Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Connecting Issues - Art NZ 78 (Autumn 1996)

Connecting Issues - Art NZ 78 (Autumn 1996)

Uploaded by

Christopher BraddockCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Connecting Issues - Art NZ 78 (Autumn 1996)

Connecting Issues - Art NZ 78 (Autumn 1996)

Uploaded by

Christopher BraddockCopyright:

Available Formats

Connecting Issues

Bodies in Question

STEPHEN ZEPKE

Spinoza has supplied us with one of the most

profound theories of the body. He argues that what a

body is, is defined by what a body does. What a body

can do is governed by the nature and limits of its

power of being affected. This power is formed in each

individual through its relations to other bodies,

relations that compose and decompose us: we

experience joy when another body enters composition

with ours, and sadness when another body

decomposes ours. Consequently, it is our ethical

imperative to pursue those connections which bring

us joy and increase our power, to constantly push

what our body can do. The Bodies in Question

symposium, hosted by the University of Auckland's

Art History Department, convened by Hugh

McGuire, Elizabeth Eastmond, Wendy Vaigro, and

Christopher Braddock, was a body of joyful meetings

and exchanges, increasing our knowledge and power.

Bodies in Question, a Symposium Addressing the Body in Aotearoa/

New Zealand Culture: Representations/Uses/Politics, held at the

University of Auckland 23-26November1995

Fleshly Worn, an exhibition co-ordinated by Christopher

Braddock, held at the ASA Gallery, Auckland, 24 November - 14

December, 1995

64

I offer this thou ght from Spinoza partly as retort to

those who charged the symposium's theme was dated

or had somehow been done before. These sniping

bodies, so boring and repetitive, offer a simple

transcendent argument which condemns from above,

refusing to engage, and judging from a pregiven law

of fashion. I hear them only as voices of resentment,

as sad and tired failures to think and have an unique

and exciting experience of 'Bodies'.

The scale of Bodies in Question was large, 76 papers

were presented, and so obviously I was only able to

get to a small fraction. The first paper I took in was

the keynote speech by Ted Gott, the curator of

European Art at the Australian National Gallery (and

my experience of this paper was tempered by the very

reason it was the first I got to; I was preparing my

own paper to be delivered later in the day). So a

certain nervousness animated my body, adding an

appropriate edge to a paper already concerned with

practices and representations taking place on the

'margins' of society. At least so it seemed in the

Auckland City Art Gallery auditorium, in a climate

where entry to exhibitions is restricted, and art is

given the air of pornography by being presented as a

'peep show'. Gott's paper, entitled Sex and the Single

T-Cell: The Taboo of HIV-Positive Sexuality in Australian

Art and Culture was a wide and searching

consideration of Australian art concerning HIV I AIDS,

most specifically various HIV-positive publicity

campaigns, their political fall out, and the

representational strategies they employ.

Gott' s paper moved from a personal celebration of

fuck-bars and HIV-positive friends, to adept criticism

of public health strategies. It offered much in the way

of both information and analysis, always refusing to

slip into pathos or tragedy in response to the AIDS

epidemic, instead celebrating the love and joy evident

in the HIV-positive community.

Two aspects of Gott' s address stood out for me.

First was his astute analysis of the semiotics of

Australian safe-sex poster campaigns, and his

criticism of the government's predictably stupid

moral outrage to photographs of people with AIDS

engaged in sexual activity (how contemptible it is to

deny them the right to pleasure and joy). The

unflinching nature of much of this material was to

make an interesting contrast with safe- sex campaigns

in Aotearoa New Zealand, as they were presented by

Anton Mischewski in his paper Politicising PleasuresDangers or Contingent Possibilities: The (re)presentation

of 'gay' bodies and HIV/AIDS. Our images were

remarkably more demure, and more involved in a

multi- cultural approach, a general observation about

trans- Tasman differences perhaps.

The second delight of Gott's paper was the

comparisons he drew between material produced

from within the HIV I AIDS community, and that from

mainstream gay culture. The comparison was

particularly exciting when applied to pornography:

the humour, pride and general hunkiness of, for want

of a better term, HIV- positive porn, combined turn-on

and tongue-in- cheek- critique. It accepted no pity,

and presented bodies and brains in a way other porn

could do well to emulate. Indeed Gott's sexy paper

similarly combined titillation and stimulation for the

body and brain, making it a most appropriate

response to the theme of the conference, discussing

the contemporary crises of the body with dignity and

humour and contributing an impressive benchmark

for the rest of the conference to aspire to.

We were not to wait long for just such an aspiring

paper. Two and a half hours after Gott's paper Ron

Brownson took to the stage to perform Secret Salvage:

The Unknown Photographs of Theo Schoon. And what a

performance it was! Presenting male nudes by Schoon

which had never been publicly shown before,

Brownson gave us titillation not so much in the

images themselves, which were too brilliantly striking

to be dismissed with a wink and a titter, but in the

way Brownson contextualised them, as evidence for

the classic gay tragi-comedy: 'he only falls in love

with straight men'. And so, in a piece of rhetorical

brilliance, Brownson led us into a world where

Schoon's models 'collaborated' with him in the

making of the photographs. Schoon's seductions

therefore, although supposedly taking place only

through the camera, were nevertheless laced by

Brownson with healthy doses of an unhealthy other,

(opposite above) PETER MADDEN In Site 1995

Mixed media, dimensions variable

(opposite below)Relaxing at the Bodies in Question Symposium

(left to right) Christopher Braddock, Pam ela Zeplin, Miss Fa ncy

Stitchin & Elizabeth Eastmond (Photograph: Pamela Zeplin)

(right) THEO SCHOON Brent Hasselyn, Randwick 1973

Gelatin silver photograph

(Private collection, Auckland)

65

the 'undercover homo' of course, and an associated

Aryan profile lurking beneath the clean-cut army-boy

muscles and refreshingly guileless (but in Brownson's

show, hopelessly suspicious) smiles. That Brownson's

performance allowed us to enjoy indulging such

pathos is surely an excuse worthy of Roger Blackley's

question as to why, if none of Schoon's models were

gay, some of the images Brownson did not show us

contained single men and couples with erections?

Brownson's paper led into and dialogued with

another very impressive contribution, Damien

Skinner's The Native Body in the Photographs of Theo

Schoon . This time Schoon's photos of native Balinese,

and of himself in native Balinese garb, were used to

discuss Schoon's theories of multi-culturalism.

Through challenging readings of the images, and in

discussions of anthropological work carried out by

Gregory Bateson and Margaret Mead in Bali at the

time of Schoon' s childhood there, Skinner was able to

suggest that Schoon embodied and theorised a

cultural strategy which rested on masquerade, not as

a power of simulation, but rather as a valid, energetic

and real engagement with another culture. I look

forward to the MA thesis.

Questions of the body were taken into a very

interesting area in the one dance session I attended.

Dance is a formalised language and strict semiotic

system, both in its forms of expression and in its

performing body. As a distinct art form it requires a

strict regime, an entire disciplinary apparatus, to

produce the body which may write, which may

dance. Dr. Eluned Summers- Bremmer's paper

Reading Irigaray, dancing explored a feminist critique

of dance as a disciplinary and phallocratic institution,

but at the same time attempted to utilise Luce

Irigaray's metaphor of dance, both practically and

theoretically. Dr Summers-Bremmer gestured

gracefully towards ways in which Irigaray's theories

of female fluidity and multiplicity could be used to

inform both a contemporary dance and a

contemporary feminism, which critiqued older

oppressive forms and itself embodied a new female

body.

Having had my eyes so dramatically opened to

dance as an exciting medium, the following paper,

Charles McGuiness' s Depicting the Body on Film,

fascinated them further. McGuiness showed a series

of film and video excerpts which depicted dance, and

explained many of the filmic strategies used. He also,

and this was the guts of the matter, explored the

nature of this embodiment, from body to film,

whereby the translation of dance to film and video

worked to disrupt the languages of each discourse.

Through this process of (mis)translation, which was

also obviously a process of creation, McGuiness was

able to suggest a fascinating confluence of dance and

film and video in the avant- garde. A dancing

technological body.

And lastly, there are all the mentions that I have

run out of space to discuss at length. There were

many artist's talks given as part of the conference, and

66

this was one of its strengths. I particularly enjoyed

those given by Joyce Campbell, Christopher Braddock

and John Cousins. I also met Susan Ballard after I had

missed her paper, but feel convinced by that

experience and other's comments that her paper

Cyborg Theory Fictions of the Body was excellent. Lastly,

I would like to mention the last paper I saw, Catherine

Munro' s The Passionate Body: Art the Act of Becoming.

Having seen a few artist talks in my time I feel

qualified to say that this one was truly amazing. Not

only for the clear and informative way we were lead

into the work, but especially in the brave and

unflinchingly personal nature of the information we

were given. It was as if we, as audience, had become

part of Munro's artistic practice, for that is what the

talk seemed in its power and honesty. You have

created a fan! Courageous and spectacular, Munro's

paper was certainly a fitting end to a fine conference.

The group show entitled Fleshly Worn, was 'coordinated' by Christopher Braddock who invited each

of the 16 artists to make a new work in response to the

title. The show's title obviously invited a wide range

of response, and this was certainly the case. As a body

it was diverse and surprising, both in the work itself,

and in the strange juxtapositions created. My

experience of the exhibition was double and

completely different, first on opening night, and

second, a few days later alone in the gallery.

Opening night was a biggie. The place was packed

when I arrived, and John Pule had just begun his

performance Pacific Holiday. Because of my late arrival

I had a terrible view, and couldn' t see Pule himself. I

could hear him however, as he read his poetry to the

accompaniment of soft drumming. I could also see the

slides he projected onto one gallery wall of various

kitsch Pacific sunsets and smiling Pacific maidens.

Pule' s disembodied voice gently described Pacific

islands and passionate embraces, rising in intensity

and graphic detail to a point were I was made quite

pointedly aware of the hot crush of bodies perspiring

in the room. Just when the pitch was feverish and

excitement was on the verge of embarrassment he

backed off into a softer and more metaphoric

poeticism: perfect timing. The performance ended

with the slide projector turned off and Pule hanging

his baptismal suit, its label reading 'Young Sir Made

in New Zealand', on the wall. A quite beautiful

artifact of Mormonism in the Pacific Islands, a very

poignant reminder of religious and colonial interests

united in the training of the young Pacific body, with

an easy segue into Beuy's felt suit to finish.

The other highlight of the opening was the

contribution of Peter Madden. This charmingly

eccentric artist spent the evening carrying around a

flash chilli bin, from which he distributed ice

sculptures in the shape of curled coat hooks, the old

types with a larger and smaller hook. These were

lovely in themselves, but as a gift they contributed

much towards focusing thoughts to the body. People

were forced to confront a physical strangeness as the

ice melted in your hands. How to deal with drips on

the floor, whether to suck the inviting knob on the

end, and what you did with it once the fun wore off

were questions made intriguing by being played out

in front of everyone else. Madden gleefully stirred the

pot by encouraging mayhem and mess, in the process

providing the means for a joyful transgression of the

disciplined gallery space. I wish I'd seen his previous

cup and saucer ice sculptures with hot coffee poured

in! Beautiful chaos, this guy is brilliant!

Upon a more sober return to the gallery different

things stood out. The two small Louise Bourgeois

drawings were delightful, and added an 'international

hip' feel to the show. Hips were also very much in

play with Christopher Braddock's Midmost, a

muscular piece in fleshy pink. I must say it is

refreshing to see an art work that looks you straight in

the groin. And it seemed to speak to both genders

judging by the vigorous hip thrust I saw one young

woman giving it. On a more material level Esther

Leigh's elegant Lock used human hair to apply a fine

floating line to lacquer, producing sperm- like shapes,

and working with the show's title literally and

metaphorically. In a different way Monique

Redmond's work The Magician's Nephew also ran this

double play. My immediate and strong reaction was

to kneel on the low cushioned sculpture, and in fact

the strength of the urge both struck me and

highlighted the learnt prohibition to doing so. I

thought it most appropriate that a work should insert

itself into the fabric of regulations that control us in

the gallery and make up the viewing body, in such a

subtle but disruptive way.

Peter Madden's sculptural contributions to the

exhibition were intriguing and again whimsically

beautiful. In Site was an installation with a distinct

blue inflection. A bell jar containing blue plaster

kisses their lips pursed, puckered and fleshy, sexy

surreal fruit to devour, sat upon an old wooden unit

(opposite) JOHN PUHIATAU PULE Does This Suit You? 1995

Suit, fine mat & pate

(below) Fleshly Worn , installation at the ASA Gallery showing

works by (left to right) Robert Jahnke, Christopher Braddock, Lucy

Harvey, Esther Leigh & (foreground) Monique Redmond

with a fold-down door to the bottom shelf. This door

was open and revealed on its inside the surface of the

cavity covered in underwater photos: deep-sea diving

and something of a shark situation. The fresh

simplicity of the statement, to open the bottom

drawer and immediately swim in the deep blue

yonder, was irresistible. Madden's work combines a

lightness of touch with a radicality of gesture which is

breathtaking in its assuredness, as it is in its daring.

As with the symposium, the exhibition Fleshly

Worn was exciting, fun and most energetic. They most

certainly lived up to Spinoza' s ethical imperative for

all bodies to attain active affection and the joyful

knowledge they contain. I came.

67

You might also like

- The Nude - A New Perspective, Gill Saunders PDFDocument148 pagesThe Nude - A New Perspective, Gill Saunders PDFRenata Lima100% (7)

- The Global Pharmaceutical IndustryDocument28 pagesThe Global Pharmaceutical IndustryOmolarge100% (1)

- Staging Philosophy Krasner and SaltzDocument343 pagesStaging Philosophy Krasner and Saltzstephao786No ratings yet

- Kinesthetic Empathy in Creative and Cultural PracticesFrom EverandKinesthetic Empathy in Creative and Cultural PracticesDee ReynoldsNo ratings yet

- Sedgwick 3AA3 RevDocument20 pagesSedgwick 3AA3 RevSNasc FabioNo ratings yet

- Bodies On DisplayDocument12 pagesBodies On DisplaybbjanzNo ratings yet

- Editorial Spring Dream Special Issue History Workshop JournalDocument7 pagesEditorial Spring Dream Special Issue History Workshop JournalfalcoboffinNo ratings yet

- Articulo Art PDFDocument2 pagesArticulo Art PDFxasandraNo ratings yet

- Instrumentalisation and Objectification of Human SexualityDocument12 pagesInstrumentalisation and Objectification of Human SexualityiSocialWatch.com100% (1)

- Theatre Is ReligionDocument11 pagesTheatre Is ReligionpancreatinfaceNo ratings yet

- DHDiary5 WebDocument16 pagesDHDiary5 WebJoanne FaulknerNo ratings yet

- TechnoKabbalah-The Performative Language of Magick and The Production of Occult KnowledgeDocument18 pagesTechnoKabbalah-The Performative Language of Magick and The Production of Occult KnowledgeStella Ofis AtzemiNo ratings yet

- Part VIII Art and AnthropologyDocument14 pagesPart VIII Art and AnthropologyEricson Jualo PanesNo ratings yet

- Inga Adaszkiewicz - The - Connection - Between - Bodyart - and - PoliticsDocument7 pagesInga Adaszkiewicz - The - Connection - Between - Bodyart - and - PoliticsadaszkiewiczingaNo ratings yet

- Museum, Urban Detritus and PornographyDocument9 pagesMuseum, Urban Detritus and PornographyÉrica SarmetNo ratings yet

- Evolution of Expressive CultureDocument28 pagesEvolution of Expressive CultureBill BenzonNo ratings yet

- Theatre HistoryDocument27 pagesTheatre Historyj_winter2No ratings yet

- Eros Noir - Transgression in The AestheticDocument245 pagesEros Noir - Transgression in The Aestheticmadi leeNo ratings yet

- Main Essay RedoDocument16 pagesMain Essay Redoapi-285172961No ratings yet

- Theater Arts Module 4Document72 pagesTheater Arts Module 4yoonglespianoNo ratings yet

- LEWIS, George Improvising Tomorrow's Bodies The Politics of TransductionDocument3 pagesLEWIS, George Improvising Tomorrow's Bodies The Politics of TransductionNatália FrancischiniNo ratings yet

- Queering Visual Cultures: Re-Presenting Sexual Politics on Stage and ScreenFrom EverandQueering Visual Cultures: Re-Presenting Sexual Politics on Stage and ScreenNo ratings yet

- Feminism, Art, Deleuze, Darwin. Interview W Eliz. Grosz. 2007Document12 pagesFeminism, Art, Deleuze, Darwin. Interview W Eliz. Grosz. 2007antoaneta_ciobanuNo ratings yet

- Chance and Certainty: John Cage's Politics of Nature: Cultural Critique March 2013Document32 pagesChance and Certainty: John Cage's Politics of Nature: Cultural Critique March 2013H mousaviNo ratings yet

- Drake Hale WMNST 245 Doane L04 Short EssayDocument4 pagesDrake Hale WMNST 245 Doane L04 Short Essayapi-570471336No ratings yet

- Modernism: Literature and Science: DR Katherine EburyDocument19 pagesModernism: Literature and Science: DR Katherine EburyIrfanaNo ratings yet

- The Craftsman Mirroring The Creator - Explorations in Theatrical TheologyDocument30 pagesThe Craftsman Mirroring The Creator - Explorations in Theatrical TheologyMitchell HollandNo ratings yet

- Sue Tait CSIDocument18 pagesSue Tait CSIDelia BrezaNo ratings yet

- History of Emotions InterviewDocument30 pagesHistory of Emotions InterviewKrste IlievNo ratings yet

- Basarab Nicolescu Peter Brook and Traditional ThoughtDocument19 pagesBasarab Nicolescu Peter Brook and Traditional Thoughtmaria_elena910No ratings yet

- Dancing Fear and Desire: Race, Sexuality, and Imperial Politics in Middle Eastern DanceFrom EverandDancing Fear and Desire: Race, Sexuality, and Imperial Politics in Middle Eastern DanceNo ratings yet

- HelenMcGhie AbjectionDocument41 pagesHelenMcGhie Abjection杨徕No ratings yet

- As Discrepâncias Participativas e o Poder Da Música - Charles KeilDocument10 pagesAs Discrepâncias Participativas e o Poder Da Música - Charles Keilgivas.demore5551No ratings yet

- Blurring Boundaries Bookelt FinalDocument18 pagesBlurring Boundaries Bookelt Finalarun_aryaa099578No ratings yet

- And Identity Issues in Southeastern Europe - Bonini BaraldiDocument18 pagesAnd Identity Issues in Southeastern Europe - Bonini Baraldize_n6574No ratings yet

- Post Human AnthropologyDocument32 pagesPost Human AnthropologyMk YurttasNo ratings yet

- Friedrich Nietzsche: Literary Analysis: Philosophical compendiums, #3From EverandFriedrich Nietzsche: Literary Analysis: Philosophical compendiums, #3No ratings yet

- Faith Is A Matter of Experience: Word & World 1/3 (1981)Document10 pagesFaith Is A Matter of Experience: Word & World 1/3 (1981)Selwyn DSouzaNo ratings yet

- The Trouble with Nature: Sex in Science and Popular CultureFrom EverandThe Trouble with Nature: Sex in Science and Popular CultureRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- Rocky Horror Picture Show and The Unseen InfluenceDocument55 pagesRocky Horror Picture Show and The Unseen InfluenceMandula GyőrfiNo ratings yet

- HIGGINS, Dick Intermedia & MetadramasDocument5 pagesHIGGINS, Dick Intermedia & MetadramasLuisa FrazãoNo ratings yet

- Tracy, Critical ReviewDocument4 pagesTracy, Critical ReviewTracy YUNo ratings yet

- Nietzsche PaperDocument12 pagesNietzsche Paperapi-232212025No ratings yet

- Ethical Dilemmas in Theater and FilmDocument3 pagesEthical Dilemmas in Theater and FilmjuanNo ratings yet

- The Body at Stake: Experiments in Chinese Contemporary Art and TheatreFrom EverandThe Body at Stake: Experiments in Chinese Contemporary Art and TheatreJörg HuberNo ratings yet

- Poleteismo by Mideo Cruz: Output #2Document13 pagesPoleteismo by Mideo Cruz: Output #2Almira SantosNo ratings yet

- Theatre SurveyDocument21 pagesTheatre Surveyrgurav806No ratings yet

- Tautological Oxymorons: Deconstructing Scientific Materialism:An Ontotheological ApproachFrom EverandTautological Oxymorons: Deconstructing Scientific Materialism:An Ontotheological ApproachNo ratings yet

- PHD Conclusions Animals in ContemporaryDocument29 pagesPHD Conclusions Animals in ContemporarygaruttimiguelNo ratings yet

- Boredom Time AboriginesDocument11 pagesBoredom Time AboriginesVasilisa FilatovaNo ratings yet

- Karen Dale - Anatomising Embodiment and Organization Theory - Palgrave (2001)Document261 pagesKaren Dale - Anatomising Embodiment and Organization Theory - Palgrave (2001)Rodrigo Martins da SilvaNo ratings yet

- Suggests How To Move A Step Closer Toward Such A Unified Integral UnderstandingDocument5 pagesSuggests How To Move A Step Closer Toward Such A Unified Integral Understandingbanshan466No ratings yet

- Black Performance Theory Edited by Thomas F. DeFrantz and Anita GonzalezDocument26 pagesBlack Performance Theory Edited by Thomas F. DeFrantz and Anita GonzalezDuke University Press100% (4)

- DEFRANTZ-GONZALEZ - Black Performance Thoery (Intro)Document26 pagesDEFRANTZ-GONZALEZ - Black Performance Thoery (Intro)IvaaliveNo ratings yet

- Thomas F. DeFrantz, Anita Gonzalez - Black Performance Theory-Duke University Press (2014)Document292 pagesThomas F. DeFrantz, Anita Gonzalez - Black Performance Theory-Duke University Press (2014)Bruno De Orleans Bragança ReisNo ratings yet

- Body Culture: Henning EichbergDocument20 pagesBody Culture: Henning EichbergShubhadip AichNo ratings yet

- Queer Beauty: Sexuality and Aesthetics from Winckelmann to Freud and BeyondFrom EverandQueer Beauty: Sexuality and Aesthetics from Winckelmann to Freud and BeyondNo ratings yet

- Voto (1998)Document6 pagesVoto (1998)Christopher BraddockNo ratings yet

- Contagious Participation Magic's Power To Affect (2011)Document12 pagesContagious Participation Magic's Power To Affect (2011)Christopher Braddock100% (1)

- The Artist Will Be Present (2008)Document236 pagesThe Artist Will Be Present (2008)Christopher BraddockNo ratings yet

- Random Entrant - FRAKCIJA 50 (2009)Document8 pagesRandom Entrant - FRAKCIJA 50 (2009)Christopher BraddockNo ratings yet

- Safe - Eyline 42 (Winter 2000)Document3 pagesSafe - Eyline 42 (Winter 2000)Christopher BraddockNo ratings yet

- Alicia Frankovich and The Force of Failure - Column 5 (2010)Document8 pagesAlicia Frankovich and The Force of Failure - Column 5 (2010)Christopher BraddockNo ratings yet

- Contingency Plan DRRMDocument24 pagesContingency Plan DRRMLuis IlayganNo ratings yet

- Feature WritingDocument3 pagesFeature WritingaddreenaNo ratings yet

- Dangerous Complications of Acute Cholecystitis: CT Findings: Poster No.: Congress: Type: AuthorsDocument18 pagesDangerous Complications of Acute Cholecystitis: CT Findings: Poster No.: Congress: Type: AuthorsAdrian BăloiNo ratings yet

- Masterclass ProgrammeDocument8 pagesMasterclass ProgrammewmogtNo ratings yet

- Delgado Guay (2015)Document7 pagesDelgado Guay (2015)Aprilla Ayu WulandariNo ratings yet

- BUERGER's Inavasc IV Bandung 8 Nov 2013Document37 pagesBUERGER's Inavasc IV Bandung 8 Nov 2013Deviruchi GamingNo ratings yet

- AIS2 - DR - Daniel - Nuzum - Hormone Class - Acupuncture - ChiropracticDocument10 pagesAIS2 - DR - Daniel - Nuzum - Hormone Class - Acupuncture - ChiropracticPanther PrimeNo ratings yet

- Radial Nerve: Rajadurai R Crri, Orthopedics Ii Unit RGGGHDocument31 pagesRadial Nerve: Rajadurai R Crri, Orthopedics Ii Unit RGGGHrajaeasNo ratings yet

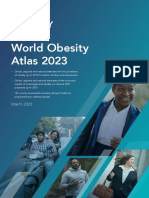

- World Obesity Atlas 2023 ReportDocument232 pagesWorld Obesity Atlas 2023 ReportVozMediaNo ratings yet

- Journal of The American Academy of Dermatology Volume 77 Issue 4 2017 (Doi 10.1016 - J.jaad.2017.01.036) Chaowattanapanit, Suteeraporn Silpa-Archa, Narumol Kohli, Inde - Postinflammatory HyperpigmeDocument15 pagesJournal of The American Academy of Dermatology Volume 77 Issue 4 2017 (Doi 10.1016 - J.jaad.2017.01.036) Chaowattanapanit, Suteeraporn Silpa-Archa, Narumol Kohli, Inde - Postinflammatory HyperpigmedikativiNo ratings yet

- Spectrum of Tuberculosis The End of The Binary Era: Revisiting TheDocument9 pagesSpectrum of Tuberculosis The End of The Binary Era: Revisiting TheGheorghe-Emilian OlteanuNo ratings yet

- Warm Muscles Before Exercisestretch Out Stretchtire Out ExhaustmusclesDocument1 pageWarm Muscles Before Exercisestretch Out Stretchtire Out Exhaustmuscleskarla duarteNo ratings yet

- Syphilis "The Great Pretender": By: Bruce MartinDocument28 pagesSyphilis "The Great Pretender": By: Bruce MartinChatie PipitNo ratings yet

- Opening Speech OutlineDocument2 pagesOpening Speech OutlineAnaNo ratings yet

- National NORCET-3 - FinalDocument90 pagesNational NORCET-3 - FinalSHIVANIINo ratings yet

- Antifilm Activity of PlantsDocument7 pagesAntifilm Activity of PlantsArshia NazirNo ratings yet

- Jurnal MenarcheDocument9 pagesJurnal MenarcherftdlsNo ratings yet

- Joyce Travelbe1Document3 pagesJoyce Travelbe1Dudil GoatNo ratings yet

- Dyslipidemia 2021Document86 pagesDyslipidemia 2021Rania ThiniNo ratings yet

- Oral Hygiene For Conscious Patient and UnconciousDocument2 pagesOral Hygiene For Conscious Patient and UnconciousDredd Alejo Sumbad100% (1)

- FULL Download Ebook PDF Human Anatomy Lab Manual 3rd Edition PDF EbookDocument41 pagesFULL Download Ebook PDF Human Anatomy Lab Manual 3rd Edition PDF Ebookdaniel.welton458100% (40)

- Bio ElectromagneticsDocument21 pagesBio Electromagneticsgeet18061984No ratings yet

- Dewi Hastuti - ENGLISH 3 WonogiriDocument51 pagesDewi Hastuti - ENGLISH 3 WonogiriDewi HastutiNo ratings yet

- Jurnal GadarDocument10 pagesJurnal GadarRiandini PandansariNo ratings yet

- Medical TerminologyDocument14 pagesMedical TerminologyAdi SomersetNo ratings yet

- Nick Corbin Vasopressin PPT 5 3 2022 1Document57 pagesNick Corbin Vasopressin PPT 5 3 2022 1api-611517539No ratings yet

- College of Nursing: Pharmacological ManagementDocument2 pagesCollege of Nursing: Pharmacological ManagementJOHN PEARL FERNANDEZNo ratings yet

- Red Cell Distribution Width (RDW) : A Prognostic Indicator of Severe COVID-19Document10 pagesRed Cell Distribution Width (RDW) : A Prognostic Indicator of Severe COVID-19Salsabillah SnNo ratings yet

- Werner Mork: Excerpts From The Memoirs ofDocument21 pagesWerner Mork: Excerpts From The Memoirs ofnorman0303No ratings yet