Professional Documents

Culture Documents

History of San Clemente

History of San Clemente

Uploaded by

pcthompson8535Original Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

History of San Clemente

History of San Clemente

Uploaded by

pcthompson8535Copyright:

Available Formats

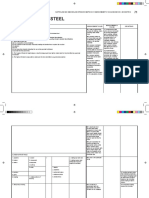

The Building History of the Medieval Church of S.

Clemente in Rome

Author(s): Joan E. Barclay Lloyd

Source: Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians, Vol. 45, No. 3 (Sep., 1986), pp. 197-

223

Published by: University of California Press on behalf of the Society of Architectural Historians

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/990159 .

Accessed: 28/01/2014 20:35

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at .

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of

content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms

of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

.

University of California Press and Society of Architectural Historians are collaborating with JSTOR to

digitize, preserve and extend access to Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians.

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded from 139.67.69.5 on Tue, 28 Jan 2014 20:35:12 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

The

Building History

of the

Medieval Church of S. Clemente

in Rome

JOAN

E. BARCLAY LLOYD LaTrobe

University

Although

the

early-12th-century

church

of

S. Clemente is one

of

the

most

significant

medieval monuments in

Rome,

there have been

few

studies in recent

years of

its architectural

layout

and structure. An

architectural

survey of

the

building by

the author and Mr.

J.

M.

Blake, FRIBA, helps

to

clarify

the

original design of

the church and

to indicate its successive

building phases:

a late-

11th-century

renova-

tion

of

the

lower, Early

Christian

basilica;

the

rebuilding of

the entire

upper

church in one

campaign by

Cardinal Anastasius

(c.

1099-

c.

1125);

and the construction

of

most

of

the atrium and

prothyron

by different workshops, perhaps

at a later date

by "Petrus,"

who is

reported

to have

completed

Cardinal Anastasius's

project.

Alternatively,

"Petrus"

may

have built one or all

of

a number

of

subsidiary structures,

known

from documentary

and

graphic

sources: a

medieval bell

tower,

a

sacristy,

the

chapel of

Saint

Cyril,

and the

oratory of

Saint

Servulus.

The

building history of

the medieval church is set within the

broader

historicalframework of

the

Gregorian Reform of

the Church

and the

12th-century

renascence

of Early

Christian architecture in

Rome.

Comparisons

can be made with the architectural

layout

and

liturgy of

the Lateran and Old St. Peter's.

A

15th-century document,

which

gives

the

wording of

an

inscrip-

tion

formerly

in the

church, refers

to

indulgences granted by Pope

Gelasius

II (1118-1119).

This

suggests

a date

of

consecration

prior

to

January 1119,

when that

pontiff

died.

THE CHURCH of S. Clemente stands between the Colos-

seum,

which was at the heart of Ancient

Rome,

and the

Lateran,

the site of the

city's

cathedral and the

pope's

residence

in the Middle

Ages.

An

Early

Christian

basilica,

which was

restored in the 9th and

again

in the 11th

century, preceded

the

present

medieval structure at S.

Clemente,

which was built in

the

early

12th

century.

This church is one of the most

signifi-

cant monuments of medieval Rome.

It is a well-known fact that there were

two,

and

possibly

three,

building campaigns

at S. Clemente in the late 11th and

early

12th centuries.

First,

the lower church

(the Early

Chris-

tian

basilica)

was

restored, perhaps shortly

after

1084;1

under

Cardinal Anastasius

(c. 1099-c. 1125)

an

entirely

new church

was built

higher up

and to a smaller

scale;2

finally, a

fragmen-

tary inscription suggests

that a certain Petrus

completed

the

upper

church after the Cardinal's

death.3

It is the aim of this

paper

to re-examine the evidence for these

campaigns,

in an

attempt

to

clarify

the

building history

of the church in the later

Middle

Ages.4

1. This would relate the medieval

repairs

to the Norman incursion

of 1084 under Robert

Guiscard, mentioned in Le Liber

Pontificalis,

ed.

L.

Duchesne, Paris, 1886-1892, ii, 291,

368. This

theory

will be dis-

cussed more fully

below.

2. Documentation for this

campaign

and Cardinal Anastasius's

dates will be treated more

fully

below.

3.

Again,

this will be discussed more

fully

below.

4. This

paper

is based on conclusions reached in

J.

E.

Barclay

Lloyd,

"The architecture of the medieval church and conventual

buildings

of S. Clemente in

Rome, c. 1080-c.

1300," Ph.D.

diss.,

London

University,

1980.

I

wish to thank Professor

J.

Gardner for

supervising

that

study

and Professor R. Krautheimer for his constant

encouragement

and

many helpful suggestions.

A revised version of

my thesis, The medieval church and

canonry of

S. Clemente in

Rome,

is to

be

published shortly by

the Irish Dominicans in

Rome, in their San

Clemente

Miscellany

series.

The

survey plans

and sections

published

as

Figs.

5 and 7 form

part

of a

survey

made

byJ.

M.

Blake, FRIBA,

and

myself; I

am

responsible

for the addition of the various

types

of

masonry. My

thanks

go

to

Mr. Blake for

carrying

out the

survey

and to Dr. D. Michaelides

for

helping

me to

identify

the materials of the S. Clemente columns

(Table I).

JSAH

XLV:197-223. SEPTEMBER 1986 197

This content downloaded from 139.67.69.5 on Tue, 28 Jan 2014 20:35:12 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

198

JSAH, XLV:3, SEPTEMBER 1986

o 6o ,,T

;..

:.....

L

| i ?

-

"

,I,...

,

.

...

.

,.,

"-'.-

2o MhTlhS

-"

..

' -'

".

?"

\

?"?\

-

'

.

, ,

?

"

. - ?

"

,.

".-..

?

-,-, .

.. .

-,-:..

--..q,

-.::.

-..~d

....~L

.:-

,...-" --,

..r- . ..

-.-.. .--'-

Fig.

1.

Rome, S.

Clemente, lower basilica, late 4th or

early

5th

century,

reconstruction

(from

R. Krautheimer, Early

Christian and

Byzantine Architecture,

2nd

ed., Harmondsworth, 1975, Fig. 132).

V

o

Early

Christian

eleventh

century

twelfth century

Fig.

2. S. Clemente,

lower basilica,

south aisle wall, elevation

(drawing: Barclay Lloyd,

after Krautheimer, Corpus, I, Tav. xvIIi, 2).

Since the

19th-century

excavation of the lower basilica

by

Father

Joseph Mullooly, O.P.,

most scholars have concen-

trated on the

early history

of the site, leaving

aside the beauti-

ful medieval

upper

church.s

From their studies a reconstruc-

tion can be made of the lower basilica

(Fig. 1).

The church was

built into and above a

large

Roman

building,

and oversailed a

narrow

alleyway

and the remains of a Roman house;

it was

entered from the east and had its

sanctuary

in the west. In

plan

it was a basilica with a

nave,

two aisles,

and an

apse;

it was

preceded by

a

rectangular

colonnaded atrium, which, except

for its western

portico,

remains to be excavated. The church

was 35.95 m

long;

the nave was 15.34 m

wide,

the aisles

5.81 m and 5.31 m wide.

Eight

columns

separated

the nave

and

aisles;

four more columns stood in the

fagade.6

The colon-

nades

supported

arcades. The

clerestory, rising

to a

height

of

13.36

m,

was

pierced by large

round-headed windows.7

Along

both the north and south aisle walls there had

been,

in

the

pre-existing

Roman

building,

several wide

openings.

In

the

Early

Christian

building campaign

all save a

rectangular

window in the east end of the north aisle wall were blocked;

at

the same time in the south aisle wall the easternmost

opening

was filled in and the three closest to the west were made

narrower, leaving

a small

doorway

in the

east,

followed

by

5. For the

history

of the excavation,

see: L. E.

Boyle, O.P.,

San

Clemente

Miscellany I: the

community of

SS. Sisto e Clemente in

Rome,

1677-1977, Rome, 1977, 171ff., andJ. Mullooly,

O.P.,

Saint Clement

Pope

and

Martyr

and his basilica in

Rome, Rome, 1869,

2nd

ed., 1873.

Father

Mullooly's

discoveries were discussed in G. B. De Rossi, "Dati

cronologici

e storici circa i monumenti . . . di San Clemente,"

Bullettino di

Archeologia

Cristiana, III (1870),

141ff.,

and idem,

"I

monumenti

scoperti

sotto la basilica di San Clemente,"

Bullettino di

Archeologia,

2a Serie,

I

(1870),

125ff.

The

following

studies have been made of the

Early

Christian basil-

ica and its antecedent

buildings:

C. Cecchelli, San Clemente

(Le

Chiese

di Roma illustrate, 24-25),

Rome, 1930;

E.

Junyent,

"La

primitiva

basilica di San Clemente," Rivista di

Archeologia Cristiana,

5

(1928),

231ff.; idem, Il Titolo di San Clemente in Roma, Rome, 1932; R.

Krautheimer, Corpus

Basilicarum Christianarum Romae,

Vatican

City,

1937, I, 117ff.;

M. Cecchelli Trinci,

"Osservazioni sulla basilica

inferiore di S. Clemente in Roma,"

Rivista di

Archeologia Cristiana,

50

(1974), 93ff.;

and F. Guidobaldi,

"Il

complesso archeologico

di San

Clemente"

(with

a new

survey plan, Tav. v)

in L. E.

Boyle, O.P.,

E.M.C. Kane,

and F. Guidobaldi, San Clemente

Miscellany

II: Art and

Archeology,

ed. L.

Dempsey, O.P., Rome, 1978,

215ff.

6. This kind of

fapade opening

seems to have been common in

Early

Christian basilicas in Rome in the late 4th and

early

5th centur-

ies;

see G. Matthiae,

"Basiliche

paleocristiane

con

ingresso

a

polifora,"

Bollettino d'Arte,

42

(1957),

107ff.,

and R. Krautheimer, Early

Chris-

tian and

Byzantine Architecture, Harmondsworth,

2nd ed., 1975,

180ff.

and n. 8.

7. Krautheimer, Corpus, I,

132 and 129ff.

This content downloaded from 139.67.69.5 on Tue, 28 Jan 2014 20:35:12 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

BARCLAY LLOYD: BUILDING HISTORY OF S. CLEMENTE, ROME 199

three others and a

large

window

(Fig. 2)."

This

Early Christian

basilica seems to have been built in the late 4th or

early 5th

century .9

The church of S. Clemente was renovated in the late 8th and

mid 9th centuries. The roof was restored

by Pope

Hadrian

I

(772-795)."o

Further

repairs

were undertaken

by Pope

Leo IV

(847-855), possibly following

an

earthquake

in Rome in Au-

gust

847." In this

campaign

a wall was built to block the

southernmost intercolumniation in the

fagade

(Fig. 3, n) and

the walls of the basilica were decorated with murals-one, of

the

Ascension,

on the inner face of the fagade blocking.12

The

building history

of S. Clemente in the 11th and 12th

centuries has been treated most

fully

in recent

years by Junyent

and

Boyle.13 Junyent

clarified the relation of the

upper

to the

lower

church,

discussed

epigraphic

and

documentary sources

connected with the medieval

rebuilding,

and described the

church as it stood in the

early

12th

century.

Father

Boyle,

in a

masterful study, disentangled some misunderstandings about

the medieval patron, Cardinal Anastasius, and pointed out

that a date of 1128 for the consecration of the church was

untenable, since the historical evidence for it was related to

another church of the same name in Tivoli. Other studies have

concentrated, not on the architectural

history of the church,

but on the later medieval murals in the lower basilica and on

the magnificent mosaic in the

12th-century apse and its sur-

rounding

arch.14

A few scholars have included the medieval

church of S. Clemente in more

general works on Rome in the

Middle

Ages.15

Despite all these studies, numerous

questions related to the

date and building history of the church in the late 11th and

early 12th centuries remain unresolved. In this paper a fresh

investigation will be made of the archaeological, literary, and

graphic evidence for this medieval

phase

at S. Clemente. We

hope

to

clarify

some

points,

or at least

suggest

some new

solutions in the

perplexing history of this

fascinating monu-

ment. We shall discuss first the

late-11th-century restoration

of the lower basilica, then the

building

of the

upper

church

by

Cardinal Anastasius; we shall consider the extent of his cam-

paign and

suggest what

might have been

completed by

"Petrus"; finally,

we shall

propose

an alternative date of con-

secration for the medieval church.

I. The

11th-century

restoration

of

the

Early

Christian basilica

From an examination of the

masonry,

it

appears

that the

late-11th-century

renovation of the

Early

Christian basilica

affected the southern side and

fagade

of the

building. Two

piers (Fig. 3,

p

and

q)

were built around columns in the south

colonnade; these

piers carry

the

11th-century

murals of Saint

Clement and Sisinnius and the Legend of Saint Alexis.16 One, or

possibly two, of the

openings in the south aisle wall were

blocked

up (Figs. 2, 3, v and

possibly o). The

fagade

arcade

was further filled in

(Fig. 3, r, s, and

possibly w);

the murals

8.

Ibid., 127.

9. Scholars

disagree

about its date or construction. On the basis of

a

fragmentary inscription,

De Rossi

assigned

it to the

pontificate

of

Pope

Siricius

(384-399),

De

Rossi,

"I

monumenti," 125ff.

Junyent

believed the

preceding

Roman

building

was transformed into a church

in two

phases, taking

its basilical

plan only

in

514-535; Junyent, II

Titolo,

153ff. Krautheimer dated it c. 390 or before

385; Krautheimer,

Corpus, I, 132-134. Guidobaldi

proposed that, after an initial

restructuring

of the earlier Roman

building,

it was transformed into a

basilica in the first half of the 5th

century; Guidobaldi, "Il

complesso

archeologico,"

296.

10. "Tectum vero tituli beati Clementis

quaejam

casuram erat et in

ruinis positum regionis

tertia a noviter

restauravit," Liber

Pontificalis,

I,

505.

Junyent,

II

Titolo, 161, assumed this restoration affected the

whole

building ("tutto l'edificio"),

but

Krautheimer,

Corpus, I,

118

n.

2, points

out that one should not overrate the extent of this

renovation.

11. The

earthquake

is described in the Liber

Pontificalis, II, 8:

"Huius

beati tempore praesulis

terremotus in urbe Rome

per

indicti-

onem factus est

X, ita ut omnia elementa concussa viderentur ab

omnibus."

Junyent, II

Titolo,

161 n. 3, first connected this

earthquake

with

Pope

Leo IV's work at S. Clemente.

12. The

early murals, from the 8th and 9th

centuries, have been

studied most

recently by J. Osborne, Early

Mediaeval

Wall-Paintings

in

the Lower Church

of

San

Clemente, Rome,

New

York, 1984; idem, "The

portrait

of

Pope

Leo IV in S. Clemente in

Rome

...

"

Papers of

the

British School at

Rome,

47

(1979), 58ff.; idem, "The

painting

of the

Anastasis in the lower church of S. Clemente .

..

," Byzantion,

51

(1981), 255ff.; idem, "Early

medieval

paintings

in San

Clemente,

Rome: the Madonna in the

niche," Gesta,

XX.2

(1981), 299ff.; idem,

"The

Christological

scenes in the nave of the lower church of San

Clemente, Rome," in D.

Andrews, J. Osborne, and D.

Whitehouse,

Medieval Lazio: Studies in Architecture

Painting

and

Ceramics,

Oxford

(BAR 125), 1982, 237ff., and

idem, "Early

medieval

wall-paintings

in

the church of San

Clemente, Rome: the Libertinus

cycle

and its

date,"

Journal of

the

Warburg

and Courtauld

Institutes,

45

(1982),

182ff.

13. E.

Junyent,

"La basilica

superior

del Titol de Sant

Clement,"

Analecta Sacra

Tarraconensia,

6

(1930), 251ff.; Junyent, II Titolo,

passim, esp. 186ff.; L. E.

Boyle, O.P.,

A short

guide

to St. Clement's

Rome, Rome, 1972; idem, "The date of consecration of the basilica of

San

Clemente," in

Boyle, Kane, and

Guidobaldi, San Clemente Miscel-

lany n,

1ff.

14. For the

11th-century

frescoes in the lower

church, see: G.

Ladner, "Die italienische Malerei im 11.

Jahrhundert," Jahrbuch

der

kunsthistorischen

Sammlungen

in

Wien, N.F.,

5

(1931), 63ff.; E. B.

Garrison, Studies in the

history of

medieval Italian

painting, Florence,

1953, I, 1ff.; H.

Toubert, "Rome et le

Mont-Cassin," Dumbarton Oaks

Papers, 30

(1976), 3ff.; and E.

Kane, "The

painted

decoration of the

church of San

Clemente," in

Boyle, Kane, and

Guidobaldi, San

Clemente

Miscellany

Ii,

60ff.,

esp.

80ff.

For the mosaics in the

upper

church see: S. Scaccia

Scarafoni, "I1

mosaico absidale di S. Clemente in

Roma," Bollettino

d'Arte, XXIX,

II (1935),

serie

III,

49ff.,

with a dubious

political interpretation;

H.

Toubert, "Le renouveau

paleochretien

a Rome au debut du

XIIe

siecle," Cahiers

Archeologiques,

20

(1970), 99ff.; and

Kane, "The

painted decoration," 99ff.

15. For

example,

R.

Krautheimer, Rome:

Profile of

a

City,

312-

1308, Princeton, 1980, 161, 163ff.

16. For these and other

murals, see the works cited in n. 14.

This content downloaded from 139.67.69.5 on Tue, 28 Jan 2014 20:35:12 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

200

JSAH, XLV:3, SEPTEMBER 1986

IL II

F II

II

X

4

4

I~I !E

II

,

ii

(28)t;-

(28)

* I

III

II

Ii

I

(1

2"

e

k

II II

I

CII

III

III

ItI

IL

,--. .

,I m ..I

S. CLEMENTE

PLAN AND RECONSTRUCTION

Medieval

repairs

to

Early

Christian

buildings

Fig.

3. S. Clemente, lower

basilica, plan

and reconstruction, medieval

repairs

to

Early

Christian

buildings (Barclay

Lloyd).

This content downloaded from 139.67.69.5 on Tue, 28 Jan 2014 20:35:12 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

BARCLAY LLOYD: BUILDING HISTORY OF S. CLEMENTE, ROME 201

of the Translation

of

Saint

Clement/Cyril

and the Miracle at

Chersona were

painted

on our walls r and s.

Probably

at the

same time a wall was

built, running

northwards from the

north aisle wall

(Fig. 3, t).

The

11th-century blockings

in the

fapade,

the

piers

in the

south

colonnade,

and the wall

running

north of the church

(Fig. 3, p, q, r, s,

and

t)

are all built in a distinctive

type

of

brickwork. The

bricks,

all reused and c.

17,

22 /2 cm

long,

are

laid in

fairly straight

rows in

pale gray, finely

textured mortar,

which is smoothed over the bricks and marked with a hori-

zontal line made with the

tip

of the mason's

trowel-falsa

cortina

pointing.7

The mortarbeds are 3, 31/2,

or 4 cm

high;

and a modulus of five rows of bricks and five mortarbeds

measures

30, 301/2, 311/2,

or 32 cm.

As has been

pointed

out in a

separate study,

this

type

of

brickwork occurs in several other medieval structures in

Rome,

some of which can be

firmly dated."'

The earliest se-

curely

dated

example

of this

masonry

is to be found in the first

Romanesque rebuilding phase

at SS.

Quattro Coronati, c.

1099-before 1116.19 Since the

repairs

to the lower basilica of S.

Clemente are

generally

believed to

predate

that

campaign,

this

in not

very helpful.

Falsa cortina

pointing is, however, re-

corded as

early

as 1060 in the mortarbeds of a kind of

opus

listatum

(alternating

rows of stone and

bricks)

at the

abbey

of

Farfa.20 In Rome it

appears

at S.

Pudenziana,

in the

repointing

of an Ancient Roman

wall, perhaps

as

early

as

1073-1085,

and

it continued to be used until c. 1205.21 If the

early

date is

correct,

it would mean that the walls under discussion at S.

Clemente could have been built at

any

time from the

pontifi-

cate of

Gregory

VII

(1073-1085)

to the decision to rebuild the

church

by

Cardinal Anastasius

(c.

1099-c.

1125).

Falsa cortina

pointing

seems to have been the hallmark of

certain

groups

of masons in Rome in the late 11th and 12th

centuries;

it does not occur in all

buildings

of that date in the

city.22 Indeed,

the builders of the main

body

of the

upper

church of S. Clemente did not finish the mortarbeds in this

way.

Hence its occurrence in the lower basilica can

perhaps

be

used to determine the extent of the

late-11th-century

restora-

tion

campaign.

Besides the walls discussed so

far, falsa

cortina

pointing oc-

curs in a small

irregular blocking

in the south aisle wall (Figs.

2, 3, v),

which

may

have been a small

doorway.

The

masonry

of the

blocking

is

opus listatum, not brickwork, but the

falsa

cortina

pointing

is

very

clear. At

blocking

o in the same wall

there is similar

masonry,

but the

pointing

is less obvious and

may, indeed,

be the result of a modern

repair.

The mortar in

the other

blockings

of this wall is not treated this

way and

probably

dates from the time of Cardinal Anastasius's rebuild-

ing

of the church. In the

fapade

wall of the lower church there

may

have been a

late-11th-century blocking

at

point

w: a

19th-century pier

there has the

impression

of

falsa

cortina

pointing

in reverse

along

its mortarbeds.23 A few

fragments of

brickwork with

falsa

cortina

pointing

are scattered

among

the

stone foundations of the south colonnade of the

upper

church:

they may

be

part

of an

11th-century

wall that was demolished

at the time the foundations were built.

From the evidence that

survives, it

appears

that walls

p, q,

r, s, v, and

possibly

o and w were built to

strengthen

the

Early

Christian basilica in the late 11th

century;

a new wall t

may

have been built at the same time to connect the church to

structures on the

north.24 Most

of the

repairs

to the

Early

Christian basilica affected the

fapade

and south side of the

church. The

filling-in

of the

fapade

and the south aisle seems

fairly logical,

since it was unusual in the Middle

Ages

to have

so

many openings along

those sides of a

church,

but the

piers

in the south colonnade

suggest

that this

part

of the structure

was

damaged

or unstable.

(Three

columns are now

missing

from this

colonnade,

as well as one in the north

colonnade,

but

these

may

have been

remoyed

when the church was

rebuilt.)

It is

generally

assumed that the

11th-century

restoration of

the lower basilica was connected to broader historical circum-

stances. In the late 11th

century

the titular cardinals of S.

Clemente

appear

to have taken sides in the issues raised

by

the

Gregorian

Reform of the

Church.25

In 1073 a

synod

in Rome

condemned

Hugo,

Cardinal of S.

Clemente,

for

supporting

17. For

my

use of the term

'"falsa

cortina

pointing," seeJ.

E.

Barclay

Lloyd, "Masonry techniques

in medieval

Rome, c. 1080-c.

1300,"

Papers of

the British School at

Rome,

53

(1985), 225ff., esp.

227.

18.

Barclay Lloyd, "Masonry techniques,"

237ff. and Tab.

III,

269ff.

19.

Ibid., 228, 237ff., 245, 269.

20. C.

McClendon, "The medieval

abbey

church at

Farfa," Ph.D.

diss.,

New York

University, 1978, 67, 89, Figs. 70, a,

b for

falsa

cortina

pointing; 32, 105ff. for the

11th-century

date.

21.

Barclay Lloyd, "Masonry techniques,"

238.

22.

Ibid., 225ff., esp.

237ff.

23. This was

pointed

out to me

by

Dott. F. Guidobaldi.

Probably

.he

19th-century pier

was built

against

an

11th-century blocking,

which was

subsequently

removed to allow

easy

access to other

parts

of the excavations; no doubt, if this were the case, the 11th-

century

wall was considered

unimportant

because it carried no

painted

decoration.

24. Wall t is accessible

through

a hole under the

present postcard

room; its

masonry

is similar to that of

p, q, r, and s.

25. For the

Gregorian Reform, see: A.

Fliche,

La

Reforme Gregori-

enne, Paris, 1924-1966; idem, La

Reforme Gregorienne

et la

Reconquete

chretienne

(1057-1123),

Histoire de

l'Eglise,

ed. A. Fliche and V.

Martin,

Paris, 1950,

III;

and R.

Morghen, Gregorio VII e la

Riforma

della Chiesa

nel secolo

XI,

revised

ed., Palermo, 1974. The effect on the

city

of

Rome of this reform movement is

briefly

discussed in

Krautheimer,

Rome, 148ff.

This content downloaded from 139.67.69.5 on Tue, 28 Jan 2014 20:35:12 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

202

JSAH, XLV:3, SEPTEMBER 1986

Cadolus

against Pope Gregory VII;26 although

he was de-

nounced,

the Cardinal was

evidently

not

deposed,

for on 24

June

1080

"Hugo Candidus," probably

the same

man, signed

a document as titular of the church.27

Pope Gregory

VII subse-

quently

consecrated as S. Clemente's cardinal a

pro-Gregorian

monk, Rainerius,

who was renowned for his

dignity, integ-

rity,

natural

ability,

and

prudence.28

Toward the end of

Gregory

VII's life,

in

1084,

the

Pope

was

besieged

in Castel

Sant'Angelo by imperial troops,

who had

taken Rome and installed an

imperial anti-pope,

Clement III

(Wibertus

of

Ravenna),

in his stead. The Normans from

southern

Italy,

led

by

the Prince of

Salerno,

Robert Guiscard,

came to

Gregory's

rescue. In one

account,

the Norman

army

is said to have entered Rome

through

the Porta Flaminia

(Porta

del

Popolo)

and inflicted

grave damage

on the

neigh-

borhood around S. Silvestro in

Capite

and S. Lorenzo in

Lucina. From there the

troops

made their

way

to Castel

Sant'Angelo,

where

they

took

Gregory

under their

protection

and escorted him back to the

Lateran, but not without

outbreaks of

violence, looting,

and

rape

on the

way. Finally,

the areas around the Lateran and Colosseum were set

alight.29

Another version describes a fire between the Lateran and the

Colosseum,

as the Normans entered the

city.30

In some

points

the two accounts are

contradictory:

the first

says

Guiscard

entered Rome

through

Porta

Flaminia,

the second

gives

the

impression

that he came into the

city

near the Lateran.

Both,

however,

describe a fire in the Lateran-Colosseum

neighbor-

hood,

where S. Clemente is

situated;

the extent of the

damage

this caused is not clear.

The

nearby

church of SS.

Quattro

Coronati seems to have

been

destroyed,

a fact confirmed

by

the vast

quantity

of

charred marble that came to

light

when the church and monas-

tery

were restored at the

beginning

of this

century."3 Pope

Paschal

II (1099-1118) began rebuilding

that church on a

large

scale c.

1099,

but later constructed a smaller

church,

which he

consecrated on 20

January 1116.32

The reason for the

11th-century

restoration of the lower

basilica of S. Clemente and its date have been the

subject

of

scholarly

debate. Father

Mullooly

believed that the lower

church was abandoned after Guiscard's devastation of the

Lateran

area;33

he believed that the

piers

in the south colonnade

and in the

fagade

wall were built before the disaster of 1084.

G. B. De

Rossi, on the other

hand, thought

the medieval

rebuilding

of the

Early

Christian church had been caused

by

the basilica's

great age

and the mass of debris

piled up

around

it.34 J. Wilpert thought

the church was

merely damaged

in

1084 and hence

required strengthening piers

in its south colon-

nade and

fapade;

he dated these

piers shortly

after 1084 and

prior

to the

rebuilding

of the church on a

higher

level in the

early

12th

century.35

Most modern scholars follow this last

interpretation.

It must be

admitted, however,

that there are no

traces

of a fire in the lower basilica. De Rossi's

hypothesis

could well be correct. It is also

possible

that the church was

damaged by

an

earthquake

or some other natural disaster. D.

Kinney

has found reference to a severe

earthquake

in Rome in

1091, which she thinks

may

have been

strong enough

to cause

the

rebuilding

of S.

Crisogono

and S. Maria in Trastevere

early

in the 12th

century.36

Such an

earthquake might

have led

to the restoration of the lower church of S. Clemente.

By

1099 the church seems to have been in

good enough

repair

for a

papal

election to be held there on 14

August,

at

which S. Clemente's titular

cardinal, Rainerius,

was elected

pope;

he took the name Paschal II. This event is described in

great

detail in the Liber

Pontificalis.37

A

large

number of

people

gathered

in the

basilica.38

The new

Pope

was elected and ac-

26.

". .. Ugonem

cardinalem tituli sancti

Clementis . . . ab

apolostica

sede

dampnatum,

eo

quod aspirator

et sotius factus haeresis

Cadoli

Parmensis

episcopi,

similiter

usque

ad

satisfactionem anathe-

mate

percussit";

Liber

Pontificalis, II, 284.

27.

"Ego Hugo

Candidus sanctae romanae Ecclesiae

presbyter

cardinalis,

de titulo sancti Clementis

regionis tertiae Urbis," quoted

in

Junyent,

Il

Titolo, 16, from I. M.

Watterich, Pontificum

Romanum

Vitae, Leipzig, 1862, I, 442. It seems

unlikely

to me that there was

more than one cardinal of S. Clemente called

Hugo

in the

years

1078-

1080.

28. Liber

Pontificalis, II, 296.

29.

(Robert Guiscard)

". . . aditum

namque per portam

Flammi-

neam habuit. . . . Immo

ipse

cum suis totam

regionem

illam in

qua

aecclesiae sancti Silvestri et Sancti Laurentii in Lucina site sunt

penitus

destruxit et fere a

nichilum

redegit:

dehinc ivit ad castrum sancti

Angeli,

domnum

papam

de eo abtraxit

secumque

Lateranum deduxit

omnesque

Romanos

depraedari coepit

et

expoliare, atque, quod

iniuriosum

est

nuntiare, mulieres

deshonestare, regiones illas circa

Lateranum et Coloseum

positas igne comburere"; Liber

Pontificalis,

Iu,

291.

30. Cardinal

Boson, following

the Liber ad Amicum of Bonizo de

Sutri

(c. 1086), says, ". ..

in

ingressu ipsius

civitatis

regionem

Lateranensem

usque

ad Coloseum ferro et flamma combussit

.. ."

Liber

Pontificalis, II, 368.

31.

".

. . ecclesiam sanctorum

Quatuor

Coronatorum

quae

tem-

pore Roberti Guiscardi

Salernitani principis

destructa erat . .

."; Liber

Pontificalis, II, 305. For the

20th-century restoration,

A.

Mufioz,

Il

restauro della chiesa e del chiostro dei SS.

Quattro Coronati, Rome, 1914,

esp.

4 n. 3.

32. For documentation of these two

campaigns

at

SS. Quattro

Coronati, see

Krautheimer, Corpus, Iv,

3ff.

33.

Mullooly,

Saint Clement

Pope

and

Martyr,

2nd

ed., 184ff., 255.

34. De

Rossi,

"I

monumenti," 129ff.

35.

J. Wilpert,

"Le

pitture

della basilica

primitiva

di S.

Clemente,"

Melanges d'Archeologie

et

d'Histoire,

26

(1906),

251ff.

36. D.

Kinney,

"S. Maria in Trastevere from its

founding

to

1215,"

Ph.D.

diss.,

New York

University, 1975, 195ff.

37. Liber

Pontificalis, II, 296; see also

Boyle,

"The date of consecra-

tion," 5.

38.

"Sollempnis

memoriae domno Urbano

Papa defuncto, ecclesia

quae

erat in Urbe

pastorem

sibi

dari expetit.

Ob hoc

patres

cardinales

et

episcopi, diaconi primoresque Urbi, primoscrinii

et scribae

region-

arii in ecclesia sancti Clementis

conveniunt

.. .";

Liber

Pontificalis, II,

296.

This content downloaded from 139.67.69.5 on Tue, 28 Jan 2014 20:35:12 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

BARCLAY LLOYD: BUILDING HISTORY OF S. CLEMENTE, ROME 203

claiined by

the

people

of

Rome,

the

clergy,

and the

hierarchy;

contemporaries

attributed the choice to divine

providence

and

claimed that Saint Peter had ratified

it."9

A scarlet cloak was

placed

on the new

pontiff's

shoulders and he was escorted to

the

Lateran;

there he was enthroned in the basilica and took

possession

of the

papal palace.

The

many

details of

papal

cere-

monial

given

in this account are

significant

in the

light

of the

Gregorian

Reform

party's

demands for

papal

elections free

from

imperial

interference.

Perhaps

that was

why

the election

was held in a

pro-Gregorian

cardinal's

church; perhaps

the

hierarchy

even intended to elect

Rainerius;

the

proximity

of S.

Clemente to the Lateran would ensure a swift enthronement

of the new

pope.

The

emperor

would be

presented

with a

fait

accompli

difficult to reverse.

The

description

of Paschal's election does not

say anything

specific

about the state of the church of S.

Clemente,

but it

must have been in

fairly good repair

to receive the

hierarchy,

clergy,

and

people

of Rome.

Pope

Paschal II's election was

probably

the last

noteworthy

event to take

place

in the lower

basilica.

Since Paschal II

diligently

set about

restoring

and

rebuilding

the

nearby

church of SS.

Quattro

Coronati

shortly

after he

became

pope,

it is

generally

assumed that he

was,

as Cardinal

Rainerius, responsible

for the

late-11th-century building

cam-

paign

at S. Clemente.

Further,

since four of the walls built in

that

campaign

were decorated with

murals,

it seems

likely

that

they

were set

up

some time before the church was

entirely

rebuilt. The

masonry

of these walls

suggests

a date as

early

as

the

pontificate

of

Pope Gregory

VII

(1073-1085);

Rainerius

was

appointed

titular cardinal of S. Clemente

by Gregory

shortly

after 1080. Whatever the reason for the

renovation--

the

great age

of the

basilica, Robert Guiscard's

damage

to the

Lateran and Colosseum

area,

or a natural disaster like an earth-

quake-the campaign probably

took

place

in the

period

c. 1080-c. 1099.

II. The

rebuilding of

the church

by

Cardinal Anastasius

Some time after 1099 the church of S. Clemente was en-

tirely

rebuilt on a

higher

level and to a smaller scale

by

Cardi-

nal Anastasius. Until

recently,

one of the

problems

surround-

ing

this

campaign

was that two cardinals of that name were

believed to have held the church of S. Clemente in the first

quarter

of the 12th

century. Ciacconius, Rondinini, and oth-

ers, including Junyent, ascribed the medieval

rebuilding

of the

church to the second cardinal of that

name.40 Subsequently,

Father Leonard

Boyle, O.P., was able to show that there was

only

one Anastasius, who was cardinal

presbyter

of S. Cle-

mente in the

early

12th

century.41 Shortly

after Paschal II's

election in

August

1099 the name Anastasius

appears

as cardi-

nal of the church in documents and

inscriptions:

in March

1102 he

signed

a

document;

his last

appearance

is on a

diploma

of

May 1125; by

March 1126 a certain Ubertus

began

to

sign

as titular of S. Clemente, by

which time Cardinal Anastasius

presumably

had died. What confused

Ciacconius, Rondinini,

and others was that two other names, Arnaldus and Panurius,

also

appear

as cardinals of S. Clemente in documents dated

1105 and 1108, respectively.

It has been shown, however, that

these two documents are

spurious,

as is the

designation

of the

titular of S. Clemente as "cardinal deacon" rather than "cardi-

nal

presbyter,"

the correct

title.42

Consequently,

we

may

safely

assume that there was

only

one Cardinal

Anastasius,

who was titular of S. Clemente from between 1099 and 1102

until 1125-1126.

In his

studies,

Junyent

discussed the

epigraphic

evidence for

the construction of the

upper church.43

The last dated

inscrip-

tion in the lower basilica records a burial there in 1059.44 It

provides

a terminus

post quem,

if rather an

early one,

for the

construction of the medieval church.

Two

inscriptions

refer to the

rebuilding

of S. Clemente

by

Cardinal Anastasius.

One,

carved on the back of the

episcopal

throne in the

apse,

still exists. It

proclaims:

ANASTASIUS PRESBYTER CARDINALIS HUIUS TITULI

HOC OPUS CEPIT ET

PERFECIT,

that

is,

Cardinal Anastasius

"began

and finished this work."

The "work" referred to

may

be the

rebuilding

of the

church,

its

decoration,

its

liturgical furniture,

or

just

the throne. Even

if

only

the last is

meant,

it would still

provide

a terminus ante

quem

for the

12th-century rebuilding campaign,

since the

epis-

copal

throne would

only

have been installed when the church

was

already standing.45

The other

inscription,

from the tomb

39. "'Ecce te in

pastorem

sibi dari expetit populus Urbis, te

elegit

clerus, te collaudunt

patres, denique

in te solo totius

quievit ex-

aminatio. Divinitus ista

proveniunt,

divinitus hic

congregati

in no-

mine Domini te ad summi

pontificatus apicem

et

eligimus

et confir-

mamus . . . Paschalem

papam

sanctus Petrus

eligit!'";

Liber

Pontificalis, II, 296.

40. A. Ciacconius, O.P., Vitae et Gestae Summorum

Pontificum . ..

necnon S. R. E.

Cardinalium, Rome, 1601,

365:xIv,

and 366:

xxxvIll;

P. Rondinini, De S. Clemente

papa

et

martyre

et

ejusque

basilica in urbe

Roma, Rome, 1706, 344ff.; Junyent, II Titolo, 187ff.

41.

Boyle,

"The date of consecration," 1ff.

42.

Ibid.,

2ff.

43.

Junyent,

"La basilica

superior," 252ff.; Junyent,

II Titolo,

186ff.

44.

Junyent,

"La basilica

superior," 252ff.; Junvent, II Titolo, 187.

45.

Junyent,

"La basilica

superior," 253; Junyent, II Titolo,

187.

For

papal

or

episcopal

thrones in

12th-century

churches in

Rome, see

F.

Gandolfo, "Riempiego

di sculture antiche nei troni papali

del XII

secolo," Rendiconti-Atti della

Pontificia

Accademia Romana di Archeolo-

gia,

Serie

in,

47

(1976), 203ff., esp.

207ff.

This content downloaded from 139.67.69.5 on Tue, 28 Jan 2014 20:35:12 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

204

JSAH, XLV:3, SEPTEMBER 1986

of Cardinal

Anastasius,

which was

formerly

at S.

Clemente,

no

longer exists,

but is known from a

16-century transcription

published by Rondinini

in

1706.46

De Rossi made two emen-

dations in

1870.47 Junyent published

De Rossi's version.48 It

reads:

dudum IS SANCTE PATER CLEMENS TUA TEMPLA NOVAVIT

CUIUS IN HOC TUMULO PULVIS ET UMBRA IACENT

MORIBUS EGREGIUS ET VITA PRESBYTER URBIS

FULSIT ANASTASIUS NOMINE DICTUS ERAT

VITA DECENS

STUDIUMQ. PIUM VIS RELIGIONIS

CONSPICUUM MERITIS EFFICIEBAT EUM

HUNC

QUICUMQ.

LEGIS TUMULUM MEMOR ESTO

LEGENDO

DICERE NATE DEI SUBSIDIERIS EI.49

Onofrio

Panvinio in the 16th

century

recorded

seeing

at S.

Clemente the tomb of Cardinal

Anastasius, who,

he

wrote,

had rebuilt the church from its

foundations; probably

he based

that statement on the two

inscriptions,

on the

episcopal

throne,

and on the

tomb."5

Although

the two Anastasius

inscriptions imply

that the

Cardinal

brought

the work of

rebuilding

S. Clemente to com-

pletion,

another

inscription suggests

that the

upper

church

was finished after his death

by

a man named

Petrus.5

This

inscription

was found in two

fragments

in the area of Rome

between Via Arenula and Piazza Cenci. Gatti

completed

it

and,

even if his

interpretation

is

mistaken, enough

remains of

the

original strongly

to

suggest

that Cardinal

Anastasius,

who

had

begun

to rebuild S.

Clemente,

entrusted the conclusion of

his work to Petrus. As

completed by Gatti,

it reads:

HOC PETRUS TUM[ulo cla]UDITUR

IN DOMINO

CEPIT ANASTASI[us

que ce]RNIS

TEMPLA CLEMENTIS

ET MORIENS CURA[m detuli]D HUIC OPERIS.

QUE QUIA

FINIVIT P[ost vite fjUNERA VIVIT,

CUI DUM VIVEBA[t subdit]US ORBIS ERAT.

POST MORTEM

CA[rnis dabit]UR

TIBI GLORIA CARNIS

SANCTIS IUDICIO

V[ivifica]NTE DEO.

With this

epigraphic

evidence in mind it is

important

to re-

examine the fabric of the

upper church,

to see how it relates to

the lower

basilica,

to reconstruct its

appearance

in the

early

12th

century,

and to seek evidence of more than one

building

phase.

In other

words,

one needs to determine the extent of

Cardinal Anastasius's

building campaign

and

suggest

what he

may

have left undone for Petrus to

complete.

Junyent

and Krautheimer have

explained

how the medieval

upper

church is related to its

Early

Christian

predecessor (Figs.

4, 5):52

the

apse,

still in the

west,

has a smaller

radius,

but the

length

of the

building

remains

approximately

the

same;

the

south aisle wall is built on

top

of its lower

counterpart;

the

south colonnade stands on its

Early

Christian

predecessor;

the

north

aisle

wall rests on the

Early

Christian north

colonnade;

the

upper

north colonnade stands on a new medieval founda-

tion built inside the

Early

Christian nave. The medieval

church, built c. 4.37 m above the

Early Christian basilica53-

its floor is at

roughly

the

height

of the

capitals

in the lower

church's nave colonnades-is narrower than its

predecessor

by

the width of one

aisle;

its south

aisle, following

the

Early

Christian

proportions,

is wider that the medieval north

aisle;

its nave is narrower than its lower

counterpart.

Needless to

say, in preparing

the foundations of the

upper

church,

all

remaining openings

in the lower walls and colon-

nades were blocked

(see Fig. 3);

a smaller

apse

was laid out

within

the old one

(see Fig. 4);

an

entirely

new foundation for

the north colonnade of the

upper

church was built within the

nave of the lower

basilica.54

In

addition,

a small

apsed chapel

was

planned

north of the

12th-century apse; and,

in the south-

ern corner of the old

narthex,

a vault was constructed.

The

12th-century

foundations are

mostly

built of a kind of

medieval

opus caementicium,

with

irregular

blocks of stone in

fairly straight rows;

sometimes this has above it a few courses

of

opus

listatum

(blocks

of tufa

alternating

with

two, three,

or

four rows of

bricks) (Fig. 6).

In the old south aisle wall all the

remaining openings

were closed in medieval

opus

listatum of

this

type, except

for the westernmost

one,

which was blocked

with opus caementicium (see Fig. 2).

In the walls

certainly per-

taining

to this

rebuilding

of the church the mortarbeds are not

46.

Rondinini,

De S.

Clemente,

321. Rondinini took his version of

the

inscription

from Ciacconius.

47. He added "dudum" at the

beginning

and

changed

"NOTAVIT" at the end of the first line to

"NOVAVIT";

De

Rossi,

"Dati

cronologici," 141ff.

48.

Junyent,

"La basilica

superior," 253; Junyent, II Titolo,

188.

49. The

inscription

refers to the church

("TUA TEMPLA")

in the

plural.

This

expression

occurs

frequently

in

Early

Christian

inscrip-

tions as a

plurale

tantum

(cf.

E.

Diehl, Inscriptiones

Latinae Christianae

Veteres, Berlin, 1925-1931, index, p. 412)

and should be taken to refer

here to a

single church, the

upper

medieval basilica.

50.

(Cardinal Anastasius)

". . . huius

sepulchrum

adhuc extat in

basilica S. Clementis, quam

a fundamentis

refecit";

O.

Panvinio,

Epitome Pontificum

Romanorum a S. Petro

usque

ad Paulum

III, Venice,

1577,

82.

51. G. Gatti,

"Di un nuovo monumento

epigrafico

relativo alla

basilica di S. Clemente,"

Bullettino della Commissione

archeologico

comunale,

XVII

(1889), 467ff.; Junyent,

"La basilica

superior," 254;

Junyent, II Titolo,

188. Gatti

suggested

that the "Petrus" in the in-

scription

was Cardinal Petrus Pisanus.

52.

Junyent, II Titolo, 190ff.; Krautheimer, Corpus, I, 117ff.

53. This measurement was taken

by myself

and

J.

M. Blake in the

narthex of the lower

church;

the nave of the

Early

Christian

basilica

is

now 4.50

m,

the aisles 4.75-4.80 m below the

pavement

of the

upper

church.

54. For

these

medieval walls built in the lower church in

prepara-

tion for the

rebuilding,

see the fine

survey plan published by

Guido-

baldi. "I1 complesso archeologico," Tav. v.

This content downloaded from 139.67.69.5 on Tue, 28 Jan 2014 20:35:12 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

BARCLAY LLOYD: BUILDING HISTORY OF S. CLEMENTE, ROME 205

marked

withfalsa

cortina

pointing;

as noted

above, this charac-

teristic seems to

distinguish

them from the earlier late-11th-

century repairs

to the

Early

Christian basilica. The vault in the

southernmost

bay

of the lower narthex bears the

imprint

of

woven

matting,

a common feature of

vaulting

in Rome in the

12th and 13th

centuries, when,

apparently,

straw mats were

placed

on the

centering

when vaults were

constructed.5

Finally,

the old basilica was filled with rubble and dirt and

eventually

a new

"Cosmatesque" opus

sectile

pavement

was

laid on

top.56 Clearly,

the

Early

Christian church determined

many

features of the new

plan (Figs. 7, 8): orientation,

length,

basilical

layout. Similarly,

in the new construction earlier

walls were

readily utilized,

as foundations and

higher up.

The

north wall of the medieval church is

Early

Christian to a

height

of c. 8.61 m above the medieval

pavement (see Fig. 5,

wall

4);

the

facade

wall of the lower

church, too,

was

incorpo-

rated in the medieval

fabric."7

Yet,

the medieval

plan

also

differed from its

Early

Christian

predecessor:

the new church

was

narrower,

in the nave and north aisle

(see Figs. 4, 5);

the

radius of the

apse

was

smaller;

the colonnades were inter-

rupted by piers (Fig. 7).

It is

clear, too,

that the medieval

plan

was modified

during

construction: the

apsed chapel

north of

the main

apse

was not built

(Fig. 8, A);

the vault in the lower

narthex

may

have been

part

of an unfinished

project, perhaps

55. This

example

at S.

Clemente, c. 1099-c.

1125, is the earliest

instance of this

building technique

known to me. Similar vaults with

the

imprint

of woven

matting

occur in the cellars of the S. Clemente

canonry, probably

built at the same

time;

in the conventual

buildings

beside S. Maria in Cosmedin

(the

church was restructured in 1123 and

the vaulted

parts

of the

canonry

in successive

phases

in the 12th and

13th

centuries;

G. B.

Giovenale,

La basilica di S. Maria in

Cosmedin,

Rome, 1927, 406ff., surveyed

these

buildings,

but in

my opinion

his

interpretation

of them needs

revision);

in the

monastery

of SS.

Vincenzo e Anastasio alle Tre

Fontane,

in

parts

of the

building prob-

ably

erected

shortly

after 1140 and before 1220

(I

am at

present prepar-

ing

an architectural

history

of this

monastery, surveyed by myself

and

J.

M. Blake in

1983);

in the cloister and cellars of the

monastery

at

S. Lorenzo

f.l.m.,

1187-1191

(Krautheimer, Corpus, II,

13ff.; the

building

was

surveyed by

Mr. Blake and

myself

in

1984);

in the bell

tower at S. Sabina

(examined during

a

survey

of that monastic com-

plex

in 1982: from its

masonry

I would date this tower to the 12th not

the 10th

century; also,

I believe it was built as a

campanile,

not as a

defensive

tower, cf. F.

Darsy, O. P., Santa Sabina [Le Chiese di Roma

Illustrate, 63-64], Rome, 1961, 25, 30, 115);

in two bell towers in the

transept

of the Lateran basilica

(the transept

was built in

1291, the

towers

presumably

a little

later, since

they

stand

against

its

pre-exist-

ing walls; Krautheimer,

Corpus, v, 12, 19ff.);

and an undated instance

in the medieval

wings

of the Vatican Palace

(examined

in

1984).

Thus

the use of woven

matting

in the construction of vaults seems to have

been common in Rome from c. 1099-c. 1300.

56. For the

pavement

of the medieval

church,

D.

Glass, Studies in

Cosmatesque Pavements,

Oxford

(BAR S82), 1980, 83ff. One of the

problems

in

excavating

the lower church was

evidently

the lack of

support given

to the medieval

pavement,

once the rubble and dirt

were removed. The

upper

church had to be reinforced with 19th-

century piers

and vaults.

57.

Krautheimer,

Corpus, I, 132, 130.

o

0

0

a

SD

~O

I 1

0D

'Q Dg

Fig.

4. S.

Clemente, plan

of

upper

church related to

plan

of lower

basilica

(from Junyent, II Titolo, Fig. 54).

This content downloaded from 139.67.69.5 on Tue, 28 Jan 2014 20:35:12 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

206

JSAH, XLV:3, SEPTEMBER 1986

%c

South

1isle 14.46 N

e

!

e oi l

l

T

i ll

R26 o

ra

a

ic

I2

I.we'r

Churc.h

M1E Brickwork, late

fourth

centurv

South

aisle Nave

VIE -Opus

eacmenticium-,

twelfth

Na Norh a.isle1century foundations Tufa fill

X Brickwork. twelfth

century

XIIIM Rubbler masonry.

fifteenth centurv

S. CLEMENTE

x iIlh

Lower

and upper churches

and conventual Iniklings

SECTION AA'

Fig.

5. S. Clemente,

section

through upper

and lower basilicas and conventual buildings (Barclay Lloyd and Blake survey, Section AA1).

. ".

no,

.. .....

.. .

. - ..

W.. 1: 1

... - . IM.,

Or. eAl

ad

.:b4

.

1z,

dw?

Wla W.

.;9"w

C A?,.:, N;'

Ow

wr?

Fig.

6.

Rome, S.

Clemente, upper church,

c. 1099-c. 1125, founda-

tions of north aisle in north colonnade of lower basilica

(Barclay

Lloyd).

for a bell

tower,

later to be built in the eastern corner of the

north aisle

(Fig. 8, B).

Despite

the addition of later

chapels

and an

early-18th-cen-

tury

renovation of the

interior,58

the medieval

upper

church in

large part

survives

(Figs. 7, 9, 10).

It is a

basilica, facing east,

with a

nave,

two

aisles,

and an

apse;

in front is an

atrium,

whose eastern

wing

forms a kind of double-storied

gatehouse

(Fig. 11),

entered

through

a

porch

or

prothyron (Fig. 12).

The

church is 36.51 m

long

and 21.69 m

wide;

the south aisle is

5.73 m

wide,

the north aisle 3.74 m

wide;

the diameter of the

apse

is 8.46 m. The nave is

separated

from the aisles

by

colon-

nades

interrupted by

central

piers;

in each colonnade four col-

umns stand between the central

pier

and the

tongue piers

at

either end of the nave.59 The columns are 0.60 m in

diameter;

the intercolumniations are 2.60-2.65

m;

the

tongue piers

are

1.45-1.49 m and the central

piers

2.555 m

long.

The basilica's

main door is in its eastern facade.

A doorframe in the east wall

58. The

chapels

of Saint Catherine, the

Holy Rosary,

Saint

John

the

Baptist,

Saint

Cyril,

and Saint Dominic are all

postmedieval;

the

church was restored in 1702-1715

by

Carlo Stefano Fontana, at the

behest of

Pope

Clement XI

(1700-1721); Junyent,

II

Titolo,

218ff.

59. The easternmost columns and

tongue piers

are

clearly visible,

despite

the walls built to

separate

the

chapels

of Saint Catherine and

Saint Dominic from the nave.

This content downloaded from 139.67.69.5 on Tue, 28 Jan 2014 20:35:12 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Via dei Normanni

Roaryr

a hie I

m

IIIrnl

Ra

Pmbytery

E C1. r~r6rs II I i tar1.195I

r.

S

S-

Garden I

2

C

10 L C

ri

E

Choir hape

Q3

11-

0~~4 fB 12F(5

e2.o0

WING C

(4)

WIDNG(30)

D2(6)

(0

0.225 (13S) Coffee Room

O

0.225

O 0.00

20

(2) (3)

11 (28)IM

15?

1

Storeom 1

~A'

A

O

6 14

Shop 000

(00) (1)

(3

D0um: 0.00 0oi 0lom Refectory

Kitchen

0., 2.02 2.02

S7 150

Sm

(29)

HIT, WING A

(34)

,

Catherine's

Chapel 8

LD

st. ~Refectory l

SI.DominicVestibuleD

Ch~pcl2.02

(16)

[Ex aviti

(8)

Narthex

x

(7)

Celal r

aT i07) -1.00

21 22 23 24

25

31 ..

)(32)

C.__

I

34a. 2.31

0336GardardeIl

218

((26

028

ca.4 5 1

2..51,

355

(2)

22

36

3lll Tufa fillr

I

Hri,'k....k. A,,,i ....

IV

Hri,'k....k.sixth .........y

11

()l ...

listat

........lft,, c......y

XII

OIu ........in.....um fatced ,ith Ibrik,'

seq.on halt thirAeenth .cetury

II

m

Brikwrk

...k

tout

....h

r fifth

.........y

V

B- rik....k.ni,,th ........y ....

An

ci

....

X

Bri,'kwork,

....lfth

.......y XIV

Rubble

........y. si........h " ........

(?!) Ill

Blri.k-work.

Int

....th ...

I

.......

\!l

Brickwrkr w1ih

a.

.....

ia

Ioi,,ting,

XI

Bri,-kwork.

first

haltf

thirt

....th c- .....y

S. CLEMENTE

Medieval Church and Conventual Buildings

PLAN I

Fig.

7. S. Clemente, upper

church and conventual

buildings, plan (Barclay Lloyd

and Blake

survey, plan I).

This content downloaded from 139.67.69.5 on Tue, 28 Jan 2014 20:35:12 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

208

JSAH, XLV:3, SEPTEMBER 1986

I

(23)

II

I L

t

i

S

'

-,

planned only

SCardinal

Anastasius

uncertain or later

\ N

I 1)

-I

(5)

II

0--I

/

0

i17,

Ii

'

L--

------

Fig.

8. S. Clemente, upper church, plan

and reconstruction

(Barclay Lloyd).

This content downloaded from 139.67.69.5 on Tue, 28 Jan 2014 20:35:12 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

BARCLAY LLOYD: BUILDING HISTORY OF S. CLEMENTE, ROME 209

....................

e'll

:i

iT

. ..

.AN

.............

NX . ...

cr,

51-

.-.- ;Ml

Fig.

9. S.

Clemente, upper church, view of interior

today (Barclay

Lloyd).

of St. Catherine's

chapel,

with two

stylized peacocks

carved

on its

lintel, may

survive from a

subsidiary

side entrance to the

church,

which was later blocked.60

All

rising

walls of the medieval

church, except

the north

aisle

wall,

which is

Early Christian,

and

parts

of the

facade,

which I have been unable to

examine,

are built of the same

kind of

masonry (see Figs. 5, 7).61 This is

good-quality

medi-

fil

i i ::ii:

:iii::! !!! !!!!!! !iil

:

i ii i l so.

iii-: iiiiii!

iiiii li!i!~i~

ii i:;iiiiiiiiil

:i -ii!!!!i~!i

%-

i -i

..

i~iiiiiiiii

Fig.

10.

Ciampini,

interior view of S.

Clemente, 1690

(G.

Ciam-

pini,

Vetera

monimenta, Rome, I, 1690, Tab.

viii).

eval

brickwork,

with re-used bricks 12, 151/2, 19, 221/2 cm

long, neatly

laid in

straight

rows with mortarbeds 2 /2-3 /2 cm

high.

The mortar is

finely

textured and on interior walls it still

has a

pale gray finish;

there is no

falsa

cortina

pointing, except

occasionally

between voussoirs. A modulus of five rows of

bricks and five mortarbeds measures

28/2, 29, 30, 31, or 31 /2

cm;

it is

usually

close to 30 cm.

In elevation the church has a

steep

and narrow nave. The

colonnades

carry

arcades and

high clerestory walls, now

pierced by

three

rectangular

windows on either

side,

but traces

of earlier blocked windows are visible on the exterior

(Fig.

13).

The columns all have ancient Roman

shafts,

fluted or

unfluted,

and are of different materials: Proconnesian marble,

cipollino, granite,

and

gray-veined

marble.

(Their disposition

is charted in Table

I,

where the numbers

correspond

to those

on our

survey plan, Fig. 7.) Despite

the

variety

in

type

and

material,

it seems that the columns were

placed

in careful

order:

in five cases out of

eight,

identical shafts match each

other across the nave

and,

in the

remaining three, columns of

60.

Junyent

believed there were three medieval

doorways

into the

church in the

fagade

wall,

one

giving

access to the nave and one to

each aisle

(Junyent,

II

Titolo,

196 and

Fig. 55),

but I have found

only

the central one into the nave and

possibly

a second one in the south

aisle in the east wall of the

chapel

of Saint Catherine. At

present

the

latter

cuts into the fresco of the

Crucifixion

on that

wall,

indicating

that it was blocked before the fresco was

painted

in the 15th

century,

or that it was

opened

after the fresco had been

made; the

jambs

of the

doorframe at

present begin fairly high up.

Not

enough

is visible of the

wall at this

point

to

clarify

whether this doorframe

belongs

to the

original plan

of the medieval church. The

present

entrance in the south

aisle was

opened

in

1716;

it

replaced

one farther

west, opened

in 1590

by

Cardinal

Vincenzo Laureo; Junyent,

II

Titolo, 21, 221.

61. The

fagade

is

mostly

covered with

plaster.

So is the south aisle

wall,

but I was able to examine the

masonry

of that

during

the recent

restoration

campaign,

when the

plaster

was

temporarily

removed in

January

1984.

This content downloaded from 139.67.69.5 on Tue, 28 Jan 2014 20:35:12 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

210

JSAH, XLV:3, SEPTEMBER 1986

4,

4ii li:;

-g?4ia.i: i?!! ;di?-

:::-:::;::::i

;

?:ii~

Fig. 11.

S.

Clemente, upper church, gatehouse

from west

(Barclay

Lloyd).

the same material or color are

paired.62

Smooth columns of

white, gray,

or

greenish

marble stand east of the central

piers;

west of the

piers

smooth

granite

shafts alternate with fluted

columns of white Proconnesian

marble,

concentrating

the

more

precious

columns close to the

high

altar. Almost all the

shafts stand on ancient

bases,

Ionic or

Attic;

four are now

covered

by

the

pavement,

one is medieval.

Capitals

are now

all

Ionic,

molded in

18th-century

stucco. Prior to the 1715

restoration the

capitals

were described as "re-used and of dif-

ferent orders."" Since most are

low,

it is

likely

that most were

Ionic,

of ancient or medieval

manufacture;

the two columns

closest the

high

altar have

higher capitals

than the

rest-per-

haps they

were Corinthian or

composite capitals

cut down to

the

required height.64

The

piers

in the center of the colonnades were

formerly

believed to have been built to reinforce

columns,65

as in the

south colonnade in the lower basilica.

They must, however,

be

part

of the

original plan

of the church and were

fairly

common in Roman church

design

in the late 11th and

early

iii-iili-:i-iii-iii-:-i:-i!lii--i:::::i ---i:-:_-:--::-

ii