Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Zayani - 'The Labyrinth of The Gaze'

Zayani - 'The Labyrinth of The Gaze'

Uploaded by

Kam Ho M. WongCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5822)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1093)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (852)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (898)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (540)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (349)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (822)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (403)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Mercruiser Service Manual #14 Alpha I Gen II Outdrives 1991-NewerDocument715 pagesMercruiser Service Manual #14 Alpha I Gen II Outdrives 1991-NewerM5Melo100% (10)

- The Dated Alexander Coinage of Sidon and Ake (1916)Document124 pagesThe Dated Alexander Coinage of Sidon and Ake (1916)Georgian IonNo ratings yet

- Glitsos - 'Vaporwave, or Music Optimised For Abandoned Malls'Document19 pagesGlitsos - 'Vaporwave, or Music Optimised For Abandoned Malls'Kam Ho M. WongNo ratings yet

- Winge - 'Costuming The Imagination Origins of Anime and Manga Cosplay'Document13 pagesWinge - 'Costuming The Imagination Origins of Anime and Manga Cosplay'Kam Ho M. WongNo ratings yet

- Roviello - 'The Hidden Violence of Totalitarianism'Document9 pagesRoviello - 'The Hidden Violence of Totalitarianism'Kam Ho M. WongNo ratings yet

- Darley - 'Does Aquinas' Notion of Analogy Violate The Law of Non-Contradiction'Document10 pagesDarley - 'Does Aquinas' Notion of Analogy Violate The Law of Non-Contradiction'Kam Ho M. WongNo ratings yet

- Priest - 'Was Marx A Dialetheist'Document9 pagesPriest - 'Was Marx A Dialetheist'Kam Ho M. WongNo ratings yet

- Yu - 'Confucius' Relational Self and Aristotle's Political Animal'Document21 pagesYu - 'Confucius' Relational Self and Aristotle's Political Animal'Kam Ho M. WongNo ratings yet

- Colletta - 'Political Satire and Postmodern Irony in The Age of Stephen Colbert and Jon Stewart'Document20 pagesColletta - 'Political Satire and Postmodern Irony in The Age of Stephen Colbert and Jon Stewart'Kam Ho M. Wong100% (1)

- Bennett - 'Hermetic Histories'Document37 pagesBennett - 'Hermetic Histories'Kam Ho M. WongNo ratings yet

- Piper - 'Skeptical Theism and The Problem of Moral Aporia' PDFDocument15 pagesPiper - 'Skeptical Theism and The Problem of Moral Aporia' PDFKam Ho M. WongNo ratings yet

- Understanding Psychology Chapter 1Document3 pagesUnderstanding Psychology Chapter 1Mohammad MoosaNo ratings yet

- Strategies For Weak & Crisis Ridden BusinessesDocument13 pagesStrategies For Weak & Crisis Ridden BusinessesApoorwa100% (1)

- Pertemuan 2 - EXERCISES Entity Relationship ModelingDocument10 pagesPertemuan 2 - EXERCISES Entity Relationship Modelingjensen wangNo ratings yet

- UntitledDocument1 pageUntitledГаврило ПринципNo ratings yet

- Aluda Move (Rayan Nadr J Zahra Ozair)Document2 pagesAluda Move (Rayan Nadr J Zahra Ozair)varaxoshnaw36No ratings yet

- Effect of Oral Cryotherapy in Preventing Chemotherapy Induced Oral Stomatitis Among Childhood Acute Lymphoblastic LeukemiaDocument10 pagesEffect of Oral Cryotherapy in Preventing Chemotherapy Induced Oral Stomatitis Among Childhood Acute Lymphoblastic LeukemiaIjahss JournalNo ratings yet

- Dinagat HVADocument55 pagesDinagat HVARolly Balagon CaballeroNo ratings yet

- Shezan Project Marketing 2009Document16 pagesShezan Project Marketing 2009Humayun100% (3)

- Systematix Sona BLW Initiates CoverageDocument32 pagesSystematix Sona BLW Initiates Coveragejitendra76No ratings yet

- Occasional Paper 2 ICRCDocument82 pagesOccasional Paper 2 ICRCNino DunduaNo ratings yet

- Business Law Cpa Board Exam Lecture Notes: I. (CO, NO)Document27 pagesBusiness Law Cpa Board Exam Lecture Notes: I. (CO, NO)Shin MelodyNo ratings yet

- Collection of Windows 10 Hidden Secret Registry TweaksDocument9 pagesCollection of Windows 10 Hidden Secret Registry TweaksLiyoNo ratings yet

- Ahnan-Winarno Et Al. (2020) Tempeh - A Semicentennial ReviewDocument52 pagesAhnan-Winarno Et Al. (2020) Tempeh - A Semicentennial ReviewTahir AliNo ratings yet

- Nod 321Document12 pagesNod 321PabloAyreCondoriNo ratings yet

- The Role of The School Psychologist in The Inclusive EducationDocument20 pagesThe Role of The School Psychologist in The Inclusive EducationCortés PameliNo ratings yet

- FRANKL, CROSSLEY, 2000, Gothic Architecture IDocument264 pagesFRANKL, CROSSLEY, 2000, Gothic Architecture IGurunadham MuvvaNo ratings yet

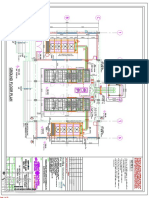

- Dg-1 (Remote Radiator) Above Control Room Slab: 05-MAR-2018 Atluri Mohan Krishna (B845)Document32 pagesDg-1 (Remote Radiator) Above Control Room Slab: 05-MAR-2018 Atluri Mohan Krishna (B845)Shaik AbdullaNo ratings yet

- GRADE 8 NotesDocument5 pagesGRADE 8 NotesIya Sicat PatanoNo ratings yet

- Create BAPI TutorialDocument28 pagesCreate BAPI TutorialRoberto Trejos GonzalezNo ratings yet

- Form LRA 42Document3 pagesForm LRA 42Godfrey ochieng modiNo ratings yet

- Asuhan Keperawatan Pada Klien Dengan Pasca Operasi Hernia Inguinalis Di Lt.6 Darmawan Rs Kepresidenan Rspad Gatot Soebroto Jakarta Tahun 2019Document7 pagesAsuhan Keperawatan Pada Klien Dengan Pasca Operasi Hernia Inguinalis Di Lt.6 Darmawan Rs Kepresidenan Rspad Gatot Soebroto Jakarta Tahun 2019Ggp Kristus Raja SuliNo ratings yet

- Marketable Avenues: 14,15,16 April 2023Document31 pagesMarketable Avenues: 14,15,16 April 2023Avaneesh Natraj GujranNo ratings yet

- Strategicmanagement Case StudiesDocument62 pagesStrategicmanagement Case StudiesElmarie Versaga DesuyoNo ratings yet

- Davis Michael 1A Resume 1Document1 pageDavis Michael 1A Resume 1Alyssa HowellNo ratings yet

- Public Administration - Meaning & Evolution - NotesDocument5 pagesPublic Administration - Meaning & Evolution - NotesSweet tripathiNo ratings yet

- CH 3 Online Advertising vs. Offline AdvertisingDocument4 pagesCH 3 Online Advertising vs. Offline AdvertisingKRANTINo ratings yet

- Final Defense in PR2Document53 pagesFinal Defense in PR2Friza ann marie NiduazaNo ratings yet

- Ip Talks Presentation - Keaune ReevesDocument2 pagesIp Talks Presentation - Keaune Reeveskarina talledoNo ratings yet

Zayani - 'The Labyrinth of The Gaze'

Zayani - 'The Labyrinth of The Gaze'

Uploaded by

Kam Ho M. WongOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Zayani - 'The Labyrinth of The Gaze'

Zayani - 'The Labyrinth of The Gaze'

Uploaded by

Kam Ho M. WongCopyright:

Available Formats

This article was downloaded by: [Universite De Paris 1]

On: 30 August 2013, At: 13:34

Publisher: Routledge

Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House,

37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK

Word & Image: A Journal of Verbal/Visual Enquiry

Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information:

http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/twim20

The labyrinth of the gaze: Nicholas of Cusa's mysticism

and Michel Foucault's panopticism

Mohamed Zayani

Published online: 14 Sep 2012.

To cite this article: Mohamed Zayani (2008) The labyrinth of the gaze: Nicholas of Cusa's mysticism and Michel Foucault's

panopticism, Word & Image: A Journal of Verbal/Visual Enquiry, 24:1, 92-102, DOI: 10.1080/02666286.2008.10444076

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/02666286.2008.10444076

PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE

Taylor & Francis makes every effort to ensure the accuracy of all the information (the Content) contained

in the publications on our platform. However, Taylor & Francis, our agents, and our licensors make no

representations or warranties whatsoever as to the accuracy, completeness, or suitability for any purpose of the

Content. Any opinions and views expressed in this publication are the opinions and views of the authors, and

are not the views of or endorsed by Taylor & Francis. The accuracy of the Content should not be relied upon and

should be independently verified with primary sources of information. Taylor and Francis shall not be liable for

any losses, actions, claims, proceedings, demands, costs, expenses, damages, and other liabilities whatsoever

or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with, in relation to or arising out of the use of

the Content.

This article may be used for research, teaching, and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic

reproduction, redistribution, reselling, loan, sub-licensing, systematic supply, or distribution in any

form to anyone is expressly forbidden. Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://

www.tandfonline.com/page/terms-and-conditions

The labyrinth of the gaze:

Nicholas of eusa's mysticism and

Michel Foucault's panopticism

Downloaded by [Universite De Paris 1] at 13:34 30 August 2013

MOHAMED ZAYANI

Panopticism, the title of Foucault's famous chapter in his book Discipline and

Punish,' derives fromJeremy Bentham's panopticon, an architectural plan to

reform prisons at the end of the eighteenth century. The fundamental

conception of this utopian project is to build an inspection house in which

prisoners are permanently subjected to an invisible and omnipresent

surveillance. The panopticon, as Bentham conceives it, is an annular

building composed of a central tower pierced with windows that overlook a

peripheral building. From this watch tower, and through the effect of

backlighting, a supervisor can constantly spy on the individuals enclosed in

segmented spaces all around it without ever being seen. Foucault uses the

principle on which the panopticon is built i.e. power through

transparency and subjection by illumination to account for the

technologies of observation and the mechanisms of power that organize

the social space in our contemporary society. Although Bentham's project

has never been realized, Foucault finds in its 'marvelous machine'2 a perfect

model for the new forms of control and exercise of power - one which is

not aimed at the body, but the soul. The focus of this machine is not on

punishing the individual but rather on knowing and altering him or her.

Panopticism, as Foucault points out, constitutes 'the technique, universally

widespread of coercion.'3 Its ultimate goal is the exercise of control and the

intensification and perfection of the new methods of power.

Not unlike Foucault, Michel de Certeau finds inspiration in an old text. In

search of a theoretical model, and unable to resist the invitation for an

expedient historical precedent, de Certeau rediscovers a neglected work in

an interesting article published posthumously entitled 'The Gaze: Nicholas

ofCusa'.4 A former Jesuit himself, de Certeau goes back to The Vision qfGod,5

a treatise concerning mystic theology by Cardinal Nicolaus Cusanus - a

fifteenth-century prelate, theologian, scholar, mathematician, philosopher

and reformer. Michel de Certeau focuses on the preface of this treatise, a

concise and propaedeutic introduction in which Cusa describes an

accompanying painting he used as the basis for the argument he developed

in his book. The animus informing the preface is to provide a transition from

the concrete example of the painting on which Cusa bases his argument to

the more abstract experience of the realization of the presence of God. It

describes an exercise that permits the transformation of a perceptual visual

experience into a theory of mystic vision. The preface is central and worth

quoting at length:

1- Michel Foucault, Discipline and Punish:

trans. Alan Sheridan (New

York: Vintage: 1975)'

History qf Prison,

2- Foucault, Discipline and Punish, p.202.

3- Foucault, Discipline and Punish, p.222.

4- Michel de Certeau, 'The Gaze: Nicholas

ofCusa', Diacritics, 17/3 (1987), pp. II-12. See

also de Certeau's 'Mysticism', Diacritics, 2212

(1992), pp. II-25 and 'What do we do when

we believe', in On Signs, ed. Marshall Blonsky

(Baltimore, MD: John Hopkins University

Press, 1985).

5- Nicholas Cusanus, The VISion qfGod, trans.

Evelyn Underhill (London: J.M. Dent &

sons, 1929).

Among the human products, I have nothing more appropriate to my intention

than the image of an all-seer, whose face is painted with an art so subtle that it

WORD & IMAGE, VOL. 24, NO. I, JANUARY-MARCH 2008

Word & Imuge ISSN 0266-6286 2008 Taylor & Francis

http://www.tandf.co.uk/journals/tf/02666286.htmI

DOl: IO.I080!02666280701405887

6- De Certeau, 'The Gaze', pp. II-12.

Downloaded by [Universite De Paris 1] at 13:34 30 August 2013

7- De Certeau, 'The Gaze', p. II.

8 - De Certeau, 'The Gaze', p. 24.

9-John Rajchman, 'Foucault's art of

seeing', October, 44 (1988), P.90.

seems to look at everything in the vicinity .... So that you should lack of nothing

in an exercise that requires the perceptible figure that was at my disposal, I am

sending you a painting that shows that figure of the all-seer, which I call the

icon of God. From whatever side you may examine it each of you will have the

experience of being as it were the only one to be seen by it .... Knowing that

the image remains fixed and immobile, he will be astonished at the movement

of this immobile gaze. If he fixes his eyes on it and walks from west to east, he

will discover that the image continually keeps its gaze fixed on him and that it

does not leave him either if he walks in the opposite direction .... He will see

that this gaze watches with extreme care over the smallest as over the largest

and over the totality of the universe. Starting from this perceptible

phenomenon, I propose, most loving brothers, to raise you up by an exercise

of devotion to mystic theology.6

The painting so described creates a texture of mediated experience akin to

the abstraction of the mystic experience that the book tries to achieve. The

inferences eusa makes in this 'perceptible experimentation'7 take the visible

world as its gambit though not as its game. By using a painting that is

reminiscent of an almost contemporary work of distinction, the Mona Lisa

(by a painter who often enough combined art, philosophy and science in his

work), eusa sought to instruct the monks of Tegernsee in the right kind of

observation and to initiate them to the mystic experience. In drawing a

relationship between the gaze in the painting and the gaze of God, in

converting an aesthetic experience to a mystical exercise, in passing from

perception to vision, from sight to insight, from an optical operation to a

mental exercise, eusa is arguing that theological things are better seen with

the mind's eye than with the fleshly eye, and that in order to have access to

the divine truth one has to follow an appropriate practice of seeing.

There is an arresting similarity between eusa's all-seeing gaze and

Foucault's panoptic gaze, which invites a comparative study of the two

models. The visual element occupies an eminent place in the works and

minds of both philosophers. In his preface, eusa uses the gaze in the

painting in a very conscious way. His ultimate goal is to draw a parallel

between the all-seeing gaze and the divine gaze. For him, mystic philosophy

is itself 'a discourse organized by a gaze.'8 eusa's distinction between two

ways of seeing - seeing with the eye and seeing with the mind - does not

just apply to the painting; it can be extended to the search for truth in

general. Looking at the perceptible image is a devotional exercise in which

one learns to realize the presence of divine things through human paths.

eusa opens his book with the assertion that what is true about the faceless

gaze is also true about the gaze of God himself; by following the eyes, one

will never lose sight of God. The highest knowledge, which is hitherto

inaccessible to human understanding, can be attained through contemplation.

Foucault also pays special attention to the gaze in his works. While the socalled politics of the gaze is part of his argument, vision is an aspect of his

thought. Foucault is what John Rajchman has termed 'a visual historian.'9

Rajchman's observation is the extension of Gilles Deleuze's contention that

seeing is a subject of interest as well as an underlying principle in the thought

of Michel Foucault. In 'Prison talk,' Foucault argues that to write history is

an exercise of magnification in which one makes visible and sclerotic what

93

Downloaded by [Universite De Paris 1] at 13:34 30 August 2013

was previously unseen, and that his whole project is 'to make visible the

constant articulation ... of Power and Knowledge."o But, as part of 'the

anti-visual discourse' of twentieth-century French thought, Foucault's

fascination with and use of the gaze, as Martin Jay points out," has

multiple facets. In 'Eye of power,' Foucault highlights the role the gaze plays

in reinforcing the techniques of power, but also insists that it is 'far from

being the only or even the principle system employed."2

Beyond the role that visual discourse plays in the thought of each of these

two thinkers, the two models, the all-seeing gaze in the painting and the

over-seeing gaze in the panopticon, share overriding similarities. It is clear

that there is a close relationship between observer/observed, on the one

hand, and subject/object, on the other hand. The structure of Foucault's

and Cusa's (pan)optic models is omnivoyant and their objects nonrecalcitrant. They do not allow for the existence of 'a no-man's gaze.' In

both instances, seeing is never a partial act. By definition, panoptic - a term

provisionally used here to describe both models - is that which commands

360 degrees of vision, that which has no zone of shade - no point mort, so to

speak. Under panopticism, there is no room for unruly actions; only full

effects.

The kind of vision both models command seems to replicate the divine

gaze. This affinity, however, should come as no surprise. Both visual

apparatuses, Foucault's in principle and Cusa's in practice, assume a model

that is based on or inspired by the same ideal: God's absolute and unlimited

sight. While the fixed eyes in the painting are the 'iconization' of the eyes of

the all-seeing God (or, to use Cusa's own words, the vision of God), the

archetypal form of the panopticon, whereby one observes without being

seen, is the incarnation of the divine eye. It is interesting that the epigraph to

Bentham's panoptic papers'3 comes from the Bible:

Thou art about my path, and about my bed:

and spiest out all my ways

If I say, peradventure the darkness shall cover me,

then shall my night be turned into day.

Even there also shall thy hand lead me;

and thy right hand shall hold me. '4-

Foucault himself was not unaware of the divine aspect behind the logic of

the Benthamite project. He draws a relationship between the omniscient

faceless gaze of the panoptic institution and the all-encompassing vision of

God. In Discipline and Punish, he asserts that the obsession with knowledge,

information and detail is an old practice: 'Detail has long been a category of

theology and asceticism: every detail is important since, in the sight of God,

no immensity is greater than a detail, nor is any thing so small that it was not

willed by one of his individual wishes. "5 With the change in the form and

purpose of punishment from one that aims at the body to one that targets

the soul, divine power, which has been inscribed in an 'architecture that

manifested might, the Sovereign, God,,6, is now invested in a gaze that

exercises invisible omnipresence. This divine archetype is also reenacted in

the forms of subjection that the individual undergoes - a belief not in an

apodictic truth, but in the existence of a reality one can never be sure of (or,

as de Certeau puts it, one that entails 'believing without seeing"7). The ways

94

MOHAMED ZAYANI

10- Michel Foucault, 'Prison talk', in Power/

Knowledge: Selected Interviews and Other Writings,

1972-1977, ed. and trans. Colin Gordon (New

York: Pantheon, Ig80), P.5I.

II - Martin Jay, 'In the empire of the gaze:

Foucault and the denigration of vision in

twentieth-century French thought', in

Foucault: A Critical Reader, ed. David Couzens

Hoy, (Oxford: Blackwell, 'g86), p. 176.

12- Michel Foucault, 'Eye of power', in

Power/Knowledge: Selected Interviews and Other

Writings, 1972-1977, ed. and trans. Colin

Gordon (New York: Pantheon, 'g80), p. 155.

13 - Jeramy Bentham, 'Panoptic papers', in A

Bentham Reader, ed. Mary Pack (New York:

Pegasus, Ig6g), pp. ,8g-208.

14- Psahn CXXXIX, XI, g6.

15 - Foucault, Discipliue aud Punish, p. '40.

16- Foucault, 'Eye of power', p. '48.

17- De Certeau, 'The Gaze', p. Ig.

18- Geoffrey Hartman, Wordsworth's Poetry:

1787-1814 (New Haven, CT: Yale University

Press, Ig64), p.8.

Downloaded by [Universite De Paris 1] at 13:34 30 August 2013

Ig- Hartman. Wordsworth's Poetry, pp. 8--g.

20 -

Foucault, Discipline and Punish, p. 20g,

231.

21 -

Foucault, Discipline and Punish, p. 200.

in which the onlooker responds to the all-seeing gaze of the face in the

painting and of the unlimited sight of God behind it and the ways in which

the prisoner in the panopticon reacts to the unverifiable presence of a

surveillant gaze work along lines that can best be summarized by a Miltonic

term that Geoffrey Hartman uses to describe Wordsworth's vision 'surmise.'18 It is a stance whereby the poet indulges in a kind of liberty and

expansiveness of spirit. Surmise, Hartman explains, 'likes "whether or"

formulations, alternatives rather than exclusions, echoing conjecture ...

rather than determinateness.'lg

Yet, although one can easily recognize in both visual apparatuses, the

mystic and the panoptic, elements of God's unlimited vision, these parallels

should be noted with caution. It is true that Bentham opens his panoptic

papers with a quotation from the Bible, but it is also a fact that he did not

design the panopticon; rather, he borrowed it from his brother. In the case

of Cusa, while the treatise is overtly concerned with the vision of God, this

vision is informed by the philosophical suppositions of the age in so far as it

proposes some continuity between the empirical and the spiritual world.

Cusa opens his treatise with the assertion that there is nothing which is

proper to the gaze of the icon of God that does not exist in the gaze of God.

The premise that underscores this assertion is as much rooted in Christian

theology as it is embedded in medieval scholasticism. It reenacts the neoPlatonic understanding of the world as an ossification between the Platonic

category of transcendence on the one hand - the opposition between the

world of appearances and the world of ideas, between phenomena and

noumena, between that which is visible and that which is invisible - and

the Aristotelian principle of development on the other hand - the

reconciliation between the sensible and the intelligible.

The resemblance between the Cusan and the panoptic gaze extends to

other features. In both instances, the omnivoyant gaze controls the subject's

space of action. Bentham's architectural apparatus is based on a simple

economic geometry that isolates inmates from the external world and makes

them invisible to each other. It conjures up the permanent axial visibility of

the central tower with a lateral invisibility that prevents individuals in their

cells from communicating with each other, thus securing discipline and

order. The panoptic gaze induces the individual to believe, while constandy

having before his or her eyes the tall outline of the central tower from which

he or she is spied on, that he or she is always observed without ever being

able to verify that. Out of Bentham's panopticon, Foucault posits a

paradigm to account for the dominant principles behind the operating

power relations in modem societies based on knowledge. This paradigm can

be schematically presented as: organization-invisibility/ observation-surveillance-control-discipline-order. Seen within the context of Foucault's theory

on the subject, panopticism summarizes the new codes that ensure the

capillary functioning of power - the substitution of 'discipline-mechanism'

for 'discipline-blockade.'20

The arrangement of a mechanism whereby one is the 'object of

information', never the 'subject in communication', 21 is not different from

Cusa's account of the spatial construction that generates the all-seeing gaze

in the picture. Michel de Certeau describes the Cusan gaze as a line and

95

action in space that always manipulates whoever looks at the painting. To

account for the Cusan optics, he distinguishes between two types of space,

that of the eye and that of the gaze. When the spectator's eyes look toward

the painting, the supposed object (the image) looks and finds the eyes, never

to leave them thereafter. The observing eyes are hypnotized, so to speak, by

the gaze, finding themselves with no will of their own. The curious gaze is

immediately turned into a cinderous gaze whereby the eyes are co-opted by

what is initially an inert object of observation:

Downloaded by [Universite De Paris 1] at 13:34 30 August 2013

The gaze that fixes him and follows him everywhere is for the supposed

spectator a question without an answer: What does it want of me, then? No

visible or imaginable object can be put in the place of that question .... The

gaze abolishes every position that would guarantee the traveler an acceptable

place, an autonomous and sheltering dwelling, an objective 'home.' The gaze

organizes the entire space. 22

For Cusa, as for Foucault, the gaze is alert and everywhere, omnipresent

and omnivoyant; it is inescapable and inviolable. In both models, visibility is

a trap. The underlying principle that brings Foucault's and Cusa's visual

apparatuses together is co-optation. The kind of co-optation the observer

experiences is the outcome of what, in another context, Wai-Chee Dimock

calls 'negative individualism'23 - one that produces individuals as subjects,

as figures whose very freedom of action already constitutes the ground for

discipline. In other words, what allows the observer to act as a free individual

also determines the course of his action. In both instances, the observer is at

the same time the bearer and the attribute of his own co-optation. In the

case of the panopticon, the space of co-optation is imposed on and enhanced

by individuals. The power that secures the operation of the panopticon is not

external to its machinery but immanent to it. Power, as Foucault explains, is

everywhere not because it enhances everything, but because it comes from

everywhere. Power is a matter of internal organization: 'In the peripheric

ring, one is totally seen, without ever seeing; in the central tower, one sees

everything without ever being seen.'24 The organization of space and the

arrangement of visibility which the individual is subjected to make him or

her the principle cause and the perpetrator of his or her own subjection such

that the individual is the one who perpetuates the exercise of power.

One expects, as Foucault does not fail to posit in the History if Sexualiry,

that 'where there is power there is resistance, and yet, or rather

consequently, this resistance is never in a position of exteriority in relation

to power.'25 In the case of the painting, there is no constantly visible single

point in front of one's eyes. Looking entails a loss of the object of

observation. There is no point de mire; instead, the center is everywhere and

nowhere. The point that the all-seeing gaze constitutes is 'a quasinothingness.'26 This space is created by the spectator. In his or her desire

to grasp the object of observation, to contain the perfection of the painting,

the observer positions himself or herself in relation to the gaze in a way that

he or she cannot escape; the gaze in the painting rivets the observer's

attention. While looking, the observer sees that he or she is being followed.

During this eye contact, the order of perception is reversed: 'Eyes do not

lead to the gaze. It is the gaze that may find the eyes.'27 The observer

becomes both the target and the instrument, the scene and the agent of his

96

MOHAMED ZAYANI

22- De Certeau, 'The

Gaze', p. 20.

23 - Wai-Chee Dimock, Empire for Liberty:

Melville and the Poetics if Individualism

(princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press,

1988), p. II2.

24-

Foucault, Discipline and Punish, p. 202.

25 - Michel Foucault, History if Sexuality: An

Introduction, trans. Robert Hurley (New York:

Vantage, 1980), P.95.

26 -

De Certeau, 'The Gaze', p. 14.

27- De Certeau,

'The Gaze', P.30.

Downloaded by [Universite De Paris 1] at 13:34 30 August 2013

28- De Certeau,

29 -

'The Gaze', p. 16.

Foucault, Discipline and Punish,

pp.216-

17

30 - Foucault, Discipline and Punish, p. 194.

31 93

Foucault, Discipline and Punish,

pp. 192-

or her own co-optation: 'The supposed object (the painting) looks, and the

subjects (the spectators) make up the tableau.'28

The similarities between Foucault's and Cusa's models, striking as they

may be, conceal fundamental differences, which make them more parallel

than similar. To start with, whereas in the panopticon power is exercised

through transparency, in the example of the painting subjection is

constructed around a spectacle. Foucault's optical model consciously rejects

the notion of the spectacle in favor of seamless surveillance and omniscient

invisibility. In a panoptic society, the need for the display of power is

minimal. What guarantees the operation and continuation of the panoptic

machine is not its outward manifestation but its internal organization:

'Antiquity had been the civilization of spectacle. To render accessible to a

multitude of men the inspection of a small number of objects: this was the

problem to which the architecture of temples, heaters and circuses

responded .... The modem age poses the opposite problem: To procure

for a small number, or even for a single individual, the instantaneous view of

a great multitude. . .. Our society is one not of spectacle, but of

surveillance .... We are neither in the amphitheater, nor on the stage, but

in the panoptic machine.'29 The panoptic machine is neither spectacular nor

theatrical. The excess of theatricality that has long characterized the old

regime is useless in a disciplinary society which exercises insulation and

surveillance. The Cusan optical model, however, is not one of contrivance

but of coincidence. It conjures up the notion of the spectacle and that of

surveillance. The all-seeing gaze is not only ubiquitous but always obverse.

The observer and the observed are brought together in a visible and overdetermined relationship. The eyes of the spectator and the gaze in the

picture meet but do not intersect: the former rakes and turns into a

tangential gaze, while the latter develops into a trammeling gaze.

It is all the more interesting to note that the distinction between a form of

subjection that is based on surveillance and one that is constructed around a

spectacle carries profound implications relating to individual identity.

Whereas the Foucaultian subject acquires certain individuality, the Cusan

observer suffers precisely a loss of individuality. While the overseeing gaze

reinforces one's individuality by reforming it, the all-seeing gaze obliterates

it. For Foucault, 'the individual is no doubt the fictitious atom of an

"ideological" representation of society; but he is also a reality fabricated by

this specific technology of power.'3 0 In a society of discipline, the subject is

never dissolved. The will to knowledge on which the panoptic institution

thrives does not dispense with the subject but continuously draws attention

to it. The great transformational years that ushered in the panopticon also

reversed the axis of individualization from an 'ascending' individualization,

which depends on the accumulation of power, to a 'descending'

individualization fostered by that very obfuscation of power. 31 In the

panoptic machine, the ensemble of individuals is replaced by a collection of

separated individualities. Surveillance means the dissociation of the

community and the isolation of the individual. What is lost in the process

is not the individuality of the subject, but the collective effect of

individualities. Although the observer is always subjugated to the supervision

97

Downloaded by [Universite De Paris 1] at 13:34 30 August 2013

of the powerful gaze and never oblivious to the fact that he or she is or can

be under constant observation, he or she never loses his or her individuality.

He or she is always insulated from his observer. The spatial organization of

the panopticon always creates and perpetuates a sizable distance between

the observer in the watch tower and the inmates in the cells. What

surveillance means, in Foucault's words, 'is not that the beautiful totality of

the individual is amputated, repressed, altered by our social order, it is

rather that the individual is carefully fabricated in it, according to a whole

technique of forces and bodies.'3 2

The Cusan gaze, however, reverses the relationship between the object

and the subject of observation. The reputed subject (the observer) is brought

in only to draw attention away from him or her, to the putative object - the

true Seer or 'le Vqyant veritable' as de Certeau put it. 33 The mutation of roles

between co-opted and co-optive entails a certain proximity and intimacy

between the observer and the observed, which persists throughout their

relationship. The onlooker can never claim a distance from the painting as

the two are interlaced. The more the observer tries to get out of the spell of

the insidious gaze, the more ensnared he or she becomes. As he or she looks,

the observer meshes into the object of observation. While both visual systems

are based on the negation of a resistant object, in the Cusan gaze the viewer

is converted into an object rather than a docile, knowable and controllable

individual as is the case in the Foucaultian model; in fact, the viewer

becomes an image - a qua-spectacle, so to speak. The observer in the

Cusan model remains insistendy immanent only as an object of observation.

The second significant difference between the panopticon and the allseeing gaze in the painting is that the former de-individualizes power, while

the latter disembodies it. This distinction is significant because it contains the

gist of Foucault's long and sustained work. Foucault's aim in his theoretical

project is not to analyze the phenomenon of power but to address the

question of the subject, i.e. the modes of objectification that transform

human beings into subjects. The efficacy of the panopticon is not contingent

on a specific person but rather depends on a relationship between the

observer and the observed. "'Power" in the substantive sense, "le JJ pouvoir,'

Foucault maintains in an interview, does not exist. 34 Power does not

designate a person, but a relationship. It is located in the internal

arrangement of this machinery and not in the individual who arranges it.

What is at stake is not 'the relations of sovereignty,' but 'the relations of

discipline.'35 The panopticon is not an individual but a machine in which

everyone is caught but none owns. The operating power relation that the

panoptic apparatus creates and sustains is independent of the person who

exercises it. The body of the king or the ruler is no longer needed; it is at the

opposite extreme of this 'new physics of power represented by panopticism.'3 6 Power, as Foucault proclaims, 'has its principle not in a person as in

a certain concerted distribution of bodies, surfaces, lights, gazes; in an

arrangement whose internal mechanisms produce the relation in which

individuals are caught up. '37 What this means, in part, is that the exercise of

power does not come from above but from within. Power relations are

deeply imbedded in the system of social networks. This interplay makes it

impossible to confine power in a designated and manageable Other, be it an

98

MOHAMED ZAYANI

32 - Foucault, Discipline and Punish, p. 217.

33 - De Certeau, 'The Gaze', p. 25.

34- Michel Foucault, 'The Confession of the

flesh', in Power/Knowledge: Selected Interviews

and Other Writings, I972-I977, ed. and trans.

Colin Gordon (New York: Pantheon, 1980),

P19 8 .

35 -

Foucault, Discipline and Punish, p. 208.

36- Foucault, Discipline and Punish, p. 208.

37- Foucault, Discipline and Punish, p.202.

Downloaded by [Universite De Paris 1] at 13:34 30 August 2013

38 - Michel Foucault, 'The Subject and

power', Critical Inquiry, 8/4 (1982), P.789.

39- De Certeau, 'The Gaze', p. 16.

40- De Certeau, 'The Gaze', P.9.

41 - Foucault, Discipline and Punish, p. 201.

42 - Foucault, 'Eye of power', p. 148.

43 - Foucault, Discipline and Punish, p.202.

44- Foucault, 'Eye of power', p. 148.

45 - Foucault, Discipline and Punish, p. 205.

46 - Foucault, Discipline and Punish, p. 202.

individual or an institution of power. The relations of power that

characterize our modern age do not involve confrontation. A mode of

action, in Foucault's words, 'does not act directly and immediately on others.

Instead, it acts upon their actions: an action upon an action. '38

In the example of the painting, however, one can see a movement and

eventually a reversal of positions between the emanating and emanated

gaze. During this mutation, the gaze of the viewer yields under the spell of

the increasingly forceful gaze of the painting, and eventually becomes

passive. Once the gaze finds the eyes of the spectator, the object of

observation is defaced and eventually effaced or better yet disembodied.

This is why the image of the all-seer in the painting is not an object, but

rather a supposed object, and the observer is only a pseudo-observer. By

looking, the observer has disqualified himself or herself from the role of the

perceiver. There is no longer a referent for whomever is being seen; it is lost

in the very theatricality it creates, giving way to a faceless gaze - a

contentless content, so to speak: 'the Cusan composition, by using a

painting, subtracts the body that would leave the spectator's eyes to

their movements and their hunts.'39 It effaces the body and retains only the

gaze.

The third and last distinction between the two optical systems is that the

spatial organization of the Cusan gaze is more abstract than that of the

panoptic gaze. One is a concept, the other is a practice or a category of

practices. While the former model is 'a "construction" of the mind'40 that is

exclusively geometrical, the latter is 'an architectural apparatus'41 that is

both mental and material; i.e. a system that relies on 'a disposition of

space.'42 In the case of Foucault, the genius and ingeniousness of the

panopticon consists of exercising power without resorting to force: 'a real

subject is born mechanically from a fictitious relation. '43 This fictitious

relation, however, is invested in 'a system of isolating visibility'44 that is

architectural in essence. The new technology of power requires a better

observation, a permanent visibility and a detailed control that involves an

internal reorganization of space and a calculation of its visibility. After all,

the panopticon is supposedly a building, which acts directly on individuals

through no instruments other than architecture and geometry: 'the

panopticon must not be understood as a dream building: it is the diagram

of a mechanism of power reduced to its ideal form; its functioning abstracted

from any obstacle, resistance or friction, must be represented as a pure

architectural and optical system: it is in fact a figure of optical technology

that may and must be detached from any specific use.'45 What characterizes

the panoptic institution is its very materiality as an instrument of power,

but what distinguishes it from other institutions is its lightness: 'the

heaviness of the old houses of security, with their fortress-like architecture,

could be replaced by the simple, economic geometry of a house of

certainty.'46 It should be stressed, however, that Foucault is not confined

by the architectural model of the panopticon. He acknowledges that the

panopticon is an ideal building for Bentham, but finds it first and

foremost a model for all sorts of modern forms of surveillance and

discipline whether honored in buildings or not. The panopticon is

polyvalent in its application. The principles that govern this architectural

99

Downloaded by [Universite De Paris 1] at 13:34 30 August 2013

apparatus of observation are not limited to reforming prisons, but can

serve as a model for schools, hospitals, factories and barracks, among other

applications.

The Cusan gaze is a good instance of the sort of power based on the

spectacle (in this case religious iconography) that Foucault contrasts to

modem disciplinary power. If in its application, as Foucault tells us, panoptic

power tends to be non-corporal, in the Cusan gaze it is literally noncorporal. The all-seeing gaze can even be said to be a-corporal. Although, in

the preface, the vision is initially exercised on a painting, this painting is

nothing more than what Sartre calls an 'alien addition.'47 The eye is

ultimately to be extracted from the corporal. In its pursuit of unmediated

knowledge, mysticism dispenses with the body. The kind of knowledge that

Nicholas of Cusa posits is made possible through an intellectual intuition.

Abstract as it may be, though, this intuition is not an epiphanic revelation or

a moment of ecstasy. It is of an order that is essentially mathematical. With

his principles of docta ignorantia, as Ernest Cassirer succincdy argues, Cusa

points out a tension between faith and knowledge. It is in this tension that

Cassirer locates Cusa's innovation: 'he requires of the symbols in which the

divine becomes graspable by us not only sensible fullness and force, but also

intellectual precision and certainty.'48 Knowledge is less a matter of intuition

than it is a matter of measurement. Underlying the Cusan gaze is the

application of geometrical principles to theology. For Cusa, geometry is both

a visual language - seeing with the eye - and a conceptual practice seeing with the mind. It is a science that applies abstract perception to visual

forms. The exercise of devotion that Cusa proposes converts a scientific

experiment into a spiritual quest - seeing the invisible in the visible; i.e.

seeing God in the icon of God.

The distinction between the non-corporality of the panopticon and the acorporality of the all-seeing gaze is further evinced in the difference in the

level of abstraction that governs and defines the very terms of subjection.

Rather than do away with the body, Foucault proposes an economy of the

body. The hold on the body is moderated, but not eliminated altogether: 'it

is always the body that is at issue - the body and its forces, their utility and

their docility, their distinction and their submission.'49 Although there is no

physical confrontation in the new disciplinary system, physicality is not

wanting from the panoptic institution. The modem penal system, Foucault

insists, is still physical. This physicality, however, does not abuse the body;

rather it manipulates it. The body is only the instrument of control, not its

ultimate object: 'Thanks to the techniques of surveillance, the physics of

power, the hold over the body, operate according to the laws of optics and

mechanics, according to a whole play of spaces, lines, screens, beams,

degrees and without recourse, in principle at least, to excess of force or

violence. It is a power that seems all the less corporal in that it is more subdy

physical. '50

In the case of Cusa, however, the revulsion from the corporal is more

complete. While in the panopticon power is generated through a machinery

that is material in essence, in the all-seeing gaze, power is based on an

elegant economy made all the more possible through what FredricJameson,

in a different critical register, calls 'fantasy bribe',5 1 and which is invested in

100

MOHAMED ZAYANI

47 - Jean Paul Sartre, Critique qf Dialectical

Reason: Theory qf Practical Ensembles, trans.

Alan Sheridan-Smith (London: Humanities

Press, 1976), p. 28.

48 - Ernest Cassirer, The Individual and the

Cosmos in Renaissance Philosophy, trans. Mario

Domandi (New York: Harper, 1963), P.53.

49 - Foucault, Discipline and Punish, p. 25.

50- Foucault, Discipline and Punish, p. '77.

5' - Frederic Jameson, 'Reification and

utopia in mass culture', Social Text, 1/r (1978),

PI44

Downloaded by [Universite De Paris 1] at 13:34 30 August 2013

52- De Certeau, 'The Gaze', p. II.

the observer's relationship to the rudimentary expression of the gazing face

in the painting. While in the panopticon, it should be remembered, the

inmate is prevented from coming into contact with his companions in the

adjacent cells, in the Cusan model communication between individuals is a

prerequisite for the efficacy of the gaze and the ratification of its latent

power. Communication is the ratifier of co-optation, so to speak. As he

meshes into his supposed object of observation, the ambulatory observer

requires another subject to confirm and thus realize that the gaze is

omnivoyant and omnipresent: 'He will be astonished that [the image] moves

immobilely and it is equally impossible to his imagination to grasp that the

same type of movement is produced with a brother who is walking in the

opposite direction. If he wants to make the experiment, he will arrange for a

brother to be going from east to west without taking his eyes off the image,

while he himself goes from west to east: he will question his partner to find

out whether the image continues to turn its sight on him too, and he will

learn from his ears that the gaze moves in the same manner in the opposite

direction; then he will believe it.'5 2 So as to be effective, the visual experience

of the observer has to be contrasted and constructed around the same secret.

Each point of view pursues its own logic, but in the name of what it believes

about the others. In order for experimenters to overcome their uncertainty

and comprehend the coincidence of at once all and each which characterizes

the Cusan gaze, they have to communicate. With the introduction of the

second observer, the subjection of the individual is complete. While trying to

challenge the visual authority of the gazing face by changing positions, the

observer literally surrenders himself or herself to its movement, thus

becoming someone of pliable disposition and the author of his or her own

co-optation. The observer simply cannot operate outside the constraints

imposed by the omnivoyant gaze.

In pointing out the differences between the two optical models, however,

one should not equate implication with application. While both visual

experiences can serve as illustrations of the concept and process of cooptation, each of these two models should be understood in its own register.

Although they have comparable frameworks, they have distinct applications.

While the all-seeing gaze is an exercise of faith that the monks have to

perform in order to realize the presence of God, the panopticon is a social

and economico-political project that seeks to reform and discipline society

by maximizing power and minimizing its cost. This difference in application

also entails a difference in the premises that underlie the Cusan and

Foucaultian disquisition on the category of the subject and the relation of the

subject to knowledge. While the German prelate claims that divine truth is

visible and that its accessibility is ultimately a question of an exercise or, as

he puts it, praxis, the French philosopher insists that the latent structure of

power is altogether invisible. For the former, knowledge of the true (i.e.

knowledge of God) can be seen in and inferred from the apparent (i.e. the

icon of God). For the latter, the exercise of power is never visible. The

subject is always a manageable subject because he or she is never cognizant

of his or her own co-optation. The practice of seeing that Cusa preaches

does not aim at seeing the visible, but at seeing the invisible in the visible.

The kind of visual apparatus Foucault invokes, however, does not seek to

101

Downloaded by [Universite De Paris 1] at 13:34 30 August 2013

reveal the invisible, but to show the extent to which the visibility of the

invisible is invisible. While for Nicholas of Cusa experiencing the fIxedness of

the gaze is a means of accessing truth and divine knowledge and thus an

instrument of illumination, for Foucault it is an experience whereby one

'ceaselessly under the eyes of an inspector [is] to lose the power and even

almost the idea of wrongdoing. '53 Whoever is subjected to the fIeld of

visibility is ultimately a source of knowledge, discipline, control and power.

While in the preface to his treatise Cusa strives to evince the transparency

and continual presence of God and the availability and benefIts of the

pursuit of mystic theology, in Discipline and Punish Foucault tries to account

for the invisibility of the techniques and organization of power in the

modern era and to explore the ways in which power in a disciplinary society

is exercised through its very invisibility.

102

MOHAMED ZAYANI

53- Foucault, 'Eye of power', p. 154.

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5822)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1093)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (852)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (898)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (540)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (349)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (822)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (403)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Mercruiser Service Manual #14 Alpha I Gen II Outdrives 1991-NewerDocument715 pagesMercruiser Service Manual #14 Alpha I Gen II Outdrives 1991-NewerM5Melo100% (10)

- The Dated Alexander Coinage of Sidon and Ake (1916)Document124 pagesThe Dated Alexander Coinage of Sidon and Ake (1916)Georgian IonNo ratings yet

- Glitsos - 'Vaporwave, or Music Optimised For Abandoned Malls'Document19 pagesGlitsos - 'Vaporwave, or Music Optimised For Abandoned Malls'Kam Ho M. WongNo ratings yet

- Winge - 'Costuming The Imagination Origins of Anime and Manga Cosplay'Document13 pagesWinge - 'Costuming The Imagination Origins of Anime and Manga Cosplay'Kam Ho M. WongNo ratings yet

- Roviello - 'The Hidden Violence of Totalitarianism'Document9 pagesRoviello - 'The Hidden Violence of Totalitarianism'Kam Ho M. WongNo ratings yet

- Darley - 'Does Aquinas' Notion of Analogy Violate The Law of Non-Contradiction'Document10 pagesDarley - 'Does Aquinas' Notion of Analogy Violate The Law of Non-Contradiction'Kam Ho M. WongNo ratings yet

- Priest - 'Was Marx A Dialetheist'Document9 pagesPriest - 'Was Marx A Dialetheist'Kam Ho M. WongNo ratings yet

- Yu - 'Confucius' Relational Self and Aristotle's Political Animal'Document21 pagesYu - 'Confucius' Relational Self and Aristotle's Political Animal'Kam Ho M. WongNo ratings yet

- Colletta - 'Political Satire and Postmodern Irony in The Age of Stephen Colbert and Jon Stewart'Document20 pagesColletta - 'Political Satire and Postmodern Irony in The Age of Stephen Colbert and Jon Stewart'Kam Ho M. Wong100% (1)

- Bennett - 'Hermetic Histories'Document37 pagesBennett - 'Hermetic Histories'Kam Ho M. WongNo ratings yet

- Piper - 'Skeptical Theism and The Problem of Moral Aporia' PDFDocument15 pagesPiper - 'Skeptical Theism and The Problem of Moral Aporia' PDFKam Ho M. WongNo ratings yet

- Understanding Psychology Chapter 1Document3 pagesUnderstanding Psychology Chapter 1Mohammad MoosaNo ratings yet

- Strategies For Weak & Crisis Ridden BusinessesDocument13 pagesStrategies For Weak & Crisis Ridden BusinessesApoorwa100% (1)

- Pertemuan 2 - EXERCISES Entity Relationship ModelingDocument10 pagesPertemuan 2 - EXERCISES Entity Relationship Modelingjensen wangNo ratings yet

- UntitledDocument1 pageUntitledГаврило ПринципNo ratings yet

- Aluda Move (Rayan Nadr J Zahra Ozair)Document2 pagesAluda Move (Rayan Nadr J Zahra Ozair)varaxoshnaw36No ratings yet

- Effect of Oral Cryotherapy in Preventing Chemotherapy Induced Oral Stomatitis Among Childhood Acute Lymphoblastic LeukemiaDocument10 pagesEffect of Oral Cryotherapy in Preventing Chemotherapy Induced Oral Stomatitis Among Childhood Acute Lymphoblastic LeukemiaIjahss JournalNo ratings yet

- Dinagat HVADocument55 pagesDinagat HVARolly Balagon CaballeroNo ratings yet

- Shezan Project Marketing 2009Document16 pagesShezan Project Marketing 2009Humayun100% (3)

- Systematix Sona BLW Initiates CoverageDocument32 pagesSystematix Sona BLW Initiates Coveragejitendra76No ratings yet

- Occasional Paper 2 ICRCDocument82 pagesOccasional Paper 2 ICRCNino DunduaNo ratings yet

- Business Law Cpa Board Exam Lecture Notes: I. (CO, NO)Document27 pagesBusiness Law Cpa Board Exam Lecture Notes: I. (CO, NO)Shin MelodyNo ratings yet

- Collection of Windows 10 Hidden Secret Registry TweaksDocument9 pagesCollection of Windows 10 Hidden Secret Registry TweaksLiyoNo ratings yet

- Ahnan-Winarno Et Al. (2020) Tempeh - A Semicentennial ReviewDocument52 pagesAhnan-Winarno Et Al. (2020) Tempeh - A Semicentennial ReviewTahir AliNo ratings yet

- Nod 321Document12 pagesNod 321PabloAyreCondoriNo ratings yet

- The Role of The School Psychologist in The Inclusive EducationDocument20 pagesThe Role of The School Psychologist in The Inclusive EducationCortés PameliNo ratings yet

- FRANKL, CROSSLEY, 2000, Gothic Architecture IDocument264 pagesFRANKL, CROSSLEY, 2000, Gothic Architecture IGurunadham MuvvaNo ratings yet

- Dg-1 (Remote Radiator) Above Control Room Slab: 05-MAR-2018 Atluri Mohan Krishna (B845)Document32 pagesDg-1 (Remote Radiator) Above Control Room Slab: 05-MAR-2018 Atluri Mohan Krishna (B845)Shaik AbdullaNo ratings yet

- GRADE 8 NotesDocument5 pagesGRADE 8 NotesIya Sicat PatanoNo ratings yet

- Create BAPI TutorialDocument28 pagesCreate BAPI TutorialRoberto Trejos GonzalezNo ratings yet

- Form LRA 42Document3 pagesForm LRA 42Godfrey ochieng modiNo ratings yet

- Asuhan Keperawatan Pada Klien Dengan Pasca Operasi Hernia Inguinalis Di Lt.6 Darmawan Rs Kepresidenan Rspad Gatot Soebroto Jakarta Tahun 2019Document7 pagesAsuhan Keperawatan Pada Klien Dengan Pasca Operasi Hernia Inguinalis Di Lt.6 Darmawan Rs Kepresidenan Rspad Gatot Soebroto Jakarta Tahun 2019Ggp Kristus Raja SuliNo ratings yet

- Marketable Avenues: 14,15,16 April 2023Document31 pagesMarketable Avenues: 14,15,16 April 2023Avaneesh Natraj GujranNo ratings yet

- Strategicmanagement Case StudiesDocument62 pagesStrategicmanagement Case StudiesElmarie Versaga DesuyoNo ratings yet

- Davis Michael 1A Resume 1Document1 pageDavis Michael 1A Resume 1Alyssa HowellNo ratings yet

- Public Administration - Meaning & Evolution - NotesDocument5 pagesPublic Administration - Meaning & Evolution - NotesSweet tripathiNo ratings yet

- CH 3 Online Advertising vs. Offline AdvertisingDocument4 pagesCH 3 Online Advertising vs. Offline AdvertisingKRANTINo ratings yet

- Final Defense in PR2Document53 pagesFinal Defense in PR2Friza ann marie NiduazaNo ratings yet

- Ip Talks Presentation - Keaune ReevesDocument2 pagesIp Talks Presentation - Keaune Reeveskarina talledoNo ratings yet