Professional Documents

Culture Documents

The Ansel Adams of The Sky: Star Trails

The Ansel Adams of The Sky: Star Trails

Uploaded by

birbiburbiOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

The Ansel Adams of The Sky: Star Trails

The Ansel Adams of The Sky: Star Trails

Uploaded by

birbiburbiCopyright:

Available Formats

The Ansel Adams of the Sky

he Orion Nebula, M42, is a hot,

violent place, says David F. Malin, arguably the best-known astrophotographer in the world today, from

his office at the Anglo-Australian Observatory (AAO) in Siding Spring, New South

Wales. It has a Dantes Inferno feel to it.

One of the most beautiful sights in the

night sky, M42 is also one of the most

challenging to photograph. It has a lot of

detail that doesnt appear in ordinary

images, Malin explains. It gives you a

hint about the complex, three-dimensional structure of the nebula. It is Malins careful attention to that extra level

of exquisite detail that separates his work

from the ordinary. In addition to many

books, his photographs have graced virtually every major astronomical magazine published in the last 10 years, including this one see Icko Ibens article

starting on page 36.

I wish Id been into astronomy 10

years earlier, Malin says. With the rise of

CCDs, the 1970s were the beginning of

the twilight years for astrophotography.

But that is the decade that brought

Malin to the sky. Although he had a

strong general interest in science and

technology from his youth, he ventured

into the world of astronomy as a complete novice. I thought right ascension,

he chimes, was a religious group!

Malins early interest was chemistry,

not astronomy. Born in England in 1941,

his first major scientific experience was

with the chemical firm Ciba-Geigy,

where he ran a section concerned with

microscopic observations. I studied the

way chemical changes happened on

small scales and recorded the results

photographically, he notes. This was the

start of his lifelong passion for imaging.

By the early 1960s, Bart Bok, the great

Milky Way astronomer, had convinced the

Australian government of the need for a

world-class telescope in the Southern

Hemisphere. The result was the AAOs

ANGLO-AUSTRALIAN TELESCOPE BOARD

COPYRIGHT 1992, ANGLO-AUSTRALIAN TELESCOPE BOARD

star trails By David H. Levy

3.9-meter telescope. Malin was hired as

photographic scientist-astronomer for the

new observatory. Shortly after the facility

opened in 1975, Malin arrived with his

wife, Phillipa, son, James (now 26), and

twins, Sara and Jenny (now 24).

Having the responsibility for setting up

darkroom facilities at the observatorys

Sydney laboratory (where he spends most

of his time) and at the telescope site in

the outback 480 kilometers away, Malin

brought to his work a zest for developing

entirely new techniques in astrophotography. By 1979 he had invented an entirely

new process called photographic amplification. By contact-printing the original

plate with a diffuse light source instead of

a distant point-light source, he was able

to bring out details in objects that ordinary exposures couldnt record. Malin

applies the amplification process mainly

to black-and-white photography, which

he finds artistically more stimulating

than color.

With black-and-white, the photographer has more control over the process

than with color, he says. You can create

the image in the darkroom. With color, all

you can do is record the image. Malins

current scientific effort is compiling an

atlas of nearby bright galaxies like the magnificent M83 in Hydra. Each image will be

the mosaic of many individual plates.

Malin builds his images like a celestial

Ansel Adams, who brought the natural

world into the darkroom and emerged

with stunning works of art. While Adamss work focused mainly on various

landforms, he also used the sky to enhance the landscape, like his famous picture Moonrise, Hernandez, New Mexico

(S&T: November 1991, page 480). Malin

uses the giant Anglo-Australian telescope

to capture the sky, object by object.

There is a difference: Adams could

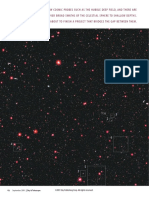

Above: Among the myriad deep-sky gems recorded by world-renowned astrophotographer

David Malin with the Anglo-Australian Observatorys 3.9-meter reflector, perhaps none is more

surreal than this portrait of CG 4, a cometlike molecular cloud 1,300 light-years away in the constellation Puppis. The nebulas head, which spans roughly 112 light-years, seems ready to devour the vastly more distant edge-on galaxy to its left (S&T: July 1993, page 36). Right: Malin

seated inside the prime-focus cage of the 3.9-meter reflector while the telescope is pointed low

toward the northern horizon.

1997 Sky Publishing Corp. All rights reserved.

Sky & Telescope December 1997

85

Advertisement

move his camera, positioning it to capture the right scene at the right time of

day and in the right weather. For a celestial shooter like Malin, the spinning

Earth is his camera mount. In fact, he

did not take the originals of any of the

UK Schmidt plates he uses and has never

actually observed with that telescope. Instead, he makes photographs in the darkroom from plates that other people have

exposed. With the mighty Anglo-Australian telescope, however, Malin himself

exposed most of the images he uses.

For Malin, like Adams, the creative

process reaches its peak in the darkroom.

The creation of an image is the technical

challenge, he says, and much of it is

done in the laboratory before and after

the telescope exposure, manipulating the

resulting black-and-white images to extract the most information. Malins goal

is to build an image so that it expresses

something meaningful to him without

distorting the subjects relationship to the

natural world. To obtain his vivid colors,

Malin combines three separate black-andwhite images taken through red, green,

and blue filters. He then combines them

to a positive film in the darkroom to produce a true-color image.

Another aspect of Malins creativeness

explores subtle features within the

brighter parts of an image. To do this,

Malin perfected the technique of unsharp

masking, a darkroom process that reveals

delicate, low-contrast structures. He first

makes a slightly out-of-focus positivefilm copy and then aligns the copy precisely with the original. In the resulting

print, subtle features stand out without

overexposing the brighter regions.

The public side of Malins life includes

a hectic schedule of up to 50 public lectures a year. I consider this time well

spent, he admits. It is important for astronomers to tell about what they do,

why they do it, and what they learn.

Aware that in the paranoid age we live

in, some people see science as a threat,

Malin feels that it is very important to

see science as a liberating, nonthreatening force. With his magnificent photographs now on display in two international exhibitions and in books and

magazines worldwide, Malin has gone a

long way to liberating science.

In his photographic search for comets, author

David Levy has also taken hundreds of exposures using Schmidt cameras from 8 to 18

inches in aperture.

86

December 1997 Sky & Telescope

1997 Sky Publishing Corp. All rights reserved.

You might also like

- Authenticating Vintage NASA PhotographyDocument11 pagesAuthenticating Vintage NASA PhotographyJoseph Wolenski100% (1)

- Earth and Space: Photographs from the Archives of NASAFrom EverandEarth and Space: Photographs from the Archives of NASARating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (6)

- A New Weapon in The War Against Radio Interference: October 1998Document1 pageA New Weapon in The War Against Radio Interference: October 1998birbiburbi100% (1)

- Letters: A Fair PortrayalDocument2 pagesLetters: A Fair PortrayalbirbiburbiNo ratings yet

- The 100 Best Astrophotography Targets: A Monthly Guide for CCD Imaging with Amateur TelescopesFrom EverandThe 100 Best Astrophotography Targets: A Monthly Guide for CCD Imaging with Amateur TelescopesNo ratings yet

- Capturing the Stars: Astrophotography by the MastersFrom EverandCapturing the Stars: Astrophotography by the MastersRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- AstronomyDocument9 pagesAstronomyMuda Sarme0% (1)

- GalleryDocument5 pagesGallerybirbiburbiNo ratings yet

- Letters: Messier Card To The RescueDocument2 pagesLetters: Messier Card To The RescuebirbiburbiNo ratings yet

- Letters: Years AGODocument2 pagesLetters: Years AGObirbiburbiNo ratings yet

- GalleryDocument5 pagesGallerybirbiburbiNo ratings yet

- The Fox Fur Nebula: ImagesDocument2 pagesThe Fox Fur Nebula: ImagesbirbiburbiNo ratings yet

- Celestial Harvest: 300-Plus Showpieces of the Heavens for Telescope Viewing and ContemplationFrom EverandCelestial Harvest: 300-Plus Showpieces of the Heavens for Telescope Viewing and ContemplationRating: 2.5 out of 5 stars2.5/5 (2)

- A Grand and Bold Thing: An Extraordinary New Map of the Universe UsheringFrom EverandA Grand and Bold Thing: An Extraordinary New Map of the Universe UsheringRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (14)

- The 'X' Chronicles Newspaper - January 2003Document43 pagesThe 'X' Chronicles Newspaper - January 2003Rob McConnell100% (2)

- APOD 2023 October 18 - Dust and The Western Veil NebulaDocument1 pageAPOD 2023 October 18 - Dust and The Western Veil NebulatatatataphiriashviliNo ratings yet

- Photographs of Nebulæ and Clusters Made with the Crossley ReflectorFrom EverandPhotographs of Nebulæ and Clusters Made with the Crossley ReflectorNo ratings yet

- Close Up at a Distance: Mapping, Technology, and PoliticsFrom EverandClose Up at a Distance: Mapping, Technology, and PoliticsRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Hasselblad 1969 Moon Landing Press ReleaseDocument13 pagesHasselblad 1969 Moon Landing Press ReleaseMichael ZhangNo ratings yet

- The Hubble Space Telescope: 'It's A Terrific Comeback Story' - Science - The GuardianDocument4 pagesThe Hubble Space Telescope: 'It's A Terrific Comeback Story' - Science - The GuardianlamacarolineNo ratings yet

- The Universe in a Mirror: The Saga of the Hubble Space Telescope and the Visionaries Who Built ItFrom EverandThe Universe in a Mirror: The Saga of the Hubble Space Telescope and the Visionaries Who Built ItRating: 2.5 out of 5 stars2.5/5 (3)

- Moon Landing ConspiracyDocument14 pagesMoon Landing Conspiracyqais yasinNo ratings yet

- Letters: Years AGODocument1 pageLetters: Years AGObirbiburbiNo ratings yet

- Hubble Deep Field: How a Photo Revolutionized Our Understanding of the UniverseFrom EverandHubble Deep Field: How a Photo Revolutionized Our Understanding of the UniverseNo ratings yet

- Letters: Years AGODocument2 pagesLetters: Years AGObirbiburbiNo ratings yet

- GalleryDocument3 pagesGallerybirbiburbiNo ratings yet

- The Hubble Space Telescope: A Universe of New DiscoveryFrom EverandThe Hubble Space Telescope: A Universe of New DiscoveryRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (2)

- Letters: A Sun Pillar That Changed The WorldDocument2 pagesLetters: A Sun Pillar That Changed The WorldbirbiburbiNo ratings yet

- Task Tuesday 19 MarchDocument2 pagesTask Tuesday 19 Marchlauriig1312No ratings yet

- Hubble Space Telescope (HST)Document12 pagesHubble Space Telescope (HST)Myoki CañoNo ratings yet

- GalleryDocument4 pagesGallerybirbiburbiNo ratings yet

- (The Solar System) Sherman Hollar-Astronomy - Understanding The Universe - Rosen Education Service (2011)Document98 pages(The Solar System) Sherman Hollar-Astronomy - Understanding The Universe - Rosen Education Service (2011)Camila Cavalcante100% (2)

- PracticalAstronomy 200910 Oct09Document8 pagesPracticalAstronomy 200910 Oct09changkwNo ratings yet

- Big Astronomy ManualDocument37 pagesBig Astronomy Manualigori76No ratings yet

- News For Kids Black HoleDocument1 pageNews For Kids Black HoleOveja De CerroNo ratings yet

- Astrophysics - (ASO821S) Part 2Document16 pagesAstrophysics - (ASO821S) Part 2yamillakhuruses17No ratings yet

- Was The Apollo Mission FakeDocument12 pagesWas The Apollo Mission FakeSyed Imran Shah100% (3)

- Letters: A Revised HistoryDocument2 pagesLetters: A Revised HistorybirbiburbiNo ratings yet

- Picturing The Cosmos Hubble Space Telescope Images and The Astronomical SublimeDocument289 pagesPicturing The Cosmos Hubble Space Telescope Images and The Astronomical SublimeSugus SNo ratings yet

- 09 Moon Landing - Conspiracy Theories That It's All A Fake - KidsNewsDocument4 pages09 Moon Landing - Conspiracy Theories That It's All A Fake - KidsNewsSIQIAN LIUNo ratings yet

- Ebffiledoc 9211Document48 pagesEbffiledoc 9211ella.jimenez698No ratings yet

- Early History of The Terrestrial PlanetsDocument26 pagesEarly History of The Terrestrial PlanetsNirvaNo ratings yet

- The Mariner 6 and 7 Pictures of MarsDocument173 pagesThe Mariner 6 and 7 Pictures of MarsBob Andrepont100% (4)

- Images: Handbook Describes It As A "Faint CurvedDocument2 pagesImages: Handbook Describes It As A "Faint CurvedbirbiburbiNo ratings yet

- Hubble TheRealmOfTheNebulae TextDocument254 pagesHubble TheRealmOfTheNebulae TextEduardo CordovaNo ratings yet

- 1,001 Celestial Wonders to See Before You Die: The Best Sky Objects for Star GazersFrom Everand1,001 Celestial Wonders to See Before You Die: The Best Sky Objects for Star GazersNo ratings yet

- (Harvard Reprint) Harlow Shapley - Light and Color Variations of Nova Aquilae 1918.4 - (1923)Document2 pages(Harvard Reprint) Harlow Shapley - Light and Color Variations of Nova Aquilae 1918.4 - (1923)P. R. SREENIVASANNo ratings yet

- Celestial FireworksDocument1 pageCelestial FireworkspinocanaveseNo ratings yet

- Hubble's Greatest Hits - NatGeo April 2015 USADocument14 pagesHubble's Greatest Hits - NatGeo April 2015 USAJesús Gerardo Rodríguez Flores100% (1)

- Why Study The Sun?: Arvind BhatnagarDocument20 pagesWhy Study The Sun?: Arvind Bhatnagaraakash30janNo ratings yet

- Your Guide to the 2017 Total Solar EclipseFrom EverandYour Guide to the 2017 Total Solar EclipseRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- GalleryDocument4 pagesGallerybirbiburbiNo ratings yet

- Gallery: Sky & Telescope May 1997 116Document4 pagesGallery: Sky & Telescope May 1997 116birbiburbiNo ratings yet

- Cielo Insolito 3Document34 pagesCielo Insolito 3antoniorios1935-1No ratings yet

- All You Ever Wanted To Know: Books & BeyondDocument3 pagesAll You Ever Wanted To Know: Books & BeyondbirbiburbiNo ratings yet

- Investigating Webring Communities: Astronomy OnlineDocument1 pageInvestigating Webring Communities: Astronomy OnlinebirbiburbiNo ratings yet

- The Fox Fur Nebula: ImagesDocument2 pagesThe Fox Fur Nebula: ImagesbirbiburbiNo ratings yet

- ©2001 Sky Publishing Corp. All Rights Reserved.: September 2001Document4 pages©2001 Sky Publishing Corp. All Rights Reserved.: September 2001birbiburbiNo ratings yet

- Better Solar-Storm Forecasting: 14:27 U.T. 14:59 U.TDocument2 pagesBetter Solar-Storm Forecasting: 14:27 U.T. 14:59 U.TbirbiburbiNo ratings yet

- Taking The: PulseDocument6 pagesTaking The: PulsebirbiburbiNo ratings yet

- Beyond The: HubbleDocument8 pagesBeyond The: HubblebirbiburbiNo ratings yet

- Color CCD Imaging With Luminance Layering: by Robert GendlerDocument4 pagesColor CCD Imaging With Luminance Layering: by Robert GendlerbirbiburbiNo ratings yet

- Visions of Tod: A Globetrotting S of The World's Great Portals To The UniverseDocument8 pagesVisions of Tod: A Globetrotting S of The World's Great Portals To The UniversebirbiburbiNo ratings yet

- Advertisement: Updating The Fate of The UniverseDocument1 pageAdvertisement: Updating The Fate of The UniversebirbiburbiNo ratings yet

- Anatomy of A Whirlpool: ImagesDocument2 pagesAnatomy of A Whirlpool: ImagesbirbiburbiNo ratings yet

- Advertisement: Calendar NotesDocument2 pagesAdvertisement: Calendar NotesbirbiburbiNo ratings yet

- Callisto's Inner Secrets: T: December 1997, Page 50)Document1 pageCallisto's Inner Secrets: T: December 1997, Page 50)birbiburbiNo ratings yet

- Advertisement: Supernova 1987a's Hot Spot Gets HotterDocument1 pageAdvertisement: Supernova 1987a's Hot Spot Gets HotterbirbiburbiNo ratings yet

- The Changing Face of America's Planetariums: ©1998 Sky Publishing Corp. All Rights ReservedDocument1 pageThe Changing Face of America's Planetariums: ©1998 Sky Publishing Corp. All Rights ReservedbirbiburbiNo ratings yet

- A Mushroom in The Milky Way: AdvertisementDocument1 pageA Mushroom in The Milky Way: AdvertisementbirbiburbiNo ratings yet

- The Race To Map The The Race To Map The The Race To Map The The Race To Map The The Race To Map The The Race To Map TheDocument5 pagesThe Race To Map The The Race To Map The The Race To Map The The Race To Map The The Race To Map The The Race To Map ThebirbiburbiNo ratings yet

- GalleryDocument3 pagesGallerybirbiburbiNo ratings yet

- An Enigmatic Nebula Solved: No Vulcanoids Inside Mercury's Orbit - Yet!Document1 pageAn Enigmatic Nebula Solved: No Vulcanoids Inside Mercury's Orbit - Yet!birbiburbiNo ratings yet

- GalleryDocument3 pagesGallerybirbiburbiNo ratings yet

- Astro Imaging With Digital CamerasDocument7 pagesAstro Imaging With Digital CamerasbirbiburbiNo ratings yet

- GalleryDocument3 pagesGallerybirbiburbiNo ratings yet

- Uranus, Neptune, and Pluto This YearDocument2 pagesUranus, Neptune, and Pluto This YearbirbiburbiNo ratings yet

- Intermediate Second Year Physics Blue PrintDocument1 pageIntermediate Second Year Physics Blue PrintVardhani Dhulipudi60% (65)

- Report Full Direct Shear Test Edit Repaired PDFDocument15 pagesReport Full Direct Shear Test Edit Repaired PDFarif daniel muhamaddunNo ratings yet

- AP1 Simple Harmonic Motion Presenter W AnswersDocument33 pagesAP1 Simple Harmonic Motion Presenter W AnswersDamion Mcdowell100% (1)

- VRF DesigningDocument105 pagesVRF DesigningMudassar Idris RautNo ratings yet

- Me 423 Plates No.2 - AircomfanDocument3 pagesMe 423 Plates No.2 - AircomfanNiño Gerard JabagatNo ratings yet

- Electrocoagulation Using Perforated Electrodes - PDF - Physical Sciences - ChemistryDocument11 pagesElectrocoagulation Using Perforated Electrodes - PDF - Physical Sciences - Chemistryدينا رزاق جاسمNo ratings yet

- TLE - SM 11 - w1Document4 pagesTLE - SM 11 - w1CrisTopher L CablaidaNo ratings yet

- U Value Calculator - With Liner Only1Document1 pageU Value Calculator - With Liner Only1muathNo ratings yet

- BookDocument26 pagesBookcoolsatishNo ratings yet

- Science 6.3Document4 pagesScience 6.3Nestlee ArnaizNo ratings yet

- Plasma MembraneDocument61 pagesPlasma Membranechristian josh magtarayoNo ratings yet

- BMP (Class 13) WeldingDocument9 pagesBMP (Class 13) WeldingAsesh PramanikNo ratings yet

- Manual SupelcoDocument12 pagesManual Supelcogrubensam100% (3)

- 13 - Kunz - LADLE REFRACTORIES FOR CLEAN PDFDocument12 pages13 - Kunz - LADLE REFRACTORIES FOR CLEAN PDFemregnesNo ratings yet

- Membrane Structure and FunctionDocument52 pagesMembrane Structure and Functionparrot4000No ratings yet

- Shear StressDocument13 pagesShear StressAsad KhokharNo ratings yet

- Operation and Maintenance Considerations For Oil and Gas SeparatorsDocument2 pagesOperation and Maintenance Considerations For Oil and Gas SeparatorsJatin RamboNo ratings yet

- Key Notes On Chemical Bonding: Crash Course For NEET 2021Document6 pagesKey Notes On Chemical Bonding: Crash Course For NEET 2021thorNo ratings yet

- Photo ResistorsDocument20 pagesPhoto ResistorsRashmi ChaturvediNo ratings yet

- P.E.S. College of Engineering, Mandya - 571 401Document2 pagesP.E.S. College of Engineering, Mandya - 571 401Vikas D NayakNo ratings yet

- Unit 6 Properties of Moist Air: StructureDocument15 pagesUnit 6 Properties of Moist Air: StructurearjunmechsterNo ratings yet

- PHD Thesis Michal Hlobil 2016Document227 pagesPHD Thesis Michal Hlobil 2016saeedhoseiniNo ratings yet

- Chapter 3 ElectrochemistryDocument25 pagesChapter 3 ElectrochemistrySanoopNarayanNo ratings yet

- eAuditNet Proficency Testing (PT) Providers 312019Document2 pageseAuditNet Proficency Testing (PT) Providers 312019viverefeliceNo ratings yet

- Which of The Following Is The Correct Equation For The Net Force Acting On A Submerged ObjectDocument2 pagesWhich of The Following Is The Correct Equation For The Net Force Acting On A Submerged ObjectWaleed El ShirbeenyNo ratings yet

- Physice IX First Term 2020 Paper I A (Answer Key)Document12 pagesPhysice IX First Term 2020 Paper I A (Answer Key)Haseeb MirzaNo ratings yet

- Cpqra Errata SheetDocument2 pagesCpqra Errata SheetNasrulhudaNo ratings yet

- An Investigation Into The Energy Levels of A Free Electron Under The Optical Pumping of RubidiumDocument9 pagesAn Investigation Into The Energy Levels of A Free Electron Under The Optical Pumping of RubidiumJack RankinNo ratings yet

- Recent Progress in Alkaline Water Electrolysis For Hydrogen Production and ApplicationsDocument20 pagesRecent Progress in Alkaline Water Electrolysis For Hydrogen Production and ApplicationsYan Carlos Rodriguez OspinosNo ratings yet