Professional Documents

Culture Documents

VERB Campaign

VERB Campaign

Uploaded by

Jesse M. MassieCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- Test Bank For Womens Gynecologic Health 3rd Edition SchuilingDocument4 pagesTest Bank For Womens Gynecologic Health 3rd Edition SchuilingMichael Pupo33% (9)

- Textbook Discovering The Lifespan Feldman Ebook All Chapter PDFDocument53 pagesTextbook Discovering The Lifespan Feldman Ebook All Chapter PDFethel.maedche320100% (13)

- The Effects of Social Media On Mental Health of Selected Senior High School StudentsDocument26 pagesThe Effects of Social Media On Mental Health of Selected Senior High School StudentsJeandra Villanueva87% (39)

- Social Marketing TheoryDocument4 pagesSocial Marketing TheorySintija92% (13)

- CONQUEST OF THE SERPENT-A Way To Solve The Sex ProblemDocument55 pagesCONQUEST OF THE SERPENT-A Way To Solve The Sex ProblemPrecisionetica100% (1)

- Introduction To Child Development PDFDocument18 pagesIntroduction To Child Development PDFVAISHNAVINo ratings yet

- Media and Social Marketing: League International Photo by Margo Geist, Courtesy of La LecheDocument4 pagesMedia and Social Marketing: League International Photo by Margo Geist, Courtesy of La LecheNOVA LESLIE AGAPAYNo ratings yet

- Social Marketing PRJCTDocument19 pagesSocial Marketing PRJCTanishuNo ratings yet

- How Social Marketing Works in Health CareDocument8 pagesHow Social Marketing Works in Health CareMuhammad Shafiq GulNo ratings yet

- PNABL671 Healthcom MethodologyDocument8 pagesPNABL671 Healthcom MethodologyMuhammad Ikhsan AmarNo ratings yet

- Communication Arts: Consumer Awareness of Advertising Practices and Its Effect On Product PerceptionDocument9 pagesCommunication Arts: Consumer Awareness of Advertising Practices and Its Effect On Product PerceptionChan Mae PlegoNo ratings yet

- 03 Cinnamon Ej Spring 14Document11 pages03 Cinnamon Ej Spring 14Bala ThandayuthamNo ratings yet

- Final Social Marketing and Entertainment Education StrategyDocument15 pagesFinal Social Marketing and Entertainment Education StrategyBiji ThottungalNo ratings yet

- Social Marketing: Concept and ApplicationDocument5 pagesSocial Marketing: Concept and ApplicationPriyanka SonawaneNo ratings yet

- Walker Effects of Sexualization in AdvertisementsDocument37 pagesWalker Effects of Sexualization in AdvertisementshardikgosaiNo ratings yet

- Seniorseminar PaperDocument36 pagesSeniorseminar Paperapi-302623055No ratings yet

- Englres Final Research Paper - Peswani and VillavicencioDocument23 pagesEnglres Final Research Paper - Peswani and VillavicencioNeel PeswaniNo ratings yet

- 07 Lefebvre CraigDocument14 pages07 Lefebvre CraigMuhammad Rizwan RizLgNo ratings yet

- Bournvita Li'l Champs: Right Place at The Right Time - A Touchpoint StudyDocument9 pagesBournvita Li'l Champs: Right Place at The Right Time - A Touchpoint StudyvidhisalianNo ratings yet

- UNIT 4 - Social MarketingDocument9 pagesUNIT 4 - Social MarketingSaurabhNo ratings yet

- Determining The Effect of Advertising Media On ChildrenDocument8 pagesDetermining The Effect of Advertising Media On ChildrenronnieBNo ratings yet

- What Is Social Marketing?Document5 pagesWhat Is Social Marketing?sachin161291No ratings yet

- Group 9 - PBM ProjectDocument15 pagesGroup 9 - PBM ProjectvibhorchaudharyNo ratings yet

- Running Head: No Bite, No Malaria:Inc Multifunctional MethodsDocument36 pagesRunning Head: No Bite, No Malaria:Inc Multifunctional MethodsLourdes Gomez de CordovaNo ratings yet

- The Impact of Television Advertisements On ConsumerDocument25 pagesThe Impact of Television Advertisements On Consumermichelle ann vinoyaNo ratings yet

- ThesisDocument20 pagesThesisElina PashaNo ratings yet

- Afsal M-C FinalDocument14 pagesAfsal M-C FinalJabir AngillathNo ratings yet

- The Impact of Television Advertisements On ConsumerDocument25 pagesThe Impact of Television Advertisements On ConsumerVickyNo ratings yet

- A Study On Impact of Advertisement and Promotion On Consumer Purchase DecisionDocument18 pagesA Study On Impact of Advertisement and Promotion On Consumer Purchase DecisionAnonymous CwJeBCAXpNo ratings yet

- Branding in Health MarketingDocument9 pagesBranding in Health MarketingPhá LấuNo ratings yet

- Asec Paulyn Jean B. Rosell-Ubial Department of HealthDocument20 pagesAsec Paulyn Jean B. Rosell-Ubial Department of HealthArianne A ZamoraNo ratings yet

- Impact of TV Commercial On Consumer BehaviourDocument91 pagesImpact of TV Commercial On Consumer BehaviourRitika Vohra Kathuria100% (4)

- Social Marketing 101: Carmel Pryor, Social Marketing Manager Isaiah Webster III, Director of Capacity BuildingDocument48 pagesSocial Marketing 101: Carmel Pryor, Social Marketing Manager Isaiah Webster III, Director of Capacity BuildingSankalp PurwarNo ratings yet

- I. A. Background of The StudyDocument9 pagesI. A. Background of The StudyJUARE MaxineNo ratings yet

- Obesity Reviews - 2022 - MC Carthy - The Influence of Unhealthy Food and Beverage Marketing Through Social Media andDocument21 pagesObesity Reviews - 2022 - MC Carthy - The Influence of Unhealthy Food and Beverage Marketing Through Social Media andsarahbening.2No ratings yet

- Unethical Advertising FinalDocument8 pagesUnethical Advertising FinalJohn CarpenterNo ratings yet

- Advertising: Advertising Is A Form ofDocument34 pagesAdvertising: Advertising Is A Form ofPrashant SinghNo ratings yet

- Storey 2008Document6 pagesStorey 2008Smitha4aNo ratings yet

- St. Joseph Academy of Valenzuela: Traditional Advertising vs. Modern AdvertisingDocument4 pagesSt. Joseph Academy of Valenzuela: Traditional Advertising vs. Modern AdvertisingcheNo ratings yet

- Unit XI: The: New 4p's of Pharmaceutical MarketingDocument36 pagesUnit XI: The: New 4p's of Pharmaceutical MarketingAhira Dawn D. MALIHOCNo ratings yet

- Social MarketingDocument26 pagesSocial MarketingchetanNo ratings yet

- Assessing The Role of Sex Appeal in Marketing CommunicationsDocument27 pagesAssessing The Role of Sex Appeal in Marketing CommunicationsCitizenNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1Document7 pagesChapter 1Rhosvic VargasNo ratings yet

- Advertising EthicsDocument26 pagesAdvertising EthicsManish SharmaNo ratings yet

- Weinreich WhatIsSocialMarketingDocument4 pagesWeinreich WhatIsSocialMarketingMery PratiwiNo ratings yet

- Social Media Marketing PlanDocument10 pagesSocial Media Marketing PlanDante DienNo ratings yet

- Influence of Advertisement On Consumer Behavior Project ProposalDocument6 pagesInfluence of Advertisement On Consumer Behavior Project ProposalFMTech ConsultsNo ratings yet

- The Role of Branding in PublicDocument16 pagesThe Role of Branding in PublicUsamah HussainNo ratings yet

- Practice 5Document3 pagesPractice 5abadiabea12No ratings yet

- The Impact of Advertising On Food Choice: The Social Context of AdvertisingDocument20 pagesThe Impact of Advertising On Food Choice: The Social Context of AdvertisingGagenel Andrei AlexandruNo ratings yet

- Social MarketingDocument19 pagesSocial MarketingdranshulitrivediNo ratings yet

- Strategy 8. Social MarketingDocument6 pagesStrategy 8. Social MarketingChristian TanNo ratings yet

- Social Media Planning For Hospitals: Vishwanand Govindraju (Aka Vishy)Document54 pagesSocial Media Planning For Hospitals: Vishwanand Govindraju (Aka Vishy)Rami MishlawiNo ratings yet

- Popularity of Radio Advertising On Food Supplement Among Senior CitizenDocument19 pagesPopularity of Radio Advertising On Food Supplement Among Senior CitizenJohn Patrick Tolosa NavarroNo ratings yet

- Manuscrip RES1BDocument19 pagesManuscrip RES1BJohn Patrick Tolosa NavarroNo ratings yet

- Popularity of Radio Advertising On Food Supplement Among Senior CitizenDocument19 pagesPopularity of Radio Advertising On Food Supplement Among Senior CitizenJohn Patrick Tolosa NavarroNo ratings yet

- Popularity of Radio Advertising On Food Supplement Among Senior CitizenDocument19 pagesPopularity of Radio Advertising On Food Supplement Among Senior CitizenJohn Patrick Tolosa NavarroNo ratings yet

- Activity 1 - Gualon, Carlo N.Document2 pagesActivity 1 - Gualon, Carlo N.Carlo GualonNo ratings yet

- Social MarketingDocument8 pagesSocial MarketingSidhu boiiNo ratings yet

- Developing An Effective Media Campaign StrategyDocument6 pagesDeveloping An Effective Media Campaign StrategyshkadryNo ratings yet

- Negative and Positive Effects of AdvertisingDocument5 pagesNegative and Positive Effects of AdvertisingNguyễn Đình Tuấn ĐạtNo ratings yet

- Thesis Work 2Document3 pagesThesis Work 2Maryam KhaliqNo ratings yet

- Social Marketing in Public HealthDocument24 pagesSocial Marketing in Public HealthYaadrahulkumar MoharanaNo ratings yet

- RM 1ST ASS LpuDocument8 pagesRM 1ST ASS Lpuhunny_luckyNo ratings yet

- Effective Discipline To Raise Healthy Children: Policy StatementDocument12 pagesEffective Discipline To Raise Healthy Children: Policy StatementJesse M. MassieNo ratings yet

- IJMEDocument7 pagesIJMEJesse M. MassieNo ratings yet

- Ongoing Pediatric Health Care For The Child Who Has Been MaltreatedDocument18 pagesOngoing Pediatric Health Care For The Child Who Has Been MaltreatedJesse M. MassieNo ratings yet

- Suidi Oklahoma ProviderDocument28 pagesSuidi Oklahoma ProviderJesse M. MassieNo ratings yet

- Oral and Dental Aspects of Child Abuse and Neglect: Clinical ReportDocument10 pagesOral and Dental Aspects of Child Abuse and Neglect: Clinical ReportJesse M. MassieNo ratings yet

- Making The Most of Mentors: A Guide For MenteesDocument5 pagesMaking The Most of Mentors: A Guide For MenteesJesse M. MassieNo ratings yet

- Jpeds Aom 208Document3 pagesJpeds Aom 208Jesse M. MassieNo ratings yet

- Status EpileticusDocument2 pagesStatus EpileticusJesse M. MassieNo ratings yet

- Identifying Child Abuse Fatalities During Infancy: Clinical ReportDocument11 pagesIdentifying Child Abuse Fatalities During Infancy: Clinical ReportJesse M. MassieNo ratings yet

- How Loud Is Too LoudDocument2 pagesHow Loud Is Too LoudJesse M. MassieNo ratings yet

- dBA PROTECT YOUR HEARINGDocument4 pagesdBA PROTECT YOUR HEARINGJesse M. MassieNo ratings yet

- Preventing Adverse Childhood Experiences (Aces) :: Leveraging The Best Available EvidenceDocument40 pagesPreventing Adverse Childhood Experiences (Aces) :: Leveraging The Best Available EvidenceJesse M. MassieNo ratings yet

- i-PASS OBSERVATION TOOLDocument1 pagei-PASS OBSERVATION TOOLJesse M. MassieNo ratings yet

- What Is Child Abuse and Neglect? Recognizing The Signs and SymptomsDocument8 pagesWhat Is Child Abuse and Neglect? Recognizing The Signs and SymptomsJesse M. MassieNo ratings yet

- Minority YouthDocument28 pagesMinority YouthJesse M. MassieNo ratings yet

- Advancing Health Equity: A Practitioner'S Guide ForDocument132 pagesAdvancing Health Equity: A Practitioner'S Guide ForJesse M. MassieNo ratings yet

- Cbig Cross-ReportingDocument25 pagesCbig Cross-ReportingJesse M. MassieNo ratings yet

- COVID Positive/PUI: PAPR Prioritization MatrixDocument1 pageCOVID Positive/PUI: PAPR Prioritization MatrixJesse M. MassieNo ratings yet

- Domestic Violence Oklahoma 2017Document44 pagesDomestic Violence Oklahoma 2017Jesse M. MassieNo ratings yet

- Male Victims of Intimate Partner Violence: Did You Know?Document3 pagesMale Victims of Intimate Partner Violence: Did You Know?Jesse M. MassieNo ratings yet

- Noisey PlanetDocument1 pageNoisey PlanetJesse M. MassieNo ratings yet

- Intimate Partner Violence, Sexual Violence, Stalking: Before The Age of 18Document1 pageIntimate Partner Violence, Sexual Violence, Stalking: Before The Age of 18Jesse M. MassieNo ratings yet

- Fireworks ShowDocument2 pagesFireworks ShowJesse M. MassieNo ratings yet

- Kinshipguardianship PDFDocument139 pagesKinshipguardianship PDFJesse M. MassieNo ratings yet

- Aap Food Insecurity Toolkit For ProvidersDocument39 pagesAap Food Insecurity Toolkit For ProvidersJesse M. MassieNo ratings yet

- How Does Noise Damage Your Hearing?Document2 pagesHow Does Noise Damage Your Hearing?Jesse M. MassieNo ratings yet

- Cbig Child Abuse and Neglect Fatalities 2017Document8 pagesCbig Child Abuse and Neglect Fatalities 2017Jesse M. MassieNo ratings yet

- CDC Capacity BuildingDocument16 pagesCDC Capacity BuildingJesse M. MassieNo ratings yet

- In Drinking Water: Sources of LEADDocument1 pageIn Drinking Water: Sources of LEADJesse M. MassieNo ratings yet

- Essentials For Childhood:: Steps To Create Safe, Stable, Nurturing Relationships and EnvironmentsDocument1 pageEssentials For Childhood:: Steps To Create Safe, Stable, Nurturing Relationships and EnvironmentsJesse M. MassieNo ratings yet

- Case Study - DiversityDocument2 pagesCase Study - Diversitychemeleo zapsNo ratings yet

- Homework Cheat Sims 4Document7 pagesHomework Cheat Sims 4afmtgbrgb100% (1)

- Budgeting pr2Document23 pagesBudgeting pr2Kenneth ParpanNo ratings yet

- Jurnal KesehatanDocument10 pagesJurnal KesehatanRiana UtamiNo ratings yet

- Protecting Children From The Consequences of Divorce: A Longitudinal Study of The Effects of Parenting On Children's Coping ProcessesDocument15 pagesProtecting Children From The Consequences of Divorce: A Longitudinal Study of The Effects of Parenting On Children's Coping ProcessesAndreea BălanNo ratings yet

- Psychology ReviewerDocument18 pagesPsychology ReviewerTiffany CaballeroNo ratings yet

- Adolescence HealthDocument27 pagesAdolescence HealthTalemaNo ratings yet

- English SBADocument9 pagesEnglish SBAdanielleNo ratings yet

- LN13 GIS1012 LifecycleNutrition 2019Document23 pagesLN13 GIS1012 LifecycleNutrition 2019Ed100% (1)

- 2009 Positive Discipline Part 6 en PDFDocument33 pages2009 Positive Discipline Part 6 en PDFJetfoxnai AbenidoNo ratings yet

- Ctet Central Teacher Eligibility Test Child Development and Pedagogy 2020 Paper I Ii Sandeep Kumar Full ChapterDocument51 pagesCtet Central Teacher Eligibility Test Child Development and Pedagogy 2020 Paper I Ii Sandeep Kumar Full Chapterenrique.harper808100% (9)

- Fuhs - Structure and State DevelopmentDocument52 pagesFuhs - Structure and State DevelopmentMichael Kruse Craig100% (1)

- Health 7 Activity SheetsDocument31 pagesHealth 7 Activity SheetsGABINO ELECTRONIC REPAIR & PRINTING SERVICESNo ratings yet

- Full Download PDF of (Ebook PDF) Child Development: A Cultural Approach 3rd Edition All ChapterDocument43 pagesFull Download PDF of (Ebook PDF) Child Development: A Cultural Approach 3rd Edition All Chapterakhiladesty28100% (5)

- 4h Vol 102 Understanding Boys GirlsDocument6 pages4h Vol 102 Understanding Boys GirlsPrincess Trisha De FelipeNo ratings yet

- Mass Media As A Toxic MirrorDocument7 pagesMass Media As A Toxic MirrorrdmdelarosaNo ratings yet

- Proposal Writing Example 1Document16 pagesProposal Writing Example 1Ayu NagisaNo ratings yet

- EAPP SurveyDocument3 pagesEAPP SurveySuzzayne ButengNo ratings yet

- Case Study: Plan: Penny Brough in BrazilDocument16 pagesCase Study: Plan: Penny Brough in BrazilThe International Exchange (aka TIE)No ratings yet

- Psychology - Key Concepts PDFDocument281 pagesPsychology - Key Concepts PDFSolly Seid100% (1)

- FINALCHAPTERSDocument40 pagesFINALCHAPTERSAlbert N CamachoNo ratings yet

- World Mental Health Day Lesson Plans PDFDocument8 pagesWorld Mental Health Day Lesson Plans PDFNaima BulandresNo ratings yet

- Northern Mindanao Colleges, Inc.: Self-Learning Module For Personal Development Quarter 1, Week 3Document8 pagesNorthern Mindanao Colleges, Inc.: Self-Learning Module For Personal Development Quarter 1, Week 3Christopher Nanz Lagura CustanNo ratings yet

- Evaluating The Effects of Stressors and Vices in Personal and Academic Performance of Senior High School in Liceo de La Salle BacolodDocument7 pagesEvaluating The Effects of Stressors and Vices in Personal and Academic Performance of Senior High School in Liceo de La Salle BacolodEscala, John KeithNo ratings yet

- The Positive Effects of A Particular Health-Related Law in Our SocietyDocument2 pagesThe Positive Effects of A Particular Health-Related Law in Our SocietyKyle OrlanesNo ratings yet

VERB Campaign

VERB Campaign

Uploaded by

Jesse M. MassieOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

VERB Campaign

VERB Campaign

Uploaded by

Jesse M. MassieCopyright:

Available Formats

Bringing Play to Life

The Use of Experiential Marketing in the VERB Campaign

Carrie D. Heitzler, MPH, Lori D. Asbury, BA, Stella L. Kusner, BA

Abstract: Given the abundance of advertising and media that children and adolescents are exposed

to today, it is increasingly important to incorporate nontraditional channels and venues in

strategies designed to reach them. One such channel that the CDCs VERB campaign

employed was experiential marketing, which is dened here as a live event or experience that

gives the target audience the opportunity to see a product and experience it for themselves. Experiential

marketing and the tactics that the VERB campaign used to reach children aged 913 years

(tweens) with health messages about physical activity are described, including a discussion

about how other public health campaigns might use experiential marketing and other

commercial marketing techniques to reach the public with public health messages.

(Am J Prev Med 2008;34(6S):S188S193) 2008 American Journal of Preventive Medicine

Introduction

C

hildren are exposed to an unprecedented

amount of marketing activities through an ever-

widening range of channels. In 2004, $15 billion

was spent on media-based advertising and other mar-

keting to children and young people.

1

Because young

consumers are inundated with advertising for every-

thing from breakfast cereals to the latest technologic

gadgets, breaking through the clutter to reach them

with any messages, especially health messages, is dif-

cult.

2

To overcome this difculty, the VERB cam-

paign used an innovative form of marketing called

experiential marketing. This article contains a brief expla-

nation of the concept of experiential marketing and

describes how the VERB campaign used experiential

marketing as one tactic to reach children aged 913

years (tweens) with messages about physical activity.

Various forms of experiential marketing that VERB

used to bring health messages to its target audience are

discussed and ways to evaluate experiential marketing

are suggested, concluding with a discussion about how

other public health professionals might embark on

health promotion and social marketing campaigns us-

ing experiential marketing techniques.

Experiential Marketing

During the past decade, major businesses and commer-

cial brands have shifted a large portion of their adver-

tising dollars away from traditional forms of advertising

(such as television and print) toward new, innovative

forms of marketing and advertising to reach and con-

nect with consumers, especially young consumers.

3

One innovative approach of marketing is experiential

marketing, which is dened here as a live event or

experience that gives the target audience the opportunity to see

a product and experience it for themselves.

3

The basis of

experiential marketing is that it occurs face-to-face

through a personal experience using the service or

product or through a demonstration. Cognitive psy-

chologists note that face-to-face interaction, because it

engages multiple senses, dramatically increases peo-

ples ability to absorb, remember, and apply learning.

4

The goal of experiential marketing is to tie a product or

campaign to an experience that is relevant to the target

audience, the premise being that letting people dis-

cover the characteristics of a product or service on their

own is more effective than having them see or hear

about it through a passive medium such as television or

radio. Experiential marketing includes tactics such as

giving out free product samples, offering free trial

periods, and organizing events and tours that allow

consumers to use the products or services being mar-

keted or to interact with representatives of the company

selling the product or service. The premise of experi-

ential marketing follows several theoretical principles

presented in the elds of communication, marketing,

and health behavior change, including the diffusion of

innovations

5

and social cognitive theories.

6

Research shows that adolescents who experience and

try new products or services have more positive beliefs

and attitudes about those products than do adolescents

exposed to the product only through traditional adver-

tising.

7

According to a survey by Jack Morton World-

wide,

8

experiential marketing has a greater effect on

adolescents than do advertisements on television or the

From the School of Public Health, University of Minnesota (Heit-

zler), Minneapolis, Minnesota; and Frankel, an Arc Worldwide Com-

pany (Asbury, Kusner), Chicago, Illinois

Address correspondence and reprint requests to: Carrie D. Heit-

zler, MPH, School of Public Health, University of Minnesota, 1300 S.

Second Street, Suite 300, Minneapolis MN 55410. E-mail:

heitz022@umn.edu.

S188 Am J Prev Med 2008;34(6S) 0749-3797/08/$see front matter

2008 American Journal of Preventive Medicine Published by Elsevier Inc. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2008.03.009

Internet. According to this survey, the most important

factors in making a live marketing event interesting to

adolescents are the opportunity to test or try out a

product or service, an on-site representative to tell

them about the product or service, and free samples

and information on the product or service.

8

The VERB Campaigns Strategy

The goal of the VERB campaign was to increase physi-

cal activity among tweens.

9

To reach tweens with the

message, a surround strategy was chosen. That is, VERB

and its messages were made visible through multiple

channels by bringing campaign messages to the chil-

dren at home, in school, and throughout the commu-

nity. VERB had the challenge of establishing and

building its own brand

10

and applying the principles of

commercial marketing to a public health issue. To help

us with this task, leading advertising agencies were

hired.

9

For optimal results, the campaigns planners chose to

combine two strategies: (1) marketing tactics designed

to reach large audiences with little personal involve-

ment by the target audience (e.g., broadcast advertising

on radio and television) and (2) tactics designed to

reach smaller audiences but with high personal involve-

ment by the target audience (e.g., participating in

community fairs and sponsored events). Experiential

marketing tactics were just one component of the

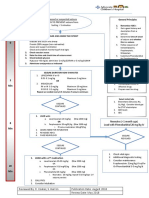

multi-component VERB campaign (Table 1). During

each phase of the campaign, a variety of strategies were

used to convey a common theme or concept. For

instance, in Phase 3 of the campaign (June 2004July

2005), the theme was that physical activities could be

done anywhere and anyhow, and children were encour-

aged with slogans such as play by your own rules. Accord-

ingly, all of campaign components implemented dur-

ing this phaseincluding the experiential marketing

methodsfollowed this same theme.

Although the goal of the VERB campaign was to

increase regular participation in physical activity by

tweens,

9

the essence of the messages and tactics high-

lighted the notion of play and were exemplied by the

types of activities and situations that were depicted

throughout the campaign. Rather than giving tweens

educational messages about the recommended levels of

moderate-to-vigorous physical activity, VERB focused

on getting them to play in their own backyards, in

neighborhood parks, or with their after-school pro-

grams. This notion of play was brought to life through

experiential marketing tactics.

Environments were created where tweens could in-

teract with VERB and play in new and engaging ways.

The purpose was to have a direct effect on tweens in

their own communities by allowing them hands-on,

lasting, enjoyable experiences related to physical activ-

ity. The major goals of the experiential marketing

tactics were to (1) augment VERBs national media

campaign by reinforcing the VERB messages, (2) pro-

vide trial opportunities for tweens to be physically

active, (3) provide on-site incentives or rewards for

participating in physical activities, and (4) raise aware-

ness of local opportunities for children to be physically

active.

The secondary goal of experiential marketing was to

create intrigue among tweens by creating buzz about

VERB. That is, word-of-mouth communication was gen-

erated within the target audience, with the hope that

this would lead to changes in the social norms related

to children being physically active. In many cases, these

strategies also allowed the information about VERB to

reach tweens and their parents simultaneously and to

involve local partners (e.g., state health departments,

sporting goods stores, skating rinks) in the VERB

campaign.

Launching a new brandespecially one that calls for

health-related behavior changeis a distinct marketing

challenge. To make tweens aware of VERB and to

create afnity for VERB, the campaign purposefully

aligned itself with the brands and media outlets most

appealing to tweens. As found in formative research, it

was important to link VERB with experiences that

Table 1. Components of the VERB Campaign

Component Description

Paid and unpaid advertising Purchased and donated advertising on television, on radio, and in print

Websites Websites designed for specic VERB audiences:

Tween: www.VERBnow.com

Parents: www.VERBparents.com

Partners and stakeholders: www.cdc.gov/VERB

Experiential marketing Tactics such as event sponsorship, mobile marketing, guerilla marketing, and promotions

in schools and communities

Contests and sweepstakes Individual and group competitions to encourage participation in physical activity

Community partnerships Collaborations with organizations across the country to increase opportunities for tweens

to be physically active and to reach parents and other inuencers of tweens

Corporate partnerships Collaboration with corporations to extend the reach and appeal of the campaign to tweens

Public relations Communication with news media, stakeholders, and partner organizations to highlight the

importance of physical activity for young people and to spotlight campaign activities

June 2008 Am J Prev Med 2008;34(6S) S189

tweens respected and considered cool.

11

With that in

mind, a partnership was developed with popular media

outlets (e.g., Nickelodeon); athletes (e.g., Venus Wil-

liams); and musicians (e.g., Bow Wow). Some of

VERBs major partners were the National Recreation

and Park Association, National Hockey League, Wom-

ens National Basketball Association, National Football

League, Womens Tennis Association, Six Flags, Wil-

son, ESPN Play Your Way, and Coop Active Sports.

Examples of VERBs Experiential Marketing Tactics

Event Sponsorship

Throughout the campaign, VERB served as the main

sponsor or co-sponsor of a variety of tween-centered

events across the country. The primary purpose of

sponsoring events was (1) to leverage the afnity that

tweens have with particular brands, sports, and celebri-

ties to gain immediate credibility; and (2) to provide

opportunities for the tweens to interact with VERB and

to try various types of activities. Several events also gave

tweens and their families the chance to learn more

about and register for local programs or venues where

the children could be physically active.

At many events that VERB sponsored, an area called

the Activity Zone was set up, where children and

adolescents could participate in a variety of activities

such as rock climbing, basketball, soccer, dancing, and

interactive video games that required children to move

(e.g., Dance Dance Revolution, GameBike). The Activ-

ity Zone allowed tweens to try activities and be re-

warded for participating with VERB-branded prizes

(e.g., wristbands, t-shirts, Frisbees

). Several events also

featured live performances by celebrities and instruc-

tional clinics with well-known athletes.

Examples of events sponsored or co-sponsored by

VERB are the 20022003 Nickelodeon Wild & Crazy

Kids (WACK) tour, the 2004 Sports Illustrated for Kids

No Limits Road Trip tour, and the AND 1 Mixtape

Tour in 2004. In addition, VERB cosponsored local

cultural events such as the Harvest Moon Festival in Los

Angeles; Youth Day Powwow in Black Hills, South

Dakota; and the Calle Ocho Street Festival in Miami.

The audience and reach of each event varied. For

example, through the Nickelodeon WACK tour, over

14,000 tweens were reached during nine events.

Guerilla and Mobile Marketing

Mobile and guerilla marketing involves going directly

to target consumers to interact with them face-to-face in

a spontaneous and short-term encounter. In VERBs

case, mobile marketing meant going to popular hang-

outs such as malls and parks and attending community

events such as minor league baseball games, parades,

and fairs. Guerrilla marketing consists of unconven-

tional ways of performing promotional activities with

minimal resources.

12

At times, such approaches are

designed so that many in the target audience are

unaware that something is being marketed to them. It

allows marketers to react quickly to local conditions

and recast marketing strategies as needed. One such

tactic uses local ambassadors to engage target con-

sumers in an experience that combines an opportunity

for consumers to use a product or service with an

opportunity for the marketer to talk with the consumer

directly about that product or service.

The VERB campaign adapted these techniques to a

public health use. Street teams were deployed to dis-

seminate the VERB campaigns messages directly from

VERB ambassadors to tweens, especially inuential

tweens (i.e., tweens who are likely to inuence other

tweens). Street teams typically are composed of cool,

high-energy, young men and women of various racial

groups. Such ambassadors were identied and hired

through companies that specialize in youth and expe-

riential marketing such as Mr. Youth (www.mryouth.

com) and Marketing Werks (www.marketing-werks.com).

Recruitment occurred through open casting calls, recruit-

ment websites, and job fairs for event marketing. Criteria

for hiring included ethnic diversity, an outgoing person-

ality, unique sport and performance skills (e.g., break

dancing, bucket drumming, juggling), an established

network of friends and peers, and an overall ability to

connect with youth. The ambassadors became the face

of the campaign, interacting with tweens at events and

tours, leading the mobile marketing efforts, and increas-

ing the buzz about VERB through traditional and online

channels.

An example of mobile marketing, VERBs national

mobile tourthe VERB Anytourwas launched in

June 2004. Six custom trucks, with colorful designs on

them, toured the nation, reaching children at amuse-

ment parks, summer camps, community organizations,

and events such as the Gravity Games. Figure 1 is a

graphic of the Anytour mobile truck. The trucks

remained in each market for about 1 week at a time.

Between June and October 2004 the tour visited close

to 500 events and reached more than 840,000 tweens.

After a short break, the tour started its second leg in

February 2005 and traveled until the end of May 2005.

The second leg visited about 455 locations and inter-

acted with more than 300,000 tweens. The tour used

the theme Anytime Anywhere featured in VERBs na-

tional advertising. Its purpose was to let children know

they could engage in a variety of activities anytime and

anywhere. The message was that physical activity does

not always require structure and expensive equipment

and that children can even invent their own games. For

example, during the mobile tour, children tried using a

garbage can as a hoop to play basketball and broom-

sticks to play hockey. The tour was high-energy and

encouraged all children, regardless of their skills and

abilities, to take part. During the tour, staff handed out

S190 American Journal of Preventive Medicine, Volume 34, Number 6S www.ajpm-online.net

VERB-branded prizes such as Frisbees

, foot bags, and

popular rubber wrist bracelets. Most incentives were

physical activity gear that encouraged active play both

at and beyond the event.

Another example of VERBs mobile and guerrilla

marketing tacticsVERB Yellowballwas launched in

November 2005. During this nal phase of the cam-

paign, all campaign componentsincluding the paid

advertisements, school- and community-based pro-

grams, and the mobile tourused the theme Yellow-

ball. The idea was to use yellow rubber balls to spread

play from tween-to-tween across the nation. VERB

distributed more than 500,000 yellow balls to tweens

through a variety of channels and asked those tweens to

join in and help create a movement of play. The cam-

paign informed tweens that by playing with the yellow

ball, telling their story on the VERBs website, and

passing that ball on to another tween, they could

directly affect all childrens participation in play. This

peer-to-peer program allows tweens to advocate for play

directly, resulting in a relevant and authentic experi-

ence that happens with their own friends and

acquaintances.

The Yellowball program began with a 4-month, word-

of-mouth campaign. A total or 812 youth, aged 13 to 16,

were recruited through online questionnaires placed

on social networking websites such as www.myspace-

.com to become active members of Team VERB Yellow-

ball. Questionnaires assessed the youths self-reported

friend and peer networks, their use of online chatting

and blogging sites, and their outgoingness. Each mem-

ber received one VERB Yellowball kit (t-shirt, 5 yellow

balls, and instructions) and became an ambassador of

VERB Yellowball to their friends, at their school,

and/or in their community. During this rst effort,

members were asked to get active with their peers and

to document each mission online with photos, videos,

and blogs on www.VERBnow.com. In addition, two

separate Yellowball mobile and guerilla tours used

trained brand ambassadors to travel across the country

and create a word-of-mouth network. During these

tours, close to 200,000 yellow balls were distributed and

the teams reached over 750,000 tweens. Figure 2 shows

an example a Yellowball truck at a community event.

Promotions in Schools and Communities

In addition to event sponsorship and mobile and

guerrilla marketing, VERB developed and disseminated

several promotions in schools and communities nation-

wide. Most of these involved distributing a turn-key kit,

which contained all the materials necessary for children

aged 913 years to have a fun and entertaining expe-

rience being physically active. Kits were distributed at

no cost to schools and community organizations

through a variety of channels, including the VERB

website (www.cdc.gov/VERB) and vendors with estab-

lished networks for reaching teachers with tween stu-

dents. The purpose of these school and community

promotions was to show students everyday opportuni-

ties to be active where they are. Physical education and

homeroom teachers were provided with the tools to

interest their students creatively with new ways to play.

All of the promotions were designed for a short period,

generally from 2 to 6 weeks. Changing promotions

frequently was especially important for the school-

based promotions in order to keep the activities and

messages fresh and appealing to tweens.

An example of a school promotion was VERBs

3-week Crossover program, which was implemented in

2005 for students in grades 48 and designed to

increase the number of hours children spent in physi-

cal activity before and after school. The idea of Cross-

over was to combine basketball with another sport,

activity, or piece of equipment associated with another

sport to create fun, new games. For instance, the game

End Zone Hoops could be made up combining

Figure 1. VERB Anytour mobile tour truck.

Figure 2. Example of a VERB Yellowball truck and event.

June 2008 Am J Prev Med 2008;34(6S) S191

basketball and football. The program kit included a

teacher guide, educator letter, parent letters, two post-

ers, a dry-erase laminated poster to record competition

results, award certicates, and an interactive game

wheel that suggested games to combine and play at

home. The kit also contained prizes such as terrycloth

wristbands and inatable vinyl basketballs; each student

received a rubber band bracelet. The Crossover pro-

gram was distributed to over 2000 schools.

Reactions of the Target Audience

For the VERB campaign, several methods were used to

get immediate feedback on the process of the interven-

tion (i.e., how well the events and other tactics were

being carried out as planned and how well the target

audience was responding). The primary method was

through on-site observation. For this, a member of the

VERB team traveled to one of the planned mobile truck

stops or to a sponsored event and observed what

happened. Each specic event or tour was observed at

least once throughout the course of the campaign. In

most cases, the staff member was unknown to the team

of people organizing the promotion on site. In some

instances the observation process was formal and sys-

tematic, meaning that the observer had a specic

protocol to follow, and in other cases the observations

were less formal and observers simply watched what was

happening for 2 to 4 hours and wrote a summary. The

observation protocols were developed specically for

each tactic and were tailored to capture important

aspects pertaining to that specic event and/or venue.

In addition to on-site observations, intercept inter-

views were also conducted during events. During the

intercept interviews, staff engaged tweens in a brief

conversation, gauging their satisfaction with the event,

including their likes and dislikes. Generally, tweens

responded positively about their interactions with all

VERB activities and events. Experiences that allowed

tweens to try a variety of physical activities and interact

with their peers seemed to be the most popular. Tweens

generally seemed excited to continue playing with the

active VERB giveaways (e.g., foot bags, Frisbees

) upon

leaving the events.

Conclusion

No single mediumtelevision, print, Internet, or any-

thing elseis sufcient to communicate with children

and adolescents, especially considering the multi-

tasking lifestyle so many of them lead.

13

It is imperative

to get the right mix of marketing tactics when trying to

communicate with them, especially with health mes-

sages that might otherwise get lost in the barrage of

commercial advertisements. Experiential marketing is

not a substitute for broadcast and print advertising;

rather, it is a powerful partner. By focusing on the

events and activities that young people care about, and

by reaching them at a time when they are receptive to

new ideas, public health professionals can create rela-

tionships that cultivate emotional attachment to a

brand or a health message. We believe that public

health campaigns that show success will be those that

understand how to integrate experiential marketing as

a complementary tactic to more traditional forms of

advertising and direct marketing. As new tactics in

commercial marketing emerge and show success,

health professionals and social marketers can learn

from them and adopt similar strategies for health

promotion campaigns, particularly campaigns targeted

to children and adolescents. By using a variety of

marketing channels, both traditional and nontradi-

tional, public health professionals can create opportu-

nities for young people to experience (rather than pas-

sively hear about) the benets of the behavior that

public health is promoting.

Experiential marketing tactics, as designed, typically

reach fewer people and often carry a higher cost per

person ratio compared to traditional mass-media ef-

forts. However, we believe that the intensity and depth

by which these tactics can convey a campaigns mes-

sages and encourage trial behaviors is extremely valu-

able in the behavior change process. In addition, the

suspected buzz that these tactics can create can help

extend reach beyond direct exposure at events. In an

environment of limited resources it is important for

each program to critically evaluate the potential effects

of using strategies designed to reach large audiences

that have little personal involvement by the target

audience (e.g., mass communication) with those de-

signed to reach smaller audiences but with high per-

sonal involvement by the target audience. We speculate

that experiential marketing can be effectively used in a

wide range of public health programsfrom large-

scale, national campaigns to those with modest re-

sources in smaller, dened communities.

The VERB campaign set out not simply to inform,

but to create experiences that extended the positive

messages of play. We believe that a combination of all

of the marketing tacticstraditional and nontradition-

alallowed the VERB campaign to be a real success.

14

The addition of experiential marketing tactics achieved

what broadcast media could probably not achieve alone

and helped children to experience physical activity in a

fun and rewarding way.

Work for this paper was completed while Ms. Heitzler and Ms.

Asbury were employees of the CDC, Atlanta, Georgia.

The ndings and conclusions in this paper are those of the

authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the

CDC.

S192 American Journal of Preventive Medicine, Volume 34, Number 6S www.ajpm-online.net

No nancial disclosures were reported by the authors of

this paper.

References

1. Schor JB. Born to buy: the commercialized child and the new consumer

culture. New York: Scribner, 2004.

2. Randolph W, Viswanath K. Lessons learned from public health mass media

campaigns: marketing health in a crowded media world. Annu Rev Public

Health 2004;25:41937.

3. Schmitt BH. Experiential marketing: how to get customers to sense, feel,

think, act, relate to your company and brands. New York: Free Press, 1999.

4. Eysenck M. Fundamentals of cognition. New York: Psychology Press, 2006.

5. Rogers EM. Diffusion of innovations. New York: Free Press, 1995.

6. Bandura A. Social cognitive theory: an agentic perspective. Annu Rev

Psychol 2001;52:126.

7. Moore ES, Lutz RJ. Children, advertising, and product experiences: a

multimethod inquiry. J Consum Res 2000;27:3147.

8. Bigham L. Experiential marketing: a consumer survey. New York: Jack

Morton Worldwide, 2005. Available at: www.jackmorton.com/us/philoso-

phy/whitePaper.asp.

9. Wong F, Huhman M, Heitzler C, et al. VERB: a social marketing

campaign to increase physical activity among youth. Prev Chron Dis. [serial

online] 2004 Jul. Available at: www.cdc.gov/pcd/issues/2004/jul/

04_0043.htm.

10. Asbury LD, Wong FL, Price S, Nolin MJ. The VERB campaign: applying

a branding strategy in public health. Am J Prev Med 2008;34(6S):S183

S187.

11. Formative Research Reports. Executive summaries for brand development.

Available at: www.cdc.gov/YouthCampaign/research/resources.

12. Levinson J, Godin S. The guerrilla marketing handbook. New York:

Houghton Mifin, 1994.

13. Roberts DF, Foehr UG, Rideout V. Generation M: media in the lives of

818 year olds. Menlo Park CA: Kaiser Family Foundation, 2005.

14. Huhman ME, Potter LD, Duke JC, Judkins DR, Heitzler CD, Wong FL.

Evaluation of a national physical activity intervention for children: the

VERB campaign 20022004. Am J Prev Med 2007;32:3843.

Did you know?

You can track the impact of your article with citation alerts that let you know when your

article (or any article youd like to track) has been cited by another Elsevier-published

journal.

Visit www.ajpm-online.net today to see what else is new online!

June 2008 Am J Prev Med 2008;34(6S) S193

You might also like

- Test Bank For Womens Gynecologic Health 3rd Edition SchuilingDocument4 pagesTest Bank For Womens Gynecologic Health 3rd Edition SchuilingMichael Pupo33% (9)

- Textbook Discovering The Lifespan Feldman Ebook All Chapter PDFDocument53 pagesTextbook Discovering The Lifespan Feldman Ebook All Chapter PDFethel.maedche320100% (13)

- The Effects of Social Media On Mental Health of Selected Senior High School StudentsDocument26 pagesThe Effects of Social Media On Mental Health of Selected Senior High School StudentsJeandra Villanueva87% (39)

- Social Marketing TheoryDocument4 pagesSocial Marketing TheorySintija92% (13)

- CONQUEST OF THE SERPENT-A Way To Solve The Sex ProblemDocument55 pagesCONQUEST OF THE SERPENT-A Way To Solve The Sex ProblemPrecisionetica100% (1)

- Introduction To Child Development PDFDocument18 pagesIntroduction To Child Development PDFVAISHNAVINo ratings yet

- Media and Social Marketing: League International Photo by Margo Geist, Courtesy of La LecheDocument4 pagesMedia and Social Marketing: League International Photo by Margo Geist, Courtesy of La LecheNOVA LESLIE AGAPAYNo ratings yet

- Social Marketing PRJCTDocument19 pagesSocial Marketing PRJCTanishuNo ratings yet

- How Social Marketing Works in Health CareDocument8 pagesHow Social Marketing Works in Health CareMuhammad Shafiq GulNo ratings yet

- PNABL671 Healthcom MethodologyDocument8 pagesPNABL671 Healthcom MethodologyMuhammad Ikhsan AmarNo ratings yet

- Communication Arts: Consumer Awareness of Advertising Practices and Its Effect On Product PerceptionDocument9 pagesCommunication Arts: Consumer Awareness of Advertising Practices and Its Effect On Product PerceptionChan Mae PlegoNo ratings yet

- 03 Cinnamon Ej Spring 14Document11 pages03 Cinnamon Ej Spring 14Bala ThandayuthamNo ratings yet

- Final Social Marketing and Entertainment Education StrategyDocument15 pagesFinal Social Marketing and Entertainment Education StrategyBiji ThottungalNo ratings yet

- Social Marketing: Concept and ApplicationDocument5 pagesSocial Marketing: Concept and ApplicationPriyanka SonawaneNo ratings yet

- Walker Effects of Sexualization in AdvertisementsDocument37 pagesWalker Effects of Sexualization in AdvertisementshardikgosaiNo ratings yet

- Seniorseminar PaperDocument36 pagesSeniorseminar Paperapi-302623055No ratings yet

- Englres Final Research Paper - Peswani and VillavicencioDocument23 pagesEnglres Final Research Paper - Peswani and VillavicencioNeel PeswaniNo ratings yet

- 07 Lefebvre CraigDocument14 pages07 Lefebvre CraigMuhammad Rizwan RizLgNo ratings yet

- Bournvita Li'l Champs: Right Place at The Right Time - A Touchpoint StudyDocument9 pagesBournvita Li'l Champs: Right Place at The Right Time - A Touchpoint StudyvidhisalianNo ratings yet

- UNIT 4 - Social MarketingDocument9 pagesUNIT 4 - Social MarketingSaurabhNo ratings yet

- Determining The Effect of Advertising Media On ChildrenDocument8 pagesDetermining The Effect of Advertising Media On ChildrenronnieBNo ratings yet

- What Is Social Marketing?Document5 pagesWhat Is Social Marketing?sachin161291No ratings yet

- Group 9 - PBM ProjectDocument15 pagesGroup 9 - PBM ProjectvibhorchaudharyNo ratings yet

- Running Head: No Bite, No Malaria:Inc Multifunctional MethodsDocument36 pagesRunning Head: No Bite, No Malaria:Inc Multifunctional MethodsLourdes Gomez de CordovaNo ratings yet

- The Impact of Television Advertisements On ConsumerDocument25 pagesThe Impact of Television Advertisements On Consumermichelle ann vinoyaNo ratings yet

- ThesisDocument20 pagesThesisElina PashaNo ratings yet

- Afsal M-C FinalDocument14 pagesAfsal M-C FinalJabir AngillathNo ratings yet

- The Impact of Television Advertisements On ConsumerDocument25 pagesThe Impact of Television Advertisements On ConsumerVickyNo ratings yet

- A Study On Impact of Advertisement and Promotion On Consumer Purchase DecisionDocument18 pagesA Study On Impact of Advertisement and Promotion On Consumer Purchase DecisionAnonymous CwJeBCAXpNo ratings yet

- Branding in Health MarketingDocument9 pagesBranding in Health MarketingPhá LấuNo ratings yet

- Asec Paulyn Jean B. Rosell-Ubial Department of HealthDocument20 pagesAsec Paulyn Jean B. Rosell-Ubial Department of HealthArianne A ZamoraNo ratings yet

- Impact of TV Commercial On Consumer BehaviourDocument91 pagesImpact of TV Commercial On Consumer BehaviourRitika Vohra Kathuria100% (4)

- Social Marketing 101: Carmel Pryor, Social Marketing Manager Isaiah Webster III, Director of Capacity BuildingDocument48 pagesSocial Marketing 101: Carmel Pryor, Social Marketing Manager Isaiah Webster III, Director of Capacity BuildingSankalp PurwarNo ratings yet

- I. A. Background of The StudyDocument9 pagesI. A. Background of The StudyJUARE MaxineNo ratings yet

- Obesity Reviews - 2022 - MC Carthy - The Influence of Unhealthy Food and Beverage Marketing Through Social Media andDocument21 pagesObesity Reviews - 2022 - MC Carthy - The Influence of Unhealthy Food and Beverage Marketing Through Social Media andsarahbening.2No ratings yet

- Unethical Advertising FinalDocument8 pagesUnethical Advertising FinalJohn CarpenterNo ratings yet

- Advertising: Advertising Is A Form ofDocument34 pagesAdvertising: Advertising Is A Form ofPrashant SinghNo ratings yet

- Storey 2008Document6 pagesStorey 2008Smitha4aNo ratings yet

- St. Joseph Academy of Valenzuela: Traditional Advertising vs. Modern AdvertisingDocument4 pagesSt. Joseph Academy of Valenzuela: Traditional Advertising vs. Modern AdvertisingcheNo ratings yet

- Unit XI: The: New 4p's of Pharmaceutical MarketingDocument36 pagesUnit XI: The: New 4p's of Pharmaceutical MarketingAhira Dawn D. MALIHOCNo ratings yet

- Social MarketingDocument26 pagesSocial MarketingchetanNo ratings yet

- Assessing The Role of Sex Appeal in Marketing CommunicationsDocument27 pagesAssessing The Role of Sex Appeal in Marketing CommunicationsCitizenNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1Document7 pagesChapter 1Rhosvic VargasNo ratings yet

- Advertising EthicsDocument26 pagesAdvertising EthicsManish SharmaNo ratings yet

- Weinreich WhatIsSocialMarketingDocument4 pagesWeinreich WhatIsSocialMarketingMery PratiwiNo ratings yet

- Social Media Marketing PlanDocument10 pagesSocial Media Marketing PlanDante DienNo ratings yet

- Influence of Advertisement On Consumer Behavior Project ProposalDocument6 pagesInfluence of Advertisement On Consumer Behavior Project ProposalFMTech ConsultsNo ratings yet

- The Role of Branding in PublicDocument16 pagesThe Role of Branding in PublicUsamah HussainNo ratings yet

- Practice 5Document3 pagesPractice 5abadiabea12No ratings yet

- The Impact of Advertising On Food Choice: The Social Context of AdvertisingDocument20 pagesThe Impact of Advertising On Food Choice: The Social Context of AdvertisingGagenel Andrei AlexandruNo ratings yet

- Social MarketingDocument19 pagesSocial MarketingdranshulitrivediNo ratings yet

- Strategy 8. Social MarketingDocument6 pagesStrategy 8. Social MarketingChristian TanNo ratings yet

- Social Media Planning For Hospitals: Vishwanand Govindraju (Aka Vishy)Document54 pagesSocial Media Planning For Hospitals: Vishwanand Govindraju (Aka Vishy)Rami MishlawiNo ratings yet

- Popularity of Radio Advertising On Food Supplement Among Senior CitizenDocument19 pagesPopularity of Radio Advertising On Food Supplement Among Senior CitizenJohn Patrick Tolosa NavarroNo ratings yet

- Manuscrip RES1BDocument19 pagesManuscrip RES1BJohn Patrick Tolosa NavarroNo ratings yet

- Popularity of Radio Advertising On Food Supplement Among Senior CitizenDocument19 pagesPopularity of Radio Advertising On Food Supplement Among Senior CitizenJohn Patrick Tolosa NavarroNo ratings yet

- Popularity of Radio Advertising On Food Supplement Among Senior CitizenDocument19 pagesPopularity of Radio Advertising On Food Supplement Among Senior CitizenJohn Patrick Tolosa NavarroNo ratings yet

- Activity 1 - Gualon, Carlo N.Document2 pagesActivity 1 - Gualon, Carlo N.Carlo GualonNo ratings yet

- Social MarketingDocument8 pagesSocial MarketingSidhu boiiNo ratings yet

- Developing An Effective Media Campaign StrategyDocument6 pagesDeveloping An Effective Media Campaign StrategyshkadryNo ratings yet

- Negative and Positive Effects of AdvertisingDocument5 pagesNegative and Positive Effects of AdvertisingNguyễn Đình Tuấn ĐạtNo ratings yet

- Thesis Work 2Document3 pagesThesis Work 2Maryam KhaliqNo ratings yet

- Social Marketing in Public HealthDocument24 pagesSocial Marketing in Public HealthYaadrahulkumar MoharanaNo ratings yet

- RM 1ST ASS LpuDocument8 pagesRM 1ST ASS Lpuhunny_luckyNo ratings yet

- Effective Discipline To Raise Healthy Children: Policy StatementDocument12 pagesEffective Discipline To Raise Healthy Children: Policy StatementJesse M. MassieNo ratings yet

- IJMEDocument7 pagesIJMEJesse M. MassieNo ratings yet

- Ongoing Pediatric Health Care For The Child Who Has Been MaltreatedDocument18 pagesOngoing Pediatric Health Care For The Child Who Has Been MaltreatedJesse M. MassieNo ratings yet

- Suidi Oklahoma ProviderDocument28 pagesSuidi Oklahoma ProviderJesse M. MassieNo ratings yet

- Oral and Dental Aspects of Child Abuse and Neglect: Clinical ReportDocument10 pagesOral and Dental Aspects of Child Abuse and Neglect: Clinical ReportJesse M. MassieNo ratings yet

- Making The Most of Mentors: A Guide For MenteesDocument5 pagesMaking The Most of Mentors: A Guide For MenteesJesse M. MassieNo ratings yet

- Jpeds Aom 208Document3 pagesJpeds Aom 208Jesse M. MassieNo ratings yet

- Status EpileticusDocument2 pagesStatus EpileticusJesse M. MassieNo ratings yet

- Identifying Child Abuse Fatalities During Infancy: Clinical ReportDocument11 pagesIdentifying Child Abuse Fatalities During Infancy: Clinical ReportJesse M. MassieNo ratings yet

- How Loud Is Too LoudDocument2 pagesHow Loud Is Too LoudJesse M. MassieNo ratings yet

- dBA PROTECT YOUR HEARINGDocument4 pagesdBA PROTECT YOUR HEARINGJesse M. MassieNo ratings yet

- Preventing Adverse Childhood Experiences (Aces) :: Leveraging The Best Available EvidenceDocument40 pagesPreventing Adverse Childhood Experiences (Aces) :: Leveraging The Best Available EvidenceJesse M. MassieNo ratings yet

- i-PASS OBSERVATION TOOLDocument1 pagei-PASS OBSERVATION TOOLJesse M. MassieNo ratings yet

- What Is Child Abuse and Neglect? Recognizing The Signs and SymptomsDocument8 pagesWhat Is Child Abuse and Neglect? Recognizing The Signs and SymptomsJesse M. MassieNo ratings yet

- Minority YouthDocument28 pagesMinority YouthJesse M. MassieNo ratings yet

- Advancing Health Equity: A Practitioner'S Guide ForDocument132 pagesAdvancing Health Equity: A Practitioner'S Guide ForJesse M. MassieNo ratings yet

- Cbig Cross-ReportingDocument25 pagesCbig Cross-ReportingJesse M. MassieNo ratings yet

- COVID Positive/PUI: PAPR Prioritization MatrixDocument1 pageCOVID Positive/PUI: PAPR Prioritization MatrixJesse M. MassieNo ratings yet

- Domestic Violence Oklahoma 2017Document44 pagesDomestic Violence Oklahoma 2017Jesse M. MassieNo ratings yet

- Male Victims of Intimate Partner Violence: Did You Know?Document3 pagesMale Victims of Intimate Partner Violence: Did You Know?Jesse M. MassieNo ratings yet

- Noisey PlanetDocument1 pageNoisey PlanetJesse M. MassieNo ratings yet

- Intimate Partner Violence, Sexual Violence, Stalking: Before The Age of 18Document1 pageIntimate Partner Violence, Sexual Violence, Stalking: Before The Age of 18Jesse M. MassieNo ratings yet

- Fireworks ShowDocument2 pagesFireworks ShowJesse M. MassieNo ratings yet

- Kinshipguardianship PDFDocument139 pagesKinshipguardianship PDFJesse M. MassieNo ratings yet

- Aap Food Insecurity Toolkit For ProvidersDocument39 pagesAap Food Insecurity Toolkit For ProvidersJesse M. MassieNo ratings yet

- How Does Noise Damage Your Hearing?Document2 pagesHow Does Noise Damage Your Hearing?Jesse M. MassieNo ratings yet

- Cbig Child Abuse and Neglect Fatalities 2017Document8 pagesCbig Child Abuse and Neglect Fatalities 2017Jesse M. MassieNo ratings yet

- CDC Capacity BuildingDocument16 pagesCDC Capacity BuildingJesse M. MassieNo ratings yet

- In Drinking Water: Sources of LEADDocument1 pageIn Drinking Water: Sources of LEADJesse M. MassieNo ratings yet

- Essentials For Childhood:: Steps To Create Safe, Stable, Nurturing Relationships and EnvironmentsDocument1 pageEssentials For Childhood:: Steps To Create Safe, Stable, Nurturing Relationships and EnvironmentsJesse M. MassieNo ratings yet

- Case Study - DiversityDocument2 pagesCase Study - Diversitychemeleo zapsNo ratings yet

- Homework Cheat Sims 4Document7 pagesHomework Cheat Sims 4afmtgbrgb100% (1)

- Budgeting pr2Document23 pagesBudgeting pr2Kenneth ParpanNo ratings yet

- Jurnal KesehatanDocument10 pagesJurnal KesehatanRiana UtamiNo ratings yet

- Protecting Children From The Consequences of Divorce: A Longitudinal Study of The Effects of Parenting On Children's Coping ProcessesDocument15 pagesProtecting Children From The Consequences of Divorce: A Longitudinal Study of The Effects of Parenting On Children's Coping ProcessesAndreea BălanNo ratings yet

- Psychology ReviewerDocument18 pagesPsychology ReviewerTiffany CaballeroNo ratings yet

- Adolescence HealthDocument27 pagesAdolescence HealthTalemaNo ratings yet

- English SBADocument9 pagesEnglish SBAdanielleNo ratings yet

- LN13 GIS1012 LifecycleNutrition 2019Document23 pagesLN13 GIS1012 LifecycleNutrition 2019Ed100% (1)

- 2009 Positive Discipline Part 6 en PDFDocument33 pages2009 Positive Discipline Part 6 en PDFJetfoxnai AbenidoNo ratings yet

- Ctet Central Teacher Eligibility Test Child Development and Pedagogy 2020 Paper I Ii Sandeep Kumar Full ChapterDocument51 pagesCtet Central Teacher Eligibility Test Child Development and Pedagogy 2020 Paper I Ii Sandeep Kumar Full Chapterenrique.harper808100% (9)

- Fuhs - Structure and State DevelopmentDocument52 pagesFuhs - Structure and State DevelopmentMichael Kruse Craig100% (1)

- Health 7 Activity SheetsDocument31 pagesHealth 7 Activity SheetsGABINO ELECTRONIC REPAIR & PRINTING SERVICESNo ratings yet

- Full Download PDF of (Ebook PDF) Child Development: A Cultural Approach 3rd Edition All ChapterDocument43 pagesFull Download PDF of (Ebook PDF) Child Development: A Cultural Approach 3rd Edition All Chapterakhiladesty28100% (5)

- 4h Vol 102 Understanding Boys GirlsDocument6 pages4h Vol 102 Understanding Boys GirlsPrincess Trisha De FelipeNo ratings yet

- Mass Media As A Toxic MirrorDocument7 pagesMass Media As A Toxic MirrorrdmdelarosaNo ratings yet

- Proposal Writing Example 1Document16 pagesProposal Writing Example 1Ayu NagisaNo ratings yet

- EAPP SurveyDocument3 pagesEAPP SurveySuzzayne ButengNo ratings yet

- Case Study: Plan: Penny Brough in BrazilDocument16 pagesCase Study: Plan: Penny Brough in BrazilThe International Exchange (aka TIE)No ratings yet

- Psychology - Key Concepts PDFDocument281 pagesPsychology - Key Concepts PDFSolly Seid100% (1)

- FINALCHAPTERSDocument40 pagesFINALCHAPTERSAlbert N CamachoNo ratings yet

- World Mental Health Day Lesson Plans PDFDocument8 pagesWorld Mental Health Day Lesson Plans PDFNaima BulandresNo ratings yet

- Northern Mindanao Colleges, Inc.: Self-Learning Module For Personal Development Quarter 1, Week 3Document8 pagesNorthern Mindanao Colleges, Inc.: Self-Learning Module For Personal Development Quarter 1, Week 3Christopher Nanz Lagura CustanNo ratings yet

- Evaluating The Effects of Stressors and Vices in Personal and Academic Performance of Senior High School in Liceo de La Salle BacolodDocument7 pagesEvaluating The Effects of Stressors and Vices in Personal and Academic Performance of Senior High School in Liceo de La Salle BacolodEscala, John KeithNo ratings yet

- The Positive Effects of A Particular Health-Related Law in Our SocietyDocument2 pagesThe Positive Effects of A Particular Health-Related Law in Our SocietyKyle OrlanesNo ratings yet