Professional Documents

Culture Documents

The Marcos Era Gfghfgvand Martial Law

The Marcos Era Gfghfgvand Martial Law

Uploaded by

Priela DanielCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- D&D 5e - Tales of The Old MargreveDocument208 pagesD&D 5e - Tales of The Old MargreveLeonardo Sanchez100% (12)

- Game of ThrohsDocument121 pagesGame of ThrohsAustin Suter100% (1)

- CHAPTER 23 - Readings in Philippine History in PDF FormatDocument26 pagesCHAPTER 23 - Readings in Philippine History in PDF FormatDagoy, Meguela Angela B.No ratings yet

- HTTPDocument58 pagesHTTPMar Cay PobleteNo ratings yet

- The Marcos Era and Martial LawDocument12 pagesThe Marcos Era and Martial Lawlt castroNo ratings yet

- MARCOSDocument10 pagesMARCOSAmeenah Eiy CyNo ratings yet

- Martial Law: Ferdinand Marcos, in Full Ferdinand Edralin Marcos, (Born September 11, 1917, Sarrat, Philippines-DiedDocument6 pagesMartial Law: Ferdinand Marcos, in Full Ferdinand Edralin Marcos, (Born September 11, 1917, Sarrat, Philippines-DiedEiron SollestreNo ratings yet

- Concept PaperDocument3 pagesConcept PaperJhanna SaplaNo ratings yet

- EDSA RevolutionDocument14 pagesEDSA RevolutionMaria Fatima BagayNo ratings yet

- Martial LawDocument5 pagesMartial LawD' SibsNo ratings yet

- Martial Law During and PostDocument6 pagesMartial Law During and PostLeoncio BocoNo ratings yet

- TheDocument5 pagesTheHope Rogen TiongcoNo ratings yet

- Second EDSA RevolutionDocument25 pagesSecond EDSA RevolutionEDSEL ALAPAGNo ratings yet

- People Power RevolutionDocument16 pagesPeople Power RevolutionRondave MalpayaNo ratings yet

- Marcos and After - Ferdinand E. Marcos, Who Succeeded To The Presidency After Defeating Macapagal inDocument2 pagesMarcos and After - Ferdinand E. Marcos, Who Succeeded To The Presidency After Defeating Macapagal inYsabelle Joana SingsonNo ratings yet

- THEEEEDocument11 pagesTHEEEEMa Joyce ImperialNo ratings yet

- Martial Law and The New SocietyDocument9 pagesMartial Law and The New SocietyJezz VilladiegoNo ratings yet

- People Power RevolutionDocument21 pagesPeople Power RevolutionJasonElizagaNo ratings yet

- Lesson 7Document10 pagesLesson 7englaterrazoebNo ratings yet

- The Period of The Fourth Republic of The PhilippinesDocument32 pagesThe Period of The Fourth Republic of The PhilippinesTrisha Anne Aranzaso BautistaNo ratings yet

- Martial Law Discussion-1Document33 pagesMartial Law Discussion-1Leilani Ca�aNo ratings yet

- Panel DiscussionDocument5 pagesPanel DiscussionJeremiah SmithNo ratings yet

- MARCOSDocument8 pagesMARCOSSwelyn Angelee Mendoza BalelinNo ratings yet

- The End of Military Rule (Fall of Dictatorship)Document28 pagesThe End of Military Rule (Fall of Dictatorship)Christine Jaraula100% (1)

- MarcosDocument11 pagesMarcosJude A. AbuzoNo ratings yet

- Research Paper Martial LawDocument13 pagesResearch Paper Martial LawanonymosNo ratings yet

- Second TermDocument4 pagesSecond TermAlfrien Ivanovich LarchsonNo ratings yet

- Ferdinand E MDocument6 pagesFerdinand E Mprincess kiraNo ratings yet

- Ferdinand MarcosDocument20 pagesFerdinand MarcosHollan Galicia60% (5)

- THE HOWS AND WHYS OF MARTIAL LAW IN THE PHILIPPINES ExpDocument2 pagesTHE HOWS AND WHYS OF MARTIAL LAW IN THE PHILIPPINES ExpOmalin PrincessNo ratings yet

- Tamura - ReflectionDocument1 pageTamura - ReflectionTamura KoujiNo ratings yet

- Fourth Philippine RepublicDocument7 pagesFourth Philippine Republicrj TurnoNo ratings yet

- The Fall of MarcosDocument7 pagesThe Fall of Marcosprincess kiraNo ratings yet

- Group 7 Declaration of Martial Law by President Ferdinand MarcosDocument27 pagesGroup 7 Declaration of Martial Law by President Ferdinand Marcosjerome.No ratings yet

- CHAPTER 23 - Readings in Philippine History in PPT FormatDocument26 pagesCHAPTER 23 - Readings in Philippine History in PPT FormatDagoy, Meguela Angela B.No ratings yet

- Ferdinand Marcos, His Rise and FallDocument14 pagesFerdinand Marcos, His Rise and Fallirvin2030No ratings yet

- History of People Power RevolutionDocument6 pagesHistory of People Power RevolutionJhia Marie YalungNo ratings yet

- People Power RevolutionDocument25 pagesPeople Power RevolutionClaire CarreonNo ratings yet

- Philippine History: Early LifeDocument7 pagesPhilippine History: Early LifeJuliux Solis GuzmoNo ratings yet

- New Era University: Term Paper in Reading in Philippine HistoryDocument8 pagesNew Era University: Term Paper in Reading in Philippine HistoryJohn Mark DalidaNo ratings yet

- Marcos Regime in The 60'sDocument2 pagesMarcos Regime in The 60'sMax FloresNo ratings yet

- GESocSci 2 - Assignment #4 - SavilloDocument9 pagesGESocSci 2 - Assignment #4 - SavilloJoseph Nico SavilloNo ratings yet

- Sala Jud Tanan Ni Marcos - ReportDocument29 pagesSala Jud Tanan Ni Marcos - ReportMegan BiagNo ratings yet

- Summary of Former PresidentsDocument6 pagesSummary of Former PresidentsRyza AriolaNo ratings yet

- Week 5 - The Historical Background of The Philippine GovernmentDocument13 pagesWeek 5 - The Historical Background of The Philippine GovernmentKRISTINE ANGELI BARALNo ratings yet

- Primary and Secondary SourcesDocument4 pagesPrimary and Secondary SourcesIvy JordanNo ratings yet

- Chap 22Document2 pagesChap 22Rozel Joy LabasanoNo ratings yet

- The Marcos AdministrationDocument7 pagesThe Marcos AdministrationCelina LeeNo ratings yet

- The Fall of The DictatorDocument37 pagesThe Fall of The DictatorEdwin SamisNo ratings yet

- Ferdinand Marcos Sr.Document2 pagesFerdinand Marcos Sr.patriciaanngutierrezNo ratings yet

- The Political Ideologies of Marcos and AquinoDocument3 pagesThe Political Ideologies of Marcos and AquinoMargaretteNo ratings yet

- The End of Military RuleDocument26 pagesThe End of Military RuleKyla LinabanNo ratings yet

- HISTDocument2 pagesHISTCherry AbañoNo ratings yet

- MarcussssDocument3 pagesMarcussssNicole Kate CruzNo ratings yet

- Joan BDocument3 pagesJoan BJoan AbadianoNo ratings yet

- The Declaration of Martial Law: Proclamation No. 1081Document17 pagesThe Declaration of Martial Law: Proclamation No. 1081Cherry Mae Morales BandijaNo ratings yet

- Ferdinand Emmanuel Edralin Marcos: The 10 President of The Republic of The PhilippinesDocument34 pagesFerdinand Emmanuel Edralin Marcos: The 10 President of The Republic of The PhilippinesTimoy CajesNo ratings yet

- Hipolito MartialLawDocument3 pagesHipolito MartialLawMichaella PangilinanNo ratings yet

- Philippines - Martial LawDocument4 pagesPhilippines - Martial LawRQL83appNo ratings yet

- Maria Corazon "Cory" Sumulong Cojuangco Aquino: TagalogDocument1 pageMaria Corazon "Cory" Sumulong Cojuangco Aquino: Tagalogbella xiaoNo ratings yet

- The Marcos Rule: Click To Edit Master Subtitle StyleDocument20 pagesThe Marcos Rule: Click To Edit Master Subtitle StyleJanine PadillaNo ratings yet

- On the Marcos Fascist Dictatorship: Sison Reader Series, #11From EverandOn the Marcos Fascist Dictatorship: Sison Reader Series, #11No ratings yet

- Article Xix: Contract Prices and WarrantiesDocument29 pagesArticle Xix: Contract Prices and WarrantiesPriela DanielNo ratings yet

- How To CrackDocument2 pagesHow To CrackPriela DanielNo ratings yet

- Representing Complex Numbers Graphically (+ and - )Document4 pagesRepresenting Complex Numbers Graphically (+ and - )Priela DanielNo ratings yet

- Comments: GM D7 CM G# D# A# CM G# A# A# CM G# A#Document2 pagesComments: GM D7 CM G# D# A# CM G# A# A# CM G# A#Priela DanielNo ratings yet

- Compilation IN E.S.P Remalyn M. Templo Liah May I. Pinto G-7 Mexico Gng. Kathleen San Juan (Teacher)Document1 pageCompilation IN E.S.P Remalyn M. Templo Liah May I. Pinto G-7 Mexico Gng. Kathleen San Juan (Teacher)Priela DanielNo ratings yet

- SealDocument2 pagesSealPriela DanielNo ratings yet

- Hiding Inside MyselfDocument9 pagesHiding Inside MyselfPriela DanielNo ratings yet

- C#m7 Ebm E6 F# C#m7 Ebm G# C#m7 Ebm G D D Bm7 E/F#Document2 pagesC#m7 Ebm E6 F# C#m7 Ebm G# C#m7 Ebm G D D Bm7 E/F#Priela DanielNo ratings yet

- OJT CertificateDocument11 pagesOJT CertificatePriela DanielNo ratings yet

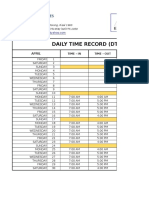

- Daily Time Record (DTR) : AprilDocument10 pagesDaily Time Record (DTR) : AprilPriela DanielNo ratings yet

- Daily Time Record (DTR) : RT Mateo EnterprisesDocument6 pagesDaily Time Record (DTR) : RT Mateo EnterprisesPriela DanielNo ratings yet

- Daily Time Record (DTR) : Date NameDocument2 pagesDaily Time Record (DTR) : Date NamePriela DanielNo ratings yet

- Declamation PieceDocument16 pagesDeclamation PiecePriela Daniel50% (2)

- What Is A Database?Document9 pagesWhat Is A Database?Priela DanielNo ratings yet

- Research Methods - SamplingDocument34 pagesResearch Methods - SamplingMohsin RazaNo ratings yet

- Sirs & ModsDocument26 pagesSirs & Modsnerlyn silao50% (2)

- Installing Birt Viewer On DebianDocument2 pagesInstalling Birt Viewer On DebianxioroneNo ratings yet

- CARLOS A. LORIA, Petitioner, vs. LUDOLFO P. MUÑOZ, JR., RespondentDocument19 pagesCARLOS A. LORIA, Petitioner, vs. LUDOLFO P. MUÑOZ, JR., RespondentNichole John UsonNo ratings yet

- Every Praise: Hezekiah WalkerDocument1 pageEvery Praise: Hezekiah WalkerPamela CabelloNo ratings yet

- Major Assignment Educ2420Document4 pagesMajor Assignment Educ2420api-472363434No ratings yet

- Phrasal Verbs - Mohamed El-SheikhDocument44 pagesPhrasal Verbs - Mohamed El-SheikhMohammed AhmedNo ratings yet

- Revision of An Upper Lip Scar Following - 2022 - Advances in Oral and MaxillofacDocument2 pagesRevision of An Upper Lip Scar Following - 2022 - Advances in Oral and MaxillofacГне ДзжNo ratings yet

- Caste, Identity Politics & Public SphereDocument7 pagesCaste, Identity Politics & Public SpherePremkumar HeigrujamNo ratings yet

- Lebato-Pr2Document6 pagesLebato-Pr2Sir JrNo ratings yet

- Tata Motors WordDocument64 pagesTata Motors WordSayon Das100% (1)

- International Conference Technology and Engineering (MARTECH)Document9 pagesInternational Conference Technology and Engineering (MARTECH)Farah Mehnaz HossainNo ratings yet

- Elemental Energy 101 BrochureDocument2 pagesElemental Energy 101 BrochurebroomclosetsacNo ratings yet

- ESP Cards (Zener Cards)Document13 pagesESP Cards (Zener Cards)wealth07No ratings yet

- TeratomaDocument13 pagesTeratomaGoncang Setyo PambudiNo ratings yet

- Problems of Parenthood + Leadership Functions + Security Tips in The SchoolDocument8 pagesProblems of Parenthood + Leadership Functions + Security Tips in The SchoolAminu SaniNo ratings yet

- Ethical Considerations in ResearchDocument14 pagesEthical Considerations in ResearchJoshua Laygo Sengco0% (1)

- Question of Conservation In: Parity Weak InteractionsDocument5 pagesQuestion of Conservation In: Parity Weak InteractionsAmberNo ratings yet

- Steimour Rate of Sedimentation Suspensions of Uniform-Size Angular Particles PDFDocument8 pagesSteimour Rate of Sedimentation Suspensions of Uniform-Size Angular Particles PDFpixulinoNo ratings yet

- Kibor HistoryDocument3 pagesKibor HistorymaheenwarisNo ratings yet

- MSC CS&is SyllabusDocument42 pagesMSC CS&is SyllabusSamuel Gregory KurianNo ratings yet

- Microsoft Office Specialist: Microsoft Excel Expert (Excel and Excel 2019) - Skills MeasuredDocument3 pagesMicrosoft Office Specialist: Microsoft Excel Expert (Excel and Excel 2019) - Skills MeasuredRishabh Gangwar0% (1)

- From Court of Dar Es at Kisutu in Civil Application No. 107 2022)Document17 pagesFrom Court of Dar Es at Kisutu in Civil Application No. 107 2022)Emmanuel ShekifuNo ratings yet

- The Professional CPA Review SchoolDocument23 pagesThe Professional CPA Review SchoolGray JavierNo ratings yet

- Notes On Courts of HeavenDocument7 pagesNotes On Courts of HeavenAsiko Joseph100% (4)

- TRESPASSDocument46 pagesTRESPASSTilakNo ratings yet

- 4.-Student Dropout Prediction 2020Document12 pages4.-Student Dropout Prediction 2020Cap Scyte Victor MariscalNo ratings yet

- Geotechnical Engineering - Serbulea ManoleDocument229 pagesGeotechnical Engineering - Serbulea ManoleNecula Bogdan MihaiNo ratings yet

The Marcos Era Gfghfgvand Martial Law

The Marcos Era Gfghfgvand Martial Law

Uploaded by

Priela DanielOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

The Marcos Era Gfghfgvand Martial Law

The Marcos Era Gfghfgvand Martial Law

Uploaded by

Priela DanielCopyright:

Available Formats

The Marcos era and Martial Law (1965-1986)

Diosdado Macapagal ran for reelection in 1965, but was defeated by former party-mate, Senate

President Ferdinand E. Marcos, who had switched to the Nacionalista Party.Ferdinand E. Marcos, who

succeeded to the presidency after defeating Macapagal in the 1965 elections, inherited the territorial

dispute over Sabah; in 1968 he approved a congressional bill annexing Sabah to the Philippines.

Malaysia suspended diplomatic relations (Sabah had joined the Federation of Malaysia in 1963), and the

matter was referred to the United Nations. (The Philippines dropped its claim to Sabah in 1978.)

The Philippines became one of the founding countries of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations

(ASEAN) in 1967. The continuing need for land reform promoted a new Huk uprising in central Luzon,

accompanied by mounting assassinations and acts of terror, and in 1969, Marcos began a major military

campaign to control them. Civil war also threatened on Mindanao, where groups of Moros opposed

Christian settlement.

As president, Ferdinand Marcos embarked on a massive spending in infrastructural development, such

as roads, health centers and schools as well as intensifying tax collection which gave the Philippines a

taste of economic prosperity throughout the 1970's. He built more schools than all his predecessors

combined.

In Nov., 1969, Marcos won an unparalleled reelection, easily defeating Sergio Osmea, Jr., but the

election was accompanied by violence and charges of fraud, and Marcoss second term began with

increasing civil disorder. However, he was unable to reduce massive government corruption or to create

economic growth proportional to population growth. The Communist Party of the Philippines formed the

New Peoples Army while the Moro National Liberation Front fought for an independent Mindanao.

In Jan., 1970, some 2,000 demonstrators tried to storm Malacaang Palace, the presidential residence;

rebellions erupted against the U.S. embassy. When Pope Paul VI visited Manila in Nov., 1970, an attempt

was made on his life. In 1971, at a Liberal party rally, hand grenades were thrown at the speakers

platform, and several people were killed. President Marcos declared martial law in Sept., 1972, charging

that a Communist rebellion threatened. The 1935 constitution was replaced (1973) by a new one that

provided the president with direct powers. A plebiscite (July, 1973) gave Marcos the right to remain in

office beyond the expiration (Dec., 1973) of his term. Meanwhile the fighting on Mindanao had spread to

the Sulu Archipelago. By 1973 some 3,000 people had been killed and hundreds of villages burned.

Throughout the 1970s poverty and governmental corruption increased, and Imelda Marcos, Ferdinands

wife, became more influential. Congress called for a Constitutional Convention in 1970 in response to

public cry for a new constitution to replace the colonial 1935 Constitution.

An explosion during the proclamation rally of the senatorial slate of the opposition Liberal Party in Plaza

Miranda in Quiapo, Manila on August 21, 1971, prompted Marcos to suspend the writ of habeas corpus

hours after the blast, which he restored on January 11, 1972 after public protests.

Martial Law (1972-1981)

Using the rising wave of lawlessness and the threat of a

Communist insurgency as justification, Marcos declared

martial law on September 21, 1972 by virtue of Proclamation

No. 1081. Martial Law remained in force until 1981, when

Marcos was reelected, in the midst of accusations of

electoral fraud. Marcos, ruling by decree, curtailed press

freedom and other civil liberties; closed down Congress and

media establishments; and ordered the arrest of opposition

leaders and militant activists, including his staunchest critics

Senator Benigno Aquino, Jr. and Senator Jose Diokno.

Initially, the declaration of martial law was well received,

given the social turmoil the Philippines was experiencing.

Crime rates plunged dramatically after a curfew was

implemented. Political opponents were given the opportunity to go into exile. But, as martial law dragged

on for the next nine years, excesses by the military emerged.

Constitutionally barred from seeking another term beyond 1973 and, with his political enemies in jail,

Marcos reconvenedthe Constitutional Convention and maneuvered its proceedings to adopt a

parliamentary form of government, paving the way for him to stay in power beyond 1973. Sensing that the

constitution would be rejected in a nationwide plebiscite, Marcos decreed the creation of citizens'

assemblies which anomalously ratified the constitution.

Even before the Constitution could be fully implemented, several amendments were introduced to it by

Marcos, including the prolongation of martial law and permitting himself to be President and concurrent

Prime Minister. The economy during the decade was robust, with budgetary and trade surpluses. The

Gross National Product rose from P55 billion in 1972 to P193 billion in 1980. Tourism rose, contributing to

the economy's growth. The number of tourists visiting the Philippines rose to one million by 1980 from

less than 200,000 in previous years. A big portion of the tourist group was composed

of Filipino balikbayans (returnees) under the Ministry of Tourism's Balikbayan Program which was

launched in 1973.

The first formal elections since 1969 for an interim Batasang Pambansa (National Assembly) were held in

1978. In order to settle the Catholic Church before the visit of PopeJohn Paul II, Marcos officially lifted

martial law on January 17, 1981. However, he retained much of the government's power for arrest and

detention. Corruption and nepotism as well as civil unrest contributed to a serious decline in economic

growth and development under Marcos, whose health declined due to lupus.

After the Feb., 1986, presidential election, both Marcos and his opponent, Corazon Aquino (the widow of

Benigno), declared themselves the winner, and charges of massive fraud and violence were leveled

against the Marcos faction. Marcoss domestic and international support battered and he fled the country

on Feb. 25, 1986, finally obtaining refuge in the United States.

The Fourth Republic (1981-1986)

The opposition boycotted presidential elections then developed in June 1981, which pitted Marcos

(Kilusang Bagong Lipunan) against retired Gen. Alejo Santos (Nacionalista Party). Marcos won by a

margin of over 16 million votes, which constitutionally allowed him to have another six-year term. Finance

Minister Cesar Virata was elected as Prime Minister by the Batasang Pambansa.

On Aug. 21, 1983, opposition leader Benigno "Ninoy" Aquino Jr. was assassinated at the Manila

International Airport upon his return to the Philippines after a long period of exile which encouraged a

new, more powerful wave of anti-Marcos dissent. This coalesced popular dissatisfaction with Marcos and

began a succession of events, including pressure from the United States that ended in a snap

presidential election in February 1986. The opposition united under Aquino's widow, Corazon Aquino,

and SalvadorLaurel, head of the United Nationalists Democratic Organizations (UNIDO). The elections

were held on February 7, 1986. The election was blemished by widespread reports of violence and

tampering with results by both sides of the political fence.

The official election canvasser, the Commission on Elections (COMELEC), declared Marcos the winner.

According to COMELEC's final tally, Marcos won with 10,807,197 votes to Aquino's 9,291,761 votes. By

contrast, the final tally of NAMFREL, an accredited poll watcher, said Marcos won with 7,835,070 votes to

Aquino's 7,053,068. The allegedly fraudulent result was not accepted by Corazon Aquino and her

supporters. International observers, including a U.S. delegation led by Sen. Richard G. Lugar (R-Ind.),

denounced the official results. Gen. Fidel Ramos and Defense Minister Juan Ponce Enrile declared that

they no longer supported Marcos.

A peaceful civilian-military uprising forced Marcos into exile and installed Corazon Aquino as president on

25 February 1986.

You might also like

- D&D 5e - Tales of The Old MargreveDocument208 pagesD&D 5e - Tales of The Old MargreveLeonardo Sanchez100% (12)

- Game of ThrohsDocument121 pagesGame of ThrohsAustin Suter100% (1)

- CHAPTER 23 - Readings in Philippine History in PDF FormatDocument26 pagesCHAPTER 23 - Readings in Philippine History in PDF FormatDagoy, Meguela Angela B.No ratings yet

- HTTPDocument58 pagesHTTPMar Cay PobleteNo ratings yet

- The Marcos Era and Martial LawDocument12 pagesThe Marcos Era and Martial Lawlt castroNo ratings yet

- MARCOSDocument10 pagesMARCOSAmeenah Eiy CyNo ratings yet

- Martial Law: Ferdinand Marcos, in Full Ferdinand Edralin Marcos, (Born September 11, 1917, Sarrat, Philippines-DiedDocument6 pagesMartial Law: Ferdinand Marcos, in Full Ferdinand Edralin Marcos, (Born September 11, 1917, Sarrat, Philippines-DiedEiron SollestreNo ratings yet

- Concept PaperDocument3 pagesConcept PaperJhanna SaplaNo ratings yet

- EDSA RevolutionDocument14 pagesEDSA RevolutionMaria Fatima BagayNo ratings yet

- Martial LawDocument5 pagesMartial LawD' SibsNo ratings yet

- Martial Law During and PostDocument6 pagesMartial Law During and PostLeoncio BocoNo ratings yet

- TheDocument5 pagesTheHope Rogen TiongcoNo ratings yet

- Second EDSA RevolutionDocument25 pagesSecond EDSA RevolutionEDSEL ALAPAGNo ratings yet

- People Power RevolutionDocument16 pagesPeople Power RevolutionRondave MalpayaNo ratings yet

- Marcos and After - Ferdinand E. Marcos, Who Succeeded To The Presidency After Defeating Macapagal inDocument2 pagesMarcos and After - Ferdinand E. Marcos, Who Succeeded To The Presidency After Defeating Macapagal inYsabelle Joana SingsonNo ratings yet

- THEEEEDocument11 pagesTHEEEEMa Joyce ImperialNo ratings yet

- Martial Law and The New SocietyDocument9 pagesMartial Law and The New SocietyJezz VilladiegoNo ratings yet

- People Power RevolutionDocument21 pagesPeople Power RevolutionJasonElizagaNo ratings yet

- Lesson 7Document10 pagesLesson 7englaterrazoebNo ratings yet

- The Period of The Fourth Republic of The PhilippinesDocument32 pagesThe Period of The Fourth Republic of The PhilippinesTrisha Anne Aranzaso BautistaNo ratings yet

- Martial Law Discussion-1Document33 pagesMartial Law Discussion-1Leilani Ca�aNo ratings yet

- Panel DiscussionDocument5 pagesPanel DiscussionJeremiah SmithNo ratings yet

- MARCOSDocument8 pagesMARCOSSwelyn Angelee Mendoza BalelinNo ratings yet

- The End of Military Rule (Fall of Dictatorship)Document28 pagesThe End of Military Rule (Fall of Dictatorship)Christine Jaraula100% (1)

- MarcosDocument11 pagesMarcosJude A. AbuzoNo ratings yet

- Research Paper Martial LawDocument13 pagesResearch Paper Martial LawanonymosNo ratings yet

- Second TermDocument4 pagesSecond TermAlfrien Ivanovich LarchsonNo ratings yet

- Ferdinand E MDocument6 pagesFerdinand E Mprincess kiraNo ratings yet

- Ferdinand MarcosDocument20 pagesFerdinand MarcosHollan Galicia60% (5)

- THE HOWS AND WHYS OF MARTIAL LAW IN THE PHILIPPINES ExpDocument2 pagesTHE HOWS AND WHYS OF MARTIAL LAW IN THE PHILIPPINES ExpOmalin PrincessNo ratings yet

- Tamura - ReflectionDocument1 pageTamura - ReflectionTamura KoujiNo ratings yet

- Fourth Philippine RepublicDocument7 pagesFourth Philippine Republicrj TurnoNo ratings yet

- The Fall of MarcosDocument7 pagesThe Fall of Marcosprincess kiraNo ratings yet

- Group 7 Declaration of Martial Law by President Ferdinand MarcosDocument27 pagesGroup 7 Declaration of Martial Law by President Ferdinand Marcosjerome.No ratings yet

- CHAPTER 23 - Readings in Philippine History in PPT FormatDocument26 pagesCHAPTER 23 - Readings in Philippine History in PPT FormatDagoy, Meguela Angela B.No ratings yet

- Ferdinand Marcos, His Rise and FallDocument14 pagesFerdinand Marcos, His Rise and Fallirvin2030No ratings yet

- History of People Power RevolutionDocument6 pagesHistory of People Power RevolutionJhia Marie YalungNo ratings yet

- People Power RevolutionDocument25 pagesPeople Power RevolutionClaire CarreonNo ratings yet

- Philippine History: Early LifeDocument7 pagesPhilippine History: Early LifeJuliux Solis GuzmoNo ratings yet

- New Era University: Term Paper in Reading in Philippine HistoryDocument8 pagesNew Era University: Term Paper in Reading in Philippine HistoryJohn Mark DalidaNo ratings yet

- Marcos Regime in The 60'sDocument2 pagesMarcos Regime in The 60'sMax FloresNo ratings yet

- GESocSci 2 - Assignment #4 - SavilloDocument9 pagesGESocSci 2 - Assignment #4 - SavilloJoseph Nico SavilloNo ratings yet

- Sala Jud Tanan Ni Marcos - ReportDocument29 pagesSala Jud Tanan Ni Marcos - ReportMegan BiagNo ratings yet

- Summary of Former PresidentsDocument6 pagesSummary of Former PresidentsRyza AriolaNo ratings yet

- Week 5 - The Historical Background of The Philippine GovernmentDocument13 pagesWeek 5 - The Historical Background of The Philippine GovernmentKRISTINE ANGELI BARALNo ratings yet

- Primary and Secondary SourcesDocument4 pagesPrimary and Secondary SourcesIvy JordanNo ratings yet

- Chap 22Document2 pagesChap 22Rozel Joy LabasanoNo ratings yet

- The Marcos AdministrationDocument7 pagesThe Marcos AdministrationCelina LeeNo ratings yet

- The Fall of The DictatorDocument37 pagesThe Fall of The DictatorEdwin SamisNo ratings yet

- Ferdinand Marcos Sr.Document2 pagesFerdinand Marcos Sr.patriciaanngutierrezNo ratings yet

- The Political Ideologies of Marcos and AquinoDocument3 pagesThe Political Ideologies of Marcos and AquinoMargaretteNo ratings yet

- The End of Military RuleDocument26 pagesThe End of Military RuleKyla LinabanNo ratings yet

- HISTDocument2 pagesHISTCherry AbañoNo ratings yet

- MarcussssDocument3 pagesMarcussssNicole Kate CruzNo ratings yet

- Joan BDocument3 pagesJoan BJoan AbadianoNo ratings yet

- The Declaration of Martial Law: Proclamation No. 1081Document17 pagesThe Declaration of Martial Law: Proclamation No. 1081Cherry Mae Morales BandijaNo ratings yet

- Ferdinand Emmanuel Edralin Marcos: The 10 President of The Republic of The PhilippinesDocument34 pagesFerdinand Emmanuel Edralin Marcos: The 10 President of The Republic of The PhilippinesTimoy CajesNo ratings yet

- Hipolito MartialLawDocument3 pagesHipolito MartialLawMichaella PangilinanNo ratings yet

- Philippines - Martial LawDocument4 pagesPhilippines - Martial LawRQL83appNo ratings yet

- Maria Corazon "Cory" Sumulong Cojuangco Aquino: TagalogDocument1 pageMaria Corazon "Cory" Sumulong Cojuangco Aquino: Tagalogbella xiaoNo ratings yet

- The Marcos Rule: Click To Edit Master Subtitle StyleDocument20 pagesThe Marcos Rule: Click To Edit Master Subtitle StyleJanine PadillaNo ratings yet

- On the Marcos Fascist Dictatorship: Sison Reader Series, #11From EverandOn the Marcos Fascist Dictatorship: Sison Reader Series, #11No ratings yet

- Article Xix: Contract Prices and WarrantiesDocument29 pagesArticle Xix: Contract Prices and WarrantiesPriela DanielNo ratings yet

- How To CrackDocument2 pagesHow To CrackPriela DanielNo ratings yet

- Representing Complex Numbers Graphically (+ and - )Document4 pagesRepresenting Complex Numbers Graphically (+ and - )Priela DanielNo ratings yet

- Comments: GM D7 CM G# D# A# CM G# A# A# CM G# A#Document2 pagesComments: GM D7 CM G# D# A# CM G# A# A# CM G# A#Priela DanielNo ratings yet

- Compilation IN E.S.P Remalyn M. Templo Liah May I. Pinto G-7 Mexico Gng. Kathleen San Juan (Teacher)Document1 pageCompilation IN E.S.P Remalyn M. Templo Liah May I. Pinto G-7 Mexico Gng. Kathleen San Juan (Teacher)Priela DanielNo ratings yet

- SealDocument2 pagesSealPriela DanielNo ratings yet

- Hiding Inside MyselfDocument9 pagesHiding Inside MyselfPriela DanielNo ratings yet

- C#m7 Ebm E6 F# C#m7 Ebm G# C#m7 Ebm G D D Bm7 E/F#Document2 pagesC#m7 Ebm E6 F# C#m7 Ebm G# C#m7 Ebm G D D Bm7 E/F#Priela DanielNo ratings yet

- OJT CertificateDocument11 pagesOJT CertificatePriela DanielNo ratings yet

- Daily Time Record (DTR) : AprilDocument10 pagesDaily Time Record (DTR) : AprilPriela DanielNo ratings yet

- Daily Time Record (DTR) : RT Mateo EnterprisesDocument6 pagesDaily Time Record (DTR) : RT Mateo EnterprisesPriela DanielNo ratings yet

- Daily Time Record (DTR) : Date NameDocument2 pagesDaily Time Record (DTR) : Date NamePriela DanielNo ratings yet

- Declamation PieceDocument16 pagesDeclamation PiecePriela Daniel50% (2)

- What Is A Database?Document9 pagesWhat Is A Database?Priela DanielNo ratings yet

- Research Methods - SamplingDocument34 pagesResearch Methods - SamplingMohsin RazaNo ratings yet

- Sirs & ModsDocument26 pagesSirs & Modsnerlyn silao50% (2)

- Installing Birt Viewer On DebianDocument2 pagesInstalling Birt Viewer On DebianxioroneNo ratings yet

- CARLOS A. LORIA, Petitioner, vs. LUDOLFO P. MUÑOZ, JR., RespondentDocument19 pagesCARLOS A. LORIA, Petitioner, vs. LUDOLFO P. MUÑOZ, JR., RespondentNichole John UsonNo ratings yet

- Every Praise: Hezekiah WalkerDocument1 pageEvery Praise: Hezekiah WalkerPamela CabelloNo ratings yet

- Major Assignment Educ2420Document4 pagesMajor Assignment Educ2420api-472363434No ratings yet

- Phrasal Verbs - Mohamed El-SheikhDocument44 pagesPhrasal Verbs - Mohamed El-SheikhMohammed AhmedNo ratings yet

- Revision of An Upper Lip Scar Following - 2022 - Advances in Oral and MaxillofacDocument2 pagesRevision of An Upper Lip Scar Following - 2022 - Advances in Oral and MaxillofacГне ДзжNo ratings yet

- Caste, Identity Politics & Public SphereDocument7 pagesCaste, Identity Politics & Public SpherePremkumar HeigrujamNo ratings yet

- Lebato-Pr2Document6 pagesLebato-Pr2Sir JrNo ratings yet

- Tata Motors WordDocument64 pagesTata Motors WordSayon Das100% (1)

- International Conference Technology and Engineering (MARTECH)Document9 pagesInternational Conference Technology and Engineering (MARTECH)Farah Mehnaz HossainNo ratings yet

- Elemental Energy 101 BrochureDocument2 pagesElemental Energy 101 BrochurebroomclosetsacNo ratings yet

- ESP Cards (Zener Cards)Document13 pagesESP Cards (Zener Cards)wealth07No ratings yet

- TeratomaDocument13 pagesTeratomaGoncang Setyo PambudiNo ratings yet

- Problems of Parenthood + Leadership Functions + Security Tips in The SchoolDocument8 pagesProblems of Parenthood + Leadership Functions + Security Tips in The SchoolAminu SaniNo ratings yet

- Ethical Considerations in ResearchDocument14 pagesEthical Considerations in ResearchJoshua Laygo Sengco0% (1)

- Question of Conservation In: Parity Weak InteractionsDocument5 pagesQuestion of Conservation In: Parity Weak InteractionsAmberNo ratings yet

- Steimour Rate of Sedimentation Suspensions of Uniform-Size Angular Particles PDFDocument8 pagesSteimour Rate of Sedimentation Suspensions of Uniform-Size Angular Particles PDFpixulinoNo ratings yet

- Kibor HistoryDocument3 pagesKibor HistorymaheenwarisNo ratings yet

- MSC CS&is SyllabusDocument42 pagesMSC CS&is SyllabusSamuel Gregory KurianNo ratings yet

- Microsoft Office Specialist: Microsoft Excel Expert (Excel and Excel 2019) - Skills MeasuredDocument3 pagesMicrosoft Office Specialist: Microsoft Excel Expert (Excel and Excel 2019) - Skills MeasuredRishabh Gangwar0% (1)

- From Court of Dar Es at Kisutu in Civil Application No. 107 2022)Document17 pagesFrom Court of Dar Es at Kisutu in Civil Application No. 107 2022)Emmanuel ShekifuNo ratings yet

- The Professional CPA Review SchoolDocument23 pagesThe Professional CPA Review SchoolGray JavierNo ratings yet

- Notes On Courts of HeavenDocument7 pagesNotes On Courts of HeavenAsiko Joseph100% (4)

- TRESPASSDocument46 pagesTRESPASSTilakNo ratings yet

- 4.-Student Dropout Prediction 2020Document12 pages4.-Student Dropout Prediction 2020Cap Scyte Victor MariscalNo ratings yet

- Geotechnical Engineering - Serbulea ManoleDocument229 pagesGeotechnical Engineering - Serbulea ManoleNecula Bogdan MihaiNo ratings yet