Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Cerny Fixed Retainer

Cerny Fixed Retainer

Uploaded by

chinchiayeh5699Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Cerny Fixed Retainer

Cerny Fixed Retainer

Uploaded by

chinchiayeh5699Copyright:

Available Formats

Contents

Original articles

1 Comparison of surgical and non-surgical methods of treating palatally impacted canines.

I Periodontal and pulpal outcomes

Kwok K. Ling, Christopher T.C. Ho, Olena Kravchuk and Richard J. Olive

8 Comparison of surgical and non-surgical methods of treating palatally impacted canines.

II Aesthetic outcomes

Kwok K. Ling, Christopher T.C. Ho, Olena Kravchuk and Richard J. Olive

16 Changes in interdental papillae heights following alignment of anterior teeth

Sanjivan Kandasamy, Mithran Goonewardene and Marc Tennant

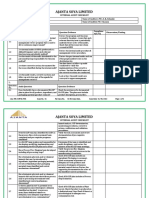

24 The reliability of bonded lingual retainers

Robert Cerny

30 Sella turcica bridges in orthodontic and orthognathic surgery patients. A retrospective cephalometric study

Hussam M. Abdel-Kader

36 Static frictional resistances of polycrystalline ceramic brackets with conventional slots, glazed slots and metal

slot inserts

Steven P. Jones and Gyaami Amoah

41 Lower intercanine width and gingival margin changes. A retrospective study

Luciane Closs, Karine Squeff, Dirceu Raveli and Cassiano Rsing

46 Effect of Topacal C-5 on enamel adjacent to orthodontic brackets. An in vitro study

Navid Karimi Nasab, Zahra Dalili Kajan and Azadeh Balalaie

50 The impact of orthodontic treatment on normative need. A case-control study in Peru

Eduardo Bernab, Socorro A. Borges-Yez and Carlos Flores-Mir

Review

55 Three-dimensional computed craniofacial tomography (3D-CT): potential uses and limitations

Hong Jin Chan, Michael Woods and Damien Stella

Case reports

65 Treatment of skeletal 2 malocclusion using bone-plate anchorage. A case report

Kallaya Kraikosol, Charunee Rattanayatikul, Keith Godfrey and T. Vattraraphoudet

72 Space closure using the Hycon device. A case report

Viral A. Kachiwala, Anmol S. Kalha and J. Vigneshwaran

Editorial

76 Forty years of publication

Michael Harkness

General

78 Book reviews

81 Recent publications

84 New Products

86 Calendar

Australian

Orthodontic Journal

Volume 23 Number 1, May 2007

Australian Orthodontic Journal Volume 23 No. 1 May 2007

Introduction

The preferred management of an ectopic or impacted

palatal canine is early diagnosis and interceptive

treatment, often involving extraction of the overlying

primary canine in the hope that the impaction will

resolve spontaneously.

18

The success of this form of

treatment appears to be related to the timing of treat-

ment and availability of space in the dental arch.

7,9,10

If diagnosis of an ectopic canine is delayed or if

extraction of the primary canine and creation of

excess space in the arch fails to correct an impaction,

the only reliable option appears to be surgical expo-

sure followed by orthodontic treatment to extrude

and position the impacted tooth in the arch.

Part of the reluctance for surgical treatment is the

likelihood of poor periodontal and pulpal out-

comes.

1116

However there is some dispute about

the clinical significance of undesirable periodontal

and pulpal changes following surgical exposure of

impacted canines.

13,15,17

The aims of this study were to compare the

periodontal and pulpal health of palatally

impacted maxillary canines following either surgical

exposure and assisted eruption or unassisted

eruption following extraction of the overlying

deciduous canine and orthodontic creation of space

in the arch.

Subjects and methods

Ethical clearance for this study was obtained from the

Medical Research Ethics Committee of the University

of Queensland. The subjects were selected from the

Australian Orthodontic Journal Volume 23 No. 1 May 2007 1

Comparison of surgical and non-surgical methods

of treating palatally impacted canines.

I - Periodontal and pulpal outcomes

Kwok K. Ling,

*

Christopher T. C. Ho,

*

Olena Kravchuk

and Richard J. Olive

School of Dentistry,

*

School of Land and Food Sciences,

University of Queensland and Specialist Practice,

Brisbane, Australia

Background: Inferior periodontal and pulpal outcomes may follow surgical exposure of palatally impacted maxillary canines.

Objectives: To compare the periodontal and pulpal health of palatally impacted maxillary canines following either surgical

exposure and assisted eruption (SE) or unassisted eruption following extraction of the overlying deciduous canine and

orthodontic creation of space in the arch (OT).

Methods: Twentyeight subjects (OT group: N = 14; SE group: N = 14) with unilateral palatally impacted canines were

examined at least six months after orthodontic treatment. The gingival index score, plaque index score, pocket depth,

attachment loss, tenderness to percussion, pulpal responses to stimuli and radiographic assessment of changes in the pulpal

cavities and peri-radicular areas were collected on the maxillary canines, lateral incisors and premolars. The contralateral teeth

were used as controls.

Results: There were no significant differences in the plaque index scores, the gingival index scores or the periodontal outcomes

between the impacted canines in the two groups (SE and OT). More impacted canines than control canines had lost some

periodontal attachment in the SE group (p = 0.004). Although more lateral incisors, canines and premolars on the impacted

side had partially obliterated pulps than the corresponding teeth on the control side, the teeth in both groups had similar pulpal

responses (p = 0.064).

Conclusions: Natural eruption and conservative surgical exposure with orthodontic alignment have minor effects on the

periodontium. Impacted canines treated surgically and non-surgically had a higher prevalence of pulpal changes than the control

canines. Ultimately, the choice of treatment may depend on the clinical indications, the patients and the orthodontists preferences.

(Aust Orthod J 2007; 23: 17)

Received for publication: July 2006

Accepted: February 2007

records of three orthodontic practices providing they

met the following criteria:

1. A unilateral palatally impacted canine was present.

2. A pretreatment panoramic radiograph was available.

3. There was no significant medical history.

4. Treatment had been completed for at least six

months.

5. In the surgical group, the subjects had undergone

conservative surgical exposure and the wound had

been dressed for 710 days before any orthodontic

attachments were bonded.

Of the 28 subjects who met these requirements and

were examined at least six months post-treatment, 14

subjects (5 males, 9 females) had been treated by

extraction of the overlying deciduous canine and

creation of excess space in the arch (OT group) and

14 subjects (2 males, 12 females) had been treated by

open surgical exposure followed by orthodontic

extrusion and alignment of the canine in the arch (SE

group). In the latter group the surgery was performed

by different oral and maxillofacial surgeons and the

wounds were dressed for between seven and 10 days.

One orthodontist treated the subjects in the OT

group and three orthodontists treated the subjects in

the SE group. At the time of the post-treatment

examination the subjects in the OT group were, on

average, 19.1 years of age and the subjects in the SE

group were 18.8 years of age (Table I).

The pretreatment panoramic radiographs were used

to classify the sector of impaction using Lindauer

et al.s

18

modification of Ericson and Kurols

classification.

6

Two subjects in the OT group were

treated with extraction of both maxillary second pre-

molars.

Post-treatment assessments of the maxillary

lateral incisors, canines and first premolars

Periodontal assessments

The assessor (KKL) was blinded as to the identity of

the side with the impacted canine. Oral hygiene was

assessed with the Plaque Index,

19

and gingival health

with the Gingival Index.

20

Pocket depths were meas-

ured at six sites (mesio-buccal, mid-buccal, disto-

buccal, mesio-palatal, mid-palatal and disto-palatal)

around each tooth using a University of Michigan O

probe with Williams markings. Pocket depths were

measured from the gingival margins to the bottom of

the clinical pockets. The distance from the gingival

margin to the cemento-enamel junction (CEJ) was

also measured, and loss of attachment was deter-

mined by subtracting this distance from the pocket

depth measurement.

12,16

When the level of the CEJ

could not be located, it was assumed to be situated at

the bottom of the clinical pocket.

16

All clinical meas-

urements were made to the nearest 0.25 mm and

were repeated 10 minutes after the initial recordings.

Percussion and vitality assessments

Percussion tests were performed by tapping the incisal

edges or occlusal surfaces of the teeth with the blunt

end of a dental mirror handle. The response to this

test was recorded as either positive or negative. For

the cold thermal test each tooth was isolated with

cotton rolls and dried thoroughly. A cotton pellet

soaked with carbon dioxide spray (Miracold spray,

LING ET AL

Australian Orthodontic Journal Volume 23 No. 1 May 2007 2

Table I. Description of the sample.

OT (N=14) SE (N=14) p

p

+

Mean (SD) Mean (SD)

Male : Female 5 : 9 2 : 12 0.190

Right : Left proportion 8 : 6 4 : 10 0.127

Sector of impaction II : III : IV 5 : 7 : 2 1 : 4 : 9 0.019

Age at start of treatment (years) 13.5 (1.3) 13.5 (1.6) 0.979

Age at recall (years) 19.1 (2.2) 18.8 (2.5) 0.749

Active treatment duration (months) 27.9 (9.3) 28.4 (7.5) 0.877

Recall period (years) 3.4 (3.0) 3.2 (2.4) 0.847

Chi-squared test, significant value in bold

+

Students t-test

Hager Werke, Germany) was then applied to the

middle of the tooth. A negative response was regis-

tered if no sensation was reported after 10 seconds.

The electrical pulp test was carried out with an

Analytic Technology vitality scanner (Analytic

Technology Corporation, Redmond, Washington,

USA). Each tooth was isolated with cotton rolls and

dried and the tip of the probe, coated with toothpaste

as conductant, placed on the incisal third midway

between the mesial and distal surfaces of each tooth.

21

If part of the clinical crown had been restored the

probe was placed on the enamel as close as possible

to the incisal third of the tooth. If sensation was

reported before the reading reached 80, a positive

response was recorded. A negative response was

recorded if no sensation was felt when the reading

reached 80.

To assess reliability, the percussion and vitality tests

were repeated 10 minutes after the initial recordings.

One subject in the SE group had a root-filled lateral

incisor on the impacted side. This tooth had been

traumatised and root-filled prior to orthodontic

treatment and was excluded from the percussion and

vitality tests.

Radiographic assessment

Periapical radiographs were taken of the lateral

incisors, canines and first premolars on both sides.

Radiographic changes in the pulpal cavities and peri-

radicular areas were evaluated using the criteria

described by Jacobsen and Kerekes.

22

Total obliter-

ation of the pulp chamber was noted if the pulp

chamber and root canal were not discernible and

partial obliteration was noted if the root canal was

markedly narrowed, but clearly visible. Previous

endodontic treatment was also recorded. The peri-

radicular area was registered as normal if the

periodontal space was of normal width and as patho-

logical if there was marked widening of the space or

there was an associated radiolucent area. All radio-

graphs were re-evaluated one week after the initial

assessment.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was carried out with Minitab for

Windows (Release 14, Minitab Inc., USA) and the

significance level for all statistical procedures was set

at 5 per cent. Additionally, SPSS for Windows

(Version 12.0, SPSS Inc., Chicago, USA) was used to

perform the McNemar test. The Bonferroni correc-

tion was applied where appropriate. Chi-squared tests

were used to analyse the difference between the two

groups in terms of gender, side and sector of

impaction. Treatment-related variables, such as age at

commencement of treatment, age at recall, duration

of active treatment and recall period, were compared

with the unpaired t-test.

Plaque Index and Periodontal Index data were

analysed with the Mann-Whitney test. The pro-

portions of subjects with index scores greater than

zero were analysed with the binomial test for propor-

tions. The maximum score for each site was noted to

provide a clinical picture of severity.

To address reliability issues, periodontal measure-

ments taken 10 minutes apart were statistically

analysed using the paired t-test. Average values of the

measurements were used for subsequent analysis if no

significant differences were detected between two

time points. Differences between the groups for the

mean probing pocket depths were tested using

unpaired t-tests. Paired t-tests were used to test for

differences within the groups (e.g. between the

impacted canine and the contralateral control

canine).

Attachment loss was analysed by comparing the pro-

portions of teeth with attachment losses. The Mood

Median Test was used to compare the difference in

maximum attachment loss and to give a confidence

interval, which may indicate the potential attachment

loss to be expected in each group. Fishers Exact test

was used to test the differences in proportion between

groups for percussion tests, vitality responses and

radiographic findings.

Results

Subjects in both groups were similar in terms of the

gender distribution, the proportion of impacted

canines on either the right or the left side, age at com-

mencement of treatment, age at recall, the duration

of treatment and the post-treatment recall period.

The latter was the period that had elapsed from the

end of active treatment to the date of examination for

this study (Table I). The only significant difference

between the SE and OT groups was the distribution

of subjects in the sectors of impaction (p = 0.019).

There was a higher percentage of sector IV

impactions in the surgical group, which is not

SURGICAL AND NON- SURGICAL METHODS OF TREATING PALATALLY IMPACTED CANINES. I - PERIODONTAL AND PULPUL OUTCOMES

Australian Orthodontic Journal Volume 23 No. 1 May 2007 3

surprising as severe impaction is generally not

amenable to orthodontic treatment alone.

9

The Plaque Index and Gingival Index scores in the

two groups were similar (Table II). The proportions

of subjects in the OT group with a total Plaque Index

score above zero was greater on the impacted side in

comparison with the non-impacted side, but the

difference was not statistically significant (Table II).

The maximum Plaque and Gingival Index scores at

individual tooth sites did not exceed two.

There were no statistically significant differences

between the initial and second measurements of

pocket depth and the level of the cemento-enamel

junction.

The pocket depths ranged from 0.5 to 3 mm (Figures

1 to 3). When the pocket depths on the impacted side

were compared with the pocket depths on the contra-

lateral teeth, only the disto-palatal sites of the lateral

incisors on the impacted side in the OT group were

significantly deeper (Mean difference: 0.28 mm; SD:

0.33 mm; Paired t-test: p = 0.007) (Figure 1). The

periodontal pockets were significantly deeper mid-

buccally on the control lateral incisor in the SE group

when compared with the OT group (Mean differ-

ence: 0.20 mm; Pooled SD: 0.21 mm; Unpaired

t-test: p = 0.020) and mid-palatally on the control

canine (Mean difference: 0.25 mm; Pooled SD: 0.32

mm; Unpaired t-test: p = 0.048) (Figures 1 and 2).

One subject in the OT group had lost periodontal

attachment on the lateral incisors, canines and

premolars (Table III). In the SE group the number of

previously impacted canines with attachment loss was

LING ET AL

Australian Orthodontic Journal Volume 23 No. 1 May 2007 4

Table II. Comparison of the Plaque Index and Gingival Index scores

greater than zero.

Group Impacted side Control side p

Plaque Index

OT (N=14) 10 5 0.063

SE (N=14) 8 6 0.500

p

+

0.695 1

Gingival Index

OT (N=14) 7 3 0.219

SE (N=14) 10 6 0.219

p

+

0.440 0.420

McNemar test

+

Fishers Exact test Figure 1. Box plot of probing pocket depth for lateral incisors. Impacted

side (I); non-impacted side (N); mesio-buccal (MB); mid-buccal (MidB);

disto-buccal (DB); mesio-palatal (MP); mid-palatal (MidP); disto-palatal (DP).

Figure 2. Box plot of probing pocket depth for canines. Impacted side (I);

non-impacted side (N); mesio-buccal (MB); mid-buccal (MidB); disto-buccal

(DB); mesio-palatal (MP); mid-palatal (MidP); disto-palatal (DP).

Figure 3. Box plot of probing pocket depth for first premolars. Impacted

side (I); non-impacted side (N); mesio-buccal (MB); mid-buccal (MidB); disto-

buccal (DB); mesio-palatal (MP); mid-palatal (MidP); disto-palatal (DP).

P

o

c

k

e

t

d

e

p

t

h

(

m

m

)

P

o

c

k

e

t

d

e

p

t

h

(

m

m

)

P

o

c

k

e

t

d

e

p

t

h

(

m

m

)

Treatment

and sites

Treatment

and sites

Treatment

and sites

OT OT OT OT OT OT OT OT OT OT OT OT

SE SE SE SE SE SE SE SE SE SE SE SE

IMB NMB IMidB NmidB IDB NDB IMP NMP IMidP NMidP IDP NDP

OT OT OT OT OT OT OT OT OT OT OT OT

SE SE SE SE SE SE SE SE SE SE SE SE

IMB NMB IMidB NmidB IDB NDB IMP NMP IMidP NMidP IDP NDP

OT OT OT OT OT OT OT OT OT OT OT OT

SE SE SE SE SE SE SE SE SE SE SE SE

IMB NMB IMidB NmidB IDB NDB IMP NMP IMidP NMidP IDP NDP

Boxplot of pocket depth for first premolars, OT vs SE

Boxplot of pocket depth for lateral incisors, OT vs SE

Boxplot of pocket depth for canines, OT vs SE

3.0

2.5

2.0

1.5

1.0

0.5

3.0

2.5

2.0

1.5

1.0

3.0

2.5

2.0

1.5

1.0

0.5

0.0

significantly greater than the number of control

canines with loss of attachment (Table III). On the

impacted sides, attachment loss (in any site) was

found in five subjects (35.7 per cent) in the OT

group and in 10 subjects (71.4 per cent) in the SE

group. The proportion of subjects with attachment

loss on the impacted side in both groups was not

significantly different (Fishers Exact test; p = 0.128).

The maximum loss of attachment around any of the

six teeth tested was 1.75 mm. The maximum loss of

attachment in the SE group was greater than the loss

of attachment in the OT group at the 10 per cent

level of significance (Mood Median test: p = 0.058).

Ninety-five per cent confidence levels indicated that

SE treatment would result in a maximum attachment

loss of up to 1.01 mm greater than in the OT group.

All teeth tested responded normally to the percussion

test. More teeth failed to respond to the cold thermal

test (19 teeth) compared with the electrical pulp test

(2 teeth), but only two teeth did not respond to both

tests. One of these was a lateral incisor on the non-

impacted side in the OT group and the other was a

lateral incisor on the impacted side in the SE group.

The pulpal responses by the teeth in the SE and OT

groups were similar (p > 0.05).

None of the teeth (canines, lateral incisors, pre-

molars) showed periapical pathology on the radio-

graphs. Pulpal pathology was not detected in any

teeth on the control side in either group. The pulps

were partially obliterated in two premolars (14 per

cent) and one canine (7 per cent) on the impacted

side in the OT group, and in two lateral incisors (14

per cent) on the impacted side in the SE group. One

lateral incisor (7 per cent) on the impacted side from

the surgical group was endodontically treated prior to

orthodontic treatment due to trauma. Overall, four

out of 27 subjects (15 per cent) showed partial pulpal

obliteration or had root treatment on the impacted

side compared with the control side and this is sig-

nificant at the 10 per cent level of significance

(McNemar test, p = 0.064).

Discussion

Both methods of treatment for palatally impacted

maxillary canines had comparable periodontal and

pulpal outcomes. Both methods were accompanied

by minor periodontal changes, and a higher incidence

of pulpal changes occurred in the previously

impacted canines. The latter did not appear to be of

any clinical significance. The choice of treatment may

depend on the clinical situation, the patients and the

orthodontists preferences. Conservative surgical

exposure followed by assisted eruption was more

suited to severe impactions.

A potential problem with the present study is the

small sample size. Analysis of the required sample size

to detect a difference between the groups was not per-

formed as the magnitude of the difference between

the groups had not been previously tested. While

there was no indication that the small sample

affected our ability to draw conclusions regarding the

periodontal outcomes, a larger sample may have

improved our ability to detect a difference in the pul-

pal outcomes. The possibility of sampling bias cannot

be dismissed as any retrospective study may be prone

to selection bias, where patients unhappy with the

treatment outcome may be unwilling to participate in

the study, resulting in an underestimation of the com-

plications of the treatment. One of the strengths of

our study is our finding that the age of the subjects

and the duration of active treatment of the two

groups were similar.

Although we found more previously impacted

canines than control canines in the SE group had lost

SURGICAL AND NON- SURGICAL METHODS OF TREATING PALATALLY IMPACTED CANINES. I - PERIODONTAL AND PULPUL OUTCOMES

Australian Orthodontic Journal Volume 23 No. 1 May 2007 5

Table III. Loss of periodontal attachment in the OT and SE groups.

OT SE OT vs SE

Teeth (N=14) (N=14) Impacted side

Impacted side Control side p

Impacted side Control side p

p

+

Lateral incisors 3 1 0.500 4 0 0.125 0.661

Canines 5 1 0.125 7 0 0.004 0.440

Premolars 2 1 1.000 2 0 0.500 1.000

McNemar test, significant value in bold

+

Fishers Exact test

some periodontal attachment, the difference between

the impacted sides in the OT and SE groups was not

statistically significant. The proportion of subjects

with attachment loss at all sites suggests that impact-

ed canines fared less favourably than the control

canines in the SE group, which is in agreement with

previous studies.

11,16,23,24

Impacted canines treated

surgically may be more likely to suffer some loss of

attachment than impacted canines treated non-

surgically. Gingival recession with an exposed cemento-

enamel junction was not found in any of the

subjects. Attachment loss appeared to be confined

to particular subjects and was usually present in

multiple sites. Loss of periodontal attachment on the

control side was minimal and found in only one sub-

ject. This subject demonstrated poor oral hygiene at

the recall appointment and had generalised enamel

demineralisation indicative of inadequate plaque

control during orthodontic treatment, and loss of

periodontal attachment on both the impacted and

control sides. Attachment loss appears to be a rare

event in patients receiving treatment for impacted

canines.

14,16

Pulpal changes were similar in both groups. Five out

of 84 teeth (6 per cent) on the impacted side showed

partial pulpal obliteration or were treated endo-

dontically, which is significantly higher than the con-

trol side. Only teeth from the impacted side were

affected, but these effects were not limited to the

canines. They included two premolars in the OT

group and two lateral incisors in the SE group. In

agreement with Blair et al.

15

we found few teeth on

the impacted side had pulpal changes, and fewer teeth

than the number reported by Woloshyn et al.

13

The

subjects in Woloshyn et al.s study were four years

older and had a wider age range than our study,

which may account for this difference since pulpal

obliteration is age-related.

22

Changes in the pulpal

response and radiographic appearance reflect changes

within the dental pulp, but the long-term impact of

these changes on pulpal health cannot be determined.

A longer study will be required to address these

concerns.

In terms of the periodontal and pulpal outcomes,

extraction of the primary canine followed by ortho-

dontic space opening to encourage the eruption of

the impacted permanent canine appears to be a

satisfactory alternative to surgical exposure and

assisted eruption, providing clinical indications such

as age of the patient and degree of impaction are

taken into account.

Conclusions

Within the limitations of this study, the following

conclusions are reached:

1. Encouraged natural eruption and conservative

surgical exposure with orthodontic alignment have

minor effects on the periodontium.

2. Increased incidence of pulpal changes were

observed in previously impacted canines after both

methods of treatment.

3. As both methods of treatment resulted in similar

periodontal and pulpal outcomes the choice of treat-

ment may depend on clinical indications, the

patients and the orthodontists preferences.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by a grant from the

Australian Society of Orthodontists Foundation for

Research and Education. The authors would like to

thank the orthodontists who were involved in this

study for their assistance with assembling the study

sample and data collection.

Corresponding author

Dr R. J. Olive

141 Queen Street

Brisbane, Qld 4000

Australia

Email: r.h.olive@uq.net.au

References

1. Ericson S, Kurol J. Radiographic examination of ectopically

erupting maxillary canines. Am J Orthod Dentofacial

Orthop 1987;91:48392.

2. Bishara SE. Impacted maxillary canines: a review. Am J

Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 1992;101:15971.

3. McSherry PF. The ectopic maxillary canine: a review. Br J

Orthod 1998;25:20916.

4. Lappin MM. Practical management of the impacted

maxillary cuspid. Am J Orthod 1951;37:76978.

5. Newcomb MR. Recognition and interception of aberrant

canine eruption. Angle Orthod 1959;29:1618.

6. Ericson S, Kurol J. Early treatment of palatally erupting

maxillary canines by extraction of the primary canines. Eur

J Orthod 1988;10:28395.

7. Power SM, Short MB. An investigation into the response of

palatally displaced canines to the removal of deciduous

canines and an assessment of factors contributing to

favourable eruption. Br J Orthod 1993;20:21523.

LING ET AL

Australian Orthodontic Journal Volume 23 No. 1 May 2007 6

8. Becker A. The Orthodontic Treatment of Impacted Teeth.

Martin Dunitz Ltd; 1998.

9. Olive RJ. Orthodontic treatment of palatally impacted

maxillary canines. Aust Orthod J 2002;18:6470.

10. Leonardi M, Armi P, Franchi L, Baccetti T. Two interceptive

approaches to palatally displaced canines: a prospective

longitudinal study. Angle Orthod 2004;74:5816.

11. Wisth PJ, Norderval K, Boe OE. Comparison of two sur-

gical methods in combined surgical-orthodontic correction

of impacted maxillary canines. Acta Odontol Scand 1976;

34:537.

12. Boyd RL. Clinical assessment of injuries in orthodontic

movement of impacted teeth. I. Methods of attachment. Am

J Orthod 1982;82:47886.

13. Woloshyn H, Artun J, Kennedy DB, Joondeph DR. Pulpal

and periodontal reactions to orthodontic alignment of

palatally impacted canines. Angle Orthod 1994;64:25764.

14. Becker A, Kohavi D, Zilberman Y. Periodontal status fol-

lowing the alignment of palatally impacted canine teeth. Am

J Orthod 1983;84:33236.

15. Blair GS, Hobson RS, Leggat TG. Posttreatment assessment

of surgically exposed and orthodontically aligned impacted

maxillary canines. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 1998;

113:32932.

16. Wisth PJ, Norderval K, Boe OE. Periodontal status of ortho-

dontically treated impacted maxillary canines. Angle Orthod

1976;46:6976.

17. Burden DJ, Mullally BH, Robinson SN. Palatally ectopic

canines: closed eruption versus open eruption. Am J Orthod

Dentofacial Orthop 1999;115:6404.

18. Lindauer SJ, Rubenstein LK, Hang WM, Andersen WC,

Isaacson RJ. Canine impaction identified early with

panoramic radiographs. J Am Dent Assoc 1992;123:912,

957.

19. Silness J, Loe H. Periodontal disease in pregnancy.

II. Correlation between oral hygiene and periodontal

condition. Acta Odontol Scand 1964;22:12135.

20. Loe H, Silness J. Periodontal disease in pregnancy.

I. Prevalence and severity. Acta Odontol Scand 1963;21:

53351.

21. Cave SG, Freer TJ, Podlich HM. Pulp-test responses in

orthodontic patients. Aust Orthod J 2002;18:2734.

22. Jacobsen I, Kerekes K. Long-term prognosis of traumatized

permanent anterior teeth showing calcifying processes in the

pulp cavity. Scand J Dent Res 1977;85:58898.

23. Hansson C, Linder-Aronson S. Gingival status after ortho-

dontic treatment of impacted upper canines. Trans Eur

Orthod Soc 1972:43341.

24. Kohavi D, Becker A, Zilberman Y. Surgical exposure, ortho-

dontic movement, and final tooth position as factors in

periodontal breakdown of treated palatally impacted

canines. Am J Orthod 1984;85:727.

SURGICAL AND NON- SURGICAL METHODS OF TREATING PALATALLY IMPACTED CANINES. I - PERIODONTAL AND PULPUL OUTCOMES

Australian Orthodontic Journal Volume 23 No. 1 May 2007 7

Introduction

Despite extensive interest in the aetiology and man-

agement options for ectopic canines, only a few stud-

ies have focussed on the position and colour of the

canines after treatment.

15

The maxillary canine is

situated in a strategic position between the anterior

and posterior segments and has important roles in an

attractive smile and a functional occlusion.

6,7

Early diagnosis and interceptive treatment with

extraction of the overlying primary canines have been

advocated for the management of impacted maxillary

canines.

8,9

In less severe and uncrowded cases this

simple procedure is relatively successful.

10

However, a

recent prospective study of palatally impacted canines

failed to find any difference between the success rates

of impacted maxillary canines treated with extraction

of the overlying primary canines and no treatment.

11

In patients with crowding in the canine region,

between 75 and 80 per cent of palatally impacted

canines will emerge without direct orthodontic assis-

tance if space is created in the upper arch.

11,12

If a

palatally impacted canine fails to erupt following

Australian Orthodontic Journal Volume 23 No. 1 May 2007 8

Comparison of surgical and non-surgical methods

of treating palatally impacted canines.

II - Aesthetic outcomes

Kwok K. Ling,

*

Christopher T. C. Ho,

*

Olena Kravchuk

and Richard J. Olive

School of Dentistry,

*

School of Land and Food Sciences,

University of Queensland and Specialist practice,

Brisbane, Australia

Background: Palatally impacted maxillary canines may appear unsightly after treatment because of changes in position and

colour.

Aim: To determine if palatally impacted canines treated either by surgical exposure and orthodontic repositioning or by creation

of space in the arch and unassisted eruption have different aesthetic outcomes.

Methods: Twenty eight subjects with unilateral palatally impacted canines who had completed orthodontic treatment at least

6 months previously were recruited from three specialist practices. In 14 subjects the canines had been treated by surgical

exposure, orthodontic extrusion and repositioning in the arch (SE group) and in the remainder the deciduous canines were

extracted and excess space created in the arch for the canines to erupt naturally (OT group). The contralateral canines were

used as controls. The mean pretreatment ages of the subjects in the SE and OT groups were 13.5 (SD: 1.6) years and 13.5

(SD: 1.3) years respectively. The position and colour of the canines were assessed on post-treatment study models and 35 mm

slides using the American Board of Orthodontics Objective Grading System (ABO OGS) and subjective appraisal by two

orthodontists. Each subject used a semantic scale to rate the aesthetic outcome of treatment.

Results: Sixty four per cent of the treated canines in the SE group were significantly more intruded than the treated canines

in the OT group (p = 0.004) and the control canines (p = 0.004). The ABO OGS grades of the canines in the SE and OT

groups were similar (p = 0.173). While the assessors detected a lack of labial root torque and gingival margin changes in

the canines in the SE group, the subjects in both groups were satisfied with the appearance of the canines post-treatment.

Conclusions: Palatally impacted canines treated by surgical exposure, extrusion and orthodontic treatment were more likely to

be displaced vertically (intruded) after treatment than palatally impacted canines treated by extraction of the overlying

deciduous canines and creation of excess space in the arch. Small occlusal and aesthetic changes detected by the

orthodontists, but not the ABO OGS, did not appear to detract from the satisfaction of the subjects with the results of

orthodontic treatment.

(Aust Orthod J 2007; 23: 815)

Received for publication: July 2006

Accepted: February 2007

extraction of the overlying primary canine and cre-

ation of excess space in the arch, the most reliable

treatment option is surgical exposure and ortho-

dontic repositioning of the impacted tooth in the

arch.

A reliable and objective method is required to evalu-

ate tooth position following treatment. Previous stud-

ies have relied on assessments by orthodontists, by

other dental professional groups, by the public, and

measuring instruments, such as the American Board

of Orthodontics Objective Grading System (ABO

OGS).

5,1316

The ABO OGS scores eight criteria,

which are considered to provide a reliable and objec-

tive appraisal of tooth position.

16

There have been no

previous reports of the use of the ABO OGS to deter-

mine the stability, or otherwise, of specific traits of

malocclusion. A trained and observant eye may detect

minor deviations in tooth position(s) that patients

may be either unaware of or are satisfied with.

17,18

Patient perception and satisfaction may be assessed

with instruments such as a semantic scale or a

questionnaire.

The principal aim of this retrospective study was to

determine if palatally impacted canines treated either

by surgical exposure and orthodontic repositioning or

by creation of space in the arch and unassisted erup-

tion have different aesthetic outcomes. Additional

aims were to determine if the ABO OGS could be

used to assess the positions of the canines after treat-

ment and to determine if the method of treatment

influenced patient satisfaction.

Material and methods

Ethical clearance for this study was granted by the

Medical Research Ethics Committee of the University

of Queensland. Twenty eight subjects with unilateral

palatally impacted canines who had completed ortho-

dontic treatment at least 6 months previously were

recruited from three specialist practices. In 14 sub-

jects the canines had been treated by surgical

exposure, orthodontic extrusion and repositioning in

the arch (SE group) and in the remainder, the decid-

uous canines were extracted and excess space created

in the arch for the canines to erupt naturally (OT

group). Subjects were selected if they met the

following criteria:

1. A unilateral palatally impacted canine was present.

2. A pretreatment panoramic radiograph was

available.

3. There was no significant medical history.

4. Treatment had been completed at least six months

previously.

5. In the surgical group, the subjects had undergone

conservative surgical exposure and the wound had

been dressed for 710 days before any orthodontic

attachments were bonded.

The 14 subjects (5 males, 9 females) in the OT group

had a mean age of 19.1 (SD: 2.2) years and the mean

post-treatment period was 3.4 (SD: 3.0) years. The

same orthodontist treated all subjects in the OT

group. The 14 subjects (2 males, 12 females) in the

SE group had a mean age of 18.8 (SD: 2.5) years and

the mean post-treatment period was 3.2 (SD: 2.4)

years (Table I). Three orthodontists treated the sub-

jects in the SE group. The pretreatment panoramic

radiographs were used to classify the sector of

impaction using Lindauer et al. modification

19

of

Ericson and Kurols classification.

9

No sector I

impacted canines were included in the study.

DIFFERENT METHODS OF TREATING PALATALLY IMPACTED CANINES. II - AESTHETIC OUTCOMES

Australian Orthodontic Journal Volume 23 No. 1 May 2007 9

Table I. Description of the sample.

OT (N=14) SE (N=14) p

p

+

Mean SD Mean SD

Male : Female 5 : 9 2 : 12 0.190

Right : Left proportion 8 : 6 4 : 10 0.127

Sector of impaction II : III : IV 5 : 7 : 2 1 : 4 : 9 0.019

Age at start of treatment (years) 13.5 1.3 13.5 1.6 0.979

Age at recall (years) 19.1 2.2 18.8 2.5 0.749

Active treatment duration (months) 27.9 9.3 28.4 7.5 0.877

Recall period (years) 3.4 3.0 3.2 2.4 0.847

Chi-squared test, significant value in bold

+ Students t - test

American Board of Orthodontics Objective

Grading System

All subjects had a wax occlusal record and alginate

impressions of both arches taken at the post-

treatment assessment. The resulting study models

were scored by a single examiner (KKL) with no prior

knowledge of the side of impaction or the method of

treatment. The alignment, marginal ridges, bucco-

lingual inclinations, interproximal contacts, overjet,

occlusal contacts and occlusal relationships of the

teeth were assessed with the ABO OGS and the

standardised measuring gauge. Root angulations were

not assessed because post-treatment panoramic radio-

graphs were not available. For each criterion, points

were assigned based on the degree to which a

relationship deviated from ideal. The individual com-

ponents were scored and summed to yield an overall

score. To assess intra-examiner reliability the ABO

OGS scoring was repeated one week later.

Canine position and dental midline

The positions of both maxillary canines in each sub-

ject in relation to the adjacent teeth and the upper

and lower dental midlines were analysed on the

dental casts by one examiner. Intrusions, rotations

and palatal translations were recorded as present or

absent. Canines were classified as intruded when

there was no inter-arch contact or the height differ-

ence between the canines and adjacent teeth was

greater than one millimetre. A rotation was recorded

if a tooth was rotated more than five degrees. A

canine was in palatal translation if the buccal overjet

was reduced by more than one millimetre, if the

tooth was in edge-to-edge relationship or in lingual

cross-bite. The upper and lower dental midlines were

measured with digital callipers.

Canine colour and side of impaction

Two independent orthodontists (Assessor A and

Assessor B) subjectively assessed the colour of the

maxillary canines on projected 35 mm Kodachrome

slides of the frontal smile, the anterior occlusal view

and the upper occlusal view. The slides were taken at

standardised settings with the same camera at the

post-treatment assessments. The assessors were

unaware of the side of impaction and method of

treatment. They were asked to assess the colour of

both canines and to identify the side of impaction

from the dental casts and colour slides.

Questionnaire

Subject satisfaction with the overall appearance of the

canines, colour of the canines, colour of the lateral

incisors and position of the canines were evaluated by

questionnaire. The subjects were asked to rate their

satisfaction with each of the four characteristics on a

5 point scale. The scale was anchored with the

descriptors, very satisfied and very dissatisfied.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was carried out with Minitab for

Windows (Release 14, Minitab Inc., USA) and the

level of significance for all statistical procedures was

set at 5 per cent. Additionally, SPSS for Windows

(Version 12.0, SPSS Inc., Chicago, USA) was used to

perform the McNemar test. The Bonferroni correc-

tion was applied when appropriate. The age of the

subjects at commencement of active treatment, ages

at recall, the durations of treatment and the post-

treatment follow-up periods in the groups were

compared with Students t-tests. Chi-squared tests

were used to determine if there were different pro-

portions of subjects in the impaction sectors in the SE

and OT groups. The durations of treatment carried

out by the three orthodontists were examined with

the one-way analysis of variance. Post-hoc Tukey tests

were used to test the differences between pairs of

orthodontists.

Intra-observer duplication error for the ABO OGS

overall score was tested with the paired t-test. Overall

ABO OGS scores were analysed for the two treat-

ment groups. A one-way ANOVA was used to check

for a difference in ABO OGS scores between ortho-

dontists. Attribute agreement analysis (Cohens

Kappa) was used to examine the intra-examiner relia-

bility in determination of deviation from an ideal

canine position. As the results indicated a high degree

of reliability (Kappa: 0.65-1), either the initial or the

second set of measurements was chosen randomly to

be tested with Fishers Exact test for differences in the

proportions of canine intrusion, rotation and palatal

displacement in the groups. Comparison within each

group (palatally impacted canine versus the contra-

lateral canine) was tested with McNemar tests.

Differences in midline deviations between OT and

SE groups were tested with the Mann-Whitney U test.

Inter-examiner agreement for canine colour and iden-

tification of a previously palatally impacted maxillary

LING ET AL

Australian Orthodontic Journal Volume 23 No. 1 May 2007 10

canine from dental casts and colour slides were

analysed using attribute agreement analysis and

Cohens Kappa. The inter-examiner agreement was

low. Thus, results from each orthodontist assessor

were analysed separately with Fishers Exact test.

Ordinal data from the questionnaires assessing

patient satisfaction were analysed with the Mann-

Whitney U test.

Results

The results are given in Tables IVI and Figures 13.

There were significantly more sector IV canines in the

SE group and the durations of active treatment of the

three orthodontists were significantly different

(Tables I and II). The post-hoc Tukey test disclosed

that Orthodontist A took significantly longer than

Orthodontists B and C to complete treatment, but

there was no difference in the time taken by Ortho-

dontists B and C to complete treatment (Table II).

The scatter plot of the treatment duration versus age

at the commencement of treatment did not indicate

any relationship between the two variables (Figure 1).

Approximately 41 per cent of the variability in treat-

ment time of the subjects in the SE group was

accounted for by age at the commencement of treat-

ment and the orthodontist providing the treatment

(SE group: r-square, 40.68 per cent).

There was no statistically significant difference

between the two sets of ABO OGS overall scores

(p = 0.224). The first set of scores were used for

further analysis. When the distribution of the ABO

OGS overall scores was examined, nine subjects in

the OT group (64 per cent) and six subjects in the SE

group (43 per cent) had overall scores greater than 30

and failed to meet the treatment standards of the

DIFFERENT METHODS OF TREATING PALATALLY IMPACTED CANINES. II - AESTHETIC OUTCOMES

Australian Orthodontic Journal Volume 23 No. 1 May 2007 11

Table II. Duration of active treatment.

Treatment duration (Months) p

Mean SD Range

Orthodontist A

(N=3) 37.67 (4.16)

a

3341

Orthodontist B

N=8) 28.13 (5.08)

b

2136

Orthodontist C

(N=3) 20.00 (5.00)

b

1525

0.004

Different letters in the Mean (SD) column indicate a significant

difference

One-way ANOVA, significant value in bold

Figure 1. Treatment duration versus age at the commencement of active

treatment.

Table III. Frequency of intrusion, rotation and palatal translation of previously impacted canines (PIMC).

Intrusion Rotation Palatal translation

PIMC Control p

+

PIMC Control p

+

PIMC Control p

+

OT (N=14) 1 0 1.000 4 0 0.125 1 1 1.000

SE (N=14) 9 0 0.004 8 1 0.039 4 0 0.125

p

0.004 1.000 0.252 1.000 0.326 1.000

Significant values in bold

Fishers Exact test

+

McNemar test

Table IV. Discolouration of impacted canines reported by two

orthodontists.

OT (N=14) SE (N=14) p

Assessor A 2 5 0.190

Assessor B 1 1 1.000

Chi-squared test

Treatment commencement age (Years)

T

r

e

a

t

m

e

n

t

d

u

r

a

t

i

o

n

(

M

o

n

t

h

s

)

Ortho/Surgical

OT

SE

ABO. The ABO OGS scores for the OT (Mean:

39.9; SD:14.7) and SE (Mean: 32.6; SD:13.0)

groups were not significantly different (p = 0.173).

There were no significant differences between the

overall scores for the patients in the SE group treated

by each of the three orthodontists. The mean overall

ABO OGS scores for orthodontists A, B and C were

22.83, 36.88 and 30.83 respectively.

The number of previously impacted and control

(contralateral) canines that were intruded, rotated

and/or palatally placed in the OT and SE groups are

given in Table III. Nine out of 14 treated canines (64

per cent) in the SE group were intruded. Of the

treated canines more teeth were intruded in the SE

group compared with the OT group (p = 0.004) and

the control canines (p = 0.004). The latter finding

was statistically significant after the Bonferroni

correction had been applied. In the SE group more

treated canines were rotated at recall than control

canines (p = 0.039). There was no significant differ-

ence in midline deviations in the OT (Mean: 0.40

mm) and SE (Mean: 0.66 mm) groups. The

maximum midline deviations in the OT and SE

groups were 2.58 mm and 1.58 mm respectively

(Figure 2).

There were no significant inter-group differences in

the colour of the previously impacted teeth (Table

IV). Assessor A correctly identified 11 previously

impacted canines in the OT group and 12 teeth the

SE group (Table V). Assessor B was uncertain in eight

(57 per cent) cases in the OT group and two cases in

the SE group (14 per cent). Assessor B correctly iden-

tified five cases in the OT group and 12 cases in the

SE group. Both assessors used differences in inclina-

tion and the appearance of the labial and palatal

gingival contours to identify previously impacted

canines.

The subjects were generally satisfied or very satis-

fied with the colour and positions of the treated

canines. Only one subject in the OT group chose

very dissatisfied as the response to the question

about overall appearance. Similarly, the majority of

subjects were satisfied or very satisfied with the

colour of the lateral incisors and only one subject

from each group was dissatisfied. There were no sig-

nificant differences between the OT and SE groups to

the questions relating to overall satisfaction, colour of

the lateral incisors, colour and position of previously

impacted maxillary canines (Table VI). There was

also no significant difference between the OT and SE

LING ET AL

Australian Orthodontic Journal Volume 23 No. 1 May 2007 12

Figure 2. Individual post-treatment dental midline deviation. Figure 3. Overall ABO OGS score versus total satisfaction score.

A high score indicates a poor occlusal outcome and a low score greater

satisfaction.

Table V. Identification of previously impacted canines by two orthodontists.

OT (N=14) SE (N=14)

Incorrect Correct Uncertain Incorrect Correct Uncertain

Assessor A 3 11 0 2 12 0

Assessor B 1 5 8 0 12 2

Ortho/Surgical

Total satisfaction score

D

e

n

t

a

l

m

i

d

l

i

n

e

d

e

v

i

a

t

i

o

n

(

m

m

)

A

v

e

r

a

g

e

o

v

e

r

a

l

l

A

B

O

O

G

S

s

c

o

r

e

Ortho/Surgical

OT

SE

95% CI for the mean

groups when the scores of the four questions were

combined (p = 0.448). Finally, there was no signifi-

cant correlation between the combined satisfaction

scores and the ABO OGS scores (Figure 3).

Discussion

We set out to determine if palatally impacted canines

surgically exposed and repositioned in the arch had

better crown colour and position than canines per-

mitted to erupt naturally after excess space had been

created in the maxillary arch. Although the clinicians

were able to identify small variations in the positions

of the canines that the ABO OGS could not pick up,

the subjects were generally very satisfied with the out-

come.

The main limitation in this study is related to the

method of sampling. In this study, consecutively

treated patients fitting the inclusion criteria were

retrospectively identified and invited to participate.

The participation rate was only 58 per cent, which

resulted in a relatively small sample. Bias due to satis-

fied patients being more likely to participate in the

study cannot be eliminated. Another problem relat-

ing to the small sample size is the possibility of

having a Type II error, so that the null hypothesis is

wrongly accepted due the inability to detect a differ-

ence. The probability of a Type II error decreases as

the sample size increases. While the best strategy is to

obtain the largest possible sample, this was not pos-

sible because of the low participation rate.

20

A future

prospective study would be able to address some of

these concerns. There are also recognised objections

to the validity of findings from questionnaires, since

some respondents might have been inclined to select

the perceived right answer and selecting a suitable

answer format inevitably inhibits free expression.

21

Hence, the findings from the patient satisfaction

survey in this study may be optimistic.

Ideal alignment in the present study was 71 per cent

in the OT group and 14 per cent in the surgical

group. The result from the surgical group was much

lower than reported in the literature, which ranges

from 4048 per cent.

2,3,5

The differences between the

studies may be due to the differences in the criteria

for determining rotation, intrusion and palatal trans-

lation. Generally, it is accepted that some degree of

relapse is inevitable,

25

but the changes found in this

study were surprising. In the SE group, the previ-

ously impacted canines were intruded in nine subjects

(64 per cent) and rotated in eight subjects (57 per

cent). These are much higher proportions than in the

OT group or on the control sides in both groups.

Palatal displacement was a marginally less frequent

finding with four subjects (29 per cent) in the SE

group affected. Even though four subjects (29 per

cent) in the OT group presented with rotation of

previously impacted canines, palatal displacement

and intrusion rarely occurred in this group.

A concern with the technique of allowing an

impacted canine to erupt naturally is that a residual

DIFFERENT METHODS OF TREATING PALATALLY IMPACTED CANINES. II - AESTHETIC OUTCOMES

Australian Orthodontic Journal Volume 23 No. 1 May 2007 13

Table VI. Subject satisfaction post-treatment.

Very satisfied Satisfied Dont know Not satisfied Very dissatisfied p

Overall appearance OT 6 7 0 0 1

(Impacted canines) SE 6 8 0 0 0

0.872

Colour (PIMC) OT 5 8 0 1 0

(Impacted canines) SE 2 12 0 0 0

0.505

Colour - lateral OT 5 8 0 1 0

incisors SE 2 7 4 1 0

0.108

Position OT 5 7 1 1 0

(Impacted canines) SE 5 8 1 0 0

0.836

Mann-Whitney U test

dental midline deviation may persist post-treatment.

The technique involves the creation of excess space of

up to 10 mm and may require proclination and

displacement of the maxillary incisors across the mid-

line. Investigation of midline deviations yielded no

significant difference between the groups.

The ABO OGS found the scores for both groups

were similar, implying a similar standard of finishing

or amount of relapse. However, the scores did not

agree with the clinical assessment. The main reason

for the failure to detect a difference could be related

to the method of scoring the models. The full ABO

OGS sums the discrepancies in all criteria and it is

not sensitive enough to detect a small departure from

the ideal position, and it is not designed to assess the

positional deviation(s) of an impacted canine.

One of the factors that may influence the occlusal

outcome is the duration of active orthodontic treat-

ment.

22,23

In the present study there was no signifi-

cant difference between the groups in the duration of

treatment. The mean duration of treatment in the SE

group was 28 months and was comparable with other

studies where active eruption was used following

surgical exposure.

3,24

There was no colour difference between the canines

in the two groups. It was not possible to determine

the incidence of discolouration because of the poor

agreement between the assessors. Identification of

previously impacted canines by the two assessors also

showed poor agreement, although they were more

likely to correctly identify a previously impacted

canine in the SE group than in the OT group. The

lesser amount of relapse in the OT group may have

made identification of a previously impacted canine

difficult.

There was a high level of patient satisfaction follow-

ing both methods of treatment. Only one subject

from the OT group expressed dissatisfaction with

treatment, but this was not correlated with the

occlusal outcome, as demonstrated by the ABO OGS

score for this subject. Clustering of the satisfaction

scores in this study into a narrow range, irrespective

of the ABO OGS scores, indicates satisfaction was not

dependent on or correlated with occlusal outcome

(Figure 3). Overall, palatally impacted canines cor-

rected by extraction of the overlying primary canine and

orthodontic space opening showed better alignment

and less relapse than canines managed with surgical

exposure, extrusion and orthodontic alignment.

Conclusions

1. Palatally impacted canines treated by surgical

exposure, extrusion and orthodontic treatment were

more likely to relapse vertically than those treated by

extraction of the overlying deciduous canines and

creation of excess space in the arch.

2. The ABO OGS failed to detect small changes in

the positions of the canines in both groups.

3. There were no colour differences between the pre-

viously impacted canines in the two groups. The

assessors correctly identified high percentages of pre-

viously impacted canines in the surgical group, but

not the non-surgical group.

4. The subjects in both groups were satisfied with the

outcome of treatment.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by a grant from the

Australian Society of Orthodontists Foundation for

Research and Education. The authors would like to

thank the orthodontists who were involved in this

study for their assistance with assembling the sample

and collecting the data.

Corresponding author

Dr R. J. Olive

141 Queen Street

Brisbane, Qld 4000

Australia

Email: r.h.olive@uq.net.au

References

1. Bennett JC, McLaughlin PP. Orthodontic management of

the dentition with the preadjusted appliance. Isis Medical

Media Ltd.; 1997.

2. Becker A, Kohavi D, Zilberman Y. Periodontal status fol-

lowing the alignment of palatally impacted canine teeth. Am

J Orthod 1983;84:3326.

3. Woloshyn H, Artun J, Kennedy DB, Joondeph DR. Pulpal

and periodontal reactions to orthodontic alignment of

palatally impacted canines. Angle Orthod 1994;64:25764.

4. Blair GS, Hobson RS, Leggat TG. Posttreatment assessment

of surgically exposed and orthodontically aligned impacted

maxillary canines. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 1998;

113:32932.

5. DAmico RM, Bjerklin K, Kurol J, Falahat B. Long-term

results of orthodontic treatment of impacted maxillary

canines. Angle Orthod 2003;73:2318.

6. Bishara SE. Clinical management of impacted maxillary

canines. Semin Orthod 1998;4:8798.

7. Karpagam S, Chacko RK. Guidelines for management of

impacted canines. Indian J Dent Res 2004;15:4853.

LING ET AL

Australian Orthodontic Journal Volume 23 No. 1 May 2007 14

DIFFERENT METHODS OF TREATING PALATALLY IMPACTED CANINES. II - AESTHETIC OUTCOMES

Australian Orthodontic Journal Volume 23 No. 1 May 2007 15

8. Ericson S, Kurol J. Radiographic examination of ectopically

erupting maxillary canines. Am J Orthod Dentofacial

Orthop 1987;91:48392.

9. Ericson S, Kurol J. Early treatment of palatally erupting

maxillary canines by extraction of the primary canines. Eur

J Orthod 1988;10:28395.

10. Power SM, Short MB. An investigation into the response of

palatally displaced canines to the removal of deciduous

canines and an assessment of factors contributing to

favourable eruption. Br J Orthod 1993;20:21523.

11. Leonardi M, Armi P, Franchi L, Baccetti T. Two interceptive

approaches to palatally displaced canines: a prospective lon-

gitudinal study. Angle Orthod 2004;74:5816.

12. Olive RJ. Orthodontic treatment of palatally impacted max-

illary canines. Aust Orthod J 2002;18:6470.

13. Scott SA, Freer TJ. Visual application of the American

Board of Orthodontics grading system. Aust Orthod J 2005;

21:5560.

14. Shaw WC, Richmond S, OBrien KD, Brook P, Stephens

CD. Quality control in orthodontics: indices of treatment

need and treatment standards. Br Dent J 1991;170:10712.

15. Tang EL, Wei SH. Recording and measuring malocclusion: a

review of the literature. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop

1993;103:34451.

16. Casko JS, Vaden JL, Kokich VG, Damone J, James RD,

Cangialosi TJ et al. Objective grading system for dental casts

and panoramic radiographs. American Board of Ortho-

dontics. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 1998;114:

58999.

17. Miller CJ. The smile line as a guide to anterior esthetics.

Dent Clin North Am 1989;33:15764.

18. Kokich VO, Jr., Kiyak HA, Shapiro PA. Comparing the per-

ception of dentists and lay people to altered dental esthetics.

J Esthet Dent 1999;11:31124.

19. Lindauer SJ, Rubenstein LK, Hang WM, Andersen WC,

Isaacson RJ. Canine impaction identified early with

panoramic radiographs. J Am Dent Assoc 1992;123:912,

957.

20. Rinchuse DJ, Sweitzer EM, Rinchuse DJ, Rinchuse DL.

Understanding science and evidence-based decision making

in orthodontics. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 2005;

127:61824.

21. Shaw WC, Gbe MJ, Jones BM. The expectations of ortho-

dontic patients in South Wales and St Louis, Missouri. Br J

Orthod 1979;6:2035.

22. Lobb WK, Ismail AI, Andrews CL, Spracklin TE. Evaluation

of orthodontic treatment using the Dental Aesthetic Index.

Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 1994;106:705.

23. Dyken RA, Sadowsky PL, Hurst D. Orthodontic outcomes

assessment using the peer assessment rating index. Angle

Orthod 2001;71:1649.

24. Iramaneerat S, Cunningham SJ, Horrocks EN. The effect of

two alternative methods of canine exposure upon subsequent

duration of orthodontic treatment. Int J Paediatr Dent

1998;8:1239.

Introduction

Orthodontic alignment of overlapped incisors can

reduce the apparent heights of the interdental papil-

lae leading to unsightly dark triangles or open

gingival embrasures.

13

It has been suggested that as

overlapped teeth are aligned the interdental papillae

stretch, their heights reduce and open gingival

embrasures develop.

13

Other factors, such as alveolar

bone levels, crown form, contact relationships, pre-

treatment crowding,

46

age,

7

and orthodontic effects

on the gingival fibres may also play a part in the

causation of open gingival embrasures or dark tri-

angles. Recently, Ko-Kimura et al.

8

and Ikeda et al.

9

reported that open gingival embrasures were associ-

ated with resorption of the alveolar crest, and were

more frequently found in patients over 20 years of

age.

Two factors believed to influence the form of the gin-

gival tissues post-treatment are the direction of tooth

movement and the faciolingual thickness of the sup-

porting bone and soft tissue.

10

For example, during

lingual or palatal tooth movement the gingival tissue

on the facial aspect of a tooth thickens and migrates

occlusally. The reverse may occur when teeth are

moved labially.

1113

Providing a tooth is moved with-

in the alveolar process the risk of gingival recession is

Australian Orthodontic Journal Volume 23 No. 1 May 2007 16

Changes in interdental papillae heights following

alignment of anterior teeth

Sanjivan Kandasamy,

*

Mithran Goonewardene

*

and Marc Tennant

Dental School, The University of Western Australia

*

and the Centre for Rural and Remote Oral Health, The University of Western Australia,

Perth, Australia

Background: Orthodontic alignment of overlapped incisors can reduce the apparent heights of the interdental papillae leading

to unsightly dark triangles or open gingival embrasures.

Aim: To determine if certain pretreatment contact point relationships between the maxillary anterior teeth were accompanied by

changes in the heights of the interdental papillae after orthodontic alignment.

Methods: Pre- and post-treatment intra-oral 35 mm slides, lateral cephalometric radiographs and study casts of 143 patients

(60 males, 83 females) between 13 and 16 years of age were used. The patients had diastamata closed, imbricated teeth

aligned and palatally or labially placed teeth repositioned. A sample of 25 patients (12 males, 13 females) between 13 and

16 years of age who had well-aligned anterior teeth at the start of treatment acted as a control group. All patients were

treated for approximately 18 months. The clinical crowns of the maxillary incisors and the heights of the interdental papilla

between the incisors were measured on projected images of the slides. The percentage increases or reductions in the heights of

the interdental papillae were compared.

Results: The heights of the interdental papillae increased following palatal movement of labially placed (p < 0.05) or

imbricated (p < 0.05) incisors and the intrusion of one incisor relative to an adjacent incisor (p < 0.01). The heights of the

interdental papillae reduced following labial movement of an imbricated (p < 0.05) or palatally placed (p < 0.05) incisor or

closure of a diastema (p < 0.01). Before treatment the midline papillae in the diastema subgroup were of similar length to the

midline papillae in the control group, but after treatment they were markedly shorter. The interdental papillae associated with

crowded or imbricated incisors were shorter than the interdental papillae in the control group before and after treatment.

Conclusions: Dark triangles are less likely to develop following palatal movement of labially placed or imbricated teeth and the

intrusion of one tooth relative to another. On the other hand, dark triangles are more likely to develop following labial move-

ment of imbricated or palatally placed incisors and closure of a diastema. Clinicians should be alert to the possibility of dark

triangles developing in the latter group, particularly in older patients.

(Aust Orthod J 2007; 23: 1623)

Received for publication: July 2006

Accepted: January 2007

minimal, irrespective of the dimensions or quality of

the gingival tissue.

14

The aim of this study was to determine if certain pre-

treatment contact point relationships between the

maxillary anterior teeth were accompanied by

changes in the heights of the interdental papillae after

orthodontic alignment.

Materials and methods

Ethical approval for this study was obtained from the

Human Research Ethics Committee of the University

of Western Australia. All assessments were carried out

in accordance with the guidelines of the National

Health and Medical Research Council of Australia.

All patients who commenced treatment in a private

orthodontic practice in 1996 and required alignment

of the upper anterior teeth were eligible for the study.

Patients with poor oral hygiene exhibiting swollen,

erythematous and/or hyperplastic gingivae, with

incomplete records and when two or more of the

contact relationships given in Table I were present,

were excluded. Patients with the latter condition were

excluded because the interdental papilla between the

teeth could be influenced differently by the different

tooth movements required to align the teeth. A total

of 143 patients (60 males, 83 females) between 13

and 16 years of age (Mean age: 14 years 7 months)

were available for the experimental group. A sample

of 25 patients (12 males, 13 females) who received

orthodontic treatment in the same practice, but

who had well aligned anterior teeth at the start of

treatment acted as a control group. These patients

were also between 13 and 16 years of age (Mean age:

14 years 4 months).

Pre- and post-treatment intra-oral 35 mm slides,

lateral cephalometric radiographs and study casts

were used. The intra-oral frontal photographs were

taken at the same magnification and standardised by

positioning the upper midline in the centre of the

view finder and sighting along the occlusal plane. All

patients were treated for approximately 18 months

and the post-treatment photographs were taken four

weeks after appliance removal. The pre- and post-

treatment lateral cephalometric radiographs were

used to assess qualitatively the overall direction of

maxillary incisor movement. The study models were

used to determine the arrangement of the anterior

teeth and allocation into the groups given in Table I.

The clinical crowns (incisal edge lowest point on

the gingival margin) of the central and lateral incisors

and the heights of the interdental papillae between

the incisors (tip of an interdental papilla to the line

joining the lowest points on the gingival margins of

adjacent incisors) were measured twice on standard-

ised images of the slides projected onto a white back-

ground (Figure 1). The maxillary incisors in both

experimental and control groups were measured.

Because it was not possible to measure the inter-

dental and crown heights precisely if adjacent teeth

were at different inclinations or displaced palatally/

labially, and pretreatment measurements of the

cemento-enamel junction gingival margin distances

CHANGES IN INTERDENTAL PAPILLAE HEIGHTS FOLLOWING ALIGNMENT OF ANTERIOR TEETH

Australian Orthodontic Journal Volume 23 No. 1 May 2007 17

Table I. Definitions.

Relationship Definition

Diastema The horizontal space between

adjacent incisors

Vertical discrepancy Adjacent incisors in different vertical

positions

Imbricated Incisors arranged in an overlapping

manner, one incisor may be palatally

or labially placed relative to the other

incisor

Labially or palatally Labially or palatally placed incisors.

placed incisors with Study models and lateral intraoral

no overlap photographs were used to determine

if an incisor was imbricated or

labially/palatally placed.

Figure 1. Crown height was measured from the incisal edge to the highest

point on the gingival margin. Interdental papilla height was measured from

the tip of an interdental papilla to the line joining the highest points on the

gingival margins of adjacent incisors.

were not available, the data were converted to per-

centages. The percentage loss or gain in the height of

an interdental papilla(e) were obtained by dividing

the mean height of the interdental papilla(e) by the

mean length of the clinical crowns of the incisors on

either side of the papilla(e) and converting the result

to a percentage. The mean pre- and post-treatment

percentage values were then used to obtain the

percentage increases or reductions.

The statistical analyses were performed using the

Intercooled Stata 8.0 statistical package (SPSS,

Chicago, Illinois, USA). Values of p less than 0.05

were considered significant. All measurements were

repeated by the same examiner two weeks later.

Results of the paired t-test showed there were no

significant differences at the 5 per cent level of signif-

icance between the first and second sets of measure-

ments. To improve the reliability of these measure-

ments the means of both sets of measurements were

used in all subsequent calculations.

Results

The results are given in Table II and Figures 27.

Control group

The mean pre- and post-treatment heights of the

interdental papillae in the control group were 45.6

and 47.1 per cent respectively. The difference

between the pre- and post-treatment heights was not

statistically significant.

Experimental group

Diastema

The diastemata were closed in 28 patients (Table II,

Figure 2). Following closure of diastemata the inter-

dental papillae between the central incisors were

significantly shorter at the end of treatment (Mean

difference: -10.5 per cent; p < 0.01). The post-

treatment heights of the interdental papillae in the

experimental sample were also significantly shorter

than the post-treatment heights of the interdental

papillae in the control group (Mean difference: -9.1

per cent; p < 0.01).

Vertical discrepancy

Before treatment the heights of the interdental papil-

lae in this group were significantly shorter than the

pretreatment heights of the interdental papillae in

the control group (Mean difference: -10.2 per cent;

p < 0.01). The control experimental difference after

treatment was not significant. Following correction of

a vertical discrepancy the interdental papillae

increased in height significantly (Mean difference: 8.1

per cent; p < 0.01). Pre- and post-treatment views of

a typical case are shown in Figure 3.

KANDASAMY ET AL

Australian Orthodontic Journal Volume 23 No. 1 May 2007 18

Table II. Pretreatment and post-treatment comparisons.

Group N Mean Pretreatment p Mean Intra-group p Post-treatment p

pretreatment difference post-treatment change difference

height E minus C height (Per cent) E minus C

(Per cent) (Per cent) (Per cent) (Per cent)

Control 25 56.6 (8.1) 47.1 (8.1) 1.5 NS

Diastema 28 48.5 (7.5) - 2.9 NS 38.0 (8.8) -10.5 0.01 -9.1 0.01

Vertical 31 35.4 (8.6) -10.2 0.01 43.5 (7.7) 8.1 0.01 -3.6 NS

discrepancy

Labially 11 34.6 (7.8) -11.0 0.01 45.1 (9.6) 10.5 0.01 -2.0 NS

overlapped

Palatally 25 43.3 (7.8) -2.3 NS 41.0 (6.1) -2.3 NS -6.1 0.01

overlapped

Labially 10 31.0 (8.3) -14.6 0.01 38.9 (8.6) 7.9 0.01 -8.2 0.05

placed