Professional Documents

Culture Documents

1 s2.0 S1083318813002350 Main PDF

1 s2.0 S1083318813002350 Main PDF

Uploaded by

r.sax00n0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

21 views5 pagesA total of 521 patients less than 20 years of age were included in this study. 92 had non-neoplastic lesions, 382 had benign neoplasms, and 47 had malignant tumors. The primary presenting symptoms and signs were abdominal pain and menstrual disorder.

Original Description:

Original Title

1-s2.0-S1083318813002350-main.pdf

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentA total of 521 patients less than 20 years of age were included in this study. 92 had non-neoplastic lesions, 382 had benign neoplasms, and 47 had malignant tumors. The primary presenting symptoms and signs were abdominal pain and menstrual disorder.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Download as pdf or txt

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

21 views5 pages1 s2.0 S1083318813002350 Main PDF

1 s2.0 S1083318813002350 Main PDF

Uploaded by

r.sax00nA total of 521 patients less than 20 years of age were included in this study. 92 had non-neoplastic lesions, 382 had benign neoplasms, and 47 had malignant tumors. The primary presenting symptoms and signs were abdominal pain and menstrual disorder.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Download as pdf or txt

You are on page 1of 5

Case Report

Ovarian Masses in Children and Adolescents - An Analysis of 521 Clinical Cases

Mingxing Zhang MD, Wei Jiang MD, PhD, Guiling Li MD, PhD*, Congjian Xu MD, PhD*

Obstetrics and Gynecology Hospital, Fudan University, Shanghai Key Laboratory of Female Reproductive Endocrine Related Diseases, Shanghai, China

a b s t r a c t

Objective: To analyze the clinical characteristics of ovarian masses in children and adolescents.

Materials and Methods: We performed a retrospective analysis of patients less than 20 years of age who were treated at the Obstetrics and

Gynecology Hospital of Fudan University between March 2003 and January 2012. Medical records were reviewed for age at operation,

including presentation of symptoms and signs; the levels of tumor markers; imaging examinations; pathologic ndings; the size of

masses; treatment; and outcome. Data management and descriptive analyses were performed using SPSS 16.0.

Results: A total of 521 patients were included in this study. Among them, 92 had non-neoplastic lesions, 382 had benign neoplasms, and

47 had malignant tumors. The mean age of the patients was 16.3 2.2 years. The primary presenting symptoms and signs were abdominal

pain (39.5%), menstrual disorder (31.1%), abdominal swelling (5.4%), and an enlarged abdominal perimeter (3.3%). Malignant tumors

tended to be larger than benign neoplasms (17.3 8.6 cm vs 9.0 5.7 cm; P 5 .000). There was no age difference between patients with

benign neoplasms (16.3 2.1 y) and those with malignant tumors (15.7 2.5 y). The operations included salpingo-oophorectomy, ovarian

cystectomy, and oophorectomy. Two patients with malignant tumors had bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, and 2 patients who had tumor

metastasis underwent a total abdominal hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy. Forty-one cases of malignant tumors received

postoperative chemotherapy.

Conclusions: Germ cell tumors are the most common malignancy, and mature teratomas are the most common benign neoplasms in

children and adolescents. Abdominal pain and menstrual disorder are the main reasons for doctors visit. Although examination by ul-

trasound is the preferred auxiliary in the diagnosis of ovarian pathology, it could not distinguish between benign and malignant tumors.

However, tumor size and tumor markers are helpful to identify the properties of masses. Surgery is usually better for treatment, and it is

preferable to attempt conservative, fertility-sparing surgery in adolescents. Postoperative chemotherapy is necessary for malignant

tumors.

Key Words: Ovarian masses, Children, Adolescents

Introduction

Ovarian masses represent the most frequent tumors

of the female genital tract in children and adolescents.

1

The incidence of ovarian masses has been estimated at 2.6

cases per 100,000 girls each year, and malignant ovarian

tumors make up approximately 1% of all childhood can-

cers.

2

Childhood ovarian masses represent a heterogeneous

group of lesions with many etiologies. Up to 64% of these

masses are reported to be neoplastic. Less than 20% of such

neoplasms are derived from the surface epithelium of

the ovary, whereas the majority of these neoplasms arise

from germ cells.

3,4

Although benign neoplasms greatly

outnumber malignant ones in this age group and although

their clinical symptoms and signs are non-specic, it is

critical to determine the possibility of malignancy at an

early stage by currently available multi-modal diagnostic

methods. Most ovarian masses discovered in infants, chil-

dren and adolescents are removed surgically. Operative

procedures involving the ovary in young patients can

compromise future fertility, due either to removal of the

ovary or to formation of adhesions. Laparoscopic ap-

proaches are used to adequately assess and resect ovarian

tumors that are benign.

5,6

However, the use of laparoscopy

or minimally invasive techniques remains controversial in

children with ovarian malignancies.

7

This retrospective study reviews the clinical practice and

outcome of the operative treatment of ovarian masses in

children and adolescents at the Obstetrics and Gynecology

Hospital of Fudan University over the past 9 years.

Materials and Methods

We searched the pathology database in our hospital to

identify all patients who had ovarian tissue submitted for

pathologic analysis from March 2003 to January 2012. Five

hundred twenty-one patients were identied and had

medical records available. Thirteen patients, including 8

patients with malignant ovarian tumors and 5 with benign

diseases, were primarily treated elsewhere and had path-

ologic material submitted for consultation. Among the 13

patients, 7 patients had second or third operations at our

hospital, of which 2 malignant cases were due to distant

metastasis and 5 benign cases were due to recurrence in situ

or other sites. All patients were less than 20 years old. The

retrospective data from the hospital medical records

The authors indicate no conicts of interest.

* Address correspondence to: Guiling Li and Congjian Xu, Department of Gyne-

cology, Obstetrics and Gynecology Hospital of Fudan University, 419 Fang-Xie

Road, Shanghai, 200011, P. R. China; Phone: 86-21-63455050; fax: 86-21-

63455600

E-mail addresses: guilingli@fudan.edu.cn (G. Li), xucongjian@gmail.com (C. Xu).

1083-3188/$ - see front matter 2013 North American Society for Pediatric and Adolescent Gynecology. Published by Elsevier Inc.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jpag.2013.07.007

included age at operation, presenting symptoms and signs,

and the levels of tumor markers (CA 125, CA199, carci-

noembryonic antigen (CEA), human chorionic gonadotropin

(b-hCG,) a-fetoprotein). We reviewed all imaging exami-

nations including the results of ultrasonography and

computed tomography (CT) scans. We reviewed all opera-

tion records, and, when available, we recorded the sizes of

all masses as documented at surgery or in the pathology

record. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of

Obstetrics and Gynecology Hospital of Fudan University.

Statistical analyses were performed using Students t test

as appropriate. A P value of .05 or less was regarded as

statistically signicant. All continuous data are expressed as

the mean SD.

Results

Five hundred twenty-one patients underwent 524 op-

erations for ovarian mass removal at our hospital during the

past 9 years. Among the 524 operations, 434 surgeries, up to

82 percent of all operations, were operated by means of a

laparoscope. The principal pathology was in the right ovary

in 241 (46%) patients, the left ovary in 201 (38%) patients,

and 82 (16%) patients had bilateral disease.

The patients ranged in age from 9 years to 19 years, with

a mean age of 16.3 2.2 years at the time of surgery. We

found no difference in the age of presentation between

patients who had benign neoplasms (16.3 2.1 y) and those

who had malignant tumors (15.7 2.5 y; P 5 .115; Table 1).

However, there was a signicant difference in tumor size

between patients who had benign neoplasms (9.0 5.7 cm)

and those with malignant tumors (17.3 8.6 cm; P 5 .000;

Table 1).

Ultrasonography (US) was performed in 495 (95%) pa-

tients to dene the size of the lesion and the gross

morphologic nature of the tumor. Only 29 (5.5%) patients

had abdominal CT scans, and 6 (1.1%) had magnetic reso-

nance imaging, where further evaluation of the nature of

the ovarian tumor and abdominal organs was necessary.

Overall, there were 48 patients who had ovarian torsion,

and 20 had an ovarian rupture. However, only 14 patients

received a diagnosis of torsion or rupture based on US.

Benign Diseases

Four hundred seventy-four patients had benign diseases

and 47 patients had malignant tumors. A list of all tumor

types is included in Table 2.

The primary presenting symptoms and signs that led to a

visit to the doctor included abdominal pain (n 5 187;

39.5%), menstrual disorder (n 5 156; 32.9%), abdominal

swelling (n 518; 3.8%), an enlarged abdominal perimeter (n

5 14; 3.0%), precocious puberty (n 5 4; 0.8%), or

premenarchal (n 5 4; 0.8%). In 78 patients, pelvic masses

were found through physical examinations during the

follow-up of other diseases, and in the other 13 patients, the

masses were incidentally found by self-palpation (Table 3).

Ultrasonography was performed in 453 (96%) patients to

dene the size of the lesion and gross morphologic nature

of the tumor such as a solid mass (n 5 20, 6%), a complex

mass (n 5 158, 34%), or a cyst (n 5 275, 60%). The charac-

teristics of ultrasonographic performance of benign tumors

are clear boundary and cystic or complex mass. Most of

blood supply distributes around the lesion.

a-fetoprotein (AFP) was done in 197 patients, and the

level raised in 4 of them.b-HCG was done in 32 patients, and

none of them had a rise. CA125 was done in 213 patients,

and in 53 cases it raised, 30 turned out to be benign neo-

plasms and other cases were non-neoplasms. CA199 was

done in 251 patients, and in 141 of them it raised included

109 benign neoplasms and 10 non-neoplasms. CEA was

done in 161 patients, and none of them had a rise.

In the group with benign diseases, 481 operations in

total were performed for 474 patients. Seven patients

(including 4 cases that were primarily treated elsewhere)

underwent 2 separate operations, and 2 patients (including

1 patient who was primarily treated elsewhere) underwent

3 separate operations. Among patients with benign lesions,

48 had unilateral salpingo-oophorectomy. Of the 48 pa-

tients, 37 had adnexal torsion or ovarian torsion and 11

patients had other conditions.

Malignant Tumors

Patients whose pathology ndings showed malignancy

are listed in Table 2.

Of the malignant group, 19 (40.4%) patients had acute or

chronic abdominal pain, 10 (21.3%) patients had abdominal

Table 1

Comparison of Characteristic of Benign and Malignant Neoplasms

Benign Neoplasms

(n 5 382)

Malignant Neoplasms

(n 5 47)

P-Value

Age at presentation (y) 16.3 2.1 15.7 2.5 .115

Tumor size (cm) 9.0 5.7 17.3 8.6 .000

Table 2

Pathologic Findings of 521 Patients

Pathology No. of

Patients

Percent of

Total

Non-neoplastic 92 17.7

Ovarian torsion (without an associated tumor) 8 1.5

Corpus luteal cyst 9 1.7

Follicular cyst 27 5.2

Simple ovarian cyst 16 3.1

Endometrioma 32 6.1

Neoplastic: benign 382 73.3

Mature teratoma 270 51.8

Cystadenoma 86 16.5

Fibrothecoma 4 0.8

Struma ovarii 3 0.6

Sclerosing stromal tumor 3 0.6

Ovarian theca cell tumor 1 0.2

Fibroma 1 0.2

Ovary sex cord tumor with annular tubules 1 0.2

Borderline cystadenoma 13 2.5

Neoplastic: malignant 47 9

Immature teratoma 19 3.6

Invasive mucinous cystadenocarcinoma 8 1.5

Yolk sac tumor 5 1.0

Dysgerminoma 4 0.8

Mixed germ cell tumor 4 0.8

Sertoli-Leydig cell tumor 4 0.8

Juvenile granulosa cell tumor 1 0.2

Gonadoblastoma 2 0.4

M. Zhang et al. / J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol xxx (2013) 1e5 2

swelling, 3 (6.4%) patients had a palpable abdominal mass, 6

(12.8%) patients had a menstrual disorder, 3 (6.4%) patients

had an enlarged abdominal perimeter, 2 (4.2%) patients

were premenarchal, 1 (2.1%) patient had vomiting, and 3

(6.4%) patients found masses incidentally (Table 3).

Forty-two of these patients had an ultrasonography and

13 were complex masses, 21 were cysts, and 8 were solid

masses. The characteristics of ultrasonographic perfor-

mance of malignant tumors are irregular shape, unclear

boundary, and solid or predominantly solid mixed mass.

And most of blood supply distributes in the interior of solid

mass. Among the 31 patients who had an AFP test, 21 had

increased AFP levels. b-HCG increased in only 1 patient with

mixed germ cell tumor. CA125 was tested in 32 patients,

and it increased in 21 cases. CA199 was analyzed in 23 pa-

tients, and 12 patients had increased levels. CEA was

analyzed in 27 patients, and in 1 patient with immature

teratomas of left ovary the level had elevated.

There were 43 operations for 47 patients; 8 patients were

rst treated in other hospitals, and 2 patients were operated

on twice in our hospital. The malignant lesions included 32

(68%) germ cell tumors, 8 (17%) epithelial tumors (Table 4),

and 7 (15%) sex-cord stromal tumors (Table 4).

Of the 19 cases of immature teratomas, 5 patients were

treated with ovarian cystectomy and the remaining patients

underwent unilateral salpingo-oophorectomy. In addition,

only 8 patients underwent pelvic lymph node dissection, 5

underwent omentectomy, and 2 underwent appendectomy.

Data regarding the stages of immature teratomas was

available in only 13 patients; 10 were staged Ia, and 3 were

staged Ic. All but 2 patients received postoperative

chemotherapy, including 7 patients who received cisplatin,

bleomycin, and vinblastine, 9 who received cisplatin,

etoposide, and bleomycin (PEB), and 1 who received

vincristine, cytoxan, and actinomycin D. The course of

chemotherapy varied from 1 cycle to 7 cycles, with a mean

of 3.7 cycles. Three patients lost to follow-up, and all others

are alive and well. The mean time of follow-up was 3.77

3.33 years.

We also reviewed the treatment and outcome of other

malignant germ cell tumors (Table 5). One patient with

dysgerminoma had an oophorectomy at another hospital,

followed by 6 cycles of chemotherapy (cisplatin, etopo-

side, and bleomycin) at our hospital. Two patients with

gonadoblastomas had bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy,

and 2 patients who had tumor metastasis underwent a

total abdominal hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-

oophorectomy.

Discussion

Ovarian tumors account for approximately 1% of all tu-

mors in children and adolescents. Less than 5% of malignant

ovarian tumors occur in this age group. Thirty percent of all

ovarian neoplasms occurring during childhood and

adolescence are maliganant.

3

In our study, 91% of ovarian

masses were benign, and only 9% of ovarian masses were

malignant, which is consistent with recent reports.

2,8

However, Brown et al

9

reported that 33% of ovarian

masses in patients between the ages of 8 and 18 years were

malignant. Of the malignant group, 68% were germ cell

tumors, and only 17% were surface epithelial neoplasms,

which is consistent with other studies.

10-12

Symptoms and signs are varied and non-specic.

13,14

Based on our study, for both benign and malignant dis-

eases, the most common symptom was abdominal pain.

While different frompatients with benign diseases, patients

with malignant tumors presented abdominal swelling more

often, rather than menstrual disorders. Therefore, parents

should pay attention when their children have menstrual

changes (cycles, period, and dysmenorrhea), acute or

chronic abdominal pain, an increasing abdominal girth, or

abdominal swelling. A sonogram during physical examina-

tion is essential for identifying problems.

Analysis of symptoms and signs cannot, however,

distinguish between benign and malignant lesions. The

classication of ovarian masses is complex,

15

as most

ovarian masses in children are benign diseases. For these

reasons, it is difcult to make the correct preoperative

diagnosis. In distinguishing patients with benign disease

from those with malignancy, we found that age (P 5 .115)

was not useful, whereas imaging characteristics, tumor size,

and tumor markers were important. Malignant lesions

tended to be larger (P 5 .000) in our analysis, which was

consistent with previous ndings.

16

Ultrasound has been

found to be a helpful diagnostic tool for ovarian masses.

17

Of

the 26 solid ovarian masses identied by ultrasound, 8 were

malignant. Solid ovarian masses identied by ultrasound

were more likely to be malignant.

18

However, both malig-

nant and benign neoplasms can appear cystic, in which

case, AFP is helpful to preoperatively distinguish these le-

sions. The clinical application of serum AFP concentration is

of great benet not only as diagnostic aid but also in

monitoring the efcacy of any treatment modality, such as

chemotherapy, radiotherapy or surgical resection.

19,20

In

this study, AFP was raised in 25 cases and 21 turned out to

have malignant tumors.

The treatment of ovarian masses in children and adoles-

cents is generally conservative, whether expectant, medical,

or surgical. For the surgical treatment of benign masses, the

preservation of ovarian tissue and function is very impor-

tant, and cystectomy by laparoscopic approach is advo-

cated.

11

Given the high rate of relapse of borderline

mucinous or serous cystadenoma, doctors in our hospital

usually remove unilateral adnexa. However, in this study

there were only 4 patients who decided to have unilateral

Table 3

Presenting Symptoms, Signs, and Indications in 521 Patients

Presenting Symptoms/Signs No. of Patients (%)

Benign (n 5 474) Malignant (n 5 47)

Abdominal pain 187 (39.5) 19 (40.4)

Abdominal swelling 18 (3.8) 10 (21.3)

Enlarged abdominal perimeter 14 (3.0) 3 (6.4)

Menstrual disorder 156 (32.9) 6 (12.8)

Physical examination 78 (16.5) 0

Precocious puberty 4 (0.8) 0

Premenarchal 4 (0.8) 2 (4.2)

Palpable abdominal mass 0 3 (6.4)

Vomiting 0 1 (2.1)

Incidental nding 13 (2.7) 3 (6.4)

M. Zhang et al. / J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol xxx (2013) 1e5 3

salping-oophorectomy. And the other 9 patients had cys-

tectomy for parent demands. Two of the 9 patients had a

recurrence. On these grounds, it is suggested that patients

with borderline tumors can have conservative cystectomy.

But we need more data to support this conclusion.

Of the other 461 benign diseases, there were only 7 pa-

tients who did not have cyst torsion and undergo salpingo-

oophorectomy. After detailed reading of medical records,

we think some factors may drive doctors to take such

measures. These inuencing factors are patients age, tumor

size, and remaining functional ovarian tissue, and adhesion

formation. For example, a younger patient with a giant mass

growing in a short time came for help. During surgery, we

found that the affected ovary had no remaining formal

functional tissue, and pelvic adhesion had formed. Then we

usually removed the ovary completely.

For suspected malignancies, a conservative surgical

treatment approach with unilateral salpingo-oophorectomy

and staging is appropriate.

11

In a past study, a postoperative

ultrasound revealed that the affected ovary resumed its

normal size and volume despite the attenuated appearance

of the ovarian cortex at the time of surgery.

21

Moreover,

Table 4

Treatment and Outcome of Patients with Invasive Mucinous Cystadenocarcinomas and Sex Cord-Stromal Tumors

Patient No. Age (y) Diagnosis Operation Stage Chemotherapy Outcome: F/U (yr)

1 17 Invasive Mucinous

Cystadenocarcinomas

LSO, appendectomy Not staged TP, six cycles NED, 5

2 17 Invasive Mucinous

Cystadenocarcinomas

RSO, appendectomy* Not staged No NED, 2.5

3 16 Invasive Mucinous

Cystadenocarcinomas

LSO, appendectomy Not staged No NED, 0.5

4 19 Invasive Mucinous

Cystadenocarcinomas

Left cystectomy a No Loss to FU

5 18 Invasive Mucinous

Cystadenocarcinomas

LSO Not staged PC, one cycle NED, 7

6 16 Invasive Mucinous

Cystadenocarcinomas

RSO, appendectomy, omentectomy,

PLND, interval TAHLSO

c TP, eight cycles NED, 3.5

7 16 Invasive Mucinous

Cystadenocarcinomas

LSO, omentectomy c TP, 3 cycles NED, 0

8 16 Invasive Mucinous

Cystadenocarcinomas

RSO a No NED, 4

9 18 SLCT RSO Not staged PEB, 4 cycles NED, 2.5

10 19 SLCT Right cystectomy Not staged PVB, 1 cycle NED, 8

11 15 SLCT LSO Not staged TP, 6 cycles NED, 8

12 17 SLCT LSO Not staged CAP, 6 cycles NED, 8

13 18 JGCT LSO Not staged PEB, 4 cycles NED, 3

14 17 Gonadoblastoma BSO Not staged PVB, 3 cycles NED, 4.5

15 14 Gonadoblastoma BSO Not staged PEB, 4 cycles NED, 2

CAP, cytoxan, adriamycin, cisplatin: F/U, follow-up; JGCT, Juvenile granulosa cell tumor; LSO, left salpingo-oophorectomy; NED, no evidence of disease; PC, cytoxan and

cisplatin; PEB, cisplatin, etoposide, and bleomycin; PLND, pelvic lymph node dissection; PVB, cisplatin, bleomycin, and vinblastine; RSO, right salpingo-oophorectomy; SLCT,

Sertoli-Leydig cell tumor; TAHBSO, total abdominal hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy; TP, cisplatin and paclitaxel; TP, cisplatin and paclitaxel

* Patient who was treated in other hospital primarily.

Table 5

Treatment and Outcome of 13 Patients with Malignant Germ Cell Tumors

Patient No. Age (yr) Diagnosis Operation Stage Chemotherapy Recurrence Outcome:

F/U (yr)

1 16 YST, Turner's

syndrome

RSO, PLND,

omentectomy

a PEB, 6 cycles No NED, 0.5

2 17 YST LSO*, omentectomy Not staged PEB, 6 cycles Yes @ 1 year Loss to FU

3 12 YST Not quiet clear* Not quiet clear PVB, 10 cycles Yes @ 1 year, staged c,

cytoreductive surgery, part

transverse colon and small

intestinal resection and

anastomosis

Died after

one year

4 16 YST RSO, omentectomy a PVB, 6 cycles No Loss to FU

5 15 YST TAHBSO, PLND c PVB, 6 cycles No Loss to FU

6 12 Dysgerminoma RSO a PEB, 4 cycles No NED, 2.25

7 10 Dysgerminoma RSO, appendectomy* a PEB, 6 cycles No NED, 1.5

8 9 Dysgerminoma RSO c PEB, 6 cycles No NED, 4.5

9 19 Dysgerminoma Left oophorectomy* Not staged PEB, 6 cycles No NED, 1.5

10 13 MGCT RSO* Not staged VAC*, 1 cycle

PEB, 1 cycle

Yes @ 2 mon, cystectomy

surgery, appendectomy,

omentectomy

Loss to FU

11 15 MGCT RSO, omentectomy c PEB No NED, 1

12 16 MGCT LSO, omentectomy c PEB, 5cycles No NED, 5.5

13 15 MGCT RSO c PEB, 6cycles No NED, 0.25

F/U, follow-up; LSO, left salpingo-oophorectomy; MGCT, mixed germ cell tumor; mon, month; NED, no evidence of disease; PEB, cisplatin, etoposide, and bleomycin; PLND,

pelvic lymph node dissection; PVB, cisplatin, bleomycin, and vinblastine; RSO, right salpingo-oophorectomy; TAHBSO, total abdominal hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-

oophorectomy; VAC, vincristine, cytoxan, and actinomycin D; y, year; YST, yolk sac tumor

* Patient who was treated in other hospital primarily.

M. Zhang et al. / J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol xxx (2013) 1e5 4

it was reported that chemotherapy based on cisplatin is

very efcient, with a 5-year overall survival of non-

seminomatous GCT at 85%-95%.

22

In this study, only 7 pa-

tients received cystectomy; all of the other patients were

treated with unilateral or bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy,

with or without pelvic lymph node dissection. The 7 cases

included 5 immature terotomas, 1 invasive mucinous cys-

tadenocarcinoma and 1 Sertoli-Leydig cell tumor. The

reason why they underwent cystectomy was family mem-

bers demands (3 cases) and that the pathologic histology of

intraoperative frozen section indicated mature teratomas (2

cases). And in addition, 2 patients with immature teratomas

primarily operated in other hospitals, so we did not know

clearly about why they underwent cystectomy. Two of 5

patients with immature teratomas who underwent cys-

tectomy had recurrences twice in the following 3 years after

rst operation. The recurrence rate was much higher

than that of those who underwent unilateral salpingo-

oophorectomy. And the other 2 patients with malignant

lesions while underwent cystectomy lost to follow-up. In

view of the above, we do not suggest conservative cys-

tectomy for any malignant lesions. Most patients with

malignant tumors received postoperative chemotherapy. In

our experience, the PEB regimen is most commonly used in

germ cell tumors, and the paclitaxel combined with plat-

inum (TP) protocol is generally selected for surface epithe-

lial tumors.

There are limitations to our study. It was retrospective in

design, and certain data were unavailable, including stages

of some patients, and patients who were lost to follow-up.

Currently, there are no studies of ultrasound assessment

of the ovarian reserve in these patients after ovarian cys-

tectomy or unilateral salpingo-oophorectomy. Long-term

follow-up is needed to fully assess the effects of ovary-

conserving surgery on future fertility and ovarian function

in this population. In addition, long-term follow-up of

postoperative adhesion formation and its effect on fertility

should be studied.

Conclusion

Germ cell tumors are the most common malignancy;

epithelial cell tumors are less likely, and mature teratomas

are the most common benign neoplasms in children and

adolescents. Abdominal pain and menstrual disorder are

the main reasons for doctors visit. Although examination

by ultrasonogram is the preferred auxiliary in the diagnosis

of ovarian pathology, it could not distinguish between

benign and malignant tumors. However, tumor size and

tumor markers are helpful to identify the properties of

masses. Surgery is usually better for treatment, and it is

preferable to attempt conservative, fertility-sparing surgery

in adolescents. Postoperative chemotherapy is necessary for

malignant tumors.

References

1. Piura B, Dgani R, Zaled Y, et al: Malignant germ cell tumors of the ovary: a study

of 20 cases. J Surg Oncol 1995; 59:155

2. Al Jama FE, Al Ghamdi AA, Gasim T, et al: Ovarian tumors in children and

adolescents-a clinical study of 52 patients in a university hospital. J Pediatr

Adolesc Gynecol 2011; 24:25

3. Breen JL, Maxson WS: Ovarian tumors in children and adolescents. Clin Obstet

Gynecol 1977; 20:607

4. Norris HJ, Jensen RD: Relative frequency of ovarian neoplasms in children and

adolescents. Cancer 1972; 30:713

5. Millingos S, Protopapas A, Drakakis P, et al: Laparoscopic treatment of ovarian

dermoid cysts: eleven years experience. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc 2004;

11:478

6. Vaisbuch E, Dgani R, Ben-Arie A, et al: The role of laparoscopy in ovarian

tumors of low malignant potential and early-stage ovarian cancer. Obstet

Gynecol Surv 2005; 60:326

7. von Allmen D: Malignant lesions of the ovary in childhood. Semin Pediatr Surg

2005; 14:100

8. Islam S, Yamout SZ, Gosche JR: Management and outcomes of ovarian masses

in children and adolescents. Am Surg 2008; 74:1062

9. Brown MF, Hebra A, McGeehin K, et al: Ovarian masses in children: a review of

91 cases of malignant and benign masses. J Pediatr Surg 1993; 28:930

10. Young RH: Ovarian tumors of the young. Int J Surg Pathol 2010; 18(3 Suppl):

156S

11. Kirkham YA, Kives S: Ovarian cysts in adolescents: medical and surgical

management. Adolesc Med State Art Rev 2012; 23:178

12. Morowitz M, Huff D, von Allmen D: Epithelial ovarian tumors in children: a

retrospective analysis. J Pediatr Surg 2003; 38:331

13. Ryoo U, Lee DY, Bae DS, et al: Clinical characteristics of adnexal masses in

Korean children and adolescents: retrospective analysis of 409 cases. J Minim

Invasive Gynecol 2010; 17:209

14. Kirkham YA, Lacy JA, Kives S, et al: Characteristics and management of adnexal

masses in a canadian paediatric and adolescent population. J Obstet Gynecol

Can 2011; 33:935

15. Hatzipantelis ES, Dinas K: Ovarian tumours in childhood and adolescence. Eur J

Gynaecol Oncol 2010; 31:616

16. Cass DL, Hawkins E, Brandt ML, et al: Surgery for ovarian masses in infants,

children, and adolescents: 102 consecutive patients treated in a 15-year

period. J Pediatr Surg 2001; 36:693

17. Servaes S, Victoria T, Lovrenski J, et al: Contemporary pediatric gynecologic

imaging. Semin Ultrasound CT MR 2010; 31:116

18. Epelman M, Chikwava KR, Chauvin N, et al: Imaging of pediatric ovarian

neoplasms. Pediatr Radiol 2011; 41:1085

19. Malati T, Kumari GR, Yadagiri B: Application of tumor markers in ovarian

malignancies. Indian J Clin Biochem 2001; 16:224

20. Sengar AR, Kulkarni JN: Growing teratoma syndrome in a post laparoscopic

excision of ovarian immature teratoma. J Gynecol Oncol 2010; 21:129

21. Reddy J, Laufer MR: Advantage of conservative surgical management of large

ovarian neoplasms in adolescents. Fertil Steril 2009; 91:1941

22. Sarnacki S, Brisse H: Surgery of ovarian tumors in children. Horm Res Pediatr

2011; 75:220

M. Zhang et al. / J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol xxx (2013) 1e5 5

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5820)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1093)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (845)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (898)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (540)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (349)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (822)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (401)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Daaweynta Cudurrada LegalDocument113 pagesDaaweynta Cudurrada LegalBashiir Wali m86% (7)

- Hypothyroidism Nursing Care PlanDocument2 pagesHypothyroidism Nursing Care Planmrhammer1957100% (2)

- Getting Ready For Giving Birth: A Guide To Preparing Your Mind For Birth (And Why That's Way More Important Than You Thought)Document9 pagesGetting Ready For Giving Birth: A Guide To Preparing Your Mind For Birth (And Why That's Way More Important Than You Thought)Jessica PoundstoneNo ratings yet

- Holistic Health and The Critique of Western Medicine - Janet McKeeDocument3 pagesHolistic Health and The Critique of Western Medicine - Janet McKeeAlex CosiNo ratings yet

- Perspectives: Beyond The G Spot: Clitourethrovaginal Complex Anatomy in Female OrgasmDocument8 pagesPerspectives: Beyond The G Spot: Clitourethrovaginal Complex Anatomy in Female OrgasmVissente TapiaNo ratings yet

- People V HataniDocument6 pagesPeople V HataniKennethQueRaymundoNo ratings yet

- FINALE Final Chapter1 PhoebeKatesMDelicanaPR-IIeditedphoebe 1Document67 pagesFINALE Final Chapter1 PhoebeKatesMDelicanaPR-IIeditedphoebe 1Jane ParkNo ratings yet

- Lucina TechSheetDocument2 pagesLucina TechSheetMiguel M. Melchor RodríguezNo ratings yet

- Arthritis Foundation Press KitDocument5 pagesArthritis Foundation Press Kitapi-272553834No ratings yet

- Basic Hara Diagnosis An Introduction To Kiiko Style The Avi Way"Document90 pagesBasic Hara Diagnosis An Introduction To Kiiko Style The Avi Way"sillypolo100% (1)

- Breach Notification LetterDocument2 pagesBreach Notification Lettereppelmannr100% (1)

- Prevention of Pressure UlcerDocument7 pagesPrevention of Pressure UlcerDaniel Pagnocelli SusinNo ratings yet

- Cases in ObgDocument41 pagesCases in ObgShriyansh Chahar0% (1)

- Formularium PDFDocument16 pagesFormularium PDFDewayu NanaNo ratings yet

- Sound Therapy Can Be Very Effective For Treating Tinnitus - Jun, Rojas-Roncancio, Tyler - Winter' 12Document3 pagesSound Therapy Can Be Very Effective For Treating Tinnitus - Jun, Rojas-Roncancio, Tyler - Winter' 12American Tinnitus AssociationNo ratings yet

- Advanced Course Work in Therapeutic NutritionDocument8 pagesAdvanced Course Work in Therapeutic Nutritionafiwhwlwx100% (2)

- Overlay DentureDocument5 pagesOverlay DentureAmar BhochhibhoyaNo ratings yet

- Experiment #10: Direct Antihuman Globulin Test: ReferenceDocument8 pagesExperiment #10: Direct Antihuman Globulin Test: ReferenceKriziaNo ratings yet

- Toronto Sick KidsDocument13 pagesToronto Sick KidsAnonymous AuJncFVWvNo ratings yet

- RX Pricing To Rules On Calculating RX OrdersDocument4 pagesRX Pricing To Rules On Calculating RX OrdersIan GabritoNo ratings yet

- Narrative Summary of Experiences: Senior High SchoolDocument4 pagesNarrative Summary of Experiences: Senior High SchoolNicole De AsisNo ratings yet

- Sensory Processing DisorderDocument6 pagesSensory Processing DisorderMichael MoyalNo ratings yet

- HealthCare Service MarketingDocument46 pagesHealthCare Service MarketingTarang Baheti100% (1)

- Flushing AgentDocument15 pagesFlushing AgentSalman KhanNo ratings yet

- Indonesian Policy On HIV/AIDS: 1. HIV Infection in IndonesiaDocument8 pagesIndonesian Policy On HIV/AIDS: 1. HIV Infection in IndonesiadebbyanggitamsNo ratings yet

- Imci-Integrated Management of Childhood Illness - 1992 - 2 Pilot Areas AreDocument18 pagesImci-Integrated Management of Childhood Illness - 1992 - 2 Pilot Areas Arej0nna_02No ratings yet

- Diagnosis and Treatment of Diabetes Mellitus in Chronic PancreatitisDocument7 pagesDiagnosis and Treatment of Diabetes Mellitus in Chronic PancreatitisFarid TaufiqNo ratings yet

- Safety Data Sheet: Virbac New Zealand LimitedDocument5 pagesSafety Data Sheet: Virbac New Zealand LimitedХорен МакоянNo ratings yet

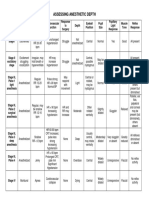

- Anesthesia-Assessing Depth PDFDocument1 pageAnesthesia-Assessing Depth PDFAvinash Technical ServiceNo ratings yet

- INTRODUCTION TO DIAGNOSTIC IMAGINGaDocument77 pagesINTRODUCTION TO DIAGNOSTIC IMAGINGaStudentNo ratings yet