Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Pattern of Ocular Injuries in Owo, Nigeria: Original Article

Pattern of Ocular Injuries in Owo, Nigeria: Original Article

Uploaded by

paulpiensaOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Pattern of Ocular Injuries in Owo, Nigeria: Original Article

Pattern of Ocular Injuries in Owo, Nigeria: Original Article

Uploaded by

paulpiensaCopyright:

Available Formats

Original Article

Pattern of Ocular Injuries in Owo, Nigeria

Charles Oluwole Omolase1, FWACS, FMCOphth; Ericson Oluseyi Omolade1, MBBS

Olakunle Tolulope Ogunleye1, MBBS; Bukola Olateju Omolase2, MBBS

Chidi Oliver Ihemedu1, MBBS; Olumuyiwa Adekunle Adeosun1, MBBS

1

Department of Ophthalmology, Federal Medical Center, Owo, Ondo State, Nigeria

2

Department of Radiology, Federal Medical Center, Owo, Ondo State, Nigeria

Purpose: To determine the pattern of ocular injuries in patients presenting to the

eye clinic and the accident and emergency department of Federal Medical Center,

Owo, Ondo State, Nigeria.

Methods: This prospective study was conducted between January and December 2009.

Federal Medical Center, Owo is the only tertiary hospital in Ondo State, Nigeria.

The eye center located at this medical center was the only eye care facility in the

community at the time of this study. All patients were interviewed with the aid of an

interviewer-administered questionnaire and underwent a detailed ocular examination.

Results: Of 132 patients included in the study, most (84.1%) sustained blunt eye

injury while (12.1%) had penetrating eye injury. A considerable proportion of patients

(37.9%) presented within 24 hours of injury. Vegetative materials were the most

common (42.4%) offending agent, a minority of patients (22%) was admitted and

none of the patients had used eye protection at the time of injury.

Conclusion: In the current series, blunt eye injury was the most common type of

ocular trauma. The community should be educated and informed about the importance

of preventive measures including protective eye devices during high risk activities.

Patients should be encouraged to present early following ocular injury.

Keywords: Eye Injuries, Pattern; Vegetative Matter; Nigeria

J Ophthalmic Vis Res 2011; 6 (2): 114-118.

Correspondence to: Charles Oluwole Omolase, FWACS, FMCOphth. Consultant Ophthalmologist, Department

of Ophthalmology, Federal Medical Centre, P.M.B 1053, Owo, Ondo State, Nigeria; Tel: +23408033788860;

e-mail: omolash2000@yahoo.com

Received: May 27, 2010

Accepted: March 9, 2011

INTRODUCTION

Trauma is an important cause of ocular

morbidity. The pattern of ocular injuries tends

to vary from one location to another and is

affected by the activities of residents in a

particular location.1 Many eye injuries are related

to particular occupations and certain cultures. 2

Some individuals by virtue of their job are

prone to ocular injuries and certain activities

of daily living increase the risk of eye trauma

due to exposure to hazards.3 Despite the fact

that the eyes represent only 0.27% of the total

114

body surface area and 4% of the facial area, they

are the third most common organ affected by

injuries after the hands and feet.4 Ocular trauma

is an avoidable cause of blindness and visual

impairment. Ocular trauma may be caused by

various objects used in different settings. 5 Male

subjects are at higher risk of ocular trauma. 6

Even though ocular trauma has been described

as a neglected issue,7 it was highlighted as a

major cause of visual morbidity more recently.8

Worldwide there are approximately 1.6

million people blind from eye injuries, 2.3

million bilaterally visually impaired and 19

JOURNAL OF OPHTHALMIC AND VISION RESEARCH 2011; Vol. 6, No. 2

Ocular Injuries in Nigeria; Omolase et al

million with unilateral visual loss; these facts

make ocular trauma the most common cause

of unilateral blindness. 9 The age distribution

for serious ocular trauma is bimodal with the

maximum incidence in young adults and a

second peak in the elderly. 10,11 Studies have

shown that approximately one half of patients

who present to an eye casualty department are

cases of ocular trauma.12,13 Direct and indirect

costs of ocular trauma are known to run into

millions of dollars annually. 14 Ocular trauma

occurs frequently in developing countries and

constitutes a major health problem. 15 Even

though developing countries carry the largest

burden of ocular trauma, they are the least able

to afford the costs.16,17 Recognition of the public

health importance of ocular trauma has sparked

growing interest in studies on eye injuries.18 The

execution of this study became imperative in

view of an increasing number of ocular trauma

at the only eye center in the community. We

designed this study to determine the pattern

of ocular injuries in patients presenting to the

eye clinic and the accident and emergency

department of Federal Medical Center, Owo,

Ondo State, Nigeria.

METHODS

This prospective study was performed at the

eye clinic and the accident and emergency

department of Federal Medical Center, Owo,

Ondo State, Nigeria between January and

December 2009. The hospital was the only

tertiary medical center in Ondo State at the

time of the study. The eye center is patronized

by patients from Ondo State, Nigeria and some

other neighboring states.

The patients either presented directly to the

hospital or were referred from other public or

private hospitals. Approval was obtained from

the Ethical Review Committee of the hospital

prior to commencement of this study. Informed

consent was obtained from each participant.

All consenting patients with varying degrees of

ocular injuries were enrolled in this study. The

respondents were interviewed with the aid of

semi-structured questionnaire by the authors.

All patients underwent a comprehensive ocular

examination including visual acuity (using

Snellen chart), penlight, slit lamp biomicroscopy

and direct ophthalmoscopy. Data were analyzed

using SPSS 15.0.1 statistical software package

(SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Chi-square test

was employed with statistical significance set

at 0.05.

RESULTS

One hundred and thirty-two patients including

102 male (77.3%) and 30 female (22.7%) subjects

1 to 70 years of age participated in the study.

Ethnicity of the patients was Yorubas in 68.2%,

Ibos in 7.6% and Hausas in 3%. The majority

of the patients (82.6%) were Christian and the

remaining (17.4%) were Muslim. Few patients

(13.3%) had no formal education, 53 (40.2%)

had primary education, 33 (25%) had secondary

education, and 28 (21.2%) had tertiary education.

Most patients (51.5%) were single, 47.7% were

married and one subject (0.8%) was widowed.

The occupation of the patients is detailed in Table

1, most of the patients (36.4%) were students.

The right eye was involved in 60 (45.5%)

subjects, the left eye in 59 (44.7%) cases and the

injury was bilateral in 13 (9.9%) cases. Injury

occurred at home in 40 individuals (30.3%), on

the road in 37 (28%), at school in 28 (21.2%), at

work in 11 (8.3%), during a party in 8 (6.1%),

on a farm in 7 (5.3%) and in church in 1 (0.8%).

Age and sex did not affect the location at which

injury was sustained (P=0.698 and 0.072,

respectively), but occupation was significantly

associated with the place of injury (P<0.001).

Most injuries (84.1%) were blunt, 6 (12.1%)

were due to penetrating trauma, 2 (1.5%) eyes

sustained perforating injury and 3 (2.3%)

were affected by chemical burns. Age, sex

and occupation did not significantly affect

Table 1. Patients occupation

Occupation

Schooling

Farming

Artisan

Trading

Civil Servant

Unemployed

Total

Frequency

48

24

24

17

16

3

132

JOURNAL OF OPHTHALMIC AND VISION RESEARCH 2011; Vol. 6, No. 2

Percentage

36.4

18.2

18.2

12.9

12.1

2.3

100

115

Ocular Injuries in Nigeria; Omolase et al

the type of injury (P=0.396, 0.481 and 0.946,

respectively).

The offending agents are summarized in

Table 2, 42.4% were vegetative materials. Age

and sex were not correlated with the type of

the agent (P=0.976 and 0.528, respectively),

however occupation was significantly associated

with the causal agent (P=0.016).

A considerable proportion of patients

(37.9%) presented within 24 hours, 8.3% after

48 hours, 6.8% after 72 hours, 17.4% between

3 and 7 days, and 29.5% after one week. The

anatomical site of injury and level of education

significantly affected the time of presentation

(P=0.007 and 0.002, respectively) but age, sex

and occupation did not (P=0.334, 0.818 and

0.287, respectively). The distance travelled by

the patients to the eye center was less than

20km in 61.4%, 20-50 km in 21.2%, 50-100km

in 12.9% and more than 100km in 4.5%. This

variable however did not significantly affect

the time of presentation (P=0.7).

Only 32 (24.2%) patients had occupational

eye injury, no subject used protective eyewear

at the time of injury. Only 29 (22%) cases were

admitted. Most patients (51.5%) sought some

form of treatment prior to presentation: 31

patients (45.6%) self administered medication,

5 (7.4%) received traditional treatment and

the remaining 1 (1.5%) used a combination of

treatments.

As detailed in Table 3, the most common

site of injury (43.9%) was the cornea. Age and

sex did not significantly affect the anatomical

site of injury (P=0.573 and 0.302, respectively)

while occupation did (P=0.027). Few patients

(21.2%) had sustained injury to other parts of

the face.

Table 2. Offending agents

Metallic object

Finger, elbow, fist

Insect

Stone

Glass

Bullet

Chemical

Ball

Total

116

Frequency

28

21

11

8

3

2

2

1

132

Percentage

21.2

15.9

8.3

6.1

2.3

1.5

1.5

0.8

100

Table 3. Anatomical site of eye injury

Lid

Conjunctiva

Cornea

Iris

Lens

Anterior/posterior segment

Cornea and lens

Total

Frequency

27

16

58

15

6

5

5

132

Percentage

20.5

12.1

43.9

11.4

4.5

3.8

3.8

100

Table 4. Visual acuity at presentation and after treatment

Visual acuity

6/5-6/18

6/18-6/60

3/60-6/60

<3/60

Total

Frequency (%)

At presentation

After treatment

67 (50.8)

102 (77.3)

16 (12.1)

6 (4.5)

6 (4.5)

1 (0.8)

43 (32.6)

23 (17.4)

132 (100)

132 (100)

The majority of patients (95.5%) had good

vision prior to the injury. Table 4 summarizes

visual acuities of the patients at presentation

and after treatment. Patient age was significantly

associated with visual outcomes (P=0.019),

however sex and occupation were not (P=0.925

and 0.169, respectively). Prognosis for restoration

of vision was good in most patients (62.9%),

fair in 21.2%, and poor in 15.9%.

DISCUSSION

The predominance of Yorubas and Christians

in our study is not surprising in view of

their predominance in the community. There

was a preponderance of male subjects in our

study which is in accordance with some other

reports. 3,19-21 The predominance of ocular

injuries in male subjects may be related to their

aggressive and adventure seeking behavior. As

reported by some other studies,3,12 most of our

patients belonged to a young and active age

group. This finding is understandable as such

people are likely to engage in risky behaviours

and activities which may predispose to ocular

injuries.

The particular function of the eye has

mandated an exposed location which increases

the possibility of injury.22 The type and extent of

damage sustained by the eye depends on both

JOURNAL OF OPHTHALMIC AND VISION RESEARCH 2011; Vol. 6, No. 2

Ocular Injuries in Nigeria; Omolase et al

the mechanism and force of injury. Laterality

in ocular injuries also tends to vary. There was

a slight predominance of injury to the right

eye (45.5%) in this study which is similar to

a report by Mallika et al 21 in Malaysia. This

predominance was higher (58.5%) in a study

by Okoye3 in Enugu, Nigeria. The reason may

be the fact that most people are right handed.

Almost one third of our patients sustained

injury at home. This finding is similar to the

study by Mallika et al.21 Most of our respondents

had blunt trauma which is different from the

report by Okoye, 3 stating a preponderance

of penetrating trauma. Another study has

reported changing patterns of eye injuries in

Nigeria over the past decades during which a

preponderance of war-related injuries in the

early 70s was replaced by home and school

related injuries as well as industrial trauma.

Furthermore with the rising incidence of

armed robbery and civilian-armed combats in

Nigeria, gun shot injuries are becoming more

common.23 Our study included only two cases

of gun shot eye injuries. This finding may be

attributed to the fact that the study population

and neighboring communities enjoyed peaceful

co-existence at the time of the study.

Remarkably, a significant proportion

of our patients presented to the eye clinic

within 24 hours of eye injury which may have

contributed to the favorable outcome in most

of them. Proximity to the eye center may have

contributed to early presentation. Awareness

of the services offered at our eye center is also

likely to have prompted early presentation.

The importance of increasing awareness about

existing eye facilities in the populace cannot

be overemphasized as this is likely to promote

the utilization of such health facilities. Our

findings are somehow in contrast to those

reported by Babar et al24 in Pakistan; over 60%

of their patients presented one week after eye

injury. Late presentation following eye injuries

has also been reported in other studies.25-27 A

study by Qureshi 28 reported that the farther

the victims lived from an eye care facility, the

later they presented after injury. The findings

of the latter report are at variance with the

current study because the distance travelled

by our patients did not significantly affect the

time of presentation.

It is disturbing that none of our respondents

utilized protective devices at the time of

injury. This finding underscores the need for

educating people regarding the use of protective

eyewear which may significantly decrease the

magnitude of visual loss due to trauma. The

impact of ocular trauma in terms of medical

care, loss of income and cost of rehabilitation

services clearly highlights the importance of

preventive strategies.19

In summary there was a preponderance of

eye injuries among male subjects in our study.

Most patients sustained blunt eye injury and

only few of them required admission. A sizeable

proportion of patients presented within 24 hours

after injury. Occupation and the anatomical

site of injury significantly affected the time

of presentation. Some respondents sustained

ocular injury in their school environment. None

of the patients used protective eyewear at the

time of injury. The age of patients significantly

affected visual outcomes. We reccomend mass

education to encourage early presentation

following eye injury and believe that school

authorities should regulate recreational activities

in school and prevent injuries to the eye and

other parts of the body.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the respondents for accepting

to participate in this study. Support by the

Management of Federal Medical Center, Owo,

Ondo State, Nigeria is hereby acknowledged.

Conflicts of Interest

None.

REFERENCES

1. Parmar NRC, Sunandan S. Pattern of ocular injuries

in Haryana. Ind J Ophthalmol 1985;33:141-144.

2. Mulugeta A, Bayu S. Pattern of perforating ocular

injuries at Manelik 11 hospital, Addis Ababa. Ethiop

J Health Dev 2001;15:131-137.

3. Okoye OI. Eye injury requiring hospitalization in

JOURNAL OF OPHTHALMIC AND VISION RESEARCH 2011; Vol. 6, No. 2

117

Ocular Injuries in Nigeria; Omolase et al

Enugu, Nigeria. A one-year survey. Niger J Surg Res

2006;8:34-37.

17. Ilsar M, Chirambo M, Belkin M. Ocular injuries in

Malawi. Br J Ophthalmol 1982;66:145-148.

4. Nordber E. Injuries as a public health problem in

sub-Saharan Africa: Epidemiology and prospects for

control. East Afr Med J 2000;77:1-43.

18. Woo JH, Sundar G. Eye injuries in Singapore-Dont

risk it. Do more. A prospective study. Ann Acad Med

Singapore 2006;35:706-718.

5. AdemolaPopoola DS, Owoeye JFA. Gunshot

related binocular injuries. W J Med Sci 2006;1:65-68.

19. Thylefors B. Epidemiological patterns of ocular

trauma. Aust N Z J Ophthalmol 1992;20:95-98.

6. Olurin O. Eye injuries in Nigeria: A review of 433

cases. Am J Ophthalmol 1971;72:159-166.

20. Soliman MM, Macky TA. Pattern of ocular

trauma in Egypt. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol

2008;246:205-212.

7. Parver L. Eye trauma. The neglected disorder. Arch

Ophthalmol 1986;104:1452-1453.

8. Macewen CJ. Ocular injuries. J R Coll Surg Edinb

1999;44:317-323.

9. Negrel AD, Thylefors B. The global impact of eye

injuries. Ophthalmic Epidemiol 1998;5:143-169.

10. Glynn RJ, Seddon JM, Berlin BM. The incidence

of eye injuries in New England. Arch Ophthalmol

1988;106:785-789.

11. Desai P, MacEwen CJ, Baines P, Minaissian DC.

Epidemiology and implications of ocular trauma

admitted to hospital in Scotland. J Epidemiol Comm

Health 1996;50:436-441.

12. Chiapella AP, Rosenthal AR. One year in an eye

casualty clinic. Br J Ophthalmol 1985;69:865-870.

13. Vernon SA. Analysis of all new cases seen in a busy

regional ophthalmic casualty department during a

24-week period. J R Soc Med 1983;76:279-282.

14. Teilsch JM, Parver LM. Determinants of hospital

charges and length of stay for ocular trauma.

Ophthalmology 1990;97:231-237.

15. Michael I, Moses CH, Michael B. Ocular injuries in

Malawi. Br J Ophthalmol 1982;66:145-148.

16. Umeh RE, Umeh OC. Causes and visual outcome

of childhood eye injuries in Nigeria. Eye (Lond)

1997;11:489-495.

118

21. Mallika PS, Tan AK, Asok T, Faisal HA, Aziz S,

Intan G. Pattern of ocular trauma in Kuching,

Malaysia. Malaysia Fam Phys 2009;3:140-145.

22. Steven S. Primary care of eye injuries. J Comm Eye

Health 1997;10:59-60.

23. AdemolaPopoola DS, Odebode TO, Adigun AI.

Intentional enucleation of the eyes: an unusual cause

of binocular blindness. World J Med Sci 2006;1:158161.

24. Babar TF, Khan MT, Marwat MZ, Shah SA, Murad

Y, Khan MD. Patterns of ocular trauma. J Coll

Physicians Surg Pak 2007;17:148-153.

25. Mackiewicz J, Machowicz-Matejko E, Saaga-Pylak

M, Piecyk-Sidor M, Zagrski Z. Work-related,

penetrating eye injuries in rural environments. Ann

Agric Environ Med 2005;12:27-29.

26. Yaya G, Bobossi Serengbe G, Gaudeuille A. Ocular

injuries in children aged 0-15 years: epidemiological

and clinical aspects at Bangui National Teaching

Hospital. J Fr Ophtalmol 2005;28:708-712.

27. Nwosu SN. Domestic ocular and adnexal injuries in

Nigerians. West Afr J Med 1995;14:137-140.

28. Qureshi MB. Ocular injury pattern in Turbat,

Baluchistan, Pakistan. J Comm Eye Health 1997;10:

57-58.

JOURNAL OF OPHTHALMIC AND VISION RESEARCH 2011; Vol. 6, No. 2

You might also like

- Newborn Physical AssessmentDocument3 pagesNewborn Physical AssessmentFateaNo ratings yet

- Case Study On Ford MotorsDocument8 pagesCase Study On Ford Motorsabhishek_awasthi_150% (2)

- Gyorgy Cziffra - MemoirsDocument113 pagesGyorgy Cziffra - MemoirsLuis Miguel Gallego OntilleraNo ratings yet

- Retrospective Study of The Pattern of Eye Disorders Among Patients in Delta State University Teaching Hospital, OgharaDocument6 pagesRetrospective Study of The Pattern of Eye Disorders Among Patients in Delta State University Teaching Hospital, OgharaHello PtaiNo ratings yet

- Pattern of Ocular Trauma Seen in Grarbet Hospital, Butajira, Central EthiopiaDocument6 pagesPattern of Ocular Trauma Seen in Grarbet Hospital, Butajira, Central Ethiopiatrisya putri meliaNo ratings yet

- Etiological Factors of Ocular Trauma in Children and Adolescents Based On 200 Cases at The Pediatric Ophthalmology Unit of The Bouake University HospitalDocument7 pagesEtiological Factors of Ocular Trauma in Children and Adolescents Based On 200 Cases at The Pediatric Ophthalmology Unit of The Bouake University HospitalAthenaeum Scientific PublishersNo ratings yet

- Knowlegde and Willingness To Donate Eye Among Medical Doctors in Delta StateDocument7 pagesKnowlegde and Willingness To Donate Eye Among Medical Doctors in Delta StateInternational Organization of Scientific Research (IOSR)No ratings yet

- Pattern of Ocular Diseases Among Patients Attending Ophthalmic Outpatient Department - A Cross-Sectional StudyDocument11 pagesPattern of Ocular Diseases Among Patients Attending Ophthalmic Outpatient Department - A Cross-Sectional StudyDr. Abhishek OnkarNo ratings yet

- Changes of Patterns and Outcomes of Ocular and Facial Trauma Among Children in JordanDocument11 pagesChanges of Patterns and Outcomes of Ocular and Facial Trauma Among Children in JordanMoiz AhmedNo ratings yet

- International Glaucoma Association: Abebe Bejiga MDDocument2 pagesInternational Glaucoma Association: Abebe Bejiga MDDhika KusumaNo ratings yet

- Trau 1Document3 pagesTrau 1manognaaaaNo ratings yet

- Prevalenceand Associated Ffactorsof Visual Impairment Among School Age ChildrenDocument10 pagesPrevalenceand Associated Ffactorsof Visual Impairment Among School Age ChildrenDaniel AsmareNo ratings yet

- ManuscriptDocument11 pagesManuscriptsarjak shahNo ratings yet

- Dhaiban 2021Document7 pagesDhaiban 2021Eric PavónNo ratings yet

- Nigeria Jenis Penyebab TraumaDocument5 pagesNigeria Jenis Penyebab TraumaMahdiahNo ratings yet

- Provisional PDF Published Jan 26, 2010: Adeyi Adoga, Tonga Nimkur and Olugbenga SilasDocument10 pagesProvisional PDF Published Jan 26, 2010: Adeyi Adoga, Tonga Nimkur and Olugbenga SilasTeddy AttondeNo ratings yet

- Chemical Eye Injuries: Presentation and Management DifficultiesDocument5 pagesChemical Eye Injuries: Presentation and Management DifficultiesMuhammad SubhanNo ratings yet

- 227 Manuscript 538 1 10 20210129Document5 pages227 Manuscript 538 1 10 20210129Ayele BizunehNo ratings yet

- Most Common Ophthalmic Diagnoses in Eye Emergency Departments: A Multicenter StudyDocument8 pagesMost Common Ophthalmic Diagnoses in Eye Emergency Departments: A Multicenter StudyAlba García MarcoNo ratings yet

- Results of Surgery For Congenital Esotropia: Original ResearchDocument6 pagesResults of Surgery For Congenital Esotropia: Original ResearchkarenafiafiNo ratings yet

- Amj 06 560Document5 pagesAmj 06 560paulpiensaNo ratings yet

- Emergency Department Visits Related To Eye InjryDocument10 pagesEmergency Department Visits Related To Eye InjryHectorNo ratings yet

- Nurdin Zuhri Ocular Trauma 1Document14 pagesNurdin Zuhri Ocular Trauma 1Farid NurdiansyahNo ratings yet

- Eye Health Seeking Behavior and Its Associated Factors Among Adult Population in Mangu LGA Plateau State NigeriaDocument9 pagesEye Health Seeking Behavior and Its Associated Factors Among Adult Population in Mangu LGA Plateau State NigeriaAthenaeum Scientific PublishersNo ratings yet

- Theoretical and Conceptual FrameworkDocument14 pagesTheoretical and Conceptual FrameworkJelshan BawogbogNo ratings yet

- The Relation of Onset of Trauma and Visual Acuity On Traumatic PatientDocument6 pagesThe Relation of Onset of Trauma and Visual Acuity On Traumatic PatientNurlaila IshaqNo ratings yet

- Refractive Errors in Children With Autism in A Developing CountryDocument4 pagesRefractive Errors in Children With Autism in A Developing CountryAnifo Jose AntonioNo ratings yet

- Clinical Profile and Visual Outcome of Ocular Injuries in Tertiary Care Rural HospitalDocument8 pagesClinical Profile and Visual Outcome of Ocular Injuries in Tertiary Care Rural HospitalIJAR JOURNALNo ratings yet

- Emergency Department Visits Related Eye Injuries 2008Document10 pagesEmergency Department Visits Related Eye Injuries 2008Nguyễn HữuNo ratings yet

- Should We Say NO To Body Piercing in Children? Complications After Ear Piercing in ChildrenDocument3 pagesShould We Say NO To Body Piercing in Children? Complications After Ear Piercing in ChildrenGhalyRizqiMauludinNo ratings yet

- Amhsr 2 14Document5 pagesAmhsr 2 14Archana KrishnaNo ratings yet

- Ear Syringing - Trends From A Young Ent Practice in Nigeria: Original ResearchDocument4 pagesEar Syringing - Trends From A Young Ent Practice in Nigeria: Original ResearchnavnaNo ratings yet

- Celulitis PeriorbitariaDocument4 pagesCelulitis PeriorbitariaJose Carlos Guerra RangelNo ratings yet

- Adesunkanmi2021 Article ImpactOfTheCOVID-19PandemicOnSDocument8 pagesAdesunkanmi2021 Article ImpactOfTheCOVID-19PandemicOnSCarlosA.DíazNo ratings yet

- Jurnal MataDocument7 pagesJurnal Mataokky_rahmatNo ratings yet

- Dry Eye - WordDocument39 pagesDry Eye - WordJan IrishNo ratings yet

- Intracranial Tumors: An Ophthalmic Perspective: DR M Hemanandini, DR P Sumathi, DR P A KochamiDocument3 pagesIntracranial Tumors: An Ophthalmic Perspective: DR M Hemanandini, DR P Sumathi, DR P A Kochamiwolfang2001No ratings yet

- 34tupe EtalDocument5 pages34tupe EtaleditorijmrhsNo ratings yet

- Risk Factors For Myopia in Inner Mongolia Medical Students in ChinaDocument7 pagesRisk Factors For Myopia in Inner Mongolia Medical Students in ChinaChristabella Natalia WijayaNo ratings yet

- Ophthalmogenetic and Epidemiological Studies of Egyptian Children With Mental RetardationDocument8 pagesOphthalmogenetic and Epidemiological Studies of Egyptian Children With Mental Retardationray m deraniaNo ratings yet

- Management of Foreign Bodies in The Ear: A Retrospective Review of 123 Cases in NigeriaDocument5 pagesManagement of Foreign Bodies in The Ear: A Retrospective Review of 123 Cases in NigeriaElrach CorpNo ratings yet

- China Risk FactorsDocument6 pagesChina Risk FactorsNoor MohammadNo ratings yet

- A Cross Sectional Study of Refractive ErDocument6 pagesA Cross Sectional Study of Refractive Er0039 NURUL HANI IZZUANI BINTI AFRIZANNo ratings yet

- Aes 04 9Document6 pagesAes 04 9Ignasius HansNo ratings yet

- Prevalence and Consequence of Customized Ocular Prosthesis in Last 15 Years at Dhaka City, Bangladesh: A Retrospective StudyDocument6 pagesPrevalence and Consequence of Customized Ocular Prosthesis in Last 15 Years at Dhaka City, Bangladesh: A Retrospective Studymohammaddu49No ratings yet

- You Et Al-2014-Acta OphthalmologicaDocument9 pagesYou Et Al-2014-Acta OphthalmologicaviviNo ratings yet

- Prevalence and Associated of Occular Morbidity in Luzira-UgandaDocument8 pagesPrevalence and Associated of Occular Morbidity in Luzira-Ugandadramwi edwardNo ratings yet

- Sciencedirect: Prevalence and Etiology of Midfacial Fractures: A Study of 799 CasesDocument6 pagesSciencedirect: Prevalence and Etiology of Midfacial Fractures: A Study of 799 CasesSuci NourmalizaNo ratings yet

- An Injury Profile of Maxillofacial Trauma in Yaounde An Observational Study in CameroonDocument9 pagesAn Injury Profile of Maxillofacial Trauma in Yaounde An Observational Study in CameroonAthenaeum Scientific PublishersNo ratings yet

- Research Article: Prevalence and Risk Factors For Adult Cataract in The Jingan District of ShanghaiDocument7 pagesResearch Article: Prevalence and Risk Factors For Adult Cataract in The Jingan District of ShanghaiIndermeet Singh AnandNo ratings yet

- Joph2016 1438376 PDFDocument6 pagesJoph2016 1438376 PDFdesytrilistyoatiNo ratings yet

- Journal Pone 0268800Document19 pagesJournal Pone 0268800YAP JOON YEE NICHOLASNo ratings yet

- Epidemiological Study of Ocular Trauma in An Urban Slum Population in Delhi, IndiaDocument4 pagesEpidemiological Study of Ocular Trauma in An Urban Slum Population in Delhi, IndiaSitifa AisaraNo ratings yet

- Femi OgundeleDocument8 pagesFemi OgundeleAbdullahi nurudeenNo ratings yet

- Epidemiology of Ocular Tumors 2013Document230 pagesEpidemiology of Ocular Tumors 2013Ranny LaidasuriNo ratings yet

- Eye Banking and Corneal Transplantation in Tertiary Care Hospital Located in Rural AreaDocument6 pagesEye Banking and Corneal Transplantation in Tertiary Care Hospital Located in Rural AreaIOSR Journal of PharmacyNo ratings yet

- Visual Impairment and Blindness in A Population-Based Study of Mashhad, IranDocument8 pagesVisual Impairment and Blindness in A Population-Based Study of Mashhad, IranSubhan Nur RamadhanNo ratings yet

- Managing Myopia Clinical Guide Dec 2020Document12 pagesManaging Myopia Clinical Guide Dec 2020Jorge Ivan Carcache LopezNo ratings yet

- Relationship of Dissociated Vertical Deviation and The Timing of Initial Surgery For Congenital EsotropiaDocument4 pagesRelationship of Dissociated Vertical Deviation and The Timing of Initial Surgery For Congenital EsotropiaMacarena AlvarezNo ratings yet

- Javed and Kashif Split PDF 1674305144401Document4 pagesJaved and Kashif Split PDF 1674305144401criticseyeNo ratings yet

- Prevalence of Blindness in Patients With Uveitis: Original ResearchDocument4 pagesPrevalence of Blindness in Patients With Uveitis: Original ResearchMuhammad RaflirNo ratings yet

- Journal Reading On Fall InjuryDocument20 pagesJournal Reading On Fall InjuryMAE DEVILLANo ratings yet

- Ajcr 4 47Document2 pagesAjcr 4 47paulpiensaNo ratings yet

- Negative G-Force Ocular Trauma Caused by A Rapidly Spinning CarouselDocument4 pagesNegative G-Force Ocular Trauma Caused by A Rapidly Spinning CarouselpaulpiensaNo ratings yet

- Amj 06 560Document5 pagesAmj 06 560paulpiensaNo ratings yet

- Cochrane ShowDocument14 pagesCochrane ShowpaulpiensaNo ratings yet

- En V68n5a5Document5 pagesEn V68n5a5paulpiensaNo ratings yet

- A New Ocular Trauma Score in Pediatric Penetrating Eye InjuriesDocument5 pagesA New Ocular Trauma Score in Pediatric Penetrating Eye InjuriespaulpiensaNo ratings yet

- Newsltr Jan 2012Document112 pagesNewsltr Jan 2012paulpiensaNo ratings yet

- Surgical Treatment of Severely Traumatized Eyes With No Light PerceptionDocument6 pagesSurgical Treatment of Severely Traumatized Eyes With No Light PerceptionpaulpiensaNo ratings yet

- Artikel Jurnal KKN PuyantiDocument6 pagesArtikel Jurnal KKN Puyantipuyanti -No ratings yet

- ATR100 Owners Manual PDFDocument20 pagesATR100 Owners Manual PDFHernan Alberto Orozco CastañoNo ratings yet

- AMI System Using DLMS - White PaperDocument6 pagesAMI System Using DLMS - White PaperBijuNo ratings yet

- Sci 9-DLP 2Document5 pagesSci 9-DLP 2elsie tequinNo ratings yet

- Redox Reactions in 1 ShotDocument66 pagesRedox Reactions in 1 ShotBoss mayank100% (1)

- Balancing Chemical Equations HTML Guide - enDocument2 pagesBalancing Chemical Equations HTML Guide - enMiguel ApazaNo ratings yet

- Hero Project Kedar BBADocument49 pagesHero Project Kedar BBAVinod HeggannaNo ratings yet

- AT8611 Lab QuestionsDocument9 pagesAT8611 Lab QuestionsChirpiNo ratings yet

- 非谓语动词练习题(学生)Document2 pages非谓语动词练习题(学生)huangyj970218No ratings yet

- Nakagami Vs Ricean FadingDocument2 pagesNakagami Vs Ricean Fadingdelwar28No ratings yet

- Week 1 - Assessment #1Document2 pagesWeek 1 - Assessment #1elaineNo ratings yet

- Jackman 1996Document66 pagesJackman 199612545343No ratings yet

- Admission Notification: 3 Floor, Composite Arts Building, Golapbag Golapbag, Burdwan: - 713 104 West Bengal, IndiaDocument3 pagesAdmission Notification: 3 Floor, Composite Arts Building, Golapbag Golapbag, Burdwan: - 713 104 West Bengal, IndiaHemnath Patra দর্শনNo ratings yet

- RRN3901 Spare Parts CatalogDocument11 pagesRRN3901 Spare Parts CatalogleonardomarinNo ratings yet

- PDK 025786 Diagnose enDocument296 pagesPDK 025786 Diagnose enMalek KamelNo ratings yet

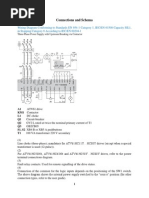

- Connections and SchemaDocument7 pagesConnections and SchemaKukuh WidodoNo ratings yet

- Washing Machine Manual Kenmore HE5tDocument76 pagesWashing Machine Manual Kenmore HE5tmachnerdNo ratings yet

- Flame Tests and Atomic SpectraDocument3 pagesFlame Tests and Atomic SpectraImmanuel LashleyNo ratings yet

- Correlation and RegressionDocument39 pagesCorrelation and RegressionMuhammad Amjad RazaNo ratings yet

- RidleyWorks15 02Document112 pagesRidleyWorks15 02Sergio Omar OrlandoNo ratings yet

- AirValves 2013 PDFDocument268 pagesAirValves 2013 PDFSergio Sebastian Ramirez GamiñoNo ratings yet

- Clinical MedicineDocument18 pagesClinical MedicineRishikesh AsthanaNo ratings yet

- Inquiries Investigation and ImmersionDocument61 pagesInquiries Investigation and Immersionmutsuko100% (4)

- Dec Hanu Tht2 Writing Week 4 - Effect ParagraphDocument11 pagesDec Hanu Tht2 Writing Week 4 - Effect ParagraphHồng BắcNo ratings yet

- Manual Proportional Directional Control Valve (With Pressure Compensation, Multiple Valve Series)Document6 pagesManual Proportional Directional Control Valve (With Pressure Compensation, Multiple Valve Series)Fawzi AlzubairyNo ratings yet

- End Yoke PDFDocument96 pagesEnd Yoke PDFadamtuongNo ratings yet

- Admisie Aer-En 2013Document8 pagesAdmisie Aer-En 2013ionut2007No ratings yet