Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Foreign Language Policies, Research, and Educational Possibilities: A Western Perspective

Foreign Language Policies, Research, and Educational Possibilities: A Western Perspective

Uploaded by

frankramirez9663381Copyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- Vernacular Language Varieties in Educational Setting Research and DevelopmentDocument51 pagesVernacular Language Varieties in Educational Setting Research and DevelopmentMary Joy Dizon BatasNo ratings yet

- Greek Theatre Lesson PlanDocument17 pagesGreek Theatre Lesson PlanyaraafslNo ratings yet

- A Global Perspective On Bilingualism and Bilingual EducationDocument2 pagesA Global Perspective On Bilingualism and Bilingual EducationcanesitaNo ratings yet

- Australia National STEM School Education Strategy PDFDocument12 pagesAustralia National STEM School Education Strategy PDFYee Jiea PangNo ratings yet

- Lesson Plan Compare and ContrastDocument4 pagesLesson Plan Compare and Contrastapi-295654134No ratings yet

- What Are The Similarities and Differences Among English Language, Foreign Language, and Heritage Language Education in The United States?Document8 pagesWhat Are The Similarities and Differences Among English Language, Foreign Language, and Heritage Language Education in The United States?Luis Alfredo Acosta QuirozNo ratings yet

- AGlobalPerspectiveonBilingualism PDFDocument5 pagesAGlobalPerspectiveonBilingualism PDFradev m azizNo ratings yet

- A Global Perspective On BilingualismDocument5 pagesA Global Perspective On Bilingualismpaula d´alessandroNo ratings yet

- Bilingual EducationDocument15 pagesBilingual EducationananogueiracavalheiroNo ratings yet

- Learning in Two Languages: Spanish-English Immersion in U.S. Public SchoolsDocument31 pagesLearning in Two Languages: Spanish-English Immersion in U.S. Public Schoolsanon-242852No ratings yet

- Reasons For Multilingual Education and Language Policies of Malaysia and The PhilippinesDocument15 pagesReasons For Multilingual Education and Language Policies of Malaysia and The PhilippinesFarhana Abdul FatahNo ratings yet

- Mgqwashu Academic Literacy in The Mother Tongue: A Pre-Requisite For Epistemological AccessDocument20 pagesMgqwashu Academic Literacy in The Mother Tongue: A Pre-Requisite For Epistemological AccessMihail EryvanNo ratings yet

- Bilingualism, SLA and ESL 6th April 2020Document7 pagesBilingualism, SLA and ESL 6th April 2020Navindra Arul ShanthiranNo ratings yet

- Spanish Language and Culture: Implementation OverviewDocument19 pagesSpanish Language and Culture: Implementation OverviewKhawaja EshaNo ratings yet

- Correlates of Filipino Students Perspect 20b4ab8fDocument22 pagesCorrelates of Filipino Students Perspect 20b4ab8fKayla Patreece NocomNo ratings yet

- Final Na Talaga BesDocument68 pagesFinal Na Talaga BesEMMARIE ROSE SALCEDO (SBE)No ratings yet

- 2583-Article Text-4838-1-10-20210219Document12 pages2583-Article Text-4838-1-10-20210219Mehdid ImeneNo ratings yet

- Language Diversity and LearningDocument4 pagesLanguage Diversity and LearningHemang A.No ratings yet

- JNS - 33 - S1 - 97Document25 pagesJNS - 33 - S1 - 97jctabora0909No ratings yet

- 3.1 The Definition of Bilingualism and Types of BilingualismDocument19 pages3.1 The Definition of Bilingualism and Types of Bilingualismxxx7589No ratings yet

- Wbeal 0780Document9 pagesWbeal 0780gailzanneNo ratings yet

- Politico-Economic Influence and Social Outcome of English Language Among Filipinos: An AutoethnographyDocument11 pagesPolitico-Economic Influence and Social Outcome of English Language Among Filipinos: An AutoethnographyBav VAansoqnuaetzNo ratings yet

- Glocalizing ELT: From Chinglish To China English: Xing FangDocument5 pagesGlocalizing ELT: From Chinglish To China English: Xing FangMayank YuvarajNo ratings yet

- MontalvoJose M4 ANALYSIS FINAL DRAFTDocument10 pagesMontalvoJose M4 ANALYSIS FINAL DRAFTJoe MontalvoNo ratings yet

- Language and Academic Achievement: Perspectives On The Potential Role of Indigenous African Languages As A Lingua AcademicaDocument13 pagesLanguage and Academic Achievement: Perspectives On The Potential Role of Indigenous African Languages As A Lingua AcademicaOliver OwuorNo ratings yet

- Bilingualizing Linguistically Homogeneous Classrooms in Kenya Implications On Policy Second Language Learning and LiteracyDocument15 pagesBilingualizing Linguistically Homogeneous Classrooms in Kenya Implications On Policy Second Language Learning and Literacyadrift visionaryNo ratings yet

- DualLanguages WhyHowWhenShouldMyChildLearnL2brochureDocument2 pagesDualLanguages WhyHowWhenShouldMyChildLearnL2brochureAndreea ZahaNo ratings yet

- Tsui - Tollefson - 2004 - IntroDocument11 pagesTsui - Tollefson - 2004 - IntroHoorNo ratings yet

- Causes and Consequences of The Global Expansion of EnglishDocument9 pagesCauses and Consequences of The Global Expansion of EnglishOliver AloyceNo ratings yet

- English Grammar CompetenceDocument10 pagesEnglish Grammar CompetenceEmerito RamalNo ratings yet

- Book Review-Language Planning & Policy - Latin America, Vol. 1Document4 pagesBook Review-Language Planning & Policy - Latin America, Vol. 1BradNo ratings yet

- Incorporating The Idea of Social Identity Into English Language EducationDocument29 pagesIncorporating The Idea of Social Identity Into English Language EducationAmin MofrehNo ratings yet

- Great FSLDocument5 pagesGreat FSLapi-291316245No ratings yet

- The Effectiveness of Bilingual Program and Policy in The Academic Performance and Engagement of StudentsDocument10 pagesThe Effectiveness of Bilingual Program and Policy in The Academic Performance and Engagement of StudentsJoshua LagonoyNo ratings yet

- How Does Short-Term Foreign Language Immersion Stimulate Language Learning?Document18 pagesHow Does Short-Term Foreign Language Immersion Stimulate Language Learning?Lee YuhshiNo ratings yet

- Concept Paper - Cultural Factors On English LearningDocument27 pagesConcept Paper - Cultural Factors On English LearningMark Dennis AsuncionNo ratings yet

- TranslanguagingDocument14 pagesTranslanguagingCarlos SanzNo ratings yet

- Sonia Nieto 1Document5 pagesSonia Nieto 1Protoss ArchonNo ratings yet

- L201 B Chapter 13 Summary Notes (Short)Document14 pagesL201 B Chapter 13 Summary Notes (Short)ghazidaveNo ratings yet

- Campbell Et Al. (2000)Document14 pagesCampbell Et Al. (2000)Gene JezabelNo ratings yet

- Toward A Definition of Heritage Language - Sociopolitical and Pedagogical ConsiderationsDocument21 pagesToward A Definition of Heritage Language - Sociopolitical and Pedagogical ConsiderationsLara MaiatoNo ratings yet

- Argumentative PaperDocument12 pagesArgumentative Paperapi-353444337No ratings yet

- From Linguistic Landscapes To Teaching Resources: A Case of Some Rural Areas in The Province of QuezonDocument22 pagesFrom Linguistic Landscapes To Teaching Resources: A Case of Some Rural Areas in The Province of QuezonAna Mae LinguajeNo ratings yet

- Lang Policy in SADocument17 pagesLang Policy in SARtoesNo ratings yet

- The New Challenge of The Mother Tongues: The Future of Philippine Post-Colonial Language PoliticsDocument7 pagesThe New Challenge of The Mother Tongues: The Future of Philippine Post-Colonial Language PoliticsChristine AltamarinoNo ratings yet

- Communication LanguageDocument3 pagesCommunication LanguageJef FreyNo ratings yet

- KnowledgeapplicationessayDocument7 pagesKnowledgeapplicationessayapi-290715072No ratings yet

- Towards An Agenda For Developing Multilingual Communication With A Community BaseDocument41 pagesTowards An Agenda For Developing Multilingual Communication With A Community BaseAira Nicole AncogNo ratings yet

- TupasDocument14 pagesTupasSim QuiambaoNo ratings yet

- English Language Medium of Instruction 1-3Document40 pagesEnglish Language Medium of Instruction 1-3Nslaimoa AjhNo ratings yet

- Languages in The Contemporary WorldDocument25 pagesLanguages in The Contemporary WorldAlen Catovic0% (2)

- REVISED Obrar Mary Zey M. Intro BackgroundDocument7 pagesREVISED Obrar Mary Zey M. Intro BackgroundJohn Harold Guk-ongNo ratings yet

- English Language Teaching in Mauritius - A Need For Clarity of Vision Regarding English Language PolicyDocument12 pagesEnglish Language Teaching in Mauritius - A Need For Clarity of Vision Regarding English Language Policynitishdr1231No ratings yet

- Scott TeachingEnglishForeign 1965Document6 pagesScott TeachingEnglishForeign 1965Re;FinsaNo ratings yet

- II. The Scope of English and EL TeachingDocument4 pagesII. The Scope of English and EL TeachingSabri DafaallaNo ratings yet

- ED359 - Assignment 3 Part BDocument16 pagesED359 - Assignment 3 Part BSela FilihiaNo ratings yet

- Translanguaging in Multilingual English Language Teaching in The Philippines: A Systematic Literature ReviewDocument6 pagesTranslanguaging in Multilingual English Language Teaching in The Philippines: A Systematic Literature ReviewTranie GatilNo ratings yet

- Mother Tongue Based Multilingual EducatiDocument15 pagesMother Tongue Based Multilingual EducatiRosemarie SayonNo ratings yet

- Peters & BurridgeDocument9 pagesPeters & BurridgeJemarie Porre AmorteNo ratings yet

- Language Policy in A Multilingual SocietyDocument11 pagesLanguage Policy in A Multilingual SocietyBeny Pramana Putra100% (1)

- Effects of Bilingual and Code-Switching in Filipino LearnsDocument4 pagesEffects of Bilingual and Code-Switching in Filipino LearnsMaria Eloisa BlanzaNo ratings yet

- Module 1Document10 pagesModule 1LARREN JOY CASTILLONo ratings yet

- Manual of American English Pronunciation for Adult Foreign StudentsFrom EverandManual of American English Pronunciation for Adult Foreign StudentsNo ratings yet

- AHW3e - Level 01 - U04 - VWDocument2 pagesAHW3e - Level 01 - U04 - VWfrankramirez9663381No ratings yet

- Glossary of Automotive TermsDocument45 pagesGlossary of Automotive Termsfrankramirez9663381No ratings yet

- Lesson Plan Conversation Club About CocoDocument3 pagesLesson Plan Conversation Club About Cocofrankramirez9663381No ratings yet

- Centro Universitario Juana de Asbaje English Class Summer Course Ba Francisco Ramirez GarciaDocument2 pagesCentro Universitario Juana de Asbaje English Class Summer Course Ba Francisco Ramirez Garciafrankramirez9663381No ratings yet

- Introduction To Corpus LinguisticsDocument26 pagesIntroduction To Corpus Linguisticsfrankramirez9663381No ratings yet

- Second Language Acquisition Swain's Output Vs Krashen's InputDocument6 pagesSecond Language Acquisition Swain's Output Vs Krashen's Inputfrankramirez9663381No ratings yet

- All of Me Song ExerciseDocument3 pagesAll of Me Song Exercisefrankramirez9663381No ratings yet

- Graded Exercises in English 64Document1 pageGraded Exercises in English 64frankramirez9663381No ratings yet

- Defensa Tesi111sDocument22 pagesDefensa Tesi111sfrankramirez9663381No ratings yet

- Vol 26 3Document184 pagesVol 26 3frankramirez9663381No ratings yet

- There's Nothing Holdin' Me Back Shawn MendesDocument2 pagesThere's Nothing Holdin' Me Back Shawn Mendesfrankramirez9663381No ratings yet

- What Adults Can Learn From Kids Adora Stivak - ReadyDocument3 pagesWhat Adults Can Learn From Kids Adora Stivak - Readyfrankramirez96633810% (1)

- Photograph Ed SheeranDocument1 pagePhotograph Ed Sheeranfrankramirez9663381No ratings yet

- However / Nevertheless / Nonetheless ButDocument1 pageHowever / Nevertheless / Nonetheless Butfrankramirez9663381No ratings yet

- Mariana Atencio Act - ReadyDocument2 pagesMariana Atencio Act - Readyfrankramirez9663381No ratings yet

- The Impact of Songs in ESL Students' MotivationDocument43 pagesThe Impact of Songs in ESL Students' Motivationfrankramirez9663381No ratings yet

- Grammar-EXTRA NI 4 Unit 4 Future-Continuous-And-Future-Perfect PDFDocument1 pageGrammar-EXTRA NI 4 Unit 4 Future-Continuous-And-Future-Perfect PDFj.t.LLNo ratings yet

- Carrie Green ActivityDocument4 pagesCarrie Green Activityfrankramirez9663381No ratings yet

- Centro Escolar Juana de Asbaje English Academy. Activity To Develop Different SkillsDocument1 pageCentro Escolar Juana de Asbaje English Academy. Activity To Develop Different Skillsfrankramirez9663381No ratings yet

- Academic 2 - Unit 6 - Reduction of Adverb Clauses To Modifying Adverbial Phrases - Charts With E PDFDocument4 pagesAcademic 2 - Unit 6 - Reduction of Adverb Clauses To Modifying Adverbial Phrases - Charts With E PDFfrankramirez9663381No ratings yet

- Turn The Verbs in The Following Sentences Into The PassiveDocument2 pagesTurn The Verbs in The Following Sentences Into The Passivefrankramirez9663381No ratings yet

- Learning Platform Overview - UWCSEADocument12 pagesLearning Platform Overview - UWCSEAajmccarthynzNo ratings yet

- 2005 Steer Report Learning BehaviourDocument100 pages2005 Steer Report Learning BehaviourRonan SharkeyNo ratings yet

- Hpe - Forward Planning Document Lesson 3Document3 pagesHpe - Forward Planning Document Lesson 3api-307709076No ratings yet

- MINUTES OF LAC SESSION Sept.24 MODULE 4Document7 pagesMINUTES OF LAC SESSION Sept.24 MODULE 4Allyn Marie RojeroNo ratings yet

- Lesson Plan Photosynthesis LabDocument4 pagesLesson Plan Photosynthesis Labapi-251950318100% (1)

- Reflection On Coaching ExperienceDocument5 pagesReflection On Coaching Experienceapi-357042891No ratings yet

- Month of MARCH 2024Document23 pagesMonth of MARCH 2024roger cabarles iiiNo ratings yet

- CSTP 5 Reed 4 28 2022Document14 pagesCSTP 5 Reed 4 28 2022api-557161783No ratings yet

- Communication Self AssessmentDocument5 pagesCommunication Self AssessmentAamir SonuNo ratings yet

- Language Learning Enhanced by Music and SongDocument7 pagesLanguage Learning Enhanced by Music and SongNina Hudson100% (2)

- Development of Financial Accounting Achievement Test For Assessment of Senior Secondary School Students in Imo StateDocument13 pagesDevelopment of Financial Accounting Achievement Test For Assessment of Senior Secondary School Students in Imo StateSoulla Gabrielle GordonNo ratings yet

- DLHM & DCCM Re-Orientation: Division Local Heritage Matrix & Division Contextualized Curriculum MatrixDocument39 pagesDLHM & DCCM Re-Orientation: Division Local Heritage Matrix & Division Contextualized Curriculum MatrixRed AytonaNo ratings yet

- The Hunger Games:: Unit Plan ScheduleDocument3 pagesThe Hunger Games:: Unit Plan Scheduleapi-335826189No ratings yet

- Graduate Studies and Applied Research: College of Teacher EducationDocument31 pagesGraduate Studies and Applied Research: College of Teacher EducationClarise Dayo100% (2)

- DLL-English 8Document7 pagesDLL-English 8Zenmar Luminarias GendiveNo ratings yet

- Engineering Design Thinking TeachingandlearningDocument18 pagesEngineering Design Thinking TeachingandlearningBruno Botelho0% (1)

- Objects That Emit Light Vs Those That Need A SourceDocument3 pagesObjects That Emit Light Vs Those That Need A Sourceapi-296427690No ratings yet

- Topic: Foundation For Assessment: What To AssessDocument22 pagesTopic: Foundation For Assessment: What To AssessNUR FAIZAHNo ratings yet

- Worksheet FS1Document29 pagesWorksheet FS1Lors ArcaNo ratings yet

- Blueprinting in Assessment: How Much Is Imprinted in Our Practice?Document3 pagesBlueprinting in Assessment: How Much Is Imprinted in Our Practice?Priya100% (1)

- Universal Design For Learning Lesson Plan TemplateDocument3 pagesUniversal Design For Learning Lesson Plan TemplateJerson Aguilar(SME)No ratings yet

- How Can We Make Assessments MeaningfulDocument5 pagesHow Can We Make Assessments MeaningfulChona Valles ObnascaNo ratings yet

- MB0043 - Human Resorce ManagementDocument26 pagesMB0043 - Human Resorce ManagementNeelam AswalNo ratings yet

- Quality Assurance of Multiple-Choice Tests: London South Bank University, London, UKDocument7 pagesQuality Assurance of Multiple-Choice Tests: London South Bank University, London, UKSaddaqatNo ratings yet

- CSTP 1 Mitchell 7Document6 pagesCSTP 1 Mitchell 7api-203432401No ratings yet

- PbesDocument18 pagesPbesMike TrackNo ratings yet

- PARCCcompetenciesDocument9 pagesPARCCcompetenciesClancy RatliffNo ratings yet

Foreign Language Policies, Research, and Educational Possibilities: A Western Perspective

Foreign Language Policies, Research, and Educational Possibilities: A Western Perspective

Uploaded by

frankramirez9663381Original Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Foreign Language Policies, Research, and Educational Possibilities: A Western Perspective

Foreign Language Policies, Research, and Educational Possibilities: A Western Perspective

Uploaded by

frankramirez9663381Copyright:

Available Formats

Duff, p.

1

APEC Educational Summit

Beijing

January 12-14, 2004

Foreign Language Policies, Research, and Educational Possibilities:

A Western Perspective

Patricia A. Duff

University of British Columbia

With the intense globalization and human migration taking place within the Asia-Pacific region as well as

beyond it, an appreciation of multiple languages and cultures and an ability to communicate effectively

with people across languages, cultures, and communities is crucial. Many APEC member countries

understand this principle much better than we do in North America, where it is often assumed

that knowledge of one language, English, the dominant language of international business,

higher education, information and communication technologies, popular culture, diplomacy, and

so on, is sufficient. Many educational organizations and individuals in Canada and the United

States are nonetheless committed to fostering high levels of foreign language proficiency among

our citizens by invoking its personal, professional, and societal benefits and by developing

exemplary instructional methods and curriculum suitable for a variety of language learning

purposes.

A Brief History of FL Teaching Methods

As in many parts of the world, FL teaching in the West went first through a long period of instruction

emphasizing grammar, reading and translation skills, and appreciation of classicaland then modern--

literary texts. This was followed by a shift in emphasis from written texts to oral skills after the Second

World War during a period of teaching characterized by grammatical pattern drills and rote memorization

and repetition (Brown, 2000; Hadley, 2001). Even now, particularly at the high school and postsecondary

levels, the grammar-translation method is still evident in many classrooms and on many national paper-

and-pencil FL tests. This reflects a view that knowledge about language (and especially about grammar

and vocabulary) equals proficiency in language. Yet there is widespread recognition that the global

citizens of today and tomorrow require oral (i.e. listening, speaking) as well as literate/written proficiency

in FLs and must be able to use language for intercultural communication both locally and globally in

various kinds of contexts, whether business or other professional or community settings. Understanding

canonical literary texts or reproducing memorized dialogs, while one aspect of many students FL

learning experience, is in and of itself simply inadequate in todays multilingual world (Byrnes, 1998). As

is commonly the case, the pendulum had swung in the opposite direction in the late 20

th

century, with

oral communication stressed to the exclusion of literacy, or any substantive content discussion,

intercultural sensitivity, or even grammar correction. These extreme pendulum swings are common in

educational reform but are often counter-productive.

Despite the slow pace at which sound educational change often takes place in FL curriculum, as

well as in teaching methods and materials development, there have been some promising

innovations in FL instruction in the latter part of the 20

th

century and early 21

st

century in North

America and elsewhere. These innovations involve content-based and immersion language

teaching, proficiency-oriented communicative FL teaching, task-based language teaching, project-

based learning, the use of technology to enhance language learning and to build virtual, multilingual

learning communities, and the increased validation of students home or heritage languages and

multiliteracies through the development of heritage-language and two-way bilingual programs, to

name a few options (Hadley, 2001; Pufahl, Rhodes, & Christian, 2000; Doughty & Long, 2003b).

Duff, p. 2

Priorities, Practices, and Contexts for FL Education: International and Heritage Languages

Over the past fifteen years, some significant changes have taken place in foreign language (FL)

education policies and practices in North America and Europe, as well as on other continents around the

world. These changes are associated with large-scale political and economic reforms, shifting

immigration patterns, perceived national security issues and priorities, especially since September, 2001,

and the establishment of new regional alliances, with countries in Central and Eastern Europe joining the

European Union in 2004, for example. Canada, as an officially bilingual country, has championed the

instrumental as well as integrative benefits of FL knowledge (English or French) more vigorously than the

United States, an officially monolingual country, has. Nevertheless, except for the success of French-

immersion schooling, FL outcomes in Canada have not been as impressive as one would hope, as the

majority of the Canadian-born population is still only functionally monolingual or has limited FL

proficiency, at least with respect to these official languages. The Canadian Federal Government has

recently promised considerably more money to educational institutions to promote French-English

bilingualism and the national solidarity that is associated with knowledge of both official languages. With

recent waves of immigration from the Asia-Pacific region though, Chinese has now become the most

common home language in Canada after English and French (followed by Italian and German; Statistics

Canada, 2001) and is much more widely spoken in British Columbia, my home province, than is French.

At the University of British Columbia, some 3000 students a year are enrolled in Mandarin language

courses; there is now an elementary school Mandarin-immersion program at a public school in

Vancouver; and Mandarin, Japanese, and Spanish have supplanted German in secondary schools.

The Korean-Canadian community, in conjunction with a team at the University of British Columbia,

is preparing a new curriculum for Ministry approval for Korean as a FL in schools in and around

Vancouver (Duff, in press). As is the case in Australia, societal multilingualism in a variety of

European, Asian, and other international or community languages is therefore being encouraged.

(The use of foreign in FL is something of a misnomer nowadays, since the languages learned are

often those of our own families and neighborhoods). The importance of numerous

community/international/aboriginal languages and not just Canadas official languages is reflected in

current FL education policies and options in many Canadian provinces (e.g., Reeder et al., 1997).

However, there are implications for the changing profiles of language learners in our FL classes as

well; using materials developed for monolingual English speakers with heritage-language learners

who already have certain levels of oral skills, cultural knowledge, and/or literacy, or mixing students

with significant prior FL learning histories with those who are true beginners is highly problematic as

many schools and universities are finding (e.g., Spanish in the United States, Korean and Mandarin

in Canada) . Where numbers of students and educational budgets warrant it, careful placement

testing and tracking of students according to their linguistic needs and backgrounds is essential.

Given the size of the Spanish-speaking population within the U.S., and the countrys proximity to

Spanish-speaking countries in Mexico, Central, and South America, proficiency in Spanish as a FL and

other immigrant, indigenous, or international languages has become vital to its national interests, whether

to build a stronger workforce, a more secure nation, or to effect improvements in other educational

domains (Pufahl et al., 2000). Tolerance for cultural difference, multiculturalism and anti-racist initiatives

seem to be less common reasons given by politicians for FL education in the United States than they are

in Europe, Australia, and Canada, although intercultural understanding is found in several components in

Standards for Foreign Language Learning (1996) embraced by the American FL teaching community.

Currently, a big push for FL study in the U.S. is linked to Americas national security concerns, under the

auspices of Homeland Security (see e.g., Brecht & Rivers, 2001). After Sept. 11, 2001, when security

agencies found highly proficient speakers of Middle Eastern and Southwest Asian languages to be in

short supply, the FBI and other agencies conducted a campaign to recruit students and highly proficient

Duff, p. 3

speakers of non-European languages to professions requiring knowledge of those languages.

Indeed, the rhetoric supporting FL learning and research in the U.S. currently implies that foreign

languages constitute a potential threat to the nations well-being rather than a cultural and cognitive

resource worthy of study for their own sake, and that for reasons of self-protection the country must

have expertise in certain targeted FLs (e.g., Pushtu, Farsi, Arabic, Korean). This stance is evident,

for example, in the U.S. National Flagship Language Initiative Pilot Program, to develop high level

proficiency in what have previously been less commonly taught languages: Arabic, Chinese, and

Korean. Like other national foreign language research and resource initiatives, the Flagships

programs are receiving substantial funding from either the defense establishment or from federal

security agencies. At the same time as FLs are being linked with security issues, there has been

renewed interest in tapping into the existing linguistic resources in the country, namely immigrants

who have some degree of proficiency in a wide range of languages rather than trying to build up new

FL resources from beginning levels (Brecht & Ingold, 2002). Research is now also beginning to

study heritage-language learners in comparison with non-heritage students, especially in terms of

their ultimate levels of FL attainment, identity issues, and so on (Brinton & Kagan, in press).

Finally, the unique status of heritage-language education requires much more careful attention as

larger numbers of Mandarin, Korean, and Spanish students in both school and university courses in

Canada and the US come from those same linguistic and cultural backgrounds. Importantly, nearly

all existing FL curriculum and teacher education assumes that the FL learners will be more or less

monolingual English speakers who have little knowledge of the languages, literacies, and cultures

they are studying. This assumption is no longer valid though. That is not to say that heritage

language education is not worthwhile; rather, it is commendable and has many advantages for

learners, their families, and for society. But new research shows that the research and instructional

methods, materials, and priorities for heritage language learners may need to be very different from

those of non -heritage learners and that programs are most effective when students are placed in

appropriate tracks (heritage or non-heritage) (Duff, in press). Also, just because teachers happen to

be native speakers of the FL to be taught does not mean that they will be effective teachers, which

is commonly assumed in English as a FL settings as well. All FL teachers (native and non-native

speakers alike) require training in applied linguistics and appropriate FL pedagogy.

In many countries (e.g., Germany, Finland, Morocco), the preparation of FL teachers is much

more rigorous, lengthy, and prestigious than it is in Canada or the United States (Pufahl et al.,

2000). Also, study-abroad, work-abroad, and other forms of internships in Great Britain and

continental Europe increase students FL proficiency and confidence using the FL for general

communicative and pedagogical purposes. In-service and continuing professional development

programs for teachers to further develop their skills are considered important and are more

available in Europe than in North America (Tucker, 2001; Pufahl et al., 2000). These are areas

in which improvements are therefore warranted.

Age-related Language Learning Issues

While some recent reforms in FL education internationally have been very positive, fostering

functional trilingualism in European Union member countries, for example, research suggests

that other reforms have been implemented with insufficient attention paid to the implications

for teacher education, for selecting teaching methodologies suitable for learners at different

ages and with learning objectives that are markedly different from those of past generations.

A major change internationally has been the trend, often in response to intense parental, societal, and

economic pressures, to lower the age at which students first begin to learn a FL at school. Indeed, the age

issue is of such great importance currently that it was selected in 2002-03 to be the inaugural research

Duff, p. 4

priority for the newly established TESOL International Research Foundation (see Duff &

Bailey, 2001, especially Tucker, 2001; Snow, 2001; Lightbown, 2001).

Whereas in many countries, including my province in Canada (British Columbia), the study of FLs in the

past was mandatory from secondary or junior high school (e.g., age 14), increasingly students from as

early as the first, third or fourth grade must begin their FL study. Similar trends exist in Costa Rica, Korea,

Japan, and Thailand (Tucker, 2001). This downward push can be justified for affective and cognitive

reasons. That is, it is generally believed that there is a critical period for optimal language learning, and

particularly for FL pronunciation, ending around the age of puberty, and it is also thought that students are

more open to other languages and cultures and are less self-conscious about their own FL production

before they become adolescents (Lightbown & Spada, 1999; Ellis, 1994). Also, in countries where at least

two FLs must be studied, earlier exposure to one language allows room in the curriculum for exposure to

the second FL later. For example, in Luxembourg, where the study of two FLs is mandatory, students

start learning German or French from age 6 (Pufahl, et al., 2000). In Morocco, compulsory French

instruction now begins in Grade 2 and English instruction in Grade 5. Some countries that have changed

the age of first FL learning to Grade 3 are now lowering it to kindergarten or Grade 1. In countries where

English is normally the first FL to be studied (e.g., Austria, Spain, Thailand, Italy), it is often introduced

from as early as Grade 1 (age 6) (Pufahl et al., 2000). In many cases, this early FL teaching amounts to

one hour per week or less.

However, the age at which FL learning commences and the intensity, duration, and quality of FL

instruction, the status of the FL course itself within the school curriculum, and students metalinguistic

efficiency are all variables that must be taken into account when changing policies of this nature and

evaluating the effectiveness of earlier FL instruction (Lightbown, 2001; Tucker, 2001). Indeed, several

scholars (e.g., Lightbown & Spada, 1999) have written about the myth of the earlier the better principle

in FL learning, noting that a shorter but more intensive FL learning experience in the later elementary

years may be just as effective if not more so than a so-called drip-feed method of instruction over many

years when children are younger, less cognitively developed, receive too little instruction to make much of

a difference, and may have teachers who themselves are not highly proficient (Lightbown & Spada, 1999)

. Although Pufahl et al. (2000) reported that the advice of 22 educators from 19 countries (e.g., Australia,

Brazil, Canada, Thailand) to U.S. FL policy-makers was that FL education should be started earlierin

elementary school not middle school or high schoolthey also noted that if that is the case, FLs must be

designated as core subjects with a similar status to mathematics and reading and that teachers must be

well trained, programs well funded with small enough class sizes, and the curriculum well articulated with

clear descriptions of threshold levels or learning benchmarks for language use in daily life (as in the case

of the Common European Framework of Reference; Council of Europe, 2001). Reducing the age of

English FL learning, as has been witnessed recently in South Korea, often has as a consequence

tremendous competition among students wishing to excel in the language from even earlier levels

(especially when their own teachers English and training in FL teaching methods may be less than

optimal), resulting in expensive extracurricular private-sector tutoring that many parents feel obliged to

send their children to. In other countries, students may avail themselves of extensive tutoring if there is a

perceived mismatch between the school FL curriculum and high-stakes school-leaving or university-

entrance examinations.

Policies such as the earlier introduction of FL instruction are often conceived without

consideration for how university faculties of education will manage to prepare sufficient

numbers of well-qualified, highly proficient teachers at the targeted age/grade levels to

implement such policies effectively (Phillips, 2003). Using materials and methods designed for

older students with much younger ones is ill-advised. Furthermore, expecting students to read

in a language they do not yet speak often sets them up for failure (Snow, 2001).

Duff, p. 5

Rosenbusch (1995) reports that the minimum amount of time recommended for an elementary school foreign

language class is 75 minutes per week, with classes meeting at least every other day. Others have

recommended at least 30 minutes a day, everyday, long enough for students to engage in meaningful activities

(see also the ACTFL Performance Guidelines for K-12 Learners, Swender & Duncan, 1998). But as Lightbown

and Spada (1999) point out, the goals and context of an educational program and the typological similarities or

differences between students home language and the FL being studied are important factors in deciding on

the age issue and the total number of hours of instruction necessary to reach mandated levels. If native-like

proficiency is not sought, then introducing the FL in late childhood may be quite sufficient, depending of course

on students motivation, teachers, and so on. Experiencing several years of rather minimal language instruction

and then finding oneself back in classes with beginners in secondary or postsecondary programs is highly

undesirable. Regardless, more longitudinal research is needed to study this issue, looking not only at FL

learning outcomes but also school retention, subject matter proficiency, and continuation to higher education

(Tucker, 2001).

This rush to implement policies introducing FLs earlier has been as problematic in some parts of

Canada as it has been elsewhere (e.g., Reeder et al., 1997). British Columbia, the westernmost

province in Canada, in the mid- to-late 1990s introduced a new language education policy for school-

aged children that required that they study a FL (generally French, but with possibilities for Spanish,

German, Mandarin, Punjabi or Japanese if schools could offer one or more of these languages) from

Grade 5 (elementary school) up to Grade 8; FL study is optional earlier and later, depending on school

resources and students interests, and students may also switch to other FLs along the way (e.g., Grade

9, 11). Formerly, instruction had begun at Grade 8 (secondary school). Unfortunately, there is still very

little room in most generalist elementary and middle-school teachers university programs for FL study

or for courses in FL teaching methods. Furthermore, appropriate assessment practices (of both

teachers and students FL proficiency) and ways of articulating teaching across kindergarten through

postsecondary curriculum have not always accompanied these new policies. Whereas the policy may

mandate the teaching of oral language in particular in a communicative, experiential way, as in Canada,

the high school matriculation exams still contain discrete-point items (multiple choice, true-false) that

reflect traditional methods from another era and do not assess students aural-oral skills. Because high-

stakes testing often determines what is taught and how it is taught, regardless of the mandated

curriculum, this kind of mismatch or negative washback undermines curricular reform efforts, just as

TOEFL does when used inappropriately as a measure of students achievement in some university FL

programs in Asia.

Research shows that while the promotion of FL education--and second languages, such as

English, in immigrant -receiving, English-dominant countries--is associated with potential gains

in students cognitive, sociocultural, and linguistic development (Genesee, 1987), FL education

should not be undertaken at the expense of students indigenous/home languages and their

prior literacy development in those languages (Snow, 2001); that is, it should be an additive as

opposed to subtractive learning experience for them (Tucker, 2001). In addition, considerable

research shows that the same immigrant students require many years of English-as-a-second

language support in order to attain the level of academic language proficiency of their native-

speaker peers (Cummins, 2000), although they are often mainstreamed or transitioned into

English-medium programs prematurely, after one year of ESL coursework, for example.

FL Research Agendas

A number of recent FL research agenda documents provide a helpful starting point for analyzing national

and regional FL language education priorities (e.g., Duff & Bailey, 2001; Lambert, 2001; Perspectives

essays on language policy in two issues of the Modern Language Journal in 2003). The aforementioned

age issue is a major research priority at present. In addition, Lambert (2001), as Director of the National

Foreign Language Center at the University of Maryland in the United States, identified seven priorities

Duff, p. 6

for FL instructional reform and related research in the US, based on comparisons with

innovations in Europe and with his earlier review of FL instructional needs in the US (Lambert,

1987). The seven areas included the following:

evaluating language competency;

articulating instruction across educational levels and the different contexts in which

FLs are taught;

increasing the range of languages taught and studied;

achieving higher levels of language skills;

promoting language competency and use among adults;

expanding research and maximizing its impact on FL teaching and learning;

assessing and diffusing new technologies in instructional practice

(p. 347)

The following sections expand on these points, adding related recommendations from other

language education scholars both inside and outside the United States (e.g., Pufahl et al., 2000).

Assessment/Evaluation

Several concerns related to assessment/evaluation are that there is little coordination internationally in

assessment or testing initiatives. Lambert (2001) observed, and many would agree, that the widespread

adoption of the American Council on the Teaching of Foreign Languages (ACTFL) proficiency standards,

testing protocols, and rating scales in the U.S. has helped standardize and modernize language teaching

methods there, particularly at the postsecondary level. The emphasis on oral proficiency and on the ability

to speak about a range of topics accurately and fluently on the Oral Proficiency Interview has motivated

teachers and students to pay more attention to oral skills in their courses and less on text translation than

was previously the case. However, according to Lambert, more coordination between FL curriculum

development and evaluation in the US and in Europe should take place. For example, under the direction

of the Council of Europe (2001), an impressive, functional approach to task-based teaching and

assessment has been developed in Europe for at least 20 foreign languages across a wide range of

proficiency levels. The Common European Framework is now guiding language teaching policies in most

countries in the European Union but is not well known in North American FL education or policy circles.

In contrast with the European situation, a general concern in Canadian and American k-adult FL

teaching and assessment is that the curriculum tends to be bottom heavy; that is, it is oriented toward

basic as opposed to advanced levels of proficiency. Students simply do not spend enough quality time

(i.e., total hours) building up a substantive knowledge of any given FL. Research by Higgs and Clifford

(1982) some years ago concluded that most FL majors at American universities graduate with a 2+ (or

terminal 2) rating on a 5-point proficiency scale. The criticism of underachievement and low standards

holds true for some Canadian FL policy documents and curricula as well; e.g., in British Columbia,

scholars have expressed concern that the stated goals of FL education are primarily attitudinal and

cultural (understanding ourselves and others better), downplaying the goals of advanced FL learning,

except in the case of French immersion (Reeder et al., 1997).

Articulation Issues

Most analyses of FL education in Canada, the United States, and other countries (e.g., Britain), underscore

problems of articulation between FL teaching at the elementary, secondary and postsecondary levels. That is,

there is too little attention paid to how instruction at one level relates to the next or how students with previous

FL coursework will be incorporated into the system, for example at university (e.g., Pufahl et al., 2000;

Lambert, 2001). With the recent increase in numbers of students in elementary school foreign language

programs, the need for articulation with secondary or high school curricula is all

Duff, p. 7

the more acute. Similarly, articulation between coursework for heritage language (HL)

background students and coursework for their non-HL counterparts is needed. For example, if

these groups are segregated for the first two years of study but then are merged in the third

year of university, the curriculum should be made equally accessible to both groups and not

cater primarily to the HL students as currently happens with Mandarin instruction at the

University of British Columbia (Li, 2003). In other universities, this merger may happen from as

early as the second semester, leading to attrition among disheartened non-HL students.

Another articulation issue is that in North American contexts, university students are all too often

simply assigned to first-year (elementary) courses regardless of their high school FL studies. The

combination of this tendency with the one requiring FL coursework in only the first or second years

at most high schools and universities, if at all, means that the number and type of advanced-level

courses (i.e. not just FL literature courses) is very limited and students are given little credit for their

past FL learning. Indeed, Lambert (2001, citing statistics from Draper & Hicks, 1993) reports that the

majority of FL students in the U.S. are in first year courses only; less than 10% in 1994 were enrolled

in Level 3 or higher courses; and 3% or fewer graduating high school students have taken advanced

FL/literature courses in French, German, or Spanish (the most commonly taught FLs in the U.S).

Another articulation issue is evident in Asian countries that have recently introduced communicative

language teaching stressing games and oral skills at the elementary school level but then revert to a

very traditional grammar-based or translation-oriented approach at the junior high school level,

students are often very dismayed by the contrast in approaches, curriculum, and assessment.

Lifelong Language Learning

As lifelong learning becomes the hallmark of education in the 21

st

century, it is also important to

recognize and enhance the potential and real cumulative effects of FL study across a range of

educational and work experiences. For both commonly taught (e.g., French, Spanish) and less commonly

taught FLs in North America (Arabic, Japanese), greater opportunities must be provided for adult

vocationally-oriented FL learning for various professions, whether with the government or private sector.

In addition, autonomous and other (e.g. distance/electronic, study-abroad/immersion) formats for adult FL

learners should be developed and made more readily accessible to prospective students to allow them to

continue their FL study according to their current needs and interests. Attrition in students FL knowledge

is a very real problem when they no longer study or use the FL, particularly when students original levels

of FL achievement are modest; but with additional exposure and instruction, their prior learning may be

refreshed and retrieved. Lifelong language/culture learning is particularly important for the ongoing

professional and linguistic development of FL teachers themselves.

Language Choice

Most countries emphasize the study of just a small number of key FLs, such as English, French, Spanish,

or Japanese, depending on the country. The selection of languages for FL education and for policies is

often highly political and politicized (e.g., the offering of Mandarin, Punjabi, Spanish, German, and

Japanese for British Columbia public schools, in addition to French, reflected at least in part the advocacy

efforts of the Mandarin- and Punjabi-speaking communities locallyand the orthography to be taught for

Mandarin was also influenced by the wishes of the local Taiwanese community: i.e. favoring traditional

over simplified characters). Languages may be selected because of the countrys colonial legacy, the

heritage of its founding or major immigrant groups, international trends in higher education, or because of

perceived economic advantages to selecting the language of a major trading partner. Regardless,

languages chosen for study shift with the political and demographic winds.

Duff, p. 8

French, German, and Latin half a century ago were widely studied in the United States. However, now

Spanish and French are most commonly studied and German and Latin are declining significantly; more

than half of all U.S. FL enrollments are in Spanish (both HL and non-HL students; Lambert, 2001).

Interest in less commonly taught non-Western languages is increasing especially along east and west

coasts, at both Canadian and American universities. In non-English-dominant countries in Europe (e.g.,

Austria, Czech Republic, Finland, Germany, Italy, etc.), Asia (Thailand, Japan, China), and South

America (Chile, Peru), English is commonly the first FL that majority-language students learn (Pufahl et

al., 2000). With its close proximity to east and southeast Asian countries and economies and its rich

history of immigration and multiculturalism, Australia recognizes the importance of Asian languages by

promoting the study of Japanese, Indonesian, Mandarin, and Korean and other community FLs from

earlier waves of immigration to that country (Greek, Italian).

Regardless of which FLs may be most commonly studied, it is in a countrys best interests to have

speakers proficient in many different languages, including having high levels of literacy in their home

languages, and not only the languages of the major world powers of the day. In Vancouver public

schools, more than 100 languages are spoken by children and their families. Having community

members, children, and teachers proficient in many of those languages is clearly a tremendous

asset when communicating within multi-generational family units and with other representatives of

those communities. The disadvantage to trying to teach some of these community languages is that

up-to-date, attractive and pedagogically sound materials may be very hard to come by (e.g., for

teaching Punjabi in British Columbia), when compared with Japanese, French, Spanish or German.

Professional publishers, moreover, are mostly interested in investing in the publication of materials

for which large markets exist, which rules out many of the smaller language groups. Similarly,

producing high quality assessment materials may be very expensive for ministries of education when

the numbers of students for a particular language are relatively small.

The differences (e.g., grammatical, orthographic, phonological) between students first and target FLs do

however have implications for the time in which the FL can reasonably be mastered. One very interesting

area of research in the early 1980s, but not replicated since, was conducted at the (American) Foreign

Service Institute (Liskin-Gasparro, 1982). It compared how long, in terms of total number of hours, it took

English-speaking adults to achieve various levels of proficiency in very different types of FLs. They found,

for example, that average-aptitude learners in the intensive programs reached 2+ (advanced level) on a

5-point scale after 24 weeks (720 hours) when learning Spanish, Italian or Portuguese; but that to reach

comparable levels of proficiency in Hindi, Indonesian, Thai, Vietnamese, and even German, it took about

44 weeks (1320 hours); and in excess of 44 weeks (up to 92 weeks, or 2760 hours) for Chinese,

Japanese or Korean. This finding cautions us to have realistic expectations about student learning

outcomes with typologically unrelated FLs (such as English and Mandarin), given the number of hours

students normally are instructed in those languages.

Technology and Distance Learning

Computer and other audio-visual media use in FL learning in the past often provided just an expensive

alternative to the traditional language laboratory and a new medium for practicing the same old mechanical

pattern drills. However, there is now a more sophisticated and wider use of computers for linking communities

of FL users via the internet, for engaging in Web-CT discussion forums and bulletin boards (through both

synchronous and asynchronous means), and for providing learners access to current, authentic materials in

the FL (newspapers, travel information, editorials, hypertexts) in addition to other forms of Computer Assisted

Language Learning (CALL) (e.g., Warschauer & Kern, 2000). CALL represents a huge area of growth for FL

educationand also for preservice and inservice teacher education--and one on which more research needs

to be conducted. Some of the most impressive features of CALL and Web- and Internet-based learning are as

follows: (1) students exposure to meaningful, current texts and learning tools in the target-language (oral and

written) can be greatly enhanced and can

Duff, p. 9

be directed by the students own interests and needs; (2) learners can be linked to other users (and learners)

of the FL, thus increasing their motivation as well as opportunities to negotiate meaning and multiple registers

of discourse through their existing or shared linguistic means; (3) many of the materials can be accessed with

minimal cost to the user, provided that computers with internet access are available; and (4) through firsthand

encounters with multimedia and other human/material resources, students have more opportunities to engage

with their own and other cultures more deeply and more immediately.

Some advances in the use of technology for FL teaching in Europe are as follows. In Denmark, students

use English (their FL) to communicate with schools in countries where English is either the first language

or a FL but where students proficiency is comparable to that of the Danish students (e.g., the

Netherlands). In Spain, through the COMENIUS initiative, more than 100,000 Catalonian students

participate in EU-sponsored programs that create school partnerships that network students from three

schools in three different European countries; collaborative projects include project diaries, Web sites,

CD-ROMS, and one or more of the FLs of each participating school is used (Pufahl et al., 2000).

Networks work on projects related to environmental issues, for example. In Luxembourg, through a

different program, a word processor has been developed to help students develop literacy and oral

fluency in all three official languages through narrative activities from as early as preschool.

As a general research priority, however (e.g., technology is considered one of the TESOL

International Research Foundations urgent priorities), the cost-benefit ratio of technology and

issues of accessibility to technology in resource-poor countries must be examined more closely;

furthermore, the advantages of technology use over more traditional tools must be demonstrated. In

addition, ways in which teachers can maximize the benefits of technology must be examined.

Doughty and Long (2003b) outline a number of FL teaching principles below with recommendations for

regular FL classroom implementation and CALL implementation (see Appendix 2). Although their stance

regarding the status of texts (see MP1) is extreme and one with which I am not in full agreement, their

emphasis of having students be actively engaged in using language for transactional purposes, rather

than simply be decoders of existing, static texts, is very appropriate in many FL learning contexts. Similar

research-based pedagogical principles can be found in Lightbown and Spada (1999). Based on extensive

research in second language acquisition over the past two decades, Doughty and Long stress the

importance of providing rich input to FL learners, many opportunities to produce language (output)

actively orally and in writing, strategically providing corrective feedback (from a teacher or peer

research shows that peers working collaboratively more often than not provide correct feedback to one

another), instruction on accurate grammatical structures in meaningful discourse contexts,

cooperative/collaborative learning, and an understanding that learners with different types of aptitude,

motivation, and at different ages may acquire the FL at different paces and in different manners (e.g.,

highly analytic vs. highly synthetic or chunk-based); therefore, opportunities for autonomous language

learning through the use of technology by catering to the learners styles and needs are in order. Finally,

although not outlined in Appendix 2 (Table 1), pragmatic aspects of language learning are often

overlooked in FL education and research; as important as reasonably accurate pronunciation, grammar,

and vocabulary are, so too is effective FL pragmatics, or the expression of politeness, through speech

acts expressing gratitude, making requests, complaints, or apologies, and so on, and framing ones oral

and written discourse at the appropriate level of formality for the context and using appropriate genres.

Content-based, Theme-based, and Immersion FL Education

In many FL curriculum guidelines (e.g., in British Columbia, US Standards, Council of Europe, 2001),

language learning has multiple components including learning how to express oneself orally and in

writing with other speakers of the FL, engaging with creative works in the FL, and gaining new

information (e.g., through the internet). Project-based learning approaches also emphasize content and,

in some cases, the integration of FL learning with the learning of other subject matter (e.g., mathematics,

Duff, p. 10

social science, science); an example would be a unit on South American rainforests that

includes discussions of the weather, animal life, geography, people, economic activity,

deforestation, and so on, depending on the level of students.

Much successful FL instruction that goes beyond basic communicative methodology deals with content

(e.g., environmental issues, sociolinguistics) in a more sustained way than is often reflected in

international FL textbook series, embedding the learning of language within a larger educational context,

where issues--and not just stereotypes--can be examined and explored. There are many variants of

content-based learning, but one relatively new approach is immersion or bilingual education (as it is

called in Europe), for which Canada is well known. FL immersion allows students to begin learning a FL

from as early as kindergarten in an experiential-communicative way, with highly proficient teachers

delivering not only language instruction but also the rest of the curriculum through the medium of the FL.

In Canada, the FL immersion normally involves French as a FL, for which the most trained teachers,

funding, materials, demand, and political will exist; there are Mandarin and other immersion programs

(e.g., Ukrainian) in public schools in Vancouver, Edmonton, and Toronto. French immersion, both in its

early and late-immersion models (from Grade 6), remains a very popular choice for hundreds of

thousands of Canadian students a year, and not only those whose first language is English.

The results of nearly four decades of French immersion research in Canada and, more recently

elsewhere (e.g., English in Japan and the Netherlands; Spanish in Hungary; French, Spanish, and

Japanese in USA; Swedish in Finland) attest to the success of this model in producing graduates who

are more proficient in French than those studying the FL as a regular subject, and whose English (or L1)

skills and competency in other subjects are not compromised as a result of this FL immersion

experience; on the contrary, they often outperform their monolingual peers in first-language literacy and

subject matter (Canadian Parents for French, 2003; Johnson & Swain, 1997; Harley, Allen, Cummins &

Swain, 1990) . Notwithstanding the massive public and academic support for immersion, research shows

that this model works successfully only if certain basic conditions are met: excellent teacher education,

teachers with high levels of FL proficiency, and the availability of suitable curriculum materials and

support in the FL. In other words, money and careful planning are needed. In Hungary in the late 1980s a

Canadian model of immersion or bilingualism was introduced for the teaching of several European

languages from the 9

th

grade, including English, Spanish, Italian, and French, and Russian, that in most

cases proved both popular and successful (Duff, 1997). In the United States, immersion education and its

variants (e.g., two-way immersion/bilingualism where students learn each others languages, e.g.,

English-Spanish) have spread from early implementation in a suburb of Los Angeles to schools in

Minnesota, Oregon, Maryland, and elsewhere, to literally hundreds of schools.

Task Planning and Design, and First-language Use

Two other areas of current research and curriculum development in FL education are connected

with (1) coherent and comprehensive task design and (2) the extent to which students first

language should be used by teachers and students in FL classrooms. A number of applied

linguistics scholars see method as less helpful a construct in FL curriculum design than looking at

the sequencing of interrelated tasks, with careful attention paid to the skills and subcomponents of

tasks (e.g., planning a trip to a city in another country) and how they relate to prior learning. Tapping

into students existing linguistic and nonlinguistic knowledge prior to having them undertake tasks,

engaging them in problem-solving with peers, and then planning presentations or written products

are all important. Also important is having them do relevant follow-up activities (often involving other

skills, e.g., writing as opposed to listening/speaking) following the original task to consolidate and

extend their linguistic and content knowledge (Skehan, 1998; Hadley, 2000).

The issue of first-language use has also received attention in FL education research recently, particularly

after early research revealed that, at least at the postsecondary level, FLs were used far less in some FL

Duff, p. 11

classes than the students first language wassometimes as little as 10% of the time (Duff & Polio,

1990; Polio & Duff, 1994). Since that early research, many researchers have considered the

advantages of some (limited) use of students first languages and also ways of increasing FL use in

classes, whatever the grade level. But maximal use of the target language is still highly desirable.

Research and Curricular Innovation

The establishment of a National Foreign Language Center and a number of other Title-VI language

research and resource centers in the U.S. over the past decade (e.g., in Maryland, Hawaii, Minnesota,

Pennsylvania), in addition to the existing Center for Applied Linguistics, has greatly facilitated research,

innovation, and dissemination related to FL learning at least in North America. Projects have started to

investigate differences in ultimate attainment possible for heritage vs. non-heritage language learners, for

example, and much more attention is being paid to curriculum development for less commonly taught

languages. Other research has examined study-abroad FL learning experiences and foreign language

skill attrition (Lambert, 2001). The applied linguistic academic community has also produced many recent

handbooks and comprehensive volumes summarizing the state of second language acquisition research

(Ellis, 1994; Doughty & Long, 2003a). Much of this research, however, has concerned English as a

second/foreign language at the college level and is highly technical. Less applied research has examined

EFL internationally in k-12 settings or the teaching and learning of non-European languages. Because of

the lack of a comprehensive research agenda for English as a foreign language, the TESOL organization

in the late 1990s commissioned the drafting of one (

http://www.tesol.org/assoc/bd/0006researchagenda03.html). Around the same time, the TESOL

International Research Foundation (http://www.tirfonline.org), a non-profit educational foundation based in

the United States but with an international Board membership, began to commission short position pieces

on critical research priorities for EFL (Duff & Bailey, 2001). The foundation was urged to focus on the

issues of (1) learners age, (2) teachers FL proficiency, and (3) technology for its first rounds of

international competitions for collaborative, multinational, multimethod research. It is hoped that with

these new networks of research nationally and internationally, greater dissemination of both research

findings and curricular innovations will take place in the future.

Conclusion

This paper has highlighted current issues in FL policy, research, and instructional practice. Although

standards and common assessment metrics have been discussed, most scholars concede that one

size (or method, or solution) does notindeed, cannot--fit all FL education situations. Policy and

curriculum must be decided within each socio-educational context. However, we should learn from

one anothers experiences with FL education, reform, and research. At least some themes seem to

be fairly universal: the importance of cross-program articulation, assessment, teacher education in

both FL proficiency and appropriate teaching methods and materials; consideration for the timing,

duration, intensity and content of FL teaching; the effective use of technology and other media; and

the need to pay attention to the skill areas most needed by students for their ultimate FL purposes.

In addition, it is imperative that more quantitative and qualitative longitudinal research on FL

education be conducted internationally across a wide range of languages and programs. Most of all,

it is up to the public to recognize that languages are of vital importance to contemporary societies

and that FL learning can expand peoples horizons and opportunities immeasurably.

References

Brecht, R. & Ingold, C. (2002). Tapping a national resource: Heritage languages in the United States.

ERIC Digest EDO-FL-02-02. Washington, DC: Center for Applied Linguistics/ERIC.

Duff, p. 12

Brecht, R., & Rivers, W. (2001). Language and national security: The federal role in building language

capacity in the U.S. University of Maryland: National Foreign Language Center. Retrieved from

the World Wide Web on Jan. 5, 2004 at http://www.nflc.org/security/lang_security.htm

Brinton, D. & Kagan, O. (Eds.). (in press). Heritage language education. Mahwah, NJ:

Lawrence Erlbaum.

Brown, H.D. (2000). Principles of language learning and teaching. 4

th

ed. Englewood Cliffs, NJ:

Prentice Hall Regents.

Byrnes, H. (Ed.). (1998). Learning foreign and second languages: Perspectives in research

and scholarship. New York: Modern Language Association of America.

Canadian Parents for French. (2003). The state of French second language education in

Canada, 2003. Ottawa: Canadian Parents for French.

Council of Europe (2001). Common European Framework of Reference for Languages: Learning,

Teaching, Assessment. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Retrieved from the World

Wide Web Dec. 31, 2003 at http://culture2.coe.int/portfolio//documents/0521803136txt.pdf.

Cummins, J. (2000). Language, power and pedagogy. Clevedon, UK: Multilingual Matters.

Doughty, C., & Long, M.H. (2003a). The handbook of second language acquisition. Malden, MA:

Blackwell.

Doughty, C., & Long, M.H. (2003b). Optimal psycholinguistic environments for distance

foreign language learning. Language Learning & Technology, 7, 50-80.

Draper, J.B., & Hicks, J.H. (1993). Foreign language enrollments in public secondary schools, fall, 1984.

Foreign Language Annals, 29, 304-306.

Duff, P. (1997). Immersion in Hungary: an EFL experiment. In R.K. Johnson & M. Swain (Eds.),

Immersion education: International perspectives (pp. 19-43). New York: Cambridge

University Press.

Duff, P. (in press). Heritage language education in Canada. In D. Brinton & O. Kagan (Eds.),

Heritage language education. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Duff, P. & Bailey, K.M. (Eds.). (2001). Identifying research priorities: Themes and directions

for the TESOL International Research Foundation. TESOL Quarterly, 35, 595-616.

Duff, P., & Polio, C. (1990). How much foreign language is there in the foreign language classroom?

The Modern Language Journal, 74, 154-166.

Ellis, R. (1994). The study of second language acquisition. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Genesee, F. (1987). Learning through two languages. New York: Newbury House.

Hadley, A.O. (2001). Teaching language in context. (3

rd

ed.). Boston: Heinle & Heinle. Harley,

B., Allen, P., Cummins, J., Swain, M. (Eds.). (1991). The development of second language

proficiency. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Higgs, T., & Clifford, R. (1982). The push toward communication. In T. Higgs (Ed.), Curriculum,

competence, and the foreign language teacher. ACTFL Foreign Language Education

Series, vol. 13. Lincolnwood, IL: National Textbook Company.

Johnson, R.K. & Swain, M. (Eds). (1997). Immersion education: International perspectives.

Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Lambert, R.D. (1987). The case for a National Foreign Language Center: An editorial. Modern

Language Journal, 71, 1-11.

Lambert, R. D. (2001). Updating the foreign language agenda. Modern Language Journal, 85, 347-362. Li,

D. (2003). Issues in heritage language education. Presentation in the Department of Language and

Literacy Education, University of British Columbia.

Lightbown, P. (2000). Anniversary article: Classroom SLA research and second language

teaching. Applied Linguistics, 21, 431-462.

Lightbown, P. (2001). L2 instruction: Time to teach. TESOL Quarterly, 35, 598-599.

Lightbown, P., & Spada, N. (1999). How languages are learned. (2

nd

ed.). Oxford: Oxford

University Press.

Liskin-Gasparro, J. (1982). ETS oral proficiency testing manual. Princeton, NJ:

Educational Testing Service.

Duff, p. 13

Phillips, J. (2003). Implications of language education policies for language study in

schools and universities. Modern Language Journal, 87, 579-586.

Polio, C., & Duff, P. (1994). Teachers' language use in university foreign language classrooms:

A qualitative analysis of English and target language alternation. Modern Language

Journal, 78, 313-26.

Pufahl, I., Rhodes, N.C., & Christian, D. (2000). Foreign language teaching: What the United

States can learn from other countries. Eric Document ED-00-PO-4609. Retrieved from

the World Wide Web on Dec. 20, 2003.

Reeder, K., Hasebe-Ludt, E., & Thomas, L. (1997). Taking the next steps: Toward a coherent language

education policy for British Columbia. Canadian Modern Language Review, 53, 373-402.

Rosenbusch, M. (1995). Guidelines for starting an elementary school foreign language program.

Center for Applied Linguistics. ERIC Digest #EDO-FL-95-09. Retrieved from the World

Wide Web Dec. 31, 2003, http://www.cal.org/resources/digest/rosenb01.html

Skehan, P. (1998). A cognitive approach to language learning. Oxford, England: Oxford

University Press.

Snow, C. (2001). Learning to read in an L2. TESOL Quarterly, 35, 599-601.

Standards for foreign language learning: Preparing for the 21st century. (1996). Lawrence,

KS: Allen Press.

Statistics Canada (2001). Population by mother tongue, provinces and territories. Retrieved from

the World Wide Web Dec. 5, 2003 at http://www.statcan.ca/english/Pgdb/demo18a.htm.

Swender, E., & Duncan, G. (1998). ACTFL performance guidelines for K-12 learners. Foreign

Language Annals, 31, 479-491.

Tucker, G.R. (2001). Age of beginning instruction. TESOL Quarterly, 35, 597-598.

Warschauer, M., & Kern, R. (Eds.). (2000). Network-based language teaching: Concepts and

practice. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Duff, p. 14

Appendix 1

Standards for Foreign Language Learning in the United States (Standards, 1996)

Communication

Communicate in Languages Other Than English

Standard 1.1: Students engage in conversations, provide and obtain information, express

feelings and emotions, and exchange opinions.

Standard 1.2: Students understand and interpret written and spoken language on a variety of

topics. Standard 1.3: Students present information, concepts, and ideas to an audience of

listeners or readers on a variety of topics.

Cultures

Gain Knowledge and Understanding of Other Cultures

Standard 2.1: Students demonstrate an understanding of the relationship between the

practices and perspectives of the culture studied.

Standard 2.2: Students demonstrate an understanding of the relationship between the

products and perspectives of the culture studied.

Connections

Connect with Other Disciplines and Acquire Information.

Standard 3.1: Students reinforce and further their knowledge of other disciplines through

the foreign language.

Standard 3.2: Students acquire information and recognize the distinctive viewpoints that

are only available through the foreign language and its cultures.

Comparisons

Develop Insight into the Nature of Language and Culture

Standard 4.1: Students demonstrate understanding of the nature of language through

comparisons of the language studied and their own.

Standard 4.2: Students demonstrate understanding of the concept of culture through

comparisons of the cultures studied and their own.

Communities

Participate in Multilingual Communities at Home & Around the World

Standard 5.1: Students use the language both within and beyond the school setting.

Standard 5.2: Students show evidence of becoming life-long learners by using the language

for personal enjoyment and enrichment.

Duff, p. 15

Appendix 2

Table 1. Language Teaching Methodological Principles for CALL (Doughty & Long, 2003b, p. 52)

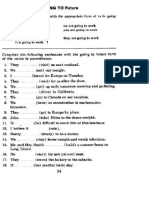

Principles L2 Implementation CALL Implementation

ACTIVITIES

MP1 Use tasks, not texts, as the task-based language teaching

simulations; tutorials;

unit of analysis. (TBLT; target tasks, pedagogical worldware

MP2 Promote learning by tasks, task sequencing)

doing.

INPUT

MP3 Elaborate input (do not negotiation of meaning; computer-mediated

simplify; do not rely interactional modification; communication /

solely on "authentic" elaboration discussion; authoring

texts).

MP4 Provide rich (not exposure to varied input sources corpora; concordancing

impoverished) input.

LEARNING

PROCESSES

MP5 Encourage inductive implicit instruction design and coding

("chunk") learning. features

MP6 Focus on form. attention; form-function mapping design and coding

features

MP7 Provide negative feedback on error (e.g., recasts); response feedback

feedback. error "correction"

MP8 Respect "learner timing of pedagogical adaptivity

syllabuses"/developmenta intervention to developmental

l processes. readiness

MP9 Promote cooperative/ negotiation of meaning; problem-solving;

collaborative learning. interactional modification computer-mediated

communication /

discussion

LEARNERS

MP10 Individualize instruction needs analysis; consideration of branching; adaptivity;

(according to individual differences (e.g., autonomous learning

communicative needs, and memory and aptitude) and

psycholinguistically). learning strategies

Duff, p. 16

Patricia A. Duff is Associate Professor of Language and Literacy Education at the University of British

Columbia, Vancouver, Canada. She is Director of UBCs Centre for Intercultural Language Studies, the

Director of Modern Language Education, and the Coordinator of the Graduate Program in Teaching

English as a Second Language. She serves on the Executive Committee of the American Association for

Applied Linguistics, chairs the Research Advisory Committee for the TESOL International Research

Foundation, and is a member of several editorial boards, including the TESOL Quarterly (as editor of the

Research Issues section), the Canadian Modern Language Review (associate editor), the Modern

Language Journal, and the Annual Review of Applied Linguistics (editorial director). Dr. Duff has also

served as Chair of the TESOL Research Interest Section. Her research, funded by a number of national

and international grants, is in the areas of second/foreign language instruction, language acquisition and

socialization, second language classroom interaction, task-based language teaching and learning,

research methods, and the integration of language learners into mainstream educational and workplace

environments. Her publications have appeared (or are in press) in Studies in Second Language

Acquisition, the Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, Modern Language Journal,

TESOL Quarterly, Canadian Modern Language Review, Applied Linguistics, System, Linguistics and