Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Wamukota 215-224

Wamukota 215-224

Uploaded by

BabadimplesOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Wamukota 215-224

Wamukota 215-224

Uploaded by

BabadimplesCopyright:

Available Formats

Western Indian Ocean J. Mar. Sci. Vol. 8, No. 2, pp.

215 - 224, 2009

2009 WIOMSA

The Structure of Marine Fish marketing in Kenya:

The Case of Malindi and Kilifi Districts

Andrew Wamukota

Kenya Sea Turtle Conservation Committee, PO Box 58-80122, Mombasa, Kenya .

Keywords: Fish marketing, marketing channel, market structure, constraints.

AbstractIn Kenya, the marine sub-sector, though a significant source of livelihood

and employment, remains small in terms of contribution to the national economy. This

study, undertaken between October 2000 and March 2001, examines and provides an

insight into the structure of marine fish marketing as well as identifies constraints in

the marketing system in Malindi and Kilifi districts. Through the use of questionnaires,

informal interviews, observation and review of secondary information, two main

marketing channels, differentiated by gender and value added practices (mainly frying),

were identified. Factors determining the choice of a marketing channel were found

to be ownership of storage facilities, profit margin and time to selling location, while

constraints in the marketing system related to infrastructure and socio-economic factors.

The study recommends investment in fish storage facilities as a way of strengthening

the marine fish marketing structure by improving the bargaining power of traders and

increasing profit margins.

INTRODUCTION

Fish has been the worlds major commodity

traded for more than a thousand years and has

influenced living conditions for just as long

(Kaplinsky 2000). Trade in seafood products

has continued to increase over the past two

decades from an average of 35% between

1984 and 1994 to an annual average of

37% of world catch between 1995 and 2003

(Gudmundsson et al. 2006).

In 2003, fish was a source of protein for about

2.6 billion people and constituted about 16% of

animal protein (FAO, 2004). The first level sale

value of fish catch amounted to around US$ 78

billion, while about 50 million tonnes of fish and

E-mail:awamukota@yahoo.com

fishery products entered the global trade, with

an estimated value of US $ 58.2 billion (FAO,

2004). Employment in capture fisheries has

grown at a rate of 2.6% since 1990 supporting

livelihoods of 100-200 million people directly

or indirectly, ninety percent of them living in

developing countries (FAO, 2004).

Changes in the institutional framework,

and particularly the introduction of 200 mile

Exclusive Economic Zones (EEZs), have

given coastal nations control over most fish

stocks (Munro 1996), thereby creating new

opportunities and challenges for fishermen

and the seafood industry all over the world.

In Kenya, the fisheries resources comprise

the freshwater (lakes, rivers and dams) and

marine sub-sectors. However, Lake Victoria

216

A. WAMUKOTA

is the main source of fish production in the

country as it contributes over 90% of the

total Kenyan fish landings (Karuga and Abila

2007). The rest is shared among other fresh

water sources and the marine sub-sectors.

The fisheries contribution to the countrys

economy is through employment creation,

generation of income and foreign exchange

earnings.

In terms of employment the fisheries

department estimated in 1995 that 798,000

Kenyans were, directly or indirectly, supported

by the sector in comparison to 720,000 in

1993. In the same year (1995), the department

estimated that there were 34,000 fishermen

with an estimated 238,000 dependants and

about 526,000 other people engaged in the

provision of support and ancillary services

such as trade in fish inputs, fish handling,

processing and marketing.

The value of fish landed in Kenya in 1996,

was Ksh. 6,667 million, increasing to Ksh.

7,668 million in 2002 (Gitonga and Achoki

2003). The industry is believed to be an

increasingly important source of food even to

people living far away from the fish producing

areas (Ikiara, 1999). The fishing industry is

the lifeline for the Kenyan riparian and coastal

communities in terms of its contribution to

employment and income.

Fish marketing

Fish marketing in Kenya has a long history

(see Adhiambo, 1988, Ogutu, 1988). The

structure of some fish market has been

documented (Abila 1995; Kasirye-Alemu

1988; Abila and Jansen 1997: Karuga and

Abila 2007) although most accounts relate

to the fresh water fishery. The structure of

marine fish marketing in Kenya can best be

understood from the forces that define it,

starting from fishing itself.

Fishing is carried out at two distinct

levels, artisanal and industrial and to

some extent ornamental and sport fishing.

Artisanal fishing is the most commonly

practiced by artisanal fishers who form an

estimated 99.5% of the fisher folk commonly

using simple wooden fishing vessels (Karuga

and Abila 2007). The estimated 10,154

fishermen (Kamau et al., 2009) operate an

approximately 2,400 non-motorized craft

of various types. The most common being

the dug-out canoe (hori) which account for

about 58% of all artisanal marine fishing

vessels in the coast region, followed by the

wind propelled sail boats (mashua) which

account for nearly 22%. Only about 7.5% of

the artisanal subsector boats are motorized.

Karuga and Abila (2007) estimates that 95%

of the fishing boats and gears are mostly

owned by boat owners who in most cases

are also fish dealers in that they undertake

the functions of wholesaling, retailing or

both. Only a few boats and mostly dugout

canoes are actually owned by fishermen

themselves.

Reliable data and information regarding

the contribution of marine fisheries is scanty

(Karuga and Abila 2007). However, it is

estimated that the subsector accounts for

around 4% of the total national catch and

employs around 10,000 fishers (Department

Fisheries, 2006). Although it remains small

(Kamau et al, 2009), the marine subsector

is very important to Kenyas economy as a

source of livelihood, employment and foreign

exchange earnings. The subsector contributes

about 0.3% of Kenyas GDP, while over 10,000

people are estimated to derive their livelihood

directly from fishing activities (Kamau et

al. 2009) and an estimated 200,000 work

in ancillary activities- trade, boat building,

engine repair and gear sales (Mwakilenge,

1996). Though large, these figures are only

estimates as there is little information and data

to confirm their reliability as different sources

give dissimilar information.

Nevertheless, information available

indicates that the artisanal fisheries alone,

which is estimated to handle an estimated

7,000 MT of fish annually is larger than

the industrial fishery (Karuga and Abila

2007). Data on fish (or prawns) landed

by industrial fishing companies is not

THE STRUCTURE OF MARINE FISH MARKETING IN KENYA

well documented, making it difficult to

provide sufficient insights into the relative

importance of this channel in terms of the

volume of business handled, employment

and earnings. The contribution of the marine

fishery to livelihoods, employment and

foreign exchange cannot be underestimated,

yet this has happened against the backdrop

of various structural constraints (Ochiewo

2004, Kamau et al, 2009) that resulted in the

fishery remaining relatively small. The sub

sector constraints, also termed as driving

forces, include heavy reliance on coastal

markets where about 95% of marine fish

landed along the Kenyan coast is consumed

locally (Karuga and Abila, 2007).

The presentation of various constraints

relating to marine fishery in Kenya by

Ikiara (1999) is useful in providing

general theoretical information. So is

the identification of subsector channels

(Karuga and Abila 2007). However salient

features of the market structure at specific

sites may not necessarily be captured. This

study goes beyond theoretical and anecdotal

information regarding marine fish marketing

structure to undertake empirical analysis that

identifies fish marketing channels, factors

that influence the choice of a marketing

channel and constraints in Malindi and Kilifi

districts.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

A market survey of fish traders was carried

out in Malindi and Kilifi districts between

October 2000 and March 2001 at four landing

sites (Ngomeni, Mayungu, Uyombo and

Takaungu) (Fig. 1). The survey of traders at

the market centers was carried out at four

market centers in close proximity to the four

landing sites. The market centers sampled are

Ngomeni, Malindi, Matsangoni and Takaungu

(Fig. 1). Most questions related to the situation

on the day of the interview although some

questions related to the past. A total of 231

traders from all the landing sites and market

centers were sampled randomly (Schaeffer and

217

Mendenhall, 1990) and interviewed. Effort

was made to have equal distribution of traders

in the landing sites as well as in the market

centers sampled. Data collection techniques

included structured questionnaires, informal

interviews, observation and use of secondary

data from published and unpublished reports.

Data Analysis

Factors determining the choice of a fish

marketing channel were analyzed using a

logit model. From the dichotomous value of

the dependent variable the logistic analysis

estimates the probability that, given the

independent variables, an event will or will

not occur (Dijkstra, 1997). If the predicted

probability is greater than 0.5 the prediction

is yes, otherwise the prediction is no

(Hair et al., 1995). The logit model estimated

(as depicted in (i)) was adapted from Dijkstra

(1997) and modified to suit this study.

Thus

L = 0 + i xi ........................................

(i) ...............

where L is the logit symbol and adopts a

dichotomous value 1 if channel 2 for processed

fish and 0 if channel 3 for fresh fish. The xi,

are coefficients of the independent variables.

They refer to a comparison of the probability

of the event occurring with the probability of

it not occurring. The probability of an event

occurring is calculated as shown in equation (i).

Accordingly, individual i will make a certain

choice, given the knowledge of xi. A positive

coefficient increases the probability that the

event will occur and a negative one decreases

it (Dijkstra, 1997). The variables estimated are

as shown in Table 1. The goodness of fit of the

model was assessed by means of the model chisquare at 0.01 and 0.05 significant levels. Any

variable exceeding 0.05 significance level was

considered insignificant. Chi-square tests the

null hypothesis that the coefficients for all the

terms in the model except the constant are zero.

If the null hypothesis is rejected (p< 0.05) the

model is meaningful (Norusis, 1990).

218

A. WAMUKOTA

Fig. 1. Map showing the study area

For all the regressors included in the model,

R2 values for the auxiliary regressions ranged

from 0.073 to 0.70. It was therefore concluded

that multicollinearity was not severe. Results

were checked for extreme cases, correlations

between independent variables using auxiliary

regressions and heteroscedasticity (a condition

when the variance depends on one or more

explanatory variable) using the GoldfeldQuandt test (Haddad et al., 1995).

Constraints in the fish

marketing system

The demand function was analysed using

the consumer theory of demand and supply

(Varian, 1990; Lipsey, 1995) adapted from

Deaton and Muellbauer (1980) taking into

account the equality of demand and supply

assumption (equation (ii)).

Thus

Si = i+X i+ijPj(ii)

where Si= the quantity of fish marketed

and Xi, ij, Pj= Independent variables.

The estimated equation whose variables

are presented in Table 1 was of the form

shown in (iii) below:

Qd (NLQAAFS) = OFSF, NLHHS, Educ, NLSPFS, SEX, NLTTSPS .... (iii)

Since the application of ordinary least squares

(OLS) to a system of simultaneous equation

yields biased and inconsistent estimates, the two

stage least squares (2SLS) method was used to

estimate parameters of the model. The 2SLS

aims to eliminate the simultaneous equation

bias, is appropriate for the estimation of overidentified equations and has the advantage of

simplicity in conception and computations

(Koutsoyiannis, (1977). The overall strength of

the model was expressed by the adjusted R2.

THE STRUCTURE OF MARINE FISH MARKETING IN KENYA

219

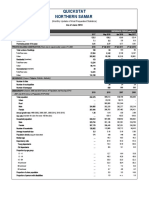

Table 1. Variables used in models to determine 1: factors determining the choice of marketing

channel and 2: constraints in the fish marketing system

1. Factors determining the choice of marketing channel

Variable

Symbol

Measurement

Form in which the fish is marketed (Dependant) FTFM

1=own, 0=not own

Ownership of fish storage or cooling facility

OFSF

1= owns, 0= does not own

Quantity of fish sold

NlqAAFS

Kilograms

Profit margins

NLMARGIN

Kenya shillings

Transport time to selling point

TTSP

Hours

Quantity of fuel wood used for fish

processing per day

INVQFUPD

Kilograms

Quantity of fish sold (Dependant)

NLQAAFS

Kilograms

Ownership of fish storage facility

OFSF

1= owns, 0= does not own

Number of household members

NLHHS

Count

Education

Nl educ

Number

Selling price of fish

NLSPFS

Kenya shillings

Sex

SEX

1=male, 0=female

Transport time to selling point

NLTTSPS

Hours

2. Constraints in the fish marketing system

RESULTS AND DISCUSSIONS

Marine fish marketing starts at the point

where fish is landed, although this process

is dependant on the prior activity of fishing

itself which to a degree is financed by owners

of fishing vessels. It is argued (Karuga and

Abila 2007) that 95% of the fishing boats

and gears are mostly owned by boat owners

who in most cases are also fish dealers in that

they undertake the functions of wholesaling,

retailing or both, and that only a few boats and

mostly dugout canoes are actually owned by

fishermen themselves.

Boat owners finance fishing by providing

fishing boats and sometimes fishing gear

to fishers. After fish is landed under this

arrangement, the proceeds are shared in order of

agreed sharing methods (see Karuga and Abila

2007). In some instances, the fisher folks have

been reported to pay a rental fee of Ksh 200

and 100 per day for use of sail boat and dugout canoes respectively. In other instances, the

boat owner may advance small amounts of the

payment to the fishermen with the balance being

paid later. Fish sale by the boat owner may be

at or away from the landing site. The latter may

be direct sale to a fish dealer or sale to retailers

at the dealers shop (s), located in the main

consumer markets.

Part of the catch is however sold to women

who are commonly referred to as mama

karangas (women who buy fish and later

deep-fry it and sell to household consumers)

or to local household consumers. According

to a recent survey (Karuga and Abila 2007),

the mama karangas control over 95% of the

marine fish retailing function. These actors

buy fish from wholesalers (about 80% of

purchase), directly from fishermen or in some

places from industrial fishing companies in the

form of by-catch. Nearly all of these retailers

220

A. WAMUKOTA

operate from makeshift structures along the

main streets and villages. Their main outlets

are household consumers/ general public in

towns and villages.

Wholesaling is exclusively carried out by

larger scale traders, who more often than not

own fishing vessels and gears. However, reliable

data on the number of dealers or wholesalers

is not well known although anecdotal

information indicates that majority of them are

men. Wholesalers normally deal with between

300-500 kilograms of fish per day while other

dealers deal with as little as 50-100 kilograms

of fish per day or even less. The main sources

of fish for this type of actors include fishers

(supplying over 75%) and middlemen.

The traders interviewed ranged from 19

to 60 years old although the majority fell in

the age bracket of between 20 to 29 years.

An almost equal number of male and female

traders operated at the sampled sites. Although

gender was not a limiting factor in fish

marketing, female traders focused on small

fish of smaller quantities for local sales while

men bought and sold the larger quantities of

fish. An increase in male traders meant an

increase in the quantity of fish traded. Traders

from the Mijikenda group were in the majority

followed by the Bajuni. Almost 43% of the

traders had primary school education while

30% did not have any formal education. The

majority of the traders were Muslims.

Fig. 2. Main fish marketing channels in Malindi and Kilifi districts 2000/01

THE STRUCTURE OF MARINE FISH MARKETING IN KENYA

In total, six fish marketing channels (Fig.

2) were identified. The dividing line between

the channels was the scale at which the traders

operated, the quantity of the product, its extent

and value adding practice (processing). These

were to a large extent dictated by the volume

of fish bought and sold, and ownership of

storage as well as transport facilities. It should

be noted that despite fish being a highly

perishable product, the majority of the 115

landing sites on the whole of the Kenyan coast

do not have fish storage facilities (Karuga and

Abila 2007). During the survey, only two

landing sites had a container sometimes with

ice, which were owned by large-scale traders.

Four distinctions of traders were identified.

These were mama karangas, small scale

traders, middlemen and large scale traders/

wholesalers depending on the quantity of fish

traded, the type (fresh or processed) and the

scale at which they operated.

Results of this study indicate that fish

marketing is done first at the landing sites and

then at various markets beyond the landing

sites. Fish marketing at the landing sites

was mostly done by fishermen who sold fish

to traders or to consumers. Mama karanga

fish mongers bought fish in small quantities

for deep frying and selling at nearby market

centers or villages (Table 2). Female traders

who bought fish from industrial companies

were not encountered. Small-scale traders

bought fish from fishermen at the landing

site and sold it to middlemen or sometimes to

consumers in its fresh form (channels 2 and 6)

221

at the nearby villages, tarmac roads or market

centers while middlemen bought the fish from

small-scale traders or even fishers and sold to

large scale traders or other traders operating

retail shops. Some were subcontracted by

large scale traders to buy fish on their behalf.

In some cases, large-scale traders sold fish

to middlemen who operated retail shops

or directly to consumers (household and

hotels). Large-scale traders on the other hand

bought fish in bulk from fishermen, smallscale traders or middlemen. Some large-scale

traders owned fishing vessels and therefore

visited the landing sites to collect fish landed

by their vessels (channel 4) or subcontracted

middlemen to buy fish for them. They later

sold it to hotels or other traders in Malindi,

Mombasa, Kilifi or Nairobi in fresh form. The

large scale traders encountered were mostly

individuals and not companies and were very

few compared to artisanal fishermen who

operated on their own.

In general, apart from traders who

exclusively processed fish in small quantities

by mostly frying before marketing it (mama

karangas), other trader categories mainly

dealt in comparatively larger quantities of

fresh fish. Also the quantities of fish that a

particular trader dealt in for instance did not

exclusively depend on the traders financial

position but to an extent the amount of fish he/

she could manage to get in a day depending

on networks and or contracts and landings.

This influenced the scale at which some

operated. Considering all these factors, the

Table 2. Fish marketing channels and volumes in Malindi and Kilifi districts 2000/01

Channel

Number Volume

Std. Mean

deviation

Fishersmall-scale traderconsumer

331

45.6

36.7

Fisherfishmongerconsumer

74

458

5.5

6.2

Fisherlarge-scale traderconsumer

15

546

24.7

36.4

Fishersmall-scale traderLarge-scale traderconsumer

17

566

30.76 33.3

Fishersmall-scale tradermiddlemanLarge-scale traderconsumer 25

1199

35.57 48

Total

3099

28.8

140

22.1

222

A. WAMUKOTA

marketing channels depicted in Fig. 2 can be

divided into the two most conspicuous gender

differentiated, with women dominating the

fish processing/ mostly frying channel and

men concentrating on the fresh fish channel.

Although the subsector map presented

(Fig. 2) should not be looked at as static, it

illustrates the mostly observed marketing

channels. The channel that carried the largest

volume of fish was the channel fisher>smalls c a l e > t r a d e r > m i d d l e m e n > l a rg e - s c a l e

traders>consumer (household or restaurants)

(Table 2).

Results of the logistic analysis points

to ownership of storage facilities as a

determinant of the choice of marketing

channel. Preliminary results indicated

that mama karangas lacked most of the

infrastructure including storage facilities

(apart from wooden boxes in which they

put processed fish for display) and means

of transport. Only about 40 % of the traders

mostly female traders transported their fish

on foot and another 37 % used bicycles. Only

three percent of the traders had their own

vehicles, which they used to transport fish to

various selling locations.

Ownership of fish storage facilities also

acted as a constraint (Table 3) in the fish

marketing system. The lack of fish storage

facilities is not limited to the surveyed sites,

but are lacking in many parts of the Kenyan

coast (Karuga and Abila 2007).

CONCLUSIONS

Most accounts of fish marketing in Kenya

relate to fresh water fishery which contributes

over 90 % of fish production in Kenya.

Research done so far with regard to marine

fisheries marketing points out to the paucity

of data and information with regard to some

players in the marketing channel. In this

study a more specific and site based empirical

analysis is undertaken in order to expose

salient interactions and processes that define

the structure of marine fish marketing in two

districts of Malindi and Kilifi, Kenya.

The salient interactions relate to the steps

of fish marketing and players involved, with

mama karanga fish trader category specializing

in processed fish. Very few large-scale traders

were encountered in the marketing channel.

This trader category influenced financing of

fishing by providing fishing boats and gear

Table 3. 2SLS estimates for the constraints in the fish marketing system in Malindi and Kilifi districts

2000/01

Variable

INVQAAFS

SE B

Beta

Sig T

.1649

-4.280173

3.009465

-.577575

-1.422

1.501086

.484798

.663641

3.096

.0041**

.295485

.156990

.263706

1.882

.0692*

NLEDUC

-.174481

.366778

-.072194

-.476

.6376

NLSPFS

-.095690

.278448

-.049700

-.344

.7334

GENDER

.396014

.371576

.216152

1.066

.2948

.062174

.103802

1.339430

.486

1.839

.6301

.0755*

OFSF

NLHHS

NLTTSPS

(Constant)

.030245

2.463717

* Significant at 10 % significant level,

Dependent variable: NLQLFB,

df = 7, Sig. F = .0002

** significant at 5% significant level

Adjusted R Square=. 47575, Standard Error=. 70170, F = 5.92637,

THE STRUCTURE OF MARINE FISH MARKETING IN KENYA

and sometimes engaged middlemen to buy

fish on their behalf. Determinants of choice

of marketing channels related to ownership

of storage facilities and to some extent time

taken to fish selling locations. The ownership

of fish storage facilities also acted as a major

constraint. Results of this study suggest the

need to invest in fish storage and preservation

facilities at landing sites.

AcknowledgmentsI am grateful to Moi

University for offering me a chance to pursue

my M. Phil and for enabling me write my

thesis of which this paper is part. I particularly

thank my supervisors, Professor H. Maritim,

Professor W. Yabban, and Professor B.C.C.

Wangila who encouraged me all through.

Research grant was provided by the

Netherlands and Israel Research Program

(NIRP). I am particularly indebted to Professor

Jan Hoorweg of the African Study Centre who

was instrumental in providing field facilitation

and direction during the initial phase of this

study. Thanks also to research assistants in the

study areas.

REFERENCES

Abila R.O (1995). Assessment of Fisheries

Products Values along Kenyas Export

Marketing Chain. Proceedings of the FAO

Expert Consultation on Fish Technology,

Utilization and Quality Assurance, 14-18th

November 2005, Bagamoyo, Tanzania.

Abila, R.O. and E.G. Jansen (1997). From Local

to Global Markets: The Fish Exporting

and Fishmeal industries of Lake Victoriastructure, strategies and socio-economic

impacts in Kenya. Socio-economics of the

Nile perch Fishery of Lake Victoria Project

Report No.2. IUCN-EARO. Nairobi.

Adhiambo, W.J.O. (1988). Lake Victoria Fisheries

and Fish trade, In Ogutu, G.E.M ed.

Artisanal Fisheries of Lake Victoria, Kenya:

Options for Management, Production, and

Marketing. Sirikon Publishers and IDRC,

Nairobi. pp. 63-75.

Deaton A. and John Muellbauer (1980). An Almost

Ideal Demand System. The American

Economic Review, 70 (3): 312-326.

223

Department of Fisheries (2006). Marine Waters

Frame Survey Report, 2006.

Dijkstra,T. (1997). Trading the fruits of the land.

Horticultural marketing channels in Kenya.

Ashgate Publishing Ltd. Aldershot.

FAO (2004). The state of the world Fisheries and

Aquaculture 2004. FAO. Rome, Italy .

Gitonga, N.K. and Achoki, R. (2003), Fiscal

Reforms for Kenya Fisheries: Paper Prepared

for FAO Workshop on Fiscal Reforms for

Fisheries (Rome, Italy: 13-15 October 2003).

Available online at:

http://www.fao.org/docrep/007/y5718e/y5718e04.htm

Gudmundsson, E.; Asche, F.; Nielsen, M. (2006).

Revenue distribution through the seafood

value chain. FAO Fisheries Circular. No.

1019. Rome, FAO.

Haddad, L., Westbrook M.D., Driscol, D.,

Payongayong, E., Rozen, J., and Weeks,

M. (1995). Strengthening Policy Analysis:

Econometric tests using Microcomputer

Software. Microcomputer in Policy research

2, IFPRI, Washington D.C.

Hair, J. F., R.E. Anderson, R.L. Tathan and W.C.

Black (1995). Multivariate Data Analysis.

4th ed. Prentice Hall. Englewoods Cliffs.

Ikiara, M.M. (1999). Sustainability, Livelihoods,

Production and Effort supply in a Declining

Fishery. The case of Kenyas Lake Victoria

Fisheries. PhD Thesis (unpublished)

University of Amsterdam.

Kamau E.C., Wamukota A., and Muthiga N.

(2009) Promotion and Management of

Marine Fisheries in Kenya In Winter, G

(Ed). Towards Sustainable Fisheries Law.

Comparative Analysis. IUCN, Gland,

Switzerland. xiv + 340 pp.

Kaplinsky, R. (2000). Spreading the Gains from

Globalisation: What Can Be Learned

from Value Chain Analysis? Institute of

Development Studies, Working Paper 110,

Sussex.

Karuga S. and R. O. Abila (2007). Value

Chain Market Assessment for Marine

Fish Subsector in Kenyas Coast

Region. Consultancy Report for the

Coast Development Authority. Coastal

Micro-Enterprise Development Program.

Mombasa. Kenya.

224

A. WAMUKOTA

Kasirye-Alamu, E. C. (1988). Fish handling and

processing in Artisanal Fisheries of Lake

Victoria, Kenya, in Ogutu, G.E.M., (ed.)

(1988). Artisanal Fisheries of Lake Victoria,

Kenya: Options for management, production

and marketing. Proceedings of a workshop

held in Kisumu, Kenya

Koutsoyiannis, A. (1977). Theory of Econometrics.

The Macmillan Press Ltd.

Lipsey, R.G. (1995). An introduction to positive

economics. Oxford University press. New

York.

Munro, G.R. (1996). Approaches to the

Economics of the Management of High

Seas Fishery Resources. In D. V. Gordon

and G. R. Munro (1996). Fisheries and

Uncertainty: A Precautionary Approach

to Resource Management. University of

Calgary Press, Calgary.

Mwakilenge, E. (1996). Toward Sustainable

Development in the Fishing Industry of

Coast Province In: Technical Report No. 1.

Department of Fisheries, Moi University.

Norusis, M.J. (1990). SPSS Advanced Statistics

Student Guide, SPSS Inc.: Chicago.

Ochiewo, J. (2004) Changing fisheries practices

and their socioeconomic implications in

South Coast Kenya. Ocean & Coastal

Management, 47(7-8): 389-408pp.

Ogutu, M.A (1988). The role of women and

cooperatives in Fish marketing in Western

Kenya. In Ogutu G.E.M ed. (1988) Artisanal

Fisheries of Lake Victoria, Kenya: Options

for management, production and marketing.

Proceedings of a workshop held in Kisumu,

Kenya. pp.113-117.

Schaeffer, L.R and Mendenhall W., (1990).

Elementary survey sampling.4th Ed.,

Duxbury press. Belmond.

Varian, H. (1990). Intermediate Microeconomics

2nd edition. W.W.Norton and company Ltd.

London pp 1-33.

You might also like

- Ethiopian Herbs and SpicesDocument11 pagesEthiopian Herbs and SpicesyosefNo ratings yet

- Horse & Other Equine Production in The US Industry Report PDFDocument36 pagesHorse & Other Equine Production in The US Industry Report PDFOozax OozaxNo ratings yet

- Fish Processing PlantDocument54 pagesFish Processing PlantYoseph Melesse86% (7)

- Feasibility Study - Benin CanteenDocument16 pagesFeasibility Study - Benin CanteenJoanNe PatingNo ratings yet

- Status of Ornamental Fish Industry in The Philippines: Prospects For DevelopmentDocument16 pagesStatus of Ornamental Fish Industry in The Philippines: Prospects For DevelopmentMichael JulianoNo ratings yet

- 09 - Chapter 2 PDFDocument39 pages09 - Chapter 2 PDFamanNo ratings yet

- Damian's JournalDocument21 pagesDamian's Journalanidamian14No ratings yet

- Status of Ornamental Fish Industry in The Philippines.' Prospects For Development PDFDocument16 pagesStatus of Ornamental Fish Industry in The Philippines.' Prospects For Development PDFRyan PurisimaNo ratings yet

- 04 Aextj 364 23Document8 pages04 Aextj 364 23BRNSS Publication Hub InfoNo ratings yet

- 4.manaa Saif Alhabsi - 35-45Document12 pages4.manaa Saif Alhabsi - 35-45iisteNo ratings yet

- NARRATIVEDocument4 pagesNARRATIVEjun rey tingcangNo ratings yet

- 219 PDFDocument6 pages219 PDFMostafa ShamsuzzamanNo ratings yet

- Factors Affecting Profitability of Fish Farming Under Economic Stimulus Programme in Tigania East District, Meru County, KenyaDocument13 pagesFactors Affecting Profitability of Fish Farming Under Economic Stimulus Programme in Tigania East District, Meru County, KenyaBienvenu KakpoNo ratings yet

- Strategic Management Determinants of Value Addition in The Sea Food Processing Sub-Chain: A Survey of Industrial Fish Processors in KenyaDocument10 pagesStrategic Management Determinants of Value Addition in The Sea Food Processing Sub-Chain: A Survey of Industrial Fish Processors in KenyashakilaNo ratings yet

- Recreational Fishing On The Coastal Hot Spots of İzmir Inner Bay (Aegean Sea, Turkey)Document24 pagesRecreational Fishing On The Coastal Hot Spots of İzmir Inner Bay (Aegean Sea, Turkey)Kristina Noëlle TijanNo ratings yet

- FISH CultureDocument7 pagesFISH CultureRonnie WartNo ratings yet

- 2010 Gulf California Biodiversity & Conservation Chapter6Document17 pages2010 Gulf California Biodiversity & Conservation Chapter6AbbyPañolaNo ratings yet

- Marine Fisheries in Indian Economy: R. SathiadhasDocument10 pagesMarine Fisheries in Indian Economy: R. SathiadhasSeilanAnbuNo ratings yet

- Jepang 1Document10 pagesJepang 1batagorenakNo ratings yet

- VN Fisheries Report FinalDocument141 pagesVN Fisheries Report FinalAquaquestNo ratings yet

- 958c PDFDocument12 pages958c PDFEd ZNo ratings yet

- Fish and Fish Products Marketing: Facets, Faultlines and FutureDocument15 pagesFish and Fish Products Marketing: Facets, Faultlines and FutureDr. M.KRISHNAN100% (21)

- Economic Viability of Cat Fish Production in Oyo State, NigeriaDocument5 pagesEconomic Viability of Cat Fish Production in Oyo State, NigeriaFakhri KurniawanNo ratings yet

- Article1405614692 - Issa Et AlDocument7 pagesArticle1405614692 - Issa Et Aloladipupo dacubaNo ratings yet

- Today's Fishing CommunityDocument11 pagesToday's Fishing Communityperojhy9tuoasefnpewNo ratings yet

- Fishing Condition and Fishers Income: The Case of Lake Tana, EthiopiaDocument4 pagesFishing Condition and Fishers Income: The Case of Lake Tana, EthiopiaPeertechz Publications Inc.No ratings yet

- Assessment of Commercial FishesDocument17 pagesAssessment of Commercial Fishesrichie espallardoNo ratings yet

- Analysis of Socio-Economic Factors Affecting Fish Marketing in Igbokoda Fish Market, Ondo State, NigeriaDocument10 pagesAnalysis of Socio-Economic Factors Affecting Fish Marketing in Igbokoda Fish Market, Ondo State, NigeriaIJEAB JournalNo ratings yet

- Sea Fish PackagingDocument11 pagesSea Fish Packagingeinestinerobin2No ratings yet

- An Economic & Sectoral Study of The South African Fishing Industry - Fisheries Profiles - ESS Vol 2 - Fishery Profiles CapeDocument312 pagesAn Economic & Sectoral Study of The South African Fishing Industry - Fisheries Profiles - ESS Vol 2 - Fishery Profiles CapeLibs222100% (1)

- FAO Fisheries & Aquaculture - Fishery and Aquaculture Country ProfilesDocument20 pagesFAO Fisheries & Aquaculture - Fishery and Aquaculture Country Profilesmiskoerik92No ratings yet

- AquacultureDocument12 pagesAquacultureMikeNo ratings yet

- The Mogadishu Fish Market During Inclement, Seasonal Weather - Function and Problems Constraining Benefits To The Local CommunityDocument9 pagesThe Mogadishu Fish Market During Inclement, Seasonal Weather - Function and Problems Constraining Benefits To The Local CommunityIfrah AdenNo ratings yet

- Project Report On FisheryDocument11 pagesProject Report On FisheryRam PimpalkhuteNo ratings yet

- The Dry Fish Industry of Sri LankaDocument75 pagesThe Dry Fish Industry of Sri Lankaktissera90% (10)

- Aquaculture Policy Brief #1 PDFDocument5 pagesAquaculture Policy Brief #1 PDFliftfund100% (1)

- Pidsdps 9901Document88 pagesPidsdps 9901Justin PaoloNo ratings yet

- P185-Pertiwi Et AlDocument5 pagesP185-Pertiwi Et AlSetyo PertiwiNo ratings yet

- Country Profile Thailand 03 2013Document5 pagesCountry Profile Thailand 03 2013George AtaherNo ratings yet

- 1 s20 S2590291123001961 Main - 230609 - 193935Document10 pages1 s20 S2590291123001961 Main - 230609 - 193935Samuel Ayeh OseiNo ratings yet

- Profitability Analysis of Small-Scale Catfish Farming in Kaduna State, NigeriaDocument7 pagesProfitability Analysis of Small-Scale Catfish Farming in Kaduna State, Nigeriadevika11No ratings yet

- Aquaculture PhilippinesDocument29 pagesAquaculture PhilippinesJesi ViloriaNo ratings yet

- OvieDocument20 pagesOvieEMMANUEL SALVATIONNo ratings yet

- An Overview of Fiji FisheriesDocument7 pagesAn Overview of Fiji Fisherieslordbrian12No ratings yet

- Marketing and Distribution Channel of Processed Fish in Adamawa State, NigeriaDocument7 pagesMarketing and Distribution Channel of Processed Fish in Adamawa State, NigeriadayiniNo ratings yet

- Fisheries Profile 2005Document67 pagesFisheries Profile 2005MariaCruzNo ratings yet

- Nara41 087Document16 pagesNara41 087THARINDUNo ratings yet

- Title - Fisheries College & Research InstituteDocument8 pagesTitle - Fisheries College & Research InstituteTania TuscanoNo ratings yet

- EJABF - Volume 25 - Issue 2 - Pages 561-572 CadanganDocument12 pagesEJABF - Volume 25 - Issue 2 - Pages 561-572 Cadanganrahma apriantyNo ratings yet

- The Sector Situation of Marine Fisheries in The Member States in The Context of Covid-19Document18 pagesThe Sector Situation of Marine Fisheries in The Member States in The Context of Covid-19Olympe AmagbegnonNo ratings yet

- 2091 3547 1 PBDocument12 pages2091 3547 1 PBnur fadilahNo ratings yet

- Aqua Analyse Profitability NigeriaDocument7 pagesAqua Analyse Profitability NigeriaBienvenu KakpoNo ratings yet

- Conservation and Management of Tuna Fisheries in The Indian Ocean and Indian EEZDocument6 pagesConservation and Management of Tuna Fisheries in The Indian Ocean and Indian EEZFrontiersNo ratings yet

- Value Chain of Fish Langano 2019Document11 pagesValue Chain of Fish Langano 2019Addis HailuNo ratings yet

- FisheriesDocument32 pagesFisheriesgive printNo ratings yet

- Resilience in Fisheries and Sustainability of Aquaculture - India - 8IFF (1) .Souvenir 2008Document9 pagesResilience in Fisheries and Sustainability of Aquaculture - India - 8IFF (1) .Souvenir 2008A GopalakrishnanNo ratings yet

- Contribution of Fish Production and Trade To The Economy of PakistanDocument7 pagesContribution of Fish Production and Trade To The Economy of PakistanYousaf JamalNo ratings yet

- Chapter 6 SocioDocument9 pagesChapter 6 SocioChristineNo ratings yet

- Thai Longline - NootmornDocument10 pagesThai Longline - Nootmornbudi073No ratings yet

- The Fisheries Modernization Code of 1998Document52 pagesThe Fisheries Modernization Code of 1998Leslie CampoletNo ratings yet

- Afif Fahza Nurmalik - 1754221004Document3 pagesAfif Fahza Nurmalik - 1754221004Afif Fahza NurmalikNo ratings yet

- Nunoo Et Al 2015 - JENRMDocument10 pagesNunoo Et Al 2015 - JENRMgracellia89No ratings yet

- Hakes: Biology and ExploitationFrom EverandHakes: Biology and ExploitationHugo ArancibiaNo ratings yet

- Gina Lopez - Acero, Mae TrixieDocument4 pagesGina Lopez - Acero, Mae Trixieann gabrielleNo ratings yet

- Fishes in Terengganu PDFDocument261 pagesFishes in Terengganu PDFNor Ahmad Shabaruzaman IINo ratings yet

- Performing Nursery OperationsDocument38 pagesPerforming Nursery OperationsCristine S. DayaoNo ratings yet

- Basic Elements, Nature, Scope and Limitation of Environmental LawDocument10 pagesBasic Elements, Nature, Scope and Limitation of Environmental LawRam C. Humagain100% (2)

- English Compulsory (Intermediate Classes) Exercises (English Book-I (Short Stories) )Document15 pagesEnglish Compulsory (Intermediate Classes) Exercises (English Book-I (Short Stories) )Attique ZaheerNo ratings yet

- Northern Samar June 2018Document4 pagesNorthern Samar June 2018Romeo RiveraNo ratings yet

- Nabard Gpat Farming Project Report PDF FileDocument12 pagesNabard Gpat Farming Project Report PDF FileAjai chagantiNo ratings yet

- Bambang HistoryDocument16 pagesBambang HistoryJeremiah Nayosan75% (4)

- Final Report On Asia ContinentDocument85 pagesFinal Report On Asia ContinentAbhishek TyagiNo ratings yet

- en GoDocument190 pagesen GoJoseph SepulvedaNo ratings yet

- Executive Summary Fish MarketingDocument3 pagesExecutive Summary Fish MarketingBrentgreg DaumogNo ratings yet

- Carp Culture and ProductionDocument3 pagesCarp Culture and ProductionJessielito P. AmadorNo ratings yet

- Esperanza Renace AP Summer Reading Assignment 2015Document31 pagesEsperanza Renace AP Summer Reading Assignment 2015Gina Cabezas Carvajal100% (1)

- Bab 1 - Preparation Raw Material Part BDocument33 pagesBab 1 - Preparation Raw Material Part BAzwin Ahmad67% (6)

- Ethiopian IssueDocument76 pagesEthiopian Issuetufabekele100% (1)

- GMO STS GuevarraDocument4 pagesGMO STS GuevarraGuevarra KeithNo ratings yet

- A Guide To Colostrum and Colostrum Management For Dairy CalvesDocument5 pagesA Guide To Colostrum and Colostrum Management For Dairy CalvesAlessio BoccoNo ratings yet

- HydrologyDocument4 pagesHydrologyمهندس ابينNo ratings yet

- Seed Technology: Principles ofDocument20 pagesSeed Technology: Principles ofDivyaNo ratings yet

- L4. LO2. Safekeep Dispose Tools, Materials and OutfitDocument77 pagesL4. LO2. Safekeep Dispose Tools, Materials and OutfitGiedon Quiros73% (15)

- Region Xi - Davao CityDocument6 pagesRegion Xi - Davao CityZiyi WuNo ratings yet

- Feasibility Study On The Seaweed Kappaphycus Alvarezii Cultivation Site in Indari Waters ofDocument9 pagesFeasibility Study On The Seaweed Kappaphycus Alvarezii Cultivation Site in Indari Waters ofUsman MadubunNo ratings yet

- Middle Holiday Package - 2022Document29 pagesMiddle Holiday Package - 2022Naki Winfred MaryNo ratings yet

- Mind MappingDocument2 pagesMind MappingChristian MuliNo ratings yet

- Alangalang National High School - Pre Test in Tle 7Document4 pagesAlangalang National High School - Pre Test in Tle 7Liwayway MacatimpagNo ratings yet

- Trimmer PartsDocument29 pagesTrimmer PartsHAVENSALNo ratings yet