Professional Documents

Culture Documents

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

157 viewsTheories

Theories

Uploaded by

GenesaMarieChoiDifferent theories

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You might also like

- Theoretical FrameworkDocument5 pagesTheoretical FrameworkMa. Janelle Bendanillo100% (3)

- Pantaloons Final MRDocument40 pagesPantaloons Final MRVERGUNTSTAFFEN100% (5)

- Measuring Customer Satisfaction: Exploring Customer Satisfaction’s Relationship with Purchase BehaviorFrom EverandMeasuring Customer Satisfaction: Exploring Customer Satisfaction’s Relationship with Purchase BehaviorRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (6)

- Absolute Value: What Really Influences Customers in the Age of (Nearly) Perfect InformationFrom EverandAbsolute Value: What Really Influences Customers in the Age of (Nearly) Perfect InformationRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (15)

- Customersatisfaction TheoriesDocument14 pagesCustomersatisfaction TheoriesMutebi AndrewNo ratings yet

- New Edit Pro Honda SahibQQQDocument69 pagesNew Edit Pro Honda SahibQQQMuhammad IbrahimNo ratings yet

- 10 - Isac, Rusu 1Document7 pages10 - Isac, Rusu 1Rafel KurniaNo ratings yet

- According To Hasemark and AlbinssonDocument6 pagesAccording To Hasemark and AlbinssonAshwinKumarNo ratings yet

- Chpt4Customersatisfactiontheories PDFDocument38 pagesChpt4Customersatisfactiontheories PDFJenekNo ratings yet

- Theories For ResearchDocument6 pagesTheories For ResearchRissabelle CoscaNo ratings yet

- Customer Satisfaction TheoryDocument5 pagesCustomer Satisfaction Theorythar tharNo ratings yet

- Chpt4 ThConsumer Satisfaction Theories A Critical RevieweoriesDocument35 pagesChpt4 ThConsumer Satisfaction Theories A Critical RevieweoriesJithendar Reddy67% (3)

- Consumer Dissatisfaction: The Effect of Disconfirmed Expectancy On Perceived Product PerformanceDocument8 pagesConsumer Dissatisfaction: The Effect of Disconfirmed Expectancy On Perceived Product PerformanceMaria Goreti VongNo ratings yet

- Practical Research 1 - Group 1Document19 pagesPractical Research 1 - Group 1Mack Jigo DiazNo ratings yet

- The Effect of Service Performance and Ski Resort Image On Skiers SatisfactionDocument18 pagesThe Effect of Service Performance and Ski Resort Image On Skiers SatisfactionCornelia TarNo ratings yet

- Oliver, R. L. (2010)Document5 pagesOliver, R. L. (2010)19047Almira Ayu Vania AdyagariniNo ratings yet

- American Marketing AssociationDocument16 pagesAmerican Marketing AssociationmealletaNo ratings yet

- 26 A Study On Customer Satisfaction Towards Asian PaintsDocument77 pages26 A Study On Customer Satisfaction Towards Asian Paintsshubhank RaoNo ratings yet

- Customer Satisfaction Towards Services of VodafoneDocument106 pagesCustomer Satisfaction Towards Services of VodafoneChandan Srivastava100% (4)

- Research About: THE LEVEL OF SATISFACTION OF GRADE 12 BREAD AND PASTRY STUDENTS IN THE UNIVERSITY OF THE CORDILLERAS IN USING THE BAKING LABORATORYDocument28 pagesResearch About: THE LEVEL OF SATISFACTION OF GRADE 12 BREAD AND PASTRY STUDENTS IN THE UNIVERSITY OF THE CORDILLERAS IN USING THE BAKING LABORATORYStatio NeryNo ratings yet

- Yuksel (2001) The Expectancy Disconfirmation ParadigmDocument26 pagesYuksel (2001) The Expectancy Disconfirmation ParadigmMariana NunezNo ratings yet

- A Literature Review and Critique On Customer SatisfactionDocument6 pagesA Literature Review and Critique On Customer SatisfactionNguyễn VyNo ratings yet

- Service Quality, Customer Satisfaction, and Customer Value: A Holistic PerspectiveDocument16 pagesService Quality, Customer Satisfaction, and Customer Value: A Holistic PerspectiveMostaMostafaNo ratings yet

- A Literature Review and Critique On Customer SatisfactionDocument6 pagesA Literature Review and Critique On Customer SatisfactionTanima BhaumikNo ratings yet

- A Study On Customer Satisfaction Towards National Garage Raipur CGDocument74 pagesA Study On Customer Satisfaction Towards National Garage Raipur CGjassi7nishadNo ratings yet

- A Study On Customer Satisfaction Towards National Garage Raipur CGDocument74 pagesA Study On Customer Satisfaction Towards National Garage Raipur CGjassi7nishadNo ratings yet

- 2 FTPDocument28 pages2 FTPBhuvanesh KumarNo ratings yet

- The Service Recovery Paradox: True But Overrated?: Michels@T-Bird - EduDocument25 pagesThe Service Recovery Paradox: True But Overrated?: Michels@T-Bird - EduEn ZieNo ratings yet

- ChapterDocument14 pagesChapterVishnuNadarNo ratings yet

- A Comprehensive Model of Customer Satisfaction in Hospitality and Tourism: Strategic Implications For ManagementDocument12 pagesA Comprehensive Model of Customer Satisfaction in Hospitality and Tourism: Strategic Implications For ManagementDevikaNo ratings yet

- Service Gap Analysis and Kano Model in It Services of Cenveo SolutionsDocument18 pagesService Gap Analysis and Kano Model in It Services of Cenveo SolutionsbaluNo ratings yet

- Juli Lit ReviwDocument2 pagesJuli Lit ReviwjuliNo ratings yet

- Presentation OutlineDocument6 pagesPresentation OutlineMKWD NRWMNo ratings yet

- Prospect Theory and SERVQUAL: Management September 2014Document15 pagesProspect Theory and SERVQUAL: Management September 2014rina FitrianiNo ratings yet

- Customer Satisfaction (Often Abbreviated As Csat, More Correctly Csat) Is A TermDocument9 pagesCustomer Satisfaction (Often Abbreviated As Csat, More Correctly Csat) Is A TermMubeenNo ratings yet

- Distinguishing Service Quality and Customer Satisfaction: The Voice of The ConsumerDocument27 pagesDistinguishing Service Quality and Customer Satisfaction: The Voice of The ConsumerSoumya MukherjeeNo ratings yet

- Final ResearchDocument45 pagesFinal ResearchFrances Cleo TubadaNo ratings yet

- A - About Validity and ReliabilityDocument13 pagesA - About Validity and Reliabilitydikahmads100% (1)

- Customer Satisfaction: A Meta-Analysis of The Empirical EvidenceDocument20 pagesCustomer Satisfaction: A Meta-Analysis of The Empirical EvidenceXứ TrầnNo ratings yet

- Chapter 12 Measurement Scaling Reliability and Validity - ExtensionDocument19 pagesChapter 12 Measurement Scaling Reliability and Validity - Extensionsaad bin sadaqatNo ratings yet

- Chapter - 1Document74 pagesChapter - 1Harry HS100% (1)

- Factors Influencing Cargo Customer Satisfaction A Case Study of Kenya Airways Cargo Nick MBADocument40 pagesFactors Influencing Cargo Customer Satisfaction A Case Study of Kenya Airways Cargo Nick MBAFrank Munyua MwangiNo ratings yet

- Chapter 3 MLMDocument11 pagesChapter 3 MLMMatachi MagandaNo ratings yet

- Reliability and Validity in Marketing ResearchDocument11 pagesReliability and Validity in Marketing ResearchDr. Ashokan. CNo ratings yet

- Waiting Line Management: Unit IntroductionDocument37 pagesWaiting Line Management: Unit IntroductionAsora Yasmin snehaNo ratings yet

- Research Chapter 1 and Foreign Lit1Document6 pagesResearch Chapter 1 and Foreign Lit1Christian MartinNo ratings yet

- Final MainDocument36 pagesFinal MainGiga ByteNo ratings yet

- Effect of Customer SatisfactionDocument9 pagesEffect of Customer SatisfactionLongyapon Sheena StephanieNo ratings yet

- Relationships Among Service Quality, Customer Satisfaction and Customer Loyalty in Jordanian Restaurants SectorDocument5 pagesRelationships Among Service Quality, Customer Satisfaction and Customer Loyalty in Jordanian Restaurants Sectorranosh82No ratings yet

- Marketing: Customer Satisfaction Is A Term Frequently Used inDocument7 pagesMarketing: Customer Satisfaction Is A Term Frequently Used inLucky YadavNo ratings yet

- Quantitative Methods For Decision-Makers: Dr. Solange Charas October 25, 2021Document39 pagesQuantitative Methods For Decision-Makers: Dr. Solange Charas October 25, 2021Layla LiNo ratings yet

- American Marketing AssociationDocument8 pagesAmerican Marketing AssociationDiana YaguanaNo ratings yet

- Defining Customer SatisfactionDocument27 pagesDefining Customer SatisfactionTamil VaananNo ratings yet

- Measuring Customer Feedback Response and SatisfactDocument13 pagesMeasuring Customer Feedback Response and SatisfacttanandesyeNo ratings yet

- Chapter Eight Discussion Questions: ENGM 620 Fall 2010 Session Five Homework SolutionsDocument5 pagesChapter Eight Discussion Questions: ENGM 620 Fall 2010 Session Five Homework SolutionsIManNo ratings yet

- An Overview of Customer Satisfaction ModelsDocument12 pagesAn Overview of Customer Satisfaction ModelskutukankutuNo ratings yet

- Compatibility of Pharmaceutical Solutions and Contact Materials: Safety Assessments of Extractables and Leachables for Pharmaceutical ProductsFrom EverandCompatibility of Pharmaceutical Solutions and Contact Materials: Safety Assessments of Extractables and Leachables for Pharmaceutical ProductsNo ratings yet

- Textbook of Urgent Care Management: Chapter 11, Urgent Care AccreditationFrom EverandTextbook of Urgent Care Management: Chapter 11, Urgent Care AccreditationNo ratings yet

- Strategy Mapping: An Interventionist Examination of a Homebuilder's Performance Measurement and Incentive SystemsFrom EverandStrategy Mapping: An Interventionist Examination of a Homebuilder's Performance Measurement and Incentive SystemsNo ratings yet

- Newtech Advant Business Plan9 PDFDocument38 pagesNewtech Advant Business Plan9 PDFdanookyereNo ratings yet

- Basic Financial Econometrics PDFDocument167 pagesBasic Financial Econometrics PDFdanookyereNo ratings yet

- BoA CFE-CMStatistics 2017 PDFDocument272 pagesBoA CFE-CMStatistics 2017 PDFdanookyereNo ratings yet

- The Role of Communication in Contemporary MarketingDocument4 pagesThe Role of Communication in Contemporary MarketingdanookyereNo ratings yet

- Joshua 1:9: Bible Quotations For The Bible Reading MarathonDocument5 pagesJoshua 1:9: Bible Quotations For The Bible Reading MarathondanookyereNo ratings yet

- Consumer Buying DecisionsDocument2 pagesConsumer Buying DecisionsdanookyereNo ratings yet

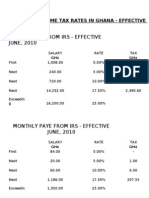

- Personal Income Tax Rates in GhanaDocument2 pagesPersonal Income Tax Rates in GhanadanookyereNo ratings yet

- Importance of A Trial BalanceDocument1 pageImportance of A Trial Balancedanookyere100% (3)

Theories

Theories

Uploaded by

GenesaMarieChoi0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

157 views34 pagesDifferent theories

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentDifferent theories

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Download as pdf or txt

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

157 views34 pagesTheories

Theories

Uploaded by

GenesaMarieChoiDifferent theories

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Download as pdf or txt

You are on page 1of 34

90

THEORIES OF CUSTOMER SATISFACTION

A number of theoretical approaches have been utilized to explain the

relationship between disconfirmation and satisfaction.

1

Many theories have been used to understand the process through which

customers form satisfaction judgments. The theories can be broadly classified under

three groups: Expectancy disconfirmation, Equity, and Attribution.

Still again there are a number

of theories surrounding the satisfaction and service paradigm.

2

The expectancy

disconfirmation theory suggests that consumers form satisfaction judgments by

evaluating actual product/service. Four psychological theories were identified by

Anderson that can be used to explain the impact of expectancy or satisfaction:

Assimilation, Contrast, Generalised Negativity, and Assimilation-Contrast.

3

1. MEASUREMENT OF SATISFACTION

Some of

the theories are discussed in this chapter.

The heart of the satisfaction process is the comparison of what was expected

with the product or services performance this process has traditionally been

described as the confirmation / disconfirmation process.

4

First, customers would

form expectations prior to purchasing a product or service. Second, consumption of

or experience with the product or service produces a level of perceived quality that is

influenced by expectations.

5

If perceived performance is only slightly less than expected performance,

assimilation will occur, perceived performance will be adjusted upward to equal

expectations. If perceived performance lags expectations substantially, contrast will

occur, and the shortfall in the perceived performance will be exaggerated.

6

91

Fig.4. 1. The Satisfaction Function

7

Fig.1 shows the satisfaction function between perceived quality and

expectations. Performance exceeds expectations, satisfaction increases, but at a

decreasing rate. As perceived performance falls short of expectations, the

disconfirmation is more.

Satisfaction can be determined by subjective (e.g. customer needs, emotions)

and objective factors (e.g. product and service features). Applying to the hospitality

industry, there have been numerous studies that examine attributes that travellers may

find important regarding customer satisfaction. Service quality and customer

satisfaction are distinct concepts, although they are closely related.

8

Atkinson (1988) found out that cleanliness, security, value for money and

courtesy of staff determine customer satisfaction.

9

Knutson (1988) revealed that

room cleanliness and comfort, convenience of location, prompt service, safety and

security, and friendliness of employees are important.

10

A study conducted by Akan

(1995) claimed that the vital factors are the behaviour of employees, cleanliness and

timeliness.

11

On the other hand the study by Choi and Chu (2001) concluded that staff

92

quality, room qualities, and value are the top three hotel factors that determine

travellers satisfaction.

12

2. VARIOUS THEORIES OF CUSTOMER SATISFACTION

Consistency theories suggest that when the expectations and the actual product

performance do not match the consumer will feel some degree of tension. In order to

relieve this tension the consumer will make adjustments either in expectations or in

the perceptions of the products actual performance. Four theoretical approaches have

been advanced under the umbrella of consistency theory: (1) Assimilation theory; (2)

Contrast theory; (3) Assimilation-Contrast theory; and (4) Negativity theory.

13

2.1. Assimilation Theory

Assimilation theory is based on Festingers (1957) dissonance theory.

Dissonance theory posits that consumers make some kind of cognitive comparison

between expectations about the product and the perceived product performance.

14

This view of the consumer post-usage evaluation was introduced into the satisfaction

literature in the form of assimilation theory.

15

According to Anderson (1973),

consumers seek to avoid dissonance by adjusting perceptions about a given product to

bring it more in line with expectations.

16

Consumers can also reduce the tension

resulting from a discrepancy between expectations and product performance either by

distorting expectations so that they coincide with perceived product performance or

by raising the level of satisfaction by minimizing the relative importance of the

disconfirmation experienced.

17

93

2.1.1. Assimilation Theory Criticism

Payton et al (2003) argues that Assimilation theory has a number of

shortcomings. First, the approach assumes that there is a relationship between

expectation and satisfaction but does not specify how disconfirmation of an

expectation leads to either satisfaction or dissatisfaction.

18

Second, the theory also

assumes that consumers are motivated enough to adjust either their expectations or

their perceptions about the performance of the product.

19

A number of researchers

have found that controlling for actual product performance can lead to a positive

relationship between expectation and satisfaction.

20

Therefore, it would appear that

dissatisfaction could never occur unless the evaluative processes were to begin with

negative consumer expectations.

21

2.2. Contrast Theory

Contrast theory was first introduced by Hovland, Harvey and Sherif (1987).

22

Dawes et al (1972) define contrast theory as the tendency to magnify the discrepancy

between ones own attitudes and the attitudes represented by opinion statements.

23

Contrast theory presents an alternative view of the consumer post-usage evaluation

process than was presented in assimilation theory in that post-usage evaluations lead

to results in opposite predictions for the effects of expectations on satisfaction.

24

While assimilation theory posits that consumers will seek to minimize the discrepancy

between expectation and performance, contrast theory holds that a surprise effect

occurs leading to the discrepancy being magnified or exaggerated.

25

According to the contrast theory, any discrepancy of experience from

expectations will be exaggerated in the direction of discrepancy. If the firm raises

expectations in his advertising, and then a customers experience is only slightly less

94

than that promised, the product/service would be rejected as totally un-satisfactory.

Conversely, under-promising in advertising and over-delivering will cause positive

disconfirmation also to be exaggerated.

26

2.2.1. Contrast Theory Criticism

Several studies in the marketing literature have offered some support for this

theory.

27

The contrast theory of customer satisfaction predicts customer reaction

instead of reducing dissonance; the consumer will magnify the difference between

expectation and the performance of the product/service.

28

2.3. Assimilation-Contrast Theory

Assimilation-contrast theory was introduced by Anderson (1973) in the

context of post-exposure product performance based on Sherif and Hovlands (1961)

discussion of assimilation and contrast effect.

29

Assimilation-contrast theory suggests that if performance is within a

customers latitude (range) of acceptance, even though it may fall short of

expectation, the discrepancy will be disregarded assimilation will operate and the

performance will be deemed as acceptable. If performance falls within the latitude of

rejection, contrast will prevail and the difference will be exaggerated, the

produce/service deemed unacceptable.

30

The assimilation-contrast theory has been proposed as yet another way to

explain the relationships among the variables in the disconfirmation model.

31

This

theory is a combination of both the assimilation and the contrast theories. This

paradigm posits that satisfaction is a function of the magnitude of the discrepancy

between expected and perceived performance. As with assimilation theory, the

95

consumers will tend to assimilate or adjust differences in perceptions about product

performance to bring it in line with prior expectations but only if the discrepancy is

relatively small.

32

Assimilation-contrast theory attempts illustrate that both the assimilation and

the contrast theory paradigms have applicability in the study of customer

satisfaction.

33

hypothesize variables other than the magnitude of the discrepancy

that might also influence whether the assimilation effect or the contrast effect would

be observed. when product performance is difficult to judge, expectations may

dominate and assimilation effects will be observed contrast effect would result in

high involvement circumstances. The strength of the expectations may also affect

whether assimilation or contrast effects are observed.

34

Fig .4.2. Assimilation-contrast theory

Source: Adapted from Anderson (1973, p.39)

35

96

Assimilation-Contrast theory suggests that if performance is within a

customers latitude (range) of acceptance, even though it may fall short of expectation

the discrepancy will be disregarded assimilation will operate and the performance

will be deemed as acceptable. If performance falls within the latitude of rejection (no

matter how close to expectation), contrast will prevail and the difference will be

exaggerated, the product deemed unacceptable.

36

2.3.1. Assimilation-Contrast Theory Criticism

Anderson (1973) argues that Cardozos (1965) attempt at reconciling the two

earlier theories was methodologically flawed.

37

The attempts by various researchers

to test this theory empirically have brought out mixed results. Olson and Dover

(1979) and Anderson (1973) found some evidence to support the assimilation theory

approach. In discussing both of these studies, however, Oliver (1980a) argues that

only measured expectations and assumed that there were perceptual differences

between disconfirmation or satisfaction.

38

2.4. Negativity Theory

This theory developed by Carlsmith and Aronson (1963) suggests that any

discrepancy of performance from expectations will disrupt the individual, producing

negative energy.

39

Negative theory has its foundations in the disconfirmation

process. Negative theory states that when expectations are strongly held, consumers

will respond negatively to any disconfirmation. Accordingly dissatisfaction will

occur if perceived performance is less than expectations or if perceived performance

exceeds expectations.

40

97

This theory developed by Carlsmith and Aronson (1963) suggests that any

discrepancy of performance from expectations will disrupt the individual, producing

negative energy. Affective feelings toward a product or service will be inversely

related to the magnitude of the discrepancy.

41

2.5. Disconfirmation Theory

Disconfirmation theory argues that satisfaction is related to the size and

direction of the disconfirmation experience that occurs as a result of comparing

service performance against expectations.

42

Szymanski and Henard found in the

meta-analysis that the disconfirmation paradigm is the best predictor of customer

satisfaction.

43

Ekinci et al (2004) cites Olivers updated definition on the

disconfirmation theory, which states Satisfaction is the guests fulfilment response.

It is a judgement that a product or service feature, or the product or service itself,

provided (or is providing) a pleasurable level of consumption-related fulfilment,

including levels of under- or over-fulfilment.

44

Fig.4.3. Disconfirmation Theory Model

98

Mattila, A & ONeill, J .W. (2003) discuss that Amongst the most popular

satisfaction theories is the disconfirmation theory, which argues that satisfaction is

related to the size and direction of the disconfirmation experience that occurs as a

result of comparing service performance against expectations. Basically, satisfaction

is the result of direct experiences with products or services, and it occurs by

comparing perceptions against a standard (e.g. expectations). Research also indicates

that how the service was delivered is more important than the outcome of the service

process, and dissatisfaction towards the service often simply occurs when guests

perceptions do not meet their expectations.

45

2.6. Cognitive Dissonance Theory

Cognitive dissonance is an uncomfortable feeling caused by holding two

contradictory ideas simultaneously. The theory of cognitive dissonance proposes that

people have a motivational drive to reduce dissonance by changing their attitudes,

beliefs, and behaviours, or by justifying or rationalizing them.

46

The phenomenon of cognitive dissonance, originally stated by Festinger in

1957, has been quickly adopted by consumer behaviour research. Described as a

psychologically uncomfortable state that arises from the existence of contradictory

(dissonant, non-fitting) relations among cognitive elements (Festinger 1957) cognitive

dissonance revealed high exploratory power in explaining the state of discomfort

buyers are often in after they made a purchase.

47

99

Fig.4.4. Cognitive Dissonance

Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:CognitiveDissonanceDiagram.jpg

2.6.1. Cognitive Dissonance Theory Criticism

Although cognitive dissonance is a well-established construct in consumer

behaviour research, applications are relatively scarce in current marketing research

projects. The reasons are: First, dissonance is often as merely a transitory

phenomenon. Second, problems of measurement as well as difficulties in

administering data collection often get in the way of empirically addressing cognitive

dissonance.

48

2.7. Adaptation-level Theory

Adaptation-level theory is another theory, which is consistent with expectation

and disconfirmation effects on satisfaction. This theory was originated by Helsen in

1964 and applied to customer satisfaction by Oliver. Helson (1964) simply put his

theory as follows:

100

it posits that one perceives stimuli only in relation to an adapted standard.

The standard is a function of perceptions of the stimulus itself, the context,

and psychological and physiological characteristics of the organism. Once

created, the adaptation level serves to sustain subsequent evaluations in that

positive and negative deviations will remain in the general vicinity of ones

original position. Only large impacts on the adaptation level will change the

final tone of the subjects evaluation.

49

2.7.1. Adaptation-level Theory - Criticism

This theory is gaining acceptance, as it is able to explain some counter-

intuitive predictions made by assimilation-contrast theories. (Oliver 1977)

Fig.4.5. Expectation and disconfirmation effects on satisfaction consistent

with adaptation-level theory.

Source: Oliver (1981, p.28)

50

2.8. Opponent-process Theory

This was originally a theory of motivation reformulated by Solomon and

Corbit, which has been adapted from the basic physiological phenomena known as

101

homeostasis.

51

The onset of the opponent process totally dependent on the effect of the

primary process, in which an emotional state is initiated by a known stimulus.(Oliver

1981). If the initial stimulus is eliminated to reduce completely or partially the

primary process effect, the opponent process will continue to operate at a decaying

rate determined by inertia factors.

Homeostasis assumes that many hedonic, affective or emotional

states, being away from neutrality and exceeding a threshold level of hedonic feelings,

are automatically opposed by central nervous system mechanisms, which reduce the

intensity of the feelings, both pleasant and aversive, to some constant level. (Solomon

and Corbin 1974)

52

Fig.4.6. Operation of Opponent-process phenomena as applied to customer

satisfaction and its determinants.

Source: Oliver (1981, p.31).

53

2.8.1. Opponent-process Theory Criticism

The opponent process is purely an internal drive, which causes

satisfaction/dissatisfaction to decay to a new or original level. Therefore, the degree

to which satisfaction is achieved depends upon the magnitude of disconfirmation as

well as upon the strength of the opponent process.

54

102

2.9. Equity Theory

This theory is built upon the argument that a mans rewards in exchange with

others should be proportional to his investments.

55

An early recognition of this

theory first came out of research by Stouffer and his colleagues in military

administration. They referred to relative deprivation (equity) as the reaction to an

imbalance or disparity between what an individual perceives to be the actuality and

what he believes should be the case, especially where his own situation is

concerned.

56

In other words, the equity concept suggests that the ratio of outcomes to inputs

should be constant across participants in an exchange. As applied to customer

satisfaction research, satisfaction is thought to exist when the customer believes that

his outcomes to input ratio is equal to that of the exchange person.

57

2.9.1. Equity Theory Criticism

In the handful of studies that have examined the effect of equity on customer

satisfaction, equity appears to have a moderate effect on customer satisfaction and

post-purchase communication behaviour.

58

2.10. Dissonance Theory

A decidedly different outcome is offered by applying Festingers Theory of

Cognitive dissonance. Applying Festingers ideas to affirmation and disconfirmation

of expectation in satisfaction work, one concludes that customers might try to

eliminate any dissonant experiences (situations in which they have committed to an

apparently inferior product or service).

59

103

Dissonance theory would predict that a customer experiencing lower

performance than expected, if psychologically invested in the product or service,

would mentally work to minimize the discrepancy. This may be done either by

lowering expectations (after the fact) or, in the case of subjective disconfirmation,

positively increasing the perception of performance.

60

2.11. Hypothesis Testing Theory

A two-step model for satisfaction generation was suggested by Deighton

(1983). First, Deighton hypothesizes, pre-purchase information (largely advertising)

plays a substantial role in creating expectations about the products customers will

acquire and use. Customers use their experience with product/service to test their

expectations. Second, Deighton believes, customers will tend to attempt to confirm

(rather than disconfirm) their expectations. Vavra, T.G. (1997) argues that this theory

suggests customers are biased to positively confirm their product/service experiences,

which is an admittedly optimistic view of customers, but it makes the management of

evidence an extremely important marketing tool.

61

2.12. Cue Utilization Theory

Cue utilization theory argues that products or services consist of several

arrays of cues that serves as surrogate indicators of product or service quality. There

are both intrinsic and extrinsic cues to help guests determine quality, where the

intrinsic cues provide information on the physical attributes of the product or service,

whereas extrinsic cues are product related to provide information such as brand and

price.

62

104

2.13. Stimulus-organism-response Theory

The concept behind this theory is that one of the basic frameworks that help

to understand how behaviour is impacted by the physical environment is the stimulus-

organism-response theory, which in a hospitality environment states that the physical

environment acts as a stimulus, gests are organisms that respond to stimulus, and the

behaviour directed towards the environment by guests is a direct response to the

stimulus.

63

2.14. Hypothesis Testing Theory

Deighton (1983) suggested a two-step model for satisfaction generation.

First, Deighton hypothesizes, pre-purchase information (largely advertising) plays a

substantial role in creating expectations about the products customers will acquire and

use. Customers use their experience with products / services to test their expectations.

Second, customers will tend to attempt to confirm (rather than disconfirm) their

expectations.

64

This theory suggests customers are biased to positivity confirm their

product/service experience.

105

Table 4.1 Comparison of Various Theories of Customer Satisfaction

65

Theory

Product/Service

Experience

Effect on

Perceived

Product

Service

Performance

Moderating

Conditions

Effect

Contrast Positive

confirmation

Negative

disconfirmation

Perceived

Performance

enhanced

Perceived

performance

lowered

Assimilation /

Contrast

Small

confirmation or

Disconfirmation

Large

confirmation or

Disconfirmation

Perceived

performance

assimilated

toward

expectations.

Perceived

performance

contrasted

against

expectations

Purchase is

ego-involved

Performance

difference

exaggerated

Dissonance Negative

disconfirmation

Perceived

performance

modified to

fit with

expectations

Purchase

made under

conditions of

ambiguity

Less

modification

Generalized

Negativity

Either

confirmation or

disconfirmation

Perceived

product

performance

lowered`

Purchase is

ego involved,

high

commitment

and interest

More

modification

Hypothesis

Testing

Either

confirmation or

disconfirmation

Perceived

performance

modified to

fit

expectations

Purchase

made under

conditions of

ambiguity

More

modification

106

3. MODELS OF CUSTOMER SATISFACTION MEASUREMENT

Organizations analyse customer satisfaction with various customer satisfaction

models. Different models clarify different theories of customer satisfaction.

3.1. SERVQUAL

The SERVQUAL instrument has been widely applied in a variety of service

industries, including tourism and hospitality. The instrument was used to measure

hotel employee quality as well.

66

Parasuraman, Zeithamal and Berry (1988) built a 22-item instrument called

SERVQUAL for measuring consumer perceptions of service quality. SERVQUAL

addresses many elements of service quality divided into the dimensions of tangibles,

reliability, responsiveness, assurance, and empathy.

67

A number of researchers have applied the SERVQUAL model to measure

service quality in the hospitality industry, with modified constructs to suit specific

hospitality situations.

68

The most widely accepted conceptualisation of the customer satisfaction

concept is the expectancy disconfirmation theory.

69

The theory was developed by

Oliver (1980), who proposed that satisfaction level is a result of the difference

between expected and perceived performance. Satisfaction (positive disconfirmation)

occurs when product or service is better than expected. On the other hand, a

performance worse than expected results with dissatisfaction (negative

disconfirmation).

70

Providing services those customers prefer is a starting point for providing

customer satisfaction A relatively easy way to determine what services customer

prefers is simply to ask them. Gilbert and Horsnell (1988) advocates that guest

107

comment cards (GCCs) are most commonly used for determining hotel guest

satisfaction. GCCs are usually distributed in hotel rooms, at the reception desk or in

some other visible place. However studies reveal that numerous hotel chains use

guest satisfaction evaluating methods based on inadequate practices to make

important and complex managerial decisions. In order to improve the validity of hotel

guest satisfaction measurement practice Barsky and Huxley (1992) proposed a new

sampling procedure that is Quality Sample. It reduces non-responsive bias by

offering incentives for completing the questionnaires. The components of their

questionnaire are based on disconfirmation paradigm and expectancy-value theory. In

this manner guests can indicate whether service was above or below their expectations

and whether they considered a particular service important or not.

71

Schall (2003)

discusses the issues of question clarity, scaling, validity, survey timing, question

order, and sample size.

72

According to the SERVQUAL model, service quality can be measured by

identifying the gaps between customers expectations of the service to be rendered

and their perceptions of the actual performance of service. SERVQUAL is based on

five dimensions of service:

1. Tangibility: Tangibility refers to the physical characteristics associated

with the service encounter.

73

2. Reliability: The service providers ability to provide accurate and

dependable services; consistently performing the service right.

The physical surroundings represented by

objects (for example, interior design) and subjects (for example, the

appearance of employees).

108

3. Responsiveness: A firms willingness to assist its customers by providing

fast and efficient service performances; the willingness that employees

exhibit to promptly and efficiently solve customer requests and problems.

4. Assurance: Diverse features that provide confidence to customers (such as

the firms specific service knowledge polite and trustworthy behaviour

from employees).

5. Empathy: The service firms readiness to provide each customer with

personal service.

74

Fig.4.7. Gap Model of Service Quality

Source: Zeithaml and Bitner (2003)

3.1.1. Criticism SERVQUAL

Though SERVQUAL has been generally robust as a measure of service

quality, the instrument has been criticised on conceptual and methodological

grounds.

75

The main criticism of SERVQUAL has focused on the use of expectation

as a comparison standard.

76

It has been argued that expectation is dynamic in nature,

109

and that it can therefore change according to customers experiences and consumption

situations.

77

One of the main problems mentioned in the literature is the applicability

of the five SERVQUAL dimensions to different service settings and replication

studies done by other investigators failed to support the five-dimensional factor

structure as was obtained by Parasuraman et a. in their development of

SERVQUAL.

78

3.2. Kano Model

The Kano model is a theory developed in the 80s by Professor Noriaki Kano

and his colleagues of Tokyo Rika University. The Kano et al (1996) model of

customer satisfaction classifies attributes based on how they are perceived by

customers and their effect on customer satisfaction.

79

The model is based on three

types of attributes viz. basic or expected attributes, (2) performance or spoken

attributes, and (3) surprise and delight attributes.

Fig.4.8. The Kano Model (Source: Kano, Seraku et al. 1996).

110

The performance or spoken attributes are the expressed expectations of the

customer. The basic or expected attributes are as the meaning implies the basic

attributes without any major significance of worth mentioning. The third one, the

surprise and delight attributes are those, which are beyond the customers

expectations.

Kano model measures satisfaction against customer perceptions of attribute

performance;

80

grades the customer requirements and determines the levels of

satisfaction.

81

The underlying assumption behind Kanos method is that the customer

satisfaction is not always proportional to how fully functional the product or service is

or in other words, higher quality does not necessarily lead to higher satisfaction for all

product attributes or services requirements. In his model, Kano (Kano, 1984)

distinguishes between three types of basic requirements, which influence customer

satisfaction. They are: (1) Must be requirements If these requirements are not

fulfilled, the customer will be extremely dissatisfied. On the other hand, as the

customer takes these requirements for granted, their fulfilment will not increase his

satisfaction; One-dimensional Requirement One dimensional requirements are

usually explicitly demanded by the customer the higher the level of fulfilment, the

higher the customers satisfaction and vice versa. (3) Attractive Requirement These

requirements are the product/service criteria which have the greatest influence on how

satisfied a customer will be with a given product.

82

The additional attributes, which

Kano mentions, are: Indifferent attributes, Questionable attributes, and Reverse

attributes.

111

3.3. ACSI Methodology

The American Customer Satisfaction Index (ACSI) was launched in 1994.

The American Customer Satisfaction Index uses customer interviews as input to a

multi-equation econometric model developed at the University of Michigans Ross

School of Business. The ACSI model is a cause-and-effect model (Fig-6) with

indices for drivers of satisfaction on the left side (customer expectations, perceived

quality, and perceived value), satisfaction (ACSI) in the centre, and outcomes of

satisfaction on the right side (customer complaints and customer loyalty, including

customer retention and price tolerance).

The ACSI was based on a model originally implemented in 1989 in Sweden

called the Swedish Customer Satisfaction Barometer (SCSB). The ACSI uses two

interrelated and complementary methods to measure and analyze customer

satisfaction: customer interviewing and econometric modelling.

83

Fig.4.9. ACSI Model (Source: ACSI Methodology, www.theacsi.org)

Vavra, T.G. (2007) views that the ACSI initiative has at least three primary

objectives:

1. Measurement: to quantify the quality of economic output based on

subjective consumer input;

112

2. Contribution: to provide a conceptual framework for understanding

how service and product quality relate to economic indicators

3. Forecasting: to provide an indicator of future economic variability by

measuring the intangible value of the buyer-seller relationship.

84

The ACSI survey process involves collecting data at the individual customer

level. Casual sequence begins with customer expectations and perceived quality

measures, as shown in the Fig.7, which are presumed to affect, in order, perceived

value and customer satisfaction. Customer satisfaction, as measured by the ACSI

index, has two antecedents: customer complaints, and ultimately, customer loyalty.

85

The ACSI is an economic indicator that measures the satisfaction of customers

across the U.S. Economy. The ACSI interviews about 80,000 Americans annually

and asks about their satisfaction with the goods and services they have consumed.

ACSI data is used by academic researchers, corporations and government agencies,

market analysts and investors, industry trade association, and consumers.

86

3.4. HOTELZOT (A modified version of SERVQUAL)

The conceptual model HOTELZOT measures the zone of tolerance in hotel

service by incorporating two levels of expectations desired and adequate. Desired

expectations represent the level of hotel service that a customer hopes to receive a

blend of what a customer believes can be and should be offered. This differs from

Parasuraman et als (1988) conceptualization, which referred only to what the service

should be. Adequate expectations represent a lower level of expectations. They

relate to what a hotel customer deems as acceptable level of performance. Desired

expectations are deemed to remain relatively stable over time, whereas adequate

performance expectations might vary with time.

87

The zone of tolerance can be

113

defined as the extent to which customers recognize and are willing to accept

heterogeneity.

88

Fig.4.10. Zone of Tolerance for Hotels (HOTELZOT)

Source: Halil Nadiri & Kashif Hussain (2005)

89

3.5. SERVPERF

The performance based service quality (SERVPERF) was identified by Cronin

and Taylor (1992). Cronin and Taylor proposed the SERVPERF instrument, which is

a more concise performance-based scale; an alternative to the SERVQUAL model.

90

The perceived quality model postulates that an individuals perception of the quality

is only a function of its performance. Cronin et al. (1994)

91

continue to debate

between the effectiveness of SERVQUAL and SERVPERF for assessing service

quality. The authors remained unconvinced of both, that including customer

expectations in measures of service quality is a position to be supported, and that

SERVPERF scale provides a useful tool for measuring overall service quality.

114

Moreover, Lee et al (2000)

92

empirically compare SERVQUAL (performance minus

expectations) with performance-only model (SERVPERF). The authors also conclude

that the results from the latter appeared to be superior to the former. It has been

acknowledged that such approach limits the explanatory power of service-quality

measurement.

93

115

REFERENCE

1

Oliver, R. (1980). Theoretical Bases of Consumer Satisfaction Research: Review,

critique, and future direction. In C. Lamb & P. Dunne (Eds), Theoretical

Developments in Marketing (pp.206-210). Chicago: American Marketing

Association.

2

Adee Athiyaman (2004). Antecedents and Consequences of Student Satisfaction

with University Services: A Longitudinal Analysis, Academy of Marketing

Studies Journal, J anuary.

3

Anderson, R.E. (1973). Consumer dissatisfaction: The effect of disconfirmed

expectancy on Perceived Product Performance, Journal of Marketing

Research, 10 February: 38-44.

4

Vavra, T.G. (1997). Improving your measurement of customer satisfaction: a guide

to creating, conducting, analysing, and reporting customer satisfaction

measurement programs, American Society for Qualit. p.42.

5

Oliver (1980) Theoretical Bases of Consumer Satisfaction Research: Review,

critique, and future direction. In C. Lamb & P. Dunne (Eds), Theoretical

Developments in Marketing (pp.206-210). Chicago: American Marketing

Association.

6

Vavra, T.G. (1997). Improving your measurement of customer satisfaction: a guide

to creating, conducting, analysing, and reporting customer satisfaction

measurement programs, American Society for Qualit. p.42.

7

Anderson, Eugene W., & Sullivan, Mary W. (1993). The Antecedents and

Consequences of Customer Satisfaction for Firms, Marketing Science,

Spring, p. 129.

8

Ivanka, A.H., Suzana, M., Sanja Raspor. Consumer Satisfaction Measurement in

Hotel Industry: Content Analysis Study. p.3.

9

Atkinson, A. (1988). Answering the eternal question: What does the Customer

Want? The Cornell Hotel and Restaurant Administration Quarterly, 29(2):

pp.12-14.

116

10

Knutson, B. (1988). Frequent Travellers: Making them Happy and Bringing them

Back. The Cornell Hotel and Restaurant Administration Quarterly. 29(1): pp.

83-87.

11

Akan, P. (1995). Dimensions of Service Quality: A Study in Istanbul. Managing

Service Quality. 5(6): pp. 39-43.

12

Choi, T.Y. & Chu, R. (2001). Determinants of Hotel Guests Satisfaction and

Repeat Patronage in the Hong Kong Hotel Industry. International Journal of

Hospitality Management. 20: pp. 277-297.

13

Peyton, R.M., Pitts, S., and Kamery, H.R. (2003). Consumer

Satisfaction/Dissatisfaction (CS/D): A Review of the Literature Prior to the

1990s, Proceedings of the Academy of Organizational Culture,

Communication and Conflict. Vol. 7(2).

14

Peyton, R.M., Pitts, S., and Kamery, H.R. (2003). Consumer

Satisfaction/Dissatisfaction (CS/D): A Review of the Literature Prior to the

1990s, Proceedings of the Academy of Organizational Culture,

Communication and Conflict. Vol. 7(2), p.42.

15

Anderson (1973), Consumer Dissatisfaction: The Effect of Disconfirmed

Expectancy on Perceived Product Performance. Journal of Marketing

Research: Vol.10 (2), pp.38-44

16

Peyton, R.M., Pitts, S., and Kamery, H.R. (2003). Consumer

Satisfaction/Dissatisfaction (CS/D): A Review of the Literature Prior to the

1990s, Proceedings of the Academy of Organizational Culture,

Communication and Conflict. Vol. 7(2).

17

Olson, J . & Dover, P. (1979), Disconfirmation of consumer expectations through

product trial. Journal of Applied Psychology: Vol.64, pp.179-189.

18

Peyton, R.M., Pitts, S., and Kamery, H.R. (2003). Consumer

Satisfaction/Dissatisfaction (CS/D): A Review of the Literature Prior to the

1990s, Proceedings of the Academy of Organizational Culture,

Communication and Conflict. Vol. 7(2). p.42.

117

19

Forman (1986), The impact of purchase decision confidence on the process of

consumer satisfaction/dissatisfaction. Unpublished Ph.D. Dissertation,

Knoxville: The University of Tennessee. Cited in Peyton, R.M., Pitts, S., and

Kamery, H.R. (2003). Consumer Satisfaction/Dissatisfaction (CS/D): A

Review of the Literature Prior to the 1990s, Proceedings of the Academy of

Organizational Culture, Communication and Conflict. Vol. 7(2).

20

Olson, J . & Dover, P. (1979), Disconfirmation of consumer expectations through

product trial. Journal of Applied Psychology: Vol.64, pp.179-189

21

Bitner (1987), Contextual Cues and Consumer Satisfaction: The role of physical

surroundings and employee behaviours in service settings. Unpublished

Doctoral Dissertation, University of Washington. Cited in Peyton, R.M., Pitts,

S., and Kamery, H.R. (2003). Consumer Satisfaction/Dissatisfaction (CS/D):

A Review of the Literature Prior to the 1990s, Proceedings of the Academy of

Organizational Culture, Communication and Conflict. Vol. 7(2). p.42.

22

Hovland, C., O. Harvey & M. Sherif (1957). Assimilation and contrast effects in

reaction to communication and attitude change. Journal of Abnormal and

Social Psychology, 55(7), 244-252.

23

Dawes, R., D. Singer & Lemons, P. (1972), An experimental Analysis of the

Contrast Effect and its Implications for Intergroup Communication and

Indirect Assessment of Attitude. Journal of Personality and Social

Psychology, 21(3), 281-295.

24

Cardozo, R. (1965). An experimental Study of Customer Effort, Expectation, and

Satisfaction, Journal of Marketing Research, 2(8), 244-249.

25

Reginald M. Peyton, Sarah Pitts, & Rob H. Kamery (2003), Consumer

Satisfaction/Dissatisfaction (CS/D): A Review of the Literature Prior to the

1990s, Allied Academies International Conference, Proceedings of the

Academy of Organizational Culture, Communications and Conflict: 7(2). p.

43.

26

Terry G. Vavra (1997). Improving Your Measurement of Customer Satisfaction: A

Guide to Creating, Conducting, Analyzing, and Reporting Customer

Satisfaction Measurement Programs. Americal Society for Qualit. pp. 44-60.

118

27

Oliver H.M. Yau & Hanming You (1994). Consumer Behaviour in China:

Customer Satisfaction and Cultural Values. Taylor & Francis, p.17.

28

Ibid.p.17.

29

Ibid.p.18.

30

Vavra, T.G. (1997). Improving your measurement of customer satisfaction: a guide

to creating, conducting, analysing, and reporting customer satisfaction

measurement programs, American Society for Qualit. p.45.

31

Hovland, C., O. Harvey & M. Sherif (1957). Assimilation and contrast effects in

reaction to communication and attitude change. Journal of Abnormal and

Social Psychology, 55(7), 244-252.

32

Reginald M. Peyton, Sarah Pitts, & Rob H. Kamery (2003), Consumer

Satisfaction/Dissatisfaction (CS/D): A Review of the Literature Prior to the

1990s, Allied Academies International Conference, Proceedings of the

Academy of Organizational Culture, Communications and Conflict: 7(2). p.

43.

33

Ibid. p.43.

34

Bitner, M (1987). Contextual Cues and Consumer Satisfaction: The Role of

Physical Surroundings and Employee Behaviours in Service Settings.

Unpublished Doctoral Dissertation, University of Washington.

35

Cited in Oliver H.M. Yau & Hanming You (1994). Consumer Behaviour in China:

Customer Satisfaction and Cultural Values. Taylor & Francis, p.18

36

Terry G. Vavra (1997). Improving Your Measurement of Customer Satisfaction: A

Guide to Creating, Conducting, Analyzing, and Reporting Customer

Satisfaction Measurement Programs. American Society for Qualit.

37

Anderson, R. (1973). Consumer Dissatisfaction: The Effect of Disconfirmed

Expectancy on Perceived Product Performance, Journal of Marketing

Research, 10(2), 38-44.

38

Reginald M. Peyton, Sarah Pitts, & Rob H. Kamery (2003), Consumer

Satisfaction/Dissatisfaction (CS/D): A Review of the Literature Prior to the

1990s, Allied Academies International Conference, Proceedings of the

119

Academy of Organizational Culture, Communications and Conflict: 7(2). p.

43.

39

Terry G. Vavra (1997). Improving Your Measurement of Customer Satisfaction: A

Guide to Creating, Conducting, Analyzing, and Reporting Customer

Satisfaction Measurement Programs. American Society for Qualit, p.47.

40

Carlsmith, J . & Aronson, E. (1963). Some Hedonic Consequences of the

Confirmation and Disconfirmation of Expectations, Journal of Abnormal and

Social Psychology, 66(2), pp.151-156.

41

Teery G. Vavra (1997). Improving your measurement of customer satisfaction: a

guide to creating, conducting, analyzing, and reporting customer satisfaction

measurement programs. American Society for Qualit. p.47.

42

Ekinci Y. & Sirakaya E. (2004). An Examination of the Antecedents and

Consequences of Customer Satisfaction. In: Crouch G.I., Perdue R.R.,

Timmermans H.J .P., & Uysal M. Consumer Psychology of Tourism,

Hospitality and Leisure. Cambridge, MA: CABI Publishing, pp. 189-202.

43

Petrick J .F. (2004). The Roles of Quality, Value, and Satisfaction in Predicting

Cruise Passengers Behavioral Intentions, Journal of Travel Research, 42 (4),

pp. 397-407, Sage Publications.

44

Ekinci Y. & Sirakaya E. (2004). An Examination of the Antecedents and

Consequences of Customer Satisfaction. In: Crouch G.I., Perdue R.R.,

Timmermans H.J .P., & Uysal M. Consumer Psychology of Tourism,

Hospitality and Leisure. Cambridge, MA: CABI Publishing, p.190.

45

Mattila A. & ONeill J .W. (2003). Relationships between Hotel Room Pricing,

Occupancy, and Guest Satisfaction: A Longitudinal Case of a Midscale Hotel

in the United States, Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research, 27 (3), pp.

328-341, Sage Publications.

46

Festinger, L. (1957). A Theory of Cognitive Dissonance. Stanford, CA: Stanford

University Press.

47

Thomas Salzberger & Monika Koller Cognitive Dissonance Reconsidering an

Important and Well-established Phenomenon in Consumer Research.

120

Extracted from http://pdfcast.org/pdf/cognitive-dissonance-reconsidering-an-

important-and-well-established-phenomenon-in-consumer-behaviour-research.

Last accessed on 23.06.2010.

48

Ibid.

49

Oliver H.M. Yau & Hanming You (1994). Consumer Behaviour in China:

Customer Satisfaction and Cultural Values. Taylor & Francis, p.19.

50

Cited in Oliver H.M. Yau & Hanming You (1994). Consumer Behaviour in China:

Customer Satisfaction and Cultural Values. Taylor & Francis, p.20.

51

Oliver H.M. Yau & Hanming You (1994). Consumer Behaviour in China:

Customer Satisfaction and Cultural Values. Taylor & Francis, p.20.

52

Ibid.p.20

53

Cited in Oliver H.M. Yau & Hanming You (1994). Consumer Behaviour in China:

Customer Satisfaction and Cultural Values. Taylor & Francis, p.20.

54

Ibid.p.20

55

Oliver, R.L. & J .E. Swan (1989a). Consumer Perceptions of Interpersonal Equity

and Satisfaction in Transactions: A Field Survey Approach. Journal of

Marketing, 53, (April), 21-35.

56

Oliver H.M. Yau & Hanming You (1994). Consumer Behaviour in China:

Customer Satisfaction and Cultural Values. Taylor & Francis, p.20.

57

Adee Athiyaman (2004). Antecedents and Consequences of Student Satisfaction

with University Services: A longitudinal analysis, Academy of Marketing

Studies Journal, J an.

58

Oliver, R.L. & J .E. Swan (1989b). Equity and disconfirmation perceptions as

influences on merchant and product satisfaction, Journal of Consumer

Research, 16 (December): 372-383.

59

Festinger, Leon (1957). A Theory of Cognitive dissonance. Stanford, CA: Stanford

University Press.

121

60

Terry G. Vavra (1997). Improving Your Measurement of Customer Satisfaction: A

Guide to Creating, Conducting, Analyzing, and Reporting Customer

Satisfaction Measurement Programs. American Society for Qualit. p.47.

61

Ibid.p.47.

62

Reimer A. & Kuehn R. (2005). The impact of servicescape on quality perception,

European J ournal of Marketing, 39 (7/8). 785-808, Emerald Group Publishing

Limited. [Online]. DOI: 10.1108/03090560510601761 (Accessed: 12.05.2010)

63

Mattila A. (1999). Consumers Value J udgments, The Cornell Hotel and

Restaurant Quarterly, 40 (1) pp. 40-46, Sage Publications. p.42.

64

Teery G. Vavra (1997). Improving your measurement of customer satisfaction: a

guide to creating, conducting, analyzing, and reporting customer satisfaction

measurement programs. American Society for Qualit. p.47.

65

Adopted from Yc Youjic A Critical Review of Customer Satisfaction in Zothumt,

Valore Review of Marketing 1989, Chicago, American Marketing

Association, 1991. Cited in Terry G. Vavra (1997). Improving Your

Measurement of Customer Satisfaction: A Guide to Creating, Conducting,

Analyzing, and Reporting Customer Satisfaction Measurement Programs.

American Society for Qualit. p.46.

66

Yoo, D.K. & Park, J .A. (2007). Perceived service quality Analyzing relationships

among employees, customers, and financial performance. International

Journal of Quality & Reliability Management, 21(9): pp.908-926.

67

Parasuraman, A., Valarie, A. Zeithamal, and Leonard L. Berry (1988),

SERVQUAL: A Multiple-Item Scale for Measuring consumer Perceptions of

Service Quality, Journal of Retailing, Vol.64, No.1, 12-40.

68

Saleh, F. and Ryan, C (1992), Client Perceptions of Hotels A Multi-attribute

Approach, Tourism Management, J une, Vol.13, No.92. pp.163-168.

69

Barsky, J .D. (1992). Customer Satisfaction in the Hotel Industry: Meaning and

Measurement. Hospitality Research Journal, 16(1): pp.51-73.

70

Ivanka, A.H., Suzana, M., Sanja Raspor. Consumer Satisfaction Measurement in

Hotel Industry: Content Analysis Study. p.2.

122

71

Ibid.p.2.

72

Schall, M. (2003). Best Practices in the Assessment of Hotel-guest attitudes. The

Cornell Hotel and Restaurant Administration Quarterly. April: pp. 51-65.

73

Mohsin Asad; Ryan Chris (2005). Service Quality Assessment of 4-staf hotels in

Darwin, Northern Territory, Australia. (Buyers Guide), Journal of Hospitality

and Tourism management, April 01, 2005.

74

Halil Nadiri and Kashif Hussain (2005), Diagnosing the Zone of Tolerance for

Hotel Services, Managing Service Quality, Vol.15, 3, p.261.

75

Rooma Roshnee Ramsaran-Fowdar (2007), Developing a Service Quality

Questionnaire for the Hotel Industry in Mauritius, Journal of Vacation

Marketing; J an. 2007, Vol.13, No.1, p.21.

76

Teas, K.R. (1994), Expectations as a Comparison Standard in Measuring Service

Quality: An Assessment of a Reassessment, Journal of Marketing, Vol.58,

J an, pp.132-139.

77

Halil Nadiri and Kashif Hussain (2005), Diagnosing the Zone of Tolerance for

Hotel Services, Managing Service Quality, Vol.15, 3, p.263.

78

Rooma Roshnee Ramsaran-Fowdar (2007), Developing a Service Quality

Questionnaire for the Hotel Industry in Mauritius, Journal of Vacation

Marketing; J an. 2007, Vol.13, No.1, p.21

79

Kano, N., N. Seraku, et al (1996). Must-be Quality and Attractive Quality. The

Best on Quality. 7: 165.

80

Edvardsson, B., A. Gustafsson, et al. (2000). New Service Development and

Innovation in the New Economy. Lund, Studentlitteratur.

81

Bilsen Bilgili & Sevtap nal (2008). Kano Model Application for Classifying the

Requirements of University Students, MIBES Conference. pp.31-46.

82

Ibid.p.36.

83

Barbara Everitt Bryant & Claes Fornell (2005). American Customer Satisfaction

Index, Methodology, Report: April, 2005.

123

84

Terry G. Vavra (1997). Improving Your Measurement of Customer Satisfaction: A

Guide to Creating, Conducting, Analyzing, and Reporting Customer

Satisfaction Measurement Programs. American Society for Qualit. p.12.

85

Ibid.p.12.

86

Luo, Xueming and C.B. Bhattacharya (2006). Corporate Social Responsibility,

Customer Satisfaction, and Market Value, Journal of Marketing, Vol.70,

pp.1-18.

87

Halir Nadiri & Kashif Hussain (2005) Diagnosing the Zone of Tolerance for Hotel

Services, Managing Service Quality, Vol.15. No.3.

88

Zeithaml, V.A. Berry, L.LO. and Parasuraman, A. (1993). The nature and

determinants of customer expectations of service, Journal of the Academy of

Marketing Science, Vol.21 No.1, p.4.

89

Halir Nadiri & Kashif Hussain (2005) Diagnosing the Zone of Telerance for Hotel

Services, Managing Service Quality, Vol.15. No.3.

90

Paula A, Cauchick Miguel; Mrcia Terra da Silva; Elias L. Chiosini, and Klaus

Schtzer.

91

Cronin, J . and Taylor, S. SERVPERF versus SERVQUAL (1994). Reconciling

performance based and perceptions minus expectations measurement of

service quality, Journal of Marketing, Vol.58, No.1.

92

Lee H., Lee Y., Yoo D. (2000). The determinants of perceived quality and its

relationship with satisfaction, Journal of Services Marketing, Vol.14, No.3.

93

Parasuraman, A., Zeithamal, V.A. and Berry, L.L. (1994), Reassessment of

Expectations as a Comparison Standard in Measuring Service Quality:

Implications for future Research, Journal of Marketing, Vol.58, J an pp.111-

124.

You might also like

- Theoretical FrameworkDocument5 pagesTheoretical FrameworkMa. Janelle Bendanillo100% (3)

- Pantaloons Final MRDocument40 pagesPantaloons Final MRVERGUNTSTAFFEN100% (5)

- Measuring Customer Satisfaction: Exploring Customer Satisfaction’s Relationship with Purchase BehaviorFrom EverandMeasuring Customer Satisfaction: Exploring Customer Satisfaction’s Relationship with Purchase BehaviorRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (6)

- Absolute Value: What Really Influences Customers in the Age of (Nearly) Perfect InformationFrom EverandAbsolute Value: What Really Influences Customers in the Age of (Nearly) Perfect InformationRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (15)

- Customersatisfaction TheoriesDocument14 pagesCustomersatisfaction TheoriesMutebi AndrewNo ratings yet

- New Edit Pro Honda SahibQQQDocument69 pagesNew Edit Pro Honda SahibQQQMuhammad IbrahimNo ratings yet

- 10 - Isac, Rusu 1Document7 pages10 - Isac, Rusu 1Rafel KurniaNo ratings yet

- According To Hasemark and AlbinssonDocument6 pagesAccording To Hasemark and AlbinssonAshwinKumarNo ratings yet

- Chpt4Customersatisfactiontheories PDFDocument38 pagesChpt4Customersatisfactiontheories PDFJenekNo ratings yet

- Theories For ResearchDocument6 pagesTheories For ResearchRissabelle CoscaNo ratings yet

- Customer Satisfaction TheoryDocument5 pagesCustomer Satisfaction Theorythar tharNo ratings yet

- Chpt4 ThConsumer Satisfaction Theories A Critical RevieweoriesDocument35 pagesChpt4 ThConsumer Satisfaction Theories A Critical RevieweoriesJithendar Reddy67% (3)

- Consumer Dissatisfaction: The Effect of Disconfirmed Expectancy On Perceived Product PerformanceDocument8 pagesConsumer Dissatisfaction: The Effect of Disconfirmed Expectancy On Perceived Product PerformanceMaria Goreti VongNo ratings yet

- Practical Research 1 - Group 1Document19 pagesPractical Research 1 - Group 1Mack Jigo DiazNo ratings yet

- The Effect of Service Performance and Ski Resort Image On Skiers SatisfactionDocument18 pagesThe Effect of Service Performance and Ski Resort Image On Skiers SatisfactionCornelia TarNo ratings yet

- Oliver, R. L. (2010)Document5 pagesOliver, R. L. (2010)19047Almira Ayu Vania AdyagariniNo ratings yet

- American Marketing AssociationDocument16 pagesAmerican Marketing AssociationmealletaNo ratings yet

- 26 A Study On Customer Satisfaction Towards Asian PaintsDocument77 pages26 A Study On Customer Satisfaction Towards Asian Paintsshubhank RaoNo ratings yet

- Customer Satisfaction Towards Services of VodafoneDocument106 pagesCustomer Satisfaction Towards Services of VodafoneChandan Srivastava100% (4)

- Research About: THE LEVEL OF SATISFACTION OF GRADE 12 BREAD AND PASTRY STUDENTS IN THE UNIVERSITY OF THE CORDILLERAS IN USING THE BAKING LABORATORYDocument28 pagesResearch About: THE LEVEL OF SATISFACTION OF GRADE 12 BREAD AND PASTRY STUDENTS IN THE UNIVERSITY OF THE CORDILLERAS IN USING THE BAKING LABORATORYStatio NeryNo ratings yet

- Yuksel (2001) The Expectancy Disconfirmation ParadigmDocument26 pagesYuksel (2001) The Expectancy Disconfirmation ParadigmMariana NunezNo ratings yet

- A Literature Review and Critique On Customer SatisfactionDocument6 pagesA Literature Review and Critique On Customer SatisfactionNguyễn VyNo ratings yet

- Service Quality, Customer Satisfaction, and Customer Value: A Holistic PerspectiveDocument16 pagesService Quality, Customer Satisfaction, and Customer Value: A Holistic PerspectiveMostaMostafaNo ratings yet

- A Literature Review and Critique On Customer SatisfactionDocument6 pagesA Literature Review and Critique On Customer SatisfactionTanima BhaumikNo ratings yet

- A Study On Customer Satisfaction Towards National Garage Raipur CGDocument74 pagesA Study On Customer Satisfaction Towards National Garage Raipur CGjassi7nishadNo ratings yet

- A Study On Customer Satisfaction Towards National Garage Raipur CGDocument74 pagesA Study On Customer Satisfaction Towards National Garage Raipur CGjassi7nishadNo ratings yet

- 2 FTPDocument28 pages2 FTPBhuvanesh KumarNo ratings yet

- The Service Recovery Paradox: True But Overrated?: Michels@T-Bird - EduDocument25 pagesThe Service Recovery Paradox: True But Overrated?: Michels@T-Bird - EduEn ZieNo ratings yet

- ChapterDocument14 pagesChapterVishnuNadarNo ratings yet

- A Comprehensive Model of Customer Satisfaction in Hospitality and Tourism: Strategic Implications For ManagementDocument12 pagesA Comprehensive Model of Customer Satisfaction in Hospitality and Tourism: Strategic Implications For ManagementDevikaNo ratings yet

- Service Gap Analysis and Kano Model in It Services of Cenveo SolutionsDocument18 pagesService Gap Analysis and Kano Model in It Services of Cenveo SolutionsbaluNo ratings yet

- Juli Lit ReviwDocument2 pagesJuli Lit ReviwjuliNo ratings yet

- Presentation OutlineDocument6 pagesPresentation OutlineMKWD NRWMNo ratings yet

- Prospect Theory and SERVQUAL: Management September 2014Document15 pagesProspect Theory and SERVQUAL: Management September 2014rina FitrianiNo ratings yet

- Customer Satisfaction (Often Abbreviated As Csat, More Correctly Csat) Is A TermDocument9 pagesCustomer Satisfaction (Often Abbreviated As Csat, More Correctly Csat) Is A TermMubeenNo ratings yet

- Distinguishing Service Quality and Customer Satisfaction: The Voice of The ConsumerDocument27 pagesDistinguishing Service Quality and Customer Satisfaction: The Voice of The ConsumerSoumya MukherjeeNo ratings yet

- Final ResearchDocument45 pagesFinal ResearchFrances Cleo TubadaNo ratings yet

- A - About Validity and ReliabilityDocument13 pagesA - About Validity and Reliabilitydikahmads100% (1)

- Customer Satisfaction: A Meta-Analysis of The Empirical EvidenceDocument20 pagesCustomer Satisfaction: A Meta-Analysis of The Empirical EvidenceXứ TrầnNo ratings yet

- Chapter 12 Measurement Scaling Reliability and Validity - ExtensionDocument19 pagesChapter 12 Measurement Scaling Reliability and Validity - Extensionsaad bin sadaqatNo ratings yet

- Chapter - 1Document74 pagesChapter - 1Harry HS100% (1)

- Factors Influencing Cargo Customer Satisfaction A Case Study of Kenya Airways Cargo Nick MBADocument40 pagesFactors Influencing Cargo Customer Satisfaction A Case Study of Kenya Airways Cargo Nick MBAFrank Munyua MwangiNo ratings yet

- Chapter 3 MLMDocument11 pagesChapter 3 MLMMatachi MagandaNo ratings yet

- Reliability and Validity in Marketing ResearchDocument11 pagesReliability and Validity in Marketing ResearchDr. Ashokan. CNo ratings yet

- Waiting Line Management: Unit IntroductionDocument37 pagesWaiting Line Management: Unit IntroductionAsora Yasmin snehaNo ratings yet

- Research Chapter 1 and Foreign Lit1Document6 pagesResearch Chapter 1 and Foreign Lit1Christian MartinNo ratings yet

- Final MainDocument36 pagesFinal MainGiga ByteNo ratings yet

- Effect of Customer SatisfactionDocument9 pagesEffect of Customer SatisfactionLongyapon Sheena StephanieNo ratings yet

- Relationships Among Service Quality, Customer Satisfaction and Customer Loyalty in Jordanian Restaurants SectorDocument5 pagesRelationships Among Service Quality, Customer Satisfaction and Customer Loyalty in Jordanian Restaurants Sectorranosh82No ratings yet

- Marketing: Customer Satisfaction Is A Term Frequently Used inDocument7 pagesMarketing: Customer Satisfaction Is A Term Frequently Used inLucky YadavNo ratings yet

- Quantitative Methods For Decision-Makers: Dr. Solange Charas October 25, 2021Document39 pagesQuantitative Methods For Decision-Makers: Dr. Solange Charas October 25, 2021Layla LiNo ratings yet

- American Marketing AssociationDocument8 pagesAmerican Marketing AssociationDiana YaguanaNo ratings yet

- Defining Customer SatisfactionDocument27 pagesDefining Customer SatisfactionTamil VaananNo ratings yet

- Measuring Customer Feedback Response and SatisfactDocument13 pagesMeasuring Customer Feedback Response and SatisfacttanandesyeNo ratings yet

- Chapter Eight Discussion Questions: ENGM 620 Fall 2010 Session Five Homework SolutionsDocument5 pagesChapter Eight Discussion Questions: ENGM 620 Fall 2010 Session Five Homework SolutionsIManNo ratings yet

- An Overview of Customer Satisfaction ModelsDocument12 pagesAn Overview of Customer Satisfaction ModelskutukankutuNo ratings yet

- Compatibility of Pharmaceutical Solutions and Contact Materials: Safety Assessments of Extractables and Leachables for Pharmaceutical ProductsFrom EverandCompatibility of Pharmaceutical Solutions and Contact Materials: Safety Assessments of Extractables and Leachables for Pharmaceutical ProductsNo ratings yet

- Textbook of Urgent Care Management: Chapter 11, Urgent Care AccreditationFrom EverandTextbook of Urgent Care Management: Chapter 11, Urgent Care AccreditationNo ratings yet

- Strategy Mapping: An Interventionist Examination of a Homebuilder's Performance Measurement and Incentive SystemsFrom EverandStrategy Mapping: An Interventionist Examination of a Homebuilder's Performance Measurement and Incentive SystemsNo ratings yet

- Newtech Advant Business Plan9 PDFDocument38 pagesNewtech Advant Business Plan9 PDFdanookyereNo ratings yet

- Basic Financial Econometrics PDFDocument167 pagesBasic Financial Econometrics PDFdanookyereNo ratings yet

- BoA CFE-CMStatistics 2017 PDFDocument272 pagesBoA CFE-CMStatistics 2017 PDFdanookyereNo ratings yet

- The Role of Communication in Contemporary MarketingDocument4 pagesThe Role of Communication in Contemporary MarketingdanookyereNo ratings yet

- Joshua 1:9: Bible Quotations For The Bible Reading MarathonDocument5 pagesJoshua 1:9: Bible Quotations For The Bible Reading MarathondanookyereNo ratings yet

- Consumer Buying DecisionsDocument2 pagesConsumer Buying DecisionsdanookyereNo ratings yet

- Personal Income Tax Rates in GhanaDocument2 pagesPersonal Income Tax Rates in GhanadanookyereNo ratings yet

- Importance of A Trial BalanceDocument1 pageImportance of A Trial Balancedanookyere100% (3)