Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Seizure: Soheila Zareifar, Hamid Reza Hosseinzadeh, Nader Cohan

Seizure: Soheila Zareifar, Hamid Reza Hosseinzadeh, Nader Cohan

Uploaded by

Firda PotterOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Seizure: Soheila Zareifar, Hamid Reza Hosseinzadeh, Nader Cohan

Seizure: Soheila Zareifar, Hamid Reza Hosseinzadeh, Nader Cohan

Uploaded by

Firda PotterCopyright:

Available Formats

Seizure 21 (2012) 603605

Contents lists available at SciVerse ScienceDirect

Seizure

journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/yseiz

Association between iron status and febrile seizures in children

Soheila Zareifar *, Hamid Reza Hosseinzadeh, Nader Cohan

Hematology Research Center, Nemazee Hospital, Shiraz University of Medical Sciences, Shiraz, Iran

A R T I C L E I N F O

A B S T R A C T

Article history:

Received 20 September 2011

Received in revised form 16 June 2012

Accepted 18 June 2012

Objectives: The aim of this study was to determine the association between iron status and febrile

seizures in children aged 6 months to 5 years.

Methods: This prospective casecontrol study enrolled 300 children who presented with febrile seizures

(case group) and 200 children who presented with a febrile illness without seizures (control group) from

March 2007 to January 2009. Hemoglobin, mean corpuscular volume and serum ferritin concentration

were compared in the two groups in relation to age, sex and use of iron supplementation.

Results: Patients with febrile seizures were more frequently iron decient as dened by a serum ferritin

level below 20 ng/dl (56.6% vs. 24.8%, P = 0.0001). Mean hemoglobin concentration was 10.8 g/dl in the

control group and 11.7 g/dl in the case group (P < 0.05). The difference between groups in mean

corpuscular volume was not statistically signicant (75.5 vs. 74.4 , P < 0.130).

Conclusion: Low serum ferritin concentration and low iron status may be risk factors for the development

of febrile seizures.

2012 British Epilepsy Association. Published by Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

Keywords:

Iron

Febrile seizure

Ferritin

Children

1. Introduction

Simple febrile seizures (SFSs) are the most common type of

seizure during childhood. The peak incidence is at the age of

approximately 18 months, occurring in 25% of all children.1

Because of their association with later epilepsy, many independent

risk factors (genetic factors, age, gender, fever, type and duration of

seizure, family and developmental history, multiple seizures,

perinatal exposure to antiretroviral drugs, history of maternal

smoking and alcohol consumption during pregnancy) have been

studied as potential predictors of recurrent febrile seizures.25

However, the data available in the literature are inconsistent.69

Iron plays a critical role in the metabolism of several

neurotransmitters, and in low iron status, aldehyde oxidases

and monoamine are reduced. In addition, the expression of

cytochrome C oxidase, a marker of neuronal metabolic activity, is

decreased in iron deciency.10 In developing countries, iron

deciency is one of the most prevalent nutritional problems,11

especially among infants aged between 6 and 24 months.1216 In

developing countries 4666% of all children under 4 years of age

are anemic, with half of the prevalence attributed to irondeciency anemia. Many studies have clearly demonstrated the

effect of iron on development, cognition, behavior and neurophysiology, and especially on brain metabolism, neurotransmitter

function and myelination.17 Iron-deciency anemia is common

* Corresponding author. Tel.: +98 7116473239; fax: +98 7116473239.

E-mail address: zareifars@sums.ac.ir (S. Zareifar).

during the second and third years of life and has been variably

associated with developmental and behavioral impairments,

hence it can inuence motor and cognitive skills.10,11 Because

iron is important for the function of various enzymes and

neurotransmitters in the central nervous system, low serum levels

of ferritin may lower the seizure threshold.18,19

We compared iron status in children with febrile seizures and a

control group in order to determine the relationship between iron

status and febrile seizures in pediatric patients in southern Iran.

2. Patients and methods

The study group consisted of 300 children with a rst febrile

seizure admitted to the pediatric emergency departments of Shiraz

University of Medical Sciences, Shiraz, southern Iran, between

March 2007 and January 2009. Written informed consent was

obtained from the parents of all patients for inclusion in the study,

which was approved by the Shiraz University of Medical Sciences

Ethics Committee. Simple febrile seizures were dened as seizure

occurring between the ages of 6 months and 5 years, associated

with a rectal temperature of at least 38.3 8C or an axillary

temperature of at least 37.8 8C documented either in the

emergency department or in the medical record, <15 min

duration, without evidence of central nervous system infection,

focal neurological signs or history of seizure, and occurring once in

the previous 24 h. The seizure was dened as complex if it lasted

>15 min, occurred more than once in 24 h or had focal features.

Children with developmental delay, denite neurological illness,

or a history of proved iron-deciency anemia, regular blood

1059-1311/$ see front matter 2012 British Epilepsy Association. Published by Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.seizure.2012.06.010

S. Zareifar et al. / Seizure 21 (2012) 603605

604

transfusion or regular therapeutic doses of iron supplements were

excluded. A control group (n = 200) was selected randomly from

children admitted for febrile illnesses such as gastroenteritis, otitis

media or respiratory tract infections without seizure, previous

history of seizure or anticonvulsant therapy. Case and control

groups were comparable for age, gender, normal growth and

development, family history of febrile seizures, temperature at

presentation, white blood cell count and differential, and use of

iron supplementation. Age, sex, underlying illness, frequency and

duration of seizures were recorded for both groups. Because

ferritin is an acute-phase reactant protein in inammatory and

infectious processes, serum ferritin (SF) concentration was

measured by ELISA and double-checked 72 h after the onset of

the febrile illness. Anemia was dened as a decrease in mean

hemoglobin (Hb) level below 2 standard deviations of the normal

values for age, i.e. Hb < 10.5 g/dl for ages 624 months and

<11.5 g/dl for ages 25 years. Hemoglobin, mean corpuscular

volume (MCV), and SF concentration were compared in the case

and control groups.

3. Statistical analysis

The data were analyzed with the SPSS version 15 software

package for Windows (Chicago, IL, USA) by two-sample t-test.

Pearsons chi-squared test was used to calculate the differences in

proportions. Discrete variables are expressed as counts and

percentages. P values < 0.05 were considered signicant.

4. Results

Our results were based on 300 children with SFS (158 boys, 142

girls) and a control group of 200 children (72 boys, 128 girls). Table

1 shows the mean values of Hb, MCV and SF in case and control

groups. For this study we divided the sample into two age

subgroups of 6 months to 2 years (Table 2) and 25 years (Table 3).

The proportion of children with Hb < 10.5 g/dl was higher in both

control subgroups (P = 0.0001, Tables 2 and 3). Serum ferritin

concentration was signicantly lower in both case subgroups

(57.5% vs. 22% and 55.7% vs. 27.6%, P = 0.0001). The differences in

MCV were not signicant in either age subgroup. In children aged

6 months to 2 years (Table 2) and 25 years (Table 3), SF was

signicantly lower (P = 0.0001) in the SFS group.

In both age subgroups, the use of nontherapeutic doses of iron

supplements was more frequent in children with febrile illness

without seizure than in the case group with SFS (Tables 2 and 3).

5. Discussion

This study showed that patients with febrile seizures were

more frequently iron decient as dened by below-normal SF

levels. There is controversy regarding the role of iron status in

febrile convulsions, which are considered a benign seizure

syndrome distinct from epilepsy.1 Previous studies have reported

a relationship between iron-deciency anemia and convulsions in

patients with malaria.19 In addition, iron-deciency anemia can

cause developmental delay and behavioral disturbances early in

life, and correcting anemia early may reverse these processes.2022

Naveed and Billo showed that SF levels were signicantly lower in

children with febrile seizure compared to controls, and suggested

that children with iron deciency are more prone to febrile

seizures.23 Another study found that the incidence of febrile

seizures in patients with thalassemia was much lower than among

children in the general population.24 Thus, iron overload may be a

major factor in the brain metabolism that prevents febrile seizures.

Kobrinsky et al. also suggested that iron-deciency anemia raises

the threshold for febrile seizure,19 whereas Daoud et al. showed

that SF levels were signicantly lower in patients with a rst febrile

seizure than in patients with febrile illness without convulsions.18

Pisacane et al. reported an association between iron-deciency

anemia and febrile convulsions in Neapolitan children.2 In

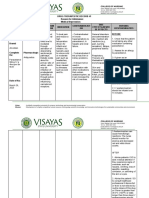

Table 1

Mean age, hemoglobin, mean corpuscular volume and serum ferritin in children with simple febrile seizure (cases) and febrile illness without seizure (controls).

Data

Age (months)

Hb (g/dl)

MCV ()

SF (ng/dl)

Cases (n = 300)

Controls (n = 200)

P value

Mean

SD

Mean

SD

26.4

11.7

74.4

28.7

13.8

1.16

6.95

10.7

25.6

10.8

75.5

32.98

18.3

1.8

7.53

8.6

0.62

0.0001

0.13

0.0001

Table 2

Characteristics of cases and controls at ages 6 months to 2 years.

Characteristic

Hb < 10.5 (g/dl)

MCV < 70 ()

SF < 30 (ng/dl)

Nontherapeutic iron supplement

Cases (n = 139)

Controls (n = 88)

P value

Male (%)

Female (%)

Male (%)

Female (%)

36.1

34.8

51

71

30.4

17.9

64.1

66.7

65.2

34.1

13

87.9

50.7

19

31

86.2

<0.0001

0.15

<0.0001

<0.05

Table 3

Characteristics of cases and controls at ages 25 years.

Characteristic

Hb < 11.5 (g/dl)

MCV < 75 ()

PF < 30 (ng/dl)

Nontherapeutic iron supplement

Cases (n = 151)

Controls (n = 112)

P value

Male (%)

Female (%)

Male (%)

Female (%)

36.7

32.2

50.8

83.1

47.6

45.5

60.6

75.8

44.6

31.9

25.5

93.6

71.7

16.2

29.7

86.5

<0.0001

<0.05

<0.0001

<0.05

S. Zareifar et al. / Seizure 21 (2012) 603605

contrast, Momen and Hakimzadeh reported no relationship

between iron-deciency anemia and rst febrile convulsion in

children younger than 5 years of age in Iran.25 In another study in

Iran, Bidabadi and Mashouf reported that iron-deciency anemia

was less frequent among patients with febrile seizure than in

controls, and found no protective effect of iron deciency against

febrile convulsions.26 Pisacane et al., in their comparative study of

age- and sex-matched children, reported a signicantly higher

rate of iron-deciency anemia, dened on the basis of low serum

iron concentration, among children with febrile seizure than in

the control group.2 In children younger than 2 years of age, 30% of

those with febrile seizures had anemia compared to 14% in the

control group. However, SF levels were not measured in that

study.

In the present study the difference in MCV between the case

and control group overall and between children aged 6 months

to 2 years with and without SFS was not signicant, but it was

signicant in the 2-to-5 year old age group. Kobrinsky et al. also

reported that patients with febrile seizures were less frequently

iron decient as dened by elevated free erythrocyte protoporphyrin, but in their study, SF levels were not measured.19 Of the

indices of body iron status measured in the present study, SF

level was the only value that was signicantly lower in children

with SFS than in the control group a nding also reported by

Daoud et al.18 Although fever was present in all of our patients

in both groups, SF levels were measured 72 h after the onset of

the febrile illness. None of the patients in either group were

being treated for iron-deciency anemia on presentation, but

signicant numbers of patients in both groups sometimes used

non-therapeutic doses of iron supplements. We did not evaluate

the response to iron therapy in children in whom febrile

seizures recurred. Our results suggest that low SF levels may

play a role in febrile seizures.

6. Limitations

The main limitation of this study was the potential confounding

effect of ferritin as an acute-phase reactant agent, which can

interfere with the inuence of iron status on febrile seizures. This

limitation could be overcome by predicting the time when ferritin

level returned to its baseline value after the acute-phase reaction.

7. Conclusion

Low body iron status may decrease the threshold of seizure and

be a risk factor for the development of febrile seizures.

Conict of interest

None.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by Shiraz University of Medical

Sciences research committee. We thank Shirin Parand and K.

605

Shashok (author AID in the Eastern Mediterranean) for improving

the use of English in the manuscript.

References

1. Berg AT. Febrile seizures and epilepsy: the contribution of epidemiology.

Paediatric and Perinatal Epidemiology 1992;6:14552.

2. Pisacane A, Sansone R, Impagliazzo N, Coppola A, Rolando P, DApuzzo A, et al.

Iron deciency anemia and febrile convulsions: casecontrol study in children

under 2 years. British Medical Journal 1996;313:343.

3. Huang CC, Wang ST, Chang YC, Huang MC, Chi YC, Tsai JJ. Risk factors for a rst

febrile convulsion in children: a population study in southern Taiwan. Epilepsia

1999;40(6):71925.

4. Landreau-Mascaro A, Barret B, Mayaux MJ, Tardieu M, Blanche S. Risk of early

febrile seizure with perinatal exposure to nucleoside analogues. Lancet

2002;359(9306):5834.

5. Berg AT, Shinnar S, Shapiro ED, Salomon ME, Crain EF, Hauser WA. Risk factors for a

rst febrile seizure: a matched casecontrol study. Epilepsia 1995;36(4):33441.

6. Shinnar S. Febrile seizures. In: Swaiman KF, Ashwal S, Ferriero DM, editors.

Pediatric neurology principles and practice. 4th ed. City: Mosby Elsevier; 2006. p.

107989.

7. Hampers LC, Thompson DA, Bajaj L, Tseng BS, Rudolph JR. Febrile seizure:

measuring adherence to AAP guidelines among community ED physicians.

Pediatric Emergency Care 2006;22(7):4659.

8. Annegers JF, Blakely SA, Hauser WA. Recurrence of febrile convulsions in a

population-based cohort. Epilepsy Research 1990;66:1009.

9. Berg AT. The epidemiology of seizures and epilepsy in children. In: Shinnar S,

Amir N, Branski D, editors. Childhood seizures. Basel, Switzerland: Karger; 1995.

10. DeUngria M, Rao R, Wobken JD, Luciana M, Nelson CA, Georgieff MK. Perinatal

iron deciency decreases cytochrome c oxidase (CytOx) activity in selected

regions of neonatal rat brain. Pediatric Research 2000;48:16976.

11. Beard JL, Erikson KM, Jones BC. Neurobehavioral analysis of developmental iron

deciency in rats. Behavioural Brain Research 2002;134(12):51724.

12. Angulo-Kinzler RM, Peirano P, Lin E, Algarin C, Garrido M, Lozoff B. Twenty fourhour motor activity in human infants with and without iron deciency anemia.

Early Human Development 2002;70(12):85101.

13. DeMaeyer E, Adiels-Tegman M. The prevalence of anemia in the world. World

Health Statistics Quarterly 1985;38:30216.

14. Florentino RF, Guirriec RM. Prevalence of nutritional anemia in infancy and

childhood with emphasis on developing countries. In: Stekel A, editor. Iron

nutrition in infancy and childhood. New York: Raven Press; 1984. p. 6174.

15. Freire W. Strategies of the Pan American Health OrganizationWorld Health

Organization for the control of iron deciency in Latin America. Nutrition

Reviews 1997;55:1838.

16. Stoltzfus R. Dening iron-deciency anemia in public health terms: a time for

reection. Journal of Nutrition 2001;131(2S-2):565S7S.

17. Madan N, Rusia U, Sikka M, Sharma S, Shankar N. Developmental and neurophysiologic decits in iron deciency in children. Indian Journal of Pediatrics

2011;78(1):5864.

18. Daoud AS, Batieha A, Abu-Ekteish F, Gharaibeh N, Ajlouni S, Hijazi S. Iron status:

a possible risk factor for the rst febrile seizure. Epilepsia 2002;43(7):7403.

19. Kobrinsky NL, Yager JY, Cheang MS, Yatscoff RW, Tenenbein M. Does iron

deciency raise the seizure threshold? Journal of Child Neurology 1995;10(March

(2)):1059.

20. Parks YA, Wharton BA. Iron deciency and the brain. Acta Paediatrica Scandinavica 1989;55(suppl. 361):717.

21. Lozoff B, Beard J, Connor J, Barbara F, Georgieff M, Schallert T. Long-lasting

neural and behavioral effects of iron deciency in infancy. Nutrition Reviews

2006;64(5 Pt 2):S3443 [discussion S72-91].

22. Idjradinata P, Pollitt E. Reversal of developmental delays in iron decient

anemic infants treated with iron. Lancet 1993;341:14.

23. Naveed-Ur-Rehman. Billo AG. Association between iron deciency anemia and

febrile seizures. Journal of College of Physicians and Surgeons Pakistan

2005;15(6):33840.

24. Auvichayapat P, Auvichayapat N, Jedsrisuparp A, Thinkhamrop B, Sriroj S,

Piyakulmala T<ET AL>. Incidence of febrile seizures in thalassemic patients.

Journal of the Medical Association of Thailand 2004;87(8):9703.

25. Momen AA, Hakimzadeh M. Casecontrol study of the relationship between

anemia and febrile convulsion in children between 9 months and 5 years of age.

Scientic Medical Journal of Ahwaz University of Medical Sciences 2003;1(4):504.

26. Bidabadi E, Mashouf M. Association between iron deciency anemia and rst

febrile convulsion: a casecontrol study. Seizure 2009;18(June (5)):34751.

You might also like

- Nursing Care Plan FeverDocument9 pagesNursing Care Plan FeverVincent Quitoriano85% (48)

- NCP FeverDocument3 pagesNCP Feversinister1785% (48)

- Nursing Care PlansDocument48 pagesNursing Care PlansJuliantiMamangkey86% (7)

- NCPDocument13 pagesNCPLee Da HaeNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S1059131111003268 MainDocument4 pages1 s2.0 S1059131111003268 MainAbdul Ghaffar AbdullahNo ratings yet

- The Relationship Between Iron Deficiency and Febrile Seizure in A Group of Children in Al-Zahraa Teaching Hospital in Al-Najaf GovernorateDocument12 pagesThe Relationship Between Iron Deficiency and Febrile Seizure in A Group of Children in Al-Zahraa Teaching Hospital in Al-Najaf GovernorateCentral Asian StudiesNo ratings yet

- Status Gizi KD Case ControlDocument4 pagesStatus Gizi KD Case Controlwimakrifah istiqomahNo ratings yet

- 6 PBDocument7 pages6 PBLinda AyuNo ratings yet

- Jurnal Reading Iron Deficiency Fakotor Resiko Kejang DemamDocument9 pagesJurnal Reading Iron Deficiency Fakotor Resiko Kejang Demamrizqiahmad33No ratings yet

- Jurnal Besi2Document3 pagesJurnal Besi2Firda PotterNo ratings yet

- Hubungan Anemsia Defisiensi Besi Dengan Kejang Demam Pada Anak BalitaDocument10 pagesHubungan Anemsia Defisiensi Besi Dengan Kejang Demam Pada Anak BalitaAulia ChoirunnisaNo ratings yet

- Kasus Neuro (Saraf)Document10 pagesKasus Neuro (Saraf)ardyan tejaNo ratings yet

- Contoh Majalah PIDocument6 pagesContoh Majalah PIajescoolNo ratings yet

- Iron Deficiency Anemia Among Preschooi Children (2-5) Years in Gaza StripDocument17 pagesIron Deficiency Anemia Among Preschooi Children (2-5) Years in Gaza StripMohammedAAl-HaddadAbo-alaaNo ratings yet

- Psychomotor DevelopmentDocument5 pagesPsychomotor DevelopmentAde RezekiNo ratings yet

- Anemia InsomniaDocument6 pagesAnemia InsomniaBalqis SafariNo ratings yet

- Jurnal AnemiaDocument6 pagesJurnal AnemiamarselyagNo ratings yet

- Prevalence and Causes of Iron Deficiency Anemias in Infants Aged 9 To 12 Months in EstoniaDocument6 pagesPrevalence and Causes of Iron Deficiency Anemias in Infants Aged 9 To 12 Months in EstoniamuarifNo ratings yet

- Prevalence and Risk Factors of Anemia in Under Five-Year-Old Children in Children's HospitalDocument4 pagesPrevalence and Risk Factors of Anemia in Under Five-Year-Old Children in Children's Hospitalindahsarizahab 28No ratings yet

- Endocrine Abnormalities in Children With Beta Thalassaemia MajorDocument6 pagesEndocrine Abnormalities in Children With Beta Thalassaemia MajorKrisbiyantoroAriesNo ratings yet

- Clinical Pediatrics: Impact of Vegetarian Diet On Serum Immunoglobulin Levels in ChildrenDocument7 pagesClinical Pediatrics: Impact of Vegetarian Diet On Serum Immunoglobulin Levels in ChildrenAldy RinaldiNo ratings yet

- Selenium and Leptin Levels in Febrile Seizure: A Case-Control Study in ChildrenDocument6 pagesSelenium and Leptin Levels in Febrile Seizure: A Case-Control Study in ChildrenDyah Gaby KesumaNo ratings yet

- Effectiveness of Iron Therapy On Breath Holding Spells in The ChildrenDocument7 pagesEffectiveness of Iron Therapy On Breath Holding Spells in The ChildrenLetícia SpinaNo ratings yet

- PDF TJP 2149Document12 pagesPDF TJP 2149Imam SabarudinNo ratings yet

- Original Article: Comparative Evaluation of Iron Deficiency Among Obese and Non-Obese ChildrenDocument7 pagesOriginal Article: Comparative Evaluation of Iron Deficiency Among Obese and Non-Obese ChildrenKurnia pralisaNo ratings yet

- TMP AE98Document5 pagesTMP AE98FrontiersNo ratings yet

- Profile of Severe Nutritional Anemia in Children at A Tertiary Care Hospital, South IndiaDocument8 pagesProfile of Severe Nutritional Anemia in Children at A Tertiary Care Hospital, South IndiaDr. Krishna N. SharmaNo ratings yet

- Original Article: AbstractDocument3 pagesOriginal Article: AbstractSeptiani HasibuanNo ratings yet

- 2 Haematological Profile in Children With Protein PDFDocument7 pages2 Haematological Profile in Children With Protein PDFAma BeluNo ratings yet

- RA Iron Deficiency AnemiaDocument6 pagesRA Iron Deficiency Anemiainggrit06No ratings yet

- Impairment of Bone Health in Pediatric Patients With Hemolytic AnemiaDocument7 pagesImpairment of Bone Health in Pediatric Patients With Hemolytic AnemiaMarifer EstradaNo ratings yet

- Anemia and NutrientDocument4 pagesAnemia and NutrientrosaliaNo ratings yet

- Estimating The Prevalence of Iron Deficiency in The First TwoDocument8 pagesEstimating The Prevalence of Iron Deficiency in The First TwoJavier LunaNo ratings yet

- Association Between Helicobacter Pylori Infection and Iron DeficiencyDocument4 pagesAssociation Between Helicobacter Pylori Infection and Iron Deficiencydaiana.diazNo ratings yet

- Iron Deficiency Anaemia in Reproductive Age Women Attending Obstetrics and Gynecology Outpatient of University Health Centre in Al-Ahsa, Saudi ArabiaDocument4 pagesIron Deficiency Anaemia in Reproductive Age Women Attending Obstetrics and Gynecology Outpatient of University Health Centre in Al-Ahsa, Saudi ArabiaDara Mayang SariNo ratings yet

- Iron Def IJPDocument5 pagesIron Def IJPPrahbhjot MalhiNo ratings yet

- The Relationship Between Depression and Serum Ferritin Level - Shariatpanaahi 2007Document4 pagesThe Relationship Between Depression and Serum Ferritin Level - Shariatpanaahi 2007Julio JuarezNo ratings yet

- HemaDocument10 pagesHemadrkhengkiNo ratings yet

- Iron Deficiency in Young Children: A Risk Marker For Early Childhood CariesDocument6 pagesIron Deficiency in Young Children: A Risk Marker For Early Childhood Carieswahyudi_donnyNo ratings yet

- 2023 Anemia and Associated Factors Among Internally Displaced Children at Debark...Document21 pages2023 Anemia and Associated Factors Among Internally Displaced Children at Debark...Olga CîrsteaNo ratings yet

- Determinants of Nutritional Anaemia in Children Less Than Five Years AgeDocument6 pagesDeterminants of Nutritional Anaemia in Children Less Than Five Years AgeBaiiqDelaYulianingtyasNo ratings yet

- Iron DefDocument5 pagesIron DefchristieNo ratings yet

- Association of Elevated Serum Ferritin Concentration With Insulin Resistance and Impaired Glucose Metabolism in Korean Men and WomenDocument7 pagesAssociation of Elevated Serum Ferritin Concentration With Insulin Resistance and Impaired Glucose Metabolism in Korean Men and WomenMakbule ERÇAKIRNo ratings yet

- EJMCM - Volume 7 - Issue 11 - Pages 4739-4745Document7 pagesEJMCM - Volume 7 - Issue 11 - Pages 4739-4745Myo KoNo ratings yet

- ExcelenteDocument6 pagesExcelenteRicardo ColomaNo ratings yet

- Common Cold JournalDocument5 pagesCommon Cold JournalJuwita PratiwiNo ratings yet

- Associations Between Environmental Heavy Metal Exposure and Childhood Asthma: A Population-Based StudyDocument11 pagesAssociations Between Environmental Heavy Metal Exposure and Childhood Asthma: A Population-Based StudyLeidy CarolinaNo ratings yet

- 3 AnemiainPregnancyDocument6 pages3 AnemiainPregnancyGabriela RablNo ratings yet

- Anemi 2Document7 pagesAnemi 2inggrit thalasaviaNo ratings yet

- Am J Clin Nutr 2005 Schneider 1269 75Document7 pagesAm J Clin Nutr 2005 Schneider 1269 75Jony KechapNo ratings yet

- Risk Factor 3Document8 pagesRisk Factor 3ayham luNo ratings yet

- Stunting Dan Stress Oksidatif - Aly 2018Document6 pagesStunting Dan Stress Oksidatif - Aly 2018Emmy KwonNo ratings yet

- Journal Trace Elements in MedicineDocument10 pagesJournal Trace Elements in MedicineOmar ReynosoNo ratings yet

- Iron Deficiency, Cognitive Functions, and Neurobehavioral Disorders in ChildrenDocument10 pagesIron Deficiency, Cognitive Functions, and Neurobehavioral Disorders in ChildrenWahyu RhomadonNo ratings yet

- Serum Ferritin and Amphetamine Response in Youth With Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity DisorderDocument8 pagesSerum Ferritin and Amphetamine Response in Youth With Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity DisorderFahmi FachruddinsyahNo ratings yet

- Literature Review On Prevalence of Anemia in PregnancyDocument4 pagesLiterature Review On Prevalence of Anemia in Pregnancyc5pdd0qgNo ratings yet

- Diagnosis and Prevention of Iron Def Anemia in 0-3yoDocument13 pagesDiagnosis and Prevention of Iron Def Anemia in 0-3yorinNo ratings yet

- Diarrhea Dan AnemiaDocument4 pagesDiarrhea Dan AnemiaUnyar LeresatiNo ratings yet

- Anemia Among Adolescents: ArticleDocument7 pagesAnemia Among Adolescents: ArticleEliya eliyaNo ratings yet

- 5-Effect of Low-Dose Ferrous Sulfate Vs Iron Polysaccharide Complex On Hemoglobin Concentration in Young Children With Nutritional Iron-Deficiency AnemiaDocument8 pages5-Effect of Low-Dose Ferrous Sulfate Vs Iron Polysaccharide Complex On Hemoglobin Concentration in Young Children With Nutritional Iron-Deficiency AnemiaMundo Tan PareiraNo ratings yet

- Anemia As Risk Factor For PneumoniaDocument12 pagesAnemia As Risk Factor For PneumoniaEndy Widya PutrantoNo ratings yet

- Research ArticleDocument7 pagesResearch ArticleauliyaNo ratings yet

- Iron Supplementation Improves Iron Status and Reduces Morbidity in Children With or Without Upper Respiratory Tract Infections: A Randomized Controlled Study in Colombo, Sri Lanka1-3Document15 pagesIron Supplementation Improves Iron Status and Reduces Morbidity in Children With or Without Upper Respiratory Tract Infections: A Randomized Controlled Study in Colombo, Sri Lanka1-3nurkasihNo ratings yet

- Complementary and Alternative Medical Lab Testing Part 16: HematologyFrom EverandComplementary and Alternative Medical Lab Testing Part 16: HematologyNo ratings yet

- Tabel 1.16 Hasil Penemuan Penderita Program P2 ISPA Poli MTBS Rawat Inap Cempaka 2014 Periode Januari-Desember 2014Document4 pagesTabel 1.16 Hasil Penemuan Penderita Program P2 ISPA Poli MTBS Rawat Inap Cempaka 2014 Periode Januari-Desember 2014Firda PotterNo ratings yet

- Management For Labiopalatognatoskizis PatientDocument1 pageManagement For Labiopalatognatoskizis PatientFirda PotterNo ratings yet

- 2009 Article 957Document8 pages2009 Article 957Firda PotterNo ratings yet

- Jurnal Besi2Document3 pagesJurnal Besi2Firda PotterNo ratings yet

- DAFTAR PUSTAKA AcccccDocument2 pagesDAFTAR PUSTAKA AcccccFirda PotterNo ratings yet

- Immune Reconstitution Inflammatory Syndrome and Cerebral ToxoplasmosisDocument2 pagesImmune Reconstitution Inflammatory Syndrome and Cerebral ToxoplasmosisFirda PotterNo ratings yet

- BR J Ophthalmol 2004 Stanford 444 5Document4 pagesBR J Ophthalmol 2004 Stanford 444 5Firda PotterNo ratings yet

- 976 FullDocument7 pages976 FullFirda PotterNo ratings yet

- 2008 Article 25Document8 pages2008 Article 25Firda PotterNo ratings yet

- Ijeb 48 (7) 642-650Document0 pagesIjeb 48 (7) 642-650Firda PotterNo ratings yet

- 3.CI - AppendixDocument63 pages3.CI - AppendixFirda PotterNo ratings yet

- Nursing Care PlanDocument3 pagesNursing Care Planagentlara28No ratings yet

- Dmt316 Manual UkDocument12 pagesDmt316 Manual UkCarlos MinayaNo ratings yet

- Protokol SarcomaDocument4 pagesProtokol SarcomaHep PutNo ratings yet

- Drug Study ParacetamolDocument1 pageDrug Study ParacetamolAbigail Basco100% (2)

- Referral Letter - MeningitisDocument3 pagesReferral Letter - MeningitisChristafar RajNo ratings yet

- Homeostasis, Stress and Adaptation - Ppt2aDocument154 pagesHomeostasis, Stress and Adaptation - Ppt2aV_RN100% (2)

- Natural Cancer Remedies That WorkDocument48 pagesNatural Cancer Remedies That WorkAlessio Anam100% (2)

- Effectiveness of Tepid Sponge Compresses and Plaster Compresses On Children'S Fever Temperature TyphoidDocument7 pagesEffectiveness of Tepid Sponge Compresses and Plaster Compresses On Children'S Fever Temperature TyphoidAndri YansyahNo ratings yet

- JD Drug-1-2Document2 pagesJD Drug-1-2RON PEARL ANGELIE CADORNANo ratings yet

- Science Model School: Class: 4 Subject Syllabus Scheme of Papers MarksDocument9 pagesScience Model School: Class: 4 Subject Syllabus Scheme of Papers MarksBest CampusNo ratings yet

- Benign Febrile Convulsions Nursing Care PlansDocument10 pagesBenign Febrile Convulsions Nursing Care PlansMurugesan100% (1)

- Aconitum NapellusDocument18 pagesAconitum Napelluskattarsys1No ratings yet

- How 20to 20perform 20a 20physical 20exam 20in 20your 20horseDocument50 pagesHow 20to 20perform 20a 20physical 20exam 20in 20your 20horseThamil ArasanNo ratings yet

- JP XII Organic Chemistry (23) - 1 PDFDocument7 pagesJP XII Organic Chemistry (23) - 1 PDFAshish RanjanNo ratings yet

- Fever of Unknown OriginDocument26 pagesFever of Unknown OriginFiona Yona Sitali100% (1)

- Physio ThermoregulationDocument9 pagesPhysio ThermoregulationStd DlshsiNo ratings yet

- Standard Treatment ProtocolsDocument663 pagesStandard Treatment Protocolsdrvins1No ratings yet

- End-Stage Renal DiseaseDocument3 pagesEnd-Stage Renal DiseaseAkira Pongchad B100% (1)

- Temperature, Pulse Rate and Inspiration RatesDocument1 pageTemperature, Pulse Rate and Inspiration RatesmvladysemaNo ratings yet

- Engleza Schita-Plan Ingrijire SpecificDocument4 pagesEngleza Schita-Plan Ingrijire SpecificBenterez Ionela BiancaNo ratings yet

- Fever: Clinical DescriptionDocument6 pagesFever: Clinical DescriptionNama ManaNo ratings yet

- Fever Without Source: Dr. Tiroumourougane Serane. VDocument29 pagesFever Without Source: Dr. Tiroumourougane Serane. VTirouNo ratings yet

- IAH AC Introduction To HomotoxicologyDocument60 pagesIAH AC Introduction To HomotoxicologywurtukukNo ratings yet

- Daftar PustakaDocument3 pagesDaftar Pustakahendri najibNo ratings yet

- Nursing Care PlanDocument8 pagesNursing Care Planalexander abasNo ratings yet

- Non Specific HostDocument46 pagesNon Specific HostAdrian BautistaNo ratings yet