Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Travails of The Nation: Some Notes On Indian Documentaries

Travails of The Nation: Some Notes On Indian Documentaries

Uploaded by

satyabashaCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- Representation of Social Issues in CinemaDocument11 pagesRepresentation of Social Issues in CinemaShashwat Bhushan GuptaNo ratings yet

- KHALISTAN-The Only Solution by Partap SinghDocument140 pagesKHALISTAN-The Only Solution by Partap SinghJamshaidzubairee100% (2)

- Gandhi Review 21178-2Document15 pagesGandhi Review 21178-2beeban kaurNo ratings yet

- Representation of Partition in Hindi Films of The Nehruvian EraDocument8 pagesRepresentation of Partition in Hindi Films of The Nehruvian EraTJPRC PublicationsNo ratings yet

- NEHRUVIAN' CINEMA AND POLITICS - JstorDocument11 pagesNEHRUVIAN' CINEMA AND POLITICS - JstoryuktaamukhiNo ratings yet

- Moving Images of GandhiDocument10 pagesMoving Images of GandhisatyabashaNo ratings yet

- Gandhi - Teachers' Notes Study GuideDocument19 pagesGandhi - Teachers' Notes Study GuideRitu SinghNo ratings yet

- Decolonization - EssayDocument5 pagesDecolonization - EssayPetruţa GroşanNo ratings yet

- Cinematic Representations of Partition of IndiaDocument10 pagesCinematic Representations of Partition of IndiaGlobal Research and Development ServicesNo ratings yet

- China IndiaEPWDocument5 pagesChina IndiaEPWVinay LalNo ratings yet

- 3 4 7 Ecl 047Document4 pages3 4 7 Ecl 047ravishkumar76685No ratings yet

- Revenge, Masculinity and Glorification of Violence in The GodfatherDocument8 pagesRevenge, Masculinity and Glorification of Violence in The GodfathersairaNo ratings yet

- Censorship Madhava - 1Document11 pagesCensorship Madhava - 1Ashish CherukuriNo ratings yet

- The Communists and 1942Document9 pagesThe Communists and 1942Sukiran DavuluriNo ratings yet

- Film As A Tool For War Propaganda Synopsis From World WarDocument6 pagesFilm As A Tool For War Propaganda Synopsis From World WarAnh NguyenNo ratings yet

- Iram Parveen BilalDocument12 pagesIram Parveen BilalSiddharth SaratheNo ratings yet

- Orientalism, Terrorism, Bombay CinemaDocument13 pagesOrientalism, Terrorism, Bombay CinemaPrem VijayanNo ratings yet

- History ProjectDocument8 pagesHistory Projectavik sadhuNo ratings yet

- Alluda MajakaDocument55 pagesAlluda Majakadurga workspotNo ratings yet

- History of Documentary and Short FilmsDocument23 pagesHistory of Documentary and Short FilmsahaanakochharofficialNo ratings yet

- The Majoritarian Politics of Art FilmsDocument10 pagesThe Majoritarian Politics of Art FilmsA.C. SreehariNo ratings yet

- Black Friday 1Document11 pagesBlack Friday 1Jeenit MehtaNo ratings yet

- Films and Religion - An Analysis of Aamir Khan - S PK PDFDocument31 pagesFilms and Religion - An Analysis of Aamir Khan - S PK PDFYuraine EspantoNo ratings yet

- Aamir Khans PK PDFDocument31 pagesAamir Khans PK PDFSushil KumarNo ratings yet

- Romancing India On Screen: Falling in LineDocument1 pageRomancing India On Screen: Falling in LineVishal MaheshwariNo ratings yet

- Inventing A Genocide The Political AbuseDocument7 pagesInventing A Genocide The Political AbuseBobby ShaNo ratings yet

- Gandhi A Movie Review by Khalid MonerDocument2 pagesGandhi A Movie Review by Khalid MonerAadhitya NarayananNo ratings yet

- Azadi - Arundhati RoyDocument88 pagesAzadi - Arundhati RoyUmar Kanth100% (1)

- Gandhi 1982Document19 pagesGandhi 1982Dev AroraNo ratings yet

- PDFDocument335 pagesPDFghalib86No ratings yet

- The Best StoryDocument6 pagesThe Best StoryEslyium AvalonNo ratings yet

- 2013-10 - 0148 PinjarDocument5 pages2013-10 - 0148 PinjarBilal ShahidNo ratings yet

- Gandhi: Assigment-4Document5 pagesGandhi: Assigment-4Sankar AmiNo ratings yet

- A Second Evil Empire The James Bond Series Red CDocument19 pagesA Second Evil Empire The James Bond Series Red CmandlisasikiranNo ratings yet

- Mallhi Illusion of SecularismDocument15 pagesMallhi Illusion of SecularismNikithaNo ratings yet

- History Project Film Review: Gandhi (Richard Attenborough)Document8 pagesHistory Project Film Review: Gandhi (Richard Attenborough)avik sadhuNo ratings yet

- Dilip Simeon - Gandhi - S Legacy (2010)Document21 pagesDilip Simeon - Gandhi - S Legacy (2010)shubham.rathoreNo ratings yet

- IJCRT2107745Document3 pagesIJCRT2107745kishoreNo ratings yet

- Revisiting 1947 Through Popular CinemaDocument9 pagesRevisiting 1947 Through Popular CinemaManahil Saeed100% (1)

- Draft of Movie Fire.Document12 pagesDraft of Movie Fire.RajnishNo ratings yet

- Hanlon 1: Prisoners of Conscience (Patwardhan 1978), Which Document The Bihar Movement, TheDocument24 pagesHanlon 1: Prisoners of Conscience (Patwardhan 1978), Which Document The Bihar Movement, TheChris Johan V. WarthonNo ratings yet

- Legacy of Mahatma GandhiDocument24 pagesLegacy of Mahatma GandhiVaishnav KumarNo ratings yet

- History's Role in Japanese Horror CinemaDocument16 pagesHistory's Role in Japanese Horror CinemaMiharuChan100% (1)

- The Case of The Missing Mahatma Hindi CinemaDocument28 pagesThe Case of The Missing Mahatma Hindi Cinemasurjit4123No ratings yet

- UntitledDocument4 pagesUntitledTarikNo ratings yet

- Gandhi, The Civilizational Crucible, and The Future of DissentDocument15 pagesGandhi, The Civilizational Crucible, and The Future of DissentEray ErgunNo ratings yet

- Godard and Gorin's Left Politics by Julia LesageDocument25 pagesGodard and Gorin's Left Politics by Julia LesagegrljadusNo ratings yet

- Kashmir Files A PropogandaDocument4 pagesKashmir Files A Propogandaashok_pandey_10No ratings yet

- Writing For Documentary Academic ScriptDocument12 pagesWriting For Documentary Academic ScriptNitin KumarNo ratings yet

- A Divided World: Hollywood Cinema and Emigre Directors in the Era of Roosevelt and Hitler, 1933-1948From EverandA Divided World: Hollywood Cinema and Emigre Directors in the Era of Roosevelt and Hitler, 1933-1948No ratings yet

- Viceroy's House - AnalysisDocument2 pagesViceroy's House - AnalysisAjith PeterNo ratings yet

- Gandhi: From His Humble Beginnings To His Ultimate TriumphDocument4 pagesGandhi: From His Humble Beginnings To His Ultimate TriumphTherese Angelie CamacheNo ratings yet

- Summachar Curiopedia Newsletter 26Document7 pagesSummachar Curiopedia Newsletter 26AKNo ratings yet

- The ServantDocument22 pagesThe ServantOscar CervNo ratings yet

- Birth of Anti-ColonialismDocument49 pagesBirth of Anti-ColonialismNewmedicalcentre Pondy100% (1)

- Films Division - A Repository of History of IndiaDocument5 pagesFilms Division - A Repository of History of IndiasayhaslaysNo ratings yet

- The Globalization of Bollywood...Document20 pagesThe Globalization of Bollywood...hk_scribdNo ratings yet

- The Roy-Lenin Debate On Colonial Policy: A New InterpretationDocument9 pagesThe Roy-Lenin Debate On Colonial Policy: A New InterpretationGabriel QuintanilhaNo ratings yet

- Consumer Behaviour-Impact of Western Cinema On Indian YouthDocument8 pagesConsumer Behaviour-Impact of Western Cinema On Indian YouthShahrukh Soheil Rahman100% (1)

- Lecture 5Document25 pagesLecture 5satyabashaNo ratings yet

- Lect12 Photodiode DetectorsDocument80 pagesLect12 Photodiode DetectorsVishal KumarNo ratings yet

- Lect1 General BackgroundDocument124 pagesLect1 General BackgroundUgonna OhiriNo ratings yet

- CS195-5: Introduction To Machine Learning: Greg ShakhnarovichDocument33 pagesCS195-5: Introduction To Machine Learning: Greg ShakhnarovichsatyabashaNo ratings yet

- Elementary Data Structures: Steven SkienaDocument25 pagesElementary Data Structures: Steven SkienasatyabashaNo ratings yet

- Linear Algebra For Computer Vision - Part 2: CMSC 828 DDocument23 pagesLinear Algebra For Computer Vision - Part 2: CMSC 828 DsatyabashaNo ratings yet

- 4 Lecture 4 (Notes: J. Pascaleff) : 4.1 Geometry of V VDocument5 pages4 Lecture 4 (Notes: J. Pascaleff) : 4.1 Geometry of V VsatyabashaNo ratings yet

- Lecture 4Document9 pagesLecture 4satyabashaNo ratings yet

- Lecture 3Document18 pagesLecture 3satyabashaNo ratings yet

- Lecture 4Document9 pagesLecture 4satyabashaNo ratings yet

- Topics To Be Covered: - Elements of Step-Growth Polymerization - Branching Network FormationDocument43 pagesTopics To Be Covered: - Elements of Step-Growth Polymerization - Branching Network FormationsatyabashaNo ratings yet

- Image Formation in Man and MachinesDocument45 pagesImage Formation in Man and MachinessatyabashaNo ratings yet

- Image Analysis: Pre-Processing of Affymetrix ArraysDocument14 pagesImage Analysis: Pre-Processing of Affymetrix ArrayssatyabashaNo ratings yet

- Lecture 3Document4 pagesLecture 3satyabashaNo ratings yet

- Brightness: and CDocument39 pagesBrightness: and CsatyabashaNo ratings yet

- Program Analysis: Steven SkienaDocument20 pagesProgram Analysis: Steven SkienasatyabashaNo ratings yet

- Lecture 2Document3 pagesLecture 2satyabashaNo ratings yet

- Asymptotic Notation: Steven SkienaDocument17 pagesAsymptotic Notation: Steven SkienasatyabashaNo ratings yet

- History British I 20 Wil S GoogDocument709 pagesHistory British I 20 Wil S GoogsatyabashaNo ratings yet

- Lecture 2Document15 pagesLecture 2satyabashaNo ratings yet

- A Christopher Hitchens Bookshelf-9Document2 pagesA Christopher Hitchens Bookshelf-9satyabashaNo ratings yet

- Genomic Signal Processing: Classification of Disease Subtype Based On Microarray DataDocument26 pagesGenomic Signal Processing: Classification of Disease Subtype Based On Microarray DatasatyabashaNo ratings yet

- Reading Gandhi (2012)Document333 pagesReading Gandhi (2012)SS QuizzersNo ratings yet

- The Lahore Resolution PDFDocument86 pagesThe Lahore Resolution PDFHyder Ahmadi100% (2)

- BesantDocument3 pagesBesantAbhishek ChaturvediNo ratings yet

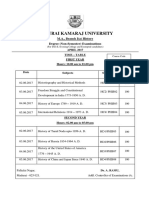

- PG Time Table April 2017Document38 pagesPG Time Table April 2017Jp PradeepNo ratings yet

- ALLINONEDocument4 pagesALLINONEVeer SolankiNo ratings yet

- Mahābhārata in Hindu Tradition - Hinduism - Oxford BibliographiesDocument30 pagesMahābhārata in Hindu Tradition - Hinduism - Oxford BibliographiesMahendra DasaNo ratings yet

- Social SampleDocument59 pagesSocial SampleSunil Abdul SalamNo ratings yet

- Gandhi As A Leader 2-FinalDocument37 pagesGandhi As A Leader 2-FinalChandni Verma100% (2)

- Constitution of India As A Reflection of The Ideals of The Indian National MovementDocument3 pagesConstitution of India As A Reflection of The Ideals of The Indian National MovementYasi NabamNo ratings yet

- Module 17 For Week 17Document10 pagesModule 17 For Week 17Khianna Kaye PandoroNo ratings yet

- Employment News 15 To 21 PDFDocument32 pagesEmployment News 15 To 21 PDFfilmfilmfNo ratings yet

- Gandhis Vision of Ramarajya A Critique PDFDocument13 pagesGandhis Vision of Ramarajya A Critique PDFLekshmi NarayananNo ratings yet

- 543 2207 1 PBDocument3 pages543 2207 1 PBLari Sandor LyngdohNo ratings yet

- GandhiDocument20 pagesGandhiAnbel LijuNo ratings yet

- 3350 Assignmemt 3 MercyDocument9 pages3350 Assignmemt 3 MercyFrancis MbeweNo ratings yet

- The Sarvodaya Samaj and Beginning of Bhoodan MovementDocument6 pagesThe Sarvodaya Samaj and Beginning of Bhoodan MovementAnonymous CwJeBCAXpNo ratings yet

- Ehi 01Document6 pagesEhi 01Khual NaulakNo ratings yet

- Mahatma Gandhi BiographyDocument3 pagesMahatma Gandhi BiographyAlena JosephNo ratings yet

- Decolonization - EssayDocument5 pagesDecolonization - EssayPetruţa GroşanNo ratings yet

- Dismantling Sainthood: Ambedkar On Gandhi: Anand RanganathanDocument25 pagesDismantling Sainthood: Ambedkar On Gandhi: Anand RanganathanVipin DixitNo ratings yet

- Social PsychologyDocument15 pagesSocial PsychologyOshinNo ratings yet

- Hind Swaraj - M.K. GandhiDocument2 pagesHind Swaraj - M.K. GandhiDinesh DewasiNo ratings yet

- No Mere Slogans - On Isabel Wilkerson's "Caste - The Origins of Our Discontents" - Los Angeles Review of BooksDocument11 pagesNo Mere Slogans - On Isabel Wilkerson's "Caste - The Origins of Our Discontents" - Los Angeles Review of BooksShayok SenguptaNo ratings yet

- Topic GandhiDocument3 pagesTopic GandhiVANSHIKA AGARWALNo ratings yet

- Modern India History MCQDocument10 pagesModern India History MCQHarsh Khulbe100% (1)

- INDIGODocument3 pagesINDIGOGod is every whereNo ratings yet

- How To Write Summer Holiday Homework in SanskritDocument5 pagesHow To Write Summer Holiday Homework in Sanskritbcdanetif100% (1)

- Gandhi WorksheetDocument2 pagesGandhi WorksheetPaul RodríguezNo ratings yet

- Social Science EM MCQ's Savi VijethaDocument72 pagesSocial Science EM MCQ's Savi VijethaManju NathNo ratings yet

Travails of The Nation: Some Notes On Indian Documentaries

Travails of The Nation: Some Notes On Indian Documentaries

Uploaded by

satyabashaOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Travails of The Nation: Some Notes On Indian Documentaries

Travails of The Nation: Some Notes On Indian Documentaries

Uploaded by

satyabashaCopyright:

Available Formats

CTTE19206.

fm Page 175 Thursday, January 6, 2005 7:48 PM

Third Text, Vol. 19, Issue 2, March, 2005, 175185

Travails of the Nation

Some Notes on Indian Documentaries

1. A voluminous literature

has grown up around what

constitutes

documentaries, and I

suspect that the revival

which documentaries are

presently enjoying, in

countries such as the

United States and India,

will lead to further

speculation on the forms

that documentaries will

take in the future.

Documentary became a

movement in Britain in the

1930s, and documentaries

have ever since been

understood to be vehicles

of social comment and

change. The sense that

John Grierson conveyed

about the documentary,

when apropos of Robert

Flahertys Moana, he spoke

of it as a visual account of

the daily life of a

Polynesian youth that had

documentary value still

remains with us today. See

Forsyth Hardy, ed,

Grierson on Documentary,

Faber & Faber, London,

1979, p 11.

2. See the useful discussions

in Erik Barnouw and S.

Krishnasway, Indian Film,

2nd edn, Oxford

University Press, New

York, 1980, pp 4358 and

Prem Chowdhry, Colonial

India and the Making of

Empire Cinema: Image,

Ideology and Identity,

Manchester University

Press, Manchester, 2000,

pp 1738.

3. Barnouw and

Krishnaswamy, ibid, p 43.

4. Ibid, p 123.

Vinay Lal

Though Bollywood has become synonymous with Indian cinema to the

uninitiated, there are an ample number of other traditions of filmmaking in India, not least of which is a tradition of political documentaries.1 The Indian independence movement, led in the 1920s and 1930s

by Mohandas Gandhi, was the subject of the first concentrated phase of

documentary film-making. The bulk of these films, however, never

received any public screening. The Cinematograph Act of 1918 introduced censorship in India, and the Indian Cinematograph Committee of

1928, while urging the censors to curb their enthusiasm for bringing

films before the cutting-board, unequivocally reaffirmed the moral

necessity of censorship, especially in a country among whose natives, as

many British in India believed, passions reigned supreme.2 The various

regional censor boards did not only certify Indian films for exhibition

but also regulated the entry of foreign films into India and their public

screenings. Indeed, cheap American films, which were viewed (in the

words of one English clergyman) as engaging in outright sensationalism,

proliferating in daring murders, crimes and divorces, and, more pointedly, as degrading white women in the eyes of Indians, were especially

targeted for censorship.3 By the mid-1930s, Gandhi had become a figure

of worldwide veneration; moreover, the Government of India Act of

1935, which allowed some measure of autonomy to Indians, implicitly

recognised that the Indian objective of full independence was no longer a

mere utopian dream. Consequently, numerous documentaries that had

been banned were now made available for public screenings, among

them Mahatma Gandhis March for Freedom (Sharda Film Co),

Mahatma Gandhis March, March 12 (Krishna Film Co), and Mahatma

Gandhi Returns from the Pilgrimage of Peace (Saraswati).4

While the history of Indian documentary film-making is well beyond

the ambit of this paper, it is instructive to those who might wish to think

about political documentaries in contemporary India. Censorship

remains, as will be seen, the most pressing problem for documentary

film-makers; and the irony is further compounded when we consider, for

example, that Gandhi is as much of a pariah figure to the modern Indian

Third

10.1080/0952882042000328098

CTTE19206.sgm

0000-0000

Original

Taylor

202005

19

vlal@history.ucla.edu

VinayLal

00000March

Text

and

&

Article

Francis

(print)/0000-0000

Francis

2005

Ltd

Ltd

(online)

Third Text ISSN 0952-8822 print/ISSN 1475-5297 online 2005 Kala Press/Black Umbrella

http://www.tandf.co.uk/journals

DOI: 10.1080/0952882042000328089

CTTE19206.fm Page 176 Thursday, January 6, 2005 7:48 PM

176

state as he was to the government of British India. Two recent documentaries, Final Solution (2004) and War and Peace (Jang aur Aman,

2002), both of which have earned accolades around the world,5 furnish

an ample introduction to the manner in which Indian film-makers seek

to understand the resurgence of Hindu militancy, the marked drift

towards zero-sum politics which is everywhere becoming characteristic

of the modern nation-state, the normalisation of politics, and more

broadly the political culture of the Indian state. In late February 2002,

following the attack, which left nearly sixty people dead and many more

with severe burn injuries, by still undetermined assailants on a train near

Godhra station in Gujarat carrying Hindu devotees returning from

Ayodhya, a pogrom was unleashed upon the Muslim population of

Gujarat. Scores of journalists and eyewitnesses, and at least a dozen

investigative committees, have documented the orchestrated violence

that took 2000 (largely Muslim) lives, rendered 150,000 people homeless, and decimated entire Muslim families and communities.6 Armed

gangs with lists of Muslim-owned houses and shops freely roamed the

streets, committing arson and pillage; policemen stood by idly while

women were speared in their genitals, or systematically raped by one

man after another before being hacked to pieces. Murder and mayhem

continued for three days, unchecked by the forces of the state except for

the brave conduct of a few solitary policemen whose only reward was

reprimands, before any attempt was made to bring the situation under

control. Not until a month later had the violence subsided sufficiently

that one could aver that the city was no longer hostage to murderous

criminals and their political patrons.

21

Final Solution, 2004, Rakesh Sharma

5. Final Solution, directed

by Rakesh Sharma, is the

first Indian film ever

nominated for the

Grierson Award, one of

the most notable awards

conferred on

documentary films; it is

also the recipient of

awards at film festivals

in Berlin, Hong Kong,

and Zanzibar. War and

Peace is the recipient of

awards at film festivals

in Tokyo, Zanzibar,

Karachi, Mumbai,

Sydney, and elsewhere.

6. A dozen investigative

reports have been put

together in The Gujarat

Pogrom: Indian

Democracy in Danger,

Indian Social Institute,

New Delhi, 2002; see

also Siddharth

Varadarajan, ed,

Gujarat: The Making of

a Tragedy, Penguin, New

Delhi, 2002.

Final Solution, 2004, Rakesh Sharma

CTTE19206.fm Page 177 Thursday, January 6, 2005 7:48 PM

177

Final Solution, 2004, Rakesh Sharma

7. See Vinay Lal, The History

of History: Politics and

Scholarship in Modern

India, Oxford University

Press, New Delhi, 2003, pp

14185.

Barely two or three months had elapsed before the first documentaries on the Gujarat killings were beginning to circulate. Gopal Menons

Hey Ram! Genocide in the Land of Gandhi allows the victims a dominant voice: here a retired man who describes how his forty years of

savings went up in smoke when rioters ransacked his home, there a

woman who recalls her pregnant niece, whose stomach was slit open and

her foetus tossed into the fire. But Menons film illustrates all the difficulties to which political documentaries, particularly those made to meet

the exigencies of a situation, are susceptible. The opening frames of the

film establish what Menon construes as the genealogy of the violence in

Gujarat, namely the conflict over the Babri Masjid in Ayodhya, a

sixteenth-century mosque eventually destroyed by Hindu militants in

December 1992, that was claimed by them to have previously housed a

Hindu temple.7 Menons film offers no insight on the rise of Hindu militancy, the ideology of Hindu supremacy, caste and class politics in

Gujarat, or the relationship of communal violence to urbanisation. It is

true that the people aboard the train that was partly set ablaze at

Godhra were Hindus and their families returning from Ayodhya, but

Menon entirely overlooks the troubled history of HinduMuslim relations in Gujarat over the last four decades, and is unable to offer any

account of why the conflagration should have commenced in Gujarat.

Most viewers would have thought that the words Gandhi and genocide stand in stark opposition, but in Menons film they occupy much

too easily, and inexplicably from the point of view of the common

viewer, the same space. One cannot doubt that the film-maker intends to

evoke the mournful irony that the very same state which proudly claims

Gandhi, the principal practitioner and theorist of non-violent resistance

CTTE19206.fm Page 178 Thursday, January 6, 2005 7:48 PM

178

8. Shahid Amin, Gandhi as

Mahatma: Gorakhpur

District, Eastern University

Press, 19212, in Selected

Subaltern Studies, eds

Ranajit Guha and Gayatri

Chakravorty Spivak,

Oxford University Press,

New York, 1988, pp 288

346.

9. Achyut Yagnik, The

Pathology of Gujarat,

Seminar, no 513, 2002,

pp 1922. The entire issue

is devoted to the Gujarat

killings.

in modern times, as its native son should have been the breeding ground

for sustained eliminationist violence against Muslims. But neither

Gandhi nor Mahatma, the honorific (meaning Great Soul) by which

he was known throughout the world, have ever been words that had

only a monochromatic existence. As far back as 192022, during the

first nationwide non-cooperation movement against the British under

Gandhis leadership, violence was committed in Gandhis name. In the

north Indian town of Chauri Chaura, Indian nationalists burned down a

police station and killed over a dozen Indian policemen while shouting

slogans, Mahatma Gandhi ki jai, Long Live Mahatma Gandhi.8

Gandhi was aghast at these developments, as is, evidently, Menon today.

But that the killings might be waged with ruthless abandon precisely

because in Gandhis Gujarat one expected otherwise is a consideration

which seems far removed from the film-makers mind.

As Menons camera moves from one victim to another, it begins to

read much like one of the many first-hand, partly investigative reports

that surfaced amidst the killings and in the immediate aftermath. The

film as sociopolitical document does not necessarily have the advantage

of immediacy, and it might be handicapped by lack of distance. More

complex is Bombay film-maker Suma Jossons Gujarat: Laboratory of

Hindu Rashtra (2002). Josson charts the ascendancy of Hindutva, the

ideology of Hindu supremacy that seeks to distil Hinduism into its

purest essence, and interviews with its advocates, as with civil rights

activists and political opponents of Hindutva, furnish some backdrop to

understanding how Gujarat has become the site of efforts to secure a

Hindu nation (rashtra). Jossons film adds more sociological depth to

the narrative of Hindu violence in Gujarat. But that question again

surfaces: just how did Gujarat, the land of Gandhi, become so hospitable to advocates of Hindu militancy? One might have thought that the

legacy of Gandhi would have worked to make Gujarat, which also

boasts higher degrees of urbanisation, literacy, and industrial development than most other Indian states, into a model state for the rest of the

country.9 Yet Gujarat has been subject to insistent communal strife.

These apparent anomalies are left unexplained, which is again inexplicable considering the argument advanced that Gujarat represents the laboratory of the Hindu nation. If, as we know, the word laboratory exists

on multiple registers, we must perforce ask how far Gujarat mirrors the

nation, and what Gujarat portends for the future. In his own way,

Gandhi turned Gujarat into a laboratory for the perfection of his

doctrine of satyagraha, non-violent resistance. How far are the advocates of Hindutva playing on this legacy?

Rakesh Sharmas The Final Solution (2004) is easily the most capacious of the handful of documentaries on the Gujarat killings. Though it

has travelled widely on the international film festival circuit since it was

completed in early 2004, the film still awaits a certificate from the Censor

Board of India. In denying the film certification, the censors objected that

the film promotes communal disharmony among Hindu and Muslim

groups and presents the picture of Gujarat riots in a way that it may

arouse the communal feelings and clashes among Hindu [and] Muslim

groups. They noted, in particular, that the film is detrimental to

national unity and integrity, and that certain dialogues involve defamation of individuals or body of individuals. Entire picturisation is highly

CTTE19206.fm Page 179 Thursday, January 6, 2005 7:48 PM

179

10. Personal email

communication from

Rakesh Sharma, 25

September 2004.

11. We Have No Orders to

Save You: State

Participation and

Complicity in Communal

Violence in Gujarat,

Human Rights Watch,

14:3, April 2002.

12. George J Andreopolulos,

ed, Genocide: Conceptual

and Historical Dimensions,

University of Pennsylvania

Press, Philadelphia, 1994,

pp 22933.

13. For a more elaborate

interpretation along these

lines, see Vinay Lal, On

the Rails of Modernity:

Communalisms Journey in

India, Emergences, 12:2,

November 2002, pp 297

311.

14. As reported in the Times of

India, 2 March 2004 and

other dailies: see The

Gujarat Pogrom, op cit, pp

6, 126.

provocative and may trigger off unrest and communal violence. State

security is jeopardized and public order is endangered if this film is

shown.10 Considering that, as the reams of evidence collected by various

investigative groups have indubitably established, the killings were

orchestrated with the complicity of the state,11 the argument that Final

Solution jeopardises state security would have been comical if it were

not macabre. Yet, the words Final Solution are clearly calculated to

provoke, and in the course of the film Sharma seeks, and not always

obliquely, to establish similarities with Nazi Germany. The authority of

the Oxford English Dictionary is invoked as the word genocide is

splashed across the screen, followed by the definition of genocide

contained in the UN Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of

the Crime of Genocide (1948). Whether the dialectic of the text, the

image, and commonsense works, in this instance, to the directors

advantage is disputable. Article 2 of the Convention describes genocide

as various acts of injury, harm, and killing committed with intent to

destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnical, racial or religious

group, as such.12 Were the perpetrators of the killings intent on destroying Muslims as a group, or were they keen that the killing of some

Muslims should serve as an object lesson to other Muslims and even,

from the standpoint of the killers, to Hindus especially Hindus who, led

astray by the tolerant traditions of their faith and the non-violent teachings of Gandhi, are construed as soft, effeminate, and incapable of

comprehending that Islam is incapable of existing alongside another faith

in peace and harmony?13 The textual definition of genocide hobbles the

film-makers case, but in some conversational sense of the term to which

the images speak the word genocide does not seem entirely misplaced.

In its longest version, the film runs for 3 hours 40 minutes; however,

since audiences are not habituated to documentaries of this length,

Sharma generally screens one of two shorter versions, either 100 minutes

or 148 minutes in length. Part I, entitled Pride and Prejudice, offers

insights into Hindutvas vociferous attempts to instil pride in an

unabashedly militant conception of their faith among Hindus, and the

price that the Muslims of Gujarat have had to pay to make Hindus feel

secure in their own homeland. Initial shots of Gaurav Yatra, or a

Hindu pilgrimage of pride, are interspersed with interviews of schoolboys and their teachers; the camera then moves on to the refugee camps

where nearly 150,000 victims of the pogrom were lodged. Even as

victims recount the brutalities they survived, or were forced to witness,

the camera cuts, with chilling effect, to a speech by Narendra Modi, the

Chief Minister of Gujarat, who pompously declaimed on first being told

of the massacres, Every action has an equal and opposite reaction.14

The subsequent three parts, The Terror Trail, Hate Mandate, and

Hope and Despair, are similarly structured. Occasional footage from a

Gujarat Government VCD on Godhra, snippets from the Concerned

Citizens Tribunal Report, and coverage of speeches by Narendra Modi

and other ideologues of Hindutva, such as Praveen Togadia and the religious leader Acharya Dharmendra, punctuate scores of interviews with

victims and their families, perpetrators and their patrons, and bystanders. Among the very first shots with which Final Solution opens is of a

schoolboy, perhaps six or seven years old, describing the mutilation of

his father and the rape of his aunt; and, as the film closes, the boy

CTTE19206.fm Page 180 Thursday, January 6, 2005 7:48 PM

180

15. The definite piece remains

Ashis Nandys Final

Encounter: The Politics of

the Assassination of

Gandhi, in At the Edge of

Psychology: Essays in

Politics and Culture,

Oxford University Press,

Delhi, 1980, pp 7098.

appears in an extended conversation with Sharma himself. He describes

all Hindus as bad, and says, quite unbelievably, that he is prepared to

kill them all. Sharma reminds him that he, too, is a Hindu. We witness

the boy struggling with this difficult truth: if the film-maker before him

appears to be a nice man, then all Hindus surely do not stand

condemned. But if they do, then Sharma cannot be the Hindu he claims

to be: this appears to be, logically speaking, the easier reality to accept. If

framing devices are ordinarily intended to furnish closure, Sharma resolutely refuses such comforts; moreover, by concluding with excerpts

from his conversation with the schoolboy, he draws sustained attention

to the question, generally little explored in India, of what the voices of

children tell us about communalism and how they mediate unspoken

social truths.

It has become customary, in political documentaries, such as those

made on the Gujarat killings or on the movement to prevent the

damming of the river Narmada, to interview civil rights leaders, human

rights lawyers, peace activists, liberal academics, and others whose sane

and politically resistant voices in the name of peace, human dignity, and

justice provide assurance, howsoever slight, that the institutions of civil

society are not entirely corrupt and that some modicum of decency

remains amidst flagrant and openly contemptuous displays of murderous and intimidating violence. Rakesh Sharma offers no such placebos:

there are no candlelight vigils in the memory of victims, nor does he

show any street demonstrators holding placards with the usual slogans

demanding justice and insisting on peace not war. Some might argue

that there is no effective political intervention that does not hold out

hope for the future, and that Sharmas evident aim in shaming, exposing,

and penetrating Hindutva is at odds with his failure to show resistance

to Hindutva at work. I wish to suggest, however, that Sharmas evident

intent in showing the violence unadorned, in all its nakedness, augurs a

new and important stance on the part of the Indian documentary filmmaker. It is remarkable, too, as a clip from Part II, quite inexplicably

deleted from a shorter version of the film, unequivocally suggests how

much the spectre of Gandhi still looms large over those who are inclined

to see him as effeminate old man whose death was necessary to pave the

way for the emergence of India as a muscular Hindu nation-state.15 One

victim of the massacre at the Gulbarg Housing Society in Ahmedabad

remarks, They say Gujarat is Gandhis land, the home of non-violence.

But it [the violence, as policemen stood by] was bestial. It was terrorism. Sharmas camera then cuts to a speech by Praveen Togadia, a

physician by training who might reasonably be dubbed the Hindu

doctor of death, so palpable is his hatred of the Muslim and his embrace

of violence: Terror was unleashed at Godhra station because this country follows Gandhi. We dont want Mahatma Gandhis non-violence. It

is Gandhis non-violence, Togadia argues, that compelled the Hindu to

kneel before the Muslim, and fed the Muslims habit of engaging in

terrorist activity. As I have previously remarked, the fear of Gandhi ties

the modern advocate of Hindu militancy across decades to the British

who came to see Gandhi as an unusual, determined, and irrational foe of

the colonial state.

Sharmas achievement, considerable as it is, is not unique. At least

among documentary film-makers working in the socialist tradition,

CTTE19206.fm Page 181 Thursday, January 6, 2005 7:48 PM

181

16. Ronita Torcato, Through

the Viewfinder, Hindu

Magazine, 14 April 2002,

online at: http://

www.hindu.com/thehindu/

mag/2002/04/14/stories/

2002041400290500.htm

17. Online at: http://

www.jang.com.pk/

thenews/spedition/nuclear/

feature1.htm

Anand Patwardhan has no peers in India. His career has spanned three

decades, and his oeuvre includes films on the Bombay textile strike of

198283, political prisoners, Indian farmworkers in British Columbia

and their efforts to unionise, the dispute over the now-destroyed Babri

Masjid, the politics of masculinity and sexuality in contemporary India,

the controversy over the damming of the Narmada river, and Indias

nuclear testing. Patwardhan has been there to document the principal

milestones in the political life of the nation over the last three decades,

and it would be no exaggeration to suggest that Indian documentary

film-makers, even when they have surpassed him, have initially had to

work in his shadow. Patwardhan has remained resolutely uncompromising both in his objections to Hindu militancy and in adhering to a rigorous critique of the culture of violence generated by the political

arrangements of the modern Indian state, and his films have repeatedly

encountered the opposition of the Censor Board. Indian authorities engineered the removal of his epic film, Jang aur Aman (War and Peace,

2002) as the inaugural film of the Kolkata Film Festival in May 2002,

three months after officials at the American Museum for Natural

History (New York) shamefully succumbed to the pressure of supporters

of Hindu militancy in the United States and postponed scheduled screenings of Patwardhans films.16 My film is based on the Gandhian philosophy of non-violence, says Patwardhan. It exposes the political

hypocrisies of India, Pakistan and the United States regarding the

nuclear issue. They have a problem with the way I have put forward my

argument. But [they] cannot point a finger at the factual data I have used

in the film as it is true. An essay by Patwardhan, entitled How We

Learned to Love the Bomb, is more explicit in its denunciation of the

obscenity of nuclear armaments and does not mince words: I now have

the same feeling of disbelief at the moral bankruptcy and intellectual

idiocy of a nation that is mindlessly euphoric about its acquisition of

weapons of mass destruction.17

Jang aur Aman, though largely an exploration of the political climate

of India and Pakistan following the nuclear testing by both countries in

May 1998, draws on the precedent created by the nuclear bombing of

Hiroshima and Nagasaki, and Patwardhan is just as daring in his criticism of the aggressiveness of the American military and nuclear machine

as he is of the nuclear pretensions of India and Pakistan. Advocates of

nuclearism within the Indian and Pakistan militaries are allowed a voice

in Jang aur Aman but this is all the more effective because, when

placed in juxtaposition with the immense problems of the poor in both

countries, and particularly of the rural populations around the test sites

and the uranium mines, the military perspective begins to look shortsighted, even demented. Yet Patwardhan understands that the nuclear

ambitions of both states have widespread support among diverse strata

of society, and not merely among rabid communalists and the supporters of Gandhis assassin, Nathuram Godse. Achievement in this domain

is viewed as an index of technological prowess, and many people have

come to accept the view that nothing earns a nation-state respect in the

world as much as its nuclear status. Both in India and Pakistan, as Jang

aur Aman poignantly reminds us, the successful nuclear tests of 1998

were celebrated on the streets with explosions of firecrackers and the

distribution of sweets.

CTTE19206.fm Page 182 Thursday, January 6, 2005 7:48 PM

182

Patwardhan has been active on behalf of the rights of the urban poor,

slum-dwellers, refugees, the industrial proletariat, tribals, and political

dissenters; and while he works, in many respects, from the periphery of

Indian society, he retains a discerning eye for the gravity of politics.

Though his 1990 film, Ram Ke Naam, or In the Name of Ram, an

exploration of the controversy over the Babri Masjid before the mosque

was torn down by militant Hindus in December 1992, might be said to

have earned him very wide recognition, Patwardhan had already earned

a considerable reputation for himself with films such as Prisoners of

Conscience (1978, 45 min). Here Patwardhan offered a withering

critique of the internal emergency imposed by Indira Gandhi from 1975

to 1977, which led to the incarceration without trial of 100,000 people;

however, as the film plainly makes clear, these were not the only prisoners of conscience in India. Political issues have generally been at the

forefront of Patwardhans work, and in 1995 he entered into the raging

debate over the Sardar Sarovar project which, when completed, will

have displaced not less than 150,000 people (largely adivasis), and possibly many more. Patwardhans Narmada Diary (co-directed with Simantini Dhuru, 60 minutes) focuses on the efforts of the Narmada Bachao

Andolan, or Save the Narmada Movement, to make the economic,

social, cultural, indeed moral costs of development, to which state planners are oblivious, widely known.

Among Patwardhans films, Pitra, Putra, aur Dharmayuddha, known

in the English-speaking world as Father, Son, and Holy War (1994), has

been of particular interest to students of cinema and observers of

contemporary Indian life. Completed shortly after the destruction of the

Babri Masjid and the bomb blasts that tore apart Bombay in early 1993,

Patwardhan attempts in this daring film of two parts to weave together a

narrative on political violence that considers the nexus between communalism, the changing culture of the contemporary Hindi film, violence

towards women in many domains of Indian society, vernacular forms of

masculinity, and other aspects of Indian society and culture. Patwardhan

is nuanced enough to understand, unlike some other liberal and secular

commentators, that communalism cannot merely be viewed as the logical outcome of illiteracy and deep-seated traditions, and some of the

films most touching moments are seen in the interviews conducted with

working-class women who are firmly persuaded that there is no inseparable gulf between Hindus and Muslims and that tensions between

the two communities are greatly exploited by politicians. Indeed,

Patwardhans suggestion, borne out by many scholarly studies, is that

the educated are more attracted by communal thinking, and the conceit

that the Hindu tradition is a spectacular and unrivalled repository of the

worlds timeless truths sometimes leads the educated Hindus to embrace

absurdities. Patwardhans camera takes us to a Hindu temple in south

India where a ceremony is held for childless couples whose greatest

desire is to have progeny, and it then lingers on a highly educated couple

(with university degrees from Britain) who state, with the utmost seriousness, that the ritual chanting of the Vedas produces sonic vibrations

that can render a barren woman fertile. Hindu women, the viewers are

told with perfect assurance, commingle freely with their men, and unlike

Muslim women have not been held back by obscurantism and repressive

traditions. Though there is something comical in the argument that the

CTTE19206.fm Page 183 Thursday, January 6, 2005 7:48 PM

183

highest truths of physics were all anticipated in the Vedas, this supposed

insight has a firm place in middle-class Indian consciousness. We have

here entered the domain, not of the irrational, but of the hyper-rational.

Precisely because Father, Son, and Holy War is Patwardhans most

ambitious film, it is also emblematic of the conceptual and political

shortcomings of Patwardhans firmly liberal and humanistic worldview.

A crude distinction between matriarchy and patriarchy furnishes the

framework for Patwardhans cinematic observations, and Patwardhan

overlooks the fact that didacticism is often cinemas weakest point, just

it is of poetry. When Patwardhan revels in the detail, in (to use Clifford

Geertzs famous phrase) the thick description of phenomena, he is brilliantly lyrical and suggestively transgressive. His roving camera works by

association: body-building contests, street vendors peddling herbs guaranteed to embolden the penis, and middle-class boys wildly enthused by

Rambo are drawn, with a considerable degree of conviction, into the

same orbit of masculinity. But when Patwardhans camera ceases to do

its walk, he begins to falter. Viewers are led to believe that matriarchy

engulfed the entire world in remote antiquity before men, the hunters,

began to assert their presence and change the rules governing most societies. This thesis of the matriarchal origins of cultures does not, of

course, originate with Patwardhan, but he seems quite unaware of the

depth and breadth of feminist scholarship and of the difficulties that

some strands of feminist scholarship not to mention other scholars

who are entirely hostile to what are viewed as ahistorical and romantic

conceptions of the early history of humankind have with sketchy representations of supposed matriarchal pasts.

43

Father

War

andSon

Peace

and (Jang

Holy War,

aur Aman,

1994, Anand

2002), Anand

Patwadhan

Patwadhan

Father Son and Holy War, 1994, Anand Patwadhan

CTTE19206.fm Page 184 Thursday, January 6, 2005 7:48 PM

184

War and Peace (Jang aur Aman, 2002), Anand Patwadhan

Patwardhans understanding of patriarchy is not more sophisticated,

and the assumption remains that one can write a seamless history of

patriarchy however much it might be dressed up, disguised, deformed,

or diluted. Patwardhan finds nearly every aspect of Indian culture deeply

implicated in the workings of patriarchy, and at times it appears that the

speeches of the Bal Thackeray, the rantings of a Sadhvi Ritambhara or

Uma Bharati, the sexual fantasies of young Indian men who fill the

countrys cinema halls, the street culture of many Indian cities with their

roving groups of young men for whom any young or attractive woman is

reasonable prey, the fears of impotence that quacks exploit with colourful public demonstrations of the aphrodisiac effects of Indian herbs, the

sexual molestation and rape of women in communal conflicts, and the

deeply protective culture of Rajput men are all expressions of one single

tale of a conflicted, thwarted, and emasculated male sexuality. One has

the impression that Patwardhan does not always quite think through his

theses, nor is he fully aware of the politics and regimes of representation;

and yet, in his understanding of the sexual politics of resurgent Hindu

communalism, Patwardhan remains Indias most astute and daring

documentary film-maker and one of the countrys most sensitive

commentators. Again, Patwardhan conflates patriarchy with masculinity, but it is remarkable that he should have zoomed in on masculinity,

long before anyone in India (or, for that matter, almost anywhere else)

had appropriated it as a fitting subject of scholarly inquiry and cultural

commentary.

Though no documentary in India has garnered anything remotely

resembling the visibility attendant upon Michael Moores Fahrenheit 9/

11, a rare enough phenomenon even in the United States, Indian documentary film-makers are now poised to take a critical place in the

CTTE19206.fm Page 185 Thursday, January 6, 2005 7:48 PM

185

18. See Vinay Lal, Too Deep

for Deep Ecology: Gandhi

and the Ecological Vision

of Life, in Hinduism and

Ecology: The Intersection

of Earth, Sky, and Water,

eds C K Chapple and M E

Tucker, Center for the

Study of World Religions,

Harvard Divinity School,

Cambridge, MA, 2000,

pp 183212.

debates that have become central to Indian politics and the most pressing socioeconomic and cultural issues of the day. Documentaries have

become, as well, the sites for a radical new political aesthetics, as the

films of Amar Kanwar so provocatively suggest. To Remember (2003)

has no soundtrack: shot in New Delhis Birla House, where Gandhi was

assassinated on 30 January 1948, this very short film renders homage to

Gandhi and the people who, in visiting this national shrine, remember

his spirit. It is no accident that Kanwar deploys silence to enter into

Gandhis spirit: silence was one of the many idioms through which

Gandhi wrought conversations with himself, stilled his anger, and tested

his commitment to ahimsa (non-violence), and subtly compelled the

British to parley on his terms.18 By contrast, the voice-over occupies a

commanding place in A Season Outside (1998), an exploration, through

the border at Wagah, of the divide between India and Pakistan. That

mythical line, which the two countries fear to transgress, is only twelve

inches wide but, speculates Kanwar, perhaps several miles deep. What

healing powers, asks Kanwar, can non-violence bring to our pain, and

how can non-violence aid in making possible retreat without loss of

dignity? A Night of Prophecy (2002) creates its own distinct space but is

dialectically engaged with similar themes. Gandhi had often stated that

the litmus test of a democracy is how it treats its minorities and its

dispossessed, and Kanwar travels to Maharashtra, Andhra Pradesh,

Nagaland, and Kashmir to film the voices of protest of those who,

whether on account of their caste, religion, or political sensibilities have

found the Indian nation-state to be cruelly inhospitable. Their sadness,

anger, dignity, and spirit of resistance are compelling, and their collective tale has enough music and noise in it that the soundtrack requires

no narrator at all. Kanwars use of the soundtrack is in itself a study in

politics.

Indian documentary film-making has evidently come a long way

from the time, merely a decade or two ago, when the Films Division of

the Government of India monopolised the production and distribution

of Indian documentaries. It is true that no Indian political documentary

can expect a commercial release, and that even screenings on the stateowned Doordarshan or privately owned television channels are rare. In

this respect, whatever the censorship codes, the absence of a viable

distribution network for documentaries, particularly those that are resistant to the political culture of the Indian state and the free-market agendas of Indias corporate and modernising elites, itself constitutes a form

of censorship. Nevertheless, there is every reason to believe that a future

awaits Indian documentary film-makers. When, early this year, the organisers of the Mumbai International Film Festival (MIFF) sought to

subject Indian documentaries to the guidelines of an archaic and repressive censorship code, 300 film-makers originated a Campaign Against

Censorship and conducted a six-day film festival that ran concurrently

with MIFF. This campaign has now been reconstituted into a more

permanent forum, Films for Freedom [www.freedomfilmsindia.org],

and one can consequently indulge oneself in the belief that documentary

film-makers will no longer exist at the margins of political and artistic

activity in India.

AN AGREEMENT FOR THE TRANSFER OF COPYRIGHT

IN RELATION TO THE CONTRIBUTION OF YOUR ARTICLE (THE ARTICLE) ENTITLED:

BY:

WHICH WILL BE PUBLISHED IN C-TTE

In order to ensure both the widest dissemination and protection of material published in our Journal,

we ask authors to assign the rights of copyright in the articles they contribute. This enables

Kala Press/Black Umbrella ('us' or 'we') to ensure protection against infringement. In consideration of

the publication of your Article, you agree to the following:

1.

You assign to us with full title guarantee all rights of copyright and related rights in your

Article. So that there is no doubt, this assignment includes the assignment of the right to

publish the Article in all forms, including electronic and digital forms, for the full legal term of

the copyright and any extension or renewals. Electronic form shall include, but not be limited

to, microfiche, CD-ROM and in a form accessible via on-line electronic networks. You shall

retain the right to use the substance of the above work in future works, including lectures,

press releases and reviews, provided that you acknowledge its prior publication in the journal.

2.

Our publisher, Taylor & Francis Ltd, shall prepare and publish your Article in the Journal. We

reserve the right to make such editorial changes as may be necessary to make the Article

suitable for publication, or as we reasonably consider necessary to avoid infringing third party

rights or law; and we reserve the right not to proceed with publication for whatever reason.

3.

You hereby assert your moral rights to be identified as the author of the Article according to

the UK Copyright Designs & Patents Act 1988.

4.

You warrant that you have at your expense secured the necessary written permission from

the appropriate copyright owner or authorities for the reproduction in the Article and the

Journal of any text, illustration, or other material. You warrant that, apart from any such third

party copyright material included in the Article, the Article is your original work, and does not

infringe the intellectual property rights of any other person or entity and cannot be construed

as plagiarising any other published work. You further warrant that the Article has not been

previously assigned or licensed by you to any third party and you will undertake that it will not

be published elsewhere without our written consent.

5.

In addition you warrant that the Article contains no statement that is abusive, defamatory,

libelous, obscene, fraudulent, nor in any way infringes the rights of others, nor is in any other

way unlawful or in violation of applicable laws.

6.

You warrant that wherever possible and appropriate, any patient, client or participant in any

research or clinical experiment or study who is mentioned in the Article has given consent to

the inclusion of material pertaining to themselves, and that they acknowledge that they cannot

be identified via the Article and that you will not identify them in any way.

7.

You warrant that you shall include in the text of the Article appropriate warnings concerning

any particular hazards that may be involved in carrying out experiments or procedures

described in the Article or involved in instructions, materials, or formulae in the Article, and

shall mention explicitly relevant safety precautions, and give, if an accepted code of practice

is relevant, a reference to the relevant standard or code.

8.

You shall keep us and our affiliates indemnified in full against all loss, damages, injury, costs

and expenses (including legal and other professional fees and expenses) awarded against or

incurred or paid by us as a result of your breach of the warranties given in this agreement.

9.

You undertake that you will include in the text of the Article an appropriate statement should

you have a financial interest or benefit arising from the direct applications of your research.

10.

If the Article was prepared jointly with other authors, you warrant that you have been

authorised by all co-authors to sign this Agreement on their behalf, and to agree on their

behalf the order of names in the publication of the Article. You shall notify us in writing of the

names of any such co-owners.

11.

This agreement (and any dispute, proceeding, claim or controversy in relation to it) is subject

to English law and the jurisdiction of the Courts of England and Wales. It may only be

amended by a document signed by both of us.

Signed

___________________________________

Print name

___________________________________

Date

___________________________________

You might also like

- Representation of Social Issues in CinemaDocument11 pagesRepresentation of Social Issues in CinemaShashwat Bhushan GuptaNo ratings yet

- KHALISTAN-The Only Solution by Partap SinghDocument140 pagesKHALISTAN-The Only Solution by Partap SinghJamshaidzubairee100% (2)

- Gandhi Review 21178-2Document15 pagesGandhi Review 21178-2beeban kaurNo ratings yet

- Representation of Partition in Hindi Films of The Nehruvian EraDocument8 pagesRepresentation of Partition in Hindi Films of The Nehruvian EraTJPRC PublicationsNo ratings yet

- NEHRUVIAN' CINEMA AND POLITICS - JstorDocument11 pagesNEHRUVIAN' CINEMA AND POLITICS - JstoryuktaamukhiNo ratings yet

- Moving Images of GandhiDocument10 pagesMoving Images of GandhisatyabashaNo ratings yet

- Gandhi - Teachers' Notes Study GuideDocument19 pagesGandhi - Teachers' Notes Study GuideRitu SinghNo ratings yet

- Decolonization - EssayDocument5 pagesDecolonization - EssayPetruţa GroşanNo ratings yet

- Cinematic Representations of Partition of IndiaDocument10 pagesCinematic Representations of Partition of IndiaGlobal Research and Development ServicesNo ratings yet

- China IndiaEPWDocument5 pagesChina IndiaEPWVinay LalNo ratings yet

- 3 4 7 Ecl 047Document4 pages3 4 7 Ecl 047ravishkumar76685No ratings yet

- Revenge, Masculinity and Glorification of Violence in The GodfatherDocument8 pagesRevenge, Masculinity and Glorification of Violence in The GodfathersairaNo ratings yet

- Censorship Madhava - 1Document11 pagesCensorship Madhava - 1Ashish CherukuriNo ratings yet

- The Communists and 1942Document9 pagesThe Communists and 1942Sukiran DavuluriNo ratings yet

- Film As A Tool For War Propaganda Synopsis From World WarDocument6 pagesFilm As A Tool For War Propaganda Synopsis From World WarAnh NguyenNo ratings yet

- Iram Parveen BilalDocument12 pagesIram Parveen BilalSiddharth SaratheNo ratings yet

- Orientalism, Terrorism, Bombay CinemaDocument13 pagesOrientalism, Terrorism, Bombay CinemaPrem VijayanNo ratings yet

- History ProjectDocument8 pagesHistory Projectavik sadhuNo ratings yet

- Alluda MajakaDocument55 pagesAlluda Majakadurga workspotNo ratings yet

- History of Documentary and Short FilmsDocument23 pagesHistory of Documentary and Short FilmsahaanakochharofficialNo ratings yet

- The Majoritarian Politics of Art FilmsDocument10 pagesThe Majoritarian Politics of Art FilmsA.C. SreehariNo ratings yet

- Black Friday 1Document11 pagesBlack Friday 1Jeenit MehtaNo ratings yet

- Films and Religion - An Analysis of Aamir Khan - S PK PDFDocument31 pagesFilms and Religion - An Analysis of Aamir Khan - S PK PDFYuraine EspantoNo ratings yet

- Aamir Khans PK PDFDocument31 pagesAamir Khans PK PDFSushil KumarNo ratings yet

- Romancing India On Screen: Falling in LineDocument1 pageRomancing India On Screen: Falling in LineVishal MaheshwariNo ratings yet

- Inventing A Genocide The Political AbuseDocument7 pagesInventing A Genocide The Political AbuseBobby ShaNo ratings yet

- Gandhi A Movie Review by Khalid MonerDocument2 pagesGandhi A Movie Review by Khalid MonerAadhitya NarayananNo ratings yet

- Azadi - Arundhati RoyDocument88 pagesAzadi - Arundhati RoyUmar Kanth100% (1)

- Gandhi 1982Document19 pagesGandhi 1982Dev AroraNo ratings yet

- PDFDocument335 pagesPDFghalib86No ratings yet

- The Best StoryDocument6 pagesThe Best StoryEslyium AvalonNo ratings yet

- 2013-10 - 0148 PinjarDocument5 pages2013-10 - 0148 PinjarBilal ShahidNo ratings yet

- Gandhi: Assigment-4Document5 pagesGandhi: Assigment-4Sankar AmiNo ratings yet

- A Second Evil Empire The James Bond Series Red CDocument19 pagesA Second Evil Empire The James Bond Series Red CmandlisasikiranNo ratings yet

- Mallhi Illusion of SecularismDocument15 pagesMallhi Illusion of SecularismNikithaNo ratings yet

- History Project Film Review: Gandhi (Richard Attenborough)Document8 pagesHistory Project Film Review: Gandhi (Richard Attenborough)avik sadhuNo ratings yet

- Dilip Simeon - Gandhi - S Legacy (2010)Document21 pagesDilip Simeon - Gandhi - S Legacy (2010)shubham.rathoreNo ratings yet

- IJCRT2107745Document3 pagesIJCRT2107745kishoreNo ratings yet

- Revisiting 1947 Through Popular CinemaDocument9 pagesRevisiting 1947 Through Popular CinemaManahil Saeed100% (1)

- Draft of Movie Fire.Document12 pagesDraft of Movie Fire.RajnishNo ratings yet

- Hanlon 1: Prisoners of Conscience (Patwardhan 1978), Which Document The Bihar Movement, TheDocument24 pagesHanlon 1: Prisoners of Conscience (Patwardhan 1978), Which Document The Bihar Movement, TheChris Johan V. WarthonNo ratings yet

- Legacy of Mahatma GandhiDocument24 pagesLegacy of Mahatma GandhiVaishnav KumarNo ratings yet

- History's Role in Japanese Horror CinemaDocument16 pagesHistory's Role in Japanese Horror CinemaMiharuChan100% (1)

- The Case of The Missing Mahatma Hindi CinemaDocument28 pagesThe Case of The Missing Mahatma Hindi Cinemasurjit4123No ratings yet

- UntitledDocument4 pagesUntitledTarikNo ratings yet

- Gandhi, The Civilizational Crucible, and The Future of DissentDocument15 pagesGandhi, The Civilizational Crucible, and The Future of DissentEray ErgunNo ratings yet

- Godard and Gorin's Left Politics by Julia LesageDocument25 pagesGodard and Gorin's Left Politics by Julia LesagegrljadusNo ratings yet

- Kashmir Files A PropogandaDocument4 pagesKashmir Files A Propogandaashok_pandey_10No ratings yet

- Writing For Documentary Academic ScriptDocument12 pagesWriting For Documentary Academic ScriptNitin KumarNo ratings yet

- A Divided World: Hollywood Cinema and Emigre Directors in the Era of Roosevelt and Hitler, 1933-1948From EverandA Divided World: Hollywood Cinema and Emigre Directors in the Era of Roosevelt and Hitler, 1933-1948No ratings yet

- Viceroy's House - AnalysisDocument2 pagesViceroy's House - AnalysisAjith PeterNo ratings yet

- Gandhi: From His Humble Beginnings To His Ultimate TriumphDocument4 pagesGandhi: From His Humble Beginnings To His Ultimate TriumphTherese Angelie CamacheNo ratings yet

- Summachar Curiopedia Newsletter 26Document7 pagesSummachar Curiopedia Newsletter 26AKNo ratings yet

- The ServantDocument22 pagesThe ServantOscar CervNo ratings yet

- Birth of Anti-ColonialismDocument49 pagesBirth of Anti-ColonialismNewmedicalcentre Pondy100% (1)

- Films Division - A Repository of History of IndiaDocument5 pagesFilms Division - A Repository of History of IndiasayhaslaysNo ratings yet

- The Globalization of Bollywood...Document20 pagesThe Globalization of Bollywood...hk_scribdNo ratings yet

- The Roy-Lenin Debate On Colonial Policy: A New InterpretationDocument9 pagesThe Roy-Lenin Debate On Colonial Policy: A New InterpretationGabriel QuintanilhaNo ratings yet

- Consumer Behaviour-Impact of Western Cinema On Indian YouthDocument8 pagesConsumer Behaviour-Impact of Western Cinema On Indian YouthShahrukh Soheil Rahman100% (1)

- Lecture 5Document25 pagesLecture 5satyabashaNo ratings yet

- Lect12 Photodiode DetectorsDocument80 pagesLect12 Photodiode DetectorsVishal KumarNo ratings yet

- Lect1 General BackgroundDocument124 pagesLect1 General BackgroundUgonna OhiriNo ratings yet

- CS195-5: Introduction To Machine Learning: Greg ShakhnarovichDocument33 pagesCS195-5: Introduction To Machine Learning: Greg ShakhnarovichsatyabashaNo ratings yet

- Elementary Data Structures: Steven SkienaDocument25 pagesElementary Data Structures: Steven SkienasatyabashaNo ratings yet

- Linear Algebra For Computer Vision - Part 2: CMSC 828 DDocument23 pagesLinear Algebra For Computer Vision - Part 2: CMSC 828 DsatyabashaNo ratings yet

- 4 Lecture 4 (Notes: J. Pascaleff) : 4.1 Geometry of V VDocument5 pages4 Lecture 4 (Notes: J. Pascaleff) : 4.1 Geometry of V VsatyabashaNo ratings yet

- Lecture 4Document9 pagesLecture 4satyabashaNo ratings yet

- Lecture 3Document18 pagesLecture 3satyabashaNo ratings yet

- Lecture 4Document9 pagesLecture 4satyabashaNo ratings yet

- Topics To Be Covered: - Elements of Step-Growth Polymerization - Branching Network FormationDocument43 pagesTopics To Be Covered: - Elements of Step-Growth Polymerization - Branching Network FormationsatyabashaNo ratings yet

- Image Formation in Man and MachinesDocument45 pagesImage Formation in Man and MachinessatyabashaNo ratings yet

- Image Analysis: Pre-Processing of Affymetrix ArraysDocument14 pagesImage Analysis: Pre-Processing of Affymetrix ArrayssatyabashaNo ratings yet

- Lecture 3Document4 pagesLecture 3satyabashaNo ratings yet

- Brightness: and CDocument39 pagesBrightness: and CsatyabashaNo ratings yet

- Program Analysis: Steven SkienaDocument20 pagesProgram Analysis: Steven SkienasatyabashaNo ratings yet

- Lecture 2Document3 pagesLecture 2satyabashaNo ratings yet

- Asymptotic Notation: Steven SkienaDocument17 pagesAsymptotic Notation: Steven SkienasatyabashaNo ratings yet

- History British I 20 Wil S GoogDocument709 pagesHistory British I 20 Wil S GoogsatyabashaNo ratings yet

- Lecture 2Document15 pagesLecture 2satyabashaNo ratings yet

- A Christopher Hitchens Bookshelf-9Document2 pagesA Christopher Hitchens Bookshelf-9satyabashaNo ratings yet

- Genomic Signal Processing: Classification of Disease Subtype Based On Microarray DataDocument26 pagesGenomic Signal Processing: Classification of Disease Subtype Based On Microarray DatasatyabashaNo ratings yet

- Reading Gandhi (2012)Document333 pagesReading Gandhi (2012)SS QuizzersNo ratings yet

- The Lahore Resolution PDFDocument86 pagesThe Lahore Resolution PDFHyder Ahmadi100% (2)

- BesantDocument3 pagesBesantAbhishek ChaturvediNo ratings yet

- PG Time Table April 2017Document38 pagesPG Time Table April 2017Jp PradeepNo ratings yet

- ALLINONEDocument4 pagesALLINONEVeer SolankiNo ratings yet

- Mahābhārata in Hindu Tradition - Hinduism - Oxford BibliographiesDocument30 pagesMahābhārata in Hindu Tradition - Hinduism - Oxford BibliographiesMahendra DasaNo ratings yet

- Social SampleDocument59 pagesSocial SampleSunil Abdul SalamNo ratings yet

- Gandhi As A Leader 2-FinalDocument37 pagesGandhi As A Leader 2-FinalChandni Verma100% (2)

- Constitution of India As A Reflection of The Ideals of The Indian National MovementDocument3 pagesConstitution of India As A Reflection of The Ideals of The Indian National MovementYasi NabamNo ratings yet

- Module 17 For Week 17Document10 pagesModule 17 For Week 17Khianna Kaye PandoroNo ratings yet

- Employment News 15 To 21 PDFDocument32 pagesEmployment News 15 To 21 PDFfilmfilmfNo ratings yet

- Gandhis Vision of Ramarajya A Critique PDFDocument13 pagesGandhis Vision of Ramarajya A Critique PDFLekshmi NarayananNo ratings yet

- 543 2207 1 PBDocument3 pages543 2207 1 PBLari Sandor LyngdohNo ratings yet

- GandhiDocument20 pagesGandhiAnbel LijuNo ratings yet

- 3350 Assignmemt 3 MercyDocument9 pages3350 Assignmemt 3 MercyFrancis MbeweNo ratings yet

- The Sarvodaya Samaj and Beginning of Bhoodan MovementDocument6 pagesThe Sarvodaya Samaj and Beginning of Bhoodan MovementAnonymous CwJeBCAXpNo ratings yet

- Ehi 01Document6 pagesEhi 01Khual NaulakNo ratings yet

- Mahatma Gandhi BiographyDocument3 pagesMahatma Gandhi BiographyAlena JosephNo ratings yet

- Decolonization - EssayDocument5 pagesDecolonization - EssayPetruţa GroşanNo ratings yet

- Dismantling Sainthood: Ambedkar On Gandhi: Anand RanganathanDocument25 pagesDismantling Sainthood: Ambedkar On Gandhi: Anand RanganathanVipin DixitNo ratings yet

- Social PsychologyDocument15 pagesSocial PsychologyOshinNo ratings yet

- Hind Swaraj - M.K. GandhiDocument2 pagesHind Swaraj - M.K. GandhiDinesh DewasiNo ratings yet

- No Mere Slogans - On Isabel Wilkerson's "Caste - The Origins of Our Discontents" - Los Angeles Review of BooksDocument11 pagesNo Mere Slogans - On Isabel Wilkerson's "Caste - The Origins of Our Discontents" - Los Angeles Review of BooksShayok SenguptaNo ratings yet

- Topic GandhiDocument3 pagesTopic GandhiVANSHIKA AGARWALNo ratings yet

- Modern India History MCQDocument10 pagesModern India History MCQHarsh Khulbe100% (1)

- INDIGODocument3 pagesINDIGOGod is every whereNo ratings yet

- How To Write Summer Holiday Homework in SanskritDocument5 pagesHow To Write Summer Holiday Homework in Sanskritbcdanetif100% (1)

- Gandhi WorksheetDocument2 pagesGandhi WorksheetPaul RodríguezNo ratings yet

- Social Science EM MCQ's Savi VijethaDocument72 pagesSocial Science EM MCQ's Savi VijethaManju NathNo ratings yet