Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Public-Private Partnerships and The Small Schools PDF

Public-Private Partnerships and The Small Schools PDF

Uploaded by

Hneriana HneryOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Public-Private Partnerships and The Small Schools PDF

Public-Private Partnerships and The Small Schools PDF

Uploaded by

Hneriana HneryCopyright:

Available Formats

Sponsoring Committee: Professor Janelle T.

Scott, Chairperson

Professor Gary L. Anderson

Professor Leslie Santee Siskin

PUBLIC-PRIVATE PARTNERSHIPS AND THE SMALL SCHOOLS

MOVEMENT: A NEW FORM OF EDUCATION MANAGEMENT

Catherine Comstock DiMartino

Program in Educational Leadership

Department of Administration, Leadership and Technology

Submitted in partial fulfillment

of the requi rement s for the degree of

Doctor of Philosophy in the

Steinhardt School of Culture, Education, and Human Development

New York University

2009

UMI Number: 3346262

Copyright 2009 by

DiMartino, Catherine Comstock

All rights reserved.

INFORMATION TO USERS

The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy

submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and

photographs, print bleed-through, substandard margins, and improper

alignment can adversely affect reproduction.

In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript

and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized

copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion.

UMI

UMI Microform 3346262

Copyright 2009 by ProQuest LLC.

All rights reserved. This microform edition is protected against

unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code.

ProQuest LLC

789 E. Eisenhower Parkway

PO Box 1346

Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346

Copyright 2009 Catherine Comstock DiMartino

I hereby guarantee that no part of the dissertation which I have submitted for

publication has been heretofore published and/or copyrighted in the United

States of America, except in the case of passages quoted from other

published sources; that I am the sole author and proprietor of said

dissertation; that the dissertation contains no matter which, if published, will

be libelous or otherwise injurious, or infringe in any way the copyright of

any other party; and that I will defend, indemnify and hold harmless New

York University against all suits and proceedings which may be brought and

against all claims which may be made against New York University by

reason of the publication of said dissertation.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I am grateful to all of the individuals-principals, teachers, parents,

members of intermediary organizations and district officials-who participated in

this study. They generously opened their schools and offices, and shared their

experiences with me.

At NYU, my dissertation advisor, committee members and informal

mentors provided me with critical guidance and support. I drew inspiration from

Janelle Scott whose commitment to educational equity and intellectual rigor

constantly pushed me to think in new ways and deeply influenced my evolution as

an educational researcher. I feel fortunate to have had her as a teacher, advisor

and mentor. A special thank you to Gary Anderson who has supported my

doctoral pursuits in many ways, from finding me space to work on my dissertation

to offering sage advice about my next professional steps. His commitment to

students' intellectual growth and development exemplifies good teaching and

reminds me, through his example, the great importance of sharing knowledge and

experience. I have also benefitted from the wisdom of Leslie Santee Siskin whose

interest in and support of my work shaped this dissertation and who in her

creation of the High School Group, created a community of scholars with whom I

could share ideas. A special thank you goes to Mary Driscoll, who was the first

professor I met at NYU. I am grateful for your good counsel and our

conversations that span topics ranging from aviaries to roses. Last, but not least,

iii

to Elaine Chugranismy fellow doctoral studentyour great sense of humor and

unending generosity in explaining the whole dissertation process helped pull me

through!

My studies at NYU would not have been possible without the support of

Dean Patricia Cary and the Office of Student Services. In addition to funding me

for three years as a graduate assistant, members of the office, especially Jeanne

Bannon, Doris Alcivar and Nancy Hall, provided me with excellent advice as well

as many laughs.

At RAND, a special thank you goes to Team NYC who modeled the

practice of policy research and whose members offered invaluable support and

advice about the dissertation process.

To mom and dad who taught me the value of education and who always

urged me go for the gold! Thank you. A special thank you to my mom who

always encouraged me to pursue work that I believe in and that serves a greater

good. Finally, to Daniel Blanco my partner, best friend, fellow adventurer and

editor extraordinaire. Thank you for your unconditional love, support and

encouragement throughout this entire process; your positive energy and calming

presence helped me to complete this journey.

IV

TABLE OF CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS iii

LIST OF TABLES ix

LIST OF FIGURES x

CHAPTER

I THE USE OF INTERMEDIARY ORGANIZATIONS TO

REFORM PUBLIC EDUCATION 1

Introduction 1

Purpose and Rationale 6

Research Questions 8

Political and Economic Context: A National Perspective 9

Political and Economic Context: A Local Perspective 13

Building an Educational Marketplace 14

Partnering with the Private Sector to Run "Not a Great

School System, but a System of Great Schools" 15

New Accountability Mechanisms 16

The Emergence of Intermediary Organizations 17

An Introduction to the Findings 19

Dissertation Overview 21

Conclusion 22

II FRAMING HYBRID SCHOOLS: CONCEPTUALIZING

THE INTERSECTION OF EDUCATIONAL VALUES

AND POWER 24

Introduction 24

The Politics of Hybrid Schools: Crossing Sector Boundaries,

Exchanging Values and Negotiating Power 25

The Politics of Power and Control 30

The Spectrum of Control 32

Conclusion 37

continued

v

Ill REVIEW OF LITERATURE

38

Introduction 38

Motivation and Contextual Factors that Impact

Cross-Sectoral Partnerships 39

Legal, Financial, Political, and Organizational

Incentives 39

Partnering Factors 45

The Distribution of Power and Its Impact on Governance

within Joint Ventures 52

Distribution of Power 52

How Success is Measured, Sustained and Replicated

within Inter-Organizational Relationships 59

Measuring Outcomes 60

Sustainability and Scaling Up 61

Conclusion and Implications 64

IV METHODOLOGY 66

Introduction 66

Research Questions 66

Research Design 67

Sample Selection 70

Intermediary Organizations 71

School Samples 73

Data Collection 75

Identifying and Recruiting Study Participants 76

Data Sources 78

Data Analysis 83

Coding 83

Role of Researcher 86

Conclusion 87

V THE CASE OF EXCELSIOR ACADEMY: A

UNIVERSITY EDGE SCHOOL 89

Overview of the Case 89

Part I: Contextual Factors that Impact

Public-Private Ventures 91

The Partnership Quest: Alignment and Association 91

An Introduction to the University Edge and its

School Design Model 94

continued

VI

School Acceptance, Placement and Regional Support 97

Teacher Motivations for Choosing Excelsior 98

Parent Motivations for Choosing Excelsior 102

Admissions Procedures and Student

Selection Processes 103

Part II: Decision Making Processes 110

The Partnership in Action: Personnel, Curricular,

and Professional Development Decisions 114

Part III: Sustainability and Scaling Up 126

Leaving Before Year Four: Teacher Attrition

at Excelsior 126

Parents' Dream Making and Breaking Experiences 128

University Edge: Scaling Up 129

Excelsior Academy: An Uncertain Future 131

Discussion and Conclusion 132

VI THE CASE OF METROPOLITAN UNITED

ENTREPRENEURSfflP AND CITIZENSHIP

ACADEMY 136

Overview of the Case 136

Part I: Contextual Factors that Impacted

The Partnership 137

The Partnership Quest: A Speedy Union 137

From Partner to Manager: An Introduction

to Metropolitan United 140

Teachers Motivations for Choosing ECA 147

Parent Motivations for Choosing ECA 150

Student Characteristics and Selectivity 151

Part II: Decision-Making Processes 154

Decision-Making Processes: Personnel and Budget 155

Decision-Making Processes: Teaching and Learning 158

Part III: The Dissolution of the Partnership 166

Poor Interactions 167

New York City Department of Education Response 170

The School and Community's Response to the Break 172

Post Break-Up: Settling Accounts and

Changi ng Names 172

Part IV: Sustainability and Scaling Up 175

The Post Break Experience: Metropolitan United 175

continued

vn

The Post Break Experience: Entrepreneurship and

Citizenship Academy 177

The Post Break Experience: Parents' Hopes and

Goals for Schooling 177

Discussion and Conclusion 178

VII CROSS CASE ANALYSIS AND CONCLUSION 180

Introduction and Overview of the Study 180

Micro-Politics of Partnerships 183

Parameters of Power: The Spectrum of

Control Revisited 183

Contextual Factors that Impact and Influence

the Partnership 188

The Competing Public and Private Goals Inherent

in Cross-Sectoral Collaborations 194

The Macro-Politics of Current School Reform 197

Implications for Research, and Policy Recommendations 200

Implications for Research 200

Policy Recommendations 203

Conclusion - 207

BIBLIOGRAPHY 210

APPENDICES 220

A INTERVIEW PROTOCOLS 220

B OBSERVATION PROTOCOL 228

C DOCUMENT REVIEW PROTOCOL 229

V1H

LIST OF TABLES

1 Descriptions of Intermediary Organizations 72

2 Descriptions of Case Study Schools (2006-2007) 74

3 Total Individuals Interviewed at Excelsior Academy: A University

Edge School and at University Edge 80

4 Total Individuals Interviewed at Entrepreneurship and Citizenship

Academy and at Metropolitan United 80

5 Total Individuals Interviewed at District 80

6 University Edge School Design Model 96

7 Teacher Demographics, Experience and Retention Data at Excelsior 101

8 Metropolitan United's Principles Pre-Management Contract 141

9 Teacher Demographics and Experience at Entrepreneurship and

Citizenship Academy 149

IX

LIST OF FIGURES

1 Flow of Resources between Foundation, Intermediary, Schools

and the New York City Department of Education 5

2 Spectrum of Control 34

3 Spectrum of Control 184

x

CHAPTER I

THE USE OF INTERMEDIARY ORGANIZATIONS TO

REFORM PUBLIC EDUCATION

Introduction

While reports of school vouchers and educational management

organizations (EMOs) hold the media's and public's attention, subtler, but no less

important, privatization initiatives have taken root in some of the largest urban

districts across the United States. This new privatization

1

, often coupled with

mayoral takeover of school systems, school choice initiatives, and increased

accountability, encourages unprecedented reliance on the private sector to provide

educational services at all levels. Within the Department of Education (DOE) in

New York City, for example, private consulting firms make policy

recommendations, while at the school level, private organizations are regularly

co-founding new small schools. This dissertation focuses on the emergence of

intermediary organizations as partners to new small schools in New York City.

Using two case studies of new small schools co-founded by an intermediary

organization and the New York City Department of Education (NYC DOE), this

study exami nes decision-makinga key area around which partners and school s

In this dissertation, privatization is defined as "the act of reducing the role of government, or

increasing the role of the private sector, in an activity or in the ownership of assets" (Savas, 1987,

P-3).

1

negotiate power

2

. In particular, this study explores how partners and school-

based stakeholders make decisions over personnel, budgets, curricula,

professional development and admissions processes.

The use of public-private partnerships is not new; private sector

contracting has a long history in public education. However, the founding and

running of schools by private sector organizations is a more recent phenomenon

(Colby, Smith & Shelton, 2005; Gold, Christman & Herold, 2007; Miron &

Nelson, 2002; Richards, Shore & Sawicky, 1996). Fueled by neoliberal ideology

which argues that markets and consumer choice create more effective and better

quality public schools (Chubb and Moe, 1990; Friedman, 1962), the influence of

these perspectives on policymakers, in concert with the decreased role of federal

and local governments in social services, has led to the reconceptualization of

how educational services are delivered. This vision involves replacing publicly

funded and run educational services with public-private partnerships or entirely

private organizations (Chubb & Moe, 1990; Handler, 1996; Minow, 2002).

Similarly, small schools are not new to public education; they have often

functioned on the periphery of the school system, residing in rural areas and in

alternative superintendencies where, with exceptions, they educate "at-risk" or

second chance students (Lief, 2001; Raywid & Schmerler, 2003). In New York

City, progressive and equity minded educators have often been key leaders in the

2

In this dissertation, the term power refers to the ability of an individual or group, as defined by

Max Weber, "to realize their own will in a communal action even against the resistance of others

who are participating in the action" (Gerth & Mills, 1946. p. 180).

2

small schools reform movement (Meier, 1995). The current iteration of the small

schools movement

3

; however, seeks to pull schools from the periphery to the

norm. These new small schools are being created by a colorful mix of school

transformers, including progressive educators, standardized test developers,

Hispanic rights organizers and former real estate developers. Spurred by

foundational and federal funding, new small schools have been created in city

systems across the nation. In the current privatization and small schools

4

movements, schools are co-founded by local departments of education and private

sector organizations, called intermediaries (AIR, 2003, Heubner, 2005, NYC

DOE, 2007). Proponents of privatization posit that these organizations will use

their outsider status and experience to access personal and professional networks

that will spark innovation in the public school system. This use of intermediary

organizations to co-found and run new small schools reflects both the current

neoliberal ideology as well as the diversity of educational values driving school

founders (Kafka, 2008).

In addition to championing the expansion of private sectors players in

public education, neoliberals have pushed for increased use of choice and markets

to improve educational outcomes. Particular to the new small schools movement,

This study will focus on small school creation in New York City. Other large cities, such as

Chicago and Boston, also received significant funds from the Annenberg Challenge and currently

the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation to implement small school reform.

4

While many of these schools are high schools (9-12), some include both middle and high school

age students (6-12). On the NYC DOE website, it defines small as schools enrolling 500 or fewer

students.

3

policymakers seek to provide consumer choice to parents and students, and to

infuse market competition within urban districts, whose large comprehensive high

schools have come under criticism for fostering poor learning environments, low

daily attendance and abysmal graduation rates (Angus & Mirel, 1999; Huebner,

2005). In contrast, detractors of privatization caution that the addition of private

sector actors will alter the relationship between government and citizens,

potentially reallocating power away from citizens and toward an amalgam of

interest groups and stakeholders (Ball, 2007; Handler, 1996; Scott and DiMartino,

2009a).

Intermediary Organizations and New York City

Since 2003, over 260 small schools have opened in New York City (NYC

DOE, 2008). The majority of these schools have been founded by the Department

of Education in partnership with an intermediary organization such as New

Visions for Public Schools, Replications, Inc., The Urban Assembly, and The

College Board (NYC DOE, 2007). Intermediaries receive funding to co-found

and support new small public secondary schools from foundations, who also

sometimes donate directly to districts. For example, in 2005, the Bill and Melinda

Gates Foundation gave $11,850,000 to the intermediary College Board (Bill and

Mel i nda Gat es Foundat i on, n. d). In exchange, foundations expect intermediaries

to assist in launching new small schools, but also to refine their models or core

principles so that they can be replicated. Intermediaries, for their part, leverage

4

this funding to provide start-up support during the first four years of a school's

existence. The amount depends on the intermediary, ranging from $400,000 to

$575,000 dollars, or about 10% of what the district provides to each school.

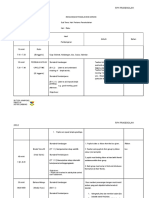

Refer to figure 1 for a graphic representation of the foundation-intermediary-

school-New York City Department of Education relationship.

Figure 1. Flow of Resources between Foundation, Intermediary Schools and the

New York City Department of Education.

As figure 1 illustrates, foundations allocate significant funding directly to

intermediaries. Intermediaries, for their part, "sell" their solutions to the call for

educational reform in order to attract foundational funding. The intermediary

then provides its own funding contribution to schools in the form of a partnership,

with the implicit assertion that this association will lead to better outcomes in how

the school is run. Given the current policy context, and in ideological agreement

with this new privatization led-reform, the NYC DOE has also made decisions to

decentralize decision making by shifting more funding to the school level. The

5

idea is to give principals greater authority over day-to-day decision making, while

holding them to greater accountability via an array of new measurement

mechanisms. The theory is that principals will be empowered to better serve the

needs of their local communities, just as parents will be empowered to choose

among a marketplace of options for schools that best meet the needs of their

children.

Purpose and Rationale

This study examines the politics of cross-sectoral partnerships in the

current iteration of the small schools movement in New York City. It explores

how various actors' values, beliefs and goals for schooling influence school

decision-making processes in terms of teaching, learning, and leadership. Case

study methodology reveals how this new approach to school governance affects

the experiences of principals and teachers working in schools, students who attend

them, and the members of intermediary organizations with whom the schools are

partnered. Handler (1996) suggests that answering questions of governance

requires indicators such as "attendance, participation, control of agenda, how the

decisions are made (for example, voting, consensus), who prevails, how often, for

what kinds of issues and the substantive decisions that are actually made" (p.

222).

The findings from this dissertation will help policymakers and

practitioners understand the complexities of public-private partnerships and to

6

avoid pitfalls that arise from this new paradigm. In addition, this work places

intermediary organizations within the larger field of private sector organizations

that support and manage public schools. This is particularly important because

earlier studies of intermediaries (Honig, 2004) strictly defined them as

"organizations that occupy the space in between at least two other parties.

Intermediary organizations primarily function to mediate or to manage change in

both parties" (p. 67). While the intermediary organizations studied for this

dissertation occupied space "in between" two parties, they were not designed to

"mediate' or "manage" change in both parties. This distinction is significant as

the theory behind this reform was for the Bill and Melinda Gates funded

intermediaries to catalyze change on the school side, not on the foundation side.

Therefore, these intermediaries more closely resemble New American Schools'

design teams, charter school management companies (CMOs) or EMOs (Berends,

Bodilly & Kirby, 2002; Bulkley, 2005; Horn & Miron, 2000; Miron & Nelson,

2002; Scott, 2002; Scott and DiMartino, 2009b).

Rather than looking at the intermediary construct from a mutually

mediating perspective, this dissertation focuses on how the addition of a private

sector actor impacts power sharing and decision-making among local school

stakeholders-with special focus on principals and teachers. Building on the work

of Col by, Smi t h and Shelton (2005), and Scott and Di Mart i no (2009b), this st udy

seeks to understand the role of intermediary organizations within the current push

7

for private sector involvement in public education. Having defined the goals of

this study, the research questions follow.

Research Questions

The crossing of boundaries between private and public sector

organizations raises important questions about the politics of cross-sectoral

partnerships in the new small schools movement. The following questions

5

guide

this study:

1) What motivates public school principals and intermediary organizations to

partner to create and run a school?

2) What are the values, beliefs and goals for schooling that drive members of

public small school communities-including principals, teachers, parents

and members of intermediary organizations?

3) What are the central issues around which public small school communities

experience conflict, cooperation and the process of negotiation?

Having introduced the purpose and rational for this dissertation as well as

the guiding research questions, the next section contextualizes the research by

locating these small school partnerships within larger political, economi c and

historical contexts both nationally and in New York City.

Concepts and questions have been influenced by Scott, J. (2002). Privatization, charter school

reform, and the search for educational empowerment.

8

Political and Economic Context: A National Perspective

Throughout the history of schooling, policymakers and practitioners have

made various policies in their quest for improved learning outcomes in high

schools. While some of these recommendations have focused on school size,

others have focused on curriculum and standards. Still others have examined

subject departments, the primary organization unit of high schools (Angus &

Mirel, 1999; Conant, 1959; Lee & Smith, 1997; Marsh & Codding, 1999; Siskin

& Warren, 1995). Recognizing this long history of working to improve high

schools, this section addresses why the use of public-private partnerships arose

during this particular political and economic climate.

The publication of A Nation at Risk in 1983 and other policy studies in the

1980s heavily critiqued the state of public education. Spurred by the fear that,

"the educational foundations of our society are presently being eroded by a rising

tide of mediocrity and threatening our very future as a nation" (A Nation at Risk,

1983, p. 1) citizens, the government, educators, the business community, and

foundations turned their focus to school reform. Tyack and Cuban (1995)

comment, "A Nation at Risk was only one of many elite policy commissions of

the 1980s that declared that faulty schooling was eroding the economy and that

the remedy for both educational and economic decline was improving academic

achievement" (p. 34). This critique of the American public education system in

the 1980s coincided with changing conceptions of the role of government in

society. In contrast to the welfare state which supported programs such as

9

Lyndon Johnson's Great Society plan, the post-welfare state, in which neoliberal,

neoconservative and conservative ideology dominate, champions the reduction of

government and an increased reliance on privatization, markets, and consumer

choice (Friedman, 1962, Chubb and Moe, 1990). Gewirtz (2002) describes this

change: "in the post-welfarist era the formal commitments to Keynesian

economics and distributive justice were dropped and replaced by formal

commitments to market 'democracy' and competitive individualism" (p. 2).

Within this political and economic context, ideas expressed by market

reformers, notably Milton Friedman (1962) in Capitalism and Freedom, and

Chubb and Moe (1990) in Politics, Markets and America's Schools, became

influential with educational policymakers as a means to improve public schools,

most notably through charter schools and voucher systems. Friedman argued that

the role of government should be severely limited and that "the role of

government just considered is to do something that the market cannot do for itself,

namely, to determine, arbitrate and enforce the rules of the game" (p. 27). In his

view, limiting the role of government by means of privatizing former government

entities opens up a marketplace of options for people. In this environment,

individual freedom of choice would be maximized. In addition, competition,

induced by the newly created marketplace, would compel schools to be run more

efficiently and effectively (p. 32). Fri edman champi oned government removi ng

itself from running schools and instead promoted "private enterprises operated by

for-profit, or by non-profit institutions" delivering educational services (p. 89).

10

To this end, government would require "certain minimal standards," involving

content and attendance requirements, but otherwise a variety of self-governing

independent schools would exist.

Chubb and Moe (1990) use Friedman's ideas and apply them directly to

schooling in a post A Nation at Risk policy environment. They argue that public

schools are ineffective bureaucracies and must be replaced with privately

managed institutions, which would then compete with each other for students.

Chubb and Moe advocate removing the governance of public education from the

public to the private sphere. They explain:

Markets offer an institutional alternative to direct democratic

control. They are not built around the exercise of public authority,

but rather around school competition and parent-student choice

which.. .tend through their natural operation to discourage

bureaucratic forms of organization and to promote the

development of autonomy, professionalism, and other traits

associated with effective schooling (p. 167).

Chubb and Moe call for removing the creation and running of schools from the

public "democratic" sphere to the private. They posit this would create an

improved model that would be more responsive to the demands of the consumer.

At the same time as policymakers and practitioners were pushing for

decentralization, deregulation, and increased privatization, systemic reform was

also becoming an increasingly popular approach to improving educational

out comes. Syst emi c reform pushed for an end to incremental changes to the

school system and called for fundamental-system wide-reform from the bottom

up. These changes would, in turn, impact governance structures, teaching and

11

learning and school-community relations. Implementation of systemic reform

rested on the standards movement and enabled site-based decision-making. As

the standards movement took hold, states moved to set up state standards and

assessments. While these standards and assessments would become integral to

the implementation of the No Child Left Behind Act of 2001, and specifically to

holding schools accountable to making annual yearly progress, they also

succeeded in changing how schools were evaluated. As inputs-regulation by

districts and states-carried less weight than outcomes-usually measured by test

scores-new players were able to enter the education reform arena (Wells, 2002).

Systemic reform, market ideology, the growth of the small schools

movement, and the neoliberal desire to privatize government services created an

extremely amenable environment for the growth of private or cross-sector school

originators such as EMOs, CMOs and intermediary organizations. Arising in this

policy environment were for-profit EMOs, like Edison Schools and Mosaica, and

non-profit organizations, such as Knowledge Is Power Program (KIPP).

In parallel, the small schools movement moved from functioning on the

fringe to gaining widespread support as a way to address policymakers and the

public's growing dissatisfaction with failing comprehensive high schools (Powell,

Farrar & Cohen 1985; Sizer, 1984). As large sums of foundational and federal

moni es were directed t oward creating new small schools, private sector pl ayer s

reflecting the current neoliberal and neoconservative policy environment-were

invited to be part of the reform. Requiring a proving ground to demonstrate their

12

ability to produce more efficient and effective schools, private sector

organizations, such as intermediary organizations, seized on this means of

entering the public education sector.

Simultaneously, the current iteration of the small schools movement also

attracted progressive educators who desired to create new types of schooling

options within the public school system to address the needs of students not being

met by traditional public schools. Social justice themed schools, Afro-centric

schools, schools fostering women's leadership potential and schools focused on

the needs of English language learners were a few examples that emerged from

this political and economic climate.

Having examined the national policy context that gave rise to this new

approach to school reform, the next section focuses on how this context has

played out on a local level in New York City, as the city has moved to privatize

and marketize aspects of public schooling, with an increased emphasis on high

stakes testing and accountability.

Political and Economic Context: A Local Perspective

Michael Bloomberg, the CEO and founder of Bloomberg, LP, campaigned

on, among other policy positions, gaining mayoral control of the New York City

school system. After he took office as Mayor in January 2002, the New York

State legislature granted Bloomberg that control. Shortly after the school system

became a mayoral agency, Bloomberg hired Joel Klein, the former Chairman and

13

CEO of Bertelsmann, Inc. to be Chancellor of the New York City Public Schools.

In the winter of 2002, Chancellor Klein began a series of reforms. First, he

launched the Children First Reform Initiative, which called for the comprehensive

reform of the New York City Department of Education. This first restructuring

eliminated the city wide Board of Education and community school boards and the

32 independent community school districts were organized into 10 regions. These

regions became the focus of the new governance structure, with regional

superintendents reporting directly to the Chancellor (Fruchter, 2006). Five years

later, in the spring of 2007, Chancellor Klein announced a second restructuring

which further decentralized that school system and continued efforts to build an

educational marketplace with the participation of private sector partners.

Building an Educational Marketplace

Two main ideas drove the 2007 restructuring: school-based decision-

making and market competition. With this current reform, the Mayor and

Chancellor aim to empower principals by giving them more decision-making

power over their individual schools, including influence over curriculum

selection, human resources and the budget. At a Manhattan Town Hall Meeting,

Chancellor Klein commented, "decisions are best for kids when they're

happeni ng close to kids at the school level. Starting in 2007- 2008, rather than

being told what to do by distant bureaucrats, principals and school communities

will have decision-making power and they'll be responsible for results" (Town

14

Hall Meeting, February 6, 2007). In the previous system, the region selected

curricular and intervention materials and ran programs such as summer school;

this new system gives principals the authority to make these decisions, and to

choose a "support organization" that best serves the needs of their school. To this

end, the governance structure of 10 regions has been replaced by three distinct

sets of school support organizations. Two of these, the empowerment support

organization [ESO] and learning support organizations [LSO], remain internal to

the Department of Education, and had already existed to some extent within it.

However, the third, partnership support organizations [PSOs], represents a new

model for New York City and hails from the private sector (NYC DOE, 2007).

Differences exist surrounding the level of support offered by and the cost of the

three school support organizations.

Partnering with the Private Sector to Run "Not a Great School System,

but a System of Great Schools"

With these governance changes the NYC DOE aimed to create a

"Portfolio of New School Options" from which students and their families can

choose. As Chancellor Klein stated, the NYC DOE seeks to create "not a great

school system, but a system of great schools" (NYC DOE, 2008). Thus, the

importance of the small schools movement comes into play; increasing the

number of schools part nered with intermediary organizations and charter schools

is an essential component of creating a diverse, choice-enabling educational

marketplace. Since 2003, over 260 new small schools and over 60 charter schools

15

have been created with an additional 19 charter schools slated to open for the

2008-2009 school year (NYC DOE News, 2008). The creation of over 300

schools in partnership with private sector organizations exemplifies the

Department of Education's commitment to private sector involvement and market

ideology.

New Accountability Mechanisms

6

As a result of the 2007 reorganization, principals now have increased

authority over school-level decision making and budget processes. To hold

principals accountable, the Department of Education has produced new methods

to monitor and measure school effectiveness: progress reports and quality

reviews. With progress reports, each school receives a letter grade (A-F).

Standardized test scores, attendance reports and the results of surveys determine a

school's grade. In contrast to the outcome oriented progress reports, quality

reviews provide a more descriptive overview of the school (NYC DOE, 2007b).

For new small schools, which do not have graduations rates or local reputations to

attract new students, these new accountability measures carry significant weight

and, as the cases will illustrate, impact not only school-level personnel but also

the intermediaries with which they are partnered.

Concepts and information from this section were originally written for Scott and DiMartino

(2009a).

16

This combination of a political and economic environment which

championed privatization, mayoral control, high stakes accountability systems,

the proliferation of small schools, and large scale investments by foundations with

a focus on failing high schools across New York City created a fertile

environment for the emergence of public-private partnerships targeted to improve

public education. Having introduced this study and placed it within a larger

political, historical and economic context, the next section takes a closer look at

intermediary organizations themselves.

The Emergence of Intermediary Organizations

Similar in concept to the school design teams

7

of the New American

Schools (NAS), the school reform models of the Comprehensive School Reform

Design (CSRD), and the external partners of the Chicago Annenberg Challenge,

intermediary organizations' outsider status is meant to give them the ability to

"cross organizational boundaries in order to inspire vision, to focus change, to

lend support to change efforts, and to apply pressure to change" (McDonald,

McLaughlin, & Corcoran, 2000, p. 6). Terms such as school design teams,

external partner, reform support organization and school development

organization are often used to describe the intermediary construct. These

organizations may provide funding, technical assistance, professional

The design teams of the NAS were a precursor to the comprehensive school reform models of

the CSRD program. As a result, many of NAS design teams became models in the CSRD

program, including Accelerated Schools and Success for All.

17

development for teachers and administrators, curricular materials and programs,

and advocacy on behalf of schools. All of these functions are expected to build

the capacity of schools to nurture and sustain whole-school reform.

In their study of the external partners used in the Chicago Annenberg

Challenge, McDonald, McLaughlin and Corcoran (2000) found that:

'Regular' organizations such as schools, districts, states, and

universities, in this case, cannot reliably change themselves.

Being caught up in the dynamics of the status quo, they cannot

easily act as catalysts for redefining it, or for refocusing

policies and reform agendas that include their own (p. 6).

To this end, an outside entity, such as an intermediary organization, brings its own

understandings and expertise to the organization in need of reform and can act as

an outside lever for change. For example, proponents hope that an Expeditionary

Learning Outward Bound school will look different from its neighboring public

schools not only because of its small size, but also because of an infusion of ideas

from the intermediary. In this way, the presence of intermediary organizations

opens up the education system and brings new "human and intellectual resources"

into the world of educational reform (Smylie and Corcoran, 2006, p. 14). Unlike

some reforms which focus on teaching and learning practices or school

leadership, the use of intermediary organizations aims to change the governance

structure of schools, which in turn affects teaching and learning, and leadership.

Foundations such as the Annenberg Foundation, the Bill and Melinda

Gates Foundation, and the Ford Foundation have championed intermediary

organizations as vehicles for school reform. Their support reflects concerns about

18

policy implementation, as many "interventions are never implemented as

proposed so as to have the desired effects" (Bodilly, 1996, p. 10). This challenge

of implementation cultivates a general distrust of public education's ability to

reform itself. In the Journal of the Annenberg Challenge (2002), Rothman

explains:

Private funders were reluctant to contribute to the New York City

Schools [for example] because they were concerned that the funds

might not be used the way they were intended. But by enabling the

funders to contribute to a private organization, which provided a

means of tracking funds and evaluating their effectiveness, the

Center [an intermediary organization] provided a 'comfort level'

for donors (p. 5).

Foundations' unease with giving directly to schools or districts belies not only

their past difficulties implementing reforms (Bodilly, 1996), but also current

neoliberal and neoconservative ideology which believes that the private sector is

more efficient and effective than public organizations (Chubb and Moe, 1990).

Given the political, economic and historical background, the purpose of

this study is to examine public-private partnerships in practice. Through two case

studies of schools and their intermediary partners, the findings from this study

will reveal the complexities of this approach to school reform.

An Introduction to the Findings

Findings from this study will ultimately show that the actual

implementation of these partnerships proved to be much more complex than

theorized and had much more mixed outcomes than expected. While

19

relationships existed between intermediaries and school-based stakeholders,

calling these associations "partnerships

8

" may be misleading. Rather than equal

partners in the relationship, the intermediary organizations, who tended to possess

more money, more power and greater access to high status networks, assumed

managerial roles in the relationship. This assertion of authority created tension at

the school level as some principals, teachers and parents struggled to understand

the parameters of the school-intermediary relationship, and were frustrated by

how the addition of the "partner" restricted their ability to control the environment

in which they worked or sent their children to school.

This study will also uncover the importance of contextual factors, such as

policies that encourages partnerships to form quickly, the experience or lack

thereof of principals and intermediaries, pressures to perform on accountability

measures, and race and poverty. In addition, findings will reveal the sometimes

competing private and public goals that surface as a result of public-private

partnerships, and the nuanced and often complicated parameters of power and

control which stakeholders within these hybrid relationships must negotiate. The

following section provides an overview of the dissertation.

Though the term partnership is problematic, it is the term that policymakers and practitioners use

to describe the intermediary-school construct. It will be the term that this dissertation uses often to

refer to this approach to school reform.

20

Dissertation Overview

This dissertation unfolds over seven chapters. Chapter 1 introduced the

study, its purpose and rationale, its overarching research questions and its

underlying political, economic and historical context. Chapter 2 lays out the

conceptual framework which weaves together the theories of political scientists,

legal scholars and educational theorists to capture the complexities of inter-

organizational partnerships, raising questions about alignment of educational

values and goals for schooling, as well as the allocation of decision-making

power. To further operationalize this theorizing on power, Chapter 2 introduces a

spectrum of control which situates intermediary organizations within the larger

field of private sector partners and managers. Chapter 3 draws on the existing

literature on small schools, New American Schools, intermediary organizations,

reform support organizations, charter schools, EMOs and CMOs, to support and

challenge findings as well as reveal gaps in the research that this study fills.

Chapter 4 describes the data collection and analysis strategies used in this

dissertation. It defines each case as well as provides background information

about the intermediaries and the schools with which they were partnered.

Chapters 5 and 6 are case studies of public-private partnerships.

Chapter 5 introduces the case of Excelsior Academy: A University Edge

School (Excelsior)

9

which was co-founded in 2005 by the Department of

Education and University Edge, an intermediary organization. This case

9

Both Metropolitan United

9

and University Edge are pseudonyms.

21

chronicles the challenges and successes of a public-private partnership. Findings

from the case reveal points of deep mission and goal alignment as well as areas of

profound discord amongst key stakeholders. Additionally, it highlights the

importance of stakeholder buy-in, leadership capacity, and ownership and

proprietary rights.

Chapter 6 chronicles the Metropolitan United Entrepreneurship and

Citizenship Academy's (ECA) experiences with a public-private partnership. The

school began as a quickly formed partnership agreement between the principal of

ECA and Metropolitan United, and the case follows the partnership's rancorous

dissolution. This break-up story surfaces the importance of mission alignment,

leadership capacity and control in inter-sector partnerships.

The dissertation ends with Chapter 7, which provides both a cross-case

analysis comparing and contrasting the findings from Excelsior Academy and

ECA, and a conclusion. It begins with an overview of the study and then presents

the major findings. A discussion updating the spectrum of control follows which,

considering the fluid nature of intermediary organizations, situates them on the

spectrum as well as raises questions about their futures. Implications of this study

for research, policy and practice will be discussed in Chapter 7.

Conclusion

This study concludes that the use of intermediary organizations to reform

public education requires a healthy public debate in which the overall

22

effectiveness of this approach to school reform must be weighed. If, as many

indicators suggest, using public-private partnership to improve public education

remains a key approach to strengthening public schools, then policymakers and

practitioners must: 1) improve transparency to clearly outline the identities, roles

and responsibility of each actor in the relationship; 2) increase regulations to

ensure that schools do not use admissions processes to discriminate against

students and that schools accurately portray themselves in marketing materials to

be shared with students and parents; and 3) slow the pace of the reform to avoid

scaling up so quickly that a critical mass of experienced teachers, leaders and

intermediaries cannot keep pace. Additionally, policymakers and practitioners

must be mindful of students and families attending these hybrid schools and

appreciate that they are participants in this educational experiment. While some

degree of upheaval is to be expected when implementing a new reform, the three

or four years it takes for some schools to become fully functioning represents

most students' entire high school experience.

23

CHAPTER II

FRAMING HYBRID SCHOOLS: CONCEPTUALIZING THE

INTERSECTIONOF EDUCATIONAL VALUES AND POWER

Introduction

The emergence of intermediary organizations as a driving force in

reforming secondary school education requires a very specific climate; truly, the

stars must align. In New York City, the "stars" include the mayor, business

leaders, parents, teachers, school administrators, community groups, social-

agency staff and foundation officers, all of whom must be motivated to align

around a specific policy issue. Stone, Henig, Jones and Pierannunzi (2001) refer

to this phenomenon as "civic capacity" (p. 4). For this study, the specific policy

issue is the use of public-private partnerships to reform public education.

According to Stone et al, the activation of civic capacity calls for reforms that

change existing relationships to ensure the institutionalization of new reforms.

This means that the new institutional relationship created by public-private

partnerships must not only look, but act, differently, as a newly constructed type

of governing relationship between the stakeholders (p. 8). Building new

rel at i onshi ps requires sector boundari es to be crossed, values to be exchanged,

and, ultimately, power to be negotiated among partners.

24

To examine the politics of public-private partnerships, the conceptual

framework for this dissertation weaves together theories and research on public-

private partnerships from political scientists, legal scholars, and educational

historians. These scholars highlight the pivotal role that educational values and

goals for schooling play in individual organizations. Further, they discuss how

the act of partnering necessitates the negotiation of these values and goals;

ultimately, it is the more powerful actor whose agenda of educational values and

goals is most likely to get implemented. Thus, understanding the parameters of

power becomes essential for comprehending decision-making within private-

public partnerships. To illuminate levels of control within inter-sector

partnerships, this chapter presents a spectrum, which posits three distinct types of

private-public relationships along a continuum.

The Politics of Hybrid Schools: Crossing Sector Boundaries,

Exchanging Values and Negotiating Power

Paying close attention to an organization's values and goals for schooling

can reveal organizational missions that are not necessarily explicitly articulated.

Frederick Wirt and Michael Kirst's (2001) analysis of the complex set of values

involved in educational policymaking highlights the intricacies of public-private

partnerships. Investigating these intricacies, Martha Minow (2002) raises

important questions about the value differences inherent in organizations hailing

from the public and private sectors. David Labaree (1997) pushes the idea of

values even further by suggesting three distinct goals of schooling: democratic

25

equality, social efficiency, and social mobility; goals which affirm Minow's

discussion of democratic values, but also highlight the role of consumer choice.

Joel Handler (1996) both acknowledges the complexities surrounding the politics

of schooling and raises questions about who is empowered by these new

governance structures. Specifically, Handler encourages studying decision-

making processes at the school level to see which stakeholders' values for

schooling dominate within these cross-sectoral partnerships.

Wirt and Kirst (2001) highlight the critical role that individual and group

values play in the politics of public education. They argue that it is these values,

particularly the values of quality, efficiency, equity and choice, (p. 66) that drive

individual and group decisions about education. Stakeholders, including parents,

school administrators, teachers, intermediary organization staff, foundation

officers, public office holders, community groups and business leaders, have

formed their own sets of values regarding education based on the cultural and

historical context in which they operate. Wirt and Kirst explain: "education

policy touches on a mosaic of American values -religious, ethnic, professional,

social, economic- that often clash in politics" (p. 75). Conflicts often emerge

among these various constituencies over two fundamental questions: "What

should be taught in school? Who should do it?" (p. 12).

As Wi rt and Kirst further assert, "t ensi on arises among t hem because

different policy actors back different values" (p. 67). These stresses become

highlighted because educational resources are limited, allowing for the

26

advancement of only certain groups' policies and underlying values. The

championing of certain policies reveals who holds the policy-making power in the

United States; "whose values currently dominate the political system" (p. 58). In

terms of this study, examining who champions which values and,

correspondingly, whose values are implemented at the school level, will reveal

how power is negotiated within public-private partnerships.

When school governance involves multiple stakeholders, value conflicts

tend to emerge and negotiations must occur in order for these hybrid schools to

function. Stone et al (2001) highlight the importance of value alignment among

multiple stakeholders:

School reform, in important respects, can be seen as a window into

a larger and enduring set of questions relating to collective

problem solving. In particular, this case sheds some light on the

special dynamics that characterize what we have labeled "high

reverberation" subsystems: policy subsystems characterized by

frequent reshuffling of mobilized stakeholders, multiple and deeply

held competing value and belief systems, and ambiguous

boundaries, making the prospects for establishing a new

equilibrium more problematic than is usually the case (p. 152).

The concept of "deeply held competing value and belief systems and ambiguous

boundaries" resonates with this study, as the focus lies on the institutional

relationships that emerge as a result of public and private entities negotiating the

creation of new public schools. At the macro level, education policy is

complicated, yet t he introduction of the private sector, whose val ues and mi ssi ons

sometimes clash with those of the public sector, adds an additional layer of

mission-setting complexity at the micro and macro levels of school reform.

27

Minow (2002) deconstructs why conflict emerges when public and private

entities collaborate. Referencing the Constitution and a series of other legal

precedents, Minow (2002) explains that public sector entities have:

commitments to equality, freedom, fairness, and democracy.

Translated in our legal system as antidiscrimination, freedoms of

association and religious exercise, due process, and voting, these

public commitments traditionally helped to undergird the public-

private distinctions itself, ensuring private freedoms by restricting

public incursions (p. 31).

Minow posits that while private sector organizations may support similar

values, they are not held accountable for them to the extent that public sector

organizations are. By choosing to merge with a public sector organization,

therefore, the mission of the private sector organization is at risk of being

compromised. Minow suggests "conflicting mission and loss of accountability

surface immediately as central problems when public and private, profit and non-

profit, and secular and religious sectors converge" (p. 28). This vision of the

differences in public and private sectors implies that when sector boundaries blur,

stakeholders must examine how and when their values and missions do or do not

align, and work to negotiate a new vision for partnership.

Expanding on this discussion of organizational values and missions,

Labaree (1997) argues that throughout history the goals of schooling have been

debated and contested. Are students being prepared to be citizens, (democratic

equality), contributors to the larger economic marketplace (social efficiency), or

to gain the best jobs (social mobility) (Labaree, 1997, pp. 43-46)? Labaree

elaborates on these terms when he explains, "from the perspective of democratic

28

equality, schools should make republicans; from the perspective of social

efficiency, they should make workers; but from the perspective of social mobility,

they should make winners" (p. 66).

While these goals often overlap for people, one may trump the rest. For

example, some scholars, progressive educators and citizens view public schools as

a means of reproducing democratic society. In contrast, other stakeholders, such

as members of the Business Roundtable and Bill Gates, often emphasize goals of

social efficiency when they express concern that high schools do not prepare

workers for the knowledge-based economy. Finally, there are people who,

adhering to the Horatio Alger myth of individualism and hard work, prize the

personal prestige, status and financial attainment associated with credentials from

an elite education; social mobility trumps all else.

This discussion of values and goals provide a useful lens through which to

explore the relationships that evolve when public and private organizations

partner to co-found a new small school. However, knowledge of diverse and

sometimes conflicting values is not, by itself, a sufficient framework for studying

these complicated partnerships. Thus, integrating Handler's work, as this study

will do in the next section, pushes the study above and beyond values, to unravel

the complexities of empowerment embedded within the lived experiences of

peopl e worki ng in and at t endi ng these partnership-led schools.

29

The Politics of Power and Control

Many current policymakers argue that privatization shifts authority away

from the centralized government to an array of stakeholders. This raises

questions about the distribution of power among stakeholders, especially the

question of who is gaining or losing influence in these new institutional

relationships. For example, new small schools partner with intermediary

organizations to "break the 'government monopoly' over public education and

instead infuse public schools with market forces of choice and competition"

(Scott, 2002b). The hybrid governance structures created by partnerships,

proponents argue, empower site level personnel and community members, while

also creating more accountable, effective and equitable schools. Recognizing that

privatization involves "reallocation of power and resources between various

interest groups and stakeholders," (p. 5) Handler (1996) raises questions about

who is actually empowered by these new governance structures. Handler asks:

"What are the consequences of these moves for citizen empowerment? Will

ordinary citizens -clients, patients, teachers, students, parents, tenants, and

neighbors- have more or fewer opportunities to exercise control over decisions

that affect their lives?" (p. 5). Empowerment, "the ability to control one's

environment" (p. 115), is meant to give school level stakeholders greater

decision-making power over issues that directly impact their daily lived

experiences in schools.

30

The introduction of the private sector brings new players into the politics

of decision-making at the school level, players with significant clout. Given the

potential for an imbalance in power, Handler (1996) expresses concern about who

governs these private sector organizations and their relationships with the

communities that the hybrid schools serve. Located in low-income communities

of color, these new hybrid schools serve diverse students bodies. In contrast, non-

profit and for-profit organization boards of directors tend to be dominated by

"predominately white, male, Protestants, in their fifties and sixties, wealthy, in

business or law" (p. 100), who have been selected precisely because this

constituency tends to bring political and economic capital to an organization.

Noting the lack of women and minorities on boards leads Handler to question the

"democratic character" of the organizations (p. 100).

As powerful outsiders enter school reform, Handler (1996) stresses the

importance of all stakeholders having a voice in school decision making, but

expresses concern that those with access to greater financial and political

resources may be more empowered than the people living in the communities

served by or working in the school. In this situation, rather than empowering all

stakeholders, Handler argues that reforms that focus on privatization simply

replace "one hierarchical regime for another" (p. 220). To this end, studying

these hybrid partnerships requires not only looking closely at who participates in

decision-making processes, but also at who sets the agenda and has the greatest

access to financial and political resources.

31

To understand who holds power over decision-making it is essential to

capture how power-manifested through control-is shared among different types

of partnerships, and to question whether the organizational relationships formed

between intermediaries and small schools are, in fact, partnerships, or instead

another more complex form of management and associations. The following

section operationalizes power by placing various types of private sector partners

on a spectrum of control.

The Spectrum of Control

By taking organizational goals and local context into consideration, this

spectrum captures three types of private sector relationships and places them on a

spectrum of control - from affiliation, which represents the least control, to

comprehensive management, which represents the most. This spectrum is

important; where a private sector partner lands on the continuum reflects the

amount of control that it will be able to leverage within a school, and in turn, how

likely its educational values and goals for schooling are to take precedence, even

if they clash with those of school level stakeholders.

The spectrum contains three categories that private sector organizations

working with public schools can fall into and between: affiliation, thin

management and comprehensive management. By combining organizational

characteristics (such as whether or not an organization has a set design model)

with contextual characteristics (such as whether or not teachers are unionized)

32

these categories represent varying levels of influence that an organization might

be expected to hold over a school.

Affiliation organizations hold the least amount of control, and often are

not actively seeking greater power; they are partners in the basic sense of the

word. Affiliations manifest their partnerships in ongoing ways such as school

mentoring, or in specific functions such as fundraising, but seldom bring a strong

philosophical educational agenda to the relationship. In contrast, thin managers

possess a greater degree of control, and often carry a clear design model that they

would like to see implemented by the partner school. However, thin managers

face the challenge of having to use soft "influencing" skills as best they can to

advocate for their ideas to be adopted, given that they do not hold ultimate

authority over key questions such as personnel and budget. Examples of thin

managers include many intermediary organizations as well as the design teams of

New American Schools. Finally, comprehensive managers directly and

effectively manage the schools they are partnered with, and therefore have the

most influence over all aspects of decision-making. Of the three levels of control,

organizations that fall along the comprehensive management part of the spectrum

have the greatest latitude in implementing their vision for school reform. Of

course, depending on organizational goals and local context, a given private

sector organi zat i on can also move up and down the spectrum, falling into and i n

between the various categories. Refer to figure 2 to see the full spectrum of

control.

33

Manager

a

T

R

O

Partner

Affilia tion

"Aiif.ts' '

' j . ,'1 ''iiw,n model

Di st ri ct cont rol s budgeti ng

and personnel decisions

No contracts

Teachersare unionized

Partnerswith local networks

of schools

May be for or non-for-profit

E*: Partners, Intermediaries

Tl' in tf i r a gmcnt.

^ "Inftiicpces'

1

tf

i * J i *

and per sonnel deci si ons

f or mat or i nf or mal cont ract

>.vith school or di stri ct

TeacnersusuaOy unionized

Affiliates with national and

local networks of schools

May be for or non-for-profit

Ex: New AmericanSchools

DesignTeams. EMOs. CMOs.

Intermediaries

Comprehensive

_^. Ma ni gvmcnt .

m - Cont r ol ^

-* i . * k i i i ' * !

. . . -i * .i i. .

' . - ' n ; * : , * nf l ^i

-1 1 l | V I I

1

1 1

i

uni oni zed

Manages national net works

school s

May be f or or non-f or-prof i t

Ex: EMOs. CMOs

Figure 2. Spectrum of Control

10

To construct the spectrum of control, findings from this study were

integrated with theoretical and research based articles produced by educational

researchers (Gold, Christman & Herold, 2007; Scott and DiMartino, 2008b) and

think tanks (Colby, Smith and Shelton, 2005). Findings from this study revealed

that the work of intermediaries varies over time and circumstance, a situation

which is exacerbated by their finite funding streams. This means an intermediary

may start out as an affiliate of a school, but over time transfer into the role of thin

management as political or economic circumstances change. Thus, the fluid

nature of intermediaries lends itself to the use of a spectrum. In fact, the findings

Ideas from Colby, Smith and Shelton's (2005) spectrum of loose to tight management

responsibility, support and control influenced the creation of this spectrum of control.

34

from this cases analyzed in this document showed intermediary organizations,

over time, acting less and less like affiliates and more and more like

comprehensive managers, putting into question the "partnership" aspect of this

approach to school reform.

The works of Scott and DiMartino (2009b) and Colby, Smith and Shelton

(2005) map out the institutional landscape of private sector management in public

education. Scott and DiMartino's (2009b) research focuses on capturing the

breadth of private sector managers and on defining new players in the field of

education management, such as CMOs and intermediary organizations. Colby,

Smith and Shelton (2005), for their part, focus on differentiating managerial

responsibility, support and control among private sector organizations working

with public schools. By creating their own spectrum of loose to tight

management responsibility, support and control, Colby, Smith and Shelton show

how "organizational capabilities and culture, and the scale and complexity of their

operations" impact whether school-organizational relationships look like

"voluntary associations" or "true ownership" (p. 5). The authors' use of a loose to

tight spectrum offers a helpful means to conceptualize the school-partner

relationship, but suffers from not being rooted in local political and economic

contexts; absent from their work, for example, is a conversation about the role of

district contracts or memor andum of underst andi ngs (MOUs), and t he i mpact of

teachers' unions. To this end, Gold, Christman and Herold's (2007) research in

35

Philadelphia on the implementation of a diverse provider model becomes

particularly useful.

Gold, Christman and Herold (2007) introduce the term "thin management"

to describe the implementation of the diverse provider model

11

in Philadelphia.

Under "thin management," private sector providers, such as Edison Schools and

Temple University, were given limited authority over the schools that they

managed and were working to improve. Gold, Christman and Herold explain:

"under thin management, schools were not turned over lock, stock and barrel to

providers. Instead, the district retained responsibility over such key areas as

staffing, school grade configurations, facilities management, school safety, food

services, the overall school calendar, and the code of conduct for teachers and

students" (p. 198). In Philadelphia, thin management resulted in providers having

limited control over their schools, which challenged their ability to implement

their educational goals for schooling.

The spectrum of control is crucial to this study; where an intermediary

organization falls along the spectrum indicates how much power they possess,

and, in turn, how much their educational values and goals for schooling will

dominate school decision-making processes. It also reveals that intermediary

organizations with definite views on improving public education have an

i ncent i ve to move from bei ng partners to managers on the spectrum. Recall that

A diverse provider model of school governance refers to the outsourcing of school management

to private sector groups, including for-profit companies, non-for-profit organizations and

universities to improve historically low-performing public schools (Gold, Christman & Herold,

2007; Hill, Pierce & Guthrie, 1997).

36

the theory behind using intermediary organizations as change agents calls for

them to be able to scale up and replicate their work, following a specific model or

core principles; the intermediary needs willing school partners to act as its

laboratory for testing and validating these reforms. Lack of control can stymie

those reforms. Further, the spectrum reveals that even if an organization's

characteristics remain static, local factors, such as whether or not schools are

unionized, have the potential to expand or limit its power, thus making large-scale

implementation of a set school design more challenging. This scalability question

is another central challenge in a public-private partnership, which will be further

explored later in the study.

Conclusion

The role of personal and group values in the politics of education, the

challenges implicit in cross-sectoral collaboration, the multiple goals of

schooling, and the importance of studying school-decision making processes all

help to uncover the distribution of power among stakeholders within public-

private partnerships. The integration of these diverse yet overlapping

perspectives provides a lens through which to examine the educational values and

goals for schooling that motivate stakeholders to enter partnerships, the

organizational and local characteristics that foster varying degrees of control, and,

ultimately, the negotiation of power among key stakeholders in the partnership.

37

CHAPTER III

REVIEW OF LITERATURE

Introduction

Multiple strands of literature were surveyed to find out what is known and

what remains to be explored about the relationship between public schools and

private sector actors, since no comprehensive literature exists that delineates the

intermediary- school association. Rather than examining organizations that might

provide one or two services to schools, this review focuses on those entities that

provide a comprehensive array of services, for example a school design model

that includes both curriculum and teacher professional development. This review

of literature relies on findings from studies on New American Schools, the

Comprehensive School Reform Demonstration program (CSRD), charters

schools, EMOs, CMOs and reform support organizations. Findings from the

literature are organized around three broad themes: 1) the motivations and

contextual factors that affect cross-sectoral collaboration; 2) the distribution of

power and its impact on governance within joint ventures; and 3) the ways in

which success is measured, sustained and replicated within inter-organizational

38

relationships. Findings from this review of literature clarify some aspects of the

intermediary-school community relationship, but also highlight gaps in the

research that this and future studies will address.

Motivations and Contextual Factors that Impact Cross-Sectoral Partnerships

This section examines the diverse motivations for cross-organizational

collaboration, from clearly designed state and local policies to more nuanced

financial, political and organizational incentives. It continues with a review of

different contextual factors that potentially impact the partner-school relationship,

such as the non-profit or for-profit status of the partner and the geographic

proximity of the partner to its schools. Findings from the literature on these

topics illustrate the important role that motivation and context play in building

effective and successful collaborations. Findings also raise important questions

about inequitable access to financial resources and political networks, lack of

transparency, and the potential for organizational isomorphism as foundational

funding ends.

Legal, Financial, Political and Organizational Incentives

In the political context of the privatization-led reform movement described

in Chapt er 1, government legislation and foundational requirements often

explicitly require private sector collaboration. For example, within charter school

reform, some state charter school laws require the inclusion of some type of

39

private sector partnership or alliance in order for a charter to be granted

(Wohlstetter, Malloy, Smith & Hentschke, 2004, p. 336; Miron & Nelson, 2002).

Specific to the current iteration of the small schools movement, a few cities, such

as New York City, strongly suggest that individuals who want to start a new

school form a partnership with a private sector organization, whether an

intermediary, EMO or CMO. In fact, not choosing a partner could put a founder-

principal's school design in peril of not being accepted by the City. It is not

surprising, then, that the majority of New York City's new small schools that

opened in 2008 were founded in collaboration with a partner organization (NYC

DOE School Choice, 2008). Foundations, for their part, have often made funding

contingent on having private sector partners. For example, cities that want to be

recipients of small school start-up grants from the Bill and Melinda Gates'

Foundation's National School District and Network Grants must incorporate

intermediary or partner organizations into their small schools initiative, as this

program gives funds to intermediary organizations rather than directly to public

school districts (Huebner, 2005; AIR, 2003). As such, there are clearly strong

incentives from both public and private sources that encourage collaboration

between public schools and private partners. Having reviewed these legal and

structural incentives, the study will now examine financial, political and