Professional Documents

Culture Documents

The Summer of '70: K.U.'s Kent State

The Summer of '70: K.U.'s Kent State

Uploaded by

Paul FecteauCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- Tantamount: The Pursuit of the Freeway Phantom Serial KillerFrom EverandTantamount: The Pursuit of the Freeway Phantom Serial KillerRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (2)

- The Killing Season A Summer Ins - Miles CorwinDocument356 pagesThe Killing Season A Summer Ins - Miles CorwinFOXNo ratings yet

- Flesh Collectors: Cannibalism and Further Depravity on the Redneck RivieraFrom EverandFlesh Collectors: Cannibalism and Further Depravity on the Redneck RivieraRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (11)

- Kardashian Dynasty: The Controversial Rise of America's Royal FamilyFrom EverandKardashian Dynasty: The Controversial Rise of America's Royal FamilyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (7)

- Pub - The Killing Season A Summer Inside An Lapd HomicidDocument356 pagesPub - The Killing Season A Summer Inside An Lapd Homiciddragan kostovNo ratings yet

- The Mammoth Book of Killers at Large (Gnv64)Document599 pagesThe Mammoth Book of Killers at Large (Gnv64)melsjen100% (5)

- The Zebra Murders: A Season of Killing, Racial Madness and Civil RightsFrom EverandThe Zebra Murders: A Season of Killing, Racial Madness and Civil RightsNo ratings yet

- Historic Indianapolis Crimes: Murder & Mystery in the Circle CityFrom EverandHistoric Indianapolis Crimes: Murder & Mystery in the Circle CityRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- Rawhide Down: The Near Assassination of Ronald ReaganFrom EverandRawhide Down: The Near Assassination of Ronald ReaganRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (80)

- The Unsolved Mystery of The Notorious B.I.GDocument27 pagesThe Unsolved Mystery of The Notorious B.I.GDaniel MassarskyNo ratings yet

- Cold Case Kansas Column: The Murder of Roxanne ZwieslerDocument1 pageCold Case Kansas Column: The Murder of Roxanne ZwieslerPaul FecteauNo ratings yet

- Orange County Register September 1, 1985 The Night Stalker, Richard Ramirez, Caught in East Los Angeles - Page 1 of 5Document1 pageOrange County Register September 1, 1985 The Night Stalker, Richard Ramirez, Caught in East Los Angeles - Page 1 of 5Kathryn C. Geier100% (1)

- Case FactsDocument27 pagesCase FactsEmilie Easton67% (3)

- Day of Rage: Model Citizen Turns Cold-Blooded Killer in a Pennsylvania Small TownFrom EverandDay of Rage: Model Citizen Turns Cold-Blooded Killer in a Pennsylvania Small TownNo ratings yet

- The Professor & the Coed: Scandal & Murder at the Ohio State UniversityFrom EverandThe Professor & the Coed: Scandal & Murder at the Ohio State UniversityNo ratings yet

- You Never Know What a Guy Does at Night: You Never Know What A Guy Does At Night, #1From EverandYou Never Know What a Guy Does at Night: You Never Know What A Guy Does At Night, #1No ratings yet

- Gangsta ParadiseDocument15 pagesGangsta ParadisePolaris93No ratings yet

- Angel Maturino Resendiz - The Railroad KillerDocument11 pagesAngel Maturino Resendiz - The Railroad KillerMaria AthanasiadouNo ratings yet

- Chapter 5Document3 pagesChapter 5SILVIA CEPERONo ratings yet

- La Riots Thesis StatementDocument7 pagesLa Riots Thesis Statementfjm38xf3100% (2)

- New Face On Caltrain Board A Familiar One: Clear Battle LinesDocument32 pagesNew Face On Caltrain Board A Familiar One: Clear Battle LinesSan Mateo Daily JournalNo ratings yet

- Lone Wolf: Eric Rudolph: Murder, Myth, and the Pursuit of an American OutlawFrom EverandLone Wolf: Eric Rudolph: Murder, Myth, and the Pursuit of an American OutlawRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (9)

- Summary of Stephen G. Michaud & Hugh Aynesworth's The Only Living WitnessFrom EverandSummary of Stephen G. Michaud & Hugh Aynesworth's The Only Living WitnessNo ratings yet

- Bloodlines: The True Story of a Drug Cartel, the FBI, and the Battle for a Horse-Racing DynastyFrom EverandBloodlines: The True Story of a Drug Cartel, the FBI, and the Battle for a Horse-Racing DynastyRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (8)

- John Dillinger Slept Here: A Crooks' Tour of Crime and Corruption in St. Paul, 1920-1936From EverandJohn Dillinger Slept Here: A Crooks' Tour of Crime and Corruption in St. Paul, 1920-1936Rating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- InglésDocument2 pagesInglésFacundo EstévezNo ratings yet

- LariotsDocument5 pagesLariotsapi-329310859No ratings yet

- The Lost Sons of Omaha: Two Young Men in an American TragedyFrom EverandThe Lost Sons of Omaha: Two Young Men in an American TragedyRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (5)

- Richmond 1Document1 pageRichmond 1adoptie-margratenNo ratings yet

- Crime, Tragedy, and Catastrophe in Montgomery County, Maryland 1860 to 1960From EverandCrime, Tragedy, and Catastrophe in Montgomery County, Maryland 1860 to 1960No ratings yet

- Snap Judgment: A twisting thriller you won't be able to put downFrom EverandSnap Judgment: A twisting thriller you won't be able to put downNo ratings yet

- A Brotherhood Betrayed: The Man Behind the Rise and Fall of Murder, Inc.From EverandA Brotherhood Betrayed: The Man Behind the Rise and Fall of Murder, Inc.No ratings yet

- The Manchurian Journalist: Lawrence Wright, the CIA, and the Corruption of American JournalismFrom EverandThe Manchurian Journalist: Lawrence Wright, the CIA, and the Corruption of American JournalismNo ratings yet

- Serial Killers Part 2Document20 pagesSerial Killers Part 2api-275377906No ratings yet

- The Sordid Hypocrisy of to Protect and to Serve: Police Brutality, Corruption and Oppression in AmericaFrom EverandThe Sordid Hypocrisy of to Protect and to Serve: Police Brutality, Corruption and Oppression in AmericaNo ratings yet

- Serial Killers of the '80s: Stories Behind a Decadent Decade of DeathFrom EverandSerial Killers of the '80s: Stories Behind a Decadent Decade of DeathNo ratings yet

- Reform, Red Scare, and Ruin: Virginia Durr, Prophet of the New SouthFrom EverandReform, Red Scare, and Ruin: Virginia Durr, Prophet of the New SouthNo ratings yet

- Cold Case Kansas Special On JFK Assassination Researcher Shirley MartinDocument2 pagesCold Case Kansas Special On JFK Assassination Researcher Shirley MartinPaul FecteauNo ratings yet

- Cold Case Kansas Column On The Murder of Kelly Lynn AlbrightDocument2 pagesCold Case Kansas Column On The Murder of Kelly Lynn AlbrightPaul FecteauNo ratings yet

- Cold Case Kansas Column On The Murder of Dana WhislerDocument1 pageCold Case Kansas Column On The Murder of Dana WhislerPaul FecteauNo ratings yet

- 2006-08-31Document14 pages2006-08-31The University Daily KansanNo ratings yet

- Field Trip: Saturday, Febru-ARY 21: The Eastern Bluebird in Eastern KansasDocument8 pagesField Trip: Saturday, Febru-ARY 21: The Eastern Bluebird in Eastern KansasJayhawkNo ratings yet

- 2006-01-20Document15 pages2006-01-20The University Daily KansanNo ratings yet

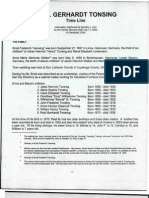

- 294 The Story of A Pioneer Pastor Paul Gerhardt Tonsing ADocument43 pages294 The Story of A Pioneer Pastor Paul Gerhardt Tonsing ARichard Tonsing100% (2)

- 2008-10-30Document16 pages2008-10-30The University Daily KansanNo ratings yet

- 2008-03-31Document19 pages2008-03-31The University Daily KansanNo ratings yet

- 2007-04-11Document24 pages2007-04-11The University Daily KansanNo ratings yet

- 2009-07-08Document31 pages2009-07-08The University Daily KansanNo ratings yet

- 2024 Kansas Relays Heat SheetsDocument21 pages2024 Kansas Relays Heat SheetsTony JonesNo ratings yet

- Counseling and Mental Health Resources-3Document2 pagesCounseling and Mental Health Resources-3api-284497736No ratings yet

- 2005-12-01Document31 pages2005-12-01The University Daily KansanNo ratings yet

- 2010-04-12Document20 pages2010-04-12The University Daily KansanNo ratings yet

- 2006-04-17Document14 pages2006-04-17The University Daily KansanNo ratings yet

- 2016 Psych Directory Lawrence KansasDocument4 pages2016 Psych Directory Lawrence Kansasapi-284497736No ratings yet

- Parish Profile - Trinity Episcopal Church in Lawrence, KansasDocument40 pagesParish Profile - Trinity Episcopal Church in Lawrence, Kansastrinitylawrence100% (1)

- 2010-02-17Document12 pages2010-02-17The University Daily KansanNo ratings yet

- 2007-07-11Document24 pages2007-07-11The University Daily KansanNo ratings yet

- 2007-03-15Document39 pages2007-03-15The University Daily KansanNo ratings yet

- Dictionary of American History 3rd Vol 07 PDFDocument581 pagesDictionary of American History 3rd Vol 07 PDFa100% (1)

- Lawrence, Kansas in Vintage PostcardsDocument92 pagesLawrence, Kansas in Vintage PostcardsDerek HansonNo ratings yet

- 2008-04-03Document24 pages2008-04-03The University Daily KansanNo ratings yet

- 2005-08-23Document10 pages2005-08-23The University Daily KansanNo ratings yet

- 2007-11-05Document13 pages2007-11-05The University Daily KansanNo ratings yet

- 2005-03-16Document28 pages2005-03-16The University Daily KansanNo ratings yet

- 2005-05-12Document18 pages2005-05-12The University Daily KansanNo ratings yet

- 2010-12-09Document12 pages2010-12-09The University Daily KansanNo ratings yet

- 2006-09-11Document17 pages2006-09-11The University Daily KansanNo ratings yet

- Dog Days Come Sail Away: Life. and How To Have OneDocument19 pagesDog Days Come Sail Away: Life. and How To Have OneThe University Daily KansanNo ratings yet

- 2007-07-02Document23 pages2007-07-02The University Daily KansanNo ratings yet

- Ashley Dunns ResumeDocument4 pagesAshley Dunns Resumeapi-341520131No ratings yet

The Summer of '70: K.U.'s Kent State

The Summer of '70: K.U.'s Kent State

Uploaded by

Paul FecteauCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

The Summer of '70: K.U.'s Kent State

The Summer of '70: K.U.'s Kent State

Uploaded by

Paul FecteauCopyright:

Available Formats

New Beginning

Your purchase through

KansasStateCars.com helps

create a brighter future for

your little Wildcat.

Visit our website for more

information and to shop

our huge inventory of new

and pre-owned vehicles.

(785) 565-5250 | info@kansasstatecars.com

COLDCASEKANSAS SPECI AL

The Summer of 1970

K.U.s Kent State PART ONE:

The Killing of Tiger Dowdell

B Y P A U L F E C T E A U

O

n the afternoon of July 20,

1970, University of Kansas

student Nick Rice made an

unplanned return to Lawrence.

He was spending the summer in his

hometown of Leawood but had stumbled

upon a forgotten parking ticket. It had to

be paid by the 21st.

The Lawrence that Rice drove into

may have appeared like a sleepy college

town with its students away on vacation,

but nothing could have been further from

the truth. Violence had erupted on its

streets, and one young man had lost his

life.

Though Rice was surely aware of

the discord, he also remained distant

from it. He had completed his freshman

year without involvement in any of

the skirmishes that had culminated in

what had already become a summer of

bloodshed. Rice had no way of knowing

that the battle was about to engulf him.

This Cold Case Kansas special

article tells of events that preceded July

20. The story of Nick Rice is the focus

of the second part of this series which

will appear in the next tmiWeekly . . . .

Tensions that had simmered

a decade beneath the surface of the

community burst into the open in 1970,

dominating the headlines of the Lawrence

Journal-World and papers throughout

the state. Many of the disturbances

ran along the fault line of race. The

University had taken steps to recognize

and respect black students, and one of

those involved the creation of a cultural

center dubbed Afro House located on

Rhode Island Street. Afro House would

have been controversial anyway, but it did

not help that some of the activists who

congregated there advocated violence.

Racists in Lawrence had their answer in

the form a group called The Minutemen

who armed themselves in anticipation of

confrontations with black revolutionaries.

Conict also focused on a

neighborhood at the base of Mt. Oread

between the Rock Chalk Caf and

the Gaslight Tavern. Its residents

became known as the Street People.

They rejected bourgeois values and

experimented with communal living

and drug use. Many of Lawrences

conservatives called the neighborhood

Hippie Haven and argued that the

spot attracted the worst kind of drifters

from around the country. Oread Street

had, in deed, gained a certain cach in

counterculture circles throughout the

nation, and few of the Street People

were K.U. students, but many were

Kansans.

As the spring semester unfolded,

blacks at Afro House and the denizens

of the Oread counterculture found

themselves increasingly at odds with the

Lawrence Police. Community leaders

urged the department to crack down in

the wake of disturbances that may or

may not have been the responsibility

of activists. On April 20, a re gutted

the Student Union, and arson was

suspected, prompting Governor Robert

Docking to place Lawrence under a dusk-

to-dawn curfew that lasted for three days.

The atmosphere became more toxic

in the wake of the Kent State shootings

on May 4 and those at Jackson State ten

days later. In response to rising tension,

University Chancellor E. Laurence

Chalmers suspended nals and allowed

students to instead attend workshops on

political discourse.

Perhaps the most detailed account of

the events of that troubled year exists in

Rusty Monhollons This is America? The

Sixties in Lawrence, Kansas (Palgrave,

2002). A Rossville native, Monhollon

graduated from Washburn and K.U.

and is now a history professor at Hood

College in Maryland.

One way to summarize all that took

place might be to note that, based upon

records of the Fire Marshall, Monhollon

estimates that 50 bombings and arsons

took place in Lawrence between April

and June.

In July, however, it appeared at rst

as though calm was making a comeback.

It was not to be. On July 16, the tension

between blacks and police claimed a

young mans life, and the powder keg

exploded.

James Preston Girard was awakened

at midnight by a phone call from the

news desk of The Topeka Daily Capital

where he worked as a reporter. Radio

trafc in Lawrence revealed that a cop

had been involved in a shooting. The

Lawrence Police Department kept their

communications notoriously cryptic, so

little more could be discerned without a

reporter tracking down the details. Girard

was in the early days of what would

become a storied career as a writer; he is

perhaps most known today for his 1993

crime novel The Late Man. He lived in

Lawrence in 1970 and was well aware of

the citys precarious peace. He set out

into the hot night, uncertain of what he

would nd.

At the police station, Girard learned

that Chief Richard Stanwix had gone

to a middle-of-the-night, high-level

meeting at the county courthouse. Girard

headed that way, but rst stopped at the

Safeway on 7th and New Hampshire to

check in with the news desk. He learned

that Lawrence Memorial Hospital had

received a gunshot victim named Rick

Dowdell. He was dead on arrival.

tmi WEEKLY FEBRUARY 5 - 18, 2009 10

"tt he|ps te be en a winning team."

0U1 0f :e |ACK50k BWt11

CU510MR5 C1 A 1AX RfUk0.*

That's because our team works

hard for you. we dlg deep,

asklng you all the rlght questlons

so you'll get every credlt and

deductlons you deserve.

-arvin "Magic" |ehnsen

tt he|ps te be en

CU

Th

ha

as

so

de

-

0ffer valld on tax preparatlon fees only. 0oes not apply to fnanclal

products or other servlces. Present coupon at tlme of tax preparatlon.

valld at partlclpatlng locatlons only and may not be comblned wlth

any other offer. FXPlkFS .1.o C0uP0h C00F: ,w

www.jacksenhewitt.cem

6ze.zzy.ee

0ff 0UR 1AX PRPARA1t0k

At |acksen Bewitt 1ax 5ervice

*See |acksonhewltt.com for rules and regulatlons.

Fifty bombings and arsons took place in Lawrence

between April and June.

COLDCASEKANSAS Special

Nineteen-year-old Rick Dowdell

stood six feet ve inches tall, was

nicknamed Tiger, and had become

a regular at Afro House. He had six

brothers. Their mother died when they

were young, and they were raised by

their grandmother. Rick Dowdell had

become politically involved at Lawrence

High School. At 16, he had addressed the

city council about police harassment of

blacks.

On J uly 16, shortly after 10 p.m.,

Dowdell asked K.U. student Franki

Lyn Cole if he could get a ride with

her to a friends house on Mt. Oread.

They left Afro House and got into her

Volkswagen.

Two Police cruisers were outside.

It had already been a violent night. A

man on the porch of Afro House had

been wounded by buckshot, and a

white woman several houses down had

been shot in the leg. Snipers had also

red upon the rst police car to respond.

The follow-up car, driven by Patrolman

William Garrett, pursued Coles V.W.

Accounts of the events remain

inconsistent, but what amounted to a

low-speed chase took place, ending

when Coles car stopped between New

Hampshire and Rhode Island Streets.

Dowdell ran down a dark alley, and

Garrett followed. Gun shots echoed.

Garrett reported that Dowdell had a

revolver in his left hand. Garrett ordered

him to drop it and red a warning shot.

Dowdell red at Garrett. Garrett red

three shots and continued to run down the

alley. He tripped over Dowdells body.

Dowdell had been hit in the back of the

head.

Garretts version of events did not

go unchallenged. Franki Lyn Cole said

Dowdell did not have a gun. Dowdells

family insisted that Tiger had been

right-handed. Others would question why

Garrett red into a setting so dark he later

fell upon the man he had hit.

After learning of Dowdells death,

Girard hurried to the courthouse at 11th

and Massachusetts. He walked down

the dimly lit brick alley to the back door

where he found Arden Booth, owner of

radio station KLWN, and Dolph Simons,

J r., publisher of The Journal-World,

waiting for city ofcials to emerge

from the meeting. Booth and Simmons

amounted to the heavy artillery of

Lawrence journalism, so Girard knew that

the city was facing a crisis.

Girard and Booth stood on the steps

inside a recessed doorway, speaking

in hushed tones about the killing of

Dowdell, while Simons paced in the

alley. Shots rang out, and Simons dove

to the ground behind the nearest car.

Girard realized that they were under re

from a gazebo in the park south of the

courthouse. The Undersheriff and two

deputies raced out the door, their guns

drawn. When they got to the gazebo, the

snipers had vanished.

Girard was back in the ofce the

next night, working the news desk. He

listened on the police scanner as ofcers

were dispatched to the eastside to

investigate groups of armed men moving

through the darkness. One of the cops,

Lt. Eugene Skinny Williams, was

ambushed and shot in the leg. Girard

listened as car after car responded, only

to come under re. For perilous minutes,

Williams was pinned down, and no one

could come to his aid. Finally, enough

police cruisers arrived to be used as a

shield, so an ambulance could bring aid to

Williams.

Another journalist, one of national

prominence, also happened to witness

rst hand the days of strife surrounding

the killing of Rick Dowdell. Bill

Moyers, press secretary in the J ohnson

administration, was traveling the nation at

work on Listening to America: A Traveler

Rediscovers His Country (Harper &

Row, 1971) when Simons invited him

to Lawrence. He arrived a week before

Dowdells shooting and interviewed

numerous individuals on all sides of the

conict.

On the day following the killing,

Moyers drove to Afro House. The

buildings nearby had come under

repeated re, and someone had thrown a

Molotov Cocktail through the window of

the Laundromat next door. Moyers wrote,

I drove through the area. Smoke still

hovered around the laundry. . . . Half a

dozen young blacks stood in front of Afro

House watching with sullen expressions

each passing car. I stopped to get out but

they gestured deantly for me to keep

moving and I did.

Moyers did collect fond recollections

of Tiger Dowdell from J ohn Spearman,

the only black on the Lawrence school

board, and from Dick Raney, the owner

of Raneys drugstore where Dowdell had

once worked.

Moyers left Lawrence on J uly 19.

On the way to the airport, he spoke with

a K.U. professor who summed up the

climate in Lawrence: Theres something

in the air that stings. You might call it

mutual paranoia.

That was the atmosphere Nick Rice

found himself in when he came to town

on J uly 20. A couple years later, Nicks

mother would write about her sons

fate. The manuscript she produced has

never been published, but it remains in

the archives at K.U.s Spencer Research

Library. The next issue of tmiWeekly will

include an article that draws heavily from

that document and continues this account

of Lawrences terrible summer of 1970.

tmi WEEKLY FEBRUARY 5 - 18, 2009 11

About the author:

Paul Fecteau serves as an Adjunct

Professor of Criminal Justice

at Washburn University. E-mail

comments or suggestions to him at

paul@coldcasekansas.com. p

Service Service Originality Originality

785-256-7300

785-256-7300

Financing

Available

Financing

Available

Style Style

www.staufferlawn.com

1150 Washington

Auburn, Kansas 66402

www.staufferlawn.com

1150 Washington

Auburn, Kansas 66402

Design - installation - Maintenance Design - installation - Maintenance

We are committed

to providing our customers

with quality. . .second to none!

We are committed

to providing our customers

with quality. . .second to none!

Stauffer Stauffer

Lawn & Landscape LLC Lawn & Landscape LLC

SPRING is just around

the corner!

Let us make your

lawn beautiful.

Call today!

SPRING is just around

the corner!

Let us make your

lawn beautiful.

Call today!

. .

Franki Lyn Cole said Dowdell did not have a gun.

Dowdells family insisted that Tiger had been right-

handed. Others would question why Garrett red into a

setting so dark he later fell upon the man he had hit.

Want to work for a renowned

global company? Grifols

Biomat USA, Inc., an

international pharmaceutical

company, seeking LPNs,

and Paramedic medical

professionals for plasma

collection facility. Must be a

high school graduate. Must

have excellent communication

skills & ability to use a PC.

BiomatUSA, Inc. offers

excellent compensation and

A full benefits package,

including 401K. Position

requires pre-employment

background check & drug

screen.

Send resume to Human

Resources, BiomatUSA, Inc.,

2120 SW 6th St., Topeka KS

66606. Fax to 785-233-9305,

or email to

topeka.biomatusa@grifols.com

Do You Like People?

New Beginning

Your purchase through

KansasStateCars.com helps

create a brighter future for

your little Wildcat.

Visit our website for more

information and to shop

our huge inventory of new

and pre-owned vehicles.

(785) 565-5250 | info@kansasstatecars.com

Tiger Dowdell had been dead

for almost four days when

Nick Rice entered the Gaslight

Tavern on Oread Avenue in the

Lawrence neighborhood that belonged

to the Street People. Dowdells

killing by a patrolman in a dark

alley downtown, as described in the

previous Cold Case Kansas column,

had brought the city to the brink of

chaos. Rices purpose in the bar

became clear: he ignored all the lively

conversation and strode directly to the

pinball machine.

Rice had come to the Gaslight on

July 20, 1970, to have a good time.

To him, that meant playing pinball

and talking to his girlfriend, Cecily

Stevens.

Rice surely knew of the rising

tension between the Street People, the

free spirits of the counterculture so

numerous in the neighborhood that it

seemed their own little community,

and the Lawrence Police. He was not,

however, politically involved.

That is not to say he was

dispassionate or self-centered. In

her memoir, Nicks mother, Esther

Christianson Rice, recalls how, in

April, he eschewed his own safety

to help ght the re in the Student

Union. His reward had been a citation

for curfew violation, though those

charges were eventually dropped.

Nick, a graduate of the Wentworth

Military Academy, opposed the

Vietnam War, but also expected to

ght in it.

Nick had completed his freshman

year as an engineering student at K.U.,

and a job at Baptist Memorial Hospital

brought Nick back to his hometown of

Leawood for the summer. He went to

Lawrence on July 20 only because he

wanted to pay a parking ticket before

it was due. He had to be at work at 6

a.m., and so before the evening grew

old, he was looking to leave.

He had promised a friend named

Jim a ride to K.C., but Jim could

not be found. Nick waited for him.

Outside, the fallout from the killing of

Dowdell continued.

The Lawrence Police Department

had responded several times that

night to reports of trash res and

open hydrants in the area between the

Gaslight Tavern and the Rock Chalk

Caf down the street. Ofcers arrived

on the scene at various times and

from different directions. No one of

high rank was among them, and their

efforts to coordinate were limited.

In his book on the 60s in

Lawrence, historian Rusty Monhollon

reports that those confronting the

police numbered about 60 with about

100 spectators lining Oread. At some

point, Nick went outside to see what

was going on and became one of those

bystanders.

The police were standing about

a block from the Rock Chalk when a

red Volkswagen became the focus of

the drama. Many sources report that

its owner, seeking insurance money,

offered it to a group seeking to protest

the loss of Dowdells life. They

turned the car over in the middle of

Oread Avenue. An unidentied man

with a rag and a lighter attempted to

set the car ablaze.

The police responded with

pepper gas, and the man ed. A

handful of patrolmen, some armed

with M-1 ries and some with

shotguns, advanced up Oread Avenue.

Numerous witnesses would report that

one of the ofcers shouted, Shoot the

motherfers! Shots rang out, and a

woman screamed.

Nick Rice had been felled by

the rst shot and lay on the sidewalk

bleeding from a wound in his head. A

graduate student named Merton Olds,

also a mere bystander, had been shot

in the leg.

Nicks friends rushed to his side.

Cecily held his hand, while Tim Cragg

and Allen Miller used towels from the

bar to try to stop the bleeding. Two

gas canisters landed nearby, hindering

efforts to aid Nick. A man named

Scotty Stewart approached police

and requested help, but a patrolman

knocked him to the ground.

Nicks friends eventually

managed to carry him through

the gas cloud and into the tavern.

Twenty minutes after the shooting,

an ambulance

nally arrived.

The driver found

that Nick had

stopped breathing

but had a pulse.

Efforts to revive

him failed, and

he was declared

dead on arrival

at Lawrence

Memorial Hospital

at 10:18 p.m. He

had been struck

by a bullet in the

back of his neck,

severing his spine

and shattering his

teeth.

With news

spreading that a

student had been

shot by police, the

city of Lawrence

was about to

become a war

zone. Governor

Robert Docking

sent in the

Highway Patrol

who actually had

jurisdiction on the K.U. campus where

the Lawrence police did not.

Topeka Daily Capital reporter

James Preston Girard had arrived on

Mount Oread just after the shooting

and in the days following was at

work on a feature story about one of

the most prominent Street People.

George Kimball had run for Sheriff of

Douglas County as a member of the

Yippie Party. Girard accompanied

Kimball to a secret meeting at the

Rock Chalk Caf and was surprised to

nd in attendance Colonel William L.

Albott of the Highway Patrol. Girard

was not the only one surprised.

When he arrived in Lawrence,

Albott had calmly entered the Rock

Chalk and the Gaslight and opened a

dialogue with the Street People. The

Lawrence Police had never attempted

such an approach.

tmi WEEKLY FEBRUARY 19 - MARCH 4, 2009 6

COLDCASEKANSAS SPECI AL

The Summer of 70:

KUs Kent State PART TWO:

The Killing of Nick Rice

B Y P A U L F E C T E A U

Nick Rices KU Student ID Photo.

University Archives, Spencer Research Library, University of

Kansas

Girard recalls the secret meeting

as very frank and even emotional.

In exchange for cooperation from

the Street People, Albott agreed to

personally patrol the area, keep away

the Lawrence police, and ignore drug

use. Albott would later report that at

rst, the street people called me pig,

but that stopped quickly, and they

started calling me Colonel.

Lawrence managed to make it

through the tense days ahead without

further bloodshed, and for that Albott

deserves a measure of the credit.

Girard regards Albott as one of the

few heroes of that tragic summer and

recalls hearing from a young ower

child that she felt safe when the man

in the Smokey-the-Bear hat was

around.

If the way forward for the city of

Lawrence turned out more favorable

than expected, the future for the

parents of Nick Rice was even more

nightmarish than could have been

imagined. Grieving for a child was

itself, obviously, a horrible process,

but one assumes that process takes

place amid the sympathy of friends

and the community. There would be

little sympathy for Esther Christianson

Rice and her husband Harry Dollar

Rice. They received hate mail and

threatening phone calls from crazies

on the right who proclaimed that Nick

got what he deserved. Even more

hurtful, though, was the silence of

their friends and peers.

Chris, as she was commonly

known, and Harry, who had served in

Pattons army, met as K.U. students

in 1947 and wed on campus in

Danforth Chapel in 1948. They were

conservative Republicans, proud

of their country and state. Many

conservatives and traditional Kansans,

however, felt that if the police shot

a man, that man must have done

something wrong. According to Chris,

the local news media did a poor job of

clarifying that Nick was not involved

in any of the destructive acts that had

taken place on Mount Oread. Some

family friends seemed to know but not

care that Nick had been an innocent

bystander--they simply told Chris and

Harry, My boy would never have

been there in the rst place.

The family also took little solace

from any of the investigations that

took place. A K.B.I. report released

August 19 found insufcient evidence

to establish that it had been the police

who had shot Nick. It did conrm

that Nick had done nothing more

rebellious that night than play pinball.

The report stated that his ngers

tested negative for traces of sulfur, his

clothes tested negative for traces of

gasoline, and his blood tested negative

for any illegal drugs or alcohol.

A few weeks later, the ofcial

inquest exonerated the police. It was

a maddening experience for Nicks

parents as they sat through hours

of testimony from the patrolmen

regarding the unknown individual

with the matches and rag who tried

to burn the V.W. The goal of this

material, it seemed to the Rices,

was to conate that rag with the

towel from the bar used to staunch

Nicks bleeding--that towel had

been photographed abandoned on

the sidewalk next to a pool of Nicks

blood. Under Kansas law at the time,

the police were allowed to use any

force to stop a eeing felon, so even

if the testimony did not aim to imply

Nick was confused with that felon, it

provided justication for the shooting

by indicating that the ofcers red for

a reason.

All the ofcers except one

testied that they had red upward in

warning. Oread Avenue rises toward

campus, so though they may have

been aiming high, they might still

have hit Nick. One patrolman stated,

however, that he had red on a level

line. Girard was there covering the

inquest and recalls the spectators

gasping at this ofcers admission.

Many of those at the inquest and

others in Lawrence think to this day

that it had to be this man who shot

Nick, but Girard regarded him as

probably just the most honest of the

cops who testied. Girard took all

of them at their word, though, when

they stated they had not intentionally

shot at Nick Rice. With all the

pepper gas oating around, Girard

surmises that the ofcer who actually

hit Nick never knew that he had done

so.

That fall, Nicks death became

a political issue. Dockings use of

the Highway Patrol in response to

the crisis did not sit well with hard-

line Attorney General Kent Frizzell

who challenged him for governor.

In her memoir, Chris recounts a

conversation she had with Frizellat

a Republican Party event prior to the

inquest. She approached the Attorney

General because she and her husband

were frustrated by rules barring them

from having their attorney play a role

in the proceedings. Frizzells response

was to question her about Nicks

arrest for curfew violation. When

Chris explained that, Frizzell said he

had heard that her son used to wear a

beard. At that point, Chris reports that

she lost faith in the Republican Party.

The voters eventually re-elected

Docking with a comfortable margin.

In 1971, frustrated by the

medias inaccurate reports, Chris

began writing about what happened

to Nick and ultimately produced a

short manuscript. Its title posed a

simple question: Who Killed Our

Son? The answer, despite the lack

of conclusiveness on the part of the

ofcial investigations, seemed simply

answered: a Lawrence Policeman

killed Nick. Chris, however, hopes

the question prompts readers to

ponder a broader context, for she

came to believe that the Lawrence

establishment by its unyielding stance

created the circumstances that cost her

son his life.

Despite their heartbreak, Chris

and Harry did not abandon Kansas.

Harry continued to reside in Leawood

until his death in 2004, and Chris still

resides there today in the same house

they lived in that horrible summer.

Who Killed Our Son? remains

unpublished but is available at K.U.s

Spencer Research Library.

Monhollon, who put years

of research into his book, This Is

America? The Sixties in Lawrence,

Kansas, doubts those of us who did

not live through the tragedy can

appreciate what an intense period in

Lawrence history it was. Two young

lives were lost and two families left

forever wounded, but Monhollon

notes, it was actually fortunate there

werent more casualties.

tmi WEEKLY FEBRUARY 19 - MARCH 4, 2009

7

About the author:

Paul Fecteau serves as

an Adjunct Professor of

Criminal Justice at Washburn

University. E-mail comments

or suggestions to him at paul@

coldcasekansas.com.

COLDCASEKANSAS SPECI AL

Earn $$$

Sell For Northeast Kansas Hottest New

Publication!

tmi Weekly is looking for salespeople to

work with advertising clients in Topeka and

Manhattan.

Outside Sales Experience Preferred.

Training is available. Salary includes a

generous commission package and is

negotiable based on experience.

For more information or to apply call or stop

by:

4100 SW Southgate Drive, 9a-5p

Call: (785) 267-6100

You might also like

- Tantamount: The Pursuit of the Freeway Phantom Serial KillerFrom EverandTantamount: The Pursuit of the Freeway Phantom Serial KillerRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (2)

- The Killing Season A Summer Ins - Miles CorwinDocument356 pagesThe Killing Season A Summer Ins - Miles CorwinFOXNo ratings yet

- Flesh Collectors: Cannibalism and Further Depravity on the Redneck RivieraFrom EverandFlesh Collectors: Cannibalism and Further Depravity on the Redneck RivieraRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (11)

- Kardashian Dynasty: The Controversial Rise of America's Royal FamilyFrom EverandKardashian Dynasty: The Controversial Rise of America's Royal FamilyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (7)

- Pub - The Killing Season A Summer Inside An Lapd HomicidDocument356 pagesPub - The Killing Season A Summer Inside An Lapd Homiciddragan kostovNo ratings yet

- The Mammoth Book of Killers at Large (Gnv64)Document599 pagesThe Mammoth Book of Killers at Large (Gnv64)melsjen100% (5)

- The Zebra Murders: A Season of Killing, Racial Madness and Civil RightsFrom EverandThe Zebra Murders: A Season of Killing, Racial Madness and Civil RightsNo ratings yet

- Historic Indianapolis Crimes: Murder & Mystery in the Circle CityFrom EverandHistoric Indianapolis Crimes: Murder & Mystery in the Circle CityRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- Rawhide Down: The Near Assassination of Ronald ReaganFrom EverandRawhide Down: The Near Assassination of Ronald ReaganRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (80)

- The Unsolved Mystery of The Notorious B.I.GDocument27 pagesThe Unsolved Mystery of The Notorious B.I.GDaniel MassarskyNo ratings yet

- Cold Case Kansas Column: The Murder of Roxanne ZwieslerDocument1 pageCold Case Kansas Column: The Murder of Roxanne ZwieslerPaul FecteauNo ratings yet

- Orange County Register September 1, 1985 The Night Stalker, Richard Ramirez, Caught in East Los Angeles - Page 1 of 5Document1 pageOrange County Register September 1, 1985 The Night Stalker, Richard Ramirez, Caught in East Los Angeles - Page 1 of 5Kathryn C. Geier100% (1)

- Case FactsDocument27 pagesCase FactsEmilie Easton67% (3)

- Day of Rage: Model Citizen Turns Cold-Blooded Killer in a Pennsylvania Small TownFrom EverandDay of Rage: Model Citizen Turns Cold-Blooded Killer in a Pennsylvania Small TownNo ratings yet

- The Professor & the Coed: Scandal & Murder at the Ohio State UniversityFrom EverandThe Professor & the Coed: Scandal & Murder at the Ohio State UniversityNo ratings yet

- You Never Know What a Guy Does at Night: You Never Know What A Guy Does At Night, #1From EverandYou Never Know What a Guy Does at Night: You Never Know What A Guy Does At Night, #1No ratings yet

- Gangsta ParadiseDocument15 pagesGangsta ParadisePolaris93No ratings yet

- Angel Maturino Resendiz - The Railroad KillerDocument11 pagesAngel Maturino Resendiz - The Railroad KillerMaria AthanasiadouNo ratings yet

- Chapter 5Document3 pagesChapter 5SILVIA CEPERONo ratings yet

- La Riots Thesis StatementDocument7 pagesLa Riots Thesis Statementfjm38xf3100% (2)

- New Face On Caltrain Board A Familiar One: Clear Battle LinesDocument32 pagesNew Face On Caltrain Board A Familiar One: Clear Battle LinesSan Mateo Daily JournalNo ratings yet

- Lone Wolf: Eric Rudolph: Murder, Myth, and the Pursuit of an American OutlawFrom EverandLone Wolf: Eric Rudolph: Murder, Myth, and the Pursuit of an American OutlawRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (9)

- Summary of Stephen G. Michaud & Hugh Aynesworth's The Only Living WitnessFrom EverandSummary of Stephen G. Michaud & Hugh Aynesworth's The Only Living WitnessNo ratings yet

- Bloodlines: The True Story of a Drug Cartel, the FBI, and the Battle for a Horse-Racing DynastyFrom EverandBloodlines: The True Story of a Drug Cartel, the FBI, and the Battle for a Horse-Racing DynastyRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (8)

- John Dillinger Slept Here: A Crooks' Tour of Crime and Corruption in St. Paul, 1920-1936From EverandJohn Dillinger Slept Here: A Crooks' Tour of Crime and Corruption in St. Paul, 1920-1936Rating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- InglésDocument2 pagesInglésFacundo EstévezNo ratings yet

- LariotsDocument5 pagesLariotsapi-329310859No ratings yet

- The Lost Sons of Omaha: Two Young Men in an American TragedyFrom EverandThe Lost Sons of Omaha: Two Young Men in an American TragedyRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (5)

- Richmond 1Document1 pageRichmond 1adoptie-margratenNo ratings yet

- Crime, Tragedy, and Catastrophe in Montgomery County, Maryland 1860 to 1960From EverandCrime, Tragedy, and Catastrophe in Montgomery County, Maryland 1860 to 1960No ratings yet

- Snap Judgment: A twisting thriller you won't be able to put downFrom EverandSnap Judgment: A twisting thriller you won't be able to put downNo ratings yet

- A Brotherhood Betrayed: The Man Behind the Rise and Fall of Murder, Inc.From EverandA Brotherhood Betrayed: The Man Behind the Rise and Fall of Murder, Inc.No ratings yet

- The Manchurian Journalist: Lawrence Wright, the CIA, and the Corruption of American JournalismFrom EverandThe Manchurian Journalist: Lawrence Wright, the CIA, and the Corruption of American JournalismNo ratings yet

- Serial Killers Part 2Document20 pagesSerial Killers Part 2api-275377906No ratings yet

- The Sordid Hypocrisy of to Protect and to Serve: Police Brutality, Corruption and Oppression in AmericaFrom EverandThe Sordid Hypocrisy of to Protect and to Serve: Police Brutality, Corruption and Oppression in AmericaNo ratings yet

- Serial Killers of the '80s: Stories Behind a Decadent Decade of DeathFrom EverandSerial Killers of the '80s: Stories Behind a Decadent Decade of DeathNo ratings yet

- Reform, Red Scare, and Ruin: Virginia Durr, Prophet of the New SouthFrom EverandReform, Red Scare, and Ruin: Virginia Durr, Prophet of the New SouthNo ratings yet

- Cold Case Kansas Special On JFK Assassination Researcher Shirley MartinDocument2 pagesCold Case Kansas Special On JFK Assassination Researcher Shirley MartinPaul FecteauNo ratings yet

- Cold Case Kansas Column On The Murder of Kelly Lynn AlbrightDocument2 pagesCold Case Kansas Column On The Murder of Kelly Lynn AlbrightPaul FecteauNo ratings yet

- Cold Case Kansas Column On The Murder of Dana WhislerDocument1 pageCold Case Kansas Column On The Murder of Dana WhislerPaul FecteauNo ratings yet

- 2006-08-31Document14 pages2006-08-31The University Daily KansanNo ratings yet

- Field Trip: Saturday, Febru-ARY 21: The Eastern Bluebird in Eastern KansasDocument8 pagesField Trip: Saturday, Febru-ARY 21: The Eastern Bluebird in Eastern KansasJayhawkNo ratings yet

- 2006-01-20Document15 pages2006-01-20The University Daily KansanNo ratings yet

- 294 The Story of A Pioneer Pastor Paul Gerhardt Tonsing ADocument43 pages294 The Story of A Pioneer Pastor Paul Gerhardt Tonsing ARichard Tonsing100% (2)

- 2008-10-30Document16 pages2008-10-30The University Daily KansanNo ratings yet

- 2008-03-31Document19 pages2008-03-31The University Daily KansanNo ratings yet

- 2007-04-11Document24 pages2007-04-11The University Daily KansanNo ratings yet

- 2009-07-08Document31 pages2009-07-08The University Daily KansanNo ratings yet

- 2024 Kansas Relays Heat SheetsDocument21 pages2024 Kansas Relays Heat SheetsTony JonesNo ratings yet

- Counseling and Mental Health Resources-3Document2 pagesCounseling and Mental Health Resources-3api-284497736No ratings yet

- 2005-12-01Document31 pages2005-12-01The University Daily KansanNo ratings yet

- 2010-04-12Document20 pages2010-04-12The University Daily KansanNo ratings yet

- 2006-04-17Document14 pages2006-04-17The University Daily KansanNo ratings yet

- 2016 Psych Directory Lawrence KansasDocument4 pages2016 Psych Directory Lawrence Kansasapi-284497736No ratings yet

- Parish Profile - Trinity Episcopal Church in Lawrence, KansasDocument40 pagesParish Profile - Trinity Episcopal Church in Lawrence, Kansastrinitylawrence100% (1)

- 2010-02-17Document12 pages2010-02-17The University Daily KansanNo ratings yet

- 2007-07-11Document24 pages2007-07-11The University Daily KansanNo ratings yet

- 2007-03-15Document39 pages2007-03-15The University Daily KansanNo ratings yet

- Dictionary of American History 3rd Vol 07 PDFDocument581 pagesDictionary of American History 3rd Vol 07 PDFa100% (1)

- Lawrence, Kansas in Vintage PostcardsDocument92 pagesLawrence, Kansas in Vintage PostcardsDerek HansonNo ratings yet

- 2008-04-03Document24 pages2008-04-03The University Daily KansanNo ratings yet

- 2005-08-23Document10 pages2005-08-23The University Daily KansanNo ratings yet

- 2007-11-05Document13 pages2007-11-05The University Daily KansanNo ratings yet

- 2005-03-16Document28 pages2005-03-16The University Daily KansanNo ratings yet

- 2005-05-12Document18 pages2005-05-12The University Daily KansanNo ratings yet

- 2010-12-09Document12 pages2010-12-09The University Daily KansanNo ratings yet

- 2006-09-11Document17 pages2006-09-11The University Daily KansanNo ratings yet

- Dog Days Come Sail Away: Life. and How To Have OneDocument19 pagesDog Days Come Sail Away: Life. and How To Have OneThe University Daily KansanNo ratings yet

- 2007-07-02Document23 pages2007-07-02The University Daily KansanNo ratings yet

- Ashley Dunns ResumeDocument4 pagesAshley Dunns Resumeapi-341520131No ratings yet