Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Austerity For Whom

Austerity For Whom

Uploaded by

Alan ReynoldsOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Austerity For Whom

Austerity For Whom

Uploaded by

Alan ReynoldsCopyright:

Available Formats

Originally titled, Austerity for Whom?

by Alan Reynolds

Reprinted from a Spring 2013 symposium , Does Debt Matter in International Economy.

http://www.international-economy.com/TIE_Sp13_DoesDebtMatterSymp.pdf

It makes sense for households or governments to borrow in hard times and to finance long-lived

capital assets. How much they can afford to borrow does not depend on the ratio of stock of debt

to the flow of current income, but on the future cost of debt service relative to future income.

If households or governments keep borrowing against the future to stimulate demand, they end

up consuming less, not more, thanks to interest expense. Borrowing against the future is no fun

when the future arrives.

Japan proves governments can sometimes get away with taxpayer debt far larger than GDP.

Unfortunately, the prospect of rising tax rates (to pay for rising debt service) discourages efforts

and investments to increase future income. Without growing income, good debts can turn sour

with little warning, adding a default or inflation premium to borrowing costs

In 2008, The Economist juxtaposed the booming BRICs (Brazil, Russia, India, and China)

against the struggling PIGS (Portugal, Italy, Greece, and Spain). Bank bailouts in 20082010

pushed Ireland and Great Britain into the pig pen, transforming PIGS into PIIGGS. And Jim

ONeill of Goldman Sachs, who coined the BRIC acronym, recently added MIST

economiesMexico, Indonesia, South Korea, and Turkey.

Paul Krugman attributes the PIIGGS distress to austerity, implying deep government

spending cuts of the sort the United States experienced (with salutary effects) from 1992 to 2000.

What happened among the PIIGGS, by contrast, is that government spending exploded from an

average of 43.2 percent of GDP in 2007 to 52.6 percent by 2010. Even in 2012, after bank

bailouts ended, the ratio of spending to GDP among PIIGGS remained 36 percentage points

higher in 2012 than in 2007.

To describe that spending spree as austerity begs the key question: Austerity for whom? There

was no discernible austerity among the PIIGGS for government bailouts, subsidies, or

entitlements. Austerity was aimed at the private sector: The highest income tax rate was

increased by 410 percentage points in all but one of the PIIGGS (Italy).

By contrast, all but one of the BRIC and MIST countries (China) cut their highest tax rates in

half, with top tax rates now ranging from 13 to 38 percent. Revenue keeps pace with a growing

economy, and government spending can too. Yet government spending averages just 32.1

percent of GDP in the BRICs and 27.4 percent for the MIST group.

A large and rising national debt is problematic precisely because it raises the risk of higher taxes.

Turning risk into reality by raising marginal tax rates is not a solution, but the problem.

Countries with elevated debts and depressed incomes do not need larger public debts or lower

private incomes. They need to lift the market economys share of GDP over time by holding

down government consumption, transfers, and taxes.

You might also like

- Public Debt in IndiaDocument4 pagesPublic Debt in IndiaAashna DNo ratings yet

- The Real Effects of DebtDocument39 pagesThe Real Effects of DebtCsoregi NorbiNo ratings yet

- Cecchetti, Mohanty and Zampolli The Real Effects of DebtDocument34 pagesCecchetti, Mohanty and Zampolli The Real Effects of Debtas111320034667No ratings yet

- BIS - The Real Effects of DebtDocument34 pagesBIS - The Real Effects of DebtNilschikNo ratings yet

- Cecchetti, Mohanty and Zampolli 2011Document39 pagesCecchetti, Mohanty and Zampolli 2011DanielaNo ratings yet

- Def 4Document7 pagesDef 4Guezil Joy DelfinNo ratings yet

- Shouldn't Add More DebtsDocument2 pagesShouldn't Add More DebtsHendrocahyo HatsNo ratings yet

- Debt CrisisDocument2 pagesDebt CrisisAmit DwivediNo ratings yet

- Cut Deficits by Cutting SpendingDocument4 pagesCut Deficits by Cutting SpendingAdrià LópezNo ratings yet

- Mwo 123111Document13 pagesMwo 123111richardck61No ratings yet

- Unit III DISCUSSION BOARDDocument1 pageUnit III DISCUSSION BOARDVirginia EdwardsNo ratings yet

- The Cost and Benefit of Higher Government DebtDocument6 pagesThe Cost and Benefit of Higher Government Debtkacchan kannaNo ratings yet

- Kelompok: 10 (Hutang Negara) Dosen Pembimbing: Novriana SumartiDocument7 pagesKelompok: 10 (Hutang Negara) Dosen Pembimbing: Novriana Sumartiallif khairulanamNo ratings yet

- High Debt Is A Real DragDocument3 pagesHigh Debt Is A Real Dragprince marcNo ratings yet

- The Broyhill Letter - Part Duex (Q2-11)Document5 pagesThe Broyhill Letter - Part Duex (Q2-11)Broyhill Asset ManagementNo ratings yet

- Fiscal Austerity During Debt Crises: Cristina Arellano Federal Reserve Bank of MinneapolisDocument21 pagesFiscal Austerity During Debt Crises: Cristina Arellano Federal Reserve Bank of MinneapolisTBP_Think_TankNo ratings yet

- Quarterly Review and Outlook: High Debt Leads To RecessionDocument5 pagesQuarterly Review and Outlook: High Debt Leads To RecessiongregoryalexNo ratings yet

- Agcapita April 2010Document11 pagesAgcapita April 2010Capita1No ratings yet

- DebtsDocument14 pagesDebtsMohamed AzmyNo ratings yet

- B. Tech Cs Vi Semester (Section - C) Eco307 Fundamentals of Economics Assignment - 1Document6 pagesB. Tech Cs Vi Semester (Section - C) Eco307 Fundamentals of Economics Assignment - 1Vartika AgrawalNo ratings yet

- Unit 2. Lesson 3Document4 pagesUnit 2. Lesson 3halam29051997No ratings yet

- HIM2016Q1NPDocument9 pagesHIM2016Q1NPlovehonor0519No ratings yet

- Economics Handout Public Debt: The Debt Stock Net Budget DeficitDocument6 pagesEconomics Handout Public Debt: The Debt Stock Net Budget DeficitOnella GrantNo ratings yet

- Understanding The Int'l MacroeconomyDocument4 pagesUnderstanding The Int'l MacroeconomyNicolas ChengNo ratings yet

- Effects of Public Debt On Economic Growth in Nigeria 94c5afe9Document24 pagesEffects of Public Debt On Economic Growth in Nigeria 94c5afe9projectevaluation247No ratings yet

- R-G 0: Can We Sleep More Soundly?: by Paolo Mauro and Jing ZhouDocument32 pagesR-G 0: Can We Sleep More Soundly?: by Paolo Mauro and Jing ZhoutegelinskyNo ratings yet

- G24 Policy Brief 65 04 09 2012Document4 pagesG24 Policy Brief 65 04 09 2012SRI MURWANI PUSPASARINo ratings yet

- Averting A Fiscal Crisis - Why America Needs Comprehensive Fiscal Reform Now 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0Document53 pagesAverting A Fiscal Crisis - Why America Needs Comprehensive Fiscal Reform Now 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0Committee For a Responsible Federal BudgetNo ratings yet

- A Compariosn of Debt-To-Gdp Ratio Between Us and Other CountriesDocument6 pagesA Compariosn of Debt-To-Gdp Ratio Between Us and Other CountriesNobert BulindaNo ratings yet

- Covid 19Document6 pagesCovid 19Ngọc Thảo NguyễnNo ratings yet

- Two Major Issues of Fiscal Policy and Potential Harms To The EconomyDocument10 pagesTwo Major Issues of Fiscal Policy and Potential Harms To The Economysue patrickNo ratings yet

- Sprott 2013 P1 Ignoring The ObviousDocument7 pagesSprott 2013 P1 Ignoring The ObviouscasefortrilsNo ratings yet

- The Relationship Between Public Debt and Economic Growth in KenyaDocument21 pagesThe Relationship Between Public Debt and Economic Growth in KenyavanderwijhNo ratings yet

- The Economic Impact of The PandemicDocument5 pagesThe Economic Impact of The Pandemick.agnes12No ratings yet

- Lecture 13Document35 pagesLecture 13Mohammad NurzamanNo ratings yet

- Econometrics Term Paper For The Effects of Debt On PovertyDocument8 pagesEconometrics Term Paper For The Effects of Debt On PovertyTynoe ZiweweNo ratings yet

- 1886-Article Text-3388-3653-10-20230112Document11 pages1886-Article Text-3388-3653-10-20230112Ana StanNo ratings yet

- No Cong o CambodiaDocument35 pagesNo Cong o CambodiaVũ CôngNo ratings yet

- Sovereign Debt Crises Are Coming: A Report by The Economist Intelligence UnitDocument10 pagesSovereign Debt Crises Are Coming: A Report by The Economist Intelligence UnitAndrea BodaNo ratings yet

- HIM2016Q1Document7 pagesHIM2016Q1Puru SaxenaNo ratings yet

- Impact of Public Debt On The Economic Growth of PakistanDocument24 pagesImpact of Public Debt On The Economic Growth of PakistanSadiya AzharNo ratings yet

- SSRN Id4447361Document17 pagesSSRN Id4447361Okechukwu LovedayNo ratings yet

- Shahor 2018Document12 pagesShahor 2018Maximiliano PfannlNo ratings yet

- ch001Document11 pagesch001Pelausa, Charlene Mae, AB12A1No ratings yet

- Intro Fiscal Policy o-WPS OfficeDocument7 pagesIntro Fiscal Policy o-WPS OfficeJohn NjorogeNo ratings yet

- Pension Fund Crisis in UsaDocument5 pagesPension Fund Crisis in UsaHa PhamNo ratings yet

- Mid SemDocument11 pagesMid SemUdeshi ShermilaNo ratings yet

- Rineesh Uog - Essay Project - EditedDocument9 pagesRineesh Uog - Essay Project - EditedJiya BajajNo ratings yet

- SPEX Issue 12Document11 pagesSPEX Issue 12SMU Political-Economics Exchange (SPEX)No ratings yet

- Federal DebtDocument14 pagesFederal Debtabhimehta90No ratings yet

- 01 - The Deepening CrisisDocument28 pages01 - The Deepening CrisisCzarina VillarinNo ratings yet

- Determinants of Public DebtDocument28 pagesDeterminants of Public DebtNhi NguyễnNo ratings yet

- Global Debt Monitor - April2020 IIF PDFDocument5 pagesGlobal Debt Monitor - April2020 IIF PDFAndyNo ratings yet

- As of 5 P.M. Thurs. Global Public Debt: $40,660,121,927,289 (U.S.)Document5 pagesAs of 5 P.M. Thurs. Global Public Debt: $40,660,121,927,289 (U.S.)prince marcNo ratings yet

- David Einhorn NYT-Easy Money - Hard TruthsDocument2 pagesDavid Einhorn NYT-Easy Money - Hard TruthstekesburNo ratings yet

- A Reconsideration of Fiscal Policy in The Era of Low Interest RatesDocument51 pagesA Reconsideration of Fiscal Policy in The Era of Low Interest RatesJohnclaude ChamandiNo ratings yet

- Public Debt, Public Investment and Economic GrowthDocument11 pagesPublic Debt, Public Investment and Economic GrowthaabbiilNo ratings yet

- Kose, M Et Al, 2019 Global Waves of Debt, Chapter1Document29 pagesKose, M Et Al, 2019 Global Waves of Debt, Chapter1Gilberto PariotNo ratings yet

- 2012: THE WEAK ECONOMY AND HOW TO DEAL WITH IT TO EMPOWER THE CITIZENSFrom Everand2012: THE WEAK ECONOMY AND HOW TO DEAL WITH IT TO EMPOWER THE CITIZENSNo ratings yet

- CAPITAL GAINS TAX: Analysis of Reform Options For AustraliaDocument101 pagesCAPITAL GAINS TAX: Analysis of Reform Options For AustraliaAlan ReynoldsNo ratings yet

- How I Helped Persuade The Australian Government To Cut The Capital Gains Tax in Half.Document28 pagesHow I Helped Persuade The Australian Government To Cut The Capital Gains Tax in Half.Alan ReynoldsNo ratings yet

- Reynolds 1971 FullDocument5 pagesReynolds 1971 FullAlan ReynoldsNo ratings yet

- Alan Reynolds On Price Controls 1971 CoverDocument1 pageAlan Reynolds On Price Controls 1971 CoverAlan ReynoldsNo ratings yet

- Alan Reynolds, The Politics of Alternative EnergyDocument61 pagesAlan Reynolds, The Politics of Alternative EnergyAlan ReynoldsNo ratings yet

- How To Build A Bifacial Solar Plant (AJM)Document8 pagesHow To Build A Bifacial Solar Plant (AJM)SohaibNo ratings yet

- Industry AnalysisDocument22 pagesIndustry Analysispranita mundraNo ratings yet

- Will Soaring Transportation Costs Reverse Globalization?: Jeff Rubin Chief Economist & Chief StrategistDocument10 pagesWill Soaring Transportation Costs Reverse Globalization?: Jeff Rubin Chief Economist & Chief StrategistDelicaDelloNo ratings yet

- Edible Oils in Egypt AnalysisDocument5 pagesEdible Oils in Egypt AnalysisgemagdyNo ratings yet

- Columbia WHTDocument7 pagesColumbia WHTAnilNo ratings yet

- B) Equity and Policies Towards Income and Wealth RedistributionDocument6 pagesB) Equity and Policies Towards Income and Wealth RedistributionRACSO elimuNo ratings yet

- PDFDocument187 pagesPDFTony AnandaNo ratings yet

- Ec O18Document51 pagesEc O18Maria CabritaNo ratings yet

- Aspire Credit Card StatementDocument2 pagesAspire Credit Card StatementSangam sahuNo ratings yet

- Payment FormDocument4 pagesPayment FormRodel Rivera VelascoNo ratings yet

- NH7211238227994.INDIA HotelierVoucherDocument3 pagesNH7211238227994.INDIA HotelierVoucherInfo KochiNo ratings yet

- Summer Project MarketingDocument66 pagesSummer Project MarketingKhushi PatelNo ratings yet

- IF 07C Special Instruction Form Form - 07 03 January 2022 4Document2 pagesIF 07C Special Instruction Form Form - 07 03 January 2022 4chqaiserNo ratings yet

- List of Property Dealers Registered: Lic - No. Date Name Address of Dealer Location of Bussiness Father/Husband NameDocument253 pagesList of Property Dealers Registered: Lic - No. Date Name Address of Dealer Location of Bussiness Father/Husband NameMAFIA HARYANANo ratings yet

- Economics 20th Edition Mcconnell Test BankDocument7 pagesEconomics 20th Edition Mcconnell Test BankMeghanBradleyocip100% (46)

- RepaymentDocument7 pagesRepaymentdharmendraNo ratings yet

- Chapter 22 OutlineDocument3 pagesChapter 22 OutlineZachary DequillaNo ratings yet

- PhilHealth Claim Form1Document2 pagesPhilHealth Claim Form1Grace Flores Comandante-LimNo ratings yet

- Devaluation of The RupeeDocument7 pagesDevaluation of The RupeeReevu AdhikaryNo ratings yet

- A Report by Shivani SinghDocument8 pagesA Report by Shivani Singh1820 GAURAV MISHRANo ratings yet

- Chapter 1 Social Problems SDGs and Laudato SiDocument38 pagesChapter 1 Social Problems SDGs and Laudato Sisabrina pusitNo ratings yet

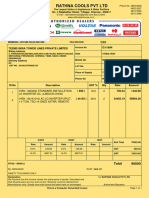

- AC InvoiceDocument1 pageAC Invoicek.rganthNo ratings yet

- 29HC202403102800Document1 page29HC202403102800ramanujamsrinivas576No ratings yet

- MIE1514 Assignment 3 - Q2 CJDocument2 pagesMIE1514 Assignment 3 - Q2 CJJiaNo ratings yet

- ESG Assignment 1Document22 pagesESG Assignment 1Paresh ShrivastavaNo ratings yet

- RBI Circular Import Goods ServicesDocument25 pagesRBI Circular Import Goods Servicesgayanw1978No ratings yet

- Case Study IDocument4 pagesCase Study Iesraa karam0% (1)

- BKM - Worksheet PT - Mil Jan'2021Document26 pagesBKM - Worksheet PT - Mil Jan'2021Dita AiniNo ratings yet

- Ge 3 Contemporary WorldDocument51 pagesGe 3 Contemporary WorldDarioz Basanez Lucero100% (8)