Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Formula de Pollo

Formula de Pollo

Uploaded by

Yazmin Azucena Torres JuárezOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Formula de Pollo

Formula de Pollo

Uploaded by

Yazmin Azucena Torres JuárezCopyright:

Available Formats

"cessful use of a chicken-based diet for the

: m e n t of severely malnourished children with

persistent diarrhea: A prospective, randomized study

iiiii!ii~

Samuel Nur/co, AID, dosdAlberto Garchz-Aranda, AID,Euyenia Fiahbein, RN, and

AIartha In& Pdrez-Ztiffiya, RD

Objective: To evaluate the efficacy of a chicken-based diet for the treatment of persistent diarrhea in severely malnourished children.

Stud}" design: Prospective, randomized, double-blind study that compared a chickenbased diet with elemental (Vivonex) and soy (Nursoy) diets. Hospitalized children with

third-degree malnutrition and persistent diarrhea, aged 3 to 36 months, were included.

Diets were isocaloric and given nasogastrically at 150 ml/kg per day in progressively

increasing concentrations.

Results: Fifty-six children were included (18 received Vivonex, 19 Nursoy, 19 chicken). They had a mean age of 6.4 _+4.4 months, a mean weight of 3604 _+1232 gm, and a

mean weight-for-age percentage of 51.4% _+7.2%. Sixty-four percent had associated

conditions on admission to the hospital. Forty-one children (73.2%) were successfully

treated (13 Vivonex, 13 Nursoy, 15 chicken). There were no differences in diarrheal

outcomes, and all groups had significant weight gain. Failure was independent of the

diet and was associated with the presence of infection on admission. There was a significantly higher nitrogen balance in the children from the chicken group (358.2 _+13

mg/kg per day) than in those receiving Vivonex (226.6 +_61) or Nursoy (291.4 _+111.6;

p < 0.05) groups.

C o n c l u s i o n s : The chicken-based diet was as effective as Vivonex or Nursoy. It is well

tolerated, inexpensive, and widely available and thus represents an effective and inexpensive alternative to the treatment of severely malnourished children with persistent

diarrhea. (J Pediatr 1997;131:405-12)

From the Departnwat of Pediatric GaaO'oenterologyand Nutrition Hospital l@mtil de Mdrico Federico Gdme;4Mexico CitN

d/fexico.

Supported in part b2- the Applied Diarrheal Disease Research Project at Harvard University, by means of a

cooperative agreement with the U.S. Agency for International Development, and in part by National Institutes

of Health grant T32-DK 07703.

Submitted for publication April 3, 1996; accepted Dec. 17, 1996.

Reprint requests: Samuel Nurko, MD, Pediatric Gastroenterology, Children's Hospital, 300 Longwood Ave.,

Boston, MA 02115.

~Dr. Nurko is now in the Combined Program in Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrifon, Children's Hospital,

Boston, Mass.

Copyright 9 1997 by Mosby-Year Book, Inc.

0022-3476/97/$5.00 + 0 9/21/79985

Persistent diarrhea confnues to be a major

health problem in developing countries 1"3

and is often associated with a deterioration

in nutritional state. 1'3'4The nutritional rehabilitation of children with PD and severe

malnutrition is difficult and usually requires

hospitalization 4 and specialized care. l's

Initially the introduction of parenteral nutrition improved the outcome of PD in these

children. 6'7 Recent studies have shown that

specialized enteral feeding during the diarrhea] episode results in improved nutritional outcomes. 1'4'8 Therefore the enteral administration of elemental and semielementat

diets, with supplementation with parenteral

nutrition when needed, has become the

standard therapy. 5-z'9 These specialized enteral feedings, however, are very expensive,

usually unpalatable, and not readily available in many areas of the world. 1,4,8

Recent work suggests that malnourished patients with PD may be capable of

tolerating more complex diets, 1'4'8 so efforts are being undertaken to find inexpensive, available, and culturally acceptable diets.l'8' 10,11 Because milk is not well

tolerated by children with PD when given

as a full diet, 1'4'12 alternatives have been

suggested. 1"4'8"10'1I Soy-based formulas

are still used extensively, but their efficacy continues to be controversial. 4'8

Chicken-based diets have been empirical-

405

THE JOURNAL OF PEDIATRICS

SEPTEMBER 1997

NURKO ETAL.

Table I. Composition of the diets at the maximum concentration

Study Design

DIETS

ly and successfully used for the treatment

of malnourished infants with PD when elemental or soy diets have not been available. 4'13-1s Chicken has the advantage of

being considered by mothers and health

personnel in Mexico 16'17 and other areas

of the world as a safe food for children

with diarrhea or malnutrition. 4'1a'14

Because the optimal nutritional therapy

for severely malnourished patients with

PD is still controversial, 1'4 we evaluated

the efficacy of a chicken-based diet for the

treatment of PD in severely malnourished

children.

METHODS

Patients

In this prospective, randomized, double-blind study a local chicken-based diet

was compared with both an elemental diet

(Vivonex Standard; Norwich Eaton) and

a soy-based formula (Nursoy; Wyeth

Laboratories) in the treatment of severely

malnourished hospitalized children with

PD.

406

The study was performed at the

Hospital Infantil de 1Vidxico Federico

Gdmez in Mexico City. Patients between

3 and 36 months of age hospitalized with

third-degree malnutrition of the marasmatic type with PD were included. Thirddegree malnutrition was defined by using

the Gdmez criteria for weight for age

(<60% of the National Center for Health

Statistics 50th percenfle), is PD was defined as three or more loose stools for 14

days or longer. 2

Patients with the following characteristics were excluded: exclusively breast

fed, chronic illness (e.g., acquired immunodeficieney syndrome, tuberculosis), congenital malformation, an abdominal condition that would preclude

enteral feedings, a severe condition requiring intensive care, or lack of parental

consent.

The protocol was approved by the local

ethical review committee and by the

Harvard School of Public Health Committee on the Use of Human Subjects in

Research. Informed consent was obtained

from all parents.

The mainstay of therapy for PD and severe malnutrition at the Hospital Infantil

de Mgxico has been the elemental diet

Vivonex Standard. 5 Vivonex contains

crystalline amino acids, glucose and glucose oligosaccharides, a small amount of

highly purified safflower oil, electrolytes,

minerals, micronutrients, and vitamins, s'9

For use in children with PD, we and others have shown that Vivonex is effective if

it is given in progressively increasing concentrations, starting at 150 ml/kg per day

in a concentration that provides 47.8

kcal/dl (12.5% weight/volume) and advancing slowly by 2.5% per day to a maximum concentration of 85.6 kcal/dl

(22.5% weight/volume) s'9 (Table I).

Sodium chloride and potassium chloride

were also added to the formula to ensure

administration of sodium, 4 mEq/kg per

day, and potassium, 3 mEq/kg per day. 5

The chicken-based diet was designed with

the use of tables of food composition 19'20

and consists of easily available and simple

ingredients: cooking oil, boiled chicken

breast, table sugar, and minerals. To prepare the chicken-based diet, we calculated

the total volume needed per day (150

ml/kg). At the maximum concentration

(Table I) the following ingredients per

deciliter of diet were used: 8 gm boiled,

comminuted chicken breast; 3 ml vegetable cooking oil; and 10.5 gm table

sugar. After these components were

blended together, the following minerals

were added: 5 ml calcium gluconate (10%

solution, PISA), 2.7 ml of dibasic sodium

phosphate (PISA, dibasic sodium phosphate), and 1.7 ml of magnesium sulfate

(10% solution, PISA). Sodium chloride

(0.gN solution) to achieve 4 mEq of sodium per kilogram of body weight per day

and potassium chloride to achieve 3

mEq/kg/day were also added. Finally,

boiled water was added to achieve the

total volume required.

The soyformula used was Nursoy, which

contains soy protein, coconut, safflower

and soy oils, sucrose, minerals, and vitamins. All diets were prepared in the pedi-

NURKO ET AL.

THE JOURNAL OF PEDIATRICS

Volume 13 I, Number 3

atric nutrition kitchen of the hospital

under the supervision of a trained nutritionist.

The study was designed to use Vivonex

as the standard against which the other

formulas were compared, so all three diets

were given nasogastrically at progressive

isocalorie concentrations. The maximum

concentration of the diets is shown in

Table I. Because of intrinsic differences in

diet composition, the percentage of total

calories provided as protein, carbohydrate, or fat varied (Table I).

PROTOCOL

Patients were randomly assigned to

treatment by using a table of random

numbers. Only the nutritionist who prepared the formula was aware of group assignment. The investigators, nurses, and

residents remained masked to the type of

diet because aluminum foil was used to

cover the formula bag and tubing.

On admission to the hospital, patients

were hydrated according to World Health

O r g a n i z a t i o n / U N I C E F guidelines with

the use of a standard glucose-electrolyte

solution. 21 Patients were then fasted

overnight. Hydration was maintained

during that time with intravenously administered fluids. The next morning the

assigned diet was started if the patient

was well hydrated and there were no

other contraindications to feeding. The

nasogastric tube was inserted by trained

nursing staff. The diet was started at the

lowest concentration at a volume of 150

ml/kg per day, and concentrations were

advanced every 48 hours. If no intolerance occurred, full concentration was

achieved by the ninth day (Table I). If

there was evidence of intolerance, the diet

concentration was either maintained or

decreased as follows: (1) It was kept unchanged if there was evidence of 2% or

3% positive reducing substances (before

or after hydrolysis) or if there was an increase in stool output of more than 50%

(>20 ml/kg). (2) It was reduced if Clinitest results showed 4% or if there was an

increase of 75% or more in the stool output (>20 m]/kg).

When full concentration of the diet was

achieved, it was maintained for an additional 7 days. Daily supplementation with

1 mg folie acid, 1 ml multivitamin (PolyVi-Sol), and elemental iron, 6 mg/kg, was

begun when the maximum concentration

was achieved. After 7 days of the maximum diet concentration, patients underwent a challenge with whole cow milk: we

administered half-strength whole cow

milk, 10 ml/kg, and advanced to fullstrength milk if tolerated. Milk-tolerant

patients continued their rehabilitation

with lactose-contalning formula or whole

milk, depending on the age. If patients

showed evidence of lactose malabsorption, as manifested by return of liquid

stools, with p H less than 5 and greater

than 2% reducing substances in the stool,

a milk-flee diet was instituted. After the

milk challenge, all patients restarted a

complete age-appropriate, complex-balanced diet, which was continued until discharge.

Cessation of diarrhea was defined as the

passage of formed stool not followed by

liquid stools for at least 24 hours.

Successful treatment was declared if the formula could be advanced to the highest

concentration and there was cessation of

the diarrhea at the end of the study. The

onset of nutritional recoverywas considered

to be when the diarrhea ceased and there

was consistent weight gain for at least 48

hours. Treatmentfai[are was declared if the

patient had 5% or more dehydration during the administration of the diet, if there

was clinical deterioration that precluded

further enteral therapy, if diarrhea persisted at the end of the study, or if the formula could not be advanced to full concentration.

When treatment was declared a failure,

the code was broken. If patients had been

receiving Nursoy or chicken, they were

started on a regimen of Vivonex. If the patients with treatment failure had originally been receiving Vivonex or were unable

to continue with enteral feedings, total

parenteral nutrition alone was initiated

and was then continued u n t l the patient

was stabilized and gaining weight. Continuous enteral feedings with Vivonex

were then added to the total parenteral

nutrition and advanced every 24 hours as

tolerated. Once patients achieved full enteral feedings, they continued to receive

Vivonex for another 2 weeks and nutritional rehabilitation continued as outlined

previously.

CLINICAL PROCEDURES

Nude weight was obtained on admission and daily thereafter. The posthydration weight, obtained on the morning of

the start of the feedings, was considered

the baseline weight. Weights were obtained at the same time every morning

with an electronic scale (ScalesTronLx,

Wheaton, Ill.) and were accurate to at

least 10 gm. Recumbent length was obtained with a specially designed board on

admission, at the end of 2 weeks, and before discharge. All measurements were

obtained by trained nutritionists, and

their accuracy was validated before the

beginning of the study.

All patients had baseline laboratory values obtained at admission; laboratory

studies included complete blood cell

count, electrolyte concentrations, D-xylose concentration, stool and urine cultures, and stool tests for ova and parasites.

Blood culture specimens were obtained

only if indicated.

All intake and output were recorded.

Patients, both male and female, were

placed on metabolic beds or cots for separation of stool from urine. 5 To confirm

Successful separation of stool and urine in

girls, we performed a separate analysis

for all the variables associated with the

stool collection at the end of the study.

No differences between sexes were found

(data not shown), so all data were pooled.

A 72-hour nitrogen balance test was performed at the end of the second week,

starting 4 days after the maximum diet

concentration had been achieved. The

beginning and end of the stool collection

time were marked by the fecal excretion

of orally administered activated charcoal. s The nitrogen balance was measured by the micro Kjeldahl method. 22

Tests for p H and reducing and nonreducing substances in stool were performed

daily.

407

NURKO ET AL.

THE JOURNAL OF PEDIATRICS

SEPTEMBER 1997

Table II. Patient characteristics at time of admission

INFECTION ON ADMISSION OR

DURING HOSPITALIZATION

Systemic infection was suspected and

treated with broad-spectrum intravenously

administered antibiotics if there was a general ill appearance with any of the following signs: temperature instability, hypotension, hypoglycemia, or acidosis despite

adequate hydration. Otitis media, urinary

tract infections, and pneumonia were treated with appropriate antibiotics. Children

with dysentery received trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole. 4 Children infected with

Giardia larr~lia received metronidazole.

Statistical analysis

We calculated that a sample size of 20

children per group would be needed if we

408

assumed a power of 0.80, an alpha of 0.05,

and a difference of 30% in the duration of

diarrhea. The statistical analysis was performed with the use of SPSS/PC software

and Epi-Info software, version 5.01.

Significance was assumed when p was less

than 0.05. Descriptive analyses were used

to define the presenting characteristics.

Multivariate and repeated-measures

analyses of variance were used to establish differences between the three groups.

W h e n necessary, transformation of the

data was done to fulfill the assumption of

normally distributed residuals. Survival

analysis was used to compare the duration

of the diarrhea. Chi-square tests were

used for categorical variables, and the

Fisher Exact Test was used whenever

there were cells with small sizes. VaLues

are expressed as mean _+SD.

RESULTS

Admission Characteristics

A total of 60 patients were initially enrolled in the study. Four were later excluded: two in the Vivonex group (one

with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome, one who died before initiation of

feedings), one in the Nursoy group (the

patient had primary renal insufficiency),

and one in the chicken group (the patient

had acute renal failure as a result of dehydration soon after admission). For the

other 56 patients, Vivonex was given to

THE JOURNAL OF PEDIATRICS

NURKO ET AL.

Volume 13 I, Number 3

18, Nursoy to 19, and chicken to 19. Their

initial clinical and laboratory characteristics are Shown :in Table II. Sixty-four percent of the patients had associated conditions at the time of admission (Table II).

Fifty percent had a nongastrointestinal infection, and 14.3% had a gastrointestinal

infection.

There were no significant differences

between the three groups.

Table I I L Main outcome characteristics for the 41 patients who successfully completed

the stud;/

Outcome

A successful outcome was seen in 41 patients (73.2%): 13 (72.2%) with Vivonex,

13 (68.4%) with Nursoy, and 15 (78.9%)

with chicken (not significant). During the

study, 34 (60.7%) of the 56 patients had

some evidence of formula intolerance: 14

(77.8%) of the patients receiving Vivonex,

11 (57.9%) Nursoy, and 9 (47.4%) chicken (NS). The intolerance was transient in

19 (56%) of 34 patients. The other 15

(44%) (5 receiving Vivonex, 6 Nursoy,

and 4 chicken) had treatment failure. The

mean time from initiation of the diet to

failure was 85.6 72 hours (60.6 45.7

hours with Vivonex, 98.5 99.9 with

Nursoy, and 97.5 99.9 with chicken)

(NS). Intestinal pneumatosis developed

in 7.14% of the patients (2 patients receiving Vivonex, 1 Nursoy, and 1 chicken). One of the failures in the Nursoy

group was shown to be a result of allergy

to the formula.

Five patients (8.9%) died: two who had

been receiving Vivonex, 1 Nursoy, and 2

chicken (NS). The patients died of intestinal pneumatosis (2), central line-associated sepsis (2), and bacterial sepsis

(K[ebsfe/[apneanwn/ae)early in the hospital

course (1).

The other 10 patients with treatment

failure were successfully managed, and

their mean stay was 50 30 days. Total

parenteral nutrition was required in 7 of

the 10 patients, and 9 were eventually discharged home on a milk-containing diet

regimen. The other was discharged on a

soy- and milk-free diet regimen because of

allergy.

Diarrhea

The mean fecal output per kilogram of

body weight and the number of bowel

movements per kilogram per day in the

first 24 hours were similar in all groups

(Table II). There were also no differences

in the mean stool output per kilogram per

day or in the day of cessation of diarrhea

in comparison with the 41 patients who

successfully completed the study (Table

III).

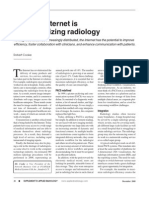

The Figure shows the results of the survival analysis done to compare the daily

probability of continuing with diarrhea

among the three groups. There were no

differences between groups, and the median duration of diarrhea, estimated by

the analysis, was 8.8 days for Vivonex,

5.67 days for Nursoy, and 7.3 days for

chicken.

Nutritional Outcome

The mean number of total calories per

kilogram of body weight per day ingested

by each group after the full diet was tolerated was similar: 115.2 8.3, 111.3 9.1,

and 116.0 9.6 for the Vivonex, Nursoy,

and chicken groups, respectively. There

was a significant difference in the amount

of protein per kilogram per clay ingested

after the full diet was tolerated: 2.4 0.2

gm/kg per day, 3.4 0.3 gm/kg, and 3.5 _+

0.4 gm/kg with Vivonex, Nursoy, and

chicken, respectively (p < 0.05).

Table III shows the outcome characteristics of those patients successfully treated. There was a significant weight gain in

all groups and no differences between

groups.

All patients in each group had an apparent positive nitrogen balance and a

similar percentage of absorption, percentage of retention, and biologic values.

There was a statistically significant higher

nitrogen balance (p < 0.02) and a tendency toward a higher number of children

with nutritional recovery in the chicken

group (NS).

Laboratory Tests

The serum albumin concentration decreased significantly in the Nursoy group

(from 3.5 0.6 to 3,l

grrdcll;p < 0.05),

whereas it did not change significantly in

the other groups: 3.3 0.6 to 3.2 0.5

409

THE JOURNALOF PEDIATRICS

NURKO ET AL.

SEPTEMBER 1 9 9 7

A sodium concentration less than 130

mmol/L (relative risk, 3.07; 95% confidence limits, 1.41 to 6.65) and the presence of associated infections (RR, 3.61;

95% CL, 1.1 to 14.42), particularly infection with Cryptospor~ium (RR, 4.15; 95%

CL, 1.58 to 6.67) or pneumonia (RR,

3.25; 95% CL, 1.53 to 6.9), were identified

as important factors associated with treatment failure.

1.0

VIVONEX

"'. \ \

O.B

NUNSOY

\

.

CHICKEN

\\

-

0.6

\

DISCUSSION

\\

"0

~

0.4

\

m

oe-4

o,

~ ~

0.2

10

0.0

0

""

12

14

16

Days since admission

F~ure. Probabilityof continuingdiarrhea since admission:a comparisonbetween the diets.

gngdl with Vivonex, and 3.0 + 0.7 to 3.3 +

0.3 gm/dl with chicken. There were no

electrolyte abnormalities noted in children

of either group, and there were .no other

significant differences in laborato W values between formulas (data not shown).

At the end of the study, children receiving Vivonex had a significantly higher DxNlose concentration (34.6 _+ 13.7 mg/dl)

than those receiving Nursoy (23.8 _+ 10.1

mg/dl) or chicken (23.1 _+11.5 mg/dl) (0 <

0.05)

Milk Tolerance Test

Intolerance was present in 7 patients

(17%): in none of the 13 patients in the

Vivonex group, in 3 (23.07%) of 13 in the

Nursoy group, and in 4 (21.1%) of 15 in

the chicken group. Those with milk intolerance had a lower admission weight

(2900.83 _+ 289.24 vs 3659.28 _+ 1258.91

gm; p < 0.004), a tendency to be younger

(3.91 +- 2.80 vs 6.64 + 4.1 months; p <

410

0.07), and a lower D-xylose concentration

at baseline (17.00 ~_2.09 vs 23.28 10.6

mg/dl; p < 0.004) than those who tolerated

milk. There was no difference in the D-xylose level at the end of the study when

both groups were compared (20.66 _+8.61

vs 27.89 +_13.2 mg/dl).

Risk Factors

There were significant differences (o <

0.05) between patients with treatment

success and those with treatment failure

with regard to the following admission

characteristics: albumin concentration

(3.2 _+0.6 vs 2.9 _+0,4 gm/dl), sodium concentration (138.4 _+ 6.2 vs 133.5 _+ 7.9

mmol/L), and the incidence of associated

infections (56.1% vs 86.7%). There were

also differences in stool output on the second (20.9 _+19.8 vs 47.4 +_33.9 ml/kg) and

third (16.7 +_ 16.5 vs 54.0 _+40.3 ml/kg)

days. No other significant differences

were found.

We have shown in this study that the

use of a locally available chicken-based

diet is at least as effective as elemental and

soy-based diets in the hospital treatment

of severely malnourished children with

PD. The main components of the chicken-based diet are easily available, are culturally acceptable, and are inexpensive. 16'17 Chicken-based diets were also

previously used as an alternative for the

treatment and rehabilitation of children

with malnutrition 1'10'13'14 and acute diarrhea. 15'16 However, use of this diet in children with P D has been limited. 1'11

This study included a difficult population that is frequently excluded from

other clinical trials. 1'8'13 Severely malnourished children with P D usually have

a high mortality rate and high treatment

failure rates. There can be up to a 17-fold

increase in the mortality rate, l'a'la'ya and it

has been suggested that approximately

49% (range, 23% to 62%) of diarrhea-associated deaths result from P D and malnutrition. 1'a'13 The mortality rate found in

this study (8.9%) compares favorably

with rates previously reported in the literature, la'93 We also did not find any differences in outcome when comparing the

treatment failure rates of those children

ha~ng the most extreme levels of malnutrition (weight-for-age percentage, <40%)

with the rates of less malnourished children. We confirmed that children with superimposed infections are at a higher risk

of treatment failure, which emphasizes

the need to look for and control superimposed infections at the time of admission

and nutritional rehabilitation. 13'25

As in previous studies, the diets were

NURKO ET AL.

THE JOURNAL OF PEDIATRICS

Volume 13 I, Number 3

given at a fixed volume and the caloric

density was advanced slowly. 5'6'9'2a'24

Sixty percent of children acquired some

signs of intolerance while the diet regimens were being advanced. These signs

were most likely related to carbohydrate

malabsorption, 12 and a good correlation

between fecal carbohydrates and total

fecal output has been shown. 25 O f the

three diets tested, Vivonex has a much

higher carbohydrate concentration (Table

I), mainly of oligosaecharides, which

probably accounts for the higher incidence of transient intolerance seen in

those patients. &25 Transient intolerance

was also seen in children receiving chicken or soy, which suggests that malnourished infants with PD frequently have

transient intolerance to other sugars. 25

Caution should be exercised in the treatment of those patients in whom increasing

stool outputs appear in the first and second day, because they may be at risk of

failure. In those children, a slower advancement of the dietary regimen may be

necessary.

A potential shortcoming of this study is

the difference in the macronutrient composition of the diets (Table I). In Vivonex, the

majority of the calories are provided by

carbohydrate and the protein content is

lower, &26"27providing only about 8% of

total calories. Previous studies confirm that

children receiving 6.70/0 of energy as protein achieved a slow compensatory

growth, 24"27and it has been shown recently that, in recovering malnourished infants,

there were no differences in growth when

formulas with 5.5%, 6.70/0, and 8.0% protein calories were compared. 28 Furthermore other studies have documented the

adequacy of Vivonex for growth and for

treatment of PD. 5'9 It is then possible that

the hydrolyzed amino acids are better absorbed. 5'9 This difference in protein content may partially explain why children on

the chicken-based diet regimen had a significantly higher nitrogen balance than

those receiving Vivonex.

The protein and caloric intakes were

similar in children receiving chicken or

soy feedings. The higher nitrogen balance

in those receiving chicken indicates that

chicken protein has a higher biologic

value than soy. Chicken has a low osmolarity, a better amino acid score, and a

higher degree of digestibility and bioavailability. 11'14'24We also found a significant

decrease in the serum albumin concentration in patients who received Nursoy despite a positive nitrogen balance. These

data suggest that the protein status and

lean body mass of malnourished patients

fed soy formulas may be deteriorating

slowly despite apparently adequate nitrogen retention. 29 It is therefore possible

that protein intake with Nursoy was inadequate to allow more rapid accretion of nitrogen at higher energy intakes. 29 Other

problems have also been associated with

the use of soy formulas in these patients.

Some authors have found that nearly 50%

of hospital-referred patients with PD do

not recover from diarrhea a week after the

introduction of a soy formula. 8 It has also

been suggested that soy-containing diets

may produce transient sensitivity and

subtle mucosal abnormalities in the intestinal mucosa of children with diarrhea,

with the potential for increasing the severity of their illness.16

Like Vivonex, 5 the chicken diet requires the addition of minerals. These

mineral additions make preparation suitable only in health care facilities, a factor

that does not represent a major obstacle

for severely malnourished children with

PD, who usually require hospitalization. 4

In the community the treatment of children with PD needs to include continued

feeding with locally available, inexpensive, and effective nutrients. I It is possible

that the chicken-based diet may be another alternative once the usual therapies

have failed.

All diets were administered continuously via nasogastric infusion, a method of

feeding that has been shown to have a

beneficial effect in control of diarrhea, nutrient absorption, nitrogen balance, and

weight gain in children with PD. <8'11'1a

Two main limitations of the nasogastric

route need to be mentioned. The technical

aspects of the placement and management

of the feedings requires specialized personnel and equipment, s More importantly the child has no control over the

amount of food that is being ingested,

which increases the risk of overzealous

refeeding or intolerance 27 and, later, the

risk of limiting the amount of nutrients in

comparison with ad lib oral intake.

Although the use of milk as the sole nutrient for children with P D has been

shown to be deleterious, 12 the question

that remains unanswered is when milk

can safely be reintroduced into the diet of

these children. We found that 83% of patients who successfully finished the study

were able to tolerate a full milk load at

least after 2 weeks of nutritional rehabilitation. Those children who were milk intolerant at the end of the study had an initial lower admission weight, were

younger, and had a lower D-xylose concentration, which suggests that their initial mueosal damage was greater. 6 Most

likely the intolerance was related to lactose malabsorption, although we cannot

exclude the possibility of intolerance to

milk protein.

In summary, severely malnourished

children with P D can be successfully

managed with a chicken-based diet.

These children were able to tolerate a

complex diet, achieve positive nitrogen

balance, and show weight gain. There was

no advantage to the use of an elemental or

a soy-based diet. Clear benefits of the

chicken-based diet include good tolerance, low cost, availability, and cultural

acceptance. Therefore the chicken-based

diet represents a good alternative for the

treatment of hospitalized children with severe malnutrition and PD.

We express special thanks to the nurses~ residents, and laboratmy personnel of the nutrition

~vardat the Hospital lnfantil de ~Ilxico for their

help in the pe,formanee o/this study, in p~rtieula6 we thank Gina Toussaint, Dr. Liliana

Worona, Dr. Alejandra Consnelo, Rosaura

P~'ez, Sarah Arvizu, and Aloniea Covarrubias.

We are indebted to all the personnel of the

Applied Dialv'heal Disease Research Projectfor

rhea" support during the poformance of the

study. We also thank DI: Laurie Fishman and

DI: Alan Leiehtnerfor their o'itical reviewof the

manuscript andfor lheir helpful su~gestions.

REFERENCES

1. Bhutta ZA, Hendricks KM. Nutritional

management of persistent diarrhea in child-

411

THE JOURNALOF PEDIATRICS

SIFPTEI"IBI:R1997

NURKO ET AL.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

8.

9.

10.

412

hood: a perspective from the developing

world, d Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 1996;

22:17-37.

Persistent diarrhea in children in developing countries. Memorandum from a World

Health Organization meeting. Bull WHO

1988;66:707-17.

Fauvean V, Henry FJ, Briend A, Yunus M,

Charkraborty d. Persistent diarrhea as a

cause of childhood mortality in rural

Bangladesh. Acta Pediatr 1992;381(Suppl):

12~4.

Bhan MK, Arora NK, Singh KD. Management of persistent diarrhea during infancy

in clinical practice. Indian d Pediatr 1991;

58:769-74.

Vega Franco L, Carbajal-Ouzmgm A,

Garcfa-Aranda JA. Alimentacidn enteral

continua en nifios lactantes empleando una

dicta elemental. Bol Med Hosp Infant Mex

1982;39:651-8.

Orenstein S. Enteral vs parenteral therapy

for intractable diarrhea of infancy: a

prospective randomized trial. J Pediatr

1986; 109:277-86.

Kleinman RE, Galeano NE Ghishan E

Lebenthal E, Sutphen J, Ulshen MH.

Nutritional management of chronic diarrhea and/or malabsorption. J Pediatr

Gastroenterol Nutr 1989;9:407-15.

Bhutta ZA, Molla AM, Issani Z,

Badruddin S, Hendrieks K, Snyder JD.

Dietary management of persistent diarrhea

and malnutrition: comparison of a traditional rice-lentil-based diet with soy formula.

Pediatrics 1991;88:1010-8.

Sherman ,JO, Hamty CA, Khachadurian

AK. Use of an oral elemental diet in infants

with severe intractable diarrhea. J Pediatr

1975;86:518-23.

Roy SK, Haider R, Akbar MS, Alam AN,

Khatum M, Eeckels R. Persistent diarrhea:

clinical efficacy and nutrient absorption

with a rice-based diet. Arch Dis Child 1990;

65:294-7,

11. Godard C, Bustos M, Mufioz M, Nussle D.

Value of a chicken-based formula for

refeeding of children with protracted diarrhea and malnutrition in a developing country. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 1989;9:

473-90.

12. Penny ME, Paredes E Brown KH. Clinical

and nutritional consequences of lactose

feeding during persistent postenterifis diarrhea. Pediatrics 1989;84:835-44.

13. Maffei HV, Padula NN, Annicchino GP,

Ferrari GF, Goldberg TB. Nutritional management and weight changes during hospitalization of Brazilian infants with diarrhea:

primary reliance on oral feeding or continuous nasogastrie drip with locally made,

modulated minced chicken formula, d Trop

Pediatr 1990;56:240-6.

14. Larcher E Shepherd R, Francis DEM,

Harries JT. Protracted diarrhea in infancy.

Arch Dis Child 1977;52:597-605.

15. Romer H, Guerra M, Pina ,JM,

Urrestarazu MI, Garcia D, Blanco ME.

Realimentafion of dehydrated children with

acute diarrhea: comparison of cow's milk to

a chicken-based formula, d Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 1991;13:46-51.

16. Maulrn-Radovgm I, Brown KH, Acosta

MA, Fern~indez-Varela H. Comparison of a

rice-based, mixed diet versus a lactose-free,

soy-protein isolate formula for young children with acute diarrhea. ,J Pediatr

1994; 125:699-706.

17. Martfnez-Salgado H, Saueedo G. Mothers'

perceptions about childhood diarrhea in

rural Mexico. d Diarrheal Dis Res

1991;9:235-43.

18. Gomez E Ramos Galvan R, Cravioto J,

Frenk S. Malnutrition in infancy and childhood, with special reference to kwashiorkor. Adv Pediatr 1955;7:131-55.

19. Chavez M, Hernandez M, Roldan S.

Tablas de valor nutritivo de los alimentos

de mayor consumo en Mexico. In:

Comision National de Alimentaeion, edi-

20.

21.

22.

25.

24.

25.

26.

27.

28.

29.

tors. Institnto Nacinnal de la Nutricion;

1992.

Composition of Foods [Agricultural

Handbook 8]. Washington (DC): U.S.

Department of Agriculture; Oct 1975.

The management of diarrhea and use of

oral rehydration therapy. Geneva: World

Health Organization; 1985.

Henry RJ. Clinical chemistry principles

and techniques. New York: Harper & Row;

1964.

MaeLean WC, Romafia GL, Massa E,

Graham GG. Nutritional management of

chronic diarrhea and malnutrition: primary

reliance on oral feeding. J Pediatr 1980;

97:316-23.

Brown KH. Appropriate diets for the rehabilitation of malnourished children in the

community setting. Acta Pediatr Scand

1991;374(Suppl):151-9.

Lifschitz C, Carrazza F. Effect of formula

carbohydrate concentration on tolerance

and maeronutrient absorption in infants

with severe chronic diarrhea. J Pediatr

1990; 117:578-85.

Field CR, Schoeller DA, Brown KH. Body

composition of children recovering from severe protein-energy malnutrition at two

rates of catch-up growth. Am ,J Clin Nntr

1989;50:1266-75.

Whitehead RG. Protein and energy requirements of young children living in the

developing countries to allow for catch-up

growth after infections. Am J Ctin Nutr

1977;50:1645-7.

Graham GG, MacLean WC, Brown KH,

Morales E, Lembcke ,J, Gastanaduy A.

Protein requirement of infants and children: growth during recovery from malnutrition. Pediatrics 1996;97:499-505.

MacLean WC, Graham GG. The effect of

energy intake on nitrogen content of

weight gained by recovering malnourished infants. Am J Clin Nutr 1980;55:

905-9.

You might also like

- CPG AbortionDocument40 pagesCPG AbortionKatharine Nerva75% (12)

- Emergency LACTOGEN Recover HPDocument27 pagesEmergency LACTOGEN Recover HPMuhammad ShahzadNo ratings yet

- Examination of The Newborn An Evidence Based Guide PDFDocument2 pagesExamination of The Newborn An Evidence Based Guide PDFPhilNo ratings yet

- NCP Back PainDocument2 pagesNCP Back PainLouis Roderos100% (9)

- Oppositional Defiant DisorderDocument2 pagesOppositional Defiant DisorderNikhil MohanNo ratings yet

- Effectiveness of The Bobath Concept in The Treatment of Stroke: A Systematic ReviewDocument15 pagesEffectiveness of The Bobath Concept in The Treatment of Stroke: A Systematic ReviewAfrizal BintangNo ratings yet

- Nutritional Therapy For Infants With Diarrhea Lif Schitz 1990Document10 pagesNutritional Therapy For Infants With Diarrhea Lif Schitz 1990Kristina Joy HerlambangNo ratings yet

- Contoh CA - CONSORTDocument15 pagesContoh CA - CONSORTdwie2254No ratings yet

- Parenteral Nutrition Patients: ObstetricDocument14 pagesParenteral Nutrition Patients: ObstetricAripinSyarifudinNo ratings yet

- J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr - 2022 - Thomassen - An ESPGHAN Position Paper On The Use of Low FODMAP Diet in PediatricDocument13 pagesJ Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr - 2022 - Thomassen - An ESPGHAN Position Paper On The Use of Low FODMAP Diet in PediatricDayana FajardoNo ratings yet

- Nutrient Intake Milk RestrictedDocument7 pagesNutrient Intake Milk RestrictedfffreshNo ratings yet

- Management of Acute Gastroenteritis in Young Children A Synopsis of The American Academy of Pediatrics' Practice Parameter On TheDocument5 pagesManagement of Acute Gastroenteritis in Young Children A Synopsis of The American Academy of Pediatrics' Practice Parameter On TheAbdul Ghaffar AbdullahNo ratings yet

- Nutr Clin Pract 2014 Asfaw 192 200Document10 pagesNutr Clin Pract 2014 Asfaw 192 200Iván OsunaNo ratings yet

- 1968 Long-Term Total Parenteral Nutrition With Growth, Development, and Positive Nitrogen Balance. SURGERYDocument4 pages1968 Long-Term Total Parenteral Nutrition With Growth, Development, and Positive Nitrogen Balance. SURGERYChristine ChambersNo ratings yet

- Nutritional Management of Acute Diarrhea: Global Issues in Pediatric NutritionDocument5 pagesNutritional Management of Acute Diarrhea: Global Issues in Pediatric NutritionKristina Joy HerlambangNo ratings yet

- 191337-Article Text-784455-2-10-20200103Document10 pages191337-Article Text-784455-2-10-20200103Fitri WulandariNo ratings yet

- Dairy Products How They Fit in Nutritionally Adequate DietsDocument7 pagesDairy Products How They Fit in Nutritionally Adequate DietsAMNA KHAN FITNESSSNo ratings yet

- EugrDocument5 pagesEugrFlaming NbNo ratings yet

- Application and Hazards of Total Parenteral: Nutrition InfantsDocument6 pagesApplication and Hazards of Total Parenteral: Nutrition InfantsVanessa NavarroNo ratings yet

- Usage Guidelines Please Refer To Usage Guidelines at or Alterna-Tively ContactDocument22 pagesUsage Guidelines Please Refer To Usage Guidelines at or Alterna-Tively ContactnettaNo ratings yet

- Gut / Enteral Feeding in Pediatric PatientDocument31 pagesGut / Enteral Feeding in Pediatric PatientUtami Adma NegaraNo ratings yet

- Is It Possible To Increase Weight and Maintain The Protein Status of Debilitated Elderly Residents of Nursing Homes?Document10 pagesIs It Possible To Increase Weight and Maintain The Protein Status of Debilitated Elderly Residents of Nursing Homes?Han BurhanNo ratings yet

- Jurnal Bing 1Document7 pagesJurnal Bing 1agung handalanNo ratings yet

- 2 ESPEN-ESPGHAN-ECFS Guidelines On Nutrition Care For Infants Children and Adults With Cystic FibrosisDocument21 pages2 ESPEN-ESPGHAN-ECFS Guidelines On Nutrition Care For Infants Children and Adults With Cystic FibrosisAmany SalamaNo ratings yet

- NPT en PediatriaDocument22 pagesNPT en PediatriaFernanda Sanchez LozanoNo ratings yet

- PICU NutritionDocument12 pagesPICU Nutritionmatenten100% (1)

- Stunting Mesir PDFDocument9 pagesStunting Mesir PDFRina HudayaNo ratings yet

- Early Total Enteral Feeding in Stable Very Low Birth Weight Infants: A Before and After StudyDocument7 pagesEarly Total Enteral Feeding in Stable Very Low Birth Weight Infants: A Before and After StudySupriya M A SuppiNo ratings yet

- Macronutrient Content and Food Exchanges For 48 Greek Mediterranean DishesDocument10 pagesMacronutrient Content and Food Exchanges For 48 Greek Mediterranean DishesΆννα ΠαπαδάκουNo ratings yet

- NutritionDocument27 pagesNutritionjoke clubNo ratings yet

- JN 212308Document8 pagesJN 212308Ivhajannatannisa KhalifatulkhusnulkhatimahNo ratings yet

- Regular Egg Consumption at Breakfast by Japanese Woman University Students Improves Daily Nutrient Intakes: Open-Labeled ObservationsDocument7 pagesRegular Egg Consumption at Breakfast by Japanese Woman University Students Improves Daily Nutrient Intakes: Open-Labeled ObservationsLeena MuniandyNo ratings yet

- Parenteral Nutrition Slide SetDocument198 pagesParenteral Nutrition Slide SetMashal ZehraNo ratings yet

- Probiotics Calcium and Acute Diarrhea A Randomize-Wageningen University and Research 231281Document178 pagesProbiotics Calcium and Acute Diarrhea A Randomize-Wageningen University and Research 231281FarhaNurmiatiariZainNo ratings yet

- Jurnal PubmedDocument5 pagesJurnal PubmedFatah Jati PNo ratings yet

- IYCF - MAM Recipes by World Food Programme (2020)Document47 pagesIYCF - MAM Recipes by World Food Programme (2020)Jewelle Anne Estanilla LimenNo ratings yet

- S 0007114507812037 ADocument9 pagesS 0007114507812037 AZainul AnwarNo ratings yet

- Nna en November09Document3 pagesNna en November09Agus WijataNo ratings yet

- Enteral Nutrition: Sanja KolačekDocument5 pagesEnteral Nutrition: Sanja KolačekManuela MontesNo ratings yet

- Espghan 2015 - Abstracts JPGN FinalDocument963 pagesEspghan 2015 - Abstracts JPGN FinalAdriana RockerNo ratings yet

- DocumentDocument8 pagesDocumentnavali rahmaNo ratings yet

- The Effect of Thickened-Feed Interventions On Gastroesophageal RefluxDocument13 pagesThe Effect of Thickened-Feed Interventions On Gastroesophageal Refluxminerva_stanciuNo ratings yet

- 275-Article Text-1818-1-10-20230112Document6 pages275-Article Text-1818-1-10-20230112Syanadia AndrianiNo ratings yet

- A Randomized, Double-Blind, and Placebo-Controlled Trial of Chinese Herbal Medicine in The Treatment of Childhood ConstipationDocument8 pagesA Randomized, Double-Blind, and Placebo-Controlled Trial of Chinese Herbal Medicine in The Treatment of Childhood ConstipationJovie Anne CabangalNo ratings yet

- Prolonged Breast-Feeding: No Association With Increased Risk of Clinical Malnutrition in Young Children in Burkina FasoDocument10 pagesProlonged Breast-Feeding: No Association With Increased Risk of Clinical Malnutrition in Young Children in Burkina FasoranihajriNo ratings yet

- Enteral and Parenteral Nutrition SeminarDocument20 pagesEnteral and Parenteral Nutrition SeminarAmin AksherNo ratings yet

- Pulse Crop Effects On Gut Microbial Populations, Intestinal Function, and Adiposity in A Mouse Model of Diet-Induced Obesity John N. McginleyDocument40 pagesPulse Crop Effects On Gut Microbial Populations, Intestinal Function, and Adiposity in A Mouse Model of Diet-Induced Obesity John N. Mcginleyzora.mendez637100% (9)

- PYMS TamizajeDocument6 pagesPYMS TamizajeKevinGallagherNo ratings yet

- Consumption of Ready-Made Meals and Increased Risk of ObesityDocument8 pagesConsumption of Ready-Made Meals and Increased Risk of ObesityEnik guntyastutikNo ratings yet

- The Use of Home-Based Therapy With Ready-toUse Therapeutic Food To Treat Malnutrition in A Rural Area During A Food CrisisDocument4 pagesThe Use of Home-Based Therapy With Ready-toUse Therapeutic Food To Treat Malnutrition in A Rural Area During A Food Crisismirfanjee89No ratings yet

- Maternal and Early-Life Nutrition and HealthDocument4 pagesMaternal and Early-Life Nutrition and HealthTiffani_Vanessa01No ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S0002916523463034 MainDocument13 pages1 s2.0 S0002916523463034 Maincarlos santamariaNo ratings yet

- Jurnal 2 AnakDocument5 pagesJurnal 2 AnakHafich ErnandaNo ratings yet

- Journal of Nutritional ScienceDocument11 pagesJournal of Nutritional ScienceDipo YudistiraNo ratings yet

- Nutrients 15 02244Document14 pagesNutrients 15 02244rafrejuNo ratings yet

- Improved Nutrition Delivery and Nutrition Status in Critically Ill Children With Heart DiseaseDocument9 pagesImproved Nutrition Delivery and Nutrition Status in Critically Ill Children With Heart DiseasedaindesNo ratings yet

- 2633-Article Text-21183-2-10-20201019Document4 pages2633-Article Text-21183-2-10-20201019ariani khikmatul mazidahNo ratings yet

- Jurnal PJJ WordDocument21 pagesJurnal PJJ WordnanamirNo ratings yet

- Dietary Guidelines For The Breast-Feeding WomanDocument7 pagesDietary Guidelines For The Breast-Feeding Womanvicky vigneshNo ratings yet

- Clinical Research: Outcomes of Early Nutrition Support in Extremely Low-Birth-Weight InfantsDocument6 pagesClinical Research: Outcomes of Early Nutrition Support in Extremely Low-Birth-Weight InfantsgianellaNo ratings yet

- 10 1016@j Arcped 2019 09 001Document9 pages10 1016@j Arcped 2019 09 001nta.gloffkaNo ratings yet

- Position Paper Ready-To-Use Therapeutic Food For Children With Severe Acute Malnutrition June 2013 PDFDocument4 pagesPosition Paper Ready-To-Use Therapeutic Food For Children With Severe Acute Malnutrition June 2013 PDFEmmanuel DekoNo ratings yet

- Lactose Intolerance Among Severely Malnourished Children With Diarrhoea Admitted To The Nutrition Unit, Mulago Hospital, UgandaDocument9 pagesLactose Intolerance Among Severely Malnourished Children With Diarrhoea Admitted To The Nutrition Unit, Mulago Hospital, UgandaArsy Mira PertiwiNo ratings yet

- Parenteral Nutrition Objectives For Very Low Birth Weight Infants: Results of A National SurveyDocument9 pagesParenteral Nutrition Objectives For Very Low Birth Weight Infants: Results of A National SurveyjlionelmoNo ratings yet

- IJCD RubberdamDocument13 pagesIJCD RubberdamAyik DarkerThan BlackNo ratings yet

- S. Woolley - Jehovah's Witnesses in The Emergency Department: What Are Their Rights?Document3 pagesS. Woolley - Jehovah's Witnesses in The Emergency Department: What Are Their Rights?Marco Aurélio Vogel Gomes de MelloNo ratings yet

- Applied Radiology Featured Article (Via Radrounds)Document3 pagesApplied Radiology Featured Article (Via Radrounds)radRounds Radiology NetworkNo ratings yet

- Military NursingDocument6 pagesMilitary Nursingdwirinanti90215No ratings yet

- (Questions For The Lion Tamer) by JCDocument135 pages(Questions For The Lion Tamer) by JCAriana SălăjanNo ratings yet

- KSJ409 Assignment - School (Hanna Sui J Holy Innocents High School)Document8 pagesKSJ409 Assignment - School (Hanna Sui J Holy Innocents High School)HANNA SUI WEE CHINGNo ratings yet

- Answer 1Document8 pagesAnswer 1aisyah andyNo ratings yet

- WI Medication AdministrationDocument11 pagesWI Medication AdministrationVin BitzNo ratings yet

- Febrile Seizures, Febrile Seizure Plus, First Unprovoked Seizure WebinarDocument45 pagesFebrile Seizures, Febrile Seizure Plus, First Unprovoked Seizure WebinarTun Paksi Sareharto100% (1)

- Emergency Neurological Life Support Subarachnoid Hemorrhage: Last Updated: 19-Mar-2016Document22 pagesEmergency Neurological Life Support Subarachnoid Hemorrhage: Last Updated: 19-Mar-2016michaelNo ratings yet

- Triglyceride To High Density Lipoprotein.17 PDFDocument7 pagesTriglyceride To High Density Lipoprotein.17 PDFkiran MushtaqNo ratings yet

- Deficit Vo. NCPDocument4 pagesDeficit Vo. NCPThessabelles Ebuen-PeñaNo ratings yet

- Accommodation Management 5th Sem. Notes by Kirti PuriDocument25 pagesAccommodation Management 5th Sem. Notes by Kirti PuriAmit MondalNo ratings yet

- Leukogram Patterns - EClinpathDocument6 pagesLeukogram Patterns - EClinpathCarlos YongNo ratings yet

- Faulty Radiographs PDFDocument2 pagesFaulty Radiographs PDFDougNo ratings yet

- FS13 PolycythemiaVera FactSheetDocument7 pagesFS13 PolycythemiaVera FactSheetMala 'emyu' UmarNo ratings yet

- Pediatric DosaPediatric Dosages Based On Body Weightges Based On Body WeightDocument7 pagesPediatric DosaPediatric Dosages Based On Body Weightges Based On Body WeightdjbhetaNo ratings yet

- Iv Infusion Pumps: PurposeDocument4 pagesIv Infusion Pumps: PurposegovindasamyNo ratings yet

- Jurnal Kecemasan Pre Operasi 5 InggrisDocument8 pagesJurnal Kecemasan Pre Operasi 5 InggrisExtensi 2 STIKes MKNo ratings yet

- 8699 36053 1 PBDocument7 pages8699 36053 1 PBPatrick RamosNo ratings yet

- Ineffective Breathing PatternDocument7 pagesIneffective Breathing PatternJanmae JivNo ratings yet

- HT EmergencyDocument24 pagesHT EmergencykunayahNo ratings yet

- 4 Brochure Digora Optime Eng LowDocument12 pages4 Brochure Digora Optime Eng LowabduolNo ratings yet

- Skala Klepto PDFDocument2 pagesSkala Klepto PDFdefani ismiriamNo ratings yet

- Multipel Vulnus IncisivumDocument11 pagesMultipel Vulnus IncisivumchiciNo ratings yet