Professional Documents

Culture Documents

KoikeLacorte2014 Culture

KoikeLacorte2014 Culture

Uploaded by

jorge_chilla76890 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

30 views17 pagesToward intercultural competence: from questions to perspectives and practices of the target culture by Dale Koike and Manel Lacorte. Taylor and Francis makes no representations or warranties as to the accuracy, completeness, or suitability for any purpose of the Content. This article may be used for research, teaching, and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, redistribution, reselling, loan, systematic supply, or distribution to anyone is expressly forbidden.

Original Description:

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentToward intercultural competence: from questions to perspectives and practices of the target culture by Dale Koike and Manel Lacorte. Taylor and Francis makes no representations or warranties as to the accuracy, completeness, or suitability for any purpose of the Content. This article may be used for research, teaching, and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, redistribution, reselling, loan, systematic supply, or distribution to anyone is expressly forbidden.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Download as pdf or txt

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

30 views17 pagesKoikeLacorte2014 Culture

KoikeLacorte2014 Culture

Uploaded by

jorge_chilla7689Toward intercultural competence: from questions to perspectives and practices of the target culture by Dale Koike and Manel Lacorte. Taylor and Francis makes no representations or warranties as to the accuracy, completeness, or suitability for any purpose of the Content. This article may be used for research, teaching, and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, redistribution, reselling, loan, systematic supply, or distribution to anyone is expressly forbidden.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Download as pdf or txt

You are on page 1of 17

This article was downloaded by: [Manel Lacorte]

On: 18 June 2014, At: 19:22

Publisher: Routledge

Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered

office: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK

Journal of Spanish Language Teaching

Publication details, including instructions for authors and

subscription information:

http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rslt20

Toward intercultural competence: from

questions to perspectives and practices

of the target culture

Dale Koike

a

& Manel Lacorte

b

a

Department of Spanish and Portuguese, University of Texas at

Austin, Austin, TX, USA

b

Department of Spanish and Portuguese, University of Maryland,

College Park, MD, USA

Published online: 16 Jun 2014.

To cite this article: Dale Koike & Manel Lacorte (2014) Toward intercultural competence: from

questions to perspectives and practices of the target culture, Journal of Spanish Language

Teaching, 1:1, 15-30, DOI: 10.1080/23247797.2014.898497

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/23247797.2014.898497

PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE

Taylor & Francis makes every effort to ensure the accuracy of all the information (the

Content) contained in the publications on our platform. However, Taylor & Francis,

our agents, and our licensors make no representations or warranties whatsoever as to

the accuracy, completeness, or suitability for any purpose of the Content. Any opinions

and views expressed in this publication are the opinions and views of the authors,

and are not the views of or endorsed by Taylor & Francis. The accuracy of the Content

should not be relied upon and should be independently verified with primary sources

of information. Taylor and Francis shall not be liable for any losses, actions, claims,

proceedings, demands, costs, expenses, damages, and other liabilities whatsoever or

howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with, in relation to or arising

out of the use of the Content.

This article may be used for research, teaching, and private study purposes. Any

substantial or systematic reproduction, redistribution, reselling, loan, sub-licensing,

systematic supply, or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. Terms &

Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/page/terms-

and-conditions

Toward intercultural competence: from questions to perspectives

and practices of the target culture

Dale Koike

a

* and Manel Lacorte

b

a

Department of Spanish and Portuguese, University of Texas at Austin, Austin, TX, USA;

b

Department of Spanish and Portuguese, University of Maryland, College Park, MD, USA

(Received 7 September 2013; accepted 29 November 2013)

Teaching second-language (L2) culture is problematic due to the possibility of

creating stereotypes and overgeneralizations about the target culture. Several

researchers have proposed raising an awareness of first-language culture (C1) at

the same time they raise that of the second language (C2), to promote a relative

view of the C2. The objective is for learners to recognize themselves and others as

socially constructed. We propose learning culture through activities based on

surveys completed by native speakers (NS) that can lead learners to a deeper

understanding of L2 cultural perspectives and practices. To illustrate this

approach, target culture data (e.g., folk medicines used or the kinds of housing

students live in) were obtained via a questionnaire completed by 154 native-

speaker university students in Spain, Peru, Mexico and Argentina. These data

were used to create activities asking L2 Spanish learners to (1) compare their own

answers to those of the NS, (2) seek an understanding of why the NS responded

that way, (3) react in a similar situation in the target culture and language, using

NS perspectives and practices, and (4) do research with heritage speakers in their

community. In this way, they can develop an emic or insiders perspective on

L2 cultural views, practices, and values.

Keywords: intercultural competence; culture; questionnaire; survey; perspectives;

practices; heritage speakers

La enseanza de cultura en una segunda lengua (L2) puede resultar problemtica

por la posibilidad de crear estereotipos y generalizaciones excesivas sobre la

cultura meta. Varios investigadores han propuesto potenciar la sensibilizacin

hacia la cultura de la primera lengua (C1) al mismo tiempo que se fomenta el

inters respecto a la de la segunda lengua (C2), a fin de promover una visin

relativa de la C2. El objetivo es que los aprendices se reconozcan a s mismos y

reconozcan a otras personas como individuos socialmente construidos. Noso-

tros proponemos aprender cultura mediante actividades basadas en encuestas con

hablantes nativos (NS) que puedan facilitar entre los aprendices una comprensin

ms profunda de las perspectivas y prcticas culturales de la L2. Para ilustrar este

enfoque, obtuvimos datos de la cultura meta (p.ej., medicinas tradicionales de uso

habitual o tipos de vivienda en que los estudiantes suelen residir) a travs de un

cuestionario con 154 hablantes nativos que cursan estudios universitarios en

Espaa, Per, Mxico y Argentina. Usamos estos datos para crear actividades en

que se peda a los aprendices de espaol como L2 que (1) comparasen sus propias

respuestas a las ofrecidas por los NS; (2) tratasen de comprender el porqu de las

respuestas de los NS; (3) reaccionasen a una situacin similar en la cultura y

*Corresponding author. Email: d.koike@austin.texas.edu

Journal of Spanish Language Teaching, 2014

Vol. 1, No. 1, 1530, http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/23247797.2014.898497

2014 Taylor & Francis

D

o

w

n

l

o

a

d

e

d

b

y

[

M

a

n

e

l

L

a

c

o

r

t

e

]

a

t

1

9

:

2

2

1

8

J

u

n

e

2

0

1

4

lengua metas, procurando emplear perspectivas y prcticas propias de los NS, y

(4) llevasen a cabo una investigacin con hablantes de herencia en su comunidad.

De este modo, los aprendices pueden desarrollar una perspectiva mica (desde

adentro) sobre puntos de vista, prcticas y valores culturales en la L2.

Palabras clave: competencia intercultural; cultura; cuestionarios; encuestas;

perspectivas; prcticas; hablantes de herencia

1. Introduction

Culture was often seen in the past as information about distinct areas such as the

arts, literature, philosophy or history; this perspective assumes the study of an

unchanging, monolithic set of cultural information. In recent years, however,

cultural knowledge is now considered an essential component of dynamic commun-

icative acts taking place within any given social context (Duranti 1997). Kramschs

(1998, 105) definition of culture as membership in a discourse community that

shares a common social space and history, and common imaginings represents such

a change in thinking of culture as an object of study, or a set of facts to be learned

about people and their products, lives and behaviors (Phillips 2001). Perspectives in

dealing with culture in the second-language (L2) classroom have shifted from

presenting facts to asking the students to interact with aspects of the target culture

while reflecting on their own first-language culture (C1). The goal is then to develop

an intercultural competence that, according to Bennett, Bennett and Allen (2003,

244), refers to the ability to relate effectively and appropriately in a variety of

cultural contexts. It requires culturally sensitive knowledge, a motivated mindset and

a skillset. In so doing, learners are able to understand more profoundly what

culture actually entails, become more engaged with cultural meanings, and

understand how the language they are learning is so embedded within culture that

the two should not be learned separately.

Raising students awareness of culture presents many challenges. It is difficult to

identify behaviors and values that represent, for example, the entire Hispanic culture.

It is easier to mention cultural artifacts and practices, such as the huipil shawl used

by indigenous people of Mexico and Central America, or the quinceaera celebration

of many Hispanic countries that takes place when a young girl turns 15 years old

(i.e., the big c culture; see Seelye 1984, 19). But culture itself is complex, as

Miquel and Sans (2004) suggest in their conception of three intimately related levels:

(1) culture with a capital C (literature, history, geography, gastronomy, arts, etc.);

(2) basic culture,

1

shared by most members of a society as a way to understand

behaviors and interact appropriately (e.g., the meaning of the color black as a

symbol of mourning in many Hispanic countries, or wishing people a happy saints

day as one would wish them a happy birthday); and (3) kulture with k, which

underlies the behavior and communication of specific groups who speak the same

language (e.g., Latin American immigrant communities in Spain, Latino youth in

the USA).

Galloway (1999) points out that we must also recognize the fact that every

language represents multiple societies and cultures. It is also difficult to identify

cultural behaviors and values (the little c culture) that underlie a society, much

less to generalize them to say that they are representative of most people of that

society. Take, for example, the US Hispanic-American population, embodied in

16 D. Koike and M. Lacorte

D

o

w

n

l

o

a

d

e

d

b

y

[

M

a

n

e

l

L

a

c

o

r

t

e

]

a

t

1

9

:

2

2

1

8

J

u

n

e

2

0

1

4

many generations of Spanish speakers in some cases (such as Mexican-Americans) or

in only one (such as the rather recent immigration from El Salvador), not to mention

that this Hispanic-American population comprises native Spanish speakers and their

descendants from many different countries and societies.

Complicating the matter, Knutson (2006, 597) also notes that culture within a

given society undergoes a dynamic process of continual change, as it is influenced by

other societies and experiences. How then does one choose what to teach to learners?

And how does one raise a cultural awareness without running the risk of stereotypes

and overgeneralizations about the target culture?

Finally, in closing this discussion of issues to consider in dealing with culture in

the foreign-language curriculum, we should mention two concepts that are important

and have been mentioned only briefly to this point: (1) meaning in language; and

(2) learners identities in the face of the C2. Regarding meaning in language,

following Liddicoat and Scarino (2013), meanings are created only within a context,

which is itself seen through the perspective of a culture. As they state, culture is a

dynamic process within which meanings are created, exchanged, and interpreted

(p. 8). This view of cultural meaning implies that learners cannot simply read or hear

about the C2 and understand it at a meaningful level, but instead must engage in it in

view of their present and past experiences and knowledge, most of which they draw

from their C1. In other words, following Pikes (1982) concept of a participant

emic or subjective insiders view of a culture and a society, the goal should be to

foster such a viewpoint of the target culture in the L2 learner to the extent possible.

Such a view would be built on the NS insiders perspectives of their C1 and also on

the learners perspectives of their respective C1, with the goal of the learners coming

to understand and accept the NS insiders viewpoints of their C1.

The second issue of identity is also important in the teaching of culture. Learners

come to the task of learning a second language and culture with a sense of a given

identity that they own (Norton 2013). In order to understand and see the C2 relative

to their C1, this identity should undergo at least some change as they look at their

own C1 and then at the C2 to question, reflect on, and attempt to understand and

interpret both of them. This kind of critical understanding positions the learners in

relation to these identities (Liddicoat and Scarino 2013, 9).

In the next section we briefly review some proposals by other researchers for

what teachers can do to help learners achieve an intercultural competence, as well as

teachers cultural beliefs and a basic model for culture teaching. Then we present our

own conception of steps by which learners can come to see culture in relative terms.

Finally, we end with some conclusions and implications for culture teaching and

learning.

2. Proposals for teaching culture; teacher attitudes and needs; cultural teaching model

2.1. Proposals for teaching culture

Several researchers in the past have proposed raising an awareness of C1 at the same

time that the C2 is discussed, in order to promote a relative view of the C2 (Byram

1997). The objective of this proposal is to lead the learners to recognize themselves

and others as socially constructed (Roberts et al. 2001, 30), as well as culturally

constructed (Phillips 2001). This notion represents the view that what others do and

how they co-construct us, and vice versa, greatly influence each of us in our societies.

Journal of Spanish Language Teaching 17

D

o

w

n

l

o

a

d

e

d

b

y

[

M

a

n

e

l

L

a

c

o

r

t

e

]

a

t

1

9

:

2

2

1

8

J

u

n

e

2

0

1

4

This view is reflected in the American Council on the Teaching of Foreign Language

(ACTFL) National Standards (1996, 2006), which state that one cultural goal in

language teaching and learning should be to help learners develop an understanding

of the distinct and unique nature of cultures, both their own and the target culture,

and attempt to discover aspects of the C2 that are similar to and different from their

own C1. Specifically, as OBrien and Levy (2008) clarify:

Standards 2.1 and 2.2 speak to three important aspects of the target culture: (a)

behavioral practices (i.e., patterns of social interactions such as forms of discourse and

the use of space); (b) philosophical perspectives (i.e., meanings, attitudes, values,

ideas); and (c) both tangible and intangible products (i.e., books, tools, foods, laws,

music, games). (Standards 2006, 47, as cited in OBrien and Levy 2008, 664)

Knutson (2006, 592) argues against attempts to present culture as information,

not only because they present the difficult choice of which culture(s) to teach and

what content to include, but also because they implicitly represent cultures under

study as other, or marked, diverging from the home culture norm. Instead, she

argues for a type of cultural instruction that can develop a cross-cultural

awareness and an understanding of cultural-bound values and behavior. Following

Galloways (1999, 153) concept of developing the cross-cultural mind, she also

supports the notion of developing an awareness of ones own (C1) culture at the

same time that one learns of the C2 culture to be able to make comparisons of values

and other cultural aspects appropriately. Such is the concept of learners themselves

as cultural subjects (cf. Kramsch 1993), and raising an awareness of themselves

within their own culture along with other cultures.

This idea fits well with Kramschs (1993, 239) notion of the language learners

third space, referring to that space between the home and the target culture, in

which the instructor attempts to help the learners develop an understanding of C2

behaviors and values, while the learners take whatever information they find most

interesting and relevant and make many of their own interpretations. Kramsch

argues that this unwillingness to try to identify with, much less become like, the

other indicates that there is a need for the learners to understand themselves as

cultural subjects, which they must study before they can truly move on to study

aspects of the C2 such as practices and institutions.

Knutson (2006) also confronts the issue of learners reluctance to let go of their

own identity when interacting with the C2 and not wanting to change their face in

front of their peers. Likewise, this reluctance would impede their embracing aspects

of the C2, including that of a C2 identity. For this reason, she supports the concept

of openly discussing mixed feelings that can emerge during lessons on the C2, even

if antagonistic opinions may be expressed (p. 594).

2.2. Teachers cultural beliefs

Of course, the above goals for the teaching of culture in the L2 classroom also apply to

teachers, who should have a deep understanding of their own culturally conditioned

and individually formed beliefs, attitudes, and values (Quinn Allen 2000, 51). In this

regard, the field of teacher cognition analyzes what teachers know, believe, and

think (Borg 2003, 81) and the relationship of these mental constructs to what teachers

18 D. Koike and M. Lacorte

D

o

w

n

l

o

a

d

e

d

b

y

[

M

a

n

e

l

L

a

c

o

r

t

e

]

a

t

1

9

:

2

2

1

8

J

u

n

e

2

0

1

4

do in the L2 classroom(Borg 2006). Research on L2 teacher cognition has been prolific

in recent years, especially related to the teaching of grammar (e.g., Baleghizadeh and

Rezai 2010; Borg 1999; Burgess and Etherington 2002; Wong and Barrea-Marlys

2012). Along these lines, several studies have focused on L2 teachers beliefs and

practices when dealing with culture in their classrooms. In the context of English as a

foreign language in Spain, Sercu, Mndez Garca and Castro Prieto (2005) examine the

extent to which recent views of L2 learning as a self-directed process of constructing

meaning are reflected in teachers practices regarding cultural content. Their analysis

of data obtained through a web-based questionnaire with both open and closed

questions indicates that teachers tend to resort to an information model as the most

efficient way of teaching culture rather than a constructivist model. Constructivism

posits that the way we perceive reality in our world is through the categories that we use

to describe it; the categories are also the way we experience events. A constructivist

model would then require a more interactive approach to culture learning.

Also based on a questionnaire administered to English teachers in China, Han and

Song (2011) note teachers strong doubts about the possibility of students acquiring

intercultural skills at the university level, and of teaching L2/C2 in an integrated way

due to the teachers unfamiliarity with specific aspects of the target cultures as well as

the inadequacy of (inter)cultural elements in the teaching materials (p. 190). In a

study set in a Turkish university using questionnaires and interviews aimed at teachers

of English as an FL, Kuru-Gnen and Saglam (2012) point out that while teachers are

generally aware of the importance of integrating culture in the FL classroom, the

way in which they deal with the target culture is highly affected by curricular

considerations and limitations (p. 44) such as the syllabus, the units in the course

book, and other pedagogical materials. Finally, Byrd et al. (2011), in surveying world

language teachers, found a need for a healthier balance between the traditional

emphasis on cultural products and practices in the FL classroom, and much-needed

attention to understanding cultural perspectives, reflection on underlying cultural

attitudes and beliefs, and the knowledge of how to teach them.

2.3. Toward a model for teaching culture

There are many proposals for teaching culture, including authentic materials,

proverbs, role play, culture capsules, ethnographic projects, literature, film, etc.

(for some recent proposals see Byrd and Wall 2009; Dai 2011; Furstenberg 2010;

Kaiser 2011; Levine 2012). We must also mention the vast inventory of cultural

information on Hispanic artifacts, behaviors, conventions, etc., presented in the

Marco comn europeo de referencia para las lenguas: aprendizaje, enseanza,

evaluacin (MCER) by the Instituto Cervantes.

2

Considering those notions reviewed

above, we take as a point of departure some of the ideas presented by Bennett,

Bennett and Allen (2003) in their Developmental Model on Intercultural Sensitivity

(DMIS). Briefly, the model describes stages through which learners pass as they

acquire intercultural competence, which the authors explain by constructivist

principles (Watzlawick 1984), defined earlier. The authors claim that this framework

provides a way to understand how we develop an ability to construe and, likewise, to

experience cultural differences. Therefore, the more sophisticated and complex the

individuals world view, the more that individual will become interculturally

sensitive and competent (Bennett, Bennett and Allen 2003, 247).

Journal of Spanish Language Teaching 19

D

o

w

n

l

o

a

d

e

d

b

y

[

M

a

n

e

l

L

a

c

o

r

t

e

]

a

t

1

9

:

2

2

1

8

J

u

n

e

2

0

1

4

The DMIS is divided into two broad stages through which learners pass:

Ethnocentric and Ethnorelative. In the Ethnocentric stage, the learners perceive

the target culture comparing it to their own C1 but, as time goes on, their

perceptions of cultural differences improve regarding their polarization of differ-

ences. In the Ethnorelative stage, the learners discover their own cultural context and

become increasingly accepting of their own behavior in view of the C2. They become

more adept at shifting their cultural frame of reference to see the C2 gradually

through the eyes of the people who embody the C2. In the final stages, learners are

able to shift their perceptions of self-identity and their perspective of the C2 as a

normal process as they view events, such that they are moving around in cultures

(Bennett, Bennett and Allen, p. 251). Although we do not follow their proposals for

curriculum design, we do incorporate many of these ideas in our method of using

cultural surveys as a basis for teaching culture, which we present in the next section.

An important culture teaching tool is seen in the Cultura Project (Furstenberg

2001, 2003), a telecollaborative course that aims at allowing learners and teachers,

for example in the USA and a target country, to learn about each other via an online

forum (Cultura Community site: http://cultura.mit.edu). The participants complete

surveys and post their opinions on various topics in their native languages for all to

read and comment upon, which in turn become objects of study for language and

cultural viewpoints. Blyths (2012) study based on the Cultura site discusses how

both French and American students were asked to post their thoughts about

individualism/individualism. He finds that for the French, the concept elicits negative

images (e.g., social isolation), while the American students viewed it as a positive

construct (e.g., the American Dream). The Cultura project has generated many

studies (e.g., Bauer et al. 2006; Blyth 2012; Furstenberg 2010; Furstenberg et al.

2001; Levet and Waryn 2006). We note, however, that one drawback of the project

appears to be that it sets up binary distinctions in which students are led to generalize

according to nationality (e.g., the French believe X while the Americans think Y),

which would seem to create divisions instead of intersubjectivity (Trmion 2013). We

believe our proposal, described below, could avoid this problem.

3. The use of cultural surveys

Based on the concepts and ideas about cultural learning and teaching that have been

reviewed in the previous sections, we propose teaching and learning culture through

use of a survey and activities that lead to L2 cultural perspectives and practices. This

proposal is carried out in various stages, which are: (1) finding out what the target

culture(s) think and do; (2) presenting scenarios; and (3) contrasting cultures. These

stages are discussed below.

3.1. Step 1: Finding out what the target culture(s) think and do

3.1.1. Procedures: Participants

We propose that the first step on which to raise cultural awareness is to find out what

people in the target culture(s) believe and do in their everyday practices. To this end,

we gathered data via an online questionnaire from 154 undergraduate university

students who were majoring in English as a Second Language in four Hispanic

countries: Mexico, Peru, Argentina, and Spain.

3

This age group was targeted, as well

20 D. Koike and M. Lacorte

D

o

w

n

l

o

a

d

e

d

b

y

[

M

a

n

e

l

L

a

c

o

r

t

e

]

a

t

1

9

:

2

2

1

8

J

u

n

e

2

0

1

4

as this specialty, in order to reflect the age group of our target audience of Spanish

learners (1822 years old, undergraduate level of study), as well as their interest in

learning a foreign language.

4

Professors of English as a Second Language in those

countries that we knew were contacted via email to ask if they would pass on our

email to their students, requesting their participation in the online survey. The survey

was posted on a website for a certain number of days, and any students who wanted

to answer the questions were invited to do so. If they desired, they received their

choice of one of four bestseller books on the New York Times Bestseller List at

that time.

Because the responses were completely spontaneous, we believe we obtained at

least a fairly representative sample of views of Hispanic cultural beliefs and practices

of this age group.

3.1.2. Procedures: Questionnaire

The culture questionnaire used in this study included 19 questions that ranged from

certain cultural products (e.g., the kinds of medicines they use when they are ill) to

practices (e.g., type of housing that they live in while they study at the university).

The topics of the questions were selected according to the scope and sequence of an

elementary Spanish language textbook project that the authors were working on at

the time. The survey was hosted on an online platform (SurveyMonkey) and made

accessible to participants through a website address within a given time frame. Some

of the questions were open-ended, while others were multiple-choice but with one of

the choices as Other, to which the respondents could fill in a blank.

3.1.3. Procedures: Tallying the results

After the survey was closed to further participation, the results were categorized,

tallied, and reported in terms of percentages. Individual answers were also saved in

order to illustrate examples of certain patterns and tendencies. We present two

examples here to illustrate how the survey is used and how activities are developed

from it. For example, one of the questions was:

Question 1: Qu valoras ms a la hora de comer?

After seeing the question, native Spanish speakers saw the following options:

(a) la calidad de la comida

(b) el precio de la comida

(c) la gente con quien comes

(d) el lugar donde comes

(e) otro.

The L2 Spanish learners saw results in percentages as shown in Table 1.

5

As Table 1 illustrates, most of the informants in Peru and Argentina commented

on the quality of the food as being the most important factor. In Mexico, the

responses are mostly divided between the quality of the food and the people with

whom they eat, while in Spain more students identified the people with whom they

Journal of Spanish Language Teaching 21

D

o

w

n

l

o

a

d

e

d

b

y

[

M

a

n

e

l

L

a

c

o

r

t

e

]

a

t

1

9

:

2

2

1

8

J

u

n

e

2

0

1

4

eat as most important, followed closely by the quality of the food. It is interesting

that no Spanish students commented on the place of the meal as of any import.

Apparently the price of the food and the place where the meal is eaten are not of

much importance to most participants in all the countries, although the fact that

there are some who ranked these options as most important should be noted, since

outliers are found in any society.

Before the L2 Spanish students see these results, they are also asked to answer the

same questions (e.g., What is most important to you at meal time?), presumably

using software or some other format that displays the percentages of the class

at once. Those results can be posted next to those in Table 1, and students can begin

to discuss among themselves questions based on the table, such as the following:

(1) Despus de ver los resultados de todos los grupos, discutan lo siguiente en

grupos pequeos:

. Por qu hay diferencias entre los grupos?

(a) No hay diferencias entre las culturas hispanas.

(b) La gente come comida buena y barata.

(c) Hay diferencias culturales con respecto a valores y prcticas sociales.

(d) Los estudiantes jvenes demandan una alta calidad de comida.

. Reflejan las diferencias diferentes valores o comportamientos entre los pases?

(a) S.

(b) No.

. Si es as, puedes decir cules son los valores o comportamientos relacionados

a la comida?

(a) La comida es buena si es de calidad y si hay buena compaa.

(b) La comida es un evento social para ciertas culturas hispanas.

(c) Si no como bien, no es comida.

(d) Todas las respuestas ac.

Depending on the level of Spanish proficiency of the group (true beginner,

previous study, accelerated), the questions can be in English or Spanish, with or

without the multiple-choice options provided. The discussion after seeing these

questions, if it occurs, can also be in Spanish or English. The goal is that the students

come to recognize at least some of the following:

(a) There are cultural differences concerning meals even within the Hispanic

culture(s).

Table 1. Qu valoras ms a la hora de comer?

Per Espaa Mxico Argentina

Calidad de la comida 60.9 43.5 41.5 51.1

Precio 8.7 4.4 3.8 4.4

Gente con quien comes 21.7 52.2 39.6 31.1

Lugar donde comes 4.4 0 11.3 8.9

Otro 4.4 0 3.8 4.4

Sin respuesta 0 0 0 0

22 D. Koike and M. Lacorte

D

o

w

n

l

o

a

d

e

d

b

y

[

M

a

n

e

l

L

a

c

o

r

t

e

]

a

t

1

9

:

2

2

1

8

J

u

n

e

2

0

1

4

(b) The differences reflect different social expectations and values connected with

meals.

(c) Values among the Hispanic groups in general for this population of students

seem to reflect the expectation that meals should be of good quality but also

should be eaten in good company.

(d) The price and place where meals are eaten are definitely secondary to the

other values for most native speakers in all the countries.

Students should also consider how closely their own C1 cultural values reflect

those seen in the questionnaire results and, where there are differences, what the

origin might be. Since US student populations are increasingly of mixed ethnic

groups, practices and values discussed might reflect that mixture.

3.2. Step 2: Presenting scenarios

The next step is to try to contextualize what the students might have gained from the

questionnaire, relevant to the topic of meals.

Situacin 1:

Te han invitado por email a cenar en Buenos Aires donde ests (donde

estudias) para el cumpleaos de tu amiga argentina. No sabes los detalles todava;

solo la fecha y la hora. Imagina cmo va a ser el escenario (cuntas personas van a

ir; si son amigos muy ntimos o colegas no tan ntimos; si van a cenar en un lugar

elegante o de comida regular; etc.).

[or students may choose from among options such as:

(a) Probablemente van muchos amigos a un restaurante del barrio, con comida

regular que no cuesta mucho.

(b) Probablemente van a un restaurante con comida elegante, y pocos amigos

van a ir.

(c) Probablemente van a la casa de otra amiga que es una cocinera excelente,

pero no va mucha gente porque no hay espacio.

(d) Probablemente van a la casa de una amiga y todos van a llevar cualquier cosa

para comer.]

After the discussion in Step 1, the L2 learners might generalize what they have

learned about the Hispanic cultures, perhaps to guess that for the Argentine friend,

the most likely scenario might (a), (b) or (c). If the friend values food very much, she

probably would like (b) or (c), but if she likes to be with many friends and the food is

not that important, then option (a) might be selected. Of course, these again are

generalizations and one must consider the personalities and circumstances of the

individuals as well.

3.3. Step 3: Contrasting cultures

After learners have had an opportunity to apply their cultural deductions to a

situation in a Hispanic culture, they can then try to imagine how the same situation

would play out in the C1.

Situacin 2: En tu propia cultura:

Journal of Spanish Language Teaching 23

D

o

w

n

l

o

a

d

e

d

b

y

[

M

a

n

e

l

L

a

c

o

r

t

e

]

a

t

1

9

:

2

2

1

8

J

u

n

e

2

0

1

4

Imaginemos que tu amiga argentina viene a visitarte en los Estados Unidos. T

quieres invitar a otros estudiantes norteamericanos que tambin estudiaron en

Argentina y que la conocen para verla. Qu escenario escoges?

(a) Tienes una fiesta en casa y compras comida cara porque es muy importante

para tu amiga, pero invitas a solo tres o cuatro amigos.

(b) Compras comida barata pero invitas a muchos amigos porque ellos son lo

ms importante para el evento.

(c) Les pides a muchos amigos que traigan cualquier comida a tu casa (pot

luck).

6

(d) Les pides a pocos amigos que traigan bebidas alcohlicas (byob)

7

y/o la

mejor comida que sepan preparar.

Since it is quite common in the USA for friends to bring drinks (e.g., a bottle of

wine, a six-pack of beer) to an informal party, sometimes the party organizer buys

relatively little in the way of drinks (perhaps soft drinks or a few bottles of wine) and

counts on the friends to bring them. So it may be that the US Spanish learners who

had not had much experience abroad would select option (d), and/or perhaps (c) if

they know the other friends well. These options help defray the costs of the party.

But if one takes the perspective of the Argentine students as reflected in the survey, it

is possible that either (a) or (b) would be the first choices.

This comparison of cultural norms is important, as discussed earlier, because

they are relative to ones own perspective and because the goal is to help the learners

understand (and eventually accept) cultural differences instead of rejecting them as

foreign.

3.4. Second cultural example

Another example is as follows.

Question 2: Quin paga la cuenta?

Related to the same topic of meals, another question that reflects practices is

that of who pays the bill after eating with a friend. The question was presented as

follows: Qu opinas sobre la idea de dividir la cuenta con un/a compaero/a cuando

hay que pagar la cuenta despus de comer en un restaurante?

3.4.1. Step 1: Learners answer the same question

Learners begin by answering the following questions:

(1) Qu opinas sobre la idea de dividir la cuenta con un/a compaero/a cuando

hay que pagar la cuenta despus de comer en un restaurante?

(2) Te ofendes cuando tu compaero/a no quiere dividir la cuenta (que cada

quien pague su propia comida)? Te ofendes a veces cuando l/ella insiste en

dividir la cuenta?

(3) Discuten esto antes de comer?

Results from the class are tallied and shown to the students. Since the first

question was an open-ended question, there were no options presented from which to

24 D. Koike and M. Lacorte

D

o

w

n

l

o

a

d

e

d

b

y

[

M

a

n

e

l

L

a

c

o

r

t

e

]

a

t

1

9

:

2

2

1

8

J

u

n

e

2

0

1

4

choose. Students may want to explain their points of view, if there is more than one

popular response.

3.4.2. Step 2: Hispanic students answer the same question

Results for this question from the students of Peru and Spain were as shown in

Table 2.

Learners see their answers in comparison to those displayed in Table 2 and are

asked to comment (in English or Spanish) if they agree or disagree with any of the

opinions expressed by the Hispanic students. They see that most Peruvian students

are in agreement that both people should pay the bill after the meal, whereas the

Spanish students are more divided between both parties paying their own bill or

dividing it only if both ate more or less the same quantity of food. In other words, it

seems that nearly a third of the Spanish students are interested in ensuring equity

among the individuals.

It is interesting to see in the individual comments for Spanish students that one

person differentiated behaviors about paying for food versus for drinks: for drinks,

everyone should pay for a round of drinks (which means there would be a lot of

drinking if the group is large). Among the Peruvian students, it is also of note that

several students felt that if one invited another to eat, then the inviter is expected to

pay; an expectation that was not even mentioned among the Spanish students.

One would hope that the Spanish L2 learners could spot these subtle differences

in behaviors regarding paying the bill after a meal, a matter that could cause

cross-cultural difficulties if expectations in the C1 and C2 are different.

3.4.3. Step 3: Scenarios

Again, the next step is to contextualize the information learned about the target

culture from the questionnaire, which here would be relevant to the topic of settling

the bill after a meal in a Hispanic country with a Hispanic friend.

Table 2. Qu opinas sobre la idea de dividir la cuenta con un/a compaero/a?

Per (%) Espaa (%)

S, es apropiado y correcto 67.7 42.9

Solo si los dos comieron ms o menos lo equivalente 28.6

Tomamos turnos 10.7

Las invitaciones son una excepcin (no se divide) 12.9 1 persona

S, aunque uno pierde 1 persona

Est bien pero es mejor si cada quien paga lo suyo 1 persona

Si son bebidas, cada uno paga una ronda 1 persona

Si es un grupo grande, cada quien paga un porcentaje 1 persona

Hay que discutirlo primero 1 persona -

Depende de la relacin 1 persona -

Hay que pagar lo suyo para evitar malentendidos 1 persona -

Me gusta pagar lo mo 1 persona -

Si puedo ayudar a mi amigo/a 1 persona -

Yo pago por ser caballero 1 persona -

Journal of Spanish Language Teaching 25

D

o

w

n

l

o

a

d

e

d

b

y

[

M

a

n

e

l

L

a

c

o

r

t

e

]

a

t

1

9

:

2

2

1

8

J

u

n

e

2

0

1

4

Situacin 3:

Ests en Barcelona y almuerzas por primera vez con una chica que se sienta cerca

de ti en una de tus clases. Ella pide un bocadillo y una cerveza, diciendo que no tiene

mucha hambre, por 5 euros. T tienes mucha hambre y pides el men del da: una

sopa, un platillo de espaguetis, un bife pequeo con patatas, y meln, con un vaso de

vino, por 9 euros.

(1) Al terminar de comer, cmo se paga la cuenta?

(a) Los dos dividen la cuenta en dos.

(b) Cada persona paga lo suyo.

(c) Esta vez t pagas, y ella la prxima.

(d) Si eres hombre, tienes que pagar. Si eres mujer, cada persona paga

lo suyo.

(2) Es mejor discutir esto antes de pedir la comida, durante la comida, o

despus de comer?

(3) Y si la amiga es peruana y estn en Lima?

This scenario puts the learners in the Hispanic culture of Spain (and then Peru)

and asks them to consider the situation of how to pay and how to address the matter

in a perspective that might be more appropriate there. It is likely that, after seeing

the data from the Spanish students, most learners would choose (b) as the preferred

option because the price of the meals should be almost the same if the bill is divided

in half. However, in Peru, the response would likely be (a), where dividing the check

is more expected.

3.4.4. Step 4: Contrasting cultures

Situacin 4:

Ests en Cincinnati, Ohio, almorzando con tu amiga espaola por primera vez.

(1) Al terminar de comer, cmo se paga la cuenta?

(a) Los dos pagan la mitad de la cuenta.

(b) Cada persona paga lo suyo.

(c) Esta vez t pagas, y ella la prxima.

(d) Si eres hombre, debes pagar. Si eres mujer, cada persona paga

lo suyo.

(2) Es mejor discutir esto antes de pedir la comida, durante la comida, o

despus de comer?

In the USA, it is common among students for individuals to pay for their own

meal (b), or they take turns paying if they frequently eat together (c), or they often

split the check if at a sit-down restaurant (not fast food) (a). Social norms

regarding gender roles and who should pay for the bill have changed considerably

over the years such that it is no longer assumed that men always pay the tab (d).

Since discussing the matter of payment with someone one does not know well can be

awkward, it is usually mentioned casually at the middle or end of the meal. If it is the

first time the two parties eat together, there is usually some brief conversation about

how the bill will be paid, and it is frequently split evenly as both will often attempt to

26 D. Koike and M. Lacorte

D

o

w

n

l

o

a

d

e

d

b

y

[

M

a

n

e

l

L

a

c

o

r

t

e

]

a

t

1

9

:

2

2

1

8

J

u

n

e

2

0

1

4

order the same meal or something similar to each others price range. In Spain, the

students in our survey indicated that they preferred to split the bill, especially if the

amounts are somewhat different for the two meals.

As a final step in all the cultural topics, if it is possible, learners are asked to find

a Hispanic person they know (in classes, the neighborhood, church or other

organization, etc.) and ask the same question. In this way, they can perhaps learn

more about the cultural norms of the Hispanics in their own community. If the

Hispanics are of the second, third, or other generation in the country, it is likely that

learners will discover that these individuals often shift among cultural norms of the

Hispanic and the dominant society, or that they use norms that represent an

amalgamation of norms.

The goal, of course, is for learners to discuss their own cultural expectations

regarding cultural norms, and to compare them to those of the different Hispanic

groups, so that they might see their own behaviors and values in light of those of

Hispanic cultures. We want them to come to expect more or less certain behaviors

when they are in one or the other culture (with the understanding that not everyone

in a society behaves the same way), and react more or less as native speakers would

expect or at least accept as not being too foreign.

4. Conclusions and implications

This description of how we use cultural surveys serves to illustrate our overall

approach to the teaching of culture; i.e., from questions answered by native speakers

and students to the development of learners understanding of target perspectives

and practices. Since we recognize that not all instructors may have the time or

resources to conduct the same kind of cultural survey with students in other

countries, another option would be to gather data from recently arrived Hispanics or

heritage speakers in the local community. What is important is to hear the voices

of the targeted group of Hispanics themselves, not what a person observes about

the culture. Their information serves as a springboard into discussion and reflection

about both C1 and C2.

Culture permeates every aspect of human life, and it is continuously evolving

(Bennett, Bennett, and Allen 2003). As such, its dynamicity most definitely affects

efforts of intercultural communication and interpretations that people make in such

situations. As Liddicoat (2009, 131) states, Intercultural communication is

communication that is continually mindful of the multiple possibilities of interpreta-

tion resulting from the possible presence of multiple cultural constructs, value

systems and conceptual associations which inform the creation and interpretation of

messages. For that reason, should cultural surveys be used in language teaching,

they should be updated regularly, to reflect cultural changes in Hispanic societies.

Nevertheless, the use of questionnaires also has its limitations, as Drnyei and

Taguchi (2010, 6) point out, including the risk of eliciting simplified and superficial

answers, unreliable and unmotivated respondents, a bias toward providing what is

believed to be the socially desirable answers, and a tendency to overgeneralize.

Despite these risks, we believe the data reflected in our questionnaires show probable

tendencies in the different Hispanic cultures, which can provide valuable information

to students. They serve as a point of departure into the cultural norms under study

and a window to critical thinking about intercultural differences.

Journal of Spanish Language Teaching 27

D

o

w

n

l

o

a

d

e

d

b

y

[

M

a

n

e

l

L

a

c

o

r

t

e

]

a

t

1

9

:

2

2

1

8

J

u

n

e

2

0

1

4

In addition, using these questionnaires helps the Spanish language educator tap

into current norms of these students who could arguably be said to represent

communities of practice in their societies (Lave and Wenger 1991). The Hispanic

student groups who participated in our cultural questionnaires often shared the same

career goals (usually English teachers or translators) and went through the same

classes together in their programs for several years. If it can be claimed that they are

indeed communities of practice, then, as Ochs (1996, 416) points out, Members of

societies are agents of culture rather than merely bearers of a culture encoded in

grammatical form the relationship between person and society is dynamic and

mediated through language (cf. Corder and Meyerhoff 2007). It is the task of the L2

educator to help learners find and interact with that relationship between people and

their culture, striving to develop an emic or insiders perspective (Pike 1982) on

L2 cultural views, practices and values.

Notes

1. The authors call this cultura a secas, which we have loosely translated here as basic

culture.

2. See, for example: http://cvc.cervantes.es/Ensenanza/biblioteca_ele/plan_curricular/niveles/

11_saberes_y_comportamientos_introduccion.htm.

3. Although it would be useful for readers to see the complete questionnaire, we are unable to

include it here at this moment because it is part of a larger textbook project. We can only

show a sample of what is included in the questionnaire.

4. As was the case in the United States in the population of students who study foreign

languages as a specialization, the great majority of Spanish native speaker respondents

were females.

5. Students saw the results displayed in pie charts where possible.

6. Pot Luck signifies the expectation that each person invited to the event will bring

something to share with the others (dessert, main dish, salad, etc.).

7. BYOB (bring your own beverage/booze) signifies that the guests are supposed to

bring beverages (usually alcohol) to share with others.

References

Baleghizadeh, S., and S. Rezaei. 2010. Pre-service Teacher Cognition on Corrective

Feedback: A Case Study. Journal of Technology and Education 4 (4): 32127.

Bauer, B., L. deBenedette, G. Furstenberg, S. Levet, and S. Waryn. 2006. Internet-mediated

Intercultural Foreign Language Education: The Cultura Project. In Internet-mediated

Intercultural Foreign Language Education, eds. J. A. Belz and S. L. Thorne, 3162. Boston:

Heinle & Heinle.

Bennett, J., M. Bennett, and W. Allen. 2003. Developing Intercultural Competence in the

Language Classroom. In Culture as the Core: Perspectives on Culture in Second Language

Learning, eds. D. Lange and R. Michael Paige, 23770. Greenwich, CT: Information Age.

Blyth, C. 2012. Cross-cultural Stances in Online Discussion: Pragmatic Variation in French

and American Ways of Expressing Opinions. In Pragmatic Variation in First and Second

Language Contexts, eds. C. Flix-Brasdefer and D. Koike, 4979. Amsterdam: John

Benjamins.

Borg, S. 1999. Teachers Theories in Grammar Teaching. ELT Journal 53 (3): 15767.

doi:10.1093/elt/53.3.157.

Borg, S. 2003. Teacher Cognition in Language Teaching: A Review of Research on

What Language Teachers Think, Know, Believe and Do. Language Teaching 36: 81109.

doi:10.1017/S0261444803001903.

Borg, S. 2006. Teacher Cognition and Language Education: Research and Practice. London:

Continuum.

28 D. Koike and M. Lacorte

D

o

w

n

l

o

a

d

e

d

b

y

[

M

a

n

e

l

L

a

c

o

r

t

e

]

a

t

1

9

:

2

2

1

8

J

u

n

e

2

0

1

4

Burgess, J., and S. Etherington. 2002. Focus on Grammatical Form: Explicit or Implicit?

System 30: 43358. doi:10.1016/S0346-251X(02)00048-9.

Byram, M. 1997. Teaching and Assessing Intercultural Communicative Competence. Clevedon:

Multilingual Matters.

Byrd, D., A. Cummings, J. Watzke, and M. F. Montes Valencia. 2011. An Examination of

Culture Knowledge: A Study of L2 Teachers and Teacher Educators Beliefs and

Practices. Foreign Language Annals 44 (1): 439. doi:10.1111/j.1944-9720.2011.01117.x.

Byrd, D., and A. Wall. 2009. Long-term Portfolio Projects to Teach and Assess Culture

Learning in the Secondary Spanish Classroom: Shifting the Area of Expertise. Hispania 92

(4): 77477.

Corder, S., and M. Meyerhoff. 2007. Communities of Practice in the Analysis of Intercultural

Communication. In Handbook of Intercultural Communication, vol. 7, eds. H. Kotthoff

and H. Spencer-Oatey, 44161. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

Dai, L. 2011. Practical Techniques for Culture-based Language Teaching in the EFL

Classroom. Journal of Language Teaching and Research 2 (5): 103136. doi:10.4304/

jltr.2.5.1031-1036.

Drnyei, Z., and T. Taguchi. 2010. Questionnaires in Second Language Research: Construc-

tion, Administration, and Processing. London: Routledge.

Duranti, A. 1997. Linguistic Anthropology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Furstenberg, G. 2003. Reading Between the Cultural Lines. In Reading Between the Lines:

Perspectives on Foreign Language Literacy, ed. P. Patrikis, 7498. New Haven, CT: Yale

University Press.

Furstenberg, G. 2010. Making Culture the Core of the Class: Can it be Done? Modern

Language Journal 94 (2): 32932. doi:10.1111/j.1540-4781.2010.01027.x.

Furstenberg, G., S. Levet, K. English, and K. Maillet. 2001. Giving a Virtual Voice to the

Silent Language of Culture: The Cultura Project. Language Learning & Technology 5 (1):

55102.

Galloway, V. 1999. Bridges and Boundaries: Growing the Cross-cultural Mind. In Language

Learners of Tomorrow: Process and Promise, eds. M. A. Kassen and M. Abbott, 15187.

Lincolnwood, IL: National Textbook.

Han, X., and L. Song. 2011. Teacher Cognition of Intercultural Communicative Competence

in the Chinese ELT Context. Intercultural Communication Studies 20 (1): 17592.

Kaiser, M. 2011. New Approaches to Exploiting Film in the Foreign Language Classroom.

L2 Journal 3 (2): 23249.

Knutson, E. 2006. Cross-cultural Awareness for Second/Foreign Language Learners. The

Canadian Modern Language Review 62 (4): 591610. doi:10.3138/cmlr.62.4.591.

Kramsch, C. 1993. Context and Culture in Language Teaching. Oxford: Oxford University

Press.

Kramsch, C. 1998. Language and Culture. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Kuru-Gnen, S., and S. Saglam. 2012. Teaching Culture in the FL Classroom: Teachers

Perspectives. International Journal of Global Education 1 (3): 2646.

Lave, J., and E. Wenger. 1991. Situated Learning: Legitimate Peripheral Participation.

Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Levet, S., and S. Waryn. 2006. Using the Web to Develop Students In-depth Understanding

of Foreign Cultural Attitudes and Values. In Changing Language Education through

CALL, eds. R. P. Donaldson and M. Haggstrom, 95118. London: Routledge.

Levine, G. 2012. The Study of Literary Texts at the Nexus of Multiple Histories in the

Intermediate College-level German Classroom. L2 Journal 4 (1): 17188.

Liddicoat, A. 2009. Communication as Culturally Contexted Practice: A View from

Intercultural Communication. Australian Journal of Linguistics 29 (1): 11533. doi:10.10

80/07268600802516400.

Liddicoat, A., and A. Scarino. 2013. Intercultural Language Teaching and Learning. Malden,

MA: Wiley-Blackwell.

Miquel, L., and N. Sans. 2004. El componente cultural: un ingrediente ms en las clases de

lengua. RedELE 0. http://www.mecd.gob.es/redele/revistaRedEle/2004/primera.html.

National Standards in Foreign Language Education Project. 1996, 2006. Standards for Foreign

Language Learning in the 21st Century. Yonkers, NY: Author.

Journal of Spanish Language Teaching 29

D

o

w

n

l

o

a

d

e

d

b

y

[

M

a

n

e

l

L

a

c

o

r

t

e

]

a

t

1

9

:

2

2

1

8

J

u

n

e

2

0

1

4

Norton, B. 2013. Identity and Second Language Acquisition. In The Encyclopedia of

Applied Linguistics, ed. C. Chapelle, 18. New York: Wiley-Blackwell.

OBrien, M., and R. Levy. 2008. Exploration through Virtual Reality: Encounters with the

Target Culture. Canadian Modern Language Review 64 (4): 66391. doi:10.3138/

cmlr.64.4.663.

Ochs, E. 1996. Linguistic Resources for Socializing Humanity. In Rethinking Linguistic

Relativity, eds. J. Gumperz and S. Levinson, 40738. Cambridge: Cambridge University

Press.

Phillips, E. 2001. IC? I See! Developing Learners Intercultural Competence. LOTE CED

Communiqu 3. http://www.sedl.org/loteced/communique/n03.html.

Pike, K. 1982. Linguistic Concepts: An Introduction to Tagmemics. Lincoln, NE: University of

Nebraska Press.

Quinn Allen, L. 2000. Culture and the Ethnographic Interview in Foreign Language Teacher

Development. Foreign Language Annals 33 (1): 5157. doi:10.1111/j.1944-9720.2000.tb

00889.x.

Roberts, C, M. Byram, A. Barro, S. Jordan, and B. Street. 2001. Language Learners as

Ethnographers. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters.

Seelye, H. N. 1984. Teaching Culture: Strategies for Intercultural Communication. Lincoln-

wood, IL: National Textbook.

Sercu, L., M. C. Mndez Garca, and P. Castro Prieto. 2005. Culture Learning from a

Constructivist Perspective. An Investigation of Spanish Foreign Language Teachers

Views. Language and Education 19 (6): 48395. doi:10.1080/09500780508668699.

Trmion, V. 2013. Constructing a Relationship to Otherness in Web-based Exchanges

for Language and Culture Learning. In Linguistics for Intercultural Education, eds.

F. Dervin and A. Liddicoat, 16174. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Watzlawick, P., ed. 1984. Invented Reality: How do we Know What we Believe we Know?

(Contributions to Constructivism). New York: W. W. Norton.

Wong, C., and M. Barrea-Marlys. 2012. The Role of Grammar in Communicative Language

Teaching: An Exploration of L2 Teachers Perceptions and Classroom Practices.

Electronic Journal of Foreign Language Teaching 9 (1): 6175.

30 D. Koike and M. Lacorte

D

o

w

n

l

o

a

d

e

d

b

y

[

M

a

n

e

l

L

a

c

o

r

t

e

]

a

t

1

9

:

2

2

1

8

J

u

n

e

2

0

1

4

You might also like

- Lucrare Grad IDocument86 pagesLucrare Grad ISorina Nitu100% (1)

- Sample-Class Program and Teachers ProgramDocument2 pagesSample-Class Program and Teachers Programmaestro2483% (6)

- Cambridge English Prepare Level 3 Annual Plan 1st Semester Teacher SupportDocument3 pagesCambridge English Prepare Level 3 Annual Plan 1st Semester Teacher SupportNatalia Zachynska100% (1)

- Alicia Beckford - Low Prestige and Seeds of Change Attitudes Towards Jamaican CreoleDocument37 pagesAlicia Beckford - Low Prestige and Seeds of Change Attitudes Towards Jamaican CreoleRuben Maci100% (2)

- Session Plan-Hairdressing CoreDocument3 pagesSession Plan-Hairdressing CoreJoy CelestialNo ratings yet

- Cross Curricular - Maybe Something BeautifulDocument5 pagesCross Curricular - Maybe Something BeautifulasmaaNo ratings yet

- Akbar The GreatDocument4 pagesAkbar The Greataniteja100% (1)

- Interculturality and Socio-Linguistic Identity in The Learning of English and Spanish in MexicoDocument6 pagesInterculturality and Socio-Linguistic Identity in The Learning of English and Spanish in MexicoAmbrosini GonzanunNo ratings yet

- Intercultural Reflection in EFL Coursebooks: C A ELTDocument8 pagesIntercultural Reflection in EFL Coursebooks: C A ELTVioletaNo ratings yet

- Culture: What To Teach and How To Teach It in An EFL ClassDocument6 pagesCulture: What To Teach and How To Teach It in An EFL ClassstrikeailieNo ratings yet

- Jackie F. K. Lee and Xinghong LiDocument20 pagesJackie F. K. Lee and Xinghong Liarifinnur21No ratings yet

- Why Multicultural Literacy PDFDocument27 pagesWhy Multicultural Literacy PDFRea Rose SaliseNo ratings yet

- An Introduction To Sociolinguistics 9Document9 pagesAn Introduction To Sociolinguistics 9felipe.ornella162400No ratings yet

- Language Identity Amongst SHLDocument22 pagesLanguage Identity Amongst SHLapi-242422638No ratings yet

- 01 AlexeDocument10 pages01 AlexeLy FNo ratings yet

- Language, Culture, and Identity in Online Fanfiction: Rebecca W. BlackDocument15 pagesLanguage, Culture, and Identity in Online Fanfiction: Rebecca W. BlackHuay Mónica GuillénNo ratings yet

- Keskass Aitaissa PDFDocument27 pagesKeskass Aitaissa PDFMarouaNo ratings yet

- Decolonizing American Spanish: Eurocentrism and Foreignness in the Imperial EcosystemFrom EverandDecolonizing American Spanish: Eurocentrism and Foreignness in the Imperial EcosystemNo ratings yet

- Applied Folklore HandoutDocument114 pagesApplied Folklore HandoutnaboendaluNo ratings yet

- Peck D, 1998Document9 pagesPeck D, 1998Rafael LeeNo ratings yet

- Second Language AcquisitionDocument9 pagesSecond Language AcquisitionFarleyvardNo ratings yet

- Teaching and Learning CultureDocument6 pagesTeaching and Learning CultureAngelds100% (1)

- The Aim and The Task of The Discipline. 2Document7 pagesThe Aim and The Task of The Discipline. 2Yuliia ShulzhenkoNo ratings yet

- англ гос часть 1Document41 pagesангл гос часть 1Юлия ЛевицкаяNo ratings yet

- HOLLIDAY Adrian - Small Cultures. Oxford University Press. 1999Document28 pagesHOLLIDAY Adrian - Small Cultures. Oxford University Press. 1999AidaNo ratings yet

- BlaanDocument14 pagesBlaanRiu CarbonillaNo ratings yet

- Teaching A Foreign Language and Foreign Culture To Young LearnersDocument13 pagesTeaching A Foreign Language and Foreign Culture To Young Learnerssonu thigleNo ratings yet

- The Beauty of A Rainbow Takes Shape in Its Separate ColorsDocument7 pagesThe Beauty of A Rainbow Takes Shape in Its Separate Colorswsgf khiiNo ratings yet

- Hon 499 B DraftDocument67 pagesHon 499 B Draftapi-457779759No ratings yet

- Culture in Second or Foreign LanguageDocument5 pagesCulture in Second or Foreign LanguageJamme SamNo ratings yet

- Cosscultural AspectsDocument16 pagesCosscultural AspectsFreddy Benjamin Sepulveda TapiaNo ratings yet

- British Vs AmericanDocument40 pagesBritish Vs AmericanBELKYSNo ratings yet

- TranslanguagingDocument14 pagesTranslanguagingCarlos SanzNo ratings yet

- Intercultural Competence in Elt Syllabus and Materials DesignDocument12 pagesIntercultural Competence in Elt Syllabus and Materials DesignLareina AssoumNo ratings yet

- Elt 2Fccq089Document9 pagesElt 2Fccq089Abolfazl MNo ratings yet

- Le Page E. A 1976 - Socioling Survey CayoDocument33 pagesLe Page E. A 1976 - Socioling Survey Cayobodoque76No ratings yet

- EL104 Material 7Document5 pagesEL104 Material 7graceurgel00No ratings yet

- Teaching Culture in EFL: Implications, Challenges and StrategiesDocument5 pagesTeaching Culture in EFL: Implications, Challenges and StrategiesPhúc ĐoànNo ratings yet

- Teaching Culture Through Advertising: Ana Viale MoutinhoDocument8 pagesTeaching Culture Through Advertising: Ana Viale MoutinhoBetea RebecaNo ratings yet

- IIIInternationalColloquiumProceedings Split MergeDocument13 pagesIIIInternationalColloquiumProceedings Split MergeQinyuan ZhangNo ratings yet

- ED522274Document25 pagesED522274Trang NguyenNo ratings yet

- Ed 426588Document20 pagesEd 426588Pabi SowNo ratings yet

- Campbell Et Al. (2000)Document14 pagesCampbell Et Al. (2000)Gene JezabelNo ratings yet

- Quantitative ResearchDocument36 pagesQuantitative ResearchgitinyNo ratings yet

- Leeman Martinez2007-3Document31 pagesLeeman Martinez2007-3Juan MezaNo ratings yet

- Power Point SlidesDocument24 pagesPower Point SlidesAleynaNo ratings yet

- Module 4 Session 1Document15 pagesModule 4 Session 1Евгения ТкачNo ratings yet

- Douglas Fir Group 2016Document30 pagesDouglas Fir Group 2016Pâmela CamargoNo ratings yet

- DouglasFir 2016Document29 pagesDouglasFir 2016Aurora TsaiNo ratings yet

- Ethnographic Approaches in SociolinguisticsDocument8 pagesEthnographic Approaches in SociolinguisticsPonsiana UmanNo ratings yet

- Colegio Del Centro: "Slang"Document8 pagesColegio Del Centro: "Slang"Anel Medina OsorioNo ratings yet

- Unit 4 Communicative Competence Analysis of ItsDocument50 pagesUnit 4 Communicative Competence Analysis of ItsAlicia GonzalezNo ratings yet

- Unit Plan - Assignment 3Document11 pagesUnit Plan - Assignment 3api-395466744No ratings yet

- Fichamento - Corbett - An Intercultural Approach To English Language TeachingDocument8 pagesFichamento - Corbett - An Intercultural Approach To English Language TeachingtatianypertelNo ratings yet

- Cultural Competence Refers To An Ability To Interact Effectively With People of Different CulturesDocument5 pagesCultural Competence Refers To An Ability To Interact Effectively With People of Different CulturesKim EliotNo ratings yet

- 741 2250 1 PBDocument9 pages741 2250 1 PBkhusna asNo ratings yet

- FleetDocument30 pagesFleetTatjana BozinovskaNo ratings yet

- Peters OnDocument2 pagesPeters OnMaia Siu NhơnNo ratings yet

- Exploring The Role of Cultural Schemata in Bridging The Gap Between PeopleDocument7 pagesExploring The Role of Cultural Schemata in Bridging The Gap Between PeopleJulia MarczukNo ratings yet

- Language and CultureDocument12 pagesLanguage and CultureDuong Huyen ThamNo ratings yet

- The Cultural Nature of Content and KnowledgeDocument11 pagesThe Cultural Nature of Content and Knowledgeapi-667898540No ratings yet

- MaterialDocument58 pagesMaterialhernanariza89No ratings yet

- Didactic S of Languages and CulturesDocument10 pagesDidactic S of Languages and Culturesjairo alberto galindo cuestaNo ratings yet

- Exploring Cultural Content of Three PromDocument13 pagesExploring Cultural Content of Three Promトラ グエンNo ratings yet

- Intercultural Communication and Public PolicyFrom EverandIntercultural Communication and Public PolicyNgozi IheanachoNo ratings yet

- Introduction To LiteratureDocument13 pagesIntroduction To LiteratureClaire Evann Villena EboraNo ratings yet

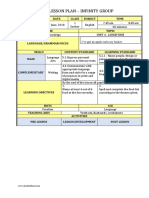

- Infinity Group Lesson Plan 2018 With Dropdown MenusDocument2 pagesInfinity Group Lesson Plan 2018 With Dropdown MenusNoraini Sha'riNo ratings yet

- Ethel Schuster, Haim Levkowitz, Osvaldo N. Oliveira JR (Eds.) - Writing Scientific Papers in English Successfully - Your Complete Roadmap-Hyprtek (2014)Document154 pagesEthel Schuster, Haim Levkowitz, Osvaldo N. Oliveira JR (Eds.) - Writing Scientific Papers in English Successfully - Your Complete Roadmap-Hyprtek (2014)Fellype Diorgennes Cordeiro Gomes100% (1)

- Ubc 2008 Fall Yoshida KaoriDocument320 pagesUbc 2008 Fall Yoshida KaoriStarryz1221cNo ratings yet

- Thesis Statement For Religion in Public SchoolsDocument4 pagesThesis Statement For Religion in Public Schoolsrobynnelsonportland100% (2)

- The Meiji Ishin ( Meiji Restoration') and KaikokuDocument8 pagesThe Meiji Ishin ( Meiji Restoration') and KaikokuBlackstone71No ratings yet

- Integration Paper Lakbay Aral Walled City - Fort Santiago Intramuros, ManilaDocument4 pagesIntegration Paper Lakbay Aral Walled City - Fort Santiago Intramuros, ManilaVien AlmeroNo ratings yet

- Lesson 3 HandoutDocument6 pagesLesson 3 HandoutJaylynJoveNo ratings yet

- Marcus Folch - The City and The Stage - Performance, Genre, and Gender in Plato's Laws-Oxford University Press (2015)Document401 pagesMarcus Folch - The City and The Stage - Performance, Genre, and Gender in Plato's Laws-Oxford University Press (2015)Fernanda PioNo ratings yet

- MAKALAH Cooperative PrincipleDocument7 pagesMAKALAH Cooperative Principlenurul fajar rahayuNo ratings yet

- AristotleDocument624 pagesAristotlelev2468100% (2)

- Interview QuestionsDocument10 pagesInterview QuestionsMunyambo Laurent0% (1)

- 2007 Wright MM UsDocument73 pages2007 Wright MM UshcearwickerNo ratings yet

- Cbjeenss 01Document6 pagesCbjeenss 01rishabh boseNo ratings yet

- Marriage Plan B-Wps OfficeDocument2 pagesMarriage Plan B-Wps Officeokasamuel068No ratings yet

- Grade 1 English Worksheet 5Document2 pagesGrade 1 English Worksheet 5Jayson AceNo ratings yet

- q2 Week 4 RealDocument14 pagesq2 Week 4 RealJasmin Goot RayosNo ratings yet

- Russia Under Stalin ReviewDocument11 pagesRussia Under Stalin Reviewcreyes25100% (1)

- Analysing Three Decades of Emerging Market ResearchDocument12 pagesAnalysing Three Decades of Emerging Market ResearchMariano Javier DenegriNo ratings yet

- Bridget Jones Movie WorksheetDocument4 pagesBridget Jones Movie WorksheetLilian OliveiraNo ratings yet

- Foner - Chapter 11 SummaryDocument1 pageFoner - Chapter 11 SummaryDan ZhuNo ratings yet

- Giant TurnipDocument17 pagesGiant TurnipCkay Okay KongNo ratings yet

- Disciplines and Ideas in The Social ScienceDocument1 pageDisciplines and Ideas in The Social ScienceEricka Rivera SantosNo ratings yet

- Reply To Žižek Paola Cavalieri and Peter SingerDocument15 pagesReply To Žižek Paola Cavalieri and Peter SingerSamuel León MartínezNo ratings yet

- Primer - UP Open UniversityDocument14 pagesPrimer - UP Open UniversityLin Coloma Viernes WagayenNo ratings yet