Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Turp

Turp

Uploaded by

Coleen Comelle Huerto0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

348 views23 pagesTransurethral Resection of the Prostate (TURP) is a common surgery to treat an enlarged prostate by removing prostate tissue blocking urine flow. During TURP, an instrument is inserted through the urethra to cut and remove prostate tissue using an electric cutting tool. The procedure usually takes an hour under general or spinal anesthesia, with most patients staying in the hospital 1-2 days to recover. TURP provides effective relief of urinary symptoms for 7-10 out of 10 men who have the surgery.

Original Description:

case

Original Title

turp

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentTransurethral Resection of the Prostate (TURP) is a common surgery to treat an enlarged prostate by removing prostate tissue blocking urine flow. During TURP, an instrument is inserted through the urethra to cut and remove prostate tissue using an electric cutting tool. The procedure usually takes an hour under general or spinal anesthesia, with most patients staying in the hospital 1-2 days to recover. TURP provides effective relief of urinary symptoms for 7-10 out of 10 men who have the surgery.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Download as docx, pdf, or txt

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

348 views23 pagesTurp

Turp

Uploaded by

Coleen Comelle HuertoTransurethral Resection of the Prostate (TURP) is a common surgery to treat an enlarged prostate by removing prostate tissue blocking urine flow. During TURP, an instrument is inserted through the urethra to cut and remove prostate tissue using an electric cutting tool. The procedure usually takes an hour under general or spinal anesthesia, with most patients staying in the hospital 1-2 days to recover. TURP provides effective relief of urinary symptoms for 7-10 out of 10 men who have the surgery.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Download as docx, pdf, or txt

You are on page 1of 23

Transurethral Resection of the Prostate (TURP) for Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia

During transurethral resection of the prostate (TURP), an instrument is inserted up

the urethra to remove the section of the prostate that is blocking urine flow.

TURP usually requires a stay in the hospital. It is done using a general or spinal

anesthetic.

What To Expect After Surgery

The hospital stay after TURP is commonly 1 to 2 days.

Following surgery, a catheter is used to remove urine and blood or blood clotsin

the bladder that may result from the procedure. When the urine is free of significant

bleeding or blood clots, the catheter can be removed and you can go home.

Strenuous activity, constipation, and sexual activity should be avoided for about 4 to 6

weeks. Symptoms such as frequent urination will continue for a while because of

irritation and inflammation caused by the surgery. But they should ease during the first 6

weeks.

Why It Is Done

Your doctor may recommend TURP if symptoms caused by benign prostatic

hyperplasia (BPH) have not improved in response to home treatment and medicines.

How Well It Works

For men who have moderate to severe symptoms of prostate enlargement, TURP is

more effective than watchful waiting in relieving urinary symptoms. Studies have found

that:

Men who had TURP had a lower symptom score compared with those who used

watchful waiting.

1

Symptoms get better for 7 to 10 out of 10 men who have the surgery.

2

Men experience about an 85% improvement in their American Urological Association

(AUA) symptom index scores.

2

For example, if you had a score of 25, after this surgery

it might be at about 4. Men who are very bothered by their symptoms are most likely to

notice great improvement in their symptoms after TURP. Men who are not very

bothered by their symptoms are less likely to notice a big change.

Risks

The risks of transurethral resection of the prostate (TURP) include problems with sexual

performance, incontinence, and problems from surgery.

Problems with sexual performance

Ejaculation into the bladder (retrograde ejaculation) is very common. It occurs in about

25 to 99 men out of 100.

2

This does not affect sexual function.

Men who have TURP appear to have no greater risk for erection problems than men

who do not have surgery.

3

For men who do have trouble getting an erection, medicine

can help.

Loss of ability to control urine flow (incontinence)

A small number of men (about 1 out of 100) say they are completely unable to hold

back their urine after the surgery.

2

But some experts say that men who have TURP

appear to have no greater risk for incontinence than men who do not have surgery.

3

Some men find that they can still hold in their urine after the surgery, but they tend to

leak or dribble.

Problems related to having surgery

About 5 out of 100 men have severe bleeding and need a blood transfusion.

4

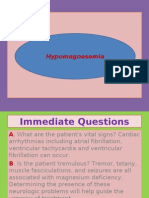

Transurethral resection (TUR) syndrome occurs in about 2 out of 100 men who have

TURP.

2

This syndrome occurs when the body absorbs too much of the fluid used to

wash the area around the prostate while prostate tissue is being removed. The

symptoms of TUR syndrome include mental confusion, nausea, vomiting, high blood

pressure, slowed heartbeat, and visual disturbances. TUR syndrome is temporary

(usually lasting only the first 6 hours after surgery) and is treated with medicine that

removes excess water from the body (diuretic).

About 2 men out of 100 need to have another operation after 3 years. And about 8 men

out of 100 need to have another operation after 5 years.

2

Repeat surgery because of a complication of the surgery is needed less than 10% of

the time.

2

What To Think About

TUR syndrome doesn't happen when TURP is done using a bipolar tool (resectoscope)

compared to a monopolar resectoscope. You may want to ask your doctor which kind of

tool he or she uses.

Surgery usually is not required to treat BPH, although some men may choose it

because their symptoms bother them so much. Choosing surgery depends mostly on

your preferences and comfort with the idea of having surgery. Things to think about

include your expectation of the results of the surgery, the severity of your symptoms,

and the possibility of having complications from the surgery.

Men who have severe symptoms often have great improvement in quality of life

following surgery. Men whose symptoms are mild may find that surgery does not greatly

improve quality of life. Men with only mild symptoms may want to think carefully before

deciding to have surgery to treat BPH.

Transurethral resection of the prostate

Share on facebookShare on twitterBookmark & SharePrinter-friendly version

Transurethral resection of the prostate (TURP) is surgery to remove the inside part of

the prostate gland in order to treat an enlarged prostate.

Related topics include:

Benign prostatic hyperlasia

Prostate resection - minimally invasive

Simple prostatectomy

Description

The surgery takes about 1 hour.

You will be given medicine before surgery so you don't feel pain. You may get one of

the following:

General anesthesia: You are asleep and pain-free

Spinal anesthesia: You are awake, but relaxed and pain-free

The surgeon will insert a scope through the tube that carries urine from your bladder out

of the penis. This tube is called the urethra. A special cutting tool is placed through the

scope. It is used to remove the inside part of your prostate gland using electricity.

Why the Procedure is Performed

Your doctor may recommend this surgery if you have benign prostatic hyperplasia

(BPH). The prostate gland often grows larger as men get older. The larger prostate play

causes problems with urinating. Removing part of the prostate gland can often make

these symptoms better.

Prostate removal may be recommended if you have:

Difficulty emptying your bladder

Frequent urinary tract infections

Bleeding from the prostate

Bladder stones with prostate enlargement

Extremely slow urination

Damage to the kidneys

Before you have surgery, your doctor will suggest you make changes in how you eat or

drink. You may also be asked to try taking medicine. Your prostate may need to be

removed if these steps do not help. TURP is one of the most common type of prostate

surgery. Other procedures are also available.

Your doctor will consider the following when deciding on the type of surgery:

Size of your prostate gland

Your health

What type of surgery you may want

Risks

Risks for any surgery are:

Blood clots in the legs that may travel to the lungs

Breathing problems

Infection, including in the surgical wound, lungs (pneumonia), or bladder or

kidney

Blood loss

Heart attack or stroke during surgery

Reactions to medications

Additional risks are:

Problems with urine control

Loss of sperm fertility

Erection problems

Passing the semen into the bladder instead of out through the urethra (retrograde

ejaculation)

Urethral stricture (tightening of the urinary outlet from scar tissue)

Transurethral resection (TUR) syndrome (water buildup during surgery)

Damage to internal organs and structures

Before the Procedure

You will have many visits with your doctor and tests before your surgery. Your visit will

include:

Complete physical exam

Treating and controlling diabetes, high blood pressure, heart or lung problems,

and other conditions

If you are a smoker, you should stop several weeks before the surgery. Your doctor or

nurse can give you tips on how to do this.

Always tell your doctor or nurse what drugs, vitamins, and other supplements you are

taking, even ones you bought without a prescription.

During the weeks before your surgery:

You may be asked to stop taking medicines that can thin your blood, such as

aspirin, ibuprofen (Advil, Motrin), naproxen (Aleve, Naprosyn), vitamin E,

clopidogrel (Plavix), warfarin (Coumadin), and others.

Ask your doctor which drugs you should still take on the day of your surgery.

On the day of your surgery:

Do not eat or drink anything after midnight the night before your surgery.

Take the drugs your doctor told you to take with a small sip of water.

Your doctor or nurse will tell you when to arrive at the hospital.

After the Procedure

You will stay in the hospital for 1 to 3 days.

After surgery, you will have a small tube, called a Foley catheter, in your bladder to

remove urine. The urine will look bloody at first. The blood goes away within a few days

in most cases. Blood can also seep around the catheter. A special solution may be used

to flush out the catheter and keep it from getting clogged with blood. The catheter will be

removed within 1 to 3 days for most people

You will be able to go back to eating a normal diet right away.

You will need to stay in bed until the next morning. You will be asked to move around as

much as possible after that point.

Your health care team will:

Help you change positions in bed

Teach you exercises to keep blood flowing

Teach you how to perform coughing and deep breathing techniques. You should

do these every 3 to 4 hours.

Tell you how to care for yourself after your procedure.

You may need to wear tight stockings and use a breathing device to keep your lungs

clear.

You may be given medication to relieve bladder spasms.

Outlook (Prognosis)

TURP relieves symptoms of an enlarged prostate most of the time. You may have

burning with urination, blood in your urine, urinate often, and need to urgently urinate.

Background

For most of the 20th century, from 1909 until the late 1990s, the premier treatment for

symptomatic benign prostatic hypertrophy (BPH) was transurethral resection of the

prostate (TURP). TURP was the first successful, minimally invasive surgical procedure

of the modern era. To this day, it remains the criterion standard therapy for obstructive

prostatic hypertrophy and is both the surgical treatment of choice and the standard of

care when other methods fail.

Since the advent of medical therapy for symptomatic prostatic hypertrophy with 5-alpha

reductase inhibitors and alpha-adrenergic blockers, the need for immediate surgical

intervention in symptomatic prostatic obstruction has been reduced substantially.

However, alpha-blockers do not modify prostate growth, and even the use of prostatic

growth inhibitors such as finasteride or dutasteride often fails to prevent recurrent

urinary symptoms of BPH and retention. In the past, these patients would almost

certainly have undergone TURP years earlier.

The criteria for performing TURP surgery are now more stringent than before. In

general, TURP surgery is reserved for patients with symptomatic BPH who have acute,

recurrent, or chronic urinary retention; in whom medical management and less-invasive

prostatic surgical procedures failed; who have prostates of an unusual size or shape

(eg, a markedly enlarged median lobe, significant intravesical prostatic encroachment);

who have azotemia or renal insufficiency due to prostatic obstruction; or who have the

most severe symptoms of prostatism.

Less common uses of TURP include intractable prostatitis or for tissue sampling when

standard biopsy techniques cannot be used.

The relative frequency of TURP compared to open prostatectomy in surgical patients

varies from country to country. In 1990, the relative frequency rate of TURPs in surgical

patients with BPH in the United States was 97%, with similar rates in Denmark and

Sweden. The lowest rates of TURP were noted in Japan (70%) and France (69%).

The average age of patients currently undergoing TURP is approximately 69 years, and

the average amount of prostate tissue resected is 22 g. Risk factors associated with

increased morbidity include prostate glands larger than 45 g, operative time longer than

90 minutes, and acute urinary retention as the presenting symptom. The 5-year risk rate

for a reoperation following TURP is approximately 5%. Overall mortality rates following

TURP by a skilled surgeon are virtually 0%.

African Americans more typically present for TURP surgery with urinary retention or

urinary infections and have a higher incidence of preexisting medical problems

compared to the general population. According to Kang et al (2004), reports from the

Prostate, Lung, Colorectal, and Ovarian (PLCO) cancer screening trial indicate that

Asian and Asian American men have the lowest overall risk of clinical BPH and eventual

TURP.

[1]

Go to Prostate Cancer, Prostate-Specific Antigen, and Benign Prostatic Hypertrophy for

complete information on these topics.

Indications

According to the Agency for Health Care Policy and Research guidelines for the

diagnosis and treatment of BPH and the recommendations of the Second International

Consultation on Benign Prostatic Hypertrophy, the absolute indications for primary

surgical management of BPH are as follows:

[2]

Refractory urinary retention

Recurrent urinary tract infections due to prostatic hypertrophy

Recurrent gross hematuria

Renal insufficiency secondary to bladder outlet obstruction

Bladder calculi

Permanently damaged or weakened bladders

Large bladder diverticula that do not empty well secondary to an enlarged prostate

Most men who present for surgical correction of their urinary outlet obstruction are those

in whom medical therapy or alternative procedures have failed or are inappropriate for

some reason. In general, patients with moderate-to-severe lower urinary tract

obstructive symptoms (American Urological Association [AUA] symptom index >8) who

have not responded to alpha-adrenergic blockers and/or 5-alpha reductase inhibitors

are also candidates for surgical intervention.

A study by Blanchard et al showed that patients in whom alpha-blocker therapy is

ineffective or those in whom it has failed tend to have poorer outcomes after TURP than

men who proceed directly to a transurethral resection.

[3]

This is presumably from

preoperative bladder damage and other risk factors that affect voiding rather than the

size of the prostate. Operating time and weight of resected tissue have been

documented as the same between the 2 groups; therefore, prostatic size alone does not

account for the difference in outcomes.

Although persistent, progressive, or bothersome symptoms of urinary obstruction due to

prostatic hypertrophy that are refractory to medical therapy constitute the most common

indication for TURP, 70% of men undergoing the procedure have multiple indications.

Patients with prostates larger than 45 g, who present with acute urinary retention, or

who require operating times in excess of 90 minutes, are at increased risk for

postoperative complications.

Surgical treatment of BPH is also indicated in cases of renal failure or insufficiency

secondary to prostatic obstruction. Catheter drainage is usually recommended in such

cases until the renal failure resolves. As many as 10% of men with BPH present with

some degree of renal insufficiency.

Contraindications

The only absolute indication for an open prostatectomy over a TURP is the need for an

additional open procedure on the bladder that must be performed at the same time as

the prostatectomy. Such indications include open surgical resection of a large bladder

diverticulum or removal of a bladder stone that cannot be easily fragmented by

intracorporeal lithotripsy.

A relative indication for the selection of an open prostate surgery over a TURP is

generally based on prostatic volume and the ability of the surgeon to complete the

TURP in less than 90 minutes of actual operating time (although < 60 min is considered

optimal).

In general, open prostatectomy can be justified in a patient with a prostate of 45 g or

larger, but this is totally dependent on the skill and experience of the endoscopic

urological surgeon. Most experienced urologists use a prostatic volume of 60-100 g as

the upper limit amenable to endoscopic removal, but some highly skilled resectionists

are capable of safely treating a 200-g prostate with TURP in less than 90 minutes.

Declining Frequency of TURP

The new availability of reasonable alternative medical and surgical treatment options

means that TURP, once one of the most commonly practiced urological procedures, is

now performed much less frequently. In 1962, TURP operations accounted for more

than 50% of all major surgical procedures performed by urologists in the United States.

By 1986, this had declined to 38%.

The 1985 Veterans Administration Normative Aging Study estimated the lifetime

probability of surgical intervention for prostatic enlargement at 29%, and the 1986

National Health Survey estimated that 350,000 patients in the Medicare age group had

a TURP that year, compared to fewer than 200,000 in that same age group by 1998.

These numbers should be considered within the context that the median age of the

typical patient is rising (the number of older men with BPH-related symptoms in the

United States is expected to increase from 5 million to 9 million persons by 2025), the

size of the average resected prostate gland is increasing, and the typical patient has

more comorbidities and is generally less healthy than surgical patients of the past.

A comprehensive review of transurethral prostatectomy in the Medicare beneficiaries by

Wasson et al compared a national sample from 1991-1997 to a similar group for the

period 1984-1990 found that the more recent group demonstrated a substantial decline

in the number of TURP surgeries: 50% for white men and 40% for black

men.

[4]

Compared to the peak period of TURP use in the 1980s, a higher proportion of

the men undergoing the procedure were older in the more recent period, with 53% aged

75 years or older.

Another factor that must be considered when evaluating the general decline in the

number of TURP procedures performed is the significant reduction in financial

reimbursement to urologists for TURP surgeries in the United States.

Physician reimbursement from Medicare for a TURP has dropped from a high of $2000-

$3000 in the past to approximately $650 today, with a 90-day global period that covers

all postoperative care by the surgeon for 3 months. In many instances, performing a

TURP is simply not profitable for the urologist when office overhead, billing and

malpractice costs are considered, especially when complications occur.

Alternative surgical procedures, such as microwave therapy and prostatic laser surgery,

are reimbursed at much higher levels, even though they may not be as durable or

effective. This creates a strong financial disincentive for urologists to perform TURP

procedures, except when no reasonable alternatives exist. A 2002 article by Donnell

examined the history of Medicare policies and the effect of changes in Medicare

reimbursement on TURP.

[5]

In a large Canadian series reported by Borth et al, the number of TURP procedures

dropped by 60% between 1988 and 1998, presumably because of medical therapy,

despite an increase of 16% in the male population older than 50 years.

[6]

While the

number of patients presenting with urinary retention was significantly higher in the 1998

group than in the 1988 cohort (55% vs 23%), no significant difference was noted in their

average age, medical comorbidities, operative parameters, average size of prostate

tissue resected, or complication rates.

Anatomic Considerations

The prostate is divided into 3 zones: peripheral, central, and transition. The peripheral

zone is the largest of the zones, encompassing approximately 75% of the total prostate

glandular tissue in men without BPH. Most prostate cancers originate in the peripheral

zone. It is located posteriorly and extends laterally on either side of the urethra.

The central zone is smaller and extends primarily around the ejaculatory ducts. It differs

from the peripheral zone primarily in cytologic details and architecture.

The transition zone is usually the smallest of the 3: it occupies only 5% of the prostate

volume in men younger than 30 years. This is the zone thought to be the origin of BPH.

The transition zone consists of two separate lobes on either side of the urethra and

usually involves a small grouping of ductal tissue near the central portion of the prostatic

urethra near the internal sphincter.

As the transition zone expands, it can comprise up to 95% of the prostate volume,

compressing the other zones. Intraoperatively, the 2 enlarged lobes of the transition

zone can be seen obstructing the prostatic urethra on either side. Thus, the term lateral

lobes is often used intraoperatively for this tissue to distinguish it from any hyperplastic

periurethral gland tissue.

The periurethral glands are less commonly involved with BPH, but when they do

become enlarged, they can form what is termed a median lobe, which appears as a

teardrop-shaped midline structure at the posterior bladder neck. This can ball-valve into

the urethra, creating severe obstructive voiding symptoms. Any significant intravesical

extension of prostatic tissue can act as a valve when the detrusor pressure increases

and presses this tissue against the bladder neck or across the outlet to the urethra,

creating a functional obstruction (see the image below).

Benign prostatic hypertrophy of the lateral and median lobes. Various

configurations.

In some earlier jargon, the transition zone and periurethral region were called the

central gland or inner gland, and the peripheral and central zones were called the outer

gland. This terminology should be avoided both because it is vague and because it

creates confusion with the now-standard anatomical label of the central zone.

Prostatic calculi are formed from calcification of the corpora amylacea and precipitation

of prostatic secretions. They occur between the transition zone and the compressed

peripheral zone; in fact, they can be used as a marker for this border. Prostatic calculi

are generally composed of calcium phosphate and are not considered clinically

significant. Chemical analysis is unnecessary.

Although prostatic calculi may arise spontaneously, they also may be formed in

response to an inflammatory reaction or as a consequence of another pathological

process that produces acinar obstruction. Some practitioners believe that calcifications

that form in response to bacterial prostatitis may harbor bacteria that periodically

flourish, causing recurrent prostatitis. Proponents of this theory advocate TURP to

liberalize these calcifications as a treatment for recurrent prostatitis.

If a channel is opened during surgery that allows these calculi to be expressed, they

often flow out by themselves if the opening is large enough. They can be milked out by

using the end of the cutting loop without current to gently press around the opening

where the prostatic stones are seen and can be pushed into the opened prostatic fossa.

They can be rinsed into the bladder and evacuated with the rest of the resected

prostatic chips.

The prostate is thinnest and most narrow anteriorly (the 12-oclock position when

viewed through a cystoscope). Care should be taken when operating in this area to

avoid perforating the prostatic capsule, especially if this portion of the prostate is

resected early in the operation. Abundant venous blood vessels are located in the area

just anterior to the prostatic capsule, which can cause significant bleeding that cannot

be easily controlled if the vessels are damaged during resection.

The external sphincter muscle tends to be slightly tilted, with the most proximal portion

located anteriorly, opposite the verumontanum. The external sphincter can be identified

cystoscopically by its wrinkling and constricting action as the resectoscope is withdrawn.

Upon reinsertion, the superficial mucosa in front of the telescope tends to bunch up.

This is because the external sphincter muscle is imbedded within the urogenital

diaphragm, which is relatively fixed in position, while the prostate has some limited

mobility.

The verumontanum is the single most important anatomical landmark in TURP (see the

image below). It is a midline structure located on the floor of the distal prostatic urethra

just proximal to the external sphincter muscle. It appears as a small, rounded hump that

is best seen when withdrawing the telescope through the prostate while visualizing the

prostatic floor at the 6-oclock position.

Basic anatomy of the prostate, sagittal section.

The orifices to the ejaculatory ducts emerge in the verumontanum (see the first image

below). Its importance lies in its position immediately proximal to the external sphincter

muscle (see the second image below), which allows it to be used as the distal landmark

for prostate resection. The precise distance between the verumontanum and the

external sphincter demonstrates some slight individual variation and should be verified

visually before starting the resection and periodically during the surgery.

Anatomy of the prostate and bladder, posterior view. Anatomy of the prostate

and urethra.

The proximity of the ureteral orifices to the cephalad margin of the hypertrophied

prostate varies, particularly in patients with an enlarged median lobe. This distance

should be frequently assessed throughout surgery.

The vascular anatomy of the prostate was accurately described in detail by Rubin

Flocks in 1937.

[7]

The blood supply of the prostate comes primarily from branches of the

inferior vesical artery, which is a branch of the internal iliac artery (see the image

below).

Blood supply to the prostate.

When the inferior vesical artery reaches the prostate just at the vesicoprostatic border, it

branches into 2 groups of arteries (see the image below). One penetrating group

passes directly into the prostate toward the interior of the bladder neck. Upon reaching

the prostatic interior near the urethra, most of these branches turn distally and parallel

the prostatic urethra, while others supply the median lobe.

Blood supply to the prostate. Note the two main branches: urethral and capsular.

Vessels that parallel the prostatic urethra supply most of the blood to the hypertrophied

lateral lobes. The second large group of arteries follows the exterior of the prostatic

capsule posterolaterally, periodically giving rise to perforating vessels, and supplies the

area around the verumontanum.

See Prostate Anatomy and Male Urethra Anatomy for more information.

Development of Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia

Mechanisms of disease

The prostate has been described as the organ of the body most likely to be involved

with disease of some sort in men older than 60 years. This statement characterizes any

histological evidence of BPH as a disease, which is certainly debatable, but there is no

argument that BPH is an extremely common clinical entity.

As the hyperplastic process increases the volume of the prostate, the urethral lumen is

compressed, causing outlet obstruction. An enlarged median lobe may cause relatively

more severe symptoms than lateral lobe hyperplasia of similar magnitude because it

can act as a valve at which increased bladder pressure may actually cause further

obstruction. Intravesical extension of the lateral lobes may act in a similar fashion.

It has been known for many years, however, that prostate size alone is not a reliable or

accurate predictor of the presence or degree of urinary outlet obstruction. The failure of

several purely obstructive therapies, such as prostatic balloon dilatation, and the

obvious success of alpha-adrenergic blockers eventually led to the description of BPH

as having both a dynamic (neurogenic) and a mechanical (obstructive) component.

Thus, at the same time as the occurrence of mechanical obstruction, a dynamic

component involving the stromal prostatic tissue and bladder is present, which is often

more significant in causing urinary symptoms than simple mechanical obstruction from

an enlarged prostate. The precise interaction of these two mechanisms, mechanical and

dynamic, is not well understood.

When a bladder is trying to empty through a blocked outlet from an obstructing prostate

gland, the intravesical pressure required to open the bladder neck is increased. The

bladder is initially able to produce a higher transitory voiding pressure when required,

but loses muscle tone over time.

Isolated muscle bundles hypertrophy in response to the need for a higher intravesical

pressure to overcome the increased resistance to voiding, and bladder trabeculation

often follows. The spaces between these hypertrophied bundles tend to become

thinner, with less functional muscle. Eventually, this can progress to the point at which

the bladder becomes almost nonfunctional.

Bladder trabeculation is usually graded on a scale of I-IV. When seen on cystoscopy

images, it is a relative indicator of the degree and duration of any bladder outlet

obstruction (eg, BPH), although any detrusor hyperactivity problem can possibly

produce bladder trabeculations, even without an identifiable obstruction. Initial

symptomatic changes include increased bladder instability and irritability, which can

eventually progress to muscular decompensation with permanent loss of detrusor

contractile ability.

Evidence indicates that obstruction causes partial denervation of bladder smooth

muscle, which results in further bladder irritability and involuntary detrusor contractions.

Fortunately, most of these hyperactive symptoms resolve over time with removal of the

prostatic obstruction or with a response to appropriate medications. The detrusor

becomes less able to maintain a constant voiding pressure over time, which leads to

early termination of voiding, intermittency of the urinary stream, and higher residual

urine volume, accompanied by loss of bladder compliance.

Overall bladder mass increases because of detrusor muscle hypertrophy, but collagen

deposition is also increased, which eventually contributes to decompensation, urinary

retention, and permanent loss of detrusor contractile ability.

Proposed causes

BPH is thought to be caused by aging and by long-term testosterone and

dihydrotestosterone (DHT) production, although their precise roles are not completely

clear.

Histopathologic evidence of BPH is present in approximately 8% of men in their fourth

decade and in 90% of men by their ninth decade. Loss of testosterone early in life

prevents the development of BPH. The similarities in presentation, pathological

examination findings, and symptoms of BPH among identical twins suggest a hereditary

influence.

Once BPH has developed, it tends to progress. Cross-sectional studies based on

cadaver autopsies or consecutive patients seen in urology clinics suggest that the

growth rate decreases with age. In patients aged 31-50 years, the prostate doubling

time averages 4.5 years. In men aged 51-70 years, the prostatic doubling time is

approximately 10 years, while in men older than 70 years, the doubling time increases

to more than 100 years. Note that these findings may only reflect a selection bias in the

sample group.

A 5-year longitudinal study by Rhodes and colleagues of 631 community men aged 40-

79 years from Olmsted County, Minnesota demonstrated an average annual prostate

growth rate of 1.6%. This remained essentially constant regardless of age, although

men with larger prostates tended to have higher growth rates.

The average prostate weighs approximately 20 g by the third decade and remains

relatively constant in size and weight unless BPH develops. The typical patient with

BPH has a prostate that averages 33 g. Only 4% of the male population ever develops

prostates of 100 g or larger. (The largest recorded prostatectomy specimen weighed

820 g. This prostate was removed by open suprapubic prostatectomy. Unfortunately,

the patient ultimately died of hemorrhage.)

Symptoms of BPH tend to progress slowly over time in most individuals, with an

average annual increase of 0.14-0.44 points per year in the AUA symptom index for

men aged 60 years and older. Once BPH has begun, the prostate grows an average of

0.6 mL in volume annually, with a mean decrease in average urinary peak flow rate of

0.2 mL per second each year. Men older than 70 years and those with a baseline peak

flow rate less than 10 mL/s tend to have a more rapid and dramatic decline in their peak

flow rates over time.

DHT has an affinity for prostate cell androgen receptors that is 5 times greater than that

of testosterone. The levels of 5-alpha reductase are increased in the stromal tissue of

men with BPH compared to controls. This and other data indicate that DHT is much

more important in the development of prostatic hypertrophy than testosterone is.

The success of 5-alpha reductase blockers, such as finasteride and dutasteride, in

reducing prostatic size and relieving symptoms seems to confirm this, although it does

not explain the relative lack of symptom relief in those with smaller prostate glands

treated with these agents.

Clinical manifestations and medical treatment

Classic symptoms of BPH include a slow, intermittent, or weak urinary stream; the

sensation of incomplete bladder emptying; double voiding (the need to void within a few

seconds or minutes of urinating); postvoid dribbling; urinary frequency; and nocturia.

Patients may also present with acute or chronic urinary retention, urinary tract

infections, gross hematuria, renal insufficiency, bladder pain, a palpable abdominal

mass, or overflow incontinence.

Upon physical examination, the bladder may be palpable during the abdominal

examination and the prostate may be enlarged during the digital rectal examination.

Symptoms are not necessarily proportional to the size of the prostate on digital rectal

examination or transrectal ultrasound findings.

Alpha-adrenergic receptors are present and functional in the stromal smooth muscle of

the prostate and especially at the bladder neck. Many studies have documented the

success of various alpha-adrenergic blockers in relieving symptoms of BPH. Evidence

from the Medical Therapy of Prostate Symptoms Trial indicates that combination

therapy with both an alpha-blocker and a 5-alpha reductase inhibitor can delay the

progression of symptoms and is more effective over time than either medication alone

for reducing symptom scores and improving peak urinary flow rates.

Preparing for your procedure

Your surgeon will explain how to prepare for your procedure. For example, if you smoke

you will be asked to stop, as smoking increases your risk of getting a chest and wound

infection, which can slow your recovery.

If you have been prescribed anticoagulant medicines, such as clopidogrel, which can

stop your blood from clotting, you may be advised to stop taking these before your

procedure. This is because you may bleed more after your procedure if youre taking

these.

Your surgeon will discuss with you what will happen before, during and after your

procedure, and any pain you might have. This is your opportunity to understand what

will happen, and you can help yourself by preparing questions to ask about the risks,

benefits and any alternatives to the procedure. This will help you to be informed, so you

can give your consent for the procedure to go ahead, which you may be asked to do by

signing a consent form.

The procedure is usually carried out under general anaesthesia. This means you will be

asleep during the procedure. Alternatively, you may have the procedure under spinal or

epidural anaesthesia. This completely blocks feeling from your waist down and you will

stay awake during the procedure. You may be offered a sedative with a spinal

anaesthetic this relieves anxiety and helps you to relax.

Your surgeon or anaesthetist will advise which type of anaesthesia is most suitable for

you.

If youre having a general anaesthetic, you will be asked to follow fasting instructions.

This means not eating or drinking, typically for about six hours beforehand. However,

its important to follow your anaesthetists or surgeons advice.

You may be asked to wear compression stockings to help prevent blood clots forming in

the veins in your legs. You may need to have an injection of an anticlotting medicine

called heparin as well as, or instead of, wearing compression stockings.

What happens during TURP

The procedure will take up to an hour.

Your surgeon will insert a narrow, rigid, metallic, tube-like telescopic camera called an

endoscope into your urethra (the tube that carries urine from your bladder and out

through your penis). He or she will then insert a specially adapted surgical instrument

called a resectoscope. This is an electrically heated wire loop that is used to cut out and

remove the middle of your enlarged prostate. Your surgeon will insert a catheter (a thin

flexible tube) into your urethra to drain urine from your bladder into a bag. This is

because you may not be able to urinate normally immediately after the procedure as

you may have some swelling.

What to expect afterwards

You will need to rest until the effects of the anaesthetic have passed. You may not be

able to feel or move your legs for several hours after a spinal or epidural anaesthetic.

You may need pain relief to help with any discomfort as the anaesthetic wears off.

You will have a catheter to drain urine from your bladder into a bag. The catheter will

also be used to wash out your bladder with a sterile solution, which helps to flush out

any blood clots in your bladder. The catheter will be removed when your urine begins to

run clear. This is usually within 24 to 48 hours. Occasionally, you may need to keep the

catheter in for a short period after you go home. If so, your nurse will show you how to

look after it.

You may have a drip in your arm to prevent you getting dehydrated. This will be

removed once youre drinking enough fluids. You will be encouraged to get out of bed

and move around as this helps prevent chest infections and blood clots developing in

your legs.

You will usually be able to go home after about two days. You will need to arrange for

someone to drive you home. General anaesthesia temporarily affects your co-ordination

and reasoning skills, so you must not drive, drink alcohol, operate machinery or sign

legal documents for 24 hours afterwards. If youre in any doubt about driving, contact

your motor insurer so that youre aware of their recommendations, and always follow

your surgeons advice.

Recovering from TURP

If you need pain relief, you can take over-the-counter painkillers, such as paracetamol

or ibuprofen. Always read the patient information that comes with your medicine and if

you have any questions, ask your pharmacist for advice.

You may be advised to increase your fluid intake to flush out your bladder and help you

to recover. You may find that you have some blood clots in your urine around 10 to 14

days after your procedure. These are scabs from your prostate healing and coming

away. If increasing your fluid intake doesnt clear this up, see your GP.

A small number of men get a urinary infection after the TURP procedure. If you have

any stinging when you urinate, see your GP so that your urine can be tested for an

infection. Your GP will prescribe you antibiotics if you need them.

It can take up to four weeks to recover fully from TURP. After two to three weeks you

can resume your normal activities. To help your recovery, your surgeon may

recommend that you do pelvic floor exercises. Your doctor or nurse at the hospital will

explain how to do these and how often. Please see our frequently asked questions for

more information about pelvic floor exercises.

Dont do any strenuous activity for about four weeks after your procedure. You can have

sex as soon as youre comfortable this will probably be at least three to four weeks

after your procedure.

What are the risks?

As with every procedure, there are some risks associated with TURP. We have not

included the chance of these happening as they are specific to you and differ for every

person. Ask your surgeon to explain how these risks apply to you.

Side-effects

Side-effects are the unwanted but mostly temporary effects you may get after having

the procedure, for example, feeling sick from the effects of the anaesthetic.

Some specific side-effects of TURP include the following.

Blood in your urine. This is usually an expected side-effect of the procedure and isnt

normally a cause for concern. If it continues for longer than two weeks, see your GP.

An urgent need to pass urine. This is sometimes accompanied by a burning sensation

when you pass urine.

Incontinence (urine leakage). Talk to your GP if this happens, but it usually improves

with time.

Erectile dysfunction (impotence). This doesnt usually happen and youre unlikely to be

affected if you had normal erections before your procedure.

Complications

Complications are when problems occur during or after your procedure. The possible

complications of any procedure includes an unexpected reaction to the anaesthetic,

excessive bleeding or developing a blood clot, usually in a vein in your leg (deep vein

thrombosis, DVT). Specific complications of TURP include the following.

Retrograde ejaculation. This is where semen passes into your bladder during an

orgasm instead of out of your penis. You will then pass the semen mixed with urine the

next time you urinate. Retrograde ejaculation is permanent and can affect your fertility,

so talk to your doctor if youre concerned.

Infection. You may be given antibiotics before your procedure to prevent infection.

TURP syndrome. This is a condition that can develop if the fluid used to flush your

bladder during your procedure is absorbed into your body. This can cause changes in

your blood pressure and you may feel sick or vomit. However, this is becoming less

common as a different type of fluid is often used to flush your bladder, which is less

likely to cause TURP syndrome. Please see our frequently asked questions for more

information about TURP syndrome.

Urethral stricture. This is scarring of the inside of your urethra, which causes it to

become narrower. Symptoms include problems when urinating, such as urinary

retention (being unable to pass urine at all) or incontinence (urine leakage). You may

be advised to have a further procedure to widen the inside of your urethra again.

Your prostate may grow again. If this happens, you may need to have another

procedure if too little was removed during the first procedure.

What is a transurethral resection of the prostate or TURP?

A transurethral resection of the prostate (TURP) is a surgical procedure that removes

portions of the prostate gland through the penis. A TURP requires no external incision.

The surgeon reaches the prostate by inserting an instrument through the urethra (the

narrow channel through which urine passes from the bladder out of the body). This

instrument, called a resectoscope, is about 12 inches long and one-half inch in

diameter. It contains a light, valves that control irrigating fluid, and an electrical loop that

cuts tissue and seals blood vessels. It's inserted through the penis and the wire loop is

guided by the surgeon so it can remove the obstructing tissue one piece at a time. The

pieces of tissue are carried by fluid into the bladder and flushed out at the end of the

procedure.

What is the prostate gland?

Click Image to Enlarge

The prostate gland is about the size of a walnut and surrounds the neck of a man's

bladder and urethrathe tube that carries urine from the bladder. It's partly muscular

and partly glandular, with ducts opening into the prostatic portion of the urethra. It's

made up of three lobes, a center lobe with one lobe on each side.

As part of the male reproductive system, the prostate gland's primary function is to

secrete a slightly alkaline fluid that forms part of the seminal fluid (semen), a fluid that

carries sperm. During male climax (orgasm), the muscular glands of the prostate help to

propel the prostate fluid, in addition to sperm that was produced in the testicles, into the

urethra. The semen then travels through the tip of the penis during ejaculation.

Researchers don't know all the functions of the prostate gland. However, the prostate

gland plays an important role in both sexual and urinary function. It's common for the

prostate gland to become enlarged as a man ages, and it's also likely for a man to

encounter some type of prostate problem in his lifetime.

Many common problems are associated with the prostate gland. These problems may

occur in men of all ages and include:

Benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH). An age-related enlargement of the prostate

that isn't malignant. BPH is the most common noncancerous prostate problem,

occurring in most men by the time they reach their 60s. Symptoms are slow,

interrupted, or weak urinary stream; urgency with leaking or dribbling; and frequent

urination, especially at night. Although it isn't cancer, BPH symptoms are often

similar to those of prostate cancer.

Prostatism. This involves decreased urinary force due to obstruction of flow through

the prostate gland. The most common cause of prostatism is BPH.

Prostatitis. Prostatitis is inflammation or infection of the prostate gland

characterized by discomfort, pain, frequent or infrequent urination, and sometimes

fever.

Prostatalgia. This involves pain in the prostate gland, also called prostatodynia. It's

frequently a symptom of prostatitis.

Cancer of the prostate is a common and serious health concern. According to the

American Cancer Society, prostate cancer is the most common form of cancer in men

older than age 50, and the third leading cause of death from cancer.

There are different ways to achieve the goal of removing the prostate gland. Methods of

performing prostatectomy include:

Surgical removal includes a radical prostatectomy (RP), with either a retropubic or

perineal approach. This is used to treat cancer. Radical prostatectomy is the

removal of the entire prostate gland. Nerve-sparing surgical removal is important to

preserve as much function as possible.

Transurethral resection of the prostate, or TURP, which also involves removal of part

of the prostate gland, is an approach performed through the penis with an

endoscope (small, flexible tube with a light and a lens on the end).

Cryosurgery is a less invasive procedure than surgical removal of the prostate gland.

Treatment is administered using probe-like needles that are inserted in the skin

between the scrotum and anus. The urologist can also use microwaves.

Laparoscopic surgery, done manually or by robot, is another method of removal of

the prostate gland.

Reasons for the procedure

TURP is generally done to relieve symptoms due to prostate enlargement, often due to

BPH. When the prostate gland is enlarged, the gland can press against the urethra and

interfere with or obstruct the passage of urine out of the body. BPH is a condition in

which the prostate gland may become quite enlarged and cause problems with

urination. Symptoms may include:

Problems with getting a urine stream started

Having to urinate more frequently at night

Having an urgent need to urinate

Dribbling after you finish urinating

These symptoms can create problems such as retaining urine in the bladder, which can

contribute to bladder infections or formation of stones in the bladder.

BPH can also raise prostate-specific antigen (PSA) levels two to three times higher than

the normal level. An increased PSA level doesn't always indicate cancer, but the higher

the PSA level, the higher the chance for having cancer. A TURP may be done in men

who can't tolerate a radical prostatectomy due to their age or overall health status.

Specific treatment for BPH will be determined by your doctor based on:

Your age, overall health, and medical history

Extent of the disease

Your tolerance for specific medications, procedures, or therapies

Expectations for the course of the disease

Your opinion or preference

Eventually, BPH symptoms usually require some kind of treatment. When the gland is

just mildly enlarged, treatment may not be needed, as research has shown that some of

the symptoms of BPH can clear up without treatment in some mild cases. This decision

can only be made by your doctor after careful evaluation of your individual condition.

Regular checkups are important, however, to watch for developing problems.

Sometimes a TURP is done to treat symptoms only, not to cure the disease. For

example, if you're unable to urinate because of cancer, but radical prostatectomy isn't

an option for you, you may need a TURP.

There may be other reasons for your doctor to recommend a TURP.

Risks of the procedure

As with any surgical procedure, certain complications can occur. Some possible

complications may include:

Blood in the urine after surgery

Painful or difficult urination

Possibility of infection

Retrograde ejaculation (when ejaculation occurs in the bladder and not the penis)

Bleeding

Infection

There may be other risks depending on your specific medical condition. Be sure to

discuss any concerns with your doctor prior to the procedure.

Before the procedure

Some things you can expect before the procedure include:

Your doctor will explain the procedure to you and offer you the opportunity to ask

any questions that you might have about the procedure.

You'll be asked to sign a consent form that gives permission to do the procedure.

Read the form carefully and ask questions if something isn't clear.

In addition to a complete medical history, your doctor may perform a physical

examination to ensure you're in good health before you undergo the procedure. You

may also undergo blood tests and other diagnostic tests.

You'll be asked to fast for eight hours before the procedure, generally after midnight.

Notify your doctor if you're sensitive to or are allergic to any medications, latex,

iodine, tape, contrast dyes, and anesthetic agents (local or general.)

Notify your doctor of all medications (prescribed and over the counter) and herbal

supplements that you're taking.

Notify your doctor if you have a history of bleeding disorders or if you're taking any

anticoagulant (blood-thinning) medications, aspirin, or any other medications that

affect blood clotting. It may be necessary for you to stop these medications prior to

the procedure.

If you smoke, you should stop smoking as soon as possible prior to the procedure, in

order to improve your chances for a successful recovery from surgery and to

improve your overall health status.

You may receive a sedative prior to the procedure to help you relax.

Based on your medical condition, your doctor may request other specific preparation.

During the procedure

Click Image to Enlarge

Transurethral resection of the prostate requires a stay in the hospital. Procedures may

vary depending on your condition and your doctor's practices.

Generally, a TURP follows this process:

You'll be asked to remove any jewelry or other objects that may interfere with the

procedure.

You'll be asked to remove your clothing and will be given a gown to wear.

You'll be asked to empty your bladder prior to the procedure.

An intravenous (IV) line will be started in your arm or hand.

You'll be positioned on the operating table, lying on your back.

The anesthesiologist will continuously monitor your heart rate, blood pressure,

breathing, and blood oxygen level during the surgery. Once you're sedated, a

breathing tube will be inserted through your throat into your windpipe and you'll be

connected to a ventilator, which will breathe for you during the surgery.

The surgeon will inspect the urethra and bladder with an endoscope. This is done by

passing the scope through the tip of the penis, then into the urethra and bladder. This

allows the doctor to examine these areas for any tumors or stones in the bladder.

Next, the resectoscope (electrical loop) is passed into the urethra. It cuts out pieces

of tissue from the prostate that are bulging or blocking the urethra. Electricity will be

applied through the resectoscope to stop any potential bleeding.

The doctor will insert a catheter into the bladder to empty urine.

You'll be transferred from the operating table to a bed then taken to the recovery

room.

After the procedure

In the hospital

After the procedure, you may be taken to the recovery room to be closely monitored.

You'll be connected to monitors that will constantly display your electrocardiogram (ECG

or EKG) tracing, blood pressure, other pressure readings, breathing rate, and your

oxygen level.

Once your blood pressure, pulse, and breathing are stable and you're alert, you'll be

taken to your hospital room.

You may receive pain medication as needed, either by a nurse, or by administering it

yourself through a device connected to your intravenous line.

Once you're awake and your condition has stabilized, you may start liquids to drink.

Your diet may be gradually advanced to more solid foods as you are able to tolerate

them.

The urine catheter will stay in place for one to three days to help urine drain while your

prostate gland heals. You'll probably have blood in your urine after surgery.

Also, a liquid solution may be attached to the catheter to flush the blood and potential

clots out of the catheter. The bleeding will gradually decrease, and then the catheter will

be removed.

Arrangements will be made for a follow-up visit with your doctor.

Your doctor may give you additional or alternate instructions after the procedure,

depending on your particular situation.

At home

Once you're home, it'll be important to drink lots of fluid. This aids in flushing out any

remaining blood or clots from your bladder.

You'll be advised to not do any heavy lifting for several weeks after the TURP. This is to

prevent any recurrence of bleeding.

You may be tender or sore for several days after a TURP. Take a pain reliever for

soreness as recommended by your doctor.

You shouldn't drive until your doctor tells you to. Other activity restrictions may apply.

Notify your doctor to report any of the following:

Fever and/or chills

Redness, swelling, or bleeding or other drainage from the incision site

Increase in pain around the incision site

Trouble urinating

Your doctor may give you additional or alternate instructions after the procedure,

depending on your particular situation.

You might also like

- NCP For Urinary RetentionDocument5 pagesNCP For Urinary RetentionColeen Comelle Huerto60% (5)

- Acute Renal FailureDocument33 pagesAcute Renal FailureAqsa Akbar AliNo ratings yet

- Case Study CLD 1Document12 pagesCase Study CLD 1MoonNo ratings yet

- LeptospirosisDocument9 pagesLeptospirosisDeepu VijayaBhanuNo ratings yet

- DSMTS 0005 3 AlODocument4 pagesDSMTS 0005 3 AlOSimanchal KarNo ratings yet

- Yarn ManufacturerersDocument31 pagesYarn ManufacturerersMarufNo ratings yet

- A Simple Guide to Parathyroid Adenoma, Diagnosis, Treatment and Related ConditionsFrom EverandA Simple Guide to Parathyroid Adenoma, Diagnosis, Treatment and Related ConditionsNo ratings yet

- StomachGastricCancerDocument12 pagesStomachGastricCancerBhawna JoshiNo ratings yet

- Brain TumorDocument50 pagesBrain TumorbudiNo ratings yet

- Drug StudyDocument8 pagesDrug StudyJheryck SabadaoNo ratings yet

- Cholelithiasis GallstoneDocument22 pagesCholelithiasis GallstoneBheru LalNo ratings yet

- NeuroblastomaDocument4 pagesNeuroblastomaGeleine Curutan - OniaNo ratings yet

- Abdominal Trauma Is An Injury To The Abdomen. Signs and Symptoms Include AbdominalDocument5 pagesAbdominal Trauma Is An Injury To The Abdomen. Signs and Symptoms Include AbdominalVictoria DolințăNo ratings yet

- Case Pre Ovarian CystDocument56 pagesCase Pre Ovarian Cystthesa1201No ratings yet

- Devices Used in ICU: Critical Care NursingDocument95 pagesDevices Used in ICU: Critical Care NursinghendranatjNo ratings yet

- MI LABS ExplainedDocument3 pagesMI LABS Explainedjrubin83669No ratings yet

- Chronic Kidney DiseaseDocument7 pagesChronic Kidney DiseaseLardel Balbiran LafortezaNo ratings yet

- CellulitisDocument15 pagesCellulitisSujatha J JayabalNo ratings yet

- STI College of Nursing Sta. Cruz, Laguna College of Nursing: Submitted To: Mrs. Aurea Celino, RN Clinical InstructorDocument41 pagesSTI College of Nursing Sta. Cruz, Laguna College of Nursing: Submitted To: Mrs. Aurea Celino, RN Clinical InstructorPong's Teodoro SalvadorNo ratings yet

- Case Study PresentationDocument44 pagesCase Study Presentationapi-31876231450% (2)

- CholelitiasisDocument42 pagesCholelitiasisEdwin YosuaNo ratings yet

- Case Study About: Cardiac Failure and Pulmonary EdemaDocument32 pagesCase Study About: Cardiac Failure and Pulmonary EdemaIan Simon DorojaNo ratings yet

- A Drug Study On: EpinephrineDocument16 pagesA Drug Study On: EpinephrineJay Jay JayyiNo ratings yet

- Pulmonary AngiographyDocument3 pagesPulmonary AngiographyBiway RegalaNo ratings yet

- Pyloric StenosisDocument2 pagesPyloric Stenosisreshmivunni0% (1)

- 10 Golden Rules of IV TherapyDocument8 pages10 Golden Rules of IV Therapybbasya eihynaNo ratings yet

- Throid StormDocument19 pagesThroid StormDurgesh PushkarNo ratings yet

- Case Study JatDocument45 pagesCase Study JatHSEINNo ratings yet

- Abnormal LabourDocument7 pagesAbnormal LabourSaman SarKo0% (1)

- Miconium Aspiration SyndromeDocument19 pagesMiconium Aspiration SyndromeEnna PaulaNo ratings yet

- Cholecystectomy (: Laparoscopic GallstonesDocument4 pagesCholecystectomy (: Laparoscopic GallstonesAlexia BatungbacalNo ratings yet

- Men in NursingDocument2 pagesMen in NursingMark JosephNo ratings yet

- LYMPHOMADocument12 pagesLYMPHOMAश्रीकृष्ण हेङ्गजूNo ratings yet

- Product Information Avil Product NamesDocument4 pagesProduct Information Avil Product Namesindyanexpress100% (1)

- Thrombolytic TherapyDocument16 pagesThrombolytic TherapyAnonymous nrZXFwNo ratings yet

- 130300-Standards For Acute and Critical Care NursingDocument12 pages130300-Standards For Acute and Critical Care Nursingapi-315277523No ratings yet

- Myocardial Infarction: Signs and SymptomsDocument5 pagesMyocardial Infarction: Signs and SymptomsKelly OstolNo ratings yet

- Cushings SyndromeDocument51 pagesCushings SyndromeTina TalmadgeNo ratings yet

- Dr. H. Achmad Fuadi, SPB-KBD, MkesDocument47 pagesDr. H. Achmad Fuadi, SPB-KBD, MkesytreiiaaNo ratings yet

- Asking Your Question (PICO) - NursingDocument5 pagesAsking Your Question (PICO) - NursingBentaigaNo ratings yet

- Oro & Nasopharyngeal SuctioningDocument16 pagesOro & Nasopharyngeal SuctioningHERLIN HOBAYANNo ratings yet

- Acute GlomerulonephritisDocument7 pagesAcute GlomerulonephritisSel CuaNo ratings yet

- HypomagnesemiaDocument7 pagesHypomagnesemiaNader SmadiNo ratings yet

- Surgical Treatment For BREAST CANCERDocument5 pagesSurgical Treatment For BREAST CANCERJericho James TopacioNo ratings yet

- 6 Managing Complications of IVTDocument42 pages6 Managing Complications of IVT4LetterLie31No ratings yet

- SmallpoxDocument3 pagesSmallpoxKailash NagarNo ratings yet

- Tracheostomy Care: PhysiologyDocument2 pagesTracheostomy Care: PhysiologyrajirajeshNo ratings yet

- DEFINITION: Abortion Is The Expulsion or Extraction From Its MotherDocument10 pagesDEFINITION: Abortion Is The Expulsion or Extraction From Its MothermOHAN.SNo ratings yet

- Case StudyDocument23 pagesCase StudyFarah Jelimae BagniNo ratings yet

- Hypertension Health EducationDocument5 pagesHypertension Health EducationOrlino PeterNo ratings yet

- Treatments and Drugs: by Mayo Clinic StaffDocument23 pagesTreatments and Drugs: by Mayo Clinic StaffJr D BayzNo ratings yet

- RBS and FBSDocument5 pagesRBS and FBSAllenne Rose Labja Vale100% (1)

- Pulmonary Function TestsDocument2 pagesPulmonary Function TestsSafuan Sudin100% (1)

- MSN CASE STUDY FORMATnew-1Document26 pagesMSN CASE STUDY FORMATnew-1Dinesh BanerjeeNo ratings yet

- Chronic Renal FailureDocument7 pagesChronic Renal FailureMary Jane Tiangson100% (1)

- Cerebral Aneurysm Case Analysis and Concept MapDocument5 pagesCerebral Aneurysm Case Analysis and Concept Mapate NarsNo ratings yet

- Wound AssessmentDocument19 pagesWound Assessmentdrsonuchawla100% (1)

- Burn RehabilitationDocument4 pagesBurn RehabilitationSuneel Kumar PrajapatiNo ratings yet

- Hirschsprung’s Disease, A Simple Guide To The Condition, Diagnosis, Treatment And Related ConditionsFrom EverandHirschsprung’s Disease, A Simple Guide To The Condition, Diagnosis, Treatment And Related ConditionsNo ratings yet

- COMPREHENSIVE NURSING ACHIEVEMENT TEST (RN): Passbooks Study GuideFrom EverandCOMPREHENSIVE NURSING ACHIEVEMENT TEST (RN): Passbooks Study GuideNo ratings yet

- Gastric Outlet Obstruction, A Simple Guide To The Condition, Diagnosis, Treatment And Related ConditionsFrom EverandGastric Outlet Obstruction, A Simple Guide To The Condition, Diagnosis, Treatment And Related ConditionsNo ratings yet

- The Ride of Your Life: What I Learned about God, Love, and Adventure by Teaching My Son to Ride a BikeFrom EverandThe Ride of Your Life: What I Learned about God, Love, and Adventure by Teaching My Son to Ride a BikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (2)

- Ebstein Anomaly, A Simple Guide To The Condition, Diagnosis, Treatment And Related ConditionsFrom EverandEbstein Anomaly, A Simple Guide To The Condition, Diagnosis, Treatment And Related ConditionsNo ratings yet

- CefuroximeDocument4 pagesCefuroximeColeen Comelle HuertoNo ratings yet

- Terminal Care What Is Terminal Care?Document6 pagesTerminal Care What Is Terminal Care?Coleen Comelle HuertoNo ratings yet

- FLUID and ElectrolytesDocument18 pagesFLUID and ElectrolytesColeen Comelle HuertoNo ratings yet

- Claudine Huerto MrsDocument4 pagesClaudine Huerto MrsColeen Comelle HuertoNo ratings yet

- Report PaperDocument1 pageReport PaperColeen Comelle HuertoNo ratings yet

- AldazideDocument1 pageAldazideColeen Comelle HuertoNo ratings yet

- Introduction of Africa and AsiaDocument9 pagesIntroduction of Africa and AsiaEllen Jane SilaNo ratings yet

- Eon 2019 Sustainability ReportDocument122 pagesEon 2019 Sustainability ReportDarryl Farhan WidyawanNo ratings yet

- Wild Magic Extended ListDocument6 pagesWild Magic Extended ListbeepboopbotNo ratings yet

- DJ X11Document113 pagesDJ X11AbrahamNo ratings yet

- Barbering M1 2nd SemDocument10 pagesBarbering M1 2nd Semjaymarnel1996No ratings yet

- Basketball-2 0Document46 pagesBasketball-2 0Catherine EscartinNo ratings yet

- Chapter 12Document58 pagesChapter 12reymark ramiterreNo ratings yet

- Protocol Document 1.1.4Document114 pagesProtocol Document 1.1.4Jose Daniel Zaraza Marcano100% (2)

- Mod 2Document150 pagesMod 2Prem SivamNo ratings yet

- WDM OTN Raman Feature Guide 05Document218 pagesWDM OTN Raman Feature Guide 05Ghallab Alsadeh100% (1)

- Gothra PattikaDocument172 pagesGothra PattikaParimi VeeraVenkata Krishna SarveswarraoNo ratings yet

- Autoclaved Aerated ConcreteDocument4 pagesAutoclaved Aerated ConcreteArunima DineshNo ratings yet

- Essay On All The Light We Cannot SeeDocument2 pagesEssay On All The Light We Cannot SeeJosh StephanNo ratings yet

- Different DietsDocument7 pagesDifferent DietsAntonyNo ratings yet

- Epidemiology and Public Health: Burton's Microbiology For The Health SciencesDocument33 pagesEpidemiology and Public Health: Burton's Microbiology For The Health SciencesMarlop Casicas100% (1)

- Official Ncm0200 Baird Parker Agar Base Technical Specifications en UsDocument3 pagesOfficial Ncm0200 Baird Parker Agar Base Technical Specifications en UsBty SaGNo ratings yet

- SIemens Air Damper ActuatorDocument40 pagesSIemens Air Damper ActuatorHENRYNo ratings yet

- Transport Management PlanDocument13 pagesTransport Management Planprmrao100% (3)

- Report Global Hemodialysis and Peritoneal Dialysis Market Size Estimates & Forecasts Through 2027Document235 pagesReport Global Hemodialysis and Peritoneal Dialysis Market Size Estimates & Forecasts Through 2027FaisalNo ratings yet

- IAAC Final Round 2020Document9 pagesIAAC Final Round 2020Dennil JobyNo ratings yet

- Updated Term Paper (5310) PDFDocument21 pagesUpdated Term Paper (5310) PDFSourae MridhaNo ratings yet

- Trends 11 Syllabus 5&6Document8 pagesTrends 11 Syllabus 5&6Victor John DagalaNo ratings yet

- Review Paper: There Are 5 Branches That We Choose To TasteDocument3 pagesReview Paper: There Are 5 Branches That We Choose To TasteAllysa BatoliñoNo ratings yet

- My Happy Marriage Volume 03 LNDocument252 pagesMy Happy Marriage Volume 03 LNnailsnailsgoodinbed100% (2)

- Equine Facilitated TherapyDocument100 pagesEquine Facilitated TherapyBasil Donovan Fletcher100% (1)

- LEAP Brochure 2013Document15 pagesLEAP Brochure 2013Reparto100% (1)

- NCR 7403 Uzivatelska PriruckaDocument149 pagesNCR 7403 Uzivatelska Priruckadukindonutz123No ratings yet

- Lasers in Oral MedicineDocument35 pagesLasers in Oral MedicineShreya singh0% (1)