Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Patrika: The Society For Indian Tradition and Arts

Patrika: The Society For Indian Tradition and Arts

Uploaded by

neeraja_iraharshadOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Patrika: The Society For Indian Tradition and Arts

Patrika: The Society For Indian Tradition and Arts

Uploaded by

neeraja_iraharshadCopyright:

Available Formats

The Society for

Indian Tradition

and ARts

Spring 2002

Patrika

The Biannual news magazine from SiTaR

Vol.6 No.1

Back to Stay!

SiTaR, in 2001, has grown in stature, from being a

student organization in Iowa State University that

aims at infusing Ethnic Indian culture in the ISU

community to being the mouthpiece of Indian

culture in Ames. Today SiTaR is strong and only

growing stronger in terms of the number of events,

their diversity, student membership, faculty

patronage, workforce and funding. This issue of

Patrika is a tribute to the Udpas, whose invaluable

patronage towards SiTaR will never be paralleled.

SiTaR has always been fortunate to have

moral and logistic support from Indian

faculties at Iowa State University The

Udpas, Prof. Satish Udpa and Prof. Lalita

Udpa, had been two of the most prominent

among them. Between the two of them they

served as faculty advisors of SiTaR for

number of years. Even outside of official

capacity, they were always extremely helpful

and resourceful. We cannnot remember of a

single incident when the Udpas turned down

a request from SiTaR the student officers

of SiTaR always knew there were these two

individuals they could count on. However

busy they may be, the Udpas have always

made themselves available to discuss SiTaRrelated issues with the student officers.

SriRam Nadathur

Editor

Contents

Why Carnatic Music?

Todd M. McComb

Distinguishing Features of Indian

Classical Music

Ganesh Sriram

Lok-Nritya: Indian Folk Dances

Rohini Ramaswamy

2

4

6

Their vast knowledge of Indian classical

music and dance was an asset to SiTaR as

well. On a personal basis, I enjoyed their

impressive collection of Indian classical

music, and so did many other students with

similar interest. Such was their enthusiasm

that they even drove out of state to bring

artistes to Ames so that they could perform

here.

We at SiTaR are truly privileged to have Dr. Balaji

Narasimhan as our advisor since Fall 2001. Balaji is

a faculty member in ChE, and recently moved to

Iowa State from Rutgers, when he married Surya

Mallapragada, also faculty member in ChE. He has

a flair for Indian classical music, and has been

trained to play the Mridangam. On another front, he

has an avid interest in movies, and has a

breathtaking collection of 1000+ videos and DVDs.

Hes known to be a great teacher, and a wonderful

person to work with. We are look forward to a great

term working under his guidance.

SiTaR would definitely miss the Udpas

two

of

its

best

champions

and

patrons and so would all of us who have

known them personally.

We wish

them our best for all their endeavors.

Bodhisattva Das

Past President, SiTaR

and rhythmic ideas. In what tradition can the songs be said

to be so perfect, both in their grandeur and in their

succinctness? There can be no comparison, especially in the

directness of the expression and the range of melodic

material available. One can find one or the other in many

places, whether a simple and beautiful song, or an

impressive intellectual construction based on a nonsense

phrase or no words at all. Carnatic music accommodates

both of these ideals, and does so to magnificent effect. A

song can be performed simply and in all humility, or with

the grandest elaboration retaining the core of both meaning

and melody.

Why Carnatic Music?

Todd M. McComb

Todd McComb is based in the Silicon Valley, and does

organizational work for the Medieval Music & Arts

Foundation. He is interested in a variety of World Music

forms, especially, as this article portrays, Indian classical

music of the Carnatic style which comes as a surprise

since Todd is American. His webpage www.medieval.org is

a valuable resource on various kinds of World music.

Of course the meaning of the lyrics revolves around acts of

religious devotion. One can rightly ask both concerning the

relevance of devotion in our modern age of technology and

selfishness, as well as the ability of a Westerner to

apprehend and appreciate it. Indeed, it would be

presumptuous of me to suggest that I fully understand the

songs of the Trinity. I understand parts of them, sometimes

after they are explained to me. Nonetheless, I identify with

them somehow. The ideas find a personal resonance, not

least of which because they are expressed with such musical

grace. The sophistication of allusion requires some crosscultural explanation, but the core idea of devotion meets

with receptive listeners elsewhere.

As a Westerner interested in Carnatic music, I am frequently

asked to explain my interest and to articulate what makes

South Indian music special. Both Indians and Westerners ask

the same questions. Since I did not grow up with it, but

rather chose it for myself from among a broad range of

world traditions, Carnatic music is special indeed. There is

always a sense in which cross-cultural interactions serve not

only to broaden one's horizons, but also to set one's own

cultural identity more strongly in relief. My more direct and

natural interest in Western traditional music has been

nourished by an appreciation for Indian music, and the same

can hopefully apply in reverse. Here I hope to describe some

points in common, as well as some of the strengths of

Carnatic music from my perspective.

There is a very real sense in which the kritis speak to me,

both in word and in music. They express the power in the

world beyond petty human concerns, something which

music is so ideally suited to express. In the West, Dufay was

no "dasa" and so while he was nominally an official of the

Catholic Church, his influence on our history was more

cosmopolitan. There is less emphasis on devotion, and more

on political events or more ordinary topics. This sequence is

also seen as part of the "modernization" of the West, and of

course it was also the background to the new age of political

conquest. This is the divergence, which perhaps most

strongly conditions the reception which Carnatic music

meets in the West. While the nonsense phrases or abstract

instrumental gats of Hindustani music find an audience in

the meditative Westerner, the unveiled potency of

expression in Thyagaraja insists that the listener confront his

own ideas on his place in the world.

In the West, the classical music known best, that of Mozart

and Beethoven, centers around the medium of the large

orchestra and the ideas of counterpoint and harmony. Within

that context, Indian music is unusual, and the idea that it is

fully "classical" in scope can be met with some resistance.

Curiously, this phenomenon of resistance is reflected in the

reception met by other Western music within the broader

sweep of history. For me, interest in Western music focuses

increasingly on that of the medieval era, from roughly eight

hundred to five hundred years ago. This is an exciting

repertory which is being reconstructed today for public

performance, and it has come to include a wealth of detail

and nuance which can stimulate one both intellectually and

spiritually.

Like Carnatic music, Western medieval music is concerned

more with the song than with the symphony, and indeed the

voice must be seen as its supreme instrument as well. The

song is surely the most basic of human expressions, and the

act of semantic content serves to further invigorate music on

both emotional and intellectual levels. Melody and rhythm

are likewise more complicated in medieval music than in the

more commonly known Western music of the 18th century.

Although the music can hardly be said to compare to the

sophistication of raga and tala, and especially the elaboration

of which modern Carnatic artistes are capable, French

musical terms of the 14th century curiously mirror Indian

music. There is the term "color" for the melodic basis of the

piece and the term "talea" for the sequence of beat patterns,

called broadly as "isorhythm."

Today devotion is an uncomfortable topic for many, and the

same can be said for classical aesthetics. The complementary

ideas that a particular melodic phrase can invoke a specific

human emotional response and that the effectiveness of

music can be reliably ascertained are certainly unpopular

now. In many ways, this is an outgrowth of the same

multiculturalism which allows me to attend Carnatic

concerts, but it is also part of the rise of democracy as an

intellectual ideal as well as a political system. At least in the

US, we are supposedly equal, and the same should be said

for our taste in music. For a professional musician, the idea

is somewhat insulting, because how can the ignorant know

of what they judge? They cannot, but we are forced to

acknowledge them to make a living, if for no other reason.

In Carnatic music, I find first an outlet for my own desire for

elaborations on songs per se, in structure as well as melodic

Purandaradasa is performed, in the ragas as named by

Mutthuswamy Dikshitar or others, or even in talas as given

by Shyama Sastri. This is not generally seen as a problem, or

even as an intellectual issue.

Carnatic music is at a crossroads on the issue of aesthetic

diversity, especially as its international reputation increases.

It is already true that some of the most successful performers

in worldly terms are able to make a living by touring the

West, and not by representing Carnatic music in its most

pure form. Of course there is a very real sense in which an

art form must develop and adjust in order to make the same

impact on its audience, and Carnatic music knows this fact

better than most. It has incorporated the Western violin, and

moved to a modern concert setting, complete with

amplification. Instrumental innovations continue with the

amplified veena and mandolin, as well as the Western

saxophone and clarinet. Carnatic music has easily

maintained its own identity, not least of which because it is a

reservoir of musical ideas and expressions, not specific

combinations of sonorities.

Changes in raga or tala designation are regarded as a natural

part of the evolution of Carnatic music, whether as

clarifications of structural concepts or as simple

improvements to the fit between words and music. There

may or may not be a danger to the idea of evolution in

music, but from a purely scholarly perspective, there is an

inherent interest in knowing how something was done at an

earlier time in history. Some of these details are recoverable

in Carnatic music, but there is consequently an implied

question regarding the guru-shishya system and its ability to

reproduce music exactly. Already many prominent

performers will train with multiple teachers from different

lineages and that is a clear indication that no style will be

preserved exactly. In the past, the same must have been said

for those artistes sophisticated enough to forge their own

new style.

An incredible sense of resiliency has characterized Carnatic

music since the 19th century, and so one can hardly doubt

that it will continue to find that strength today and in the

future. However, in a world, which presently finds so little

use not only for "bhakti rasa" but for the idea that the

concept is even meaningful, in what direction will this

resiliency take it? I am certainly not qualified to indulge in

much speculation, but the answer is an important one to any

Carnatic rasika. There is a tremendous wealth of melodic

and rhythmic material available, as well as a large body of

knowledgeable virtuoso performers, and so treated as raw

material, there is no doubt they will prosper. There is a

question of what the unifying thread will be, and so one can

ask for instance "Do the ragas make Carnatic music?"

It would certainly be pointless to suggest that the talented

musician of today should not develop his or her own gifts

and ideas or that the opportunity to travel and study on

friendly terms with many prominent teachers should not be

taken. It is a philosophical truth that isolation undertaken as

a choice is not the same as that enforced by circumstances,

and so there is not even the possibility of a return to other

methods. What I am suggesting is that we will see a natural

bifurcation between the continuing development of

"mainstream" Carnatic music and an increasing number of

scholar-performers who will recreate historical and regional

styles. Given the ubiquity of the Western university tenure

system, one cannot underestimate the motivation provided

by mandatory publication and thesis in developing these

ideas, for better or worse.

There is some controversy as to what exactly makes a raga.

If it is a sequence of swaras only, then one can make the

same "raga" sound not much like Carnatic music by playing

it without gamakas and in unusual tempo and phrasing. This

is the position of some Indians, as well as that of many

Western composers who use the ragas as raw material. Not

so long ago, a Western composer who wanted to use a raga

as a melody after reading it in a book had probably never

heard it. Although the suggestion may seem absurd, it is

both true, and central to such issues as the performance of

Western medieval music. Indeed the latter has essentially

been resurrected based on writing alone, after a span of

several centuries. Can we imagine how different it must

sound?

Dynamic and invigorating interaction between tradition and

innovation has been a hallmark of Carnatic music, and even

an increased polarization between the two does not need to

damage the overall balance. If anything, it will broaden the

scope of performance opportunities and the range of

available ideas. It is precisely the dual richness of a longstanding tradition together with ample opportunities for

modern virtuoso treatments, which serve to place Carnatic

music among the world's greatest musical styles. As the

divergence increases, as long as one aspect keeps respectful

sight of the other, the available scope for interaction

increases as well. An analogy may be drawn between the

manifest and unmanifest instantiations of Brahma, and

indeed I view the duality between tradition and innovation in

a similar way, dependent on each other. After all, a stagnant

tradition is not true to its origins either, because its origins

are in the crucible of creativity.

For the phenomenon of resurrection in Carnatic music, one

needs to look no farther than the gold engravings of

Anamacharya. Do we know how these kirtanas would have

sounded? In some cases, as with the kirtanas of

Purandaradasa (which are of similar age, but never actually

lost), we know the ragas have changed. Nonetheless, this

music is performed with confidence, derived primarily from

the manner in which similar music is performed and the

knowledge that it has been passed down in this way from

generation to generation. In other words, there is a

continuous tradition of performing Purandaradasa, and so it

is natural to perform the rediscovered songs of Anamacharya

in the same manner. There is no question but that various

changes have occurred, whether in the ragas in which

The success of music is ultimately in the mind of the

listener, and specifically in the emotional changes which can

be provoked. While Carnatic music has only a positive effect

in this way, while the same cannot be said for various forms

of popular music.

(Continued on page 7)

An octave (or a register) is a series of notes ranging from a

given note (the fundamental) to a note whose frequency is

exactly twice that of the fundamental [3].

Figure 1 schematically shows an octave, where the

fundamental note is C (or sa in the parlance of Indian music,

denoted by s). This is shown at the left end of the scale,

and has a relative frequency of 1 unit. At the right end of the

scale is the note C (s) with a relative frequency of 2, i.e.

twice that of the fundamental.

Distinguishing Features of

Indian Classical Music

Ganesh Sriram

Ganesh, the President of SiTaR, is the man behind what

SiTaR is today and what it will be tomorrow. He is a

graduate student in Chemical Engineering at Iowa State

University. He has learnt Carnatic Music and dedicates this

article to his Teacher, Smt. Radha Srisailam.

The eleven dashed lines (C#, D, Eb, ) between the two Cs

are the notes of Western music. These are represented by

seven symbols (C, D, E, F, G, A, and B) corresponding to

the seven notes do, re, me, fa, so, la and ti of the septatonic

(seven-note) scale. The other notes C#, Eb, etc. are

represented as variations of these seven notes. All these

twelve notes C, C#, D, form a geometric progression,

with the ratio 21/12. Thus the relative frequency of C# is 21/12

times that of C, the frequency of G is 27/12 times that of C (or

1.498, as shown in Figure 1). This logarithmic or

equitempered division of the octave was pioneered by

Johann Sebastian Bach, and has become an integral part of

Western music.

According to Ganesh, this article was written in partial

response to the often-asked query Why does Indian

classical music sound exotic to the Western ear? It is a

useful exercise to objectively delineate the features of this

rich form of music (and in particular, those that distinguish

it from Western classical music), in the light of this question.

This article endeavors to accomplish that, in a small

measure.

Introduction

Indian classical music is an ancient art, whose origins can be

traced back to a period almost two millennia ago. Since then,

it has constantly evolved as a performing art, reaching a

level of high sophistication during the medieval ages (15th

through 18th centuries). The art, as we know it today, is

broadly classified into three genres: (1) Hindustani Music

(which originated in North India), (2) Carnatic Music (which

originated in South India), and (3) Dhrupad (the forerunner

of the above two styles). Generations of musicians have

preserved and propagated these forms retaining the

distinctiveness of the art form, while at the same time,

contributing their best to the music and allowing it to

develop and mature. Thus, in spite of a disciplined

adherence to traditional values, there exist immense

opportunities for creativity and innovation [1].

Figure 1: Pitch intervals (microtones or shruti-s) in Indian

and Western music.

Indian classical music has now spread out of the regions

where it originated and was traditionally practiced. With

American Universities teaching this subject in English, and

Swiss Universities in French [2], its global presence is

hardly questionable. However, the music sounds exotic or

alien to many Western ears. This is largely due to a number

of aspects unique to it. This article discusses some of the

distinguishing factors between Indian classical music and

Western classical music (hereafter referred to simply as

Indian music and Western music, respectively), including

pitch intervals, variety of scales, ornamentation, and the

melodic basis of Indian music. Though this article is

oriented towards Carnatic music, most of the arguments

equally apply to other forms of Indian classical music.

The twenty-one solid lines between the two Cs in Figure 1,

are the notes of Indian music. These are represented by

seven symbols sa, ri, ga, ma, pa, dha and ni (shown in

Figure 1 as s, r, g, m, p, d, n). Five of these notes (i.e. all

except sa and pa) have two versions. For example, ga has

two version, g1 and g2. Furthermore, it is interesting to note

that in Indian music, each of these versions (except sa and

pa) has two variations. For example, the note r2 has two

variations: r2- and r2+, whose frequencies are very close to

each other1. The difference between these microtonal

variations becomes evident while comparing the ragas

(modes) Bhairavi and Khara-harapriya. Both modes use the

note r2; however, the former is gets its character from its use

of r2- whereas the latter exclusively uses r2+.

Steps to an Octave

One of the prime differences between Indian music and

Western music is the number of steps to an octave. While

Western music divides the octave into twelve steps, Indian

music divides it into twenty-two steps. This is depicted in

Figure 1, and elucidated in the following paragraphs.

Further, the notes of Indian music are not spaced out

logarithmically like the Western notes, but are derived using

1

In the phraseology of Carnatic music, these two variations

are known as trishruti rishabha (r2-) and chatushruti rishabha

(r2+)

cycles of fourths and fifths. (For an elaborate description of

this derivation, see [4].) This is why the Western and Indian

notes do not coincide exactly. As shown in Figure 1, the note

pa has a frequency of exactly 3/2 (=1.500), while the

corresponding note G has a frequency of 27/12 (=1.498).

While this is a minute difference detectable only by a very

sensitive ear, the difference between other sets of

corresponding notes (e.g. A = 1.682 and d2- = 1.667) is

tangible even to the untrained ear. This is one of the

principal reasons for the departure from normalcy that a

Western ear finds in Indian music.

Dhira-Shankarabharanam and Natha-Bhairavi respectively,

of Carnatic music (or Bilaval and Asaavari respectively, of

Hindustani music). The Dorian and Phrygian Greek modes

correspond to the scales Khara-Harapriya and Hanuma-todi

respectively, of Indian music. The Hungarian minor scale

corresponds to the scale Simhendra-Madhyama of Indian

music, while the pentatonic scale of Chinese and Mongolian

music corresponds to the aforementioned Mohana.

In addition to septatonic scales, Indian music also employs

pentatonic (5-note) and hexatonic (6-note) scales, in addition

to scales having five notes in the ascent and six in the

descent, and so forth. The scalar diversity of Indian music is

truly limitless.

Consonance

A consequence of the seemingly curious division of the

Indian octave is the high degree of consonance it affords.

Consonance is the experience of listening to a series of notes

whose frequencies are simple fractions. The relative

frequencies of all the notes of Indian music are rational

numbers, and can hence be expressed as fractions (in

contrast to the frequencies of the notes of the Western

equitempered scale which are irrational numbers). As an

example, the notes used while performing the raga Mohana

(Hindustani Bhoop) are sa (=1), ri2- (=10/9), ga2- (=5/4), pa

(=3/2) and dha2- (=5/3). Being the ratios of small integers,

these notes, when produced in sequence, produce a very

consonant or pleasing effect. This is a special attribute of

Indian music.

Gamaka-s and Ornamentation

In Indian music, notes are seldom rendered straight, but are

rendered with ornamentations such as glides, oscillations,

bends, stresses, accents [6,7]. These embellishments are

collectively known as gamaka-s (graces).

An example of a gamaka is illustrated in Figure 2, which

shows the typical method of playing the phrase pa-ma-paga in the raga Kanada. While the notes p and m are

rendered straight, the note ga (g1) is oscillated between ri

(r2) and ma (m1) as amplitudes. The oscillation is

continuous, i.e. all the frequencies from g1 through r2

through m1, and back to g1, are traversed within one time

unit. It is also made sure that the oscillations terminate at g1,

so as not to inadvertently reveal the nature of any other note.

This gamaka is known as kampita (oscillatory) or andolita

(swinging) gamaka. Readers familiar with the compositions

Sukhi Evvaro (Thyagaraja) or the celebrated Alaipayude in

the raga Kanada, would recall a phrase ri-pa-ga where ga

is oscillated just as explained above.

Consonance can produce a very exhilarating effect, when the

product of the frequencies of the notes of taken by a raga is

an integer. The raga Madhyamavathi utilizes five notes,

whose frequencies when multiplied, give the integer 4. This

makes Madhyamavathi a combination of notes so exclusive,

that no other sequence or combination of notes can produce

the same finality of effect. Small wonder then, that this raga

is almost always used to end a performance!

Gamakas confer melodic individuality to the raga that they

are part of. They are the lifeblood of Indian classical music,

and stand out as marks of its acoustic excellence.

Variety of Scales

Indian music is known for its wide variety of scales. The

most common type of scale (in any genre of music) is a

septatonic scale, consisting of seven notes. In Western

music, the sequence of notes {C, D, E, F, G, A, B }

constitutes the major scale. By flattening three notes of the

scale, we obtain the combination {C, D, Eb, F, G, Ab, Bb},

known as the natural minor scale. In this fashion, a number

of septatonic scales can be obtained. However, the number

of such scales in Western music is limited. (Including the

ancient Greek modes, the number of scales used is about

ten.) Indian music, however, has made use of all

combinations of seven notes, and uses 72 septatonic scales.

Violinist Yehudi Menuhin has expressed his wonder at the

variety of scales in Indian music in his autobiography: I

found vindication of my conviction that India was the

original source. The two scales of the West, major and

minor, with the harmonic minor as variant, the half-dozen

ancient Greek modes, were here submerged under modes

and scales of (it seemed) inexhaustible variety [5].

Figure 2: Approximate graphical depiction of the rendition

of the phrase pa-ma-pa-ga in the raga Kanada.

Scales found in the music of almost every region of the

world are found in Indian music. For example, the major and

minor scales described above correspond to the scales

Melodic Basis

Another fundamental aspect of Indian music is that it is

primarily based on melody, and does not generally allow for

(vertical) harmony, which is ubiquitous in Western music.

Vertical harmony is the process of playing multiple notes at

the same time (as in a chord), thus creating an agreeable

combination of sounds. Examples of harmony are abundant

in the compositions of Mozart and Beethoven.

(Continued on page 8)

Lok-Nritya: Folk Dances of India

them in a circle using their hands to rhythmically clap to the

beat.

Rohini Ramaswamy

The best known of the folk dances from Tamil Nadu is the

Kollatam. Similar to Ras it is danced in a circle, but a single

one in this case, to the beat of sticks held by the dancers and

struck to together in time to the music. This is danced

primarily by the women, and there is a more interesting

though less frequently seen version called a Pinnal kollatam

where the women dance back and forth in the circle, in a

more complicated, in order to weave a giant braid of ribbons

from a cluster suspended overhead. The Kummi is another

dance from Tamil Nadu, which is also danced by women in

circles, where they clap and pound the spices in the course

of the dance. It probably originated as a way to keep them

from getting bored from the monotony of pounding, by

keeping them entertained with song and dance. The

Bhagavat mela nataka and the Kuravanji are two other folk

dances from Tamil Nadu. They are dance dramas, the former

usually of Vaishnavite themes about the reincarnation of

Vishnu, from the Bhagavat Purana, danced in a

predominantly Kuchipudi style but with the non dance

interludes in Tamil, and the latter is a drama about a gypsy

fortune teller and the fortunes told by her to forlorn lovers.

No mention of Folk dance in Tamil Nadu is complete with

talking at least briefly about the Theru Koothu and the

Poikalkuthirai. In the case of the former, originating as street

plays, literally, they were used to primarily depict stories

from mythology and the epics to the common folk in a

language and manner that would be understandable and

would capture and hold their attention. This is one form

though that has shown itself to be very adaptable and

capable of growing and is now beginning to incorporate

more modern, political, social and educational themes into

its repertoire. The latter, is also a form of street theatre. The

dancers wear a costume to simulate the torso of a horse and

wear shortened stilt like dummy legs and dance.

Rohini, the backbone of SiTaR, is a graduate student in

Economics at Iowa State University and has contributed

tremendously to SiTaR, including a year as President. She is

ardently interested in dance. Having been trained in Bharata

Natyam for a number of years, she is also exploring other

dance forms such as Ballroom, Jazz and Tap. In this article,

she shares information about Indian folk dances.

Dance is a divine creation, relating back to Shiva as

Nataraja, dancing the tandava, accompanied by his consort

Parvati, dancing the graceful feminine lasya aspects,

according to the Hindu Shastras. Dancing is a way of

expressing ones self, ones emotions through movement; it is

poetry in motion set to melodious music.

Much is said and written about Indian Classical dances, but

relatively little is said about their more common and

accessible cousin, folk dance. India has a culture and

tradition rich in folk arts of all kinds and especially folk

dance. For all that is said and written about our Classical

dances, it is our folk dances that are truly of the people.

Every village and every town in India will celebrate with

their own folk dances, regardless of the occasion they are

celebrating, be it a festival or the season, the harvest, or the

coming of the monsoons, or a happy occasion, a birth, a

wedding, a visitor, or a sad occasion, a death, be it to

propitiate the gods or to appease them or just to celebrate

them, and most of all to give thanks to them.

There are many kinds of folk dances, each region and state

and community have their own. Many festivals and

occasions have their own. They are all without exception,

spectacular, most are also colourful, extravagant and joyous.

While all of them are incredibly unique and special in their

own way, a few stand out even in this exalted crowd. Dances

from two parts of India closest to my heart are those from

Gujarat and Tamil Nadu as they are a part of my personal

heritage.

The Bhangra from Punjab is, like the Ras one of the bestknown and recognized forms of folk dance in India. Usually

danced by the men, this was originally a harvest dance, but

is now used at any celebratory or happy occasion. Its is a

vigorous, energetic and colourful dance with many

movements and improvisations, high jumps and low

squatting steps, to boisterous music, couplets recited by the

participants, and the heavy beat of drums, truly a dance to

heat up your blood and get your adrenaline flowing. The

men of Punjab also dance the Jhumer. It is, like most

Punjabi folk dances, very energetic, and is a circular dance

with sticks with an increasing tempo and many

accompanying shouts. The Gidha of Punjab is performed by

the women in a group with individual dancers or pairs often

breaking away for a short cameo to the accompaniment of

claps from the others.

Gujarat has probably the best-known Indian Folk dance, the

Dandiya Ras. Danced by both men and women, usually in

two concentric circles with two sticks or dandiyas that are

struck together or against a partners in time to the rhythm,

the Ras is an extravaganza of flowing bodies snaking back

and forth and side to side, of striking sticks, bright swirling

skirts, whirling figures and lighting quick feet. Usually

associated with the festival of Navratri in the early fall,

Gujaratis in every village and major town in Gujarat get

together every night for those nine days to dance the night

away in joyous celebration. It is a quintessential Indian folk

dance combining the colour and spectacle and vigour and

joy and sense of celebration that characterizes them at their

best. The Garba, also from Gujarat is a gentler dance, more

evocative of the lasya elements. Perforated pots with a light

inside them symbolizing the primeval energy or the goddess

Durga are placed in the center and the women dance around

The Chhau of Bihar and West Bengal is folk dance that

blends the tribal and Hindu elements of the society from

which it originates. It is a vibrant, vital, colourful and

enthralling dance drama that enacts events from the Indian

epics using dance, acrobatic movements, exaggerated

postures and dramatized gestures, all complimented by

forms to reach out to the people with modern, politically and

socio-economically relevant themes, in an effort to educate

the people and help India develop both economically and

socially.

colourful costumes and fantastic masks. The dance is

performed by the men, in rhythm to loud drumbeats. Sattra

Dances of Assam originated in the Brahmaputra Valley

region. Most of these dance drama were written by the

founder of the dance, and portrayed scenes from the life of

Radha and Krishna, with a key role being played by the

sutradhaar or narrator. The dance style itself reflects much

of the existing styles in the region in the 16th Century.

With a country as rich and diverse as ours in all aspects of

art and culture including folk and performing arts, it is not

possible to cover all the various kind, or even all the regions

in a single article, so I have done my best to cover a sample

medley of the dances from across the country to provide a

flavour, a fragrance, a glimpse of the vital, vibrant, colourful

and contrasting blur, that is the tradition of Folk Dance in

India.

The Ghoomer is danced by the women of Rajasthan, in a

circle, with graceful movements of the hands and arms and

frequent whirling patterns or pirouettes, which give it its

name. The dance is dedicated to Parvati and performed

during festivals and other joyous occasions. The Dumhal of

Kashmir is danced by the men, in long colourful robes. They

dance in a circle around a ceremonial banner to the

accompaniment of drums and the singing of the participants.

The Rouff on the other hand is danced by the women of

Kashmir; often arm in arm, in their colourful costumes and

headdress, with simple footwork.

Why Carnatic Music

(Continued from page 3)

Both the ability of music to build and release tension, as well

as its potential to unlock latent energies in the mind are

respected and developed. When discussing lofty ideas with

people, there are often various mental blocks, which must be

overcome, and knowing the way around them gracefully is a

large part of the art of teaching. With its rich variety of

ragas, Carnatic music provides a nearly limitless array of

melodic patterns, which can be used to effect this navigation

under a variety of circumstances. Together with a system for

organizing them, these melodies make it possible to clear the

mind of obstacles. It is no coincidence that the kucheri

traditionally begins with a song on Ganesha, and the same

concept may be extended to include the audience's

apprehension in general.

The Yakshagana of Karnataka depicts episodes associated

with the Puranas, the Ramayana and Mahabharatha with

songs called prasangas, dance and dialogue that often vary

from performer to performer. The name itself is derived

from yaksha or the demi-gods associated with Kubera the

heavenly treasurer. Ottan Tullal of Kerala is, unlike most

folk dances in India, usually a one-man show. The sole

performer plays all the parts, similar to most Indian classical

dances, and is accompanied by one drummer. The style of

dancing is similar to Kathakali, but less stylized and rigid.

The Kummi of Kerala is performed especially during the

festival Onam, by women dressed in the traditional white

Kerala saris. It is similar to the Kummi of Tamil Nadu,

except that the dancers use flowers as a part of the dance, or

sometimes even lit diyas or lamps.

To return decisively to the opening question, I value

Carnatic music first for the effectiveness with which it can

build positive mental discipline. It helps me to focus and

organize my thoughts, and it helps to eliminate negative

mental habits. How does it do this? Of course, I do not really

know. However, I do claim that music naturally illustrates

patterns of thought, and in the case of the great composers of

Carnatic music, these mental patterns have been effectively

conveyed at the highest level. I am personally attracted to

Muthuswamy Dikshitar more than the others. One challenge

for Carnatic music is to continue to meet the demands of

modern times, especially as the basis for communication

with the audience changes. Modern composers have

continued admirably in this regard, although the pace of

change for the younger audience will be much faster, and the

act of composition may need to adapt accordingly.

Two other ancient and still very popular folk dance forms

are the Ram Lila and Ras Lila of Uttar Pradesh and Bihar.

Essentially, these are stylized dance dramas in Hindi, the

former depicting scenes from the Ramayana about the life of

Rama and the latter depicting scenes from the life of

Krishna. Performed across much of the Hindi speaking

regions of Northern India, these dance drama forms tell the

stories from Hindu mythology to the lay public. A form of

folk dance drama also seen across much of India is the

Nautanki, and like the Theru Koothu of Tamil Nadu, though

originally was used for the depiction of mythological and

historical events, has now lent itself beautifully to the

depiction of more relevant contemporary political and socioeconomics themes. The Tamasha, another folk drama form

with a wide performance area, began, it is believed, as

entertainment for the Mughal troops stationed in the Deccan,

and is typical of satirical rural theatre. Performances often

have a strong flavour of Kathak and ghazals among others.

Even as its range expands, Carnatic music will continue to

communicate the highest ideals, and many people around the

world will be listening. There will be more interaction with

other traditions, but there is also an audience for the strictest

styles in the West. Carnatic music is one of the world's great

treasures. I am honored to have been associated with it in

some small way, and to have had the opportunity to write

this article.

There are many other tribal and community specific folk

dances in India. Most of the tribal communities of North

East and Central India have their own festive and religious

dances and dances dramas. Recently we have also seen a

renewed interest in the used of more accessible folk art

This article is reprinted from Keertana, the newsletter of the

Carnatic Music Circle Melbourne, Australia.

Distinguishing Features of Indian Classical

Music

Upcoming SiTaR event

(Continued from page 5)

However, Indian music offers horizontal harmony, in the

form of octave harmony (playing the same melodic music in

different octaves) and drone harmony (accompaniment by a

drone or tanpura) [8]. Then again, it suffices to say that the

phenomenon of consonance discussed earlier, more than

compensates for the absence of vertical harmony in Indian

music.

An Evening of Indian Classical Music

Closing Remarks

This article has reviewed some of the aspects, which make

Indian classical music distinctive, including the unique pitch

intervals, the remarkable scalar diversity, the presence of

ornamentation in the form of gamakas, and the melodic

nature of this music. Although beyond the scope of this

article, it must be mentioned parenthetically, that Indian

music also offers the performer unlimited freedom of

extempore improvisation, and incredible rhythmic variety.

All these facets together constitute the aesthetic splendor of

Indian classical music.

featuring

Rajeev Taranath

Distinguished disciple of Maestro Ali Akbar Khan

and recipient of the prestigious

Sangeet Natak Academy Award

on the Sarod

and Swapan Chowdhary

on the Tabla

References and Suggested Further Reading

7th April 2002

Time and venue to be announced

1. Carnatica.com Sangeetanubhava section,

http://www.carnatica.com/sang-main.htm

2. See for example, a University of Geneva website:

http://tecfa.unige.ch/tecfa/teaching/UVLibre/9899/mar005/

welcome.htm

3. Shankar, Vidya. The Art and Science of Carnatic Music.

The Music Academy, Madras, 1983.

4. Bhagyalekshmy, S. Ragas in Carnatic Music. CBH

Publications, Trivandrum, 1990.

5. Menuhin, Y. Unfinished Journey. Macdonald and Janes,

London, 1976.

6. Sambamurthy, P. South Indian Music, Vol. I-VI. The

Indian Music Publishing House, Chennai, 1982

7. Favilla, S., J. Cannon, E. Dalgeish and S. Brown.

Nonlinear control mapping for the gestural control of

gamaka. Proc. 1996 Int. Computer Conf., 1996.

8. MusicIndiaOnline.com,

http://www.bharath.com/mio/html/carnatic.shtml

SiTaR events activities in the past year

River Rites

06 October 2001

Fisher Theater, Iowa State Center

Co-hosted with Sankalp

A dance ballet by Aparna Sindhoor and troupe,

incorporating elements of Indian classical and folk

dance to depict the plight of the tribals affected by

the Narmada river valley projects.

Chitraveena Recital

24 March 2001

130, S. Sheldon

Co-hosted with ICA

A recital of Indian classical (Carnatic) music that

featured the maestro Chitraveena N. Ravikiran on

Chitraveena, and Rohan Krishnamurthy on

Mridangam.

Contributions in the form of articles, photographs,

recipes or any other information are welcome from

interested readers and writers.

For volunteering, membership details or any other

information, contact us at sitarexec@iastate.edu

Tirangaa

A radio show featuring Indian classical and popular

music, aired on 88.5 FM KURE every Sunday from

2-4 pm.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the efforts of the authors, and of

Amit Singh, Ravi Vasikarla and Sandhya Bhagavatula

in bringing out this edition of Patrika. Editor

SiTaR is funded by GSB

Patrika is a magazine published by SiTaR (Society of Indian Tradition and ARts) from Iowa State University, Ames, Iowa. The views

and opinions expressed in the articles are the authors own and do not represent the opinion of the editorial board of Patrika or of SiTaR.

You might also like

- We Are One Body - Dana ScallonDocument4 pagesWe Are One Body - Dana Scallonmathman16680% (5)

- Thinking Musically 1 - WadeDocument16 pagesThinking Musically 1 - WadeJosh Ho100% (5)

- Joe Pass - Summertime (Live 1992)Document16 pagesJoe Pass - Summertime (Live 1992)julianus51No ratings yet

- Lee Browe - The Brower QuadrantDocument40 pagesLee Browe - The Brower QuadrantCristian Catalina50% (2)

- Khayal Darpan...... (Final 1)Document5 pagesKhayal Darpan...... (Final 1)Bilal ShahidNo ratings yet

- Ascolta Leggi Suona Tromba CD PDFDocument5 pagesAscolta Leggi Suona Tromba CD PDFFrancesco CapocottaNo ratings yet

- Skyrim - The City Gates - Sheet MusicDocument2 pagesSkyrim - The City Gates - Sheet Musicablindman2100% (1)

- Ornamentation and Improvisation in Mozart., Frederick NeumannDocument6 pagesOrnamentation and Improvisation in Mozart., Frederick NeumannPatricia ŽudetićNo ratings yet

- Dissertation Topics in Carnatic MusicDocument8 pagesDissertation Topics in Carnatic MusicPayToWritePaperSingapore100% (1)

- Music Is Life - November 2007Document3 pagesMusic Is Life - November 2007ARKA DATTANo ratings yet

- International Vs Traditional Music (IELTS Writing Task)Document1 pageInternational Vs Traditional Music (IELTS Writing Task)nur adlim yuvinaNo ratings yet

- Problems Relating To Hindustani MusicDocument6 pagesProblems Relating To Hindustani MusicVinay GadekarNo ratings yet

- Culture and Music Miller-ShahriariDocument17 pagesCulture and Music Miller-ShahriariJoseph MwangiNo ratings yet

- Some Indian Conceptions of Music Maud Mann Vol 38Document26 pagesSome Indian Conceptions of Music Maud Mann Vol 38Vijay SANo ratings yet

- Research Paper On Folk MusicDocument7 pagesResearch Paper On Folk Musicj0lemetalim2100% (1)

- Musicology Research Paper TopicsDocument5 pagesMusicology Research Paper Topicsgz9g97ha100% (1)

- A Conversation With: Jazz Pianist Vijay Iyer - The New York TimesDocument5 pagesA Conversation With: Jazz Pianist Vijay Iyer - The New York TimesPietreSonoreNo ratings yet

- Research Paper On Country MusicDocument6 pagesResearch Paper On Country Musicafedyvlyj100% (1)

- Native American Music Research PaperDocument8 pagesNative American Music Research Paperegx2asvt100% (1)

- Weidman (2003) - Gender and The Politics of Voice - Colonial Modernity and Classical Music in South IndiaDocument40 pagesWeidman (2003) - Gender and The Politics of Voice - Colonial Modernity and Classical Music in South IndiaTyler GuthrieNo ratings yet

- TRIMILLOS - Hálau, Hochschule, Maystro, and Ryú - Cultural Approaches To Music Learning and TeachingDocument11 pagesTRIMILLOS - Hálau, Hochschule, Maystro, and Ryú - Cultural Approaches To Music Learning and TeachinggustavofukudaNo ratings yet

- Writing Task 2 Essay 1Document4 pagesWriting Task 2 Essay 1jemuelNo ratings yet

- Gender and The Politics of VoiceDocument40 pagesGender and The Politics of VoiceAnoshaNo ratings yet

- Composers and Tradition in Karnatic MusicDocument11 pagesComposers and Tradition in Karnatic Musicgnaa100% (1)

- Hawk Project PaperDocument76 pagesHawk Project PaperPatrizia MandolinoNo ratings yet

- Senior Paper Rough DraftDocument9 pagesSenior Paper Rough Draftapi-512339455No ratings yet

- The Idealization of Indian MusicDocument11 pagesThe Idealization of Indian MusicxNo ratings yet

- Research Paper Topics About Country MusicDocument8 pagesResearch Paper Topics About Country Musicfyme1xqc100% (1)

- Morangelli - Jazz A Short HistoryDocument50 pagesMorangelli - Jazz A Short HistoryCANYAHAN100% (1)

- Music and Life: A study of the relations between ourselves and musicFrom EverandMusic and Life: A study of the relations between ourselves and musicNo ratings yet

- Role & Training of Musician...Document11 pagesRole & Training of Musician...Ademola AdedejiNo ratings yet

- Music As Yoga by Swami SivanandaDocument124 pagesMusic As Yoga by Swami Sivanandakartikscribd100% (8)

- An Introduction to Hindustani Classical Music: A Beginners GuideFrom EverandAn Introduction to Hindustani Classical Music: A Beginners GuideNo ratings yet

- PHD Dissertation TopicsDocument15 pagesPHD Dissertation TopicsKristine Mercy Regaspi Ramirez-VelascoNo ratings yet

- 10 Hawley John - 1984 - Bhakti and MusicDocument21 pages10 Hawley John - 1984 - Bhakti and MusicjgfjhmjNo ratings yet

- Music and Social Change in South AfricaDocument240 pagesMusic and Social Change in South AfricaGarvey Lives100% (1)

- Dane Rudhyar - The Transforming Power of ToneDocument6 pagesDane Rudhyar - The Transforming Power of ToneMD POL0% (1)

- Adowa Funeral Dance of AsanteDocument44 pagesAdowa Funeral Dance of AsanteFrancesco MartinelliNo ratings yet

- MUS 009 Exam 1 StudyDocument71 pagesMUS 009 Exam 1 StudyNate LisbinNo ratings yet

- The Rebirth of Hindu MusicDocument58 pagesThe Rebirth of Hindu MusicAnahiti Atena100% (1)

- Drums and Drummers HerskovitsDocument18 pagesDrums and Drummers HerskovitsHeitor ZaghettoNo ratings yet

- Strategies For Classical Music Audiences - An Exploration of ExistDocument101 pagesStrategies For Classical Music Audiences - An Exploration of ExistgilbertbernadoNo ratings yet

- MusicAndEducationInIndia CoomaraswamyDocument8 pagesMusicAndEducationInIndia Coomaraswamyruchir.anand.175No ratings yet

- Jeremy Woodruff CarnaticDocument17 pagesJeremy Woodruff CarnaticmohanongcNo ratings yet

- Country Music Research Paper ThesisDocument7 pagesCountry Music Research Paper Thesisafmbvvkxy100% (1)

- All These Things into Position: What Theology Can Learn From RadioheadFrom EverandAll These Things into Position: What Theology Can Learn From RadioheadNo ratings yet

- Qawwali Routes Notes On A Sufi Musics TransformatDocument16 pagesQawwali Routes Notes On A Sufi Musics Transformatheoharu1922No ratings yet

- Khoi SanMUSDocument27 pagesKhoi SanMUSlyndi beyersNo ratings yet

- Music Reaserch BBADocument53 pagesMusic Reaserch BBAMukesh SharmaNo ratings yet

- Music Research Paper ExampleDocument6 pagesMusic Research Paper Examplem1dyhuh1jud2100% (1)

- For Every Music Lover: A Series of Practical Essays on MusicFrom EverandFor Every Music Lover: A Series of Practical Essays on MusicNo ratings yet

- Classical Music GharanafDocument355 pagesClassical Music Gharanafvinaygvm0% (1)

- Taking It to the Streets: Using the Arts to Transform Your CommunityFrom EverandTaking It to the Streets: Using the Arts to Transform Your CommunityRating: 2 out of 5 stars2/5 (1)

- International Council For Traditional MusicDocument7 pagesInternational Council For Traditional MusicArastoo MihanNo ratings yet

- Improvisation in Scottish Traditional Music Edited - 0Document24 pagesImprovisation in Scottish Traditional Music Edited - 0Chris WrightNo ratings yet

- Music LiteracyDocument6 pagesMusic LiteracyJenitza QuiñonesNo ratings yet

- Music and QuadriviumDocument2 pagesMusic and QuadriviumFilipehenriqueNo ratings yet

- Research Paper EthnomusicologyDocument8 pagesResearch Paper Ethnomusicologygz7veyrh100% (1)

- Performed Through Dance Movements, Frequently With: Drama DialogueDocument6 pagesPerformed Through Dance Movements, Frequently With: Drama DialogueDivya VipinNo ratings yet

- Music 1Document3 pagesMusic 1Alin KechikNo ratings yet

- That Lucky Old SunDocument18 pagesThat Lucky Old SunVini LacerdaNo ratings yet

- Bethany Wherry - Resume Website VersionDocument5 pagesBethany Wherry - Resume Website Versionapi-214697152No ratings yet

- SPIELSDocument4 pagesSPIELSDhong ZamoraNo ratings yet

- Samsung PS42C430 PS42B450B PS50B450B PS42B451B PS50B451B (TM)Document55 pagesSamsung PS42C430 PS42B450B PS50B450B PS42B451B PS50B451B (TM)socket1155No ratings yet

- "Personality Rights" and Why Mars Argo Has A CaseDocument5 pages"Personality Rights" and Why Mars Argo Has A CaseDangeresque MustachioNo ratings yet

- Frankenstein: Frankenstein Or, The Modern PrometheusDocument18 pagesFrankenstein: Frankenstein Or, The Modern PrometheusJ.B. BuiNo ratings yet

- mc24 PROFI-ROMDocument43 pagesmc24 PROFI-ROMGerard Paul LawsonNo ratings yet

- Kord Gitar Mengejar MatahariDocument5 pagesKord Gitar Mengejar MatahariFina MardiyantiNo ratings yet

- What Is RTWPDocument8 pagesWhat Is RTWPZia Ul Haq AliNo ratings yet

- 15EC35 - Electronic Instrumentation - Module 4Document33 pages15EC35 - Electronic Instrumentation - Module 4Anish AnniNo ratings yet

- Taxi Driver AnalysisDocument5 pagesTaxi Driver AnalysisRamanathan IyerNo ratings yet

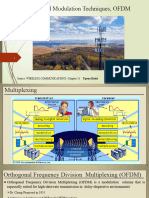

- EE-480 Wireless Communications Week 9: Dr. Sajjad Shami Eed SST UMT LahoreDocument25 pagesEE-480 Wireless Communications Week 9: Dr. Sajjad Shami Eed SST UMT LahoreM Usman RiazNo ratings yet

- Antenna Gps Ok-Ok 59319Document1 pageAntenna Gps Ok-Ok 59319Alejandro ViqueNo ratings yet

- 5G New Radio - Explained in A NutshellDocument11 pages5G New Radio - Explained in A NutshellaliEsswieNo ratings yet

- Pa1000 User Manual v15 EDocument1,080 pagesPa1000 User Manual v15 EAnh ĐườngNo ratings yet

- Unit 8Document28 pagesUnit 8baidnirvana8No ratings yet

- Superdelay Vintage LandscapeDocument1 pageSuperdelay Vintage LandscapeI.M.C.No ratings yet

- ASR 1fDocument4 pagesASR 1fMadison MadisonNo ratings yet

- Black Sabbath: Tony Iommi's Guitar SoloDocument2 pagesBlack Sabbath: Tony Iommi's Guitar SoloJavier NoelNo ratings yet

- Berklee Harmony ReviewDocument13 pagesBerklee Harmony ReviewulgenyNo ratings yet

- TA7613AP Linear Integrated Circuit: I-Chip Am/Fm Radio IcDocument4 pagesTA7613AP Linear Integrated Circuit: I-Chip Am/Fm Radio Icdj4fjNo ratings yet

- Modern Family S04e07 PDFDocument5 pagesModern Family S04e07 PDFlucasfoltzNo ratings yet

- Gulf of Aden War Ship Battle StargateDocument80 pagesGulf of Aden War Ship Battle StargateVincent J. CataldiNo ratings yet

- Service Manual: Cfd-Rs60CpDocument68 pagesService Manual: Cfd-Rs60CpMy shop CoolNo ratings yet