Professional Documents

Culture Documents

The Dates of Procopius' Works: A Recapitulation of The Evidence

The Dates of Procopius' Works: A Recapitulation of The Evidence

Uploaded by

Ivanovici DanielaOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

The Dates of Procopius' Works: A Recapitulation of The Evidence

The Dates of Procopius' Works: A Recapitulation of The Evidence

Uploaded by

Ivanovici DanielaCopyright:

Available Formats

The dates of Procopius' works: A recapitulation of the evidence

Evans, J A S

Greek, Roman and Byzantine Studies; Fall 1996; 37, 3; ProQuest

pg. 301

The Dates of Procopius' Works:

A Recapitulation of the Evidence

]. A. S. Evans

UARTER CENTURY AGO, the dates when Procopius of Caesarea published his works in the reign of Justinian

were considered more or less settled. 1 They were all

thought to have appeared in the first five years or so of the

550s. The first seven books of the History of the Wars of

Jus tin ian (hereafter Wars) were published in 550/551. The first

two books of this work, which treat the wars on the eastern

frontier, bring the narrative up to 549. The third and fourth

books, on the African war, end for practical purposes in 545,

but a brief addendum brings the story up more or less to midcentury. Books five to seven, on the war in Italy against the

Ostrogoths, end with a Slavic inroad into the Balkans made in

the winter of 550-551, penetrating as far as the Long Wall or

"Anastasi an Wall," which extended from the Sea of Marmora to

the Black Sea west of Constantinople. Book eight of the Wars,

which was added later, begins with a preface that implies that

the first seven books were published together more or less at

the same time. So if the inference is to be taken literally, then

the terminus post quem for Wars 1-7 is 551.

Thus the conclusion seemed firm that Procopius was revising

his notes in the 540s and published in 550-551. In fact, much of

his Wars must have reached the state in which we have it by

545. There is internal evidence that Procopius' account of the

great siege of Rome by the Ostrogoths, which lasted from

February 537 to mid-March 538, reached its present form by

N.

1 The following abbreviations will be used: CAMERON (1967)=A. Cameron,

Procopius: History of the Wars, Secret History and Buildings (New York

1967); CAMERON (1985)=A. Cameron, Procopius and the Sixth Century (Berkeley 1985); EvANS (1972)=]. A. S. Evans, Procopius (New York 1972); EvANS

(1996)=]. A. S. Evans, The Age of Justinian: The Circumstances of Imperial

Power (London 1996); STEIN=E. Stein, Histoire du Bas-Empire II, ed. J.-R.

Palanque (Amsterdam 1949).

301

Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission.

302

THE DATES OF PROCOPIUS' WORKS

545, perhaps even a year earlier. 2 Possibly he intended publication in 545: his old commander Belisarius was sent back to

Italy in 544 to deal with the deteriorating situation there, and

Procopius may have believed that a general of Belisarius' calibre

would quickly set things right and the time would soon be ripe

for publication. But Belisarius failed; the war dragged on, and

Procopius was left without a natural conclusion for his history.

Even at mid-century he lacked a good stopping-point. Nonetheless he did stop there, and we must settle on 551 as the

earliest date by which the first seven books of the Wars were

made available to the small reading public in Constantinople.

That much is generally agreed, though there is one small caveat.

The proem of the Anekdota implies that it was begun after the

complete Wars 1-7 had been made public in 551, and the date of

the Anekdota still accepted by most scholars is 549-550. 3

In dispute are the dates of Procopius' other works: the

Buildings, the Anekdota, and the eighth book of the Wars,

which serves as a sequel to the seven books already published

and brings the narrative down to the victory over the Ostrogoths, won not by Belisarius but by his rival Narses. I had a part

in reopening this dispute, which has now taken on a life of its

own. Twenty-five years ago, the scenario went like this. About

554 Procopius added an eighth book to his Wars. The Anekdota

was not published in the sense that it was made available to a

reading public, but internal evidence points to the date of composition: four times 4 Procopius states that Justinian's administration of the empire had lasted 32 years, and this is taken

to mean 32 years at the time of writing. Now it is clear that both

in the Buildings and the Anekdota, Procopius considered

Justinian the real ruler during the reign of his uncle Justin, and

put the start of Justinian's regime not at 527, when Justinian

himself became emperor, but at 518, when Justin ascended the

throne. So a century ago, Jacob Haury, the editor of the

2 Wars 6.5.24-27. J. Haury (Procopiana [Augsburg 1890-91] Sf), and before

him, W. Teuffel (Studien und Charakteristiken zur griechischen und romischen sowie zur deutschen Literaturgeschichte [Leipzig 1871]) both date this

passage to 545. But see Evans (1972) 138 n.57.

3 Stein II 720; J. B. Bury, History of the Later Roman Emprie (London

1923) II 422; B. Rubin, "Prokopios von Kaisareia," R E 23.1 (1957) 354f;

Cameron (1985) 9.

4 Anec. 18.33; 23.1; 24.29, 33. At Anec. 18.45 Procopius distinguishes between

the reign of Justin I and that of Justinian, making it clear that he considered

Justinian responsible for both periods.

Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission.

]. A. S. EVANS

303

Teubner Procopius, 5 argued that the 32 years of Justinian's rule

in the Anekdota should be counted from 518, not 527, and

consequently the Anekdota was composed in 549-550, rather

than 559, as such earlier scholars as Felix Dahn and Wilhelm

Teuffel had believed and some, among them Comparetti, continued to believe. 6 What happened to the Anekdota after its

completion we do not know. Unknown both to Photius and to

Constantine VII Porpyrogenitus, it is first mentioned in the

Suda,; and in the early seventeenth century, it turned up in the

Vatican Library and was published by the Vatican librarian,

Nicolas Alemmani {see Comparetti xlvii-xlix). Such was the

accepted view twenty-five years ago, and it is still accepted by

many scholars-notably Averil Cameron, whose book on

Procopius {1985) is the best in the field-and has recently been

ably defended by Geoffrey Greatrex.? I shall not attempt to

disprove the consensus here. But the difficulties it presents

should not be underestimated, and it is time to look again at the

evidence.

First, the Buildings. It is a remarkable compendium of information that must depend on archives, and there are grounds for

placing it later than Wars 8. 8 Two items appear to date it

securely {Evans [1972] 43, 139 n.70). One is Procopius' description of Justinian's repairs to portions of the Anastasian Wall, or

Long Wall, in Thrace, "which had suffered" {presumably from

enemy attacks to which Procopius had just alluded), and the

rebuilding of the walls of Selymbria where the Anastasian Wall

met the Sea of Marmora (4.9.9-13). This Anastasian Wall was

5 Haury (supra n.2) 9-16, and "Zu Prokops Geheimgeschichte," BZ 34

(1934) 10-14.

6 F. Dahn, Prokopius von Cisarea. Ein Beitrag zur llistoriographie der

Volkerwanderung und des linkenden Romerthums (Berlin 1865) 53; Teuffel

(supra n.2) 217, who places the Anekdota in 558/559 just before Belisarius' victory over the Kutrigur Huns in 559; D. CoMPARETII, ed., Le inedite libra none

del~~ Isto:_~e di Procopio di Cesarea (Rome 1928): hereafter 'Comparetti')

XXXll- XXXIII.

7 Cameron (1967) xxxiii, (1985) 8; G. Greatrex, "The Dates of Procopius'

Works," BMGS 18 (1994) 101-14.

8 The evidence rests on two passages: ( 1) Bldg s. 6.1.8 makes a crossreference to Wars 8.6; (2) Wars 8.7.8f professes ignorance about the course of

the river that flows through Dara, whereas by the time Procopius wrote

Bldgs. 2.2.15f, he was aware that it flowed to Theodosiopolis. Cf Greatrex

(supra n.4) 1OS f. Cross-references in Procopius are insecure evidence, but nonetheless the conclusion that Wars 8 antedates the Buildings is generally

accepted.

Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission.

304

THE DATES OF PROCOPIUS' WORKS

pierced by a Bulgar raid in 539 or 540, and in late 550, an

incursion of Slavs reached the wall but may not have crossed it

before they were turned back. 9 It is not impossible that

Procopius is referring to one or other of these attacks. But the

incident that best fits Procopius' testimony occurred in 559,

when the Kutrigur Huns did overrun the wall, which they

found in disrepair. After they were repulsed, Justinian in person went out to Selymbria; making it his base, he supervised the

rebuilding of the wall, and presumably the reconstruction of

Selymbria's circuit as well. For this we have dated evidence in

Theophanes (A.M. 6051). Second, Procopius mentions the start

of construction of a bridge over the Sangarios River: "Having

already begun the task, he is now much occupied with it, and I

know he will complete it not long hence" (5.3.10, tr. Downey,

LCL). Theophanes (A.M. 6052) dates the start of construction

to A.M. 6052 (559- 560). So a terminus post quem of 560 seems

in order.

Ernst Stein (720) was the first to dissent. He set aside Theophanes as unreliable and, in any case, referring to the completion of the bridge, not the start of construction (this involves a

misreading of Theophanes' text). He swept aside the evidence

of the repairs to the Long Wall, connecting them instead with

the Bulgar raid of 540. Then he put forward three arguments

from silence to support a date of no later than 555. The

Buildings failed to mention the Samaritan revolt of midsummer 556 or the rebellion of the Tzani near Trebizond in 557,

as well as the partial collapse of the dome of Hagia Sophia on 7

May 558. The omission of the Tzani and the Samaritans need

not surprise us. Both were examples of failed policy, and

mention of these incidents would have been both unwelcome

and undiplomatic in a panegyric delivered in the 550s. Arguments from silence are particularly weak in panegyrics, for

the encomiast's choice of what events to include or exclude is

never based on a resolve to tell the whole truth. But Stein's

third point-Procopius overlooks the fall of Hagia Sophia's

dome-does have real weight, for in the first book of the

Buildings Procopius told how this dome was raised and used it

as a special example of Justinian's divine inspiration. Twice,

when the master builders were at a loss and the unfinished

9

Evans (1996) 79, 150, 223; V. Popovic, "La descente des Kutrigurs, des

Slaves et des Avars vers la mer Egee: le temoinage de l'archeologie," CRAI

( 1978) 607f.

Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission.

]. A. S. EVANS

305

structure threatened to collapse, Justinian, despite his lack of experience in engineering, gave them the technical advice that was

needed. The dome was presented as evidence of Justinian's

special relationship with God: a concrete illustration of the

emperor's role as God's vicegerent. If the first book of the

Buildings was published in Constantinople after the dome collapsed-a matter of common knowledge in the city-there

would have been a distinct flavor of irony to these passages that

exalt Justinian's divine inspiration. Irony is unsuitable for a

panegyric, especially one intended for an emperor who took his

special relationship with God very seriously.

So Stein put the whole work before 555, and his redating has

been generally accepted. One notable dissenter was Glanville

Downey, who continued to prefer 559/560. His argument was a

variant of one proposed by Haury: 10 the first book of the Buildings was composed initially as an encomium to be read before

the imperial court, and Procopius passed over the collapse of

the dome because it detracted from the emperor's glory as a

builder. Later Procopius padded the work with five more

books dealing with the imperial building program throughout

the empire, with the exception of Italy. Their literary quality

compares poorly with that of the first book, which seems to

indicate that the Buildings was left unfinished. Michael Whitby,11 who has reviewed the question recently, prefers the

hypothesis that the work belongs to 560-561, after the structural damage to the dome had been repaired, and that Procopius

omitted all reference to the collapse in order to avoid giving

offense. An omission so obvious, however, would have been

itself intrinsically offensive. My own suggestion, which I put

forward a quarter century ago and still prefer, developed

Downey's theory further: the first book, which was delivered

before an invited audience as a panegyric, dates to before the

collapse of the dome, and the following books were added at a

later date, probably with the emperor's encouragement.

Nothing in the first book can be dated certainly after 557,

whereas the references to the repair of the Long Wall in Thrace

and the bridge on the Sangarios are found in books four and

10

G. Downey, "The Composition of Procopius' De Aedificiis," TAPA 78

{1947) 171-83; "Notes on Procopius, De Aedificiis Bk. 1," in G. Mylonas, ed.,

Studies Presented to D. M. Robinson {St Louis 1953) II 719-25; Constantinople in the Age of Justinian (Norman [Ok.] 1960) 95; Haury (supra n.2) 27f.

11

Justinian's Bridge over the Sangarius and the Date of Procopius' De

Aedificiis," JHS 105 (1985) 143.

Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission.

306

THE DATES OF PROCOPIUS' WORKS

five respectively. The unevenness of the work argues for

incompleteness, though the omission of Italy does not, for Justinian built nothing there to attract the attention of a panegyrist.12 But why should the Buildings be left incomplete, if it

was? The best solution is to suppose that Procopius was interrupted by death. For that, there is no proof, but it adds some

weight to the hypothesis that the Buildings is a late work.

Next, the eighth book of the Wars. Again there is internal evidence. In 545, Justinian made a five-year treaty with Persia

whereby he agreed to pay 2,000/ounds of gold over the term

of the treaty. It expired in 550 an eighteen months later was renewed for a five-year term for another 2,000 pounds, plus 600

pounds to make up for the 18 months when there was no

treaty. This aroused Procopius' indignation; at Wars 8.15.17 he

exclaims that at the present time-that is, presumably, the time

of writing-the Persian king had collected 4,600 pounds of gold

over a space of eleven years and six months. The "present

time" must be 11 years and 6 months after 545. So the eighth

book can hardly have been completed earlier than 557 (Evans

[1972] 43, 138 n.68).

But that is not the generally accepted date. Yet the only

scholar who has attemped to mount a reasoned argument

against the evidence of Wars 8.15.17 is Greatrex (supra n.4),

whose view is that the "eleven years and six months" is a round

number and should not be taken as an exact statistic. He finds a

12

Evans (1996) 224f; the church of San Vitale at Ravenna, which might

appear an exception, was not financed by the imperial treasury but by a local

banker, Julius Argentarius. G. Greatrex, uProcopius and Agathias on the

Defenses of the Thracian Chersonese," in C. Mango and G. Dagron, edd.,

Constantinople and its Hinterland: Papers from the Twenty-Seventh Spring

Symposium of Byzantine Studies (Aldershot 1995) 125-29, has put forward

two other arguments from silence in support of Stein's date for the

composition of the Buildings: first, at Bldgs. 4.10.9 Procopius refers to the Hun

attack of 540 on the Thracian Chersonese as "recent"; second, he fails in the

same passage to mention the successful defense of the Chersonese wall by

Germanus, son of Dorotheus against the Kutrigurs in 559 (126). Greatrex also

points to another "major difficulty" for those who date the first book before

the collapse of Hagia Sophia's dome in 558: the allusion at Bldgs. 1.1.16 to the

conspiracy against Justinian of 548-549, where Procopius states that the

officers convicted of conspiracy were pardoned and still held their offices and

rank. This claim, Greatrex argues, would have been inaccurate and

inappropriate twelve years after the conspiracy. This was, however, a passage

intended to celebrate Justinian's clemency and may, in fact, have become

more appropriate for mention in a panegyric once the actual memory of the

conspiracy had faded.

Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission.

J. A. S. EVANS

307

parallel at Wars 1.27.40, where Procopius writes that the Lakhmid Sheikh al-Mundhir terrorized the eastern frontier for fifty

years. Al-Mundhir died in June, 554, and Greatrex dates his

accession to ca 505. 13 So his terrorism had not lasted for exactly

fifty years when this passage was written, no later than 551. 14

Greatrex suggests that the "eleven years and six months" is a

similar example of numerical inexactitude. But that will not do.

Classicists may be forgiven for calling the space between the

Persian Wars and the Peloponnesian War in the fifth-century

B.C. the Pentekontaetia, the 'fifty-year period', even though 431

subtracted from 478 does not yield 50; but if one were to say

that 50 years, 3 months, and 2 weeks elapsed between the two

wars, the mistake would not be overlooked. Round numbers

may be used in a generalized sense, but precise numbers convey precision, and Procopius was aware of the difference. Both

his "eleven years and six months" and the 4,600 pounds of gold

that were paid out over that period are precise numbers.

If one is determined to find a way around this morsel of

evidence, there is a better method for doing so, which I pointed

out in my book on Procopius (Evans [1972] 138 n.68). In 545

Justinian preferred to make his payment to Persia in a lump

sum to avoid the appearance of paying annual tribute. Thus Procopius' meaning may only be that 4,600 gold pounds had been

paid to Persia in return for eleven years and six months of

peace, and hence no date for the composition of this passage is

implied. Procopius's text, however, reads: "up to a period of

eleven years and six months at the present time, six and forty

centenaria have been paid;" and as Procopius regarded the

payment as a shameful annual subsidy, regardless of Justinian's

maneuvre to disguise the fact, no one who reads this passage

without an ulterior motive would think that "the present time"

was anything other than eleven years and six months after 454.

There is, however, an ulterior motive, for the Buildings post13 I. Shahid, Byzantium and the Arabs in the Sixth Century I (Washington

1995) 13ff, 306, dates the death of Mundhir's father Nu'man to AugustSeptember 503 and Mundhir's own death to June 554. There is some evidence

for a brief interregnum between Nu'man's death and the start of Mundhir's

reign, and hence Mundhir may have ruled almost exactly fifty years: a striking

coincidence if so.

14

Or possibly before 545, though it might have been inserted in the text just

before the final publication date of 550-551. Shahid (supra n.13: 306) argues

that this passage must have been written after Mundhir's death, which would

make it the latest passage in Wars 1-7, with implications for the final publication date of Wars 1-7.

Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission.

308

THE DATES OF PROCOPIUS' WORKS

dates the eighth book of the Wars (see supra n.S), and if the

"eleven years and six months" points to a date of 557, then

Stein's early dating for the Buildings cannot stand.

Now the Anekdota. Haury's date of 550 is generally accepted.

The preface of the Anekdota sets out its purpose. Procopius

claims that he has already narrated the wars according to time

and place: that is, he has divided them into three sections

according to geographical area. But only the first seven books

of the Wars use this plan; the eighth book does not. Moreover,

the Anekdota has twenty references to Wars 1-7, but none to

Wars 8. 15 It follows, therefore, that the proem of the Anekdota

refers only to the first seven books of the Wars and not to their

sequel. Thus there can be no doubt about what the Anekdota

purports to be. It claims to be a malevolent commentary on

Wars 1-7, which Procopius composed after the Wars was published. It is an early experiment in the technique that Laurence

Durrell used brilliantly in his Alexandria Quartet, except that

the two personae who serve as authors of the Anekdota and the

Wars respectively are both Procopius himself. Procopius

asserted that he had long wanted to write this work, but was

deterred at first by the fear that when his readers learned of the

sins of Justinian and Theodora, they might want to imitate

them. But eventually he changed his mind as he recollected that

potentates of later generations would realize from the examples

of Justinian and Theodora that punishments follow misdeeds

and that their evil actions will be matters of record. All this is a

rhetorical topos, but it shows that Procopius wrote with an

educated reading public in mind. The Anekdota is an artful

essay: the Suda categorized it as invective and comedy ( cf

Cameron [1967] xxix). Are we to take what it implies about its

date of composition at face value? Or should the repeated

references to thirty-two years of Justinian's rule be taken as

examples of Procopius' art rather than his accuracy?

I am not convinced that anything reported in the Anekdota

can be securely dated later than 550, except for the important

caveat that its preface implies that it was begun after Wars 1-7

was published, and Wars 1-7 could not have been published in

toto before 551. The stated aim of the Anekdota, however, was

to amplify Wars 1-7, and consequently we should not expect to

find references beyond the time limits of that work. Roger

15

Cf H. Dewing, "The Secret History of Procopius of Caesarea," TAPA 62

(1931) xl-xli; Haury (supra n.6) 10-14.

Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission.

J. A. S. EVANS

309

Scott, 16 however, has attempted to date two items later than 550.

The first is Procopius' charge that Justinian reduced the value

of the solidus by making it worth 180 bronze folies rather than

210 (Ane c. 25.12). Scott connects this with an entry in John

Malalas' Chronicle for 553 (18.117, p.486), which records a riot

of the poor in Antioch caused by a debasement of the coinage.

There may be a connection between the two reports, but it '

does not serve to date the Anekdota before 550. I have dealt

with this numismatic problem elsewhere (Evans [1996] 236f)

and will summarize here. Before the empress Theodora's death

in 548, P eter Barsymes introduced a lightweight solidus, and

this, I suspect, is what aroused Procopius' complaint, for its

most likely use was to pay the stipends of the militia, civil and

military. Thus Procopius' own income could have been

affected. What Malalas describes may have been a second stage

in this numismatic maneuver: an abortive attempt to tariff the

new lightweight solidus in Antioch at its old rate of 210 folies.

The result would be a devaluation of the bronze follis, which

the poor used for everyday purchases, and hence their rioting.

But whatever the truth of the matter, this report does not serve

as an indication of a post-500 date for the Anekdota.

Scott's second piece of evidence is the charge that Justinian

insisted that the Jews postpone Passover if it fell before Easter

(Anec. 28.16-19). There is no other evidence to support this

charge. C omparetti (185) attempted to connect it with an entry

for 545 in Theophanes, which records that Justinian attempted

to delay the Lenten fast by a week. How the Passover was

affected b y this is not clear, but Comparetti, who imagined that

Procopius wrote the Anekdota after he had retired to Caesarea,

thought that he heard some garbled oral traditions there about

what happened in 545, and added them to his list of Justinian's

crimes. Scott's solution is to connect this passage with the evidence from an Armenian source, Ananias of Shirak, 17 who

describes with some venom the intervention of an imperial

official named Iron in a conference held at Alexandria to determine the date of Easter for the churches that did not use the

table of T heophilus of Antioch, that is, the churches in Persia.

There are two difficulties with this solution. First, Iron's inter16 "Justinian's Coinage and Easter Reforms, and the Date of the Secret

History," BMGS 11 (1987) 215-21.

17

For a translation see F. C. Conybeare, "Ananias of Shirak (A.D. 600650c.)," BZ 6 (1897) 572-84.

310

THE DATES OF PROCOPIUS' WORKS

vention affected Christians living beyond the imperial boundaries, and it is not easy to understand how it would affect the

Jewish Passover within the empire. Second, the conference at

Alexandria to which Ananias refers dates to 562, too late for the

Anekdota, and hence Scott must postulate an earlier conference, presumably at Constantinople, held before 558-559,

which is his preferred date for the Anekdota, but after 550,

Haury's date for the Anekdota. Both Scott and Comparetti may

be right to this extent, that the Anekdota's charge is based on a

specific incident otherwise unrecorded, but it could also be

true that Procopius refers in this passage only to sporadic local

harassment of the Jews, which Justinian left unpunished. This

passage is insecure evidence for dating the Anekdota.

Two other points, however, require discussion. One concerns the relation between the Anekdota and the Buildings. The

portrayal of Justinian and Theodora in the one is the reverse of

the other, but that in itself proves nothing about the dates of

composition. But there is a troublesome cross-reference.

Among the natural calamities that Procopius cites in the Anekdota (18.38) to demonstrate God's rejection of Justinian was a

flood on the river Daisan (Greek "Skirtos") that inundated

Edessa, and he promises to describe it in logoi that he plans to

write. Dewing's translation is "as will be written by me in a

following book." This appears to be a reference to work that

was in the planning stage. We might reasonably expect this

work to be Wars 8, but nothing about the Skirtos flood occurs

there. Alternatively, we could suppose an unfulfilled intention,

but that is a desperate argument, for Procopius did write a

description of the flood on the Skirtos at Buildings 2.7.2-5.

Is this the cross-reference we are seeking? Cameron ([1985]

106f) accepts the possiblity: "Thus again, we can see how

closely the three works are linked, and how the Buildings slots

into Procopius' writing as a whole." So even while Procopius

was writing his secret diatribe against the Justinianic regime, he

intended a panegyric in support of that same regime. The

linkage that Cameron perceives is remarkable enough if we

accept her preferred date for the Buildings, for there would be a

gap of only four or at most five years between its publication

and the composition of the Anekdota; but if almost a decade

elapsed between the two works, we must believe that Procopius rlanned his writing schedule ahead to a remarkable

degree i we are to accept the linkage.

Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission.

J.

A. S. EVANS

311

There is a second difficulty as well. The passage that Dewing

translates "as will be written by me in a following book" has

been emended. The manuscript reading should be translated "as

will have been written by me in earlier logoi." Haury, the editor

of the Teubner Anekdota, was unhappy with this reading, and

changed an emprosthen to opisthen, although, as Comparetti

(257) was to point out, the logical meaning of Haury's emended

text is to refer not to the Buildings but to a later section of the

Anekdota itself. But before Haury edited the Teubner text with

this emendation, he had attempted another solution. He

suggested that the reference was to a lacuna at Wars 2.12.29,

where nine lines are missing from the manuscript at a point

where the subject is Edessa's famous relic: a letter from Christ

to the king of Edessa, Abgar. This is a solution that still attracts

Michael Whitby, 18 but it is based upon speculation, and rather

nebulous speculation at that. Haury himself abandoned it.

Another suggestion would be to accept emprosthen as the

correct reading but the verb form as a mistake for a perfect

tense, which was the solution of the Anekdota's first editor,

Alemanni. In that case the Anekdota would refer to the

Buildings as an earlier work, and we have come full circle to the

conclusion that the Anekdota was Procopius' last work: a jeu

d'esprit of his old age that purported to be a commentary on

the work that brought him fame, the seven books on the wars

of Justinian. This conclusion must be ruled out if we accept ca

550 as the date of the Anekdota 's composition. The most likely

solution is that the promise made in Anekdota 18.38 is fulfilled

in the Buildings, however much that may affect our assumptions about when and how these two works were composed.

The second problem concerns the connection between the

Anekdota and Wars 8. Their proems are sufficiently similar to

suggest a connection. Haury's dating of the former to 550

requires us to believe that the proem of Wars 8 borrows from

the Anekdota; whatever the truth of that, the similar proems

are circumstantial evidence for a linkage between the two

works. But Teuffel (supra n.2: 217f) also pointed out a possible

cross-reference, and his argument is worth recapitulating. At

Wars 8.25, Procopius refers to a composition on contemporary

ecclesiastical disputes that he will write. The subject was

18 Haury (supra n.2) 17f; Whitby (supra n.11) 144. Rubin (supra n.3: 573)

suggests two other cross-references between the Anekdota and the Buildings,

but these are rightly rejected by Whitby.

Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission.

312

THE DATES OF PROCOPIUS' WORKS

probably to be the "Three Chapters" controversy, but Procopius is imprecise. In the Anekdota there are several references to these later theological logoi, which Procopius would

write. At 10.15 he tells how Jus tin ian and Theodora promoted

ecclesiastical strife by pretending to disagree on theological

questions "as will shortly be related by me" (tr. Dewing, LCL).

At 11.33 there is another reference to this future composition,

and at 26.19 we learn that it will describe Justinian's treatment of

the clergy. A projected work describing the deposition of Pope

Silverius, which Procopius promised earlier (Anek. 1.14),

clearly points in the same direction. No trace of it has survived, nor is there any evidence that he ever wrote it. It is not

easy to believe that Procopius planned an ecclesiastical history

as a separate composition, for the ecclesiastical historian followed conventions far different from those of the secular historian. Thus there is merit to Teuffel's suggestion that these

promised logoi were to be a later section of the Anekdota,

which, if it was actually completed, has fallen out of the manuscript tradition, excised by monkish copyists or perhaps by

Procopius' literary executor. If so, Wars 8 refers to the Anekdota as a later work, or preferably, perhaps, as a work still in

progress while the eighth book was being written. That is

pushing the evidence hard. But at least it is clear that before

Procopius comrleted the Anekdota and Wars 8, he had formed

the intention o writing a composition on the "Three Chapters"

dispute, whereas there is an argument from silence to suggest

that he had not yet formed any such intention before he

completed Wars 1-7.

My conclusion is a modification of what I once proposed, but

the passage of time has bred caution: any conclusion must be to

some extent conjectural. Yet one can be attempted. The

terminus post quem is 551 for Wars l-7 and 557 for Wars 8. As

for the Anekdota, what it claims in its proem should be taken

seriously: it was begun after Wars 1-7 was published. Thus it

cannot have been composed as early as 550. Yet its subject was

the evils of the first thirty-two years of the Justinian regime,

beginning when Justin succeeded the good old emperor

Anastasius. The four references to a thirty-two year rule found

in the Anekdota indicate the span of time that Procopius

marked out as the scope of his essay; they do not attest a date of

composition. The work was intended as a sequel to Wars 1-7

and hence may have been composed at about the time

Procopius undertook Wars 8, which was also a sequel to Wars

Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission.

]. A. S. EVANS

313

1-7, and reuses the proem of the Anekdota. Buildings began as a

panegyric on Justinian's building program in Constantinople,

which was presented before the collapse of the dome of Hagia

Sophia, and this panegyric survives in the first book. The

following books were added at a later date. The unevenness of

the work suggests incompleteness; but incomplete or not, Procopius left off writing it in the early 560s, for he knew that construction had begun on the bridge over the river Sangarios, but

he did not know of its completion in 562. 19

We are left with conjectures and suppositions. They are sufficient to cast doubt on the dates for Procopius' works that are

still generally accepted.

UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA/UNIVERSITY OF WASHINGTON

February, 1997

19

Whitby (supra n.ll) 136-41.

Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission.

You might also like

- The Gunfighters (Time-Life, The Old West Series)Document246 pagesThe Gunfighters (Time-Life, The Old West Series)manlyduckling100% (6)

- The Atrahasis Epic by Alan Ralph MillardDocument301 pagesThe Atrahasis Epic by Alan Ralph Millardrody692No ratings yet

- Simplified CatechismDocument52 pagesSimplified CatechismrsiirilaNo ratings yet

- The Dates of The Anecdota and The de Aedificiis of ProcopiusDocument3 pagesThe Dates of The Anecdota and The de Aedificiis of ProcopiusManabu Marcus YanoNo ratings yet

- Parthia and The SeleucidsDocument5 pagesParthia and The Seleucidstemplecloud1No ratings yet

- Madgearu Avaro SlavicInvasions (576 626)Document27 pagesMadgearu Avaro SlavicInvasions (576 626)Vlad Mihai MihaitaNo ratings yet

- Vegetius On The Decay of The Roman ArmyDocument12 pagesVegetius On The Decay of The Roman ArmyPredrag Judge StanišićNo ratings yet

- 162 300 1 SMDocument6 pages162 300 1 SMAngelAldeaNo ratings yet

- Achyron or Proasteion. The Location and Circumstances of Constantine's Death PDFDocument9 pagesAchyron or Proasteion. The Location and Circumstances of Constantine's Death PDFMariusz MyjakNo ratings yet

- The Day of EleusisDocument41 pagesThe Day of Eleusistemplecloud1No ratings yet

- Bosworth1990 PDFDocument13 pagesBosworth1990 PDFSafaa SaiedNo ratings yet

- Periclean Imperialism Poly LowDocument30 pagesPericlean Imperialism Poly LowFelix QuialaNo ratings yet

- Capps E Page E T and Rouse D H W Thucydides History of The Peloponnesian War Book I and IIDocument512 pagesCapps E Page E T and Rouse D H W Thucydides History of The Peloponnesian War Book I and IIMarko MilosevicNo ratings yet

- 7.10 Craig S. Keener - Acts 10 - Were Troops Stationed in Caesarea During Agrippa's RuleDocument13 pages7.10 Craig S. Keener - Acts 10 - Were Troops Stationed in Caesarea During Agrippa's RuleCociorvanSamiNo ratings yet

- History of The Wars, Books I and II (Of 8) The Persian War by ProcopiusDocument141 pagesHistory of The Wars, Books I and II (Of 8) The Persian War by ProcopiusGutenberg.org100% (1)

- Procopius and DaraDocument20 pagesProcopius and DaraŞahin KılıçNo ratings yet

- Drinkwater DEXIPPUSDocument15 pagesDrinkwater DEXIPPUSlennart konigsonNo ratings yet

- The Chronological Accuracy of The "Chronicle" of Symeon The Logothete For The Years 813-845 @treadgold ®1979Document41 pagesThe Chronological Accuracy of The "Chronicle" of Symeon The Logothete For The Years 813-845 @treadgold ®1979forrestusNo ratings yet

- Patricii ValentinianiiiDocument16 pagesPatricii ValentinianiiiJaShongNo ratings yet

- Death ConstantineDocument9 pagesDeath ConstantineEirini PanouNo ratings yet

- Josephus 02 War 1-3Document782 pagesJosephus 02 War 1-3BernardiMatheusNo ratings yet

- Some Ghost Facts From Achaemenid Babylonian TextsDocument4 pagesSome Ghost Facts From Achaemenid Babylonian TextsDumu Abzu-aNo ratings yet

- De Blois Eis BasileaDocument10 pagesDe Blois Eis BasileaSteftyraNo ratings yet

- Amenhotep II and The Historicity of The Exodus PharaohDocument30 pagesAmenhotep II and The Historicity of The Exodus Pharaohsizquier66100% (1)

- (Zeitschrift Für Papyrologie Und Epigraphik Vol. 116) Anthony R. Birley - Hadrian and Greek Senators (1997) (10.2307 - 20189981) - Libgen - LiDocument38 pages(Zeitschrift Für Papyrologie Und Epigraphik Vol. 116) Anthony R. Birley - Hadrian and Greek Senators (1997) (10.2307 - 20189981) - Libgen - LiDirk SmuldersNo ratings yet

- Lintott LucanHistoryCivil 1971Document19 pagesLintott LucanHistoryCivil 1971Keir HeathNo ratings yet

- Dating War of HyksosDocument128 pagesDating War of HyksosZac Alexander100% (1)

- Memnon On The Siege of Heraclea Pontica by Prusias IDocument7 pagesMemnon On The Siege of Heraclea Pontica by Prusias IRecep VatanseverNo ratings yet

- 541 BC SardesDocument23 pages541 BC Sardesromario sanchezNo ratings yet

- Philadelphia - JohnLydus-4-08-August1Document6 pagesPhiladelphia - JohnLydus-4-08-August1KevinNo ratings yet

- Inscription From Pamphylia and Isauria (D. Hareward-JHS 78)Document22 pagesInscription From Pamphylia and Isauria (D. Hareward-JHS 78)Cemile KaracaNo ratings yet

- Walter Emil Kaegi. Two Notes On Heraclius. Revue Des Études Byzantines, Tome 37, 1979. Pp. 221-227.Document8 pagesWalter Emil Kaegi. Two Notes On Heraclius. Revue Des Études Byzantines, Tome 37, 1979. Pp. 221-227.Patrologia Latina, Graeca et OrientalisNo ratings yet

- Solomon and Shishak: Peter James Peter G. Van Der VeenDocument38 pagesSolomon and Shishak: Peter James Peter G. Van Der VeenJon Paul MartinezNo ratings yet

- Authorship of StrategikonDocument20 pagesAuthorship of StrategikonJoão Vicente Publio DiasNo ratings yet

- Was There A Carolingian Anti-WarmovementDocument14 pagesWas There A Carolingian Anti-WarmovementՅուրի Ստոյանով.No ratings yet

- The First Battles of The Chaeronea Campaign, 339/8 - .: Jacek RzepkaDocument7 pagesThe First Battles of The Chaeronea Campaign, 339/8 - .: Jacek RzepkaPetre BakarovNo ratings yet

- This Content Downloaded From 142.103.160.110 On Tue, 25 Aug 2020 18:15:57 UTCDocument8 pagesThis Content Downloaded From 142.103.160.110 On Tue, 25 Aug 2020 18:15:57 UTCSteve Fox100% (1)

- The Conquest of Khuzistan A Historiographical Reassessment - RobinsonDocument26 pagesThe Conquest of Khuzistan A Historiographical Reassessment - RobinsonDonna HallNo ratings yet

- Fomenko and English History With James PDocument14 pagesFomenko and English History With James PguilleNo ratings yet

- The Problem of The Marriage of The EmperDocument17 pagesThe Problem of The Marriage of The EmperborjaNo ratings yet

- The Problem of The Marriage of The EmperDocument17 pagesThe Problem of The Marriage of The EmperborjaNo ratings yet

- Vannoy Exodus-Esther Lecture2ADocument22 pagesVannoy Exodus-Esther Lecture2Aロサ イダNo ratings yet

- Galinsky 1968 Aeneid V and The AeneidDocument30 pagesGalinsky 1968 Aeneid V and The AeneidantsinthepantsNo ratings yet

- A New Perspective On Rome's Desert Frontier: Greg FisherDocument13 pagesA New Perspective On Rome's Desert Frontier: Greg FisherEmil KmeticNo ratings yet

- The Great Emperor A Motif in Procopius PDFDocument17 pagesThe Great Emperor A Motif in Procopius PDFVitor Henrique SanchesNo ratings yet

- Thucydides I Loeb IntroDocument13 pagesThucydides I Loeb Introph.maertensNo ratings yet

- Acta Classica XXI (: Archaeological EvidenceDocument13 pagesActa Classica XXI (: Archaeological Evidenceshshsh12346565No ratings yet

- Cambyses Transeuphratene 34 2007Document10 pagesCambyses Transeuphratene 34 2007Alshareef HamidNo ratings yet

- 13th Century Conquest Theory - Bryant WoodDocument16 pages13th Century Conquest Theory - Bryant WoodSImchaNo ratings yet

- The Date o F The Creation o F The Theme o F PéloponnèseDocument15 pagesThe Date o F The Creation o F The Theme o F PéloponnèseAgrinio12No ratings yet

- 10 2307@267080Document3 pages10 2307@267080Felipe MontanaresNo ratings yet

- Athens and Lefkandi A Tale of Two SitesDocument26 pagesAthens and Lefkandi A Tale of Two SitesЈелена СтанковићNo ratings yet

- On The Greek Martyrium of The NegranitesDocument17 pagesOn The Greek Martyrium of The NegranitesJaffer AbbasNo ratings yet

- Does Slavery Exists in Plato's RepublicDocument6 pagesDoes Slavery Exists in Plato's RepublicJuan Pablo GaragliaNo ratings yet

- Acc9500 2302Document4 pagesAcc9500 2302Noodles CaptNo ratings yet

- The Classical Association, Cambridge University Press Greece & RomeDocument16 pagesThe Classical Association, Cambridge University Press Greece & RomeDominiNo ratings yet

- Hatshepsut, The Queen of ShebaDocument37 pagesHatshepsut, The Queen of ShebaBranislav DjordjevicNo ratings yet

- The Great Revolt of The Egyptians (205-186 BC) : Image Courtesy of Willy ClarysseDocument13 pagesThe Great Revolt of The Egyptians (205-186 BC) : Image Courtesy of Willy ClarysseabduakareemNo ratings yet

- Emmet Sweeney - The Pyramid AgeDocument192 pagesEmmet Sweeney - The Pyramid AgeARCHEOMACEDONIA100% (1)

- History of the Wars, Books I and II The Persian WarFrom EverandHistory of the Wars, Books I and II The Persian WarRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (5)

- Martini2009 PDFDocument266 pagesMartini2009 PDFIvanovici DanielaNo ratings yet

- The Origin of The Soul: New Light On An Old Question: John YatesDocument20 pagesThe Origin of The Soul: New Light On An Old Question: John YatesIvanovici DanielaNo ratings yet

- p1 Final PublicDocument39 pagesp1 Final PublicIvanovici DanielaNo ratings yet

- Byzantine Bride-Shows and The Restoration of IconsDocument37 pagesByzantine Bride-Shows and The Restoration of IconsIvanovici DanielaNo ratings yet

- Eunuchs in Islam PDFDocument42 pagesEunuchs in Islam PDFIvanovici DanielaNo ratings yet

- Snare Gremmendp17Document51 pagesSnare Gremmendp17Ivanovici DanielaNo ratings yet

- At Home in The CityDocument17 pagesAt Home in The CityIvanovici DanielaNo ratings yet

- Bialecka-Pikul 2017. Advanced Theory of Mind in AdolescenceDocument13 pagesBialecka-Pikul 2017. Advanced Theory of Mind in AdolescenceIvanovici DanielaNo ratings yet

- Thematic Sessions of Free CommunicationsDocument946 pagesThematic Sessions of Free CommunicationsIvanovici DanielaNo ratings yet

- Bernard Gert Hobbes and Psychological EgoismDocument19 pagesBernard Gert Hobbes and Psychological EgoismIvanovici DanielaNo ratings yet

- Political Mutilation in Byzantine CultureDocument8 pagesPolitical Mutilation in Byzantine CultureIvanovici DanielaNo ratings yet

- Toward A Byzantine Definition of MetaphrDocument34 pagesToward A Byzantine Definition of MetaphrIvanovici DanielaNo ratings yet

- The Various Types and Roles of Eunuchs IDocument3 pagesThe Various Types and Roles of Eunuchs IIvanovici DanielaNo ratings yet

- Eusebius and Ephrem On Luke 1.36 - HandoutDocument2 pagesEusebius and Ephrem On Luke 1.36 - HandoutIvanovici DanielaNo ratings yet

- Tradition & Traditions: Carmelaram Theology CollegeDocument20 pagesTradition & Traditions: Carmelaram Theology CollegeIvanovici Daniela100% (1)

- De La Protectoratul Constantinian La Sacerdotiul ImperialDocument18 pagesDe La Protectoratul Constantinian La Sacerdotiul ImperialIvanovici DanielaNo ratings yet

- Chrysostum WoodDocument31 pagesChrysostum WoodIvanovici DanielaNo ratings yet

- Dementia On The Byzantine Throne (330-1453) : Originalarticle:Epidemiology, ClinicalpracticeandhealthDocument8 pagesDementia On The Byzantine Throne (330-1453) : Originalarticle:Epidemiology, ClinicalpracticeandhealthIvanovici DanielaNo ratings yet

- Shape The Future Listening Practice - Unit 3 - Without AnswersDocument1 pageShape The Future Listening Practice - Unit 3 - Without Answersleireleire20070701No ratings yet

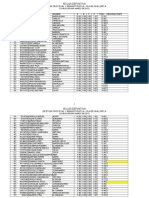

- Olimpiada de Limba Engleză - Etapa Pe Judeţ 22.02.2015: Nr. Crt. Numele Și Prenumele Elevului ClasaDocument36 pagesOlimpiada de Limba Engleză - Etapa Pe Judeţ 22.02.2015: Nr. Crt. Numele Și Prenumele Elevului ClasaCristina Capraru-DiaconescuNo ratings yet

- Repertoar SvadbaDocument12 pagesRepertoar SvadbaAmanda JarvisNo ratings yet

- History of AfricaDocument51 pagesHistory of AfricaLorie-ann VisayaNo ratings yet

- Biografi Lionel Messi Dalam Bahasa Inggris Dan Artinya TerbaruDocument4 pagesBiografi Lionel Messi Dalam Bahasa Inggris Dan Artinya TerbaruAndrizal100% (1)

- Identify The Experiences Rizal Had Abroad That Helped Shape His Nationalist SensibilitiesDocument3 pagesIdentify The Experiences Rizal Had Abroad That Helped Shape His Nationalist SensibilitiesEriane Garcia67% (3)

- Terduga TBCDocument86 pagesTerduga TBCataNo ratings yet

- Quiz On Girl Child by Prepared by Population First, MumbaiDocument16 pagesQuiz On Girl Child by Prepared by Population First, MumbaiVibhuti PatelNo ratings yet

- Don Quixote: About The AuthorDocument3 pagesDon Quixote: About The AuthorP TruNo ratings yet

- Bulakenyo PersonalitiesDocument5 pagesBulakenyo PersonalitiesEy BagayNo ratings yet

- FI56Document6 pagesFI56DELTANETO SLIMANENo ratings yet

- Bo de Thi Giua Hoc Ki 1 Mon Tieng Anh Lop 6 Co Dap AnDocument29 pagesBo de Thi Giua Hoc Ki 1 Mon Tieng Anh Lop 6 Co Dap AnDiệu NguyễnNo ratings yet

- Ethnic Problems and Movements For DarjeelingDocument23 pagesEthnic Problems and Movements For Darjeelingravee12No ratings yet

- Traditional Indonesian HouseDocument8 pagesTraditional Indonesian HouseFaye Marielle AutajayNo ratings yet

- A225 PDFDocument131 pagesA225 PDFElizabeth E. FetizaNo ratings yet

- Irish Plays and Playwrights by Weygandt, Cornelius, 1871-1957Document156 pagesIrish Plays and Playwrights by Weygandt, Cornelius, 1871-1957Gutenberg.orgNo ratings yet

- International MediaDocument10 pagesInternational MediaLekha JauhariNo ratings yet

- Dơnload The History of Video Games 1st Edition Charlie Fish Full ChapterDocument24 pagesDơnload The History of Video Games 1st Edition Charlie Fish Full Chapterobohoashadh100% (6)

- Sto. Nino Prayer With ImprimaturDocument17 pagesSto. Nino Prayer With ImprimaturOrman O. ManansalaNo ratings yet

- The Question of - Eclecticism - Iraklis KarabatosDocument1 pageThe Question of - Eclecticism - Iraklis KarabatosiraklisNo ratings yet

- Ese Nigerian Meaning - Google SearchDocument1 pageEse Nigerian Meaning - Google SearchEse VerereNo ratings yet

- P 1 December 21Document1 pageP 1 December 21hlaldinmawiaNo ratings yet

- Harri Kettunen and Christ Hope Helmke - Introduction To Maya Hieroglyphs. Fifth Edition, 2010Document165 pagesHarri Kettunen and Christ Hope Helmke - Introduction To Maya Hieroglyphs. Fifth Edition, 2010genovoffa100% (1)

- Luis Miguel - Sabor A Mi SOLO PDFDocument5 pagesLuis Miguel - Sabor A Mi SOLO PDFLuis Navarrete VelasquezNo ratings yet

- Gestion Procesal Y Administrativa - Isla de Mallorca: #DNI Apellidos Nombre A B C D Total ObservacionesDocument46 pagesGestion Procesal Y Administrativa - Isla de Mallorca: #DNI Apellidos Nombre A B C D Total Observacionesanon_135132518No ratings yet

- Olaudah EquianoDocument14 pagesOlaudah EquianoMYKRISTIE JHO MENDEZNo ratings yet

- S5R-Fikri-Gestion Financière-Section 1Document20 pagesS5R-Fikri-Gestion Financière-Section 1ayoubNo ratings yet

- Indian Political Thought Block 2 PDFDocument111 pagesIndian Political Thought Block 2 PDFआई सी एस इंस्टीट्यूट0% (1)