Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Neonatal Conjunctivitis PDF

Neonatal Conjunctivitis PDF

Uploaded by

Eskanita Anggun ROriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Neonatal Conjunctivitis PDF

Neonatal Conjunctivitis PDF

Uploaded by

Eskanita Anggun RCopyright:

Available Formats

Malaysian Family Physician 2008; Volume 3, Number 2

ISSN: 1985-207X (print), 1985-2274 (electronic)

Academy of Family Physicians of Malaysia

Online version: http://www.ejournal.afpm.org.my/

Review Article

NEONATAL CONJUNCTIVITIS A REVIEW

PS Mallika1, MS; T Asok2, MMed; Faisal HA2, MS; S Aziz2, MS; AK Tan1, MD; G Intan2, MS.

1Department

of Ophthalmology, Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, University Malaysia Sarawak, Kuching, Sarawak,

Malaysia (Mallika Premsenthil)

2Department of Ophthalmology, Sarawak General Hospital, Kuching, Sarawak, Malaysia (Asokumaran Thanaraj, Humayun Akter

Faisal, Mohamad Aziz Salowi, Tan Aik Kah, Intan Gudom)

Address for correspondence: Dr. Mallika Premsenthil, Lecturer, Ophthalmology unit, Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, University

Malaysia Sarawak, Lot 77, Sekysen 22 Kuching Town Land District, Jalan Tun Ahmad Zaidi Adruce, 93150 Kuching, Sarawak, Malaysia. Tel:

+6082-416550, Fax: + 6082-422564, Email: pmallika@fmhs.unimas.my

Conflict of interest: None

ABSTRACT

Ophthalmia neonatorum remains a significant cause of ocular morbidity, blindness and even death in underdeveloped countries. The

organisms causing ophthalmia neonatorum are acquired mainly from the mothers birth canal during delivery and a small percentage of

cases are acquired by other ways. Chlamydia and Neisseria are the most common pathogens responsible for the perinatal infection.

Fortunately in most cases, laboratory studies can identify the causative organism and unlike other form of conjunctivitis, this perinatal

ocular infection has to be treated with systemic antibiotics to prevent systemic colonization of the organism. Routine prophylaxis with 1%

silver nitrate solution (crds method) has been discontinued in many developed nations for the fear of development of chemical conjunctivitis.

Key words: Crds Prophylaxis; Neonatal Conjunctivitis; Ophthalmia Neonatorum; Sexually Transmitted Diseases.

Mallika PS, Asok T, Aziz S, Faisal HA, Tan AK, Intan G. Neonatal conjunctivitis a review. Malaysian Family Physician. 2008;3(2):77-81

trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoea.7 Apart from bacteria,

herpes viruses can also cause neonatal conjunctivitis.

INTRODUCTION

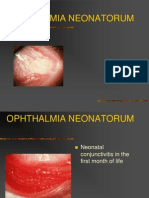

Neonatal conjunctivitis is often known as ophthalmia

neonatorum (Latin name). It is defined as conjunctivitis

occurring in a newborn during the first month of life with clinical

signs of erythema and oedema of the eyelids and the palpebral

conjunctivae, purulent eye discharge with one or more

polymorph nuclear per oil immersion field on a Gram stained

conjunctival smear.1 Originally described in 1750, it is one of

the most common infections occurring in the first month of

life.2

Ophthalmia neonatorum leads to blindness in approximately

10,000 babies annually worldwide.3 The major causes of

Ophthalmia neonatorum are, in decreasing order, chemical

inflammation, bacterial infection and viral infection. The

majority of infectious neonatal conjunctivitis are due to

bacteria.4 The bacterial causes include sexually transmitted

diseases agents (Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria

gonorrhoea), microorganisms from the skin (Staphylococcus

aureus) and the mothers gastrointestinal tract (Pseudomonas

sp).5 The inflammation usually resolves spontaneously within

a few days. Therefore, simple Gram stain and routine bacterial

culture are often the only investigations that are required in

most cases. 6 Although simple investigation suffices, treatment

has to be adequate because systemic complication and severe

visual loss can occur in infection particularly with Chlamydia

The organisms causing neonatal conjunctivitis are usually

acquired from the infected birth canal of the mother, though

some may acquire the infection from their immediate

surroundings.8 The predisposing factors, which can increase

the chance of the newborn acquiring neonatal conjunctivitis,

include increase shedding of these organisms in the vaginal

tract of the mother during the last trimester, premature rupture

of membranes and prolonged labor. Neonatal conjunctivitis

following caesarean section could be due to intrauterine

chlamydial infection as the result of early rupture of the

membranes8 or trans-placental or transmembrane transfer of

these organisms.9

The epidemiology of Ophthalmia Neonatorum has changed

following the prophylactic use of 1% silver nitrate solution

(Crd method); there was a marked reduction in the incidence

of ophthalmia in the United States, Europe, and the United

Kingdom following the widespread application of the Crd

prophylaxis.10 However, the role of silver nitrate prophylaxis

is only to prevent ophthalmia due to gonococcal infections; it

is not effective against Chlamydia. Silver nitrate prophylaxis

is not used currently due to the ineffectiveness in preventing

chlamydial infection and the tendency to cause chemical

conjunctivitis. This method of prophylaxis has been replaced

by the use of erythromycin or tetracycline ointment.11

77

AFPM J Vol 3 No 2.pmd

77

11/04/08, 2:06 PM

Malaysian Family Physician 2008; Volume 3, Number 2

ISSN: 1985-207X (print), 1985-2274 (electronic)

Academy of Family Physicians of Malaysia

Online version: http://www.ejournal.afpm.org.my/

EPIDEMIOLOGY

Ophthalmia neonatorum is a worldwide problem. The

pathogens responsible for causing the infection vary

geographically due to the differences in the prevalence of

maternal infection and the prophylactic use of antibiotics and

silver nitrate solution.2 In the developed world, Chlamydia has

been reported as the most common infectious agent

responsible for ophthalmia compared to gonococcus. However

in developing nations, both chlamydial and gonococcal

infections are prevalent. In Malaysia the incidence is

significantly high due to lack of routine prophylactic measures

and due to emergence of pencillinase-producing N.

gonorrhoea (PPNG) strains. The actual incidence is unknown

due to under-reporting. A study on gonococcal ophthalmia

neonatorum in the state of Kelantan has shown an increase

in the percentage of cases infected with penicillin resistant

strains of N. gonorrhoea from 6.4% to 25.9%.12 Lockie P et al

13 in their retrospective study involving 80 cases reported 7.5%

due to PPNG. The Pencillinase-producing strains are believed

to originate from South-East Asian region namely from

Bangkok where 48.9% of strains of N. gonorrhoea isolated

were due to PPNG.14

The prevalence of ophthalmia due to gonococcal infection is

reported to be 0.04 per 1000 live births in Belgium and

Netherlands, and 0.3 per 1000 live births in the United

States.15,16 At the moment, Chlamydia trachomatis is the most

frequent sexually transmitted pathogen in the developed

nations with prevalence of 5 to 60 per 1000 live births in the

United States, 4 per1000 live births in the United Kingdom

and 40 per 100 live births in Belgium; whereas the prevalence

of gonorrhoea among antenatal attenders in the African

countries ranges from 4% to 15 %.17 Approximately 25% to

50% of infants exposed to Chlamydia trachomatis and

Neisseria gonorrhoea develop neonatal conjunctivitis, without

prophylaxis.18

infections with Chlamydia in females are asymptomatic. Hence

it is often labeled as silent epidemic.21 The Center for Disease

Prevention and Control (CDC) estimates 3 million cases of

chlamydial infections occur per year. It is more prevalent than

gonococcal infection and approximately four to six times as

common as herpes virus infection.22

Although gonococcus is the second commonest organism

responsible for ophthalmia neonatorum, it is the most virulent

infectious agent for neonatal conjunctivitis. It was previously

the commonest cause of blindness within the first year of life,

necessitating the use of prophylaxis at birth. Gonococcal

ophthalmia neonatorum had been eradicated in the United

States in the 1950s. However, it has now resurfaced following

the increasing incidence of adult gonococcal infections and

the development of antimicrobial resistance.23

The other microbial causes of ophthalmia include

Staphylococcus aureus, Streptococcus pneumoniae,

Haemophilus influenzae, Escherichia coli, Klebsiella sp and

Pseudomonas aeruginosa.24,25

CLINICAL FEATURES

The genital serovars type D-K of Chlamydia trachomatis

causes neonatal conjunctivitis. It has a later onset than

gonococcal conjunctivitis. The incubation period is 5-14 days

and the colonization of the eye after birth does not always

result in infection. Almost 40% of the infected neonates develop

watery conjunctivitis which becomes more copious and

purulent later. Most of the cases are mild and self-limited, but

occasionally may be severe with eyelid swelling, chemosis,

papillary reaction, pseudo-membrane, peripheral pannus and

corneal involvement. If left untreated, 10-20% of the cases

will develop infantile pneumonia. Other extra ocular

involvement of Chlamydia includes nasopharyngeal, rectal and

vaginal colonization and other form of diseases such as infant

pneumonia syndrome.26

ETIOLOGY

Ophthalmia neonatorum can be divided into aseptic and septic

types.10 The aseptic type (chemical conjunctivitis) is generally

secondary to the instillation of silver nitrate drops for ocular

prophylaxis. Septic neonatal conjunctivitis is mainly caused

by bacterial and viral infections. Chlamydia trachomatis and

Neisseria gonorrhoea the two sexually transmitted agents are

associated with systemic complications and severe visual loss

if left untreated.19,20

Chlamydia trachomatis is the most common cause of

ophthalmia neonatorum in the developed countries because

of higher prevalence of Chlamydia as sexually transmitted

disease. This is due to the fact that 60% to 80% of genital

Gonococcal conjunctivitis is more severe than chlamydial

conjunctivitis. The incubation period is 2-5 days. However, it

can occur earlier in cases of premature rupture of membranes.

It is usually bilateral. The conjunctivitis is characterized by

severe hyper-acute purulent discharge, eyelid edema and

chemosis. Gonococci have the capacity to penetrate intact

corneal epithelium, leading to corneal epithelial edema and

corneal ulceration, which can progress to corneal perforation

and endophthalmitis if unrecognized. Hence in all cases of

neonatal conjunctivitis, the infant has to be screened for

gonococci to prevent these serious consequences.

Gonococcal infection of the newborn can also give rise to

systemic complications like stomatitis, arthritis, rhinitis,

septicemia and meningitis.27

78

AFPM J Vol 3 No 2.pmd

78

11/04/08, 2:06 PM

Malaysian Family Physician 2008; Volume 3, Number 2

ISSN: 1985-207X (print), 1985-2274 (electronic)

Academy of Family Physicians of Malaysia

Online version: http://www.ejournal.afpm.org.my/

Herpes simplex keratoconjunctivitis in an infant usually

presents with generalized herpes infection. Vesicles around

the eye and corneal involvement are also common.28 Chemical

conjunctivitis usually occurs within 24 hours of instillation of

silver nitrate solution and resolves spontaneously within a few

days. It can present with lid swelling associated with redness

of the eyes, rarely with lacrimal stenosis. Ophthalmia

Neonatorum due to other microbial causes usually run a milder

course without corneal and systemic involvement.

all these agents are considered effective only for gonococcal

ophthalmia, and found to be ineffective as prophylactic

treatment against chlamydial conjunctivitis.37 Bell et al38 found

no significant difference in the efficacy of silver nitrate, topical

erythromycin and no prophylaxis in preventing ophthalmia

neonatorum. Instead of prophylaxis, the authors concluded

that prenatal recognition and prompt treatment may prevent

the development of the disease.

TREATMENT

LABORATORY DIAGNOSIS

Ophthalmia neonatorum is essentially a clinical diagnosis

made by observation of signs and symptoms. The clinical

differentiation between various types of neonatal conjunctivitis

can be difficult.29,30 Hence lab diagnosis is of paramount

importance in establishing the correct diagnosis and initiating

the best treatment. Conjunctival scrapings for Gram stain and

Giemsa stain should be obtained from the palpebral

conjunctiva of all the infants with neonatal conjunctivitis. The

presence of intracellular gram negative diplococci (IGND) has

a high sensitivity and specificity and predictive value.31 Blood

agar, chocolate agar and/or Thayer-Martin media can be used

to isolate Neisseria gonorrhoea and other bacteria.

Chlamydia trachomatis can be isolated by the presence of

intracytoplasmic inclusion bodies in the Giemsa stain in 6080% of all infants. Conjunctival swab, smeared on to a

microscopic slide and stained with Chlamydia trachomatis

specific fluorescent monoclonal antibody (direct

immunofluorescence test) often shows the presence of an

impressively large number of punctate, fluorescing chlamydial

elementary bodies, resembling star-spangled sky at night.32

This antigen detection test is still considered the gold standard

for the diagnosis of chlamydial infections.33 Polymerase chain

reaction (PCR) analysis for diagnosing chlamydial

conjunctivitis has an advantage of early diagnosis and higher

specificity compared to McCoy cell culture. 34 The other

laboratory studies for diagnosing chlamydial infections include

Micro immunofluorescence assay (MIF) for detection of

Chlamydia trachomatis IgG and IgM antibodies and Elisa tests.

PROPHYLAXIS

Crd introduced 2% silver nitrate as a prophylaxis treatment

method for conjunctivitis in the newborns in Leipzig in 1881.35

The widespread use of silver nitrate prophylaxis was

associated with a drastic decline in the incidence of

gonococcal ophthalmia throughout Europe and the United

States. However, silver nitrate is toxic and for many years has

been recognised to be a common cause of chemical

conjunctivitis.36 Currently, topical erythromycin and tetracycline

are also used as alternatives for ocular prophylaxis.11 However,

Ophthalmia neonatorum is an ocular emergency so all infants

with neonatal conjunctivitis should be admitted. Specific

treatment modalities are available for different types of

neonatal conjunctivitis and treatment should be based on

clinical picture and laboratory diagnosis (Gram stain & Giemsa

stain). It is important to treat the infants with systemic rather

than topical drugs to prevent systemic dissemination of the

organism. As the causative organism is sexually transmitted,

it is vital to treat the mother and her sexual partner(s).

Current WHO guideline for the management of sexually

transmitted infections recommends that all cases of ophthalmia

neonatorum be treated for both N. gonorrhoea and C.

trachomatis39). The co-infection rates are estimated to be

around 2%.39

Ophthalmia neonatorum due to C. trachomatis

WHO and American Academy of Pediatrics recommendation

include oral erythromycin syrup, 50 mg/kg/day, in 4 divided

doses for 14 days.40 Topical erythromycin or tetracycline can

be used as an adjunct therapy. The advantages of oral

erythromycin include eradication of the nasopharyngeal

carriers, treatment of associated pneumonitis and also being

more effective than topical in preventing relapse of

conjunctivitis. 2 Infected partners should receive oral

doxycycline 100 mg twice daily for 7 days or azithromycin 1 g

orally as a single dose.39

Ophthalmia neonatorum due to N. gonorrhoea

Treatment of gonococcal conjunctivitis consists of Intravenous

Penicillin G 100,000 Units /kg/day for 1 week. N. gonorrhoea

isolates are resistant to penicillin in many urban areas in USA.

Across Africa, rates of pencillinase-producing N. gonorrhoea

range from 18 to 57% and many other parts of world (50% to

60%).31,15 Hence a third-generation cephalosporin drug should

be used for 7 days in areas where pencillinase producing

strains are endemic. A single dose of ceftriaxone 50 mg/kg as

s single dose (maximum 125 mg) is highly effective and

recommended by WHO guidelines.41,42 Alternative medications

include spectinomycin 25 mg/kg (maximum 75 mg) as a single

IM dose and kanamycin 25 mg/kg (maximum 75 mg). 43

Infected mother should also be treated with single dose of

ceftriaxone (25-50 mg/kg). The infants eye should be

79

AFPM J Vol 3 No 2.pmd

79

11/04/08, 2:06 PM

Malaysian Family Physician 2008; Volume 3, Number 2

ISSN: 1985-207X (print), 1985-2274 (electronic)

Academy of Family Physicians of Malaysia

Online version: http://www.ejournal.afpm.org.my/

frequently irrigated with normal saline to eliminate the

discharge.

Ophthalmia neonatorum due to Herpes simplex virus

Neonates suspected of conjunctivitis due to herpes simplex

should be treated with low dose systemic acyclovir (30mg/kg/

day IV divided tid) or vidarabine (30 mg /kg/day in divided

doses IV) for at least 2 weeks44 to prevent dissemination of

infection. Topical treatment may be with vidarabine ointment

or trifluridine eye drops.

RECOMMENDATIONS AND CONCLUSION

Awareness of the perinatal implications and routine screening

for Chlamydia in pregnant women will provide safer health

care for the mother and her baby. Treatment of any maternal

infection prior to delivery can help reduce the burden of this

disease, and also help to decrease the incidence of childhood

blindness not only in developing nations but also in developed

countries.

References

1.

Fransen L, Klauss V. Neonatal ophthalmia in the developing

world. Epidemiology, etiology, management and control. Int

Ophthalmol. 1988;11(3):189-96

2. Scott R Lambert, Conjunctivitis of the newborn (Ophthalmia

Neonatorum). David Taylor & Creig S Hoyt. Pediatric

Ophthalmology and Strabismus, Philadelphia, Elsevers

Saunders, 2005, 146-8.

3. Isenberg S J, Apt L, Wood M. The influence of perinatal infective

factors on ophthalmia neonatorum. J Pediatr Ophthalmol

Strabismus. 1996;33(3):185-8

4. Molgaard TL, Nielsen PB, Kaern J. A study of the incidence of

neonatal conjunctivitis and of its bacterial causes including

Chlamydia trachomatis. Clinical examination, culture and

cytology of tear fluid. Acta Ophthalmol. 1984;62(3):461-71

5. Akera C, Ro S. Medical concerns in the neonatal period. Clinics

in Family Practice. 2003;5(2):265-92

6. Prentice MJ, Hutchinson GR, Taylor-Robinson D. A

microbiological study of neonatal conjunctivae and conjunctivitis.

Br J Ophthalmol. 1997;61(9):601-7

7. Barry WC, Teare EL, Uttley AHC, et al. Chlamydia trachomatis

as a cause of neonatal conjunctivitis. Arch Dis Child.

1986;61(8):797-9

8. Mohile M, Deorari Ashok K, Satpathy G, et al. Microbiological

study of neonatal conjunctivitis with special reference to

Chlamydia trachomatis. Indian J Ophthalmol.

2002;50(4):295-9

9. Shariat H, Young M, Abedin M. An interesting case presentation:

a possible new route for perinatal acquisition of Chlamydia. J

Perinatology. 1992;12(3):300-2

10. Schaller UC, Klauss V. Is Credes prophylaxis for ophthalmia

neonatorum still valid? Bull World Health Organ.

2001;79(3):262-6

11. Laga M, Plummer FA, Piot P, et al. Prophylaxis of gonococcal

and Chlamydia ophthalmia neonatorum. N Eng J Med.

1988;318(11):653-7

12. Gururaj AK, Ariffin WA, Vijayakumari S, Reddy TN. Changing

trends in the epidemiology and management of gonococcal

ophthalmia neonatorum. Singapore Med J. 1992;33(3):279-81

13. Lockie P, Leong LK, Louis A. Penicillinase-producing Neisseria

gonorrhoea as a cause of neonatal and adult ophthalmia. Aust

N Z J Ophthalmol. 1986;14(1):49-53

14. Panikabutra K, Ariyarit C, Chitwarakom A. Cefatoxime in the

treatment of gonorrhoea caused by PPNG and non-PPNG. J

Med Assoc Thai. 1982;65(5):271-6

15. Klauss V, Schwartz EC. Other conditions of the outer eye. In:

Johnson GJ, Minassian DC, Weale R, eds. The epidemiology

of eye disease. London, Chapman & Hall, 1998.

16. Johnson D, McKenna H. Bacteria in ophthalmia neonatorum.

Pathology. 1975;7(3):199-201.

17. Meheus A, Piot P. Provision of services for sexually transmitted

diseases in developing countries. In: Oriel JD, Harris JRW, ed.

Recent advances in sexually transmitted diseases. London:

Churchill Livingstone, 1986:261-71.

18. Laga M, Plummer F, Nsanze H, et al. Epidemiology of

ophthalmia neonatorum in Kenya. Lancet. 1986;2:1145-8

19. Darvielle T. Chlamydia trachomatis infections in neonates and

young children. Semin Pediatr Infect Dis. 2005;6(4):235-44

20. Chandler JW, Alexander ER, Pfiffer TA, et al. Ophthalmia

neonatorum associated with maternal chlamydial infection.

Trans Sect Ophthalmo Am Acad Ophthalmol Otolaryngo.

1997;83(2):302-8

21. Walsh C, Anderson LA, Irwin K. Journal of Womens Health &

Gender- Based Medicine. 2000;9(4):339-43.

22. James J. Champoux, Lawrence Corey, Frederick C. Neidhardt,

et al. Chlamydia: John C. Sherris. Medical Microbiology.United

States of America.Prentice-Hall International Inc 1990, 469-77.

23. Snowe RJ, Wilfert CM. Epidemic reappearance of Gonococcal

ophthalmia neonatorum. Pediatrics. 1973;51(1):110-4

24. Yetman R, Coody D. Conjunctivitis: A practice guideline. J

Pediatric Health Care. 1997;11(5):238-44

25. Goldbloom RB. Prophylaxis for gonococcal and chlamydial

ophthalmia neonatorum. In: Canadian Task Force on the

Periodic Health Examination. Canadian Guide to Clinical

Preventive Health Care. Ottawa: Health Canada 1994; 168-75

26. Beem MO, Saxon EM. Respiratory tract colonization and a

distinctive pneumonia syndrome in infants infected with

chlamydia trachomatis. N Engl J Med. 1997; 296(6):306-10

27. Bradford WL, Kelly HW. Gonococci meningitis in a newborn

infant, with review of the literature. Am J Dis Child. 1933;

46:543-9

28. Nelson LB: Disorders of the conjunctiva. In: Harleys Pediatric

Ophthalmology. WB Saunders Co; 1998:202-14

29. Gigliotti, Williams WT, Hayden FG, et al. Etiology of acute

conjunctivitis in children. J Pediatr. 1981;98(4):531-6

30. Leibowitz HW, Pratt MV, Flagstad IJ, et al. Human conjunctivitis.

I. Diagnostic evaluation. Arch Ophthalmol. 1976;94(10):1747-9

31. Fransen L, Nsanze H, Klauss V, et al. Ophthalmia neonatorum

in Nairobi, Kenya: The roles of Neisseria gonorrhoea and

Chlamydia trachomatis. J Infect Dis. 1986;153(5):862-9

32. Chlamydial neonatal conjunctivitis and pneumonia 2002.

Accessed on 20 May 2007 at www.chlamydiae.com/restricted/

docs/infections/ophth_neonat.asp

33. Ridway GL, Taylor-Robinson D. Current problems in

microbiology chlamydial infections: which laboratory test? J Clin

Pathol. 1991;44(1):1-5

80

AFPM J Vol 3 No 2.pmd

80

11/04/08, 2:06 PM

Malaysian Family Physician 2008; Volume 3, Number 2

ISSN: 1985-207X (print), 1985-2274 (electronic)

Academy of Family Physicians of Malaysia

Online version: http://www.ejournal.afpm.org.my/

34. Talley AR, Garcia-Ferrer KF, Laycock KA, et al. Comparative

diagnosis of neonatal chlamydial conjunctivitis by polymerase

chain reaction and McCoy cell culture. Am J Ophthalmol.

1994;117(1):50-7

35. Crd CSF. Reports from the obstetrical clinic in Leipzig:

prevention of the eye inflammation in the newborn. Am J Dis

Child. 1971;121(1):3-4

36. Nishida H, Resenberg HM. Silver nitrate ophthalmic solution

and chemical conjunctivitis. Pediatrics. 1975;56(3):368-73

37. Oriel JD. Ophthalmia neonatorum: relative efficacy of current

prophylactic practices and treatment. J Antimicrob Chemother.

1984;14(3):209-20

38. Bell TA, Grayson JT, Krohn MA, et al. Randomized trial of silver

nitrate, erythromycin, and no eye prophylaxis for the prevention

of conjunctivitis among newborn not at risk for gonococcal

ophthalmitis. Pediatrics. 1993;92(6):755-60

39. Guidelines for the management of sexually transmitted

infections 2003. Accessed on 15 Aug 2007 at http://www.who.int/

reproductive-health/publicationa/rhs_01_01_mngt_stis/

guidelines_mngt_stis.pdf

40. AAP, AAOP, Red Book: 2003 Report of the committee on

Infectious Diseases, 26th ed. ELK Grove Village, IL, 2003.

41. Haase Da, Nash Ra, Nsanze H, et al. Single-dose ceftriaxone

therapy of gonococcal ophthalmia neonatorum. Sex Transm

Dis. 1986;13(1):53-55

42. Hoosen AA, Kharsany AB, Ison CA. Single low-dose ceftriaxone

for the treatment of gonococcal ophthalmia implications for

the national programme for the syndromic management of

sexually transmitted diseases. S Afr Med J. 2002;92(3):238-40

43. Fransen L, Nsanze H, DCosta L, et al. Single dose kanamycin

therapy of gonococcal ophthalmia neonatorum. Lancet.

1984;2:1234-7

44. Whittey R, Arwin A, Prober C, et al. A controlled trial comparing

vidarabine with acyclovir in neonatal herpes simplex virus

infection. N Engl J Med. 1991;324(7):444-9

Can star fruits kill?

Apparently yes, if you have prior kidney problem. Recently newspaper reported a 66-year-old

Malaysian Chinese who slipped into coma after taking star fruit in China. This problem is noted

only among patients with kidney failure. Star fruit (Averrhoa carambola) has been noted to

cause convulsions, hiccups, or death in uremic patients in many case reports. The exact

constituent causing these effect remains uncertain but oxalate is a prime suspect. Renal patients

should be advised to avoid star fruits.

Here are The Star news reports:

1.

Sunday May 18, 2008. Of star fruits and kidneys. http://thestar.com.my/health/

story.asp?file=/2008/5/18/health/21254246&sec=health

2.

Monday May 12, 2008. Star fruit victim still in coma. http://thestar.com.my/news/

story.asp?file=/2008/5/12/nation/21221945&sec=nation

Read more about this in PubMed (www.pubmed.gov) by typing star fruit neurotoxin (without

quotes) in the search box.

81

AFPM J Vol 3 No 2.pmd

81

11/04/08, 2:06 PM

You might also like

- All TomorrowsDocument111 pagesAll Tomorrowshappyleet83% (6)

- Kiss Me Hard Before YouDocument43 pagesKiss Me Hard Before YoukimNo ratings yet

- Microbial Keratitis Royal College of OphthalmologistDocument2 pagesMicrobial Keratitis Royal College of OphthalmologistmahadianNo ratings yet

- CB Final Project On K&N'sDocument35 pagesCB Final Project On K&N'sGOHAR GHAFFARNo ratings yet

- Home (/KB/) / Ophthalmia NeonatorumDocument8 pagesHome (/KB/) / Ophthalmia NeonatorumMohammed Shamiul ShahidNo ratings yet

- Ophthalmia NeonatorumDocument5 pagesOphthalmia NeonatorumTeresa MontesNo ratings yet

- Opthalmia UmDocument23 pagesOpthalmia Umnanu-jenuNo ratings yet

- Ophthalmia NeonatorumDocument5 pagesOphthalmia NeonatorumYhanna UlfianiNo ratings yet

- Antibiotics 07 00059 v2Document8 pagesAntibiotics 07 00059 v2alfiraNo ratings yet

- Omphalitis - Background, Pathophysiology, EpidemiologyDocument2 pagesOmphalitis - Background, Pathophysiology, EpidemiologykartikaNo ratings yet

- Ophthalmia NeonatorumDocument5 pagesOphthalmia NeonatorumDelphy Varghese100% (1)

- Toxoplasmosis AaoDocument28 pagesToxoplasmosis AaoUNHAS OphthalmologyNo ratings yet

- 308-Article Text-623-1-10-20161213Document3 pages308-Article Text-623-1-10-20161213fadiah maharaniNo ratings yet

- Daftar Pustaka Paper Oftalmia Neonatorum (Sudah Digabung) PDFDocument153 pagesDaftar Pustaka Paper Oftalmia Neonatorum (Sudah Digabung) PDFDewi Sartika100% (1)

- Ophthalmia NeonatorumDocument2 pagesOphthalmia NeonatorumconcozNo ratings yet

- ConjunctivitisDocument27 pagesConjunctivitisElukoti BhosleNo ratings yet

- Gonococcal ConjunctivitisDocument7 pagesGonococcal ConjunctivitishadijahNo ratings yet

- Varicella ZosterDocument10 pagesVaricella ZosterVu Nhat KhangNo ratings yet

- Toxoplasmosis: New Challenges For An Old DiseaseDocument5 pagesToxoplasmosis: New Challenges For An Old DiseaseNovi Alviani KamalNo ratings yet

- Trachoma Assignment On CHNDocument6 pagesTrachoma Assignment On CHNSovon SamantaNo ratings yet

- Chlamydia TrachomatisDocument7 pagesChlamydia TrachomatisDewi SetiawatiNo ratings yet

- Role of Family Physician in Management of Neonatal Conjunctivitis or Ophthalmia NeonatorumDocument20 pagesRole of Family Physician in Management of Neonatal Conjunctivitis or Ophthalmia NeonatorumAbdulla1999 AshrafNo ratings yet

- MK in PediDocument7 pagesMK in PedifikerteadelleNo ratings yet

- A Review On The Diagnosis and Treatment of SyphiliDocument8 pagesA Review On The Diagnosis and Treatment of SyphiliRaffaharianggaraNo ratings yet

- Ncbi - Nlm.nih - Gov-Pediatric PneumoniaDocument10 pagesNcbi - Nlm.nih - Gov-Pediatric Pneumoniako naythweNo ratings yet

- Saujanya Vadoothker, MD, Laura Andrews, MD, Bennie H. Jeng, MD, and Moran Roni Levin, MDDocument5 pagesSaujanya Vadoothker, MD, Laura Andrews, MD, Bennie H. Jeng, MD, and Moran Roni Levin, MDakmilNo ratings yet

- (Neonatal Conjunctivitis) Dr. Monica DhimanDocument20 pages(Neonatal Conjunctivitis) Dr. Monica DhimanMonicaNo ratings yet

- Infectious Endophthalmitis After: CataractDocument6 pagesInfectious Endophthalmitis After: CataractSurendar KesavanNo ratings yet

- ConjunctivitisDocument113 pagesConjunctivitisHussam AliNo ratings yet

- Congenital Cytomegalovirus-HistoryDocument6 pagesCongenital Cytomegalovirus-Historydossantoselaine212No ratings yet

- Acute Otitis Media - StatPearls (Internet) - Treasure Island (FL) StatPearls Publishing (2023)Document12 pagesAcute Otitis Media - StatPearls (Internet) - Treasure Island (FL) StatPearls Publishing (2023)Kezia KurniaNo ratings yet

- Ophthalmia NeonatorumDocument17 pagesOphthalmia NeonatorumIndranil DuttaNo ratings yet

- Management of Varicella Infection (Chickenpox) in Pregnancy: Sogc Clinical Practice GuidelineDocument6 pagesManagement of Varicella Infection (Chickenpox) in Pregnancy: Sogc Clinical Practice GuidelineAndi NugrohoNo ratings yet

- Journal 3Document6 pagesJournal 3riskab123No ratings yet

- Neonatal InfectionDocument18 pagesNeonatal InfectionchinchuNo ratings yet

- Neonatal InfectionDocument9 pagesNeonatal InfectionnishaNo ratings yet

- Selulitis PDFDocument5 pagesSelulitis PDFDhisa Zainita HabsariNo ratings yet

- Bacterial Sepsis Following PregnancyDocument21 pagesBacterial Sepsis Following PregnancyAhmad ShukriNo ratings yet

- Streptococcus Pyogenes ThesisDocument7 pagesStreptococcus Pyogenes Thesisclaudiashaharlington100% (2)

- Neonatal InfectionDocument19 pagesNeonatal InfectionLekshmi ManuNo ratings yet

- Gonococcal Infection in The Newborn - UpToDateDocument13 pagesGonococcal Infection in The Newborn - UpToDateCarina ColtuneacNo ratings yet

- SOGC Interim Guidance On Monkeypox Exposure For Pregnant PeopleDocument6 pagesSOGC Interim Guidance On Monkeypox Exposure For Pregnant PeopleariniNo ratings yet

- Ophthalmia NeonatorumDocument2 pagesOphthalmia NeonatorumjudssalangsangNo ratings yet

- Acs Skabies InternationalDocument3 pagesAcs Skabies InternationalChandra AnggaraNo ratings yet

- Infecciones Neonatale IDocument13 pagesInfecciones Neonatale IFidel RamonNo ratings yet

- MeaslesDocument4 pagesMeaslespauline erika buenaventuraNo ratings yet

- Rubella Virus 2Document4 pagesRubella Virus 2Michael W.No ratings yet

- Ophthalmia NeonatorumDocument2 pagesOphthalmia NeonatorumEjay BautistaNo ratings yet

- TRACHOMA and YAWS-1Document19 pagesTRACHOMA and YAWS-1Aadil AminNo ratings yet

- The Diagnosis and Management of Acute Bacterial Meningitis in Resource-Poor SettingsDocument12 pagesThe Diagnosis and Management of Acute Bacterial Meningitis in Resource-Poor SettingsGilson CavalcanteNo ratings yet

- Mumps Orchitis: M Masarani H Wazait M DinneenDocument3 pagesMumps Orchitis: M Masarani H Wazait M DinneenArisa RosyadaNo ratings yet

- Pneumonia UmumDocument9 pagesPneumonia Umumryan enotsNo ratings yet

- Case Study On Otitis Media. Group 2 BSN2A MCNP, Penablanca, CagayanDocument27 pagesCase Study On Otitis Media. Group 2 BSN2A MCNP, Penablanca, CagayanJean nicole GaribayNo ratings yet

- PD 3843Document8 pagesPD 3843chica_asNo ratings yet

- Pneumonia Pada AnakDocument36 pagesPneumonia Pada AnakSilvestri PurbaNo ratings yet

- Page Two 100509ToxoplasmaGondiinfectsMostSpeciesPage2Document2 pagesPage Two 100509ToxoplasmaGondiinfectsMostSpeciesPage2Ralph Charles Whitley, Sr.No ratings yet

- Ocular AllergyDocument23 pagesOcular AllergyCecilia TorresNo ratings yet

- TORCH Infection in Pregnant Women Ver September 2017 PDFDocument9 pagesTORCH Infection in Pregnant Women Ver September 2017 PDFRevina AmaliaNo ratings yet

- Entrelazamiento (Amir Aczel)Document8 pagesEntrelazamiento (Amir Aczel)Memento MoriNo ratings yet

- Jegan - SYNOPSIS FinalDocument25 pagesJegan - SYNOPSIS FinalpavinNo ratings yet

- Document 3Document3 pagesDocument 3theresia 102018040No ratings yet

- Rethinking Kraljic:: Towards A Purchasing Portfolio Model, Based On Mutual Buyer-Supplier DependenceDocument12 pagesRethinking Kraljic:: Towards A Purchasing Portfolio Model, Based On Mutual Buyer-Supplier DependencePrem Kumar Nambiar100% (2)

- Case Studies of Lower Respiratory Tract InfectionsDocument25 pagesCase Studies of Lower Respiratory Tract InfectionsMarianNo ratings yet

- Claro M. Recto - Tiaong's NotableDocument1 pageClaro M. Recto - Tiaong's NotableIris CastroNo ratings yet

- Virology The Study of VirusesDocument45 pagesVirology The Study of Virusesdawoodabdullah56100% (2)

- Atmospheric LayersDocument5 pagesAtmospheric LayersMary Jane Magat EspirituNo ratings yet

- Cost Accounting: Sixteenth Edition, Global EditionDocument34 pagesCost Accounting: Sixteenth Edition, Global EditionRania barabaNo ratings yet

- Schizophrenia Spectrum and Other Psychotic DisordersDocument8 pagesSchizophrenia Spectrum and Other Psychotic DisordersJR BetonioNo ratings yet

- My PastorDocument3 pagesMy PastorPastor Emma MukisaNo ratings yet

- Okatse Canyon: Mások Ezeket Keresték MégDocument1 pageOkatse Canyon: Mások Ezeket Keresték Mégtom kemNo ratings yet

- Unit 8 Lesson 1: Parts of The BodyDocument2 pagesUnit 8 Lesson 1: Parts of The BodyNguyễn PhúcNo ratings yet

- Katantra GrammarDocument2 pagesKatantra GrammarParitosh Das100% (2)

- Research Paper #6Document9 pagesResearch Paper #6Venice Claire CabiliNo ratings yet

- Electro QB BansalDocument20 pagesElectro QB BansalAnshul TiwariNo ratings yet

- Group Discussion 1Document15 pagesGroup Discussion 1salman10993No ratings yet

- Web Mining PPT 4121Document18 pagesWeb Mining PPT 4121Rishav SahayNo ratings yet

- LKPD IDocument5 pagesLKPD Isri rahayuppgNo ratings yet

- Gec 005 Module 3Document11 pagesGec 005 Module 3Nicolle AmoyanNo ratings yet

- ACTIVITY 3 - Historical CritismsDocument1 pageACTIVITY 3 - Historical CritismsKristine VirgulaNo ratings yet

- Pure Potency EnergyDocument6 pagesPure Potency EnergyLongicuspis100% (3)

- Project Management Plan Template ProcessDocument7 pagesProject Management Plan Template ProcessShanekia Lawson-WellsNo ratings yet

- Transfusion Reaction Algorithm V 2 FINAL 2016 11 02 PDFDocument1 pageTransfusion Reaction Algorithm V 2 FINAL 2016 11 02 PDFnohe992127No ratings yet

- Chemistry in Pictures - Turn Your Pennies Into "Gold" Rosemarie Pittenger,.Document3 pagesChemistry in Pictures - Turn Your Pennies Into "Gold" Rosemarie Pittenger,.Igor LukacevicNo ratings yet

- Pa1 W2 S3 R2Document7 pagesPa1 W2 S3 R2Bubble PopNo ratings yet

- MSDS Full1 PDFDocument92 pagesMSDS Full1 PDFSunthron SomchaiNo ratings yet

- ARAVIND - Docx PPPDocument3 pagesARAVIND - Docx PPPVijayaravind VijayaravindvNo ratings yet

- Past Tenses: Wiz NJ HN TH e - ( WH NJ HN TH - (Document1 pagePast Tenses: Wiz NJ HN TH e - ( WH NJ HN TH - (Sammy OushanNo ratings yet

- First Trimester TranslateDocument51 pagesFirst Trimester TranslateMuhammad Zakki Al FajriNo ratings yet