Professional Documents

Culture Documents

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

180 viewsMexico Gawronski, Vincent

Mexico Gawronski, Vincent

Uploaded by

Pedro J. Valencia GaleanoJSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content. Where does the Mexican Revolution now reside in collective memory? and does the idea of The Revolution still have any legitimating power?

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You might also like

- Mexico's Once and Future Revolution by Gilbert M. Joseph and Jürgen BuchenauDocument22 pagesMexico's Once and Future Revolution by Gilbert M. Joseph and Jürgen BuchenauDuke University Press43% (7)

- Idolatry and Iconoclasm in Revolutionary MexicoDocument35 pagesIdolatry and Iconoclasm in Revolutionary MexicorenatebeNo ratings yet

- Duke University PressDocument38 pagesDuke University PressJosep Romans FontacabaNo ratings yet

- Mary Kay Vaughan1Document38 pagesMary Kay Vaughan1Orisel CastroNo ratings yet

- Gilbert M. Joseph, Jürgen Buchenau - Mexico's Once and Future Revolution - Social Upheaval and The Challenge of Rule Since The Late Nineteenth Century-Duke University Press (2013)Document263 pagesGilbert M. Joseph, Jürgen Buchenau - Mexico's Once and Future Revolution - Social Upheaval and The Challenge of Rule Since The Late Nineteenth Century-Duke University Press (2013)Lourdes FloresNo ratings yet

- Paul Lawrence Haber - Power From Experience Urban Popular Movements in Late Twentieth Century MexicoDocument297 pagesPaul Lawrence Haber - Power From Experience Urban Popular Movements in Late Twentieth Century MexicoRicardo13456No ratings yet

- Thesis Final-Wilton On TlatelolcoDocument60 pagesThesis Final-Wilton On TlatelolcoSir BrokenNo ratings yet

- Mexican Indigenous LanguagesDocument396 pagesMexican Indigenous Languagesmausj100% (2)

- Bandidaje 10 PDFDocument53 pagesBandidaje 10 PDFanon_243369186No ratings yet

- Polar 05Document19 pagesPolar 05Lana GitarićNo ratings yet

- Violence, Coercion, and State-Making in Twentieth-Century Mexico: The Other Half of the CentaurFrom EverandViolence, Coercion, and State-Making in Twentieth-Century Mexico: The Other Half of the CentaurNo ratings yet

- Neoliberal MulticulturalismDocument20 pagesNeoliberal MulticulturalismRodrigo Megchún RiveraNo ratings yet

- Centrum Voor Studie en Documentatie Van Latijns Amerika (CEDLA) European Review of Latin American and Caribbean Studies / Revista Europea de Estudios Latinoamericanos y Del CaribeDocument4 pagesCentrum Voor Studie en Documentatie Van Latijns Amerika (CEDLA) European Review of Latin American and Caribbean Studies / Revista Europea de Estudios Latinoamericanos y Del CaribeCarolina TinajeroNo ratings yet

- Venezuela's Socialismo: Cuando Comenzó?Document10 pagesVenezuela's Socialismo: Cuando Comenzó?Pam MartinezNo ratings yet

- Postcolonial and Anti-Systemic Resistance by Indigenous Movements in MexicoDocument27 pagesPostcolonial and Anti-Systemic Resistance by Indigenous Movements in MexicoPeter RossetNo ratings yet

- Booth - Hegemonic - Nationalism - Subordinate - Marxism - The - Mexican - Left - 19457Document28 pagesBooth - Hegemonic - Nationalism - Subordinate - Marxism - The - Mexican - Left - 19457narrehlNo ratings yet

- The Mexican Revolution: Federal Expenditure and Social Change since 1910From EverandThe Mexican Revolution: Federal Expenditure and Social Change since 1910No ratings yet

- Bockman CSSH 2019 PDFDocument26 pagesBockman CSSH 2019 PDFrcarocNo ratings yet

- 2.3 Thomson (1991) - Apectos Del Liberalismo en MéxicoDocument29 pages2.3 Thomson (1991) - Apectos Del Liberalismo en MéxicoSantiago RicoNo ratings yet

- Knigth. Myth of The RevolutionDocument52 pagesKnigth. Myth of The RevolutionAlfonso GANo ratings yet

- Social Justice/Global OptionsDocument5 pagesSocial Justice/Global OptionsAlanaNo ratings yet

- Revolution within the Revolution: Cotton Textile Workers and the Mexican Labor Regime, 1910-1923From EverandRevolution within the Revolution: Cotton Textile Workers and the Mexican Labor Regime, 1910-1923No ratings yet

- Mexican Revolution Research PaperDocument8 pagesMexican Revolution Research Paperafeayaczb100% (1)

- Goldfrank TheoriesRevolutionRevolution 1979Document32 pagesGoldfrank TheoriesRevolutionRevolution 1979Angelica ReyesNo ratings yet

- Charles Hale El Indio PermitidoDocument19 pagesCharles Hale El Indio Permitidoemanoel.barrosNo ratings yet

- Making Revolution in Rural Cold WarDocument15 pagesMaking Revolution in Rural Cold WarluissceNo ratings yet

- CHERNILO Beyond The Nation or Back To It (2020)Document29 pagesCHERNILO Beyond The Nation or Back To It (2020)heycisco1979No ratings yet

- Hallin Decodificado (1) 2Document20 pagesHallin Decodificado (1) 2Abraham ZavalaNo ratings yet

- Incomplete Democracy: Political Democratization in Chile and Latin AmericaFrom EverandIncomplete Democracy: Political Democratization in Chile and Latin AmericaNo ratings yet

- Charles Hale-NeoliberalDocument19 pagesCharles Hale-Neoliberalkaatiiap9221100% (1)

- Theorizing The Cuban RevolutionDocument16 pagesTheorizing The Cuban Revolutionfermtzmqz202No ratings yet

- Mexicans in Revolution 1910 1946Document201 pagesMexicans in Revolution 1910 1946Zoran PetakovNo ratings yet

- The Making of Law: The Supreme Court and Labor Legislation in Mexico, 1875–1931From EverandThe Making of Law: The Supreme Court and Labor Legislation in Mexico, 1875–1931No ratings yet

- Capitulo 1 SellersDocument20 pagesCapitulo 1 SellersLaura Garcia RincónNo ratings yet

- Neoliberal MulticulturalismDocument20 pagesNeoliberal MulticulturalismNejua NahualtNo ratings yet

- Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México University of California Institute For Mexico and The United StatesDocument23 pagesUniversidad Nacional Autónoma de México University of California Institute For Mexico and The United StatesAlejandro OliveiraNo ratings yet

- The Death of Secular Messianism: Religion and Politics in an Age of Civilizational CrisisFrom EverandThe Death of Secular Messianism: Religion and Politics in an Age of Civilizational CrisisNo ratings yet

- A Brief History of NeoliberaliDocument8 pagesA Brief History of NeoliberaliMonique AssunçãoNo ratings yet

- 2 Camou. La Múltiple in GobernabilidadDocument31 pages2 Camou. La Múltiple in GobernabilidadLulu GlezNo ratings yet

- Mexican Culture MTDocument6 pagesMexican Culture MTfeg1962No ratings yet

- Stumbling Its Way through Mexico: The Early Years of the Communist InternationalFrom EverandStumbling Its Way through Mexico: The Early Years of the Communist InternationalNo ratings yet

- Foucault S Political Theologies and TheDocument9 pagesFoucault S Political Theologies and TheAngelik VasquezNo ratings yet

- Dual Transitions from Authoritarian Rule: Institutionalized Regimes in Chile and Mexico, 1970–2000From EverandDual Transitions from Authoritarian Rule: Institutionalized Regimes in Chile and Mexico, 1970–2000No ratings yet

- Neo-Constitutionalism in Twenty-First Century Venezuela: Participatory Democracy, Deconcentrated Decentralization or Centralized Populism?Document26 pagesNeo-Constitutionalism in Twenty-First Century Venezuela: Participatory Democracy, Deconcentrated Decentralization or Centralized Populism?Mily NaranjoNo ratings yet

- Sustaining Civil Society: Economic Change, Democracy, and the Social Construction of Citizenship in Latin AmericaFrom EverandSustaining Civil Society: Economic Change, Democracy, and the Social Construction of Citizenship in Latin AmericaNo ratings yet

- The Latin American Studies AssociationDocument33 pagesThe Latin American Studies AssociationMaria Catalina GomezNo ratings yet

- The Culture of Democracy and Bolivia's Indigenous MovementsDocument4 pagesThe Culture of Democracy and Bolivia's Indigenous MovementsGeorge RassiasNo ratings yet

- Ciclo Electoral y Políticas Públicas en Costa Rica - Jimenes (2001)Document33 pagesCiclo Electoral y Políticas Públicas en Costa Rica - Jimenes (2001)rosoriofNo ratings yet

- Theorizing Cuban RevolutionDocument16 pagesTheorizing Cuban RevolutionCarlos SandovalNo ratings yet

- The End of Catholic Mexico: Causes and Consequences of the Mexican Reforma (1855–1861)From EverandThe End of Catholic Mexico: Causes and Consequences of the Mexican Reforma (1855–1861)No ratings yet

- Mass Culture Reconsidered: DemocracyDocument16 pagesMass Culture Reconsidered: Democracypichi2No ratings yet

- The Political Psycology - Montero MaritzaDocument18 pagesThe Political Psycology - Montero MaritzaJenniffer MVNo ratings yet

- Revolución CubanaDocument16 pagesRevolución Cubanamichael.mendez.utlNo ratings yet

- Arturo Escobar. Latin America at A Crossroads: Alternative Modernizations, Postliberalism, or Postdevelopment?Document61 pagesArturo Escobar. Latin America at A Crossroads: Alternative Modernizations, Postliberalism, or Postdevelopment?karasakaNo ratings yet

- The Idea of a Liberal Theory: A Critique and ReconstructionFrom EverandThe Idea of a Liberal Theory: A Critique and ReconstructionRating: 2 out of 5 stars2/5 (1)

- Neopopulism Roberts KenethDocument36 pagesNeopopulism Roberts KenethdanekoneNo ratings yet

- Rodriguez IntelectsConstiticion1824Document13 pagesRodriguez IntelectsConstiticion1824Ramiro JaimesNo ratings yet

- The Erosion Democracy and CapitalismDocument18 pagesThe Erosion Democracy and CapitalismStebanNo ratings yet

- 5 Mexico Hernandez - Alicia1Document10 pages5 Mexico Hernandez - Alicia1carloseduardo5008No ratings yet

- Trade Union: What Is A Trade Union and What Are Relevant Laws in Pakistan For Trade Union Activities?Document5 pagesTrade Union: What Is A Trade Union and What Are Relevant Laws in Pakistan For Trade Union Activities?Abdul Samad ShaikhNo ratings yet

- Certified List of Candidates For Congressional and Local Positions For The May 13, 2013 2013 National, Local and Armm ElectionsDocument3 pagesCertified List of Candidates For Congressional and Local Positions For The May 13, 2013 2013 National, Local and Armm ElectionsSunStar Philippine NewsNo ratings yet

- Michigan Voter Guide 2012: November 6, 2012 General Election GuideDocument25 pagesMichigan Voter Guide 2012: November 6, 2012 General Election GuideMichigan Family ForumNo ratings yet

- Canadian Election Essay PDFDocument3 pagesCanadian Election Essay PDFapi-334823513No ratings yet

- BrexitDocument109 pagesBrexitpicalmNo ratings yet

- Initiatives Pour Influencer Les Elections Européennes 2014 (Open Society Soros)Document21 pagesInitiatives Pour Influencer Les Elections Européennes 2014 (Open Society Soros)Breizh Info50% (2)

- Ma. Ahlyssa O. Tolentino Student, BS Accountancy IIIDocument58 pagesMa. Ahlyssa O. Tolentino Student, BS Accountancy IIIJohn Kenneth Escober BentirNo ratings yet

- Classification of CitiesDocument2 pagesClassification of CitiesElsieRaquiñoNo ratings yet

- Letter To Appleton (WI) School Board Requesting Investigation On Teachers Who Bullied Benji Backer.Document3 pagesLetter To Appleton (WI) School Board Requesting Investigation On Teachers Who Bullied Benji Backer.Kyle MaichleNo ratings yet

- The Commission On ElectionsDocument3 pagesThe Commission On ElectionsArnel MangilimanNo ratings yet

- Epaper Delhi English Edition 26-10-2014Document20 pagesEpaper Delhi English Edition 26-10-2014Okay PlusNo ratings yet

- 20 02 2013 PDFDocument88 pages20 02 2013 PDFSky Gathoni0% (1)

- Supreme Student Government: Certificate of Candidacy - Enclosure 6.1 Plan of Action For SSG - Enclosure 6.2Document40 pagesSupreme Student Government: Certificate of Candidacy - Enclosure 6.1 Plan of Action For SSG - Enclosure 6.2Alyssa DwgyNo ratings yet

- John Lehmann Donates $500 To Naples City Councilman Mike McCabe - January 2020Document4 pagesJohn Lehmann Donates $500 To Naples City Councilman Mike McCabe - January 2020Omar Rodriguez OrtizNo ratings yet

- Election Law: Ultimate Source of Established AuthorityDocument92 pagesElection Law: Ultimate Source of Established AuthorityEmman FernandezNo ratings yet

- Article V: Suffrage: National Service Training Program 2 Southville International School and CollegesDocument15 pagesArticle V: Suffrage: National Service Training Program 2 Southville International School and CollegesKeaneNo ratings yet

- Apartheid - WikipediaDocument55 pagesApartheid - WikipediaMunawir Abna NasutionNo ratings yet

- 2019-2021 Lecture Notes Political ConsultatncyDocument226 pages2019-2021 Lecture Notes Political ConsultatncyM'c Fwee Freeman HlabanoNo ratings yet

- A1TL Constitution and BylawsDocument24 pagesA1TL Constitution and BylawsOscar Jr Dejarlo MatelaNo ratings yet

- PDFDocument1 pagePDFsilpaNo ratings yet

- Frivaldo vs. Comelec (174 Scra 245)Document2 pagesFrivaldo vs. Comelec (174 Scra 245)April Rose Flores Flores100% (1)

- The Legislat Ive Departm ENT: Atty. Ryan Legisniana Estevez, MPPDocument19 pagesThe Legislat Ive Departm ENT: Atty. Ryan Legisniana Estevez, MPPAj Labrague SalvadorNo ratings yet

- American Discontent The Rise of Donald Trump and Decline of The Golden Age Campbell Full ChapterDocument67 pagesAmerican Discontent The Rise of Donald Trump and Decline of The Golden Age Campbell Full Chapterwillie.kostyla455100% (8)

- Gov 2Document23 pagesGov 2faker321No ratings yet

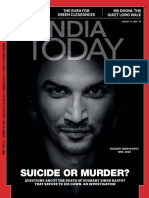

- India TodayDocument70 pagesIndia TodayJagadesan KananNo ratings yet

- Agujetas vs. Court of Appeals, 261 SCRA 17Document8 pagesAgujetas vs. Court of Appeals, 261 SCRA 17MaLizaCainap100% (1)

- Factsheet 7.2 FirstPremierDocument2 pagesFactsheet 7.2 FirstPremierKathy TaylorNo ratings yet

- Javier Vs ComelecDocument25 pagesJavier Vs ComelecVernon Craig Colasito100% (2)

- Co Vs Hret 199 Scra 692Document1 pageCo Vs Hret 199 Scra 692joven fajanilan100% (1)

- Election Bar Q 2018Document3 pagesElection Bar Q 2018Isah IlejayNo ratings yet

Mexico Gawronski, Vincent

Mexico Gawronski, Vincent

Uploaded by

Pedro J. Valencia Galeano0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

180 views36 pagesJSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content. Where does the Mexican Revolution now reside in collective memory? and does the idea of The Revolution still have any legitimating power?

Original Description:

Original Title

Mexico Gawronski, Vincent[1]

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentJSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content. Where does the Mexican Revolution now reside in collective memory? and does the idea of The Revolution still have any legitimating power?

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Download as pdf or txt

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

180 views36 pagesMexico Gawronski, Vincent

Mexico Gawronski, Vincent

Uploaded by

Pedro J. Valencia GaleanoJSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content. Where does the Mexican Revolution now reside in collective memory? and does the idea of The Revolution still have any legitimating power?

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Download as pdf or txt

You are on page 1of 36

Universidad Nacional Autnoma de Mxico

University of California Institute for Mexico and the United States

The Revolution Is Dead. "Viva la revolucin!:" The Place of the Mexican Revolution in the Era

of Globalization

Author(s): Vincent T. Gawronski

Source: Mexican Studies / Estudios Mexicanos, Vol. 18, No. 2 (Summer, 2002), pp. 363-397

Published by: University of California Press on behalf of the University of California Institute for Mexico

and the United States and the Universidad Nacional Autnoma de Mxico

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/1052161 .

Accessed: 21/02/2011 18:59

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at .

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless

you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you

may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use.

Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at .

http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=ucal. .

Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed

page of such transmission.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of

content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms

of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

University of California Press, Universidad Nacional Autnoma de Mxico, University of California Institute

for Mexico and the United States are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to

Mexican Studies / Estudios Mexicanos.

http://www.jstor.org

The Revolution is Dead.

iViva

la revoluciont:

The Place of the Mexican Revolution

in the Era of Globalization

Vincent T. Gawronski

Birmingham-Southern College

Mexicans have

long

cherished their

revolutionary heritage,

but where does the

Mexican Revolution now reside in collective

memory,

and does the idea of the

Revolution still have

any legitimating power?

And what has been the

relationship

between the PRI's

long sequence

of

legitimacy

crises and the Mexican Revolu-

tion? Until

procedural democracy provides significant

substantive and

psycho-

logical benefits,

the recent democratic turn will not

fully supplant

Mexico's tra-

ditional sources of

legitimacy.

While Mexicans

generally

see the

regime

as

falling

short in

achieving

the basic

goals

of the Mexican

Revolution,

there are indica-

tions that the Revolution-understood as collective

memory, myth, history,

and

national

identity-still

holds a

place

in

political

discourse and

rhetoric,

even if

such

understandings

make little

logical

sense in the era of

globalization.

Los mexicanos han tenido un

largo

carinio

por

su herencia

revolucionaria,

pero

id6nde

reside ahora la Revoluci6n mexicana en la memoria

colectiva?,

etodavia

tiene

poder legitimador

la idea de la Revoluci6n? eY cual ha sido el vinculo

entre la secuencia

larga

de las crisis de

legitimidad

del PRI

y

la Revoluci6n Me-

xicana? Hasta

que

la democracia

procesal proporcione ventajas

substantivas

y

psicologicas significativas,

la vuelta reciente a la democracia no

suplantara

com-

pletamente

las fuentes tradicionales de la

legitimidad

en Mexico. Mientras

que

los mexicanos

generalmente

entienden

que

el

regimen

ha fallado en la reali-

zacion de las metas basicas de la Revoluci6n

mexicana, hay

indicaciones

que

la Revoluci6n-entendida como memoria

colectiva, mito,

historia e identidad

nacional-todavia tiene

lugar

en el discurso

y

retorica

politicos,

incluso si tales

conocimientos tienen

poco

sentido

l6gico

en la

epoca

de la

globalizaci6n.

This

essay

addresses the

overarching question

of how a

political system

that

emerged

from a true social revolution

responds

to

global

forces that

seem to be

undermining revolutionary

nationalism as a source of

politi-

MexicanStudies/EstudiosMexicanos Vol. no.

18(2),

Summer

2002, pages

363-397. ISSN 07429797 ?2002

Regents

of the

University

of California. All

rights

reserved. Send

requests

for

permission

to

reprint

to:

Rights

and

Permissions, University

of California

Press,

2000 Center

St., Berkeley,

CA 94704-1223

363

Mexican

Studies/Estudios

Mexicanos

cal

legitimacy

and

regime support.

The dominant

precepts underlying

globalization-namely neoliberalism-simply negate many

of the

prin-

ciples upon

which

revolutionary-nationalist regimes

have been based.

The

specific

case is

Mexico,

where the once

highly

statist, nationalist,

and at least

rhetorically

socialist

regime

has embraced neoliberalism

and is in the throes of democratic transition. The more

general ques-

tion

necessarily provokes

several interrelated

questions

that focus

speci-

fically

on the

place

of the Mexican Revolution: Where does the Mexican

Revolution-with its

lofty goals (historically comprising

a

"religion

of

the

patria")-reside

in the Mexican collective

memory, especially

since

Vicente Fox

Quesada

of the conservative Partido Acci6n Nacional

(PAN)

has defeated the Partido Revolucionario Institucional

(PRI)?

Have the

myths

and rituals of

revolutionary

nationalism lost their

appeal?

What

has been the

relationship

between the PRI's

long sequence

of

legitimacy

crises and the Mexican Revolution? Did the PRI so

empty

the Mexican

Revolution of

significance

as to make its

mythology meaningless

and thus

incapable

of

rendering support

for both the PRI and

perhaps

even for

the entire

political system?

Does the electoral defeat of the PRI in the

era of

globalization finally signal

the Mexican Revolution's death knell?

Does the idea of the revolution continue to have

any legitimizing/

legitimating power? Finally,

and

perhaps

most

important,

can the

proce-

dural democratic

transition,

with the

high,

and often

unrealistic,

expec-

tations it has

generated, supplant

traditional

revolutionary

nationalism

as the foundation of the Mexican

political system,

thus

constituting

a

new Mexican Revolution? As

Benjamin

(2000: 13)

emphasized:

"Mexi-

cans invested a lot of

meaning

in their Revolution with a

capital

letter

during

this

century,"

but where does that

meaning

now

lay

in Mexican

collective

memory, especially

as so

many

forces-both local and

global-

are

making

it

increasingly

difficult to

uphold

so

many classically

revolu-

tionary goals

and ideals?

Drawing

from several

public opinion surveys

conducted

by

the

Mexico office of the well-known firm Market

Opinion

Research Inter-

national

(MORI

de

Mexico),

this

analysis

and discussion focuses on two

1997-1998

surveys

that included commissioned items

exploring

the Rev-

olution's

progress

and

likely

demise and the

place

of the Mexican Rev-

olution in the minds of the Mexican

people.

The first task was to assess

the

saliency

of the Mexican Revolution's basic

goals

and ideals with the

1. Public

opinion polling

has a

relatively long history

in

Mexico,

but

very

few

polls

of

any significance

have

tapped

attitudes and

opinions regarding

the relevance and/or ful-

fillment of the basics

goals

and ideals of the Mexican Revolution.

Nonetheless,

three of

the more

important survey

research-based studies are Basanez

(1990), Camp (1996),

and

Dominguez

and McCann

(1996).

364

Gawronski: Mexican Revolution in the Era

of

Globalization

365

following question,

which was asked on both

surveys:

"To what extent

are the

following

basic

principles

of the Mexican Revolution relevant to

today's

(1997-1998)

society?" Drawing

from Frank

Brandenburg's (1964)

notion of a

revolutionary

creed,

the

question

was broken down to the

most

commonly

understood

revolutionary goals

and ideals:

(1)

"The Land

Belongs

to Those Who Work

It," (2)

"Respect

for Labor

Rights," (3)

"No

Reelection of the President of the

Republic,"

(4)

"National Economic

Sovereignty,"

(5) "SocialJustice."

Asking respondents

to use a

five-point

scale

(one, "very

relevant" to

five,

"not-at-all

relevant"),

the

question

was

intended to measure the extent to which Mexicans see the

primary goals

and ideals of the Revolution as

important

to

today's

(1997-1998)

Mexico.

From

"relevance,"

the

survey

instrument moved to

"fulfillment,"

and the

survey respondents

were asked to evaluate the

degree

to which

they

saw each of the five basic

principles

as

having

been

fulfilled,

once

again

according

to a

five-point

scale

(one,

"very

fulfilled" to

five,

"not-at-all ful-

filled").

"To what extent has the

government

fulfilled the basic

princi-

ples

of the Mexican Revolution so far?"

The first MORI

survey

(n

=

1225)

was conducted in Mexico

City

in

September

1997.

The

second,

national in

scope

(n

=

1105, weighted

valid n =

1642),

was administered in late December

1997

through early

January

1998.2

The

survey

results and

analysis empirically

validate much

of the

existing

literature on

Mexico,

and two

very strong

conclusions

stand out:

1. The

goal

of "No Reelection of the President of the

Republic"

con-

tinues to be

very

relevant to

Mexicans,

and to Mexico

generally,

and is the most fulfilled basic

revolutionary principle.3

2. The

Revolution-generated goal

of

"SocialJustice"

is the least rele-

vant and least fulfilled

goal.

2. The

questions

that were

eventually

included in the December

1997-January

1998

national

survey

(n

=

1105, weighted

valid n

=

1642)

went

through

several iterations. To en-

sure that the

questions

were

understandable,

a self-administered

pre-test

was conducted

among

Mexican nationals

living

in the

Phoenix, Arizona,

area. In

September 1997,

MORI

de Mexico conducted a

pilot study (n=1225)

in Mexico

City

to ensure that the

questions

were

manageable

in the field. The

pilot study produced

valuable

quantitative

and

qualita-

tive data and can be considered a stand-alone

study

of Mexico

City.

After some minor ad-

justments

and

rewordings,

MORI

appended

the final

survey

instrument to the 1997 Mexico

Latinobar6metro,

which is a

comprehensive public opinion survey

modeled after the Eu-

robarometer and

implemented annually

in seventeen Latin American countries and

Spain.

3. While the

principle

of no reelection also

applies

to other elected

officials,

it is most

strongly

associated with the

presidency

because of the

highly presidentialist

nature of the

postrevolutionary regime

and the existence of the

six-year "perfect dictatorships"-the

sex-

enios.

Moreover,

it was also much easier to

tap opinions regarding

the

presidency

because

it is has been such a visible and

palpable

historical

component

of Mexico's

political system.

Mexican Studies/Estudios Mexicanos

The Revolution as a Source of

Legitimacy

Exploring public

attitudes toward the Revolution is

admittedly

sensitive.

Whether

institutionalized,

permanent,

frozen,

or

programmatically

dead,

the Revolution has carried enormous

symbolic

value and has

generated

a massive literature.4

Historically

it has been a national

adhesive,

at least

rhetorically, despite

never

being uniformly

understood.

Now, however,

the Mexican

political system,

which was founded on

revolutionary

rhet-

oric and socialist ideals

(some

initially competing),

is

facing unique

chal-

lenges. Indeed,

contrary

to its

founding revolutionary ideology,

Mexico

is

increasingly becoming

a

cog (or

"pivot")

in the

global system (espe-

cially

with its

unique global

trade

relations),

and the official revolution-

ary party-the

PRI-is no

longer revolutionary

or even

populist.

As

Thomas

Benjamin

(2000: 23)

astutely

observed:

The Mexican

political system during

most of the twentieth

century

has based

its

legitimacy largely

on la Revoluci6n. The state and the dominant

party,

ac-

cordingly,

are the culmination and continuation of the Mexican revolution. La

Revoluci6n is identified with the most sacred values and the

highest principles

of the

Republic,

as well as the

greatest

needs and

aspirations

of its

people.

The

revolutionary origins

of the

political system

and the

system's

faithful adherence

to la Revolucion have

justified

the existence of the

system,

the

hegemony

of

the official

party,

and the

authority

of the successive

regimes

that take

power

every

six

years.

This

pattern

for

support

is

changing,

however. The

system

has

deviated from its

founding principles

as Mexican civil

society

has

changed

and

awakened.

Opponents

of the

government

have embraced la Revolucion and are

making

it their own.

Addressing legitimacy

in

Mexico, however,

is

always fraught

with

prob-

lems because Mexicans

supported

the PRI-state

system

for decades de-

4. Within the vast "Mexicanist" mainstream

literature,

a

strong

current has

empha-

sized the Mexican Revolution and its

meaning

and

importance.

Still one of the most in-

sightful

works is The

Making of

Modern Mexico

(1964),

where

Brandenburg

more con-

cretely developed

the idea of the

"Revolutionary Family"

and the

closely

associated

"Revolutionary

Creed." Ross's Is the Mexican Revolution Dead?

(1966)

and Cumberland's

The

Meaning of

the Mexican Revolution

(1967)

continued the focus. The Revolution was

then revisited in the mid-1980s with the

Cambridge History of

Latin America series

(1984),

Knight's (1986)

erudite two-volume

history,

and Hart's

(1987)

influential work.

Later,

in

their edited

volume,

Everyday

Forms

of

State

Formation, Joseph

and

Nugent (1994)

in-

sightfully

demonstrated the

continuing

role of the Mexican Revolution in the

relationship

between

popular

cultures and state formation at the local level

(see

also Becker

1995).

At

the same

time, however,

other scholars

began shifting

the theme to the Revolution's

pos-

sible

demise, specifically Meyer (1992), Aguilar

Camin and

Meyer

(1993),

and Middlebrook

(1995). Benjamin (2000),

from a more historical

perspective,

examined how Mexicans in-

terpreted

the Revolution

through

collective

memory, myths,

and

historiography

between

1910 and 1950.

366

Gawronski: Mexican Revolution in the Era

of

Globalization 367

spite injustices, gross inequalities,

and classic semi-authoritarianism.5

Indeed one of the most

enigmatic

features of Mexican

society

is the de-

gree

to which Mexicans have

historically

tolerated so much.

Support,

in such

cases,

for the

system

does not emanate as much from "belief in

the

validity

of

legal

statute" or rational

rules, resting

more on

ideolog-

ical foundations and culture than on modern

sources,

despite

Mexico's

remarkable and

thoroughly

modern constitution. But as

globalization

bears down

heavily

on

Mexico,

the traditional

ideological

and cultural

sources of

legitimacy

are

withering just

as

democracy

seems to be tak-

ing

hold-that

is,

as democratic

procedures (free

and fair

elections)

and

high expectations

of benefits

(substantive

and

psychological) replace

revolutionary

nationalism. Thus the traditional

symbolic,

national ad-

hesive that has held the

postrevolutionary regime together

for so

long

is now

dissolving. However,

the

apparent

democratic transition will

mean

very

little if the

average

Mexican's

quality

of life does not soon

improve.

If the

regime

does not meet a sufficient measure of social ex-

pectations,

democratic breakdown and civil unrest

may

result. As

well,

if

society

continues to hold socialist and

revolutionary-nationalist

ideals

or if it maintains

unrealistically high expectations,

the

regime

could be

forced to deal with

greater

levels of

opposition

and/or political

violence.

Regime performance

and effectiveness become more salient when

crises

emerge

or when social

(value)

expectations

outrun

regime (value)

capabilities.6

5.

Padgett's (1976, 1966)

work laid out the fundamental characteristics

(semi-

authoritarianism, co-optation, corporatism)

of what Needler

(1995)

described as the "clas-

sic" Mexican

political system.

6. Mexico is indeed in

flux,

but

potentially

the

gravest problem

resides in the im-

plications

of a

stuck,

or at least a

severely constrained,

policy pendulum.

In his famous "J

curve"

theory

of

revolution,

Davies

(1962) posited

that when an intolerable

gap emerges

between

expected

values and actual

values,

conditions become

ripe

for revolution. The

contemporary

Mexico

case, however,

is not a

perfect

fit for Davies. Punctuated with so

many crises,

Mexico has not

yet experienced

"a

long period

of

rising expectations

and

gratifications."

In

fact,

Mexico's most successful

period

of economic

growth-the

so-called

Mexican Miracle-exacerbated

many inequalities. Indeed, only recently

have the mod-

ernization of Mexican

society

and the

apparent

democratic transition

significantly

raised

hopes

and

expectations-unfortunately just

as Mexican

policymakers

are

becoming

more

constrained.

Therefore,

Mexico's

predicament

more

closely

fits Gurr's

(1967)

model than

Davies's

or,

for that

matter, Johnson's (1966).

Gurr

(1967: 3) argued

that:

[T]he necessary precondition

for violent civil conflict is relative

deprivation,

defined

as actors'

perceptions

of

discrepancy

between their value

expectations

and their en-

vironment's value

capabilities.

Value

expectations

are the

goods

and conditions of life

to which

people

believe

they

are

justifiably

entitled. The referents of value

capabili-

ties are to be found

largely

in the social and

physical

environment:

they

are conditions

that determine

people's

chances for

getting

or

keeping

the values

they legitimately

ex-

pect

to attain.

Mexican

Studies/Estudios

Mexicanos

Undeniably,

the institutionalization of the Mexican Revolution and the

creation of a

revolutionary iconography

with its associated

myths

were

unique

historical,

political,

and cultural

processes.

And a

specific pro-

grammatic

agenda emerged

to advance basic

revolutionary principles

and

ideals,

but this created a tension between the real and the ideal. The PRI

laid official claim to its

revolutionary heritage,

in

essence, by upholding

a

nationalist-revolutionary myth

(or

myths), advancing

socialist

rhetoric,

and

implementing

certain ideals and

goals

but

freezing

others for later.

The revolutionaries-the

"Revolutionary Family"-blessed

the PRI as the

official

party

of the

Revolution,

as Martin Needler

(1995:

68-69) noted:

In Mexico

legitimacy

has two

sources,

democratic and

revolutionary, reflecting

the fundamental

ambiguity

of Mexican

political mythology. Legitimacy

comes

from election

by

the

people;

it also comes from the

heritage

of the Revolution.

When

legitimacy

no

longer

comes from

"above,"

from

royalty ruling by

the

grace

of

God,

it must come from

"below,"

from the will of the

people,

or from the act

of the overthrow of the

illegitimate

ruler itself. Until the

system began

the ex-

tended crisis

period

of the 1980s and

'90s,

these two sources of

legitimacy

con-

verged

in the official

party,

the PRI.

The PRI-state

system

also relied

upon populism

and

specific

socialist

poli-

cies such as land

redistribution,

albeit

limited,

and economic national-

ism

(Import

Substitution

Industrialization)

to foster a sense of Mexican-

ness

(mexicanidad),

which

garnered support

for the

regime.

Indeed

support

for the

postrevolutionary regime

became

tightly

bundled with

Mexican nationalism and a sense of

identity, especially

cultural nation-

alism.

Also, creating

a sense of who is and who is not Mexican bound the

nation and the

postrevolutionary

state

(see Knight 1994).

Thus,

the vast literature on

political legitimacy

in Mexico has tended

to focus on how certain

institutions,

practices,

social

forms,

myths,

and

heroes became

accepted

as

legitimate.

It has

generally emphasized

the

historical

process whereby

the national state came to exercise control

and domination after the Mexican

Revolution,

especially

how the state

"institutionalized" the Revolution.7 Vincent L.

Padgett's (1976: 59-60)

work is still

revelatory:

The

nationalist, revolutionary

tradition

composed

of ideals and heroes reaches

back

through

time. The roots lie in the

periods

of Cardenas and

Zapata,

and fur-

7.

Importantly,

Mexican attitudes toward education are

very significant

for

political

legitimacy

and

regime support.

Education is an

agent

of

political

socialization,

and in

Mexico,

the

public

schools are

operated by

the national

government.

Needler

(1995: 69)

noted that

"public

education in Mexico has a

high

content of civic indoctrination." This

factor,

as

Camp

also observed

(1993: 57),

"could serve as a

positive,

indirect means of re-

inforcing

the state's

legitimacy-especially

because texts in

elementary

schools are selected

by

the

government." Therefore,

education is

important

for

passing

on the basic

principles

368

Gawronski: Mexican Revolution in the Era

of

Globalization

369

ther,

in those of

Juarez, Hidalgo,

and

Morelos,

and even

stretching

back to

Cuauhtemoc and the

days

of Indian

greatness.

All of this has been

shaped

into

an historical

synthesis

which focuses on the

identity

of the

people

and forms

the basis of the

existing

national order. "Mexicanism"

(Mexicanidad)

is used to

justify

the

present

and the future. The

Revolutionary

coalition has found it a valu-

able means of

subordinating

the

deep

schisms in Mexican

society

to the

imple-

mentation of

policy

and the

stability

of

government.

This institutionalization

process,

Alan

Knight (1994: 60)

later

added,

while

undeniably

a state

project

of cultural

transformation,

was

complex

and

contradictory:

The

revolutionaries,

as I have

said, firmly

believed in notions of

hegemony,

even

false consciousness

(if

not in those

terms).

But how successful were

they? First,

did

they

transform

popular consciousness, legitimizing

the

revolutionary regime?

(And

if

so,

we

may

ask

again,

did

thereby

foster a new

"mystification"

or "false

consciousness"?

Or, rather,

did

they successfully

combat a rival

legitimation-

for

example,

Catholic conservatism-and

thereby demystify, breaking

the fetters

of false

consciousness?)

Or was the

revolutionary project

a

failure,

a

gimcrack

facade behind which the common

people,

the

peasants especially, grumbled

and

prayed

to old

gods,

untouched

by

the new

legitimation?

Was it a case not

just

of "idols behind altars" but idols behind altars behind murals?

Needler

(1995: 69), moreover, highlighted

the role of the

president

of

Mexico:

The

popular

mandate and democratic

legitimacy

were of course

personalized

in the role of the

president. By

a sort of

pseudo-apostolic

succession,

the

pres-

ident was also the direct heir of the

martyrs

of the

Revolution, having

received

the

presidential

sash from the hands of his

predecessor,

who had received

his from

his,

in a line which

goes

back at least to

Obreg6n.

The

party

and the

president

thus incarnated

legitimacy

in Mexico.

Benjamin

(2000:13), focusing

on the

early postrevolutionary period,

em-

phasized

the role the voceros de la Revolucion had on

legitimating

the

regime.

The voceros were those "that had invented and constructed the

Revolution with a

capital

letter in their

pamphlets, broadsides, procla-

mations, histories, articles,

and editiorials." He

(2000: 14)

explained:

Their

talking, singing, drawing, painting,

and

writing

invented la Revoluci6n: a

name transformed into what

appeared

to be a natural and self-evident

part

of

reality

and

history.

This

talking

and

writing

was also

part

of an

older, larger,

and

greater project

offorjando

patria, forging

a

nation, inventing

a

country, imag-

ining

a

community

across time and

space

called Mexico.

and ideals of the Mexican

Revolution,

which

Padgett

(1976: 9) pointed

out

early

on: "Par-

ticularly important

is the

interpretation

of

history

as

presented

to most Mexican school

children and

young people."

Mexican

Studies/Estudios Mexicanos

The

Revolution,

consequently,

became embedded in Mexican collec-

tive

memory

as national

myth

and

history. Virtually every

Mexicanist

therefore

agrees

that Mexico's

postrevolutionary political system

has,

at least

metaphorically,

rested on a socialist-nationalist and revolution-

ary ideology,

but Mexico's

biggest paradox

has been the dissonance be-

tween

revolutionary

rhetoric and the

reality

of the Mexican

state,

which

became

readily apparent

when Mexico's

post-World

War II

period

of

economic

growth-the

"Mexican Miracle"-started to

peter

out,

and

most

starkly

in

1968,

with the massacre at Tlatelolco.8

Starting

in

1968

and more or less

ending

with the

highly

contested

1988

presidential

elections Mexico

experienced

a

long sequence

of

legitimacy

crises. The

definitive end of the

sequence

of

legitimacy

crises came with the

pop-

ular election of Mexico

City's

first true

mayor,

Cuauhtemoc

Cardenas,

in

1997,

and of

course,

with the electoral defeat of the PRI in 2000

by

Vicente Fox.

The PRI's

Sequence

of

Legitimacy

Crises:

Moral, Performance-Based,

and Political

Many

less astute observers of Mexico have tended to

explain

the PRI's

loss of

support by focusing

on

perceptions regarding

the PRI's

(in)at-

tentiveness to social

expectations during

the 1980s

and

1990s; however,

the

beginning

of the end for the PRI must be

pushed

back to

1968,

a

point

made

by

Will Pansters

(1999: 250)

and

many

others:

Although

the

agitated

summer of 1968 ended in brutal

repression,

its

longer-

term effects are

argued

to be so

profound

that there exists a line of

continuity

between this

experience

(1968)

and the electoral

opening

which, sinceJuly 1988,

8. The Tlatelolco

rally

was not

large compared

to the

protests

and demonstrations

that would be

organized

in the 1980s and 1990s in Mexico

City's

z6calo. On October

2,

1968, just days

before Mexico would host the

Olympics,

thousands of

students, women,

children,

and

spectators gathered

in the Plaza. The demonstration was

peaceful.

The

speeches

were emotional but not

noteworthy. Riding (1985: 60)

summarized what

hap-

pened

next:

At around 5:30 P.M. there were

10,000 people

in the

plaza, many

of them women and

children

sitting

on the

ground.

Two

helicopters

circled

above,

but the crowd was ac-

customed to such surveillance. Even the

speeches

sounded familiar. Then

suddenly

one

helicopter

flew low over the crowd and

dropped

a flare.

Immediately,

hundreds

of soldiers hidden

among

the Aztec ruins of the

square opened

fire with automatic

weapons,

while hundreds of secret

police agents

drew

pistols

and

began making

ar-

rests. For

thirty minutes,

there was total confusion. Students who fled into the

adja-

cent Church of San Francisco were chased and beaten and some were murdered. Jour-

nalists were allowed to

escape,

but then banned from

re-entering

the area when the

shooting stopped.

That

night, army

vehicles carried

away

the

bodies,

while firetrucks

washed

away

the blood.

370

Gawronski: Mexican Revolution in the Era

of

Globalization 371

seeks to

put

an end to the

hegemony

of the official

party.

These effects

range

from the modification of values and behavioural

practices, through

a

reorgani-

zation of class alliances within the

ruling

elite

(favouring

the urban middle classes

to the detriment of traditional

corporatist

sectors),

to the

emergence

of

public

opinion

as a

political

factor. Others have

emphasized

that it was the violent

sup-

pression

of the 1968 student movement and the

spreading

of

leadership

and

ideologies throughout society.

With the massacre of students and other

protesters

in the Plaza de

Tlatelolco-several hundred

people

were killed but the

government only

conceded

32-the PRI-state

system

was

widely challenged,

for the first

time,

on a value basis. The

1968

Olympic

Games were held without ma-

jor

incident,

and Mexico's

image

abroad was saved. Less

immediately

vis-

ible but more

important

in the

long term,

the moral

legitimacy

of the

entire PRI-state

system

was undermined. In

particular

the

regime

lost the

support

of

many

of Mexico's established and

upcoming intelligentsia.

Many

of Mexico's intellectuals had shared with the

political system

an

ideological agenda

of

revolutionary

nationalism and the

widespread pro-

motion of education. Entwined in mutual

support,

the

intelligentsia

lent

legitimacy

to the

regime.

In return the

regime

doled out favors and

gov-

ernment

posts

to their favorite sons (and a few

daughters). However,

shocked

by

the PRI-state's behavior at

Tlatelolco,

such world-renowned

writers as Carlos Fuentes and Octavio Paz

strongly

denounced the bru-

tal actions of the

regime, breaking

their official ties with the

government

and

calling

into

question, really

for the first

time,

the

legitimacy

of the

whole

postrevolutionary system.

Enrique

Krauze

(1997: 733)

noted the historical

impact

of 1968 on

Mexican

politics

and

society

while

focusing

on the motivations and con-

sequences

of

people's

actions:

The Student Movement of

1968

opened

a crack in the Mexican

political system

where it was least

expected: among

its

greatest beneficiaries,

the sons of the

middle class. On their own account

they

rediscovered that "man does not live

by

bread alone." Their

protest

was not in behalf of

revolution,

it was for the

broader cause of

political

freedom. As had been the case with the

doctors,

the

government

did not know how to handle middle-class dissidence

except through

the same violent methods

(loaded threats or loaded

guns)

that had

given

them

effective results with the workers and the

peasants. Here,

their action had the

opposite

effect.

But

despite

the revealed contrast between the

regime's professed

rev-

olutionary

values and its

actions,

it survived

through co-optation,

clas-

sic

semi-authoritarianism,

and moderate

political

reforms. The

1977-

1978

reforms softened direct

challenges

to the

system by making

it eas-

ier for

opposition parties

to

officially register

and

by widening,

ever so

Mexican

Studies/Estudios

Mexicanos

slightly,

the arena for

political

mobilization and interest

representation.

"The

political

reform was the

government's

and the

ruling party's

re-

sponse

to a series of

challenges

that undermined the

efficiency

and le-

gitimacy

of the PRI"

(Pansters 1999: 250). Indeed,

PRI

political

reform

efforts have been more a result of PRI-elite survival

strategies

than ad-

herence to some

deep-seated

commitment to

democracy

and revolu-

tionary goals

and ideals. PRI elites

implemented liberalizing political

re-

forms in

response

to

perceived

threats,

not because

they

were

being

responsive

and attentive to the needs and wishes of the Mexican

people.

Todd A. Eisenstadt (2000:

5-6) argued

that the PRI liberalized the

electoral

system

for four reasons:

First,

the PRI

could, "through multiple

iterations of

graduated reforms,

acquire precise

information about in-

cumbent and

opposition popularity

in various

segments

of the

popula-

tion."

Second,

the PRI could "divide and

conquer

the

opposition through

such reforms."

Third,

the

channeling

of

opposition

into the electoral

arena

helped

the PRI to channel

protesters,

students,

and the

strongly

disillusioned "out of the

unpredictable

realm of street demonstrations

and

picket

lines and into the

highly regulated

realm of

campaigns

and

elections." This

channeling

"also

helped

to restore

credibility

to the

[PRI]

domestically

and

internationally." Finally, political

liberalization

helped

to "bind the hardliners within the authoritarian coalition." Eisenstadt

(2000: 6)

explained:

[T]he

party's

technocratic

leaders,

especially

in the

1990s, increasingly

dis-

counted the old-time machine's

ability

to

"get

out the vote" as a skill valued

by

the

party.

In

fact,

President Carlos Salinas

repeatedly

undermined the traditional

machine bosses

by negotiating away

their electoral victories at

post-electoral

bar-

gaining

tables with the

PAN,

known as concertasiones

(Spanish slang

combi-

nation of "concession" and

"agreement").

Salinas drove a

wedge

into the

party

starting

in

1989 which ended in electoral defeat 11

years

later

by placing

a much

higher premium

on

getting along

with the PAN in federal

parliamentary

cham-

bers on economic

policy

votes than on

getting along

with his own

party's

tra-

ditional vote

getting

activists. He has been

widely

blamed for

weakening

the PRI

to the

point

that PRIistas have

proposed

his

expulsion

from the

party.

Ernesto

Zedillo,

Salinas's less

politically

adroit and

equally

technocratic successor con-

tinued Salinas's

policy

(but without

going

to Salinas's extreme of

sacrificing

lo-

cal PRI victories for concession

agreements

with the

PAN), divorcing

himself

from

party

affairs in the controversial "safe distance"

policy.

While it is true that the PRI liberalized itself into electoral

defeat,

the

story

needs more contextualization and

explanation

because the dem-

ocratic transition has been so

protracted.

Moreover,

while Mexico has

made

significant

democratic strides with the PRI's

losses, very

few

politi-

cians and even fewer academics are

declaring

the transition

complete.

372

Gawronski: Mexican Revolution in the Era of Globalization

373

Essentially,

the PRI's

implosion

and

apparent

demise must be traced to

the PRI-state

system's long sequence

of

legitimacy

crises,

political

re-

form efforts to deal with several

problems,

and a

general falling

out of

touch with the Mexican

people

as

society modernized,

all of which re-

sulted in the

withering away

of the PRI's traditional

revolutionary

sources of

legitimacy

and

corporatist

and

populist

networks.

In

1982

Mexico announced that it could no

longer

service its ex-

ternal

debt,

banks were

nationalized,

and an economic debacle

ensued,

which initiated Latin America's "Lost Decade" of

development. Chap-

pel

Lawson

(2000: 272)

noted that

"[b]y

the

early

1980s,

fifty years

of

corruption, cronyism, patronage,

and

pork barreling

had

sabotaged

Mexico's

economy."

Then,

in

1985,

Mexico

City

was struck

by

twin earth-

quakes

that devastated

parts

of the

city.

The PRI-state

system's

disaster

response

and

subsequent management

of the reconstruction were

widely

criticized. The

regime's performance legitimacy

was

lost,

as

people

realized

just

how few resources the PRI-state

system really

com-

manded,

how

corrupt

it

was,

and how much

political space actually

ex-

isted. The confluence of these factors made the PRI

politically

vulnera-

ble in the

highly

tainted 1988

presidential

elections,

in which the PRI

resorted to electoral

alchemy

to

prevent

a Partido de la Revoluci6n

Democratica

(PRD)

victory.

In

1988, then,

the PRI lost

political legiti-

macy.9

Lawson

(2000: 272)

emphasized

the

importance

of 1988:

Although

the

regime's legitimacy

had been

eroding steadily,

it now

collapsed.

Like other

catalytic

events-such as the Tlatelolco massacre of

1968,

the national

bankruptcy

of 1982 and the

devastating

Mexico

City earthquake

of 1985-the

alleged

fraud of

1988

triggered

mass

protests

and

increasing

social mobilization.

Since

1988, Knight (1999: 106-107) argued

the PRI has fallen into an-

other "Darwinian

period," having gone through

three

(and now

four)

stages

in its evolution:

[F]irst

a Darwinian

period (1917-29)

of internal

conflict, punctuated by

revolts

from within the ranks of the

revolutionary army, during which,

with the recur-

rent victories of the central

government,

the ranks of the dissidents were thinned

and the

penalties

of

insurgency

rammed home.

Second,

a

long

transitional

pe-

riod

(1929-52)

when revolts were few or feeble and

PNR/PRM/PRI dissidents

mounted

significant

but unsuccessful electoral

challenges

to the official candi-

date.

Third,

the

heyday

of the PRI

(1952-87),

when the

party machine,

possessed

of enormous

powers

of

patronage,

maintained

party cohesion,

avoided schisms

and defeated the

genuine opposition parties

with relative ease. The PRI

split

of

9. A useful heuristic device for

clarifying

the PRI-state

system's sequence

of

legiti-

macy

crises is Collier and Collier's

(1991)

"critical

juncture"

framework.

Application

of

the framework reveals that the turn to

political

liberalization is a direct

legacy

of the

1968-1988

period

of

change

and transformation for the entire

country.

Mexican Studies/Estudios Mexicanos

1987,

followed

by

the

highly

contentious 1988

election,

represented,

in some

ways,

a return to the second

phase, although

in

very

different socio-economic

circumstances.

Nevertheless,

by

the

1991 mid-erm

elections,

it

appeared

that

everything

had returned to normal. The PRI

regained

its

strength, primarily

because

the PRD leftist coalition could not muster the same measure of

support

that it had in

1988.

However,

despite

the

apparent

return to

normality,

political

liberalization continued

apace

with further electoral reforms.

In

1989

the Federal Electoral

Institute,

Instituto Federal Electoral

(IFE)

was created and then reconstituted in

1990

to release it further from the

fetters of

government

control and to

empower

it to oversee and moni-

tor the

voting process.

A

1993

electoral reform law

helped

to make the

electoral

process

even fairer and more

transparent by giving

the IFE more

power

and

autonomy.

Eisenstadt

(2000: 11)

called the IFE

"[t]he

most

critical autonomous institution for

mediating

the 'levelness' of the elec-

toral

playing

field."

In

large part

due to the

IFE,

the

1994

presidential

election

appeared

both fair and

clean,

despite being preceded by

a host of traumatic

events,

especially

the

Zapatista uprising

in

Chiapas

and then the assassinations

of 1994 PRI

presidential

candidate Luis Donaldo Colosio and then Mario

Ruiz

Massieu,

the PRI

party

chairman.

President Ernesto Zedillo who had

replaced

Colosio as the PRI's can-

didate,

was in office less than a month before Mexico tumbled into

yet

another economic

crisis,

as a

consequence

of a

poorly managed peso

devaluation. Millions of

jobs

were lost as the middle class once

again

bore

the brunt of Mexico's

wrongheaded

economic

management,

and doubts

were raised about Mexico's future

stability, especially

as incidences of

high-level narco-corruption

came to

light.

But

political

liberalization and

democratic

aspirations tempered

direct attacks on the

regime-the

var-

ious

guerrilla

insurrections in the South were an

exception-and

miti-

gated

a

potentially

volatile situation.

The

1997

mid-term elections continued the

liberalizing

trend. One

important

result was the election of Mexico

City's

first true

mayor,

the

PRD's Cuauhtemoc

Cirdenas,

rather than an

appointed regent.

This

gave

the PRD

greater political recognition

and

prestige.

The second result was

an

opposition majority

in the Chamber of

Deputies

(Mexico's

lower

house), again

for the first time. But the most historic

development

has

been the most recent.

The

July

2000

presidential

elections resulted in the PRI's first defeat

ever,

when Vicente Fox

Quesada

of the

center-right,

conservative Par-

tido Acci6n Nacional

(PAN),

but in coalition with the Partido Verde

Ecologista (PVE),

won the election.

Significantly,

Zedillo

publicly

rec-

374

Gawronski: Mexican Revolution in the Era

of

Globalization

375

ognized

Fox as his

successor, hailing

Mexico as a true

democracy.

0

And

in

Chiapas,

where the

Zapatista problem

has been

festering

since

1994

and where the PRI has

traditionally

and

authoritatively

dominated

poli-

tics,

the PRI was defeated in the

August

2000

gubernatorial

race

by

a

former

priista,

Pablo Salazar

Mendiguchia.

To defeat the

PRI,

Salazar was

supported by

a broad coalition of

eight opposition parties.

Apparently,

the Mexican

people

had had

enough, publicly

declar-

ing

that

they

would vote PRI but then

secretly voting

for the

opposition.

Judith

Adler Hellman

(2000: 6)

emphasized

that it was "the sum of mil-

lions of individual decisions to vote

strategically

and

non-ideologically"

that made the difference. Democratic

procedures

do

matter,

and the Mex-

ican

people

voted for

change.

Indeed

they

now feel safer

voting

for the

opposition,

and for the first

time,

it is

possible

to

contemplate seriously

the consolidation of

democracy

in Mexico. 1

Through

this

sequence

of

legitimacy crises,

the PRI-state

system

gradually

moved further

away

from its

revolutionary heritage,

but the

Revolution still resided

firmly

in the collective

memory

of the Mexican

people.

In

fact, through

the

sequence

of

legitimacy

crises,

PRI elites were

10.

Zedillo,

whose sexenio was not

especially remarkable,

nonetheless found him-

self in an

interesting

situation. Hellman (2000: 9) explained:

At

worst, history

will note its financial

scandals,

not to mention its failure to resolve

the crisis in

Chiapas, improve

the

poor

human

rights

record of

Mexico,

or make a dent

in the

growing power

of the

drug

lords. Yet the

outgoing president

found himself in

a

win/win

situation. Either the PRI would

prevail,

in which case Zedillo could claim

that the

good government

and

leadership

he

provided paved

the

way

for

victory. Or,

as

transpired,

Labastida would lose to

Fox,

and Zedillo could

play

a historic role in the

great transition, calling

for

respect

for the democratic

process,

the will of the

people

and the rule of law.

11.

However,

there remain

significant challenges

to democratic consolidation. A

wealthy

and

powerful

economic class continues to

reap

the benefits from

neoliberal,

free-

trade

policies,

and economic benefits have not been

trickling down, despite

Mexico's cur-

rent macroeconomic

stability

and

growth

rate. No one "eats the

GDP,"

and

approximately

half of all Mexicans live at or below the

poverty line,

with the income of the

poor

lower

in real terms that it was before the 1994 crisis. General crime is

rampant

in some

areas,

especially

in Mexico

City

and

along

several

lesser-traveled,

rural

roads,

and human

rights

abuses are not

infrequent. Arbitrary

detention, torture,

and assassinations with

impunity

continue,

and the

judicial system

is too weak (and often too

corrupt)

to

investigate

and

prosecute.

The

illegal drug

trade feeds billions into the

political economy,

which con-

tributes

heavily

to

corruption. Also,

environmental

degradation

and

pollution

on a

grand

scale are

prevalent, especially

in Mexico

City

and

along

the U.S.-Mexican border. Chronic

low-intensity military

conflict continues in a number of

states,

and

finally,

"democratiza-

tion has not

proceeded

at the same

pace

across all

regions

or

spheres

of

government.

As

a

result,

Mexico's new

political

order

comprises

a series of authoritarian enclaves in which

the old rules of the

game

still

operate"

(Lawson

2000:

267-268).

Mexican

Studies/Estudios

Mexicanos

assailed for

betraying

the

principles

of the Mexican Revolution. This be-

trayal

would become more

evident,

and even

necessary,

as Mexico be-

came more

deeply integrated

into the

global economy

and more vul-

nerable to its vicissitudes and as the

government's policy pendulum

stuck

to the

center-right,

with

policymakers

forced to abandon

outright

the

revolutionary programmatic agenda.12

As Needler

(1995: 30)

pointed

out:

Under other

circumstances,

the

change

in economic

policy

would have been

an

extremely risky policy

for

Salinas, putting

in doubt his

legitimacy

as heir

of the

Revolutionary

tradition at the same time as his other source of