Professional Documents

Culture Documents

PPI Paper 2013 PDF

PPI Paper 2013 PDF

Uploaded by

Rara BantilanOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

PPI Paper 2013 PDF

PPI Paper 2013 PDF

Uploaded by

Rara BantilanCopyright:

Available Formats

ORIGINAL CONTRIBUTIONS

Incidence of Campylobacter and Salmonella Infections

Following First Prescription for PPI: A Cohort Study

Using Routine Data

Sinead Brophy, PhD1, Kerina H. Jones, PhD2, Muhammad A. Rahman, PhD3, Shang-Ming Zhou, PhD4, Ann John, MD5,

Mark D. Atkinson, PhD6, Nick Francis, PhD7, Ronan A. Lyons, MD8 and Frank Dunstan, PhD9

OBJECTIVES:

To examine the incidence of Campylobacter and Salmonella infection in patients prescribed proton

pump inhibitors (PPIs) compared with controls.

METHODS:

Retrospective cohort study using anonymous general practitioner (GP) data. Anonymised individuallevel records from the Secure Anonymised Information Linkage (SAIL) system between 1990 and

2010 in Wales were selected. Data were available from 1,913,925 individuals including 358,938

prescribed a PPI. The main outcome measures examined included incidence of Campylobacter or

Salmonella infection following a prescription for PPI.

RESULTS:

The rate of Campylobacter and Salmonella infections was already at 3.16.9 times that of non-PPI

patients even before PPI prescription. The PPI group had an increased hazard rate of infection

(after prescription for PPI) of 1.46 for Campylobacter and 1.2 for Salmonella, compared with

baseline. However, the non-PPI patients also had an increased hazard ratio with time. In fact,

the ratio of events in the PPI group compared with the non-PPI group using the prior event rate ratio

was 1.17 (95% CI 0.741.61) for Campylobacter and 1.00 (0.51.5) for Salmonella.

CONCLUSIONS: People who go on to be prescribed PPIs have a greater underlying risk of gastrointestinal (GI)

infection beforehand and they have a higher prevalence of risk factors before PPI prescription.

The rate of diagnosis of infection is increasing with time regardless of PPI use, and there is no

evidence that PPI is associated with an increase in diagnosed GI infection. It is likely that factors

associated with the demographic profile of the patient are the main contributors to increased rate of

GI infection for patients prescribed PPIs.

Am J Gastroenterol advance online publication, 16 April 2013; doi:10.1038/ajg.2013.30

INTRODUCTION

A major role of gastric acid is to protect against bacterial infection (1).

Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) and histamine receptor antagonists (H2RAs) are among a group of medications used to treat gastric acid-related disorders by reducing gastric acid secretion. PPIs

are considered to be more potent and effective acid suppressers

than H2Ras (2), and as such they are prescribed for conditions

such as gastric or duodenal ulcers, and gastro-oesophogeal reflux

disease, in accordance with the National Institute for Health and

Clinical Excellence guidelines (3,4). H2RAs are available over the

counter in low dosage in many countries, including the United

Kingdom (2).

It follows that PPIs, which act by reducing acid secretion, could

increase the risk of gastrointestinal (GI) infections by raising the

pH environment of the stomach and making it more prone to colonisation by various pathogenic bacteria. Previous case control studies have examined the association between acid suppression and

various GI infections, and they have found an increased risk of GI

infection in patients prescribed PPIs (1,5). For example, PPIs have

been associated with Clostridium difficile (1,59) and the US-FDA

issued a safety announcement on PPI (10). In addition, there have

been conflicting reports for pneumonia (1113) and other infections such as Salmonella and Campylobacter (14). However, the

majority of studies exclude cases where a pre-existing GI infection

Swansea University, Swansea, UK; 2Swansea University, Swansea, UK; 3Swansea University, Swansea, UK; 4Department of StatisticsSwansea University,

Swansea, UK; 5Public Health Wales, Swansea, UK; 6Swansea University, Swansea, UK; 7Cardiff University, Wales, UK; 8Department of Public Health Medicine,

Swansea University, Swansea, UK; 9Department of Medical Statistics, Cardiff University, Wales, UK. Correspondence: Sinead Brophy, PhD, College of Medicine,

Swansea University, Swansea SA2 8PP, UK. E-mail: s.brophy@swansea.ac.uk

Received 18 November 2012; accepted 24 January 2013

2013 by the American College of Gastroenterology

The American Journal of GASTROENTEROLOGY

STOMACH

nature publishing group

STOMACH

B Sinead et al.

is present before the prescription of PPI. Therefore, the incidence

of GI infection in a given population before and after the use of PPI

has not been evaluated. This means that it remains unclear if the

increased risk of GI infection is owing to factors in the population

associated with the prescription of PPIs (such as comorbidities,

lifestyle factors, or older age) or to the medications. Therefore, this

study used Campylobacter and Salmonella infections as examples

of significant GI infections, and compared the incidences of these

infections over a 12-month period before and after the prescription of PPIs, thus controlling for individual confounding factors

by using the same patients as their own control. The effect of time

is also examined by comparing these PPI patients with patients

not prescribed a PPI during the duration of the study follow-up

(19902010) and with controls matched for time period. Thus,

there is the exposed group (patient post PPI) and three different

controls; (1) non-exposed self controls (patient pre-PPI), (2) nonPPI patients in the year 1991 and again in 2009, in order to examine incidence owing to time changes, and (3) non-PPI controls

matched on date (day, month, year) with those prescribed a PPI to

control for time changes.

Table 1. Read codes used

PPI

a6b%, a6c%, a6e%, a6f%, a6h%

H2RA

a61.., a611., a612., a613., a614., a615., a616.,

a617. ,a618., a619., a61a., a61A., a61b., a61B.,

a61c., a61C., a61d., a61D., a61e., a61E., a61f.,

a61F., a61g., a61G., a61H., a61I., a61J., a61K.,

a61L., a61M., a61N., a61O., a61P., a61Q., a61R.,

a61s., a61S., a61t., a61T., a61u., a61U., a61v.,

a61w., a61x., a61y., a61z., a62.., a621., a622.,

a623., a624., a625., a626., a627., a628., a629.,

a62A., a62B., a62C., a62D., a62E., a62F., a62G.,

a62H., a62I., a62J., a62K., a62L., a62M., a62N.,

a62O., a62P., a62Q., a62u., a62v., a62v., a62w.,

a62x., a62y., a62z., a68.., a681., a682., a683.,

a684., a69.., a691., a692., a693., a694., a695.,

a696., a697., a698., a6d.., a6d1., a6d2

Campylobacter

A0743

Salmonella

A02., A020., A021., A0220, A022z, A02y., A02z.,

Ayu02, Ayu03

Antibiotic and

antifungals/virals

e%

Arthritis

N%

Immunosupresants

h%

METHODS

Oral steroid

6633.,663a.,663F.,663G.

Routinely collected data

Leukaemia

B64%,B65%,B66%,B67%,B68%,B69%

Lymphoma

B602%

Splenectomy

78401,78403,78410,78404

Aspirin

bu2%, di1%, j11%, blm%

Naproxen

j2c%,di8%

Ibuprofen

di6%, dic%, j28%, j2p%, j2t%, ja%

Bowel infection

(ICD-10)

K58%, R19%

Bowel infection

(OPCS 4)

H23%, H24%, H25%, H62%, Z29%

Campylobacter

(ICD-10)

A045

Salmonella

(ICD-10)

A029, A020, A021, A022, A028

The Health Information Research Unit (HIRU) at the College

of Medicine at Swansea University represents part of the Welsh

Assembly Governments commitment to the UK Clinical Research

Collaboration. The main aim of HIRU is to realise the potential of

electronically held routinely collected information to conduct and

support health-related research, and HIRU has set up the Secure

Anonymised Information Linkage (SAIL) databank to achieve this

(15,16). The SAIL databank brings together and links a wide range

of person-based data from multiple sources relevant to health. SAIL

utilises a range of measures to ensure that the data are anonymous

and secure, and that they can be safely utilised for research within

a robust information governance framework (15). The range of

complementary sets of data includes existing routinely collected

data sets such as general practitioner (GP) records, out-patients

clinical data, in-patients episodes, accident and emergency department, pathology, and social services; plus special feeds of data such

as clinical data from rheumatologists. Thus SAIL has been established using disparate data sets, and close to 2 billion records from

multiple health and social care service providers have been loaded

to date, with further growth in progress. Currently 35% (168/484)

of the GP practices in Wales provide data to SAIL, giving 1,913,925

(40%) individuals out of 4,713,970 registered with a GP practice in

Wales over the 20 years follow-up period. The percentage of male

is 49% in both the total population and the SAIL sample, and mean

age is 39.8 in both the population and the sample.

sets to be included in SAIL are subjected to a matching process

using the MACRAL (Matching Algorithm for Consistent Results

in Anonymised Linkage) algorithm to create a unique, encrypted

anonymised linking field for each person (16). The use of an anonymised linking field enables anonymous linkage at the person

level and allows us to follow the patient pathway through the NHS

system both retrospectively and prospectively while preserving

patient privacy.

Data linkage

Ethics

Data linkage of anonymous data sets is made possible by the

allocation of a consistent, unique identifier to each individual.

This is carried out by an NHS Trusted Third Party so that HIRU

does not handle personal identifiable data. In this process, data

The data held by HIRU in the SAIL system are anonymised and

have been obtained with the permission of the relevant Caldicott

Guardian/Data Protection Officer; therefore the National Research

Ethics Service has stated that no ethical review is required.

The American Journal of GASTROENTEROLOGY

H2RAs, histamine receptor antagonists; PPI, proton pump inhibitor.

VOLUME 104 | XXX 2013 www.amjgastro.com

PPI and Camplyobacter/Salmonella Infection

Average age (s.d.)

PPI patients

(n =358,938)

Non-PPIa

(n =1,523,828)

46% (119,313)

49.5% (4107)

58.05 (16.7)

51.04 (19.6)

PPI patients

(n =358,938)

Non-PPIa

(n =1,523,828)

020 years

10/10,222

(0.98 per 1,000)

253/349,755

(0.72 per 1,000)

2140 years

69/74,536

(0.93 per 1,000)

137/474392

(0.29 per 1,000)

4160 years

100/123,424

(0.81 per 1,000)

95/298,093

(0.31 per 1,000)

More than 60

109/167,515

(0.65 per 1,000)

93/321,242

(0.29 per 100)

GI infection by age (Salmonella)

Prescription in previous 12 months

H2RAb

10.3% (36,800)

0.5% (4,181)

Antibiotic

40% (146,377)

6.6% (52,287)

0.12% (440)

0.01% (100)

33.7% (120,820)

3.6% (28,252)

2.6% (9,302)

0.21% (1,642)

Diagnosed with arthritis

(before start date)

23.2% (83,240)

3.4% (26,549)

Bowel surgery

(before start date)

1.15% (4,130)

0.05% (405)

GI infection by season

(Campylobacter)

N=3,447

N=3,533

Spring (MarchMay)

760 (22%)

817 (23%)

Summer

(JuneAugust)

1058 (31%)

1189 (34%)

Autumn

(SeptemberNovember)

909 (26%)

894 (25%)

Winter

(DecemberFebruary)

720 (21%)

633 (18%)

N=128

N=190

Spring (MarchMay)

27 (21%)

46 (24%)

Summer (JuneAugust)

38 (30%)

50 (26%)

Analysis

Autumn

(SeptemberNovember)

38 (30%)

49 (26%)

Winter

(DecemberFebruary)

25 (19%)

45 (24%)

All records were examined for a diagnosis of the human Campylobacter GI infection or Salmonella GI infection (see Table 1) within

12 months of being prescribed a PPI, or within 12 months of a

randomly selected date for the non-PPI comparison group. Of

the patients prescribed a PPI, 19% were prescribed a PPI between

1990 and 1999 and 81% were prescribed a PPI between 2000 and

2010 (see Figure 1). The number of Campylobacter or Salmonella

GI infections were assessed for (a) the 12-month period before

PPI prescription, (b) the 12-month period post PPI prescription,

(c) patients not prescribed a PPI (12 months before date and 12

months after date). For the non-PPI patients, we examine before

and after the dates of 1991 and before and after 2009. These subsets of the single cohort were chosen to examine the effect of

time on infection rates. Finally, we selected a sample matched for

date with the PPI patients (matched on day, month, year). The

matched samples were used to control for variations in infection

rate with time. STATA version 11 using the st command was used

to examine incidence of infection over a 12-month period in all

groups. Time to event analysis was used to examine infection in

the year before prescription of PPI compared with the year after

the PPI. Cox regression models were used to compare the incidence of infection over each of the two 12-month periods in those

with a PPI prescription and controls, using the cluster command

to produce robust s.e.s. Chi-squared tests were used to examine

Oral steroid

NSAID

Immunosuppressants

GI infection by season

(Salmonella)

GI infection by gender (Campylobacter)

Male

148/119,110

(1.24 per 1,000)

113/412,942

(0.27 per 1,000)

Female

142/140,039

(1.01 per 1,000)

79/421,068

(0.19 per 1,000)

GI infection by age (Campylobacter)

020 years

11/10,222

(1.08 per 1,000)

73/349,755

(0.21 per 1,000)

2140 years

85/74,536

(1.14 per 1,000)

74/474,392

(0.16 per 1,000)

4160 years

146/123,424

(1.18 per 1,000)

51/298,083

(0.17 per 1,000)

More than 60

196/167,515

(1.17 per 1,000)

22/321,242

(0.07 per 1,000)

GI infection by gender (Salmonella)

Male

62/119,313

(0.52 per 1,000)

84/419,703

(0.20 per 1,000)

Female

66/140,248

(0.47 per 1,000)

106/418,904

(0.25 per 1,000)

Table 2 Continued

2013 by the American College of Gastroenterology

H2RAs, histamine receptor antagonists; PPI, proton pump inhibitor.

a

20082009.

b

Histamine Receptor Antagonists (H2RAs).

Approval was obtained from the HIRU Information Governance

Review Panel to use the SAIL system for this research question.

Study population

Anonymised records from 168 general practices out of 484 in

Wales were available within the SAIL databank. These records

were used to select patients who were prescribed a PPI and were

compared with those not prescribed a PPI between the years

1990 and 2010. The first prescription of PPI (see Table 1 and

Table 2) were selected. Data for infection were collected from the

GP records, in-patient and out-patient datasets.

The American Journal of GASTROENTEROLOGY

STOMACH

Table 2. (Continued)

Table 2. Population characteristics

Proportion male

Rate PPI per 1,000,000 Copylobacter

per 100,000,000 Salmonella per 10,000,0000

B Sinead et al.

STOMACH

150,000

PPI

Campylobacter

Salmonella

100,000

50,000

0

1990

1995

2000

2005

2010

Year

Figure 1. Number of people with a precription of PPI (per 1,000,000) or with a diagnosis of Campylobacter or Salmonella (per 100,000,000).

the seasonality of infection between PPI users (before PPI

prescription) and non-users. Prior event rate ratio (PERR) (17)

was used to control for unmeasured confounding. In this method,

neither the exposed nor unexposed patients are treated with the

study drug before the start of the study. This method assumes that

the hazard ratio of the exposed to unexposed for a specific outcome before the start of the study reflects the combined effect of

all confounders (both measured and unmeasured) independent

of any influence of the treatment. To apply the PERR adjustment

method, we divided the unadjusted hazard ratio of date-matched

exposed group versus date-matched unexposed group after PPI

prescription by the unadjusted hazard ratio of exposed versus

unexposed before prescription. PERR-adjusted HR = HRs/HRp

were p = prior events and s = study events.

RESULTS

Sample characteristics

In this study, 18.7% of all patients were prescribed a PPI. Patients

prescribed a PPI were older with a greater frequency of females

compared with controls (Table 2). The PPI patients were more

likely to have other factors associated with GI symptoms such

as antibiotic use, oral steroid use, NSAID prescription, immunosuppressant medication, bowel surgery, or a diagnosis of arthritis.

Incidence of infection

Examining the effect of time: The rates of Campylobacter and

Salmonella infections were higher after a prescription for PPI

compared with rates in the same individual for the period before

prescription (Table 3). In fact, the risk of Campylobacter infection is 1.46 times higher after a PPI prescription compared with

before prescription. However, this increased rate is also seen in

the non-PPI patients. In fact, patients who are prescribed a PPI

have a higher risk of infection compared with controls even before

their prescription. Patients prescribed a PPI were already at 6.91

(95% CI: 5.169.26) times the risk of Campylobacter infection

compared with people not prescribed an acid suppression drug

The American Journal of GASTROENTEROLOGY

(see Table 3. Patients matched for dateBefore). The absolute

risk of Campylobacter infection increases by 0.55 per 1,000 person years of follow-up after a PPI prescription (Table 3) and by

0.03 per 1,000 person years of follow-up for Salmonella infection

(Table 4). However, this increase could be owing to changes in

diagnosis with time, as the same increase in trend is seen in the

non-PPI controls (Tables 3, 4 and Figure 1). For example, in the

control group the increase was 0.07 extra diagnosed with Campylobacter per 1,000 person years of follow-up between years 2008

and 2009 and 2009 and 2010 (Table 3 and Figure 1).

Examining the effect of unmeasured confounders: The PERR for

Campylobacter was 1.17 (95% CI 0.741.61) based on an unadjusted prior hazard ratio for the PPI/non-PPI date-matched sample of 6.54 (1.184/0.181) and an unadjusted post hazard ratio of

7.68 (1.73/0.225).

The PERR for Salmonella was 1.00 (95% CI: 0.51.5) based on an

unadjusted prior hazard ratio for the PPI/non-PPI date-matched

sample of 2.8 (0.11/0.03) and an unadjusted post hazard ratio of

2.78 (0.14/0.05).

Sensitivity analysis

Patients prescribed a PPI were more likely to have previously been prescribed a H2RA. In these patients, this may have

increased their prior rate of infection. We examined the prior

rate in those matches where H2RA had not previously been

prescribed (n = 321200 pairs out of a previous 358938 pairs).For

Campylobacter, this gave a prior unadjusted HR of 6.29 (1.07/0.17)

and a post unadjusted ratio of 7.86 (1.69/0.22) with a PERR of

1.22 (95% CI: 0.791.71).

The controls have fewer risk factors (antibiotic prescription,

NSAID use, etc.) compared with PPI users. Therefore, we examined those pairs where the control does have a risk factor (e.g.,

prescription for oral steroids, NSAIDS, antibiotics, diagnosis of

diabetes, or bowel surgery). The prior unadjusted HR was 1.65

(1.07/0.65) and post unadjusted ratio was 1.85 (1.74/0.94) with a

PERR of 1.12 (95% CI: 0.591.6).

VOLUME 104 | XXX 2013 www.amjgastro.com

PPI and Camplyobacter/Salmonella Infection

PPI patients

Campylobacter infection

Person years follow-up

Incidence per 1,000 per

year (95% CI)

Non-exposed (before

PPI prescription)

Exposed (post PPI

prescription)

425

622

358,892

358,651

1.18 (1.0761.3)

1.73 (1.61.8)

1.46 (1.291.65)

Hazard ratio

(exposed vs unexposed) a

Non-PPI patients

(selected years)

Campylobacter infection

Person years follow-up

Incidence per 1,000 per

year (95% CI)

Incidence per 1,000 per

year (95% CI)

54

57

577,620

577,604

0.09 (0.070.12)

0.1 (0.080.13)

Person years follow-up

Incidence per 1,000 per

year (95% CI)

126

199

997,476

994,729

0.13 (0.1 to 0.15)

0.20 (0.170.23)

1.58 (1.261.97)

PPI

Incidence per 1,000 per

year (95% CI)

39

50

359,139

359,158

0.11 (0.080.15)

0.139 (0.10.18)

1.2 (0.841.9)

Salmonella infection

Person years follow-up

Incidence per 1,000 per

year (95% CI)

Years 19901991

Years 19911992

43

41

577,640

577,631

0.074 (0.050.1)

0.071 (0.050.09)

0.95 (0.621.5)

Years 20082009

Salmonella infection

Person years follow-up

Incidence per 1,000 per

year (95% CI)

Non-PPI

Years 20092010

42

46

782,652

782,667

0.05 (0.040.07)

0.06 (0.040.07)

Hazard ratio (before/after)

425

65

358,938

359,120.9

1.184 (1.071.3)

0.181 (0.140.23)

6.91 (5.169.26)

1.04 (0.681.59)

Patients matched for date

PPI

Non-PPI

Salmonella infection

39

14

Person years follow-up

Incidence per 1,000 per

year (95% CI)

359,139

359,150

0.11 (0.080.15)

0.039 (0.020.065)

3.1 (1.75.7)

Hazard ratio

(PPI/non-PPI)b

After

Campylobacter infection

Exposed (post PPI

prescription)

Before

Hazard ratio

(PPI/non-PPI)b

Person years follow-up

Incidence per 1,000 per

year (95% CI)

Years 20092010

Before

Campylobacter infection

Person years follow-up

Non-exposed (before

PPI prescription)

Hazard ratio

(before/after)a

1.061 (0.731.53)

Hazard ratio (before/after)a

Patients matched for date

Salmonella infection

Non PPI patients

Years 19911992

Years 20082009

Person years follow-up

PPI patients

Hazard ratio (exposed vs.

unexposed)a

Years 19901991

Hazard ratio (before/after)a

Campylobacter infection

Table 4. Incidence rate for Salmonella infection

After

622

81

358,651

359,147

1.73 (1.61.88)

0.225 (0.1810.28)

Hazard ratio

(PPI/non-PPI)b

9.50 (7.412.2)

CI, confidence interval; PPI, proton pump inhibitor.

a

Clustered on individual ID.

b

Adjusted for age and gender and clustered on matched pair ID.

Salmonella infection

Person years

follow-up

Incidence per 1,000 per

year (95% CI)

Hazard ratio

(PPI/non-PPI)b

50

18

359,158

359,176.9

0.139 (0.10.18)

0.05 (0.030.08)

3.1 (1.825.3)

CI, confidence interval; PPI, proton pump inhibitor.

a

Clustered on individual ID.

b

Adjusted for age and gender and clustered on matched pair ID.

DISCUSSION

This study does not find evidence that PPI is associated with

increased rates of GI infection. Patients prescribed a PPI had a

higher rate of Salmonella and Campylobacter infection before

receiving their PPI prescription compared with those who did

not receive a PPI prescription during the study period. Both those

prescribed a PPI and those who were not prescribed a PPI had

an increase in the rate of Salmonella and Campylobacter infection

with time. Thus, increases in GI infection after a PPI prescription

2013 by the American College of Gastroenterology

are likely to be owing to a general increase in infection diagnosis

rather than a result of the PPI prescription.

This is the first known study to examine the incidence of

Campylobacter and Salmonella GI infection before and after first

prescription for PPI. This method means that the PPI patients act

as their own exposed/non-exposed controls and thus confounding

owing to patient characteristics is not an issue. The large sample

numbers available in routine data means rare conditions such as

The American Journal of GASTROENTEROLOGY

STOMACH

Table 3. Incidence rate for Campylobacter infection

STOMACH

B Sinead et al.

GI infections can be followed up using a cohort design. However,

there are limitations in working with routine data. Cases of infection may be missed as this method can only record the cases who

presented to their GP and had a stool sample sent to microbiology

for testing and diagnosis. Thus, we can only report on incidence of

diagnosed Campylobacter or Salmonella infection and cannot estimate true incidence including undiagnosed infections. However,

this limitation applies to all studies in this area. We chose major

significant infections (Campylobacter and Salmonella) in order to

minimise this ascertainment problem. However, people prescribed

a PPI are more likely to be diagnosed as they are more likely to be

attendees at GP practice. Thus, non-PPI control may have a higher

rate, closer to PPI patients, than we present here.

Patients prescribed a PPI may have been more likely to buy overthe-counter medicines before the prescription of the PPI, this is

seen in the higher proportion also prescribed a H2RA. However,

in Wales where prescriptions are free, more people seek a prescription rather than pay for the same medication over the counter.

Therefore, we feel this bias may be small and the sensitivity analysis

removing patients with prior prescription for H2RA did not demonstrate a real change in the findings.

The accuracy of diagnosis will have improved with time, and

testing methods used changes with time, moving to more standardised and genomic (e.g., PCR) testing. This may explain higher

diagnosis rates among all people examined with time.

Previous studies have used a case control design matching on

those with GE infection compared with those without (18,1), and

shown an association with acid suppression and increased risk of

enteric infection. Recommendations (1) have been for prospective

studies to examine if the association is causal. This study performs a

cohort study and shows, in terms of a temporal relationship between

PPI and infection, this association is unlikely to be causal. Previous

case control studies may have suffered from a healthy control bias,

as the sensitivity analysis using non-healthy controls (i.e., those

with prescriptions for different medications (NSAIDS, antibiotics,

and steroids)) showed similar rates to those taking PPI medication.

In summary, there is an association between taking a PPI and GI

infection with Salmonella or Campylobacter. However, this risk is

largely owing to difference between those who are prescribed PPIs

and those who are not, rather the PPI prescription. PPI use is associated with an increased rate of 0.6 per 1,000 person years of follow-up for Campylobacter and 0.18 per 1,000 years of follow-up for

Salmonella, and this increase is comparable to that seen in controls

and can be explained by changing time trend rates in diagnosis.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

Guarantor of the article: Sinead Brophy, PhD.

Specific author contributions: All authors were involved in the

study design; data were analysed by S.B., M.A.R., and S.M.Z.; and

the manuscript was drafted by S.B., K.H.J., M.A.R., and M.D.A.

Input and amendments were made by A.J., N.F., R.A.L., and F.D.

Financial support: This study is funded by a grant from the

National Institute Social Care and Health Research (NISCHR)

within the Welsh Assembly.

Potential competing interests: None.

The American Journal of GASTROENTEROLOGY

Data access: This study makes use of anonymised data held in the

Secure Anonymised Information Linkage (SAIL) system, which

is part of the national e-health records research infrastructure for

Wales. We would like to acknowledge all the data providers who

make anonymised data available for research.

Study Highlights

WHAT IS CURRENT KNOWLEDGE

3PPIs are among the most commonly prescribed drug groups

worldwide.

3PPIs have been reported to increase the rates of GI

infections such as Salmonella and Campylobacter.

WHAT IS NEW HERE

3Using a cohort study of 358,938 people prescribed PPI, we

did not find evidence that the increased risk is attributable

to the PPI.

3It is more likely that association with infection is owing to

inherent factors within the patient that are associated with

PPI prescription.

3Work is needed to examine why people prescribed a PPI are

more prone to infection even before their PPI prescription.

REFERENCES

1. Leonard J, Moayyedi JK. Systematic review of the risk of enteric infection

in patients taking acid suppression. Am J Gastroenterol 2007;102:204756,

quiz 2057.

2. Huang JQ, Hunt RH. Pharmacological and pharmacodynamic essentials of

H(2)-receptor antagonists and proton pump inhibitors for the practising

physician. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol 2001;15:35570.

3. National Institute for Clinical Excellence. Guidance on the use of proton

pump inhibitors for the treatment of dyspepsia, 2000.

4. National Institute of Clinical Excellence. Managment of dyspepsia in adults

in primary care, 2005.

5. Stevens V, Dumyati G, Brown J et al. Differential risk of Clostridium

difficile infection with proton pump inhibitor use by level of antibiotic

exposure. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2011;20:103542.

6. Deshpande A, Pant C, Pasupuleti V et al. Association between proton pump

inhibitor therapy and Clostridium difficile infection in a meta-analysis.

Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2012;10:22533.

7. Howell MD, Novack V, Grgurich P et al. Iatrogenic gastric acid suppression

and the risk of nosocomial Clostridium difficile infection. Arch Intern Med

2010;170:78490.

8. Linsky A, Gupta K, Lawler EV et al. Proton pump inhibitors and risk

for recurrent Clostridium difficile infection. Arch Intern Med

2010;170:7728.

9. Turco R, Martinelli M, Miele E et al. Proton pump inhibitors as a risk factor

for paediatric Clostridium difficile infection. Aliment Pharmacol Ther

2009;31:7549.

10. FDA. Warning on Sereral Proton Pump Inhibitors. http://www.medicalreference.net/2012/02/breaking-news-fda-issues-warning-on.html,

2012.

11. Dublin S, Walker RL, Jackson ML et al. Use of proton pump inhibitors and

H2 blockers and risk of pneumonia in older adults: a population-based

case-control study. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2010;19:792802.

12. Johnstone J, Nerenberg K, Loeb M. Meta-analysis: proton pump inhibitor

use and the risk of community-acquired pneumonia. Aliment Pharmacol

Ther 2010;31:116577.

13. Ran L, Khatibi NH, Qin X et al. Proton pump inhibitor prophylaxis

increases the risk of nosocomial pneumonia in patients with an

intracerebral hemorrhagic stroke. Acta Neurochir Suppl 2011;111:4359.

14. Bavishi C, Dupont HL. Systematic review: the use of proton pump

inhibitors and increased susceptibility to enteric infection. Aliment

Pharmacol Ther 2011;34:126981.

VOLUME 104 | XXX 2013 www.amjgastro.com

PPI and Camplyobacter/Salmonella Infection

2013 by the American College of Gastroenterology

18. Garcia Rodriguez L, Ruigomez A, Panes J. Use of acid-suppressing drugs and

the risk of bacterial gastroenteritis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2007;5:141823.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons

Attribution-NonCommercial-Share Alike 3.0

Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://

creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/

The American Journal of GASTROENTEROLOGY

STOMACH

15. Ford DV, Jones KH, Verplancke JP et al. The SAIL Databank: building a

national architecture for e-health research and evaluation. BMC Health

Serv Res 2009;9:157.

16. Lyons RA, Jones KH, John G et al. The SAIL Databank: linking multiple

health and social care datasets. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak 2009;9:3.

17. Tannen RL, Weiner MG, Xie D. Use of primary care electronic medical record

database in drug efficacy research on cardiovascular outcomes: comparison of

database and randomised controlled trial findings. BMJ 2009;338:b81.

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5822)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1093)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (852)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (898)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (540)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (349)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (822)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (403)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Basic Medical Billing and Imp Questions.Document16 pagesBasic Medical Billing and Imp Questions.Koppolu SatyaNo ratings yet

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- ILNAS-EN 17141:2020: Cleanrooms and Associated Controlled Environments - Biocontamination ControlDocument9 pagesILNAS-EN 17141:2020: Cleanrooms and Associated Controlled Environments - Biocontamination ControlBLUEPRINT Integrated Engineering Services0% (1)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- Temporary Anchorage Devices - NandaDocument435 pagesTemporary Anchorage Devices - NandaAmrita Shrestha100% (5)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Rehabilitation Centre For Psychiatric People: Facilitate The Integration of Recovered Mental Patients Into The CommunityDocument8 pagesRehabilitation Centre For Psychiatric People: Facilitate The Integration of Recovered Mental Patients Into The CommunitySaki Saki SakiNo ratings yet

- AI Playbook For The Enterprise - Quantiphi - FINALDocument14 pagesAI Playbook For The Enterprise - Quantiphi - FINALlikhitaNo ratings yet

- Health Policies and Vulnerable PopulationsDocument5 pagesHealth Policies and Vulnerable PopulationsVENESSANo ratings yet

- June04.2014establishment of Lung Center of The Philippines in The Visayas and Mindanao ProposedDocument1 pageJune04.2014establishment of Lung Center of The Philippines in The Visayas and Mindanao Proposedpribhor2No ratings yet

- Test Bank For Health Psychology 9th Edition Shelley Taylor DownloadDocument25 pagesTest Bank For Health Psychology 9th Edition Shelley Taylor Downloadwoodwardpunction2vq46zNo ratings yet

- Classification of Facilities (Doh Ao-0012a)Document42 pagesClassification of Facilities (Doh Ao-0012a)Marissa AsimNo ratings yet

- 4as DLPDocument5 pages4as DLPCASTRO, JANELLA T.No ratings yet

- Market-Analysis of PfizerDocument4 pagesMarket-Analysis of PfizerAnadi RanjanNo ratings yet

- Generic Substitution Binu ThapaDocument13 pagesGeneric Substitution Binu ThapabimuNo ratings yet

- IDPH Credentialing Form 97 ProDocument42 pagesIDPH Credentialing Form 97 ProherytsNo ratings yet

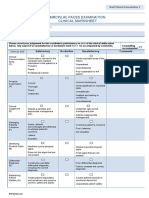

- Mark Sheet Station 05Document2 pagesMark Sheet Station 05Theepan ThuraiNo ratings yet

- DOH Administrative Order No 2020 0037Document17 pagesDOH Administrative Order No 2020 0037John Philip TiongcoNo ratings yet

- Nurs FPX 4030 Assessment 2 Determining The Credibility of Evidence and ResourcesDocument5 pagesNurs FPX 4030 Assessment 2 Determining The Credibility of Evidence and ResourcesEmma WatsonNo ratings yet

- HEALTH ED QUIZ Determinants of LearningDocument2 pagesHEALTH ED QUIZ Determinants of Learningteabagman100% (1)

- CMH Board StatementDocument2 pagesCMH Board StatementMaine Trust For Local NewsNo ratings yet

- Area C Cluster 10 Barangay Barualte AND Barangay Imelda: Tingao, Bandar - Ali I. Ventigan, Jonathan LDocument19 pagesArea C Cluster 10 Barangay Barualte AND Barangay Imelda: Tingao, Bandar - Ali I. Ventigan, Jonathan LjlventiganNo ratings yet

- Basic Life Suppor T: Monalyn B. La-Ao, RN Keverne Colas, RNDocument51 pagesBasic Life Suppor T: Monalyn B. La-Ao, RN Keverne Colas, RNAudi Kyle SaydovenNo ratings yet

- Functional AssessmentDocument21 pagesFunctional AssessmentStvns BdrNo ratings yet

- Schedule of Virtual Classes For Nclex RN 2020Document3 pagesSchedule of Virtual Classes For Nclex RN 2020Jasmine ClaireNo ratings yet

- Request For Proposal (RFP) #4794 Physiotherapy Services: Sponsored by Health PEI - Community Hospitals WestDocument29 pagesRequest For Proposal (RFP) #4794 Physiotherapy Services: Sponsored by Health PEI - Community Hospitals WestDiganta DasNo ratings yet

- Passage A1Document7 pagesPassage A1hamid faridNo ratings yet

- Caraveo 2007Document8 pagesCaraveo 2007Karla SuárezNo ratings yet

- CDC Malaria ProgramDocument2 pagesCDC Malaria ProgramabthakurNo ratings yet

- MCNHNDocument64 pagesMCNHNKate100% (1)

- 01 - 08 - Chapter 8 INFANT - CHILD MORTALITY-NDHS - BAY - Chap8 - July28 Rev-Formatted08042014 - Revaug14 PDFDocument10 pages01 - 08 - Chapter 8 INFANT - CHILD MORTALITY-NDHS - BAY - Chap8 - July28 Rev-Formatted08042014 - Revaug14 PDFIrwin FajaritoNo ratings yet

- Information From The British Association of Urological Surgeons (BAUS) About Bladder CathetersDocument6 pagesInformation From The British Association of Urological Surgeons (BAUS) About Bladder CathetersralphholingsheadNo ratings yet

- HEALTH 10 QUARTER 1-MOD-2-PRELIM - v3Document10 pagesHEALTH 10 QUARTER 1-MOD-2-PRELIM - v3Macquen Balucio50% (6)