Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Theory: of Architecture

Theory: of Architecture

Uploaded by

reacharunk0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

10 views1 pageThis document discusses experiments conducted to understand the friction between solid objects like stones of varying sizes and weights. It finds that heavier stones experience less friction than lighter ones, and that the roughness of stone surfaces increases friction. When small stone blocks were placed between larger blocks and on a stone plane, the smaller block was able to be supported by friction alone between the surfaces. This supported the hypothesis that a 30 degree inclined plane is equivalent to a horizontal plane for sustaining stone blocks like those in arches, due to surface friction overcoming irregularities between the stones.

Original Description:

ljljljljl

Original Title

EN(380)

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentThis document discusses experiments conducted to understand the friction between solid objects like stones of varying sizes and weights. It finds that heavier stones experience less friction than lighter ones, and that the roughness of stone surfaces increases friction. When small stone blocks were placed between larger blocks and on a stone plane, the smaller block was able to be supported by friction alone between the surfaces. This supported the hypothesis that a 30 degree inclined plane is equivalent to a horizontal plane for sustaining stone blocks like those in arches, due to surface friction overcoming irregularities between the stones.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Download as pdf or txt

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

10 views1 pageTheory: of Architecture

Theory: of Architecture

Uploaded by

reacharunkThis document discusses experiments conducted to understand the friction between solid objects like stones of varying sizes and weights. It finds that heavier stones experience less friction than lighter ones, and that the roughness of stone surfaces increases friction. When small stone blocks were placed between larger blocks and on a stone plane, the smaller block was able to be supported by friction alone between the surfaces. This supported the hypothesis that a 30 degree inclined plane is equivalent to a horizontal plane for sustaining stone blocks like those in arches, due to surface friction overcoming irregularities between the stones.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Download as pdf or txt

You are on page 1of 1

358

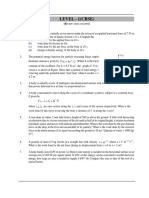

THEORY OF ARCHITECTURE. Book II

that necessary to makt' it slide, and, reciprocally, it will be overtv Jcd when less force i>

necessary to ])rodiice tliat eflect than to make it slide.

1366. II. When tlie parallelopiped is placed on an inclined plane, it will slide so long

as the vertical QS drawn from its centre of gravity does not fall without the base Ali.

Hence, to ascertain whether a parallelopiped A13CD with a

rectangular base

(^fig.

564.)

will slide down or overturn

;

from

the ])oiiit B we must raise the perpendicular BE : if it pass out

of tlie centre of gravity, it will slide ; if, on the contrary, the

line BE passes within, it will overturn.

1367. If the surfaces of stones were infinitely smooth, as

they are supposed to be in the application of the principles of

'Fir.

sci.

mechanics, they would begin to slide the moment the plane

upon which they are placed ceases to be perfectly horizontal

;

but as their surfaces are full

of little inequalities which catch one another in their positions, llondelet found, by re-

peated experiments, that even those whose surfaces are wrought in the best manner do not

begin to slide u])on the best worked planes of similar stone to the solids until such planes

are inclined at angles varying from 28 to .36 degrees. This difficulty of moving one stone

upon another increases as the roughness of their surfaces, and, till a certain point, as their

weight: for it is manifest, 1st, That the rougher their surfaces, the greater are the in-

equalities which catch one another. 2d. That the greater their weight, the greater is the

ertbrt necessary to disengage them

;

but as these inequalities are susceptible of being

broken up or bruised, the maximimi of force wanting to overcome the friction must be

equal to that which produces this effect, whatever the weight of the stone. 3d. That this

proportion is rather as the hardness than the weight of the stone.

1 :568. In experiments on the sliding of hard stones of ditVerent sizes which weighed from

2 to 60 lbs., our author found that the friction which was more than half the weight

for the smaller was reduced to a third for the larger. He remarked that after each experi-

ment made with the larger stones a sort of dust was disengaged bj tlie friction. In soft

stones this dust facilitated the sliding.

1.369. These circumstances, which would have considerable influence on stones of a great

weight, were of little importance in the experiments whifli will be cited, the object being

to verify upon hard stones, whose mass was small, the result of operations which the tlieory

was expected to confirm. By many exi)erinients very carefully made upon hard freestone

well wrouglit and squared, it was found, 1st, That they did not begin to slide upon a ])lane

of the same material equally well wrought until it was incliiiea a little more than 30 degrees.

2d. Tliat to drag upon such stone a parallelopiped of the same material, a little more than

half its weight was required. Thus, to drag upon a level plane a paruUelopiped 6 in. long,

4 in. wide, and 2 in. thick, weighing 4 lbs. lloz., (the measures and weights are French,

ES throughout*), it was necessary to employ a weight etjual to 2 lbs. 7 oz. .and 4 drs.

3d. That the size of the rubbing surface is of no couseciuence, since exactly the same force

is necessary to move this parallelojiiped upon a face of two in. wide as ujiou one of 4.

1370. Taking then into consideration that by the principles of mechanics it is proved,

that to raise a perfectly smooth body, or one which is round u])on an homogeneous j)lane

inclined at an angle of 30 degrees, a jiower must be employed parallel to the plane which

acts with a force rather greater than half its weight, we may conclude that it reipiires as

much force to drag a parallelopiped of freestone ujion an horizontal plane of the same

material as to cause the motion up an inclined plane of 30 degrees of a round or infinitely

polished body.

1 .371. From these considerations in applying the jirinciples of mechanics to arches composed

of freestone well wrought, a plane inclined at 30 degrees might be considered as one upon

which the voussoirs would be sustained, or, in other words, e(juivalent to an iiorizontal plane.

1372. We shall here submit another experiment, which tends to establish such an hy])o.

thesis. If a parallelopiped C

{fig.

565.) of this stone be placed

between two others, BD, IIS, whose masses are each double,

upon a plane of the same stone, the parallelopiped C is sus-

tained by the frictiju alone of the vertical surfaces that touch

it. This effect is a consetjuence of our hypothesis

;

for, the

inequalities of the surfaces of bodies being stopped by one ano-

ther, the parallelopiped C, before it can fall, must push aside the

two others, BD, US, by making them slide along the horizontal

plane of the same material, and for that purpose a force must be employed ecjual to cIouIki

the weight sustained.

*

The Paris pound = T^fil Troy grains.

Ounce = 47'2"')'i25.

Dram or gros = .')9l)703.

CtMW ~ 0-8-2Ot.

And as thii KiiRlish avoirdupois pound = 70(10 Troy grains, it contiiins H538 I'aris grain*

The I'iiris foot of 12 iiiclies = 12-7977 KMslish inc-hrs.

1 he Pdi is line

i^ one-l*i''th of the loot.

You might also like

- Fyodor Dostoevsky - The Brothers KaramazovDocument1,631 pagesFyodor Dostoevsky - The Brothers KaramazovAditi GuptaNo ratings yet

- Clinical PharmacyDocument4 pagesClinical PharmacyLi LizNo ratings yet

- PEEC System Calibrating and AdjustingDocument21 pagesPEEC System Calibrating and AdjustingRichard Chua100% (1)

- Way Compound WayDocument1 pageWay Compound WayreacharunkNo ratings yet

- Ku FR: May MayDocument1 pageKu FR: May MayreacharunkNo ratings yet

- It, ('.Vitl), Ties Tlie F-Li'jhtcitDocument1 pageIt, ('.Vitl), Ties Tlie F-Li'jhtcitreacharunkNo ratings yet

- How They (Should Have) Built The Pyramids Dr. J. West, G. Gallagher, K. WatersDocument11 pagesHow They (Should Have) Built The Pyramids Dr. J. West, G. Gallagher, K. WatersTomasNo ratings yet

- Lecture 2 Gravitation and IsostasyDocument32 pagesLecture 2 Gravitation and IsostasySiyad AbdulrahmanNo ratings yet

- Pressure, Resistance, and Stability of Earth American Society of Civil Engineers: Transactions, Paper No. 1174, Volume LXX, December 1910From EverandPressure, Resistance, and Stability of Earth American Society of Civil Engineers: Transactions, Paper No. 1174, Volume LXX, December 1910No ratings yet

- Theory: ArchitectureDocument1 pageTheory: ArchitecturereacharunkNo ratings yet

- Behavior Etc PDFDocument17 pagesBehavior Etc PDFandra2013No ratings yet

- The Nature of Repose Slopes in Cohesionless Materials: by Brian T. HippleyDocument13 pagesThe Nature of Repose Slopes in Cohesionless Materials: by Brian T. HippleydevitulasiNo ratings yet

- Loadingtests ON by Clay": Theories For Failure Load Under Plates On ClayDocument19 pagesLoadingtests ON by Clay": Theories For Failure Load Under Plates On ClayEMERSON FARLEY DURAN CARRENONo ratings yet

- Phyisics Test by LernomindDocument2 pagesPhyisics Test by LernomindAditya SharmaNo ratings yet

- Greg Egan - Foundations 3 - Black HolesDocument33 pagesGreg Egan - Foundations 3 - Black Holestiwefo7716No ratings yet

- Cosmic 5Document10 pagesCosmic 5Alexander CisnerosNo ratings yet

- Lecture15 Analysis of Single PilesDocument32 pagesLecture15 Analysis of Single PilesJulius Ceasar SanorjoNo ratings yet

- WORK POWER ENERGY-05-Subjective UnSolvedDocument7 pagesWORK POWER ENERGY-05-Subjective UnSolvedRaju SinghNo ratings yet

- A Turbulence-Based Bed-Load Transport Model For Bare and Vegetated ChannelsDocument26 pagesA Turbulence-Based Bed-Load Transport Model For Bare and Vegetated Channelsomed muhammadNo ratings yet

- Materi 4 - Flow of Fluid Through Fluidised BedsDocument27 pagesMateri 4 - Flow of Fluid Through Fluidised BedsAndersen YunanNo ratings yet

- Q Is The Intensity of Total Overburden Pressure Due To The Weight of Both Soil and Water at The Base Level of TheDocument10 pagesQ Is The Intensity of Total Overburden Pressure Due To The Weight of Both Soil and Water at The Base Level of TheCzarinaCanarAguilarNo ratings yet

- SS Question 06 Book Crunch 2020Document88 pagesSS Question 06 Book Crunch 2020Priyansh BNo ratings yet

- Lecture Section 3 Sediment TransportDocument38 pagesLecture Section 3 Sediment TransportAbenezer TsegawNo ratings yet

- Tliesl-In Ttie Is Tlie Tliis IsDocument1 pageTliesl-In Ttie Is Tlie Tliis IsreacharunkNo ratings yet

- Technical Paper-1 (IJSRD)Document4 pagesTechnical Paper-1 (IJSRD)Ram DhankaniNo ratings yet

- Analysis of Pile GroupDocument15 pagesAnalysis of Pile GroupHASSAN SK MDNo ratings yet

- Pge525 3Document42 pagesPge525 3Raed Al-nomanNo ratings yet

- E19 PDFDocument17 pagesE19 PDFDebdutta NandyNo ratings yet

- SS Question 03 Book Crunch 2020Document100 pagesSS Question 03 Book Crunch 2020shashwatNo ratings yet

- Tutorial Ch04Document2 pagesTutorial Ch04khxrsvrgb6No ratings yet

- Light Weight Concrete BoatDocument10 pagesLight Weight Concrete BoatKapil RanaNo ratings yet

- Earthsurface 10Document17 pagesEarthsurface 10tkubvosNo ratings yet

- Schofield A.N. Original Cam-ClayDocument11 pagesSchofield A.N. Original Cam-ClaymiraszaNo ratings yet

- 9 Gravitaion Notes Sa2 QCSSGDocument2 pages9 Gravitaion Notes Sa2 QCSSGDrash GoswamiNo ratings yet

- Bearing-Capacity of Eccentrically Loaded Foundations On Sandy SoilsDocument7 pagesBearing-Capacity of Eccentrically Loaded Foundations On Sandy SoilsHelena LeonNo ratings yet

- May X One The Web MadeDocument1 pageMay X One The Web MadereacharunkNo ratings yet

- Senior Six Mechanics 2022 End of Term 1Document3 pagesSenior Six Mechanics 2022 End of Term 1Becham44No ratings yet

- A Study O F T H E Trap-Door Problem I N A Granular Mass1Document14 pagesA Study O F T H E Trap-Door Problem I N A Granular Mass1Felipe PereiraNo ratings yet

- Dynamic Bearing CapacityDocument22 pagesDynamic Bearing CapacityPeter MattewsNo ratings yet

- friction-1 (3)Document4 pagesfriction-1 (3)Yashh GuptaNo ratings yet

- Dynamics & Statics: Previous Year Questions From 2020 To 1992Document17 pagesDynamics & Statics: Previous Year Questions From 2020 To 1992Subhay kumarNo ratings yet

- Spe 89 Pa PDFDocument13 pagesSpe 89 Pa PDFSteeven RezabalaNo ratings yet

- IsostasyDocument34 pagesIsostasyruchisonuNo ratings yet

- 1824 - Young - Bridge PDFDocument28 pages1824 - Young - Bridge PDFemmanuel nuñez ruizNo ratings yet

- Combined Footing DesignDocument29 pagesCombined Footing DesignIddrisu NajeedNo ratings yet

- Tlie Inc! Liie It Is Is Its Its L) e Tlie IsDocument1 pageTlie Inc! Liie It Is Is Its Its L) e Tlie IsreacharunkNo ratings yet

- A Method to Compute the Non Linear Behaviour of Piles Un 2016 Soils and FounDocument11 pagesA Method to Compute the Non Linear Behaviour of Piles Un 2016 Soils and FounthalesgmaiaNo ratings yet

- Oblique Loading Resulting From Interference Between Surface Footings On SandDocument4 pagesOblique Loading Resulting From Interference Between Surface Footings On SandmahdNo ratings yet

- Behaviour of Laterally Loaded Rigid Piles in Cohesive Soils BasedDocument15 pagesBehaviour of Laterally Loaded Rigid Piles in Cohesive Soils BasedLeo XuNo ratings yet

- Geophysics GravityDocument36 pagesGeophysics Gravityazfarazwanis100% (1)

- Chap 8 FrictionDocument32 pagesChap 8 FrictionAyan Kabir ChowdhuryNo ratings yet

- Science & Tech GKDocument69 pagesScience & Tech GKankurlalaNo ratings yet

- Meseleler Menseyski (Dinamika)Document25 pagesMeseleler Menseyski (Dinamika)aidaNo ratings yet

- Physics 1 - LESSON 5 (Mid - Summer 24)Document12 pagesPhysics 1 - LESSON 5 (Mid - Summer 24)rabbydm809No ratings yet

- Response Spectra For Differential Motion of Columns: Mihailo D. Trifunac and Maria I. TodorovskaDocument18 pagesResponse Spectra For Differential Motion of Columns: Mihailo D. Trifunac and Maria I. TodorovskaMarko AdamovićNo ratings yet

- Elementsofstatic00loneuoft 2Document326 pagesElementsofstatic00loneuoft 2AakashParanNo ratings yet

- Un KLDocument1 pageUn KLreacharunkNo ratings yet

- The Study of T-Z and Q-Z Curves On Bored Pile Based On The Results of Instrumented Pile Load Test in Medium and Stiff ClaysDocument6 pagesThe Study of T-Z and Q-Z Curves On Bored Pile Based On The Results of Instrumented Pile Load Test in Medium and Stiff ClaysHong Viet NguyenNo ratings yet

- Conservation of Linear MomentumDocument15 pagesConservation of Linear MomentumSiddharth Acharya100% (1)

- Granular Convection and Transport Due To Horizontal ShakingDocument3 pagesGranular Convection and Transport Due To Horizontal Shaking池定憲No ratings yet

- Dynamics and Statics PDFDocument16 pagesDynamics and Statics PDFaishwarya maheshwariNo ratings yet

- On an Inversion of Ideas as to the Structure of the UniverseFrom EverandOn an Inversion of Ideas as to the Structure of the UniverseRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Experiments on the Absence of Mechanical Connexion between Ether and MatterFrom EverandExperiments on the Absence of Mechanical Connexion between Ether and MatterNo ratings yet

- Prospekt BGF PDFDocument150 pagesProspekt BGF PDFreacharunkNo ratings yet

- General Terms and Conditions of The Pzu NNW (Personal Accident Insurance Pzu Edukacja InsuranceDocument19 pagesGeneral Terms and Conditions of The Pzu NNW (Personal Accident Insurance Pzu Edukacja InsurancereacharunkNo ratings yet

- En (1459)Document1 pageEn (1459)reacharunkNo ratings yet

- En (1386)Document1 pageEn (1386)reacharunkNo ratings yet

- En (1451)Document1 pageEn (1451)reacharunkNo ratings yet

- En (1464)Document1 pageEn (1464)reacharunkNo ratings yet

- En (1458)Document1 pageEn (1458)reacharunkNo ratings yet

- Mate The: (Fig. - VrouldDocument1 pageMate The: (Fig. - VrouldreacharunkNo ratings yet

- And Rome.: in Front of The Prostyle Existed atDocument1 pageAnd Rome.: in Front of The Prostyle Existed atreacharunkNo ratings yet

- The The Jamb The Name Much The: Tlio CL - AssesDocument1 pageThe The Jamb The Name Much The: Tlio CL - AssesreacharunkNo ratings yet

- En (1383)Document1 pageEn (1383)reacharunkNo ratings yet

- En (1374)Document1 pageEn (1374)reacharunkNo ratings yet

- En (1382)Document1 pageEn (1382)reacharunkNo ratings yet

- En (1376)Document1 pageEn (1376)reacharunkNo ratings yet

- TFP321 03 2021Document4 pagesTFP321 03 2021Richard TorresNo ratings yet

- GE10 Module 2 AnswerDocument10 pagesGE10 Module 2 AnswerJonnel GadinganNo ratings yet

- Quarter 2 Week 6 Day 1: Analyn Dv. Fababaer Srbsmes Tanay, RizalDocument59 pagesQuarter 2 Week 6 Day 1: Analyn Dv. Fababaer Srbsmes Tanay, RizalDronio Arao L-sa100% (1)

- Deviyoga PDFDocument9 pagesDeviyoga PDFpsush15No ratings yet

- Difference Between Institute and University - Difference Between - Institute Vs UniversityDocument5 pagesDifference Between Institute and University - Difference Between - Institute Vs Universitytapar.dashNo ratings yet

- The Assignment Problem: Examwise Marks Disrtibution-AssignmentDocument59 pagesThe Assignment Problem: Examwise Marks Disrtibution-AssignmentAlvo KamauNo ratings yet

- Set LP - 114719Document9 pagesSet LP - 114719Beverly SombiseNo ratings yet

- CSB 188 ManualDocument18 pagesCSB 188 ManualrpshvjuNo ratings yet

- Gen Physics 2 - Module 7 Electric Circuits - Answer SheetDocument7 pagesGen Physics 2 - Module 7 Electric Circuits - Answer SheetDrei DreiNo ratings yet

- 4.3.2 Design Development Phase: Chapter 4 - Submission Phase GuidelinesDocument5 pages4.3.2 Design Development Phase: Chapter 4 - Submission Phase GuidelinesHamed AziziangilanNo ratings yet

- Michael Porter's 5 Forces Model: Asian PaintsDocument4 pagesMichael Porter's 5 Forces Model: Asian PaintsrakeshNo ratings yet

- Transformer InrushDocument4 pagesTransformer InrushLRHENGNo ratings yet

- Ron Feldman DissertationDocument404 pagesRon Feldman DissertationRichard RadavichNo ratings yet

- Three Stages Sediment Filter and Uv Light Purifier: A Water Treatment SystemDocument36 pagesThree Stages Sediment Filter and Uv Light Purifier: A Water Treatment SystemMark Allen Tupaz MendozaNo ratings yet

- 6 - TestDocument24 pages6 - Testsyrine slitiNo ratings yet

- Passive VoiceDocument19 pagesPassive VoiceKinanti TalitaNo ratings yet

- The Nature of Philosophical AnthropologyDocument8 pagesThe Nature of Philosophical AnthropologyPaul HorriganNo ratings yet

- Error Pdfread 3 On FileDocument2 pagesError Pdfread 3 On FileStephanieNo ratings yet

- Unwto Tourism Highlights: 2011 EditionDocument12 pagesUnwto Tourism Highlights: 2011 EditionTheBlackD StelsNo ratings yet

- AP Calculus CDocument16 pagesAP Calculus CSNNo ratings yet

- Django Tables2 Readthedocs Io en LatestDocument65 pagesDjango Tables2 Readthedocs Io en LatestSwastik MishraNo ratings yet

- Industrial Co-Operative Hard Copy... !!!Document40 pagesIndustrial Co-Operative Hard Copy... !!!vikastaterNo ratings yet

- PTC-40-1991 - Performance Test Codes Flue Gas Desulfurization Units PDFDocument70 pagesPTC-40-1991 - Performance Test Codes Flue Gas Desulfurization Units PDFSunil KumarNo ratings yet

- 4 SOEE5010 QuestionnaireDocument2 pages4 SOEE5010 QuestionnairePrince JuniorNo ratings yet

- Jaimini Chara DashaDocument7 pagesJaimini Chara Dasha老莫(老莫)No ratings yet

- Environmental Hazards Assessment at Pre Saharan Local Scale - Case Study From The Draa Valley MoroccoDocument19 pagesEnvironmental Hazards Assessment at Pre Saharan Local Scale - Case Study From The Draa Valley MoroccoChaymae SahraouiNo ratings yet

- SoapDocument4 pagesSoapSi OneilNo ratings yet