Professional Documents

Culture Documents

PDF

Uploaded by

Ash ShakurOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

PDF

Uploaded by

Ash ShakurCopyright:

Available Formats

Distant Voices: The Views of the Field Workers of NGOs in Bangladesh on Microcredit

Author(s): Mokbul Morshed Ahmad

Source: The Geographical Journal, Vol. 169, No. 1 (Mar., 2003), pp. 65-74

Published by: Wiley on behalf of The Royal Geographical Society (with the Institute of British

Geographers)

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3451540 .

Accessed: 06/02/2015 00:34

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at .

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of

content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms

of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Wiley and The Royal Geographical Society (with the Institute of British Geographers) are collaborating with

JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Geographical Journal.

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded from 119.148.3.126 on Fri, 6 Feb 2015 00:34:27 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

The GeographicalJournal,Vol. 169, No. 1, March2003, pp. 65-74

Distant

the

voices:

NGOs

in

views

of

Bangladesh

the

on

field

workers

of

microcredit

MOKBULMORSHEDAHMAD

Departmentof Geographyand Environment,Universityof Dhaka, Dhaka 1000, Bangladesh

E-mail:dgg3mma@hotmail.com

Thispaper was accepted for publication in October 2002

Recently, microcredit has become a fashionable cure-all for most non-governmental

organizations (NGOs) in Bangladesh. The provision of services to the poor is by definition

always difficult, and even NGOs have problems. NGOs in Bangladesh define the poor in

differentways when creating their targetgroups. The policies of nearly all NGOs in Bangladesh

are formulated by their senior managers, and field workers are rarelyconsulted. This paper will

explore the opinions on microcredit of selected field workers of four types of NGOs in

Bangladesh - on how the problem of microcredit might be solved. Problems of microcredit

programmes, they say, include non-accessibility to the poorest, low return, misuse and

overemphasis on repayment. Field workers discuss what level of importance should be given

to microcredit as against services like education, health or awareness creation. Most conclude

that NGOs are overemphasizing microcredit, which leaves little time and few resources for

other problems of the poor, so bringing the whole 'development' effort of the NGOs into

question. Most field workers think that many microenterprisesare not sustainable and that in

many cases clients will remain dependent on the NGOs for credit.

KEY

WORDS:Bangladesh, NGOs, microcredit, poverty

in the world. ADAB (the Association of Development

Agencies in Bangladesh) had a total membership of

articlereviewsacademic writingsand what non- 886 NGOs in December 1997 (ADAB 1998), but the

governmental organization (NGO) field workers ADAB directory lists 1007 NGOs including 376 nonhave told me about specific aspects of microcredit. member NGOs. The NGO Affairs Bureau of the

Inmy view, field workersof NGOs are yet anotherunder- Government of Bangladesh (GOB), which approves all

utilized resource. I have therefore worked with the foreign grantsto NGOs working in Bangladesh,released

field workers of four types of NGOs of differing sizes grants totalling around US$250 million in the financial

in Bangladesh, each in one locality: one international year 1996-97 to 1132 NGOs of which 997 are local

NGO, MCC (Mennonite Central Committee) Bangla- and 135 are foreign (NGO AffairsBureau 1998). NGOs

one regional have mainly sought to service the needs of the landless,

desh; one large national NGO, PROSHIKA;

NGO, the RDRS (Rangpur-Dinajpur Rural Service)

usuallywith foreign donor funding as a counter-initiative

Bangladesh; and three small NGOs/GROs, which are to the state's efforts (Lewis 1993).

NGO initiatives in establishing income-generating

'partners'of SCF (Save the Children UK) Bangladesh'.

The field work for this article was conducted

activities have proved to be an effective alternative to

between September 1998 and May 1999. Participant top-down state programmes of rural works, but the

observation, semi-structured interviews and informal extremely low rates of return on such activities have

discussions with the field workers of NGOs, clients and caused many to question their long-term sustainability

mid-level and senior managerswas used in the research. (Ahmad and Townsend 1998). NGO relations with

To obtain basic information on the field workers, 109 their clientele appear to have become increasingly

were interviewed by questionnaire.

credit-oriented, and there are now more restrictive

There are probably more and bigger NGOs in Bang- rules (such as compulsory savings), all of which militate

ladesh than in any other country of a similar population against participatory procedures. The likelihood of

Introduction

This

@ 2003 The Royal Geographical Society

0016-7398/03/0001-0065/$00.20/0

This content downloaded from 119.148.3.126 on Fri, 6 Feb 2015 00:34:27 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

66

The views of the field workersof NGOs in Bangladeshon microcredit

Originally a branch of an international NGO, the

LutheranWorld Federation, it became a national NGO

in 1997 (RDRS 1997). I worked in KurigramDistrict

and again found the work of this NGO had changed

from relief to microcredit.

SCF (Save the Children UK) is one of the leading

international NGOs of Bangladesh. Work started in

Bangladesh soon after independence in 1971. One

major activity of SCF (UK) is to enable its beneficiaries

to cope with floods, which frequently cause major disasters in Bangladesh. SCF (UK)has Coping with Flood

programmes in various flood-prone districts in Bangladesh. In Shariatpur, south-west of Dhaka, SCF (UK)

decided in 1996 to hand over its activities and

resources to local NGOs due to high operating costs.

The 22 formerSCF(UK)field workers formed three new

NGOs and are working as 'partners'of SCF(UK).Their

work is now all in microcredit, despite SCF(UK)'spublished preference for emphasis on social problems in

Bangladesh, which will be discussed later.

What is the work culture of these NGOs? Except for

SCF (UK) 'partner' NGOs, the other three NGOs have

service rules, policies on promotion, and transfer of

field workers. The small size and greater inter-personal

relations of the SCF (UK) partner NGOs seem to have

created less necessity for such rules and policies. The

large numbers of staff and large areas covered are the

major reasons for the presence of these formal rules

and policies in PROSHIKAand RDRS,while in the case

of MCCthis is mainly due to its internationalmissionary

nature.

All the NGOs studied have clear policies on casual

The NGOs studied

leave, medical leave and other benefits, however there

MCC Internationalfirstcame to Bangladesh to assist the are two issues that meritdiscussion. First,many of these

survivors of the great tidal bore disaster of 1970,

policies have been formulated in response to years of

centred at Noakhali, south-east of Dhaka. Now there demands from the field workers. Demands which in

are three main foci in the MCC programmes in some cases meant sacrifices, forced transferor redunBangladesh: agricultural and family development, dancy. Second, the mere existence of these policies is

employment creation and emergency assistance. MCC not enough for either NGOs or field workers. Most field

Bangladesh has 141 full-time staff. I worked in workers know little about these policies. Many field

Noakhali and found MCC leaders and field workers workers told me 'What can we do when our superiors

critical of microcredit, which they do not use.

do not follow the rules? We cannot go on strike or

PROSHIKAis one of the largest national NGOs in afford to go to courts.'

Of the NGOs studied, only MCC has effective rules

Bangladesh. Since its inception in 1976, PROSHIKA's

effort has been to engender a participatory process of and hours of work. MCC field workers do not have to

'development' and it claims to have succeeded in pio- work at weekends or after office hours. Forthe others,

neering an approach that puts human development at the hours of work specified on paper are meaningless.

the centre. PROSHIKAworks in 10 166 villages and Each field worker has a charterof duties and knows the

654 urban slums, with nearly 1.3 million men and performance indicators they must reach. It is these,

women from rural and urban poor households organ- ratherthan the contracted hours, which controls their

ized into 68 897 groups. This translates into a total use of time. In theory, a five-day week is worked in

programme reach of over 7.1 million individuals Bangladesh. All organizations are required to close on

(PROSHIKA1997). In Sakhipur, where I worked, I Friday, but they have the discretion with respect to

found microcredit displacing other activities.

closing, for example, from midday on Thursdayto midRDRS is one of the oldest NGOs in the country. day on Saturday.Forfield workers, however, it is much

Working in northernBangladesh, with around 200 000 easier to find clients at home on Fridays,so many work

households, RDRS employs about 1500 staff. on Fridays.

NGOs facilitating the empowerment of poor people

seems to have diminished during their expansion

(Ebdon 1995; Montgomery et al. 1996). I agree with

Hulme and Mosley (1996) that NGOs are no longer

vehicles for social mobilization to confront existing

socio-political structures.

Most Bangladeshi NGOs are heavily dependent on

foreign funds (Hashemi 1995). The volume of foreign

funds to NGOs in Bangladesh has been increasing over

the years and stood at just below 18% of all foreign

'aid' to the country in the financial year 1995-96.

Donors increased their funding from 464 NGO

projects in 1990-91 to 746 in 1996-97, a 143%

increase in value over the period (NGO AffairsBureau

1998). The disbursement of funds to NGOs is highly

skewed. The top 15 NGOs accounted for 84% of all

allocation to NGOs in 1991-92, and 70% in 1992-93

(Hashemi 1995). NGO dependence on donor grants

has kept the whole operation highly subsidized.

Donors give funds for certain activities and evaluate

the impact of that 'aid' on certain criteria (e.g. accessibility to the target population, improvement in

education including dropout rates, enrolment, girls'

enrolment, repayment of credit etc.). So, to ensure regular supplies of funds, NGOs have to ask their field

workers to maintain performance and to show performance to donors according to their criteria. This seems

natural as NGOs in Bangladesh are not membership

organizations and the NGO agenda in Bangladesh is

largely donor-driven.

This content downloaded from 119.148.3.126 on Fri, 6 Feb 2015 00:34:27 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

The views of the field workersof NGOs in Bangladeshon microcredit

Why do field workers work longer hours than they

are contracted to? The answer is to keep their jobs and,

if fortunate, to qualify for promotion. Staffevaluation is

a major factor influencing what field workers do and

how likely they are to retain their jobs. NGOs know

they can apply these criteria to their field workers, for

if any field worker fails to maintain the required standards, their contracts can be terminated and, due to high

unemployment, the NGOs have little difficulty in

recruiting new field workers.

Microcredit in Bangladesh

The rise of both state- and NGO-sponsored microcredit

programmes over the last three decades derives from

various factors: capital scarcity, the inability of the

formal system to reach the functionally landless

(uncollateralized) poor, and the limited ability of

the InformalFinancial Marketto meet the needs of the

majority of poor people striving to survive in the

off-farm sector (Bhatt and Tang 1998; Sharma and

Zeller 1997; Montgomery et al. 1996). However, my

research suggests three reasons.

1 International acceptance of the Grameen Bank

model of 'development'. The initial success of this

model has drawn international attention and many

donors have accepted it as a cure-all for the problem

of underdevelopment (Bhattand Tang 1998; Hulme

and Mosley 1998; Montgomery et al. 1996). Nayar

and Faisal (1999) found that MFIsshowed resilience

to the most devastating floods in Bangladesh in

1998. The replicability of the model has been questioned by many researchers like Reinke (1998).

2 A leading advantage of microcredit programmes is

that their 'performance' can easily be measured,

which enables the NGO to demonstrate achievements and satisfy its donors. Now that development

intervention is so much driven by 'performance indicators' (Mcnamara and Morse 1998; Gore 1998),

this can be a decisive factor in its adoption.

3 NGOs seek self reliance and independence from

donors. By working in microcredit, NGOs can use

interest paid by their clients to pay some of their staff

and other costs. Such charging of clients is one avenue for them to follow in orderto become self-reliant

(Edwards1999; Yaqub 1998; Mcnamara and Morse

1998; Rutherford 1998; Popham 1998; The Independent 1998a; Abels 1998; Rhyne and Otero

1992). Forexample, PKSF(RuralEmployment Foundation in English,a quasi-government organization)

lends to NGOs at an interestrateof 4%, while NGOs

usually lend to their clients at interest rates of

between 12 and 16% (PKSF1998). In the financial

year 1996-97, one SCF (UK) 'partner' NGO had a

total income of 384 000 Taka from interest on

microcredit and a total expenditure of 241 000

67

Taka2.After studying six nineteenth century microcredit organizations, Hollis and Sweetman (1998)

concluded thatdepositor-basedmicrocreditorganizations (MOs)tend to last longer and serve many more

borrowers than MOs financed by donations or government loans. The other option for increased autonomy is to start commercial ventures like BRAC's

(Bangladeshi Rural Advancement Committee)

marketing outlet, printing press and cold storage or

Ganoshasthya Kendra'sbrick field and pharmaceutical industries, which have also evoked comments

from the critics of NGOs (The Daily Inquilab 1996).

Although annual operationalcosts of BRAC'sbranchlevel units are still more than three times their

locally generated income (Montgomery etal. 1996),

White (1999) points out that BRACgenerates 31%

of its income from its business sources.

These opinions are drawn from the literature;but what

of the discourses of NGO field workers? When RDRS

started, it was the largest NGO in terms of number of

clients, but it was mainly a relief agency. After the

appearance of BRAC, Grameen Bank and ASA

(Assistance for Social Advancement) in the region in

the late 1980s, RDRS also began to provide credit

because it was losing clients to the big credit-giving

NGOs like BRAC and was under great pressure

from clients to provide credit. Nonetheless RDRS is

still inexperienced in operating credit programmes

compared to many large NGOs in Bangladesh.

PROSHIKAfield workers reported the same problem.

In contrast, MCC clients borrow from their group's

savings and NGO credit is of minor importance

compared to other NGOs studied.

What NGOs say and what NGOs do

The policy statements of these NGOs promote their

activities as diversified. However, to anyone visiting

the areas where the NGOs work, the homogeneity of

their activities becomes clearly visible. SCF (UK) is a

good example of an NGO which differs between

emphasis and disparity.

Since its arrivalin Bangladesh, SCF (UK)has worked

directly in 'development', and from 1996 onwards it has

handed over funds and some physical resources to

newly created'partner'NGOs. The firstgroupof 'partners'

is run by its former field workers (all women) in Shariatpur District. In my field work with these new, small

'partner' NGOs in Shariatpur,I found that the way the

SCF(UK)'partners'are now workingis directlyin contrast

to the strategy paper of SCF (UK) Bangladesh (1997):

Nearlyall developmentwork in Bangladeshis targeted

at the great mass of 'poor people' but actuallyneglects

the poorest and most marginalisedwithin this group.

Thus, for example, the famous Bangladesh credit

This content downloaded from 119.148.3.126 on Fri, 6 Feb 2015 00:34:27 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

The views of the field workersof NGOs in Bangladeshon microcredit

68

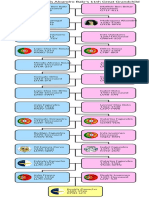

Table1 The NGOs'definitionsof theirtargetgroups

MCCBangladesh

PROSHIKA

RDRSBangladesh

SCF(UK)'Partners'

Men or women from

householdswho cannot

produceor buy food for

morethan 3 months.Own

less than 1 acre of cultivable

land. Not morethanone

memberfromthe

same family

Landlessand marginal

farmers(menor women).

Not morethanone

memberfromthe same

family

Householdshouldhave

less than 1.5 acresof land.

The membershouldbe from

the 18-45 age group.Not

morethanone memberfrom

the same family.A family

head, with not morethan

8 yearsof school education,

and a permanentresidentof

the village

Womenfromhouseholds

with less than 1.5 acresof

cultivableland,who are

permanentresidentsof

the NGO'sworkingarea.

Not morethanone member

fromthe same family.

Monthlyhouseholdincome

of less than 1500 Taka.

Not serviceholders

Source: NGO literatureand interviews

programmestypicallydo not benefitthe poorest strata

If the general NGO priority is to provide resources

and opportunities to those currentlyexcluded, it seems

a waste of time and money to begin work where these

same time, the povertyalleviationprogrammeswhich resources and opportunities are already available and

muchof the developmentcommunityin Bangladeshare sometimes duplicated. Ebdon (1995) found NGOs

engaged in treatspovertyas an almostpurelyeconomic competing for the same clients to facilitate rapidexpanphenomenon.Many of the most serious situationsin sion of their programmes. A similar situation occurred

Bangladeshare not the 'inevitable consequences of in all my study areas with the exception of the area

poverty'thatboth NGOsand policy makersseem to see where MCC was active. Such competitive behaviour

them as. Such situationsare associatedwith povertybut contradicts NGO claims to cooperation and coordinaare caused by social factors.They are not likely to be tion with the common interestof empowering the poor.

solved within the next fifty years by the slowly rolling Instead, it creates and perpetuates factions and conpoverty alleviation programmeswhich dominate the flicts at all levels (Ebdon 1995).

of society and although, they are targeted at women,

may tend to exploit or burden women further. At the

development scene in Bangladesh .. . Many of the

problemsof the most poor and marginalisedare both

economic and social in naturebut social problemsare

especiallyneglectedin much developmentpractice.We

will thereforefocus muchof our attentionon them

SCF(UK)Bangladesh1997, 3

The 'partners'of SCF(UK)in Shariatpur,however, work

only on a single activity - credit.

Only the MCC proved in practice in the field to have

a differentphilosophy and to spend littletime on credit.

On working with two other NGOs, I found that they

also had a heavy bias to credit. PROSHIKAusually has

two types of field workers - EDWs (economic development workers, working on credit) and DEWs (development education workers). Most field workers told me,

'If you want to get quick promotion, try to be an EDW,

and show success in credit'. Although RDRS documents (RDRSBangladesh 1996a 1996b) reporta range

of services, all the field workers I interviewed are preoccupied with credit and most complained that they

cannot give enough time or importance to other services. Generally, RDRSfield workers leave their homes

or hostels each morning to reach their clients to collect

or disburse microcredit.

Defining the target group

More than 50% of the rural population of Bangladesh

is poor3. NGOs claim that their target should be not

only those who are materially poor but also those who

are vulnerable, vulnerable to naturalhazards like flood,

river erosion and cyclones, and who have very few

ways to escape poverty. Here I want to explore the

'target groups' of the NGOs and to demonstrate that

NGO field workers would like broader targetgroups in

MCCand PROSHIKA,to include some of the less poor,

and RDRSand SCF (UK) 'partners'would like to reach

even poorer people than they do already.

Most NGOs in Bangladesh have specific target

groups (Table 1). Most field workers of MCC Bangladesh said that the definition should be extended to

richer farming or fishing households. Many argue that

both small and marginal farmers need help of the type

that MCCprovides to its clients, not just the poorer people in the target group.

PROSHIKA'starget group consists of landless and

marginal farmers;but most field workers would prefer

to include medium-scalefarmers(owning lessthan 3 acres

of land). They think these farmers deserve PROSHIKA

This content downloaded from 119.148.3.126 on Fri, 6 Feb 2015 00:34:27 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

The views of the field workersof NGOs in Bangladeshon microcredit

69

services to facilitate their 'development'. Such farmers jobs (e.g. Rahman 1999 on Grammen Bank). So, they

would, of course, be clients with a greater ability to prioritize microcredit at the expense of other activities.

In Bangladesh, all microcredit is designated for

repayand therefore easier for field workers to deal with.

Of the four NGOs, PROSHIKA

reaches most poor people, income generation; there is no consumption credit.

but this is not in line with the preferencesof their field Many borrowers have to devote some of the credit to

workers.

consumption (food, marriage, house repair), which

Field workersof RDRSand SCF(UK)identifiedgroups makes it difficult for them to generate enough income

in poverty currently excluded from their target groups. to repay loans. NGO credit for the poor in Bangladesh

For example, RDRS field workers pointed out that a can be exploitative. A senior manager at MCCtold me

household with five members owning 3 acres of land that he thinks this is the case for most NGOs (Shafiqul

has less land per capita than a household of three mem- Islam, personal communication). This is also the

bers. Similarly, the requirement for a client to become opinion of most of the MCC field workers I intera permanent resident in the NGO area may exclude viewed. However, it must be that MCC differs from

many. Poor families cannot survive in many localities the other NGOs I worked with, as its priorities and

during lean periods (when there is scarcity of jobs), and working methods are different.Iascribe these differences

many male members of such households migrate sea- to its missionary nature.

PROSHIKAis a good example of an NGO which has

sonally. Since women arethe NGO membersand depend

on their husband's income to make most of the repay- changed its priorityfrom conscientization to credit over

ments on the loan, the criterion of residence excludes the last 25 years. Many older field workers reportedthe

a major group in poverty. RDRSchooses the age group changes that PROSHIKAhas gone through:

that can work hard and repay their loan in time, but

When I joined PROSHIKA

10 years ago, my work was

ironically the over 50 age group, which is the most

to go to the farmersand to organisethem in groups,

vulnerable in Bangladesh, is excluded from the 'target'

motivatingthem through music and lectures. So, I

group of RDRS.Additionally, the educational qualificalearned how to sing and use the harmoniumand the

tion of eight years of formal education excludes many

of the poor. However, most field workers told me that

'Dhole' (the drum).People came to listento our music

this qualification should be raised to the Secondary

and lecture. Some days, I found some people crying

after listeningto our music which was describinghow

School Certificate level, which is equivalent to ten

an affluent farmer became landless through the

years of formal education, since this helps with record

exploitationof moneylenders.My life was easy. There

keeping. This would further exclude the poor. Most

SCF (UK) 'partner' field workers interviewed argued

was no credit programmebut little skill or literacy

that their target group is inappropriate to reach the

training.... Now I ride hundredsof miles, I have no

leisure. I have to show good repaymentrate of my

poorest people because of the problems of landholding

disbursedcredit to save my job. To get money back

and permanent residence, which have already been

sometimesI abuse my members.Now my life is full of

alluded to. The rules do have some positive features:for

tension. Many nightsI cannot sleep due to the anxiety

instance, Montgomery et al. (1996) argued that a baron

aboutwhat I shall do if I lose the job.

dual membership from the same family ensures more

QamrulIslam,TrainingCoordinator,Sakhipur,

peer pressure and partly reduces the risks.

February1999

Why do so many field workers want clients who are

less poor? It is clear that the targets already exclude the

poorest people, those who do not own land and/or are In general, it appears that PROSHIKAgroups are

less well educated, are migrant and people over 45. working well. Some groups are very committed to

Undoubtedly this is related to the evaluation of the per- attending the training programmes for microcredit. But

formance of the field workers, which is mainly meas- many field workers also told me of ineffective groups

ured in terms of their performance in microcredit and, and groups which have split. There are four reasons for

in the case of MCC, technical assistance. Field workers this:

would prefer not-so-poor, more educated clients

(Khandker etal. 1998; Tonah 1994), which would

1 Most field workers and even many group members

mis-target and deepen credit disbursement (Matin

thought that PROSHIKAgroups (normally 20-25

1998; Sinha and Matin 1998). This is against the stated

people) were too large for credit though not for conscientization or mobilization activities. As trainingof

objectives of all of the NGOs studied.

members in group work is almost non-existent, it is

difficult to keep the groups from being controlled by

Credit: problem of repayment and pressure on the

one or two people (e.g. Rahman 1999 on Grammen

field workers

Bank). Some members discourage others from

Field workers are under tremendous pressure to

repaying loans or depositing monthly savings, statproduce high credit repayment rates to secure their

ing that PROSHIKAhas no legal authority to take

This content downloaded from 119.148.3.126 on Fri, 6 Feb 2015 00:34:27 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

70

The views of the field workersof NGOs in Bangladeshon microcredit

action if they default or disobey. The high costs of

court action discourage the NGOs from taking legal

redress. But there are exceptions to this, as in one

case seven NGO clients were sent to jail for defaulting on loans (NFB 1999b). Unlike banks, NGOs

such as PROSHIKAhave no collateral against loans

and depend on their social capital.

2 Repayment is a major problem with the poorer

groups. Often they cannot repay loans regularly,and

when they utilize their loan money for consumption

(e.g. food or house repairs)they may be unable to

repay at all. In theory, members are required to utilize the loans for the purpose for which they have

been granted and field workers monitor utilization,

but poorer borrowers often disobey (e.g. Sinha and

Matin 1998; Rahman 1999 on Grammen Bank).

3 Usually clients must save 5-10 Taka a month, to be

deposited in the group's bank account. But often

group members collude and start credit businesses

instead, due to the fact that moneylending is profitable in ruralBangladesh, where interest ratesof 10%

per month are commonplace. Diversion of the group

savings to moneylending deprives other members of

the profit, which creates conflict in the groups.

Groups often split because of the conflicts moneylending creates.

4 Groups also split or become inoperative when group

members migrate (often to south-east Asia or the

Middle East to work). Migrants do not usually tell

other members or the field workers that they are

planning to leave the country since that will disqualify them from becoming members. When a group

member leaves the country an immediate problem

arises: who will repay the loan? Sometimes the

absent member's close relations repay the loan from

the person's remittances, but often nobody takes

responsibility.

Credit is now the main activity of RDRS,but their field

staff identified several problems with credit repayment:

1 Most clients 'do not utilize their credit properly',

although credit is given only for specific projects.

Some simply buy food with the credit and do not

invest money in the proposed project. Basically,

there is a lack of supervision of credit utilization. In

addition, many clients borrow money from businessmen and professional moneylenders and repay

these debts with the RDRS loans. This view was

shared by some PROSHIKAfield workers who

argued that clients should not be given credit on

more than three occasions, if self reliance is the ultimate goal. This was because most members use half

the credit for the approved project and the other half

in business, which gives a larger and quicker profit.

2 Many field workers complained that RDRS'management of loan repayment is lax, while other organizations such as Grameen Bank, BRAC, and ASA are

much more strict in loan recovery. Chowdhury

(1998) provides information on the strict policy of

loan recovery by ASA. Several field workers complained that many clients have not re-oriented their

relationship with RDRS from relief to credit, but

simply assume that credit is a non-repayable relief.

3 It has already been noted that there is competition

among NGOs in rural Bangladesh in disbursement

and repayment of credit. In some cases one RDRS

client simultaneously becomes a client of another

NGO. So, one member of a household takes a loan

from one NGO and repays the loan taken from

another NGO by another member of the same

household. In general, the policy of most NGOs is

that only one member from one household can be

an NGO member. But this does not work in all

cases. In some cases field workers force their client

to resign their membership when someone from the

same household becomes a member of another

NGO. However, field workers cannot expel a client

if they argue that the loan is inadequate, or if they

repay loan(s) and attend other activities of the NGO.

4 RSDS workers pointed out that it is almost impossible to pursue defaulters through the courts for the

same reasons outlined by the PROSHIKAworkers.

5 Many people (mostly men) migrate to other districts

in search of jobs during the planting and harvesting

seasons. As they are away from home for three to five

months, they do not repay loans during this time;

and after they return,they often default on the pretext of low income.

To keep a good repayment record SCF(UK)'partners'

exert group pressure through members of a group on a

defaulter as their main tool, although field workers also

go to local leaders to exert pressure on clients to repay

loans. Field workers from influential families in villages

are in an advantageous position because clients are

under obligation to abide by pressure exerted by local

leaders, and, therefore, their loan repayment records

are usually good. Some clients still default, arguing

'What can you do if I do not repay (my) loans?' Some

clients reported that field workers sometimes verbally

abuse clients for not making regularrepayments. As the

NGOs do not train clients in record keeping, problems

follow. In particular,illiterateclients who do not understand arithmetic or accounts often have misunderstandings with field workers. I found bitterness

amongst both clients and field workers. Although

Kabeer (1998) has suggested that there is some degree

of flexibility in loan repayments, most of the field

workers I interviewed disagreed with this because it

makes their work more difficult.

Field workers are not in theory supposed to be debt

collectors and 'development' workers simultaneously.

Usually the cashier or secretary of the group should

collect the money from the clients. In most cases this

This content downloaded from 119.148.3.126 on Fri, 6 Feb 2015 00:34:27 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

The views of the field workersof NGOs in Bangladeshon microcredit

does not happen due to the poor mobilization of the

groups and the problems mentioned above (Johnson

and Rogaly 1997).

Most field workers I interviewed, however, thought

that technical advice on agriculture, education and

health education should be given equal importance to

that of credit, and feared that, with increasing emphasis

on credit, other aspects of 'development' are being left

aside. Interestingly,Sharma and Zeller (1997) reported

the same concerns fuelled by the demands to keep up

a good repayment rate, and the World Bank noted

similar issues in the context of poverty alleviation

(Micronews 1999).

In some cases field workers feel they are under great

pressure to retrieve the money borrowed, and this has

led to anti-social behaviour amongst some field workers. As one PROSHIKAfield worker said:

71

relationship can easily be explained in terms of the

greater preference of the poor for consumption loans,

their greater vulnerability to asset sales forced by

adverse income shocks and their limited range of

investment opportunities. Lenders, they argue, can

either focus their lending on the poorest and accept a

relatively low total impact on household income, or

alternatively focus on the not-so-poor and achieve

higher impact (Hulme and Mosley 1996; compare

Khandkeret al. 1998; Evans et al. 1999). My research

findings are in line with their observations. In

Bangladesh, the impact of microcredit on poverty has

been limited, despite its fame. Hashemi (1998) argues

that although microcredit in Bangladesh (through

Grameen Bank, BRAC, PROSHIKA,ASA and other

governmental and non-governmental agencies) has

succeeded in reaching a quarter of all poor rural

households, poverty still persists. One major reason for

When I lend money, I always keep pressureon my this may be the limits to microcredit in effectively

clients that they have to repay it by whatevermeans. I targeting all of the poor; more specifically in leaving

tell them that if you die withoutrepayingmy loan I will out large sections of the 'hard core' poor - the

kick on your grave four times because you have not distressed (Khandker et al. 1998; Hashemi 1998;

Kabeer 1998; The Independent 1998c; Johnson and

repaidthe money.

AtiqulAlam,EDW,Sakhipur,February1999 Rogaly 1997; Evans et al. 1999). For Hulme and

Mosley (1996), the main problems worldwide in the

The emphasis placed on credit repayment can be practice of microcredit are overemphasis on credit

illustrated by the following example. If the repayment delivery, social exclusion in the delivery system and a

rate of a RSDS field worker goes below 75%, the professionalization of management under which

worker's food allowance is stopped for the next month. incentive structures for staff, such as bonus payments

Although RDRS field workers have to provide many and promotion prospects, favour concentration on

services (e.g. providing advice on education groups other than the poorest. All these features are

programmes, plantation work, fisheries and livestock highly developed in Bangladesh. Khandker and

projects) to their clients most of their time is spent on Chowdhury (1996) hold the relatively positive view

credit, since their job performance is mainly measured that, for the targeted credit programmes in Bangladesh,

in terms of credit repayment. Some field workers I it will take, on average, about five years for poor

interviewed, though very hard working, were poor at programme participantsto rise above the poverty line

record keeping. This caused furthermisunderstandings and eight years to achieve economic graduation (i.e. to

with their clients.

stop taking loans from a targeted credit programme).

On average, the women who work for SCF (UK) Montgomery et al. (1996), however, found little

'partner' NGOs walk 6-8 km a day in the morning to evidence that BRAC's clientele are altering their

collect money and disburse loans and after lunch structural position within the rural economy. Their

they work in their offices finalizing their daily accounts. conclusion, that credit may be insufficient and

Their working day often lasts ten hours. The NGOs inappropriate for alleviating extreme poverty

have to keep two months' salary for its staff in the (Montgomery et al. 1996), 1 feel is borne out by this

bank to ensure staff obtain regular salary disburse- research. Ebdon (1995) found in the case of the

ments. The long working days and lengthy arrears in Grameen Bank that most women would simply be

salary payment create extra burdens on pressurized given the money by their household to cover the

NGO field workers.

weekly repayments and hence their economic status

was not improved (Ebdon 1995; The Daily Star 1999).

Karimand Osada (1998) found that of those members

Does microcreditbenefitthe poor?

who dropped out of Grameen Bankgroups within their

In general, microcredit benefits the less poor more than seventh year of membership, 88% did not move out of

it does the poorest people, even if it reaches them. poverty.

Hulme and Mosely (1996) found that the impact of

Hulme and Mosley (1996) challenge the claim that

microlending on the recipient household's income every loan to women is a step forward in their empowtends to increase, though at decreasing rates, as the erment (Rahman 1999 on Grameen Bank)and suggest

recipient's income and asset position improve. This that NGOs need to pay much greater attention to their

This content downloaded from 119.148.3.126 on Fri, 6 Feb 2015 00:34:27 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

72

The views of the field workersof NGOs in Bangladeshon microcredit

capacity to assist target groups within the female

population (particularly the assetless, widowed and

divorced) ratherthan treating women as a homogeneous group (Hulme and Mosley 1996). My field work

with the case study NGOs supports this argument.

Among the SCF (UK) 'partners', the very small loans

give clients very little economic lift. With this nominal

economic progress, other aspects of 'development' of

their lives have remained largely ignored. One client

reported to me that her husband had lost most of his

money this year because of the low price of his product

- chilli pepper - and to repay her debts, her eldest son

stopped attending school to catch fish. This is directly

comparable to Wydick's (1999) observation from Guatemala that the relationship between access to credit

and investment in child schooling is not unequivocally

positive.

Turning to the potential for the improvement of

microcredit, the field workers of two other NGOs

- RDRS and PROSHIKA- said that normally about

30% of clients are successful in their microenterprises,

and these are mainly those involved in petty trading,

cottage industries, and fishery, livestock or poultry

projects (Rutherford1998; Khandkeret al. 1998). At the

same time they pointed out that all microenterprises

have limited growth potential, being constrained

both by their inherent nature and by contextual conditions such as market demand. They argue that few

clients can improve their economic position through

agriculture, mainly because they have so little land.

Of the rest, the majorityof clients show some improvement, but remain dependent on NGO credit to retain

this position. As one PROSHIKAfield worker put it,

'clients have to run very fast to stay in the same place'.

Most field workers agreed that the poor marketing

system hampers the sustained growth of microenterprises. At the same time, however, most thought that

if NGOs became involved in marketingthere would be a

strong possibility of exploitation of clients by the NGOs.

Field workers emphasized the importance of skills

training and of adult literacy programmes,as these help

the clients to become efficient sellers of their products.

This supports the recommendations of Khandkerand

Chowdhury (1996), Johnson and Rogaly (1997) and

Evans et al. (1999). Most field workers interviewed

advised that before considering the sustainability of a

microenterprise it is important to make provision for

the sustainability of the groups. They suggested more

emphasis on training in literacy and book-keeping,

which would enable the groupsto become self-operating,

as well as helping the individual clients. MCC differs

from the other NGOs in that most of the microenterprises they support are agro-based. Most MCC

field workers recognized that these agro-based enterprises cannot be sustainable, because clients have very

limited land and agriculture is always vulnerable to

naturalenvironmental fluctuations.

Microcredit has clearly made the relationship

between the NGO and its clients primarilyeconomic

(Hulme and Mosley 1996). However, this is not always

the case. Schuler and Hashemi (1995) and Schuler

et al. (1997) found that women's access to credit augments use of contraception and that there may be a

positive association between women's contributions to

family support and reduced domestic violence. They

furtherargued that much more extensive interventions

will be needed to significantly undermine men's violence against women (Schuler et al. 1996). They also

found that wife beating was never discussed in NGO

meetings, the discussions mainly being about credit,

and conclude that NGOs (the Grameen Bank and

BRAC)are interested in providing credit not in changing patriarchyin rural Bangladesh.

Conclusion

It is clear that the vast majority of the very poorest

people are not reached by the NGOs investigated

because of their definitions of their target population

and because of the preferences of field workers. This

situation has been made worse by the overemphasis on

microcredit, which has compelled field workers to

approach the slightly less poor to achieve good

repayment rates.

The misuse of loans is a major problem. The initial

success of the microcredit programmes may be attributed mainly to close supervision by the field workers.

The MCC system, where the field workers go with the

members to buy the cattle from the market, seems a

good model of close initial supervision.

For field workers there is pressure both to disburse

loans and to keep a good repayment record. If 'development' is to be participatory then they have to let

the clients decide whether they will borrow and how

much. The present evaluation system of the field

workers, which is mainly based on their credit performance, has put the 'development' effortof the NGOs into

question.

NGOs are losing clients due to competition between

them to lend. Coordination among NGOs to formulate

a common policy is urgently needed. This is particularly necessary to combat the present problems of clients switching NGOs to obtain credit or having clients

of different NGOs in the same household.

Microcredit is necessary for the poor but is no panacea (Hulme and Mosely 1996). NGOs should provide

microcredit along with other services, particularlyon

the basis of prioritiesidentified by field workers and clients. The other services are not only necessary for the

poor for other reasons: some are necessary for sustaining the groups and microenterprises. For example,

non-formal education, skills training and adult literacy

help the members to keep good records, which will

assist in making the microenterprise sustainable. The

This content downloaded from 119.148.3.126 on Fri, 6 Feb 2015 00:34:27 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

The views of the field workersof NGOs in Bangladeshon microcredit

great emphasis on microcredit also means that groups

break up both when they do not get microcredit and

when they misuse it. Many people join the groups only

to get credit. This is not mobilization of the poor.

Groups of the poor are the cornerstones for their 'development'. Ifgroups are formed for credit the whole effort

becomes banking for the poor. This does have benefits

but, as Hulme and Mosley (1996) argue, it does not

replace other state and NGO initiatives.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank Dr Janet Townsend at

Durham University for her comments on the initial

draft of the paper. The usual disclaimers apply.

Notes

1 These NGOs will be discussed in this order, from international to local, throughoutthe paper.

2 The US dollar was equal to 57 Taka in October 2001.

3 The povertyline is defined as monthlyper capita expenditure

which permits a daily intake of 2122 calories (World Bank

1996).

References

73

Hashemi S M 1998 Those left behind: a note on targetingthe

hard-core poor in Wood G and Sharif I A eds Who needs

credit - poverty and finance in Bangladesh Zed Books,

London

Hollis A and Sweetman A 1998 Microcredit:what can we

learn from the past? WorldDevelopment 26 1875-91

Hulme D and Mosley P eds 1996 Finance againstpovertyvol 1

Routledge,London

Hulme D and Mosley P 1998 Microenterprisefinance: is there

a conflict between growth and poverty alleviation? World

Development 26 783-90

Islam S personalcommunication

Johnson S and Rogaly B 1997 Microfinanceand poverty reduction Oxfam and ActionAid,Oxford

Kabeer N 1998 Money can't buy me love? Re-evaluatinggender,

credit and empowerment in ruralBangladeshIDS Discussion

Paper363 May

KarimM R and Osada M 1998 Droppingout: an emergingfactor

in the success of microcredit-based

povertyalleviationprograms

The Developing EconomiesXXXVI257-88

KhandkerS R 1999 Micro-creditprogrammeevaluation:a critical

review IDS Bulletin29 11-20

Khandker S R and Chowdhury O H 1996 Targeted credit

programmes and rural poverty in Bangladesh World Bank

Discussion PaperNo. 336 The World Bank,WashingtonDC

KhandkerS R, Samad H A and Khan Z R 1998 Income and

employment effects of micro-creditprogrammes:village-level

evidence from BangladeshTheJournalof DevelopmentStudies

35 96-124

Lewis D J 1993 NGO-government interactionin Bangladeshin

FarringtonJ and Lewis D J eds Non-governmental organisations and the state in Asia rethinkingroles in sustainable

agriculturaldevelopment Routledge,London

Matin 1 1998 Mis-targetingby the Grameen Bank: a possible

explanation IDS Bulletin29 51-8

Mcnamara N and Morse S 1998 Donors and sustainabilityin

the provision of financial services in Nigeria IDS Bulletin 29

91-101

Micronews 1999 Microcredit alone won't solve poverty.

Micronews (Electronicnewsletter on Microfinanceand Poverty Alleviation) 3 April www.lists.w3internetc.o/pipermail/

enter-1/1999-April/000791.html (Originally published in

News from Bangladesh, January 1999, no longer on this

their web site). Accessed 27 January2002.

MontgomeryR et al. 1996 Creditforthe poor in Bangladesh- the

BRACRural Development Programmeand the Government

Thana Resource Development and EmploymentProgramme

in Hulme D and Mosley P eds Finance against poverty vol 2

Routledge,London

Mutua K, Nataradol P, Otero M and Chung B 1996 The view

from the field: perspectives from managers of microfinance

institutionsjournal of InternationalDevelopment 8 179-93

Nayar N and FaisalM E H 1999 Microfinancesurvives Bangla-

Abels H 1998 'Quality standardsfor micro-financeinstitutions'

paper presented at the Third INAFIAsian Regional Seminar

on Scaling up and Sustained Growth in Micro-Finance28

February-i March Dhaka

ADAB 1998 Directoryof PVDOs/NGDOsin Bangladesh(ready

reference)ADAB, Dhaka

Ahmad M M and Townsend J G 1998 Changing fortunes in

anti-poverty programmes in Bangladesh Journal of International Development 10 427-38

Bhatt N and Tang S 1998 The problem of transactioncosts in

group-basedmicrolending:an institutionalperspective World

Development 26 623-37

Chowdhury S H 1998 'Approaches,methods and strategiesfor

rapid growth' paper presented at the Third INAFI Asian

Regional Seminar on Scaling up and Sustained Growth in

Micro-Finance28 February-1March Dhaka

Ebdon R 1995 NGO expansion and the fight to reach the poor:

gender implications of NGO scaling-up in Bangladesh IDS

Bulletin26 49-55

Edwards M 1999 NGO performance- what breeds success?

New evidence from South Asia WorldDevelopment27 36174

EvansT G, Adams A M, Mohammed R and Norris A H 1999

Demystifying nonparticipationin microcredit:a populationbased analysis WorldDevelopment 27 419-30

Gore C 1998 Globalization, distribution and development:

which way now? Draftmimeo

Hashemi S M 1995 NGO accountabilityin Bangladesh:benefidesh floods Economic and Political Weekly 3 April.

ciaries, donors and state in EdwardsM and Hulme D eds NFB 1999b Non-repayment of NGO loan, 7 sent to jail 5 February

Reference is no longer

Non-governmentalorganisations- performanceand accountwww.bangladesh-web.com/news.

available in the News from Bangladesh web archive.

abilitybeyond the magic bullet EarthscanPublications,London

This content downloaded from 119.148.3.126 on Fri, 6 Feb 2015 00:34:27 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

74

The views of the field workers of NGOs in Bangladesh on microcredit

NGO Affairs Bureau 1998 Flow of foreign grant fund through

NGO AffairsBureau at a glance NGO AffairsBureau PM's

Office/GOB, Dhaka

PKSF1998 PKSF- a guideline PKSF,Dhaka

Popham P 1998 Financial consultant makes money work for

Pakistanislum-dwellersThe Independent10 October

PROSHIKA

an introductionPROSHIKA,

1997 PROSHIKA

Dhaka

RahmanA 1999 Micro-creditinitiativesfor equitableand sustainable development:who pays?WorldDevelopment27 67-82

RangpurDinajpurRuralService (RDRS)Bangladesh1996a RDRS

Bangladesh 1996 LWSBangladeshRDRSBangladesh,Dhaka

RDRS Bangladesh 1996b Development Programme Policy

1996-2000 RDRSBangladesh,Dhaka

RDRSBangladesh1997 RDRSRDRSBangladesh,Dhaka

ReinkeJ 1998 Does solidaritypay?The case of the small enterprise foundation, South Africa Development and Change 29

553-76

RutherfordS 1998 The savings of the poor: improvingfinancial

services in Bangladeshjournal of InternationalDevelopment

10 1-15

RhyneEand Otero M 1992 Financialservicesfor microenterprises:

principlesand institutionsWorldDevelopment20 1561-71

SCF (UK) Bangladesh 1997 Bangladesh country strategypaper

(interim)SCF(UK),Dhaka

Schuler S R and Hashemi S M 1995 Family planning outreach

and credit programmesin rural Bangladesh Human Organization 54 455-61

Schuler S R, Hasmeni S M, Riley A P and AkhterS 1996 Credit

programmes,patriarchyand men's violence against women

in BangladeshSocial Science and Medicine 43 1729-42

Schuler S R, Hasmeni S M and Riley A P 1997 The influence

of women's changing roles and status in Bangladesh'sfertility

transition:evidence from a study of credit programmesand

contraceptiveuse WorldDevelopment 25 563-75

Schuler S R, Hasmeni S M and Badal S H 1998 Men's violence

against women in rural Bangladesh:underminedor exacerbated by microcreditprogrammes?Development in Practice

8 148-57

Sharma M and Zeller M 1997 Repayment performance of

group-basedcredit programmesin Bangladesh:an empirical

analysis WorldDevelopment 25 1731-42

Sinha S and Matin I 1998 Informal credit transactions of

micro-creditborrowers in rural Bangladesh IDS Bulletin 29

66-80

The Daily Inquilab 1996 NGOs are misusing tax advantage

Dhaka 3 May 5

The Daily Star 1999 Move only makingthem credit dependent

micro-finance seen failing to alter poor's economic status

30 Augustwww.dailystarnews.com/1

99908/30/n9083001 .htm

Accessed 27 January2002

The Independent 1998a Stresson micro-creditto fight poverty

Dhaka 12 July www.independent-bangladesh.comReference

is no longer available in the The Independent (Bangladesh)

web archive.

The Independent 1998b Micro-credit only won't alleviate

poverty Kibria 9 July www.independent-bangladesh.com

Reference is no longer available in the The Independent

(Bangladesh)web archive.

TheIndependent1998c Hardcorepoor have littleaccess to microcredits Dhaka 7 Novemberwww.independent-bangladesh.com

Reference is no longer available in the The Independent

(Bangladesh)web archive.

Tonah S 1994 Agriculturalextension services and smallholder

farmers'indebtednessin northeasternGhana journal of Asian

and AfricanStudiesXXIX.

White S 1999 NGOs, civil society, and the state in Bangladesh:

the politics of representing the poor Development and

Change 30 307-26

World Bank 1996 Bangladesh - Poverty Alleviation Microfinance Project Private Sector Development and Finance

Division/World Bank,WashingtonDC

Wydick B 1999 The effect of microenterpriselending on child

schooling in GuatemalaEconomic Development and Cultural

Change 47 853-69

Yaqub S 1998 Financial sector liberalisation:should the poor

applaud?IDS Bulletin29 102-11

This content downloaded from 119.148.3.126 on Fri, 6 Feb 2015 00:34:27 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5822)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1093)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (852)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (898)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (540)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (349)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (822)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (403)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- English Grammar Exercises With Answers For C2 - Part 2Document385 pagesEnglish Grammar Exercises With Answers For C2 - Part 2Rocio Licea100% (22)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Economic and Political WeeklyDocument4 pagesEconomic and Political WeeklyAsh ShakurNo ratings yet

- College of Business, Tennessee State UniversityDocument12 pagesCollege of Business, Tennessee State UniversityAsh ShakurNo ratings yet

- Chapter 2Document7 pagesChapter 2asdf789456123No ratings yet

- M.E. Sharpe, Inc.: M.E. Sharpe, Inc. Is Collaborating With JSTOR To Digitize, Preserve and Extend Access To ChallengeDocument10 pagesM.E. Sharpe, Inc.: M.E. Sharpe, Inc. Is Collaborating With JSTOR To Digitize, Preserve and Extend Access To ChallengeAsh ShakurNo ratings yet

- Bangladesh Institute of Development StudiesDocument14 pagesBangladesh Institute of Development StudiesAsh ShakurNo ratings yet

- Wipo Inn Abj 99 20Document6 pagesWipo Inn Abj 99 20Ash ShakurNo ratings yet

- Economic and Political WeeklyDocument4 pagesEconomic and Political WeeklyAsh ShakurNo ratings yet

- Carfree DevDocument168 pagesCarfree DevMuhammad Abdul Mubdi BindarNo ratings yet

- Art. Methodological Issues in Cross Cultural Marketing Research. A State of The Art Review PDFDocument45 pagesArt. Methodological Issues in Cross Cultural Marketing Research. A State of The Art Review PDFM.C MejiaNo ratings yet

- British Yearbook of International Law 1977 Crawford 93 182Document90 pagesBritish Yearbook of International Law 1977 Crawford 93 182irony91No ratings yet

- Business Law: Certificate in Accounting and Finance Stage ExaminationDocument3 pagesBusiness Law: Certificate in Accounting and Finance Stage ExaminationKashan KhanNo ratings yet

- Internet Marketing Filetype:pdfDocument11 pagesInternet Marketing Filetype:pdfnobpasit soisayampooNo ratings yet

- 2 Jurnal Jenis RacunDocument17 pages2 Jurnal Jenis RacunRifky NovanNo ratings yet

- Architectural Heritage Course Outline. 2021. by Biniam SHDocument2 pagesArchitectural Heritage Course Outline. 2021. by Biniam SHYe Geter Lig NegnNo ratings yet

- SHEDA MiriDocument2 pagesSHEDA MiriQushairy HaronNo ratings yet

- Roger Waters: George Roger Waters (Born 6 September 1943) Is An EnglishDocument24 pagesRoger Waters: George Roger Waters (Born 6 September 1943) Is An Englishaugtibcalclanero@yahoo.comNo ratings yet

- Reviewer in RPHDocument6 pagesReviewer in RPHmwuah tskNo ratings yet

- Class Notes On Agrobiodiversity Conservation and Climate Change 022Document156 pagesClass Notes On Agrobiodiversity Conservation and Climate Change 022Kabir Singh100% (1)

- Your Morrisons ReceiptDocument2 pagesYour Morrisons ReceiptRegina Vivian BarliNo ratings yet

- Financial Economics QuestionsDocument41 pagesFinancial Economics Questionsshivanithapar13No ratings yet

- 3D Sex and Zen Extreme Ecstasy 2011Document77 pages3D Sex and Zen Extreme Ecstasy 2011kalyscoNo ratings yet

- ImteDocument8 pagesImteShahid Hussain100% (1)

- Un Mundo Donde Quepan Muchos Mundos A Po PDFDocument42 pagesUn Mundo Donde Quepan Muchos Mundos A Po PDFJorge Acosta Jr.No ratings yet

- Globalization L7Document42 pagesGlobalization L7Cherrie Chu SiuwanNo ratings yet

- Axis Bank - WikipediaDocument68 pagesAxis Bank - Wikipediahnair_3No ratings yet

- 1 Aloandro Ben Bakr - BeatrizDocument1 page1 Aloandro Ben Bakr - BeatrizDavid DayNo ratings yet

- Copyright Law1Document2 pagesCopyright Law1Indra KumarNo ratings yet

- R.A. 7659 PDFDocument13 pagesR.A. 7659 PDFMarion Yves MosonesNo ratings yet

- SHS MIL Q1 W3 Responsible Use of Media and InformationDocument6 pagesSHS MIL Q1 W3 Responsible Use of Media and InformationChristina Paule Gordolan100% (1)

- Bilingualism and MultilingualismDocument18 pagesBilingualism and MultilingualismKaren Perez100% (1)

- Ictk MCQ PDFDocument24 pagesIctk MCQ PDFExtra Account100% (1)

- Module 2Document15 pagesModule 2Almie Joy Cañeda SasiNo ratings yet

- Debebe SeifuDocument170 pagesDebebe SeifuObsaa JirraNo ratings yet

- Finding Our Way Again - Part 1Document10 pagesFinding Our Way Again - Part 1dscharfNo ratings yet

- EDUP3073i Culture and Learning Notes Topic 3Document2 pagesEDUP3073i Culture and Learning Notes Topic 3Gabriel GohNo ratings yet

- Voluntarism - IEPDocument1 pageVoluntarism - IEPLeandro BertoncelloNo ratings yet