Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Old Norse Ship Names and Ship Terms by Rudolf Simek

Old Norse Ship Names and Ship Terms by Rudolf Simek

Uploaded by

Christine Leigh Ward-WielandCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- Lake TownDocument35 pagesLake TownSadisticSeraph100% (4)

- Into The Wolfs MawDocument63 pagesInto The Wolfs MawAndrew Stansfield75% (4)

- FlateyjarbókDocument184 pagesFlateyjarbókgerson_coppesNo ratings yet

- (Occasional Papers in Archaeology, 15) Frands Herschend - The Idea of The Good in Late Iron Age Society-Uppsala University (1998)Document178 pages(Occasional Papers in Archaeology, 15) Frands Herschend - The Idea of The Good in Late Iron Age Society-Uppsala University (1998)alphancoNo ratings yet

- Viking Poems On War and Peace A Study in Skaldic Narrative PDFDocument242 pagesViking Poems On War and Peace A Study in Skaldic Narrative PDFadonisoinezpersonal100% (1)

- The Body Armour From Suton HooDocument10 pagesThe Body Armour From Suton HooStanisław Disę100% (2)

- Blood EagleDocument1 pageBlood EagleChristine Leigh Ward-WielandNo ratings yet

- Magnus Magnusson-The Dragon Ships The Great Age of Viking Expansion (1976)Document15 pagesMagnus Magnusson-The Dragon Ships The Great Age of Viking Expansion (1976)Various TingsNo ratings yet

- Alu and Hale II May Thor BlessDocument8 pagesAlu and Hale II May Thor BlessMehreen RajputNo ratings yet

- GullgubberDocument4 pagesGullgubberJ.B. Bui100% (1)

- SIMEK Tangible Religion - Amulets, Illnesses, and The Demonic Seven SistersDocument22 pagesSIMEK Tangible Religion - Amulets, Illnesses, and The Demonic Seven SistersBoppo GrimmsmaNo ratings yet

- Leszek Gardeła Warrior WomenDocument72 pagesLeszek Gardeła Warrior WomenSara Valls GalceràNo ratings yet

- Fuck Is AnDocument5 pagesFuck Is AnEngga Swari RatihNo ratings yet

- Hardsnuin Fraedi. Spinning and Weaving inDocument14 pagesHardsnuin Fraedi. Spinning and Weaving inJoão CravinhosNo ratings yet

- Berserkir - A Double LegendDocument0 pagesBerserkir - A Double LegendMetasepiaNo ratings yet

- Charles Riseley - Ceremonial Drinking in The Viking AgeDocument47 pagesCharles Riseley - Ceremonial Drinking in The Viking AgeGabriel GomesNo ratings yet

- Ore Iron Viking AgeDocument14 pagesOre Iron Viking Agefores2No ratings yet

- Robert Adams Horseclans 16 Trumpets of WarDocument109 pagesRobert Adams Horseclans 16 Trumpets of WarWajahatNo ratings yet

- Social Context of Norse JarlshofDocument112 pagesSocial Context of Norse JarlshofoldenglishblogNo ratings yet

- Magnus Magnusson - The Heroic Ethic: The Legend of Sigurd and The Code of The WarriorDocument12 pagesMagnus Magnusson - The Heroic Ethic: The Legend of Sigurd and The Code of The WarriorVarious TingsNo ratings yet

- Máel Coluim III, 'Canmore': An Eleventh-Century Scottish KingFrom EverandMáel Coluim III, 'Canmore': An Eleventh-Century Scottish KingRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Den Do Chronological Dating of The Viking Age Ship Burials at Oseberg, Gokstad and Tune, NorwayDocument9 pagesDen Do Chronological Dating of The Viking Age Ship Burials at Oseberg, Gokstad and Tune, NorwayFungusNo ratings yet

- Rheged: An Early Historic Kingdom Near The SolwayDocument25 pagesRheged: An Early Historic Kingdom Near The SolwayoldenglishblogNo ratings yet

- Repton - Norse Archeology, Viking EnglandDocument33 pagesRepton - Norse Archeology, Viking EnglandAksël Ind'gzulNo ratings yet

- Mcdonalds IngredientslistDocument23 pagesMcdonalds Ingredientslistsaxman011No ratings yet

- The Silk Road Textiles at Birka-An Examination of The TabletwovDocument11 pagesThe Silk Road Textiles at Birka-An Examination of The TabletwovFlorenciaNo ratings yet

- Viking WarfareDocument4 pagesViking WarfaretristagiNo ratings yet

- A Neglected Viking Burial With Beads From Kilmainham, Dublin, Discovered in 1847Document15 pagesA Neglected Viking Burial With Beads From Kilmainham, Dublin, Discovered in 1847oldenglishblog100% (1)

- A Social Analysis of Viking Jewellery From IcelandDocument533 pagesA Social Analysis of Viking Jewellery From IcelandJuan José Velásquez Arango100% (3)

- Wendish in Old Norse and NanlDocument33 pagesWendish in Old Norse and NanlДеан ГњидићNo ratings yet

- Øye (Ingvild) - Settlements and Agrarian Landscapes. Chronological Issues and Archaeological Challenges ( (16. Viking Congress, 2009)Document14 pagesØye (Ingvild) - Settlements and Agrarian Landscapes. Chronological Issues and Archaeological Challenges ( (16. Viking Congress, 2009)juanpedromolNo ratings yet

- Ragnar S SagaDocument45 pagesRagnar S SagaMari puriNo ratings yet

- Who Killed William Shakespeare?: The Murderer, the Motive, the MeansFrom EverandWho Killed William Shakespeare?: The Murderer, the Motive, the MeansRating: 2 out of 5 stars2/5 (2)

- Viking WomenDocument8 pagesViking Womenspompom88No ratings yet

- Hervarar Saga Ok HeiðreksDocument4 pagesHervarar Saga Ok HeiðreksLug TherapieNo ratings yet

- The Heirs of Ivar The BonelessDocument7 pagesThe Heirs of Ivar The BonelessScott HansenNo ratings yet

- The Viking Shield From ArchaelogyDocument21 pagesThe Viking Shield From ArchaelogyJanne FredrikNo ratings yet

- Kaupang and DublinDocument52 pagesKaupang and DublinPatrick JenkinsNo ratings yet

- AdamsRobert-02-Swords of The Horse ClansDocument64 pagesAdamsRobert-02-Swords of The Horse ClansIndia Lawson0% (1)

- Identity and Economic Change in The Viking Age: An Analysis of Ninth and Tenth Century Hoards From ScandinaviaDocument55 pagesIdentity and Economic Change in The Viking Age: An Analysis of Ninth and Tenth Century Hoards From ScandinaviaoldenglishblogNo ratings yet

- Norse SettlementDocument404 pagesNorse SettlementRamona Argolia HartleyNo ratings yet

- Documentation On The Re-Creation of A Pair of Medieval Hide ShoesDocument5 pagesDocumentation On The Re-Creation of A Pair of Medieval Hide ShoesFarid ElkhshabNo ratings yet

- Early Medieval Miniature AxesDocument9 pagesEarly Medieval Miniature AxesBoNo ratings yet

- Steel Viking SwordDocument6 pagesSteel Viking Swordsoldatbr4183No ratings yet

- Mesolithic Bows From Denmark and NortherDocument8 pagesMesolithic Bows From Denmark and NortherCharles CarsonNo ratings yet

- (the Northern Medieval World_ on the Margins of Europe) Alison Finlay, Þórdís Edda Jóhannesdóttir (Transl.) - The Saga of the Jómsvikings_ a Translation With Full Introduction-Western Michigan UniversDocument186 pages(the Northern Medieval World_ on the Margins of Europe) Alison Finlay, Þórdís Edda Jóhannesdóttir (Transl.) - The Saga of the Jómsvikings_ a Translation With Full Introduction-Western Michigan UniverszentropiaNo ratings yet

- BBC - History - Viking Weapons and WarfareDocument5 pagesBBC - History - Viking Weapons and WarfareCarla SigalesNo ratings yet

- Fafnismal Comparative StudyDocument10 pagesFafnismal Comparative StudyWiller Paulo Elias100% (1)

- Weaving Through The Highlands and Islands of Scotland - A Fiber Arts TourDocument10 pagesWeaving Through The Highlands and Islands of Scotland - A Fiber Arts TourEleanor MorganNo ratings yet

- Animais em Sepultura Na Islandia Viking PDFDocument115 pagesAnimais em Sepultura Na Islandia Viking PDFRafaellaQueiroz100% (1)

- 200711v1a GotlandResearchAndReplica Copyright Laura E StoreyDocument18 pages200711v1a GotlandResearchAndReplica Copyright Laura E StoreyRavnhild Ragnarsdottir100% (1)

- KostrupDocument28 pagesKostrupOrsolya Eszter KiszelyNo ratings yet

- English Old Norse DictionaryDocument0 pagesEnglish Old Norse DictionaryTomas Branislav PolakNo ratings yet

- Algonquin Spring: An Algonquin Quest NovelFrom EverandAlgonquin Spring: An Algonquin Quest NovelRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (4)

- Farming Transformed in Anglo-Saxon England: Agriculture in the Long Eighth CenturyFrom EverandFarming Transformed in Anglo-Saxon England: Agriculture in the Long Eighth CenturyNo ratings yet

- Revealing King Arthur: Swords, Stones and Digging for CamelotFrom EverandRevealing King Arthur: Swords, Stones and Digging for CamelotRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (1)

- St Peter-On-The-Wall: Landscape and heritage on the Essex coastFrom EverandSt Peter-On-The-Wall: Landscape and heritage on the Essex coastJohanna DaleNo ratings yet

- Heraldry For CraftsmenDocument136 pagesHeraldry For CraftsmenChristine Leigh Ward-Wieland100% (2)

- The Basics of Old Norse NamesDocument50 pagesThe Basics of Old Norse NamesChristine Leigh Ward-WielandNo ratings yet

- Viking Age HatsDocument3 pagesViking Age HatsChristine Leigh Ward-WielandNo ratings yet

- Structure of A Literary CycleDocument19 pagesStructure of A Literary CycleChristine Leigh Ward-WielandNo ratings yet

- Structure of A Literary CycleDocument19 pagesStructure of A Literary CycleChristine Leigh Ward-WielandNo ratings yet

- Viking ShipsDocument16 pagesViking Shipssamhines1100% (1)

- 5e Nautical Aderntures v2Document44 pages5e Nautical Aderntures v2Jessica100% (2)

- All About History Book of Vikings - (Future Publ) - Robert Macleod, M Stern, Et Al-2016-160pDocument160 pagesAll About History Book of Vikings - (Future Publ) - Robert Macleod, M Stern, Et Al-2016-160pmanfredm6435100% (3)

- Bretwalda - RulesDocument32 pagesBretwalda - RulesLlemanNo ratings yet

- G. C. Edmondson - The Ship That Sailed The Time StreamDocument141 pagesG. C. Edmondson - The Ship That Sailed The Time StreamdrqubitNo ratings yet

- Game Design - Shem Phillips Illustration - Mihajlo Dimitrievski Graphic Design & Layouts - Shem PhillipsDocument7 pagesGame Design - Shem Phillips Illustration - Mihajlo Dimitrievski Graphic Design & Layouts - Shem PhillipsPedro HenriqueNo ratings yet

- All About History Book of Vikings 2nd EditionDocument164 pagesAll About History Book of Vikings 2nd EditionMabb Mabu89% (18)

- A Feast For Odin - A Plain and Simple GuideDocument5 pagesA Feast For Odin - A Plain and Simple GuideBobNo ratings yet

- History of Water TransportationDocument11 pagesHistory of Water TransportationRussel Nicole RoselNo ratings yet

- Hisory Source Test - Viking Age NotesDocument6 pagesHisory Source Test - Viking Age Noteselina123No ratings yet

- Circles PDFDocument8 pagesCircles PDFCher Jay-ar DoronioNo ratings yet

- Nautical CompendiumDocument24 pagesNautical CompendiumMatias100% (1)

- Action Board Summary 1.02Document3 pagesAction Board Summary 1.02Adolfo LoayzaNo ratings yet

- The VikingsDocument3 pagesThe VikingsLuisNo ratings yet

- Piracy in Medieval Europe: Europe Before The VikingsDocument8 pagesPiracy in Medieval Europe: Europe Before The VikingsDczi BalzsNo ratings yet

- The Story of Burnt Njal From The Icelandic of The Njals Saga.Document357 pagesThe Story of Burnt Njal From The Icelandic of The Njals Saga.tobytony1429No ratings yet

- Advanced Fighting Fantasy - BlacksandDocument99 pagesAdvanced Fighting Fantasy - BlacksandBen Red Cap100% (3)

- A Feast For Odin - A Plain and Simple GuideDocument5 pagesA Feast For Odin - A Plain and Simple GuideArmand GuerreNo ratings yet

- Full Ebook of Conquest of The Danelaw 1St Edition H A Culley Online PDF All ChapterDocument69 pagesFull Ebook of Conquest of The Danelaw 1St Edition H A Culley Online PDF All Chapterrosinewhite100% (4)

- Topic 3 The Vikings (C. 790-1066) : 3.1.1 Links With Our TimesDocument40 pagesTopic 3 The Vikings (C. 790-1066) : 3.1.1 Links With Our TimesmaxxNo ratings yet

- Viking WarfareDocument4 pagesViking WarfaretristagiNo ratings yet

- Seafaring, Oops, I'm at Sea - 1st Edition AD&DDocument45 pagesSeafaring, Oops, I'm at Sea - 1st Edition AD&DRoberto CeppeNo ratings yet

- Old Norse Ship Names and Ship Terms by Rudolf SimekDocument11 pagesOld Norse Ship Names and Ship Terms by Rudolf SimekChristine Leigh Ward-WielandNo ratings yet

- Military Modelling - June 1981Document5 pagesMilitary Modelling - June 1981Anonymous uqCzGZINo ratings yet

- Naval Combat - Pathfinder 2e - GM BinderDocument26 pagesNaval Combat - Pathfinder 2e - GM BinderRodrigo Moraes100% (1)

- Vikings Student VersionDocument2 pagesVikings Student VersionReuben VarnerNo ratings yet

- Spears Thesis 2016Document123 pagesSpears Thesis 2016OlaOlofNigborNo ratings yet

- Dream Realm Storytellers - Into The Wolf's MawDocument63 pagesDream Realm Storytellers - Into The Wolf's MawGhoTouNo ratings yet

Old Norse Ship Names and Ship Terms by Rudolf Simek

Old Norse Ship Names and Ship Terms by Rudolf Simek

Uploaded by

Christine Leigh Ward-WielandOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Old Norse Ship Names and Ship Terms by Rudolf Simek

Old Norse Ship Names and Ship Terms by Rudolf Simek

Uploaded by

Christine Leigh Ward-WielandCopyright:

Available Formats

firstly,

26

OLD NORSE SHIP NAMES AND SHIP TERMS

Rudolf Simek

The nautical language of the North Sea Germanic area is a very

elaborate and rich terminology. This was no s ~ true at the time I

am dealing with, namely the period from the Viking Age up to about

1400 A.D. This nautical language seems heavily dominated by the

North Germanic languages, especially Old Norse. Therefore it may

well be justified to take Old Norse as a starting point when one is

dealing with the North Sea Germanic nautical terminology.

In the bit of research I have done on this field so far I have

mainly concentrated on the words meaning the ship as a whole. But

there are of course many other aspects to the nautical language, such

as shipbuilding, ship equipment, board life, journeys, and navigation.

This last aspect, navigation, is an especially tricky one. Alan Binns

from Newcastle has 'done important research in this field.

But as I said, I will limit myself to the words and phrases mean-

ing the ship as a whole. And here we have to deal with three groups

of terms:

proper names, of which about 150 are handed down

to us,

secondly, terms just meaning ship or boat of one kind or

another, and here we know of about 260 expressions

of this sort, and

thirdly, poetical circumscriptions, so called kenningar, of

which I Jound about 560 in Old Norse poetry.

I may now go into these three groups in further detail. As you

can see, the group of proper names is the smallest of these three. We

may distinguish here between two sorts of names, namely historical

ones and mythological ones. Of the so called historical ones, some

may of course be fictional, especially in the sagas of the Icelanders,

but quite a lot of them are mentioned either in a number of sources

or in historical documents.

We know from the Sagas of the Kings of Norway, that royal

ships were formally baptized in the 12th and 13th century; I may give

here as an example the speech King Sverre made in the spring 0 f 1183

at the launching of his new ship

"Thanks be to God, the blessed Virgin Mary and the blessed

king Olav, that this ship has come happily upon the water and

to no man's hurt, as many prophesied. - God forgive them all

the unkind words they threw at us for that. Now I may trust

that few here have seen a bigger longship, and it will greatly

serve to ward the land against our enemies if this proves a lucky

ship. I give it into the protection of the blessed Mary, naming

it Mariusuden, and I pray the blessed Virgin to keep watch and

ward over this ship. In testimony I \vill give Mary her own

such things as most belong to divine service. Vestments that

would be fine enough for even the archbishop though he wore

them on high days. And in return I expect that she will

remember all these gifts and give aid and luck both to the

ship and all who fare in it."

(Translation quoted from & Shetelig: The Viking

Ships, p. 212)

It should be mentioned, that the King had every reason to thank God

that the ship was in the water, as it had been lengthened against the

advice of his shipbuilders and was a rotten ship altogether, both ugly

to look at and hardly seaworthy, although it was huge.

But surely ships were formally baptized long before that, and

ship names even of the tenth century are handed down to us. Due to

the kind of sources we have on these centuries, mostly names of

royal ships are preserved. In the beginning ships were apparently

often simply given names of animals, for example Alptr "The swan",

Falki "The Hawk", Grap "The greygoose", Tr'-ni "The crane",

which was called so from its lofty prow, or Uxi "The ox", V(sundr

"The bison" or the famous Ormr inn langi "The long serpent" of

king Olaf Tryggvason. As far as these names occur on warships, they

probably carried an appropriate animal head as decoration on the end

of the stems. But the wooden dragonheads found at Oseberg are no

proof for this, as the word dragon was later much more of a synonym

for a big longship than a proper name, although it was originally one.

It really seems more likely to me, that Dreki "Dragon" was first the

27

28

name of King Harald's ship in the 870's and afterwards all the earls

and chieftains wanted to have a dragon too, so that the name turned

into a synonym for a longship this way, much rather than the other

way round, as some scholars argue, namely that Harald called his

flagship simply by the name of a longship.

From the beginning of the 12th century onwards we can observe

a__ change in customs. Ships would now be called after saints, such as

Olafssu<Y "St. Olafs ship", Petrsbolli "St. Peter's boat" Katrlnarsii<l

"St. Catherine's ship", or even after St. Mary or Christ. This was not

only, as one would expect, to place the ship under the guardianship

of the saint, but there was also political reasoning involved, as it was

of great importance to the various Norwegian rulers to secure the

support of the church. In the 14th century some of these ships may

have carried the image of the saint in one form or another. We are

told that even relics have been placed in the ships. It should be men-

tioned, however, that not only warships, but also trading vessels had

names from saints. But proper personal names in compounded ship

names do not necessarily refer to saints. Ships are also quite often

named after their owner or builder, as still is very common with

fishing vessels nowadays, for example Gunnarsbat "The boat of

Gunnar", Ragnaslo<li "King Rakni's longship (?)", or KristiforuSUd

"Christopher's ship". These types of names just mentioned belong

mainly to the 14th century, which does not mean that they did not

exist before that; but the kind of source is changing: now we can

rely mostly on annals and custom registers, and the names we find

are mostly names of trading vessels, such as names which give the

home country or home tow:n of the ship, like Rygiabrandr, called

after the people of Rogaland in Norway, or a tradingship

from the monastery Lysa in Norway, or simply Islendingr "The

Icelander". Some of these customs registers, which are published

in "Diplomatarium Norvegicum", are extremely rich sources for ship-

names, not only Scandinavian ones, but even for German, English and

French ones.

I may mention in this place an example of how easily one can

make mistakes in explaining names. The shipname Hasaugabliza in

the Hakonar Saga Hins Gamla had been explained by efficient German

scholars as being derived from ON h'r (gen. h's), a tholepin, and ON

auga, eye or hole, so that the name would refer to the open part of

the rowlock or the porthole for the oars. And there was much specu-

lation, in what \vay the portholes of this ship had been exceptional

enough to give it its name - until a Scandinavian scholar happened to

remark that there was a place called Haasauge, now HaIsaa in Norway,

from which the name, of course, is derived.

29

A large group of ship names belong to what I would call func-

tional names; they may be very similar to ship terms, and it can be

difficult to decide whether they are proper names or not, but sometimes

it is possible to decide this from the context or the writing in the

manuscript. So Biskupsb6za is known to mean the ship of a certain

bishop, whilst Biskupsskip just means a ship of a bishop. Or

Hoensabiiza "Henship" is a genuine name, but smorskip "Buttership"

is just a general term. Names of this sort we can find in most of our

sources throughout the centuries.

Next, there are poetical names such as v l b r ~ "Coolstem",

Fiar<Yakolla "Cow of the fjord", F{fa "Arrow", Gullbringa "Gold-

breast" or Skjoldr "Shield", and finally we find shipnames referring

to attributes and peculiarities of the ship, and which are surely rather

nicknames than anything else. So the ship of Bishop Nicolas, who

used to take his books with him on his journey, was called

Bokaskreppa "Bookbag"; another long and narrow one was called

Gom "Gut", and yet another, which was repaired with iron cleats

after having been wrecked, Jammeiss "Ironbasket". The saga of

Grettir gives a passage about a group of Norwegian merchants that

were shipwrecked in the north of Iceland and rebuilt their ship from

the wreckwood. But the ship was now rather broad and shapeless

and called Trekyllir "Woodbag".

There are of course a number of Old Norse shipnames which

we cannot explain. But probably people at that time liked to give

their boats deliberately cryptic names as much as people nowadays

do. .

I may now turn from the historical or pseudohistorical names

to the mythological ones. There are only 3 of this kind we know of,

and they are all rather interesting: skfclbla<lnir, Naglfar, and

Hringhomi.

30

was, according to Snorri Sturluson, the ship of the

god Freyr. It was built by dwarfs, had always fair winds, and could

be folded up and put into the pocket. The meaning of the name is,

as widely accepted today, "something made from flat pieces of wood."

But what the name really means is dubious. The name as well as

the myth mentioned by Snorri may date back, as I tend to believe, to

a cult venerating the god Freyr, and to a sort of monumental boat

erected on land for the duration of this feast and then taken apart

again. But it may also date back to the important innovation of the

plank built boat somewhere back in the Bronze Age. This idea has

not yet been exploited by scholars. was, according to

Snorri, the best of all ships, whereas Naglfar was the biggest. On

doomsday it will be launched and arrive, sailed by the sons of hell.

Various Scandinavian folk-tales from Iceland to Finland and even

further east know of this ship, and its name is usually explained by

them as "nail-ship", because the devil uses the uncut fingernails of

the dead to build this ship; so you had better clip the fingernails of

your dead before burying them, as this will postpone doomsday.

But the name may well come from a *n'-far "ship of the dead",

thus being cognate to Goth. naus "dead" or Lat. necare "to kill". If,

or how far, the myth about Naglfar was connected with the Scandi-

navian custom of ship-burials is still a matter of dispute.

The third ship occurring in myths is Hringhorni, the ship in

which the god Balder goes on his last journey. What the name means

we do not know. Some scholars explain it as a ship with a bent,

horn-shaped bow, which I can not find very convincing. I think it

might rather the round or spiral-shaped ornaments on the

stem-ends. But it is a rather surprising coincidence that there is a

ship-shaped stone-setting in Sweden, where a circle is engraved on

one of the stem stones. Is this stone setting commemorating Balder's

journey into death? But there are of course quite a lot of different

explanations of this and other finds of circular prow-decorations.

I may now leave the ship names and have a look at the ship terms.

As you can see there is'a large number of them, and they vary very

much in importance, age, and usage. There are purely technical terms,

but there are also poetical terms and then there is a number of words,

difficult to explain, which occur only in the lists of synonyms in

Snorri Sturlusons Edda, some of which are probably old words

31

already long died out, and others may be poetical words from poetry,

lost long ago.

I do not think there is much point in listing all the technical

terms for shp cropping up in the various ON sources. There are terms

referring to the size of ships by ways of using the number of oars, or

rowing benches, or shiprooms, and many others announcing the use

of the shiptype.

But only the big archaeological shipfinds in Norway, and the

more recent ones in Denmark give us some idea what sort of ships we

have to identify with these terms. I do not want to go into this here

in great detail, but you are surely all familiar with the ships of Gokstad

and Oseberg, which do not belong, as commonly supposed, to the

class of proper longships, nor have they been meant to sail the open

Atlantic, although a copy of the Gokstadship has successfully crossed

the North Atlantic in 1893. They both belong to the class of the

karfar, which were a sort of coastal cruiser, often also used for inland

expeditions in the east, sometimes used as private yachts of earls or

kings, but nevertheless fast warships of high merits.

Much more illuminating for the types of ships widely used in

the Viking Age than these royal yachts are the 5 ships found in the

Roskildefjord in Denmark. Her we have a proper longship, with its

93 feet length some twenty feet longer than the Oseberg ship. One

of the otherwrecks was a smaller warship of less than 60 feet, which

probably was a snekkja, the sort of ship frequently used in private

Viking raids. The other ships found at Roskilde served more peaceful

purposes. The smallest of about 40 feet length was either a big

fishing boat or a small coastal cargo boat, which were called ferjur,

while the biggest trader measured about 60 feet in length, but was

broad and very high-boarded and surely a good example of the so-

called knorr, the sort of trading vessel that was used for all overseas

routes, as to England, Iceland, and even Greenland.

But of course most of the ship terms we know about we cannot

identify with specific types of ships. But even so it is not uninteresting

to investigate them, as they give us an impression of when and in which

32

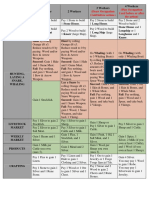

The 5 Viking Ships found in the Roskilde Fjord

.....

- __.. _-_._--------------._-----_ _--_..-_ --

1:

b:

kn01T

16.5 m

4.6m

langskib

1: 28 m

b: 4.2 m

byrdingr (?)

1: 13.3 ID

b: 3.3 ID

i i i i i j I i i 'r

kart;

1: 18 m

b: 2.6m

,

.

ferja (?)

1: 12 m

b: 2.5 m

direction words were moving in mediaeval North-West Europe.

To show this, I have chosen from 260 terms mentioned, about

100 basic or uncompounded terms. And of these, about 80% are

genuine Norse words, half of them having cognates in other Germanic

languages. Of the remaining 20% foreign or loanwords, nearly half

come from Latin, about a quarter from Middle Low German, and the

rest from Old or Middle English, Old Irish and Old Russian. But

33

Elevation of the Knorr

while nautical terms from the Norse filtered into other languages in

considerable numbers mainly during the late Viking period, most of

the loan words found in Old Norse appear from the beginning of the

13th century onwards. This is surely partly due to the rising power

of the Hanseatic towns in the North Sea trade.

The chronological distribution of terms can be shown in a table

like this

9th 10th 11th 12th 13th 14th century

knorr

barJi

ku gi

~ z

I have taken here a few obvious examples with a frequent occurrence,

but the recruiting of the words is often as problematical as the dating

of the sources. The word knorr, for example, the term already men-

tioned for a seagoing trader, is found throughout the whole period.

As another example I may use bar<li, a term for a man-of-war fashion-

able during the Viking Age, but soon on its way out. On the other

hand, there is kuggi, which comes from german Koge and probably

34

reflects the innovatio'n of the stern rudder and its introduction to the

North. Br'-gger and Shetelig state in their well-known book on the

Viking ships, that kuggi replaced the type of ship known under the

old name but if we have a closer look at this term, we can

prove this statement as wrong; b-fiza, moreover, is a loanword from

the Latin, possibly through Old French, but even in these languages

the word is not found before the middle of the 12th century, and we

may therefore dismiss the idea of the old Scandinavian ship type buza.

Another very interesting etymology is the one of the word-pair

ellidi - a ship name in the FriJpiofs saga - and leaja - a rare ship

term. A fair number of different etymologies for ellicn have been

tried, as for example as a loanword from AGS ydlida "wavewalker",

or from an *einlidi "the exceptionally fast sailing"; but I believe-

and I am not the only one to do so - that both words are derived

from an Old Russian oldji-a-, which turns through meta-

thesis into ladija/lodija in the first half of the 9th century. So elliJi

must have been borrowed before then, and ledja afterwards, but only

very shortly afterwards, as the vowel-change before i in Old Norse

ceases to be active around 900.

Another group of terms contains words of a purely poetical sort,

but not kenningar; it is only a small group of terms, and they may

have .been real ship terms in older days, but in the time of our Old

Norse sources they were limited to scaldic poetry: an example is beit,

the original Old Norse cognate to Old English bat, from which again

ON batr "boat" was borrowed. Or eik, that had otherwise lost the

nautical side of its meaning and apart from in poetry only meant oak-

tree in literary times, or flaust, originally meaning something floating,

or lung, probably being an old loanword from the Irish long, this

again being borrowed from Latin navis longa. To assign these terms

to certain boat types, as has been tried in the past, is of course com-

pletely absurd.

I would now like to leave the ship terms, although I have not

nearly exhausted this field, and move on to the last group of expres-

sions, namely the kenningar. As most of you will know this term

means a poetical circumscription of an object, and may consist of

2, 3, 4 or more elements, one of them being the so-called basic

element, which is better defined by one or more determinants; these

words are mainly nouns. This special poetical form was typical for

Norse and Icelandic scaldic poetry of the middle ages, but was used in

Iceland up to our times. Only a limited number of things has been

described by means of kenningar, such as poetry, women, warriors,

fights, blood, ships, swords and other weapons, and horses and other

animals, but apart from man himself the largest variety of kenningar

exists with the ship being the object. This shows, if nothing else

would, the high rank the ship held in the minds of the Scandinavians

of these times.

Firstly, there are kenningar consisting of only one word, which

means that they have to be compounded words. A common example

for this type is brimdyr "surfanimal". There are quite a lot of this

sort, like unnblakkr "wavehorse", or seglhundr "sailhound" or the

like. But we have also some more sophisticated ones like hasleipnir

"Odin's horse of the rowlocks", or hlunnbjom "bear of the wooden

rolls", the latter image taken from the clumsy expression given by a

ship that is dragged over land, or nice ones like fjar(Uinni "fjordser-

pent", or bortlvalr "boardfalcon", or brimsklcl "waveski".

By far the biggest group of kenningar consists, however, of two

words, although the principles of construction are practically the

same. So you can find ship-kenningar like vigg vastar "horse of the

fishing place", fagrdrasiII Iogstiga "beautiful horse of the seaway",.

vagn kjalar "carriage on a keel". But my personal favourites are

hestr svanfjalla "horse of the mountains of the swans (i.e. the waves)"

and hestr hvalfjardar "horse of the whaleearth (i.e. the sea)" or

hrofs hreinn "deer of the boathouse".

In kenningar consisting of 3 or 4 words the system is more or

less the same, and the only difference is that the determinant itself

consists of a kenning already. We have seen this possibility above in

kenningar like hestr svanfjaIla, where the second part is a genuine

kenning in one word. This way we get only a few, but very nice

kenningar, such as byrjar h'<1s blakkr "horse of the land of favourable

wind", g1atlr sl<S<la kjallar "horse of the way of the keels", r ~

35

36

Vandils jormungrundar "the carriage of the wiqe land of the sea king

Vandill", hreinn humra naustr "the deer of the boathouse of the

River Humber" or har<lvigg umbands allra landa " hard draught

horse of the belt of all lands", this belt, of course, being the sea.

\Vith this collection of a few examples I hope to have given

in short an impression of the richness and beauty of the Old Norse

nautical language.

References

Brf6gger, ~ v v & Shetelig, Hakon: The Viking Ships. Oslo 1953.

Egilsson, Sveinbjorn: Lexz'con Poeticum .l.4ntiquae Linquae

Septentrz'onalis. Ordbog over det norsk-islandske skjalde..

sprog.

2

by Finnur Jonsson. Copenhagen 1966.

Falk, Hjalmar: Altnordisches Seewesen. In Worter und Sachen,

Vol. IV, Heidelberg 1912, pp. 1-122.

Kahle, Bernhard: Altwestnordische Namensstudien. In

Indogermanz'sche Forschungen XIV (1930), pp. 133-224.

Olsen, Nlagnus: Gammelnorske Skibsnavn. In Nlaal og Minne

1931, pp. 33-43.

You might also like

- Lake TownDocument35 pagesLake TownSadisticSeraph100% (4)

- Into The Wolfs MawDocument63 pagesInto The Wolfs MawAndrew Stansfield75% (4)

- FlateyjarbókDocument184 pagesFlateyjarbókgerson_coppesNo ratings yet

- (Occasional Papers in Archaeology, 15) Frands Herschend - The Idea of The Good in Late Iron Age Society-Uppsala University (1998)Document178 pages(Occasional Papers in Archaeology, 15) Frands Herschend - The Idea of The Good in Late Iron Age Society-Uppsala University (1998)alphancoNo ratings yet

- Viking Poems On War and Peace A Study in Skaldic Narrative PDFDocument242 pagesViking Poems On War and Peace A Study in Skaldic Narrative PDFadonisoinezpersonal100% (1)

- The Body Armour From Suton HooDocument10 pagesThe Body Armour From Suton HooStanisław Disę100% (2)

- Blood EagleDocument1 pageBlood EagleChristine Leigh Ward-WielandNo ratings yet

- Magnus Magnusson-The Dragon Ships The Great Age of Viking Expansion (1976)Document15 pagesMagnus Magnusson-The Dragon Ships The Great Age of Viking Expansion (1976)Various TingsNo ratings yet

- Alu and Hale II May Thor BlessDocument8 pagesAlu and Hale II May Thor BlessMehreen RajputNo ratings yet

- GullgubberDocument4 pagesGullgubberJ.B. Bui100% (1)

- SIMEK Tangible Religion - Amulets, Illnesses, and The Demonic Seven SistersDocument22 pagesSIMEK Tangible Religion - Amulets, Illnesses, and The Demonic Seven SistersBoppo GrimmsmaNo ratings yet

- Leszek Gardeła Warrior WomenDocument72 pagesLeszek Gardeła Warrior WomenSara Valls GalceràNo ratings yet

- Fuck Is AnDocument5 pagesFuck Is AnEngga Swari RatihNo ratings yet

- Hardsnuin Fraedi. Spinning and Weaving inDocument14 pagesHardsnuin Fraedi. Spinning and Weaving inJoão CravinhosNo ratings yet

- Berserkir - A Double LegendDocument0 pagesBerserkir - A Double LegendMetasepiaNo ratings yet

- Charles Riseley - Ceremonial Drinking in The Viking AgeDocument47 pagesCharles Riseley - Ceremonial Drinking in The Viking AgeGabriel GomesNo ratings yet

- Ore Iron Viking AgeDocument14 pagesOre Iron Viking Agefores2No ratings yet

- Robert Adams Horseclans 16 Trumpets of WarDocument109 pagesRobert Adams Horseclans 16 Trumpets of WarWajahatNo ratings yet

- Social Context of Norse JarlshofDocument112 pagesSocial Context of Norse JarlshofoldenglishblogNo ratings yet

- Magnus Magnusson - The Heroic Ethic: The Legend of Sigurd and The Code of The WarriorDocument12 pagesMagnus Magnusson - The Heroic Ethic: The Legend of Sigurd and The Code of The WarriorVarious TingsNo ratings yet

- Máel Coluim III, 'Canmore': An Eleventh-Century Scottish KingFrom EverandMáel Coluim III, 'Canmore': An Eleventh-Century Scottish KingRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Den Do Chronological Dating of The Viking Age Ship Burials at Oseberg, Gokstad and Tune, NorwayDocument9 pagesDen Do Chronological Dating of The Viking Age Ship Burials at Oseberg, Gokstad and Tune, NorwayFungusNo ratings yet

- Rheged: An Early Historic Kingdom Near The SolwayDocument25 pagesRheged: An Early Historic Kingdom Near The SolwayoldenglishblogNo ratings yet

- Repton - Norse Archeology, Viking EnglandDocument33 pagesRepton - Norse Archeology, Viking EnglandAksël Ind'gzulNo ratings yet

- Mcdonalds IngredientslistDocument23 pagesMcdonalds Ingredientslistsaxman011No ratings yet

- The Silk Road Textiles at Birka-An Examination of The TabletwovDocument11 pagesThe Silk Road Textiles at Birka-An Examination of The TabletwovFlorenciaNo ratings yet

- Viking WarfareDocument4 pagesViking WarfaretristagiNo ratings yet

- A Neglected Viking Burial With Beads From Kilmainham, Dublin, Discovered in 1847Document15 pagesA Neglected Viking Burial With Beads From Kilmainham, Dublin, Discovered in 1847oldenglishblog100% (1)

- A Social Analysis of Viking Jewellery From IcelandDocument533 pagesA Social Analysis of Viking Jewellery From IcelandJuan José Velásquez Arango100% (3)

- Wendish in Old Norse and NanlDocument33 pagesWendish in Old Norse and NanlДеан ГњидићNo ratings yet

- Øye (Ingvild) - Settlements and Agrarian Landscapes. Chronological Issues and Archaeological Challenges ( (16. Viking Congress, 2009)Document14 pagesØye (Ingvild) - Settlements and Agrarian Landscapes. Chronological Issues and Archaeological Challenges ( (16. Viking Congress, 2009)juanpedromolNo ratings yet

- Ragnar S SagaDocument45 pagesRagnar S SagaMari puriNo ratings yet

- Who Killed William Shakespeare?: The Murderer, the Motive, the MeansFrom EverandWho Killed William Shakespeare?: The Murderer, the Motive, the MeansRating: 2 out of 5 stars2/5 (2)

- Viking WomenDocument8 pagesViking Womenspompom88No ratings yet

- Hervarar Saga Ok HeiðreksDocument4 pagesHervarar Saga Ok HeiðreksLug TherapieNo ratings yet

- The Heirs of Ivar The BonelessDocument7 pagesThe Heirs of Ivar The BonelessScott HansenNo ratings yet

- The Viking Shield From ArchaelogyDocument21 pagesThe Viking Shield From ArchaelogyJanne FredrikNo ratings yet

- Kaupang and DublinDocument52 pagesKaupang and DublinPatrick JenkinsNo ratings yet

- AdamsRobert-02-Swords of The Horse ClansDocument64 pagesAdamsRobert-02-Swords of The Horse ClansIndia Lawson0% (1)

- Identity and Economic Change in The Viking Age: An Analysis of Ninth and Tenth Century Hoards From ScandinaviaDocument55 pagesIdentity and Economic Change in The Viking Age: An Analysis of Ninth and Tenth Century Hoards From ScandinaviaoldenglishblogNo ratings yet

- Norse SettlementDocument404 pagesNorse SettlementRamona Argolia HartleyNo ratings yet

- Documentation On The Re-Creation of A Pair of Medieval Hide ShoesDocument5 pagesDocumentation On The Re-Creation of A Pair of Medieval Hide ShoesFarid ElkhshabNo ratings yet

- Early Medieval Miniature AxesDocument9 pagesEarly Medieval Miniature AxesBoNo ratings yet

- Steel Viking SwordDocument6 pagesSteel Viking Swordsoldatbr4183No ratings yet

- Mesolithic Bows From Denmark and NortherDocument8 pagesMesolithic Bows From Denmark and NortherCharles CarsonNo ratings yet

- (the Northern Medieval World_ on the Margins of Europe) Alison Finlay, Þórdís Edda Jóhannesdóttir (Transl.) - The Saga of the Jómsvikings_ a Translation With Full Introduction-Western Michigan UniversDocument186 pages(the Northern Medieval World_ on the Margins of Europe) Alison Finlay, Þórdís Edda Jóhannesdóttir (Transl.) - The Saga of the Jómsvikings_ a Translation With Full Introduction-Western Michigan UniverszentropiaNo ratings yet

- BBC - History - Viking Weapons and WarfareDocument5 pagesBBC - History - Viking Weapons and WarfareCarla SigalesNo ratings yet

- Fafnismal Comparative StudyDocument10 pagesFafnismal Comparative StudyWiller Paulo Elias100% (1)

- Weaving Through The Highlands and Islands of Scotland - A Fiber Arts TourDocument10 pagesWeaving Through The Highlands and Islands of Scotland - A Fiber Arts TourEleanor MorganNo ratings yet

- Animais em Sepultura Na Islandia Viking PDFDocument115 pagesAnimais em Sepultura Na Islandia Viking PDFRafaellaQueiroz100% (1)

- 200711v1a GotlandResearchAndReplica Copyright Laura E StoreyDocument18 pages200711v1a GotlandResearchAndReplica Copyright Laura E StoreyRavnhild Ragnarsdottir100% (1)

- KostrupDocument28 pagesKostrupOrsolya Eszter KiszelyNo ratings yet

- English Old Norse DictionaryDocument0 pagesEnglish Old Norse DictionaryTomas Branislav PolakNo ratings yet

- Algonquin Spring: An Algonquin Quest NovelFrom EverandAlgonquin Spring: An Algonquin Quest NovelRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (4)

- Farming Transformed in Anglo-Saxon England: Agriculture in the Long Eighth CenturyFrom EverandFarming Transformed in Anglo-Saxon England: Agriculture in the Long Eighth CenturyNo ratings yet

- Revealing King Arthur: Swords, Stones and Digging for CamelotFrom EverandRevealing King Arthur: Swords, Stones and Digging for CamelotRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (1)

- St Peter-On-The-Wall: Landscape and heritage on the Essex coastFrom EverandSt Peter-On-The-Wall: Landscape and heritage on the Essex coastJohanna DaleNo ratings yet

- Heraldry For CraftsmenDocument136 pagesHeraldry For CraftsmenChristine Leigh Ward-Wieland100% (2)

- The Basics of Old Norse NamesDocument50 pagesThe Basics of Old Norse NamesChristine Leigh Ward-WielandNo ratings yet

- Viking Age HatsDocument3 pagesViking Age HatsChristine Leigh Ward-WielandNo ratings yet

- Structure of A Literary CycleDocument19 pagesStructure of A Literary CycleChristine Leigh Ward-WielandNo ratings yet

- Structure of A Literary CycleDocument19 pagesStructure of A Literary CycleChristine Leigh Ward-WielandNo ratings yet

- Viking ShipsDocument16 pagesViking Shipssamhines1100% (1)

- 5e Nautical Aderntures v2Document44 pages5e Nautical Aderntures v2Jessica100% (2)

- All About History Book of Vikings - (Future Publ) - Robert Macleod, M Stern, Et Al-2016-160pDocument160 pagesAll About History Book of Vikings - (Future Publ) - Robert Macleod, M Stern, Et Al-2016-160pmanfredm6435100% (3)

- Bretwalda - RulesDocument32 pagesBretwalda - RulesLlemanNo ratings yet

- G. C. Edmondson - The Ship That Sailed The Time StreamDocument141 pagesG. C. Edmondson - The Ship That Sailed The Time StreamdrqubitNo ratings yet

- Game Design - Shem Phillips Illustration - Mihajlo Dimitrievski Graphic Design & Layouts - Shem PhillipsDocument7 pagesGame Design - Shem Phillips Illustration - Mihajlo Dimitrievski Graphic Design & Layouts - Shem PhillipsPedro HenriqueNo ratings yet

- All About History Book of Vikings 2nd EditionDocument164 pagesAll About History Book of Vikings 2nd EditionMabb Mabu89% (18)

- A Feast For Odin - A Plain and Simple GuideDocument5 pagesA Feast For Odin - A Plain and Simple GuideBobNo ratings yet

- History of Water TransportationDocument11 pagesHistory of Water TransportationRussel Nicole RoselNo ratings yet

- Hisory Source Test - Viking Age NotesDocument6 pagesHisory Source Test - Viking Age Noteselina123No ratings yet

- Circles PDFDocument8 pagesCircles PDFCher Jay-ar DoronioNo ratings yet

- Nautical CompendiumDocument24 pagesNautical CompendiumMatias100% (1)

- Action Board Summary 1.02Document3 pagesAction Board Summary 1.02Adolfo LoayzaNo ratings yet

- The VikingsDocument3 pagesThe VikingsLuisNo ratings yet

- Piracy in Medieval Europe: Europe Before The VikingsDocument8 pagesPiracy in Medieval Europe: Europe Before The VikingsDczi BalzsNo ratings yet

- The Story of Burnt Njal From The Icelandic of The Njals Saga.Document357 pagesThe Story of Burnt Njal From The Icelandic of The Njals Saga.tobytony1429No ratings yet

- Advanced Fighting Fantasy - BlacksandDocument99 pagesAdvanced Fighting Fantasy - BlacksandBen Red Cap100% (3)

- A Feast For Odin - A Plain and Simple GuideDocument5 pagesA Feast For Odin - A Plain and Simple GuideArmand GuerreNo ratings yet

- Full Ebook of Conquest of The Danelaw 1St Edition H A Culley Online PDF All ChapterDocument69 pagesFull Ebook of Conquest of The Danelaw 1St Edition H A Culley Online PDF All Chapterrosinewhite100% (4)

- Topic 3 The Vikings (C. 790-1066) : 3.1.1 Links With Our TimesDocument40 pagesTopic 3 The Vikings (C. 790-1066) : 3.1.1 Links With Our TimesmaxxNo ratings yet

- Viking WarfareDocument4 pagesViking WarfaretristagiNo ratings yet

- Seafaring, Oops, I'm at Sea - 1st Edition AD&DDocument45 pagesSeafaring, Oops, I'm at Sea - 1st Edition AD&DRoberto CeppeNo ratings yet

- Old Norse Ship Names and Ship Terms by Rudolf SimekDocument11 pagesOld Norse Ship Names and Ship Terms by Rudolf SimekChristine Leigh Ward-WielandNo ratings yet

- Military Modelling - June 1981Document5 pagesMilitary Modelling - June 1981Anonymous uqCzGZINo ratings yet

- Naval Combat - Pathfinder 2e - GM BinderDocument26 pagesNaval Combat - Pathfinder 2e - GM BinderRodrigo Moraes100% (1)

- Vikings Student VersionDocument2 pagesVikings Student VersionReuben VarnerNo ratings yet

- Spears Thesis 2016Document123 pagesSpears Thesis 2016OlaOlofNigborNo ratings yet

- Dream Realm Storytellers - Into The Wolf's MawDocument63 pagesDream Realm Storytellers - Into The Wolf's MawGhoTouNo ratings yet