Professional Documents

Culture Documents

The Hammer and The Flute - Women, Power and Spirit Possession

The Hammer and The Flute - Women, Power and Spirit Possession

Uploaded by

Rusalka25Copyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- Narrative Methods For The Human Science by Catherine Kohler RiessmanDocument379 pagesNarrative Methods For The Human Science by Catherine Kohler RiessmanNatalyaWright78% (9)

- Revolution of The HeartDocument385 pagesRevolution of The Heartexcelsis_No ratings yet

- Tabernacles of Clay: Sexuality and Gender in Modern MormonismFrom EverandTabernacles of Clay: Sexuality and Gender in Modern MormonismRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (3)

- From Darwin to Eden: A Tour of Science and Religion based on the Philosophy of Michael Polanyi and the Intelligent Design MovementFrom EverandFrom Darwin to Eden: A Tour of Science and Religion based on the Philosophy of Michael Polanyi and the Intelligent Design MovementNo ratings yet

- African American Female Mysticism: Nineteenth-Century Religious ActivismFrom EverandAfrican American Female Mysticism: Nineteenth-Century Religious ActivismNo ratings yet

- Science as Social Knowledge: Values and Objectivity in Scientific InquiryFrom EverandScience as Social Knowledge: Values and Objectivity in Scientific InquiryRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (8)

- Offending Women: Power, Punishment, and the Regulation of DesireFrom EverandOffending Women: Power, Punishment, and the Regulation of DesireNo ratings yet

- Revival from Below: The Deoband Movement and Global IslamFrom EverandRevival from Below: The Deoband Movement and Global IslamNo ratings yet

- The Quest for God and the Good: World Philosophy as a Living ExperienceFrom EverandThe Quest for God and the Good: World Philosophy as a Living ExperienceNo ratings yet

- (Studies in Feminist Philosophy) Charlotte Witt - The Metaphysics of Gender (Studies in Feminist Philosophy) - Oxford University Press, USA (2011)Document168 pages(Studies in Feminist Philosophy) Charlotte Witt - The Metaphysics of Gender (Studies in Feminist Philosophy) - Oxford University Press, USA (2011)EHTMAM KHAN100% (3)

- The Terror That Comes in the Night: An Experience-Centered Study of Supernatural Assault TraditionsFrom EverandThe Terror That Comes in the Night: An Experience-Centered Study of Supernatural Assault TraditionsRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (1)

- Women in God’s Army: Gender and Equality in the Early Salvation ArmyFrom EverandWomen in God’s Army: Gender and Equality in the Early Salvation ArmyNo ratings yet

- Love's Uncertainty: The Politics and Ethics of Child Rearing in Contemporary ChinaFrom EverandLove's Uncertainty: The Politics and Ethics of Child Rearing in Contemporary ChinaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- 1998, Clinton Bennett-In Search of The Sacred PDFDocument225 pages1998, Clinton Bennett-In Search of The Sacred PDFFarman AliNo ratings yet

- The Jewel House: Elizabethan London and the Scientific RevolutionFrom EverandThe Jewel House: Elizabethan London and the Scientific RevolutionNo ratings yet

- Bodies of Knowledge: Sexuality, Reproduction, and Women's Health in the Second WaveFrom EverandBodies of Knowledge: Sexuality, Reproduction, and Women's Health in the Second WaveNo ratings yet

- Moral Laboratories: Family Peril and the Struggle for a Good LifeFrom EverandMoral Laboratories: Family Peril and the Struggle for a Good LifeNo ratings yet

- 9734-Article Text-17942-1-10-20200203 PDFDocument12 pages9734-Article Text-17942-1-10-20200203 PDFLaib AbirNo ratings yet

- Science Mythology in Mary Shelley's Frankenstein A Case Study Using Roland Barthes' SemioticsDocument5 pagesScience Mythology in Mary Shelley's Frankenstein A Case Study Using Roland Barthes' SemioticsInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNo ratings yet

- Mircea Eliade - The Sacred The ProfaneDocument25 pagesMircea Eliade - The Sacred The ProfaneRorajma100% (2)

- The Golden AssDocument632 pagesThe Golden AsshenryhoodNo ratings yet

- Eliade, Mircea & Kitagawa, Joseph M (Eds.) - The History of Religion PDFDocument129 pagesEliade, Mircea & Kitagawa, Joseph M (Eds.) - The History of Religion PDFjalvarador1710No ratings yet

- Heinz Werner and Developmental Science PDFDocument9,351 pagesHeinz Werner and Developmental Science PDFDayse Albuquerque0% (1)

- Thinking Woman: A Philosophical Approach to the Quandary of GenderFrom EverandThinking Woman: A Philosophical Approach to the Quandary of GenderNo ratings yet

- Responsible Belief: Limitations, Liabilities, and MeliorationFrom EverandResponsible Belief: Limitations, Liabilities, and MeliorationNo ratings yet

- pt1 - Narrative-Methods-For-The-Human-Science-9780761929987 - Compress-1-145Document145 pagespt1 - Narrative-Methods-For-The-Human-Science-9780761929987 - Compress-1-145carmenblackNo ratings yet

- The Paradox of Hope: Journeys through a Clinical BorderlandFrom EverandThe Paradox of Hope: Journeys through a Clinical BorderlandNo ratings yet

- Abandoned to Lust: Sexual Slander and Ancient ChristianityFrom EverandAbandoned to Lust: Sexual Slander and Ancient ChristianityNo ratings yet

- Talking Gender: Public Images, Personal Journeys, and Political CritiquesFrom EverandTalking Gender: Public Images, Personal Journeys, and Political CritiquesNo ratings yet

- Heaven's Interpreters: Women Writers and Religious Agency in Nineteenth-Century AmericaFrom EverandHeaven's Interpreters: Women Writers and Religious Agency in Nineteenth-Century AmericaNo ratings yet

- Behaviorism and Logical PositivismDocument419 pagesBehaviorism and Logical PositivismNicolas Gonçalves100% (2)

- Corey DisDocument299 pagesCorey DisJovanaNo ratings yet

- The Self Beyond Itself: An Alternative History of Ethics, the New Brain Sciences, and the Myth of Free WillFrom EverandThe Self Beyond Itself: An Alternative History of Ethics, the New Brain Sciences, and the Myth of Free WillNo ratings yet

- Ahuvia Mika, Israel Among The AngelsDocument291 pagesAhuvia Mika, Israel Among The AngelsPosa Nicolae Toma100% (2)

- The Soul's Economy: Market Society and Selfhood in American Thought, 1820-1920From EverandThe Soul's Economy: Market Society and Selfhood in American Thought, 1820-1920No ratings yet

- No Longer Patient - Feminist Ethics and Health Care - Sherwin, SusanDocument312 pagesNo Longer Patient - Feminist Ethics and Health Care - Sherwin, SusanSezen DemirhanNo ratings yet

- Creation’s Slavery and Liberation: Paul’s Letter to Rome in the Face of Imperial and Industrial AgricultureFrom EverandCreation’s Slavery and Liberation: Paul’s Letter to Rome in the Face of Imperial and Industrial AgricultureNo ratings yet

- Desire and the Ascetic Ideal: Buddhism and Hinduism in the Works of T. S. EliotFrom EverandDesire and the Ascetic Ideal: Buddhism and Hinduism in the Works of T. S. EliotNo ratings yet

- Searching for Scientific Womanpower: Technocratic Feminism and the Politics of National Security, 1940-1980From EverandSearching for Scientific Womanpower: Technocratic Feminism and the Politics of National Security, 1940-1980No ratings yet

- Black Reason, White Feeling: The Jeffersonian Enlightenment in the African American TraditionFrom EverandBlack Reason, White Feeling: The Jeffersonian Enlightenment in the African American TraditionNo ratings yet

- The Wisdom of the Liminal: Evolution and Other Animals in Human BecomingFrom EverandThe Wisdom of the Liminal: Evolution and Other Animals in Human BecomingNo ratings yet

- Believe Not Every Spirit: Possession, Mysticism, & Discernment in Early Modern CatholicismFrom EverandBelieve Not Every Spirit: Possession, Mysticism, & Discernment in Early Modern CatholicismRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (2)

- Christian Moderns: Freedom and Fetish in the Mission EncounterFrom EverandChristian Moderns: Freedom and Fetish in the Mission EncounterRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (2)

- The Ploy of Instinct: Victorian Sciences of Nature and Sexuality in Liberal GovernanceFrom EverandThe Ploy of Instinct: Victorian Sciences of Nature and Sexuality in Liberal GovernanceNo ratings yet

- For The Love of Metaphysics Nihilism and The Conflict of Reason From Kant To Rosenzweig Karin Nisenbaum Full ChapterDocument67 pagesFor The Love of Metaphysics Nihilism and The Conflict of Reason From Kant To Rosenzweig Karin Nisenbaum Full Chapterbetty.washington515100% (8)

- (Oxford Philosophical Monographs) Markovits, Julia - Moral Reason-Oxford University Press (2014)Document225 pages(Oxford Philosophical Monographs) Markovits, Julia - Moral Reason-Oxford University Press (2014)kxt9qys4d7No ratings yet

- Self-Consciousness and the Critique of the Subject: Hegel, Heidegger, and the PoststructuralistsFrom EverandSelf-Consciousness and the Critique of the Subject: Hegel, Heidegger, and the PoststructuralistsNo ratings yet

- Ingenious Citizenship: Recrafting Democracy For Social Change by Charles T. LeeDocument48 pagesIngenious Citizenship: Recrafting Democracy For Social Change by Charles T. LeeDuke University Press100% (1)

- Scrambling for Africa: AIDS, Expertise, and the Rise of American Global Health ScienceFrom EverandScrambling for Africa: AIDS, Expertise, and the Rise of American Global Health ScienceRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (2)

- Feminism and Affect at the Scene of Argument: Beyond the Trope of the Angry FeministFrom EverandFeminism and Affect at the Scene of Argument: Beyond the Trope of the Angry FeministNo ratings yet

- SANS 3000-4-2011 - Railway Safety RegulatorDocument115 pagesSANS 3000-4-2011 - Railway Safety RegulatorBertus ChristiaanNo ratings yet

- 1969 SP-51 RCA Power CircuitsDocument452 pages1969 SP-51 RCA Power CircuitsasccorreaNo ratings yet

- App 001 PresentationDocument23 pagesApp 001 PresentationReign Crizzelle BarridNo ratings yet

- Critikon Dinamap Compact - Service Manual 2Document78 pagesCritikon Dinamap Compact - Service Manual 2Ayaovi JorlauNo ratings yet

- Barou 2014Document18 pagesBarou 2014tarry horalikNo ratings yet

- Dodds-Ancient Concept of Progress 4Document28 pagesDodds-Ancient Concept of Progress 4Trad AnonNo ratings yet

- Full Download Zoology 9th Edition Miller Test BankDocument35 pagesFull Download Zoology 9th Edition Miller Test Bankcaveneywilliams100% (25)

- Proposal NewDocument19 pagesProposal NewAzimSyahmiNo ratings yet

- Impact of Online Gaming in Academic Performance of Students of Our Lady of Fatima University of Antipolo S.Y. 2021-2022Document9 pagesImpact of Online Gaming in Academic Performance of Students of Our Lady of Fatima University of Antipolo S.Y. 2021-2022Ralph Noah LunetaNo ratings yet

- ASTM D6905 - 03 Standard Test Method For Impact Flexibility of Organic CoatingsDocument3 pagesASTM D6905 - 03 Standard Test Method For Impact Flexibility of Organic CoatingsCemalOlgunÇağlayan0% (1)

- India Data Center OpportunityDocument7 pagesIndia Data Center OpportunitysharatjuturNo ratings yet

- Modular Coordination IbsDocument5 pagesModular Coordination IbsCik Mia100% (1)

- Comparing Effectiveness of Family Planning Methods: How To Make Your Method More EffectiveDocument1 pageComparing Effectiveness of Family Planning Methods: How To Make Your Method More EffectiveGabrielle CatalanNo ratings yet

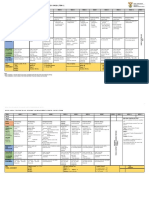

- 1.630 ATP 2023-24 GR 9 EMS FinalDocument4 pages1.630 ATP 2023-24 GR 9 EMS FinalNeliNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1 Introduction: 1.1 Purpose of The Manual For Micro-Hydro DevelopmentDocument7 pagesChapter 1 Introduction: 1.1 Purpose of The Manual For Micro-Hydro DevelopmentAde Y SaputraNo ratings yet

- Zanskar Expedition Himalaya Com MonkDocument1 pageZanskar Expedition Himalaya Com MonkIvan IvanicNo ratings yet

- Real-Time Workshop: For Use With SimulinkDocument130 pagesReal-Time Workshop: For Use With SimulinkNadjib HadjaliNo ratings yet

- FR MSGR Rossetti Deliverence PrayerDocument9 pagesFR MSGR Rossetti Deliverence Prayerjohnboscodharan100% (2)

- SOP Forensic Medicine ServicesDocument83 pagesSOP Forensic Medicine ServicesShafini Shafie100% (1)

- RTV Coating Suwarno Fari FinalDocument6 pagesRTV Coating Suwarno Fari FinalFari PratomosiwiNo ratings yet

- Maharashtra HSC Mathematics Paper 1Document18 pagesMaharashtra HSC Mathematics Paper 1YouTibeNo ratings yet

- Nahla Youisf-ResumeDocument2 pagesNahla Youisf-ResumenahlaNo ratings yet

- Interest Rate Cap Structure Definition, Uses, and ExamplesDocument2 pagesInterest Rate Cap Structure Definition, Uses, and ExamplesACC200 MNo ratings yet

- 2004 Waziristan Complex Chem Data Interptretaion SHAKIRULLAH & MOHAMMAD IHSAN AFRIDIDocument16 pages2004 Waziristan Complex Chem Data Interptretaion SHAKIRULLAH & MOHAMMAD IHSAN AFRIDInoor abdullahNo ratings yet

- CEE Download Full Info - 07.15 PDFDocument29 pagesCEE Download Full Info - 07.15 PDFFaizal FezalNo ratings yet

- Gramsci and HegemonyDocument9 pagesGramsci and HegemonyAbdelhak SaddikNo ratings yet

- FpseDocument2 pagesFpseosmar weyhNo ratings yet

- Gigabyte Ga-K8ns Rev 1.1 SCHDocument37 pagesGigabyte Ga-K8ns Rev 1.1 SCHMohammad AhamdNo ratings yet

- Term-Project-Ii-Bch3125 ADocument8 pagesTerm-Project-Ii-Bch3125 APure PureNo ratings yet

- WHO IVB 11.09 Eng PDFDocument323 pagesWHO IVB 11.09 Eng PDFniaaseepNo ratings yet

The Hammer and The Flute - Women, Power and Spirit Possession

The Hammer and The Flute - Women, Power and Spirit Possession

Uploaded by

Rusalka25Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

The Hammer and The Flute - Women, Power and Spirit Possession

The Hammer and The Flute - Women, Power and Spirit Possession

Uploaded by

Rusalka25Copyright:

Available Formats

The Hammer and the Flute

The Hammer

and the Flute

Women, Power, and

Spirit Possession

Mary Keller

The Johns Hopkins University Press

Baltimore & London

:oo: The Johns Hopkins University Press

All rights reserved. Published :oo:

Printed in the United states of America on acid-free paper

8 ; o : r

The Johns Hopkins University Press

:;r North Charles Street

Baltimore, Maryland :r:r8-o

www.press.jhu.edu

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Keller, Mary, ro

The hammer and the ute : women, power, and spirit possession /

Mary Keller.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

isn o-8or8-o;8;-8 (alk. paper)

r. Spirit possession. :. WomenReligious life. I. Title.

nt8:.k :oor

:r.:dc:r

:ooroo:or

A catalog record for this book is available from the British Library

Contents

Preface vii

Introduction r

Part r. Reorienting Possession in Theory :r

Chapter r. Signifying Possession :

Chapter :. Reorienting Possession

Chapter . Flutes, Hammers, and Mounted Women ;

Part :. The Work, War, and Play of Possession ro

Chapter . Work ro

Chapter . War r:

Chapter o. Play(s) ro:

Conclusion ::

Notes :r

Bibliography :;r

Index :8r

Preface

This book is a methodological argument about how contemporary scholar-

ship approaches bodies that are possessed by ancestors, deities, or spirits. It

began as a question of feminist historiography when I was rst introduced

to Greek maenads during a seminar with Professor Patricia Cox Miller on

gender in Greek antiquity: How might one evaluate the agency of a womans

body in fth-century Athens that is possessed; a body that is running freely

and not conned to a traditional womens space but free only because it

is a body that is overcome by a divine agency? What began as a problem for

feminist historiography then entered into an interdisciplinary conversation

with contemporary anthropology, psychology, and sociology as I became

aware of the extensive literature on spirit possession. Most contemporary

examples of possession are found where indigenous traditions are still

strong, either in rural areas or among immigrant communities in urban

areas. Possessed bodies are extremely dierent from the contemporary

Western model of proper subjectivity. They are volatile bodies that attract

the eye of observers, and often their volatility is related to erotic or outra-

geous activity. Possessed bodies are not individual bodies. They are not often

held personally responsible for their actions by their communities. Within

their communities, possessed bodies are rigorously scrutinized in order to

determine that in fact an ancestor, deity, or spirit had overcome them; how-

ever, that is an interpretation that would be dicult if not impossible for

most scholars to represent as the truth of the matter. By and large, schol-

arly approaches to possessed bodies have reinterpreted them as repressed

psychological bodies, oppressed sociological bodies, or oppressed womens

viii Preface

bodies. What I have tried to do is to deliver a religious studies approach to

these bodies that can incorporate indigenous interpretations into a mean-

ingful, critical interpretation of the power relationships these bodies nego-

tiate.

As I look back to the history that produced my engagement with pos-

sessed bodies, I want to thank the incredible collection of teachers that

brought me to this niche, which lies at the intersection of feminist philoso-

phy and critical methodology in the study of religion. From my introduction

to feminist theory with Wendy Brown and Rosemary Tong to the introduc-

tory units in religious studies run by Mark C. Taylor and H. Ganse Little,

Jr., from Jewish feminism with Judith Wegner to gender studies in Judaism

with Charlotte Fonrobert via Daniel Boyarin, from history of religions

methodology with Charles Long and Jorunn Buckley to postmodern theol-

ogy with Mark Taylor and Charlie Winquist, from nothingness with David

Miller to emptiness with Dick Pilgrim, I have had an incredible opportunity

to study with people whose intellectual concerns inspired me.

More specically, the research in this book was rst pursued as a disser-

tation that began when I was taking courses in Greek antiquity with Patricia

Miller simultaneously with an anthropology and postcolonial theory unit

taught by Ann G. Goldboth of which included stories about possessed

women. Professor Miller supported the development of my argumenta

task that required her to give extensive feedback, which she did so rigor-

ously and graciously. Ann Gold read and commented upon several papers

and drafts of chapters, always oering support and providing a critical read-

ing of the theory I was using based on her exhaustive study and experience

of the practice of anthropology. Professor Phillip Arnolds lecture to the

department on place was important as I thought about the place-taking

of the Malaysian spirits discussed in Chapter , Work, and also the impor-

tance of land and the Shona ancestors discussed in Chapter , War. Pro-

fessor Micere Mugo took time to listen to my ideas and then fatefully told

me of the Nehanda mhondoro in Zimbabwe, opening up a new area of study

that was far too compelling to leave behind. In pursuit of research into Afri-

can traditional religions I received information from Christina Le Doux,

subject librarian for gender studies at the University of South Africa. Claire

Jones of the University of Washington and Douglas Dziva from the Univer-

sity of Natal both read earlier drafts of Chapter and generously provided

ix Preface

me with technical as well as methodological critiques. Douglas kindly

shared sections of his dissertation manuscript, and both scholars provided

me much-needed support as I stepped into their areas of expertise. Chapter

, Play(s), was inuenced by Professor David Millers play on lectures and

lectures on play. Professor Ken Frieden read an earlier draft of the section

on The Dybbuk, which was also a new area of research for me. His careful

critique and advice regarding technical as well as methodological issues in

the study of Yiddish arts were very helpful. I take his concern seriously

about the problems raised when nonspecialists draw from resources that

require nuanced and developed study.

The risk I have taken in this book is to raise a very specic question about

how scholars represent and evaluate the agency of possessed bodies, and I

have applied the question to areas of study in which I am not an expert. I

would like to think that I have asked my question well enough that it will

be of interest to those people who are experts and who can engage with my

argument, bringing it to greater precision and depth. What is exciting for

me is that the unique linguistic, geographical, historical, and cultural ele-

ments of each place in which I have studied possessed women broaden the

horizons by which one can conceive of subjectivity; this is an area that fur-

ther scholarly research and argument can bring to greater accuracy. I have

beneted from the expertise of others as I pursued my research; any short-

comings are my own.

There have been many important friends and colleagues whose support

was vital for health and sanity and also for their questions and critiques.

These include Judith Poxon, Robert Glass, Yianna Liatsos, Corinne Demp-

sey Corigliano, Craig Burgdo, Heath Atchley, Mehnaz Afridi, Judy Clark,

Kathryn Lanier, Sebrena McBean, Dean David Potter, Nancy Vedder, Di-

onne Smith, and the gang in the academic advising oce where I worked

for two years. I began my rst teaching position at the University of Stirling

in Scotland as I nished this manuscript and want to thank the Religious

Studies Department for their support. While the larger university system

in Britain is driven to distraction by RAE deadlines, which for the sake of

measuring research output push scholars to publish before they feel their

manuscripts are ready, Keith Whitelam and Richard King as my heads of

department continued to express their condence in this project and en-

couraged me to focus my energies on completion of the manuscript. Richard

x Preface

King and Jeremy Carrette read chapters and inspired me with their intellec-

tual debates, while Yvonne McClymont and Julie Dawson helped me to

keep all the res going. The department encouraged us to teach our areas

of research, and I want to thank the students at the University of Stirling

who participated in my rst attempts to teach these ideas back in . As

a class they taught me how to present the progression of my argument. Fi-

nally, the team at the Johns Hopkins University Press has been very helpful

and I want to thank Carol Ehrlich, who copyedited the manuscript with the

greatest care and attention to detail.

To my parents and grandparents, who have supported me throughout

my many years of education with humor, perspective, and scal hugs, I ex-

tend the deepest gratitude. I am often writing to you as I work. Tom Kee-

gan, new husband and new father, acted as the most important editorial

force any student of critical theory could have by repeatedly asking me what

I was trying to say. If readers nd the argument to be clear and the text to

be useful for classrooms, it has been the product of many revisions guided

by colleagues and my husband.

Vivian Benton provided me with housing throughout seven years of post-

graduate study, and it is to her that I dedicate this book. She provided impa-

tiens in the summer (for the owerbed) and two oors of her house for my

dog to roam. Educator, devoted member of her congregation, devoted wife,

she also provided me a room of ones own, as Virginia Woolf described the

material support necessary to feed body and soul in the pursuit of academic

studies. It is hard times for students who want to pursue degrees in the

humanities and it is thanks to Vivian that I did so.

I want to thank the National Archives of Zimbabwe for their permission to

publish pictures from their archives (gs. . and .). James Currey Pub-

lishers granted kind permission to publish David Lans picture (g. .).

The Staatliche Antikensammlungen in Munich granted permission to pub-

lish gure .. The Museum of the City of New York granted permission

to publish gure ..

Introduction

In the s, hundreds of incidents were recorded in the free-trade zones of

Malaysia in which women who worked in the technologically sophisticated

manufacturing plants were possessed by hantu, spirits, often harmful to

human beings, associated with a place, animal, or deceased person.

1

Fifteen

women, possessed by a datuk, an ancestral male spirit associated with a sa-

cred place, closed down an American-owned microelectronics factory in

.

2

The possessed women were so volatile that ten male supervisors

could not control one woman. In a woman at a Japanese-owned factory

saw a weretiger, screamed, and was possessed. She ailed at the machine on

which she worked and fought violently as the foreman and technician pulled

her away. Her supervisor recounted that the workplace used to be a burial

ground, implying that the shop oor was likely to be haunted by angry spir-

its and that women who had weak constitutions needed to be spiritually

vigilant so they would not be possessed.

3

The juxtaposition of technology

and spirits suggests that a complex and profound interaction of worlds was

occurring, centered in the volatile bodies of possessed women.

Some patterns were prevalent in these incidents: The onset was sudden

and the women could later recall only that they had been pounced upon or

attacked abruptly and could not remember anything that had happened

once they were possessed. Those who witnessed the possessions spoke about

the erratic and violent actions of those possessed. The womens voices would

change and they would sob, laugh, and shriek. They were transformed as

they raged and endowed with incredible strength. It often took several men

to subdue the possessed women, removing them from the shop oors before

The Hammer and the Flute

they inicted too much damage on the delicate machinery with which they

worked and also removing them so that they would not aect or infect their

colleagues. In most instances, spiritual vigilance was understood to be the

eective way to avoid becoming possessed, and factories responded by pro-

viding prayer rooms and exorcisms on the shop oors by local bomoh, men

who practiced as specialists in dealing with spirits.

As illustrated in the Malay possessions, the representation of possessed

bodies is compelling, and the philosophical and methodological issues raised

by critically evaluating these representations are legion. As a historian of

religions who is informed by feminist and postcolonial theory, I was rst

attracted to the study of womens possessed bodies because they are every-

where and they constitute a signicant and commanding element of the ma-

terial available to the scholar of women in religion, providing information

about womens religious lives, which otherwise is scarce. Encountering hun-

dreds of accounts of possession raised the following questions: Was there

anything signicant to say about possession in a comparative context or

should each account be studied for its uniqueness? How to evaluate the

agency of a human body that has been overcome by a religious force? What

is the role of a gender analysis in assessing the preponderance of women in

possession traditions? What do we learn from those traditions where men

predominate? How might one evaluate the power of this radical receptivity?

The Malay possessions are one of four examples I focus on in this book

to argue for an approach to the representation and critical evaluation of the

power of possessed bodies, that is, human bodies that are overcome by an-

cestors, deities, or spirits. The underlying methodological problem is how

to represent a body that has attracted one by its forcefulness when there is

no academically acceptable way to verify the very thingsancestors, deities,

and spiritsthat make possessed bodies forceful. In my review of the litera-

ture on possession I identify the relationship between scholars and the bod-

ies that have attracted their intellectual interests. In many instances, that

relationship is very awkward owing to the complexity of representing and

evaluating the power of this dynamic religious body.

Religious traditions in which people are possessed have existed through-

out recorded history and continue to exist on all continents of the globe.

Women predominate in these accounts, and their predominance is noted

by many scholars who attribute it to womens inferior gendered status in

Introduction

patriarchal culture. These analyses suggest that possessions are symptoms

of the womens social and psychological deprivation that happen to nd ex-

pression in culturally specic religious traditions. Traditionally in scholarly

texts, the possessed woman is valenced negatively as psychologically fragile,

permeable, less than a Western, rational agent. The power of her pos-

sessed body is reduced to hysteria at worst and creative therapy at best.

The key to the problem is not that possession studies are sexist or racist but

that a social scientic method is unable to take seriously what the witnesses

to the possession say is the casethat the power that overcomes them

comes from an ancestor, deity, or spirit.

I assume that for most readers from modern, Western backgrounds, the

term spirit possession conjures up images of bizarre and exotic rituals that are

used by unsophisticated people to make sense of their worlds, a kind of

primitive psychotherapy. Terms from the days of colonial conquest, such as

primitive and superstitious, may come to mind. That possession occurs pre-

dominantly among women is likely to t comfortably with the image of a

dark-skinned body, producing yet another fascinating image of the third-

world woman; or, in the context of a possessed Caucasian body, the fact of

womens predominance in possession accounts is likely to t comfortably

with notions of womens propensity for hysterical or psychosomatic symp-

toms. Approaching spirit possession from a postcolonial, feminist per-

spective will break apart these problematic associations and, by doing so,

demonstrate why it is that understanding possession is important for under-

standing dierence in a globalized world, especially the dierences pre-

sented by human bodies that are seen to be religious. In order to get to

this new understanding of possession, one must rethink the relationship of

such bodies to power. As long as possessions are evaluated as beliefs that

lack constitutive force, the possessed body will be evaluated as lacking real

or eective power. This book proposes a framework for understanding pos-

session in the context of reevaluating the relationship of religious bodies to

power so that the paradoxes of the possessed body are understood for their

complexity, not reduced to beliefs that have no real power in the world.

Possession is a problematic term that will be given much greater detail

throughout the book. For heuristic purposes I use a denition that Ann

Grodzins Gold developed in her study of possession in rural Rajasthan. Pos-

session is any complete but temporary domination of a persons body, and

The Hammer and the Flute

the blotting of that persons consciousness, by a distinct alien power of

known or unknown origin.

4

This denition focuses on the specic problem

that is raised by a religious body whose consciousness is blotted by its

experience. The broader category of religious ecstasy as found in the schol-

arly study of religion entails a spectrum of experiences containing phenom-

ena such as mysticism and trance. Spirit possessions reside at the far end of

the spectrum of religious experience in that consciousness is blotted to a

greater extent than with mysticism and therefore the experience is more

dicult to study. What might a scholar claim to know about an experience

that the possessed body does not consciously know or remember? This phil-

osophical problem relates immediately to the evaluations scholars make

about the agency of the possessed bodies. The blotted consciousness and

lack of memory is viewed suspiciously as a traumatic and negative event,

especially from a psychologically informed perspective. Consciousness itself

is viewed as the source of an individuals agency, so that possessions repre-

sent a troubling event. When self-consciousness and raising consciousness

are viewed as tools of empowerment by which an individual can overcome

oppressive social and psychological forces, the possessed body appears to

lack its most eective tool for overcoming oppression, its consciousness. As

with the Malay example, the coincidence of possessed bodies with struggles

against oppression therefore raises a conundrum for scholars who hope

their scholarship might contribute to the alleviation of oppression.

Possession is an important area of study for the historian of religion who

wants to understand the relationship of religious bodies to the triple axes of

power: race, class, and gender. Possession is more often ascribed to women,

the poor, and the religious other (the primitive, the tribal, the third-

world woman, the black, the immigrant). Therefore, representations of pos-

session can give us information about marginalized persons and their

struggles within and against the forces that have an impact upon their lives,

information that is otherwise scarce in historical records. The recent revival

of possession studies is a direct result of the general interest by scholars in

studying the lives of marginalized people. Yet many of these possession

studies have not raised formal questions regarding the representation of reli-

gious others. For instance, How does one evaluate the power of a religious

body? What is the epistemological parameter of a possession study? and

What normative model of subjectivity is undergirding the scholars inter-

Introduction

pretation of the possession? are questions that few scholars have asked as

they analyzed race, class, and gender. If the religious body itself is thought

to represent a kind of oppressed subjectivity, then the possessed body will be

approached from the very start as a body in need of consciousness raising.

Religion: The Anachronistic Space

From a modern, Western perspective, possession phenomena belong to pre-

Enlightenment society. If a possession were to occur in a classroom or a

boardroom in a contemporary Western city, it would likely seem to be out

of place, a bizarre throwback to an earlier time. Anne McClintock has iden-

tied a trope or motif at work in the modern imagination that helps to ex-

plain that out-of-place space.

5

In order to make sense of our encounter with

people from around the globe, the West constructs its idea of itself by con-

trasting its modernity, rationality, and progress to the premodernity, irratio-

nality, and backwardness of other people. McClintock locates one manifes-

tation of this process in Victorian practices of building museums to house

the bric-a-brac of otherness:

In the mapping of progress, images of archaic timethat is, non-European time

were systematically evoked to identify what was historically new about industrial mo-

dernity. . . . Yet in the compulsion to collect and reproduce history whole, time

just when it appears most historicalstops in its tracks. In images of panoptical time,

history appears static, xed, covered in dust. . . . At this point, another trope makes

its appearance. It can be called the invention of anachronistic space, and it reached

full authority as an administrative and regulatory technology in the late Victorian era.

Within this trope, the agency of women, the colonized and the industrial working

class are disavowed and projected onto anachronistic space: prehistoric, atavistic and

irrational, inherently out of place in the historical time of modernity.

6

Her analysis applies equally well to the development of the study of religion,

which in many ways created encyclopedic museums of other peoples reli-

gions that helped to establish the sense that we are more advanced, either

through Christianity or science, than the people whose religions we studied.

Possession is a paradigmatic example of the kind of behavior the Western

scholar is likely to view as inhabiting an anachronistic space to which he

or she can bring progressive models of interpretation (sociological, psycho-

The Hammer and the Flute

logical, medical, performative, or materialist) in order to make this other-

wise extreme behavior meaningful. As Elizabeth Anne Mayes has docu-

mented, the once-prevalent appearance of possession in the Western world

has been successfully marginalized, medicalized, and socialized out of exis-

tence, in part because capitalism and imperialism together came to value

the self-possessed man, thus making ones body one of the ultimate zones

of ownership.

7

While contemporary Western communities have largely done

away with possession, what we have produced instead are psychosis, schizo-

phrenia, multiple personality disorder, and fragmentation, all of which have

gendered tendencies. Multiple personality disorder and other phenomena

of dissociation are more widely diagnosed in women. We do not have pos-

session because it is contradictory to our model of subjectivity as individuals

and self-possessed agents who desire autonomy. Possession requires an ex-

ternal force that overcomes and inhabits the body (threatening the auton-

omy of the individual), whereas madness is located in the mind of an indi-

vidual (threatening ones mental health but not threatening the underlying

model of subjectivity).

Religiousness and religious bodies have not fared well in the modern

imagination of the self-possessed individual. The power of the scientic

method to make sense of the world has ultimately encircled and contained

the parameters within which religiousness is taken seriously. Through the

battles of the Reformation and Counter Reformation against the backdrop

of the burgeoning Enlightenment, a proper ground for religiousness was

carved, one that was determined to reside within the limits of reason

alone, to petition John Lockes work. A self-possessed philosopher could

maintain an acceptable space for his religious life by containing his claims

to knowledge of God within the acceptable rubrics of the reasoning mind.

One can read the development of philosophy in the West, from Locke to

Kant, as the corralling of religiousness within its proper sphere. This has

translated in the modern world to the association of the word religion with

the word belief.

If I say that I am not religious but that my sister is, one is likely to get a

sense that my sister has a bubble in her brain where she cultivates her belief,

her faith. Religiousness is construed as a mental activity. As long as my sister

remains within this proper sphere of religious practice she will be tolerated

as appropriately religious. If her bubble leaks out into the world of work or

Introduction

politics, let alone public demonstrations of rapture or the like, her actions are

likely to be interpreted according to the diagnosis that she is a fanatic, an

ideologue, or sexually repressed. Those whose religiousness is expressed in

their work, in their wars (such as Christian Identity groups), or in public dis-

plays have slid into the anachronistic space of backwardness. They are sus-

pected of being mentally needy because they cannot contain their bubble of

belief properly. This strong association, that religiousness is a matter of be-

lief that transpires in the psychic space of an individual, is extremely limiting

if one is trying to make sense of religiousness in the contemporary world.

Most scholarship on possession employs the assumption that possession

is a matter of belief. Many scholars who study possession will preface their

work by acknowledging that while the people they are studying believe in

possession, the scholar does not. By thinking of religiousness as belief, the

scholar sets up a study of something she or he does not literally believe in.

The power of the possession, an element of which is that the possession has

attracted the scholars attention, is elided in this caveat, giving us a safe

distance from which we maintain our fascination, similar to the experience

of walking through a museum. As long as the power of the possession is

located in the bubble of other peoples beliefs, the scholar constructs him or

herself as safely neutral and objective, reasonable and unaected. Decon-

structing the assumption that possessions are best understood as gments

of belief produces a new approach to religious bodies whereby the possessed

body can be interpreted for its negotiations with power, including its rela-

tionship to the scholar.

Given the anachronistic space that possession conjures and occupies,

then, it is likely that, whether one is looking at possession in Greek antiquity

or in contemporary Malaysia, one will interpret both examples as anachro-

nistic models of religious subjectivity that the contemporary Western sub-

ject has surpassed. What will also become clear as we look more closely at

examples of possession is that while it may seem exotic or anachronistic to

a contemporary Western reader, much of the global population is likely to

have experienced or seen a possession within their immediate community.

In addition, throughout Western history examples of possession are found,

suggesting that possession was a constitutive part of community existence

for a much longer period of time in the Western world than it has been

marginalized as atavistic behavior. It is high time to reorient our approach

The Hammer and the Flute

to possession as a signicant and uniquely powerful phenomenon. We are

already very busy studying possession; the problem is how we have ap-

proached and evaluated the power of the possessed bodies.

Approaching Possession

If religious bodies seem to be anachronistic in these days of science, the

possessed body is the paradigmatic example in that it challenges all of the

norms of contemporary Western evaluations of proper subjectivity. With

autonomy and democracy as two of the ideals that undergird contemporary

evaluations of international human rights, the religious body, which is over-

come by an external agency, which does not speak for itself but is spoken

through, and whose will is the will of the agency that wields it, is anomalous.

We are therefore confronted with an elegant problem for scholarship: how

to approach possession. How might a scholar approach and evaluate the

agency of a body whose consciousness is muted and whose volatility attracts

attention? This problem exists in relation to the checkered history of reli-

gious studies, which has participated in the production of scholarship that

has employed and perpetuated racist and sexist paradigms.

The evaluation and revaluation of possessed womens agency in a com-

parative context raises dicult challenges. The interpretation of agency and

the development of methodology are intimately intertwined at the level of

how one imagines and constructs the relationship between the subjectivity

of possessed women and the practice of religious studies. For example, by

interpreting the possessed woman as an anachronistic type of religious sub-

jectivity, one is constructing oneself as somehow more advanced than she is.

Borrowing from Lawrence Sullivans argument that methodologies impact

the analysis of the others agency, the various examples of possessed women

in this book are approached as complex examples of subjectivity that inform

and expand contemporary theories of agency. Sullivan writes: The funda-

mental question is this: what role will other cultures be allowed to play in

answering these questions about the nature of dierent modes of knowing

and the relations among them? Since the Age of Discovery, myriad cultures

have appeared on the margins of Enlightenment awareness. Normally, they

have been taken as objects of study, subject to the explanatory paradigms of

the natural and human sciences, and thrust into typological schemes which

Introduction

were not of their own making. . . . They have all been taken, in the main, as

data to be explained rather than as theoretical resources for the sciences that

study them.

8

Rather than impose contemporary paradigms of agency as the means by

which to interpret possessed women, I examine selected accounts of pos-

sessed women as theoretical resources for the interpretation of agency and

the development of a feminist methodology for evaluating womens power

in religious traditions. To interpret the agency of possessed women requires

the revaluation of receptivity and permeability beyond the usual, negative

associations of such openness with passivity and weakness. Given the associ-

ation between invagination, receptivity, and femaleness, it is the revaluation

of receptivity that should be of most interest to feminist theorists. When

approached in this way, possessed women are no longer anachronistic but

rather are challenging counterexamples to the theorizations of philosophers

such as Judith Butler and Elizabeth Grosz.

As Sullivan suggests in relation to his study of South American religions,

by recognizing the agency of others, methodology becomes more reexive.

By acknowledging, in our own experience, the agency of South American

peoples in fashioning the world in which we live, we become subject to their

meanings and capable of responding with deliberate interpretations of our

own.

9

What is most interesting about the study of possessions is the possi-

bility of being subjected to the meanings of women who are wielded by their

ancestors, deities, or spirits. Perhaps what we desire in the study of the pos-

sessed woman is that she will actually blow the dust o of our limited, muse-

umied understanding of human subjectivity.

Two issues required new theoretical footing. First, receptivity needed to

be revalued outside of dualistic notions such as active-passive or agent-

victim because it is receptivity that makes the possessed body powerful. Sec-

ond, in contrast to the phenomenologists strategy of bracketing belief, I

propose the creation of a discursive space in which the agency of the pos-

sessing ancestors, deities, or spirits is preserved. To accomplish both goals

I propose the concept of instrumental agency to describe the agency of pos-

sessed bodies. Instrumentality here refers to the power of receptivity, com-

parable metaphorically to a hammer, ute, or horse that is wielded, played,

or mounted. Instrumentality also implies the practical work, war, and play

accomplished by possessed bodies. I use the term agency rather than agent

The Hammer and the Flute

to move beyond the Western idea that agents are the paradigmatic model

of human empowerment. Agency implies action as well as a place where ex-

changes occur. By referring to possessed bodies as instrumental agencies for

the ancestors, deities, or spirits that possess them, I move beyond dualistic

notions of power and explore the complexity of instrumentality. In this way,

possessed bodies are not viewed as passive victims or manipulating agents.

Also, because hammers do not wield themselves and utes do not play

themselves, I carve out the discursive space in which indigenous bodies of

knowledge can be recorded as they are described. Though I cannot weigh

the possessing ancestor, for example, I need not elide its agency since that

was the force that attracted attention in the rst place. If the Malay women

discussed at the beginning of this introduction are approached as instru-

mental agencies for the hantu, the hantu preserves its pounce. In Chapter

I develop this concept in detail and relate it to arguments regarding nonvol-

untaristic accounts of agency in the work of Judith Butler, Elizabeth Grosz,

and Pheng Cheah.

The contemporary record of possession is largely represented by ex-

amples of third-world bodies, which continue to function as signiers amid

the triple axes of race, class, and gender. An important dimension of meth-

odology, therefore, is to approach these representations informed by postco-

lonial and feminist theories of the roles that women of color have played in

the imagination of modern subjectivity. In her important theorizations of

woman, native, other, Trinh T. Min-ha suggests that representations of

third-world women ll a deep-seated need in the imagination of self and

other: Third World, therefore, belongs to a category apart, a special one

that is meant to be both complimentary and complementary, for First and

Second went out of fashion, leaving a serious Lack behind to be lled.

10

If

possessed women are studied as members of the anachronistic space, our

fascination with them serves to ll the lack without acknowledging this dy-

namic. Many possession studies are premised upon the necessity of under-

standing possession, thereby masking the desire to be proximate to the pos-

sessed body. By shifting our approach, we acknowledge the desire and look

to these representations as resources for expanding the horizons for theoriz-

ing subjectivity.

Possessed women have been subjected to the scrutiny of the natural and

human sciences, with psychological, sociological, even biochemical inter-

Introduction

pretations being oered to explain possession in the historical past as well

as contemporary possession traditions. In revisiting these representations

the problem with which I am concerned is how the agency of possessed

women has been constructed in those representations. Possessed women

have been interpreted by scholars who were unable to locate, photograph,

weigh, or otherwise authenticate with empirical data the possessing ances-

tors, deities, or spirits. Consequently, these forces have been translated

according to prevalent academic models of religious subjectivity, which at-

tribute the force and vivacity of the possession to the beliefs of the people

being studied, beliefs that the scholar does not share. Or, more problemati-

cally, the ancestors, deities, or spirits are interpreted as psychosis, the physi-

ological eects of drum rhythms, or subconsciously employed guises used

by powerless people to acquire power that the scholar identies as real

power in contrast to religious power, such as economic gain or gains in social

status. Charles Long has described the historical trajectory that has pro-

duced the desire to translate other peoples religions according to Western

paradigms and has identied this problem as signifying: There is a com-

plex relationship between the meaning and nature of religion as a subject of

academic study and the reality of the peoples and cultures who were con-

quered and colonized during this same period. . . . [The reformist structure

of the Enlightenment] paved the ground for historical evolutionary think-

ing, racial theories, and forms of color symbolism that made the economic

and military conquest of various cultures and peoples justiable and defen-

sible. In this movement both religion and cultures and peoples throughout

the world were created anew through academic disciplinary orientations

they were signied.

11

Signifying, according to this denition, is a description of the relation-

ship between an academic study on the one hand and the reality of the

people being studied on the other. To claim that the study of religion is

replete with signications is not an ontological critique of academics as rac-

ist or sexist. Instead, the term signication identies a representational issue

that poses a methodological challenge: How does one engage in the study

of religion, given that a scandalous relationship underlies our pursuit? The

dynamic Long identies is the very dynamic that underlies the representa-

tion of possessed bodies, which are treated as novel phenomena that the

scholar can create anew in a way that makes sense from the scholars per-

The Hammer and the Flute

spective. Translated representations of religious others carry within them

an element of power that aects, at the level of representation, both the

academic and the religious bodies the academic is studying. Inhering in the

mask of objective neutrality is the scholars power to make worlds. As the

scholar presents the real meaning of the possession, as the scholar translates

what the people say is happening, a devaluation is occurring. The self-

identifying notae of a possession tradition, for instance, are not considered

to be adequate or powerful descriptors. As Long states, There is of course

the element of power in this process of naming and objectication. . . . It

[power] is manifest in the intellectual operations that exhibit the ability of

the human mind to come to terms with that which is novel, and it is mani-

fest in the manner of passivity that is expressed in the process wherein the

active existential and self-identifying notae through which a people know

themselves is almost completely bypassed for the sake of the conceptual and

categorical forms of classication.

12

The dynamic that Long designates as signication has an eect on the

construction of agency for both parties. The scholar is constructed as an

active agent and the agency of the people being studied is violently erased,

their indigenous knowledge overridden by the imposition of interpretive

frameworks. To reiterate, this is a critique registered at the level of represen-

tation, not of ontology. To criticize representational dynamics is not to

suggest that scholars are ontologically empowering or disempowering the

people they studythis seems to be a major confusion in recent years.

13

Noting the dynamic of signication does not point the way to purer repre-

sentations, nor does it pave the road for empowering the people one studies.

Rather, Longs argument impels me to revisit the record of possession stud-

ies and to identify the representational issues at work in a way that subjects

modern categorizations to the meaning of intellectual desire in its contact

with the possessed body.

Real Possessions?

The issue of signication, as Long has identied it, is a formal issue regard-

ing the representation of religious others. The complexity of representing a

possession is, owing to several factors, unique. By limiting this study to ex-

amples of possession in which consciousness is overcome, the representa-

Introduction

tions of these women are always the product of a witness to the possession,

which means that representations of possessed bodies are the products of

many layers of interpretation. One is not able to return to an origin where

one might nd out what she really said or experienced; instead, she requires

the interpretations of her community in order to recount the event. To study

possession, therefore, is always to study representations of possession. T. K.

Oesterreich spoke to this problem in his study of possession:

The facilities for an analysis of possession are much inferior to those enjoyed by the

student of states of ecstasy. For these latter we possess a mass of sources, autobio-

graphical in the widest sense of the word. Autodescriptions of possession are, on the

contrary, extremely rare. . . . This poverty of autodescriptive narratives has a pro-

found psychological reason which springs from the very nature of possession. We are

to some extent dealing with states involving a more or less complete posterior amne-

sia, so that the majority of victims of possession are not in a condition to describe it.

It is therefore necessary a priori to avoid conning ourselves to autodescriptive

sources, and to regard this matter as one in which concessions must be made.

14

While we should be wary of the signiers at work in Oesterreichs text, the

point he makes remains relevantwe are dependent upon the representa-

tions of witnesses to possessions, and the nature of possession prevents us

from listening only to the words of the possessed. Michel de Certeau de-

scribes this quandary about representations of possessed women in respect

to the nuns of Loudun in seventeenth-century France:

Quite often the available sources (archives, manuscripts, etc.) oer, as the possessed

womans discourse, what is always spoken by someone other than the possessed.

In most cases these documents are notaries minutes, medical reports, theologians

opinions or consultations, witnesses depositions, or judges verdicts. From the de-

moniac woman there only appears the image that the author of such texts has of her,

in the mirror where he repeats his knowledge and where he takes her own position

through inverting and contradicting it. That the possessed womans speech is nothing

more than the words of her other, or that she can only have the discourse of her

judge, her doctor, the exorcist, or witnesses is hardly by chance. . . . But from the out-

set this situation excludes the possibility of tearing the possessed womans true voice

away from its alteration. On the surface of these texts her speech is doubly lost.

15

This problem becomes fruitful material for the analysis of signifying prac-

tices. All of the accounts from which I have drawn represent a speech that

The Hammer and the Flute

is doubly lost. The possessed womans voice is overcome by an ancestor,

deity, or spirit that speaks through her. As a problem of representation, the

discourse of possession contains all of the potential for alterity, elision, cen-

sorship, sponsorship, suspicion, and transgression that has excited critical

theory. There is no such thing as an unaltered account of her possession.

How one reads that alteration, then, is the key hermeneutic for interpreting

her agency.

For this reason, I have chosen to stretch the boundaries of resources from

which examples of possessed women are drawn in Part . Chapter exam-

ines the possessions in Malaysia referred to at the beginning of this intro-

duction. Chapter examines possessions in Zimbabwe, and Chapter ex-

amines two plays in which a possessed woman is a central gure: Euripides

Bacchae and S. Y. Anskys The Dybbuk. It might seem awkward to move from

proposing an alternative interpretation of an ethnographic account of pos-

session to proposing an alternative interpretation of a play. The argument

for doing so is threefold. First of all, as stated above, there is no representa-

tion of a possession that is not an interpretation. In the case of the plays I

have chosen, they are accurate in their description of the religious lives of

women in ancient Greece and in Hasidic eastern Europe and in fact are

drawn from by other scholars as providing evidence about womens religious

lives because resources for such study are scarce. That is to say that these

interpretations of possession are considered to be historically accurate rep-

resentations. When studying womens religious lives, scholars are always

challenged to draw from and interpret judiciously information drawn from

nontraditional resources. The classicist Marilyn Skinner describes the nec-

essary strategy for extrapolating information about womens lives as con-

trolled inference.

16

Data used for piecing together womens religious lives

is almost always data received from male discourses and must be approached

with this power dierential in mind. For instance, historians of womens

lives draw from tombstones, legal and medical records, and the arts, all of

which exist according to the privileges of a dominant, patriarchal discourse.

Cultural representations of women (such as plays, artwork, and pottery)

must be approached carefully, since they record the artists aesthetic record,

and legal and medical records must also be approached carefully, as they

might have little relationship to the practices in which women engaged.

From this perspective, plays can be seen to carry vital information, which,

Introduction

if approached with controlled inference, provides valuable interpretations

about possession in these cultures.

The second reason to study these plays is that womens power is a central

theme in each of them, suggesting that the playwrights were purposefully

reecting on womens religious lives in relation to the systems of power in

which the women lived. Thus the playwrights provide us with critical in-

sights into womens lives, making their ctional accounts more signicant

than the dismissals of womens lives that mark the absences in traditional

historical accounts of these periods.

The third reason is that the performative power of possessions is itself a

major area of analysis, and the plays can be read as metaemployments of

the performative power of the possessed woman. These plays have raised

controversy, received signicant critical attention, and been hailed as mas-

terpieces. My argument is that these playwrights capitalized upon the per-

formative power of possession, albeit rehearsed and captured on a stage, to

great eect. To study a masterpiece with a possessed woman in it is to study

a powerful interpretation of a possessed woman; The Bacchae and The Dyb-

buk both provide excellent examples whereby the representation of a posses-

sion has been orchestrated in order to tap into the power of the possessed

woman. Analyzing these plays allows one to engage critically with two

dierent elds of scholarship. The rst consists of artistic interpreters of

the plays who, I argue, have been unable to appreciate the role of the pos-

sessed woman in the play because they associate her with a kind of hysterical

neediness rather than recognizing her role as a driving force in the play. The

second consists of ethnographers who have employed performance theory

to interpret the dynamic of possessions. I argue that most applications of

performance theory presuppose that an actor is performing, just as the

actors in the play are performing. This theoretical approach to possessions

assumes that an actor is acting rather than that a woman is being played by

an ancestor, deity, or spirit to an audience, and again we have returned to

the problem that undergirds most scholarship on possession: Scholars are

unable to think about agency outside of the bounds of a conscious agent. In

contrast, these playwrights have not created characters who act out acting

Euripides and Ansky are clear in their use of the possessed woman as a

character that the power of the possessed woman is her alterity rather than

her individual strength as a performer.

The Hammer and the Flute

Many kinds of representations are drawn from in the book, from colonial

photographs to historical documents to ethnographies to dramatic texts.

What these representations share is that they indicate a politics of rela-

tionality between the author of the account and the woman or women de-

scribed. What I am proposing, then, is an analysis that is concerned with

the politics of relationality in reading and evaluating representations of pos-

sessed women. I adapt this phrase from De Certeaus argument that texts

written by mystics are not logical statements nor are they factual accounts:

These stories depict relations. They do not treat statements (as would a logic) or facts

(as in a historiography). They narrate relational formalities. They are accounts of

transfers, or of transformational operations, within enunciative contracts. Thus, for

example, there is a missing and seductive otherness of the idiot woman or idiot man

only in relation to the wise man. The story, a theoretic ction, sketches enunciative

models (challenge, summons, duel, seduction, change of position, etc.) and not con-

tent (true statements, meanings, data, etc.). What is essential to it, therefore, is that

which, in the form of coups, transforms the relationships between subjects within

the system of meanings or of factsas if, in speech, one were to consider only the

changes of place among the speakers and not the semantic or economic orders from

which these illocutionary exchanges nevertheless receive a eld and a vocabulary for

their operations.

17

Following this line of interpretation I look at ethnography, historiogra-

phy, and dramatic texts as accounts of possession that explain a transfer or

transformational operation within the enunciative contracts of the dis-

courses in which they are recorded. As accounts of possession they indicate

and tally the relations of bodies. They record challenges, seductions, and

duels rather than true statements. Whether it is an ethnographer or a play-

wright who is representing the possessed woman, my analysis is of the rela-

tional formalities by which the representations are narrated. What becomes

fascinating if accounts of possession from various genres are understood to

narrate relational formalities is the central role possessed women play as

sites of exchange between race, class, and gender distinctions. Feminist the-

ory has long pondered the role of women within male economiesthe zero

sum upon which patriarchal economies turn. The possessed woman func-

tions as an altered marker in highly charged exchanges. Accounts of posses-

sion often occur at moments of cultural crises, where worlds of meaning are

being exchanged for new paradigms, or at moments of change and exchange

Introduction

in a womans life, especially marriage. Such a highly overdetermined reli-

gious body merits rigorous analysis.

Given the doubly lost nature of a possessed womans speech, any account

of a possession depicts relationships between the authors and the possessed

women they describe more so than it depicts the real possession. Euripi-

des deployment of maenads in his play is as much a resource with which a

scholar can employ a method of controlled inference in learning about the

religious lives of women in Greek antiquity as is Anskys deployment of a

young possessed Jewish woman (whose character was drawn from the ex-

tensive ethnographic expeditions Ansky led through the Pale of Settlement

as described in Chapter ), as is Ongs materialist analysis of the contempo-

rary Malaysian possessions. Although ethnographers and playwrights are

working within entirely dierent parameters for including or excluding in-

formation, neither can claim to be writing a factual account of a posses-

sionthey are writing accounts that depict the relationship between a

woman, an unknowable agency, and the community that responds to the

woman. What would a factual account of a possession be? How would

one know?

Outline of the Text

The book proceeds in two parts. Part traces the history of possession stud-

ies, elucidates contemporary arguments about agency, and proposes the

concept of instrumental agency. Chapter , Signifying Possession, pres-

ents the general shape and history of possession studies and identies the

awkward formal relationship that has been constructed as scholars have es-

tablished their academic approaches to possessed bodies in the past century.

Chapter , Reorienting Possession, outlines the important work of Talal

Asad and Catherine Bell, who have reinvigorated religious studies in their

respective analyses of the relationship of religious bodies to power. When

such bodies are related to power rather than depicted as bodies molded by

belief, the representation of agency is put on new ground. Chapter is a

constructive chapter that introduces the concept of instrumental agency,

a concept that provides a discursive space for the agency of the possessing

ancestors, deities, or spirits to be taken seriously as a constitutive element

in the subjectivity of the possessed body and therefore a constitutive ele-

The Hammer and the Flute

ment of its agency. Functioning within the discourse of philosophical theol-

ogy, the concept of instrumental agency does not claim knowledge of the

possessing ancestors, deities, or spirits. It does, however, allow one to take

seriously the self-identifying notae of possession traditions, which identify

womens status as utelike and hammerlike instruments for ancestors, dei-

ties, or spirits.

In Part : I revisit four episodes of possession following the themes of

work, war, and play(s). These thematic backdrops emphasize the relation-

ship of womens religious lives to their negotiations with power. The previ-

ous analyses of these possessions interpret the symbolic meaning of the pos-

sessions so that possessed women who are found in places of work, war, and

play have been described as agents who are wielding symbolism as a guise

for getting work done, ghting battles, or attracting attention to themselves.

While previous analyses of these case studies have maintained the anachro-

nistic space of the possessed woman, I demonstrate how dierently we g-

ure in relationship to the possessed woman when we investigate her instru-

mental agency.

Chapter , Work, examines the possessions that happened on the shop

oors of technologically sophisticated, multinational manufacturing plants

in Malaysia. The crux of the problem in evaluating the possessions is that

they occur at a site of oppressive labor conditions. Religious bodies are often

perceived from the contemporary perspective to be oppressed by religious

belief so that the evaluation of the possession occurring at a worksite entails

a complex dynamic. The oppressive working conditions are viewed as real

oppression, while the possession is viewed as a symbolic reaction to the real

oppression, and the ancestors are . . . psychic metaphors of real struggle?

After critically studying representations of these possessions, I propose that

the Malay women were acting as instrumental agencies for the resacraliza-

tion and reterritorialization of spaces that are recognizably sacred to the

Malay.

Chapter , War, revisits representations of the role that the Nehanda

mhondoro (Shona spirit mediums) played during the rst chimurenga and sec-

ond chimurenga (revolutionary war) in Zimbabwe. During these wars, indig-

enous Africans fought against the colonial governments of Cecil Rhodes

(r8os, rst chimurenga) and Ian Smith (roor;os, second chimurenga).

Unlike the Malay women, who have been depicted predominantly as victims

Introduction

of oppression, the Nehanda mhondoro have been depicted as heroines and

have risen to the status of national symbols. Reading them as instrumental

agencies for their ancestors, the guardians of the land, produces an alterna-

tive evaluation of their power.

Chapter examines the representations of possessed women in two plays:

Euripides Bacchae and S. Y. Anskys Dybbuk. I focus specically on how the

playwrights represent the possessed womans agency and discuss how the

playwrights have employed the instrumental agency of the possessed woman

to great eect and great critical notice. Both plays have moved and troubled

their audiences, in part owing to the ambivalent power that a possessed

woman exercises on stage as a dramatic force that crosses traditional gender

lines. Both plays have proved problematic for critics, in part because of the

dramatic eects created by the volatile body of a woman who is wielded

by forces that lead to tragic conclusions. I conclude the chapter by briey

examining the relationship between performance theories of possessions

and performances of possession, arguing that what most performance theo-

ries of possession do is to suggest that conscious actors are performing, that

is to say, manipulating their audiences. An alternative to this model of per-

formance theory is found in the work of Ann G. Gold; the underlying

dierence between Golds theory and others is which models of subjectivity

and agency they assume. Using instrumental agency as the model of subjec-

tivity, one can allow for the play of possession, a play that works, rather

than locating the performative power of possession as belonging to an actor

who is manipulating an audience.

I approach the topic of possession as a feminist philosopher and historian

of religions informed by postcolonial perspectives to argue against previous

interpretations and for an analysis of the agency of a woman who is not

where she is speaking. As with Chilla Bulbecks Re-Orienting Western Femi-

nisms and Richard Kings Religion and Orientalism, my argument is aimed at

usthose who are trained in the Western academic tradition and who

are constrained by assumptions and models of subjectivity of which we are

unaware and which can hinder our ability to recognize our relationship to

the religious others who attract our intellectual desires.

18

We have ap-

proached possession as though it existed in a museum and did not have any

real power to subject us to its meanings, masking our desire to watch and

record while constructing ourselves as impervious to the belief structures

The Hammer and the Flute

that make possession possible for our others. Building on new developments

in the study of possession and of religious bodies we can now understand

ourselves as the historical and global minority, hindered by structures of

which we are unaware as we are drawn to encounter the otherness of other

peoples religions and other womens forms of power. From each cultural

and historical setting, these ambivalently powerful possessed women have

attracted the attention of authors, and it is toward providing a more ade-

quate framework for interpreting their agency that I now turn.

Part 1 Reorienting Possession in Theory

In religious studies questions have been raised about how

scholarly representations of religious others have served to

build a hierarchical sense of an us, enlightened, reasonable

individuals, in contrast to a them, backward and primitive

communities. Bodies that are possessed by ancestors, spirits,

or deities have often been approached as backward or primi-

tive bodies at worst, or as novel cultural or ethnic bodies. The

underlying problem with most approaches to possession is

that the scholar sees the body as religiously motivated, as a

body that has beliefs, which are not really real. If we are to

take Charles Longs argument seriously and examine how the

study of possession has signied its others, we are faced with

a very interesting intellectual problem. If we concern our-

selves with the self-identifying notae of possession traditions,

that is, if the scholar attempts to engage with rather than

elide the claims being made regarding the power of ancestors,

deities, and spirits to possess bodies, how might one approach

the interpretation and evaluation of possessed bodies?