Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Institutional Investors and Corporate Governance in India

Institutional Investors and Corporate Governance in India

Uploaded by

Anirudh SrikantCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5825)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1093)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (852)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (903)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (541)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (349)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (823)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (403)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- Infosys (A) Strategic HRM - Group1 - Section BDocument5 pagesInfosys (A) Strategic HRM - Group1 - Section BAnirudh SrikantNo ratings yet

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Studi Kasus 1 SIPI 2020Document3 pagesStudi Kasus 1 SIPI 2020Rika YunitaNo ratings yet

- Agreement of Spouses Revoking Premarital AgreementDocument3 pagesAgreement of Spouses Revoking Premarital Agreementpeaser0712No ratings yet

- Tax RemediesDocument16 pagesTax RemediesJoshua Catalla Mabilin100% (1)

- Chicago-West Coast Pricing Decision: Major ChallengesDocument2 pagesChicago-West Coast Pricing Decision: Major ChallengesAnirudh SrikantNo ratings yet

- WebinarDocument13 pagesWebinarAnirudh SrikantNo ratings yet

- CalculationDocument2 pagesCalculationAnirudh SrikantNo ratings yet

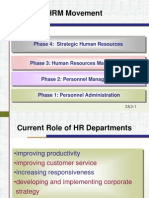

- HRM Movement: Phase 4: Strategic Human ResourcesDocument6 pagesHRM Movement: Phase 4: Strategic Human ResourcesAnirudh SrikantNo ratings yet

- Valuation ProcessDocument3 pagesValuation ProcessVernon BacangNo ratings yet

- Measuring The Readiness of Navotas Polytechnic College For SLO AdoptionDocument5 pagesMeasuring The Readiness of Navotas Polytechnic College For SLO AdoptionMarco MedurandaNo ratings yet

- 11-03-2012 EditionDocument32 pages11-03-2012 EditionSan Mateo Daily JournalNo ratings yet

- Poultry Financial AspectDocument7 pagesPoultry Financial AspectRuby Riza De La Cruz OronosNo ratings yet

- Basics of Accounting in Small Business NewDocument50 pagesBasics of Accounting in Small Business NewMohammed Awwal NdayakoNo ratings yet

- Full Ebook of International Relations As A Discipline in Thailand 1St Edition Chaninthira Na Thalang Online PDF All ChapterDocument69 pagesFull Ebook of International Relations As A Discipline in Thailand 1St Edition Chaninthira Na Thalang Online PDF All Chapterjackserio833558100% (6)

- Credit Transactions SyllabusDocument8 pagesCredit Transactions SyllabusPJANo ratings yet

- Metro Lemery Medical Center: "Committed To Excellence in Total Healthcare"Document2 pagesMetro Lemery Medical Center: "Committed To Excellence in Total Healthcare"Armin Tordecilla MercadoNo ratings yet

- G.R. Nos. 121576-78 June 16, 2000 BANCO DO BRASIL, Petitioner, The Court of Appeals, Hon. Arsenio M. Gonong, and Cesar S. Urbino, SR., RespondentsDocument1 pageG.R. Nos. 121576-78 June 16, 2000 BANCO DO BRASIL, Petitioner, The Court of Appeals, Hon. Arsenio M. Gonong, and Cesar S. Urbino, SR., RespondentsImelda Silvania MarianoNo ratings yet

- Jesse Owens Oneonone Activities ReadingDocument3 pagesJesse Owens Oneonone Activities Readingririn everynNo ratings yet

- Style Only: 42 Scientific American, October 2014Document6 pagesStyle Only: 42 Scientific American, October 2014Gabriel MirandaNo ratings yet

- Social Studies Chapter 8Document2 pagesSocial Studies Chapter 8Arooj BaigNo ratings yet

- Eoibd EF4e - Adv - Quicktest - 06Document4 pagesEoibd EF4e - Adv - Quicktest - 06Mym Madrid MymNo ratings yet

- Ielts 6.5 2021Document290 pagesIelts 6.5 2021Miyuki EjiriNo ratings yet

- De Guzman V ChicoDocument3 pagesDe Guzman V ChicoChelle BelenzoNo ratings yet

- Rural RetailingDocument10 pagesRural Retailingunicorn2adNo ratings yet

- Bock, de L.L.M. 4179781, BA Thesis 2017Document29 pagesBock, de L.L.M. 4179781, BA Thesis 2017DutraNo ratings yet

- Nevid CH09 TBDocument62 pagesNevid CH09 TBAngela MarisNo ratings yet

- LSG OfficersDocument2 pagesLSG OfficersChanChi Domocmat LaresNo ratings yet

- It Sa 22 Hallenplan Besucher Halle 7ADocument1 pageIt Sa 22 Hallenplan Besucher Halle 7AslwnyrsmidNo ratings yet

- Intelligence and IQ: Landmark Issues and Great DebatesDocument7 pagesIntelligence and IQ: Landmark Issues and Great DebatesRaduNo ratings yet

- History of KarateDocument5 pagesHistory of KaratekyleNo ratings yet

- History of Ancient Philosophy - WindelbandDocument422 pagesHistory of Ancient Philosophy - WindelbandAtreyu Siddhartha100% (3)

- Victory Liner, Inc. vs. GammadDocument2 pagesVictory Liner, Inc. vs. GammadJakeDanduan50% (2)

- chiến lược marketing cho panasonicDocument19 pageschiến lược marketing cho panasonicVu Tien ThanhNo ratings yet

- DLP (Judy Ann de Vera)Document13 pagesDLP (Judy Ann de Vera)Judy Ann De VeraNo ratings yet

- Skygazers On The BeachDocument1 pageSkygazers On The BeachpinocanaveseNo ratings yet

Institutional Investors and Corporate Governance in India

Institutional Investors and Corporate Governance in India

Uploaded by

Anirudh SrikantCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Institutional Investors and Corporate Governance in India

Institutional Investors and Corporate Governance in India

Uploaded by

Anirudh SrikantCopyright:

Available Formats

Institutional Investors and Corporate Governance in India

Abstract

Using nineteen measures of corporate governance, we develop a corporate governance index

in this paper. We find that this corporate governance index is positively associated with

financial performance measures like Tobins Q and industry-adjusted excess stock returns.

We find that the development financial institutions have lent money to companies with better

corporate governance measures. We also find that mutual funds have invested money in

companies with better corporate governance record. Using a simultaneous equation approach

we find that this positive association is both because the mutual funds (development financial

institutions) have invested (lent money) in companies with good governance records, and also

because their investment has caused the financial performance of the companies to improve.

Corporate governance in india

Corporate governance in India gained prominence in the wake of liberalization during the

1990s and was introduced, by the industry association Confederation of Indian Industry (CII),

as a voluntary measure to be adopted by Indian companies. It soon acquired a mandatory

status in early 2000s through the introduction of Clause 49 of the Listing Agreement, as all

companies (of a certain size) listed on stock exchanges were required to comply with these

norms. In late 2009, the Ministry of Corporate Affairs has released a set of voluntary

guidelines for corporate governance, which address a myriad corporate governance issues.

These voluntary guidelines mark a reversal of the earlier approach, signifying the preference

to revert to a voluntary approach as opposed to the more mandatory approach prevalent in the

form of Clause 49. However in a parallel process, key corporate governance norms are

currently being consolidated into an amendment to the Companies Act, 1956 and once the

Companies Bill,2011 is approved the corporate governance reforms in India would have

completed two full cycles - moving from the voluntary to the mandatory and then to the

voluntary and now back to the mandatory approach.

The Anglo-Saxon model of governance, on which the corporate governance framework

introduced in India is primarily based on, has certain limitations in terms of its applicability

in the Indian environment. For instance, the central governance issue in the US or UK is

essentially that of disciplining management that has ceased to be effectively accountable to

the owners who are dispersed shareholders.

However, in contrast to these countries, the main issue of corporate governance in India is

that of disciplining the dominant shareholder, who is the principal block-holder, and of

protecting the interests of the minority shareholders and other stakeholders.

This issue and the complexity arising from the application of alien corporate governance

model in the Indian corporate and business environment is further compounded by the weak

enforcement of corporate governance regulations through the Indian legal system.

Furthermore, given that corporate governance is essentially a soft issue, whose essence

cannot be captured by quantitative and structural factors alone, one of the challenges of

making corporate governance norms mandatory is the need to differentiate between form and

content; for instance, how do we determine whether companies actually internalize the

desired governance norms or whether they look at governance as a check-the-box exercise to

be observed more in letter than in spirit.

Currently, corporate governance reforms in India are at a crossroads; while corporate

governance codes have been drafted with a deep understanding of the governance standards

around the world, there is still a need to focus on developing more appropriate solutions that

would evolve from within and therefore address the India-specific challenges more

efficiently.

Corporate governance is perhaps one of the most important differentiators of a business that

has impact on the profitability, growth and even sustainability of business. It is a multi-level

and multi-tiered process that is distilled from an organizations culture, its policies, values

and ethics, especially of the people running the business and the way it deals with various

stakeholders.

Creating value that is not only profitable to the business but sustainable in the long-term

interests of all stakeholders necessarily means that businesses have to runand be seen to be

runwith a high degree of ethical conduct and good governance where compliance is not

only in letter but also in spirit.

Regulatory Framework for Corporate Governance in India

As a part of the process of economic liberalization in India, and the move toward further

development of Indias capital markets, the Central Government established regulatory

control over the stock markets through the formation of the SEBI. Originally established as

an advisory body in 1988, SEBI was granted the authority to regulate the securities market

under the Securities and Exchange Board of India Act of 1992 (SEBI Act).

Public listed companies in India are governed by a multiple regulatory structure. The

Companies Act is administered by the Ministry of Corporate Affairs (MCA) and is currently

enforced by the Company Law Board (CLB). That is, the MCA, SEBI, and the stock

exchanges share jurisdiction over listed companies, with the MCA being the primary

government body charged with administering the Companies Act of 1956, while SEBI has

served as the securities market regulator since 1992.

SEBI serves as a market-oriented independent entity to regulate the securities market akin to

the role of the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) in the United States. The stated

purpose of the agency is to protect the interests of investors in securities and to promote the

development of, and to regulate, the securities market. The realm of SEBIs statutory

authority has also been the subject of extensive debate and some authors have raised doubts

as to whether SEBI can make regulations in respect of matters that fall within the jurisdiction

of the Department of Company Affairs. SEBIs authority for carrying out its regulatory

responsibilities has not always been clear and when Indian financial markets experienced

massive share price rigging frauds in the early 1990s, it was found that SEBI did not have

sufficient statutory power to carry out a full investigation of the frauds. Accordingly, the

SEBI Act was amended in order to grant it sufficient powers with respect to inspection,

investigation, and enforcement, in line with the powers granted to the SEC in the United

States.

A contentious aspect of SEBIs power concerns its authority to make rules and regulations.

Unlike in the United States, where the SEC can point to the Sarbanes-Oxley Act, which

specifically confers upon it the authority to prescribe rules to implement governance

legislation, SEBI, on the other hand, cannot point to a similar piece of legislation to support

the imposition of the same requirements on Indian companies through Clause. Instead SEBI

can look to the basics of its own purpose, as given in the SEBI Act, wherein it is granted the

authority to specify, by regulations, the matters relating to issue of capital, transfer of

securities and other matters incidental thereto . . . and the manner in which such matters shall

be disclosed by the companies. In addition, SEBI is granted the broad authority to specify

the requirements for listing and transfer of securities and other matters incidental thereto.

Recognizing that a problem arising from an overlap of jurisdictions between the SEBI and

MCA does exist, the Standing Committee, in its final report, has recommended that while

providing for minimum benchmarks, the Companies Bill should allow sectoral regulators like

SEBI to exercise their designated jurisdiction through a more detailed regulatory regime, to

be decided by them according to circumstances. Referring to a similar case of jurisdictional

overlap between the RBI and the MCA, the Committee has suggested that it needs to be

appropriately articulated in the Bill that the Companies Act will prevail only if the Special

Act is silent on any aspect. Further the Committee suggested that if both are silent, requisite

provisions can be included in the Special Act itself and that the status quo in this regard may,

therefore, be maintained and the same may be suitably clarified in the Bill. This, in the

Committees view, would ensure that there is no jurisdictional overlap or conflict in the

governing statute or rules framed there under.

Enforcement of Corporate Governance Norms

The issue of enforcement of Corporate Governance norms also needs to be seen in the

broader context of the substantial delay in the delivery of justice by the Indian legal system

on account of the significant number of cases pending in the Indian courts. A research paper

by PRS Legislative Research36 places the number of pending cases in courts in India, as of

July 2009, as 53,000 pending with the Supreme Court, 4 million with various High Courts,

and 27 million with various lower courts. This signifies an increase of 139 per cent for the

Supreme Court, 46 per cent for the High Courts and 32 per cent for the lower courts, from the

pending number of cases in each of them in January 2000. Furthermore, in 2003, 25 per cent

of the pending cases with High Courts had remained unresolved for more than ten years and

in 2006, 70 per cent of all prisoners in Indian jails were under trials. Since fresh cases

outnumber those being resolved, there is obviously a shortfall in the delivery of justice, and a

consequent increase in the number of pending cases. In addition, the weight of the backlog of

older cases creeps upward every year. This backlog in the Indian judicial system raises

pertinent questions as to whether the current regulatory framework in India, as enacted, is

adequate to enable shareholders to recover their just dues. This concern is also articulated in

the recent pleadings (filed in January 2010) in the United States District Court, Southern

District of New York, on the matter relating to the fraud in the erstwhile Satyam Computer

Services,38 wherein US-based investors were seeking damages from defendants that

included, among others, Satyam and its auditors, PricewaterhouseCoopers (PwC) and has

thrown up some very interesting and relevant issues. This case was filed on behalf of

investors who had purchased or otherwise acquired Satyams American Depository Shares

(ADS) listed on the New York Stock Exchange and investors, residing in the United States,

who purchased or otherwise acquired Satyam common stock on the National Stock Exchange

of India or the Bombay Stock Exchange. In their pleadings, the plaintiffs submitted

declarations of two prominent Indian securities law experts: Sandeep Parekh, former

Executive Director of SEBI, and Professor Vikramaditya Khanna of the University of

Michigan Law School, a leading expert in the United States on the Indian legal system, who

filed individual affidavits in which they detailed very cogent and compelling reasons as to

why Indian courts cannot redress the harm done to the Class plaintiffs and why India itself

does not provide a viable alternative forum for settling the claims of Class members.

In their depositions, among other things, Sandeep Parekh and Vikramaditya Khanna have

explained that:

The substantive laws of India provide no means of individual or class recovery for private

investors in securities fraud matters because the civil courts in India are barred from hearing

such cases where, as here, SEBI is empowered to act;

Even if it did provide a substantive means of recovery, Indian law provides no viable class

action mechanism under which investors claims can be litigated; and

Indian law does not recognize the fraud-on-the-market presumption of reliance in private

civil actions, so that, even if both a substantive means of recovery and a viable class action

mechanism existed under Indian law, investors would still be required to demonstrate

individual reliance, thus effectively depriving the vast majority of Class members of any

prospect of relief.

Khanna stated in his declaration43 that The lengthy delays in the Indian Judicial System

would leave plaintiff shareholders with effectively no recovery even assuming, arguendo;

there might be a potential cause of action.

Key Issues in Corporate Governance in India Managing the Dominant

Shareholder(s) and the Promoter(s)

The primary difference between corporate governance enforcement problems in India and

most western economies (on whose codes the Indian code is largely modelled) is that the

entire corporate governance approach hinges on disciplining the management and making

them more accountable. The agency gap in western economies represents the gap between

the interests of management and dispersed shareholders and corporate governance norms are

aimed at reducing this gap. However, in India the problemsince the inception of joint-stock

companiesis the stranglehold of the dominant or principal shareholder(s) who monopolize

the majority of the companys resources to serve their own needs. That is, the agency gap is

actually between majority shareholders and other stakeholders. Secondly, much of global

corporate governance norms focus on boards and their committees, independent directors and

managing CEO succession. In the Indian business culture, boards are not as empowered as in

several western economies and since the board is subordinate to the shareholders, the will of

the majority shareholders prevails.

Therefore, most corporate governance abuses in India arise due to conflict between the

majority and minority shareholders. This applies across the spectrum of Indian companies

with dominant shareholdersPSUs (with government as the dominant shareholder),

multinational companies (where the parent company is the dominant shareholder) and private

sector family-owned companies and business groups.

In public sector units (PSUs), members of the board and the Chairman are usually appointed

by the concerned ministry and very often PSUs are led by bureaucrats rather than

professional managers. Several strategic decisions are taken at a ministerial level which may

include political considerations of business decisions as well. (The recent case of the PSU oil

companies not being allowed to increase the price of oil products in line with the changes in

the international crude prices is an example of how the dominant shareholder, the Indian

Government, uses its dominance to force decisions that are not always linked to business

interests.) Therefore, PSU boards can rarely act in the manner of an empowered board as

envisaged in corporate governance codes.

This makes several provisions of corporate governance codes merely a compliance

exercise.

Multinational companies (MNCs) in India are perceived to have a better record of corporate

governance compliance in its prescribed form. However, in the ultimate analysis, it is the writ

of the large shareholder (the parent company) which runs the Indian unit that holds sway,

even if it is at variance with the wishes of the minority shareholders. Moreover, the

compliance and other functions in an MNC is always geared towards laws applicable to the

parent company and compliance with local laws is usually left to the managers of the

subsidiary who may not be empowered for such a role.

Family businesses and business groups as a category are perhaps the most complex for

analysing corporate governance abuses that take place. The position as regards family

domination of Indian businesses has not changed; on the contrary, over the years, families

have become progressively more entrenched in the Indian business milieu. As per a recent

study by the global financial major Credit Suisse, India ranks higher than most Asian

economies in terms of the number of family businesses and the market capitalization of

Indian family businesses as a share of the nominal gross domestic product (GDP) has risen

from 9 per cent in 2001 to 46 per cent in 2010. This survey, which also covered China, South

Korea, Taiwan, Singapore, Thailand, Hong Kong, Indonesia, Malaysia and the Philippines,

contends that India, with a 67 per cent share of family businesses, ranks first among the ten

Asian countries studied. Furthermore, 663 of the 983 listed Indian companies are family

businesses and account for half of the total corporate hiring and are concentrated in the

consumer discretionary, consumer staples and consumer healthcare sectors.

In addition to the corporate governance issues arising from the dominant family holding in

the Indian business companies, there exists an additional complexity on account of the

promoter control in Indian companies. Promoters (who may not be holding is not to be

included in the definition of the Promoter. Indian law and regulation require that controlling

shares) usually exercise significant influence on matters involving their companies, even

though such companies are listed on stock exchanges and hence have public shareholders.

Promoters may be in control over the resources of the company even though they may

not be the majority shareholders and, because of their position, have superior information

about the affairs of the company than that accessible to non-promoters. As a corollary, in an

organization, promoters and non-promoters constitute two distinct groups that may have

diverse interests.

The Satyam episode illustrated a scenario wherein a company with minimal promoter

shareholding could still be subject to considerable influence by its promoters, thereby

requiring a resolution of the agency problem between the controlling shareholders and the

minority shareholders, even though such problems were not normally expected to arise at the

low shareholding levels of the managing group. On 7 January 2009, when the Chairman of

Satyam Computer Services, B. Ramalinga Raju, admitted that there had been a systematic

inflation of cash on the companys balance sheet over a period of some seven years,

amounting to almost $1.5 billion, the Raju family, who were the promoters of Satyam, held

only about 5 per cent of the shares.

A company with 5 per cent promoter shareholding will usually be considered as belonging to

the outsider model in terms of diffused shareholding, and hence would require the correction

of agency problems between shareholders and managers. However, despite the gradual

decrease in the percentage holdings of the controlling shareholders, the concept of promoter

under Indian regulations made the distinction between an insider-type company and an

outsider-type company somewhat hazy in this context, and the Raju family, as promoters,

continued to wield significant powers in the management of the company despite a drastic

drop in their shareholdings over the preceding few years. Furthermore, at Satyam, the

diffused nature of the remaining shareholding of the company helped the promoter group to

consolidate and exercise power that was disproportionate to their voting rights; while the

institutional shareholders collectively held a total of 60 per cent shares as of 31 December

2008 in Satyam, the highest individual shareholding of an institutional shareholder was

only.76 per cent. Shah believes that companies wherein controlling shareholders hold limited

takes could be particularly vulnerable to corporate governance failures and adds that

promoters who are in the twilight zone of control, that is, where they hold shares less than

those required to comfortably exercise control over the company, have a perverse incentive to

keep the corporate performance and stock price of the company at high levels so as to thwart

any attempted takeover of the company. The Satyam case clearly demonstrates the inability

of the existing corporate governance norms in India to deal with corporate governance

failures in familycontrolled companies, even where the level of promoter shareholding is

relatively low.

Future governance reforms thus need to address the matter of promoters with minority

shareholding, who are in effective control of managements in such companies that lie at the

cusp of insider and outsider systems.

Enforcement for non-compliance of Corporate Governance Norms

While much has been talked on the policy aspect of the Corporate Governance, at present

monitoring of the compliance of the same is done only through disclosures in the annual

report of the company and periodic disclosures of the various clauses of Clause 49 of the

Listing Agreement on the stock exchange website.

As per Clause 49 of the Listing Agreement, there should be a separate section on

Corporate Governance in the Annual Reports of listed companies, with detailed compliance

report on Corporate Governance. The companies should also submit a quarterly compliance

report to the stock exchanges within 15 days from the close of quarter as per the prescribed

format. The report shall be signed either by the Compliance Officer or the Chief Executive

Officer of the company.

The listed companies should obtain a certificate from either the auditors or practicing

company secretaries regarding compliance with all the clauses of Clause 49 and annex the

certificate with the directors report, which is sent annually to all the shareholders of the

company. The same certificate shall also be sent to the Stock Exchanges along with the

annual report filed by the company. Stock exchanges are required to send a consolidated

compliance report to SEBI on the compliance level of Clause 49 by the companies listed in

the exchanges within 60 days from the end of each quarter.

Listing Agreement is essentially an agreement between exchanges and the listed company.

BSE and NSE have listing departments, which oversee the compliances with the provisions

of listing agreement. Non-submission of corporate governance report may result in

suspension in trading of the scrip. As per the norms laid by BSE, the securities of the

company would trigger suspension for non-submission of Corporate Governance report for 2

consecutive previous quarters or late submission of Corporate Governance report for any 2

out of 4 consecutive previous quarters.

For violations of the provisions of listing Agreement, following course of actions by SEBI is

possible:

o Delisting or suspension of securities

o Adjudication for levy of monetary penalty on companies/directors/promoters by SEBI

o Prosecution

o Debarring directors/promoters from accessing capital market or being associated with listed

companies.

Delisting or suspension is generally not considered an investor friendly action and therefore,

cannot be resorted to as a matter of routine and can be used only in cases of extreme /

repetitive non-compliance. Prosecution, on the other hand, is a costly and time-consuming

process.

In order to strengthen the monitoring of the compliance, following measures may be

considered:

Carrying out of Corporate Governance rating by the Credit Rating Agencies.

Inspection by Stock Exchanges/ SEBI/ or any other agency for verifying the compliance

made by the companies.

Imposing penalties on the Company/its Board of Directors/Compliance Officer/Key

Managerial Persons for non-compliance either in sprit or letter Presently, provisions of listing

agreement are being converted into Regulations for better enforcement.

Companies Bill, 2011 and its Impact on Corporate Governance in India

The foundations of the comprehensive revision in the Companies Act, 1956 was laid in 2004

when the Government constituted the Irani Committee to conduct a comprehensive review of

the Act. The Government of India has placed before the Parliament a new Companies Bill,

2011 that incorporates several significant provisions for improving corporate governance in

Indian companies which, having gone through an extensive consultation process, is expected

to be approved in the 2012 Budget session. The new Companies Bill, 2011 proposes

structural and fundamental changes in the way companies would be governed in India and

incorporates various lessons that have been learnt from the corporate scams of the recent

years that highlighted the role and importance of good governance in organizations.

Significant corporate governance reforms, primarily aimed at improving the board oversight

process, have been proposed in the new Companies Bill; for instance it has proposed, for the

first time in Company Law, the concept of an Independent Director and all listed companies

are required to appoint independent directors with at least one third of the Board of such

companies comprising of independent directors. The Companies Bill, 2011 takes the concept

of board independence to another level altogether as it devotes two sections61 to deal with

Independent Directors. The definition of an Independent Director has been considerably

tightened and the definition now defines positive attributes of independence and also requires

every Independent Director to declare that he or she meets the criteria of independence.

In order to ensure that Independent Directors maintain their independence and do not become

too familiar with the management and promoters, minimum tenure requirements have been

prescribed. The initial term for an independent director is for five years, following which

further appointment of the director would require a special resolution of the shareholders.

However, the total tenure for an independent director is not allowed to exceed two

consecutive terms. In order to balance the extensive nature of functions and obligations

imposed on Independent Directors, the new Companies Bill, 2011 seeks to limit their liability

to matters directly relatable to them and limits their liability to only in respect of acts of

omission or commission by a company which had occurred with his knowledge, attributable

through board processes, and with his consent or connivance or where he had not acted

diligently. In the background of the current provisions in the Companies Act, 1956 which do

not provide any clear limitation of liability and have left it to be interpreted by Courts, it is

helpful to provide a limitation of liability clause.

The new Bill also requires that all resolutions in a meeting convened with a shorter notice

should be ratified by at least one independent director which gives them an element of veto

power. Various other clauses such as those on directors responsibility statements, statement

of social responsibilities, and the directors responsibilities over financial controls, fraud, etc,

will create a more transparent system through better disclosures.

A major proposal in the new Bill is that any undue gain made by a director by abusing his

position will be disgorged and returned to the company together with monetary fines. Other

significant proposals that would lead to better corporate governance include closer regulation

and monitoring of related-party transactions, consolidation of the accounts of all companies

within the group, self-declaration of interests by directors along with disclosures of loans,

investments and guarantees given for the businesses of subsidiary and associate companies. A

significant first, in the proposals under the new Companies Bill, is the provision that has been

made for class action suits; it is provided that specified number of members may file an

application before the Tribunal on behalf of members, if they feel that the management or

control of the affairs of the company are being conducted in a manner prejudicial to the

interests of the company or its members. The order passed by the Tribunal would be binding

on the company and all its members. The enhanced investor protection framework, proposed

in the Bill, also empowers small shareholders who can restrain management from actions that

they believe are detrimental to their interests or provide an option of exiting the company

when they do not concur with proposals of the majority shareholders.

The Companies Bill, 2011 seeks to provide clarity on the respective roles of SEBI and the

MCA and demarcate their roles while the issue and transfer of securities and non-payment

of dividend by listed companies or those companies which intend to get their securities listed

shall be administered by the SEBI all other cases are proposed to be administered by the

Central Government. Furthermore, by focusing on issues such as Enhanced Accountability on

the part of Companies, Additional Disclosure Norms, Audit Accountability, Protection for

Minority Shareholders, Investor Protection, Serious Fraud Investigation Office (SFIO) in the

new Companies Bill, 2011, the MCA is expected to be at the forefront of Corporate

Governance reforms in India.

Institutional investors:

Topology of the institutional investors community in India

Development Financial Institutions

Starting in 1948 and throughout the 1950s and 1960s, the Government of India (GOI)

established three Development Financial Institutions (DFIs) to cater to the long-term

finance needs of the countrys industrial sector. These were IFCI, the first DFI set up

in 1948, ICICI, established in 1955 and IDBI, which was established in 1964.

The Reserve Bank of India (RBI) and the GOI nurtured these three DFIs through

financial incentives and other supportive policy measures. They were provided with

low-cost funds which they on-lent to industry at subsidized rates. They were also

allowed to issue bonds guaranteed by the Government. The Reserve Bank of India (RBI)

allocated a substantial part of its National Industrial Credit (Long Term

Operations) funds to IDBI.

During the 1970s and 1980s, the availability of subsidized loans and tax incentives

gave rise to mushrooming of new projects with meagre capital inputs from promoters.

This created a moral hazard problem, and the resultant accumulation of nonperforming assets

in the DFI portfolios. For example, IFCI reported 32.3 percent of total assets to be non-

performing as of March 2004.

Since the early 1990s, there have been several changes in the Governments attitude towards

the DFIs when financial sector liberalization began. The DFIs no longer have access to

subsidized funds or budgetary support5. In addition, they faced competition

in the areas of term finance from banks offering lower rates. The change in operating

environment coupled with accumulation of nonperforming assets caused serious

financial stress to the term-lending institutions, particularly for IFCI. A restructuring

package has been put into effect by the GOI and endorsed by the IFCI Board which

has agreed in principle to a merger with Punjab National Bank. In 2002, ICICI

merged with ICICI Bank and is now a widely-held listed bank with foreign

institutional investors holding 43.64 percent of the equity as of March 31, 2005.

Similarly, in December 2003, the IDBI (Transfer of Undertaking and Repeal) Act

2003 was passed by Parliament to transform IDBI into a banking company. IDBI Ltd.

is now registered as a company under the Companies Act, 1956 to carry out banking

business in accordance with the provisions of the Banking Regulation Act, 1949.

Two other major groups of Government-owned financial institutions have had a major

impact on equity investment trends in India. The first group consists of state-owned

life and non-life insurance corporations; the second group is made up of the public

sector mutual funds.

State-owned insurance companies

The nationalization of insurance business in India resulted in the establishment of the

Life Insurance Corporation (LIC) in 1956 as a wholly-owned corporation of the

Government of India. The Government of India consolidated 240 private life insurers

and provident societies, and LIC came into being. LIC currently offers over 50 plans

to cover life at various stages through a network of 2,048 branches. Besides

conducting insurance business, LIC invests a major portion of its funds in Government

and other approved securities, extends assistance to infrastructure projects and

provides financial assistance to the corporate sector through term loans and

underwriting/direct subscription to corporate shares and debentures.

The nationalization of the non-life insurance sector resulted in the formation of the

General Insurance Corporation (GIC) in 1973. GIC was set up as a holding company

with four subsidiaries (de-linked since 2000), New India Assurance (NIA), National

Insurance Corporation (NIC), Oriental India Insurance (OIC), and United India

Insurance (UII). NIC, incorporated in 1906, was nationalized in 1973 following the

amalgamation of 22 foreign and 11 Indian insurance companies. NIA, incorporated in

1919 and nationalized in 1973, had a pioneering presence in the Indian insurance

sector. It insured Indias first domestic airlines and was responsible for the entire

satellite insurance program of the country. UII was formed in 1973 following the

merger of 22 private insurance companies. As of March 31, 2004, it had a market

share of 22 percent among PSU insurers. OIC was incorporated in 1947 and

nationalized in 1973. It offers special covers for large projects like power plants,

petrochemical, steel and chemical plants. GIC and its erstwhile subsidiaries also

provide financial assistance to the corporate sector through term loans and direct

subscription to corporate shares and debentures.

Private sector insurance companies

In 1993, the Malhotra Committee was set up to evaluate the insurance industry and

recommend future directions. The committee submitted its report in 1994. Its major

recommendations included (i) reduction of Government shareholding in the stateowned

insurance companies to 50 percent, and a break up of GIC; (ii) allowing private

companies with a minimum paid up capital of INR 1 billion to enter industry, as well

as foreign companies in collaboration with domestic companies; and (iii) setting up an

insurance regulatory body11. In 2000, GICs supervisory role over its subsidiaries was

extinguished and GIC was re-designated Indian Re-insurer to function exclusively

as life and non-life re-insurer. In March 2002, GIC ceased to be a holding company for

its subsidiaries and their ownership was vested with the Government of India.12 In

April 2002, the Insurance Regulatory and Development Authority (IRDA) came into

being. IRDA is responsible for registering private insurance companies and framing

regulations for the industry.

The Insurance Regulatory and Development Authority (IRDA) Act allows foreign

companies a 26 percent equity stake in Indian insurance companies. As on June 2005,

there were 14 life insurance companies, 14 non-life insurance companies, and one reinsurer

(GIC) registered with IRDA. The Life Insurance Corporation of India (LIC) is the

only life insurer in the public sector. Eleven of the 13 private companies have an FDI

owning 26 percent of their equity, one (HDFC) has an 18.60 percent foreign shareholder,

and Sahara India is wholly Indian owned. Seven of the eight private companies in the general

insurance sector have foreign equity holdings of 26 percent. The only one that

does not is Reliance General Insurance Co. Ltd. Of the 13 companies in the private life

insurance sector, only one, namely Sahara India, does not have a foreign promoter.

The public sector still holds the overwhelming market share of premiums underwritten.

Of the total premiums (first year premiums and renewal premiums) in 2002-03, the LIC

had 95.29 percent of the market share while the private sector had just 4.71 percent. In

the non-life segment, the new insurers held a market share of 13 percent.

Mutual funds and FIIs

The Indian mutual fund industry came into being in 1963 with the formation of Unit

Trust of India, at the initiative of the Government of India and RBI. The history of mutual

funds in India can be broadly divided into four distinct phases16. In the first phase from

1964 to 1987, UTI was the only mutual fund operating in India. In the second phase

between 1987 and 1993, public sector banks and insurance companies were permitted to

set up mutual funds. State Bank of India, Punjab National Bank, Canara Bank, Indian

Bank, Bank of Baroda, Bank of India, LIC and GIC all set up mutual funds. The third

phase between 1993 and 2003 saw the entry of private sector mutual funds. As of January

2003, there were 33 mutual funds with total assets of INR 1218.05 billion. The Unit Trust

of India with INR 445.41 billion of assets under management was the largest. The fourth

phase starting in 2003 saw the beleaguered UTI being split into two separate entities.

India opened its stock markets to foreign institutional investors (FII) in September 1992.

FII include, among others, pension funds, mutual funds, asset management companies,

investment trusts, institutional portfolio managers, banks and insurance companies,

proposing to invest in India as broad-based funds (with at least 20 investors, each of

them not holding no more than 10 percent of the FII fund). The total number of FII

registered with SEBI crossed 700 in May 2005.

The entry and dominance of private sector mutual funds and FIIs in the last decade

completes the transition from a highly leveraged Indian corporate sector heavily

dependent on the DFIs, to an increasingly market-based system.

III. Legal and regulatory framework for Institutional

Investors

Institutional Structure of Regulation

Banks and DFIs

Banks and DFIs fall under the oversight of the RBI, with an implicit regulatory role

played by the Ministry of Finance. The main legislation governing banks and DFIs is

the Reserve Bank Act, 1934 and the Banking Regulation Act (1949). As discussed in the

previous sections, the Acts of Parliament governing IDBI and UTI were repealed in 2002

and 2004 to facilitate conversion of IDBI into a banking entity and into market-linked

mutual fund respectively.

Insurance companies

In the insurance sector, the two largest government-owned insurance companies- LIC and

GIC were set up under Acts of Parliament. Both these institutions fall under the

regulation and supervision of both the Ministry of Finance and the insurance regulator,

the Insurance Regulatory and Development Authority (IRDA). Other public sector

insurers and private sector insurers fall under the purview of the Insurance Act and

regulations issued by the regulator IRDA in 1999.

Mutual Funds and Foreign Institutional Investors

The regulatory framework for domestic mutual funds and foreign institutional investors

consists of the Mutual Fund Regulations (1992) and the FII Regulations (1994), issued

and enforced by SEBI. The regulations lay down the minimum eligibility criteria for

entry, net worth standards, and disclosure norms. In addition mutual funds and foreign

institutional investors are expected to follow a code of conduct that conforms to

guidelines issued by SEBI. The code of conduct lays out the broad principles of proper

business conduct and functioning of the intermediaries .

In 1996, all mutual funds except UTI came within the purview of the SEBI (Mutual

Fund) Regulations, 1996. UTI which was set up under an Act of Parliament was not

under the regulatory purview of SEBI until 2002 when the UTI Act was repealed and the

fund was split into UTI-I and UTI-II. Thereafter, UTI I and II were brought under the

regulatory purview of SEBI.

The Association of Mutual Funds of India (AMFI) is the self-regulatory organization

(SRO) set up in 1997. It is involved in a) recommending and promoting best business

practices and code of conduct to be followed by mutual funds; and b) interacting with SEBI

on all matters concerning the industry. In addition AMFI is addresses specific

technical issues faced by the mutual fund industry such as developing valuation norms

for illiquid securities. Amongst other activities conducted by the AMFI are administering

the certification examinations for persons involved in the mutual fund industry which

includes employees of the asset management companies and the various brokers,

distributors of mutual fund products. The AMFI is also involved in investor education

and awareness building.

SEBI issued the FII regulations in November 1995, based on guidelines issued by the

GOI in 1992. The regulations mandate the registration of foreign institutional investors

with SEBI. The FIIs were initially permitted access to primary and secondary markets for

securities and mutual fund products, with a stipulated minimum 70 percent investment in

equity. The initial ceilings on the ownership of any firm were 5 percent for a single FII

and 24 percent for all FIIs taken as a group. Individual ceiling on ownership has been

eased to 10 percent since February 2000, and the overall ceiling for all FIIs was removed

in September 2001 in favor of sectoral caps subject to shareholder resolution. FIIs have

also been permitted to invest in corporate and government bonds, and in derivative

securities. Further, foreign firms and individuals have been permitted access to the Indian

markets through FIIs as sub-accounts since February 2000. In the year 2003, earlier

limitations on FII hedging currency risk using currency forwards were removed, and FII

approval was streamlined and vested solely in SEBI, instead of SEBI and RBI as required

earlier.

Pension Funds Industry

A new Defined Contribution pension system has been introduced, which is applicable to

all Government employees recruited after January 1, 2004. This New Pension System

will be regulated by Pension Fund Regulatory and Development Authority (PFRDA)

promulgated through an ordinance on December 30, 2004. The PFRDAs role is to

license and supervise pension fund managers, lay down guidelines on the number of

market participants, prudential norms, investment criteria and capital requirements of

pension fund managers. PFRDA is also expected to issue FDI caps for the pension sector.

It is expected that initial investments in equity will be somewhat limited. All pre-January

2004 employees can also voluntarily join the new scheme to get an additional benefit.

Similarly, all those covered by the Employees Provident Fund (EPF) will continue in it,

but can voluntarily join the new scheme to. To a large extent, the new pension schemes

will resemble mutual funds, and subscribers will have a choice of parking their savings

(a) predominantly in equity,

(b) debt & equity mix, or

(c) entirely in debt instruments and

Government paper. Many of the major players in the mutual fund and the insurance

industry are set to enter the pension sector, expected to grow to INR 500 billion by 2010.

Board representation/Clause 49

The regulatory framework governing the boards of directors of Indian corporations is set

out in Chapter II (sections 252 to 269) of the Companies Act, 1956. In addition, Clause

49 of the Listing Rules issued by SEBI, which is implemented on a comply or explain

basis, also provides a framework for the board of directors of listed companies. Board

members have a fiduciary obligation to treat all shareholders fairly. At least two-thirds

of the board of directors should be rotational. One-third of the board consists of

permanent directors. These include promoters, executive directors and nominee directors.

Clause 49 applies to all listed companies with paid up share capital of at least INR 30

million36 (USD 660,000) or that have had a net worth of INR 250 million (USD 5.5

million). There are mandatory and non-mandatory requirements.

Independent Directors

One of the fundamental innovations of Clause 49 was to introduce the concept of

independent directors in the Indian corporate governance framework, further to the

recommendation of the Kumaramangalam Birla Committee Report on Corporate

Governance (The Kumaramangalam Committee) in 2000, and the additional

recommendations of The Narayana Murthy Committee in 2003. In this framework, the

members of the modern Indian board are jointly and severally accountable to all

shareholders without distinction, and hold the fiduciary position of a trustee for the

company. They ensure the strategic guidance of the company and monitor management.

Stakeholders, including creditors, are protected by contract law and specific legislation.

Section IA of Clause 49 requires issuers to have at least one-third independent directors

on their boards, if the functions of chairman of the board and CEO are decoupled, and 50

percent otherwise.37

The updated Clause 49 defines an independent director as a non-executive director who,

(a) apart from receiving directors remuneration, does not have any material pecuniary

relationships or transactions with the company, its promoters, its senior management or

its holding company, its subsidiaries and associated companies;

(b) is not related to

promoters or management at the board level or at one level below the board;

(c) has not

been an executive of the company in the immediately preceding three financial years; (d)

is not a partner or an executive of the statutory audit firm or the internal audit firm that is

associated with the company, and has not been a partner or an executive of any such firm

for the last three years. This will also apply to legal firm(s) and consulting firm(s) that

have a material association with the entity;

(e) is not a supplier, service provider or

customer of the company. This should include lessor-lessee type relationships also; and

(f) is not a substantial shareholder of the company, i.e. owning two percent or more of the

voting shares. It also caps to three terms of three years the mandates of independent

directors.

Nominee Directors

As discussed earlier, a series of DFIs were created by Acts of Parliament to support the

development of industrial companies, by extending loans to the latter or subscribing to

debentures issues. To protect the public institutions investments and equip it with

effective risk management tools, each founding Act of Parliament of the DFI stipulated

that the latter should insert two specific clauses in their loan agreements, systematically:

(1) a convertibility clause, which allowed the DFI to convert its loan/debenture into equity

(and hence allowed the DFI to take control of the corporation), if the company

defaulted on its debt obligation to the DFI; and

(2) a nominee director clause, which

gave the DFI the right to appoint one or more directors to the board of the borrowing

company.

In March 1984, the Banking Division of the Ministry of Finance, Department of

Company Affairs issued its Policy Guidelines relating to Stipulation of Convertibility

Clause and Appointment of Nominee Directors. The guidelines specified that IDBI,

IFCI, ICICI and IRCI should create a separate Cell the exclusive and whole-time function of

which would be to represent the institutions on the Boards of Companies. Outsiders should be

appointed as nominee directors only as additional directors were needed.

Nominee directors should be appointed on the Boards of all MRTP companies assisted by

the institutions. As regard non-MRTP companies, nominee directors should be appointed

on a selective basis, especially when one or more of the following conditions prevail: (a) the

unit is running into problems and is likely to become sick;

(b) institutional holding is more than 26 percent; and

(c) where the institutional stake by way of loans/investment

exceeds INR 50 million.

The Guidelines further stipulated that nominee directors should be given clearly

identified responsibilities in a few areas which are important for public policy. An

illustrative list of such responsibilities was provided, including

(a) financial performance

of the company;

(b) payments of dues to the institutions; (c) payment of government

dues, including excise and custom duties, and statutory dues; (d) inter-corporate

investment in and loans to or from associated concerns in which the promoter group has

significant interest; (e) all transaction in shares; (f) expenditure being incurred by the

company on management group; and (g) policies relating to the ward of contracts and

purchase and sale of raw materials, finished goods, machinery, etc. In addition the

Guidelines specified that the nominee directors should ensure that the tendencies of the

companies towards extravagance, lavish expenditure and diversion of funds are curbed.

With a view to achieve this object, the institutions should seek constitution of a small

Audit sub-committee of the board of directors for the purpose of periodic assessment of

expenditure incurred by the assisted company, in all cases where the paid-up capital of

the company is INR 50 million or more. The institutional nominee director will

invariably be a member of this Audit Sub-committee.

Considering that the practice of audit committees only became accepted internationally as

best practice in the late 1990s, the Ministry of Finance (MOF) Guidelines were in some

respect ahead of their time. However, Section 30.A of of the Industrial Development

Bank of India Act, (1964) stipulated that nominee directors would not (1) be subject to

the provisions of the Companies Act, or to provisions of the memorandum, articles of

associations or any other instrument relating to the industrial concern, nor any provisions

regarding share qualifications, age-limit, number of directorships, or removal from

office; and (2) incur any obligation or liability be reason only of his being a director or

for anything done or omitted to be in good faith in the discharge of his duties as a director

or anything in relation thereto. Hence, nominee directors were not jointly and severally

responsible to shareholders for the actions of the board.

In 1991, the Monopolies and Restrictive Trade Practices Act, 1969 (MRTP Act) was

amended. Provisions relating to concentration of economic power and pre-entry

restrictions with regard to prior approval of the Central Government for establishing new

undertaking, expanding on existing undertaking, amalgamations, mergers and takeovers

of undertakings were all deleted from the statute through the amendments. The causal

thinking in support of the 1991 amendments is contained in the Statement of Objects and

Reasons appended to the 1991 Amendment Bill in the Parliament41.

Finally, in December 2003, the Industrial Development Bank (Transfer of Undertaking

and Repeal) Act, 2003 provided for the transfer and vesting of the undertaking of the

Industrial Development Bank of India to, and in IDBI Bank. However, Section 15 of Act

53 grandfathered the immunity extended to nominee directors. Specifically, section 15

stipulated that notwithstanding the repeal of the Industrial Development Act, 1964, the

provisions of Section 30A of the Act so repealed will continue to be applicable in respect

of the arrangement entered into by the Development Bank with an industrial concern up

to the appointed day and the Company [Industrial Development Bank of India] will be

entitled to act upon and enforce the same as fully and effectually as if this Act has nor

been repealed.

In 2003, The Kumara Mangalam Birla Committee recommended that institutions should

appoint nominees on the boards of companies only on a selective basis, where such

appointment is pursuant to a right under loan agreements or where such appointment is

considered necessary to protect the interest of the institution. It further recommended

that when a nominee of an institution is appointed as a director of the company, he should

have the same responsibility, be subject to the same discipline and be accountable to the

shareholders in the same manner as any other director of the company. In addition, if the

nominee director reports on the affairs of the company to a department of the institution

that nominated him on the board of the portfolio company, the institution should ensure

that there exist Chinese walls between such department and other departments which may

be dealing in the shares of the company in the stock market.

The Narayan Murthy Committee felt that the institution of nominee directors whether

from investment institutions or lending institutions creates a conflict of interest. The

Committee recommended that nominee directors should not be considered as independent

and stressed that it is necessary that all directors, whether representing institutions or

otherwise, should have the same responsibilities and liabilities as other directors.

However, as discussed in Section V, the final guidelines issued by SEBI in Clause 49

suggest that nominee directors whether from lending or investment institutions shall be

deemed to be independent directors.

Role of I nstitutional Investors

Corporate governance codes and guidelines have long recognised the important role that

institutional investors have to play in corporate governance. The effectiveness and

credibility of the entire corporate governance system and the company oversight to a large

extent depends on the institutional investors who are expected to make informed use of

their shareholders rights and effectively exercise their ownership functions in companies

in which they invest. Increased monitoring of Indian listed corporations by institutional

investors will drive the former to enhance their corporate governance practices, and

ultimately their ability to generate better financial results and growth for their investors. At

present, there are four main issues with role of institutional investor and corporate

governance:

Issues relating to disclosure by institutional investors of their corporate governance

and voting policies and voting records

Issues relating to the disclosure of material conflicts of interests which may affect the

exercise of key ownership rights

Focus on increasing the size of assets under management rather than on improving

the performance of portfolio companies.

Institutional investors are becoming increasingly short-term investors.

Several countries mandate their institutional investors acting in a fiduciary capacity to

disclose their corporate governance policies to the market in considerable details. Such

disclosure requirements include an explanation of the circumstances in which the

institution will intervene in a portfolio company; how they will intervene; and how they will

assess the effectiveness of the strategy. In most OECD countries, Collective Investment

Schemes (CIS) are either required to disclose their actual voting record, or it is regarded

as good practice and implemented on an comply or explain basis.

In addition, Principle 1G of the OECD Principles calls for institutional investors acting in

a fiduciary capacity to disclose their overall corporate governance and voting policies

with respect to their investments, including the procedures that they have in place for

deciding on the use of their voting rights.

SEBI has recently required listed companies to disclose the voting patterns to the stock

exchanges and Asset Management Companies of Mutual Funds to disclose their voting

policies and their exercise of voting rights on their web-sites and in Annual Reports.

Ministry of Corporate Affairs' (MCA) initiative on E-voting will also enable scattered

minority shareholders to exercise voting rights in General Meetings.

a) Institutional investors should have a clear policy on voting and disclosure of

voting activity

Institutional investors should seek to vote on all shares held. They should not

automatically support the board. If they have been unable to reach a satisfactory

outcome through active dialogue then they should register an abstention or vote

against the resolution. In both instances, it is good practice to inform the company in

advance of their intention and the reasons thereof. Institutional investors should

disclose publicly voting records and if they do not, the reasons thereof.

b) Institutional investors to have a robust policy on managing conflicts of interest

An institutional investor's duty is to act in the interests of all clients and/or

beneficiaries when considering matters such as engagement and voting. Conflicts of

interest will inevitably arise from time to time, which may include when voting on

matters affecting a parent company or client. Institutional investors should formulate

and regularly review a policy for managing conflicts of interest.

c) Institutional investors to monitor their investee companies

Investee companies should be monitored to determine when it is necessary to enter

into an active dialogue with their boards. This monitoring should be regular and the

process should be clearly communicable and checked periodically for its

effectiveness.

As part of these monitoring, institutional investors should:

Seek to satisfy themselves, to the extent possible, that the investee company's

board and committee structures are effective, and that independent directors

provide adequate oversight, including by meeting the chairman and, where

appropriate, other board members;

Maintain a clear audit trail, for example, records of private meetings held with

companies, of votes cast, and of reasons for voting against the investee

company's management, for abstaining, or for voting with management in a

contentious situation; and

Attend the General Meetings of companies in which they have a major holding,

where appropriate and practicable.

Institutional investors should consider carefully the explanations given for departure

from the Corporate Governance Code and make reasoned judgements in each

case. They should give a timely explanation to the company, in writing where

appropriate, and be prepared to enter a dialogue if they do not accept the

company's position.

Institutional investors should endeavor to identify problems at an early stage to

minimise any loss of shareholder value. If they have concerns they should seek to

ensure that the appropriate members of the investee company's board are made

aware of them.

Institutional investors may not wish to be made insiders. They will expect investee

companies and their advisers to ensure that information that could affect their ability

to deal in the shares of the company concerned is not conveyed to them without

their agreement.

d) Institutional investors to be willing to act collectively with other investors

where appropriate

At times collaboration with other investors may be the most effective manner to

engage. Collaborative engagement may be most appropriate during significant

corporate or wider economic stress, or when the risks posed threaten the ability of

the company to continue. Institutional investors should disclose their policy on

collective engagement. When participating in collective engagement, institutional

investors should have due regard to their policies on conflicts of interest and insider

information.

e) Institutional investors to establish clear guidelines on when and how they will

escalate their activities as a method of protecting and enhancing shareholder

value

Institutional investors should set out the circumstances when they will actively

intervene and regularly assess the outcomes of doing so. Intervention should be

considered regardless of whether an active or passive investment policy is followed.

Initial discussions should take place on a confidential basis. However, if boards do

not respond constructively when institutional investors intervene, then institutional

investors will consider whether to escalate their action, for example, by

holding additional meetings with management specifically to discuss concerns;

expressing concerns through the company's advisers;

meeting with the chairman, senior independent director, or with all independent

directors;

intervening jointly with other institutions on particular issues;

making a public statement in advance of the AGM;

submitting resolutions at shareholders' meetings; etc.

f) Institutional investors to report periodically on their responsibilities and voting

activities

Those who act as agents should regularly report to their clients details of how they

have discharged their responsibilities. Such reports may comprise of qualitative as

well as quantitative information. The particular information reported, including the

format in which details of how votes have been cast are presented, should be a

matter for agreement between agents and their principals.

Those that act as principals, or represent the interests of the end-investor, should

report at least annually to those to whom they are accountable on their policy and its

execution.

Like US funds, Indian asset management funds are now required to disclose their

general policies and procedures for exercising the voting rights in respect of the

shares held by them on their websites as well as in the annual report distributed to

the unit holders from the financial year 2010-11. However, there is only a marginal

increase in for/against votes and many funds fail to even attend meetings and have

abstention as a policy. Even among funds that voted, there is little alignment

between the votes and the voting policy.

In view of above, existing policy need to be examined. It may be deliberated on how

to create incentives for institutional investors that invest in equities to become more

active in the exercise of their ownership rights, without coercion, without imposing

illegitimate costs on them, and given Indias specific situation.

Fund houses should be mandated to adopt the global practice of quarterly vote

reporting and fund-wise vote reporting and to adopt detailed voting policies. Further,

vote reporting by fund houses should also be subject to audit.

V. Policy recommendations

The recommendations of the Kumaramangalam Birla Committee on the issue of

Institutional shareholders provide the framework for policy makers intervention in

India. The Committee highlighted that institutional shareholders, who own shares largely

on behalf of the retail investors, have acquired large stakes in the share capital of listed

Indian companies; they have or are in the process of becoming major shareholders in

many listed companies and own. The Committee called for institutional investors to play

a bigger role in the corporate governance of their portfolio companies, and stressed that

retail investors are relying on them for positive use of their voting rights. The Committee

highlighted practices elsewhere in the world where institutional shareholders influence

the corporate policies of their portfolio companies to maximize shareholder value, and

recommended that institutional investors follow suit. The Committee stressed that it is

important that institutional shareholders should put to good use their voting power.

The Committee recommends that the institutional shareholders should take an active

interest in the composition of the board of directors of their portfolio companies; be

vigilant; maintain regular and systematic contact at senior level for exchange of views on

management, strategy, performance and the quality of management; ensure that voting

intentions are translated into practice; and evaluate the corporate governance performance

of their portfolio companies. These were non-mandatory recommendations.

Incentives for institutional investors to play a more active role in the corporate

governance of their portfolio companies: It has long been recognized that institutional

investors, especially those acting in a fiduciary capacity, are better positioned than retail

investors to play a monitoring role in their portfolio companies because they do not face

the collective action (free rider) problem to the same extent (See Box-1 for a description

on free rider and collective action). The potential returns from their equity investment can

outweigh the monitoring costs. However, as discussed in Section IV, at present most

Indian institutional investors take a passive role in the corporate governance of their

portfolio companies. Even those institutions who exercise their ownership rights more

actively, to a large extent share the same view with regard to the monitoring of

management. Management is primarily screened ex-ante, at the time of deciding to take

an equity position in a company. Once an institution has taken the decision to invest in a

company, it supports its management. If and when it loses confidence in management, it

sells its shares.

From a cost/benefit standpoint, institutional investors consider that the potential benefits

of taking an active role in the corporate governance of their portfolio companies are not

commensurate with the costs associated with such monitoring role. This approach may be

legitimate, given the concentrated ownership structure of listed companies, the small

equity stakes of each individual institutional investor, and the lack of cooperation

between institutional investors.

However, the experience of OECD countries and the most dynamic emerging market

countries48 suggests that corporate governance practices of listed companies and their

voluntary compliance with Clause 49, and ultimately the protection of shareholders

rights, could be improved if institutional investors acting in a fiduciary capacity could be

induced to participate more actively in the corporate governance of their portfolio

companies.

From a policy standpoint, it is desirable that institutions acting in a fiduciary capacity,

such as pension funds, collective investment schemes and insurance companies should

consider the right to vote an intrinsic part of the value of the investment being undertaken

on behalf of their client. Failure to exercise the ownership rights could result in a loss to

their investors who should therefore be made aware of the policy followed by the

institutional investors.

In the United Sates, under the Employee Retirement Income Security Act (ERISA), a

pension plan fiduciary obligation includes the voting of proxies. In addition, the

Department of Labor considers that a pension plan sponsors fiduciary duty in managing

plan assets includes a duty to vote proxies in the interests of plan beneficiaries, and a

positive duty to actually vote on issues that may affect the value of the plans