Professional Documents

Culture Documents

The War On Poverty After 50 Years

The War On Poverty After 50 Years

Uploaded by

gibson150Original Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

The War On Poverty After 50 Years

The War On Poverty After 50 Years

Uploaded by

gibson150Copyright:

Available Formats

BACKGROUNDER

Key Points

The War on Poverty After 50 Years

Robert Rector and Rachel Shefeld

No. 2955 | SEPTEMBER 15, 2014

n The lack of progress in building

self-sufficiency since the begin-

ning of the War on Poverty 50

years ago is due in major part to

the welfare system itself.

n By breaking down the habits and

norms that lead to self-reliance,

welfare generates a pattern

of increasing intergeneration-

al dependence.

n By undermining productive social

norms, welfare creates a need

for even greater assistance in

the future.

n It is time to rein in the endless

growth in welfare spending and

return to President Lyndon John-

sons original goals.

n Able-bodied, non-elderly adult

recipients in all federal welfare

programs should be required

to work, prepare for work, or at

least look for a job as a condition

of receiving benefits.

n Finallyand most impor-

tantthe anti-marriage penal-

ties should be removed from

welfare programs, and long-

term steps should be taken

to rebuild the family in lower-

income communities.

Abstract

In his January 1964 State of the Union address, President Lyndon

Johnson proclaimed, This administration today, here and now, de-

clares unconditional war on poverty in America. In the 50 years since

that time, U.S. taxpayers have spent over $22 trillion on anti-poverty

programs. Adjusted for ination, this spending (which does not include

Social Security or Medicare) is three times the cost of all U.S. military

wars since the American Revolution. Yet progress against poverty, as

measured by the U.S. Census Bureau, has been minimal, and in terms

of President Johnsons main goal of reducing the causes rather than

the mere consequences of poverty, the War on Poverty has failed

completely. In fact, a signicant portion of the population is now less

capable of self-sufciency than it was when the War on Poverty began.

T

his week, the U.S. Census Bureau is scheduled to release its

annual poverty report. The report will be notable because this

year marks the 50th anniversary of the launch of President Lyndon

Johnsons War on Poverty. In his January 1964 State of the Union

address, Johnson proclaimed, This administration today, here and

now, declares unconditional war on poverty in America.

1

Since that time, U.S. taxpayers have spent over $22 trillion on

anti-poverty programs (in constant 2012 dollars). Adjusted for

ination, this spending (which does not include Social Security or

Medicare) is three times the cost of all military wars in U.S. history

since the American Revolution. Despite this mountain of spending,

progress against poverty, at least as measured by the government,

has been minimal.

This paper, in its entirety, can be found at http://report.heritage.org/bg2955

The Heritage Foundation

214 Massachusetts Avenue, NE

Washington, DC 20002

(202) 546-4400 | heritage.org

Nothing written here is to be construed as necessarily reecting the views of The Heritage

Foundation or as an attempt to aid or hinder the passage of any bill before Congress.

2

BACKGROUNDER | NO. 2955

SEPTEMBER 15, 2014

The WelfarePoverty Paradox

This week, the Census Bureau will most likely

report that the poverty rate last year was about 14

percent, essentially the same rate as in 1967, three

years after the War on Poverty was announced. As

Chart 1 shows, according to the Census, there has

been no net progress in reducing poverty since the

mid to late 1960s. Since that time, the poverty rate

has undulated slowly, falling by two to three per-

centage points during good economic times and ris-

ing by a similar amount when the economy slows.

Overall, the trajectory of ofcial poverty for the past

45 years has been at or slightly upward.

The static nature of poverty is especially surpris-

ing because (as Chart 1 also shows) poverty fell dra-

matically during the period before the War on Pover-

ty began. In 1950, the poverty rate was 32.2 percent.

By 1965 (the rst year during which any War on Pov-

erty programs began to operate), the rate had been

cut nearly in half to 17.3 percent.

2

The unchanging poverty rate for the past 45 years

is perplexing because anti-poverty or welfare spend-

ing during that period has simply exploded. As Chart

2 shows, means-tested welfare spending has soared

since the start of the War on Poverty. In scal year

2013, the federal government ran over 80 means-

1. Lyndon B. Johnson, Annual Message to the Congress on the State of the Union, January 8, 1964,

http://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/ws/index.php?pid=26787 (accessed September 8, 2014).

2. The poverty gures for 1947 through 1958 are taken from Gordon Fisher, Estimates of the Poverty Population Under the Current Ofcial

Denition for Years Before 1959, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Ofce of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation,

1986. The gures for 1953 and 1954 were interpolated. Copies of this document will be made available on request from the authors. These

estimates are not ofcial government gures.

l94 l90 l9 l960 l96 l90 l9 l9S0 l9S l990 l99 2000 200 20l0 20l2

0%

%

l0%

l%

20%

2%

:0%

:%

1964: War on

Poverty Begins

CHART 1

Sources: .es o 43. Cooo s|e Lstetes o t|e oet, o,.'eto Uoe t|e C.et Cce' Deto o

Yees 3eoe U.S. De,etet o Hee't| eo H.e Seces Cce o t|e Assstet Secete, o 'e eo Le'.eto

35. .es o 2O2. U.S. Ces.s 3.ee. C.et o,.'eto S.e, A.e' Soce' eo Lcooc S.,,'eets

Hstoce' oet, eb'eseo,'e eb'e 2 |tt,s..ces.s.o||es,oet,oete|stoce',eo,'e.|t' (eccesseo

Se,tebe O 2O4`.

PERCENTAGE OF INDIVIDUALS WHO WERE POOR BY THE OFFICIAL POVERTY STANDARD

Poverty Rate, 19472012

|etee.o 3C 2

3

BACKGROUNDER | NO. 2955

SEPTEMBER 15, 2014

tested welfare programs that provided cash, food,

housing, medical care, and targeted social services

to poor and low-income Americans.

Overall, 100 million individualsnearly one in

three Americansreceived benets from at least one

of these programs. Federal and state governments

spent $943 billion in 2013 on these programs at an

average cost of $9,000 per recipient. (Again, Social

Security and Medicare are not included in the totals.)

Today, government spends 16 times more, adjust-

ing for ination, on means-tested welfare or anti-

poverty programs than it did when the War on Pov-

erty started. But as welfare spending soared, the

decline in poverty came to a grinding halt. As Chart

2 shows, the more the government spent, the less

progress against poverty was made.

How can this paradox be explained? How can gov-

ernment spend $9,000 per recipient and have no appar-

ent impact on poverty? The answer is that it cant.

The conundrum of massive anti-poverty spend-

ing and unchanging poverty rates has a simple expla-

nation. The Census Bureau counts a family as poor

if its income falls below specic thresholds,

3

but in

counting income, the Census omits nearly all of

government means-tested spending on the poor.

4

In efect, it ignores almost the entire welfare state

3. For example, the poverty income threshold for a family of four including two children in 2013 was $23,624 per year. U.S. Census Bureau,

Preliminary Estimates of Weighted Average Poverty Thresholds for 2013, http://www.census.gov/hhes/www/poverty/data/threshld/index.html

(accessed September 8, 2014).

4. Typically, only 3 percent of total means-tested spending is counted by the Census as income for purposes of deriving the ofcial poverty measure.

l94 l90 l9 l960 l96 l90 l9 l9S0 l9S l990 l99 2000 200 20l0 20l:

0%

%

l0%

l%

20%

2%

:0%

:%

S0

S200

S400

S600

SS00

Sl000

1964: War on

Poverty Begins

CHART 2

Sources: oet, .es o 43. Cooo s|e Lstetes o t|e oet, o,.'eto Uoe t|e C.et Cce' Deto o

Yees 3eoe U.S. De,etet o Hee't| eo H.e Seces Cce o t|e Assstet Secete, o 'e eo Le'.eto

35. oet, .es o 2O2. U.S. Ces.s 3.ee. C.et o,.'eto S.e, A.e' Soce' eo Lcooc S.,,'eets

Hstoce' oet, eb'eseo,'e eb'e 2 |tt,s..ces.s.o||es,oet,oete|stoce',eo,'e.|t' (eccesseo

Se,tebe O 2O4`. `ees-testeo e'ee s,eo .es. Hetee o.oeto eseec| U.S. Cce o `eeeet eo 3.oet.

PERCENTAGE OF INDIVIDUALS WHO WERE POOR

BY THE OFFICIAL POVERTY STANDARD

TOTAL MEANS-TESTED WELFARE SPENDING,

IN BILLIONS OF CONSTANT 2012 DOLLARS

Total Means-Tested Welfare Spending and Ofcial Poverty Rate, 19472012

|etee.o 3C 2

4

BACKGROUNDER | NO. 2955

SEPTEMBER 15, 2014

when it calculates poverty. This neat bureaucratic

ploy ensured that welfare programs could grow in-

nitely while poverty remained unchanged.

Living Conditions of the Poor in America

5

Consumption by Poor Families. Since the Cen-

sus Bureau dramatically undercounts the actual

incomes of the poor, it should be no surprise to nd

that the U.S. Department of Labor routinely reports

that poor families spend $2.40 for every $1.00 of

their reported income.

6

If public housing benets are

added to the tally, the ratio of consumption to income

rises to $2.60 for every $1.00. In other words, the

income gures that the Census Bureau uses to cal-

culate poverty dramatically undercount the econom-

ic resources available to lower-income households.

Amenities. Because the ofcial Census poverty

report undercounts welfare income, it fails to pro-

vide meaningful information about the actual living

conditions of less afuent Americans. The govern-

ments own data show that the actual living condi-

tions of the more than 45 million people deemed

poor by the Census Bureau difer greatly from pop-

ular conceptions of poverty.

7

Consider these facts

taken from various government reports:

8

n Eighty percent of poor households have air condi-

tioning. By contrast, at the beginning of the War

on Poverty, only about 12 percent of the entire

U.S. population enjoyed air conditioning.

n Nearly three-quarters have a car or truck; 31 per-

cent have two or more cars or trucks.

9

n Nearly two-thirds have cable or satellite television.

n Two-thirds have at least one DVD player, and a

quarter have two or more.

n Half have a personal computer; one in seven has

two or more computers.

n More than half of poor families with children

have a video game system such as an Xbox

or PlayStation.

n Forty-three percent have Internet access.

n Forty percent have a wide-screen plasma or

LCD TV.

n A quarter have a digital video recorder system

such as a TIVO.

n Ninety-two percent of poor households have

a microwave.

5. See Robert Rector and Rachel Shefeld, Understanding Poverty in the United States: Surprising Facts About Americas Poor, Heritage

Foundation Backgrounder No. 2607, September 13, 2011,

http://www.heritage.org/research/reports/2011/09/understanding-poverty-in-the-united-states-surprising-facts-about-americas-poor,

and Robert Rector and Rachel Shefeld, Air Conditioning, Cable TV, and an Xbox: What Is Poverty in the United States Today? Heritage

Foundation Backgrounder No. 2575, July 18, 2011, http://www.heritage.org/research/reports/2011/07/what-is-poverty?ac=1.

6. Calcuated by the authors from U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, Consumer Expenditure Survey for 2012,

http://www.bls.gov/cex/home.htm#products (accessed September 8, 2014).

7. The government surveys that provide data on the actual living conditions of poor Americans include the Residential Energy Consumption Survey,

What We Eat in America, Food Security, the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, the American Housing Survey, and the Survey of

Income and Program Participation. See U.S. Department of Energy, Energy Information Administration, Residential Energy Consumption Survey,

http://www.eia.doe.gov/emeu/recs/ (accessed June 22, 2011); U.S. Department of Agriculture, What We Eat in America, NHANES 20072008,

Table 4, http://www.ars.usda.gov/SP2UserFiles/Place/12355000/pdf/0708/Table_4_NIN_POV_07.pdf (accessed June 22, 2011); Mark Nord,

Food Insecurity in Households with Children: Prevalence, Severity, and Household Characteristics, U.S. Department of Agriculture,

September 2009, http://www.ers.usda.gov/Publications/EIB56/EIB56.pdf (accessed September 7, 2011); U.S. Department of Health and Human

Services, About the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/about_nhanes.htm

(accessed September 7, 2011); U.S. Census Bureau, Current Housing Reports, Series H150/11, American Housing Survey for the United States: 2011

(Washington: U.S. Government Printing Ofce, 2013), http://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/ahs/data/2011/h150-11.html

(accessed September 8, 2014); and U.S. Census Bureau, Survey of Income and Program Participation, 2001 Panel, Wave 8 Topical Module, 2003,

http://www.bls.census.gov/sipp_ftp.html#sipp01 (accessed June 27, 2011).

8. Unless otherwise noted, data on the physical amenities in poor households are calculated from the 2009 Residential Energy Consumption

Survey (RECS) conducted by the U.S. Department of Energy,

http://www.eia.gov/consumption/residential/data/2009/index.cfm?view=microdata (accessed September 8, 2014).

9. U.S. Census Bureau, American Housing Survey for the United States: 2011.

5

BACKGROUNDER | NO. 2955

SEPTEMBER 15, 2014

For decades, the living conditions of the poor

have steadily improved. Consumer items that were

luxuries or signicant purchases for the middle

class a few decades ago have become commonplace

in poor households. In part, this is caused by a nor-

mal downward price trend following the introduc-

tion of a new product. Initially, new products tend to

be expensive and available only to the afuent. Over

time, prices fall sharply, and the product becomes

widely prevalent throughout the population, includ-

ing poor households. This is a general sign of desir-

able economic progress.

Liberals use the declining relative prices of many

amenities to argue that even though poor house-

holds have air conditioning, computers, cable TV,

and wide-screen TVs, they still sufer from sub-

stantial material deprivation in basic needs such as

food and housing. Here again, the data tell a difer-

ent story.

Poverty, Nutrition, and Hunger. Despite

impressions to the contrary, most of the poor do not

experience undernutrition, hunger, or food shortag-

es.

10

Information on these topics is collected by the

household food security survey of the U.S. Depart-

ment of Agriculture. The USDA survey shows that

in 2009:

n Ninety-six percent of poor parents stated that

their children were never hungry at any time dur-

ing the year because they could not aford food.

n Some 83 percent of poor families reported that

they had enough food to eat.

n Some 82 percent of poor adults reported that they

were never hungry at any time in the prior year

due to lack of money to buy food.

n As a group, Americas poor are far from being

chronically undernourished. The average con-

sumption of protein, vitamins, and minerals is

virtually the same for poor and middle-class

children and in most cases is well above recom-

mended norms. Poor children actually consume

more meat than do higher-income children and

have average protein intakes 100 percent above

recommended levels.

11

n Most poor children today are, in fact, supernour-

ished and grow up to be, on average, one inch taller

and 10 pounds heavier than the GIs who stormed

the beaches of Normandy in World War II.

12

Housing and Poverty. TV newscasts about pov-

erty in America generally depict the poor as homeless

or as residing in dilapidated living conditions. While

some families do experience such severe conditions,

they are far from typical of the population dened as

poor by the Census Bureau. The actual housing con-

ditions of poor families are very diferent.

13

n Over the course of a year, only 4 percent of poor

persons become temporarily homeless. At a single

point in time, one in 70 poor persons is homeless.

14

n Only 9.5 percent of the poor live in mobile homes

or trailers; 49.5 percent live in separate single-

family houses or townhouses, and 40 percent live

in apartments.

n Forty-two percent of all poor households actually

own their own homes. The average home owned

by persons classied as poor by the Census

Bureau is a three-bedroom house with one-and-

a-half baths, a garage, and a porch or patio.

10. The gures on food consumption and hunger were calculated from U.S. Census Bureau, Current Population Survey, December 2009

Food Security Supplement. The December supplement data provide the basis for the household food security reports of the U.S. Department

of Agriculture.

11. Katherine S. Tippett et al., Food and Nutrient Intakes by Individuals in the United States, 1 Day, 198991, U.S. Department of Agriculture,

Agricultural Research Service, September 1995, http://www.ars.usda.gov/SP2UserFiles/Place/12355000/pdf/csi8991_rep_91-2.pdf

(accessed September 7, 2011). More recent data are available from the authors upon request.

12. Bernard D. Karpinos, Current Height and Weight of Youths of Military Age, Human Biology, Vol. 33 (1961), pp. 336364. Recent data on

young males in poverty provided by the National Center for Health Statistics of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, based on

the second National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey.

13. Unless otherwise noted, gures on the housing of poor households are taken from U.S. Census Bureau, American Housing Survey for the United

States: 2011.

14. U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, Ofce of Community Planning and Development, The 2009 Annual Homeless Assessment

Report to Congress, June 2010, p. 8, http://www.hudhre.info/documents/5thHomelessAssessmentReport.pdf (accessed June 22, 2011).

6

BACKGROUNDER | NO. 2955

SEPTEMBER 15, 2014

n Only 7 percent of poor households are overcrowd-

ed. More than two-thirds have more than two

rooms per person.

n The average poor American has more living space

than the average individual living in Sweden,

France, Germany, or the United Kingdom. (These

comparisons are to the average citizens in foreign

countries, not to those classied as poor.)

15

n The vast majority of the homes or apartments of

the poor are in good repair and without signi-

cant defects.

By his own report, the average poor person had

sufcient funds to meet all essential needs and was

able to obtain medical care for his family through-

out the year whenever needed.

Of course, poor Americans do not live in the lap of

luxury. The poor clearly struggle to make ends meet,

but they are generally struggling to pay for cable

TV, air conditioning, and a car, as well as food for

the table. The average poor person is far from afu-

ent, but his lifestyle is equally far from the images

of stark deprivation purveyed by advocacy groups

and the mainstream media. The challenges go much

deeper than a lack of material resources.

Was the War on Poverty a Success?

Do the higher living standards of the poor mean

that the War on Poverty has been successful? The

answer is no, for two reasons. First, the incomes and

living standards of less afuent Americans were ris-

ing rapidly well before the War on Poverty began.

(See Charts 1 and 2.)

Second, and more important, to assess the War

on Poverty, we must understand President John-

sons actual goal when he launched it. The original

goal of the War on Poverty was not to prop up living

standards articially through an ever-expanding

welfare state. Instead, Johnson declared that his

war would strike at the causes, not just the conse-

quences of poverty.

16

He added, Our aim is not only

to relieve the symptom of poverty, but to cure it and,

above all, to prevent it.

17

In other words, President Johnson was not pro-

posing a massive system of ever-increasing welfare

benets, doled out to an ever-enlarging population

of beneciaries. His proclaimed goal was not a mas-

sive new system of government handouts but an

increase in self-sufciency: a new generation capa-

ble of supporting themselves out of poverty without

government handouts.

LBJ actually planned to reduce, not increase,

welfare dependence. He declared, We want to give

the forgotten fth of our people opportunity not

doles.

18

He claimed that his war would enable the

nation to make important reductions in future

welfare spending: The goal of the War on Poverty,

he stated, would be making taxpayers out of taxeat-

ers.

19

Because he viewed the War on Poverty as a

means to increase self-support, Johnson proclaimed

that it would be an investment that would return

its cost manifold to the entire economy.

Measuring Self-Sufciency

How has the War on Poverty fared with respect

to President Johnsons paramount goal of promot-

ing self-sufciency? What return have the taxpayers

reaped from their $22 trillion investment? Para-

doxically, the answers to these questions are best pro-

vided by the Census Bureaus ofcial poverty statistics.

As noted, Census poverty gures are mislead-

ing as a measure of actual living conditions because

they exclude nearly all welfare assistance. They do,

however, provide a fairly accurate measure of a fam-

ilys wages and earnings. This means that the ofcial

Census poverty gures are, in fact, a good measure

15. Kees Dol and Marietta Hafner, Housing Statistics of the European Union 2010, Netherlands Ministry of the Interior and Kingdom Relations,

September 2010, p. 51, Table 2.1, http://abonneren.rijksoverheid.nl/media/dirs/436/data/housing_statistics_in_the_european_union_2010.pdf

(accessed September 7, 2011), and U.S. Department of Energy, 2005 Residential Energy Consumption Survey, Consumption & Expenditures

Tables, Summary Statistics, Table US1, Part 2, http://www.eia.gov/emeu/recs/recs2005/hc2005_tables/c&e/pdf/tableus1part2.pdf

(accessed September 7, 2011).

16. Lyndon B. Johnson, Proposal for a Nationwide War on the Sources of Poverty, March 16, 1964,

http://www.fordham.edu/halsall/mod/1964johnson-warpoverty.html (accessed August 27, 2009).

17. Johnson, Annual Message to the Congress on the State of the Union, January 8, 1964.

18. Ibid.

19. President Lyndon Johnson, quoted in David Zaretsky, President Johnsons War on Poverty: Rhetoric and History (Tuscaloosa: University of

Alabama Press, 1986), p. 49.

7

BACKGROUNDER | NO. 2955

SEPTEMBER 15, 2014

of President Johnsons original goal of promoting

self-sufciency: the ability of a family to sustain

itself above the poverty level through its own work

and investment without reliance on welfare aid.

Chart 3 repeats the ofcial Census poverty g-

ures from Chart 1 but relabels them more accurately

as a self-sufciency index. The story told by the

chart is striking.

In the decade and a half before the start of the

War on Poverty, low-income Americans experienced

dramatic improvements in self-sufciency. The

share of Americans who lacked self-sufciency was

cut nearly in half, falling from 32.2 percent in 1950

to 17.3 percent in 1965.

During the rst six years after Johnson

announced the War on Poverty (1965 to 1970), self-

sufciency continued to improve steadily. New gov-

ernment programs were initiated. Means-tested

welfare spending increased sharply from $57 bil-

lion in 1964 to $141 billion (measured in constant

2012 dollars).

Some authors suggest that the continuing decline

in ofcial poverty from 1965 to 1970 demonstrates the

initial success of the War on Poverty, but over 90 per-

cent of the increased spending during this period was

in the form of non-cash benets that the Census does

not count for purposes of measuring poverty.

20

It is

therefore impossible for the expansion of means-test-

ed welfare to have directly produced the large decline

in ofcial poverty that occurred during this period.

Programs that in theory could have reduced pov-

erty indirectly by raising wages and employment

were regarded as largely inefective and were lim-

ited in scope. For example, in the late 1960s, only

20. Data available from the authors upon request.

l94 l90 l9 l960 l96 l90 l9 l9S0 l9S l990 l99 2000 200 20l0 20l2

0%

%

l0%

l%

20%

2%

:0%

:%

1964: War on

Poverty Begins

CHART 3

Sources: .es o O3. Cooo s|e Lstetes o t|e oet, o,.'eto Uoe t|e C.et Cce' Deto o

Yees 3eoe U.S. De,etet o Hee't| eo H.e Seces Cce o t|e Assstet Secete, o 'e eo

Le'.eto 35. .es o 2O2. U.S. Ces.s 3.ee. C.et o,.'eto S.e, A.e' Soce' eo Lcooc

S.,,'eets Hstoce' oet, eb'eseo,'e eb'e 2

|tt,s..ces.s.o||es,oet,oete|stoce',eo,'e.|t' (eccesseo Se,tebe O 2O4`.

Self-Sufciency: Percentage of Individuals Who Live in Poverty

(Excluding Welfare Benets)

|etee.o 3C 2

8

BACKGROUNDER | NO. 2955

SEPTEMBER 15, 2014

300,000 participants per year were enrolled in Job

Corps and related training programs.

21

Thus, it is implausible to suggest that the decline

in ofcial poverty between 1965 and 1970 was due

substantially to the direct or indirect efects of

War on Poverty programs. Rather, ofcial poverty

declined and self-sufciency improved for the same

general reason that these improvements occurred

before 1965: a steady rise of wages and educa-

tion levels.

Unfortunately, the situation changed in the early

1970s. The steady improvement in self-sufciency

slowed and then came to a halt. For the next four

decades, self-sufciency has remained stagnant or

has slightly worsened.

The big picture is clear: For 20 years, from 1950 to

1970, self-sufciency (and ofcial poverty) improved

dramatically. In the next four decades, there was no

progress at all; the self-sufciency rate remained

essentially static. In terms of President Johnsons

main goal of reducing the causes rather than the

mere consequences of poverty, the War on Poverty

has failed completely, despite $22 trillion in spend-

ing. In fact, a signicant portion of the population is

now less capable of self-sufciency than it was when

the War on Poverty began.

What Went Wrong?

The lack of progress in self-sufciency for the past

four decades is stunning. Many factors have contrib-

uted to this problem. For example, high school grad-

uation rates, after increasing rapidly throughout the

20th century, largely plateaued after 1970.

22

Broad

economic factors also played a role, especially the

slowdown in wage growth among low-skilled male

workers since 1973. On the other hand, employment

and wages among women increased, and this should

have led to increased self-sufciency.

23

Although President Johnson intended the War

on Poverty to increase Americans capacity for self-

support, exactly the opposite has occurred. The

vast expansion of the welfare state has dramatical-

ly weakened the capacity for self-sufciency among

many Americans by eroding the work ethic and

undermining family structure.

When Johnson launched the War on Poverty, 7

percent of American children were born outside of

marriage. Today, the number is over 40 percent. (See

0%

%

l0%

l%

20%

2%

:0%

:%

40%

4%

l94 0 l960 l90 l9S0 l90 2000 20l0 l2

CHART 4

Source: U.S. De,etet o Hee't| eo H.e Seces

Cetes o Dseese Coto' eo eeto Netoe' Cete o

Hee't| Stetstcs Netoe' Vte' Stetstcs e,ots

|tt,..coc.oc|s,oo.ctss.|t (eccesseo

Se,tebe O 2O4`.

UNMARRIED BIRTHS AS A PERCENTAGE OF ALL BIRTHS

Unwed Birth Rate, All Races,

19452012

|etee.o 3C 2

21. James T. Patterson, Americas Struggle Against Poverty 19001994 (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1995), p. 128.

22. U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics, Digest of Educational Statistics, Table 122, High school graduates, by

sex and control of school: Selected years, 186970 through 202122, http://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/d12/tables/dt12_122.asp

(accessed September 8, 2014).

23. The welfare reform legislation enacted in 1996 had a signicant positive efect in decreasing welfare dependence, increasing self-sufciency,

and reducing ofcial poverty among single mothers. After remaining largely static for 35 years, the percentage of single-mother families that

lacked self-sufciency dropped sharply from 42 percent in 1996 to 33 percent in 2000. However, most of these gains have been ofset by the

erosions of the reforms work requirements after 2001 and by the weakness of the U.S. economy after 2007. Finally, and most important, the

reforms have been overwhelmed by the growth of additional poverty-prone single-parent families since 1996.

9

BACKGROUNDER | NO. 2955

SEPTEMBER 15, 2014

Chart 4.) As the welfare state expanded, marriage

stagnated and single parenthood soared.

As Chart 5 shows, there has been no signicant

increase in the number of married-couple families

with children (both poor and non-poor) in the U.S.

since 1965. By contrast, the number of single-parent

families with children has skyrocketed by nearly 10

million, rising from 3.3 million such families in 1965

to 13.2 million in 2012. Since single-parent families

are roughly four times more likely than married-cou-

ple families to lack self-sufciency (and to be ofcially

poor), this unravelling of family structure has exerted

a powerful downward pull against self-sufciency and

substantially boosted the ofcial child poverty rate.

Since the beginning of the War on Poverty, the

absolute number of married-couple families with

children in ofcial poverty has declined, but as Chart

6 shows, the number of single-parent families in of-

cial poverty (or lacking self-sufciency) has more

than tripled, increasing from 1.6 million in 1965 to

4.8 million today. When the War on Poverty began,

36 percent of poor families with children were head-

ed by single parents; today, the gure is 68 percent.

24

The War on Poverty crippled marriage in low-

income communities. As means-tested benets

were expanded, welfare began to serve as a substi-

tute for a husband in the home, eroding marriage

among lower-income Americans. In addition, the

welfare system actively penalized low-income cou-

ples who did marry by eliminating or substantially

reducing benets. As husbands left the home, the

need for more welfare to support single mothers

increased. The War on Poverty created a destructive

feedback loop: Welfare promoted the decline of mar-

riage, which generated the need for more welfare.

Today, unwed childbearing and the resulting

growth of single-parent homes is the most important

cause of ofcial child poverty.

25

If poor women who give

birth outside of marriage were married to the fathers

of their children, two-thirds would immediately be

lifted out of ofcial poverty and into self-sufciency.

26

The welfare state has also reduced self-sufcien-

cy by providing economic rewards to able-bodied

adults who do not work or who work comparatively

little. The low level of parental work is a major cause

of ofcial child poverty and the lack of self-suf-

ciency. Even in good economic times, the median

poor family with children has only 1000 hours of

parental work per year. This is the equivalent of one

adult working 20 hours per week. If the amount of

24. U.S. Census Bureau, Current Population Survey, Annual Social and Economic Supplements, Historical Poverty TablesFamilies, Table 4,

http://www.census.gov/hhes/www/poverty/data/historical/families.html (accessed September 11, 2014) The poverty rate of single-parent male-

headed families between 1959 and 1973 is assumed to equal the 1974 rate of 15 percent. This assumption has no signicant efect on the results.

25. Out-of-wedlock childbearing is not the same thing as teen pregnancy; the overwhelming majority of non-marital births occur to young adult

women in their early twenties, not to teenagers in high school.

26. Robert E. Rector, Kirk A. Johnson, Patrick F. Fagan, and Lauren R. Noyes, Increasing Marriage Would Dramatically Reduce Child Poverty,

Heritage Foundation Center for Data Analysis Report No. CDA03-06, May 20, 2003, http://www.heritage.org/Research/Family/cda0306.cfm.

0

000

l0000

l000

20000

2000

:0000

l960 l90 l9S0 l990 2000 20l0 l2

Married-Couple Families

with Children

Single-Parent Families

with Children

CHART 5

Source: U.S. Ces.s 3.ee. C.et o,.'eto S.e, A.e'

Soce' eo Lcooc S.,,'eets Hstoce' oet,

eb'eseo,'e eb'e 2 |tt,s..ces.s.o||es

,oet,oete|stoce',eo,'e.|t' (eccesseo Se,tebe O

2O4`.

IN THOUSANDS

Total Families with Children,

19592012

|etee.o 3C 2

10

BACKGROUNDER | NO. 2955

SEPTEMBER 15, 2014

27. Robert E. Rector and Rea S. Hederman, Jr., The Role of Parental Work in Child Poverty, Heritage Foundation Center for Data Analysis Report No.

CDA03-01, January 29, 2003, http://www.heritage.org/Research/Family/cda-03-01.cfm.

work performed in poor families with children was

increased to the equivalent of one adult working

full-time through the year, the poverty rate among

these families would drop by two-thirds.

27

Conclusion

This lack of progress in building self-sufciency is

due in major part to the welfare system itself. Wel-

fare wages war on social capital, breaking down the

habits and norms that lead to self-reliance, especial-

ly those of marriage and work. It thereby generates a

pattern of increasing intergenerational dependence.

The welfare state is self-perpetuating: By undermin-

ing productive social norms, welfare creates a need

for even greater assistance in the future.

As the War on Poverty passes the half-century

mark, it is time to rein in the endless growth in wel-

fare spending and return to LBJs original goals. As

the economy improves, total means-tested spend-

ing should be moved gradually toward pre-recession

levels. Able-bodied, non-elderly adult recipients in

all federal welfare programs should be required to

work, prepare for work, or at least look for a job as a

condition of receiving benets.

Finallyand most importantthe anti-marriage

penalties should be removed from welfare programs,

and long-term steps should be taken to rebuild the

family in lower-income communities.

Robert Rector is a Senior Research Fellow and

Rachel Shefeld is a Policy Analyst in the Institute for

Family, Community, and Opportunity at The Heritage

Foundation.

0

l000

2000

:000

4000

000

l960 l96 l90 l9 l9S0 l9S l990 l99 2000 200 20l0 l2

CHART 6

Source: U.S. Ces.s 3.ee. C.et o,.'eto S.e, A.e' Soce' eo Lcooc S.,,'eets Hstoce'

oet, eb'eseo,'e eb'e 2 |tt,s..ces.s.o||es ,oet,oete|stoce',eo,'e.|t'

(eccesseo Se,tebe O 2O4`.

IN THOUSANDS

Families with Children in Ofcial Poverty, 19592012

|etee.o 3C 2

Married-Couple Families with Children

Single-Parent Families with Children

You might also like

- Beethoven Complete Piano Sonatas PDFDocument612 pagesBeethoven Complete Piano Sonatas PDFLocobardo Olorëa93% (30)

- The Cambridge Companion To The American Gothic (Book)Document280 pagesThe Cambridge Companion To The American Gothic (Book)gibson150100% (2)

- How To Debate Leftists and Destroy ThemDocument37 pagesHow To Debate Leftists and Destroy Themgibson15078% (23)

- This Study Resource Was: Directions: Complete The Following Case Study Prior To Class. Use Your Available Resources inDocument3 pagesThis Study Resource Was: Directions: Complete The Following Case Study Prior To Class. Use Your Available Resources inAnna Marie Oligo Ochea100% (1)

- Bach Chorales CompleteDocument186 pagesBach Chorales Completegibson150100% (3)

- Ulman 1996Document19 pagesUlman 1996Jefferson PessoaNo ratings yet

- The War On Poverty Turns 50Document28 pagesThe War On Poverty Turns 50Cato InstituteNo ratings yet

- The War On Poverty: Then and NowDocument43 pagesThe War On Poverty: Then and NowCenter for American ProgressNo ratings yet

- The U.S. Social Safety Net and Poverty: Lessons Learned and Promising ApproachesDocument44 pagesThe U.S. Social Safety Net and Poverty: Lessons Learned and Promising ApproachesShishir PriyadarisiNo ratings yet

- Global PovertyDocument5 pagesGlobal Povertyapi-302854472No ratings yet

- Lecture 8 (ED)Document10 pagesLecture 8 (ED)Nouran EssamNo ratings yet

- The Effect of Economic Growth On Poverty in Eastern Europe. Zarządzanie PubliczneDocument8 pagesThe Effect of Economic Growth On Poverty in Eastern Europe. Zarządzanie PubliczneSKNo ratings yet

- Original Chapter 3 ECO 310 Growth Poverty and Inequality Econ DevetDocument6 pagesOriginal Chapter 3 ECO 310 Growth Poverty and Inequality Econ DevetFLORELY LUNANo ratings yet

- Aggregate Poverty Measures: University of Colorado at DenverDocument40 pagesAggregate Poverty Measures: University of Colorado at DenverAmitNo ratings yet

- Final 1.1 Poverty and Income DistributionDocument19 pagesFinal 1.1 Poverty and Income Distributionjayson deeNo ratings yet

- Economic Development Key To Poverty AssigmentDocument7 pagesEconomic Development Key To Poverty AssigmentNighat PervezNo ratings yet

- AE 210 - Assignment # 2Document3 pagesAE 210 - Assignment # 2Jinuel PodiotanNo ratings yet

- Poor People PowerlessDocument5 pagesPoor People Powerlessvd475y4w5pNo ratings yet

- Re-Examining Poverty CEF Chuck DeVoreDocument20 pagesRe-Examining Poverty CEF Chuck DeVoreTPPFNo ratings yet

- Itisastateor Situation in Which A Person or A Group of People Don't Have Enough Money or The Basic Things They Need To LiveDocument7 pagesItisastateor Situation in Which A Person or A Group of People Don't Have Enough Money or The Basic Things They Need To LiveDurjoy SarkerNo ratings yet

- Definition of PovertyDocument7 pagesDefinition of Povertyapi-259815497No ratings yet

- PovertyDocument13 pagesPovertyJay RamNo ratings yet

- Poverty in India: Concepts, Measurement and TrendsDocument8 pagesPoverty in India: Concepts, Measurement and TrendsSadaf KushNo ratings yet

- Poverty Inequality and DevelopmentDocument14 pagesPoverty Inequality and DevelopmentAnoshaNo ratings yet

- The Impact of Changes in Human Fertility On Poverty The Journal of Development StudiesDocument30 pagesThe Impact of Changes in Human Fertility On Poverty The Journal of Development StudiesSKNo ratings yet

- SOEN Research Study - PovertyDocument23 pagesSOEN Research Study - PovertyJose Patrick Edward EspinosaNo ratings yet

- Shoaib - 1176 - 3641 - 1 - Poverty Inequality and DevelopmentDocument14 pagesShoaib - 1176 - 3641 - 1 - Poverty Inequality and DevelopmentHiba GhaniNo ratings yet

- A Comprehensive Analysis of Poverty in IndiaDocument63 pagesA Comprehensive Analysis of Poverty in IndiaFiroz shaikhNo ratings yet

- FMGD Pre-Course Assignment: Krishna Kumari Sahoo UM14029Document4 pagesFMGD Pre-Course Assignment: Krishna Kumari Sahoo UM14029Krishna Kumari SahooNo ratings yet

- Essay - Universal Basic IncomeDocument5 pagesEssay - Universal Basic IncomeAsfa SaadNo ratings yet

- Concept of Economic Development and Its MeasurementDocument27 pagesConcept of Economic Development and Its Measurementsuparswa88% (8)

- PalgraveDictionary2008withSachs ExtremePovertyDocument14 pagesPalgraveDictionary2008withSachs ExtremePovertyTulip TulipNo ratings yet

- There Are Four Reasons To Measure Poverty:: One ApproachDocument6 pagesThere Are Four Reasons To Measure Poverty:: One ApproachHilda Roseline TheresiaNo ratings yet

- SSE 108 Module 3Document20 pagesSSE 108 Module 3solomonmaisabel03No ratings yet

- Policy Response To Poverty and Inequality in The Developing World: Where Should The Priorities Lie?Document29 pagesPolicy Response To Poverty and Inequality in The Developing World: Where Should The Priorities Lie?franckiko2No ratings yet

- Income Inequality in America: Fact and FictionDocument35 pagesIncome Inequality in America: Fact and FictionAmerican Enterprise InstituteNo ratings yet

- Gale Researcher Guide for: Poverty Policies in the United StatesFrom EverandGale Researcher Guide for: Poverty Policies in the United StatesNo ratings yet

- National Income and Income DistributionDocument18 pagesNational Income and Income DistributionLAZINA AZRINNo ratings yet

- Determinants of Households' Poverty and Vulnerability in Bayelsa State of NigeriaDocument10 pagesDeterminants of Households' Poverty and Vulnerability in Bayelsa State of NigeriainventionjournalsNo ratings yet

- ManuscriptDocument18 pagesManuscriptAndrewNo ratings yet

- Jurnal 6Document40 pagesJurnal 6Ade Jamal MirdadNo ratings yet

- Position of PovertyDocument8 pagesPosition of PovertyHenry Bet100% (1)

- Barbara EhrenreichDocument17 pagesBarbara EhrenreichRon PascalNo ratings yet

- Deaton (2005)Document19 pagesDeaton (2005)Hope LessNo ratings yet

- Economic DevelopmentDocument16 pagesEconomic DevelopmentNeha UjjwalNo ratings yet

- Unit Vi FinalDocument28 pagesUnit Vi FinalCatrina Joanna AmonsotNo ratings yet

- Chapter 2Document25 pagesChapter 2وائل مصطفىNo ratings yet

- PovertyDocument9 pagesPovertydr7dh8c2sdNo ratings yet

- National Income As An Index of DevelopmentDocument7 pagesNational Income As An Index of DevelopmentNguyễn Tùng SơnNo ratings yet

- The American Welfare State How We Spend Nearly $1 Trillion A Year Fighting Poverty - and Fail, Cato Policy Analysis No. 694Document24 pagesThe American Welfare State How We Spend Nearly $1 Trillion A Year Fighting Poverty - and Fail, Cato Policy Analysis No. 694Cato Institute100% (1)

- Poverty, Nutrition and Income InequalityDocument28 pagesPoverty, Nutrition and Income InequalityDarrr RumbinesNo ratings yet

- What Is Poverty?Document25 pagesWhat Is Poverty?aarash0003No ratings yet

- Poverty and Social Exclusion Chap2Document42 pagesPoverty and Social Exclusion Chap2Madalina VladNo ratings yet

- Lecture 2. Growth and Inclusion RelationshipDocument14 pagesLecture 2. Growth and Inclusion RelationshipAzər ƏmiraslanNo ratings yet

- Reader 4 2022 PovertyDocument30 pagesReader 4 2022 PovertyramonafinanceNo ratings yet

- D S: T V H .: David N. WeilDocument9 pagesD S: T V H .: David N. WeilGhiozeline TorrezNo ratings yet

- Article 3Document17 pagesArticle 3Tianna Douglas LockNo ratings yet

- Essay - Welfare Policy-CarlosDocument9 pagesEssay - Welfare Policy-CarlosCarles AlvezNo ratings yet

- Final Halving Global PovertyDocument31 pagesFinal Halving Global PovertyFiras FrangiehNo ratings yet

- Public AdministrationDocument10 pagesPublic AdministrationDurjoy SarkerNo ratings yet

- Week 1 Definition of Concepts in Poverty EradicationDocument4 pagesWeek 1 Definition of Concepts in Poverty EradicationMwaura HarrisonNo ratings yet

- ReportDocument25 pagesReportosamaNo ratings yet

- Poverty and Economic DisparityDocument7 pagesPoverty and Economic Disparitymeetanshi01No ratings yet

- A Way Out of No Way: The Economic Prerequisites of the Beloved CommunityFrom EverandA Way Out of No Way: The Economic Prerequisites of the Beloved CommunityNo ratings yet

- Sleeman 3-ThuggeeDocument493 pagesSleeman 3-Thuggeegibson150No ratings yet

- Bartok Serbo Croatian Folk SongsDocument462 pagesBartok Serbo Croatian Folk Songsgibson150No ratings yet

- Brahms-Cello Sonata 2Document29 pagesBrahms-Cello Sonata 2gibson150No ratings yet

- Well-Tempered Clavier Book 1 PDFDocument134 pagesWell-Tempered Clavier Book 1 PDFgibson150No ratings yet

- Cambridge History English Literature Vol 11Document542 pagesCambridge History English Literature Vol 11gibson150No ratings yet

- Chopin Nocture Op 72 in emDocument6 pagesChopin Nocture Op 72 in emgibson150No ratings yet

- Beethoven BiographyDocument100 pagesBeethoven Biographygibson150No ratings yet

- De Casu DiaboliDocument50 pagesDe Casu DiaboliLessandroCostaNo ratings yet

- Beethoven Symphony No 5Document106 pagesBeethoven Symphony No 5gibson150100% (1)

- Lectures On The History of Rome Vol 1Document237 pagesLectures On The History of Rome Vol 1gibson150100% (1)

- IMSLP30364-PMLP01410-Beethoven Sonaten Piano Band1 Peters Op13Document18 pagesIMSLP30364-PMLP01410-Beethoven Sonaten Piano Band1 Peters Op13gibson150No ratings yet

- The Transformation of The American Economy, 1865-1914 - 2Document161 pagesThe Transformation of The American Economy, 1865-1914 - 2gibson150No ratings yet

- Early Journal Content On JSTOR, Free To Anyone in The WorldDocument4 pagesEarly Journal Content On JSTOR, Free To Anyone in The Worldgibson150No ratings yet

- Paganini 24 CapricciDocument56 pagesPaganini 24 Capriccigibson150No ratings yet

- Edvard GriegDocument188 pagesEdvard Grieggibson15075% (4)

- BeethovenDocument100 pagesBeethovengibson15089% (9)

- Psychology of Health in IndiaDocument33 pagesPsychology of Health in IndiaSrestha GhoshNo ratings yet

- Child Malnutrition in PunjabDocument7 pagesChild Malnutrition in PunjabAhmed Naqvi100% (1)

- Development and Use of Alternative Nutrient-Dense Foods For Management of Acute Malnutrition in IndiaDocument4 pagesDevelopment and Use of Alternative Nutrient-Dense Foods For Management of Acute Malnutrition in IndiaAakash KharakiaNo ratings yet

- Malnutrition Among Children Under 5 Does NotDocument16 pagesMalnutrition Among Children Under 5 Does NotBheru LalNo ratings yet

- hw320 Unit 9 Final Project 1Document14 pageshw320 Unit 9 Final Project 1api-723636846No ratings yet

- L PDFDocument51 pagesL PDFMs RawatNo ratings yet

- To What Extent The Government's Role in Overcoming Stunting? DataDocument3 pagesTo What Extent The Government's Role in Overcoming Stunting? DataTariNo ratings yet

- Food Insecurity in Africa in Terms of Causes, Effects and Solutions: A Case Study of NigeriaDocument9 pagesFood Insecurity in Africa in Terms of Causes, Effects and Solutions: A Case Study of NigeriaHuria MalikNo ratings yet

- MCS SyllabusDocument82 pagesMCS SyllabusAllan MarbaniangNo ratings yet

- The Birth Pains-15 Trends Mt.24.1-14 KBST08Document6 pagesThe Birth Pains-15 Trends Mt.24.1-14 KBST08mariel mendesNo ratings yet

- Fundamentals of Biomedical Science 1Document26 pagesFundamentals of Biomedical Science 1Annisa Hidayati Priyono100% (1)

- BSC Clinical Nutrition & DieteticsDocument29 pagesBSC Clinical Nutrition & Dieteticspb383336No ratings yet

- Under Fives ClinicDocument4 pagesUnder Fives ClinicJyoti SidhuNo ratings yet

- Millennium Development GoalsDocument60 pagesMillennium Development Goalsprogov08100% (7)

- Infographic PrintDocument1 pageInfographic PrintaulimirzaffNo ratings yet

- DLL - Mapeh 3 - Q1 - W3Document4 pagesDLL - Mapeh 3 - Q1 - W3daniel AguilarNo ratings yet

- POSHAN AbhiyaanDocument2 pagesPOSHAN AbhiyaanAnonymous x8MTGYUpNo ratings yet

- Community Health NutritionDocument31 pagesCommunity Health NutritionJosephNo ratings yet

- Lesson 9 WorksheetDocument4 pagesLesson 9 WorksheetMashaal FasihNo ratings yet

- ESPEN - Guideline On Clinical Nutrition in The Intensive Care Unit PDFDocument32 pagesESPEN - Guideline On Clinical Nutrition in The Intensive Care Unit PDFМаксим ДорошкевичNo ratings yet

- National Geographic USA 2014-12Document176 pagesNational Geographic USA 2014-12Ahmad Amir Azri60% (5)

- Samenvatting SL Semester 5Document137 pagesSamenvatting SL Semester 5J. Raja (Diëtist in opleiding)No ratings yet

- A List of Protein Deficiency DiseasesDocument2 pagesA List of Protein Deficiency DiseasesJoseph Uday Kiran MekalaNo ratings yet

- Transformational Business - Philippine Business Contributions To The Un SdgsDocument166 pagesTransformational Business - Philippine Business Contributions To The Un SdgsblackcholoNo ratings yet

- World Hunger (Tahiyem Fardales and Anahi LopezDocument18 pagesWorld Hunger (Tahiyem Fardales and Anahi LopeziporgeswNo ratings yet

- Lecture 11, Adolescent Health, Maternal & Child HealthDocument16 pagesLecture 11, Adolescent Health, Maternal & Child HealthHHGV JGYGUNo ratings yet

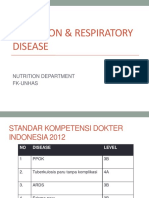

- Penatalaksanaan Gizi Sistem RespirasiDocument40 pagesPenatalaksanaan Gizi Sistem RespirasiElearning FK UnhasNo ratings yet

- Nutritional Status of Kurmi Adolescent Girls of RaipurDocument6 pagesNutritional Status of Kurmi Adolescent Girls of RaipurDevdan MahatoNo ratings yet

- Paediatric Protocols FinalDocument33 pagesPaediatric Protocols FinalAbdulkarim Mohamed AbdallaNo ratings yet