Professional Documents

Culture Documents

San Krit Ization

San Krit Ization

Uploaded by

Akshat Kumar SinhaCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- Masterplan TemplateDocument72 pagesMasterplan TemplateMostafa FawzyNo ratings yet

- Society Against the State: Essays in Political AnthropologyFrom EverandSociety Against the State: Essays in Political AnthropologyRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (31)

- Order and Chivalry: Knighthood and Citizenship in Late Medieval CastileFrom EverandOrder and Chivalry: Knighthood and Citizenship in Late Medieval CastileNo ratings yet

- 669560Document22 pages669560KT GaleanoNo ratings yet

- PHD Progress Presentation TemplateDocument11 pagesPHD Progress Presentation TemplateAisha QamarNo ratings yet

- Sanskritization and Westernizationa - A Dynamic View - HAROLD GOULDDocument7 pagesSanskritization and Westernizationa - A Dynamic View - HAROLD GOULDAvinash PandeyNo ratings yet

- Chapter Four - Tradition and ModernityDocument37 pagesChapter Four - Tradition and ModernityWahhabbxss13No ratings yet

- Race, Amnesia, and The Education of International RelationsDocument14 pagesRace, Amnesia, and The Education of International RelationsVinay PaiNo ratings yet

- Sanskritisation: A P BarnabasDocument6 pagesSanskritisation: A P Barnabasjatin kumarNo ratings yet

- Dalit BodyDocument19 pagesDalit Bodypujasarmah806No ratings yet

- Lugones Heterosexualism and The Colonial Modern Gender SystemDocument25 pagesLugones Heterosexualism and The Colonial Modern Gender SystemPrismNo ratings yet

- The Proceedings of The American Ethnological SocietyDocument4 pagesThe Proceedings of The American Ethnological SocietysammycatNo ratings yet

- Lugones HeterosexualismColonial 2007Document25 pagesLugones HeterosexualismColonial 2007franciscatoledocNo ratings yet

- Caste and CastelessnessDocument8 pagesCaste and CastelessnessJayanth TadinadaNo ratings yet

- Rhetoric Against Age of Consent - Resisting Colonial Reason and Death of A Child-Wife - SarkarDocument11 pagesRhetoric Against Age of Consent - Resisting Colonial Reason and Death of A Child-Wife - SarkarAlex WolfersNo ratings yet

- Heterosexualism and The Colonial Modern Gender SystemDocument25 pagesHeterosexualism and The Colonial Modern Gender SystemQaima HossainNo ratings yet

- Caste and Castelessness in The Indian Republic by Satish DeshpandeDocument10 pagesCaste and Castelessness in The Indian Republic by Satish DeshpandeAbhishek ShawNo ratings yet

- Liminal It yDocument10 pagesLiminal It ylewis_cynthiaNo ratings yet

- Matriliny and Patriliny Between Cohabitation-Equilibrium and Modernity in The Cameroon GrassfieldsDocument40 pagesMatriliny and Patriliny Between Cohabitation-Equilibrium and Modernity in The Cameroon GrassfieldsNdong PeterNo ratings yet

- Syncretism and Its Synonyms ReflectionsDocument23 pagesSyncretism and Its Synonyms ReflectionsMuhammad Ibrahim KhokharNo ratings yet

- The Middle Men, An Introduction To The Transmasculine Identities+Document25 pagesThe Middle Men, An Introduction To The Transmasculine Identities+juaromerNo ratings yet

- Is Female To Male As Nature Is To Culture - OrtnerDocument28 pagesIs Female To Male As Nature Is To Culture - Ortnermoñeco azulNo ratings yet

- Sherry B. Ortner - Is Female To Male As Nature Is Tu Culture (Rosaldo & Lamphere, 1974)Document21 pagesSherry B. Ortner - Is Female To Male As Nature Is Tu Culture (Rosaldo & Lamphere, 1974)P. A. F. JiménezNo ratings yet

- Goettner-Abendroth, H. - Rethinking 'Matriarchy' in Modern Matriarchal Studies Using Two Examples. The Khasi and The MusuoDocument26 pagesGoettner-Abendroth, H. - Rethinking 'Matriarchy' in Modern Matriarchal Studies Using Two Examples. The Khasi and The MusuoP. A. F. JiménezNo ratings yet

- Sherry B. Ortner - Is Female To Male As Nature Is To CultureDocument28 pagesSherry B. Ortner - Is Female To Male As Nature Is To Culturelauraosigwe11No ratings yet

- Stewart-Syncretism and Its SynonymsDocument24 pagesStewart-Syncretism and Its SynonymshisjfNo ratings yet

- Freedom and CultureDocument128 pagesFreedom and CultureParang GariNo ratings yet

- Social ClassesDocument19 pagesSocial Classesraheel_uogNo ratings yet

- Pieces of Self - Anarchy, Gender and Other ThoughtsDocument22 pagesPieces of Self - Anarchy, Gender and Other ThoughtsSilviu PopNo ratings yet

- Notes On Passage: The New International of Sovereign Feelings - Fred MotenDocument25 pagesNotes On Passage: The New International of Sovereign Feelings - Fred MotenGrawpNo ratings yet

- The Religion of Socialism: Being Essays in Modern Socialist CriticismFrom EverandThe Religion of Socialism: Being Essays in Modern Socialist CriticismNo ratings yet

- Black Women Under State: Surveillance, Poverty & The Violence of Social AssistanceFrom EverandBlack Women Under State: Surveillance, Poverty & The Violence of Social AssistanceNo ratings yet

- 3 Society and Politics in India2Document12 pages3 Society and Politics in India2Aditya SanyalNo ratings yet

- Patil - From Patriarchy To IntersectionalityDocument22 pagesPatil - From Patriarchy To IntersectionalityNuzhat Ferdous IslamNo ratings yet

- A Manifesto in Four Themes: Rita Laura SegatoDocument14 pagesA Manifesto in Four Themes: Rita Laura SegatoTango1680No ratings yet

- How To Be Political. Art Activism, Queer PracticesDocument15 pagesHow To Be Political. Art Activism, Queer PracticesEliana GómezNo ratings yet

- Sherry B. Ortner - Is Female To Male As Nature Is To Culture - READING HIGHLIGHTEDDocument12 pagesSherry B. Ortner - Is Female To Male As Nature Is To Culture - READING HIGHLIGHTEDShraddhaNo ratings yet

- The Fragmentary City: Migration, Modernity, and Difference in the Urban Landscape of Doha, QatarFrom EverandThe Fragmentary City: Migration, Modernity, and Difference in the Urban Landscape of Doha, QatarNo ratings yet

- Yawnie - Comments On The Spiritual Baptist and Shango Papers Edited by Stephen D. GlazierDocument7 pagesYawnie - Comments On The Spiritual Baptist and Shango Papers Edited by Stephen D. GlazierArielNo ratings yet

- (15585816 - Theoria) Religious Origins of Modern RadicalismOCR PDFDocument30 pages(15585816 - Theoria) Religious Origins of Modern RadicalismOCR PDFFredericoDaninNo ratings yet

- College of Asia and The Pacific, The Australian National UniversityDocument27 pagesCollege of Asia and The Pacific, The Australian National UniversityAlice SheddNo ratings yet

- Culture and ColonialismDocument18 pagesCulture and ColonialismJudhajit SarkarNo ratings yet

- Susan PhilipDocument19 pagesSusan PhilipeἈλέξανδροςNo ratings yet

- Peter D. Hershock, Roger T. Ames Confucian Cultures of Authority Suny Series in Asian Studies Development 2006Document278 pagesPeter D. Hershock, Roger T. Ames Confucian Cultures of Authority Suny Series in Asian Studies Development 2006Guillermo Garcia VenturaNo ratings yet

- Contact Zone: Ethnohistorical Notes On The Relationship Between Kings and Tribes in Middle IndiaDocument26 pagesContact Zone: Ethnohistorical Notes On The Relationship Between Kings and Tribes in Middle Indiaarijeet.mandalNo ratings yet

- Dalit, Modernity and Metamorphosis of CastesDocument21 pagesDalit, Modernity and Metamorphosis of CastesAnand TeltumbdeNo ratings yet

- Queer - Migration, An Unruly Body of Scholarship - Eithne LuibheidDocument23 pagesQueer - Migration, An Unruly Body of Scholarship - Eithne LuibheidDiego Prieto OlivaresNo ratings yet

- Rhetoric Against Age of Consent. Resisting Colonial Reason and Death of A Child-WifeDocument11 pagesRhetoric Against Age of Consent. Resisting Colonial Reason and Death of A Child-WifehiringagentheroNo ratings yet

- 6 The Nation and Its QueersDocument22 pages6 The Nation and Its QueersJonah LegoNo ratings yet

- From Lineage To State Social Formations in The Mid First Mellennium B. C. in The Ganga Valley by Romila ThaparDocument3 pagesFrom Lineage To State Social Formations in The Mid First Mellennium B. C. in The Ganga Valley by Romila ThaparNandini1008100% (2)

- Muslim Loyalty and BelongingDocument18 pagesMuslim Loyalty and BelongingArdit KrajaNo ratings yet

- The Aith Waryaghar of The Moroccan Rif ADocument3 pagesThe Aith Waryaghar of The Moroccan Rif AFerdaousse BerrakNo ratings yet

- Avtar Brah - Questions of Difference and International FeminismDocument7 pagesAvtar Brah - Questions of Difference and International FeminismJoana PupoNo ratings yet

- How Public Was SaivismDocument46 pagesHow Public Was SaivismJoão AbuNo ratings yet

- Heelas Transpersonal Pakistan IJTS 32-2Document13 pagesHeelas Transpersonal Pakistan IJTS 32-2International Journal of Transpersonal StudiesNo ratings yet

- Turner, Liminality and CommunitasDocument20 pagesTurner, Liminality and CommunitasAaron Kaplan100% (1)

- Gender and Civil Society - An Interview With Suad JosephDocument5 pagesGender and Civil Society - An Interview With Suad JosephM. L. LandersNo ratings yet

- SSRN Id4426489Document11 pagesSSRN Id4426489aishaNo ratings yet

- Dynamics of Swaps SpreadsDocument32 pagesDynamics of Swaps SpreadsAkshat Kumar SinhaNo ratings yet

- VA+Tech+Wabag Inititating+coverageDocument32 pagesVA+Tech+Wabag Inititating+coverageAkshat Kumar Sinha0% (1)

- Customer Perception Towards TupperwareDocument6 pagesCustomer Perception Towards TupperwareAkshat Kumar Sinha100% (1)

- Niranjan - A Page From History - 70 Years Before The Brics Bank - 230714Document2 pagesNiranjan - A Page From History - 70 Years Before The Brics Bank - 230714Akshat Kumar SinhaNo ratings yet

- Judicial Meanderings in Patriarchal Thickets Litigating Sex Discrimination in IndiaDocument11 pagesJudicial Meanderings in Patriarchal Thickets Litigating Sex Discrimination in IndiaAkshat Kumar SinhaNo ratings yet

- Journal of Pediatric Surgery: Ibrahim UygunDocument4 pagesJournal of Pediatric Surgery: Ibrahim UygunNur Ainatun NadrahNo ratings yet

- Psychoanalysis: ArticleDocument21 pagesPsychoanalysis: ArticleAqsa ParveenNo ratings yet

- Project Report On Customer Satisfaction Towards LGDocument52 pagesProject Report On Customer Satisfaction Towards LGrajasekar100% (2)

- Rambabu Singh Thakur v. Sunil Arora & Ors. (2020 3 SCC 733)Document4 pagesRambabu Singh Thakur v. Sunil Arora & Ors. (2020 3 SCC 733)JahnaviSinghNo ratings yet

- Unit 10: Sitcom: Tonight, I'm CookingDocument3 pagesUnit 10: Sitcom: Tonight, I'm CookingDaissy FonsecaNo ratings yet

- Genrich Altshuller-Innovation Algorithm - TRIZ, Systematic Innovation and Technical Creativity-Technical Innovation Center, Inc. (1999)Document290 pagesGenrich Altshuller-Innovation Algorithm - TRIZ, Systematic Innovation and Technical Creativity-Technical Innovation Center, Inc. (1999)Dendra FebriawanNo ratings yet

- Las Castellana BananaDocument28 pagesLas Castellana BananajerichomuhiNo ratings yet

- 1.5 Introducing Petty Cash Books: Suggested ActivitiesDocument2 pages1.5 Introducing Petty Cash Books: Suggested ActivitiesDonatien Oulaii100% (2)

- Summary of VivekachudamaniDocument3 pagesSummary of VivekachudamaniBr SarthakNo ratings yet

- Royal Halloway University - Google SearchDocument1 pageRoyal Halloway University - Google SearchMasoomaIjazNo ratings yet

- RHPA46 FreeDocument5 pagesRHPA46 Freeheyimdee5No ratings yet

- Gas Supply Agreement 148393.1Document5 pagesGas Supply Agreement 148393.1waking_days100% (1)

- Division) Case No. 7303. G.R. No. 196596 Stemmed From CTA en Banc Case No. 622 FiledDocument16 pagesDivision) Case No. 7303. G.R. No. 196596 Stemmed From CTA en Banc Case No. 622 Filedsoojung jungNo ratings yet

- Research in Organizational Behavior: Sabine SonnentagDocument17 pagesResearch in Organizational Behavior: Sabine SonnentagBobby DNo ratings yet

- 86% Strike - 97% Stop Loss - 2 Months - EUR: Bullish Mini-Futures On The German Stock Index Future of June 2010Document1 page86% Strike - 97% Stop Loss - 2 Months - EUR: Bullish Mini-Futures On The German Stock Index Future of June 2010api-25889552No ratings yet

- Chemical Analysis of Caustic Soda and Caustic Potash (Sodium Hydroxide and Potassium Hydroxide)Document16 pagesChemical Analysis of Caustic Soda and Caustic Potash (Sodium Hydroxide and Potassium Hydroxide)wilfred gomezNo ratings yet

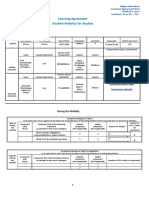

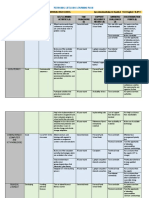

- Learning Agreement During The MobilityDocument3 pagesLearning Agreement During The MobilityVictoria GrosuNo ratings yet

- Architecture FormsDocument57 pagesArchitecture FormsAymen HaouesNo ratings yet

- 723PLUS Digital Control - WoodwardDocument40 pages723PLUS Digital Control - WoodwardMichael TanNo ratings yet

- Cola - PestelDocument35 pagesCola - PestelVeysel100% (1)

- Question Bank & Answers - PoetryDocument4 pagesQuestion Bank & Answers - PoetryPrabhjyot KaurNo ratings yet

- Federal Resume SampleDocument5 pagesFederal Resume Samplef5dq3ch5100% (2)

- FMGE Recall 1Document46 pagesFMGE Recall 1Ritik BhardwajNo ratings yet

- Personal Lifelong Learning PlanDocument7 pagesPersonal Lifelong Learning PlanRamilAdubal100% (2)

- Idoc - Pub Magic Sing Et25k Song List EnglishDocument30 pagesIdoc - Pub Magic Sing Et25k Song List EnglishFlorentino EsperaNo ratings yet

- Go Out in The World - F - Vocal ScoreDocument3 pagesGo Out in The World - F - Vocal ScoreParikNo ratings yet

- Electrical Energy by Dhanpat RaiDocument5 pagesElectrical Energy by Dhanpat RaiDrAurobinda BagNo ratings yet

- Appendix B For CPPDocument1 pageAppendix B For CPP16 Dighe YogeshwariNo ratings yet

San Krit Ization

San Krit Ization

Uploaded by

Akshat Kumar SinhaOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

San Krit Ization

San Krit Ization

Uploaded by

Akshat Kumar SinhaCopyright:

Available Formats

An attempt has been made fie re to show that there may be a dynamic interplay between the processes

of Sanskritization and westernization which may help us to account for such seeming anachronisms as the

high castes, who have had the greatest shake in the old order, revealing a stronger urge for westernization

and modernisation than the tower castes, who have had the least stake in the old order,

This is just the opposite of what we have been led to expect on the basis of 'classical' accounts of

modernisation.

The process of westernization need not be regarded as an ' irony' but is an important dimension of

the total process of mobility and change in Indian society.

THE observation that the I ndi an

caste system is not absolutely

r i gi d and static has l e d progressive-

ly to vari ous attempts to expl ai n in

systematic terms the manner in

whi ch change occurs wi t hi n i t . Per-

haps the earliest such altenipt was

the observation that a caste may

sometimes pay large dowries to

give its daughters in marri age to

men of some sl i ght l y hi gher caste.'

Thi s is the process known as hvper-

gamy/" ft has been described and

discussed by al l of the wel l - known

ethnographers of I ndi a who wrot e

dur i ng the last cent ury and the

first-part of this century. It forms

a maj or preoccupat i on of J H Hut-

ton' s wor k ( 1946) .

I mpl i ci t in this concept of hyper-

gamy is the fact that cash's who

for any reason are able to become

upwar dl y mobi l e do so by maki ng

themselves r i t ual I y and occupa-

l i onai l y as much like the higher

castes as possible and then rat i fy-

i ng this achievement by appl yi ng

t hei r newl y-found resources to the

cont ract i ng of up-marri ages. Once

i nt er mar r i ed wi t h another caste

gr oup, yon are i nconl esl ahl y equal

to i t . Thi s has always been the

fi nal cr i t er i on of status par i t y i n

t r adi t i onal I ndi an society.

Sanskritization the Concept

However, upwar d mobi l i t y, even

in the caste system, is a broader,

mor e pervasive process than is

symbol i zed by the practice of hy-

pergamy. The latter may. as a

matter of fact, lie seen more as a

ki nd of end-product of the overall

process, an aspect of the whol e

phenomenon and not hi ng more. It

in the great ut i l i t y of M N Srinivas' s

( 1056) concept of Sanskri t i zat i on

that i t aut omat i cal l y puts hyper-

gamy i n its appr opr i at e place

wi t hi n an overal l process of inter-

caste mobi l i t y whi ch encompasses

not only this act of final rat i fi ca-

t i on but also all of the intermediate

steps and, indeed, other channels

and manifestations of mobi l i t y as

well whi ch do not necessarily cul -

mi nat e in hypergamy at al l .

Srinivas' s concept rests ultimate-

ly ou the notion that the caste sys-

tem, l i ke al l status hierarchies,

causes the low to i nvi di ousl y com-

pare themselves wi t h the hi gh and

to try in every way they can to

soften, modi fy, reduce, and even

el i mi nat e altogether the basis for

these status differences. Thi s is not

uni que to the I ndi an caste system.

What is uni que is the manner in

whi ch this process must work itself

out in Indi a, gi ven the empi r i cal

nature of the status system that

prevails there. It is t hi s wi t h whi ch

Sanskr i t i / at i on comes to gri ps.

Sanskri t i zat i on also, it seems to

me. deals wi i h something a l i t t l e

different than Mc Ki m Ma r r i ot t s

(1955) uni versal i zat i on parochi a-

l i zat i on' di chot omy. The former

subsumes, essentially the same phe-

nomena as the latter but uses them

for different anal yt i cal ends. Mar -

ri ot t ' s notion is more par t i cul ar l y

useful for deal i ng wi t h data of this

ki nd when it is being viewed f r om

the standpoint of a fol k-urban d i -

mension where one may be concern-

ed wi t h the process of i nt er mi ngl i ng

between elite, urban-centered, and

l ocal , vi l l ager-ent ered cul t ur al tra-

di t i ons, qui t e aside from the ques-

t i on of the status i mpl i cat i ons of

this per se Srinivas' s concept is

rooted pr i mar i l y in a concern f or

the latter.

But Sri ni vas also speaks of a

paral l el process, whi ch he terms

westernization. Concerni ng this be

observes :

One of the many interesting contra-

dictions of modern Hindu social life

945

is that while the Brahmans are be-

coming: more and more westernized,

the other castes are becoming more

and more Sanskritized. In the lower

reaches of the hierarchy, castes are

faking up customs which the Hrah-

nians are busy discarding. As far us

these castes are concerned, it looks as

though Sanskritization is an essential

preliminary to westernization.

Dynamic Relationship

However. I believe we can go

fart her wi t h this not i on of Sr i -

nivas" s ami thereby deepen our

underst andi ng of the mobi l i t y pr o-

cess in I ndi an society today. For

it seems: probabl e that at least in

some instances, under some ci rcum-

stances the rel at i onshi p between

Sanskri t i zat i on and westernization

is a more dynami c one than even

Sri ni vas makes apparent in his

wr i t i ngs.

Let us realize at the outlet that

the caste system is one of the most

elaborate attempts at hi erarchi za-

fi on of society ever undert aken by

matt. It has left its mark every-

where on I ndi an l i f e, but especial-

ly it has i mbued Indi ans in general

wi t h a finely tuned consciousness of

hi er ar chy per se whi ch does not

seem to be di sappeari ng wi t h any

par t i cul ar haste even among the

most moderni zed, westernized of

Indi ans. Among the l at t er. this

sense of hi er ar chy merely changes

its contours sl i ght l y so that it can

operate effectively even under con-

di t i ons of so-called democrat i c so-

ci et y. At t ent i on t o seni or i t y and

petty permut at i ons of aut hor i t y are

admi t t ed by al l to be unusually ela-

borated even in the most ' r at i onal '

and ' progressive" I ndi an bureaucra-

ci es The academic wor l d, where

one mi ght expect the most moder-

n i s e t hi nki ng t o be appl i ed i n

such matters is not ori ousl y hierar-

chized not onl y wi t h respect to the

official uni ver si t y structures hut

wi t h respect as wel l to the i nf or mal

Sanskritization and Westernization

A Dynamic View

June 24, 1961

T H E E C O N O M I C W E E K L Y

Harold A Gould

June 24 1961

T H E E C O N O M I C W E E K L Y

social structures mai nt ai ned by

students and faculty alike. The

charge of "casteism on the campus

is so loud and frequent in Indi a

that its very persistence and uni -

versality makes it almost i naudi bl e.

It is wi t hi n this setting of perva-

sive hi erarchi cal t hi nki ng and

feeling that the interdependency of

Sanskri t i zat i on and westernization

may he appreciated. Sri ni vas has

looked at these t wi n processes to an

i mport ant degree from the stand-

point of the desire of the l ower

castes to move upwar d by trans-

f or mi ng their ri t ual and social

structure unt i l it conforms more

nearly to that of the Brahmana

and/ or whatever other caste hap-

pens to be domi nant and, therefore,

represents elite status wi t hi n t hei r

experi ent i al ken. West erni zat i n,

then, is seen pr i ma r i l y as an ' i r ony'

by . whi ch the very clean castes

whom the lower castes arc api ng

are gi vi ng up the very Sanskritic

traits by whi ch the lower castes i m-

pl i ci t l y acknowledge ( by t r yi ng t o

adopt them) their super i or i t y.

Westernization a Necessity

It is my suspicion that this hitter

is more than an i rony and act ual l y

a new and necessary manifestation

for the hi gh castes of the age-old

preoccupation of people in general

and Indians i n par t i cul ar wi t h

hi erarchy. Thi s poi nt is to he ap-

preciated when we view Sansjkrili-

zation and westernization f r om the

standpoint of those who are at the

top of the scab the Brahmans

and certain others rather than

f r om the standpoint of those locat-

ed at its bot t om or somewhere in

its mi ddl e reaches.

i f you are t r adi t i onal l y Brahman

and you are at the apex of the r i -

t ual hi erarchy prevalent i n a v i l l -

age, or in a regi on wherein the

approxi mat e or der i ng of the vari -

ous castes is reasonably compre-

hended by most and acknowledged

more or less as the basis of social

i nt eract i on, then Sanskri t i zat i on for

you means wat chi ng the lower cas-

tes rising up and up beneath you.

As they "o so, by whi ch I mean,

as and to the extent that they are

able to actually force recogni t i on

of and thereby r at i f y new status

pretensions, the social distance bet-

ween them and you is di mi ni shed.

Years ago, when I first came to

Sherupur

4

t hi s seemed to be the

pl i ght and the compl ai nt of both

the Raj put and the Br ahman mem-

bers of the communi t y. Democrat i -

zation of I ndi an society, part i cul ar-

ly since Independence, has opened

up opport uni t i es heretofore incon-

ceivable for Ahi r . Mur au, Ku r mi ,

Kor i and even Chamar castes to

Sanskritize themselves; ( i e , t o pur i -

fy their ri t ual s, diet, etc) and in

general to approach and fraternize

wi t h I he hi gh castes. Understandab-

l y, these long-suppressed and vary-

i ngl y humi l i at ed groups have been

busy doi ng just that. In fact, I

suggest that one of the pr i me

motive-forces behind San.skritiza-

l i on is this factor of repressed

host i l i t y whi ch manifests itself not

in the f or m of rejecting the caste

system but in the form of its vic-

t i ms t r yi ng to seize cont r ol of it

and thereby expiate t hei r frustra-

tions on the same battlefield where

they acqui red them. Onl y then

can there he a sense of satisfaction

in something achieved that is tangi-

ble, concrete, and relevant to past

experience. If the lower castes re-

jected the caste system out of band

before acting out their hostilities to

it by t r yi ng to master it they woul d

be left wi t h a hollow sense of nn-

f ul f i l l ment , a sense that they never

successfully attacked and conquered

the t hi ng i n terms of whi ch t hei r

ideals, their aspirations, their frus-

trations, in fact their whole percep-

tion of l i fe, were f or med. Besides

this, it is doubt ful that they coul d

structure t hei r hostilities and aspi-

rat i ons in any other way as yet

because of the very fact thai they

have remained throughout recorded

Indi an history i l l i t erat e, cowed pr i -

soners of the caste system. Thei r

perception of alternative forms

must by defi ni t i on he di m and i n-

decisive.

Old Bases of Power Crumble

Thus, at any rate in 1954, the

Brahmans and Rajputs of Sherupur

were, speaking to me bi t t er l y about

the fust-approaching * rul e of the

lower orders' ' In the presence of

lower caste persons they woul d

declare that in the ' ol d days' a

lower caste man woul d never dare

come as close to a Raj put ' s or

Brahman' s charpai as in fact his

listeners were comi ng at the present

moment ! Today, respect (izzat)

for the hi gh caste man has ended,'

my i nformant s woul d l oudl y pro-

cl ai m. When some Kor i s obtained

funds f r om a nearby Communi t y

Projact t r ai ni ng bl ock to . construct

946

a new wel l , the Raj put s regul arl y

stood a t o m f l i ngi ng taunts at t hem

for pl aci ng t hei r t rust i n outside

agencies ( uni f or ml y labelled ' Gov-

ernment ' ) who, they averred, woul d

ul t i mat el y betray them and make

fools of t hemi n cont radi st i nct i on

to the Rajputs, of course, who, they

assured me, had always scrupu-

lously looked after the interests of

their lower caste bretheren.

For the Brahmans and Rajputs,

it was clearly a matter of seeing

the bases of t hei r ol d power and

aut hor i t y mel t i ng away before t l u i r

eyes and being prevented from do-

i ng much about i t , as indeed they

could in the ' ol d days,' by the i m-

par t i al hand, of secular govern-

ment ". Or looked at f r om the poi nt

of view of the thesis bei ng enun-

ciated here, these hi gh castes were

wat chi ng anxi ousl y whi l e the floor

of the status system rose under-

neath them wi t h the consequence

that the old forms of social distance

by wi nch they bai l always differen-

tiated themselves f r om their fellow-

Hi ndus were evaporat i ng. As Sr i -

nivas puts it :

The three main axes of power in

the caste system fire die ritual, the

economic, and the political ones, and

the possession of power in any one

sphere usually leads to power in the

other two.

The Brahmans and Rajputs of

Sherupur were losing their pol i t i -

cal and to some extent their econo-

mi c power " t hrough whi ch for

centuries they had successfully en-

forced the t r adi t i onal hi erarchi cal

or der i ng of the castes and the r i t ual

distinctions upon whi ch this was

based. In fact, the pol i t i cal coup

de grace was delivered in February

l abour on part -t i me basis or fa-

of 1961 when for the first t i me

secret-ballot elections were hel d for

the office of village pradhan. Wi t h

the election nf an Ahi r , the peren-

ni al cont rol mai nt ai ned by the

Rajputs, and acquiesced in by the

Brahmans,

7

was decisively shatter-

ed. The mi ddl e and lower castes

were j ubi l ant , their attitude bei ng

vi vi dl y i l l ust rat ed by the comment

of a Ko r i f r i end, who said wi t h

real emot i on in his voice, ' The

l ower castes are comi ng up now. '

For they saw in this pol i t i cal vi ct o-

ry the possi bi l i t y of a widened

scope for the eventual at t ai nment

of status par i t y wi t h the Brahmans

and Raj put s a par i t y whi ch my

experience wi t h these vi l l agers has

demonstrated to me is associated, as

THE ECONOMIC WEEKLY June 24, 1961

srinivas says, wi t h the desire to

become ever more ort hodox and

' clean' i n the r i t ua l , commensal,

and connubi al senses.

Where Westernization Comes in

But even t hough the Brahmans

and Raj put s are cl earl y losing

gr ound in the status struggle t aki ng

place wi t hi n the t r adi t i onal caste

hi erarchy, they are not t aki ng

things l yi ng down by any means.

Thi s is where westernization enters

the pi ct ur e in a manner whi ch is

dynami cal l y i nt er-rel at ed wi t h the

events t aki ng place under the rub-

ri c of Sanskri t i zat i on. For I believe

that in pr opor t i on as the Brahmans

and Rajputs are losing ground in

the ol d caste hi erarchy, they are

reaching out in a di r ect i on we can

best call westernization (or perhaps

to-day the t er m ' moderni zat i on'

woul d be somewhat more appro-

pri at e) in order to obt ai n new

sources of status and power whi ch

effectively cont i nue to give them

the feel i ng that they are mai nt ai n-

i ng suitable social distance bet-

ween themselves and those whom

t hr y have t r adi t i onal l y defined as

l ow.

Al t hough not the sole factor res-

ponsi bl e, it seems l i kel y that this

process helps account for the. by

now wi del y observed fact that mo-

bi l i t y i n the di rect i on of urban and

modern empl oyment is more pre-

ponderant , i n relative terms, among

the hi gh than among the low cas-

tes. Edwi n Eames (1951) refers to

it wi t h some surprise in a village

( Ma d h o p u r ) whi ch he studied i n

Ut t ar Pradesh. He says :

It was assumed . . . that the great-

est amount of migration In urban

centres would he by members of these

castes which had lost their functions

in village life . . . and those who

were in the weakest economic position

in the village . , . However, the

largest group going outside the village

are Thakurs . . . who are the second

largest population group in Madhopur.

They are in the top economic position

of the village and the owners of the

, land, (pp 13-14)

Oscar Lewi s ( 1955) found the

same t hi ng in a Jat vi l l age near

Del hi and his comments on the

phenomenon are hi ghl y pert i nent to

this discussion :

. . . it is the higher caste Jats and

Brahmans at Rampar who have taken

the greatest initiative in getting out-

side work, who have the best-paid jobs

and the greatest number of them . . .

If such conditions are prevalent in

other Indian villages, it might mean

that the inequalities of the caste sys-

tem will be perpetuated, for the mem-

bers of the higher castes would be the

ones to benefit most in an industria-

lized India. (pp 301-302)

In all instances, the r eal i t y ap-

pears to be at wide variance wi t h

' classical

1

expectations concerni ng

mobi l i t y i n moderni zi ng societies,

where it is hold that the landless

and the i mpoveri shed are compell-

ed to move towards the city in

search of cash empl oyment whi l e

the landed and the well-off are eon-

tent to remai n pr opor t i onat el y

longer i n their r ur al habi t at .

False Dichotomies

Grant ed, this latter phenomenon

is also occur r i ng on a maj or scale

in I ndi a today and promises to be-

come even more intensified should

the rate of i ndust ri al i zat i on mat eri -

al l y increase dur i ng the next

twenty-five to fifty years. It is not

necessarv f or us to make any choi-

ces between false dichotomies in

this matter. What is at issue here

Is only the surpri si ngl y hi gh preva-

lence of elite mobi l i t y and the

correspondi ngl y sur pr i si ngl y low

prevalence of low caste mobi l i t y

by comparision with the former. It

is thiw whi ch is "unclassicar by con-

trast wi t h the West.

It suggests that the higher castes

arc for some reason if nest i ng a

large an ion ni of deliberate energy

i n westernization. pr opor t i onat el y

much more than the l ower castes

(at least in villages of the size and

si t uat i on of Sherupur and those

studied by Karnes and Lewi s ) .

whi l e the low castes are investing

a large amount of deliberate ener-

gy in Sanskri t i zat i on, pr opor -

tionately much more than the

hi gher castes, or so it woul d seem.

Thi s makes sense if we recognize

the pervasiveness of hi erarchi cal

t hi nki ng and feeling i n I ndi a and

consequently realize that the Brah-

mana and Rajputs have l i t t l e choice

left to them than to t ur n to wester-

ni zat i on as a means of mai nt ai ni ng

the social distance between t hem-

selves and the lower castes whi ch is

no longer possible wi t hi n lite ol d

order in the face of the Iatters'

current abi l i t y to Sanskritize them-

selves. If yon are already Sanskri-

l i zed. as are the Brahmans and the

Rajputs (al t hough I do not wish to

i mpl y that the two are f ul l y equi -

valent r i t nal l y or in any other way,

because they are not ) , then you

can' t go any hi gher up in the t r adi -

t i onal st rat i fi cat i on order. If you

947

can' t mai nt ai n t hi ngs as they are

t hr ough the appl i cat i on of pol i t i cal

and economic power then you can

onl y go down or accept the not i on of

equal i t y whi ch, i n effect, means

accepting the nul l i t y of the caste

system itself and hi erarchi cal rela-

tionships in general. Thi s is patent-

ly impossible for the hi gh castes,

wi t h their deeply embedded con-

ception of their inherent super i or i -

t y, and so they must move outside

the caste system wi nch spawned

them in order to preserve t hei r

pretensions to paramount status in

I ndi an .society.

New Bases of Superiority

Thi s is done in Sherupur and

elsewhere by convert i ng t hei r t radi -

t i onal intellectual skills, economic

advantages, and nepotic connections

into opport uni t i es for obt ai ni ng

modern education and what is com-

monl y called ' service' by whi ch'

is meant a j ob hi Government

(either pr ovi nci al or central) or i n

modern i ndust ry. To the extent

that they succeed in this endeavour,

Brahmans and Rajputs preserve a

measure of superi ori t y over t hei r

lower caste compat ri ot s in their

local communi t y (where not more

wi del y) whi ch mere Sanskri t i zat i on

is incapable of mat chi ng. For the

lower castes are wi t hout education

or any t r adi t i on of l earni ng, they

are wi t hout much economic power,

and they lack welI-elaborated ki n-

ship structures whi ch can be ave-

nues of connection and mobi l i t y

outside the local mi l i eu. Wi t hout

these assets, they cannot, hope to

at t ai n very much modern educat i on,

much less opport uni t i es f or "ser-

vice". And even in these rare i n-

stances where a low caste f ami l y

does acquire the means they fre-

quently t ur n t hei r resources to the

bui l di ng up of t hei r t r adi t i onal

status. In the village adj oi ni ng

Sherupur there is a Kor i who has

made considerable money out of

the bui l di ng construction business.

He has symbol i zed his new-found

opulence not by becoming a ' mo-

dern mai f but by bui l di ng a resi-

dence in the village which outsides

the hi gh castes in its t r adi t i onal

archi t ect ural style. Furt hermore,

he is compl et i ng const ruct i on of

the largest and most ornate

dhuratmluda (a rest house for rel i -

gious pi l grj ms) in the area, one

whi ch eclipses by far the numerous

comparable structures thereabout

associated wi t h hi gh caste benefac-

June 24, 1961

THE ECONOMIC WEEKLY

948

THE ECONOMIC WEEKLY June 24, 1961

tora. The Br ahman f ami l y whi ch

resides in the same haml et st i l l re-

fuses to interact wi t h t hi s Kor i ' s

f ami l y and the head of this Brah-

man household is an official in the

Sugar Cane Depart ment of the

Government of Ut t ar Pradesh!

Sanskritization not Distinctive

Enough

We may see this same pheno-

menon from the st andpoi nt of the

hi gh cables themselves. Those

fami l i es among the Brahmans and

Rajputs in Sherupur who have

bee unsuccessful i n convert i ng

their t r adi t i onal assets i nt o oppor-

tunities for sons to get a good

educat i on and "service" are depre-

cated even by their own caste fel -

l ows on this account. Where Sans-

kr i t i zat i on is t hei r only cl ai m to

status, they are insufficiently dis-

tinct f r om the lower castes, espe-

ci al l y from the mi ddl e groups l i ke

Ahi r and Kurmi who got modest

amounts of land out of Zami ndar i

abol i t i on. As a result. there is

much anxiely and f r el l i ng on this

score wi t hi n the ranks of the Brah-

mans and Rajputs. Many a father

f r om these castas has approached

me in the hope that I might he

able to intervene somewhere wi t h

a business executive or govern-

ment official on behalf of a son

whom he wants to get placed in

"service". Onl y one lower caslc

person has over so approached

me and this represents a very un-

usual case from many stand-

points.

8

St ri ct l y economic grounds are

insufficient to expl ai n what is

happeni ng and the fact that in

Sherupur all outside "while collar"

jobs las wel l as an over whel mi ng

preponderance of all outside jobs)

are hel d by ' he castes who rank

highest in the t r adi t i onal hierar-

chy. Tor these hi gh castes have

pract i cal l y al l the land i n the v i l -

lage and are in every mat eri al

respect i nfi ni t el y better off than

t hei r low caste bret hren. In fact.

I have encountered instances where

a hi gh caste f ami l y has urged its

son or sons out into the modern

j ob market even where havi ng

done so has left the vi l l age farm

short-handed and has entailed real

economic hardshi p f or the rest of

the f ami l y. They woul d rather have

a greater pr opor t i on of the agri -

cul t ur al work done by the landless

castes than is cust omary, and ac-

cept whatever other hardshi p that

may be i nvol ved, i f that wi l l as-

sure them the abi l i t y to count

among the accoutrements of t hei r

cont emporary status the fact that

one or more of t hei r sons are per-

f or mi ng prestigious wor k some-

where in the modern society beyond

the vi l l age. For then they do not

have to depend for t hei r hi gh posi-

t i on upon the ri cket y scale of Sans-

kr i t i zal i on alone, a cr i t er i on that

becomes meaningless to the Hrah-

inans and Raj put s in precisely the

degree to whi ch the castes beneath

them acqui re more and more Sans-

kr i t i zat i on i n t hei r own r i ght .

Mirage of Equality

Meanwhi l e, the low castes expend

a maj or share of their energy on

Sanskritrizatlion. In other words,

they are sal vi ng their wounded

collective ego born of past ages of

degradat i on and expl oi t at i on by

pur sui ng the mi rage of equal i t y

wi t h t he Brahmans and other hi gh

castes. By the time they reach

their destination, however, they wi l l

discovery that the Brahman has hi m-

self vacated the spot and moved on

to the hi gher hi l l of West erni zat i on

where he st i l l gazes contemptuous-

ly down upon them from an elevat-

ed porch. In fact, the motive-

power for the latter' s I nni ng done

so wi l l have been suppl i ed by the

process of Sanskri t i zat i on itself

whi ch, as its very success- caused

it to be coveted by and sought by

others, caused the hi gh castes to

abandon it in favour of new realms

of status. No doubt it wi l l be at

tins point that the lower castes also

commence abandoning t hei r craze

for Sanskri t i zat i on and then the

book wi l l have to close on this con-

cept, as the resultant new I ndi an

society comes to gri ps wi t h the pr o-

blem of hi rerarehy i n radi cal l y di f-

ferent and at this j unct ur e hardl y

forseeable terms.

It is not intended thai this, analy-

sis be const rued as an attempt to

provi de the expl anat i on of change

and mobi l i t y in I ndi an society to-

day. It is not even intended thai

this analysis be taken as appl i cabl e

in al l situations where issues of

change and mobi l i t y arise. Indi a is

too complex a society, and indus-

t ri al i zat i on and moderni zat i on loo

complex processes, for a single

general concept to be able to ac-

count for al l facets of the transfor-

mat i on that is bei ng brought about,

All that has been attempted here is

to show that, there may be an i m-

949

port ant dynami c i nt er pl ay between'

the processes of Sansknt i zat i on and

westernization

9

whi ch helps us ac-

count for such seeming anachr oni -

sms as the hi gh castes ( who

obvi ousl y have had the highest

stake in the ol d or der ) revealing

stronger urges t oward westerniza-

t i on and moderni zat i on, as symbo-

lized by occupat i onal mobi l i t y pat-

terns, than the l ower castes ( who

have had the least stake in the ol d

or der ) . Thi s is the opposite of

what we have been led to expect

on the basis of ' classical' accounts

of moderni zat i on deri ved f r om

Western data. In short, it is hoped

that it wi l l be seen that Srinivas' s

notion of westernization need not

be regarded merely as an ' i r ony'

l ul l as a necessary component of a

t horough comprehension of at least

one i mpor t ant di mensi on of the

total process of mobi l i t y and

change in Indi an society.

NOTES

1

By 'earliest' I have in mind the

'scientific past.' which for Anthropo-

logy commences little more than a

century ago.

2

- Hypergamy may be a comparatively

late manifestation in India if Srini-

vas- (1956) is correct . He says:

Over seventy years ago, the institu-

tion of bride-price seems to have

provaited among some sections of

Mysore Brahmans, But with wes-

ternisation, and the demand it

created tor educated boys who had

iiood jobs, dowry became popular.

The better educated a hoy, the

larger the dowry ids parents de-

manded for him. The ape at which

girls married shot up . . . Nowa-

days, urban ami middle-class Brah-

mans are rarely able to get their

girls married before they are eigh-

teen , . . ChiId widows are rare.,

and shaving the heads of widows is

practically a thing of the past.

(p 490).

Cf, William Crooke (1896) R V

Russell (1916) Herbert Risely

(1891). E Thurstone (1909)

1

Sherupur is a pseudonym hir a vill-

age in District Faizabad of Uttar

Pradesh, winch I studied first in

1954-55 under a Fulbright Student

Grant and which I further studied

from 1959 to 1961 under post-doctoral

fellowships from the National Science

Foundation and the National Insti-

tute of Mental Health respectively.

At that, time, a story was common

knowledge of how the head man of

a neighbouring village, a Rajput, had

come to suspect two Koris of

committing an act of theft in his

house. In traditional high caste

fashion, the old Rajput summoned

the two koris before him, adminis-

tered a beatiAV to them with a luthi

(a bamboo stick), and then locked

them in an out building and told

them he would keep them there un-

t i l they 'confessed.' Finally, in order

THE ECONOMIC WEEKLY

to gain release, the two Korin 'con-

fessed.' The old Rajput released

them, whereupon the) sped immedia-

tely to the local police station and

tiled a com plaint against him. At the

ensuing trial, the Rajput was found

guilty, fined Rs 500, and given three

months imprisonment. Since then,

there have been no further reports of

high castes administering summitry

punishment to low caste persons. The

Government has seen to it that those

days are ended for good. And in

this, we see one of the ways in which

the previous political power of the

upper castes has waned.

The leader of the Brahmans in Sheru

midable, the Brahmans and Rajputs

lost some of their lands to lower

castes due to the redistribution which

followed dissolution of the Zamindari

system of land control. This occurr-

ed in 1951 in Uttar Pradesh.

The leader of the Brahmans in Shem-

pur told me that in the years since

Independence, but prior to 1961

when the secret ballot was introduced

in the election of village headman,

he had come to verbal agreement

wiih the perennial Rujput headman

llial he won Id not oppose him as

long as he did nothing to harm the

interests ni die Brahmans in the:

community. In the 1961 elections,

however, this Brahman decided to

oppose the Rajput pradhan because,

he claimed, the latter had gone back

on his word. However, in this elec-

tion, all the high caste candidates

were defeated.

The son in question is an unusually

intelligent young Kori who is now

studying for his B A Final. Roth

parents of this boy aie also ni ex-

tiut.rdiuarily high intelligence (a fact

I have determined through the ad-

ministration of psychological tests

plus direct observation) and ate in

innumerable ways distinct trotu their

average caste-mates.

I am aware that all I have said here

depends upon one's assumption that

tire notion of Sanskritization is a va-

l i d one in the hist place. Many

social scientists both in bulla and

abroad have opposed the concept. So

have many who regard themselves- as

Classicists or linguists. Without go-

ing into the substance of these argu-

ments, here, I do nevertheless want

to state clearly that I do regard

Sanskritization as a useful, meaning-

ful, empirically defensible concept

oner, it is understood in the sense

that Srinivas has used it. In his

own words ( 1956 b) :

I have used the word Sanskriti-

zation to characterize a particular

process. I am not myself sure

whether by using it i have succeed-

ed in conveying what I want to.

1 should point out here, before

anybody else does it, that I my-

self do not like that ward. It is

extremely awkward. Rut I am not

able to find a substitute. The

only alternative word that suggests

itself to me is Brahmanization,

which is not any the less awkward.

This idea of Sanskritization has

been found useful by other work-

ers in the Indian hel d. . . By die

term Sanskritization, I mean the

process by which a low caste gives

up its own rites, customs, and be-

liefs, and takes tip, instead, the

customs, rites, and beliefs of a

higher caste. It is a much wider

term, than, and somewhat different

from, the term Brahmanization . . .

One of the funny things about

Sanskriti/ation is that, not infre-

quently, the agents of Sanskriti/a-

tion are not Bruhmaus. In fact,

they ate occasionally anti-Brah-

manical. They have Sanskritized

their way of life, and they spread

Sanskritization in the society as a

whole, and this goes with an anta-

gonism to the caste, whose ways

they have taken over, (pp 90-91)

In fact, it is possible to say that a

condition of Sanskriti/ation may be the

feeling of antagonism to 'the caste

whose ways' have been taken over! If

the issue were seen in this manner, the

bulk oi the objections to Sanskritization

as a concept should fade away. One

cannot help suspecting that some of the

objections arc trivialities and deliberate

misreadings which are motivated not so

much by the desire to clarify and am-

plify as by the desire to make rather

vain displays of "erudition."

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Crooke , William

1896"The Tribes and Castes of the

North nest Provinces and Oudh," Cal-

cutta: Superintendent of Documents.

1 vols.

Eames, Edwin

1951 "Some Aspects ill Urban Mig-

lalion from a Village in North Central

India. Faster n Anthroptdofiist. Vol

III. No I

Could, Harold

1950 "The Implications of Technolo-

gical Change for Folk and Scientihc

Medicine,'

'

Ameritan Anthropologist,

vol 59,' No 3.

1958 "The Hindu Jajmani .System:

A Case of Economic Particularism,"

Southwestern Journal of Anthropology,

Vol 14, No 4.

1959 "The Peasant Village : Centrifu-

gal or Centripetal. '' Eastern Anthropo-

logist. Vol XI II No 4.

Hutton, J II

1946 "Caste in I ndi a/ ' Bombay : Ox-

ford Press.

Lewis, Oscar

1956 "Aspects of Land Tenure and

Economics in a North Indian Village,"

Economic Development and Cultural

Change. Vol TV, No 3.-

Marriott. , MeKi m

1955 "Little Communities in an Indi-

genous Civilization," I n : "'Village India"

Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Risley, Herbert

189] "'The Tribes and Castes of Ben-

gar" Calcutta: Superintendent of Docu-

ments. L' 2 vols

Russel, R V

1916 '' The Tribes and Castes of the

Central Provinces of India." Condon :

Macmillan. 4 vols.

Srinivas, M N

1956 (a) "Sanskritization and Wester-

nization," Far Eastern Quarterly, Vol

XV, No 4

1956 (b) '"Sanskritization and Wester-

nization." in : "Society in India" (Edited

by Aiyappan and Ratnam , Madras ;

S S A Publication.

Thurstone, E

1909 "The Tribes and Castes of

Madras." 7 Vols.

950

June 24, 1961

You might also like

- Masterplan TemplateDocument72 pagesMasterplan TemplateMostafa FawzyNo ratings yet

- Society Against the State: Essays in Political AnthropologyFrom EverandSociety Against the State: Essays in Political AnthropologyRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (31)

- Order and Chivalry: Knighthood and Citizenship in Late Medieval CastileFrom EverandOrder and Chivalry: Knighthood and Citizenship in Late Medieval CastileNo ratings yet

- 669560Document22 pages669560KT GaleanoNo ratings yet

- PHD Progress Presentation TemplateDocument11 pagesPHD Progress Presentation TemplateAisha QamarNo ratings yet

- Sanskritization and Westernizationa - A Dynamic View - HAROLD GOULDDocument7 pagesSanskritization and Westernizationa - A Dynamic View - HAROLD GOULDAvinash PandeyNo ratings yet

- Chapter Four - Tradition and ModernityDocument37 pagesChapter Four - Tradition and ModernityWahhabbxss13No ratings yet

- Race, Amnesia, and The Education of International RelationsDocument14 pagesRace, Amnesia, and The Education of International RelationsVinay PaiNo ratings yet

- Sanskritisation: A P BarnabasDocument6 pagesSanskritisation: A P Barnabasjatin kumarNo ratings yet

- Dalit BodyDocument19 pagesDalit Bodypujasarmah806No ratings yet

- Lugones Heterosexualism and The Colonial Modern Gender SystemDocument25 pagesLugones Heterosexualism and The Colonial Modern Gender SystemPrismNo ratings yet

- The Proceedings of The American Ethnological SocietyDocument4 pagesThe Proceedings of The American Ethnological SocietysammycatNo ratings yet

- Lugones HeterosexualismColonial 2007Document25 pagesLugones HeterosexualismColonial 2007franciscatoledocNo ratings yet

- Caste and CastelessnessDocument8 pagesCaste and CastelessnessJayanth TadinadaNo ratings yet

- Rhetoric Against Age of Consent - Resisting Colonial Reason and Death of A Child-Wife - SarkarDocument11 pagesRhetoric Against Age of Consent - Resisting Colonial Reason and Death of A Child-Wife - SarkarAlex WolfersNo ratings yet

- Heterosexualism and The Colonial Modern Gender SystemDocument25 pagesHeterosexualism and The Colonial Modern Gender SystemQaima HossainNo ratings yet

- Caste and Castelessness in The Indian Republic by Satish DeshpandeDocument10 pagesCaste and Castelessness in The Indian Republic by Satish DeshpandeAbhishek ShawNo ratings yet

- Liminal It yDocument10 pagesLiminal It ylewis_cynthiaNo ratings yet

- Matriliny and Patriliny Between Cohabitation-Equilibrium and Modernity in The Cameroon GrassfieldsDocument40 pagesMatriliny and Patriliny Between Cohabitation-Equilibrium and Modernity in The Cameroon GrassfieldsNdong PeterNo ratings yet

- Syncretism and Its Synonyms ReflectionsDocument23 pagesSyncretism and Its Synonyms ReflectionsMuhammad Ibrahim KhokharNo ratings yet

- The Middle Men, An Introduction To The Transmasculine Identities+Document25 pagesThe Middle Men, An Introduction To The Transmasculine Identities+juaromerNo ratings yet

- Is Female To Male As Nature Is To Culture - OrtnerDocument28 pagesIs Female To Male As Nature Is To Culture - Ortnermoñeco azulNo ratings yet

- Sherry B. Ortner - Is Female To Male As Nature Is Tu Culture (Rosaldo & Lamphere, 1974)Document21 pagesSherry B. Ortner - Is Female To Male As Nature Is Tu Culture (Rosaldo & Lamphere, 1974)P. A. F. JiménezNo ratings yet

- Goettner-Abendroth, H. - Rethinking 'Matriarchy' in Modern Matriarchal Studies Using Two Examples. The Khasi and The MusuoDocument26 pagesGoettner-Abendroth, H. - Rethinking 'Matriarchy' in Modern Matriarchal Studies Using Two Examples. The Khasi and The MusuoP. A. F. JiménezNo ratings yet

- Sherry B. Ortner - Is Female To Male As Nature Is To CultureDocument28 pagesSherry B. Ortner - Is Female To Male As Nature Is To Culturelauraosigwe11No ratings yet

- Stewart-Syncretism and Its SynonymsDocument24 pagesStewart-Syncretism and Its SynonymshisjfNo ratings yet

- Freedom and CultureDocument128 pagesFreedom and CultureParang GariNo ratings yet

- Social ClassesDocument19 pagesSocial Classesraheel_uogNo ratings yet

- Pieces of Self - Anarchy, Gender and Other ThoughtsDocument22 pagesPieces of Self - Anarchy, Gender and Other ThoughtsSilviu PopNo ratings yet

- Notes On Passage: The New International of Sovereign Feelings - Fred MotenDocument25 pagesNotes On Passage: The New International of Sovereign Feelings - Fred MotenGrawpNo ratings yet

- The Religion of Socialism: Being Essays in Modern Socialist CriticismFrom EverandThe Religion of Socialism: Being Essays in Modern Socialist CriticismNo ratings yet

- Black Women Under State: Surveillance, Poverty & The Violence of Social AssistanceFrom EverandBlack Women Under State: Surveillance, Poverty & The Violence of Social AssistanceNo ratings yet

- 3 Society and Politics in India2Document12 pages3 Society and Politics in India2Aditya SanyalNo ratings yet

- Patil - From Patriarchy To IntersectionalityDocument22 pagesPatil - From Patriarchy To IntersectionalityNuzhat Ferdous IslamNo ratings yet

- A Manifesto in Four Themes: Rita Laura SegatoDocument14 pagesA Manifesto in Four Themes: Rita Laura SegatoTango1680No ratings yet

- How To Be Political. Art Activism, Queer PracticesDocument15 pagesHow To Be Political. Art Activism, Queer PracticesEliana GómezNo ratings yet

- Sherry B. Ortner - Is Female To Male As Nature Is To Culture - READING HIGHLIGHTEDDocument12 pagesSherry B. Ortner - Is Female To Male As Nature Is To Culture - READING HIGHLIGHTEDShraddhaNo ratings yet

- The Fragmentary City: Migration, Modernity, and Difference in the Urban Landscape of Doha, QatarFrom EverandThe Fragmentary City: Migration, Modernity, and Difference in the Urban Landscape of Doha, QatarNo ratings yet

- Yawnie - Comments On The Spiritual Baptist and Shango Papers Edited by Stephen D. GlazierDocument7 pagesYawnie - Comments On The Spiritual Baptist and Shango Papers Edited by Stephen D. GlazierArielNo ratings yet

- (15585816 - Theoria) Religious Origins of Modern RadicalismOCR PDFDocument30 pages(15585816 - Theoria) Religious Origins of Modern RadicalismOCR PDFFredericoDaninNo ratings yet

- College of Asia and The Pacific, The Australian National UniversityDocument27 pagesCollege of Asia and The Pacific, The Australian National UniversityAlice SheddNo ratings yet

- Culture and ColonialismDocument18 pagesCulture and ColonialismJudhajit SarkarNo ratings yet

- Susan PhilipDocument19 pagesSusan PhilipeἈλέξανδροςNo ratings yet

- Peter D. Hershock, Roger T. Ames Confucian Cultures of Authority Suny Series in Asian Studies Development 2006Document278 pagesPeter D. Hershock, Roger T. Ames Confucian Cultures of Authority Suny Series in Asian Studies Development 2006Guillermo Garcia VenturaNo ratings yet

- Contact Zone: Ethnohistorical Notes On The Relationship Between Kings and Tribes in Middle IndiaDocument26 pagesContact Zone: Ethnohistorical Notes On The Relationship Between Kings and Tribes in Middle Indiaarijeet.mandalNo ratings yet

- Dalit, Modernity and Metamorphosis of CastesDocument21 pagesDalit, Modernity and Metamorphosis of CastesAnand TeltumbdeNo ratings yet

- Queer - Migration, An Unruly Body of Scholarship - Eithne LuibheidDocument23 pagesQueer - Migration, An Unruly Body of Scholarship - Eithne LuibheidDiego Prieto OlivaresNo ratings yet

- Rhetoric Against Age of Consent. Resisting Colonial Reason and Death of A Child-WifeDocument11 pagesRhetoric Against Age of Consent. Resisting Colonial Reason and Death of A Child-WifehiringagentheroNo ratings yet

- 6 The Nation and Its QueersDocument22 pages6 The Nation and Its QueersJonah LegoNo ratings yet

- From Lineage To State Social Formations in The Mid First Mellennium B. C. in The Ganga Valley by Romila ThaparDocument3 pagesFrom Lineage To State Social Formations in The Mid First Mellennium B. C. in The Ganga Valley by Romila ThaparNandini1008100% (2)

- Muslim Loyalty and BelongingDocument18 pagesMuslim Loyalty and BelongingArdit KrajaNo ratings yet

- The Aith Waryaghar of The Moroccan Rif ADocument3 pagesThe Aith Waryaghar of The Moroccan Rif AFerdaousse BerrakNo ratings yet

- Avtar Brah - Questions of Difference and International FeminismDocument7 pagesAvtar Brah - Questions of Difference and International FeminismJoana PupoNo ratings yet

- How Public Was SaivismDocument46 pagesHow Public Was SaivismJoão AbuNo ratings yet

- Heelas Transpersonal Pakistan IJTS 32-2Document13 pagesHeelas Transpersonal Pakistan IJTS 32-2International Journal of Transpersonal StudiesNo ratings yet

- Turner, Liminality and CommunitasDocument20 pagesTurner, Liminality and CommunitasAaron Kaplan100% (1)

- Gender and Civil Society - An Interview With Suad JosephDocument5 pagesGender and Civil Society - An Interview With Suad JosephM. L. LandersNo ratings yet

- SSRN Id4426489Document11 pagesSSRN Id4426489aishaNo ratings yet

- Dynamics of Swaps SpreadsDocument32 pagesDynamics of Swaps SpreadsAkshat Kumar SinhaNo ratings yet

- VA+Tech+Wabag Inititating+coverageDocument32 pagesVA+Tech+Wabag Inititating+coverageAkshat Kumar Sinha0% (1)

- Customer Perception Towards TupperwareDocument6 pagesCustomer Perception Towards TupperwareAkshat Kumar Sinha100% (1)

- Niranjan - A Page From History - 70 Years Before The Brics Bank - 230714Document2 pagesNiranjan - A Page From History - 70 Years Before The Brics Bank - 230714Akshat Kumar SinhaNo ratings yet

- Judicial Meanderings in Patriarchal Thickets Litigating Sex Discrimination in IndiaDocument11 pagesJudicial Meanderings in Patriarchal Thickets Litigating Sex Discrimination in IndiaAkshat Kumar SinhaNo ratings yet

- Journal of Pediatric Surgery: Ibrahim UygunDocument4 pagesJournal of Pediatric Surgery: Ibrahim UygunNur Ainatun NadrahNo ratings yet

- Psychoanalysis: ArticleDocument21 pagesPsychoanalysis: ArticleAqsa ParveenNo ratings yet

- Project Report On Customer Satisfaction Towards LGDocument52 pagesProject Report On Customer Satisfaction Towards LGrajasekar100% (2)

- Rambabu Singh Thakur v. Sunil Arora & Ors. (2020 3 SCC 733)Document4 pagesRambabu Singh Thakur v. Sunil Arora & Ors. (2020 3 SCC 733)JahnaviSinghNo ratings yet

- Unit 10: Sitcom: Tonight, I'm CookingDocument3 pagesUnit 10: Sitcom: Tonight, I'm CookingDaissy FonsecaNo ratings yet

- Genrich Altshuller-Innovation Algorithm - TRIZ, Systematic Innovation and Technical Creativity-Technical Innovation Center, Inc. (1999)Document290 pagesGenrich Altshuller-Innovation Algorithm - TRIZ, Systematic Innovation and Technical Creativity-Technical Innovation Center, Inc. (1999)Dendra FebriawanNo ratings yet

- Las Castellana BananaDocument28 pagesLas Castellana BananajerichomuhiNo ratings yet

- 1.5 Introducing Petty Cash Books: Suggested ActivitiesDocument2 pages1.5 Introducing Petty Cash Books: Suggested ActivitiesDonatien Oulaii100% (2)

- Summary of VivekachudamaniDocument3 pagesSummary of VivekachudamaniBr SarthakNo ratings yet

- Royal Halloway University - Google SearchDocument1 pageRoyal Halloway University - Google SearchMasoomaIjazNo ratings yet

- RHPA46 FreeDocument5 pagesRHPA46 Freeheyimdee5No ratings yet

- Gas Supply Agreement 148393.1Document5 pagesGas Supply Agreement 148393.1waking_days100% (1)

- Division) Case No. 7303. G.R. No. 196596 Stemmed From CTA en Banc Case No. 622 FiledDocument16 pagesDivision) Case No. 7303. G.R. No. 196596 Stemmed From CTA en Banc Case No. 622 Filedsoojung jungNo ratings yet

- Research in Organizational Behavior: Sabine SonnentagDocument17 pagesResearch in Organizational Behavior: Sabine SonnentagBobby DNo ratings yet

- 86% Strike - 97% Stop Loss - 2 Months - EUR: Bullish Mini-Futures On The German Stock Index Future of June 2010Document1 page86% Strike - 97% Stop Loss - 2 Months - EUR: Bullish Mini-Futures On The German Stock Index Future of June 2010api-25889552No ratings yet

- Chemical Analysis of Caustic Soda and Caustic Potash (Sodium Hydroxide and Potassium Hydroxide)Document16 pagesChemical Analysis of Caustic Soda and Caustic Potash (Sodium Hydroxide and Potassium Hydroxide)wilfred gomezNo ratings yet

- Learning Agreement During The MobilityDocument3 pagesLearning Agreement During The MobilityVictoria GrosuNo ratings yet

- Architecture FormsDocument57 pagesArchitecture FormsAymen HaouesNo ratings yet

- 723PLUS Digital Control - WoodwardDocument40 pages723PLUS Digital Control - WoodwardMichael TanNo ratings yet

- Cola - PestelDocument35 pagesCola - PestelVeysel100% (1)

- Question Bank & Answers - PoetryDocument4 pagesQuestion Bank & Answers - PoetryPrabhjyot KaurNo ratings yet

- Federal Resume SampleDocument5 pagesFederal Resume Samplef5dq3ch5100% (2)

- FMGE Recall 1Document46 pagesFMGE Recall 1Ritik BhardwajNo ratings yet

- Personal Lifelong Learning PlanDocument7 pagesPersonal Lifelong Learning PlanRamilAdubal100% (2)

- Idoc - Pub Magic Sing Et25k Song List EnglishDocument30 pagesIdoc - Pub Magic Sing Et25k Song List EnglishFlorentino EsperaNo ratings yet

- Go Out in The World - F - Vocal ScoreDocument3 pagesGo Out in The World - F - Vocal ScoreParikNo ratings yet

- Electrical Energy by Dhanpat RaiDocument5 pagesElectrical Energy by Dhanpat RaiDrAurobinda BagNo ratings yet

- Appendix B For CPPDocument1 pageAppendix B For CPP16 Dighe YogeshwariNo ratings yet