Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Internalized Oppression and Latino/as by Laura M. Padilla Reading Concepts & Questions

Internalized Oppression and Latino/as by Laura M. Padilla Reading Concepts & Questions

Uploaded by

raunchy4929Copyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- The Latino Threat: Constructing Immigrants, Citizens, and the Nation, Second EditionFrom EverandThe Latino Threat: Constructing Immigrants, Citizens, and the Nation, Second EditionRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Swot AnalysisDocument3 pagesSwot AnalysisJasmin Celedonio Laurente100% (8)

- Systemic Racism 101: A Visual History of the Impact of Racism in AmericaFrom EverandSystemic Racism 101: A Visual History of the Impact of Racism in AmericaRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (5)

- Summary of American Marxism: by Mark R. Levin - A Comprehensive SummaryFrom EverandSummary of American Marxism: by Mark R. Levin - A Comprehensive SummaryNo ratings yet

- Niche Strategies From Praxis Project's Fair Game ToolkitDocument6 pagesNiche Strategies From Praxis Project's Fair Game ToolkitsolrakNo ratings yet

- The Anti-Suffragist PapersDocument5 pagesThe Anti-Suffragist Papersraunchy4929No ratings yet

- Bateman Et Al 2017-ContentsDocument6 pagesBateman Et Al 2017-ContentsJuan Carlos GilNo ratings yet

- Behaviorally Anchored Rating ScalesDocument5 pagesBehaviorally Anchored Rating ScalesAarti Bhoria100% (2)

- FWD - 441 Final Paper - Racism and Social Work PracticeThis 8-10 Page TUESDAYDocument13 pagesFWD - 441 Final Paper - Racism and Social Work PracticeThis 8-10 Page TUESDAYNathan RonoNo ratings yet

- Untitled Document 4Document3 pagesUntitled Document 4api-506756171No ratings yet

- The Impact of Racism in The United StatesDocument9 pagesThe Impact of Racism in The United Statesapi-253195322No ratings yet

- Racism: Tools To Identify and Tools To Work To Undo RacismDocument60 pagesRacism: Tools To Identify and Tools To Work To Undo RacismMuh AkbarNo ratings yet

- Media Aggressions Against The Latino Community by Tlecoz HuitzilDocument2 pagesMedia Aggressions Against The Latino Community by Tlecoz HuitzilTlecoz HuitzilNo ratings yet

- Confessions of a Recovering Racist: What White People Must Do to Overcome Racism in AmericaFrom EverandConfessions of a Recovering Racist: What White People Must Do to Overcome Racism in AmericaNo ratings yet

- Race Discrimination ThesisDocument8 pagesRace Discrimination Thesisnicolekingjackson100% (2)

- Online Discussion 12Document2 pagesOnline Discussion 12Larissa MejiaNo ratings yet

- Opinion Piece 2Document1 pageOpinion Piece 2api-302487205No ratings yet

- River Point WriterDocument8 pagesRiver Point WriterDonna Rex ReillyNo ratings yet

- p1 EssayDocument8 pagesp1 Essayapi-705904680No ratings yet

- p1 PromptDocument4 pagesp1 Promptapi-705904680No ratings yet

- Native American Plights: The Struggle Against Inequality and RacismFrom EverandNative American Plights: The Struggle Against Inequality and RacismNo ratings yet

- Research Paper On Racism in The WorkplaceDocument9 pagesResearch Paper On Racism in The Workplacehumin1byjig2100% (1)

- SW 3110 Diversityoppression and Social JusticeDocument15 pagesSW 3110 Diversityoppression and Social Justiceapi-286703035No ratings yet

- Latino Leadership-Carlos Galindo Part IIDocument5 pagesLatino Leadership-Carlos Galindo Part IICarlos GalindoNo ratings yet

- CJHS430 Hate Group Paperweek2finalDocument7 pagesCJHS430 Hate Group Paperweek2finalJame smith100% (1)

- The Immigration Crucible: Transforming Race, Nation, and the Limits of the LawFrom EverandThe Immigration Crucible: Transforming Race, Nation, and the Limits of the LawNo ratings yet

- Why Use This Approach?Document4 pagesWhy Use This Approach?MarujaNo ratings yet

- Critics Argue That Groups Based On A Particular Shared IdentityDocument5 pagesCritics Argue That Groups Based On A Particular Shared IdentityJade Sanico BaculantaNo ratings yet

- Hate Groups in TennesseeDocument12 pagesHate Groups in Tennesseeapi-311958168No ratings yet

- Final Essay 2Document6 pagesFinal Essay 2api-427948812No ratings yet

- The Radical Center: Middle Americans and the Politics of AlienationFrom EverandThe Radical Center: Middle Americans and the Politics of AlienationNo ratings yet

- ESSAY - White Latinos - 6 Harv. Latino L. Rev. 1Document6 pagesESSAY - White Latinos - 6 Harv. Latino L. Rev. 1urayoannoelNo ratings yet

- PaperrrDocument17 pagesPaperrrTayla BloomNo ratings yet

- XHERCIS MÉNDEZ Decolonial Feminist Movidas A Caribena Rethinks PrivilegeDocument27 pagesXHERCIS MÉNDEZ Decolonial Feminist Movidas A Caribena Rethinks PrivilegeChirley MendesNo ratings yet

- Reflection EssayDocument8 pagesReflection Essayapi-193600129No ratings yet

- RacismDocument4 pagesRacismDoctora ArjNo ratings yet

- Essay 2 Final Draft v3Document5 pagesEssay 2 Final Draft v3api-582099934No ratings yet

- Pols-238 Research PaperDocument13 pagesPols-238 Research Paperapi-642932790No ratings yet

- Final Essay 2Document6 pagesFinal Essay 2api-427948812No ratings yet

- Environment, Development and Society, HUL275 Part-IIDocument59 pagesEnvironment, Development and Society, HUL275 Part-IIUrooj AkhlaqNo ratings yet

- Racism Research Paper PDFDocument4 pagesRacism Research Paper PDFafeasdvym100% (1)

- Chapter 13-1Document2 pagesChapter 13-1api-280925165No ratings yet

- Final Paper, Ethnic StudiesDocument8 pagesFinal Paper, Ethnic StudiesLizetteNo ratings yet

- Racism in America Thesis StatementDocument4 pagesRacism in America Thesis Statementjessicalopezdesmoines100% (2)

- Informational PresentationDocument10 pagesInformational Presentationapi-495325406No ratings yet

- Immigration and DiversityDocument4 pagesImmigration and Diversitylime20No ratings yet

- Crime & Reason: a Black Choice: An Introduction to the Birth of Black on Black Crime and Social DysfunctionFrom EverandCrime & Reason: a Black Choice: An Introduction to the Birth of Black on Black Crime and Social DysfunctionNo ratings yet

- WWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWDocument3 pagesWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWzoran0706No ratings yet

- Hive Mentality and The Dangers of GroupthinkDocument12 pagesHive Mentality and The Dangers of GroupthinkMadiNo ratings yet

- Eos Helping Our OppressorsDocument4 pagesEos Helping Our OppressorsMalik AliNo ratings yet

- Module 7 - RevisedDocument5 pagesModule 7 - RevisedOksana SavanchukNo ratings yet

- South American Research Paper TopicsDocument6 pagesSouth American Research Paper Topicszyfepyfej0p2100% (1)

- Link-Up 2 Lift-Up: Sorting Through Our Culture Kingdom for Our Future GenerationsFrom EverandLink-Up 2 Lift-Up: Sorting Through Our Culture Kingdom for Our Future GenerationsNo ratings yet

- Analysisof Latino Anti BlacknessDocument7 pagesAnalysisof Latino Anti Blacknessbrandon vazquezNo ratings yet

- Thesis Statement Racism AmericaDocument8 pagesThesis Statement Racism Americaelizabethkennedyspringfield100% (2)

- Dominant and Subordinate Group Analysis Reflection Paper 1Document6 pagesDominant and Subordinate Group Analysis Reflection Paper 1api-300013097No ratings yet

- Working With All Families: Developing Cultural CompetenceDocument15 pagesWorking With All Families: Developing Cultural CompetenceJames CollinsNo ratings yet

- RHYTHM - A Way Forward: FORWARDNOMICS through Cultural Competence and Teams Brings YOU More Money, Power, Influence & HEALINGFrom EverandRHYTHM - A Way Forward: FORWARDNOMICS through Cultural Competence and Teams Brings YOU More Money, Power, Influence & HEALINGNo ratings yet

- Summary of Why Are All the Black Kids Sitting Together in the Cafeteria? by Beverly Daniel Tatum:And Other Conversations About Race: A Comprehensive SummaryFrom EverandSummary of Why Are All the Black Kids Sitting Together in the Cafeteria? by Beverly Daniel Tatum:And Other Conversations About Race: A Comprehensive SummaryNo ratings yet

- ETH125 w6 Society WorksheetDocument2 pagesETH125 w6 Society WorksheetMariah Cranford100% (1)

- Class: Power, Privilege, and InfluenceDocument4 pagesClass: Power, Privilege, and InfluenceMichelle Watkins0% (1)

- Chum or Pal. This Goes Onto Paragraph Five Discussing How She Finds Herself Doing The ExactDocument2 pagesChum or Pal. This Goes Onto Paragraph Five Discussing How She Finds Herself Doing The Exactraunchy4929No ratings yet

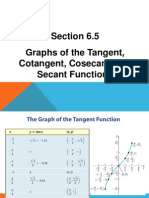

- 6.5 Graph Other Trig FunctionsDocument13 pages6.5 Graph Other Trig Functionsraunchy4929No ratings yet

- 8.2 Law of SinesDocument24 pages8.2 Law of Sinesraunchy4929No ratings yet

- 7.1 Inverese Trig FunctionDocument28 pages7.1 Inverese Trig Functionraunchy4929No ratings yet

- Reconstituting The Equal Rights Amendment R.W Francis QsDocument6 pagesReconstituting The Equal Rights Amendment R.W Francis Qsraunchy4929No ratings yet

- 6.6 Sine Cosine ShiftDocument24 pages6.6 Sine Cosine Shiftraunchy4929No ratings yet

- Growth and Linkage of The East Tanka FauDocument14 pagesGrowth and Linkage of The East Tanka FauJoshua NañarNo ratings yet

- Periodic Answer Key (Editable)Document44 pagesPeriodic Answer Key (Editable)coleenmaem.04No ratings yet

- WK 40 - The Dream of Hamzah Bin Habib Al-ZayyatDocument2 pagesWK 40 - The Dream of Hamzah Bin Habib Al-ZayyatE-Tilawah AcademyNo ratings yet

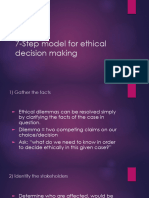

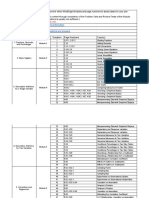

- 7-Step Model For Ethical Decision MakingDocument14 pages7-Step Model For Ethical Decision MakingjermorenoNo ratings yet

- Victorian Compromise and Literary Movements PDFDocument2 pagesVictorian Compromise and Literary Movements PDFChuii MuiiNo ratings yet

- 12 Rotations PDFDocument4 pages12 Rotations PDFBrandeice BarrettNo ratings yet

- Anna Hazare Brother HazareDocument15 pagesAnna Hazare Brother HazareH Janardan PrabhuNo ratings yet

- Strong Tie Ltd-03 16 2015Document2 pagesStrong Tie Ltd-03 16 2015Niomi Golrai100% (1)

- COTDocument19 pagesCOTAF Dowell Mirin0% (1)

- Foreign Direct Investment in Nepal: Social Inquiry: Journal of Social Science ResearchDocument20 pagesForeign Direct Investment in Nepal: Social Inquiry: Journal of Social Science Researchjames smithNo ratings yet

- C955 Pre-Assessment - MindEdge Alignment Table - Sheet1Document3 pagesC955 Pre-Assessment - MindEdge Alignment Table - Sheet1Robert Allen Rippey0% (1)

- IRTAZA Final Proposal Pet InsuranceDocument7 pagesIRTAZA Final Proposal Pet InsuranceZainab QayyumNo ratings yet

- Wellness Campus Song LyricsDocument2 pagesWellness Campus Song LyricsIshmael NarioNo ratings yet

- Assignment-2 (Cost Accounting)Document24 pagesAssignment-2 (Cost Accounting)Iqra AbbasNo ratings yet

- Further ReadingDocument7 pagesFurther ReadingPablo PerdomoNo ratings yet

- The Philippine Marketing Environment: Bruto, Ivy Marijoyce Magtibay, Sarah Jane Guno, RhizaDocument26 pagesThe Philippine Marketing Environment: Bruto, Ivy Marijoyce Magtibay, Sarah Jane Guno, Rhizakenghie tv showNo ratings yet

- Conversion Optimization FrameworkDocument34 pagesConversion Optimization FrameworkKavya GopakumarNo ratings yet

- 24 LC 16Document32 pages24 LC 16josjcrsNo ratings yet

- End Term Question Paper Linux For Devices 2021Document2 pagesEnd Term Question Paper Linux For Devices 2021KeshavNo ratings yet

- Proof of CashDocument9 pagesProof of CashEDGAR ORDANELNo ratings yet

- CV - Banjubi Boruah - FMS - NIFT - Shillong PDFDocument2 pagesCV - Banjubi Boruah - FMS - NIFT - Shillong PDFruchi mishraNo ratings yet

- YOUTH AbbreviationDocument23 pagesYOUTH AbbreviationKen ElectronNo ratings yet

- STRAMADocument4 pagesSTRAMALimuel Talastas DeguzmanNo ratings yet

- Anchoring Structures: EM 1110-2-2100 1 December 2005Document20 pagesAnchoring Structures: EM 1110-2-2100 1 December 2005Edson HuertaNo ratings yet

- The New House of Money - Chapter 2 - Jim ChanosDocument35 pagesThe New House of Money - Chapter 2 - Jim ChanosZerohedge100% (2)

- Major in Social Studies Room AssignmentDocument24 pagesMajor in Social Studies Room AssignmentPRC Baguio100% (1)

- Why & What Is Cooperative Learning at The Computer: Teaching TipsDocument8 pagesWhy & What Is Cooperative Learning at The Computer: Teaching Tipsapi-296655270No ratings yet

Internalized Oppression and Latino/as by Laura M. Padilla Reading Concepts & Questions

Internalized Oppression and Latino/as by Laura M. Padilla Reading Concepts & Questions

Uploaded by

raunchy4929Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Internalized Oppression and Latino/as by Laura M. Padilla Reading Concepts & Questions

Internalized Oppression and Latino/as by Laura M. Padilla Reading Concepts & Questions

Uploaded by

raunchy4929Copyright:

Available Formats

Internalized Oppression and Latino/as by Laura M.

Padilla

Reading Concepts & Questions

1. Define and describe internalized oppression. What features are shared by all minority groups? What features

exist particularly in the Latino community?

2. From where does internalized oppression come initially?

3. How does internalized oppression impact both the group and the individual?

4. How has the desirability of whiteness impacted minority groups leadership and ability to come together to

advocate for their own interest?

a. How have Latino/as succumbed to the conditioning that Whiter is better without even realizing it? If you

are a member of a racial or ethnic minority group, how have you experienced the white is good

phenomenon? How have you attempted to deconstruct or defy this phenomenon?

b. What is passing? Why would members of minority groups want to pass? What are the two primary

flaws in the goal of passing?

5. What is the envidia phenomenon? How does this and the impostor dilemma sabotage both individual and

community well-being?

6. How does both the assimiliationist ideal and pride/preservationist thinking keep Latino/as oppressed?

Internalized oppression has been the primary means by which we [Latino/as] have been forced to perpetuate and "agree"

to our own oppression. In order to understand the many ways in which internalized oppression and racism affect

subordinated communities, it is important to have a general background on these forces. Thus, this article will describe

internalized oppression generally and will then describe how internalized oppression is particularly manifested in the

Latino community. This will better allow the reader to comprehend why Latino/as engage in the specific types of self-

destructive behavior described throughout this article.

While many negative stereotypes apply to all races and ethnicities encompassed by the term "Latino/a," this article

loosely uses "Latino/a" mostly to describe Mexican-Americans, including recent immigrants. There are many reasons for

this focus. I am Mexican-American and live in the border city of San Diego, so my experience and familiarity is primarily

with Mexican-American and recent immigrant populations. Also, "[t]he oldest and by far the largest segment of the

Latino population is, of course, the Mexican-Americans, accounting for almost two-thirds of all Latino/as."

Working Definitions of Internalized Oppression and Racism

When someone experiences a hurt that is not healed, distress patterns emerge whereby the person engages in some type

of harmful behavior. Internalized oppression has been described as the process by which these patterns reveal

themselves. "These distress patterns, created by oppression and racism..., have been played out... in two places.... First,

upon members of our own group particularly... those over whom we have some degree of power or control... Second,

upon ourselves through all manner of self-invalidation, self-doubt, isolation, fear, feelings of powerlessness and

despair...."

Thus, internalized oppression commences externally. In other words, dominant players start the chain of oppression

through racist and discriminatory behavior. This behavior could range from physical violence prompted by the victim's

race, to race-based exclusion, to derogatory race-based name calling and stereotyping (such as "we don't need any more

wetbacks they just take away our jobs"), together with capitalization on the fears created by those stereotypes.

Those at the receiving end of prejudice can experience physical and psychological harm, and over time, they internalize

and act on negative perceptions about themselves and other members of their own group. How might internalized

oppression appear generally that is, not in regards to a particular ethnic or racial group? Patterns of internalized

racism cause adults to find fault, criticize and invalidate each other. This invariably happens when we come together in a

group to address some important problem or undertake some liberation project. What often follows is divisiveness and

disunity leading to despair and abandonment of the effort.

"Patterns of internalized oppression cause us to attack, criticize or have unrealistic expectations of anyone who has the

courage to step forward and take on leadership responsibilities. This leads to a lack of support that is absolutely

necessary for effective leadership to emerge and group strength to grow. It also leads directly to the "burnout"

phenomenon we have all witnessed, or experienced as effective leaders."

Internalized Racism and Latino/as

Internalized oppression operates rather uniformly at both the group and individual levels regardless of ethnicity,

gender or sexual orientation through some common behavioral patterns. However, it also manifests itself uniquely

depending on the negative stereotypes it causes a particular group to internalize. Latino/as' specific history gives rise to

the particularities of our internalized oppression and racism. We "share a unique experience of oppression and survival

in the United States. Mexicans and Puerto Ricans, who constitute the largest and oldest Latino/a communities within the

official borders of the United States, were attacked, invaded, colonized, annexed and exploited by the U.S."

This

oppressive behavior toward Latino/as is deep-rooted. Jeanne Guana elaborates:

[A]fter the Mexican American War ended in 1848, people of Mexican origin faced lynchings, land theft and

virulent racism. Later, in times of economic depression, people of Mexican origin citizens and non-

citizens alike were deported en masse... As a result, many Mexican-origin people internalized the racism

and learned to despise all things Mexican.

Despising all things native to ourselves causes unhealthy behavior, including self-loathing and participation in the

perpetuation of negative stereotypes. Latino/as may be conditioned to believe that other Latino/as particularly recent

immigrants are taking jobs away from U.S. citizens or are unfairly taking advantage of U.S. social services.

Additionally, we may refrain from using Spanish in professional settings because it will betray our heritage, or we may

believe that Whiter is better. "From the Latino/a viewpoint, the desirability of whiteness represents the internalization by

the colonized of the colonizers' predilections."

The next part of this section will provide greater detail on ways that

internalized racism affects the Latino community, both at the group and individual levels.

The Group Level

At the group level, internalized oppression and racism involve harmful or destructive conduct by members of a group

directed at other members of the same group. "[Internalized racism] has been a major ingredient in the distressful and

unworkable relationships which we so often have with each other. It has proved to be the fatal stumbling block of every

promising and potentially powerful liberation effort that has failed in the past."

Internalized racism thwarts Latino/as empowerment efforts. For example, Latino/a groups often wither when leadership

issues revolve around how "ethnic" one is. At California Western School of Law, one year a majority of the La Raza law

students refused to elect a blond student to a board position because she was not perceived to be "Mexican" enough, even

though she was born in Mexico, spoke better Spanish than most of her classmates, and was a committed activist. The

experience was devastating. Internalized oppression and politics of race impeded her advancement and prevented her

from performing work that would have benefited the Latino/a community. I have seen the same politics of race emerge

among members of La Raza Lawyers of San Diego. A member's credibility was frequently based on whether they were

perceived as either "too dark" or "too light," depending on the issue.

Group-level internalized racism also reveals itself through the way Latino/as view other Latino/as. For instance, many

people in the Latino community believe the tired propaganda that Latino/a immigrants are a drain on social services. As

far back as 1913, "the Commissioner of Immigration... publicly announced his fear that Mexicans might become public

charges, since according to these authorities, Mexicans came to the U.S. only to receive public relief."

8

Today, many

Americans harbor that same belief about recent immigrants, and too many Latino/as believe it. If those who believe this

propaganda were to look beyond the myths to the facts, they would learn that many immigrants contribute more to our

society than they receive.

One expert estimates "that immigration brings economic benefits to the U.S. in the range of $6 to $20 billion annually

small, but still a net positive gain."

Moreover, there is overwhelming evidence that undocumented immigrants pay more

in taxes than they receive in public benefits. When researching campaigns to limit immigration, Richard Delgado and

Jean Stefancic found that even conservative think tanks concluded that "immigration is a net benefit, not a drawback to

the regions in which immigrants settle."

The Individual Level

Internalized racism in the Latino/a community also reveals itself at the individual level. For example, nearly half of all

Hispanics consider themselves White. More telling, there is a great deal of self-loathing tied to the darkness of one's skin.

One Mexican American, who asserted that he "would have been only too happy to look as Mexican as my light-skinned

older brother," admitted that he felt "shame and sexual inferiority... because of my dark complexion." He continued

describing himself: "With disgust... I would come face to face with myself in mirrors. With disappointment I located

myself in class photographs my dark face undefined by the camera which had clearly described the white faces of

classmates. Or I'd see my dark wrist against my long-sleeved white shirt."

At a more personal level, I have heard friends and family attempt to one-up each other about how "gero" their children

or grandchildren are. I remember my mother's best friend bragging about how gera her first granddaughter was as she

pulled out a photograph of a hirsute, dark baby. Rather than ask each other why her friend felt the need to assert her

granddaughter's "gera-ness," my mother and I instead later compared the granddaughter's "gera-ness" to the "gera/o-

ness" of our own family members. We succumbed to the conditioning that Whiter is better without even realizing it. We

also use a grading process brought about by this conditioning to rank the acceptability of boyfriends, girlfriends, spouses

and partners. Lighter is preferred; darker is grudgingly accepted so long as that person is Latino/a. To go any darker may

put one at the risk of family alienation.

We have been conditioned at many levels and for many centuries to believe that lighter skin is more desirable. Although

some may be puzzled as to why Latino/as would perpetuate that belief, it is readily explained. "...minorities have often

sought to 'pass' as White... because they thought that becoming White insured greater economic, political and social

security. Becoming White, they thought, meant gaining access to a whole set of public and private privileges and was

away to avoid being the object of others' domination. Whiteness, therefore, constituted a privileged identity." Survival

instincts coupled with an unquestioned acceptance of liberal ideology promoting pursuit of individual well-being pushes

us to claim a White identity. Yet a critical analysis of that pursuit reveals some flaws in the goal. Most fundamentally,

that goal asks us to forfeit our cultural and ethnic identity. Another flaw is that it assumes that even if one wanted to

"pass" for purposes of obtaining White privilege, the privilege would follow. Even if Latino/as self-identify as White, they

cannot control how others see them. So long as they are viewed as Latino/a, they will not obtain the White privilege that

they crave. Here lies the greatest risk of all, as one could lose one's ethnic and familial identity without ever achieving

one's desired identity, thus leaving an untethered soul who fits in nowhere.

Even if one does not attempt to "pass," one can consciously or subconsciously attempt to acquire White privilege through

the choice of a spouse

I married an Anglo and in reflecting on why I married my husband, I realize that the reasons are many, complex and

positive, and that I never consciously chose not to marry a Latino. However, it is not as clear to me whether I

subconsciously chose not to marry a Latino. During law school, I spent countless hours with my Latino classmates and

one year I co-chaired the Stanford Latino Law Students' Association (SLLSA), but I did not date my Latino classmates.

One reason was that there were not many Latinos at the law school and many of the few had girlfriends. Another reason

that I reveal with reluctance is that I saw too many marriages in my family break up because of the man's infidelity.

Of course many non-Latino men are unfaithful, and I never believed that all Latino males were unfaithful, but my family

history made me nervous. When I experience this unease, am I unconsciously succumbing to internalized racism by

believing negative stereotypes about Latino men? My need to ask this question reveals one of the dangers of internalized

oppression we frequently do not even realize when or how we are prejudiced against ourselves.

Other manifestations of internalized racism include behavior resulting from "envidia," or jealousy. Latino/as, for instance,

frequently inwardly, and sometimes outwardly, question the qualifications of other successful Latino/as. It is heartening

that this is not uniform many Latino/as provide mutual support networks by, for example, intentionally and

systematically referring business to each other. Nonetheless, we too frequently neglect to provide support for each other

and even worse, we actually conspire against each other. This tendency is illustrated by a popular Mexican folk story:

A man stumbles upon a fisherman who is gathering crabs and placing them in a bucket with no lid. When the passerby

asks the fisherman whether he is concerned that the crabs might climb out of the bucket and crawl away, the fisherman

replies that there is no need to worry. "You see," he says, "these are Mexican crabs. Whenever one of them tries to move

up, the others pull him down..."

The envidia phenomenon sabotages Latino/a unity and requires our attention. We need to challenge negative stereotypes

about Latino/as, refuse to perpetuate negative stereotypes about other Latino/as, recognize sabotaging behavior among

ourselves, and convert that behavior and the environment that promotes it into a supportive environment.

Internalized racism is also displayed when Latino/as experience self-doubt upon receiving either admission into a top

university or a prestigious job offer. This "impostor" dilemma haunts many of us. How did I get here? Do I truly belong?

The answers, respectively, are through hard work and perhaps some serendipity, and yes. However, because of

internalized racism, we doubt our qualifications and hard-earned credentials and succumb to the often not-very-delicate

suggestions that we do not belong.

We also denigrate ourselves through both our treatment of the Spanish language and our support of the English-only

movement. By the former, I mean that Latino/as can cavalierly use Spanish when convenient for example, to

temporarily bond with other Latino/as while also being ashamed by it when it reveals too much of our heritage. Through

support of the English- only movement, we send the message that we should be ashamed of our inherited language.

When we support this movement, we admit Latino/a inferiority and accept the notion that Latino/as are "dangerous

because of their language. It perceives the Spanish language as a threatening foreign influence that must be eradicated to

preserve cultural purity."

Accordingly, internalized racism causes Latino/as to distance themselves from the Spanish language. This distancing

increases as income rises and assimilation becomes more complete. As one study indicates, "Almost 40 percent of

Latino/a respondents prefer English as their dominant language, and 92 percent prefer either monolingual English or

bilingual English and Spanish... Over time, and as Latino/a socioeconomic status improves, Latino/a language

preferences, while bilingual, move closer to an English predominance..."

14

Latino/as who intentionally distance

themselves from Spanish accept "the assimilationist ideal [that] would have Latino/as learn English and completely lose

their Spanish-speaking ability."

15

Rather than being a source of embarrassment, as one academic suggested, our language

should be a source of cultural pride; "Latino/as must learn to celebrate their language if they are to find strength in their

common identity." When we accept these stereotypes about ourselves and other Latino/as, we accept the "colonized

mentality" and engage in actions consistent with internalized racism. These actions are harmful in and of themselves, and

the consequences can be even more severe when the stakes are higher for example, when legislation is proposed that

directly harms the Latino/a community, and worse, when Latino/as support that legislation.

This self-destructive behavior forces Latino/as to spend too much time on the defensive, reacting to racist behavior, not

only from others, but from ourselves. The unfortunate reality is that racism will be with us indefinitely and we will

always have to spend some time reacting to bigoted legislation, and fighting subordination and discrimination. But we

should not have to spend so much time and energy fighting among ourselves. It is time to act more from a position of

self-determination. If Latino/as can spend less time in-fighting and convincing other Latino/as not to support measures

that are harmful to the Latino/a community, we will be freed up to engage in positive activities and can initiate pro-active

efforts to empower the Latino/a community. Accordingly, we should defy and deny others' negative perceptions of

Latino/as, while concurrently building positive images and working toward a better place for Latino/as in our society.

Laura Padilla is a full professor at California Western School of Law where she specializes in property rights, race and gender. An unabridged version of this article first appeared in the Texas

Hispanic Journal of Law and Policy 61-113, 65-73 (Fall 2001).

From The Diversity Factor Volume 12, Number 3 Summer 2004 Published by Elsie Y. Cross & Associates, Inc.

You might also like

- The Latino Threat: Constructing Immigrants, Citizens, and the Nation, Second EditionFrom EverandThe Latino Threat: Constructing Immigrants, Citizens, and the Nation, Second EditionRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Swot AnalysisDocument3 pagesSwot AnalysisJasmin Celedonio Laurente100% (8)

- Systemic Racism 101: A Visual History of the Impact of Racism in AmericaFrom EverandSystemic Racism 101: A Visual History of the Impact of Racism in AmericaRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (5)

- Summary of American Marxism: by Mark R. Levin - A Comprehensive SummaryFrom EverandSummary of American Marxism: by Mark R. Levin - A Comprehensive SummaryNo ratings yet

- Niche Strategies From Praxis Project's Fair Game ToolkitDocument6 pagesNiche Strategies From Praxis Project's Fair Game ToolkitsolrakNo ratings yet

- The Anti-Suffragist PapersDocument5 pagesThe Anti-Suffragist Papersraunchy4929No ratings yet

- Bateman Et Al 2017-ContentsDocument6 pagesBateman Et Al 2017-ContentsJuan Carlos GilNo ratings yet

- Behaviorally Anchored Rating ScalesDocument5 pagesBehaviorally Anchored Rating ScalesAarti Bhoria100% (2)

- FWD - 441 Final Paper - Racism and Social Work PracticeThis 8-10 Page TUESDAYDocument13 pagesFWD - 441 Final Paper - Racism and Social Work PracticeThis 8-10 Page TUESDAYNathan RonoNo ratings yet

- Untitled Document 4Document3 pagesUntitled Document 4api-506756171No ratings yet

- The Impact of Racism in The United StatesDocument9 pagesThe Impact of Racism in The United Statesapi-253195322No ratings yet

- Racism: Tools To Identify and Tools To Work To Undo RacismDocument60 pagesRacism: Tools To Identify and Tools To Work To Undo RacismMuh AkbarNo ratings yet

- Media Aggressions Against The Latino Community by Tlecoz HuitzilDocument2 pagesMedia Aggressions Against The Latino Community by Tlecoz HuitzilTlecoz HuitzilNo ratings yet

- Confessions of a Recovering Racist: What White People Must Do to Overcome Racism in AmericaFrom EverandConfessions of a Recovering Racist: What White People Must Do to Overcome Racism in AmericaNo ratings yet

- Race Discrimination ThesisDocument8 pagesRace Discrimination Thesisnicolekingjackson100% (2)

- Online Discussion 12Document2 pagesOnline Discussion 12Larissa MejiaNo ratings yet

- Opinion Piece 2Document1 pageOpinion Piece 2api-302487205No ratings yet

- River Point WriterDocument8 pagesRiver Point WriterDonna Rex ReillyNo ratings yet

- p1 EssayDocument8 pagesp1 Essayapi-705904680No ratings yet

- p1 PromptDocument4 pagesp1 Promptapi-705904680No ratings yet

- Native American Plights: The Struggle Against Inequality and RacismFrom EverandNative American Plights: The Struggle Against Inequality and RacismNo ratings yet

- Research Paper On Racism in The WorkplaceDocument9 pagesResearch Paper On Racism in The Workplacehumin1byjig2100% (1)

- SW 3110 Diversityoppression and Social JusticeDocument15 pagesSW 3110 Diversityoppression and Social Justiceapi-286703035No ratings yet

- Latino Leadership-Carlos Galindo Part IIDocument5 pagesLatino Leadership-Carlos Galindo Part IICarlos GalindoNo ratings yet

- CJHS430 Hate Group Paperweek2finalDocument7 pagesCJHS430 Hate Group Paperweek2finalJame smith100% (1)

- The Immigration Crucible: Transforming Race, Nation, and the Limits of the LawFrom EverandThe Immigration Crucible: Transforming Race, Nation, and the Limits of the LawNo ratings yet

- Why Use This Approach?Document4 pagesWhy Use This Approach?MarujaNo ratings yet

- Critics Argue That Groups Based On A Particular Shared IdentityDocument5 pagesCritics Argue That Groups Based On A Particular Shared IdentityJade Sanico BaculantaNo ratings yet

- Hate Groups in TennesseeDocument12 pagesHate Groups in Tennesseeapi-311958168No ratings yet

- Final Essay 2Document6 pagesFinal Essay 2api-427948812No ratings yet

- The Radical Center: Middle Americans and the Politics of AlienationFrom EverandThe Radical Center: Middle Americans and the Politics of AlienationNo ratings yet

- ESSAY - White Latinos - 6 Harv. Latino L. Rev. 1Document6 pagesESSAY - White Latinos - 6 Harv. Latino L. Rev. 1urayoannoelNo ratings yet

- PaperrrDocument17 pagesPaperrrTayla BloomNo ratings yet

- XHERCIS MÉNDEZ Decolonial Feminist Movidas A Caribena Rethinks PrivilegeDocument27 pagesXHERCIS MÉNDEZ Decolonial Feminist Movidas A Caribena Rethinks PrivilegeChirley MendesNo ratings yet

- Reflection EssayDocument8 pagesReflection Essayapi-193600129No ratings yet

- RacismDocument4 pagesRacismDoctora ArjNo ratings yet

- Essay 2 Final Draft v3Document5 pagesEssay 2 Final Draft v3api-582099934No ratings yet

- Pols-238 Research PaperDocument13 pagesPols-238 Research Paperapi-642932790No ratings yet

- Final Essay 2Document6 pagesFinal Essay 2api-427948812No ratings yet

- Environment, Development and Society, HUL275 Part-IIDocument59 pagesEnvironment, Development and Society, HUL275 Part-IIUrooj AkhlaqNo ratings yet

- Racism Research Paper PDFDocument4 pagesRacism Research Paper PDFafeasdvym100% (1)

- Chapter 13-1Document2 pagesChapter 13-1api-280925165No ratings yet

- Final Paper, Ethnic StudiesDocument8 pagesFinal Paper, Ethnic StudiesLizetteNo ratings yet

- Racism in America Thesis StatementDocument4 pagesRacism in America Thesis Statementjessicalopezdesmoines100% (2)

- Informational PresentationDocument10 pagesInformational Presentationapi-495325406No ratings yet

- Immigration and DiversityDocument4 pagesImmigration and Diversitylime20No ratings yet

- Crime & Reason: a Black Choice: An Introduction to the Birth of Black on Black Crime and Social DysfunctionFrom EverandCrime & Reason: a Black Choice: An Introduction to the Birth of Black on Black Crime and Social DysfunctionNo ratings yet

- WWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWDocument3 pagesWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWzoran0706No ratings yet

- Hive Mentality and The Dangers of GroupthinkDocument12 pagesHive Mentality and The Dangers of GroupthinkMadiNo ratings yet

- Eos Helping Our OppressorsDocument4 pagesEos Helping Our OppressorsMalik AliNo ratings yet

- Module 7 - RevisedDocument5 pagesModule 7 - RevisedOksana SavanchukNo ratings yet

- South American Research Paper TopicsDocument6 pagesSouth American Research Paper Topicszyfepyfej0p2100% (1)

- Link-Up 2 Lift-Up: Sorting Through Our Culture Kingdom for Our Future GenerationsFrom EverandLink-Up 2 Lift-Up: Sorting Through Our Culture Kingdom for Our Future GenerationsNo ratings yet

- Analysisof Latino Anti BlacknessDocument7 pagesAnalysisof Latino Anti Blacknessbrandon vazquezNo ratings yet

- Thesis Statement Racism AmericaDocument8 pagesThesis Statement Racism Americaelizabethkennedyspringfield100% (2)

- Dominant and Subordinate Group Analysis Reflection Paper 1Document6 pagesDominant and Subordinate Group Analysis Reflection Paper 1api-300013097No ratings yet

- Working With All Families: Developing Cultural CompetenceDocument15 pagesWorking With All Families: Developing Cultural CompetenceJames CollinsNo ratings yet

- RHYTHM - A Way Forward: FORWARDNOMICS through Cultural Competence and Teams Brings YOU More Money, Power, Influence & HEALINGFrom EverandRHYTHM - A Way Forward: FORWARDNOMICS through Cultural Competence and Teams Brings YOU More Money, Power, Influence & HEALINGNo ratings yet

- Summary of Why Are All the Black Kids Sitting Together in the Cafeteria? by Beverly Daniel Tatum:And Other Conversations About Race: A Comprehensive SummaryFrom EverandSummary of Why Are All the Black Kids Sitting Together in the Cafeteria? by Beverly Daniel Tatum:And Other Conversations About Race: A Comprehensive SummaryNo ratings yet

- ETH125 w6 Society WorksheetDocument2 pagesETH125 w6 Society WorksheetMariah Cranford100% (1)

- Class: Power, Privilege, and InfluenceDocument4 pagesClass: Power, Privilege, and InfluenceMichelle Watkins0% (1)

- Chum or Pal. This Goes Onto Paragraph Five Discussing How She Finds Herself Doing The ExactDocument2 pagesChum or Pal. This Goes Onto Paragraph Five Discussing How She Finds Herself Doing The Exactraunchy4929No ratings yet

- 6.5 Graph Other Trig FunctionsDocument13 pages6.5 Graph Other Trig Functionsraunchy4929No ratings yet

- 8.2 Law of SinesDocument24 pages8.2 Law of Sinesraunchy4929No ratings yet

- 7.1 Inverese Trig FunctionDocument28 pages7.1 Inverese Trig Functionraunchy4929No ratings yet

- Reconstituting The Equal Rights Amendment R.W Francis QsDocument6 pagesReconstituting The Equal Rights Amendment R.W Francis Qsraunchy4929No ratings yet

- 6.6 Sine Cosine ShiftDocument24 pages6.6 Sine Cosine Shiftraunchy4929No ratings yet

- Growth and Linkage of The East Tanka FauDocument14 pagesGrowth and Linkage of The East Tanka FauJoshua NañarNo ratings yet

- Periodic Answer Key (Editable)Document44 pagesPeriodic Answer Key (Editable)coleenmaem.04No ratings yet

- WK 40 - The Dream of Hamzah Bin Habib Al-ZayyatDocument2 pagesWK 40 - The Dream of Hamzah Bin Habib Al-ZayyatE-Tilawah AcademyNo ratings yet

- 7-Step Model For Ethical Decision MakingDocument14 pages7-Step Model For Ethical Decision MakingjermorenoNo ratings yet

- Victorian Compromise and Literary Movements PDFDocument2 pagesVictorian Compromise and Literary Movements PDFChuii MuiiNo ratings yet

- 12 Rotations PDFDocument4 pages12 Rotations PDFBrandeice BarrettNo ratings yet

- Anna Hazare Brother HazareDocument15 pagesAnna Hazare Brother HazareH Janardan PrabhuNo ratings yet

- Strong Tie Ltd-03 16 2015Document2 pagesStrong Tie Ltd-03 16 2015Niomi Golrai100% (1)

- COTDocument19 pagesCOTAF Dowell Mirin0% (1)

- Foreign Direct Investment in Nepal: Social Inquiry: Journal of Social Science ResearchDocument20 pagesForeign Direct Investment in Nepal: Social Inquiry: Journal of Social Science Researchjames smithNo ratings yet

- C955 Pre-Assessment - MindEdge Alignment Table - Sheet1Document3 pagesC955 Pre-Assessment - MindEdge Alignment Table - Sheet1Robert Allen Rippey0% (1)

- IRTAZA Final Proposal Pet InsuranceDocument7 pagesIRTAZA Final Proposal Pet InsuranceZainab QayyumNo ratings yet

- Wellness Campus Song LyricsDocument2 pagesWellness Campus Song LyricsIshmael NarioNo ratings yet

- Assignment-2 (Cost Accounting)Document24 pagesAssignment-2 (Cost Accounting)Iqra AbbasNo ratings yet

- Further ReadingDocument7 pagesFurther ReadingPablo PerdomoNo ratings yet

- The Philippine Marketing Environment: Bruto, Ivy Marijoyce Magtibay, Sarah Jane Guno, RhizaDocument26 pagesThe Philippine Marketing Environment: Bruto, Ivy Marijoyce Magtibay, Sarah Jane Guno, Rhizakenghie tv showNo ratings yet

- Conversion Optimization FrameworkDocument34 pagesConversion Optimization FrameworkKavya GopakumarNo ratings yet

- 24 LC 16Document32 pages24 LC 16josjcrsNo ratings yet

- End Term Question Paper Linux For Devices 2021Document2 pagesEnd Term Question Paper Linux For Devices 2021KeshavNo ratings yet

- Proof of CashDocument9 pagesProof of CashEDGAR ORDANELNo ratings yet

- CV - Banjubi Boruah - FMS - NIFT - Shillong PDFDocument2 pagesCV - Banjubi Boruah - FMS - NIFT - Shillong PDFruchi mishraNo ratings yet

- YOUTH AbbreviationDocument23 pagesYOUTH AbbreviationKen ElectronNo ratings yet

- STRAMADocument4 pagesSTRAMALimuel Talastas DeguzmanNo ratings yet

- Anchoring Structures: EM 1110-2-2100 1 December 2005Document20 pagesAnchoring Structures: EM 1110-2-2100 1 December 2005Edson HuertaNo ratings yet

- The New House of Money - Chapter 2 - Jim ChanosDocument35 pagesThe New House of Money - Chapter 2 - Jim ChanosZerohedge100% (2)

- Major in Social Studies Room AssignmentDocument24 pagesMajor in Social Studies Room AssignmentPRC Baguio100% (1)

- Why & What Is Cooperative Learning at The Computer: Teaching TipsDocument8 pagesWhy & What Is Cooperative Learning at The Computer: Teaching Tipsapi-296655270No ratings yet