Professional Documents

Culture Documents

We Like To Believe That Physical Phenomena

We Like To Believe That Physical Phenomena

Uploaded by

Andu BocaCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5820)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1093)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (845)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (898)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (540)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (349)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (822)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (401)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Seismic Methods Advantages and DisadvantagesDocument1 pageSeismic Methods Advantages and DisadvantagesDedipyaNo ratings yet

- The Story of The StarsDocument206 pagesThe Story of The Starssajeewa99No ratings yet

- Astrological Combination of JobDocument11 pagesAstrological Combination of JobjebabalanNo ratings yet

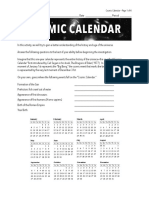

- Cosmic Calendar ActivityDocument4 pagesCosmic Calendar ActivityMatt DiDonatoNo ratings yet

- Exercise Acidizing VSPDocument11 pagesExercise Acidizing VSPQuy Tran XuanNo ratings yet

- Pamphlet 02 - Evolution in A Nutshell PDFDocument2 pagesPamphlet 02 - Evolution in A Nutshell PDFgordomanotasNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1 (Lesson 2, Part 3) - Famous Filipinos in The Field of ScienceDocument22 pagesChapter 1 (Lesson 2, Part 3) - Famous Filipinos in The Field of ScienceJorel DiocolanoNo ratings yet

- (Komonov EtAL) Geochem Methods of ProspectingDocument412 pages(Komonov EtAL) Geochem Methods of Prospectingjavicol70No ratings yet

- Dhanjori Formation Singhbhum Shear Zone Unranium IndiaDocument16 pagesDhanjori Formation Singhbhum Shear Zone Unranium IndiaS.Alec KnowleNo ratings yet

- Daftar PustakaDocument2 pagesDaftar PustakaAbdul Aziz SlametNo ratings yet

- IELTS Exam Preparation - IELTS Academic 10 - Reading Passage 1Document2 pagesIELTS Exam Preparation - IELTS Academic 10 - Reading Passage 1Ioana Aurora Paslaru0% (1)

- Parks and Open SpacesDocument9 pagesParks and Open SpacesLyjie BernabeNo ratings yet

- G.5 1st Term Form BDocument5 pagesG.5 1st Term Form BSally ElEssawyNo ratings yet

- Wind LoadingDocument18 pagesWind LoadingStephen Ogalo100% (1)

- Mineralogy 1Document50 pagesMineralogy 1Karla Fermil SayenNo ratings yet

- 5 Basement Cu Belt Zambia PDFDocument51 pages5 Basement Cu Belt Zambia PDFAlberto Lobo-Guerrero SanzNo ratings yet

- Site Location: Rio de JanerioDocument11 pagesSite Location: Rio de JanerioAbdul SakurNo ratings yet

- Stefan-Boltzmann Law: 2 H C Exp 1Document16 pagesStefan-Boltzmann Law: 2 H C Exp 1RonyVargasNo ratings yet

- Debajit Borah: Professional QualificationDocument3 pagesDebajit Borah: Professional Qualificationdborah89No ratings yet

- Trucos de Pokemon EsmeraldaDocument50 pagesTrucos de Pokemon EsmeraldaWil Arias CNo ratings yet

- KP AstrologyDocument42 pagesKP Astrologyvydeo60% (5)

- Lab Rep 11Document15 pagesLab Rep 11Reign RosadaNo ratings yet

- Plant Life Cycle Passage For Plant LessonDocument2 pagesPlant Life Cycle Passage For Plant Lessonapi-241278585No ratings yet

- Geology NotesDocument2 pagesGeology NotesPriyankaNo ratings yet

- 03 Life TablesDocument7 pages03 Life TablesMonalisa Jeriska0% (1)

- Pdac 2017 Convention ProgramDocument104 pagesPdac 2017 Convention ProgramCecil Eduardo Angulo MarquezNo ratings yet

- Prasna NotesDocument24 pagesPrasna NotesRajeswara Rao NidasanametlaNo ratings yet

- A Guide To Understanding Land Surveys (Third Edition)Document254 pagesA Guide To Understanding Land Surveys (Third Edition)barupatty83% (6)

- Carl Linnaeus (Print)Document3 pagesCarl Linnaeus (Print)Liwen LiewNo ratings yet

- Principais Depositos Minerais DNPM CPRMDocument14 pagesPrincipais Depositos Minerais DNPM CPRMluizhmo100% (1)

We Like To Believe That Physical Phenomena

We Like To Believe That Physical Phenomena

Uploaded by

Andu BocaOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

We Like To Believe That Physical Phenomena

We Like To Believe That Physical Phenomena

Uploaded by

Andu BocaCopyright:

Available Formats

We like to believe that physical phenomena, animals, people and

societies obey predictable rules, but such rules, even when carefully

ascertained, have their limits. Every rule has its exceptions.

ASSIGNMENT: What is one particular exception to a rule?

When their cerebral cortex began to develop from that of an ordinary

animal, humans were endowed with consciousness and self-awareness.

Ever since its nervous system evolved, as far back as 1.44 million years

ago, the human species has shown a solid desire to categorize, catalogue

and ultimately understand with the aid of a specific set of rules. Recent

findings have brought to surface old fossils used by a Homo habilis

female to documentate her menstrual cycle. Even old cave paintings

indicate our insistence on order, therefore it cannot be surprising that

anything forgoing an universally accepted rule would baffle us.

The wisest of us tend to agree to the fact that societal and ideological

rules are generally flawed. Although most developed civilizations have

lived under a strict religious system, the set of moral laws that expresses

implacable truths gravitates towards exceptions itself. The Ten

Commandments, a long disputed example for this idea, strongly opposes

murder in any circumstances through the categoric phrase Thou shalt

not kill. On the other hand, philosophers have dabbled upon the validity

of this rule in critical situations, such as that when a person remains in a

coma for a relatively irrecoverable period of time. Or if we were to take

into consideration the immense pain a pet endures at the end of its life,

euthanasia would unquestionably prove to be the more merciful, more

moral recourse. Such exceptions appear in about every socially

disputable theme, from love to state administration, from politics to

economy, and thus we have mostly succumbed to the idea that man-

made laws often fail.

The next reasonable assurance we have is in natural laws. Although

gravity, thermodynamics, optics and many other laws have pacified our

brains, there are still many fields which still frustrate our eagerness for

order. Biology, also known as the science of exceptions, falls into this

category. The field which tries to distribute living organisms after

stringent rules allows exceptions because of the rich diversity that has

resulted from mutations, genetic recombinations and evolution. We know

since childhood, for instance, that among the defining characteristics of

any animal classified as mammal is giving birth to live young. The

platypus, in spite of being a mammal, happens to lay eggs. It is known

with certitude that roots are geotropic, being affected by gravity and thus

growing towards the soil. However, the roots of some tropical mangrove

plants, like the Red Mangrove from Venezuela, grow away from gravity,

evading the geotropism rule unanimosly accepted by biologists. Anything

from the color of blood, genetic characteristics or behavior can vary and

eviscerate the essence of an accepted definiton. As hard as humankind

may try, it is impossible to categorize such a heterogenous mass of data

and activity, let alone understand the processes behind them.

This type of chaos can sometimes confuse our species, or even deter its

perception of the world we live in. In spite of our lack of control, we

usually learn to accept and even appreciate exceptions. After all, life on

Earth can become quite predictable when dictated by exacting rules and

regulations. Our affinity for exception is, ultimately, what induces hope

and change for the better.

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5820)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1093)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (845)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (898)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (540)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (349)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (822)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (401)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Seismic Methods Advantages and DisadvantagesDocument1 pageSeismic Methods Advantages and DisadvantagesDedipyaNo ratings yet

- The Story of The StarsDocument206 pagesThe Story of The Starssajeewa99No ratings yet

- Astrological Combination of JobDocument11 pagesAstrological Combination of JobjebabalanNo ratings yet

- Cosmic Calendar ActivityDocument4 pagesCosmic Calendar ActivityMatt DiDonatoNo ratings yet

- Exercise Acidizing VSPDocument11 pagesExercise Acidizing VSPQuy Tran XuanNo ratings yet

- Pamphlet 02 - Evolution in A Nutshell PDFDocument2 pagesPamphlet 02 - Evolution in A Nutshell PDFgordomanotasNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1 (Lesson 2, Part 3) - Famous Filipinos in The Field of ScienceDocument22 pagesChapter 1 (Lesson 2, Part 3) - Famous Filipinos in The Field of ScienceJorel DiocolanoNo ratings yet

- (Komonov EtAL) Geochem Methods of ProspectingDocument412 pages(Komonov EtAL) Geochem Methods of Prospectingjavicol70No ratings yet

- Dhanjori Formation Singhbhum Shear Zone Unranium IndiaDocument16 pagesDhanjori Formation Singhbhum Shear Zone Unranium IndiaS.Alec KnowleNo ratings yet

- Daftar PustakaDocument2 pagesDaftar PustakaAbdul Aziz SlametNo ratings yet

- IELTS Exam Preparation - IELTS Academic 10 - Reading Passage 1Document2 pagesIELTS Exam Preparation - IELTS Academic 10 - Reading Passage 1Ioana Aurora Paslaru0% (1)

- Parks and Open SpacesDocument9 pagesParks and Open SpacesLyjie BernabeNo ratings yet

- G.5 1st Term Form BDocument5 pagesG.5 1st Term Form BSally ElEssawyNo ratings yet

- Wind LoadingDocument18 pagesWind LoadingStephen Ogalo100% (1)

- Mineralogy 1Document50 pagesMineralogy 1Karla Fermil SayenNo ratings yet

- 5 Basement Cu Belt Zambia PDFDocument51 pages5 Basement Cu Belt Zambia PDFAlberto Lobo-Guerrero SanzNo ratings yet

- Site Location: Rio de JanerioDocument11 pagesSite Location: Rio de JanerioAbdul SakurNo ratings yet

- Stefan-Boltzmann Law: 2 H C Exp 1Document16 pagesStefan-Boltzmann Law: 2 H C Exp 1RonyVargasNo ratings yet

- Debajit Borah: Professional QualificationDocument3 pagesDebajit Borah: Professional Qualificationdborah89No ratings yet

- Trucos de Pokemon EsmeraldaDocument50 pagesTrucos de Pokemon EsmeraldaWil Arias CNo ratings yet

- KP AstrologyDocument42 pagesKP Astrologyvydeo60% (5)

- Lab Rep 11Document15 pagesLab Rep 11Reign RosadaNo ratings yet

- Plant Life Cycle Passage For Plant LessonDocument2 pagesPlant Life Cycle Passage For Plant Lessonapi-241278585No ratings yet

- Geology NotesDocument2 pagesGeology NotesPriyankaNo ratings yet

- 03 Life TablesDocument7 pages03 Life TablesMonalisa Jeriska0% (1)

- Pdac 2017 Convention ProgramDocument104 pagesPdac 2017 Convention ProgramCecil Eduardo Angulo MarquezNo ratings yet

- Prasna NotesDocument24 pagesPrasna NotesRajeswara Rao NidasanametlaNo ratings yet

- A Guide To Understanding Land Surveys (Third Edition)Document254 pagesA Guide To Understanding Land Surveys (Third Edition)barupatty83% (6)

- Carl Linnaeus (Print)Document3 pagesCarl Linnaeus (Print)Liwen LiewNo ratings yet

- Principais Depositos Minerais DNPM CPRMDocument14 pagesPrincipais Depositos Minerais DNPM CPRMluizhmo100% (1)