Professional Documents

Culture Documents

SEG 2012 06 OK Kubiaczyk

SEG 2012 06 OK Kubiaczyk

Uploaded by

Monika Owsianna0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

13 views12 pagesThis document provides a summary and comparison of Frantz Fanon and Enrique Dussel's perspectives on colonialism in France and Spain. Fanon analyzed how French colonialism created racial divisions and constructed black identities as inferior through systems of education and social norms. Dussel critiques the framing of European discovery and conquest of Latin America in 1492 as an "encounter," arguing it concealed domination of native peoples. Both thinkers examined how colonial powers employed racism and violence to establish colonial societies and shape the identities of colonized peoples in a way that still impacts post-colonial societies today.

Original Description:

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentThis document provides a summary and comparison of Frantz Fanon and Enrique Dussel's perspectives on colonialism in France and Spain. Fanon analyzed how French colonialism created racial divisions and constructed black identities as inferior through systems of education and social norms. Dussel critiques the framing of European discovery and conquest of Latin America in 1492 as an "encounter," arguing it concealed domination of native peoples. Both thinkers examined how colonial powers employed racism and violence to establish colonial societies and shape the identities of colonized peoples in a way that still impacts post-colonial societies today.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Download as pdf or txt

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

13 views12 pagesSEG 2012 06 OK Kubiaczyk

SEG 2012 06 OK Kubiaczyk

Uploaded by

Monika OwsiannaThis document provides a summary and comparison of Frantz Fanon and Enrique Dussel's perspectives on colonialism in France and Spain. Fanon analyzed how French colonialism created racial divisions and constructed black identities as inferior through systems of education and social norms. Dussel critiques the framing of European discovery and conquest of Latin America in 1492 as an "encounter," arguing it concealed domination of native peoples. Both thinkers examined how colonial powers employed racism and violence to establish colonial societies and shape the identities of colonized peoples in a way that still impacts post-colonial societies today.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Download as pdf or txt

You are on page 1of 12

83

FILIP KUBIACZYK, RACISM AND VIOLENCE

Filip Kubiaczyk

(Gniezno)

RACISM AND VIOLENCE. THE IMAGE OF A COLONISED HUMAN

IN THE EYES OF FRANTZ FANON AND ENRIQUE DUSSEL

1

Abstract

Te aim of the article is to compare Spanish and French vision of colonisation. By

drawing on the works of Frantz Fanon and Enrique Dussel, I intend to demonstrate

what mechanisms were employed by the French and the Spaniards to create a colonial

society. Te article also sets out to fnd how the contemporary inhabitants of the Latin

America and the Francophone Africa cope with the legacy of colonialism.

Keywords

colonialism, racism, violence, Frantz Fanon, Enrique Dussel, Spain, France

1

Polskojzyczna wersja artykuu pt. Rasizm i przemoc. Wizerunek czowieka skolonizo-

wanego wedug Frantza Fanona i Enrique Dussela ukazaa si [w:] H. Jakuszko i L. Kopciuch

(red.), Czowiek w kontekstach kulturowych i historycznych, Lublin 2012, s. 219232.

STUDIA EUROPAEA GNESNENSIA 6/2012

ISSN 20825951

84

STUDIA EUROPAEA GNESNENSIA 6/2012 IDEE

Colonialism lef a particular mark on the fates of the world. Te condition

of the societies inhabiting the former European colonies is a direct afermath

of the contact between Europe and the rest of the world, although in its as-

sumptions it was based on commendable premises and lofy ideals (civilising

mission, Christianisation, bringing help), it also had its darker side, constituted

by two phenomena of power: racism and violence. Our deliberations have the

aim of demonstrating how the French and the Spanish, by drawing on these

two categories, attempted to build their colonial societies. A research hypo-

thesis thus formulated will be examined through (re)interpretation of the major

works of Frantz Fanon

2

and Enrique Dussel

3

, in which they address the issue of

colonialism and the resulting negative consequences for the colonized societies.

We will be interested in the mechanisms by means of which the white Euro-

pean created the human of a diferent skin colour, causing the latter to desire

to change into a new white by renouncing their own race. Te intention is to

demonstrate how the French and the Spanish, in colonising through body,

efected a singular intercultural suspension between a European and a native.

In the conclusions, we are going to attempt a comparison of the two visions of

colonisation, especially in the context of the struggle that the societies of Latin

America and Francophone Africa wage on their post-coloniality.

THE FRENCH PLAY ON THE SKIN

Fanon, a Martinique-born researcher of colonialism frequently underlines

that the black inhabitants had in fact one dream: a total emulation of the lan-

guage and the accent of the coloniser, which at times turned simply into a lin-

guistic obsession of speaking like a white man. Te blacks strove to copy the

gestures, actions and the language of the white people. At the same time, Fanon

2

F. Fanon, Wyklty lud ziemi, transl. by H. Tygielska, Warszawa 1985; idem, Algieria zrzuca

zason, transl. by Zygmunt Szymaski, Warszawa 1962; idem, Piel negra, mascras blancas,

Editorial Abraxas, Buenos Aires 1973.

3

E. Dussel, 1492. El encubrimiento del Otro. Hacia el origen del mito de la Modernidad,

Plural Editores, La Paz 1994; idem, Europa, modernidad y eurocentrismo, [in:] Edgardo Lander

(ed.), Colonialidad del saber, eurocentrismo y ciencias sociales. Perspectivas latinoamericanas,

Buenos Aires 2000, p. 4153; E. Dussel, Hacia una flosofa poltica crtica, Bilbao 2001; idem,

Filosofa de la liberacin, Mxico 1977.

85

FILIP KUBIACZYK, RACISM AND VIOLENCE

observes that before the concept of ngritude

4

came into existence, no inhabit-

ant of the Antilles was capable of seeing themselves as a black person, although

they were actually black. As he expressed it in one of his most important books

in the Antilles, the vision of the world is white because no black version

of it exists

5

. It could not be any diferent since in the colonial schools black

pupils were educated in a whitened history of their land. As Fanon writes, in

the Antilles a young black man, ceaselessly repeating our Gaul forefathers at

school, indentifes with the white explorer and civiliser; with the one, therefore,

who brings the utterly white truth. Tere is genuine identifcation in it, as the

young black man subjectively adopts the attitude of the white man

6

. Fanon is

not the only one to provide this kind of examples

7

.

Tis white education lef its mark on the Antillean family, causing its men-

tal devastation. In this context, Fanon juxtaposes the black man with a Jew,

stating a certain irrational similarity in the stereotypical thinking about the

Other. Usually, when it comes to a Jew, he writes, we think about money and

its derivatives, while in the case of a black man, one thinks about sex

8

. Such

juxtaposition serves to reveal the fact that black persons were a substitute of the

Jew to the French. Te diference was that whereas the Jew was an intellectual

threat to Europe, a black person was a biological one. In Fanons opinion, to

have a phobia against a black man means to feel a fear of what is biological

9

.

Terefore black persons are by default described by means of such categories as

sex, strength, virility, savagery, animal, devil, sin. In this context, Fanon quotes

the example of French women who, motivated by fear, did not wish to be exam-

ined by a black gynaecologist, as well as the example of a white prostitute who

experienced orgasm at the very thought of intercourse with a black man

10

. He

4

Ngritude a literary and political movement started in the 1930 by Aim Cesaire in

the defence of Negrohood. It was a reaction to discrimination and cultural oppression of the

French colonial system. It defed the cultural assimilation and social policy of France.

5

F. Fanon, Piel negra, p. 126.

6

Ibidem, p. 122.

7

Boubou Hama and Andr Clair, when describing the various paradoxes encountered by

the African students attending French colonial schools write they head to repeat from memory

the characteristic sentence: Gauls, our ancestors, had blue eyes and fair hair. See their: Albarka

znaczy szansa, transl. by K. Witwicka, Warszawa 1977, p. 103.

8

F. Fanon, Piel negra, p. 136.

9

Ibidem.

10

Ibidem, p. 131132.

86

STUDIA EUROPAEA GNESNENSIA 6/2012 IDEE

also remembers his own traumatic experience he had one day in Paris, when

a little white girl walking in the street with her mother cried: Look, a black

one, Im scared

11

. Tat was when the stranger from Martinique personally

experienced racism. In principle, he was a Frenchman from the colonies, but

when he and many like him arrived from the French overseas dominions to the

metropolis, it turned out that there was something that defnitely distinguishes

them from the local inhabitant, namely the colour of the skin. Fanon realised

then that the black man has no ontological representation in the white eyes

and that in the white world, a coloured person fnds it difcult to develop their

corporeal formula

12

. According to Fanon, in the colonial world one fnds two

poles, one represented by the whites and the other by the blacks: I am white,

which means that mine are the beauty and bravery, which have never been

black. I am the colour of the day [] I am black, I bring about the total fusion

of the world, a sympathetic understanding of the earth, a self-abandonment in

the heart of cosmos

13

.

Fanon rendered the cruelty of the colonial world even more explicitly in

Te Wretched of the World. Te colonial world, he writes, is a world di-

vided, Manichean [] Te colonised live in the state of constant tension in the

face of the colonial arrangement. Te world of the coloniser is a hostile one,

a world which repels and attracts at the same time [] the colonised ceaselessly

dream of being the coloniser, of taking their place. Te world hostile, over-

whelming and aggressive, repelling the colonised mass with all means available

is not an image of hell, from which one would like to run as fast as possible,

but a paradise existing within the reach of ones hand, guarded by cerberi

14

.

In this Manichean reality, where the divisions are demarcated by the barracks

and police stations

15

, one side can do everything, the other nothing.

All the dilemmas discussed so suggestively by Fanon are concisely summed

up by H. Bhabha in his classic book: Te sight of the white man crushes the

body of the black one, and in committing this act of epistemological violence,

he violates his own frame of reference and disturbs his own feld of vision

16

.

11

Ibidem, p. 90.

12

Ibidem, p. 91.

13

Ibidem, p. 37.

14

F. Fanon, Wyklty lud, p. 3031.

15

Ibidem, p. 21

16

Homi Bhabha, Miejsca kultury, transl. by T. Dobrogoszcz, Cracow 2010, p. 30.

87

FILIP KUBIACZYK, RACISM AND VIOLENCE

THE SPANISH FRAUD

Usually, the year 1492 brings to mind the discovery of America, yet Ameri-

ca was not new for itself but for the Europeans. Dussel claims that at that time,

America was covered

17

by Europe personifed by the Spaniards. In this context

the Argentinean philosopher also rejects the notion of the encounter, which

began to be used on the 500

th

anniversary of Columbus voyage. He justifes

his objection thus: Te term encounter is a covering one since it constitutes

itself by concealing the domination of the European I and its world over

the world of the Other, the native

18

. Tus the entire project of colonising

America was founded on the myth of modernity, which consisted in making the

victims into the guilty ones. Dussel calls is a gigantic reversal (una gigantesca

inversin)

19

. Tanks to such a device the conquest is a practical afrmation of

the one who conquers and negation of the Other as the other

20

. Violence

played a fundamental role in the contact between the Spaniards and the na-

tive peoples of America. Te frst relation, writes Dussel, was a relation of

violence: a military relation between the conquering and the conquered []

Te frst experience of modernity was an almost divine superiority of the Eu-

ropean I over the primitive and uncouth Other

21

. Te relation was also

characterised by erotic violence, what is more, the conquest was successful

largely thanks to the Spanish conquest of the native women. In Dussels view

the conquistador, a violent and belligerent ego, was also a phallic ego

22

, who

kills a Native Indian male or reduces him to a relation of submission, goes to

bed with an Native Indian woman (in the presence of the Indian male at that)

and cohabits with her, as they would put it in the 16

th

century. Simultaneously

it was a sadistic violence: it was about fulflling lecherous pleasure [] where

the erotic relation is synonymous with domination over the Other (Native In-

dian women). Consequently, there ensues a colonisation of the Indian women,

Spanish eroticism is established, the double morality of machismo introduced:

17

E. Dussel, 1492. El encubrimiento del Otro, p. 35.

18

Ibidem, p. 62

19

Ibidem, p. 74.

20

Ibidem, p. 47

21

Ibidem, p. 44

22

Ibidem, p. 50.

88

STUDIA EUROPAEA GNESNENSIA 6/2012 IDEE

the sexual domination of the Indian female and visible respect for the European

woman. Tis relationship will bring forth the illegitimate son (el hijo bastardo),

the Mestizo, a Latino, the fruit of conquistador and an Indian woman, and

the criollo, a white person born in the colonial world of the West Indies

23

.

Te arrival of the European conquistadors and the African slaves in the New

World caused a disruption of the ethnic and cultural unity which had existed

on the continent. Since that moment, a gigantic biological cross-breeding be-

tween the Indians, the whites and the blacks

24

began. As a result, a new culture

would come into being, a culture syncretic and hybrid, whose subject would

be of mixed race, far from being an outcome of alliance or a process of cultural

synthesis, but an efect of domination or trauma

25

.

Let us draw attention to the fact that ego conquiro was not only expressed in

the military and corporal violence, but also in the spiritual one. Seen from this

perspective, the strategies of colonisation are not a project of destruction but

production. Tis is not merely about the physical elimination of the colonised,

but adjusting them to life, i.e. providing them with such forms of existence that

would correspond with the modernisation project. In order to eliminate the

native forms of consciousness: their system of notions, symbols and the ways

of assigning meaning, which were considered useless, the colonisers resorted

to what Gayatri Spivak called epistemological violence. In the assessment of the

colonisers, these forms were merely myths, a pre-scholarly, magical conscious-

ness etc. And if they could not be utterly eradicated, they were deprived of

ideological foundations and subjugated. Already the evangelisation of the 15

th

and the 16

th

century made the Indians and the African learn to reject their own

forms of shaping the consciousness so as to adopt those of the colonisers, which

granted greater social prestige. Te colonial imaginarium exercised a ceaseless

infuence on the desires, aspirations and the will of the subjects. Te European

culture, writes Quijano turned into a temptress; it gave access to power. Ulti-

mately, rather than repression, seduction is the chief instrument of power. Te

Europeanisation of culture transformed into an aspiration. It was a means of

partaking in the colonial power

26

. A particular role belonged to the notion of

23

Ibidem, p. 51.

24

Amores Carredano (ed.), Historia de Amrica, Barcelona 2006, p. 336.

25

E. Dussel, 1492. El encubrimiento del Otro, p. 62.

26

Anbal Quijano, Colonialidad y modernidad-racionalidad, [in:] H. Bonilla (ed.), Los con-

quistados. 1492 y la poblacin indgena de las Amricas, Bogot 1992, p. 439.

89

FILIP KUBIACZYK, RACISM AND VIOLENCE

whiteness shaped by the discourse of the purity of blood, a notion associ-

ated not so much with the colour of the skin, but with a personal transposition

into the cultural imaginarium woven from religious beliefs, the type of attire,

manner in which one behaved and, most importantly, by the forms of develop-

ing and transferring consciousness. Westernisation of the Others imaginarium

was manifested in the eforts to emulate the European models in all domains

of existence, at the level of institution, customs, thinking, education, art etc.

Hence, the myth of modernity itself defnes its own culture as a better, more

developed one, while on the other determining any other culture as inferior,

simple, barbaric, an object of culpable immaturity

27

. Tus domination, war

and violence employed on the others are presented as emancipation, usefulness

and good for the barbarian who is being civilised, who develops or modernizes

themselves. Dussel aptly emphasizes that thanks to America, its frst periphery,

Europe became not world capital of economic, scientifc and technological

advancement, but also the frst universal value system

28

.

LEAVING THE COLOUR CAGE

Te problems addressed by Fanon in his works still hold relevant for France,

which apparently fails to cope with the burden of its colonial past. It would be

sufcient to quote the French bill of February 23

rd

, 2005 (ultimately did not come

into force), which attempted to impose the obligation on teachers to teach only

about the positive role of French colonisation, or the reaction of the authorities to

the autumn riots of 2005, when the then minister of the interior, Nicolas Sarkozy,

blamed the riots on the immigrants, calling them rabble and gangrene

29

. Min-

ister Sarkozys aversion to immigrants was anything but a one-of incident, if, al-

ready a president of France he demonstrated similar arrogance in July 2007, dur-

ing the meeting with students of the Cheikha-Anta-Diopa university in Dakar.

Tat was when he spoke the signifcant words, which even today are commented

upon: Young Africans, I have not come here to apologize [] Te suferings of

the black people, black women and black men are the suferings of all humanity

27

E. Dussel, 1492. El encubrimiento del Otro, s. 70.

28

E. Dussel, Europa, modernidad, s. 46.

29

Afer: Rasizm la franaise. Wywiad z Liliamem Turamem, Forum 7, 1521.02. 2010,

p. 26.

90

STUDIA EUROPAEA GNESNENSIA 6/2012 IDEE

[] . Te real tragedy of this continent is that the African has never made his-

tory for good []

30

. Sarkozys stance proves that in the country on the Seine,

the nationalist, racist and xenophobic tendencies are still alive, tendencies which

betoken dislike of immigrants who afer all had been supposed to be French

31

. Te

phenomenon may be accounted for by the transcultural concept of a scapegoat

32

that Ren Girard writes about. In his opinion, the mechanisms of looking for

scapegoats multiply wherever human groups attempt to shut themselves out

in the identity of their community, place, nation, ideology, race, religion etc.

33

.

Tis is why Liliam Turam

34

objects to Sarkoization of thinking, as he puts it:

As long as we remain prisoners of the 19

th

-century ideology, which classifed

people into alleged lower and higher races in order to justify the existence of

colonies, we will not be capable of comprehending that being black or white is

the consequence of appropriate circumstances. No child is born black or white.

Possibly, it may be born pink, beige and brown. We only become black or white.

One should break out of this cage of colour, decolonise our minds. We shall ac-

complish it by transforming our world of notions

35

.

GIVE VOICE TO THE MARGINALISED

Te symbolic and cultural colonisation of Latin America as the frst pe-

riphery played a key role in consolidating the hegemonic power of Europe and

30

Afer: J. Ziegler, Nienawi do Zachodu, transl. by E. Cylwik, Warszawa 2010, p. 8789.

31

At this point, it would be worthwhile to quote the term volu (lit. evolved), which was

used in the colonial times to describe the indigenous inhabitants of the colonies who spoke

French, obtained European education and live according to European standards, achieving

a certain civilisational stage of development. In this context, one could ironically ask who

should evolve more today: the immigrants of the former colonies or those who rule the former

metropolis?

32

R. Girard, Kozio ofarny, transl. by M. Goszczyska, d 1986.

33

Idem, Widziaem szatana spadajcego z nieba jak byskawica, transl. by E. Burska,

Warszawa 2002, p. 173.

34

Liliam Turam was born in 1972 in Guadeloupe, moving to France at the age of 9. He

was a leading footballer in football clubs and multiple French representative. Having fnished

footballing career in 2008, he became involved in the fght against racism and social injustice.

For this end, he established the Education contre le Racisme Foundation (Education Against

Racism).

35

Rasizm la franaise, p. 28.

91

FILIP KUBIACZYK, RACISM AND VIOLENCE

creating Eurocentric modernity. As Dussel demonstrates, as of the 15

th

century,

the modern system-world propagated itself always by means of violence, both

military and cultural one, which constituted the relations with other systems,

cultures, nations and individuals. Since 1492 the modern Europe, or later the

United States, never initiated the process of including other peripheral cul-

tures through peaceful and rational argumentation

36

. Te colonial logic was

a logic of exclusion. In the colonial order there is no place for the narration of

the Other. Te frst fgure to be negated by the modernity was the American

native. Te example of the Latin America corroborates the structural depend-

ence of the periphery on the logic of colonial paradigms. In order to leave that

cultural-symbolic dependence Dussel contrasted Eurocentric modernity which

excludes the inhabitants of the periphery with the modernity existing from

the world horizon, where the other is included

37

. He formulates the project of

trans-modernity (transmodernidad) construed as afrmation of multicultural-

ism excluded by the European modernity

38

. Unlike the project of Habermas

39

,

who propounded achievement of unfnished and incomplete modernity, Dus-

sels project is oriented towards achievement (in the long run) of an unfnished

and incomplete project of decolonisation. Dussel borrows Levinas notion of

exteriority

40

, which does not imply the ontological outside, but refers to the

exterior which comes into existence as a diference produced by hegemonic

discourse. As a system, European philosophy claims the right to eliminate oth-

erness, a diference which Levinas denotes as Autrui. In this context, the other

is what is external with respect to the system. For Dussel, the notion of exteri-

ority essentially emerges from thinking about the Other from the viewpoint

of ethical philosophy of liberation: the Other as the oppressed, the excluded,

the poor etc. It is from the exterior where he dwells, the Other stands in the

36

E. Dussel, Hacia una flosofa, p. 370.

37

Ibidem, p. 357.

38

Enrique Dussel, Sistema-Mundo y Transmodernidad, [in:] S. Dube, I. Banerjee,

W. Mignolo (ed.), Modernidades coloniales, Mxico 2004, p. 218. Te article originally in Eng-

lish: World-System and Transmodernity, [in:] Nepantla. Views from South (Duke, Durham),

3, 2, 2002, p. 211244.

39

J. Habermas, Filozofczny dyskurs nowoczesnoci, transl. by M. ukaszewicz, Krakw

2005.

40

For the French philosopher, the relation with the Other occurs as separation and

closely associated desire of the other, and through the other, infnity. See: E. Lvinas, Cao

i nieskoczono. Esej o zewntrznoci, transl. by M. Kowalska, Warszawa 1998.

92

STUDIA EUROPAEA GNESNENSIA 6/2012 IDEE

light of discourse vis vis the hegemonic entirety. Te category of exterior-

ity, which permits to initiate discourse from the periphery is a domain from

which the Other reveals themselves. Exteriority becomes a practical reality

when the Other presents themselves as the negativity of the system, when they

explode and show their face and their rights. Dussel says that the face of the

Other (the mestizo, the African slave etc.), which is personifed by the people,

it is an explosion of a diferent history, it is a face of the gender, generation,

social class, nation, cultural group, period in history

41

. A good example is

provided by the autobiographical work of Rigoberta Mench

42

, Guatemalan

Maya Indian, where Western modernity is acutely criticised. Te 1992 Nobel

Peace Prize winner begins her book thus: My name is Rigoberta Mench. I am

twenty three years old. Tis is my testimony. I have not learned it from a book

nor did I found out myself [] My story is the story of all poor Guatemalans.

My personal experience is the reality of all people

43

.

CONCLUSIONS

J. Kieniewicz defnes colonialism as a complex of factors which cause the

subordinated society to lose the capacity of autonomous development and also

to adopt the vision of the world created by an alien dominant system

44

. How-

ever, one should ask whether in the context of relations between Latin Ameri-

can and African societies and their former metropolises one may speak about

a shared experience of colonialism? It seems that the diferences are evident.

Te French approach to the heritage of colonialism displays a visible primacy

of politics over culture. Tis is borne out for instance by the aforementioned

project of a bill obligating teachers to pass on knowledge about the positive

role of colonialism exclusively, or by Nicolas Sarkozys attitude. Te fnal ex-

ample is ofered by the designs of the French Football Federation to limit the

recruitment of descendants of people from former colonies to football schools

and the French national team. As may be seen, despite the 50 years that have

elapsed since Fanon, racism is still alive in the country on the Seine. Meanwhile,

41

E. Dussel, Filosofa de la liberacin, p. 59.

42

R. Mench, Mi nombre es Rigoberta Mench y as me naci la conciencia, Mxico 1984.

43

Ibidem, p. 1.

44

J. Kieniewicz, Ekspansja, cywilizacja, kolonializm, Warszawa 2008, p. 120.

93

FILIP KUBIACZYK, RACISM AND VIOLENCE

in Spain, one observes a primacy of culture over politics. From the very out-

set, Spain implanted its language, culture and tradition in the seized colonies.

Tis forged a strong bond between the metropolis and the colonies, which has

lasted until the present day. Almost two centuries from the decolonisation of

America, Spain is still present in the life of its former colonies. It participates

not only in the Iberian-American summits, but also acts in the interest of Latin

American states on the international scene. It should be emphasized that when

Spain decided to withdraw forces deployed to Iraq, Latin American countries

immediately followed suit. It seems that of all countries that possessed colonial

empires, Spain renders most assistance to its former colonies in overcoming

the post-colonial burden.

Perhaps the diferences should be accounted for by the diverse origins of

Spanish and French colonialism. Colonisation of the Latin America was a di-

rect afermath of the voyages of discoverers. Church was a key institution in

the colonisation process and today the region is considered a bastion of world

Catholicism. French colonisation difers in the essentials. France, which already

in the 16

th

century preferred to fraternise with Turkey against Christian states,

contributed greatly to the downfall of Christian unity. Terefore, unlike the Spa-

nish one, French colonial expansion was not motivated by the evangelisation

mission. Te incentive lay strictly in the political and economic expedient.

Filip Kubiaczyk

RASIZM I PRZEMOC. WIZERUNEK CZOWIEKA SKOLONIZOWANEGO

W OCZACH FRANTZA FANONA I ENRIQUE DUSSELA

Streszczenie

Kolonializm w sposb szczeglny odcisn swoje pitno na losach wiata. Kondycja

spoeczestw zamieszkujcych dawne kolonie europejskie jest bezporednim owocem

kontaktu Europa reszta wiata, ktry, cho w swoich zaoeniach opiera si na

chlubnych przesankach i szczytnych ideach (cywilizowanie dzikich, chrystianizacja,

niesienie pomocy), mia take swoj ciemn stron. Konstytuuj j przede wszystkim

dwa fenomeny wadzy: rasizm i przemoc. Autor artykuu, analizujc prace Frantza Fa-

nona i Enrique Dussela, pokazuje, w jaki sposb Francuzi i Hiszpanie odwoujc si do

tych dwu kategorii, prbowali zbudowa swoje kolonialne spoeczestwa z wszystkimi

tego konsekwencjami. Fanon, opisujc kolonizacj jako fenomen przemocy, jego jdro

94

STUDIA EUROPAEA GNESNENSIA 6/2012 IDEE

upatrywa wanie w rasizmie. Pochodzcy z Martyniki pisarz pokazuje, jak kultura

europejska rocia sobie prawo do reprezentowania kultur tubylczych w byych kolo-

niach francuskich, zwaszcza na Antylach. W tym kontekcie autor artykuu pooy

szczeglny nacisk na zbadanie fenomenu dwch wiatw biaego i czarnego

wedug okrelenia Fanona. Chodzi o mechanizmy, za pomoc ktrych biay czowiek

kreowa czowieka o czarnym kolorze skry, powodujc, e ten wyrzekajc si swojej

rasy, chcia zmieni si w nowego biaego. Autor dowodzi, e Francuzi, kolonizujc

niejako poprzez ciao, doprowadzali do swoistego zawieszenia midzykulturowego

midzy Europejczykiem a tubylcem. Z kolei odwoanie si do prac Dussela pokazuje,

e w roku 1492 Ameryka zostaa zakryta przez Europ uosabian wwczas przez

Hiszpanw. W ten sposb cay projekt kolonizacji Ameryki zosta ufundowany na

tzw. micie nowoczesnoci polegajcym na uczynieniu z ofar (ludw prekolumbij-

skich) winnych, a z oprawcw stosujcych przemoc (Hiszpanw) niewinnych. Autor

analizuje argumenty, ktre w opinii argentyskiego flozofa suyy Europejczykom

do opisywania i kategoryzowania Nowego wiata (ewangelizacja, idea Ameryki jako

utopii Europy, idea wojny sprawiedliwej etc.), a ktre w wikszoci nie byy niczym

innym, jak usprawiedliwianiem fenomenu przemocy aplikowanej przez Europejczy-

kw ludom i kulturom nieeuropejskim. W konkluzji autor pokusi si o porwnanie

hiszpaskiej i francuskiej wizji kolonizacji, zwaszcza w kontekcie zmagania si ze

swoj postkolonialnoci przez spoeczestwa Ameryki aciskiej i francuskojzycz-

nej czci Afryki.

You might also like

- Appendectomy Nurses' NotesDocument1 pageAppendectomy Nurses' NotesCymargox100% (4)

- What Fanon Said: A Philosophical Introduction to His Life and ThoughtFrom EverandWhat Fanon Said: A Philosophical Introduction to His Life and ThoughtNo ratings yet

- Ara Ditis Patris Et Proserpinae Samuel Ball Platner A Topographical Dictionary of Ancient RomeDocument1 pageAra Ditis Patris Et Proserpinae Samuel Ball Platner A Topographical Dictionary of Ancient RomeMonika OwsiannaNo ratings yet

- Racism and Violence The Image of A ColonDocument12 pagesRacism and Violence The Image of A ColonMagdalena JanuszkoNo ratings yet

- AssignmentDocument3 pagesAssignmentAshutoshNo ratings yet

- 05-Chapter 2Document29 pages05-Chapter 2Atul RanjanNo ratings yet

- Essay - Heart of Darkness by Joseph ConradDocument6 pagesEssay - Heart of Darkness by Joseph ConradKarin LoboNo ratings yet

- Études Postcoloniales Et RomansDocument20 pagesÉtudes Postcoloniales Et RomansEl bouazzaoui MohamedNo ratings yet

- Frantz FanonDocument2 pagesFrantz FanonAlex BojovicNo ratings yet

- Summary of The Wretched of The Earth by MeDocument7 pagesSummary of The Wretched of The Earth by MeImene SaturdayNo ratings yet

- The Colonized Fall Apart - A Postcolonial Analysis of Chinua Achebe's Things Fall Apart in Light of Frantz FanonDocument10 pagesThe Colonized Fall Apart - A Postcolonial Analysis of Chinua Achebe's Things Fall Apart in Light of Frantz FanonRani JeeNo ratings yet

- On National Culture - Wretched of The EarthDocument27 pagesOn National Culture - Wretched of The Earthvavaarchana0No ratings yet

- Chapter-2 Post-Modern Blackness and The Bluest EyeDocument41 pagesChapter-2 Post-Modern Blackness and The Bluest EyeMęawy MįlkshãkeNo ratings yet

- Commodification in Frantz Fanon's...Document5 pagesCommodification in Frantz Fanon's...chunu2073No ratings yet

- Franz FanonDocument7 pagesFranz FanonAparna KNo ratings yet

- Titus Pop From Eurocentrism To Hibridity or From Singularity To PluralityDocument9 pagesTitus Pop From Eurocentrism To Hibridity or From Singularity To PluralityarbayaseharingNo ratings yet

- LabanyiDocument17 pagesLabanyiPablo Rubio GijonNo ratings yet

- Ajol File Journals - 274 - Articles - 79613 - Submission - Proof - 79613 3265 187199 1 10 20120725Document13 pagesAjol File Journals - 274 - Articles - 79613 - Submission - Proof - 79613 3265 187199 1 10 20120725dansochristiana574No ratings yet

- Lecture 3 BFanon 2016Document22 pagesLecture 3 BFanon 2016m75354334No ratings yet

- En122 Fanon-2018Document17 pagesEn122 Fanon-2018typaldaki78No ratings yet

- Fanon and DecolonizationDocument6 pagesFanon and DecolonizationSaima yasinNo ratings yet

- Political Philosophy: Frantz Fanon (1925-1961)Document5 pagesPolitical Philosophy: Frantz Fanon (1925-1961)Edno Gonçalves SiqueiraNo ratings yet

- PC Studies - Condensed PowerPoint PresentationDocument55 pagesPC Studies - Condensed PowerPoint PresentationAnindita XavierNo ratings yet

- Wretched of The EarthDocument7 pagesWretched of The EarthSK AMIR SOYEL100% (1)

- qt4ph014jj NosplashDocument31 pagesqt4ph014jj NosplashHanna PatakiNo ratings yet

- Barry Po-Co CriticismDocument6 pagesBarry Po-Co CriticismSara LilyNo ratings yet

- Group1 Representation of Black in Heart of DarknessDocument6 pagesGroup1 Representation of Black in Heart of Darknesssafder aliNo ratings yet

- Sartre and Fanon: On Negritude and Political ParticipationDocument16 pagesSartre and Fanon: On Negritude and Political ParticipationCarlosPerezNo ratings yet

- Robin D.G. Kelly Notes Feb 7thDocument1 pageRobin D.G. Kelly Notes Feb 7thanthony jacksonNo ratings yet

- Paper Two PrepDocument2 pagesPaper Two Prepderek_caswellNo ratings yet

- Aime Cesaire, Robin D.G. Kelley Discourse On Colonialism 2001Document52 pagesAime Cesaire, Robin D.G. Kelley Discourse On Colonialism 2001Precariat Dab100% (11)

- The Royal Road To The Colonial Unconscious': Psychoanalysis, Cannibalism, and The Libidinal Economy of ColonialismDocument21 pagesThe Royal Road To The Colonial Unconscious': Psychoanalysis, Cannibalism, and The Libidinal Economy of ColonialismMatheus Bravati RuedaNo ratings yet

- Colonization in Heart of Darkness: COURSE NAME: Modern Novel (Bs English)Document6 pagesColonization in Heart of Darkness: COURSE NAME: Modern Novel (Bs English)safder ali100% (1)

- Wilson QuarterlyDocument7 pagesWilson QuarterlyÇağrı OkukluNo ratings yet

- Frantz FanonDocument6 pagesFrantz FanonOns AlkhaliliNo ratings yet

- Boukha LK Hal Yass MineDocument14 pagesBoukha LK Hal Yass MineAdnan KhanNo ratings yet

- Frantz FanonDocument42 pagesFrantz FanonKarlo Mikhail Mongaya100% (1)

- Existencialismo, Dialéctica y Revolución PDFDocument20 pagesExistencialismo, Dialéctica y Revolución PDFLiz L.No ratings yet

- Colonialism and Post ColonialismDocument6 pagesColonialism and Post Colonialismali53mhNo ratings yet

- To Save The WorldDocument2 pagesTo Save The WorldKhamani GriffinNo ratings yet

- Frantz Fanon Perspectives On Post Colonialism - PDFDocument4 pagesFrantz Fanon Perspectives On Post Colonialism - PDFMomna ShahidNo ratings yet

- Political Disillusionment in The Racist South African LandscapesDocument32 pagesPolitical Disillusionment in The Racist South African LandscapesMehwish MalikNo ratings yet

- A Tempest As Postcolonial TextDocument9 pagesA Tempest As Postcolonial TextTaibur RahamanNo ratings yet

- Decolonising Development With Frantz FanonDocument4 pagesDecolonising Development With Frantz FanonmatthewmcdonaldmailNo ratings yet

- Black Jew Arab by Ella ShohatDocument16 pagesBlack Jew Arab by Ella Shohatsousan_hammadNo ratings yet

- THE EVIL OF MODERNITY: JOSEPH CONRAD'S HEART OF DARKNESS AND FRANCIS FORD COPPOLA'S APOCALYPSE NOW Michel MaslowskiDocument17 pagesTHE EVIL OF MODERNITY: JOSEPH CONRAD'S HEART OF DARKNESS AND FRANCIS FORD COPPOLA'S APOCALYPSE NOW Michel MaslowskiAeosphorusNo ratings yet

- Nsukka Journal of The Humanities, Number 14, CHIMAMANDA NGOZI ADICHIE THE PURPLE HIBISCUS - AN ALLEGORICAL STORY OF MAN STRUGGLE FOR FREEDOMDocument24 pagesNsukka Journal of The Humanities, Number 14, CHIMAMANDA NGOZI ADICHIE THE PURPLE HIBISCUS - AN ALLEGORICAL STORY OF MAN STRUGGLE FOR FREEDOMAlex WasabiNo ratings yet

- Frantz FanonDocument17 pagesFrantz FanonEhab ShawkyNo ratings yet

- Postcolonial Philosophy and Culture in Joseph Conrad's Heart of DarknessDocument13 pagesPostcolonial Philosophy and Culture in Joseph Conrad's Heart of DarknessZaini saleemNo ratings yet

- A Postcolonial Reading of Kurtz in Heart of DarknessDocument6 pagesA Postcolonial Reading of Kurtz in Heart of Darknesstalal.saleh2203No ratings yet

- RacismDocument6 pagesRacismapi-744681971No ratings yet

- Alejandra PizarnikDocument5 pagesAlejandra PizarnikCande GencarelliNo ratings yet

- Living With Ghosts: Legacies of Colonialism and Fascism: Resources - L'Internationale BooksDocument96 pagesLiving With Ghosts: Legacies of Colonialism and Fascism: Resources - L'Internationale BooksTúlio RosaNo ratings yet

- My ThesisDocument4 pagesMy Thesisndip agborNo ratings yet

- Earl Gian GDocument10 pagesEarl Gian GDyna PanizalesNo ratings yet

- Frantz Fanon's Contribution To Psychiatry The Psychology of Racism and ColonialismDocument4 pagesFrantz Fanon's Contribution To Psychiatry The Psychology of Racism and ColonialismHueyfreeman7No ratings yet

- Post ColonialismDocument21 pagesPost Colonialismfalak chaudharyNo ratings yet

- Mignolo - Dispensable and Bare Lives - Coloniality and The Hidden Political-Economic Agenda of ModernityDocument19 pagesMignolo - Dispensable and Bare Lives - Coloniality and The Hidden Political-Economic Agenda of Modernityvroda1No ratings yet

- (2003) Clair - The Changing Story of Ethnography (Expressions of Ethnography)Document24 pages(2003) Clair - The Changing Story of Ethnography (Expressions of Ethnography)dengamer7628No ratings yet

- O Captain! My Captain! by Walt WhitmanDocument3 pagesO Captain! My Captain! by Walt WhitmanMonika Owsianna0% (1)

- O Captain! My Captain! by Walt WhitmanDocument3 pagesO Captain! My Captain! by Walt WhitmanMonika Owsianna0% (1)

- RBA Virgil, Aeneid VI. 545, CR 1921Document2 pagesRBA Virgil, Aeneid VI. 545, CR 1921Monika OwsiannaNo ratings yet

- K K T T, K, K T T: Nowing The Nowing The IME IME Nowing of A Nowing of A IME IMEDocument6 pagesK K T T, K, K T T: Nowing The Nowing The IME IME Nowing of A Nowing of A IME IMEMonika OwsiannaNo ratings yet

- RICHMOND, Propertivs and The Aeneid, CQ 1917Document4 pagesRICHMOND, Propertivs and The Aeneid, CQ 1917Monika OwsiannaNo ratings yet

- GENOVESE, Deaths in The Aeneid, PCP 1975Document8 pagesGENOVESE, Deaths in The Aeneid, PCP 1975Monika OwsiannaNo ratings yet

- The Rise of CaesarDocument10 pagesThe Rise of CaesarMonika OwsiannaNo ratings yet

- Złoty Wiek WergiliuszaDocument21 pagesZłoty Wiek WergiliuszaMonika OwsiannaNo ratings yet

- Ansi Z535.2-2002Document42 pagesAnsi Z535.2-2002Leonardo Nicolás Nieto SierraNo ratings yet

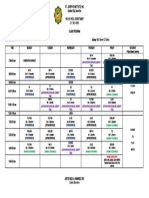

- 9 St. Catherine Class ScheduleDocument1 page9 St. Catherine Class ScheduleAleah TungbabanNo ratings yet

- 2013 Rotary Index Drives Manual1Document16 pages2013 Rotary Index Drives Manual1Manoj TiwariNo ratings yet

- Tomb Raider Underworld (Europe) (PC) (En, FR, De, Es, It) (v1.1) - Crystal Dynamics - Free Download, Borrow, ADocument1 pageTomb Raider Underworld (Europe) (PC) (En, FR, De, Es, It) (v1.1) - Crystal Dynamics - Free Download, Borrow, Afrancisco perezNo ratings yet

- Peter GärdenforsDocument9 pagesPeter GärdenforsusamaknightNo ratings yet

- Progress TestDocument9 pagesProgress TestvhtproNo ratings yet

- Effect of Raw Meal Fineness On Quality of ClinkerDocument6 pagesEffect of Raw Meal Fineness On Quality of ClinkerPrasann R Namannavar100% (1)

- Entrepreneurial PropensityDocument11 pagesEntrepreneurial PropensitymuhammadtaimoorkhanNo ratings yet

- Resume Sample For TeenagerDocument6 pagesResume Sample For Teenagerafjwoovfsmmgff100% (2)

- Installment Plans at 0% Markup Rate: Credit CardDocument2 pagesInstallment Plans at 0% Markup Rate: Credit CardHeart HackerNo ratings yet

- Saic-Q-1066 Rev 1 (Final)Document3 pagesSaic-Q-1066 Rev 1 (Final)ryann mananquilNo ratings yet

- Square Footage Facts: 10 Simple References About Home SizeDocument12 pagesSquare Footage Facts: 10 Simple References About Home SizeSteven Randel100% (1)

- Local Media8674470670761638698Document14 pagesLocal Media8674470670761638698NashNo ratings yet

- Macys Resume-2-2Document2 pagesMacys Resume-2-2api-269130288No ratings yet

- Spanning Space, Horizontal-Span Building Structures, Wolfgang SchuellerDocument752 pagesSpanning Space, Horizontal-Span Building Structures, Wolfgang Schuellerwolfschueller91% (11)

- Eligion and Edia: Elissa OnroyDocument3 pagesEligion and Edia: Elissa OnroyAltaibaatar JargalNo ratings yet

- Yea Kaeps800000042k SGDV Ac APDocument24 pagesYea Kaeps800000042k SGDV Ac APthanh_cdt01No ratings yet

- Book Order FormDocument2 pagesBook Order Formbinaya BehuraNo ratings yet

- Syllabus PDFDocument51 pagesSyllabus PDFPalashNo ratings yet

- Bulldozer: Tough World. Tough EquipmentDocument2 pagesBulldozer: Tough World. Tough EquipmentedholminNo ratings yet

- WPS - 016Document11 pagesWPS - 016MAT-LIONNo ratings yet

- Croon's Bias-Corrected Factor Score Path Analysis For Small-To Moderate - Sample Multilevel Structural Equation ModelsDocument23 pagesCroon's Bias-Corrected Factor Score Path Analysis For Small-To Moderate - Sample Multilevel Structural Equation ModelsPhuoc NguyenNo ratings yet

- Technological Institute of The Philippines Course Syllabus: ENGL 253 / 313/293 Technical WritingDocument4 pagesTechnological Institute of The Philippines Course Syllabus: ENGL 253 / 313/293 Technical WritingtipqccagssdNo ratings yet

- Magnetic Electricity GeneratorDocument3 pagesMagnetic Electricity GeneratorShahriar RahmanNo ratings yet

- Volkswagen TransporterDocument3 pagesVolkswagen TransporterTasawar ShahNo ratings yet

- DanielsDocument5 pagesDanielstv_whiteboyNo ratings yet

- Creating Barcodes in OfficeDocument24 pagesCreating Barcodes in OfficeMaxi Rambi RuntuweneNo ratings yet

- Ainscow, Farrell y Tweddle IJIE - 00 Developing Policies For Inclusive EducationDocument19 pagesAinscow, Farrell y Tweddle IJIE - 00 Developing Policies For Inclusive EducationMatías Reviriego RomeroNo ratings yet