Professional Documents

Culture Documents

The Intersection of Narrative Policy Analysis and Policy Change Theory - Mark K. McBeth, Elizabeth A. Shanahan, Ruth J. Arnell, and Paul L. Hathaway

The Intersection of Narrative Policy Analysis and Policy Change Theory - Mark K. McBeth, Elizabeth A. Shanahan, Ruth J. Arnell, and Paul L. Hathaway

Uploaded by

sepehr_asapCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

The Intersection of Narrative Policy Analysis and Policy Change Theory - Mark K. McBeth, Elizabeth A. Shanahan, Ruth J. Arnell, and Paul L. Hathaway

The Intersection of Narrative Policy Analysis and Policy Change Theory - Mark K. McBeth, Elizabeth A. Shanahan, Ruth J. Arnell, and Paul L. Hathaway

Uploaded by

sepehr_asapCopyright:

Available Formats

The Policy Studies Journal, Vol. 35, No.

1, 2007

The Intersection of Narrative Policy Analysis and Policy

Change Theory

Mark K. McBeth, Elizabeth A. Shanahan, Ruth J. Arnell, and Paul L. Hathaway

Narrative policy analysis and policy change theory rarely intersect in the literature. This research

proposes an integration of these approaches through an empirical analysis of the narrative political

strategies of two interest groups involved in policy debate and change over an eight-year period in the

Greater Yellowstone Area. Three research questions are explored: (i) Is it possible to reconcile these

seemingly disparate approaches? (ii) Do policy narrative strategies explain how interest groups expand

or contain policy issues despite divergent core policy beliefs? (3) How does this new method of analysis

add to the literature? One hundred and ve documents from the Greater Yellowstone Coalition and the

Blue Ribbon Coalition were content analyzed for policy narrative strategies: identication of winners

and losers, diffusion or concentration of costs and benets, and use of condensation symbols, policy

surrogates, and science. Five of seven hypotheses were conrmed while controlling for presidential

administration and technical expertise. The results indicate that interest groups do use distinctive

narrative strategies in the turbulent policy environment.

KEY WORDS: Advocacy Coalition Framework, Greater Yellowstone Area, interest groups, narrative

policy analysis, policy change

Introduction

Researchers in the eld of public policy theory seek to explain the divergent

characteristics of policy change, namely equilibrium and radical change. Why does

the public undergo alterations in how they understand policy problems and why do

policy issues that remain static for many years suddenly become dynamic? Three

theories have dominated the literature over the past decade: Kingdons (1995)

policy streams, Baumgartner and Jones (1993) punctuated equilibrium, and

Advocacy Coalition Framework (ACF). These authors individually seek to build a

theory of policy change that stands up to the rigor of empirical analyses. In this

study, we posit a methodological innovation in the area of policy change by introducing an integration of narrative policy analysis (NPA) into the traditional policy

change theory. This integration is accomplished through a systematic study of the

strategic nature of policy narratives. The results help to further explain policy change

and the role that various groups play in prompting policy change or maintenance of

the status quo.

87

0190-292X 2007 The Policy Studies Journal

Published by Blackwell Publishing. Inc., 350 Main Street, Malden, MA 02148, USA, and 9600 Garsington Road, Oxford, OX4 2DQ.

88

Policy Studies Journal, 35:1

During the last two decades, the work of social constructionists in the eld of

NPA (e.g., Fischer & Forrester, 1993; Roe, 1994; Stone, 2002) has developed concurrently with that of policy change theorists. NPA focuses on the centrality of narratives in understanding policy issues, problems, and denitions and does so without

the grand theoretical aspirations of the more traditional policy change works. One of

the most developed works in the narrative genre is that of Deborah Stone (2002),

whose Policy Paradox is an NPA gold mine of mini-theories about agenda setting,

issue and problem denition, and policy dynamics. The centerpiece of Stones work

is the use of literary devices such as characters, plots, colorful language, and metaphors to analyze policy narratives. In particular, the storytellers political tactics are

revealed in how they construct who wins and who loses in a policy story (or who

reaps the benets and pays the costs), how they characterize policy issues and their

opposition, and how they either entangle policies in larger cultural issues or alternatively try to ground such issues in the certainty of scientically deduced numbers

and facts. Ultimately, Stone (p. 229) asserts that the goal of this strategic problem

denition is to portray a political problem so that ones favored course of action

appears to be in the broadest public interest.

With some exceptions (Baumgartner, 1989; Baumgartner & Jones, 1993, pp. 279;

Hajer, 1993; Radaelli, 1999; Schneider & Ingram, 2005), NPA and the policy change

literature rarely intersect. The exclusion of narratives from the grand theories of

policy change is grounded in the belief that narratives are value-based random

garble. Sabatier (2000, p. 138), for example, argues that constructivists have demonstrated very little concern with being sufciently clear to be proven wrong and

that their lack of clarity leads him to have no interest in popularizing their position. We argue that narratives are the lifeblood of politics. Narratives are both the

visible outcome of differences in policy beliefs (McBeth, Shanahan, & Jones, 2005)

and the equally visible outcome of political strategizing. Both policy beliefs and

political strategies, as found in policy narratives, are not random occurrences. Policy

beliefs are arguably stable, and political strategies are predictable.

NPA and Policy Change Theory

Sabatier and Jenkins-Smith (1993, p. 16) outline premises for their ACF, for

which we assert that narrative theory can serve a methodological role. First, they

claim that policy change must be analyzed over time, a decade or longer; narratives

are written words that can easily be documented and tracked through a temporal

perspective. Second, they purport that policy change can be understood through the

examination of political subsystems (advocacy coalitions) that seek to inuence

governmental decisions. Other research (McBeth et al., 2005) has discovered that the

narratives generated by political subsystems in the polity at large, not just in the

legislative arena, also contain stable core policy beliefs and are a legitimate source of

policy change analysis.

The work of Baumgartner and Jones (1993) is also essential for a study of

narratives and policy change. They point out that, at any particular time, an interest

group is part of a winning policy monopoly or they are part of an out-of-power

McBeth et al: Narrative Policy Analysis and Policy Change Theory Intersection

89

minority coalition. However, with wicked problems (Rittel & Webber, 1973),

where rationality and science are minimized in importance, winning and losing

is more of a perception than necessarily a reality. Wicked problems resist resolution by appeal to the facts (Schon & Rein, 1994, p. 4) and beliefs are grounded in

competing cultural norms (Wood & Doan, 2003, p. 641). Jenkins-Smith and Sabatier

(1993, p. 49) furthermore assert that when core beliefs are at stake, competing sides

will defend their own belief systems and attack the belief systems of the opposition.

Yet, as later hypothesized by Sabatier and Jenkins-Smith (1999, p. 124), through the

development of technical expertise, coalitions move toward policy learning. Because

of the intense value-based conict between competing groups, policy narratives are

an important element of study for wicked problems and add to the ability of more

traditional policy change theories to understand the strategic representation of

values in framing the conict.

Interest groups attempt to maintain, demonstrate, and increase their political

power as they seek to win a favorable policy. Furthermore, whether an interest group

perceives themselves as winning or losing on a policy issue greatly inuences how

they play politics. According to Schattschneider (1960, p. 16), winning groups try to

restrict participation (issue containment) in a policy issue by limiting the scope of

the conict whereas losing groups try to widen participation (issue expansion) in

a policy issue. Such a conclusion is reinforced in a wide variety of literature (e.g.,

Baumgartner, 1989; Cobb & Elder, 1983; Baumgartner & Jones, 1993). While Radaelli

(1999, p. 674) concludes that narratives are understood within broader political

dynamics, the unanswered questions are how do the policy narratives of interest

groups play into the equation of issue containment and issue expansion in wicked

policy problems and how do these narratives play into the role of policy change (or

lack of change, thus contributing to policy intractability)? Our methodology,

drawing on the insights of NPA, Baumgartner, Jones, Sabatier and Jenkins-Smith,

allows us to answer these questions.

Primary Beliefs and Political Strategies

We assert that interest group narratives possess both primary beliefs and political strategies. This differs slightly from Sabatier and Jenkins-Smiths (1999, p. 122)

view of policy beliefs. They contend that policy beliefs are composed of core beliefs

that remain stable and secondary beliefs that are more susceptible to change. The

same principle of core beliefs and secondary beliefs can be applied to the study of

policy narratives. When we read a policy narrative regarding an environmental

issue, part of the narrative consists of underlying beliefs in such issues as federalism,

science, and the relationship between humans and nature. These are primary policy

beliefs held by interest groups, and narratives reveal that they tend to be stable over

time (McBeth et al., 2005).

We argue that narratives also possess political strategies and that these elements

are much more dynamic. In contrast to Sabatier and Jenkins-Smith (1993: 3031),

who dene secondary beliefs as instrumental decisions of policy implementation, we

assert that in a policy narrative, the secondary political strategies (not necessarily

90

Policy Studies Journal, 35:1

beliefs) include rhetorical devices outlined by Deborah Stone (2002), among others.

Political strategies are an important and perhaps underdeveloped element of the

ACF. As Brown and Stewart (1993, p. 101) argue, the study of policy change must

focus on tactics employed by policy advocates. As found in narratives, these tactics

or strategies shift depending on whether or not the coalition perceives itself as

winning. Competing policy narratives incorporate strategies such as identication of

winners and losers, framing who benets and who sustains costs in the policy

conict, the use of condensation symbols, the wrapping of issues in larger policy

surrogates, and the use of scientic uncertainty. In turn, the choice of narrative

strategy is driven by the groups perception of whether it is winning or losing on the

policy issue. The analysis of both primary beliefs as dened by Sabatier and JenkinsSmith (1999, p. 122) and political strategies (as informed by Stone) is an unexplored

area in which the two elds intersect and strengthen each other. While traditional

policy change theory can show that groups act strategically, our methodology draws

on NPA to show how groups act strategically through narratives.

Political Narrative Strategies

Five narrative strategies are dened in the succeeding discussion. These political

strategies are hypothesized to contain the issue if the group is winning or to expand

the issue if the group is losing.

1. Identifying Winners and Losers. As part of issue containment and expansion, interest groups will strategically include or exclude mention of specic winners and

losers. Interest groups that perceive themselves as winning on a policy issue are

more likely to identify specic winners in their policy narratives, whereas interest

groups that perceive that they are losing on a policy issue are more likely to identify

specic losers. Winning strategies attempt to contain the issue by illustrating that

the status quo is positive and no change is necessary. In Baumgartner and Joness

(1993) terminology, these groups attempt to preserve the current image of a policy

problem simply because this policy frame has helped to achieve the status of a policy

monopoly. The goal is to maintain a minimum winning coalition (Riker, 1962);

expanding the coalition would necessarily entail compromises in policy beliefs and

outcomes, which, in turn, weakens the power of the members of the policy

monopoly. On the other hand, losing groups identify losers in the policy conict in

the hope of mobilizing opposition in order to change the status quo. Stone (2002,

p. 228) argues that both sides try to amass the most power and that it is the loser

who seeks to bring in outside help.

2. Construction of Benets and Costs. Baumgartner and Jones (1993, p. 19) contend

that losing groups seek to redene issues in ways that will mobilize indifferent

citizens and groups in the hope that this mobilization will destabilize policy equilibrium. This expansion of an issue to heightened general attention is pivotal in

policy change (Jones & Baumgartner, 1993, p. 20). In terms of narrative theory, when

a competing interest group is losing, they use their policy narratives to attempt to

McBeth et al: Narrative Policy Analysis and Policy Change Theory Intersection

91

reallocate attention and expand the issue by diffusing costs and concentrating benets. This strategy makes it appear that only a few (if any) groups are beneting from

the status quo while many groups are paying the costs. This tactic attempts to

mobilize the public and bring new players into a coalition. Conversely, when a group

is winning, they are much more likely to contain the issue by diffusing benets and

concentrating costs on a small group. This narrative strategy seeks to maintain the

status quo and to restrict a wide-scale mobilization.

3. The Use of Condensation Symbols. Jones and Baumgartner (1993, p. 26) argue that

every public policy problem is usually understood, even by the politically sophisticated, in simplied and symbolic terms. Stone (2002, p. 137) asserts more directly

that symbolic representation is the essence of problem denition in politics. Thus,

we can hypothesize that interest groups that are winning or losing on a policy issue

will use condensation symbols or a language that reduce[s] complicated concepts

into simple, manageable, or memorable forms (Achter, 2004, p. 315). Interest groups

will use condensation symbols to dene the policy issue and to characterize their

opponents. We argue that winning groups have fewer incentives to use condensation

symbols because doing so might invoke unintended consequences such as riling of

the opposition. Losing groups, however, have tremendous incentives to negatively

portray both the issue and their opponents through the use of condensation symbols.

Again, their goal is to both rally their troops and call in additional reinforcements by

expanding the scope of the conict.

4. The Policy Surrogate. In his discussion of the many causes of wicked resourcebased policy conict, Nie (2003) suggests that a key cause of conict is the policy

surrogate. Nie (p. 314) argues that relatively straightforward policy problems can

be turned wicked when they are used by political actors as a surrogate to debate

larger and more controversial problems. For environmental policy issues in the

Western United States, this means that issues like bison management and snowmobile access are wrapped in larger persistent controversies of Western communities:

concerns about federalism, the role of public lands, and the fear of outsiders, to name

a few. Our argument is that losing groups strategically entangle policy issues in

larger, emotionally charged debates in an effort to gain a competitive advantage by

expanding the scope of the policy issue. In short, these policy surrogates are used to

ignite the larger controversies already simmering in the political culture and to

mobilize opposition.

5. Scientic Certainty and Disagreement. Nie (2003, p. 323) argues that scientic disagreement is also a major cause of intractable natural resource-based political conict. Furthermore, Nie (p. 323) notes that environmental policies have increasingly

become disputes over science and concludes that political actors frame value and

interest based political conict as scientic ones and that they escape responsibility for making the tough choices required of them. Thus, this driver, contradictory

to the policy surrogate driver, suggests that policy actors intentionally reduce the

scope of policy issues, ignoring the larger normative and cultural issues that invari-

92

Policy Studies Journal, 35:1

ably surround resource-based environmental conict. We argue that groups that are

winning in a policy issue are likely to dene the issue in terms of scientic certainty,

thus ignoring the larger normative issues involved in the controversy. Such a certainty attempts to bring closure to debates surrounding policy issues, maintains the

status quo and the minimum winning coalition, and simultaneously hopes to demobilize the opposition. Conversely, losing groups attack scientic results and present

a scientic disagreement in an attempt to open up the issue for a continued

deliberation.

Research Questions

This study addresses three research questions. First, we attempt to methodologically demonstrate the useful intersection of NPA and policy change theory. Can such

ontologically opposing theories be legitimately brought together in the study of

policy change? Second, we operationalize NPA into measurable tools to examine how

groups expand or contain policy issues, not just that they do. Do policy narrative

strategies of interest groups explain how these groups expand or contain policy

issues despite divergent core policy beliefs? Third, how does this new method of

analysis add to the existing literature on policy change?

The Case Study

The systematic analysis of different interest groups narrative political strategies

is conducted as a case study in the turbulent policy arena of the Greater Yellowstone

Area (GYA). The 19 million acres of the GYA, with Yellowstone National Park (YNP)

comprising 2.2 million acres of the region, are not only a world famous area for

geysers, wildlife, and scenic wonders but a well documented hotbed of political

conict (e.g., Cawley & Freemuth, 1993; Tierney & Frasure, 1998; Wilson, 1997). In

fact, environmental policymaking in the region is often intractable or wicked (Rittel

& Webber, 1973). To use the terminology of Jenkins-Smith and Sabatier (1993, p. 49),

the conict is intense and highly political since core policy beliefs (e.g., federalism,

the relationship between humans and nature, science) are disputed and competing

sides ground their arguments in myth (Tierney & Frasure, 1998).

Environmental groups and scientists have sought to redene Yellowstones

image from that of an isolated national park with denitive boundaries to that of the

only intact ecosystem left in the continental United States (Clark & Minta, 1994). To

use the theory of Baumgartner and Jones (1993), environmental groups have sought

to redene the image of the area from Yellowstone as zoo to Yellowstone as an

open ecological system. Such an effort at image redenition has intensied the

political conict in the past decade. Two interest groups have dominated efforts by

competing advocacy coalitions to dene the policy images of GYA. The Blue Ribbon

Coalition (BRC) represents motorized recreation users (wise use coalition) and is

based in Pocatello, Idaho.1 The Greater Yellowstone Coalition (GYC), based in

Bozeman, Montana, represents the environmental coalition.2 These two groups are

purposive interest groups, for those who join pursue ideological and issue-

McBeth et al: Narrative Policy Analysis and Policy Change Theory Intersection

93

oriented goals without material rewards (Berry, 1989, p. 47). This is important given

the Sabatier and Jenkins-Smith (1999, p. 134) hypothesis that purposive groups are

more constrained in their willingness to compromise beliefs and policy positions.

From 1997 through 2004, the politics of the GYA have been characterized by

continuous changes in public policy, instability, and policy wickedness. Policy

monopolies have collapsed for short periods of time only to nd resurgence and an

ability to regain political power. During the years of the Clinton administration,

environmental groups pushed large policy initiatives into effect. The policy issues

that demonstrated newfound environmental power in the GYA included wolf reintroduction in 1995, regulations that ended snowmobiling inside YNP in 2000, and a

national roadless initiative in national forests in 1999.

There is one exception to the wave of Clinton GYA environmental policy success,

where the wise use coalition retained their monopoly: the management of freeranging bison. In the winter of 199697, over 1,100 bison were killed by the Montana

State Livestock Department with assistance from the National Park Service because

of concern over the potential role of bison in brucellosis transmission to cattle. Efforts

by the Clinton administration and environmentalists to end the killing failed as a

powerful subsystem of ranchers, federal and state elected ofcials, and the U.S.

Department of Agriculture Animal, Plant, Health, Inspection Services retained its

historic hegemonic stance.

Yet again, with the exception of the bison controversy, the policy changes in the

1990s were overwhelmingly in the direction of the GYA environmental advocacy

coalition. The election of George W. Bush in 2000, however, led to a large-scale

resurgence of the wise use coalition in at least two policy areas. Bushs rst term saw

the dramatic reversal of the Clinton era snowmobile ban in YNP. The presidents

second term saw the overturning of the roadless rule in favor of state control over the

use of national forests. It is in the context of this turbulent policy arena from 1997

through 2004 that the BRC and the GYC both generated strategic political narratives.

Research Methodology

A content analysis was performed on one hundred ve documents produced by

the GYC (52 documents) and the BRC (53 documents) over eight years (January 1,

1997 through December 31, 2004). The documents address one of three policy issues

in the GYA: (i) bison and brucellosis (14 documents); (ii) snowmobile access in YNP

(70 documents); and (iii) the roadless initiative (21 documents). Our choice of content

analysis was straightforward. Content analysis is unobtrusive, allows for a reliability

analysis, permits a longitudinal analysis, and is efcient and inexpensive. The documents analyzed were readily archived and complete, thereby avoiding some of the

disadvantages of using content analysis (Johnson & Reynolds, 2005, pp. 23234).

Based on NPA and policy change theory, we propose seven hypotheses predicting

an association between use of a winning or losing narrative frame (independent

variable, see Table 1) and seven different narrative political strategies (dependent

variables, see Table 1).

94

Policy Studies Journal, 35:1

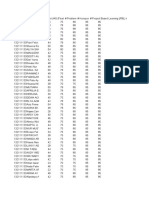

Table 1. Operationalization of Dependent, Independent, and Control Variables

Denition

Identify a winner of policy objective

0 = none identied (no); 1 = winner (yes)

Identify a loser of policy objective

0 = none identied (no); 1 = loser (yes)

Concentrate or diffuse benets of policy objective

0 = concentrated; 1 = diffused

Concentrate or diffuse costs of policy objective

0 = concentrated; 1 = diffused

Reduces issue into loaded, dichotomous symbol

0 = no use; 1 = used condensation symbol

Wraps a specic issue in larger normative issues

0 = no use; 1 = used policy surrogate

Use of scientic certainty or disagreement

0 = scientic certainty; 1 = scientic disagreement

105

Variables

Dependent Variables

Identication of winner

Identication of loser

Benets

Costs

Condensation symbol

Policy surrogate

Science

Independent Variable

Winninglosing

Control Variables

Presidential administration

Use of science

105

61

85

105

105

54

The narrative frame regarding policy objective

0 = losing; 1 = winning

105

President at the time the narrative was written

0 = Clinton; 1 = Bush

Whether the narrative used science or not

0 = no science used; 1 = used science

105

105

Source: Greater Yellowstone Coalition and Blue Ribbon Coalition documents, 19972004.

Hypotheses

For the following seven alternative hypotheses, each has a null hypothesis that

asserts no association between winning or losing policy narrative frames and the

attending narrative political strategy. Because these are nominal-level variables, no

direction is predicted.

Hypothesis 1a: There is an association between winning policy narrative frames

and identication of winners in the narrative.

Hypothesis 1b: There is an association between losing policy narrative frames and

identication of losers in the narrative.

Hypothesis 2: There is an association between winning policy narrative frames and

the diffusion of benets in the narrative; similarly, there is an association between

losing policy narrative frames and concentration of benets in the narrative.3

Hypothesis 3: There is an association between winning policy narrative frames and

the concentration of costs in the narrative; similarly, there is an association between

losing policy narrative frames and diffusion of costs in the narrative.

Hypothesis 4: There is an association between losing policy narrative frames and

use of condensation symbols.

McBeth et al: Narrative Policy Analysis and Policy Change Theory Intersection

95

Hypothesis 5: There is an association between losing policy narrative frames and

use of policy surrogates.

Hypothesis 6: There is an association between winning policy narrative frames and

the use of scientic certainty in the narrative; similarly, there is an association

between losing policy narrative frames and the use of scientic uncertainty in the

narrative.

Dependent Variables

Temporally, whether the policy narrative is winning or losing precedes the

political strategies used; thus, the dependent variables in this study are the political

strategies (see Table 1). Using content analysis, a series of questions was developed

to operationalize the dependent variables for the seven hypotheses (see Appendix A,

questions 18 on the codebook).

Independent Variable

Whether a policy narrative is winning or losing explains what political strategies

are employed. The problem of how to operationalize whether an interest group was

winning or losing invoked much discussion among research team members. At one

point, an objective measure was going to be utilized. In other words, based on

executive, judicial, and administrative decisions, the interest group would be determined to be winning or not. Interestingly, this proved difcult because of the volatility of Yellowstone policy issues during the time period under study. No interest

group could be said to enjoy a true policy monopoly throughout the period (the

bison issue is the most likely exception) because governmental decisions on these

issues rarely achieved a permanent or stable status. Thus, the team decided that what

was important in narrative terms was not objective winning or losing, but rather the

perceptions of the interest group on whether they were winning on an issue (the

group supported the status quo) or losing (the group felt that they were under attack

in the policy environment). Question 9 of the code book in Appendix A measures

this perception of winning and losing.

Control Variables

ACF controls of coalitional resources (i.e., presidential administration) and coalitional policy learning (i.e., whether or not scientic evidence was used) were used.

The ACF theory asserts that over time, policy change is, in part, a function of

changing governing coalitions (affecting coalitional resources) and coalitional technical expertise (impacting policy learning). To better assess the relationship between

political strategies and winninglosing narrative frames, each Chi-square test (in

succeeding discussions) was subsequently controlled for presidential administration

and whether or not the narrative used science.

96

Policy Studies Journal, 35:1

The content analysis was conducted by three coders. Ten documents were pretested using an initial codebook. The documents were coded independently by the

coders who then met periodically after coding every 2535 documents. At their

meetings, the coders discussed their results, redened and narrowed rules, and

ultimately reconciled their disagreements. The reliability of the three coders was

evaluated by comparing them in three pairs on their coding of all questions. The

reliability ratings range from a low of 78 percent to a high of 93 percent, with an

average of agreeing 84 percent of the time (see Appendix B), thus reasonably establishing intercoder reliability.

Given that the narrative strategies were operationalized as nominal-level variables, a Chi-square test of signicance was conducted for each hypothesis to investigate the statistical difference between the occurrence of narrative frame

(winninglosing) and that of political narrative strategy or if the strategies utilized

are attributed to chance alone. A continuity correction was applied with the occurrence of small cells (n 5); a Fishers Exact Test was used to determine the statistical signicance (Ramsey & Schafer, 1997, pp. 54751). The magnitude of the

Chi-square results was assessed with a Cramrs V, the preferred Chi-square

measure of association (McClendon, 2004, p. 455). Odds ratios (ORs) were calculated as a cross-product ratio (Knoke, Bohrnstedt, & Mee, 2002, p. 161) and were

used to indicate the odds of a specic political strategy occurring with a winning

or losing narrative.

Research Results

Table 2 provides descriptive statistics of the one hundred ve narratives coded.

Note that of the winning and losing narratives, 71 of the 105 documents (68 percent)

were coded as losing narratives, whereas only 34 (32 percent) were coded as

winning. There are at least two reasons for this. First, groups may well be more likely

to articulate and distribute a policy narrative when they are losing as their goal is to

change the status quo, and their narrative is a form of both political defense and

attack. Second, as discussed earlier, there were no clear policy monopolies in this

time period. Instead, both interest groups experienced back-and-forth short-term

wins and losses characteristic of wicked problems. Thus, both interest groups felt

under attack consistently from nonfriendly forces. This is evidenced by the fact that

both groups produced more losing policy narratives than winning across all three

policy issues regardless of presidential administration.

Hypotheses 1a and b: Identication of Winners and Losers

Table 3 indicates statistically signicant associations between winning narrative

frames and the identication of a specic winner (c2[d.f. = 1] = 13.049, p < 0.001) and

losing narrative frames and identication of a specic loser (c2[d.f. = 1] = 23.134,

p < 0.001). In winning narrative frames, a specic winner was identied 82.4 percent

of the time (fo = 28; fe = 19.4), compared with that of losing narrative frames identifying a winner 45.1 percent of the time (fo = 32; fe = 40.6). The odds ratio of a winning

McBeth et al: Narrative Policy Analysis and Policy Change Theory Intersection

97

Table 2. Descriptive Statistics of Interest Group Narratives by Winning or Losing Frame, Policy Issue,

and Presidential Administration

Interest

Group

GYC

BRC

Total

Total

Documents

Winning

Narratives

Losing

Narratives

Policy Issue

52 (100%)

14 (27%)

38 (73%)

Bison

Winning

3 (30%)

Losing

7 (70%)

Total

10 (100%)

Snowmobiles

Winning

7 (22%)

Losing

25 (78%)

Total

32 (100%)

Roadless

Winning

4 (40%)

Losing

6 (60%)

Total

10 (100%)

Bison

Winning

0 (0%)

Losing

4 (100%)

Total

4 (100%)

Snowmobiles

Winning 18 (47%)

Losing

20 (53%)

Total

38 (100%)

Roadless

Winning

2 (18%)

Losing

6 (82%)

Total

8 (100%)

53 (100%)

105 (100%)

20 (38%)

34 (32%)

33 (62%)

Presidential

Administration

Clinton

Winning

Losing

Total

Bush

Winning

Losing

Total

Clinton

Winning

Losing

Total

Bush

Winning

Losing

Total

4 (31%)

9 (69%)

13 (100%)

10 (26%)

29 (74%)

39 (100%)

6 (26%)

17 (74%)

23 (100%)

14 (47%)

16 (53%)

30 (100%)

71 (68%)

Source: GYC and BRC documents, 19972004.

GYC, Greater Yellowstone Coalition; BRC, Blue Ribbon Coalition.

Table 3. Chi-Square Results for Identication of Winners and Losers by Narrative Frame

Losing Narrative

Identication of winner

Identication of loser

Winning Narrative

Total

Yes

45.1%

82.4%

60

(32)

(28)

No

54.9%

17.6%

45

(39)

(6)

Total

100.0%

100.0%

105

(71)

(34)

c2(d.f. = 1) = 13.049, p < 0.001; Cramrs V = 0.353, p < 0.001; ORWW = 5.69

Yes

95.8%

58.8%

88

(68)

(20)

No

4.2%

41.2%

17

(3)

(14)

Total

100.0%

100.0%

105

(71)

(34)

c2(d.f. = 1) = 23.134, p < 0.001; Cramrs V = 0.469, p < 0.001; ORLL = 15.87

Source: Greater Yellowstone Coalition and Blue Ribbon Coalition documents, 19972004.

OR, odds ratio; ORWW, odds ratio of a winning frame; ORLL, odds ratio of a losing narrative frame.

98

Policy Studies Journal, 35:1

frame identifying a specic winner is 5.69; thus, winning policy narratives are ve

times more likely than losing narrative frames to identify a winner. Losing narrative

frames contained a specic loser 95.8 percent of the time (fo = 68; fe = 59.5), compared

with winning narrative frames identifying a loser 58.8 percent of the time (fo = 20;

fe = 28.5). The odds ratio of a losing narrative frame identifying a specic loser is

15.87; thus, losing narrative frames are fteen times more likely than winning frames

to identify a loser. The magnitude of these relationships is strong, with Cramrs

V = 0.353 (p < 0.001) and 0.469 (p < 0.001) for winning and losing policy frames,

respectively. We can accept hypotheses 1a and b.

The strategy of winning narratives is to maintain the status quo; the BRC often

cites local communities and small business owners as winners while the GYC cites

Yellowstone visitors. Interestingly, the BRC and the GYC see the maintenance of the

status quo in the hands of local vs. national constituencies, respectively. Yet their

strategy is keenly predictable here. Losing narratives identify losers in an attempt to

grow a coalition and change the status quo. The BRC invokes a wide coalition of

potential losers in trying to debunk what they view as environmental propaganda:

the public, visitors to YNP, snowmobile riders, and the snowmobile industry

(Eggers, 1999). Similarly, in arguing for snowmobile regulation, the GYC identies

wildlife, park employees, public safety, American families, and the taxpayer as losers

in the status quo of YNP snowmobile use (Catton & Bufngton, 2002). The political

strategy is the same despite divergent policy beliefs.

Hypothesis 2: Concentration or Diffusion of Benets

Table 4 also reveals a statistically signicant association between the occurrence

of concentration or diffusion of benets in policy narrative frames

(c2[d.f. = 1] = 6.959, p < 0.01), with an indication of a strong measure of association:

Cramrs V = 0.338 (p < 0.01). Losing narratives diffuse benets 18.2 percent of the

Table 4. Chi-Square Results for Benets and Costs by Narrative Frame

Losing Narrative

Benets

Costs

Winning Narrative

Concentrated benets

81.8%

50.0%

(27)

(14)

Diffuse benets

18.2%

50.0%

(6)

(14)

Total

100.0%

100.0%

(33)

(28)

c2(d.f. = 1) = 6.959, p < 0.01; Cramrs V = 0.338, p < 0.01; OR = 4.5

Concentrated costs

16.4%

55.6%

(11)

(10)

Diffuse costs

83.6%

44.4%

(56)

(8)

Total

100.0%

100.0%

(67)

(18)

c2(d.f. = 1) = 11.683, p < 0.001; Cramrs V = 0.371, p < 0.001; OR = 6.36

Source: Greater Yellowstone Coalition and Blue Ribbon Coalition documents, 19972004.

OR, odds ratio.

Total

41

20

61

21

64

85

McBeth et al: Narrative Policy Analysis and Policy Change Theory Intersection

99

time (fo = 6; fe = 10.8), compared with winning narratives that do so 50 percent of the

time (fo = 14; fe = 9.2). Losing narratives concentrate benets 81.8% of the time

(fo = 27; fe = 22.2), compared with winning narratives that do so 50 percent of the time

(fo = 14; fe = 18.8). Losing narratives are 4.5 times more likely to concentrate benets,

whereas winning narratives are 4.5 times more likely to diffuse benets (OR = 4.5).

We can accept hypothesis 2.

The association between (i) winning narratives and diffusing benets and (ii)

losing narratives and concentrating benets is a political strategy used by interest

groups to inuence policy outcome. For example, the GYC applauded the success of

the Clinton era snowmobile reductions by citing the improved National Park Service

employees health as well as that of all visitors (Scott, 2004); thus, they diffused the

benets of the ban to many people. Similarly, the BRC presented the diffuse distribution of the benets of snowmobile use to local economies, residents, and snowmobile riders (Collins, 1998). Examples of concentrating benets when losing are

found as a political strategy in both the BRC and the GYC narratives. In a time when

snowmobiling was under attack in the courts, the BRC contended that the only

beneciary from snowmobile regulation was the environmental group Fund for

Animals (Cook, 1997). Similarly, the GYC concentrated benets by claiming that

President Bush was ignoring larger national interests and instead was bowing to

intense lobbying by the snowmobile industry and the parks border towns (GYC,

2002). Concentrating or diffusing the benets of a policy proposal is a political

narrative strategy employed to inuence policy outcome.

Hypothesis 3: Concentration and Diffusion of Costs

Table 4 also indicates a statistically signicant association between the concentration and diffusion of costs of the narrative frame (c2[d.f. = 1] = 11.683, p < 0.001).

The measure of association is strong, with Cramrs V = 0.371, p < 0.001. Winning

narrative frames concentrate costs 55.6 percent of the time (fo = 10; fe = 4.4) compared

to 16.4 percent for groups with losing frames (fo = 11; fe = 16.6). As hypothesized,

losing narrative frames diffuse costs 83.6 percent of the time (fo = 56; fe = 50.4) compared to 44.4 percent of the time for winning frames (fo = 8; fe = 13.6). Losing narratives are six times more likely to concentrate costs, whereas winning narratives are

six times more likely to diffuse costs (OR = 6.36). We can accept hypothesis 3.

Losing narratives are thought to diffuse costs of the proposed policy as a way

to expand the issue, whereas winning narratives contain the issue by concentrating

the costs on a few. When losing, the BRC tended to diffuse costs by focusing on

how snowmobile riders and the snowmobile community would pay the costs in

time, enjoyment, and recreational access, which would negatively impact tourism

and gateway communities. Similarly, the GYC diffused costs over stressed wildlife,

human health, visitor enjoyment, deteriorating ecosystems, nonmotorized recreationists, and public safety. Finally, when concentrating costs, winning narratives

construct narrow entities to endure costs, such as commercial logging (GYC,

2001a) or narrow special interest groups (Welch, 2000).

100

Policy Studies Journal, 35:1

Hypothesis 4: Use of Condensation Symbols

There is a statistically signicant association between the use of condensation

symbols and narrative frames (c2[d.f. = 1] = 3.490, p < 0.10); this is asserted with the

acceptance of a higher risk of making a Type I error, with p < 0.10 (see Table 5). The

measure of association is weak, with Cramrs V = 0.182, p < 0.10. As hypothesized,

losing narrative frames use condensation symbols more frequently than winning

narratives, that of 42.3 percent of the time (fo = 30; fe = 25.7) compared to 23.5 percent

of the time (fo = 8; fe = 12.3), respectively. Losing narratives are approximately

2.4 times more likely to use condensation symbols (ORLCS = 2.39). We can accept

hypothesis 4.

The effect of condensation symbols is to heighten emotions and create a Hobsons choice in policy preference. Interestingly, the BRC was more likely to use

characterization symbols (n = 9 for the BRC or 17 percent of the time; n = 4 for the

GYC or 7.7 percent of the time), whereas the GYC was much more likely to use issue

symbols (n = 19 for GYC or 36.5 percent of the time; n = 9 for the BRC or 17 percent

of the time). For example, while on the losing end of policy disputes, the BRC

characterized their opponents as school yard bullies with hit lists and hate

mail (Collins, 1998) and out in left eld (Eggers, 1999), while the GYC refers to a

Yellowstone with snowmobiling as a noisy speedway (GYC, 2001b).

Hypothesis 5: Use of Surrogates

Table 5 reveals a statistically signicant association between use of policy surrogates and narrative frames (c2[d.f. = 1] = 5.122, p < 0.05), with a Cramrs V

measure of association of 0.221 (p < 0.05). Policy surrogates are used by losing narratives 32.4 percent of the time (fo = 23; fe = 18.3), whereas they are used by winning

Table 5. Chi-Square Results for Condensation Symbols and Policy Surrogates by Narrative Frame

Losing Narrative

Condensation symbols

Policy surrogate

Winning Narrative

Yes

Total

42.3%

23.5%

38

(30)

(8)

No

57.7%

76.5%

67

(41)

(26)

Total

100.0%

100.0%

105

(71)

(34)

c2(d.f. = 1) = 3.490, p < 0.10; Cramrs V = 0.182, p < 0.10; ORLCS = 2.39

Yes

32.4%

11.8%

27

(23)

(4)

No

67.6%

88.2%

78

(48)

(30)

Total

100.0%

100.0%

105

(71)

(34)

c2(d.f. = 1) = 5.122, p < 0.05; Cramrs V = 0.221, p < 0.05; ORLPS = 3.59

Source: Greater Yellowstone Coalition and Blue Ribbon Coalition documents, 19972004.

ORLCS, odds ratio of losing narratives use of condensation symbols.

ORLPS, odds ratio of losing narratives use of policy surrogates.

McBeth et al: Narrative Policy Analysis and Policy Change Theory Intersection

101

narratives only 11.8 percent of the time (fo = 4; fe = 8.7). Losing narratives are more

than three times more likely to use a policy surrogate than a winning narrative

(ORLPS = 3.59). We can accept hypothesis 5.

In political narratives, losing groups are more likely to strategically wrap the

issue in the larger contentious cultural context by using policy surrogates. This use

of a policy surrogate is again consistent with Baumgartners and Jones (1993) theory

of issue expansion when a group is losing and with the research of Nie (2003) on

environmental policy conict. The BRCs policy surrogates tend to focus on either

federalism or environmental elitism, arguing, we cant rely on the federal government to represent the publics interest (Cook, 1997). Furthermore, the BRC argued

that policy was needed to see our natural resources protected FOR the people

instead of FROM the people (Eggers, 1999). The GYC almost exclusively used

surrogates when they were losing, only using a surrogate once when they were

winning on an issue. Their surrogates focused on corruption by special interests, as

exemplied in this statement from one of their articles: National interest is being

sacriced to the special interest of the snowmobile industry in of all places, Americas rst national park (Sieck, 2002).

Hypothesis 6: Scientic Certainty or Uncertainty

As revealed in Table 6, there is no statistical association between winninglosing

narrative frames and how science is used, either to show certainty or uncertainty. We

reject hypothesis 6. Approximately 50 percent of both winning and losing narratives

use science in their narratives; of those, both narrative frames used scientic certainty at high rates, 89.5 and 85.7 percent, respectively.

When both interest groups used science regardless of whether they were

winning or losing, they tended to use it in terms of scientic certainty to back up

their policy preference. Nie (2003, p. 323) concludes that competing groups in environmental policy controversies use science to forward their preferred policy objectives. The focus of science used in the two groups narratives is different; the GYC

uses a conservation biology approach whereas the BRC uses a more technological

approach (McBeth et al., 2005, p. 422). In general, the conict over science between

competing interest groups is usually a battle over the stable policy core beliefs

embedded in the science rather than part of a dynamic narrative political strategy.

Table 6. Chi-Square Results for Science by Narrative Frame

Losing Narrative

Science

Certainty

85.7%

(30)

Uncertainty

14.3%

(5)

Total

100.0%

(35)

c2(d.f. = 1) = 0.154, ns; Cramrs V = 0.053, ns

Winning Narrative

Total

89.5%

(17)

10.5%

(2)

100.0%

(19)

47

Source: Greater Yellowstone Coalition and Blue Ribbon Coalition documents, 19972004.

7

54

102

Policy Studies Journal, 35:1

Controlling for Presidential Administration and Use of Science

The ACF theory asserts that changes in governing coalitions affect policy change

in that coalitional resources expand or contract, depending on whether the administration aligns itself with a groups core beliefs or not. For example, the Bush

administrations shared policy beliefs added resources (power) to the BRC. Not

surprisingly, controlling for presidential administration resulted in additive relationships among all six statistically signicant political strategies. The relationship

between political strategies and narrative frame persisted in direction and varied

only somewhat in each control table. Thus, in understanding policy change, changes

in governing coalitions and political strategies are critical.

Additionally, the ACF theory differentiates between policy learning within a

belief system and across belief systems (Jenkins-Smith & Sabatier, 1993, p. 48). In the

former, science is used to bolster a groups core beliefs; in the latter, scientic

evidence and coalitional technical expertise can alter core beliefs over time. Given the

wicked-problem nature of the GYA, when groups use science, it is used within a

belief system to reify a groups policy beliefs. In controlling for those narratives that

used science, ve of the six political strategies remained virtually unchanged; thus,

use of science is not related to winning or losing strategies. However, controlling for

use of science led to the evaporation of any relationship between condensation

symbols and narrative frame, thus weakening the interpretation of the use of condensation symbols as a narrative political strategy.

Discussion

In this study, we seek to present a new methodological approach to the understanding of the policy change process by integrating NPA and policy change theory

while upholding the standards of traditional social science research. Our rst

research questionwhether or not NPA can be used appropriately within the

context of traditional policy change theoryis answered afrmatively. In this study,

issue expansion and containment in the turbulent GYA policy arena is empirically

tested through coding interest group narratives. We systematically test whether or

not winning narrative frames attempt to contain the issue with predictable narrative

strategies (identication of winners, diffusion of benets and concentration of costs

of policy success, and use of scientic certainty) and whether or not losing narrative

frames attempt to expand the issue with predictable narrative strategies (identication of losers, concentration of benets and diffusion of costs of policy failure, use of

condensation symbols and policy surrogates, and use of scientic uncertainty).

While advocacy coalitions embed stable policy core beliefs in narratives, they also

use those narratives to further dynamic political strategies.

Our second research questionwhether or not operationalized narrative strategies reect how groups attempt to contain or expand the policy issueis also

answered afrmatively. When using the ACF controls, ve of the seven hypotheses

are supported. The data provide evidence for the notion that interest group narratives are indicators of a groups political strategies and tactics and are tied to whether

McBeth et al: Narrative Policy Analysis and Policy Change Theory Intersection

103

a group is winning (and trying to contain an issue) or losing (and trying to expand

an issue). Importantly, these strategies are not tied to core beliefs, nor are they

ideologically based or reective of writing ability or style. These strategies cut across

ideological lines, are used by both sides in the policy dispute, and are connected to

how a group perceives its position in the policy battle. Thus, narratives as a source of

study are strategic, predictable, and testable and are an appropriate unit of analysis

for scholars interested in studying policy change.

Finally, our third research question explores the additions to the literature. This

method of analysis integrates NPA with policy change theory and adds to the

existing literature. The contribution here addresses Brown and Stewarts (1993,

p. 101) criticism of the ACF. We argue that narratives as political strategies are a

valuable source of study for researchers. The activity in the GYA occurred in periods

of alternating victories and losses. Although several external subsystem events (e.g.,

court opinions, well-publicized media events, changes in presidential administrations) could have swung the policy battles toward one group or another by producing shifts in coalitional resources, the two interest groups consistently perceived

themselves as losing 67.6 percent of the time. Losing narratives, as we have seen, are

more confrontational and seek to expand conict to additional parties. In wicked

policy problems, interest group narratives only reinforce and exacerbate policy

intractability. Short-term wins are quickly replaced by the perception of losing and

the need to retaliate. The effect is that the narratives almost continually expand the

scope of the conict, thus drawing in more groups to the policy dispute. As seen in

the eight-year course of this study, the result is long periods of protracted conict.

The GYA policymaking meets the conditions of what Sabatier and Jenkins-Smith

(1999, p. 132) call the devil shift or the situation where opposing coalitions

remember losses more than victories and inate the evilness and power of opposing groups. In addition, this research involved two purposive interest groups, and

these groups, as hypothesized by Sabatier and Jenkins-Smith (1999, p. 134), maintain

a tight script and thus resist alterations to their scripts that would move dialogues

toward policy learning.

In policy environments where there is both a clear policy monopoly and a clear

out-of-power coalition, we would assume that the minimal coalition of a policy

monopoly would rarely perceive that they are losing and that their narratives would

consistently reect the theory of issue containment. Research on narratives in stable

policy environments might provide initial signs for policy researchers that the policy

equilibrium had been punctuated.

Conclusion

This work has used a case study of environmental policy making in the GYA to

examine the interest group use of narrative political strategies in defending existing

policies or advocating new policies. Grounded in the theories of Sabatier, JenkinsSmith, Baumgartner, Jones, Schattschneider, Stone, and others, the methodological

model is generalizable to any policy subsystem in such policy areas as economic

104

Policy Studies Journal, 35:1

development, energy, crime, and foreign policy. The intersection of policy change

theory and NPA prompts theory building.

In determining the extent to which our work contributes to this theory building,

we turn to Sabatier (1999, pp. 26670), who argues that there are seven guidelines for

theory development. First, our analysis is empirical with testable hypotheses.

Second, our method allows for testing of our hypotheses in a variety of policy

settings. Third, we found a causal relationship between perception of winning and

losing and policy narrative strategies and have accounted for some ACF controls.

Fourth, our study suggests that individuals are political, seek to win, and intentionally and strategically use narratives to either contain or diffuse a policy issue. Fifth,

we have shown a consistency among ve of our seven hypotheses. Sixth, our aim is

to build a long-term research agenda and invite others to build upon our methodology. Finally, our research uses principles from the ACF, punctuated equilibrium,

and three streams of policy change and enhances these works with NPA. We conclude that narrative political strategies are a vital source for analyzing policy change

in a complex political environment.

Mark K. McBeth is a professor of political science at Idaho State University.

Elizabeth A. Shanahan is an assistant professor of political science at Montana State

University.

Ruth J. Arnell is a doctoral student in political science at Idaho State University.

Paul L. Hathaway is a doctoral student in political science at Idaho State University.

Notes

A different version of this paper was presented at the 2005 Western Political Science Conference in

Albuquerque, New Mexico. The authors wish to thank Teri Peterson for her statistical consultations.

1. The BRC is part of a larger advocacy coalition (the wise use coalition) that includes ranchers, local

business elites, snowmobile, ATV, and motorcycle manufacturers, elected ofcials, and scientists.

2. The GYC is part of a larger advocacy coalition (the environmental coalition) that includes national

environmental groups, local business elites, elected ofcials, and scientists.

3. The identication of benets as diffuse or concentrated resulted in mutually exclusive coded responses;

in other words, when benets were coded, they were either concentrated or diffused. Hence, they are

included in the same hypothesis. The same is true for concentrateddiffuse costs (hypothesis 3) and

uncertaintycertainty in use of science (hypothesis 6).

References

Achter, Paul J. 2004. TV Technology, and Mccarthyism: Crafting the Democratic Renaissance in an Age of

Fear. Quarterly Journal of Speech 90: 30726.

Baumgartner, Frank R. 1989. Conict and Rhetoric in French Policy Making. Pittsburgh, PA: University of

Pittsburgh Press.

Baumgartner, Frank R., and Bryan D. Jones. 1993. Agendas and Instability in American Politics. Chicago, IL:

University of Chicago Press.

Berry, Jeffrey M. 1989. The Interest Group Society, 2nd ed. New York: Harper Collins Publishers.

Brown, Anthony, and Joseph Stewart Jr. 1993. Competing Advocacy Coalitions, Policy Evolution, and

Airline Deregulation. In Policy Change and Learning: An Advocacy Coalition Approach, ed. Paul A.

Sabatier, and Hank C. Jenkins-Smith. Boulder, CO: Westview Press, 83103.

McBeth et al: Narrative Policy Analysis and Policy Change Theory Intersection

105

Catton, John, and Betsy Bufngton. 2002. Snowmobiling Abuses in Yellowstone Continue Despite Costly

New Mitigation Efforts. http://www.greateryellowstone.org/snowmobiles_exhaust_nr.html

Accessed August 20, 2002.

Cawley, McGreggor R., and John Freemuth. 1993. Tree Farms, Mother Earth, and Other Dilemmas: The

Politics of Ecosystem Management in Greater Yellowstone. Society and Natural Resources 6: 4153.

Clark, Timothy W., and Steven C. Minta. 1994. Greater Yellowstones Future. Moose, WY: Homestead

Publishing.

Cobb, Roger W., and Charles D. Elder. 1983. Participation in American Politics: The Dynamics of Agenda

Building. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Collins, Clark. 1998. Help Save Snowmobiling on Our Public Lands. Blue Ribbon Magazine (July).

http://www.sharetrails.org/mag/jul98. Accessed August 17, 2002.

Cook, Adena. 1997. Yellowstone Suit Settlement Denounced: Hanky Panky Uncovered. Blue Ribbon

Magazine (November). http://www.sharetrails.org/mag/nov97/hanky. Accessed August 17, 2002.

Eggers, Viki. 1999. Earth Island Petition Debunked: Enviro Facts Are Fantasy. Blue Ribbon Magazine

(March). http://www.sharetrails.org/mag/Mar99/Story4.htm. Accessed February 21, 2003.

Fischer, Frank, and John Forrester. 1993. The Argumentative Turn in Policy Analysis and Planning. Durham,

NC: Duke University Press.

Greater Yellowstone Coalition (GYC). 2001a. A Nationwide Plea is Heard: Barring Political Interference,

Americas Roadless Forests Will Be Protected. Greater Yellowstone Report Newsletter (Spring 2001).

http://www.greateryellowstone.org/roadless_sp01nl.html. Accessed December 13, 2003.

. 2001b. Yellowstones Road to Recovery. Greater Yellowstone Report (Early Summer): 911.

. 2002. Park Plan Stinks, No Matter How You Cut It. http://www.greateryellowstone.org/

snowmobiles_gftrib_ed02.html. Accessed December 13, 2003.

Hajer, Maarten. 1993. Discourse Coalitions and the Institutionalization of Practice: The Case of Acid Rain

in Great Britain. In The Argumentative Turn in Policy Analysis and Planning, ed. Frank Fischer, and

John Forester. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 4376.

Jenkins-Smith, Hank C., and Paul A. Sabatier. 1993. The Dynamics of Policy-Oriented Learning. In Policy

Change and Learning: An Advocacy Coalition Approach, ed. Paul A. Sabatier, and Hank C. Jenkins-Smith.

Boulder, CO: Westview Press, 4158.

Johnson, Janet Buttolph, and H. T. Reynolds. 2005. Political Science Research Methods. 5th ed. Washington,

DC: CQ Press.

Kingdon, John W. 1995. Agendas, Alternatives, and Public Policies. New York: Longman.

Knoke, David, George W. Bohrnstedt, and Alisa Potter Mee. 2002. Statistics for Social Science Data Analysis,

4th ed. Itasca, IL. F.E. Peacock Publishers.

McBeth, Mark K., Elizabeth A. Shanahan, and Michael D. Jones. 2005. The Science of Storytelling:

Measuring Policy Beliefs in Greater Yellowstone. Society and Natural Resources 18: 41329.

McClendon, McKee J. 2004. Statistical Analysis in the Social Sciences. Belmont, CA: Thomson.

Nie, Martin A. 2003. Drivers of Natural Resource-Based Political Conict. Policy Sciences 36: 30741.

Radaelli, Claudio M. 1999. Harmful Tax Competition in the EU: Policy Narratives and Advocacy Coalitions. Journal of Market Studies 37: 66182.

Ramsey, Fred L., and Daniel W. Schafer. 1997. The Statistical Sleuth: A Course in Methods of Data Analysis.

Belmont, CA: Wadsworth Publishing Company.

Riker, William H. 1962. A Theory of Winning Coalitions. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Rittel, Horst W. J., and Melvin M. Webber. 1973. Dilemmas in a General Theory of Planning. Policy

Sciences 4: 15569.

Roe, Emery. 1994. Narrative Policy Analysis. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Sabatier, Paul A. 1999. Fostering the Development of Policy Theory. In Theories of the Policy Process, chap.

10, ed. Paul A. Sabatier. Boulder, CO: Westview Press, 26176.

. 2000. Clear Enough to Be Wrong. Journal of European Public Policy 7: 13440.

106

Policy Studies Journal, 35:1

Sabatier, Paul A., and Hank C. Jenkins-Smith, eds. 1993. Policy Change and Learning: An Advocacy Coalition

Approach. Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

. 1999. The Advocacy Coalition Framework: An Assessment. In Theories of the Policy Process, ed.

Paul A. Sabatier. Boulder, CO: Westview Press, 11766.

Schattschneider, E. E. 1960. The Semi-Sovereign People. New York: Holt, Rinehart, & Winston.

Schneider, Anne L., and Helen M. Ingram. 2005. Deserving and Entitled: Social Constructions and Public

Policy. Albany: State University of New York Press.

Schon, Donald, and Martin Rein. 1994. Frame Reection: Toward the Resolution of Intractable Policy Controversies. New York: Basic Books.

Scott, Michael. 2004. Rangers No Longer Getting Sick in Yellowstone. News Release (February). http://

www.news.greateryellowstone.bridgeband.net/article. Accessed July 7, 2004.

Sieck, Hope. 2002. Yellowstones Winter in Question. Greater Yellowstone Reports (Summer): 67.

Stone, Deborah. 2002. Policy Paradox: The Art of Political Decision Making, revised ed. New York: W.W.

Norton.

Tierney, John, and William Frasure. 1998. Culture Wars on the Frontier: Interests, Values, and Policy

Narratives in Public Lands Politics. In Interest Group Politics, ed. Allan J. Cigler, and Burdett Loomis.

Washington, DC: CQ Press, 30326.

Welch, Jack. 2000. Blue Ribbon Delivers 10,170 Comment Letters to National Park Service on Winter Use

Plan for Yellowstone. Blue Ribbon Magazine (January). http://www.sharetrails.org/mag/Jan2000/

story6.htm. Accessed August 17, 2002.

Wilson, Matthew A. 1997. The Wolf in Yellowstone: Science, Symbol, or Politics? Deconstructing the

Conict between Environmentalism and Wise Use. Society and Natural Resources 10: 45368.

Wood, B. Dan, and Alesha Doan. 2003. The Politics of Problem Denition: Applying and Testing Threshold Models. American Journal of Political Science 47 (4): 64053.

Appendix A: Abbreviated Code Book

1. Does the narrative identify a specic winner (entity that benets) of a policy

decision or potential decision? For example, anti-recreationists will rejoice over

this policy decision or the snowmobile industry is clearly rooting for this

lawsuit to be thrown out of court.

A-Yes (go to question #2) B-No (skip to question #3)

2. What best describes how the narrative constructs the benets of the policy

decision?

A-The narrative is constructed as providing concentrated benets (a few

gain). For example, the wealthy environmentalists will have YNP as

their personal playground or this decision benets the snowmobile

industry.

Paragraph number(s) and group:

B-The narrative is constructed as providing diffused benets (many gain).

For example, the American people will benet from the closing of YNP to

snowmobiles or snowmobile enthusiasts from throughout the country

applauded this decision.

Paragraph number(s) and group:

3. Does the narrative identify a specic loser (entity that pays the costs) of a policy

decision? For example, the American people are the losers when industry

controls government or local businesses are hurt by these actions of the NPS.

McBeth et al: Narrative Policy Analysis and Policy Change Theory Intersection

107

A-Yes (go to question #4) B-No (skip to question #5)

4. What best describes how the narrative constructs the costs of the policy decision?

A-The narrative is constructed as providing concentrated costs (a few pay).

For example, This regulation will harm only a small number of greedy

business owners who fail to adapt to changing times or The throwing out

of this policy will only harm the sensibilities of a few extremists.

Paragraph number(s) and group:

B-The narrative is constructed as providing diffused costs (the many pay).

For example, this plan protects bison while projecting costs over many

differing groups or this plan protects snowmobiling with only minor

adjustments required of business owners who must now be licensed guides

and use cleaner machines.

Paragraph number(s) and group:

5. Does the narrative contain at least one condensation symbol? The denition of a

condensation symbol is a word or phrase that shrinks and reduces complicated

concepts into simple, manageable, or memorable forms.

A-Yes, list and identify paragraph(s) B-No

6. Does this narrative use a policy surrogate? For example, policy surrogate =

greedy snowmobile corporations exploit Yellowstone for their own purposes

while the pollution gets worse and worse or this issue is all about people in

Washington, DC telling people in our small towns about how to live their lives.

A-Yes, list and identify paragraph(s) B-No

7. Does the narrative use science to dene a problem, counter a problem denition,

or justify a policy approach?

A-Yes. (go to question #8) B-No (go to question #9)

8. Is the mention of science used in the context of:

A-Disputing science B-Establishing scientic certainty

9. What is the stance of the narrative towards the policy being discussed?

A. Winning (supports the policy environment and actions discussed in the

narrative)

B. Losing (the group is under attack even if they are partially winning)

108

Policy Studies Journal, 35:1

Appendix B: Intercoder Reliability

Question

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

TOTAL

Agreement (%)

243

23

275

210

268

259

156

156

251

(78%)

(93%)

(87%)

(89%)

(85%)

(82%)

(84%)

(96%)

(80%)

1,941 (85%)

Disagreement (%)

72

9

40

25

47

56

30

6

64

(22%)

(7%)

(13%)

(11%)

(85%)

(18%)

(16%)

(4%)

(20%)

349 (15%)

Total Codings

315

132

315

235

315

315

186

162

315

2,290 (100%)

Note. Questions 1, 3, 5, 6, and 9 are paired codings comparing the three coders to each other. All coders

coded this screening questions. These questions all sum to 315 (105 documents 3 coders). Questions 2

and 4 are also paired codings but have smaller numbers because of screenings. The rst 75 documents for

question #7 were coded by only two coders. Because there were only 2 coders there was only 1 paired

coding instead of 3 on this question. Thus the total number of codings for question 7 equals only 186.

You might also like

- More Practice Exercises Units 5 and 6 (With Answers)Document8 pagesMore Practice Exercises Units 5 and 6 (With Answers)Hadjla Miloua SedjerariNo ratings yet

- Majone (1992) Assessment-Evidence-Argument-Persuasion PDFDocument9 pagesMajone (1992) Assessment-Evidence-Argument-Persuasion PDFFabio Alberto Gil BolívarNo ratings yet

- Sabatier-Summary CH 1-5-Theories of The Policy ProcessDocument5 pagesSabatier-Summary CH 1-5-Theories of The Policy ProcessGary Larsen100% (1)

- Nowlin, Matthew C. (2011) Theories of The Policy ProcessDocument20 pagesNowlin, Matthew C. (2011) Theories of The Policy ProcessMatheus Dias Ramiro100% (1)

- Toward Better Theories of The Policy Process 1991 PDFDocument11 pagesToward Better Theories of The Policy Process 1991 PDFPraise NehumambiNo ratings yet

- Beyond SES A Resource Model of Political ParticipationDocument25 pagesBeyond SES A Resource Model of Political ParticipationFlávia FrancoNo ratings yet

- Transcending New Public Management - The Increasing Complexity of Balancing Control and Autonomy, T. Christensen and P. LægreidDocument28 pagesTranscending New Public Management - The Increasing Complexity of Balancing Control and Autonomy, T. Christensen and P. LægreidCamelia RotariuNo ratings yet

- How Countries Democratize - Samuel HuntingtonDocument39 pagesHow Countries Democratize - Samuel HuntingtonCedrick Cochingco SagunNo ratings yet

- Approaching Development-An Opinionated ReviewDocument17 pagesApproaching Development-An Opinionated ReviewjeremydadamNo ratings yet

- PG Diploma in Oil & Gas Piping Engineering Design and AnalysisDocument28 pagesPG Diploma in Oil & Gas Piping Engineering Design and AnalysisabdullahNo ratings yet

- calceSARA PDFDocument77 pagescalceSARA PDFRajesh ChanduNo ratings yet

- Gamma World - Misc Dragon Articles PDFDocument117 pagesGamma World - Misc Dragon Articles PDFAnthony Casab100% (6)

- Weiss 1973 WherePoliticsAndEvaluationMeetDocument14 pagesWeiss 1973 WherePoliticsAndEvaluationMeetFred Oliveira RodriguesNo ratings yet

- Cairney 2020 - Understanding Public Policy - 2 Edition - Front MatterDocument20 pagesCairney 2020 - Understanding Public Policy - 2 Edition - Front MatterLucas100% (1)

- Michael HowlettDocument17 pagesMichael HowlettSorina CarsteaNo ratings yet

- Sebastian Koehler - Lobbying, Political Uncertainty and Policy Outcomes (2019, Springer International Publishing - Palgrave Macmillan)Document173 pagesSebastian Koehler - Lobbying, Political Uncertainty and Policy Outcomes (2019, Springer International Publishing - Palgrave Macmillan)Luiz Paulo FigueiredoNo ratings yet

- Party Polarization and Mass PartisanshipDocument26 pagesParty Polarization and Mass PartisanshipNadeem KhanNo ratings yet

- Sanger Kingdon Case Paper 1800.03Document5 pagesSanger Kingdon Case Paper 1800.03Kellen SangerNo ratings yet

- Agenda Setting and Problem Definition PDFDocument13 pagesAgenda Setting and Problem Definition PDFPraise NehumambiNo ratings yet

- The Majoritarian and Proportional Visions and Democratic ResponsivenessDocument9 pagesThe Majoritarian and Proportional Visions and Democratic ResponsivenessKeep Voting SimpleNo ratings yet

- 09.09 - DALTON, Russell J., and Steven Weldon. 2007. "Partisanship and Party System". Voting BehaviorDocument19 pages09.09 - DALTON, Russell J., and Steven Weldon. 2007. "Partisanship and Party System". Voting BehaviorFran Veas BravoNo ratings yet

- The Calculus of Consent (Gordon Tullock, James M. Buchanan) PDFDocument384 pagesThe Calculus of Consent (Gordon Tullock, James M. Buchanan) PDFAnamika Vats100% (1)

- Resenha Do Livro After Hegemony de KeohaneDocument10 pagesResenha Do Livro After Hegemony de KeohaneGustavo HirschNo ratings yet

- Public PolicyDocument42 pagesPublic PolicybrooklynsnowNo ratings yet

- Bounded Rationality and Garbage Can Models of Policy-MakingDocument20 pagesBounded Rationality and Garbage Can Models of Policy-MakingJoão Carvalho LealNo ratings yet

- Institutional IsmDocument16 pagesInstitutional IsmRalucaNo ratings yet

- Incremental AdvocacyDocument25 pagesIncremental AdvocacyCharlon RamiscalNo ratings yet

- Schmidt, V.A. Discursive Institutionalism. The Explanatory Power of Ideas and DiscourseDocument26 pagesSchmidt, V.A. Discursive Institutionalism. The Explanatory Power of Ideas and DiscourseIvan PisetaNo ratings yet

- Lodge What Is Regulation 2016Document43 pagesLodge What Is Regulation 2016Muhammad Rasyid Redha AnsoriNo ratings yet

- Participatory Policy MakingDocument6 pagesParticipatory Policy MakingJasiz Philipe OmbuguNo ratings yet

- Building Political Parties:: Reforming Legal Regulations and Internal RulesDocument70 pagesBuilding Political Parties:: Reforming Legal Regulations and Internal RulesDanielNo ratings yet

- American Business, Public Policy, Case-Studies, and Political TheoryDocument29 pagesAmerican Business, Public Policy, Case-Studies, and Political TheoryGutenbergue Silva100% (1)

- Gendered PoliticsDocument30 pagesGendered PoliticsTherese Elle100% (1)

- Entman - Cascading Activation Contesting The White House S Frame After 9 11Document19 pagesEntman - Cascading Activation Contesting The White House S Frame After 9 11Joaquin PomboNo ratings yet

- Oxfordhb Mov y PartidosDocument16 pagesOxfordhb Mov y PartidosJorge JuanNo ratings yet

- States of Development On The Primacy of Politics in Development by Adrian Leftwich PDFDocument6 pagesStates of Development On The Primacy of Politics in Development by Adrian Leftwich PDFChiku Amani ChikotiNo ratings yet

- Politics of DevelopmentDocument2 pagesPolitics of DevelopmentAngelika May Santos Magtibay-VillapandoNo ratings yet

- Blake, Global Distributive Justice-Why Political Philosophy Needs Political ScienceDocument16 pagesBlake, Global Distributive Justice-Why Political Philosophy Needs Political ScienceHelen BelmontNo ratings yet

- InstitutionalismDocument13 pagesInstitutionalismMargielane AcalNo ratings yet

- Measuring Democratic ConsolidationDocument27 pagesMeasuring Democratic ConsolidationAbdelkader AbdelaliNo ratings yet

- North Weingast HistoryDocument80 pagesNorth Weingast HistoryScott BurnsNo ratings yet

- Köllner y Basedau, 2005 Factionalism in Political Parties PDFDocument27 pagesKöllner y Basedau, 2005 Factionalism in Political Parties PDFJamm MisariNo ratings yet

- Sabatier & Mazmanian. The Implementation of Public Policy PDFDocument24 pagesSabatier & Mazmanian. The Implementation of Public Policy PDFbetica_00No ratings yet

- PRESSMAN Jefrey y Aaron WILDAVSKY - Implementation en Shafritz - Classics of Public AdministratioDocument4 pagesPRESSMAN Jefrey y Aaron WILDAVSKY - Implementation en Shafritz - Classics of Public AdministratioAngela Quillatupa MoralesNo ratings yet

- Paradigms of Public AdministrationDocument7 pagesParadigms of Public AdministrationannNo ratings yet

- Policy, Office, Orvotes?: How Political Parties in Western Europe Make Hard DecisionsDocument27 pagesPolicy, Office, Orvotes?: How Political Parties in Western Europe Make Hard DecisionsBrian ClarkNo ratings yet

- Meguid 2008 Party Competition Between UnequalsDocument338 pagesMeguid 2008 Party Competition Between UnequalsMariken Van Der VeldenNo ratings yet

- James S. Fishkin Democracy and Deliberation New Directions For Democratic Reform 1991Document126 pagesJames S. Fishkin Democracy and Deliberation New Directions For Democratic Reform 1991Miguel Zapata100% (2)

- Briefing Paper: Electoral CorruptionDocument12 pagesBriefing Paper: Electoral CorruptionThe Ethiopian AffairNo ratings yet

- Pippa Norris The Concept of Electoral Integrity Forthcoming in Electoral StudiesDocument33 pagesPippa Norris The Concept of Electoral Integrity Forthcoming in Electoral StudiesjoserahpNo ratings yet