Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Promoting Efficiency in The Sugar Industry by Beulah de La Pefia

Promoting Efficiency in The Sugar Industry by Beulah de La Pefia

Uploaded by

Diane UyOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Promoting Efficiency in The Sugar Industry by Beulah de La Pefia

Promoting Efficiency in The Sugar Industry by Beulah de La Pefia

Uploaded by

Diane UyCopyright:

Available Formats

PROMOTING EFFICIENCY IN THE SUGAR INDUSTRY

by

Beulah de la Pefia

1. Growth Trends

The sugar industry is one of the Philippines' oldest industries contributing substantially to the

economy. Sugarcane production increased at the annual growth rate of 6.8% per year from 1950

to 1976. Until the mid-70's, it provided about 9% of agricultural gross value added or 2.2% of

GNP. It was a major export earner of the country contributing about 15% - 18% of export

receipts in the early 70's.

Production

In the last two decades the industry has considerably contracted. Cane

production declined from 29.3 million MT in 1975-761 to a low of 13.7 million MT

in 1986-87 but recovered to 23.9 million MT in 1992-93 and 18.5 million MT in

1994-95. Sugar production dropped from 2.9 million MT in 1975-76 to 1.3 million

MT in 1986-87 and about 2 million MT in 1991-92 and 1.6 million MT in 1994-95.

Hectarage

Hectarage devoted to sugar likewise declined from 544 thousand hectares in 1975-76 to 269

thousand hectares in 1986-87 and 376 thousand hectares in 1994-95.

1 The sugar crop year is September to August of the following year.

1

Exports

Exports fell from a high of 2,149 thousand MT in 1976-77 to 156.5 thousand MT in 1986-87 and

264.9 thousand MT in 1992-93 to 174 thousand MT in 1994-95. These figures represent 80% of

production in 1976-77, 11.6% in 1986-87, 12.8% in 1992-93 and 10.5% in 1994-95. Imports of

raw and refined sugar in 1994-95 reached 353 thousand MT.

Consumption

Domestic consumption has been increasing at the rate of 3.9% per annum from 1980 to 1995. It

is recorded at 1.8 million MT in 1994-95.

Sources of Growth

The sugar industry's impressive growth in the early years until the mid 70's was largely spurred

by preferential access to the high priced US market. After the Laurel-Langley Agreement and the

US Sugar Act expired in 1974, the sugar industry had to contend with the highly competitive and

volatile world market in order to maintain its growth. Government's efforts to stabilize prices in

the domestic market and maintain the revenues from sugar exports, basically through the

PHILEX and later NASUTRA monopolies in sugar trading, proved disastrous. The decade from

1975 to 1985 ended with NASUTRA unable to pay sugar planters and millers for their 1984-85

sugar stocks, massive default on sugar crop loans, and a much smaller sugar industry.

The industry's recovery from 1987 to 1992 was encouraged by the abolition of the sugar trading

monopoly in 1986, growing demand in the protected domestic market, and the restoration of

some access to the US market.

Productivity

Cane farm and sugar mill efficiencies and productivity are low. Overall mill efficiency,

measured as the product of percent sucrose extraction and boiling house losses averaged at

78.6% in 1993-94. At the farm level, cane yields have

1 2

not improved averaging 57.6 tons cane/hectare from'1980 to 1995 and posting at 49 tons

cane/hectare in 1994-95. Sugar recovery from cane (PS/TC) declined from 1.59 in 1980-81 to

1.41 in 1994-95. Thus, the Philippines produces sugar at about 14 centslib when South Africa,

Thailand, Brazil, and Australia do it at the cost of less than 1 0 cents/lb.

11. GOVERNMENT POLICIES

The major existing policies that affect the sugar industry were instituted for laudable objectives:

to distribute the benefits of the high-priced US quota market across the industry and to alleviate

rural poverty. These strategies however created distortions in the incentive structure which have

had major negative impact on the industry's development.

Supply Controls

The regulatory framework for sugar marketing limited the supply and kept prices high in the

domestic market. The specific regulations are:

1 . The market quota system allocates the sugar produced into five (5) categories: A for the

US import quota market, B for the domestic market, C for reserve, D for exports to

countries other than the US, and E which may be bought at the world price by exporting

firms using sugar as input. In 1992, the Sugar Regulatory Administration (SRA) created

another quota category -- the "Bl" sugar which goes into the domestic market but could be

withdrawn from storage only after 120 days.

The SRA estimates production as the cropyear starts and on this basis issues a "sugar

order" mandating the allocation, in terms of percentages, of the sugar to be produced into

the various destinations. The percentage allocation is adjusted or revised as sugar

production estimates are revised or as the Philippine share of the US quota market

changes. All producers and millers follow this percentage allocation.

3

This quota allocation system was adopted to allow all planters and millers proportionately

equal access to the higher-priced market, more specifically, the US quota market.

2. The market quota is implemented through a quedan system and controls on the

withdrawal of sugar from the warehouses. All milled i.e., raw and washed, sugar is

deposited in registered warehouses and owners of the sugar are given quedans which state

the classification of the sugar, i.e. market destination. The quedan forms are serially

numbered and its printing supervised and controlled by the SRA. As proof of ownership

of sugar, the quedan is a negotiable instrument. Sugar is traded using the quedans. It is

withdrawn from warehouses only with a release order from SRA and upon surrender of

the quedan.

In 1992, the SRA started a system of quedaning refined sugar. The refineries issue the refined

sugar quedan when it accepts the raw sugar for tolling. Refineries are not allowed to accept

sugar for tolling unless accompanied by a sugar release order issued by the SRA. In the case of

integrated refineries (i.e., refineries attached to a mill), refining is done only after surrender of the

raw sugar quedans and replacement with refined sugar quedans. Refined sugar can be withdrawn

only with the surrender of the refined sugar quedans.

3. lnspite of the import liberalization program and tariff reform program being implemented

by the government, import barriers continue to protect the sugar industry from

international competition. EO 8 issued in 1992 was supposed to have paved the way for

the lifting of quantitative restrictions for sugar as it adjusted the tariff to 75%. This rate

was to be scaled down over a two-year period to the regular rate of 50% by mid 1995.

However, 1995 saw the Philippine accession to the UR-WTO, thus committing the

country to remove all quantitative restrictions on imports of agricultural products (except

rice) and to replace these by tariffs. Ironically, this opened the door for the re-adjustment

in 1996 of sugar tariffs to 1 00% provided that some minimum volume (38,000 MT in

1996) would be imported at 50% tariff. This effectively rules out imports outside of

38,000 MT because the domestic industry can compete as long as tariffs remain

1 4

2. The transport vehicles can not load to full capacity because cane from different farms can

not be mixed until they have been properly weighed and analyzed for sugar content at the

mill reception.

3. The trucks take a longer time to turn-around from the mill because of the waiting time at

the reception, a mill function not being improved by mills because of the earlier discussed

investment disincentive,

Mills report that some 30% to 45% of their total cost of manufacturing raw sugar is spent on

hauling canes, the biggest item in the operational budget of a typical mill. In addition, the losses

due to cane deterioration because of pole vaulting and inefficient mill reception could be

considerable.

The sharing system, together with the market quota and quedan system, imposes tremendous

administrative work for mills, and the SRA as regulating agency. The sugar produced from each

batch of cane delivered and the share of the planter classified by market in accordance with the

prescribed production quota have to be determined and the corresponding quedans prepared and

issued on a weekly basis.

The sharing system remains because of perceived immediate advantages. While the unfavorable

effects of the sharing system is recognized, the need for substantial working capital to purchase

cane outright discourages the adoption of a direct cane purchase system. Moreover, many mills

and planters are comfortable with sugar sharing because it is one way of sharing risks arising

from the volatility of sugar prices. For planters, the sharing system allows returns that account

for quality differences in cane.

Labor-related Policies

Minimum wages had been legislated at the national level until 1989 when RA 6727 mandated the

latest round of nationwide increase and abolished minimum wage setting at the national level as

it prescribed the fixing of minimum wages by region, province or industry. Following this,

Regional Tripartite Wages and

8

invest evidently accounts for the fact that cane reception in most mills is very inefficient.

Some mills are in fact experimenting on direct cane purchase. At present, the milling contracts

entered into by millers and planters at the start of the sugar crop year to stipulate the raw sugar

sharing arrangement do not essentially follow the formula provided in RA 809. This is an

indication that the millers and planters are aware of the disadvantages of the rigid prices

imposed by the sharingsystem. The apparently increasing cane transport incentives being

granted by mills to farmers further indicate how mills and planters try to get around the

rigidities of the sugar sharing system.

The sharing system created cane supply-demand imbalances within the season. Because the

sugar sharing system is based on the sugar extracted from each batch of cane, all planters want

to deliver cane during the peak of the season when sugar content is highest. Since cane demand

at the mill is even throughout the season, cane ought to be priced higher at the start and end of

the season when supply is low. But the sharing system does not allow a premium for delivering

cane early or late in the season. The planter in fact gets a penalty for delivering early or late

because the sugar content during that time is low. This incentive for everyone to deliver at the

peak of the season contributes to cane reception inefficiencies in the mill.

The sharing system also reduced the farmers' incentive to improve cane quality and adopt more

efficient harvesting methods. On the side of the planters, sharing 30%-40% of the increased

output with the mill reduces their incentive to improve cane quality. The inefficient cane

reception in mills also reduce the farmers' incentive to mechanize harvesting.

The sharing system increases transport costs for mills, the planters, and the industry in general

in three ways:

1 . Where the planter has a choice of mills, he will go to the one giving the higher sugar

share even if it is further away from his farm, i.e. he will polevault, as long as transport

costs do not eat up the additional revenues he derives.

opportunity to. use the resources locked in the'sugar industry more productively.

The quota allocation system reduced the country's returns from the high priced US market. The

proportional sharing by all sugar cane producers and millers of the higher-priced market,

regardless of quality of sugar produced, reduces the industry's returns from the US market. The

mills which produce better quality sugar and get a price premium in the US system can not

increase exports beyond that provided in the allocation system which gives a proportionately

equal allocation to a mill which produces sugar of a quality that gets a price discount in the US

market.

Because of the proportional sharing of the various markets among all

planters/millers, additional production by a small farm would receive the average price for the

various markets instead of the much lower world or reserve price which is really the value of

such additional production to the economy. Thus small farms tend to over-produce as they are

cushioned from the low world or reserve prices. The large firm on the other hand faces a

marginal revenue lower than the average prices and in some cases lower than the world and

reserve price. Producing less thus gives large firms bigger profits.

Cane Marketing

Practices in the cane market further discourage investments for productivity. The norm in the

industry is for millers and planters to share the raw sugar produced by the mills instead of the

mills purchasing the cane for milling. This production sharing system dates back to 1952 when

RA 809 mandated that in the absence of a milling contract, the planters and millers shall share

the sugar in some specified proportion. The proportions are such that the bigger the mill, the

smaller its share of the sugar produced.

The sharing system reduced the incentives to increase milling efficiency. The sugar sharing

system discourages millers from investing to upgrade mill efficiencies. It makes it less profitable

for a mill to invest in enhancing the capability to extract sugar from cane since 60% to 70%

(mandated sugar share of planters) of the increased output will accrue to the planter. This

disincentive to

6

WORLD PRICE VS. PHILIPPINE WHOLESALE PRICE

World Price Philippine Wholesale Price

cli b P/LKG clib

1981 17.15 110.18 12.68

1982 8.38 119.41 12.71

1983 8.49 135.73 11.11

1984 5.16 189.18 10.30

1985 4.04 356.41 17.41

1986 6.05 339.26 15.13

1987 6.72 315.21 13.93

1988 10.17 449.28 18.62

1989 12.79 484.07 20.25

1990 12.55 486.13 18.18

1991 9.04 544.95 18.03

1992 9.09 558.36 19.90

1993 10.03 495.41 16.66

1994 12.12 564.18 19.42

1995 13.88 748.22 26.46

Source: SRA

higher than 40%. Note that the industry produces sugar at about 14 centslib while world

prices are around 1 0-1 1 cents/lb. Sugar importation had been liberalized since 1992 but

sugar imports came in only in 1995 when the MFN tariffs dropped to 50% and ASEAN

imports, which enjoys a 35% margin of preference, were levied only 32.5% tariff.

With the quota allocation, quedaning and regulations on sugar imports, the SRA had been able to

control the supply of sugar in the domestic market. The impact on prices has been that domestic

prices have followed prices in the US quota market and have thus been consistently above world

prices. In 1990 for example, the world price of sugar was P6.71/kilo, the US price P12.44/kilo

and the Philippine wholesale price was P10.00/kilo. In June 1996, Philippine wholesale price

was about P15.00/kilo, the US price P13.28/kilo and the world price was about P6.83/kilo.

The high prices disadvantage the econmy in the following ways:

a. High sugar prices penalized the users. While high domestic prices may appear

advantageous for the sugar industry, it penalizes the sugar users. Given the prices in June

1996, consumers are actually paying double the world price for sugar. This could mean

about P8.00/kilo more in retail prices than what it would have cost consumers if imports

were allowed duty free or about P4.00/kilo more than what price would have been if

imports were allowed with 50% tariff.

b. High domestic prices has adverse consequences downstream industries producing

products that have to compete in the world market. The quota allocation of 'E' sugar for

exporters at world prices tries to correct this but the quota affects the users in much the

same way that import quantitative restrictions do -- prices remain effectively high because

of the transaction cost and only a privileged few are able to avail. Thus, the growth of the

downstream industries has been constricted.

C. High sugar prices tolerates an inefficient industry as it removed the need to lower cost.

The results are less welfare for consumers and foregone

5

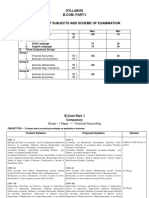

PROMOTING EFFICIENCY IN THE SUGAR INDUSTRY

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Growth Trends 1

Production 1

Hectarage 1

Exports 2

Consumption 2

Sources of Growth 2

Productivity 2

Government Policies 3

Supply Controls 3

Cane Marketing 6

Labor-related Policies 8

CARP 10

Macro Policies 11

Constraints to Modernization

Technology Access and Development 11

Market Development 12

Human resources Development 12

Institutional Framework 12

Credit and Investment 14

Infrastructure Investments 16

Prospects 17

Reform Priorities 18

1

PROMOTING EFFICIENCY

IN THE SUGAR INDUSTRY

by

Beulah de la Pena

for the

Congressional Commission on Agricultural Modernization

You might also like

- Lower - Timeframe - Bullish - Order - FlowDocument30 pagesLower - Timeframe - Bullish - Order - FlowAleepha Lelana100% (5)

- Candy Manufacturing South Invest EthiopiaDocument16 pagesCandy Manufacturing South Invest EthiopiaAbey Doni100% (5)

- Sugarcane FullDocument10 pagesSugarcane Fullcoder1412No ratings yet

- Sugarcane in The PhilippinesDocument4 pagesSugarcane in The PhilippinesShebel AgrimanoNo ratings yet

- Vivek Saraogi BalrampurDocument14 pagesVivek Saraogi BalrampurVaibhav AgrawalNo ratings yet

- Sasa PDFDocument9 pagesSasa PDFAnonymous smFxIR07No ratings yet

- Overview Im6up04zDocument5 pagesOverview Im6up04zHALİM KILIÇNo ratings yet

- Final Version of Feasibility StudyDocument95 pagesFinal Version of Feasibility StudyG.Dennis RambaranNo ratings yet

- Pilot 1 Sugar IndustryDocument23 pagesPilot 1 Sugar IndustryPrafulkumar HolkarNo ratings yet

- Export Process of Sugar: Jagannath International Management School, KalkajiDocument11 pagesExport Process of Sugar: Jagannath International Management School, KalkajiAmit PrakashNo ratings yet

- Problems of Sugar IndustryDocument3 pagesProblems of Sugar IndustrySumit GuptaNo ratings yet

- GROUP 2 SUGAR FinalDocument14 pagesGROUP 2 SUGAR FinalMonica JavierNo ratings yet

- The State of The Jamaican Sugar Industry: Production Statistics 2010 2009 2008 2007 2006Document6 pagesThe State of The Jamaican Sugar Industry: Production Statistics 2010 2009 2008 2007 2006Linda zubyNo ratings yet

- Sugar Industry in Pakistan: - Problems, PotentialsDocument25 pagesSugar Industry in Pakistan: - Problems, PotentialsAtif RehmanNo ratings yet

- Bitter Sugar StoryDocument8 pagesBitter Sugar StoryVincent OryangNo ratings yet

- Syam PrintDocument87 pagesSyam Printsalini_sumanthNo ratings yet

- CSEC Sector Report SugarDocument26 pagesCSEC Sector Report SugarEquity Nest100% (1)

- Sugar Industries of PakistanDocument19 pagesSugar Industries of Pakistanhelperforeu50% (2)

- Chashma Sugar MillsDocument10 pagesChashma Sugar Millssys.fast100% (1)

- Overview of The Sugarcane Industry 21march2016Document4 pagesOverview of The Sugarcane Industry 21march2016Mariela LiganadNo ratings yet

- Issue of Sugar Industry (Sheraz)Document6 pagesIssue of Sugar Industry (Sheraz)Sheraz ArshadNo ratings yet

- Impact of Increasing Sugar Prices On Sugar Demand in India.Document23 pagesImpact of Increasing Sugar Prices On Sugar Demand in India.Rishab Mehta0% (1)

- Rating Methodology-Sugar Sector - December2020Document8 pagesRating Methodology-Sugar Sector - December2020fojoyi2683No ratings yet

- Project FA20-BSE-017Document30 pagesProject FA20-BSE-017M.NadeemNo ratings yet

- Sugarcane Is Grown in 17 Provinces in The CountryDocument21 pagesSugarcane Is Grown in 17 Provinces in The CountryArfe Lanhac RaganasNo ratings yet

- National Sugar Master Plan - A Road Map For Local Sugar Production by Alh. Ahmed SongDocument17 pagesNational Sugar Master Plan - A Road Map For Local Sugar Production by Alh. Ahmed SongUmar Bala UmarNo ratings yet

- Sugar Industry ReportDocument47 pagesSugar Industry ReportRobert RamirezNo ratings yet

- Sugar Industry in IndonesiaDocument24 pagesSugar Industry in IndonesiaGunawan Abdul Basith67% (3)

- Guyana - Fuel EthanolDocument11 pagesGuyana - Fuel Ethanolharoldd2No ratings yet

- Executive SummaryDocument2 pagesExecutive SummaryGautam JainNo ratings yet

- Agribusiness: On International Markets, Agricultural Raw Material Prices Evolved On Diverging Trends. TDocument6 pagesAgribusiness: On International Markets, Agricultural Raw Material Prices Evolved On Diverging Trends. TmouhaidNo ratings yet

- Cost AnalysisDocument81 pagesCost AnalysisPuneeth PaviNo ratings yet

- Fac PB 76 Opportunities Challenges Tanzania's Sugar Industry Lessons For Sagcot and The New Alliance July 2014Document12 pagesFac PB 76 Opportunities Challenges Tanzania's Sugar Industry Lessons For Sagcot and The New Alliance July 2014dennisNo ratings yet

- Inbound Supply Chain Modeling in Sugar IndustryDocument10 pagesInbound Supply Chain Modeling in Sugar Industryrsdeshmukh0% (1)

- Cost Analysis of Shahabad Co-Op Sugar Mills LTDDocument78 pagesCost Analysis of Shahabad Co-Op Sugar Mills LTDVinay ManchandaNo ratings yet

- Sugar in UsDocument7 pagesSugar in UsKiara Flores GuillénNo ratings yet

- International Business (IB) Project Report On Sugar Facor in BrazilDocument34 pagesInternational Business (IB) Project Report On Sugar Facor in BrazilkeyurchhedaNo ratings yet

- Sugar Industry: Presented By: Muhammad Ovais Chhipa Shariq Tanzeem Misha MallickDocument38 pagesSugar Industry: Presented By: Muhammad Ovais Chhipa Shariq Tanzeem Misha MallickOvais ChhipaNo ratings yet

- Kenya SugarDocument19 pagesKenya SugarNashon_AsekaNo ratings yet

- Sugar IndustryDocument37 pagesSugar IndustryRishabh SrivastavaNo ratings yet

- Ghana Cocobod ReportDocument20 pagesGhana Cocobod ReportKookoase KrakyeNo ratings yet

- Budget RenukdDocument57 pagesBudget Renukdsatabache100% (2)

- Causes of Sugar CrisisDocument2 pagesCauses of Sugar CrisisRai ShahzebNo ratings yet

- KPMG Report Exec SummaryDocument19 pagesKPMG Report Exec SummaryNawin KumarNo ratings yet

- ReportDocument16 pagesReportasnashNo ratings yet

- Company ProfileDocument29 pagesCompany ProfileArun GowdaNo ratings yet

- Assessment of Reforms - PH Sugar IndustryDocument13 pagesAssessment of Reforms - PH Sugar IndustryAngeli MarzanNo ratings yet

- Bread Industry in IndiaDocument22 pagesBread Industry in IndiaFarazShaikhNo ratings yet

- 168-Article Text-227-1-10-20130106 PDFDocument12 pages168-Article Text-227-1-10-20130106 PDFAkshayNo ratings yet

- Pest Analysis: Political EnvironmentDocument8 pagesPest Analysis: Political Environmentzara aliNo ratings yet

- Chapter IIIDocument41 pagesChapter IIIElayaraja ThirumeniNo ratings yet

- Sugar Sector Sept 2011Document10 pagesSugar Sector Sept 2011Nehemia Danielson KaayaNo ratings yet

- Makro EkonomiDocument2 pagesMakro EkonomirdimasbanyadhimanNo ratings yet

- Sugar IndustryDocument34 pagesSugar IndustryMuhammad Irteza Sultan100% (1)

- Candy PDFDocument16 pagesCandy PDFGourav Tailor100% (1)

- SM Sugar Industry Group9Document3 pagesSM Sugar Industry Group9Abhishek Dalal100% (1)

- Tongaat - Annual Report 2011Document127 pagesTongaat - Annual Report 2011Lungisani MkhizeNo ratings yet

- Food Outlook: Biannual Report on Global Food Markets July 2018From EverandFood Outlook: Biannual Report on Global Food Markets July 2018No ratings yet

- Food Outlook: Biannual Report on Global Food Markets May 2019From EverandFood Outlook: Biannual Report on Global Food Markets May 2019No ratings yet

- The State of Agricultural Commodity Markets 2018: Agricultural Trade, Climate Change and Food SecurityFrom EverandThe State of Agricultural Commodity Markets 2018: Agricultural Trade, Climate Change and Food SecurityNo ratings yet

- Criminal Law Case DigestsDocument10 pagesCriminal Law Case DigestsDiane UyNo ratings yet

- Juno Batistis vs. People of The Philippines, G.R. No. 181571 December 16, 2009Document2 pagesJuno Batistis vs. People of The Philippines, G.R. No. 181571 December 16, 2009Diane UyNo ratings yet

- When Republication Is Not Needed in Cases of Amended Petition For RegistrationDocument3 pagesWhen Republication Is Not Needed in Cases of Amended Petition For RegistrationDiane UyNo ratings yet

- Comm LMTDocument5 pagesComm LMTDiane UyNo ratings yet

- Tax Doctrines in Dimaampao CasesDocument3 pagesTax Doctrines in Dimaampao CasesDiane UyNo ratings yet

- Halley vs. Printwell: DoctrineDocument2 pagesHalley vs. Printwell: DoctrineDiane UyNo ratings yet

- Commercial Law FaqsDocument30 pagesCommercial Law FaqsDiane UyNo ratings yet

- TAX CASE MV Don Martin vs. Secretary of FinanceDocument1 pageTAX CASE MV Don Martin vs. Secretary of FinanceDiane UyNo ratings yet

- Comsavings Bank (Now Gsis Family Bank) vs. Spouses Danilo and Estrella Capistrano G.R. No. 170942 August 28, 2013Document2 pagesComsavings Bank (Now Gsis Family Bank) vs. Spouses Danilo and Estrella Capistrano G.R. No. 170942 August 28, 2013Diane UyNo ratings yet

- Christmas Game 2016Document8 pagesChristmas Game 2016Diane UyNo ratings yet

- Stronghold Insurance CompanyDocument2 pagesStronghold Insurance CompanyDiane UyNo ratings yet

- New Frontier SugarDocument3 pagesNew Frontier SugarDiane UyNo ratings yet

- Ponce Vs Alsons CementDocument3 pagesPonce Vs Alsons CementDiane UyNo ratings yet

- V. Loyola Grand VillasDocument2 pagesV. Loyola Grand VillasDiane UyNo ratings yet

- Sobrejuanite Vs AsbDocument3 pagesSobrejuanite Vs AsbDiane Uy100% (1)

- Pale Privileged CommunicationDocument9 pagesPale Privileged CommunicationDiane UyNo ratings yet

- Korean Technologies v. LermaDocument2 pagesKorean Technologies v. LermaDiane UyNo ratings yet

- Ferdinand Cruz vs. Alberto Mina GR No. 154207 April 27, 2007 FactsDocument5 pagesFerdinand Cruz vs. Alberto Mina GR No. 154207 April 27, 2007 FactsDiane UyNo ratings yet

- Pale Privileged CommunicationDocument9 pagesPale Privileged CommunicationDiane UyNo ratings yet

- Corporation Law 1st BatchDocument15 pagesCorporation Law 1st BatchDiane UyNo ratings yet

- TAX CASES Assignment 1Document26 pagesTAX CASES Assignment 1Diane UyNo ratings yet

- Syllabus Grouping of Subjects and Scheme of ExaminationDocument29 pagesSyllabus Grouping of Subjects and Scheme of ExaminationAbhisek AgrawalNo ratings yet

- Aptitude Test 2Document8 pagesAptitude Test 2Manisha ArsuleNo ratings yet

- Deregulation of The Petroleum Sector JournalDocument67 pagesDeregulation of The Petroleum Sector Journalolaleye samuel olasodeNo ratings yet

- Routific Food Delivery EbookDocument37 pagesRoutific Food Delivery EbookTade Faweya100% (1)

- Disbursement Voucher: Alita B. Atillo Asuncion C. Palad Eddie Richard R. LagnadaDocument8 pagesDisbursement Voucher: Alita B. Atillo Asuncion C. Palad Eddie Richard R. LagnadaRosita Dumanat Asperin CondeNo ratings yet

- Why The Monopolist Firm Earn Supernormal Profits in The Long RunDocument13 pagesWhy The Monopolist Firm Earn Supernormal Profits in The Long RunArjun AulNo ratings yet

- BudgetingDocument130 pagesBudgetingRevathi AnandNo ratings yet

- Water Pricing in Water SupplyDocument8 pagesWater Pricing in Water SupplySuwash AcharyaNo ratings yet

- Prof. Sam.: Prof. Indrawansa Samaratunga PHD, DSCDocument3 pagesProf. Sam.: Prof. Indrawansa Samaratunga PHD, DSCKoshy ThankachenNo ratings yet

- ShuttleDocument16 pagesShuttleyogesh tripathiNo ratings yet

- QA 06 Arithmetic-2 QDocument32 pagesQA 06 Arithmetic-2 QAnuj Anuj AjmeriyaNo ratings yet

- Muhammad Elfan Budi Nugroho 29118399 - Midterm TestDocument2 pagesMuhammad Elfan Budi Nugroho 29118399 - Midterm TestKemal Al ZaroNo ratings yet

- Final Proposal (Chee)Document13 pagesFinal Proposal (Chee)Faraliza JumayleezaNo ratings yet

- Padhle 11th - 8 - Producer's Equilibrium - Microeconomics - EconomicsDocument5 pagesPadhle 11th - 8 - Producer's Equilibrium - Microeconomics - EconomicsRushil ThindNo ratings yet

- Alternative Investments and StrategiesDocument414 pagesAlternative Investments and StrategiesJeremiahOmwoyoNo ratings yet

- Project Report of Capital MarketDocument25 pagesProject Report of Capital MarketRohit JainNo ratings yet

- Chapter 04 TestbankDocument49 pagesChapter 04 TestbankYazmine Aliyah A. CaoileNo ratings yet

- Question of Planning of Working CapitalDocument2 pagesQuestion of Planning of Working CapitalSalman IrshadNo ratings yet

- Chapter 14 - AnswerDocument17 pagesChapter 14 - AnswerJhudzxkie VhientesaixNo ratings yet

- August 19Document48 pagesAugust 19fijitimescanadaNo ratings yet

- IEOR 221 s2016 Homework 1Document2 pagesIEOR 221 s2016 Homework 1Suman BalaNo ratings yet

- Antique's Morning Presentation - 200324 - EbrDocument17 pagesAntique's Morning Presentation - 200324 - EbramarjeetNo ratings yet

- Ginger & Jagger Price List 2012Document7 pagesGinger & Jagger Price List 2012yv8657No ratings yet

- Case 1Document17 pagesCase 1Paula de leonNo ratings yet

- New Product Development (NPD) and Product Life Cycle (PLC) StrategiesDocument4 pagesNew Product Development (NPD) and Product Life Cycle (PLC) StrategiesKanganFatimaNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1, Business MathDocument12 pagesChapter 1, Business MathSopheap CheaNo ratings yet

- Economic Analysis of Industrial Projects 3Rd Edition Full ChapterDocument41 pagesEconomic Analysis of Industrial Projects 3Rd Edition Full Chapterphilip.prentice386100% (25)

- Jasch, Christine. The Use of Environmental Management Accounting (EMA) For Identifying Environmental CostsDocument11 pagesJasch, Christine. The Use of Environmental Management Accounting (EMA) For Identifying Environmental CostsTitoHeidyYantoNo ratings yet

- FMCG SectorDocument3 pagesFMCG SectorJatin JaisinghaniNo ratings yet