Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Labor - Prelim - CBTC Employees Union Vs Clave

Labor - Prelim - CBTC Employees Union Vs Clave

Uploaded by

katchmeifyoucannotOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Labor - Prelim - CBTC Employees Union Vs Clave

Labor - Prelim - CBTC Employees Union Vs Clave

Uploaded by

katchmeifyoucannotCopyright:

Available Formats

Today is Saturday, November 09, 2013

Search

Republic of the Philippines

SUPREME COURT

Manila

FIRST DIVISION

G.R. No. L-49582 January 7, 1986

CBTC EMPLOYEES UNION, petitioner,

vs.

THE HONORABLE JACOBO C. CLAVE, Presidential Executive Assistant, and COMMERCIAL BANK &

TRUST COMPANY OF THE PHILIPPINES, respondents.

Francisco F. Angeles for petitioner.

Pacis, Reyes, De Leon & Cruz Law, Office for respondent CBTC.

Edmundo R. AbigaN, Jr. for respondent Union.

DE LA FUENTE, J.:

Petition for certiorari seeking to annul and set aside the decision of the respondent Presidential Executive Assistant

1

affirming that of the Acting Secretary of Labor who reversed the decision of the National Labor Relations Comission which

upheld the Voluntary Arbitrator's order directing the private respondent bank to pay its monthly paid employees their "legal

holiday pay."

Petitioner Commercial Bank and Trust Company Employees' Union (Union for short) lodged a complaint with the

Regional Office No. IV, Department of Labor, against private respondent bank (Comtrust) for non-payment of the

holiday pay benefits provided for under Article 95 of the Labor Code in relation to Rule X, Book III of the Rules and

Regulations Implementing the Labor Code.

Failing to arrive at an amicable settlement at conciliation level, the parties opted to submit their dispute for voluntary

arbitration. The issue presented was: "Whether the permanent employees of the Bank within the collective

bargaining unit paid on a monthly basis are entitled to holiday pay effective November 1, 1974, pursuant to Article

95 (now Article 94) of the Labor Code, as amended and Rule X (now Rule IV), Book III of the Rules and

Regulations Implementing the Labor Code. "

In addition, the disputants signed a Submission Agreement stipulating as final, unappealable and executory the decision of

the Arbitrator, including subsequent issuances for clarificatory and/or relief purposes, notwithstanding Article 262 of the

Labor Code which allow appeal in certain instances.

2

In the course of the hearing, the Arbitrator apprised the parties of an interpretative bulletin on "holiday pay" about to be

issued by the Department of Labor. Whereupon, the Union filed a Manifestation

3

which insofar as relevant stated:

6. That complainant union . . . has manifested its apprehension on the contents of the said

Interpretative Bulletin in view of a well-nigh irresistible move on the part of the employers to exclude

permanent workers similarly situated as the employees of Comtrust from the coverage of the holiday

pay benefit despite the express and self-explanatory provisions of the law, its implementing rules and

opinions thereon . . . .

7. That in the event that said Interpretative Bulletin regarding holiday pay would be adverse to the

present claim . . . in that it would in effect exclude the said employees from enjoyment of said benefit,

whether wholly or partially, complainant union respectfully reserves the right to take such action as

may be appropriate to protect its interests, a question of law being involved. . . . An Interpretative

Bulletin which was inexistent at the time the said commitment was made and which may be contrary to

the law itself should not bar the right of the union to claim for its holiday pay benefits.

On April 22, 1976, the Arbitrator handed down an award on the dispute. Relevant portions thereof read as follows:

The uncontroverted facts of this case are as follows:

(1) That the complainant Union is the recognized sole and exclusive collective bargaining

representative of all the permanent rank-and-file employees of the Bank with an existing Collective

Bargaining Agreement covering the period from July 1, 1974 up to June 30, 1977;

l a w p h i l

(2) That ... the standard workweek of the Bank generally consists of five (5) days of eight (8) hours

each day which, . . . said five days are generally from Monday thru Friday; and, as a rule, Saturdays,

Sundays and the regular holidays are not considered part of the standard workweek.

(3) That, in computing the equivalent daily rate of its employees covered by the CBA who are paid on

a monthly basis, the following computation is used, as per the provisions of Section 4, Article VII, of the

CBA (Annex "A"):

Daily Rate = Basic Monthly Salary plus CLA x 12 250

Basic Hourly Rate = Daily Rate 8

(4) That the divisor of '250', . . . was arrived at by subtracting the 52 Sundays, 52 Saturdays, the 10

regular holidays and December 31 (secured thru bargaining), or a total of 115 off-days from the 365

days of the year or a difference of 250 days.

Considering the above uncontroverted facts, the principal question to be resolved is whether or not

the monthly pay of the covered employees already includes what Article 94 of the Labor Code

requires as regular holiday pay benefit in the amount of his regular daily wage (100% if unworked or

200% if worked) during the regular holidays enumerated therein, i.e., Article 94(c) of the Labor Code.

In its latest Memorandum, filed on March 26, 1976, the Bank relies heavily on the

provisions of Section 2, Rule IV, Book 111, of the Rules and Regulations implementing

particularly Article 94 (formerly Article 208) of the Labor Code, which Section reads as

follows:

SECTION 2. Status of employees paid by the month -Employees who are uniformly paid by the month,

irrespective of the number of' working days therein with a salary of not less than the statutory or

established minimum wage, shall be presumed to be paid for all days in the month whether worked or

not.

For this purpose, the monthly minimum wage shall not be less than the statutory minimum wage

multiplied by 365 days divided by twelve. (Emphasis supplied).

While admitting that there has virtually been no change effected by Presidential Decree No. 850, which

amended the Labor Code, other than the re-numbering of the original Article 208 of said Code to what

is now Article 94, the Bank, however, attaches a great deal of significance in the above-quoted Rule

as to render the question at issue 'moot and academic'.

On the other hand, the Union maintains, in its own latest Memorandum, filed also on March 26, 1976,

that the legal presumption established in the above-quoted Rule is merely a disputable presumption.

This contention of the Union is now supported by a pronouncement categorically to that effect by no

less than the National Labor Relations Commission (NLRC) in the case of The Chartered Bank

Employees Association vs. The Chartered Bank. NLRC Case No. (s) RB-IV-1739-75 (RO4-5-3028-

75), which reads, in part, as follows:

. . . A disputable presumption was sea in that it would be presumed the salary of monthly-

paid employees may already include rest days, such as Saturdays, Sundays, special

and legal holidays, worked or unworked, in effect connoting that evidence to the contrary

may destroy such a supposed legal presumption. Indeed, the Rule merely sets a

presumption. It does not conclusively presume that the salary of monthly-paid employees

already includes unworked holidays. . . .

The practice of the Bank of paying its employees a sum equivalent to Base pay plus

Premium on Saturdays, Sundays and special and legal holidays, destroys the legal

presumption that monthly pay is for an days of the month. For if the monthly pay is

payment for all days of the month, then why should the employee be paid again for

working on such rest days. (Emphasis supplied)

There is no reason at present not to adopt the above ruling of the Honorable Comission, especially

considering the fact that this Arbitrator, in asking a query on the nature of the presumption established

by the above Rule, from the Director of Labor Standards in the PMAP Conference held at the Makati

Hotel on March 13, 1976, was given the categorical answer that said presumption is merely

disputable. This answer from the Labor Standards Director is significant inasmuch as it is his office,

the Bureau of Labor Standards, that is reportedly instrumental in the preparation of the implementing

Rules, particularly on Book III of the Labor Code on Conditions of Employment, to which group the

present Rule under discussion belongs.

So, rather than rendering moot and academic the issue at hand, as suggested by the Bank, the more

logical step to take is to determine whether or not there is sufficient evidence to overcome the

disputable presumption established by the Rule.

It is unquestioned, and as provided for in the CBA itself, that the divisor used in determining the daily

rate of the monthly-paid employees is '250'.

xxx xxx xxx

Against this backdrop, certain relevant and logical conclusions result, namely:

( A) The Bank maintains that, since its inception or start of operations in 1954, all monthly-paid

employees in the Bank are paid their monthly salaries without any deduction for unworked Saturdays,

Sundays, legals and special holidays. On the other hand, it also maitains that, as a matter of fact,

'always conscious of its employee who has to work, on respondent's rest days of Saturdays and

Sundays or on a legal holiday, an employee who works overtime on any of said days is paid one

addition regular pay for the day plus 50% of said regular pay (Bank's Memorandum, page 3, filed

January 21, 1976). . . .

xxx xxx xxx

On the other hand, there is more reason to believe that, if the Bank has never made any deduction

from its monthly-paid employees for unworked Saturdays, Sundays, legal and special holidays, it is

because there is really nothing to deduct properly since the monthly, salary never really included pay

for such unworked days-and which give credence to the conclusion that the divisor '250' is the proper

one to use in computing the equivalent daily rate of the monthly-paid employees.

(B) The Bank further maintains that the holiday pay is intended only for daily-paid workers. In this

regard, the NLRC has this to say , in the same above-quoted Chartered Bank case:

It is contended that holiday pay is primarily for daily wage earners. Let us examine the

law, more specifically Article 95 (now Article 94) of the Labor Code to see whether it

supports this contention. The words used in the Decree are 'every worker', while the

framers of the Implementing Rules preferred the use of the phrase 'all employees.' Both

the decree itself and the Rules mentioned enumerated the excepted workers. It is a basic

rule of statutory construction that putting an exception limits or modifies the enumeration

or meaning made in the law. it is thus easy to see that a mere reading of the Decree and

of the Rules would show that the monthly-paid employees of the Bank are not expressly

included in the enumeration of the exception.

Special notice is made of the fact that the criteria at once readable from the exception

referred to is the nature of the job and the number of employees involved, and not

whether the employee is a daily-wage earner or a regular monthly-paid employee.

There is no reason at all to digress from the above-quoted observation of the Honorable Commission

for purposes of the present case.

xxx xxx xxx

Finally, inasmuch as Article 94 of the Labor Code is one of its so-called self-executing provisions,

conjointly with its corresponding implementing Rules, it is to be taken to have taken effect, as of

November 1, 1974, as per Section I (1), Rule IV, Book III , of the Implementing Rules.

WHEREAS, all the above premises considered, this Arbitrator rules that:

(1) All the monthly-paid employees of the Bank herein represented by the Union and as governed by

their Collective Bargaining Agreement, are entitled to the holiday pay benefits as provided for in Article

94 of the labor Code and as implemented by Rule IV, Book III, of the corresponding implementing

Rules, except for any day or any longer period designated by lawor holding a general election or

referendum;

(2) Paragraph (1) hereof means that any covered employee who does not work on any of the regular

holidays enumerated in Article 94 (c) of the Labor Code, except that which is designated for election or

referendum purposes, is still entitled to receive an amount equivalent to his regular daily wage in

addition to his monthly salary. If he work on any of the regular holidays, other than that which is

designated for election or referendum purposes, he is entitled to twice, his regular daily wage in

addition to his monthly salary. The 50% premium pay provided for in the CBA for working on a rest

day (which has been interpreted by the parties to include the holidays) shall be deemed already

included in the 200% he receives for working on a regular holiday. With respect to the day or any

longer period designated by law for holding a general election or referendum, if the employee does

not work on such day or period he shall no longer be entitled to receive any additional amount other

than his monthly salary which is deemed to include already his regular daily wage for such day or

period. If he works on such day or period, he shall be entitled to an amount equivalent to his regular

daily wage (100%) for that day or period in addition to his monthly salary. The 50% premium pay

provided for in the CBA for working on that day or period shall be deemed already included in the

additional 100% he receives for working on such day or period; and

(3) The Bank is hereby ordered to pay all the above employees in accordance with the above

paragraphs (1) and (2), retroactive from November 1, 1974.

SO ORDERED.

April 22, 1976, Manila, Philippines.

4

The next day, on April 23, 1976, the Department of Labor released Policy Instructions No. 9, hereinbelow quoted:

The Rules implementing PD 850 have clarified the policy in the implementation of the ten (10) paid

legal holidays. Before PD 850, the number of working days a year in a firm was considered important

in determining entitlement to the benefit. Thus, where an employee was working for at least 313 days,

he was considered definitely already paid. If he was working for less than 313, there was no certainty

whether the ten (10) paid legal holidays were already paid to him or not.

The ten (10) paid legal holidays law, to start with, is intended to benefit principally daily employees. In

the case of monthly, only those whose monthly salary did not yet include payment for the ten (10) paid

legal holidays are entitled to the benefit.

Under the rules implementing PD 850, this policy has been fully clarified to eliminate controversies on

the entitlement of monthly paid employees. The new determining rule is this: If the monthly paid

employee is receiving not less than P 240, the maximum monthly minimum wage, and his monthly pay

is uniform from January to December, he is presumed to be already paid the ten (10) paid legal

holidays. However, if deductions are made from his monthly salary on account of holidays in months

where they occur, then he is still entitled to the ten (10) paid legal holidays.

These new interpretations must be uniformly and consistently upheld.

This issuance shall take effect immediately.

After receipt of a copy of the award, private respondent filed a motion for reconsideration, followed by a

supplement thereto. Said motion for reconsideration was denied. A copy of the order of denial was received by

private respondent on July 8, 1976.

Said private respondent interposed an appeal to the National Labor Relations Commission (NLRC), contending that

the Arbitrator demonstrated gross incompetence and/or grave abuse of discretion when he entirely premised the

award on the Chartered Bank case and failed to apply Policy Instructions No. 9. This appeal was dismissed on

August 16, 1976, by the NLRC because it was filed way beyond the ten-day period for perfecting an appeal and

because it contravened the agreement that the award shall be final and unappealable.

Private respondent then appealed to the Secretary of Labor. On June 30, 1977, the Acting Secretary of Labor reversed the

NLRC decision and ruled that the appeal was filed on time and that a review of the case was inevitable as the money

claim exceeded P100,000.00.

5

Regarding the timeliness of the appeal, it was pointed out that the labor Department had

on several occasions treated a motion for reconsideration (here, filed before the Arbitrator) as an appeal to the proper

appellate body in consonance with the spirit of the Labor Code to afford the parties a just, expeditious and inexpensive

disposition of their claims, liberated from the strict technical rules obtaining in the ordinary courts.

Anent the issue whether or not the agreement barred the appeal, it was noted that the Manifestation, supra, "is not of slight

significance because it has in fact abrogated complainant's commitment to abide with the decision of the Voluntary

Arbitrator without any reservation" and amounted to a "virtual repudiation of the agreement vesting finality"

6

on the

arbitrator's disposition.

And on the principal issue of holiday pay, the Acting Secretary, guided by Policy Instructions No. 9, applied the

same retrospectively, among other things.

In due time, the Union appealed to the Office of the President. In affirming the assailed decision, Presidential

Executive Assistant Jacobo C. Clave relied heavily on the Manifestation and Policy Instructions No. 9.

Hence, this petition.

On January 10, 1981, petitioner filed a motion to substitute the Bank of the Philippine Islands as private

respondent, as a consequence of the Articles of Merger executed by said bank and Commercial Bank & Trust Co.

which inter alia designated the former as the surviving corporate entity. Said motion was granted by the Court.

We find the petitioner impressed with merit.

In excluding the union members of herein petitioner from the benefits of the holiday pay law, public respondent

predicated his ruling on Section 2, Rule IV, Book III of the Rules to implement Article 94 of the labor Code

promulgated by the then Secretary of labor and Policy Instructions No. 9.

In Insular Bank of Asia and America Employees' Union (IBAAEU) vs. Inciong,

7

this Court's Second Division, speaking

through former Justice Makasiar, expressed the view and declared that the aforementioned section and interpretative

bulletin are null and void, having been promulgated by the then Secretary of Labor in excess of his rule-making authority. It

was pointed out, inter alia, that in the guise of clarifying the provisions on holiday pay, said rule and policy instructions in

effect amended the law by enlarging the scope of the exclusions. We further stated that the then Secretary of Labor went as

far as to categorically state that the benefit is principally intended for daily paid employees whereas the law clearly states

that every worker shall be paid their regular holiday pay-which is incompatible with the mandatory directive, in Article 4 of

the Labor Code, that "all doubts in the implementation and interpretation of the provisions of Labor Code, including its

implementing rules and regulations, shall be resolved in favor of labor." Thus, there was no basis at all to deprive the union

members of their right to holiday pay.

In the more recent case of The Chartered Bank Employees Association vs. Hon. Ople,

8

this Court in an en banc decision

had the occasion to reiterate the above-stated pronouncement. We added:

The questioned Section 2, Rule IV, Book III of the Integrated Rules and the Secretary's Policy

Instruction No. 9 add another excluded group, namely, 'employees who are uniformly paid by the

month'. While the additional exclusion is only in the form of a presumption that all monthly paid

employees have already been paid holiday pay, it constitutes a taking away or a deprivation which

must be in the law if it is to be valid. An administrative interpretation which diminishes the benefits of

labor more than what the statute delimits or withholds is obviously ultra vires.

In view of the foregoing, the challenged decision of public respondent has no leg to stand on as it was premised

principally on the same Section 2, Rule IV, Book III of the Implementing Rules and Policy Instructions No. 9. This

being the decisive issue to be resolved, We find no necessity to pass upon the other issues raised, such as the

effects of the Union's Manifestation and the propriety of applying Policy Instructions No. 9 retroactively to the instant

case.

WHEREFORE, the questioned decisions of the respondent Presidential Executive Assistant and the Acting

Secretary of labor are hereby set aside, and the award of the Arbitrator reinstated. Costs against the private

respondent.

IT IS SO ORDERED.

Teehankee (Chairman), Plana, Relova, Gutierrez, Jr., and Patajo, JJ., concur.

Melencio-Herrera, J., took no part.

Footnotes

1 dated Dec. 8, 1978, Annex "J" , pp. 73-78, Rollo.

2 However, voluntary arbitration awards or decisions on money claims involving an amount exceeding

P100,000 or forty percent (40%) of the paid-up capital of the respondent employer, whichever is

lower, may be appealed to the National Labor Relations Commission on any of the following grounds:

(a) Abuse of discretion; and (b) Gross incompetence.

3 pp. 50-51, Rollo.

4 pp. 53-61, Rollo.

5 the Socio-Economic Analyst of the Department having reported that the money, value of the holiday

pay amounted to P432,122.88.

6 p. 69, Rollo.

7 G.R. No. 52415, 132 SCRA 663.

8 G.R. No. L-44717, August 28, 1985.

The Lawphi l Proj ect - Arel l ano Law Foundati on

You might also like

- Cereals Business PlanDocument39 pagesCereals Business Plancarol92% (49)

- ISO 13485 Quality Manual SampleDocument5 pagesISO 13485 Quality Manual SampleNader Shdeed33% (6)

- DLBBAB01 - E Sample SolutionDocument5 pagesDLBBAB01 - E Sample SolutionИван ДобродомовNo ratings yet

- Notes On Stiglitz Economics of The Public Sector Chapters 4 8Document20 pagesNotes On Stiglitz Economics of The Public Sector Chapters 4 8Abdullah Shad100% (1)

- Insurance Practice TestDocument12 pagesInsurance Practice TestkatchmeifyoucannotNo ratings yet

- Bar Exams Credit Transactions Questions (2011-2012)Document2 pagesBar Exams Credit Transactions Questions (2011-2012)katchmeifyoucannot100% (4)

- ProMed (Apr 09)Document8 pagesProMed (Apr 09)GANESHNo ratings yet

- Philippine Pineapple Industry PDFDocument10 pagesPhilippine Pineapple Industry PDFJojit Balod50% (2)

- CBTC Employees Union vs. Clave (G.R. No. L-49582 January 7, 1986) - 8Document9 pagesCBTC Employees Union vs. Clave (G.R. No. L-49582 January 7, 1986) - 8Amir Nazri KaibingNo ratings yet

- CBTC Employees Vs ClaveDocument8 pagesCBTC Employees Vs ClaveJacquelyn AlegriaNo ratings yet

- Labor HW 2Document51 pagesLabor HW 2Hyuga NejiNo ratings yet

- 22.1 CBTC Employees Union V ClaveDocument5 pages22.1 CBTC Employees Union V ClaveluigimanzanaresNo ratings yet

- CBTC V ClaveDocument8 pagesCBTC V ClaveInna De LeonNo ratings yet

- CBTC Employees Union V ClaveDocument2 pagesCBTC Employees Union V ClaveFayda Cariaga50% (2)

- Petitioner vs. vs. Respondents: en BancDocument6 pagesPetitioner vs. vs. Respondents: en BancCharmaine GraceNo ratings yet

- Chartered Bank V OpleDocument6 pagesChartered Bank V OplePeace Marie Panangin100% (1)

- 20 Chartered Bank Employees Asso V Ople GR L 44717 082885Document3 pages20 Chartered Bank Employees Asso V Ople GR L 44717 082885Winfred TanNo ratings yet

- 16 Ibaa Employees vs. InciongDocument13 pages16 Ibaa Employees vs. InciongrafNo ratings yet

- CBCT Employees Union vs. ClaveDocument3 pagesCBCT Employees Union vs. ClaveAderose SalazarNo ratings yet

- Insular Bank of Asia and American Express Union V InciongDocument9 pagesInsular Bank of Asia and American Express Union V InciongKimwel De VillaNo ratings yet

- Chartered Bank EmployeesDocument7 pagesChartered Bank EmployeesAnne Camille SongNo ratings yet

- Insular Bank v. InciongDocument3 pagesInsular Bank v. InciongKei ShaNo ratings yet

- Insular Bank of Asia vs. InciongDocument11 pagesInsular Bank of Asia vs. InciongChristiane Marie BajadaNo ratings yet

- Chartered Bank vs. OpleDocument2 pagesChartered Bank vs. OplebebejhoNo ratings yet

- IBAA Vs InciongDocument9 pagesIBAA Vs InciongaionzetaNo ratings yet

- Ibaaeu vs. InciongDocument8 pagesIbaaeu vs. InciongKaiNo ratings yet

- CBTC Employees Union vs. Clave, GR No. L-49582, Jan. 7, 1986Document1 pageCBTC Employees Union vs. Clave, GR No. L-49582, Jan. 7, 1986Vincent Quiña PigaNo ratings yet

- Case Digest OceanicDocument5 pagesCase Digest OceanicnicakyutNo ratings yet

- CASESDocument342 pagesCASESrafNo ratings yet

- 015-Insular Bank of Asia and America Employees Union (IBAAEU) v. Inciong, G.R. No. L-52415, October 14, 1994)Document10 pages015-Insular Bank of Asia and America Employees Union (IBAAEU) v. Inciong, G.R. No. L-52415, October 14, 1994)Jopan SJNo ratings yet

- IBAAEU v. InciongDocument17 pagesIBAAEU v. InciongCharlie ThesecondNo ratings yet

- Labor CasesDocument85 pagesLabor CasesajapanganibanNo ratings yet

- Edited Shell Phil Vs Central Bank and Ibaaeu Vs InciongDocument4 pagesEdited Shell Phil Vs Central Bank and Ibaaeu Vs InciongJun MontanezNo ratings yet

- Case 13 Chartered Bank Employees Association V Ople GR No. L-44717 August 28, 1985Document4 pagesCase 13 Chartered Bank Employees Association V Ople GR No. L-44717 August 28, 1985raikha barraNo ratings yet

- IBAAEU vs. Inciong - Holiday Pay - Role of The Judiciary - Resolve Conflict in Statutory ConstructionDocument3 pagesIBAAEU vs. Inciong - Holiday Pay - Role of The Judiciary - Resolve Conflict in Statutory ConstructionJona Carmeli CalibusoNo ratings yet

- INSULAR BANK OF ASIA v. AMADO G. INCIONGDocument13 pagesINSULAR BANK OF ASIA v. AMADO G. INCIONGkhate alonzoNo ratings yet

- 4.3 Chartered Bank Employees Assoc. Vs OpleDocument2 pages4.3 Chartered Bank Employees Assoc. Vs OpleHiroshi AdrianoNo ratings yet

- Apojsf Jablg PordDocument4 pagesApojsf Jablg PorddonjujoyaNo ratings yet

- Producers Bank Vs NLRCDocument5 pagesProducers Bank Vs NLRCRobert QuiambaoNo ratings yet

- IBAA V InciongDocument15 pagesIBAA V InciongKrisha BodiosNo ratings yet

- Chartered Bank Employees Association vs. OpleDocument3 pagesChartered Bank Employees Association vs. Oplemichelle zatarainNo ratings yet

- Mantrade FMMC Division Employees and Workers Union v. Bacungan (1986)Document3 pagesMantrade FMMC Division Employees and Workers Union v. Bacungan (1986)Zan BillonesNo ratings yet

- Xxii. Union of Filipro Emoloyees V Vivar G.R. No. 79255 January 20, 1992Document12 pagesXxii. Union of Filipro Emoloyees V Vivar G.R. No. 79255 January 20, 1992Kirsten Rose ConconNo ratings yet

- Petitioner vs. vs. Respondents Jose C. Espinas Siguion Reyna, Montecillo & OngsiakoDocument9 pagesPetitioner vs. vs. Respondents Jose C. Espinas Siguion Reyna, Montecillo & OngsiakoChristine Joy PamaNo ratings yet

- Producers Bank of The Philippines v. NLRC G.R. No. 100701Document9 pagesProducers Bank of The Philippines v. NLRC G.R. No. 100701Charlotte GalineaNo ratings yet

- CBTC Employees Union Vs ClaveDocument1 pageCBTC Employees Union Vs ClaveAnonymous eyrtJpledWNo ratings yet

- Manggagawa NG PRCDocument5 pagesManggagawa NG PRCHib Atty TalaNo ratings yet

- Globe Mackay v. NLRCDocument4 pagesGlobe Mackay v. NLRCLyceum LawlibraryNo ratings yet

- Chartered Bank Employees Association VDocument1 pageChartered Bank Employees Association VmfspongebobNo ratings yet

- Mantrade DigestDocument63 pagesMantrade DigestNelson Javier Panggoy Jr.No ratings yet

- Mantrade - FMMC V BacunganDocument2 pagesMantrade - FMMC V BacunganAllen Windel Bernabe100% (1)

- Globe Mackay Cable and Radio Corporation, Et Al. v. NLRC, Et Al., G.R. No. 74156, June 29, 1988Document5 pagesGlobe Mackay Cable and Radio Corporation, Et Al. v. NLRC, Et Al., G.R. No. 74156, June 29, 1988Martin SNo ratings yet

- 08 Insular Bank of Asia and America Employee's Union V Incion (Enriquez)Document4 pages08 Insular Bank of Asia and America Employee's Union V Incion (Enriquez)Mikhel BeltranNo ratings yet

- Central Azucarera V Central Azucarera de Tarlac Labor Union FulltextDocument2 pagesCentral Azucarera V Central Azucarera de Tarlac Labor Union FulltextinvictusincNo ratings yet

- Case DIGESTs LABOR LAWDocument2 pagesCase DIGESTs LABOR LAWraymond gwapoNo ratings yet

- Castillo, Laman, Tan & Pantaleon For Petitioners. Edwin D. Dellaban For Private RespondentsDocument16 pagesCastillo, Laman, Tan & Pantaleon For Petitioners. Edwin D. Dellaban For Private RespondentsAnne Sherly OdevilasNo ratings yet

- 31 Insular Bank of Asia and America Employees Union v. InciongDocument2 pages31 Insular Bank of Asia and America Employees Union v. InciongGabrielle Adine Santos100% (1)

- Labor-Digest - Self Study 3Document11 pagesLabor-Digest - Self Study 3Gerald RoxasNo ratings yet

- 5.6.a Producers Bank of The Philippines VS NLRCDocument2 pages5.6.a Producers Bank of The Philippines VS NLRCRochelle Othin Odsinada Marqueses100% (2)

- 34) Chartered Bank Employees' Association v. OpleDocument3 pages34) Chartered Bank Employees' Association v. OpleCarla June GarciaNo ratings yet

- Petitioner, V. Arbitrator Froilan M. Bacungan and MantradeDocument5 pagesPetitioner, V. Arbitrator Froilan M. Bacungan and MantradeBetson CajayonNo ratings yet

- Labor Congress of The Philippines vs. NLRC, 1998Document3 pagesLabor Congress of The Philippines vs. NLRC, 1998Xavier BataanNo ratings yet

- Labor Cases AsfsdfDocument7 pagesLabor Cases AsfsdfVictor LimNo ratings yet

- IBAA Employees Union v. InciongDocument12 pagesIBAA Employees Union v. InciongEfren Allen M. ValenciaNo ratings yet

- Producer's Bank Vs NLRCDocument7 pagesProducer's Bank Vs NLRCNiñanne BalbuenaNo ratings yet

- Songco VS NLRC DigestDocument3 pagesSongco VS NLRC Digestangelica poNo ratings yet

- THE LABOUR LAW IN UGANDA: [A TeeParkots Inc Publishers Product]From EverandTHE LABOUR LAW IN UGANDA: [A TeeParkots Inc Publishers Product]No ratings yet

- Labor Contract Law of the People's Republic of China (2007)From EverandLabor Contract Law of the People's Republic of China (2007)No ratings yet

- Sugar Benefits - Health Benefits of SugarDocument11 pagesSugar Benefits - Health Benefits of SugarkatchmeifyoucannotNo ratings yet

- Sugar Benefits - Health Benefits of SugarDocument11 pagesSugar Benefits - Health Benefits of SugarkatchmeifyoucannotNo ratings yet

- LaborDocument5 pagesLaborkatchmeifyoucannotNo ratings yet

- Insurance Commission Circulars 2013Document8 pagesInsurance Commission Circulars 2013katchmeifyoucannotNo ratings yet

- Corporation CodeDocument26 pagesCorporation CodekatchmeifyoucannotNo ratings yet

- Crim Cases 1-10Document23 pagesCrim Cases 1-10katchmeifyoucannotNo ratings yet

- Coffee Can Improve Energy Levels and Make You Smarter: 1 2 Stimulant Called Caffeine 3Document9 pagesCoffee Can Improve Energy Levels and Make You Smarter: 1 2 Stimulant Called Caffeine 3katchmeifyoucannotNo ratings yet

- NLRC Rules of Procedure 2011Document19 pagesNLRC Rules of Procedure 2011katchmeifyoucannotNo ratings yet

- Guillaume Apollinaire 2012 6 PDFDocument53 pagesGuillaume Apollinaire 2012 6 PDFkatchmeifyoucannotNo ratings yet

- Persons and Family RelationsDocument40 pagesPersons and Family RelationsMiGay Tan-Pelaez96% (23)

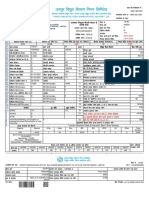

- Certificate of Creditable Tax Withheld at Source: Marcos Hi-Way Sitio Kaybagsik Bgy. San Luis Antipolo CityDocument1 pageCertificate of Creditable Tax Withheld at Source: Marcos Hi-Way Sitio Kaybagsik Bgy. San Luis Antipolo CitykatchmeifyoucannotNo ratings yet

- Abella Vs NLRC PDFDocument3 pagesAbella Vs NLRC PDFkatchmeifyoucannotNo ratings yet

- Admin-Antipolo Vs Nha DigestDocument3 pagesAdmin-Antipolo Vs Nha DigestkatchmeifyoucannotNo ratings yet

- 2005 Bar Exams Questions in Mercantile LawDocument5 pages2005 Bar Exams Questions in Mercantile LawkatchmeifyoucannotNo ratings yet

- BCS BI 2 NegotiableInstrumentsTestAnswerKeyDocument2 pagesBCS BI 2 NegotiableInstrumentsTestAnswerKeykatchmeifyoucannotNo ratings yet

- 04 MMDA V GarinDocument10 pages04 MMDA V GarinkatchmeifyoucannotNo ratings yet

- 2005 Bar Exams Questions in Mercantile LawDocument5 pages2005 Bar Exams Questions in Mercantile LawkatchmeifyoucannotNo ratings yet

- Transpo PDFDocument25 pagesTranspo PDFkatchmeifyoucannotNo ratings yet

- Be It Enacted by The Senate and House of Representatives of The Philippines in Congress AssembledDocument12 pagesBe It Enacted by The Senate and House of Representatives of The Philippines in Congress AssembledkatchmeifyoucannotNo ratings yet

- Rules of Procedure in Election Contests Before The Courts Involving Elective Municipal and Barangay OfficialsDocument19 pagesRules of Procedure in Election Contests Before The Courts Involving Elective Municipal and Barangay OfficialskatchmeifyoucannotNo ratings yet

- Attestation Letter ExampleDocument4 pagesAttestation Letter ExampleInnocent ChideraNo ratings yet

- Cranes & ComponentsDocument13 pagesCranes & ComponentsdenyNo ratings yet

- BCom Master - Routine - Sem - 2 - 4 - 6 2023Document2 pagesBCom Master - Routine - Sem - 2 - 4 - 6 2023Soumodip ParuiNo ratings yet

- Scope and Limitation - Printing SystemDocument1 pageScope and Limitation - Printing SystemIvan Bendiola100% (3)

- Market Place Is Often Efficient, But Not Necessarily EquitableDocument9 pagesMarket Place Is Often Efficient, But Not Necessarily EquitableMonica MonicaNo ratings yet

- Full Time MBA Brochure - Melbourne Business SchoolDocument19 pagesFull Time MBA Brochure - Melbourne Business Schoolvishnupremnair02No ratings yet

- 3 Audit ReportDocument50 pages3 Audit ReportCristel TannaganNo ratings yet

- 5 Chha 18Document1 page5 Chha 18Vikas TanwaniNo ratings yet

- Calculating GDP-Practice Problems 19-20Document3 pagesCalculating GDP-Practice Problems 19-20Jill C100% (1)

- SOAS - Welcome To Mars Colony PDFDocument10 pagesSOAS - Welcome To Mars Colony PDFFabrício CarvalhoNo ratings yet

- Nigeria COVID 19 Action Recovery and Economic Stimulus Program ProjectDocument169 pagesNigeria COVID 19 Action Recovery and Economic Stimulus Program ProjectOribuyaku DamiNo ratings yet

- Ramprabhu M: No:14/8 1 Street, Annaisathya Nagar, Nesapakkam, Chennai - 600078 Phone: 091-7200189388Document4 pagesRamprabhu M: No:14/8 1 Street, Annaisathya Nagar, Nesapakkam, Chennai - 600078 Phone: 091-7200189388RAMPRABHU MANOHARANNo ratings yet

- Master's Thesis Beyond The Ovop Through Design Thinking ApproachDocument176 pagesMaster's Thesis Beyond The Ovop Through Design Thinking ApproachDinar SafaNo ratings yet

- Pamantasan NG Lungsod NG Maynila - Freshmen AdmissionDocument2 pagesPamantasan NG Lungsod NG Maynila - Freshmen AdmissionHonnie Julianne DiscalsoNo ratings yet

- 3850 - Mathematics - Stage - 3 - Question - Paper - Sample 3Document19 pages3850 - Mathematics - Stage - 3 - Question - Paper - Sample 3ShellyNo ratings yet

- Polytechnic Univesity of The PhilippinesDocument18 pagesPolytechnic Univesity of The PhilippinesJewel AmponinNo ratings yet

- Kirana KingDocument5 pagesKirana KingWITN NEWSNo ratings yet

- No842 Licences For MiningDocument2 pagesNo842 Licences For MiningimmanuelvinothNo ratings yet

- Bank-Name HeadquartersDocument2 pagesBank-Name HeadquartersKaran RajbhojNo ratings yet

- 10065CBSE Guess Paper 2022-23Document8 pages10065CBSE Guess Paper 2022-23Dhriti KarnaniNo ratings yet

- Petition For Appointment of ArbitratorDocument6 pagesPetition For Appointment of ArbitratorRaksha RajeshNo ratings yet

- Communication in Professional Life (English)Document4 pagesCommunication in Professional Life (English)Sandesh MavliyaNo ratings yet

- From The Details Given Below Prepare Cash Flow StatementDocument5 pagesFrom The Details Given Below Prepare Cash Flow StatementOmkar AdaskarNo ratings yet

- WS On Business Finance Needs and SourcesDocument2 pagesWS On Business Finance Needs and SourcesRomaan JawwadNo ratings yet

![THE LABOUR LAW IN UGANDA: [A TeeParkots Inc Publishers Product]](https://imgv2-2-f.scribdassets.com/img/word_document/702714789/149x198/ac277f344e/1706724197?v=1)