than most other frameworks on the market is this one tied to a

single individual or small group of individuals. While Chomsky's has

without doubt been the hand that has guided and molded it through its

various developments and whose judgment must sooner or later be passed on

any new development, the research in this programme is free-wheeling and

there is frequent disagreement amongst the various proponents, including

Chomsky himself. Furthermore, unlike many other frameworks there is no

one authoritative text setting forth the tenets of the theory and there-

fore it is much harder to define what constitutes orthodoxy within this

school and what lies beyond the pale.

I'm saying all this now because you will frequently hear, from me and

from others, statements about this particular framework which, taken at

face value, would imply that its proponents constitute not just a clique

but a cabal, a nomenklatura, an exclusianist circle of initiates, aco-

lytes, and mystagogues who subscribe to the theory as though it were one

of the more recondite mystery religions of Imperial times. While there

may be some sociological truth to such insinuations, they distort the

essential scientific nature of the theory itself.

So what *is* this framework commonly called? One label is 'Standard

Theory'. This label is resented by a lot of people because it implies

that the 'standard' in syntactic theory is defined by Chomsky and his

students and that everything that deviates from that 'standard' is ipso

facto, well, deviant. This attitude is unfortunately reinforced by the

above-mentioned exclusianistic behaviour of many 'Standard Theoreti-

cians', who often talk as though the 'Standard Theory' were the only

generative theory of syntax available. (The van Riemsdijk & Williams

text i mentioned in my 'Welcome!' posting has been taken to task by at

least one reviewer for calling itself an 'introduction to *the* theory of

grammar' when it's actually an introduction to specifically the framework

we're discussing here.) The extent to which theoretical assumptions pe-

culiar to a given framework are taken for granted by the proponents

thereof is an important research interest of mine, and while the 'Stan-

dard Theoreticians' are no less immune from this tendency than others

neither are they any more so.

Properly speaking, the label 'Standard Theory' refers to the entire histo-

rical edifice of syntactic theory built by Chomsky and his students over

several decades and, rather like many an old mansion, includes several

sections which, having been added on at different times, are of start-

lingly different fundamental design. Essentially, the framework began

around the mid-50's. The definitive presentation of this earlier stage

is Chomsky's 1965 book Aspects of the Theory of Syntax, and often the

phrase 'Standard Theory' is used in a strict sense to refer specifically

to the theory presented there, also called the 'Aspects model'.

Over the next 15 years or so, the framework went through massive revision

and reconsideration, to the point that its fundamental character changed

substantially; we will be discussing some of these changes later. By the

early 80's a framework of syntactic theory had been developed which,

while clearly descended from the Aspects model in its general outline and

fundamental assumptions, was different enough to require a completely new

presentation and a distinctive label. It is primarily this framework

that we will be discussing here.

In 1980 Chomsky delivered a series of lectures at Pisa which were pu-

blished the subsequent year under the title 'Lectures on Government and

Binding'. These lectures essentially presented the new framework for the

first time in an organized, relatively coherent form. As a result, the

title of the book was very swiftly given to the framework, which conse-

quently is referred to by many as 'Government & Binding' or 'GB'. This

is unfortunate. The Pisa Lectures, and the book that came out of them,

are aptly titled because in them, although he outlines the whole frame-

work, Chomsky concentrates on two particular sections of the theory,

namely those aspects dealing with 'government', i.e. the relationship

between a syntactic head (e.g., a verb or preposition) and its depen-

dents, and 'binding', i.e. the relationship between a pronoun or anaphor

and its antecedent. But as i shall be explaining later the framework as

a whole involves roughly a half-dozen such 'sub-theories', and it is not

the case that 'Government' and 'Binding' are in any sense the two most

important of them; they're merely the ones Chomsky had the most to say

about in 1980. I have myself on at least one occasion heard Chomsky

express regret that the label 'Government & Binding' has been taken for

the entire framework, and his preference for the label 'Revised, Extended

Standard Theory', often abbreviated 'REST'. Partly because of Chomsky's

thus-stated preference and partly because i agree with his rationale for

it (which we shall to some extent get to later), this is one of the la-

bels i tend to prefer. It offends primarily by its maintenance of the

adjective 'standard' in defining what is merely one sect, as it were, or

school of thought in syntactic theory. Perhaps if we could just agree to

understand that word 'standard' in this context rather as we do in the

names of corporate bodies such as 'Standard Oil of Ohio' all this excess

terminology would be unnecessary.

('Why do we have "Standard Theory" and "Revised Extended Standard Theory"

but no "Extended Standard Theory"?' you may well ask. The label 'Exten-

ded Standard Theory' (abbreviated 'EST', naturally) was used for a while

during the '70's to describe a particular stage in the evolution of the

framework. Andrew Radford's 1980 textbook Syntactic Theory specifically

refers to it by this label. So it's worth knowing about; but it's not

much used nowadays.)

During the second half of the 80's another label developed among many of

the framework's proponents. That label is 'the Principles & Parameters

Approach', typically abbreviated (when abbreviated at all) 'P&P' or 'PPA'.

My upcoming outline of the framework's theoretical assumptions will make

the appropriateness of this label clear; but it still offends some, who

complain, 'Are rival frameworks ipso facto unprincipled? Don't other

frameworks make use of parameters?' These complaints are legitimate, but,

as you will see, the paired notions of 'principles and parameters' are

central to the framework under discussion in ways that they perhaps are

not in others. Partly for this reason, i have accepted the label 'PPA'

as also a valid label for this framework.

As a result of works published by Luigi Rizzi and by Chomsky in the early

1990's, a new label has recently begun being used by some proponents of

this framework: 'Minimality' or 'the Minimalist Program' (MP). I consider

this a rather unfortunate term, since many competing frameworks of syntac-

tic theory can be called 'minimalist' in different ways. I therefore tend

to avoid the label 'Minimality' in favour of the labels 'REST' and 'PPA'.

(Some of you will have heard the adjective 'Lexicalist' and may be wondering

where it fits in with all this. The 'Lexicalist Hypothesis', to oversim-

plify somewhat, is the claim that a certain amount of what is usually re-

garded as 'syntax' is actually done in the lexicon, logically 'preceding'

the application of any strictly syntactic rules, transformations, what

have you. Suffice it to say that ALL versions of Chomskyan theory since

the early '70's assume some version of it, as do an increasing number of

competing frameworks. Indeed, REST has been getting increasingly 'lexi-

calist' in recent years.)

Be it noted that none of these labels are to be construed as precisely

synonymous with each other; every one of them refers, in at least some

contexts, to slightly different versions of the framework and, as we

shall see, the differences can be cumulative and therefore ultimately

quite significant. On the other hand, the boundaries or, if i may be

permitted the pun, 'barriers' between the stages defined by the various

labels are quite fuzzy. Thus, while there are some definite differences

of approach between late-80's style PPA and early-90's style Minimality,

Alec Marantz, in a recent paper on the 'Minimality Program', refers to it

as 'this latest version of Chomsky's Principles and Parameters approach',

clearly implying that at least in his mind Minimality is basically just a

revision of PPA.

But one needs to be aware of all these different labels, because some pro-

ponents of the framework under discussion feel very strongly about one

label or another. I have had the experience of being myself surrounded by

people who are accustomed to calling it 'GB' and having a reviewer complain

of my passing use of that label, 'NOBODY calls it that anymore!', and on the

other hand of having a reviewer complain of my usage of the abbreviation

'PPA' on the grounds that hann had never before encountered it. I'm afraid

it is occasionally useful, at the beginning of a paper, to give all the

labels with which people might be familiar, assert their mutual (approxi-

mate) equivalence, and then explicitly pick one and use it consistently

throughout the rest of the paper.

So much for what the damn thing is called. In my next posting, we will

start getting down to what it claims and how it works.

Best,

Steven

---------------------

Dr. Steven Schaufele

712 West Washington

Urbana, IL 61801

217-344-8240

fcosws@prairienet.org

**** O syntagmata linguarum liberemini humanarum! ***

*** Nihil vestris privari nisi obicibus potestis! ***

You might also like

- Chinese Tonic Herbs PDFDocument160 pagesChinese Tonic Herbs PDFbernteoNo ratings yet

- Concepts and Cognitive Science - MargolisDocument79 pagesConcepts and Cognitive Science - MargolisTim HardwickNo ratings yet

- Bett The Sophists and RelativismDocument32 pagesBett The Sophists and RelativismOscar Leandro González RuizNo ratings yet

- 012 - Abraham Solomonick - Towards A Comprehensive Theory of Lexicographic DefinitionsDocument8 pages012 - Abraham Solomonick - Towards A Comprehensive Theory of Lexicographic Definitionsmha2000No ratings yet

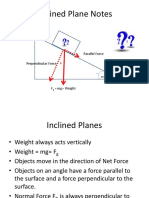

- Inclined Planes and Forces Notes PDFDocument19 pagesInclined Planes and Forces Notes PDFJohnLesterLaurelNo ratings yet

- GATE Data Structure & Algorithm BookDocument12 pagesGATE Data Structure & Algorithm BookMims12No ratings yet

- The End of TheoristsDocument24 pagesThe End of TheoristsHarumi FuentesNo ratings yet

- Jameson 2004Document6 pagesJameson 2004GiwrgosKalogirouNo ratings yet

- Rules and Representations: Chomsky and Representational RealismDocument20 pagesRules and Representations: Chomsky and Representational RealismsupardiNo ratings yet

- The University of Chicago PressDocument7 pagesThe University of Chicago Presscottchen6605No ratings yet

- Thompson - O - Doherty (2009) PDFDocument25 pagesThompson - O - Doherty (2009) PDFHannah MirandaNo ratings yet

- IR Theory Problem Solving Theory Versus Critical TheoryDocument3 pagesIR Theory Problem Solving Theory Versus Critical Theoryalexander warheroNo ratings yet

- Guerring. Ideology A Definitional AnalysisDocument38 pagesGuerring. Ideology A Definitional AnalysisJuliana MorosinoNo ratings yet

- Picallo What Principles and Parameters Got WrongDocument18 pagesPicallo What Principles and Parameters Got WrongKatharina FunkNo ratings yet

- Chomsky PhilDocument14 pagesChomsky PhilBujinlkham SurenjavNo ratings yet

- Contradiction and DialecticDocument7 pagesContradiction and DialecticRodolfo Ferronatto De SouzaNo ratings yet

- On Paradigms, Theories and Models: Problemas Del Desarrollo January 2002Document12 pagesOn Paradigms, Theories and Models: Problemas Del Desarrollo January 2002Alejandro VanegasNo ratings yet

- Aximus Logical Ontology An IntroductionDocument17 pagesAximus Logical Ontology An IntroductionDavidNo ratings yet

- Klima, G. - Contemporary Essentialism and Aristotelian EssentialismDocument18 pagesKlima, G. - Contemporary Essentialism and Aristotelian EssentialismestebanistaNo ratings yet

- Feser - Classical Natural Law Theory Property Rights and TaxationDocument32 pagesFeser - Classical Natural Law Theory Property Rights and TaxationCharles Walter100% (1)

- Putnam - Models and RealityDocument20 pagesPutnam - Models and RealityIsabelWangNo ratings yet

- Metaphor and The Main Problem o - Paul RicoeurDocument17 pagesMetaphor and The Main Problem o - Paul RicoeurMarcelaNo ratings yet

- Stokhof - Wittgenstein & Formal SemanticsDocument21 pagesStokhof - Wittgenstein & Formal SemanticsJWoNo ratings yet

- The Use and Abuse of Speech-Act Theory in CriticismDocument28 pagesThe Use and Abuse of Speech-Act Theory in CriticismEsteban JijónNo ratings yet

- Logical Remarks On The Semantic Approach PDFDocument34 pagesLogical Remarks On The Semantic Approach PDFFelipe SantosNo ratings yet

- Count-Mass Distinction Across LanguagesDocument95 pagesCount-Mass Distinction Across LanguagesHenrique dos SantosNo ratings yet

- Feyerabend 1961Document6 pagesFeyerabend 1961GUSTAVO MARINO VILLAR MAYUNTUPANo ratings yet

- What Theory Is Not, Theorizing IsDocument7 pagesWhat Theory Is Not, Theorizing IsAmna MushtaqNo ratings yet

- An Introduction To Metatheories, Theories, and ModelsDocument19 pagesAn Introduction To Metatheories, Theories, and ModelsMarija HorvatNo ratings yet

- Lutz-2015 Syntax - Semantics - DebateDocument30 pagesLutz-2015 Syntax - Semantics - Debategerman guerreroNo ratings yet

- A New Characterization of Scientific TheoriesDocument16 pagesA New Characterization of Scientific TheorieslimuviNo ratings yet

- MPAT 5 1 87 144 PDFDocument58 pagesMPAT 5 1 87 144 PDFÁngel Martínez OrtegaNo ratings yet

- The Relationist and Substantivalist Theories of Time: Foes or Friends?Document16 pagesThe Relationist and Substantivalist Theories of Time: Foes or Friends?Mattie le MooseNo ratings yet

- Dialectic and DialethicDocument29 pagesDialectic and Dialethicjamesmacmillan100% (1)

- What Scientific Theories Could Not BeDocument27 pagesWhat Scientific Theories Could Not BeMhmmd AbdNo ratings yet

- Substance and Category in Aristotle (First MS Draft)Document98 pagesSubstance and Category in Aristotle (First MS Draft)Ronald KlinglerNo ratings yet

- Reference and Science SHORTDocument10 pagesReference and Science SHORTgerman guerreroNo ratings yet

- Theoreticalsociology AconciseintroductiontotwelvesociologicaltheoriesDocument77 pagesTheoreticalsociology AconciseintroductiontotwelvesociologicaltheoriesKyle B. LañaNo ratings yet

- Jslat 150 AyounDocument11 pagesJslat 150 AyounEbinabo EriakumaNo ratings yet

- Brandom Dynamics PlainDocument26 pagesBrandom Dynamics PlainbtimNo ratings yet

- The Shell and The Quernell - Nicolas AbrahamDocument15 pagesThe Shell and The Quernell - Nicolas AbrahamEric romeroNo ratings yet

- End of Ir Theory Final-5!6!2013Document30 pagesEnd of Ir Theory Final-5!6!2013Callie TompkinsNo ratings yet

- Gallie - 1939 - An Interpretation of Causal LawsDocument19 pagesGallie - 1939 - An Interpretation of Causal LawsTullio ViolaNo ratings yet

- Analytic and Continental Philosophy (Explaining The Differences)Document21 pagesAnalytic and Continental Philosophy (Explaining The Differences)m_ziaie_mNo ratings yet

- Lingtheo Chomskyanturn NotesDocument15 pagesLingtheo Chomskyanturn NotesRami IbrahimNo ratings yet

- Phrasemes in Language and Phraseology in LinguisticsDocument64 pagesPhrasemes in Language and Phraseology in Linguisticsjason_cullen100% (1)

- The Concept of Equivalence in TranslatioDocument19 pagesThe Concept of Equivalence in TranslatioBrillante MoonlightNo ratings yet

- Carnap Logical Foundations of ProbabilityDocument365 pagesCarnap Logical Foundations of ProbabilityEduardoNo ratings yet

- Carnap Logical Foundations of ProbabilityDocument365 pagesCarnap Logical Foundations of ProbabilityJavier Benavides100% (2)

- 1996 Midgley What Is This Thing Called CSTDocument15 pages1996 Midgley What Is This Thing Called CSTRizan MohamedNo ratings yet

- Revolutionary New Ideas Appear InfrequentlyDocument18 pagesRevolutionary New Ideas Appear Infrequentlyberwick_537752457No ratings yet

- Theories of Imperialism - Kemp, Tom - 1967 - London, Dobson - Anna's ArchiveDocument220 pagesTheories of Imperialism - Kemp, Tom - 1967 - London, Dobson - Anna's ArchivenicasiusNo ratings yet

- Cf. E.g., Seibt 1990, 1996a, B, C, D, 2005. On This See in Particular Seibt 2004a, B and 2008Document31 pagesCf. E.g., Seibt 1990, 1996a, B, C, D, 2005. On This See in Particular Seibt 2004a, B and 2008Hermano CallouNo ratings yet

- Sage Publications, Inc. Johnson Graduate School of Management, Cornell UniversityDocument15 pagesSage Publications, Inc. Johnson Graduate School of Management, Cornell Universityjake bowersNo ratings yet

- From Text Grammar To Critical Discourse Analysis PDFDocument46 pagesFrom Text Grammar To Critical Discourse Analysis PDFMaría Laura RamosNo ratings yet

- Compounds in English, in French, in Polish, and in GeneralDocument18 pagesCompounds in English, in French, in Polish, and in GeneralYozamy TrianaNo ratings yet

- Big Answer BookDocument208 pagesBig Answer BookAli Breland100% (1)

- BAKER - Thematic Roles and Syntactic StructureDocument66 pagesBAKER - Thematic Roles and Syntactic StructureRerisson Cavalcante100% (1)

- Critical Constitutionalism NowDocument19 pagesCritical Constitutionalism NowBella_Electra1972No ratings yet

- TSYS01R90 System Overview D9.0 Mod 4 Single Zone System Functionality and Subsystems PG v.01Document113 pagesTSYS01R90 System Overview D9.0 Mod 4 Single Zone System Functionality and Subsystems PG v.01Mutara Edmond NtareNo ratings yet

- Assignment Brief Unit 47 QCFDocument14 pagesAssignment Brief Unit 47 QCFAlamzeb KhanNo ratings yet

- Diagnosis and Management of The Epilepsies in Adults and Children: Summary of Updated NICE GuidanceDocument8 pagesDiagnosis and Management of The Epilepsies in Adults and Children: Summary of Updated NICE GuidanceANDREWNo ratings yet

- Examen de Ingles Quinto GradoDocument2 pagesExamen de Ingles Quinto GradoTyson Ferreyra100% (2)

- PA 644 - M2 LecturesDocument412 pagesPA 644 - M2 LectureskatNo ratings yet

- 5.wonderful World of Endodontic Working Width The Forgotten Dimension - A ReviewDocument7 pages5.wonderful World of Endodontic Working Width The Forgotten Dimension - A ReviewSiva Kumar100% (1)

- RMRS Construction Equipment MODU FOP EngDocument416 pagesRMRS Construction Equipment MODU FOP EngDesedentNo ratings yet

- Treating Stalking A Practical Guide For Clinicians Troy Mcewan All ChapterDocument67 pagesTreating Stalking A Practical Guide For Clinicians Troy Mcewan All Chapterfelipe.canada376100% (6)

- FCE Unit 3 TestDocument4 pagesFCE Unit 3 Testconny100% (1)

- TKD Amended ComplaintDocument214 pagesTKD Amended ComplaintHouston ChronicleNo ratings yet

- Fresh Foods Ordering ProcessDocument5 pagesFresh Foods Ordering ProcessSagarPatelNo ratings yet

- Strategic Management (Case Study) PDFDocument5 pagesStrategic Management (Case Study) PDFDineshNo ratings yet

- "House or A Flat" Limba Engleza Prezentare Clasa 7Document10 pages"House or A Flat" Limba Engleza Prezentare Clasa 7Gidei NichitaNo ratings yet

- Lecture 02Document19 pagesLecture 02Zan DaoNo ratings yet

- BM Wed Wild LordDocument2 pagesBM Wed Wild Lordcori sabauNo ratings yet

- Coop Learning ActivitiesDocument198 pagesCoop Learning ActivitiesJanine Mosca GonzalesNo ratings yet

- A Practical Guide To Analyzing Nucleic Acid Concentration and Purity With Microvolume SpectrophotometersDocument8 pagesA Practical Guide To Analyzing Nucleic Acid Concentration and Purity With Microvolume SpectrophotometersJerry Llanos AlarcónNo ratings yet

- CMSS 2110-3: Industrial Acceleration Sensor With Integral 5 Meter (16.5 Feet) Rugged Stainless Steel Braided CableDocument2 pagesCMSS 2110-3: Industrial Acceleration Sensor With Integral 5 Meter (16.5 Feet) Rugged Stainless Steel Braided CableJonathan LujanNo ratings yet

- Internal Control Self AssessmentDocument14 pagesInternal Control Self Assessmentbeverkei100% (2)

- 32 Gallent v. GallentDocument2 pages32 Gallent v. GallentWendy PeñafielNo ratings yet

- Merry Christmas Multiple Activities Reading Comprehension Exercises - 102970Document2 pagesMerry Christmas Multiple Activities Reading Comprehension Exercises - 102970adaNo ratings yet

- Model Paper Financial ManagementDocument6 pagesModel Paper Financial ManagementSandumin JayasingheNo ratings yet

- Aurangzeb Alamgir Emperor of Mughal IndiaDocument4 pagesAurangzeb Alamgir Emperor of Mughal IndiaRazaNo ratings yet

- Control Optimization of Oil Production Under Geological UncertaintyDocument23 pagesControl Optimization of Oil Production Under Geological UncertaintyAnonymous yjLUF9gDTSNo ratings yet

- Adverbs of Tense With The Present PerfectDocument8 pagesAdverbs of Tense With The Present PerfectdiegoNo ratings yet

- Christmas VacationDocument8 pagesChristmas VacationNatália SzabóNo ratings yet

- DLL Mapeh-5 Q3 W7Document9 pagesDLL Mapeh-5 Q3 W7Diana Rose AcupeadoNo ratings yet