Professional Documents

Culture Documents

The End of Jim Morrison

The End of Jim Morrison

Uploaded by

Andrius LedasCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- Sun RA - Myth, Music & MediaDocument5 pagesSun RA - Myth, Music & MediashekereafricaNo ratings yet

- Hypertension in Pregnancy ACOG 2013Document10 pagesHypertension in Pregnancy ACOG 2013lcmurillo100% (1)

- Preopanc Trial - PancreasDocument20 pagesPreopanc Trial - PancreasRajalakshmi RadhakrishnanNo ratings yet

- Jim Morrison - "The Lords"Document18 pagesJim Morrison - "The Lords"Harsh ChoudharyNo ratings yet

- The History of The Brazilian Black Metal SceneDocument9 pagesThe History of The Brazilian Black Metal SceneThornsNo ratings yet

- Aunt Pat EditDocument7 pagesAunt Pat EditDave56No ratings yet

- Henry Flynt Selected WritingsDocument274 pagesHenry Flynt Selected WritingsVictor CironeNo ratings yet

- GLP Vs 17025Document6 pagesGLP Vs 17025Nadhra HaligNo ratings yet

- Chapter 3 Research Methodology This Chapter ContainsDocument15 pagesChapter 3 Research Methodology This Chapter Containspatchu141594% (52)

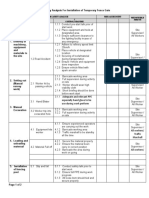

- ULSADO-JSA - Installation of Temporary Fence GateDocument2 pagesULSADO-JSA - Installation of Temporary Fence GateKelvin TanNo ratings yet

- Chaos To Creation The Enigma of Bob Dylan (Part 3)Document7 pagesChaos To Creation The Enigma of Bob Dylan (Part 3)Susanta BhattacharyyaNo ratings yet

- Dreadlock Rec.Document165 pagesDreadlock Rec.BjornGayNo ratings yet

- Jim Morrison Top 10 Commandments 0607Document26 pagesJim Morrison Top 10 Commandments 0607David Shiang100% (2)

- The Lizard KingDocument8 pagesThe Lizard KingGabriel MisifusNo ratings yet

- Lionel Ziprin - FriezeDocument6 pagesLionel Ziprin - FriezeScott MartinNo ratings yet

- LoreoftheMagi PDFDocument43 pagesLoreoftheMagi PDFciejhae3111No ratings yet

- Twin Peaks - The Return (101 My Log Has A Message For You)Document59 pagesTwin Peaks - The Return (101 My Log Has A Message For You)Janine LeanoNo ratings yet

- Lucifer v03 n14 October 1888Document88 pagesLucifer v03 n14 October 1888lisNo ratings yet

- Sundari Testimonial 1 - Lynn MichaelianDocument3 pagesSundari Testimonial 1 - Lynn MichaelianDigital CitizensNo ratings yet

- MetallicaDocument32 pagesMetallicaÓscar Soto-GuaderramaNo ratings yet

- Reed - Let's Make Love Before You Die "Warm Leatherette," Boredom and The Invention of The 1980sDocument8 pagesReed - Let's Make Love Before You Die "Warm Leatherette," Boredom and The Invention of The 1980sthoushaltnot100% (1)

- Kut V ChaosDocument96 pagesKut V ChaosMark FrazzettoNo ratings yet

- In His Own Write and A Spaniard in the WorksFrom EverandIn His Own Write and A Spaniard in the WorksRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (144)

- Sara Dylan & The Rise of The Anti-Zen in Seventies Bob: How Weak Was The FoundationDocument9 pagesSara Dylan & The Rise of The Anti-Zen in Seventies Bob: How Weak Was The Foundation'Messianic' DylanologistNo ratings yet

- Desire and Crisis - The Operation of Cinematic Masks in Stanley Kubrick's Eyes Wide ShutDocument13 pagesDesire and Crisis - The Operation of Cinematic Masks in Stanley Kubrick's Eyes Wide ShutgeorgefeickNo ratings yet

- Nine Inch Nails - The Prodigy Posts (November 1992)Document13 pagesNine Inch Nails - The Prodigy Posts (November 1992)SelfCloakNo ratings yet

- 6.30.11 BeatlesBible - Com Working Class MysticDocument3 pages6.30.11 BeatlesBible - Com Working Class MysticQuestBooks100% (1)

- Lou Reed's ObituaryDocument3 pagesLou Reed's ObituaryNoé LopesNo ratings yet

- A Burzum Story Eng PDFDocument23 pagesA Burzum Story Eng PDFJoseLafuentedeAraujo0% (1)

- Eutopia Poul Anderson PDFDocument2 pagesEutopia Poul Anderson PDFMoniqueNo ratings yet

- Hotter Than a Match Head: My Life on the Run with The Lovin’ SpoonfulFrom EverandHotter Than a Match Head: My Life on the Run with The Lovin’ SpoonfulRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (4)

- The Candy Men: The Rollicking Life and Times of the Notorious Novel CandyFrom EverandThe Candy Men: The Rollicking Life and Times of the Notorious Novel CandyNo ratings yet

- Metaclysmia DiscordiaDocument30 pagesMetaclysmia DiscordiaJason CullenNo ratings yet

- Concerto For Magic and Mysticism - Esotericism and Western MusicDocument9 pagesConcerto For Magic and Mysticism - Esotericism and Western Musicbde_gnasNo ratings yet

- The Velvet Underground The Black Angel's Death Song Mirrors Bob Dylan CareerDocument4 pagesThe Velvet Underground The Black Angel's Death Song Mirrors Bob Dylan CareerAlan Jules WebermanNo ratings yet

- Excerpt From "The Friedkin Connection: A Memoir" by William Friedkin. Copyright 2013 by William Friedkin. Reprinted Here by Permission of Harper. All Rights Reserved.Document5 pagesExcerpt From "The Friedkin Connection: A Memoir" by William Friedkin. Copyright 2013 by William Friedkin. Reprinted Here by Permission of Harper. All Rights Reserved.wamu8850No ratings yet

- Stephen Doty June 2019 On The Writing Style of Bob DylanDocument7 pagesStephen Doty June 2019 On The Writing Style of Bob DylanSpaner_os100% (1)

- Stone GodfatherIIDocument9 pagesStone GodfatherIIM MaliNo ratings yet

- List of Fairy TalesDocument11 pagesList of Fairy TalesLara HunterNo ratings yet

- GREBO!: The Loud & Lousy Story of Gaye Bykers On Acid and CrazyheadFrom EverandGREBO!: The Loud & Lousy Story of Gaye Bykers On Acid and CrazyheadNo ratings yet

- Top 100 Psychedelic SongsDocument2 pagesTop 100 Psychedelic SongsGii Selle100% (1)

- Decibel Coverstory Typeo 0407 150Document4 pagesDecibel Coverstory Typeo 0407 150Kit Traverse100% (1)

- By Karen Mutton © 2005: Email: WebsiteDocument7 pagesBy Karen Mutton © 2005: Email: WebsiteAMITH OKNo ratings yet

- The Complete Ourang-Outang by de Villo SloanDocument127 pagesThe Complete Ourang-Outang by de Villo SloanMinXusLynxusNo ratings yet

- CPR Salbutamol+Ipratropium Neb (BRODIX PLUS) 35'sDocument2 pagesCPR Salbutamol+Ipratropium Neb (BRODIX PLUS) 35'sRacquel SolivenNo ratings yet

- Characteristic of NewbornDocument9 pagesCharacteristic of Newbornbabyrainbow100% (15)

- Effect of Applying Therapeutic Architecture On The Healing of Drug AddictsDocument8 pagesEffect of Applying Therapeutic Architecture On The Healing of Drug AddictsRiya BansalNo ratings yet

- Unheard Voices of Mothers With Sexually Abused Children: A Multiple Case StudyDocument18 pagesUnheard Voices of Mothers With Sexually Abused Children: A Multiple Case StudyPsychology and Education: A Multidisciplinary JournalNo ratings yet

- Hps User Guide Hps6Document339 pagesHps User Guide Hps6Mostafa FayadNo ratings yet

- Discussion: Part 1: Nurse's Knowledge Toward MRSADocument1 pageDiscussion: Part 1: Nurse's Knowledge Toward MRSAMustafa KhudhairNo ratings yet

- Moderna Launches Vaccine Trials To Tackle New Coronavirus StrainDocument26 pagesModerna Launches Vaccine Trials To Tackle New Coronavirus Strainhttp://lamparinna.blogspot.comNo ratings yet

- ECardDocument1 pageECardBasanNo ratings yet

- U07a1 - Jasmone RigginsDocument5 pagesU07a1 - Jasmone RigginsjasmonerNo ratings yet

- Analisa Risiko Kecelakaan Kerja Pada Proyek Konstruksi Jembatan Musi Vi PalembangDocument6 pagesAnalisa Risiko Kecelakaan Kerja Pada Proyek Konstruksi Jembatan Musi Vi PalembangRoraNo ratings yet

- 0610 - s17 - QP - 42 AnsweredDocument20 pages0610 - s17 - QP - 42 Answered-Bleh- WalkerNo ratings yet

- Vaccines 10 00472Document17 pagesVaccines 10 00472IdmNo ratings yet

- Novel AUD Likelihood Detection Based On EEG ClassificationDocument5 pagesNovel AUD Likelihood Detection Based On EEG ClassificationsupravaNo ratings yet

- Pediatric Community Acquired PneumoniaDocument24 pagesPediatric Community Acquired PneumoniaJames Lagamayo JavierNo ratings yet

- 2020 Tanzania in FiguresDocument110 pages2020 Tanzania in FiguresDaveNo ratings yet

- Alternate Rapid Maxillary Expansion and Constriction (Alt-RAMEC) Protocol: A Comprehensive Literature ReviewDocument5 pagesAlternate Rapid Maxillary Expansion and Constriction (Alt-RAMEC) Protocol: A Comprehensive Literature ReviewGaby Cotrina LiñanNo ratings yet

- Assessment of Substance Abuse Among Adolescents in India: An OverviewDocument6 pagesAssessment of Substance Abuse Among Adolescents in India: An OverviewInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNo ratings yet

- MorbiliDocument30 pagesMorbiliMjNo ratings yet

- CAPE Communication Studies 2009 P3BDocument4 pagesCAPE Communication Studies 2009 P3BRiaz JokanNo ratings yet

- 613bd813608b5 - c350 - Carolyn - Cross - Docx 5Document8 pages613bd813608b5 - c350 - Carolyn - Cross - Docx 5t.bowdleNo ratings yet

- MedDRA Coding Basics WebinarDocument39 pagesMedDRA Coding Basics WebinarCosmina Georgiana100% (1)

- ISMT 12 - Day 402 - Rita - Posterior Cervical Laminectomy and Fusion Surgery C3-C7Document21 pagesISMT 12 - Day 402 - Rita - Posterior Cervical Laminectomy and Fusion Surgery C3-C7Vito MasagusNo ratings yet

- Kamilya Jamel Baljon, Muhammad Hibatullah Romli, Adibah Hanim Ismail, Lee Khuan, Boon How ChewDocument13 pagesKamilya Jamel Baljon, Muhammad Hibatullah Romli, Adibah Hanim Ismail, Lee Khuan, Boon How ChewOva Tri Pra Setia MayasarieNo ratings yet

- Guideline Management Crushing and Screening Feb10 1Document10 pagesGuideline Management Crushing and Screening Feb10 1Karin AndersonNo ratings yet

- Abdominal Acupuncture For DepressionDocument35 pagesAbdominal Acupuncture For DepressionAGNESE YOLOTZIN OLIVERA TORO REYESNo ratings yet

The End of Jim Morrison

The End of Jim Morrison

Uploaded by

Andrius LedasCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

The End of Jim Morrison

The End of Jim Morrison

Uploaded by

Andrius LedasCopyright:

Available Formats

PSYCHOTHERAPY: THEORY, RESEARCH AND PRACTICE

VOLUME 14, #4, WINTER, 1977

THE END OF JIM MORRISON: A SCHIZOID SUICIDEA PHENOMENOLOGICAL

STUDY IN OBJECT-RELATIONS

WARREN P. HOPKINS

HAROLD J. FINE

University of Tennessee

Knoxville, Tennessee

University of Richmond

Richmond, Virginia

ABSTRACT: Reviewing the circumstances surround- singer-idols: Jim Morrison, lead-singer of "The

ing the death of pop singer Jim Morrison, the authors Doors", a famous Los Angeles rock group. His

have come to believe not only that his end was death by "natural" causes, as "official" reeffected through suicide, but also that his death was a ports have it, appeared suspect. Moreover,

compelling instance of the schizoid-type suicide de- there exists compelling evidence that a

scribed by Harry Guntrip. Guntrip wrote that the

schizoid-type suicide is more congruent with his

schizoid problemthe persistence through life of a

untimely

death than is a heart attack. Certain

weak infantile ego characterized by anxiety and fear

and caused by inadequate mothering lay deeper in features of his life style, poetry, personal statethe strata of the unconscious mind than the oedipal ments, and friends' observations argue a strong

conflict. Sure enough, Morrison wrote and spoke case for a suicide interpretation. Objectblatantly and wittingly on the subject of his lust for relations theory not only affords insights into

his mother and hate for his father. Despite his Morrison's life, and attributes a certain logic to

consciousness of his oedipal conflict, his schizoid ego his death, but it also seems to have spoken very

weakness festered in him out of his control. This was personally to Morrison as well, for as will soon

evinced in his needs, apparent in both his lyrics and be obvious, he was not unfamiliar himself with

his actions, to lash out at but also escape from the the literature.

outer world. Indeed, many of the details of his

Object-relations theory is probably the most

personal lifehis relationship with his girlfriend,

his fantasies of escape through death and sex, and trenchant development within ego Psychology

finally his death itselfseem to conform to Gun- in recent times (Kernberg, 1972; Stein, 1969).

trip's portrait of the schizoid personality. Morrison s Beginning with Melanie Klein's studies of insuicide, then, was not the final manifestation of the ternalized objects in early infancy (Klein,

inverted, destructive anger found in the depressed 1932), and followed by Fairbairn (1952) and

individual, but rather an expression of the wish to be Winnicott (1958, 1965), the body of clinical

removed to a calmer realm.

Those who have crossed

With direct eyes, to death's other Kingdom

Remember us if at all not as lost

Violent souls, but only

As the hollow men

The stuffed men.

T. S. Eliot

"The Hollow Men"

Being recently enriched by the new insights

of psychoanalytically-derived object-relations

theory, one could not help but be fascinated by

a piece of sensational, though well-researched,

journalism (Wolfe, 1971) exploring the provocative death of one of the "pop" culture's

and theoretical studies relevant to the area

emerges for synthesis and integration. This

challenge was met with considerable success by

Harry Guntrip (1961, 1969, 1971). Guntrip's

contributions to object-relations theory, especially, have not only broadened the spectrum of

ego theory applications and technique, but also

opened the road to a newer understanding of

early normal and pathological development of

the person. More specifically, he has applied

this integrated object-relations theory to the

intensive, long-term treatment of schizoid personalities. And it is against this background that

the case of Jim Morrison bears particular relevance.

Six days after his death, official Paris police

423

424

H. J. FINE & W. P. HOPKINS

reports confirmed the original information: Jim

Morrison died of a heart attack while taking a

bath on July 3, 1971. At age 27, Morrison was

the most flamboyant but least open of "The

Doors", and as lead-singer, lyricist, and poet,

he came to be the symbol for the group. And for

many youth, he represented the crest of another

wave of rock groups. He was riding high; there

was even speculation that he was coming to be

the most potent sex symbol in our "pop"

culture since James Dean and Elvis Presley. His

song "Light My Fire" quickly sold two million

records. And others like "Break On Through,"

"Back Door Man," and most significantly

"The End," had similarly become anthems for

a generation of kids turning inward and away.

In "L.A. Woman" the line "I've been down so

goddamned long that it seems like up to me"

spells out the enjoyment of despair and emptiness.

Sexuality was Morrison's trademark; and it

was an unusual perspective on sex he touted:

sex-death, and a "thing" for oedipality. Even

beyond his lyrics, he was frequently observed to

cup his hands tightly over his genitals while

singing (holding on for dear life?), and once, at

a now famous Miami concert, he exposed

himself to his audience on stage. Morrison's

comment about this incident is just as revealing,

too.

"It's very, very hard to just get up on stage and sing a

song when you're a sex symbol. They didn't come to

hear my mouth; they were all ogling at my pants. The

way they refuse to grant your mouth when they've been

taught you're all below the waist is very frustrating for a

poet. You come forth with your fine words and they keep

on staring at your pants. I decided for once to give them

what'they were in the market for . . ." (Wolfe, p. 186)

The expression of such impotent rage through

genital aggression is not foreign to the psychiatric literature, nor for that matter to the public

place, but what is rare in this case is the

lip-service he pays to this rage on a conscious

level. To wit his celebrated song "The End,"

where parent-killing and parent-mauling are the

central themes. As one of his most emotional

offerings, it is a wild outburst of oedipal passions: pop is mowed down and mom taken over.

Its performance in concert is sensuously described by Wolfe:

"He explains to his 'beautiful friend', his 'only friend',

that this is 'the end of our elaborate plans.' He encourages her to 'ride the snake, to the lake, the ancient lake,'

the reptile being defined as 'seven miles long', 'old,'

'cold.' His growly baritone is almost sweet, almost

down to a love whisper, as he laments (or crows?) that

'I'll never look into your eyes again'; but there's the

rasping edge even when pitched low, the suggestion of a

snarl held back, the mixture of Arctic distance and muted

parody. At the mother's bedroom door, music having

left him altogether (by this time he's visited pop's room

and unceremoniously, with some melody still lingering,

wiped him out), he falls into a toneless, grinding

dirge-slack recitative. On the verge of the ghastly ellipsis, the point at which words as well as music cave in,

his eyes clamp shut, his lips form the unspeakable

syllables, 'I wa-a-a-ant'he screams." (p. 182)

Now, Freud's early assumption held that of

all the layers of the unconscious, the layer of the

oedipal material was the deepest and most

energetically repressed. This position had remained essentially unchallenged until the advent of object relations, and particularly Guntrip's conviction (1969, p. 36) that the oedipal

layer is not as deeply embedded as the schizoid

problem. Already, though, more contemporary

psychoanalysts had seen theoretical problems

arising when, for example, Stendahl in his

autobiographical novel, The Life of Henry

Brulard, dwelled openly and elaborately on

patricidal attitudes toward the father and incestuous urges toward the mother. This circumstance, of course, is also true in "The

End."

How are such phenomena to be reconciled

with traditional psychoanalytic theory? How do

these guilt-laden secrets come to the conscious

surface? Even Morrison's own lyrics make it

clear that he abides the traditional Freudian

position regarding incest as the most awful of

transgressions. How then would he explain

bellowing this straightforward confession in

public? The lengthy quote that follows obtains

from an interview (Wolfe, 1971) in which

Morrison replies to just this question; however,

Wolfe additionaly intimated that this oedipal

display could perhaps be a "smoke screen" to

cover something even more unspeakable. Morrison's quote here is reproduced in its entirety as

a tour de force of what Guntrip (1969, p. 178)

has referred to as "The Basic Emotional Predicament."

"I know what you're working up to. The new orality

stuff. I've read some of Melanie Klein and the others.

The idea that the Oedipal layer isn't as deep as people

used to think, that it gets deposited when the kid goes

into the genital period and a whole lot of stuff has come

together in his head before this, below it, when he was

THE END OF JIM MORRISON

all mouth, and no muscle or genitals. I know the whole

line of thought, man. That there was just oral passive

helplessness and bawling for Big Ma before the kid

began to grow muscles and came to see his genitals as

muscle, and could counter his ache for Ma's shelter with

a little genital aggression, at least in his fantasies. Deny

yearning mouth with blustering phallus. I know this

there's a whiny toddler inside every growling rapist

school.

Sure. By this reasoning it's easy to make a big red

badge of your Oedipality and wear it on your sleeve. It's

closer to the surface and you can dredge it out a lot faster

than the worse Ma-cuddly stuff under it. Use the one to

hide the other . . . Cop out to the Oedipal sin because

it's nowhere as bad as the oral ones that lie deeper. The

crimes of the sucking babe wanting to hold tight to

Mama and go on sucking forever, and feeling abandoned

by the old biddy because first she ejected him, then

shoved him aside, cut him off. Anybody'd rather own up

to fantasy crimes of muscle than those of the blobby and

flabby . . ." (p. 184)

It is hard to conceive of a more vernacular,

yet accurate, statement of the basic schizoid

dilemma. Even a studious reading of Schizoid

Phenomena, Object Relations, and the Self

(Guntrip, 1969) does not communicate so succinctly the qualitative nature of the schizoid

experience. The essence of the statement bears

repeating just once more: being aggressive and

bad (guilty) is not as unbearable to accept as

being frightened and weak (dependent).

Both phenomenologically and chronologically, the whole schizoid problem antedates the

oedipal development. Fairbairn (1952) thus regarded infantile dependence, not the Oedipus

complex, as the fundamental cause of

psychopathology. The schizoid person at bottom feels overwhelmed by the external world,

his weak infantile ego withdrawing in fear. This

state is "basic ego-weakness," though it is

often camouflaged by a false "exterior self".

The fear (and withdrawal) is primarily due to

the inability of weak infantile ego to cope with

external reality, having earlier been deprived of

adequate maternal support. And it is a consequence of this real deprivation that the ego

further experiences a hostile impulse to aggressively strike back at the rejective outer world.

One "hears" the resentment in Morrison's

words when he expresses these very feelings:

"Booze is mother's milk to me, and better than

any milk that ever came from my mother."

These psychodynamics convincingly explain

not only Morrison's aggressive exhibitionism in

public, but also the defensive posture he adopts

with regard to infantile dependence ("the new

425

orality stuff"), especially when he is so "wise

to it." Guntrip (1969, p. 129) has warned that

patients can "use" their conflicts over sex,

aggression, and guilt (". . . and their Freudian

inner world of oedipal conflicts . . .") as a last

resort defense against withdrawal, regression,

and depersonalization, even though the conflicts

may have their own obvious significance on

their own specific level.

This problem of basic ego-weakness was

more apparent, not unexpectedly, in Morrison's

private life than in his public image or poetry.

Morrison had once reflected "that when you're

going on two, everything looks old and big as

hell and feels pretty chilly; you're the one

scared!" People who knew him well, and were

skeptical about the "natural" death, contributed these opinions about his apparently increasing decompensation: " . . . The Jim I

knew had a king-size block as a writer; for him

to get off even a few lines a week might look

like a burst of activity close up . . . " " . . .

During the last two years in L.A., he was

alarmingly lazy, passive, sodden, lumpish, inert, and getting more so all the time . . ." ". . .

I knew him too well to believe there'd been a

sudden surge of life-affirming in him . . . "

On a more intimate level, his love relationships were at an impasse. The "in and out

programme" Guntrip (1969, p. 27) describes as

problematic for the schizoid is well represented

in Morrison's case by the report that in his

relationship with his girlfriend cum-wife "he

kept up his old on-again/off-again style of

living: one apartment with her, one without

. . . " This kind of interpersonal oscillation, so

diagnostic of schizoid conditions, reflects the

need for but fear of close relationshipsalways

needing love but a dread of being tied, rushing

into a relationship for security and urgently

breaking out again for freedom and independence. The central feature of the schizoid personality is the inability to effect personal relationships because of a radical immaturity of the

ego; there exists a complex inhibition of the

capacity to love and be loved.

And on a yet more intimate level, we glimpse

the nature of Morrison's sexual behavior and

experience through the disclosure of a previous

"lover" (Wolfe, 1971). She claims that he was

"mostly impotent, often taking hours," sometimes giving up. And besides the sadomasochistic games he enjoyed (talking dirty to

426

H. J. F I N E & W. P. HOPKINS

her, spanking her, telling her what a bad girl she

was "it excited him"), he would blame her

for his sexual failures, occassionally getting

violent enough to leave bruises after beating and

choking her. She recognized in Morrison the

brute and the baby, co-existing: . . . "a lot of

roughing up, then the sudden collapse, whimpering, 'I need someone to love me, please take

care of me, please don't leave me . . . ' "

Guntrip (1968, p. 153) has challenged the

notion that the deepest roots of psychopathology are sexual and/or aggressive instincts;

rather, as Morrison displays here, they are

secondary to the elements of fear, anxiety, and

flight. These instincts operate in disturbed ways

only in the fear-ridden person as a means of

overcoming devitalization and passivity. Oscillating between fight and flight, the schizoid

manifests outbursts of sexual and aggressive

behavior that function as a manic defensea

frantic attempt to fend off devitalized passivity.

Morrison's "lover" recalled a line of his

poetry: " . . . we seek to break the spell of

passivity with actions cruel and awkward . . . "

Her final remark was, "Kids will remember

him as tough, brutal, bestial, savage. The image

I keep is a different one."

tiredness" caused by the unremitting struggle to

avoid collapse is frequently experienced as a

wish to die. But it exists as an "unrealistic"

conception, for it contains elements of escape to

something else, rather than finality of existence.

To stop living but not wishing to die. The

schizoid suicide is encountered in the very

regressed ego, where the person has utterly lost

hope of being understood and helped. The

longing to die represents the schizoid need to

withdraw the ego from the world that is too

much for it to cope with. From a published

collection of Morrison's poems and notes

(1971) comes this piece: " . . . The theory is

that birth is prompted by the child's desire to

leave the womb. But in the photograph an

unborn horse's neck strains inward with legs

scooped out. From this everything follows:

Swallow milk at the breast until there's no

milk . . . "

Whereas the depressive suicide suggests a

hostile and destructive impulse turned inward

against the self, the schizoid suicide is the

end-product of apathy toward a life that can no

longer be accepted. What is desired is not a

destructive non-existence, but an escape into

warmth, quiet, comfort, a Nirvanaa return to

Jim Morrison was quite obviously a desperate the womb. Did the official report say "while

and despairing young man, and nowhere is this taking a bath?"

reflected more poignantly than in his poetry. He

This is the way the world ends

often adopted the poetic posture of being-onThis is the way the world ends

the-outside looking innot uncharacteristic of

This is the way the world ends

the schizoid condition. These persons often

Not with a bang, but a whimper.

refer to their experience of feeling withdrawn

T. S. Eliot

and cut off from outer reality. Morrison mused

"The

Hollow

Men"

(meaning himself no doubt), "People have the

feeling that what's going on outside isn't real,

REFERENCES

just a bunch of staged events." Morrison desperately wanted to "Break on Through." And BEYLE, H. M. (Pseudonym: Stendhal) The Life of Henry

Brulard. London: Merlin Press, 1958.

other songs as well as the poetry communicate

that he didn't like being where he washe ELIOT, T. S. "The Hollow Men." Collected Poems. New

York: Harcourt, Bruce, & World, 1958.

wanted to be someplace else. To escape "Way

FAIRBAIRN, W. R. D. Psychoanalytic Studies of the Perback deep into the brain, Back where there's

sonality. London: Tavistock Publications, 1952.

never any pain."

GUNTRIP, H. S. Personality Structure and Human Interaction. New York: International Universities Press, 1961.

His poetry betrays a preoccupation with death

GUNTRIP, H. S. Schizoid Phenomena, Object Relations,

and sex, both as means of liberation from life.

and the Self. New York: International Universities Press,

"Light My Fire" strains for a release from the

1969.

cycle of birth-orgasm-death. And textual GUNTRIP, H. S. Psychoanalytic Theory, Therapy and the

Self. New York: Basic Books, 1971.

analyses of the poetry establish a consuming

theme of sex-death and death-sex, and how to KERNBERG, O. F. "International Object Relations: Building

Stones of the Mind." Contemporary Psychology, 17,

get to one by means of the other.

No. 1, 1972.

The seriously schizoid person has a unique KLEIN, M. The Psycho-Analysis of Children. London:

Hogarth Press, 1932.

rapport with death. The apathy and "life-

THE END OF JIM MORRISON

MORRISON, J. The Lords and the New Creatures. Simon &

Schuster (Touchstone Paperback), 1971.

STEIN, H. "Reflections on Schizoid Phenomena."

Psychiatry and Social Science Review, June 1969.

WINNICOTT, D. W. Collected Papers: Through Pediatrics

to Psycho-Analysis. New York: Basic Books, 1958.

427

WINNICOTT, D. W. The Maturational Process and the

Facilitating Environment. New York: International Universities Press, 1965.

WOLFE, B. "The Real Life-Death of Jim Morrison."

Esquire, June 1971.

You might also like

- Sun RA - Myth, Music & MediaDocument5 pagesSun RA - Myth, Music & MediashekereafricaNo ratings yet

- Hypertension in Pregnancy ACOG 2013Document10 pagesHypertension in Pregnancy ACOG 2013lcmurillo100% (1)

- Preopanc Trial - PancreasDocument20 pagesPreopanc Trial - PancreasRajalakshmi RadhakrishnanNo ratings yet

- Jim Morrison - "The Lords"Document18 pagesJim Morrison - "The Lords"Harsh ChoudharyNo ratings yet

- The History of The Brazilian Black Metal SceneDocument9 pagesThe History of The Brazilian Black Metal SceneThornsNo ratings yet

- Aunt Pat EditDocument7 pagesAunt Pat EditDave56No ratings yet

- Henry Flynt Selected WritingsDocument274 pagesHenry Flynt Selected WritingsVictor CironeNo ratings yet

- GLP Vs 17025Document6 pagesGLP Vs 17025Nadhra HaligNo ratings yet

- Chapter 3 Research Methodology This Chapter ContainsDocument15 pagesChapter 3 Research Methodology This Chapter Containspatchu141594% (52)

- ULSADO-JSA - Installation of Temporary Fence GateDocument2 pagesULSADO-JSA - Installation of Temporary Fence GateKelvin TanNo ratings yet

- Chaos To Creation The Enigma of Bob Dylan (Part 3)Document7 pagesChaos To Creation The Enigma of Bob Dylan (Part 3)Susanta BhattacharyyaNo ratings yet

- Dreadlock Rec.Document165 pagesDreadlock Rec.BjornGayNo ratings yet

- Jim Morrison Top 10 Commandments 0607Document26 pagesJim Morrison Top 10 Commandments 0607David Shiang100% (2)

- The Lizard KingDocument8 pagesThe Lizard KingGabriel MisifusNo ratings yet

- Lionel Ziprin - FriezeDocument6 pagesLionel Ziprin - FriezeScott MartinNo ratings yet

- LoreoftheMagi PDFDocument43 pagesLoreoftheMagi PDFciejhae3111No ratings yet

- Twin Peaks - The Return (101 My Log Has A Message For You)Document59 pagesTwin Peaks - The Return (101 My Log Has A Message For You)Janine LeanoNo ratings yet

- Lucifer v03 n14 October 1888Document88 pagesLucifer v03 n14 October 1888lisNo ratings yet

- Sundari Testimonial 1 - Lynn MichaelianDocument3 pagesSundari Testimonial 1 - Lynn MichaelianDigital CitizensNo ratings yet

- MetallicaDocument32 pagesMetallicaÓscar Soto-GuaderramaNo ratings yet

- Reed - Let's Make Love Before You Die "Warm Leatherette," Boredom and The Invention of The 1980sDocument8 pagesReed - Let's Make Love Before You Die "Warm Leatherette," Boredom and The Invention of The 1980sthoushaltnot100% (1)

- Kut V ChaosDocument96 pagesKut V ChaosMark FrazzettoNo ratings yet

- In His Own Write and A Spaniard in the WorksFrom EverandIn His Own Write and A Spaniard in the WorksRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (144)

- Sara Dylan & The Rise of The Anti-Zen in Seventies Bob: How Weak Was The FoundationDocument9 pagesSara Dylan & The Rise of The Anti-Zen in Seventies Bob: How Weak Was The Foundation'Messianic' DylanologistNo ratings yet

- Desire and Crisis - The Operation of Cinematic Masks in Stanley Kubrick's Eyes Wide ShutDocument13 pagesDesire and Crisis - The Operation of Cinematic Masks in Stanley Kubrick's Eyes Wide ShutgeorgefeickNo ratings yet

- Nine Inch Nails - The Prodigy Posts (November 1992)Document13 pagesNine Inch Nails - The Prodigy Posts (November 1992)SelfCloakNo ratings yet

- 6.30.11 BeatlesBible - Com Working Class MysticDocument3 pages6.30.11 BeatlesBible - Com Working Class MysticQuestBooks100% (1)

- Lou Reed's ObituaryDocument3 pagesLou Reed's ObituaryNoé LopesNo ratings yet

- A Burzum Story Eng PDFDocument23 pagesA Burzum Story Eng PDFJoseLafuentedeAraujo0% (1)

- Eutopia Poul Anderson PDFDocument2 pagesEutopia Poul Anderson PDFMoniqueNo ratings yet

- Hotter Than a Match Head: My Life on the Run with The Lovin’ SpoonfulFrom EverandHotter Than a Match Head: My Life on the Run with The Lovin’ SpoonfulRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (4)

- The Candy Men: The Rollicking Life and Times of the Notorious Novel CandyFrom EverandThe Candy Men: The Rollicking Life and Times of the Notorious Novel CandyNo ratings yet

- Metaclysmia DiscordiaDocument30 pagesMetaclysmia DiscordiaJason CullenNo ratings yet

- Concerto For Magic and Mysticism - Esotericism and Western MusicDocument9 pagesConcerto For Magic and Mysticism - Esotericism and Western Musicbde_gnasNo ratings yet

- The Velvet Underground The Black Angel's Death Song Mirrors Bob Dylan CareerDocument4 pagesThe Velvet Underground The Black Angel's Death Song Mirrors Bob Dylan CareerAlan Jules WebermanNo ratings yet

- Excerpt From "The Friedkin Connection: A Memoir" by William Friedkin. Copyright 2013 by William Friedkin. Reprinted Here by Permission of Harper. All Rights Reserved.Document5 pagesExcerpt From "The Friedkin Connection: A Memoir" by William Friedkin. Copyright 2013 by William Friedkin. Reprinted Here by Permission of Harper. All Rights Reserved.wamu8850No ratings yet

- Stephen Doty June 2019 On The Writing Style of Bob DylanDocument7 pagesStephen Doty June 2019 On The Writing Style of Bob DylanSpaner_os100% (1)

- Stone GodfatherIIDocument9 pagesStone GodfatherIIM MaliNo ratings yet

- List of Fairy TalesDocument11 pagesList of Fairy TalesLara HunterNo ratings yet

- GREBO!: The Loud & Lousy Story of Gaye Bykers On Acid and CrazyheadFrom EverandGREBO!: The Loud & Lousy Story of Gaye Bykers On Acid and CrazyheadNo ratings yet

- Top 100 Psychedelic SongsDocument2 pagesTop 100 Psychedelic SongsGii Selle100% (1)

- Decibel Coverstory Typeo 0407 150Document4 pagesDecibel Coverstory Typeo 0407 150Kit Traverse100% (1)

- By Karen Mutton © 2005: Email: WebsiteDocument7 pagesBy Karen Mutton © 2005: Email: WebsiteAMITH OKNo ratings yet

- The Complete Ourang-Outang by de Villo SloanDocument127 pagesThe Complete Ourang-Outang by de Villo SloanMinXusLynxusNo ratings yet

- CPR Salbutamol+Ipratropium Neb (BRODIX PLUS) 35'sDocument2 pagesCPR Salbutamol+Ipratropium Neb (BRODIX PLUS) 35'sRacquel SolivenNo ratings yet

- Characteristic of NewbornDocument9 pagesCharacteristic of Newbornbabyrainbow100% (15)

- Effect of Applying Therapeutic Architecture On The Healing of Drug AddictsDocument8 pagesEffect of Applying Therapeutic Architecture On The Healing of Drug AddictsRiya BansalNo ratings yet

- Unheard Voices of Mothers With Sexually Abused Children: A Multiple Case StudyDocument18 pagesUnheard Voices of Mothers With Sexually Abused Children: A Multiple Case StudyPsychology and Education: A Multidisciplinary JournalNo ratings yet

- Hps User Guide Hps6Document339 pagesHps User Guide Hps6Mostafa FayadNo ratings yet

- Discussion: Part 1: Nurse's Knowledge Toward MRSADocument1 pageDiscussion: Part 1: Nurse's Knowledge Toward MRSAMustafa KhudhairNo ratings yet

- Moderna Launches Vaccine Trials To Tackle New Coronavirus StrainDocument26 pagesModerna Launches Vaccine Trials To Tackle New Coronavirus Strainhttp://lamparinna.blogspot.comNo ratings yet

- ECardDocument1 pageECardBasanNo ratings yet

- U07a1 - Jasmone RigginsDocument5 pagesU07a1 - Jasmone RigginsjasmonerNo ratings yet

- Analisa Risiko Kecelakaan Kerja Pada Proyek Konstruksi Jembatan Musi Vi PalembangDocument6 pagesAnalisa Risiko Kecelakaan Kerja Pada Proyek Konstruksi Jembatan Musi Vi PalembangRoraNo ratings yet

- 0610 - s17 - QP - 42 AnsweredDocument20 pages0610 - s17 - QP - 42 Answered-Bleh- WalkerNo ratings yet

- Vaccines 10 00472Document17 pagesVaccines 10 00472IdmNo ratings yet

- Novel AUD Likelihood Detection Based On EEG ClassificationDocument5 pagesNovel AUD Likelihood Detection Based On EEG ClassificationsupravaNo ratings yet

- Pediatric Community Acquired PneumoniaDocument24 pagesPediatric Community Acquired PneumoniaJames Lagamayo JavierNo ratings yet

- 2020 Tanzania in FiguresDocument110 pages2020 Tanzania in FiguresDaveNo ratings yet

- Alternate Rapid Maxillary Expansion and Constriction (Alt-RAMEC) Protocol: A Comprehensive Literature ReviewDocument5 pagesAlternate Rapid Maxillary Expansion and Constriction (Alt-RAMEC) Protocol: A Comprehensive Literature ReviewGaby Cotrina LiñanNo ratings yet

- Assessment of Substance Abuse Among Adolescents in India: An OverviewDocument6 pagesAssessment of Substance Abuse Among Adolescents in India: An OverviewInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNo ratings yet

- MorbiliDocument30 pagesMorbiliMjNo ratings yet

- CAPE Communication Studies 2009 P3BDocument4 pagesCAPE Communication Studies 2009 P3BRiaz JokanNo ratings yet

- 613bd813608b5 - c350 - Carolyn - Cross - Docx 5Document8 pages613bd813608b5 - c350 - Carolyn - Cross - Docx 5t.bowdleNo ratings yet

- MedDRA Coding Basics WebinarDocument39 pagesMedDRA Coding Basics WebinarCosmina Georgiana100% (1)

- ISMT 12 - Day 402 - Rita - Posterior Cervical Laminectomy and Fusion Surgery C3-C7Document21 pagesISMT 12 - Day 402 - Rita - Posterior Cervical Laminectomy and Fusion Surgery C3-C7Vito MasagusNo ratings yet

- Kamilya Jamel Baljon, Muhammad Hibatullah Romli, Adibah Hanim Ismail, Lee Khuan, Boon How ChewDocument13 pagesKamilya Jamel Baljon, Muhammad Hibatullah Romli, Adibah Hanim Ismail, Lee Khuan, Boon How ChewOva Tri Pra Setia MayasarieNo ratings yet

- Guideline Management Crushing and Screening Feb10 1Document10 pagesGuideline Management Crushing and Screening Feb10 1Karin AndersonNo ratings yet

- Abdominal Acupuncture For DepressionDocument35 pagesAbdominal Acupuncture For DepressionAGNESE YOLOTZIN OLIVERA TORO REYESNo ratings yet