Professional Documents

Culture Documents

A Glass Half Full: by Mike Thomas Chicago Sun-Times September 16, 2001

A Glass Half Full: by Mike Thomas Chicago Sun-Times September 16, 2001

Uploaded by

mjthomOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

A Glass Half Full: by Mike Thomas Chicago Sun-Times September 16, 2001

A Glass Half Full: by Mike Thomas Chicago Sun-Times September 16, 2001

Uploaded by

mjthomCopyright:

Available Formats

A Glass half full

by Mike Thomas

Chicago Sun-Times

September 16, 2001

We tend to do a lot of stories about people who are in some kind of life where everything seems very

closed off and small and then suddenly something happens to them or through force of will they force

themselves into a life where suddenly things seem really big and open and interesting and exciting.

Ira Glass, describing "This American Life"

At present, Ira Glass life is indeed big and open and interesting and exciting. It has been for some time. Or

at least it seems that way to those of us who arent him. Not only does he get to tell stories for a living, not

only does he enjoy celebrity, limited though it is, without all the hassles (for the sake of comparison, hes

marginally more famous than Harry Knowles, tubby red-haired overlord of the rebel movie review Web

site aintitcoolnews.com), but last November media watchdog monthly Brills Content placed him on its

annual Top 50 list of Media Players. Big whup, you say? Well, youre probably right, especially in light of

Glass latest journalistic dubbing. In early July, none other than Time magazine, grandpappy of prestigious

glossies, named him Americas Best Radio Host. Chicago-born playwright David Mamet penned the essay

praising Glass talents. As you might imagine, the boyish 42-year-old was understandably touched by this

latest honor, if not a bit perplexed. Possessed of little visible ego and a tendency toward self-deprecation,

he claims to be wholly undeserving of such heady recognition.

More on that later.

Steered by his famously unrelenting perfectionism and his prodigious talent for making even the most

mundane people, places and things buzz with profundity and worldliness, his weekly, hourlong program

"This American Life," which originates from local station WBEZ-FM (91.5), where it airs at 7 p.m.

Fridays, has grown since its inception in 1995 to become one of public radios most successful programs,

with a nationwide listenership of 1.2 million. Thats the latest statistic, anyway, straight from the man

himself. Hes got a thing for numbers.

***

Our piece today unfolds in three acts. In the first, we see young Ira, conservative Jewish son of a clinical

psychologist mother and an accountant father, flounder in an unremarkable nook of American suburbia,

where actually making a living doing something neat radio broadcasting, for instance was

unthinkable. Act Two examines his gradual, aimless, largely unsupervised rise through the ranks of public

radio, where he somehow forged a meaningful career that would eventually consume more than half his

life. In Act Three he reinvigorates not only public radio, but the entire medium, becomes an unlikely

kingmaker and finds a way to watch more television.

Act I: Aimless in Baltimore

Late 1960s, early 70s suburban Baltimore. The boy is 10, maybe 12, though extraordinarily perceptive

for his age. He glides effortlessly between disparate social groups. He has a knack for this sort of thing.

What he does is, he curbs his personality, gives them a partial view, lets them see only that part of him

theyll be comfortable seeing. And so they talk to him, open up to him. This skill will come in handy

someday. For now, though, hes just slogging through a white-bread existence, waiting for something,

anything, to happen.

Ive always had the sense that a lot of kids in the suburbs go, Well, there must be someplace thats a little

more interesting than this. I grew up in suburbs in no way distinguished by anything. And I didnt know

anybody who had a job in any sort of creative thing. Like, it was unthinkable that youd meet someone like

that.

And then he does. One day during his stifled adolescence he is listening to the radio. He hardly ever listens

to the radio. He thinks little of it as a mode of communication and certainly not as an avocation. But there is

this shock jock on AM 1300 WFBR named Johnny Walker, and his show, full of lowball humor and crude

gags, appeals to youthful sensibilities. Hey, thats not so hard, telling jokes, the boy concludes, whereupon

he sends Walker some of his best home-brewed gut-busters, whereupon Walker sends a limousine to fetch

the boy and bring him hither, to a house that radio built in some highfalutin part of town.

It seemed very glamourous, but it seemed very high-powered, what he was doing. Like, this impossibly

high-powered thing, the local morning drive-time disc jockey in Baltimore. I have to say, its still a job I

couldnt do.

Act II: Go West, Then East, Young Man

Years pass and the boy, now a young man, attends college at Northwestern, then at Brown, where he

majors in semiotics, the study of narrative and storytelling. In 1978, at age 19, he lands an internship at

National Public Radio in Washington D.C. Hapless and with vague sense of purpose, he has but one goal:

simple competence. Initially, he edits promos for All Things Considered and Morning Edition, becomes a

first-rate tape cutter. As for the rest of his skills...

All the other parts of radio, finding stories focusing a story, writing, reading on the air, interviewing I

was either really bad at or horrible at. And I spent years forcing myself through story after story after

story, going more slowly than anyone Ive ever met in radio. I would spend six or eight weeks on a five-

minute story. If you were to type out a five-minute story its like, two pages long. So thats the level were

talking about, and theres no way to make a living doing that.

These early years at NPR are partly spent under the tutelage of All Things Considered weekend editor Noah

Adams. Glass starts out doing promos for the show, the equivalent of working in the William Morris

mailroom. One promo in particular is especially horrible, so embarrassingly horrible that it never reaches

the airwaves. Today, Adams recalls nothing of this (perhaps it was either so bad that he has repressed it, or

not nearly as terrible as Glass contends), but he does have some other thoughts on his protgs early

genius:

During the year I was gone Ira was working with some of the hosts and he sort of conceptualized

something that I thought was brilliant. A lot of times you will interview a musician or a writer about their

work and they, for whatever reason, cant or are unable to be articulate about it or enthusiastic about it.

He just said, Well, why dont we just ask somebody about what theyre reading or what theyre listening

to? And all of a sudden these people who were a little bit stubborn to interview turned into very

enthusiastic people about somebody elses work. And it would reveal, every time they did a piece, far more

about the person being interviewed than the person being discussed.

***

Act Three: Almost Famous

It is June 1996. Much has transpired between then and now. After years of field reporting education

stuff, mostly of birthing stories at the speed of sludge, of briefly helming Talk of the Nation, of

producing segments for Morning Edition and All Things Considered, of hosting his own wacky show, The

Wild Room, he is finally proficient. Exceedingly proficient, in fact. It was touch and go there for a while,

but, dammit, he willed himself to learn this trade and now hes near the top of his game. Having moved to

Chicago about seven years prior to work at NPRs local bureau, he is now on the payroll of WBEZ, where

his gamble of a program, This American Life, is about to go national. Months ago, some paperwork was

filed and, like in a lottery dream, the Corporation for Public Broadcasting hurled $350,000 in his general

direction. In exchange for the dough, he has promised to stay put for three years and make this thing fly.

TAL wins a Peabody award right off the bat, establishes the show, and its host, as forces to be reckoned

with. Exceptional talents are continually showcased. The hardworking Glass, once professionally obscure

and meek, has unwittingly become a media star and kingmaker. Writer and humorist David Sedaris, whom

Glass discovered at Wrigleyvilles now-defunct Club Lower Links, and whose first Glass-produced public

radio essay, "The Santaland Diaries," garnered waves of raves following its broadcast on Morning Edition

in December 1992, recalls his meteoric, Glass-assisted rise to prominence:

He completely changed my life. Completely. Like in a story. Like, he should ride around in a pumpkin. He

really should. I suppose all your life, thats what you hope for, is to meet one single person who would,

without your asking, just sort of bestow this thing upon you and be so completely selfless and generous

about it. Everything, everything came from being on the radio. It was a before and after, like in a fairy tale.

It was overnight. The story was on the radio and the second it was over, the phone started ringing, and

ringing with offers. I had call waiting. It was just like in those old movies where people are plugging those

things into a switchboard. One moment, please, one moment, please. Can I put you on hold? I was

leaving that night to go to North Carolina for Christmas, and I just remember thinking, My life is

completely different now.

Years pass and Sedaris career blossoms, thanks in no small part to the wisdom and talent of Ira Glass. So

grateful is he that one day, during a reading in New York City, at which Glass has glowingly introduced

Sedaris to the crowd, the writer honors his maker by reciting a touching ode, penned just moments before.

His respect and love for the man who delivered him from a lifetime of house-cleaning and thrust him into

the national spotlight is palpable:

If he looked at himself in a brass pole

Irad see on his face a first-class mole

All hairy and horrid, it sits on his forehead

And closely resembles an a------

Sedaris, though, is but one standout from the Glass School of Broadcasting. There are many others, like the

whiny enchantress Sarah Vowell, whose oddly mesmerizing timbre and knack for narrative lands her an

early spot on Glass burgeoning program, which continues to build its listenership nationwide. Inspired

stories like Shooting Dad, a funny, lighthearted exploration of her gunsmith fathers lifelong fascination

with firearms, make her a public radio luminary. Glass, as ever, hovers in the shadows, allowing Vowells

unique personality to radiate. Heres Sarah:

Hes really let me just follow my heart in a way that not very many people would. When I wrote about

music, I never really understood the way musicians would talk about certain producers. Like, I love

everything Sam Phillips and Sun Studios did, but I never really quite understood what he could do for those

people and how he got the best work out of them. After working with Ira I started to understand that a little

better. He can extract the best possible you out of yourself, and its a pretty magical chemical process. I

dont know how he does it, but everybody should have one of those people. Whenever I get to the point in a

story where I say what the storys about, where Ive learned something or come to some revelation, I call

that part Dear Ira. Because I know thats the part thats really gonna light him up. When youre not just

telling some anecdote, when it actually means something, those are the moments Ira lives for.

***

Friday evening, mid-August 2001. It is 6:55 p.m., five minutes before showtime, and Glass clad sloppily

yet stylishly in a blue checked shirt, khakis and Chuck Taylor All-Stars bursts through the doors on his

way to the studio down the hall. There is a frantic air about him. He is, after all, the Best Radio Host in

America, and the pressure to perform is high. Not that it wasnt inordinately so already...

Um, sorry to get sidetracked here, but it seems like a logical place to bring this up again this Best Radio

Host in America thing. First of all, does it really mean anything? The short answer is, Yes, it is a great

honor. How could it not be? Its Time frigging magazine! (For the record, Glass never actually said it was a

great honor, and he definitely never used the word frigging he would have used the real thing to

express his feelings on the matter, but its a sure bet he is touched by all the hoopla.) The second and more

pressing question is: Why? Why does Glass deserve this accolade when there are many far more successful,

far more famous radio personalities who stalk the airwaves for three, four, five hours a day as opposed to

Glass measly one hour a week? Plus, TAL hardly ever features strippers, porn stars or freaks. What gives?

For the long answer, heres Glass himself:

I have to say, when this Time magazine thing came out naming me radio host of the year, like the main

thought I had was, Im not Americas best radio host. Like, Howard Stern is, clearly. Like, theres no

question. I think we do a very nice show, a really, really good show. But just as a straight-up radio host, I

feel like hes so far ahead of me. Its a beautifully formatted show, like the Jack Benny Show, where theres

a set of characters who you come to know. And then, over the course of five hours, he just creates one

situation after another for them to react to. This American Life is like a movie. There are characters and

you get involved with a conflict and you just stick around to find out what happens. Its a much different

approach to radio than what Howards doing, which is way more suited to being live.

I imagined that somebody at some time was going to show that Time thing to somebody on the Howard

Stern team and they would be like, Who is this guy? You ever heard of him? I could just imagine the

whole thing. And then theyd come and kick my ass.

Three minutes to curtain. Glass is tweeking equipment, queuing songs, checking sound levels. He smiles

and laughs, but the mirth seems less an expression of joy than a release of tension. He speaks quickly,

excitedly in ums and dudes and likes, verbal ticks that pepper his sentences, while conferring with

his staff and mumbling to himself. The program is going out live to Chicagoland and a central distribution

satellite, and Glass doesnt want to screw up. Everything must be precise. S---, Im a second off! he

exclaims when the test tone ends too soon and there is moment of dead air. Therell be hell to pay for

that. Later on, there is another faux pas, noticeable only to Glass and his radio posse. Its over. Dont

look back, he tells himself. No. Must. Look. Back.

New York-based producer Wendy Dorr sits next to him behind the consol, sweating the details without

actually sweating, and various other TAL staffers duck in and out. There are three pre-taped, meticulously

produced segments (edited digitally with a gorgeous new Macintosh G4 computer) that Glass will

introduce during the next hour. He rehearses lines semi-silently under his breath, making slight alterations

here and there, cracking himself up with barely audible asides and double entendres. Occasionally, he

announces, Stand by, the cue for his small studio audience, seated around the rooms perimeter, to shut

up while he does his thing.

The central theme of todays program is heat. Chicagos sweltering summer has spawned sweltering

stories. One of them, by first time TAL contributor Jonathan Goldstein, is particularly vivid and hilarious.

For a piece titled, Its Not the Heat, Its the Humility, Goldstein spent a few days in the Division Street

Russian Bathhouse, the only place he could find in Chicago that was hotter and more torpor-inducing than

the outdoors. Hunched in a corner, baseball cap turned backward, he listens intently as his droll, almost

monotone tale takes its maiden voyage over public airwaves. Heres a brief excerpt from Goldsteins stellar

performance, though the print version hardly does it justice:

Jakes younger son Willie calls me over. Hes giving a large hairy man a massage with an oak leaf brush

and wants me to see. Have you ever seen a real Russian-style massage? asks Willie, as the naked, 300-

pound man lying on his back that hes attending to obligingly raises his legs in the air like a baby about to

be diapered. Willie lifts the brush over his shoulder and brings it down between the mans legs, over and

over. He does this with a kind of casualness that suggests whipping a naked man in the privates is the most

normal thing in the world. And I watch them, completely and utterly freaked out. Which is, I think, the

result Willie was going for.

Toward the end of the broadcast, the mood in the studio grows noticeably looser. There is more laughing,

more smiling, none of it nervous. Ira and crew are preoccupied with the shows kicker, a tagline that will

somehow involve a nude Torey Malatia, WBEZs general manager and one of TALs earliest champions,

in a Russian bathhouse scenario. Minutes later another show is in the can. (Thats radio talk.) Glass looks

pleased, though not overly so. There were minor goofs throughout, and theyll be patched so the show is

virtually flawless when it is heard in the days ahead by 420 stations across the country.

Glass leans back in his chair, but he is not relaxed. It is eight oclock on a Friday night and most other

humans would seek respite sleep, drink, Russian-style massage after a week straight of 14-hour days.

But not him. Not yet. There is more to be done, and it must be done now. Then and only then will he allow

himself to kick back for a spell at one of his favorite vegetarian-friendly eateries, or maybe at home

sprawled before the idiot box, a device that for years just gathered dust, largely because all the good shows

were over by the time he got home. But now, thanks to the miracle of TIVO, with its magical ability to

automatically tape all of his favorites on a monstrous hard drive, hes able to view Buffy the Vampire

Slayer and The Sopranos and The West Wing at any time, day or night. He loves this newfound

freedom, the feeling of being completely divorced from any sort of rigid schedule, any pressure to cram yet

one more thing one more interview, one more editing session, one more anything into his already

jam-packed existence. Hes taking more time off, too, traveling once in a while, hanging out with his

girlfriend, exploring the city he has long called home. After years of laboring over other American lives, it

seems that Glass is finally making time to cultivate one of his own.

You might also like

- We Had a Little Real Estate Problem: The Unheralded Story of Native Americans & ComedyFrom EverandWe Had a Little Real Estate Problem: The Unheralded Story of Native Americans & ComedyRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (36)

- Sinister Urge: The Life and Times of Rob ZombieFrom EverandSinister Urge: The Life and Times of Rob ZombieRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (2)

- Stories I Only Tell My Friends: An AutobiographyFrom EverandStories I Only Tell My Friends: An AutobiographyRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (531)

- Last WordsDocument280 pagesLast Wordscomealot100% (1)

- Rod Serling: His Life, Work, and ImaginationFrom EverandRod Serling: His Life, Work, and ImaginationRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (2)

- American Doom Loop: Dispatches from a Troubled Nation, 1980s–2020sFrom EverandAmerican Doom Loop: Dispatches from a Troubled Nation, 1980s–2020sNo ratings yet

- Making Gay History: The Half-Century Fight for Lesbian and Gay Equal RightsFrom EverandMaking Gay History: The Half-Century Fight for Lesbian and Gay Equal RightsNo ratings yet

- July 16, 1951Document2 pagesJuly 16, 1951TheNationMagazineNo ratings yet

- Saturday Night Live: Equal Opportunity Offender: The Uncensored CensorFrom EverandSaturday Night Live: Equal Opportunity Offender: The Uncensored CensorNo ratings yet

- Gre - Usa - PHDDocument24 pagesGre - Usa - PHDrahmanNo ratings yet

- Stereo Types/How a Black Family and its Blond Homeboys Blended Their Hopes in 1950s PortlandFrom EverandStereo Types/How a Black Family and its Blond Homeboys Blended Their Hopes in 1950s PortlandNo ratings yet

- Only in New York: An Exploration of the World's Most Fascinating, Frustrating, and Irrepressible CityFrom EverandOnly in New York: An Exploration of the World's Most Fascinating, Frustrating, and Irrepressible CityRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (11)

- South Never Plays Itself, The: A Film Buff’s Journey Through the South on ScreenFrom EverandSouth Never Plays Itself, The: A Film Buff’s Journey Through the South on ScreenNo ratings yet

- The Road to Pickletown: A Southerner Confronts Cowbells, Clowns, Cuba, Christmas, and MississippiFrom EverandThe Road to Pickletown: A Southerner Confronts Cowbells, Clowns, Cuba, Christmas, and MississippiNo ratings yet

- Dynomite! - Good Times, Bad Times, Our Times - A MemoirDocument221 pagesDynomite! - Good Times, Bad Times, Our Times - A MemoirSir SuneNo ratings yet

- Twentieth Century Limited Book Two ~ Age of Reckoning: A NovelFrom EverandTwentieth Century Limited Book Two ~ Age of Reckoning: A NovelNo ratings yet

- Everywhere an Oink Oink: An Embittered, Dyspeptic, and Accurate Report of Forty Years in HollywoodFrom EverandEverywhere an Oink Oink: An Embittered, Dyspeptic, and Accurate Report of Forty Years in HollywoodRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (2)

- Citizen Kane RefPaperDocument4 pagesCitizen Kane RefPaperJan Crezul Balodong0% (1)

- Starstruck: When a Fan Gets Close to FameFrom EverandStarstruck: When a Fan Gets Close to FameRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (9)

- The Manhattan ProjectDocument4 pagesThe Manhattan ProjectDoniele DalorNo ratings yet

- Sunny Days: The Children's Television Revolution That Changed AmericaFrom EverandSunny Days: The Children's Television Revolution That Changed AmericaRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- 100 New Yorkers of The 1970s by Millard, MaxDocument192 pages100 New Yorkers of The 1970s by Millard, MaxGutenberg.org100% (1)

- Plots and Characters: A Screenwriter on ScreenwritingFrom EverandPlots and Characters: A Screenwriter on ScreenwritingRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (3)

- Wham Bam $$ Ba Da Boom!: Mob Wars, Porn Battles, and a View from the Trenches.From EverandWham Bam $$ Ba Da Boom!: Mob Wars, Porn Battles, and a View from the Trenches.No ratings yet

- Virtue Bombs: How Hollywood Got Woke and Lost Its SoulFrom EverandVirtue Bombs: How Hollywood Got Woke and Lost Its SoulRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- A Supremely Bad Idea: Three Mad Birders and Their Quest to See It AllFrom EverandA Supremely Bad Idea: Three Mad Birders and Their Quest to See It AllRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (97)

- Letters to Osama: Old and New Musings on Foreign and Domestic Terrorism...And Other MattersFrom EverandLetters to Osama: Old and New Musings on Foreign and Domestic Terrorism...And Other MattersNo ratings yet

- The Legend of Gasparilla and His Treasure: Matthew Connor Adventure Series, #3From EverandThe Legend of Gasparilla and His Treasure: Matthew Connor Adventure Series, #3No ratings yet

- Literary Criticism in To Kill A Mockingbird Tutorial 2Document32 pagesLiterary Criticism in To Kill A Mockingbird Tutorial 2Farah SaparuddinNo ratings yet

- Ford Super Duty f250 550 Booklet PDFDocument28 pagesFord Super Duty f250 550 Booklet PDFalejandro sanchezNo ratings yet

- Bmax Cpe Si e 2.3Document2 pagesBmax Cpe Si e 2.3José Emilio D' LeónNo ratings yet

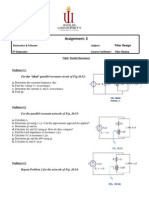

- Assignment 3Document4 pagesAssignment 3Saad Ahmed0% (1)

- Acoplador Vectronics HFT-1500Document13 pagesAcoplador Vectronics HFT-1500proftononNo ratings yet

- 14LK14 PDFDocument28 pages14LK14 PDFEmilio TamayoNo ratings yet

- Cable News Show Ranker: January 2019 (Adults 25-54)Document1 pageCable News Show Ranker: January 2019 (Adults 25-54)AdweekNo ratings yet

- National Spectrum Strategy by CITCDocument24 pagesNational Spectrum Strategy by CITCatif_aman123No ratings yet

- 5052300Document1 page5052300Johannita AlvaradoNo ratings yet

- BSA RosenDocument84 pagesBSA RosenrizkyNo ratings yet

- Radio Tower SpecDocument26 pagesRadio Tower SpecheikelNo ratings yet

- Common Stocks and Common Sense: The Strategies, Analyses, Decisions, and Emotions of A Particularly Successful Value Investor Iii WachenheimDocument43 pagesCommon Stocks and Common Sense: The Strategies, Analyses, Decisions, and Emotions of A Particularly Successful Value Investor Iii Wachenheimnathaniel.dye447100% (10)

- Advertising & SalesmanshipDocument22 pagesAdvertising & SalesmanshipSailyajit Baruah100% (2)

- Tata SkyDocument12 pagesTata SkyAbhimanyu ArjunNo ratings yet

- IEE Proceedings - Microwaves Antennas and Propagation Volume 143 Issue 2 1996 [Doi 10.1049_ip-Map-19960260] Langley, J.D.S.; Hall, P.S.; Newham, P. -- Balanced Antipodal Vivaldi Antenna for Wide Bandwidth Phased ArraysDocument6 pagesIEE Proceedings - Microwaves Antennas and Propagation Volume 143 Issue 2 1996 [Doi 10.1049_ip-Map-19960260] Langley, J.D.S.; Hall, P.S.; Newham, P. -- Balanced Antipodal Vivaldi Antenna for Wide Bandwidth Phased Arraysnaji1365No ratings yet

- Safeguard Marketing PlanDocument TranscriptDocument9 pagesSafeguard Marketing PlanDocument TranscriptTrent JohnsonNo ratings yet

- FUCDocument28 pagesFUCΝίκος ΤσελέντηςNo ratings yet

- Iso 18000Document12 pagesIso 18000anispidy007No ratings yet

- Antenna Selection For Automotive EMC Emissions and Immunity ApplicationsDocument20 pagesAntenna Selection For Automotive EMC Emissions and Immunity Applicationsbhuvana_eeeNo ratings yet

- Leica Sr20: User ManualDocument32 pagesLeica Sr20: User ManualathalNo ratings yet

- Sharp 29mu70 Chassis C-BM D-BM SM PDFDocument28 pagesSharp 29mu70 Chassis C-BM D-BM SM PDFManuel Melara100% (1)

- Teralight ProfileDocument11 pagesTeralight ProfileUmer KhanNo ratings yet

- AC Question Bank-SkDocument5 pagesAC Question Bank-SkShreerama Samartha G BhattaNo ratings yet

- Channel List DigitalDocument3 pagesChannel List DigitalPICS Farhan50% (2)

- Sales Manager or Account Executives or Sales and Marketing RepreDocument2 pagesSales Manager or Account Executives or Sales and Marketing Repreapi-121361567No ratings yet

- R&s Topex VoibridgeDocument12 pagesR&s Topex Voibridgesss dddNo ratings yet

- Mc275mk5 BroDocument2 pagesMc275mk5 BrojamocasNo ratings yet

- Talon RT-8200 Data SheetDocument2 pagesTalon RT-8200 Data Sheetmaryus66No ratings yet

- RC 1978 04Document44 pagesRC 1978 04Jan PranNo ratings yet

- IP Mobile Backhaul Solution Training-PTNDocument40 pagesIP Mobile Backhaul Solution Training-PTNGossan Anicet100% (1)

![IEE Proceedings - Microwaves Antennas and Propagation Volume 143 Issue 2 1996 [Doi 10.1049_ip-Map-19960260] Langley, J.D.S.; Hall, P.S.; Newham, P. -- Balanced Antipodal Vivaldi Antenna for Wide Bandwidth Phased Arrays](https://imgv2-2-f.scribdassets.com/img/document/190509945/149x198/aa546ff734/1423132972?v=1)