Professional Documents

Culture Documents

JAnaesthClinPharmacol293394-8554992 234549 PDF

JAnaesthClinPharmacol293394-8554992 234549 PDF

Uploaded by

Ale Zuve0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

46 views3 pagesThe document discusses the challenges faced when providing anesthesia to opioid addicts. It presents the case of a 35-year-old opioid addict (pentazocine) who required surgery to treat non-healing ulcers on his forearms from intravenous drug use. He was initially managed medically for his addiction and withdrawal symptoms. For his surgery, he received a planned non-opioid anesthesia including ketamine, sevoflurane, and diclofenac while continuing his oral naltrexone treatment. The perioperative period for opioid addicts presents challenges such as increased analgesic needs, potential for drug-seeking behavior, and medical complications from addiction. Anesthesiologists must carefully consider the patient's addiction history and treatment to safely

Original Description:

Original Title

JAnaesthClinPharmacol293394-8554992_234549.pdf

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentThe document discusses the challenges faced when providing anesthesia to opioid addicts. It presents the case of a 35-year-old opioid addict (pentazocine) who required surgery to treat non-healing ulcers on his forearms from intravenous drug use. He was initially managed medically for his addiction and withdrawal symptoms. For his surgery, he received a planned non-opioid anesthesia including ketamine, sevoflurane, and diclofenac while continuing his oral naltrexone treatment. The perioperative period for opioid addicts presents challenges such as increased analgesic needs, potential for drug-seeking behavior, and medical complications from addiction. Anesthesiologists must carefully consider the patient's addiction history and treatment to safely

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Download as pdf or txt

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

46 views3 pagesJAnaesthClinPharmacol293394-8554992 234549 PDF

JAnaesthClinPharmacol293394-8554992 234549 PDF

Uploaded by

Ale ZuveThe document discusses the challenges faced when providing anesthesia to opioid addicts. It presents the case of a 35-year-old opioid addict (pentazocine) who required surgery to treat non-healing ulcers on his forearms from intravenous drug use. He was initially managed medically for his addiction and withdrawal symptoms. For his surgery, he received a planned non-opioid anesthesia including ketamine, sevoflurane, and diclofenac while continuing his oral naltrexone treatment. The perioperative period for opioid addicts presents challenges such as increased analgesic needs, potential for drug-seeking behavior, and medical complications from addiction. Anesthesiologists must carefully consider the patient's addiction history and treatment to safely

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Download as pdf or txt

You are on page 1of 3

394 Journal of Anaesthesiology Clinical Pharmacology | July-September 2013 | Vol 29 | Issue 3

Anesthesia for opioid addict: Challenges for perioperative

physician

Rohit Goyal, Gurjeet Khurana, Parul Jindal, J P Sharma

Department of Anaesthesiology, Himalayan Institute of Medical Sciences, Dehradun, Uttarakhand, India

Address for correspondence: Dr. Rohit Goyal,

Department of Anaesthesiology, Himalyan Institute of

Medical Sciences, Jolly Grants, Swam Ram Nagar PO Doiwala,

Dehradun, Uttarakhand, India.

E-mail: anaesdocrohit@rediffmail.com

Access this article online

Quick Response Code:

Website:

www.joacp.org

DOI:

10.4103/0970-9185.117113

Introduction

Globally there is a rising trend in opioid addiction. United Nation

on Drug and Crime (UNODC) estimates that there were

between 12 and 21 million opiate users worldwide in 2009.

Heroin remains the most commonly used opiate, consumed

by a vast majority of global opiate users (about 75%). Such a

patient can present to an anesthesiologist in a variety of situations.

The patient can be on varied drug therapy ranging from

methadone (for opioid deaddiction) to naltrexone (for maintenance

of abstinence). In this case study, we report an opioid (pentazocine)

addict on naltrexone (opioid antagonist) for abstinence presented

for nonhealing ulcers on both forearms secondary to his habit.

Institutional ethical committee clearance and consent from the

patient was obtained before reporting the case.

Case Report

A 35-year-old pharmacist with opioid dependence presented

to hospital with history of taking injection pentazocine 30 mg

via parenteral route since past 7 years. Frequency of usage

increased from 1-2 to 4-6 injections over a period of 7 years.

Route of administration varied from intravenous (IV),

intramuscular (IM), and subcutaneous (SC) whichever was

feasible. Each time he used his forearm for opoid shots. The

patient presented 1 month back with history suggestive of

opioid withdrawal. He complained of weakness and pain

in whole body. On further examinations multiple abscess,

crusts, scars, eschars, and ulcers were found on both forearms

[Figure 1].

Patient was conservatively managed with tab clonidine 100 g,

tab tramadol 50 mg, and tab loperamide 5 mg to cover up the

withdrawal phase. After symptomatic relief (about 2 weeks),

patient was put on tab naltrexone 25 mg once daily as a part of

abstinence maintenance therapy. Blood investigations revealed

hemoglobin of 6.7 gm%, hence two units of packed red blood

cells were transfused.

After a period of 1 month, patient was accepted for surgery

under American Society of Anesthesiologist Grade II.

A nonopioid anesthesia was planned. All the drugs

including naltrexone were continued till the day of surgery.

Strict orders were given to avoid all opioid analgesics till

day of surgery.

An IV access was achieved in left lower limb after multiple

attempts. Premedication consisted of Inj. midazolam

2 mg IV, Inj. glycopyrrolate 0.2 mg IV, and Inj. paracetamol

1 g IV. Anesthesia was induced with Inj. ketamine

100 mg IV, Inj. vecuronium 6 mg IV, sevoflurane at 4 vol%,

Opioid addiction is on a rise globally. Such a patient presents to an anesthesiologist as well as to the surgeon with an array of

challenges. We present the case of an opioid addict (pentazocine) who presented for debridement and grafting of eschars and

old healed scars. Initially he was medically managed for opioid addiction followed by a planned anesthesia. We hereby discuss

the challenges faced during perioperative period.

Key words: Challenges, naltrexone, opoid addiction, perioperative analgesia

Case Report

Abstract

[Downloadedfreefromhttp://www.joacp.orgonSunday,October19,2014,IP:189.219.134.161]||ClickheretodownloadfreeAndroidapplicationforthisjournal

Goyal, et al.: Anesthesia for opoid addict

Journal of Anaesthesiology Clinical Pharmacology | July-September 2013 | Vol 29 | Issue 3 395

and O

2

100%. Bag mask ventilation was done for 3 min

followed by oral endotracheal intubation. Low flow anesthesia

was started and anesthesia maintained with sevoflurane

2 vol%, O

2

(500 ml/min), N

2

0 (500 ml/min), and Inj.

vecuronium 1 mg IV as supplemental dose. Analgesia was

supplemented via Inj. diclofenac 75mg IV infusion. Noninvasive

monitoring with electrocardiography (ECG), noninvasive

blood pressure (NIBP), end tidal carbon dioxide (EtCO

2

),

pulse oximetry (SpO

2

), and temperature was done and

baseline parameters were noted. The intraoperative vitals were

stable throughout the surgery. Intraoperative fluid management

was done with ringer lactate 750 ml. Surgery was uneventful

and at the end of surgery, neuromuscular blockade was

reversed with Inj. neostimine 2.5 mg IV and Inj. glycopyrrolate

0.4 mg IV. The patient had smooth recovery, extubated, and

was shifted to postanesthesia care unit for further management.

Surgery lasted for 90 min.

In the postoperative care unit, patient demanded analgesia

after 1 h of surgery. Patient heart rate and blood pressure had

increased by almost 30% suggestive of pain. He was given

first rescue analgesic in the form of Inj. diclofenac 75 mg IV.

Suppemental dose of analgesic (Inj. paracetamol 1 g IV) was

repeated after 1 h. Patient was given Inj. diclofenac 75 mg

IV and Inj. acetaminophen 1 g IV alternatively after every

3 h for 24 h. This was followed by Inj. diclofenac 75 mg IV

after every 6 h for further 48 h. Tab naltrexone 25 mg was

continued as given in the preoperative period.

Discussion

Opioid addict present to an anesthesiologist with a wide array of

challenges. Anesthesia for emergency surgery can be encountered

in trauma patients and those requiring urgent invasive procedures.

Patients posted for elective surgery can be opioid addicts, on

various withdrawal regimens like methadone or on pure antagonist

for abstinence. Apart from this increased perioperative analgesic

requirement, a difficult IV access poses a constant challenge. Also

some of these patients are exposed to repeated surgeries, which

again make task of perioperative physician ardous.

Opioid addicts may give false history or malinger during

preanesthetic check up. If posted for elective surgery a proper

psychiatric work up should be done. Judicious titration of drugs

may be required perioperatively as these groups of patients are

nutritionally depleted with hypoproteinemia. Patients may

present with Munchausens syndrome (swallowing air to

mimic intestinal obstruction), ensuring precautions to be taken

as for full stomach patients. During perioperative period,

patient can present with marked hypotension due to poor

nutritional status and hypovolemia. Universal precautions

should be taken as patients are at risk of hepatitis and human

immunodeficiency virus (HIV). Further management depends

on type of anesthesia planned for opioid addicted patients,

which can be either opioid or nonopioid based.

If a nonopioid anesthesia is planned, as was done in this

case, naltrexone can be safely continued till day of surgery

and thereafter. Naltrexone HCl is related to the potent

opioid antagonist naloxone or nallylnoroxymorphone.

It is suitable for oral administration in scored tablets

containing 50 mg of naltrexone HCl. It binds to opioid

receptors in the central nervous system and competitively

inhibits the actions of opioid drugs (both pure agonists

and agonist/antagonists) and endogenous opioids. It is

indicated as opioid antagonist, maintenance of abstinence

from opioid addiction, alcoholism,

[1]

and in rapid opioid

detoxification under anesthesia.

[2]

Paracetamol, nonsteroidal

antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDS), ketamine, conscious

sedation with benzodizapenes, volatile anesthetics form

the mainstay of nonopioid anesthetic regimen. Various

regional techniques devoid of opioids can be used.

If an opioid based anesthesia is planned, naltrexone should

also be discontinued at least 24-72 h before surgery.

[3]

The

amount of opioid analgesic required may be greater than

usual and resulting respiratory depression may be deeper

and more prolonged. So a rapidly acting opoid analgesic like

sufentanil, remifentanil (infusion), alfentanil, and fentanyl,

which minimizes the duration of respiratory depression, is

preferred. The patient should then be abstinent from the

opioid for 3-5 days before resuming naltrexone treatment,

depending on the duration of the opiate use and the half-life

of the opiate. Patient can be started on analgesic regimens,

which may include NSAIDS (diclofenac), paracetamol,

local anesthetics via patient controlled-analgesia (PCA)

or patch to cover up this opioid free phase postoperatively.

COX 2 inhibitors like rofecoxib, celecoxib, and etoricoxib

can be considered for patients at risk for bleeding renal

impairment and gastric irritability. Neural blocks and wound

infiltration can also be used where appropriate. A more

conservative approach is to wait for 7 days till naltrexone

is started. As an alternative, a naloxone challenge test can

be administered.

[4]

The anesthesiologist should develop a clear management

strategy that maintains a balance to gain patients trust

with an understanding and empathic approach while being

prepared to overcome high-grade tolerance with liberal doses

of opioid and nonopioid analgesics.

[5,6]

Opioid doses required

to meet intraoperative and postsurgical analgesic requirements

are affected by receptor down-regulation and may need to

be increased 30-100% in comparison with requirements

[Downloadedfreefromhttp://www.joacp.orgonSunday,October19,2014,IP:189.219.134.161]||ClickheretodownloadfreeAndroidapplicationforthisjournal

Goyal, et al.: Anesthesia for opoid addict

396 Journal of Anaesthesiology Clinical Pharmacology | July-September 2013 | Vol 29 | Issue 3

in opioid-naive patients

[6,7]

Perioperative management

of opioid-dependent patients begins with preoperative

administration of their daily maintenance or baseline opioid

dose before induction of general, spinal, or regional anesthesia.

Patients should be instructed to take their usual dose of oral

opioid on the morning of surgery.

[8]

If a patient is on any withdrawal regimen like methadone

maintenance program, it should be continued till the day of

surgery. The mixed agonistantagonist-type opoid such as

nalbuphine, butorphanol, and pentazocine should be avoided

as they may precipitate acute opioid withdrawal in these

individuals.

[9,10]

Conclusion

The anesthesiologist plays the key role in maintaining baseline

opioid requirements, administering supplemental intraoperative

and postoperative opioid, and providing nonopioid analgesics

and neural blockade when required.

References

1. Crabtree B. Review of naltrexone, a long-acting opiate antagonist.

Clin Pharm 1984;3:273-80.

2. Gold CG, Cullen DJ, Gonzales S. Rapid opioid detoxification during

general anesthesia. Anesthesiology 1999;91:1639-47.

3. Gonzales JP, Brogden RN. Naltrexone. A review of its

pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic properties and

therapeutic efficacy in the treatment of opioid dependence. Drugs

1988;35:192-213.

4. Rosen MI, McMohon TJ, Margolin A, Gill TS, Woods SW, Pearsall

HR et al. Reliability of sequential naloxone challenge tests.Am J

Drug Alcohol Abuse 1995;21:453-67.

5. Collett BJ. Chronic opioid therapy for non-cancer pain. Br J Anaesth

2001;87:133-43.

6. Streitzer J. Pain management in the opioid-dependent patient.

Curr Psychiatry Rep 2001;3:489-96.

7. Saberski L, Sinarta SS. Postoperative pain management

for the patient with chronic pain. USA: Mosby Yearbook;

1992. p. 422-31.

8. Rapp SE, Ready LB, Nessly ML. Acute pain management in patients

with prior opioid consumption: A case-controlled retrospective

review. Pain 1995;61:195-201.

9. Gustin HB, Akil H. Opioid analgesics. In: Hardman JG, editor.

Goodman and Gilmans The Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics.

10

th

ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2001. p. 569-619.

10. Reisine T, Pasternak G. Opioid analgesics and antagonists. In:

Hardman JG, editor. Goodman and Gilmans The Pharmacological

Basis of Therapeutics, 9

th

ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 1996.

p. 521-55.

Figure 1: Same patient with old healed scars secondary to parenteral drug abuse

How to cite this article: Goyal R, Khurana G, Jindal P, Sharma JP. Anesthesia

for opioid addict: Challenges for perioperative physician. J Anaesthesiol Clin

Pharmacol 2013;29:394-6.

Source of Support: Nil, Confict of Interest: None declared.

[Downloadedfreefromhttp://www.joacp.orgonSunday,October19,2014,IP:189.219.134.161]||ClickheretodownloadfreeAndroidapplicationforthisjournal

You might also like

- Post Operative Effects Comparison of Total Intravenous and Inhalational Anesthesia 2155 6148.1000287Document7 pagesPost Operative Effects Comparison of Total Intravenous and Inhalational Anesthesia 2155 6148.1000287Taufik Sofist PresbomonetNo ratings yet

- Orig 1 S 000 Cross RDocument29 pagesOrig 1 S 000 Cross RDon RedbrookNo ratings yet

- 2264-Article Text-5024-4-10-20151024Document6 pages2264-Article Text-5024-4-10-20151024shivamNo ratings yet

- Haloperidol Combined With DexamethasoneDocument6 pagesHaloperidol Combined With Dexamethasoneapi-741687858No ratings yet

- Cesarean Section in Post-Polio PatientDocument2 pagesCesarean Section in Post-Polio PatientasclepiuspdfsNo ratings yet

- Sultana OFADocument7 pagesSultana OFANurshadrinaHendrakaraminaNo ratings yet

- Postoperative Nausea and Vomiting in OpioidFree Anesthesia Versus Opioid Based Anesthesia in Laparoscopic CholecystectomyDocument8 pagesPostoperative Nausea and Vomiting in OpioidFree Anesthesia Versus Opioid Based Anesthesia in Laparoscopic Cholecystectomypepe4dwinNo ratings yet

- KJAEDocument7 pagesKJAEM Wahyu UtomoNo ratings yet

- Research ArticleDocument7 pagesResearch Articlenaljnaby9No ratings yet

- Jurnal AnastesiaDocument8 pagesJurnal AnastesiaFikri SatriaNo ratings yet

- Comparison of Two Drug Combinations in Total Intravenous Anesthesia: Propofol - Ketamine and Propofol-FentanylDocument12 pagesComparison of Two Drug Combinations in Total Intravenous Anesthesia: Propofol - Ketamine and Propofol-FentanylArya ArgamandaNo ratings yet

- Opioid-Free Anaesthesia - Atow-461-00 - BDocument6 pagesOpioid-Free Anaesthesia - Atow-461-00 - BEugenio Martinez HurtadoNo ratings yet

- Cardiac Arrest Upon Induction of General AnesthesiaDocument7 pagesCardiac Arrest Upon Induction of General AnesthesiaIlona HiariejNo ratings yet

- MAC DexmethomidineDocument5 pagesMAC DexmethomidinedhitabwNo ratings yet

- Effect of Intraoperative Dexmedetomidine On Post-Craniotomy PainDocument9 pagesEffect of Intraoperative Dexmedetomidine On Post-Craniotomy PainIva SantikaNo ratings yet

- Jurnal 2Document5 pagesJurnal 2Isle MotolandNo ratings yet

- 10.1007@s00405 020 05801 6Document6 pages10.1007@s00405 020 05801 6Leonardo GuimelNo ratings yet

- Anaesthesia Clerkship HandbookDocument12 pagesAnaesthesia Clerkship HandbookKay BristolNo ratings yet

- Postoperative Nausea and VomitingDocument45 pagesPostoperative Nausea and Vomitingprem kotiNo ratings yet

- General AnasthesiaDocument7 pagesGeneral AnasthesiaUdunk Adhink0% (1)

- Anafilaxia MidazolamDocument3 pagesAnafilaxia MidazolamDiana PintorNo ratings yet

- Oral Premedication With Pregabalin or Clonidine For Haemodynamic Stability During Laryngoscopy and IntubationDocument14 pagesOral Premedication With Pregabalin or Clonidine For Haemodynamic Stability During Laryngoscopy and IntubationsreenuNo ratings yet

- Emergence and Postoperative Anesthetic Management: Prepared By: Serkalem Teshome Advised by Instructor WosneyelehDocument85 pagesEmergence and Postoperative Anesthetic Management: Prepared By: Serkalem Teshome Advised by Instructor WosneyelehagatakassaNo ratings yet

- Ketorolac Usage in Tonsillectomy and Uvulopalatopharyngoplasty Patients 2019Document4 pagesKetorolac Usage in Tonsillectomy and Uvulopalatopharyngoplasty Patients 2019Azzam SaqrNo ratings yet

- Journal ClubDocument39 pagesJournal ClubHassam ZulfiqarNo ratings yet

- 8a. General AnaesthesiaDocument28 pages8a. General Anaesthesiamatchees-gone rogueNo ratings yet

- Anes 10 3 9Document7 pagesAnes 10 3 9ema moralesNo ratings yet

- Dolor Postop, Ligamentos Cruzados, AmbulatorioDocument7 pagesDolor Postop, Ligamentos Cruzados, AmbulatorioChurrunchaNo ratings yet

- Early Postoperative ComplicationsDocument6 pagesEarly Postoperative Complications49hr84j7spNo ratings yet

- Two Toxicologic Emergencies: Case Studies inDocument4 pagesTwo Toxicologic Emergencies: Case Studies insiddharsclubNo ratings yet

- Effects of Propofol Anesthesia Versus SevofluraneDocument33 pagesEffects of Propofol Anesthesia Versus SevofluraneJuwita PratiwiNo ratings yet

- Relationship Between The Incidence and Risk Factors of Postoperative Nausea and Vomiting in Patients With Intravenous Patient-Controlled AnalgesiaDocument6 pagesRelationship Between The Incidence and Risk Factors of Postoperative Nausea and Vomiting in Patients With Intravenous Patient-Controlled AnalgesiaRandi KhampaiNo ratings yet

- Ropvacaina VS Lidocaina Premdicacion IotDocument6 pagesRopvacaina VS Lidocaina Premdicacion IotFaith Lu PenalozaNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S1053077020313677 MainDocument8 pages1 s2.0 S1053077020313677 Mainachavisva0196No ratings yet

- Anasthesia in Obese PatientDocument4 pagesAnasthesia in Obese PatientWaNda GrNo ratings yet

- International Journal of Anesthetics and Anesthesiology Ijaa 7 112Document4 pagesInternational Journal of Anesthetics and Anesthesiology Ijaa 7 112mikoNo ratings yet

- Medical Journal of Australia - 2020 - Hopkins - Educating Junior Doctors and Pharmacists To Reduce Discharge Prescribing ofDocument7 pagesMedical Journal of Australia - 2020 - Hopkins - Educating Junior Doctors and Pharmacists To Reduce Discharge Prescribing ofQurat ul ainNo ratings yet

- Extrapyramidal Side Effects After Metoclopramide Administration in A Post-Anesthesia Care UnitDocument3 pagesExtrapyramidal Side Effects After Metoclopramide Administration in A Post-Anesthesia Care Unitkhilwa alfaynaNo ratings yet

- Practice Guidelines For The Prevention, Detection, and Management of Respiratory Depression Associated With Neuraxial Opioid Administration AnDocument12 pagesPractice Guidelines For The Prevention, Detection, and Management of Respiratory Depression Associated With Neuraxial Opioid Administration AnMadalina TalpauNo ratings yet

- Acute Pain Management in Patients With Opioid ToleranceDocument6 pagesAcute Pain Management in Patients With Opioid ToleranceHendrikus Surya Adhi PutraNo ratings yet

- Use of Naloxone For The Management of Opioid OverdoseDocument4 pagesUse of Naloxone For The Management of Opioid OverdoseIOSR Journal of PharmacyNo ratings yet

- Original PapersDocument9 pagesOriginal PapersMárcia SanchesNo ratings yet

- Ponv InternasionalDocument8 pagesPonv InternasionalRandi KhampaiNo ratings yet

- BST - General ConsiderationsDocument9 pagesBST - General ConsiderationsDita Mutiara IrawanNo ratings yet

- Amantadine Alleviates Postoperative Cognitive Dysfunction Possibly by Increasing Glial Cell Line-Derived Neurotrophic Factor in RatsDocument13 pagesAmantadine Alleviates Postoperative Cognitive Dysfunction Possibly by Increasing Glial Cell Line-Derived Neurotrophic Factor in RatsSocorro Jiménez OlivaresNo ratings yet

- JAnaesthClinPharmacol37163-254754 000414Document4 pagesJAnaesthClinPharmacol37163-254754 000414Ferdy RahadiyanNo ratings yet

- JurnalDocument6 pagesJurnalFitri Aesthetic centerNo ratings yet

- Anesthesia RecoveryDocument18 pagesAnesthesia RecoveryBlueyNo ratings yet

- Continuous Peripheral Nerve Block For PoDocument5 pagesContinuous Peripheral Nerve Block For PoBinNo ratings yet

- Etm 17 6 4723 PDFDocument7 pagesEtm 17 6 4723 PDFLuthfi PrimadaniNo ratings yet

- r6 Perioperatif NoraDocument26 pagesr6 Perioperatif NoraHeru Fajar SyaputraNo ratings yet

- Section: Surgery: Category: B - Clinical SciencesDocument6 pagesSection: Surgery: Category: B - Clinical SciencesAbu TauhidNo ratings yet

- Preoperative Nursing: AntibioticsDocument10 pagesPreoperative Nursing: AntibioticsAnusha Verghese100% (1)

- Perioperatif NORADocument26 pagesPerioperatif NORAHeru Fajar SyaputraNo ratings yet

- Journal of Clinical AnesthesiaDocument2 pagesJournal of Clinical AnesthesiatsalasaNo ratings yet

- Overview of Complications Occurring in The Post-Anesthesia Care UnitDocument14 pagesOverview of Complications Occurring in The Post-Anesthesia Care UnitShahabuddin ShaikhNo ratings yet

- Journal Course Evidence Based Use of Nonopioid Analgesics August 2018Document7 pagesJournal Course Evidence Based Use of Nonopioid Analgesics August 2018DesywinNo ratings yet

- Anesthesia Books 2019 Bonica's-5001-6053Document1,053 pagesAnesthesia Books 2019 Bonica's-5001-6053rosangelaNo ratings yet

- Anesthesia For Day Care SurgeryDocument60 pagesAnesthesia For Day Care Surgerymedico_bhalla93% (15)

- Delirium 5Document5 pagesDelirium 5Raja Friska YulandaNo ratings yet

- EVALUATION OF THE INFLUENCE OF TWO DIFFERENT SYSTEMS OF ANALGESIA AND THE NASOGASTRIC TUBE ON THE INCIDENCE OF POSTOPERATIVE NAUSEA AND VOMITING IN CARDIAC SURGERYFrom EverandEVALUATION OF THE INFLUENCE OF TWO DIFFERENT SYSTEMS OF ANALGESIA AND THE NASOGASTRIC TUBE ON THE INCIDENCE OF POSTOPERATIVE NAUSEA AND VOMITING IN CARDIAC SURGERYNo ratings yet

- PethidineDocument9 pagesPethidineAnonymous VZtcCECtNo ratings yet

- Opoid AnalgesicsDocument29 pagesOpoid AnalgesicsShivsharan100% (1)

- An Overview of Analgesics Opioids, Tramadol, and Tapentadol (Part 2)Document7 pagesAn Overview of Analgesics Opioids, Tramadol, and Tapentadol (Part 2)幸福KoreaNo ratings yet

- Opioids: Dr. Yuri Clement, Pharmacology Unit, FMSDocument40 pagesOpioids: Dr. Yuri Clement, Pharmacology Unit, FMSUnixa BraunNo ratings yet

- List of Schedule I Drugs (US) - Wikipedia, The Free EncyclopediaDocument7 pagesList of Schedule I Drugs (US) - Wikipedia, The Free EncyclopediaterterdgdfgdfgdfgfdgNo ratings yet

- 30 10 201sdsdDocument10 pages30 10 201sdsdLuis_Javier_To_1572No ratings yet

- 6.2 Opioid & Non-OpioidsDocument18 pages6.2 Opioid & Non-OpioidsAsem AlhazmiNo ratings yet

- Annex To Travellers Guidelines 28-10-2018Document25 pagesAnnex To Travellers Guidelines 28-10-2018tomychalilNo ratings yet

- Ace InhibitorsDocument15 pagesAce InhibitorsCarolyn Conn EdwardsNo ratings yet

- Dangerous Drugs Act 1952 (Consolidated To No 23 of 1990) PDFDocument11 pagesDangerous Drugs Act 1952 (Consolidated To No 23 of 1990) PDFdesmond100% (1)

- Stok Benang Kamar OperasiDocument5 pagesStok Benang Kamar OperasirendyNo ratings yet

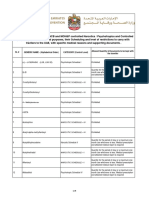

- جداول السلائف الكيميائية 23-9-2021Document28 pagesجداول السلائف الكيميائية 23-9-2021EmadNo ratings yet

- My Bioavailability ChartDocument3 pagesMy Bioavailability ChartejamesNo ratings yet

- Fisiologia de Los Opioides Epidurales e IntratectalesDocument13 pagesFisiologia de Los Opioides Epidurales e Intratectalessanjuandediosanestesia100% (5)

- Part A.2 and AnsDocument3 pagesPart A.2 and AnsluigiNo ratings yet

- Opioid Conversion ChartDocument4 pagesOpioid Conversion ChartVanessa NicoleNo ratings yet

- Makalah Bahasa Inggris Dangers of DrugsDocument19 pagesMakalah Bahasa Inggris Dangers of DrugsAri100% (3)

- Narcotic Analgesics - Notes - SY B. PharmaDocument12 pagesNarcotic Analgesics - Notes - SY B. PharmaSneha charakNo ratings yet

- Integrated Therapeutics IiiDocument11 pagesIntegrated Therapeutics IiiSalahadinNo ratings yet

- Anestesi Obat ObatanDocument72 pagesAnestesi Obat ObatanfujiNo ratings yet

- Opioids in AnaesthesiaDocument28 pagesOpioids in AnaesthesiaChhabilal BastolaNo ratings yet

- Dolcet Drug StudyDocument1 pageDolcet Drug StudyACOB, Jamil C.No ratings yet

- Antagonists Erses The Effects of Opioid Analgesics by Binding To The Opioid Receptors in The CNS, and IntravenousDocument3 pagesAntagonists Erses The Effects of Opioid Analgesics by Binding To The Opioid Receptors in The CNS, and IntravenousKwin SaludaresNo ratings yet

- c1 PDFDocument35 pagesc1 PDFNoori SabaNo ratings yet

- NarcanDocument31 pagesNarcanmahmoud fuqahaNo ratings yet

- Drugs of Addiction - Prescription Dispensing Stats AustraliaDocument3 pagesDrugs of Addiction - Prescription Dispensing Stats AustraliaKyle WilkieNo ratings yet

- Controlled Substances in Alphabetical OrderDocument17 pagesControlled Substances in Alphabetical Orderthor888888No ratings yet

- Notice: Schedules of Controlled Substances Production Quotas: Schedules I and II— 2006 AggregateDocument4 pagesNotice: Schedules of Controlled Substances Production Quotas: Schedules I and II— 2006 AggregateJustia.comNo ratings yet

- Opioid AnalgesicsDocument29 pagesOpioid AnalgesicsamonlisaNo ratings yet