Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Guinea Worm Ghana

Guinea Worm Ghana

Uploaded by

api-2602835560 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

64 views12 pagesOriginal Title

guinea worm ghana

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Download as docx, pdf, or txt

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

64 views12 pagesGuinea Worm Ghana

Guinea Worm Ghana

Uploaded by

api-260283556Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Download as docx, pdf, or txt

You are on page 1of 12

ASONGAFEH NDOBEGANG

SOWK 675 MODULE IV

GENDER AND DEVELOPMENT

CASE STUDY: GUINEA WORM

The case study under consideration for this class assignment is the Guinea worm

diseases. This study was presented by the Department for International Development with

regards to the efforts made in managing and eradicating Guinea worm in Ghana. The guinea

warm disease like many other ailments has been rampant in many countries in the African

continent with the most endemic being Sudan (73%), Nigeria (10%) and Ghana (10%) (Dittoh,

2010). It has been noted that Guinea worm is a disease of the poor and mostly affects people in

the rural and agricultural areas. Kelly et al (2013), hold that the disease is most common in

remote and disadvantaged communities with inadequate sources of drinking water, poor

health care and high rates of illiteracy. Guinea worm is a water born disease, transmitted when

people drink water that has been contaminated by copepods that have ingested guinea worn

larvae (Kelly et al, 2013). It has equally been established that the outbreak of the guinea worm

disease is seasonal. Guiguemde in 1985 noted that in the Sahelian Zone, transmission is usually

common in the rainy reason that is from May to August. Other research has found that contrary

to Guiguemdes finding, in some areas like Danfa in Ghana the disease is prevalent in the dry

season usually in the months of September to January (Belcher et al, 1975). However in some

areas the outbreak is in both seasons.

While guinea worm has been said to be seldom lethal, it has a devastating socio economic

impact on the individuals infected, their families and the communities at large. The pandemic

affects the productive and reproductive capacities of community members. The fact that the

guinea worm disease can incapacitate an individual for more than two months means that

during this time the patient is prevented from engaging in any productive or reproductive

activity. Researchers like de Rooy and Edungbola (1988) have attempted to measure the

economic impacts of guinea worm by multiplying the number of days of labour lost by the

mean value of production per day or by the wage rate. Based on a survey of 87 households,

they estimated that three rice growing states of Southern Nigeria accumulated an annual loss

of $20 million as a result of these infections. To better appreciate the impact of this disease on

communities like that of Sadia Mesuna in our case study it is critical to examine and understand

the gender roles, activities and responsibilities.

In this community like in many other rural and agricultural communities in Africa, women are

usually seen as home builders, child bearing, child caring, cooking, food and water collecting.

These duties were well illustrated by Jackson and Associates Ltd (2002), when they explained

that in Ghana women are responsible for household services; the care of children, responsible

for family health, provision of food and fuel for cooking in addition to many other domestic

chores. They equally noted that some women played crucial roles in productive activities, some

income generation, paid domestic labour, farming and food processing. These views were

equally supported by Kelly et al (2013), when they noted that women in sub-Saharan Africa

traditionally performed domestic duties relating to childcare, cooking and cleaning.

It is worth mentioning that the Guinea worm disease does not discriminate as anyone can be

infected, be it male or female. However, as a result of the clear distinction in gender roles and

relations one can say that men (male) and women (female) will experience and be impacted by

this infection differently. It is as a result of this that a gender based analysis is appropriate in

attempting to understand the impact of the guinea worm disease on communities, particularly

Sadias community in Ghana. The gender analysis tool I will be employing to analyze this case

study is the Capacities and Vulnerabilities Analysis Framework (VCA). This framework was

designed for use in humanitarian interventions and disaster preparedness. The guinea worm

pandemic in Ghana can be seen as a humanitarian situation warranting humanitarian

intervention thus making it a perfect fit. This tool was developed at Harvard University, after a

research project which examined 30 case studies of NGOs intervening in multiple disaster

situations around the world (Candida, Ines & Maitrayee, 1999). As mentioned earlier CVA was

developed to be used in emergency situations to meet immediate needs and build on peoples

strengths in an effort to achieve long-term social and economic development (Candida et al.

1999). CVA holds that peoples existing strength (capacities) and weaknesses (vulnerabilities)

determine their resilience or their ability to overcome and bounce back from crisis. As Candida

et al (1999) would put it, to determine the impact and the manner in which people respond to

crisis. VCA makes a very clear distinction between vulnerability and needs as used in other

disaster contexts. Needs in this case are not used to represent the practical and strategic

gender needs but the immediate requirements for recovery from crisis (Anderson and

Woodrow, 1989). While needs deal with short term interventions, addressing vulnerabilities are

more long term and are part of the development process. The framework makes three

distinctions between capacities and vulnerabilities under consideration namely physical or

material capacities and vulnerabilities, social or organizational capacities and vulnerabilities and

finally motivational and attitudinal capacities and vulnerabilities (Candida et al. 1999). These

are the categories I will use for my gender analysis.

The rationale behind this choice of framework is because CVA is a very simple and easy to

use tool particularly in the case were the goal is not only to meet the needs of the people or

community in question in the short term but to identify and address their vulnerabilities in the

long term as a development goal. Candida et al (1999) stressed the fact that though simple to

use it is not overly simplistic. Again, CVA can be adapted to take into consideration many other

forms of differences in addition to gender like class, age, race, ethnicity and caste. This gives the

tool a lot of flexibility in terms of its ability to analyze not just one but multiple social

differences and inequalities. Another advantage of being flexible is that this tool can be used at

any stage or level of the intervention. It can be used before, during and after a disaster, major

change or intervention (Candida et al., 1999). In addition to CVAs ability to question and

challenge the status quo in communities with regards to gender, its most significant fit to this

case study is its ability to identify and strengthen peoples capacities and at the same time

recognizing and eliminating their vulnerabilities.

As mentioned previously the guinea worm infection is none discriminatory so who

ever drinks contaminated water is infected irrespective of sex or gender. It has equally been

noted that the impact of this infection may be experienced differently depending on the

gender. I will look at the impact on gender as a whole but draw particular attention to cases

where I believe the experience would be different. I will like to start the analysis by looking at

the physical/ material capacities and vulnerabilities identified in the case study.

The first capacity identified relates to the activities of national and international

nongovernmental organizations working in the area. The Carter Centre is one of those

organizations which have embarked on a journey to eradicate the guinea worm disease in

Ghana and in many parts of the world. In 1986 the Carter Centre in collaboration with the

Centre for Disease Control (CDC), UNICEF and WHO created a movement to advocate and lobby

for more funding for the Global Dracunculiasis Eradication Campaign. This campaign was

supported by prominent African presidents like Amadou Toumani of Mali and General Yakubu

Gowon of Nigeria (Brieger et al, 1997). It should equally be noted that the Ghanaian

government has not been left out in this eradication effort. Through its Ghana National

Program the government has provided funding for this fight. Between 1995 and 2005 the

governments of Ghana and Carter Centre have provided $5 million and $9 million in assistance

respectively to the eradication program (CDC, 2006). These efforts are directed towards

building hospitals or health centers to treat infected patients like 6 year old Sadia Mesuna who

stayed at the treatment center for two months enduring excruciating treatment to remove the

worm. This way the patients could be provided with the care and medical attention needed.

Another capacity noticed in relation to this is the education and training of community people

on the prevention of the disease. People are educated and sensitized on the need to drink clean

water, maintain clean water sources, treat water before drinking and prevention of the worms

coming in contact with open water sources as they will eject thousands of larvae and thereby

sustain the cycle of the disease. It is common knowledge that in these parts of the country one

of the roles of the woman (female) is to provide water for drinking and house hold use as such

the Guinea Warm Eradication Program (GWEP) has trained women in community education to

sensitize and discourage people identified with emerging worms from entering water sources.

They are also charged with surveillance of water sources and reporting of cases of guinea worm

disease (Peries and Cairncross, 1997). According to Barry (2007), the eradication of guinea

worm was increasingly successful in Ghana because of the recruitment and empowerment of

more than 6,800 female Red Cross volunteers in the fight against the disease.

Furthermore these communities like the town of Savelugu in Northern Ghana are provided

with simple household filters, individual cloth and pipe filters. Water development projects like

the abate application, borehole constructions and extension of pipe-born water were carried

out. As mentioned in the case study the Department for International Development (DFID) has

not only provided the Carter Centre with funding for its projects for guinea worm eradication in

Ghana but also funds water and sanitation programs in Ghana and Africa at large. The use of

these resources will definitely prevent community members from ingesting water

contaminated with guinea worm larvae and consequently the spread of waterborne diseases.

In as much as we have been able to identify some material and physical capacities it is

important to examine the numerous vulnerabilities available. The most significant vulnerability

experienced irrespective of gender is the level of poverty in these areas. It has been clearly

noted that guinea worm is a disease of the poor. This does not simply mean that it is prevalent

in poor communities but also that it continues and sustains the cycle of poverty. This view has

been reiterated by researchers like Dittoh (2010) who mentioned that while guinea worm

disease is a result of poverty it can also trap its victims in a vicious cycle of poverty and ill-

health. Levine (2007) noted that in as much as the guinea worm disease (GWD) was an

indicator of poverty, it likewise contributes to poverty. As mentioned previously GWD can

incapacitate its victim for up to two months or more. It is equally noted that this disease is

prevalent during the rainy seasons when farms are prepared for planting and when crops are

grown. Again this disease is prevalent with people age 15 to 49 years old (Smith et al, 1989).

The fact that most of the people infected are of working ages, means that they will not be able

to work in their farms in the case of men and women would not be able to take charge of their

traditional roles of providing for the families and working in their farms for those women who

are single mothers/single mother heads. As a result the disease has been termed disease of

the empty granary (Levine, 2007).

In addition to sustaining poverty, GWD causes disability. Though it has been view as a none

lethal disease, it does cause disabilities which could be temporary like inability to leave their

beds for up to a month, difficulty performing everyday activities as a result of the pain. Physical

disabilities have been said to be permanent is some cases where patients have had knocked

knees or other joints (Lyons, 1972). Some have equally noted that in some cases the disease has

resulted to mortality from tetanus and septicemia (Chippaux and Massougbodgi, 1991). These

disabilities temporary or permanent has serious impacts on the victims. For example in areas

were the girl child is not encouraged to go to school as a result of the lack of resources or due

to cultural belief: a girl child who is temporary or permanently disabled may lose her chance of

ever going to school. This is evident in the case study were Sadia was infected when she was six

years old was incapacitated for about 2 months, missed several months of school and

eventually dropped out. She was only able to go back to school when she was 10 year old, that

is 4 years after the infection and only thanks to the support of The Carter Centre and UK aid.

Again any permanent disability may considerably affect the social life of the victim even

determining whether or not they will be able to get married. This is very true for females

especially with the belief that a wife should be physically fit and able to take care of her family

and coupled with the tradition that only a man can marry, meaning only men and not women

can ask for someones hand in marriage. Therefore disability could mean no marriage for a

woman. The inability to marry also has deep traditional and social implications that may cause

stress, depression, isolation and sometimes rejection by society.

Another physical and material vulnerability worth mentioning is the lack of a vaccine or

medication to treat the disease. Also the lack of a more modern medical form of extracting the

worm from the human body has also proven to be a weakness. Therefore whoever is infected

by this disease will have to experience the long period of incapacity, the excruciating pain,

poverty and the risk of permanent disability if the worm breaks in the course of extraction and

sometimes death.

In addition to the material/physical capacities and vulnerabilities examined above, the

second category I would like to analyze using the Capacities and Vulnerabilities framework is

social and organizational capacity and vulnerability. To begin with social/organizational

capacity, I am of the opinion that community participation and community support is a crucial

strength of the people in this community. I will assume that like in many communities in local

and agricultural regions of Africa the inhabitants of this community will help individuals who are

sick by working in their farms, harvesting crops, fetching water and preparing food for their

families. They will also support and encourage parents to send their children back to school as

was the case of Sadia were the Guinea worm staff, local officials and community members

encouraged her to return to school several years after her treatment. Again, community

support can be seen in the attempts made by community members in the prevention and

eradication of the disease. Dittoh (2010), in his study noted that communities appointed

volunteers with the responsibility to conduct house to house monitoring of existing and

suspected cases of guinea worm. He also noted that these volunteers were equally charged

with visiting the dams and water sources in the morning when women go to fetch water. He

also indicated that chiefs and elders served as vigilante and worked with the volunteers and

guinea worm eradication staff. In addition community members particularly women served as

educators on guinea worm prevention. This was made evident by Kelly et al (2013) who stated

that women have been trained in community education in order to discourage people from

coming in contact with water sources if infected with guinea worm. These authors also

indicated that women were tasked with protecting water sources, promoting women to help

develop and improve the quality of water sources for communities in need and encourage

women to pursue health related employment opportunities.

A social/organization vulnerability would be a womans inability to meet or play her traditional

role of production (home maker, child care, cooking, cleaning the home) and sometimes her

reproductive role. This handicap may prevent a single girl or woman from ever having a

husband because the men would conclude that her disability will inhibit her from performing

these duties. For a married woman it may create problems in her marriage because she now is

unable to effectively do the things society or her husband expects her to do. These matrimonial

difficulties may cause her to lose her home (separation) or cause the man to find support that is

another wife to help with her duties. These scenarios are very common in some regions of

Africa including Muyuka a small village in the southwest part of Cameroon where I was born

and raised. For men this incapacity may prevent them from playing their bread winner and

head of the family role. This could lead to a loss of social status, loss of respect and title.

The final category in the Capacities and Vulnerabilities framework is the

attitudinal/motivational vulnerabilities and capacities. Starting with attitudinal vulnerability I

think that community attitude towards the victims can change drastically. Instead of looking at

the disease as natural and the patient as a victim, communities believe that this disease is fully

preventable and see the patient as negligent, careless and as such may show very little or no

community support to patients. This would mean that in addition to being crippled by the

infection, patients may have to struggle with isolation which may result to depression and other

mental health concerns. Furthermore the fact that this disease has a dual capacity as an

indicator and a sustainer of poverty may cause some communities to think that poverty is a

part of them. This could be because they have perpetually lived in poverty considering that the

guinea worm disease has a long history that may have affected that community for several

generations. In this case the communities may not be interested in making any effort to

alleviate their poverty.

With regards to attitudinal capacities, I think that the education on the prevention and

importance of drinking clean water would certainly change peoples attitude towards water.

This would mean that communities would be more open to using the water filters and

boreholes instead of drinking water from streams and ponds. In the case study Sadia was noted

to say that she will only drink filtered water. This equally means that people would become

more accepting of the fact that the disease can be eradicated and as such would encourage one

another to use filters and not to come in contact with water sources when infected with guinea

worm disease.

Furthermore, even without any real evidence I would believe that guinea worm disease would

help break the traditional gender role in these communities. To the extent that a man would be

comfortable to do some of those activities traditionally entitled to women like fetching water,

collecting wood for the house, cooking and childcare when the mother is incapacitated by the

disease

Haven done a gender analysis of the case study using the Capacities and Vulnerabilities

framework, I will like to highlight some of the concerns I identified from the study and guinea

worm eradication project.

Firstly, the study revealed that treatment centers were created in the villages. The question is

how many of these centers were opened and in what parts of the village? Again how accessible

are these centers, how long do patients have to walk to reach these centers? Considering that

the disease does not have any symptoms would the patients be able to walk to these centers

when the disease begins to manifest? Again, what is the cost of treatment at the health center?

Are the patients able to pay for treatment considering that these victims are usually poor and

lack the resources for other basic needs? These are concerns which a social worker would be

expected to resolve if they were involved with the community. The research did not provide

any answers to these questions.

Secondly, are the filters provided actually used by these people? What is the cost of the filters if

they have to be bought, what is the cost of sustaining or maintaining these filters and boreholes

considering the level of poverty some community members live in. Some have argued that cloth

filters cannot be used in all situations and that filters slows down work progress especially on

farms (Dittoh, 2010).

Thirdly, are these people strictly following and respecting the recommendations for prevention

like staying away from water sources if infected with the disease? Considering that volunteers

and vigilantes have been created to monitor women as they go to carry water clearly indicates

that community members do not follow these recommendations hence they have to be forced

to.

More so does the provision of filters and boreholes prevent the women from associating and

sharing ideas as they would do when they walk as a group to go fetch water? Does this limit

their network or connections? Does this take away their only daily opportunity of being

themselves without the men imposing or intervening in their activities?

I will like to conclude by stating that even though the Capacities and Vulnerabilities Analysis

Framework has been identified as the most appropriate gender analysis framework for the

Guinea Worm Disease case study in Ghana, it is not without its limitation. According to Candida

et al (1999), it is possible to use the CVA framework and still exclude gender issues. In effect

you could use a CVA framework and create gender-blind analyses something I am hoping

analysis avoided. Finally, there is no explicit agenda for womens empowerment in this gender

analysis tool.

REFERENCES

Barry, M. (2007). The tail end of guinea worm global eradication without a drug or a vaccine.

E Engl J Med 356: 2561 2564.

Belcher, D. W., Wurapa, F.K., Ward, W. B. & Lourie, I. M. (1975). Guinea worm in southern

Ghana: Its epidemiology and Impact on agricultural productivity. Am J Trop Med Hyg 24:243-

249.

Brieger, W. R., Otusanya, S., Adeniyi, J. D., Tijani, J., & Banjoko, M. (1997). Eradicating guinea

worm without wells: Unrealized hopes of the water decade. Health Policy Plan; 12(4):354-62.

Candida, M., Ines, S., & Maitrayee, M. (1999). A guide to Gender Analysis Framework. Oxfam

GB 1999. ISBN O855984031.

Centre for Disease Control (CDC), (2006). Department of Health and Human Services. Guinea

worm wrap up. # 162.

www.cdc.gov/ncidod/dpd/parasites/guineaworm.

Chippaux, J. P., & Massougbodji, A. (1991). Evaluation Clinique et epidemiologique de la

dracunculose au Benin. Med. Trop.

De Rooy, C. & Edungbola, L. D. (1988). Guinea worm control as a major contributor to self-

sufficiency in rice production in Nigeria, UNICEF working document, United Nations Childrens

Fund, New York, N,Y.

Dittoh, V. N. (2010). Poverty and Disease: Effect of guinea worm disease on school attendance in

the Tolon-Kumbungu district of the northern region of Ghana.

Retrieved from

http://dspace.knust.edu.gh:8080/jspui/bitstream/123456789/4036/1/Poverty%20and%20Disea

se.pdf

Guiguemde, T. R. (1985). Climate characteristics of endemic zones and epidemiologic modalities

of drancunculosis in Africa. Bull. Soc. Pathol. Exot. 79:89-95.

Jackson, E. T. & Associates Ltd. (2002). District capacity building project (DISCAP). Gender

analysis and strategy. Canadian International Development Agency.

http://www.discap.org/Publications/Gender%20Analysis%20and%20Strategy.pdf

Kelly, C., Bolton, B., Hopkins, D. R., Ruiz-Tiben, E., Withers, P.C & Meagley, K. (2013).

Contributions of the Guinea Worm Disease Eradication Campaign toward Achievement of the

Millennium Development Goals. Neglected Tropical Diseases. Volume 7, Issue 5 May 2013.

Levine, R. (2007). What works working group case 11: reducing guinea worm in Asia and Sub-

Saharan Africa. In: Case studies in global health: millions saved. Sudbury (Massachusetts): Jones

& Bartlett Learning.

Lyons, G. R. L. (1972). The existence of dracunculus medinensis in Turkana, Kenya. Trans R. Soc.

Trop. Med Hyg 75: 680-681.

Peries, H & Cairncross, S. (1997). Global eradication of Guinea worm. Parasitol Today 13: 431

437.

Smith, G. S., Blum, D., Huttly, S.R.A., Okeke, N., Kirkwood, B. R. & Reachem, R. G. (1989).

Disability from dracunculiasis: Effect on mobility. Annals of Tropical Medicine Parasitol 83.

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5822)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1093)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (852)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (898)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (540)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (349)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (822)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (403)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Postoperative Nursing Care Plan For Cesarian Section Patient Case Pres-ORDocument6 pagesPostoperative Nursing Care Plan For Cesarian Section Patient Case Pres-ORMae Azores93% (99)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The POISONED NEEDLE - Suppressed Facts About Vaccination, by Eleanor McBean, 1957Document283 pagesThe POISONED NEEDLE - Suppressed Facts About Vaccination, by Eleanor McBean, 1957webtrekker UKNo ratings yet

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Icke Original: Flu Is Not The Biggest Danger - It's The VaccineDocument8 pagesIcke Original: Flu Is Not The Biggest Danger - It's The VaccinePaul Gallagher100% (2)

- Biosecurity 081919Document9 pagesBiosecurity 081919Katrina AdajarNo ratings yet

- Exam IDocument7 pagesExam IJoshMatthewsNo ratings yet

- Safety HazardsDocument6 pagesSafety HazardsIrfanNo ratings yet

- HealthReformInChina PDFDocument204 pagesHealthReformInChina PDFJason LiNo ratings yet

- International Journal of Trend in Scientific Research and Development (IJTSRD)Document7 pagesInternational Journal of Trend in Scientific Research and Development (IJTSRD)Editor IJTSRDNo ratings yet

- Ladies Doctor in MadhubaniDocument5 pagesLadies Doctor in MadhubaniShubh ParmarNo ratings yet

- Access To Childbirth CareDocument67 pagesAccess To Childbirth CareemeNo ratings yet

- Hope Roses Duncan AndradeDocument13 pagesHope Roses Duncan AndradeAndrea Alejandra Ortiz SoteloNo ratings yet

- Basic Safety ConceptsDocument8 pagesBasic Safety ConceptsJannine Joyce BergonioNo ratings yet

- 2019 NCC Npsgs FinalDocument1 page2019 NCC Npsgs FinalJaic Ealston D. TampusNo ratings yet

- Test IntegumentaryDocument2 pagesTest IntegumentaryRoshann_Larano_48No ratings yet

- RISK Factor AlzheimersDocument2 pagesRISK Factor AlzheimersMeynard AndresNo ratings yet

- Masks and Gatherings Order - 12-7-20 709796 7Document9 pagesMasks and Gatherings Order - 12-7-20 709796 7WXYZ-TV Channel 7 DetroitNo ratings yet

- Gena Family PlanningDocument14 pagesGena Family PlanningRuffa Jane Bangay RivasNo ratings yet

- Edited 25 Agt 21-KOPI TB - Pengobatan TB Sensitif Obat Dan TB Resisten ObatDocument100 pagesEdited 25 Agt 21-KOPI TB - Pengobatan TB Sensitif Obat Dan TB Resisten ObatAlvin Armando SantosoNo ratings yet

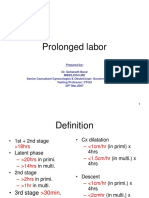

- Lecture-15 Prolonged LaborDocument8 pagesLecture-15 Prolonged LaborMadhu Sudhan PandeyaNo ratings yet

- Water, Sanitation and Hygiene (Wash) Programme: Iom in ActionDocument2 pagesWater, Sanitation and Hygiene (Wash) Programme: Iom in ActionAhmedNo ratings yet

- PVDocument58 pagesPVVikram MishraNo ratings yet

- Research Proposal Related To Coronavirus'Document15 pagesResearch Proposal Related To Coronavirus'Tasnim Lamya100% (1)

- Suplementary Feeding (C)Document19 pagesSuplementary Feeding (C)Dyiana Mhay JunioNo ratings yet

- E.-coli-Q & A From LehiDocument3 pagesE.-coli-Q & A From LehiLarryDCurtisNo ratings yet

- DepEd School Contingency Plan Manual For The Implementation of Limited Face To Face ClassesDocument27 pagesDepEd School Contingency Plan Manual For The Implementation of Limited Face To Face ClassesMMC BSEDNo ratings yet

- Food Handling Hygiene and Sanitation Practices in The Child-Car PDFDocument271 pagesFood Handling Hygiene and Sanitation Practices in The Child-Car PDFLance Giello DuzonNo ratings yet

- Nciph ERIC14Document5 pagesNciph ERIC14bejarhasanNo ratings yet

- Community Health Nursing Exam 2Document8 pagesCommunity Health Nursing Exam 2choobi100% (9)

- Detailed Lesson Plan in Mapeh 1Document6 pagesDetailed Lesson Plan in Mapeh 1jasmin diazNo ratings yet

- Nursing Perspectives On The Impacts of COVID 19.2Document5 pagesNursing Perspectives On The Impacts of COVID 19.2heba abd elazizNo ratings yet