Professional Documents

Culture Documents

University of Petroleum and Energy Studies

University of Petroleum and Energy Studies

Uploaded by

Kush Agrawal0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

38 views10 pagesThis document is a student paper submitted to their professor on the topic of the international monetary crisis in Greece. It includes an acknowledgement, introduction, and first few chapters discussing the background of the Greek economy and causes of its financial crisis. The introduction provides an overview of Greece's economy and GDP statistics. Chapter 1 discusses the structure of Greece's economy and its classification. Chapters 2 and 3 examine the global financial crisis of 2007-2008 and Greece's subsequent government debt crisis. Chapter 4 outlines some of the key causes that deteriorated Greece's economic results, including issues with budget compliance, lower than expected GDP growth, growing government deficits and debt levels, and unreliable economic data.

Original Description:

project on iel

Original Title

Kush IEL

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentThis document is a student paper submitted to their professor on the topic of the international monetary crisis in Greece. It includes an acknowledgement, introduction, and first few chapters discussing the background of the Greek economy and causes of its financial crisis. The introduction provides an overview of Greece's economy and GDP statistics. Chapter 1 discusses the structure of Greece's economy and its classification. Chapters 2 and 3 examine the global financial crisis of 2007-2008 and Greece's subsequent government debt crisis. Chapter 4 outlines some of the key causes that deteriorated Greece's economic results, including issues with budget compliance, lower than expected GDP growth, growing government deficits and debt levels, and unreliable economic data.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Download as docx, pdf, or txt

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

38 views10 pagesUniversity of Petroleum and Energy Studies

University of Petroleum and Energy Studies

Uploaded by

Kush AgrawalThis document is a student paper submitted to their professor on the topic of the international monetary crisis in Greece. It includes an acknowledgement, introduction, and first few chapters discussing the background of the Greek economy and causes of its financial crisis. The introduction provides an overview of Greece's economy and GDP statistics. Chapter 1 discusses the structure of Greece's economy and its classification. Chapters 2 and 3 examine the global financial crisis of 2007-2008 and Greece's subsequent government debt crisis. Chapter 4 outlines some of the key causes that deteriorated Greece's economic results, including issues with budget compliance, lower than expected GDP growth, growing government deficits and debt levels, and unreliable economic data.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Download as docx, pdf, or txt

You are on page 1of 10

University Of Petroleum and Energy Studies,

College of Legal Studies,

Dehradun

International Economics Law Project

On the Topic

International Monetary Crisis in Greece

SUBMITTED TO: SUBMITTED BY:

MR. SUJITH P. SURENDRAN KUSH AGRAWAL

ASST. PROFESSOR B.A.LL.B., 9

TH

SEMESTER

COLLEGE OF LEGAL STUDIES SECTION A

DEHRADUN, U.K ROLL NO. - R450210063

SAP ID - 500012361

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

I would like to thank my esteemed and intellectual professor Mr. Sujith P.

Surendran (Faculty of International Economic Law) without whose support this

research paper would not have been successful. I am most grateful to him for

giving me his valuable time, experience and patience, and for providing me with

major inputs that have given focus to this report and sharpened our knowledge of

the subject.

I also put on record my gratitude towards the library staff, which provided me

access to all the resourceful material for my research.

Chapter 1

Introduction

The economy of Greece is the 34th or 42nd largest in the world at $299 or $304 billion by

nominal gross domestic product or purchasing power parity respectively, according to World

Bank statistics for the year 2011. Additionally, Greece is the 15th largest economy in the 27-

member European Union. In terms of per capita income, Greece is ranked 29th or 33rd in the

world at $27,875 and $27,624 for nominal GDP and purchasing power parity respectively.

A developed country, the economy of Greece mainly revolves around the service sector (85.0%)

and industry (12.0%), while agriculture makes up 3.0% of the national economic output.

Important Greek industries include tourism (with 14.9 million international tourists in 2009, it is

ranked as the 7th most visited country in the European Union and 16th in the world by the

United Nations World Tourism Organization) and merchant shipping (at 16.2% of the world's

total capacity, the Greek merchant marine is the largest in the world), while the country is also a

considerable agricultural producer (including fisheries) within the union. As the largest economy

in the Balkans, Greece is also an important regional investor.

The Greek economy is classified as an advanced and high-income one, and Greece was a

founding member of the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD)

and the Organization of the Black Sea Economic Cooperation (BSEC). In 1979 the accession of

the country in the European Communities and the single market was signed, and the process was

completed in 1982. In January 2011 Greece adopted the Euro as its currency, replacing the Greek

drachma at an exchange rate of 340.75 drachma to the Euro. Greece is also a member of the

International Monetary Fund and the World Trade Organization, and is ranked 31st on the KOF

Globalization Index for 2010 and 34th on the Ernst & Youngs Globalization Index 2011.

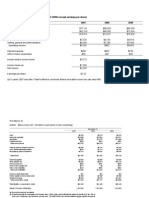

Combined charts of Greece's GDP and Debt since 1970; also of Deficit since 2000. Absolute terms time

series are in current euros.

The country's economy was devastated by the Second World War, and the high levels of economic

growth that followed throughout the 1950s to 1970s are dubbed the Greek economic miracle.

Since the turn of the millennium, Greece saw high levels of GDP growth above the Eurozone

average peaking at 5.9% in 2003 and 5.5% in 2006. Due to the late-2000s financial crisis and the

European sovereign debt crisis, the Greek economy saw growth rates of 7.1% in 2011, 4.9% in

2010, 3.1% in 2009 and 0.2% in 2008. In 2011, the country's public debt stood at 355.658

billion (170.6% of nominal GDP). After negotiating the biggest debt restructuring in history with

the private sector, Greece reduced its sovereign debt burden to 280 billion (136.9% of GDP) in

the first quarter of 2012.

Chapter 2

Financial Crisis of 2007-2008

The financial crisis of 20072008, also known as the global financial crisis and 2008 financial

crisis, is considered by many economists to be the worst financial crisis since the Great Depression

of the 1930s. It resulted in the threat of total collapse of large financial institutions, the bailout of

banks by national governments, and downturns in stock markets around the world. In many areas,

the housing market also suffered, resulting in evictions, foreclosures and prolonged

unemployment. The crisis played a significant role in the failure of key businesses, declines in

consumer wealth estimated in trillions of US dollars, and a downturn in economic activity leading

to the 20082012 global recession and contributing to the European sovereign-debt crisis. The

active phase of the crisis, which manifested as a liquidity crisis, can be dated from August 7, 2007,

when BNP Paribas terminated withdrawals from three hedge funds citing "a complete evaporation

of liquidity

Chapter 3

Greek Government Debt Crisis

The Greek government-debt crisis is one of a number of current European sovereign-debt crises

and is believed to have been caused by a combination of structural weaknesses of the Greek

economy coupled with the incomplete economic, tax and banking unification of the European

Monetary Union In late 2009, fears of a sovereign debt crisis developed among investors

concerning Greece's ability to meet its debt obligations due to strong increase in government

debt levels This led to a crisis of confidence, indicated by a widening of bond yield spreads and

the cost of risk insurance on credit default swaps compared to the other countries in the

Eurozone, most importantly Germany.

Graph:

Chapter 4

Causes for deteriorated economic

In January 2010 the Greek Ministry of Finance highlighted in their Stability and Growth

Program 2010 these five main causes for the significantly deteriorated economic results recorded

in 2009 (compared to the published budget figures ahead of the year):

Budget compliance: Budget compliance was acknowledged to be in strong need of future

improvement, and for 2009 it was even found to be "A lot worse than normal, due to economic

control being more lax in a year with political elections". In order to improve the level of budget

compliance for upcoming years, the Greek government wanted to implement a new reform to

strengthen the monitoring system in 2010, making it possible to keep better track on the future

developments of revenues and expenses, both at the governmental and local level.

GDP growth rates: After 2008, GDP growth rates were lower than the Greek national statistical

agency had anticipated. In the official report, the Greek ministry of finance reports the need for

implementing economic reforms to improve competitiveness, among others by reducing salaries

and bureaucracy, and the need to redirect much of its current governmental spending from non-

growth sectors (e.g. military) into growth stimulating sectors.

Government deficit: Huge fiscal imbalances developed during the past six years from 2004 to

2009, where "the output increased in nominal terms by 40%, while central government primary

expenditures increased by 87% against an increase of only 31% in tax revenues." In the report the

Greek Ministry of Finance states the aim to restore the fiscal balance of the public budget, by

implementing permanent real expenditure cuts (meaning expenditures are only allowed to grow

3.8% from 2009 to 2013, which is below the expected inflation at 6.9%), and with overall

revenues planned to grow 31.5% from 2009 to 2013, secured not only by new/higher taxes but

also by a major reform of the ineffective Tax Collection System.

Government debt-level: Since it had not been reduced during the good years with strong

economic growth, there was no room for the government to continue running large deficits in

2010, neither for the years ahead. Therefore, it was not enough for the government just to

implement the needed long term economic reforms, as the debt then rapidly would develop into

an unsustainable size, before the results of such reforms were achieved. The report highlights the

urgency to implement both permanent and temporary austerity measures that - in combination

with an expected return of positive GDP growth rates in 2011 - would result in the baseline deficit

decreasing from 30.6 billion in 2009 to only 5.6 billion in 2013, finally making it possible to

stabilize the debt-level relative to GDP at 120% in 2010 and 2011, followed by a downward trend

in 2012 and 2013.

Statistical credibility: Problems with unreliable data had existed ever since Greece applied for

membership of the Euro in 1999. In the five years from 20052009, Eurostat each year noted a

reservation about the fiscal statistical numbers for Greece, and too often previously reported

figures got revised to a somewhat worse figure, after a couple of years. In regards of 2009 the

flawed statistics made it impossible to predict accurate numbers for GDP growth, budget deficit

and the public debt; which by the end of the year all turned out to be far worse than originally

anticipated. In 2010, the Greek ministry of finance reported the need to restore the trust among

financial investors, and to correct previous statistical methodological issues, "by making the

National Statistics Service an independent legal entity and phasing in, during the first quarter of

2010, all the necessary checks and balances that will improve the accuracy and reporting of fiscal

statistics".

The downgrading of Greek government debt to junk bond status in April 2010 created alarm in

financial markets, with bond yields rising so high, that private capital markets practically were no

longer available for Greece as a funding source. On 2 May 2010, the Eurozone countries and the

International Monetary Fund (IMF) agreed on a 110 bailout loan for Greece, conditional on

compliance with the following three key points:

Implementation of austerity measures, to restore the fiscal balance.

Privatisation of government assets worth 50bn by the end of 2015, to keep the debt pile

sustainable.

Implementation of outlined structural reforms, to improve competitiveness and growth

prospect

You might also like

- Chap 06Document30 pagesChap 06Tim JamesNo ratings yet

- MT799 Deutsche Bank To Standard Chartred PK - 1Document1 pageMT799 Deutsche Bank To Standard Chartred PK - 1pejman mashhadianNo ratings yet

- FinQuiz Level2Mock2016Version4JunePMQuestionsDocument40 pagesFinQuiz Level2Mock2016Version4JunePMQuestionsAjoy RamananNo ratings yet

- International Commercial ClaimDocument14 pagesInternational Commercial Claimjoe100% (1)

- Fromagerie Bel AnalyseDocument41 pagesFromagerie Bel AnalyseMichaelCaroNo ratings yet

- François Chesnais-Finance Capital Today-Brill (2016)Document154 pagesFrançois Chesnais-Finance Capital Today-Brill (2016)Caio BugiatoNo ratings yet

- Greece Crisis and Impact: Dr. P.A.JohnsonDocument14 pagesGreece Crisis and Impact: Dr. P.A.JohnsonPrajwal KumarNo ratings yet

- The Greek Economy and The Potential For Green Development: George PagoulatosDocument10 pagesThe Greek Economy and The Potential For Green Development: George PagoulatosAngelos GkinisNo ratings yet

- LEVY Inst. PN 12 11Document5 pagesLEVY Inst. PN 12 11glamisNo ratings yet

- Greece Financial CrisisDocument11 pagesGreece Financial CrisisFadhili KiyaoNo ratings yet

- Forex Management-Greece CrisisDocument17 pagesForex Management-Greece CrisisNidhi DoshiNo ratings yet

- Offshore FullDocument12 pagesOffshore FullGana PathyNo ratings yet

- Greek Debt CrisisDocument11 pagesGreek Debt CrisisISHITA GROVERNo ratings yet

- Greece Crisis ExplainedDocument14 pagesGreece Crisis ExplainedAshish DuttNo ratings yet

- Bank of GreeceDocument3 pagesBank of GreeceAngelos GkinisNo ratings yet

- Greece Crisis Greece Crisis: A Tale of Misfortune A Tale of MisfortuneDocument14 pagesGreece Crisis Greece Crisis: A Tale of Misfortune A Tale of MisfortuneSmeet ShahNo ratings yet

- The Greek - Sovereign Debt CrisisDocument13 pagesThe Greek - Sovereign Debt Crisischakri5555No ratings yet

- 15 Budget DeficitDocument5 pages15 Budget Deficitthreestars41220027340No ratings yet

- Ten Rays of Light in The Greek Crisis: Nick MalkoutzisDocument16 pagesTen Rays of Light in The Greek Crisis: Nick MalkoutzisnaetnaltaNo ratings yet

- Global & Macroeconomic Environment Assignment-V2Document17 pagesGlobal & Macroeconomic Environment Assignment-V2ranjanNo ratings yet

- The Greek Crisis: Causes and Implications: ArticleDocument15 pagesThe Greek Crisis: Causes and Implications: ArticleArpit BharadwajNo ratings yet

- Criticart - Young Artists in Emergency: Chapter 1: World Economic Crisis of 2007-2008Document17 pagesCriticart - Young Artists in Emergency: Chapter 1: World Economic Crisis of 2007-2008Oana AndreiNo ratings yet

- Eurozone Implication 1Document25 pagesEurozone Implication 1JJ Amanda ChenNo ratings yet

- Greec Crisis Causes&ImplicationDocument9 pagesGreec Crisis Causes&Implicationshubh_sumanNo ratings yet

- The Exit DilemmaDocument10 pagesThe Exit DilemmaOla OlaNo ratings yet

- Causes and Consequences of The Spanish Economic Crisis - University of Minho Portugal EssayDocument20 pagesCauses and Consequences of The Spanish Economic Crisis - University of Minho Portugal EssayMichael KNo ratings yet

- Portugal & The Eurozone Crises Project By: Akash Saxena Gaurav Mohan Aditya ChaudharyDocument15 pagesPortugal & The Eurozone Crises Project By: Akash Saxena Gaurav Mohan Aditya ChaudharyAkash SaxenaNo ratings yet

- Greek Financial Crisis May 2011Document5 pagesGreek Financial Crisis May 2011Marco Antonio RaviniNo ratings yet

- Hardouvelis Gkonis Cyprus Vs Greece's EconomyDocument38 pagesHardouvelis Gkonis Cyprus Vs Greece's EconomyLeonardo SimonciniNo ratings yet

- National Law Institute University: Greek Sovereign Debt CrisisDocument15 pagesNational Law Institute University: Greek Sovereign Debt Crisisalok mishraNo ratings yet

- I. Introduction To The Country: Geography, Location, AreaDocument6 pagesI. Introduction To The Country: Geography, Location, AreaAbdulMalik Al BalushiNo ratings yet

- Debt Crisis in GreeceDocument6 pagesDebt Crisis in Greeceprachiti_priyuNo ratings yet

- Kouretas: The Greek Debt Crisis: Origins and ImplicationsDocument12 pagesKouretas: The Greek Debt Crisis: Origins and ImplicationsRainer TsufallNo ratings yet

- Has Austerity Failed in EuropeDocument3 pagesHas Austerity Failed in EuropeAndreea WeissNo ratings yet

- Greek Debt Crisis: How It StartedDocument3 pagesGreek Debt Crisis: How It StartedHidden TalentzNo ratings yet

- Greek CrisesDocument10 pagesGreek CrisesManasakis KostasNo ratings yet

- Greeces Global EconomyDocument11 pagesGreeces Global Economyapi-165369565No ratings yet

- Greek Financial CrisisDocument5 pagesGreek Financial CrisisRomiBHartartoNo ratings yet

- Country Strategy 2011-2014 GreeceDocument19 pagesCountry Strategy 2011-2014 GreeceBeeHoofNo ratings yet

- Paper - The Fiscal Crisis in Europe - 01Document9 pagesPaper - The Fiscal Crisis in Europe - 01290105No ratings yet

- Contagious Effects of Greece Crisis On Euro-Zone StatesDocument10 pagesContagious Effects of Greece Crisis On Euro-Zone StatesSidra MukhtarNo ratings yet

- Greek RestructuringDocument8 pagesGreek RestructuringSeven LoveNo ratings yet

- Where Did The Greek Bailout Money Go?: ESMT White PaperDocument24 pagesWhere Did The Greek Bailout Money Go?: ESMT White PapersunrababNo ratings yet

- Introduction To European Sovereign Debt CrisisDocument8 pagesIntroduction To European Sovereign Debt CrisisVinay ArtwaniNo ratings yet

- Resolving The European Debt Crisis (English)Document8 pagesResolving The European Debt Crisis (English)Vangelis TselentisNo ratings yet

- International Financial ManagementDocument47 pagesInternational Financial ManagementAshish PriyadarshiNo ratings yet

- A Project Report in EepDocument10 pagesA Project Report in EepRakesh ChaurasiyaNo ratings yet

- Ten Questions On Greek CrisisDocument7 pagesTen Questions On Greek CrisisDimitrisNo ratings yet

- The Chronicle of The Great CrisisDocument244 pagesThe Chronicle of The Great CrisisPanagiotis DoulosNo ratings yet

- Greek Debt CrisisDocument22 pagesGreek Debt CrisisJessNo ratings yet

- Greek Debt Crisis "An Introduction To The Economic Effects of Austerity"Document19 pagesGreek Debt Crisis "An Introduction To The Economic Effects of Austerity"Shikha ShuklaNo ratings yet

- The Effect of Global Crisis Into Euro Region: A Case Study of Greek CrisisDocument6 pagesThe Effect of Global Crisis Into Euro Region: A Case Study of Greek CrisisujjwalenigmaNo ratings yet

- Economic Crisis in GreeceDocument25 pagesEconomic Crisis in GreeceDimitris RoutosNo ratings yet

- Govt Debt and DeficitDocument4 pagesGovt Debt and DeficitSiddharth TiwariNo ratings yet

- The Financial Crisis in Greece and Its Impacts On Western Balkan CountriesDocument13 pagesThe Financial Crisis in Greece and Its Impacts On Western Balkan CountriesUtkuNo ratings yet

- Greece Economic CrisisDocument32 pagesGreece Economic CrisisJOANNA ANGELA INGCONo ratings yet

- Project Objectives and Scope: ObjectiveDocument77 pagesProject Objectives and Scope: Objectivesupriya patekarNo ratings yet

- Post 25 JanDocument8 pagesPost 25 JanMohammad Salah RagabNo ratings yet

- Econ 0309Document110 pagesEcon 0309droth1No ratings yet

- Interview For El ConfidentialDocument9 pagesInterview For El ConfidentialsmavroNo ratings yet

- Greece Country Strategy 2007-2010: Black Sea Trade and Development BankDocument18 pagesGreece Country Strategy 2007-2010: Black Sea Trade and Development BanklebenikosNo ratings yet

- The Financial Crisis in Greece and Its Impacts On Western Balkan CountriesDocument13 pagesThe Financial Crisis in Greece and Its Impacts On Western Balkan CountriesPrajwal KumarNo ratings yet

- Plan C - Shaping Up To Slow GrowthDocument11 pagesPlan C - Shaping Up To Slow GrowthThe RSANo ratings yet

- Project ReportDocument5 pagesProject Reportkian kashefiNo ratings yet

- EIB Investment Report 2021/2022 - Key findings: Recovery as a springboard for changeFrom EverandEIB Investment Report 2021/2022 - Key findings: Recovery as a springboard for changeNo ratings yet

- University of PetroleumDocument15 pagesUniversity of PetroleumKush AgrawalNo ratings yet

- UNIT 3hedonismDocument25 pagesUNIT 3hedonismKush AgrawalNo ratings yet

- DishankDocument6 pagesDishankKush AgrawalNo ratings yet

- Gupta EmpireDocument37 pagesGupta EmpireKush Agrawal0% (1)

- University of Petroleum & Energy StudiesDocument18 pagesUniversity of Petroleum & Energy StudiesKush AgrawalNo ratings yet

- DefamationDocument14 pagesDefamationTanya Tandon33% (3)

- Country Risk Analysis Egypt Information 1Document46 pagesCountry Risk Analysis Egypt Information 1kateNo ratings yet

- Pet Care - Trends and Insights Across Europe (November 2012)Document37 pagesPet Care - Trends and Insights Across Europe (November 2012)IRIworldwideNo ratings yet

- Covered Interest ArbitrageDocument7 pagesCovered Interest Arbitrageakeila3No ratings yet

- Flash Memory Inc Student Spreadsheet SupplementDocument5 pagesFlash Memory Inc Student Spreadsheet Supplementjamn1979No ratings yet

- MT Examination FSA 2014Document4 pagesMT Examination FSA 2014Himanshu KumarNo ratings yet

- Jawaban Uas B.ingDocument3 pagesJawaban Uas B.ingAndry WigunaNo ratings yet

- Sodexo Results FY2011Document23 pagesSodexo Results FY2011SaurabhNo ratings yet

- 2-4 2004 Jun QDocument11 pages2-4 2004 Jun QAjay TakiarNo ratings yet

- Comisia Europeana 2023 - 07 - 24 - With - Taxes - 2161Document8 pagesComisia Europeana 2023 - 07 - 24 - With - Taxes - 2161Gandul.infoNo ratings yet

- V 13 I 30Document37 pagesV 13 I 30Riswan FadhilahNo ratings yet

- Pic Activity 1Document7 pagesPic Activity 1ParameshNo ratings yet

- CEMEX AnalysisDocument9 pagesCEMEX AnalysisJeff Ray SanchezNo ratings yet

- REPORT ON THE AFFAIRS OF PHONEIX VETURE HOLDINGS LIMETED, MG ROVER GROUP LIMETED AND 33 OTHER COMPANIES VOLUME IiDocument459 pagesREPORT ON THE AFFAIRS OF PHONEIX VETURE HOLDINGS LIMETED, MG ROVER GROUP LIMETED AND 33 OTHER COMPANIES VOLUME IiepqprojectlcNo ratings yet

- FIZZ 2001 Annual - ReportDocument38 pagesFIZZ 2001 Annual - ReportSteveMastersNo ratings yet

- Betty BotterDocument3 pagesBetty BotterAnna BorkowskaNo ratings yet

- Take Home Exercises 1Document4 pagesTake Home Exercises 1AchefNo ratings yet

- R21 Currency Exchange Rates IFT NotesDocument35 pagesR21 Currency Exchange Rates IFT NotesMohammad Jubayer AhmedNo ratings yet

- Advanced Accounting Baker Test Bank - Chap012Document67 pagesAdvanced Accounting Baker Test Bank - Chap012donkazotey50% (2)

- GCC Retail Industry Report 2012 - 9 December 2012Document80 pagesGCC Retail Industry Report 2012 - 9 December 2012aakashblueNo ratings yet

- CatDocument95 pagesCatAmit NarkarNo ratings yet

- Advanced Financial Management: Tuesday 2 December 2014Document12 pagesAdvanced Financial Management: Tuesday 2 December 2014iram2005No ratings yet

- Annual Report 2011-12: Planning Commission Government of India WWW - Planningcommission.gov - inDocument213 pagesAnnual Report 2011-12: Planning Commission Government of India WWW - Planningcommission.gov - inRaghuNo ratings yet

- Ch02 Asset Classes and Financial InstrumentsDocument39 pagesCh02 Asset Classes and Financial InstrumentsA_StudentsNo ratings yet

- Chapter 4Document14 pagesChapter 4Selena JungNo ratings yet