Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Chewing Mastication

Chewing Mastication

Uploaded by

Muizzudin AzzaOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Chewing Mastication

Chewing Mastication

Uploaded by

Muizzudin AzzaCopyright:

Available Formats

Int J Clin Exp Med 2012;5(4):326-331

www.ijcem.com /ISSN:1940-5901/IJCEM1207001

Original Article

Chewing side preference in first and all mastication cycles

for hard and soft morsels

Masumeh Zamanlu1, Saeed Khamnei2, Shaker SalariLak3, Siavash Savadi Oskoee4, Seyed Kazem

Shakouri5, Yousef Houshyar5, Yaghoub Salekzamani5

1Medical student, Research Center of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, Student Research Committee, Tabriz

University of Medical Sciences, Tabriz, Iran, and Department of Epidemiology and Biostatistics, Faculty of Medicine,

Urmia University of Medical Sciences, Urmia, Iran; 2Physiology Department, Islamic Azad University, Tabriz Branch,

Tabriz, Iran, Research Center of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, Tabriz University of Medical Sciences, Tabriz,

Iran; 3Public health Department, Faculty of Medicine, Islamic Azad University, Tabriz Branch, Tabriz, Iran; 4Dental and

Periodontal Research Center, Tabriz University of Medical Sciences, Tabriz, Iran; 5Research Center of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, Tabriz University of Medical Sciences, Tabriz, Iran.

Received July 2, 2012; accepted August 2, 2012; Epub August 22, 2012; Published September 15, 2012

Abstract: Preferred chewing side is a still controversial matter and various methods used have yielded some inconsistencies. The aim of this study is to compare the preference determined in different conditions. Nineteen healthy subjects were offered hard (walnut) and soft (cake) foods, while the electromyography was recorded from their masseter

muscles, in 2009 in the Research Center of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, Tabriz University of Medical Sciences, Tabriz, Iran. Four occurrences were determined as the side of the first chews/all chews in the two food types,

and then analyzed for correlations and agreements. For hard food 73.68% and for soft food 57.89% of the subjects

showed preference. The comparison of all chews showed a highly significant preference towards the right side in both

food types (p=0.000 & 0.003). There was both correlation and agreement between the first chew preferences in both

food types, and an agreement between the first and all chew preferences in the hard food. Therefore, there seems to

exist some laterality in mastication, which is more explicit when using hard food and assessing all chews.

Keywords: Chewing laterality, masticatory preferred side, food texture, surface electromyography, method comparison

Introduction

The concept of chewing preference (chewing

laterality) has developed gradually during decades and has implications for dentistry procedures. A seminal text in dentistry argued that

unilateral chewing occurs in most of the population with an apparent preference for chewing on

a particular side [1, 2].

Unfortunately, this preference has no universal

definition and yet needs to get honed. Its determination is somewhat complex and, therefore, it

has been investigated with various methods [35]. Some studies have introduced preference as

the side in which most of the first chews or random chews occurred, and assessed the chews

by observation; asking the subjects, kinesiography (instruments recording jaw movements), or

electromyography; most authors have considered the side of the first cycle as chewing preferred side.

A classic study reported there was no overall

significant preference for either the right or left

side in chewing [6], but in most other studies

masticatory preference was demonstrated.

Some studies report chews or subjects with no

preference more than others [5, 7, 8, 9]. Different results could be the consequence of different methods employed. Varela et al [3] compared the methods of observation and kinesiography and reported no statistically significant

agreement; nevertheless, both techniques reflected a marked preference for the right side.

Thus, attempts for the complex determination of

chewing preference have manifested inconsistencies, and, similarly, it is of essential research

Chewing preference, first/all cycles, hard/soft food

importance to investigate more aspects of this

preference and find a more convincing estimate

of it.

Most investigations were done by gum-chewing

[1, 3, 6, 8, 10-12]; however, food texture may

affect the chewing pattern. Texture is the quality

of the food perceived by an individual. Although

somehow related, it is not the same as food

structure. This characteristic of food is determined by structural parameters detected by

several sensory modalities affected by psychological factors and memory [13-15]. Chewing is

governed by a pattern generator which is regulated by sensory feedback [16]. This feedback is

triggered by texture perception. It is known that

the food texture affects muscle activity and

chewing cycles, so chewing preference may differ in various food textures [4, 9, 16, 17]. Texture includes several parameters such as hardness, cohesiveness, viscosity, size, shape and

etc [14]. Studies have assessed some of the

parameters and reported hardness and size to

be effective on chewing movements [4, 17, 18].

In the current study, we recorded the chewing

cycles in two food textures (hard and soft), determining the preferred side for starting the

mastication and for all the chewing sequences

(calculating Asymmetry indexes) in each food

texture. The different preferred sides determined were then compared to show whether

they are consistent. The aim is to investigate

different conditions in order to find an efficient

design for assessing this preference. Upon an

extensive look at the literature, we found no

study comparing the preference of the first and

all masticatory cycles.

Materials and methods

Nineteen young healthy subjects (12 female

and 7 male) mean SD age 19.42 2.27 years

participated in this study. All subjects gave their

voluntary, written and informed consent for their

participation. The study was reviewed and approved by the Investigation Deputy of Tabriz

University of Medical Sciences and the Ethics

Committee of the university and have therefore

been performed in accordance with the ethical

standards. None of the subjects exhibited any

signs of jaw dysfunction or any symptomatic

dental or chewing problem. All subjects were

familiarized with the experiments, and to reduce

bias, explanations were given with no emphasis

327

on chewing side. Each subject ate a piece of

walnut (hard food) and a piece of cake (soft

food) while surface electromyography (surface

EMG, Biometrics LTD, Cwmfelinfach, Gwent, UK)

of the Masseter muscles of both sides were

recorded. The instrument possessed a device

which contained two irremovable electrodes

with a fixed distance between them, placed on

the skin by special removable labels, which

made the electrodes steady. Before starting the

experiment of chewing the food, the subjects

were asked to clench their teeth to the highest

force. This presented the electromyographic

maximum contractility on both sides. Chewing

preferred side in four different occurrences was

determined for each subject including 1) the

side of the first chewing cycles in the hard food,

2) the side of the first chewing cycles in the soft

food, (we assessed the first three chewing cycles) 3) the side of the majority of cycles in the

hard food, and 4) the side of the majority of cycles in the soft food. A preference index

(Asymmetry index- AI) was calculated for the

hard and soft food separately to obtain a degree

of preference for these food types: AI = (R L)/

(R + L), where R is the number of chewing cycles on the right side, L, the number of chewing

cycles on the left side. A subject was considered

to prefer the right side in positive AIs and the

left in negative AIs. Subjects having 0.3<AI<+0.3 were considered to show insignificant preferences.

Statistical analysis

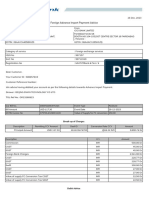

Primary analysis of the EMG activity of Masseter

muscles was done by the EMG software

(surface EMG, Biometrics LTD, Cwmfelinfach,

Gwent, UK) to determine the side of chewing

cycles (Figure 1). The relative pattern of the amplitudes in the maximum contractility presentation was taken into account by the software to

do the right comparison of the amplitudes of the

two sides in each chewing cycle and choose the

dominant side. Further descriptive and analytical statistics were analyzed by SPSS15. To compare the chews of the two sides, Pearson Correlation tests were performed. In order to determine the relationship between the different

preferences determined, Chi-square tests were

used. Also, Cohen's Kappa test was used to establish the extent of the agreement among

them. Values of P<0.05 were considered to be

statistically significant, confidence interval was

considered 95% and all data are presented as

Int J Clin Exp Med 2012;5(4):326-331

Chewing preference, first/all cycles, hard/soft food

Table1. The sides of chewing preference in the four different occurrences, presented as percentages

Chewing cycle(s)

Food type

Right

Preferred side

Left

None

Overall

preference

First

Hard

63.6%

36.3%

First

Soft

57.9%

42.1%

All

Hard

47.36%

26.32%

26.32%

73.68%

All

Soft

47.36%

10.53%

42.11%

57.89%

Table2. The preference index (AI) for the two food types.

Mean

Maximum

Minimum

SD

AI for hard food

0.16

+1

-0.73

0.58

AI for soft food

0.25

+1

-0.64

0.43

means SD.

Results

For hard food, 73.68% and for soft food,

57.89% of the subjects showed masticatory

preference. The preferences in the four occurrences in all subjects, collectively, are shown in

Table 1.

There was a significant correlation between the

preferred sides in the first chewing cycles of the

two food types with above average agreement

(Kappa value: 0.45). There was also an average

agreement between the preferred sides in the

first and all chewing cycles of the hard food

(Kappa value: 0.36). Between other preferences, there existed no significant correlation or

agreement.

The comparison of all chewing cycles showed a

highly significant preference towards the right

side in both food types (P= 0.000 & 0.003).

While 31.5% of the subjects preferred the right

side in all the four occurrences, no subject had

left preference in the four occurrences coincidentally.

The range of AI calculated for subjects are

shown in Table 2. No subject had an AI=0.

Figure 1. The electromyographic recordings of the left

and right masseter muscles of a male volunteer during chewing. L indicates the recordings of the left

side; R indicates the recordings of the right side. The

arrows show the point where the volunteer has

switched from chewing by the right side to the left

side.

328

Discussion

Most of our subjects showed masticatory preference, mainly to the right side, and the preference was more apparent in chewing the hard

food (Table 1). For hard food 73.68%of subjects

showed preference to one side and for soft food

Int J Clin Exp Med 2012;5(4):326-331

Chewing preference, first/all cycles, hard/soft food

57.89% (Table 1). Most of the studies do favor

the existence of laterality in chewing process.

But there are some controversies with regard to

details, such as the exact method to reveal it. A

wide range of variation for the percentage of

chewing preference has been reported, in the

order of 45 to 70% of the subjects [3-5, 7, 10].

Our results, in line with previous reports, indicate that most people show preference to one

side in their chewing pattern; but as the results

indicate and some authors have mentioned [5,

17], this preference could be more conspicuous

when it comes to hard food. It has been reported that the bite force differs in the two sides

of the mouth and the side on which more bite

force can be exerted is more likely to be preferred for chewing [4]. Obviously, a harder food

requires more effort to chew than a softer one,

so it can evoke more laterality [17]. Texture and

chewing preference were assessed in two classic studies: Delport et al (1983) had reached

similar results in their study in four different

textures [18]; Hoogmart and Caubergh (1987)

used sugar lump and bread in their study but

made no comment on the texture differences,

merely reporting to find chewing preference in

45% of subjects [7].

Nearly half of our subjects showed a preference

to the right side with different methods, much

more than left preference or no preference. Furthermore, the overall analysis reveals highly

significant preference towards the right side in

both food textures (p=0.000 & 0.003). More

chewing preference in the right side has previously been reported in the literature [1, 4, 9]

which is believed to be an indication of central

regulation of masticatory preference [4].

As to describing chewing preference, some authors tried to show the strength of the preference through calculated preference indexes.

Initially I index was introduced including calculations of the first chews, and recently Asymmetry

index (AI) has been adopted, which is the same

calculation of I index for all masticatory cycles.

We have calculated AI (Table 2) assessing its

agreement with preferred side in first chews.

There was an average agreement between the

preferred sides in the first and all chewing cycles of the hard food, while no such agreement

existed for the soft food. This may indicate that

the laterality evoked by the hard food is more

probable to be towards the same side on which

the first chews occurred; the side with the

329

higher force needed to masticate a hard food.

Moreover, in daily life, when eating soft foods,

the preference of the whole process of chewing

is more likely to differ from the first chews. This

could be assessed more precisely if we repeated the first chews and calculated I indexes,

then comparing them with the AI. It is suggested

that such a comparison be undertaken in future

studies.

We found a significant correlation and an above

average agreement between the preferred sides

in the first chewing cycles of the hard and soft

food. The same preference in the foods with

different textures may indicate that mastication

starts with a similar pattern and the sensory

feedback of the food texture may affect the following chewing sequence. This can explain the

disagreement between AI of the hard food and

the soft food in our study. Nevertheless, some

authors believe that texture perception exists

during observing and handling the food as well

as during food tasting, mastication and swallow

[13-15]. According to our results, it is the texture perception during but not before the initiation of mastication which plays the main role in

determining the preferred side for chewing. In

other words, texture perception prior to the actual chewing process is probably not strong

enough to affect the start of mastication, so, in

most cases the pattern of mastication might

have a fixed beginning, insensitive to texture

signals, possibly starting with a specialized side

for sensing food texture, or probably the side

which is more comfortable and more effective

for chewing. It has been stated that oral processes have a significant effect on the breakdown of the physicochemical structure of the

food in the mouth and, thus, on the sensory

perception. Texture perception is therefore a

dynamic process, with changing food structures

and changing perception in time, while the food

is being masticated [14]. So the feedback governing the chewing pattern changes as mastication proceeds.

These changes together with the highly significant preferences derived from all chewing cycles, and AIs as strong as +1 point to the fact

that assessing all the chewing cycles for AI calculation is more reliable for preference determination.

It is commonly accepted that strictly unilateral

chewing has a high potentially traumatic effect

Int J Clin Exp Med 2012;5(4):326-331

Chewing preference, first/all cycles, hard/soft food

on dentition, jaw muscles and the Temporomandibular Joint (TMJ). Restoration of missing dental units on the preferred side would improve

chewing efficiency and ease the occlusal burden on the existing teeth. It follows that examination and recording of chewing side preference

merits consideration in the routine dental examination and treatment planning [1]. Also,

natural teeth on this side may decay earlier and

more precise care and examination may be

needed. Our results provide more insight into

this important issue. However, further investigation is needed to clarify the clinical relevance of

such findings [1]. If preferred side is to be considered in dentistry procedures without precise

examination of this preference, a tenable assumption is that most people prefer to chew

with the right side.

We used Surface electromyography (Surface

EMG) for recording chewing cycles. For observing and recording muscle functions and movements, EMG has frequently been employed in

different studies. Especially recording from the

skin surface is a common procedure, which is

non-invasive and simple [19]. EMG validity for

masticatory studies has been assessed in previous investigations. It has been reported that the

preferred chewing side determined by EMG and

observation are significantly correlated (p<

0.001) [20]. Another study concludes that by

reducing the influences of electrode relocation

EMG analysis may be used for the evaluation of

masticatory muscle activity [21]. Some classic

studies had casted doubt on electromyography

applicability for this purpose [7, 18, 22].

Conclusion

The different conditions assessed here shows

that chewing preference can be better manifested assessing all the masticatory cycles (by

Asymmetry index) than just the first cycle. Also,

using hard food evokes more laterality.

Acknowledgements

We wish to express our deep appreciation to our

subjects who voluntarily participated in this experiment. We also make a point of our gratitude

to Dr Y. Hadidi for agreeing to edit the English

text of this paper. The current investigation was

financially supported in the Research Center of

Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, Tabriz

University of Medical Sciences, Tabriz, Iran.

330

EMG recording and analyses were done in the

mentioned research center.

Address correspondence to: Dr. Saeed Khamnei, full

professor, Physiology Department, Islamic Azad University, Tabriz Branch, Manzarieh st., Tabriz, Iran Tel:

009844113364664; Fax: 009844113364664; Email: khamnei-s@iaut.ac.ir

References

[1]

Nissan J, Gross MD, Shifman A, Tzadok L, Assif

D. Chewing side preference as a type of hemispheric laterality. J Oral Rehabil 2004; 31: 412416.

[2] Ahlgren J. Masticatory movement in man. In:

Anderson DJ, Mathews B, editors: Mastication.

Bristol, UK: John Wright 1976; pp: 123

[3] Varela JM, Castro NB, Biedma BM, Da Silva

Domnguez JL, Quintanilla JS, Muoz FM, Penn

US, Bahillo JG. A comparison of the methods

used to determine chewing preference. J Oral

Rehabil 2003; 30: 990-994.

[4] Martinez-Gomis J, Lujan-Climent M, Palau S,

Bizar J, Salsench J, Peraire M. Relationship

between chewing side preference and handedness and lateral asymmetry of peripheral factors. Arch Oral Biol 2009; 54: 101-107.

[5] Ratnasari A, Hasegawa K, Oki K, Kawakami S,

Yanagi Y, Asaumi JI, Minagi S. Manifestation of

preferred chewing side for hard food on TMJ

disc displacement side. J Oral Rehabil 2011;

38: 12-17.

[6] Christensen LV, Radue JT. Lateral preference in

mastication: a feasibility study. J Oral Rehabil

1985; 12: 421-427.

[7] Hoogmartens MJ, Caubergh MA. Chewing side

preference during the first chewing cycle as a

new type of lateral preference in man. Electromyogr Clin Neurophysiol 1987; 27: 3-6.

[8] Kazazoglu E, Heath MR, Mller F. A simple test

for determination of the preferred chewing

side. J Oral Rehabil 1994; 21: 723.

[9] Paphangkorakit J, Thothongkam N, Supanont

N. Chewing-side determination of three food

textures. J Oral Rehabil 2006; 33: 2-7.

[10] Mc Donnell ST, Hector MP, Hannigan A. Chewing side preferences in children. J Oral Rehabil

2004; 31: 855-860.

[11] Wilding RJ, Adams LP, Lewin A. Absence of association between a preferred chewing side

and its area of functional occlusal contact in

the human dentition. Arch Oral Biol 1992; 37:

423-428.

[12] Shinagawa H, Ono T, Honda E, Sasaki T, Taira

M, Iriki A, Kuroda T, Ohyama K. Chewing-side

preference is involved in differential cortical

activation patterns during tongue movements

after bilateral gum-chewing: a functional magnetic resonance imaging study. J Dent Res

2004; 83: 762-766.

Int J Clin Exp Med 2012;5(4):326-331

Chewing preference, first/all cycles, hard/soft food

[13] Szczesniak AS. Texture is a sensory property.

Food Quality and Preference 2002; 13: 215225.

[14] Wilkinson C, Dijksterhuis GB, Minekus M. From

food structure to texture. Trends in Food Science & Technology 2000; 11: 442-450.

[15] Ito S, Ogawa H. Neural activities in the frontoopercular cortex of macaque monkeys during

tasting and mastication. Jpn J Physiol 1994;

44: 141-156.

[16] Lassauzay C, Peyron MA, Albuisson E, Dransfield E, Woda A. Variability of the masticatory

process during chewing of elastic model foods.

Eur J Oral Sci 2000; 108: 484-492.

[17] Mizumori T, Tsubakimoto T, Iwasaki M, Nakamura T. Masticatory laterality--evaluation and

influence of food texture. J Oral Rehabil 2003;

30: 995-999.

[18] Delport HP, de Laat A, Nijs J, Hoogmartens MJ.

Preference pattern of mastication during the

first chewing cycle. Electromyogr Clin Neurophysiol 1983; 23: 491-500.

[19] Kumai T. Location of the neuromuscular junction of the human masseter muscle estimated

from the low frequency component of the surface electromyogram. Jpn J Physiol 2005; 55:

331

61-68.

[20] Christensen LV, Radue JT. Lateral preference in

mastication: an electromyographic study. J Oral

Rehabil 1985; 12: 429-434.

[21] Saifuddin M, Miyamoto K, Ueda HM, Shikata N,

Tanne K. A quantitative electromyographic

analysis of masticatory muscle activity in usual

daily life. Oral Dis 2001; 7: 94-100.

[22] Giannitrapani D. Laterality preference, electrophysiology and the brain. Electromyogr Clin

Neurophysiol 1979; 19: 105-123.

Int J Clin Exp Med 2012;5(4):326-331

You might also like

- Combined Footing Design Excel SheetDocument21 pagesCombined Footing Design Excel SheetAbdullah Al Mamun0% (1)

- LEA 1601 Curing Monolithics Containing Hydraulic CementDocument4 pagesLEA 1601 Curing Monolithics Containing Hydraulic CementMichelle Wilson100% (1)

- Actualizacion ElmDuinoDocument42 pagesActualizacion ElmDuinoLauraNo ratings yet

- Risk Ass - TK-4742-WELDING ACTVITIES FOR REST AREA PREPARATIONDocument6 pagesRisk Ass - TK-4742-WELDING ACTVITIES FOR REST AREA PREPARATIONnsadnanNo ratings yet

- Chewing-Side Determination of Three Food Textures: J.Paphangkorakit, N.Thothongkam &N.SupanontDocument6 pagesChewing-Side Determination of Three Food Textures: J.Paphangkorakit, N.Thothongkam &N.Supanontapi-3710948No ratings yet

- 4713-7 8.16 Afzaninawati Suria YusofDocument5 pages4713-7 8.16 Afzaninawati Suria Yusof568563No ratings yet

- R - Observational Study On Knowledge and EatingDocument8 pagesR - Observational Study On Knowledge and EatingErza GenatrikaNo ratings yet

- Indicators of Masticatory Performance Among Elderly Complete Denture WearersDocument6 pagesIndicators of Masticatory Performance Among Elderly Complete Denture WearersKriti MalhotraNo ratings yet

- A Comparison of Functional Analysis Methods of InappropriateDocument19 pagesA Comparison of Functional Analysis Methods of InappropriateMirele Pereira de Aquino AlmeidaNo ratings yet

- (ARTIGO) ARCELUS, Et Al. - Prevalence of Eating Disorders Amongst Dancers. A Systemic Review and Meta-Analysis (2013) - PUBMEDDocument28 pages(ARTIGO) ARCELUS, Et Al. - Prevalence of Eating Disorders Amongst Dancers. A Systemic Review and Meta-Analysis (2013) - PUBMEDGuido BrustNo ratings yet

- Comportamientos DieteticosDocument13 pagesComportamientos DieteticosAna AcuñaNo ratings yet

- Hubungan Lingkar Lengan Atas Dengan ObesDocument6 pagesHubungan Lingkar Lengan Atas Dengan ObesYakobus Anthonius SobuberNo ratings yet

- TehranDocument6 pagesTehranNadiah Umniati SyarifahNo ratings yet

- Dietary Patterns and Overweight/Obesity: A Review ArticleDocument8 pagesDietary Patterns and Overweight/Obesity: A Review ArticleTri UtomoNo ratings yet

- 8 203Document13 pages8 203Ceren ÖZERNo ratings yet

- KJCN 22 336Document11 pagesKJCN 22 336Jemelyn De Julian TesaraNo ratings yet

- SUPPHare2009p2088Science PDFDocument21 pagesSUPPHare2009p2088Science PDFrayestmNo ratings yet

- Konsumsi Fast FoodDocument9 pagesKonsumsi Fast FoodBimo YensyaNo ratings yet

- Dokumen Tanpa JudulDocument10 pagesDokumen Tanpa JudulZakia AmeliaNo ratings yet

- European Journal of Theoretical and Applied SciencesDocument9 pagesEuropean Journal of Theoretical and Applied SciencesEJTAS journalNo ratings yet

- JCM 08 00454Document8 pagesJCM 08 00454Harnoor GhumanNo ratings yet

- Yeomans 1996Document15 pagesYeomans 1996qweqweqweqwzaaaNo ratings yet

- Ansar, Nurhaedar Jafar, Citrakesumasari: PendahuluanDocument7 pagesAnsar, Nurhaedar Jafar, Citrakesumasari: Pendahuluanudin keytimuNo ratings yet

- Hubungan Pengetahuan Gizi Aktivitas FisikDocument5 pagesHubungan Pengetahuan Gizi Aktivitas FisikshofiNo ratings yet

- Dieta MediterraneaDocument13 pagesDieta MediterraneaJoana FerreiraNo ratings yet

- Evaluación Multi-Método de Los Problemas de Alimentación en Los Niños Con Trastornos Del Espectro AutistaDocument10 pagesEvaluación Multi-Método de Los Problemas de Alimentación en Los Niños Con Trastornos Del Espectro AutistaBerurobNo ratings yet

- Spirulina ObesidadeDocument10 pagesSpirulina ObesidadeIsabela CastroNo ratings yet

- Ewc661 ProposalDocument30 pagesEwc661 ProposalHudal FirdausNo ratings yet

- Meiselman (2003) - A Three-Factor Approach To Understanding Food QualityDocument7 pagesMeiselman (2003) - A Three-Factor Approach To Understanding Food QualityGislayneNo ratings yet

- 10 1002@jaba 650Document23 pages10 1002@jaba 650Gabriela fernandesNo ratings yet

- Crossley and Khan, 2001-FCQ PDFDocument5 pagesCrossley and Khan, 2001-FCQ PDFAli MehmoodNo ratings yet

- Article 8 MemoireDocument8 pagesArticle 8 MemoirebentatanihalNo ratings yet

- Drama PensiDocument5 pagesDrama PensiNadiah Umniati SyarifahNo ratings yet

- Nutrition: Keren Papier B.P.H. (Hons), Faruk Ahmed PH.D., Patricia Lee PH.D., Juliet Wiseman PH.DDocument7 pagesNutrition: Keren Papier B.P.H. (Hons), Faruk Ahmed PH.D., Patricia Lee PH.D., Juliet Wiseman PH.DCiprian MandrutiuNo ratings yet

- Ohkuma, 2015. META ANÁLISE - ANC E ABESIDADEDocument8 pagesOhkuma, 2015. META ANÁLISE - ANC E ABESIDADEMaria MachadoNo ratings yet

- Dietary Patterns and Colon Cancer Risk in Whites and African Americans in The North Carolina Colon Cancer StudyDocument8 pagesDietary Patterns and Colon Cancer Risk in Whites and African Americans in The North Carolina Colon Cancer StudyRyneil AlmarioNo ratings yet

- Does Orthodontic Treatment Harm Children's DietsDocument6 pagesDoes Orthodontic Treatment Harm Children's DietsNaliana LupascuNo ratings yet

- NIH Public Access: Author ManuscriptDocument7 pagesNIH Public Access: Author ManuscriptAnca RaduNo ratings yet

- Arisawa Et Al, 2014Document12 pagesArisawa Et Al, 2014Jesana LopesNo ratings yet

- Choosing Between Two Evils - The Determinants of Preferences For Two Equally Goal-Inconsistent Options PDFDocument12 pagesChoosing Between Two Evils - The Determinants of Preferences For Two Equally Goal-Inconsistent Options PDFJosselineNo ratings yet

- Hilbert 2012Document7 pagesHilbert 2012pentrucanva1No ratings yet

- Greater Foodrelated Stroop Interference Following Behavioral Weight Loss Intervention 2165 7904.1000187Document3 pagesGreater Foodrelated Stroop Interference Following Behavioral Weight Loss Intervention 2165 7904.1000187Eima Siti NurimahNo ratings yet

- Impact of Nutrition Counselling On Multiple Sclerosis Patients Nutritional Status: Randomized Controlled Clinical TrialDocument19 pagesImpact of Nutrition Counselling On Multiple Sclerosis Patients Nutritional Status: Randomized Controlled Clinical Trialmutiara fajriatiNo ratings yet

- Determinants of Healthy Eating: Motivation, Abilities and Environmental OpportunitiesDocument18 pagesDeterminants of Healthy Eating: Motivation, Abilities and Environmental OpportunitiesDeepa ThangaveluNo ratings yet

- Prevalence and Risk Factors For Eating Disorders in Indian Adolescent FemalesDocument5 pagesPrevalence and Risk Factors For Eating Disorders in Indian Adolescent FemalesLydia SylviaNo ratings yet

- Clinical StudyDocument8 pagesClinical StudyAjie WitamaNo ratings yet

- Sindroma DispepsiaDocument6 pagesSindroma DispepsiaMifta Paramitha MuchlisNo ratings yet

- 2015 Students Awareness of Their Temperament and Adjusted According To The Daily DietDocument2 pages2015 Students Awareness of Their Temperament and Adjusted According To The Daily DietAhmad Yar SukheraNo ratings yet

- 10.1007@978 3 030 03901 13Document39 pages10.1007@978 3 030 03901 13Tiara Kurnia Khoerunnisa FapertaNo ratings yet

- Ijerph 17 07143Document14 pagesIjerph 17 07143Cristina Freitas BazzanoNo ratings yet

- Serly Wardoyo - PHDocument9 pagesSerly Wardoyo - PHSherly WardoyoNo ratings yet

- Exp5 Hedonic TestDocument6 pagesExp5 Hedonic TestSyarmine Aqila IsaNo ratings yet

- Dietary Patterns, Insulin Resistance, and Prevalence of The Metabolic Syndrome in WomenDocument9 pagesDietary Patterns, Insulin Resistance, and Prevalence of The Metabolic Syndrome in WomenMukhlidahHanunSiregarNo ratings yet

- Korean DietDocument5 pagesKorean DietArthurNo ratings yet

- Lifestyle Habits and MortalityDocument11 pagesLifestyle Habits and MortalityDenisa BrihanNo ratings yet

- Nutrients: Dietary Fiber and Metabolic Syndrome: A Meta-Analysis and Review of Related MechanismsDocument17 pagesNutrients: Dietary Fiber and Metabolic Syndrome: A Meta-Analysis and Review of Related MechanismsIlmi Dewi ANo ratings yet

- Nutrients 07 05424Document4 pagesNutrients 07 05424Aniket VermaNo ratings yet

- Nutritional Knowledge, Food Habits and Health Attitude of Chinese University Students - A Cross Sectional StudyDocument11 pagesNutritional Knowledge, Food Habits and Health Attitude of Chinese University Students - A Cross Sectional StudyJaymier SahibulNo ratings yet

- An Evaluation of Chewing and Swallowing For A Child Diagnosed With AutismDocument12 pagesAn Evaluation of Chewing and Swallowing For A Child Diagnosed With Autismkhadidja BOUTOUILNo ratings yet

- Food Quality and Preference: Vikki O'Neill, Stephane Hess, Danny CampbellDocument12 pagesFood Quality and Preference: Vikki O'Neill, Stephane Hess, Danny Campbellnovi diyantoNo ratings yet

- Appetite: John C. Peters, Sarit Polsky, Rebecca Stark, Pan Zhaoxing, James O. HillDocument6 pagesAppetite: John C. Peters, Sarit Polsky, Rebecca Stark, Pan Zhaoxing, James O. HillMaribel Londoño FlórezNo ratings yet

- s13104 017 2406 2Document8 pagess13104 017 2406 2Clarissa Simon FactumNo ratings yet

- Dietary Diversity Score in Adolescents 20160605 27150 1rfwxwe With Cover Page v2Document6 pagesDietary Diversity Score in Adolescents 20160605 27150 1rfwxwe With Cover Page v2Huỳnh Điệp TrầnNo ratings yet

- Complementary and Alternative Medical Lab Testing Part 5: GastrointestinalFrom EverandComplementary and Alternative Medical Lab Testing Part 5: GastrointestinalNo ratings yet

- The Effectiveness of Using Two Stay Two Stray and Numbered Head Together in Teaching Writing Narrative TextDocument1 pageThe Effectiveness of Using Two Stay Two Stray and Numbered Head Together in Teaching Writing Narrative TextMuizzudin AzzaNo ratings yet

- Nursing Department Program Faculty of Nursing and Health University of Muhammadiyah SemarangDocument1 pageNursing Department Program Faculty of Nursing and Health University of Muhammadiyah SemarangMuizzudin AzzaNo ratings yet

- Reinforcement Technique and Variable y in This Study Is Students' Learning Motivation. DataDocument1 pageReinforcement Technique and Variable y in This Study Is Students' Learning Motivation. DataMuizzudin AzzaNo ratings yet

- Letters To The Editor: Posture TechniqueDocument3 pagesLetters To The Editor: Posture TechniqueMuizzudin AzzaNo ratings yet

- The Role of Shoe Design in Ankle Sprain Rates Among Collegiate Basketball PlayersDocument4 pagesThe Role of Shoe Design in Ankle Sprain Rates Among Collegiate Basketball PlayersMuizzudin AzzaNo ratings yet

- JSON - WikipediaDocument13 pagesJSON - WikipediadearbhupiNo ratings yet

- Subject: AEE Code: AU410705: UNIT-1 Automobile Electrical Systems and Electronics SystemDocument2 pagesSubject: AEE Code: AU410705: UNIT-1 Automobile Electrical Systems and Electronics SystemAniket PatilNo ratings yet

- Power 101Document29 pagesPower 101Mobile LegendsNo ratings yet

- 1Ø Service Manual: Engineered For LifeDocument76 pages1Ø Service Manual: Engineered For LifejewettwaterNo ratings yet

- Li ReportDocument47 pagesLi ReportRizal RizalmanNo ratings yet

- Surveying Lab 2.0Document41 pagesSurveying Lab 2.0omay12No ratings yet

- Acharya Nagarjuna University: Examination Application FormDocument2 pagesAcharya Nagarjuna University: Examination Application FormMaragani MuraligangadhararaoNo ratings yet

- Amu ClearanceDocument19 pagesAmu ClearanceEshetu GeletuNo ratings yet

- Light Emitting Diode PresentationDocument22 pagesLight Emitting Diode PresentationRetro GamerNo ratings yet

- OmniOMS Output GenerationDocument2 pagesOmniOMS Output Generationnitin.aktivNo ratings yet

- Literature Review Essay-2Document4 pagesLiterature Review Essay-2api-548944132No ratings yet

- Release NoteDocument10 pagesRelease NoteyusufNo ratings yet

- WSPD Pursuit PolicyDocument7 pagesWSPD Pursuit PolicyCBS 11 NewsNo ratings yet

- Garia - Wikipedia, The Free EncyclopediaDocument9 pagesGaria - Wikipedia, The Free EncyclopediaPradip DattaNo ratings yet

- Chapter 3 - Enterprise, Business Growth and SizeDocument110 pagesChapter 3 - Enterprise, Business Growth and Sizestorms.wells24No ratings yet

- G7 K1 Semi Detailed Lesson PlanDocument15 pagesG7 K1 Semi Detailed Lesson PlanJohn Carlo LucinoNo ratings yet

- Oviedo 2016Document15 pagesOviedo 2016Dernival Venâncio Ramos JúniorNo ratings yet

- AIEEE 2012 Information BrochureDocument53 pagesAIEEE 2012 Information Brochuresd11123No ratings yet

- Economic and Political Weekly Economic and Political WeeklyDocument3 pagesEconomic and Political Weekly Economic and Political WeeklyMoon MishraNo ratings yet

- Project-Orpheus A Research Study Into 360 Cinematic VRDocument6 pagesProject-Orpheus A Research Study Into 360 Cinematic VRjuan acuñaNo ratings yet

- Vlookup Index Match - StudentsDocument17 pagesVlookup Index Match - StudentsRahul DudejaNo ratings yet

- InsuranceDocument34 pagesInsuranceNguyen Phuong HoaNo ratings yet

- Fin TechDocument32 pagesFin Techkritigupta.may1999No ratings yet

- Dln2 Extender Package 2008-2009Document10 pagesDln2 Extender Package 2008-2009atfrost4638No ratings yet

- Chapter 16Document34 pagesChapter 16bings1997 BiniamNo ratings yet

- Seamless Technology: SM4-TL2 Single JerseyDocument6 pagesSeamless Technology: SM4-TL2 Single JerseyLewdeni AshenNo ratings yet