Professional Documents

Culture Documents

11 Epidemiologicalbbbbbb PDF

11 Epidemiologicalbbbbbb PDF

Uploaded by

Nur KholifahOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

11 Epidemiologicalbbbbbb PDF

11 Epidemiologicalbbbbbb PDF

Uploaded by

Nur KholifahCopyright:

Available Formats

Chang et al.

BMC Infectious Diseases 2011, 11:352

http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2334/11/352

RESEARCH ARTICLE

Open Access

Epidemiological characteristics of varicella from

2000 to 2008 and the impact of nationwide

immunization in Taiwan

Luan-Yin Chang1*, Li-Min Huang1, I-Shou Chang2 and Fang-Yu Tsai2

Abstract

Background: Varicella has an important impact on public health. Starting in 2004 in Taiwan, nationwide free

varicella vaccinations were given to 1-year-old children.

Methods: Our study investigated the epidemiological characteristics of varicella from 2000 to 2008, and assessed

the change of varicella epidemiology after the mass varicella immunization. ICD-9-CM codes related to varicella or

chickenpox (052, 052.1, 052.2, 052.7, 052.8, 052.9) were analyzed for all young people under 20 years of age

through the National Health Insurance database of Taiwan from 2000 to 2008.

Results: Case numbers of varicella or chickenpox significantly declined after the nationwide immunization in 2004.

Winter, particularly January, was the epidemic season of varicella. We found a significant post-vaccination decrease

in incidence among preschool children, especially 3 to 6 year-old children the peak incidence was 66 per

thousand for 4 and 5 year-old children before the nationwide immunization (2000 to 2003), and the peak

incidence was 23 per thousand for 6 year-old children in 2008 (p < 0.001). Varicella-related hospitalization also

significantly decreased in children younger than 6 years after the nationwide immunization.

Conclusion: The varicella annual incidence and varicella-related hospitalization markedly declined in preschool

children after nationwide varicella immunization in 2004.

Keywords: varicella, chickenpox, epidemiology, incidence, vaccine, prevention

Background

Varicella is the primary disease caused by the varicellazoster virus. It is a common and highly contagious disease and has a significant health impact on children.

Although the clinical course of varicella is usually mild

and self-limiting, varicella does cause complications and

mortality resulting in financial expense [1-3]. Chickenpox

or varicella now has been considered one of the most

common vaccine-preventable diseases in many countries

[4-7].

In Taiwan, some areas including Taipei City, Taichung

City and Taichung County gave the public free varicella

vaccinations for 1-2 year-old children before 2004. Taipei

City started the free varicella vaccination from 1998 and

* Correspondence: lychang@ntu.edu.tw

1

Department of Pediatrics, National Taiwan University Hospital, College of

Medicine, National Taiwan University, Taipei, Taiwan

Full list of author information is available at the end of the article

Taichung City and Taichung County from 1999. Other

areas did not provide free varicella vaccination, but people could receive varicella vaccination at their own

expense before 2004. Since 2004, free mass varicella

immunization has been given to all one year-old children

throughout Taiwan.

Since the implementation of National Health Insurance

(NHI) in 1995, there has been a healthcare database in

Taiwan. Taiwan has a population of 22.9 million people

and the land area of 36188 Km2. Its population density is

633/Km2. Taiwans NHI covered most of the health care

costs for 98% of its population in 2006 [8]; the remaining

2% of it population are living in the foreign countries or in

families with monthly household incomes less than 1000

US dollars. Taiwans NHI database includes health care

data collected from over 95% of the hospitals in Taiwan

for more than 96% of the population receiving health care.

We evaluated the disease burden and epidemiological

2011 Chang et al; licensee BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons

Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in

any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Chang et al. BMC Infectious Diseases 2011, 11:352

http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2334/11/352

characteristics of varicella by using the NHI database to

find out the age-specific incidences, seasonal distribution

and varicella-related hospitalization from 2000 to 2008

the period covering pre- and post-public free vaccination

so we could compare the epidemiological characteristics

of varicella before and after the mass immunization.

Methods

Vaccination

The administration of a live attenuated varicella vaccine

was licensed in Taiwan in 1997. Both Merck and GlaxoSmithKline, pharmaceutical companies, provided the varicella vaccines in Taiwan. In 2004 the varicella vaccine

was incorporated into Taiwans national immunization

program, and all 1-year-old children could receive the

varicella vaccine for free. The varicella coverage rate for

1-year-old children was 94% for the 2003 birth cohort,

95% for the 2004 cohort, and 97% for the 2005, 2006, and

2007 birth cohorts according to Taiwans National

Immunization Information System which was developed

in the early 1990s [9]. When a child received a vaccine,

his or her vaccination would not only be recorded in a

childs vaccination handbook but would also be reported

to the National Immunization Information System.

Data collection

Taiwans National Health Insurance (NHI) covered most

of the health care costs for 98% of its population. Taiwans NHI database includes health care data collected

from over 95% of the hospitals in Taiwan for more than

98% of the population receiving health care. From this

database, hospitalization and outpatient healthcare

records were collected from 2000 to 2008, and International Classifications of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical

Modification (ICD-9-CM) codes related to varicella or

chickenpox were analyzed for all the population. The

age-specific annual incidence and hospitalization rate

were calculated. For calculating the annual populationbased incidence, the annual incidence was calculated by

dividing the number of varicella-related diseases by the

population, which was obtained from Department of Statistics, Ministry of the Interior, Taiwan from 2000 to

2008 [10].

Definitions

ICD-9-CM codes for chickenpox or varicella include the

following: 052 chickenpox; 052.0 post-varicella encephalitis,

post-chickenpox encephalitis; 052.1 varicella (hemorrhagic)

pneumonitis; 052.7 with other specified complications;

052.8 with unspecified complication; 052.9 varicella without mention of complication.

For complications, we define varicella or chickenpox

patients to have complications in cases where the

patients had both ICD-9-CM codes for varicella or

Page 2 of 7

chickenpox (052 and the other related codes) and also

ICD-9-CM codes for varicella-related complications

which include the following: central nervous system

including 320 meningitis, 322 cerebellitis, 323 encephalitis, 348 encephalopathy, 351 facial palsy, 331.81 Reyes

syndrome, 780.3 febrile convulsion/seizure; skin and soft

tissue including 680-686 cellulites and abscess, 035 erysipela, 728 pyomyositis and necrotizing fasciitis, 373 &

376.01 blepharitis, 034 & 041 scarlet fever and streptococcal or staphylococcal infection; skeletal system including 711 arthritis, 730-733 osteomyelitis; lower respiratory

tract infection including 480-487 pneumonia, 510-519

pneumonitis, 466 & 490 bronchitis; hematological system- 287 thrombocytopenia, 283 & 285 anemia, 288 neutropenia; 038 & 790 & 995.91-995.92 for sepsis and

bacteremia; 040-041 for other bacterial infection; 422

cardiomyopathy, 425 myocarditis; 070.5 & 070.9 & 573

for hepatitis.

Statistics

In univariate analysis, categorical variables were compared with chi-square or Fishers exact test; continuous

variables were analyzed with Students t test. The difference of annual incidence among various age groups, the

difference of annual incidences in different years, and

the difference in seasonal distribution were measured

with appropriate c2 test. A p value of < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant. All statistical analyses

were performed with SAS software, version 9.0.

Results

Number of cases before and after the mass immunization

The monthly distribution of case numbers from 2000 to

2008 is demonstrated in Figure 1. Case numbers markedly declined after the mass immunization in 2004, the

highest monthly number was 23460 in January 2000,

and the lowest was 2016 in September 2008. The peak

of varicella usually occurred during winter, especially in

January.

Age distribution

Overall age-specific case numbers and the cumulative

percentage of varicella in children from 2000 to 2008 are

shown in Figure 2, those of 2000 in Figure 3, and those

of 2008 in Figure 4. Children younger than 10 years old

represented 89% of all the cases and the peak age was 3

to 6 years from 2000 to 2008 (Figure 2). However, the

age distribution changed significantly after the mass

immunization (p < 0.001): 73% of varicella cases were

children less than 6 years of age in 2000 (before the mass

immunization, Figure 3) but only 24% of the cases were

children younger than 6 years of age in 2008 (4 years

after the mass immunization, Figure 4). In comparison

with age-specific case numbers of 2000 (Figure 3), those

Chang et al. BMC Infectious Diseases 2011, 11:352

http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2334/11/352

Page 3 of 7

Case Number

Mass immunization

2000

2001

2002

2003

2004

2005

2006

2007

7

10

7

10

10

7

10

7

10

10

7

10

7

10

10

2008

Figure 1 Monthly distribution of varicella case number from 2000 to 2008.

Age-specific annual incidence

Figure 5 demonstrates the age-specific annual incidence of

varicella before and after the nationwide immunization. In

160000

100%

140000

90%

80%

Case number

120000

70%

100000

Case number

80000

Cumulative percentage

60000

60%

50%

40%

30%

40000

20%

20000

10%

0%

0

10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19

Age

Figure 2 Age-specific case number and cumulative percentage of varicella in children from 2000 to 2008.

Cumulative percentage

2000 to 2003 (before the nationwide immunization), the

peak incidence was in 4 and 5-year-old children with

annual incidence of 66 per thousand while in 2008, the

peak incidence occurred in 6-year-old children with

annual incidence of 23 per thousand (p < 0.01). After the

nationwide immunization in 2004, the annual incidence

significantly decreased among children younger than 7

of 2008 were significantly lower (Figure 4) (p < 0.01). In

2008, school children had more varicella cases than the

kindergarteners.

Chang et al. BMC Infectious Diseases 2011, 11:352

http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2334/11/352

Page 4 of 7

100%

30000

90%

20000

15000

80%

Cumulative percenatge

Case number

25000

70%

Case number

60%

Cumulative percentage

50%

40%

10000

30%

20%

5000

10%

0

0%

0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19

Age

Figure 3 Age-specific case number and cumulative percentage of varicella in children in 2000, before the nationwide immunization.

30000

100%

Case number

80%

70%

20000

60%

15000

Case Number

50%

Cumulative Percentage

40%

10000

30%

20%

5000

Cumulative percentage

90%

25000

10%

0%

0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19

Figure 4 Age-specific case number and cumulative percentage of varicella in children in 2008, 4 years after the nationwide

immunization.

Annual incidence per thousand

Chang et al. BMC Infectious Diseases 2011, 11:352

http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2334/11/352

Page 5 of 7

70

60

50

40

30

20

10

0

0

10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19

Age

Figure 5 Age-specific annual incidence of varicella before (2000-2003) and after the nationwide immunization (2004, 2005, 2006, 2007

and 2008).

years of age. In 2008, the annual incidence (6.8 per thousand) of infants who could not receive the varicella vaccine

was even higher than that (3.2 to 5.9 per thousand) of 1 to

4-year-old children. Children beyond 7 years had similar

annual incidence before and after the mass immunization.

Age-specific varicella-related hospitalization incidence

The proportion of the number of varicella-related hospitalization to the number of overall varicella cases was

the highest in infants and declined with age in children.

Figure 6 shows that the annual incidence of varicellarelated hospitalization was the highest in infants. In

comparison with the annual incidence of 2000 to 2003

(before the nationwide immunization), the annual incidence of hospitalization significantly declined in children

younger than 6 years of age from 2004 to 2008 (p <

0.01). From 2000 to 2008, the annual incidence of preschool children decreased obviously with the year.

Complications

Among the 21829 hospitalized cases, 561 (2.57%) had

central nervous system complications, 2721 (12.47%)

had skin or soft tissue infections, 4740 (21.71%) had

lower respiratory tract infections, 493 (2.26%) had hematological complications, 281 (1.29%) had septicemia or

bacteremia, and 721 (3.30%) had hepatitis.

Twelve children died and Table 1 lists the demography and complications of the 12 fatal varicella cases.

Five of them had underlying diseases including 2 with

acute lymphoblastic leukemia, 1 with severe combined

immunodeficiency, 1 with enzymopathy, and 1 with pulmonary vascular anomaly. Most of them had complications of septicemia, skin or soft tissue infections, or

encephalitis, and 1 had Reye syndrome.

Discussion

Nationwide varicella immunization has resulted in a

marked reduction of varicella incidence and varicellarelated hospitalization in children younger than 6 years

of age in Taiwan. The impact of mass varicella immunization has so far made it possible for most preschool children to be free of varicella and varicella-related

hospitalization in Taiwan. However, children beyond 7

years of age had similar annual incidence before and after

the mass immunization.

As Figure 3 shows the age distribution before the mass

immunization in 2000, the peak age of varicella was 3 to 6

years, which was also the age group of kindergarteners.

Kindergarteners might have more exposure to varicella

and also their hand hygiene and sanitation levels are generally not as high as adults or older school childrens, who

may in turn lead to more varicella cases in kindergarteners

without mass immunization (Figure 3). However, after the

mass immunization, we observed more varicella cases in

the school children than those in 3 to 4-year-old kindergarteners (Figure 4), who were supposed to have received

the free varicella vaccine at 1 year of age. Therefore, mass

immunization has changed the age distribution of varicella

cases significantly and the peak age has subsequently

moved to older children without previous immunization.

Chang et al. BMC Infectious Diseases 2011, 11:352

http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2334/11/352

Page 6 of 7

Annual incidence per thousand

0.9

0.8

0.7

0.6

0.5

0.4

0.3

0.2

0.1

0

0

9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19

Age

Figure 6 Age-specific annual incidence of varicella-related hospitalization before (2000-2003) and after the nationwide immunization

(2004, 2005, 2006, 2007 and 2008).

Similar results were also reported by Lian et al who found

that the greatest decrease in varicella incidence occurred

in children aged below 6 and the incidence of varicella

shifted to older age groups after implementation of the

one-dose varicella vaccination policy [11]. Lian et al also

found that the incidence in early launch areas was significantly lower than that in the other areas in Taiwan [11].

Our study additionally reported the seasonality, varicellarelated hospitalization and complications from 2000 to

2008 in Taiwan. Moreover, our data in this study is

nationwide rather than the selected sample size like that of

Lian et als study.

We found that the annual incidence of children beyond

7 years of age was similar before and after mass immunization. Its because most of the school children were not

allowed to receive the free varicella vaccine. Thus, the

varicella incidence of the school children did not change

significantly after the mass immunization in this study.

We suppose that the annual incidence of school children

may decrease several years later if the immunized children grow up to be 6 to 12 years old. However, we have

to follow up on the impact of mass immunization on

school children to prove the above assumption several

years later.

Table 1 Demography and complications of 12 fatal varicella cases

Year

Age

Sex

Underlying disease

Complications

2000

Nil

Encephalitis, septic shock

2000

Unspecified Enzymopathy

Pseudomonas septicemia

2000

Acute lymphoblastic leukemia

Septicemia

2001

Nil

Encephalitis, septicemia

2001

2002

6

3

F

F

Nil

Nil

Sudden death

Respiratory failure

2002

Acute lymphoblastic leukemia

Not mentioned

2003

Nil

Skin/soft tissue infections, streptococcal septicemia

2004

16

Nil

Skin/soft tissue infections, pneumonia, septicemia

2005

Nil

Reyes syndrome

2006

Severe combined immunodeficiency

Acute and subacute hepatic necrosis, gastrointestinal hemorrhage

2007

Pulmonary vascular anomaly

Hemoptysis, acute respiratory failure

Chang et al. BMC Infectious Diseases 2011, 11:352

http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2334/11/352

The infants had the highest annual incidence of varicella-related hospitalization both before and after the

mass immunization (Figure 6). Infants cannot receive

the varicella vaccine and they have a higher chance of

severe varicella and more complications [12], so their

varicella-related hospitalization was significantly higher

than the other children.

There were 12 cases of fatality, of which 5 of them

had underlying diseases. Children with underlying diseases such as acute leukemia are more susceptible to

getting severe varicella with complications and have a

significantly higher mortality rate [12]. Therefore, the

varicella vaccine may be administered to children with

acute lymphoblastic leukemia who are in remission, or,

high-titer anti-varicella-zoster virus immune globulin as

post-exposure prophylaxis is recommended for immunocompromised children and newborns that are

exposed maternally to varicella [12].

Currently, the varicella vaccine program consists of a

single-dose vaccination in Taiwan, as it is in Canada,

Korea and Australia [13]. However, both varicella outbreaks and breakthrough infections have occurred after

the single-dose varicella vaccine program was initiated

[14]. These might be related to a loss of immunity or to

primary vaccine failure. Although the reports are limited,

varicella vaccine effectiveness may be higher when two

doses are administered than when a single-dose is administered. In 2006, the United States changed its immunization policy by stipulating that 2 doses be administered,

once at 1 year of age and another administered between

the ages of 3 and 4 years old [15]. In Taiwan, boosters in

4-6 year-old children to reduce the breakthrough infection

or amend the primary vaccine failure may be considered if

further epidemiology reveals frequent outbreaks or breakthrough infections in kindergarteners.

The major limitation of this study is that we could not

verify the diagnoses because we could just analyze the

NHI database rather than detailed medical charts. However, at the very least the nationwide database can let us

outline the comprehensive picture of varicella epidemiology in Taiwan and sketch the impact of nationwide

immunization.

Conclusions

In conclusion, nationwide varicella immunization significantly decreased the varicella annual incidence and varicella-related hospitalization in preschool children in

Taiwan. The impact of the varicella vaccine on schoolchildren may be followed up on several years later.

Acknowledgements and Funding

This study is based in part on data from the National Health Insurance

Research Database provided by the Bureau of National Health Insurance,

Department of Health and managed by National Health Research Institutes.

Page 7 of 7

The interpretation and conclusions contained herein do not represent those

of the Bureau of National Health Insurance, Department of Health or

National Health Research Institutes. This research was supported by the

grants, NSC 100-2321-B-002 -012 from National Science Council and DOH

98-CD-1010 from Centers for Disease Control, Taiwan. The funding institutes

did not have any role in study design, data collection/analysis, the writing of

the manuscript and the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Author details

Department of Pediatrics, National Taiwan University Hospital, College of

Medicine, National Taiwan University, Taipei, Taiwan. 2National Institute of

Cancer Research and Division of Biostatistics and Bioinformatics, National

Health Research Institute, Miaoli, Taiwan.

1

Authors contributions

LYC, LMH and ISC designed the study. LYC and FYT analyzed the data. LYC

wrote the paper. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Received: 9 June 2011 Accepted: 16 December 2011

Published: 16 December 2011

References

1. Carapetis JR, Russell DM, Curtis N: The burden and cost of hospitalised

varicella and zoster in Australian children. Vaccine 2004, 23:755-61.

2. Poulsen A, Cabral F, Nielsen J, Roth A, Lisse I, Aaby P: Growth, morbidity

and mortality after chickenpox infection in young children in GuineaBissau. J Infect 2005, 51:307-13.

3. Rivest P, Bedard L, Valiquette L, Mills E, Lebel MH, Lavoie G, et al: Severe

complications associated with varicella: Province of Quebec, April 1994

to March 1996. Can J Infect Dis 2001, 12:21-6.

4. Patrick D: Prevention strategies: experience of varicella vaccination

programmes. Herpes 2007, 14(Suppl 2):48-51.

5. Asano Y: Varicella vaccine: the Japanese experience. J Infect Dis 1996,

174(Suppl 3):S310-3.

6. Macartney KK, Beutels P, McIntyre P, Burgess MA: Varicella vaccination in

Australia. J Paediatr Child Health 2005, 41:544-52.

7. Getsios D, Caro JJ, Caro G, De Wals P, Law BJ, Robert Y, et al: Instituting a

routine varicella vaccination program in Canada: an economic

evaluation. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2002, 21:542-7.

8. Burea of National Health Insurance, Department of Health, Executive Yuan,

Taiwan ROC: Statistical annual reports., (Accessed at http://www.doh.gov.

tw/statistic/%A5%FE%A5%C1%B0%B7%ABO/95.htm).

9. Taiwan Center for Disease Control, Department of Health, Executive Yuan,

Taiwan: National Immunization Information System (NIIS).[http://www.cdc.

gov.tw/public/Data/7121816155271.doc].

10. Department of Statistics MotI, Taiwan: Population by Single Year of Age.

Department of Statistics, Taiwan;[http://www.moi.gov.tw/stat/index.asp].

11. Lian IB, Chien YZ, Hsu PS, Chao DY: The changing epidemiology of

varicella incidence after implementation of the one-dose varicella

vaccination policy. Vaccine 2011, 29(7):1448-54.

12. Myers MG, Seward JF, LaRussa FS: Varicella-zoster virus. Nelson Textbook of

Pediatrics , 18 2007.

13. Heininger U, Seward JF: Varicella. Lancet 2006, 368:1365-76.

14. Galil K, Lee B, Strine T, et al: Outbreak of varicella at a day-care center

despite vaccination. N Engl J Med 2002, 347(24):1909-15.

15. Marin M, Meissner HC, Seward JF: Varicella prevention in the United

States: a review of successes and challenges. Pediatrics 2008, 122:e744-51.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:

http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2334/11/352/prepub

doi:10.1186/1471-2334-11-352

Cite this article as: Chang et al.: Epidemiological characteristics of

varicella from 2000 to 2008 and the impact of nationwide

immunization in Taiwan. BMC Infectious Diseases 2011 11:352.

You might also like

- 10 DOH ProgramsDocument28 pages10 DOH ProgramsDhonnalyn Amene Caballero100% (6)

- Analysis of The Rate of Infant Mortality From I Month To I YearDocument62 pagesAnalysis of The Rate of Infant Mortality From I Month To I YearChukwuma NdubuisiNo ratings yet

- Research Proposal On Prevalence of PneumoniaDocument26 pagesResearch Proposal On Prevalence of Pneumoniasolomon demissew62% (13)

- Critique PaperDocument2 pagesCritique PaperJeanne Kamille Evangelista Pinili100% (4)

- The Strategy Behind Taiwan's COVID-19 Immunization Program National Security and Global SolidarityDocument18 pagesThe Strategy Behind Taiwan's COVID-19 Immunization Program National Security and Global Solidarity林冠年No ratings yet

- Samuel CHAPTER 1 CorrectionDocument10 pagesSamuel CHAPTER 1 CorrectionNaomi AkinwumiNo ratings yet

- Civ 028Document9 pagesCiv 028Deah RisbaNo ratings yet

- The Effect of The COVID-19 Vaccine On Daily Cases and Deaths Based On Global Vaccine DataDocument12 pagesThe Effect of The COVID-19 Vaccine On Daily Cases and Deaths Based On Global Vaccine DataCorneliu PaschanuNo ratings yet

- Surveillance of Healthcare-Associated Infections in A Neonatal Intensive Care Unit in Italy During 2006 - 2010Document8 pagesSurveillance of Healthcare-Associated Infections in A Neonatal Intensive Care Unit in Italy During 2006 - 2010Refy Dwi Maltha PratiwiNo ratings yet

- Expanded Program On Immunization: Source: Weekly Epidemiological Record, WHO: No.46,2011,86.509-520)Document6 pagesExpanded Program On Immunization: Source: Weekly Epidemiological Record, WHO: No.46,2011,86.509-520)Abeer AguamNo ratings yet

- Expanded Program On Immunization: Source: Weekly Epidemiological Record, WHO: No.46,2011,86.509-520)Document6 pagesExpanded Program On Immunization: Source: Weekly Epidemiological Record, WHO: No.46,2011,86.509-520)Abeer AguamNo ratings yet

- 933-Article Text-3081-1-10-20221107Document5 pages933-Article Text-3081-1-10-20221107Andri Tri KuncoroNo ratings yet

- Guidelines For The Management of Suspected and Confirmed Bacterial Meningitis inDocument18 pagesGuidelines For The Management of Suspected and Confirmed Bacterial Meningitis inswr88kv5p2No ratings yet

- An Analysis of Taiwan's Vaccination Services and Applications For Vaccine Injury CompensationsDocument15 pagesAn Analysis of Taiwan's Vaccination Services and Applications For Vaccine Injury CompensationsAnonymous FNZ3uR2AHsNo ratings yet

- Persevere in The Dynamic COVID-Zero Strategy in China To Gain A Precious Time Window For The FutureDocument2 pagesPersevere in The Dynamic COVID-Zero Strategy in China To Gain A Precious Time Window For The FutureBillNo ratings yet

- Expanded Program On ImmunizationDocument6 pagesExpanded Program On ImmunizationAiza Oronce100% (1)

- Journal Article PDFDocument10 pagesJournal Article PDFAlyssa marieNo ratings yet

- Surveillance and Outbreak Investigation StudentDocument11 pagesSurveillance and Outbreak Investigation Studentnura meccaNo ratings yet

- Influenza Vaccination Among Infection Control Teams A EUCIC Surve - 2020 - VaccDocument5 pagesInfluenza Vaccination Among Infection Control Teams A EUCIC Surve - 2020 - VaccSavaNo ratings yet

- Department of Health - Expanded Program On Immunization - 2012-05-16Document7 pagesDepartment of Health - Expanded Program On Immunization - 2012-05-16MasterclassNo ratings yet

- The Rise of Imported Dengue Infections in Victoria, Australia, 2010-2016Document11 pagesThe Rise of Imported Dengue Infections in Victoria, Australia, 2010-2016Satriya WibawaNo ratings yet

- OpenSAFELY. Effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccination in children and adolescentsDocument29 pagesOpenSAFELY. Effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccination in children and adolescentsPABLO HONDUVILLANo ratings yet

- The Impact of Rotavirus Mass Vaccination On Hospitalization Rates, Nosocomial Rotavirus Gastroenteritis and Secondary Blood Stream InfectionsDocument10 pagesThe Impact of Rotavirus Mass Vaccination On Hospitalization Rates, Nosocomial Rotavirus Gastroenteritis and Secondary Blood Stream InfectionsKollar RolandNo ratings yet

- HHS Public Access: A Comparison of Post-Elimination Measles Epidemiology in The United States, 2009 2014 Versus 2001 2008Document20 pagesHHS Public Access: A Comparison of Post-Elimination Measles Epidemiology in The United States, 2009 2014 Versus 2001 2008Titania YuliskaNo ratings yet

- Meningitis in Children Under Five Year of Age.: DR Farrukh Iqbal Roll Number 06Document23 pagesMeningitis in Children Under Five Year of Age.: DR Farrukh Iqbal Roll Number 06dr_hammadNo ratings yet

- Vaccines 11 00306Document10 pagesVaccines 11 00306Mr SoehartoNo ratings yet

- SceirdDocument9 pagesSceirdGiaWay HsuNo ratings yet

- Zamora-Ledezma Et Al. - 2020 - Biomedical Science To Tackle The COVID-19 PandemicDocument48 pagesZamora-Ledezma Et Al. - 2020 - Biomedical Science To Tackle The COVID-19 PandemicEli Díaz de ZamoraNo ratings yet

- M1.U2 Measuring and Comparing Disease Frequency - StudentDocument6 pagesM1.U2 Measuring and Comparing Disease Frequency - StudentHusni MubarakNo ratings yet

- National HIV Action Plan 2017-2025: Tallinn 2017Document31 pagesNational HIV Action Plan 2017-2025: Tallinn 2017MeriAndaniSiahaanNo ratings yet

- Changes in Childhood Vaccination During The Coronavirus Disease 2 - 2021 - VacciDocument7 pagesChanges in Childhood Vaccination During The Coronavirus Disease 2 - 2021 - VacciProfessor BiologiaNo ratings yet

- Ca Covid 19 Delta VariantDocument42 pagesCa Covid 19 Delta VariantKristine Joy Vivero BillonesNo ratings yet

- 32Document10 pages32María Jesús Maass OleaNo ratings yet

- Impact of COVID19 On Routine Immunization: A Cross-Sectional Study in SenegalDocument6 pagesImpact of COVID19 On Routine Immunization: A Cross-Sectional Study in SenegalAjeng SuparwiNo ratings yet

- Article Covid-19 Children ReviewDocument12 pagesArticle Covid-19 Children ReviewAlexRázuri100% (1)

- Measles Study PDFDocument8 pagesMeasles Study PDFWebster The-TechGuy LunguNo ratings yet

- Effectiveness of Vaccination Against Varicella in Children Under 5 Years in Puglia Italy 2006 2012Document7 pagesEffectiveness of Vaccination Against Varicella in Children Under 5 Years in Puglia Italy 2006 2012NurulAlviFauzianaNo ratings yet

- Varicella in Pediatric Oncology Patients in The Post-Vaccine Era-Analysis of Routine Hospital Data From Bavaria (Germany), 2005-2011Document13 pagesVaricella in Pediatric Oncology Patients in The Post-Vaccine Era-Analysis of Routine Hospital Data From Bavaria (Germany), 2005-2011Hizam ZulfhiNo ratings yet

- Acute Flaccid Paralysis Field Manual: For Communicable Diseases Surveillance StaffDocument29 pagesAcute Flaccid Paralysis Field Manual: For Communicable Diseases Surveillance StaffAuliyaa RahmahNo ratings yet

- Dengue Net Flyer 2006Document1 pageDengue Net Flyer 2006Neha SameerNo ratings yet

- Telehealth For Global Emergencies: Implications For Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19)Document6 pagesTelehealth For Global Emergencies: Implications For Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19)Niki Pratiwi WijayaNo ratings yet

- Directly Observed Treatment Short-Course (DOTS) For Tuberculosis Control Program in Gambella Regional State, Ethiopia: Ten Years ExperienceDocument8 pagesDirectly Observed Treatment Short-Course (DOTS) For Tuberculosis Control Program in Gambella Regional State, Ethiopia: Ten Years ExperienceTammy Utami DewiNo ratings yet

- Out 123Document8 pagesOut 123Ilvita MayasariNo ratings yet

- Acceptance of A COVID-19 VacciDocument12 pagesAcceptance of A COVID-19 VacciahmadNo ratings yet

- MeningitisDocument62 pagesMeningitisDaniela Ramírez DavilaNo ratings yet

- The First Ever Confirmed Case of COVID-19 in Australia Was On January 25, 2020. The Patient Came From Wuhan and Flew To Melbourne On January 19Document6 pagesThe First Ever Confirmed Case of COVID-19 in Australia Was On January 25, 2020. The Patient Came From Wuhan and Flew To Melbourne On January 19Rastie CruzNo ratings yet

- Invasive Pneumococcal Disease - Canada - Ca 2000-2011Document12 pagesInvasive Pneumococcal Disease - Canada - Ca 2000-2011Regina EnggelineNo ratings yet

- Dept. Expanded Program On ImmunizationDocument6 pagesDept. Expanded Program On ImmunizationknotstmNo ratings yet

- 10 1016@j Jiac 2017 02 014Document12 pages10 1016@j Jiac 2017 02 014Achmad YunusNo ratings yet

- Asia Covid EstrategiasDocument10 pagesAsia Covid EstrategiasJonell SanchezNo ratings yet

- Safety Monitoring of COVID-19 Vaccines in Hong KongDocument19 pagesSafety Monitoring of COVID-19 Vaccines in Hong KongCarrie ChanNo ratings yet

- Covid 19Document16 pagesCovid 19Mazia MansoorNo ratings yet

- Outside The Window by David Naga (Essay)Document5 pagesOutside The Window by David Naga (Essay)David NagaNo ratings yet

- Cost-Effectiveness Evidence - A Case Study: How To Use This DocumentDocument3 pagesCost-Effectiveness Evidence - A Case Study: How To Use This DocumentPragnesh ChauhanNo ratings yet

- 1331907497-Montasseretal 2011BJMMR1038Document12 pages1331907497-Montasseretal 2011BJMMR1038puppyhandaNo ratings yet

- Expanded Program On ImmunizationDocument4 pagesExpanded Program On ImmunizationKrizle AdazaNo ratings yet

- Chapter OneDocument8 pagesChapter OneHOPENo ratings yet

- Prognostic Factors and OutcomesDocument7 pagesPrognostic Factors and Outcomesyikeberabebaw123No ratings yet

- Long Covid RevDocument9 pagesLong Covid RevJorge Dávila GonzálezNo ratings yet

- Vaccine: SciencedirectDocument10 pagesVaccine: SciencedirectNenqx Inthandt C'bunqxzu TheaNo ratings yet

- Dr. Eaton DeclarationDocument47 pagesDr. Eaton DeclarationJonece DuniganNo ratings yet

- FundingModel TBAndHIVConceptNote Final Ethiopia Oct15 2014Document94 pagesFundingModel TBAndHIVConceptNote Final Ethiopia Oct15 2014tokumaNo ratings yet

- Beyond One Health: From Recognition to ResultsFrom EverandBeyond One Health: From Recognition to ResultsJohn A. HerrmannNo ratings yet

- Dog BiteDocument24 pagesDog BitekranthichokkakulaNo ratings yet

- Health Check Consent FormDocument4 pagesHealth Check Consent Formaxenic04No ratings yet

- Polio Eradication: Pulse Polio Programme: A.Prabhakaran M.SC (N), Tutor, VMACON, SalemDocument13 pagesPolio Eradication: Pulse Polio Programme: A.Prabhakaran M.SC (N), Tutor, VMACON, SalemPrabhakaran Aranganathan100% (3)

- Cough and Colds, Fever, Asthma Topical: Headache, Skin Diseases Diuretics Anti - FungalDocument7 pagesCough and Colds, Fever, Asthma Topical: Headache, Skin Diseases Diuretics Anti - FungalElpijong Mijares JugalbotNo ratings yet

- Standardized Health Messages Book (With Bookmarked Headings) PDFDocument350 pagesStandardized Health Messages Book (With Bookmarked Headings) PDFKyaw Zaw HeinNo ratings yet

- Tetanus 2014Document32 pagesTetanus 2014Vanya Tri WindisariNo ratings yet

- Splenectomy: DisclaimerDocument5 pagesSplenectomy: DisclaimerMimi FatinNo ratings yet

- Framework of National Cancer Control Program in IndonesiaDocument20 pagesFramework of National Cancer Control Program in IndonesiaIndonesian Journal of Cancer100% (3)

- Final Pmmvy (Faq) Bookelt PDFDocument18 pagesFinal Pmmvy (Faq) Bookelt PDFrajat jainNo ratings yet

- What Is Polio?: SymptomsDocument2 pagesWhat Is Polio?: SymptomsJP LandagoraNo ratings yet

- Bill Gates Bio & History: Who Is Bill Gates?Document12 pagesBill Gates Bio & History: Who Is Bill Gates?ChristCarrieMeNo ratings yet

- ABC's of Primary Health Care...Document24 pagesABC's of Primary Health Care...rhenier_ilado100% (7)

- "Expanded Program On Immunization": Angeles University FoundationDocument12 pages"Expanded Program On Immunization": Angeles University FoundationJaillah Reigne CuraNo ratings yet

- Acs Ca3 BookDocument69 pagesAcs Ca3 BookchrisNo ratings yet

- 085 The Crab Tales 29 April To 12 MayDocument20 pages085 The Crab Tales 29 April To 12 MayElizabeth KingNo ratings yet

- Landasan Teori Tetanus GeneralisataDocument22 pagesLandasan Teori Tetanus GeneralisataadityaNo ratings yet

- Anti Fungal Susceptibility TestingDocument13 pagesAnti Fungal Susceptibility TestingMohamed75% (4)

- Generic Risk Assessment New and Expectant MothersDocument10 pagesGeneric Risk Assessment New and Expectant MothersBga ArmyNo ratings yet

- Health INDICATORSDocument30 pagesHealth INDICATORSYeontan Kim100% (1)

- 06SMARTeZ Drug Stability Table Non USDocument2 pages06SMARTeZ Drug Stability Table Non USJessica Blaine BrumfieldNo ratings yet

- CDC Healthcare Personnel Vaccination RecommendationsDocument1 pageCDC Healthcare Personnel Vaccination RecommendationsdocktpNo ratings yet

- Moving Target Vaccines Thimerosol and AutismDocument25 pagesMoving Target Vaccines Thimerosol and AutismcirclestretchNo ratings yet

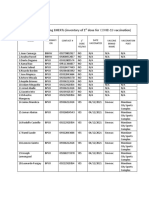

- Barangay Mantuyong Bherts (Inventory of 1 Dose For Covid-19 Vaccination)Document1 pageBarangay Mantuyong Bherts (Inventory of 1 Dose For Covid-19 Vaccination)Barangay CentroNo ratings yet

- Unit 10 Under My SkinDocument26 pagesUnit 10 Under My SkinYanz MuhamadNo ratings yet

- CPM17th RabiesDocument15 pagesCPM17th RabiesMae DoctoleroNo ratings yet

- Amniocentesis HindiDocument6 pagesAmniocentesis HindiRohit KumarNo ratings yet

- Surgical Prophylaxis: Prepared By: Gerard-IanDocument10 pagesSurgical Prophylaxis: Prepared By: Gerard-IanGerard-Ian de VeraNo ratings yet