Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Digest of Supreme Court Cases Involving The Construction Indusrty

Digest of Supreme Court Cases Involving The Construction Indusrty

Uploaded by

Bobby Olavides SebastianOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Digest of Supreme Court Cases Involving The Construction Indusrty

Digest of Supreme Court Cases Involving The Construction Indusrty

Uploaded by

Bobby Olavides SebastianCopyright:

Available Formats

DIGEST OF SUPREME COURT CASES INVOLVING THE CONSTRUCTION INDUSTRY

Deipairne v. Court of Appeals

FULL TITLE: Ernesto Deiparine, Jr. v. Court of Appeals

CASE No.: G.R. No. 96643

DATE: April 23, 1993

PONENTE: CRUZ, J.

DOCTRINE: The difference between the two kinds of rescission in the Civil Code, to

wit: that in Art. 1191 and that in Art. 1385. Article 1191, unlike Article 1385, is not

predicated on economic prejudice to one of the parties but on breach of faith by one

of them that violates the reciprocity between them. The violation of reciprocity

between Deiparine and the Carungay spouses, to wit, the breach caused by

Deiparine's failure to follow the stipulated plans and specifications, has given the

Carungay spouses the right to rescind or cancel the contract.

DOCTRINE: Article 1725 contemplates a voluntary withdrawal by the owner

without fault on the part of the contractor, who is therefore entitled to indemnity, and

even damages, for the work he has already commenced.

FACTS: The spouses Cesario and Teresita Carungay entered into an agreement

with Ernesto Deiparine, Jr. on August 13, 19B2, for the construction of a three-story

dormitory in Cebu City, wherein the spouses shall pay Php 970,000.00 to the former,

who shall in turn erect the building according to strict specifications. In the course of

the construction, deviations from the plans and specifications were reported, thus

impairing the strength and safety of the building.

In view of this finding, the spouses Carungay filed complaint with the Regional Trial

Court of Cebu for the rescission of the construction contract and for damages.

Applying Art. 1191 of the Civil Code, the Trial Court ruled in their favour and

rescinded the agreement. The CA affirmed the RTCs ruling in toto.

In questioning the power of the trial court to grant rescission, Deiparine insists that

the construction agreement does not specify any compressive strength for the

structure nor does it require that the same be subjected to any kind of stress test.

Therefore, since he did not breach any of his covenants under the agreement, the

court erred in rescinding the contract.

[THIS MIGHT BE A BAD DECISION, see Gotesco v. Eugenio, G.R. No. 201167,

February 27, 2013] The SC here is of the opinion, I think, that under 1191, the

Spouses get their money back and Deipairne get nothing back, but that under 1385

rescision only allowed if the objects can be returned to each other, and that under

1725, Deipairne gets partial compensation and damages.

Art. 1191.

The power to rescind obligations is implied in reciprocal

ones, in case one of the obligors should not comply with what is incumbent

upon him.

The injured party may choose between the fulfillment and the rescission of

the obligation, with the payment of damages in either case. He may also

seek rescission, even after he has chosen fulfillment, if the latter should

become impossible.

The court shall decree the rescission claimed, unless there be just cause

authorizing the fixing of a period.

This is understood to be without prejudice to the rights of third persons who

have acquired the thing, in accordance with articles 1385 and 1388 and the

Mortgage Law.

Art. 1191 was the provision that the trial court and the respondent court correctly

applied because it relates to contracts involving reciprocal obligations like the

subject construction contract. The construction contract fails squarely under the

coverage of Article 1191 because it imposes upon Deiparine the obligation to build

the structure and upon the Carungays the obligation to pay for the project upon its

completion.

Article 1385, upon which Deiparine relies, deals with the rescission of the contracts

enumerated in Art. 1381, which do not include the construction agreement in

question.

Article 1191, unlike Article 1385, is not predicated on economic prejudice to one of

the parties but on breach of faith by one of them that violates the reciprocity between

them. The violation of reciprocity between Deiparine and the Carungay spouses, to

wit, the breach caused by Deiparine's failure to follow the stipulated plans and

specifications, has given the Carungay spouses the right to rescind or cancel the

contract.

Article 1725 cannot support the petitioner's position either, for this contemplates a

voluntary withdrawal by the owner without fault on the part of the contractor, who is

therefore entitled to indemnity, and even damages, for the work he has already

commenced. there is no such voluntary withdrawal in the case at bar. On the

contrary, the Carungays have been constrained to ask for judicial rescission

because of the petitioner's failure to comply with the terms and conditions of their

contract.

==oOo==

ISSUE: Does the trial court have the authority to order the rescission? YES

HELD: Art. 1191 reads, to wit:

The President of the COJCOLDS v. BTL Construction

1 | Page

DIGEST OF SUPREME COURT CASES INVOLVING THE CONSTRUCTION INDUSTRY

FULL TITLE: The President of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints v.

BTL Construction Corp.

CASE No.: G.R. No. 176439

DATE: 15 January 2014

PONENTE: Perlas-Bernabe, J.

DOCTRINE: Based on Art. 1724 of the Civil Code, added costs in contracts for a

stipulated price can only be allowed upon the: (a) written authority from the

developer or project owner ordering or allowing the written changes in work; and (b)

written agreement of parties with regard to the increase in price or cost due to the

change in work or design modification. Compliance with these two (2) requisites is a

condition precedent for recovery, and the absence of one or the other condition bars

the claim of additional costs.

DOCTRINE: In the construction industry, the 10% retention money is a portion of the

contract price automatically deducted from the contractors billings, as security for

the execution of corrective work if any becomes necessary. Retention money

should not be treated as a separate and distinct liability from the contract price.

DOCTRINE: In cases with counterclaims, when neither party was shown to have

acted in bad faith in pursuing their respective claims against each other, as when the

parties original claims were found to be partially meritorious, attorneys fees cannot

be recovered, pursuant to Art. 2208 of the Civil Code.

FACTS: COJCOLDS and BTL entered into a contract for the construction of the

formers meetinghouse facility in Medina, Misamis Oriental. However, due to bad

weather conditions, power failures, and revisions in the construction plans, among

others, the completion date was extended. Later, BTL informed COJCOLDS that it

suffered financial losses from another project and soon ceased its operations in the

Medina Project because of its lack of funds to advance the cost of labor necessary

to complete the said project, as well as the supervening increase in the prices of

materials and other items for construction. Consequently, COJCOLDS terminated its

contract with BTL and, thereafter, engaged the services of another contractor, Vigor

Construction (Vigor), to complete the Medina Project, using the retention money

specified in the contract in the amount of 10% thereof.

About 2 years later, BTL filed a complaint against COJCOLDS before the

Construction Industry Abritration Commission (CIAC) for the collection of the cost of

labor, materials, equipment, overhead expenses, lost profits and interests, the 10%

retention money stipulated in the contract and interest on said retention money,

actual damages, attorneys fees, moral and exemplary damages and costs of

arbitration.

For its part, COJCOLDS filed its answer with compulsory counterclaim, praying for

the award of liquidated damages in view of BTLs delay in completing the pending

project, reimbursement of the payments it directly made to BTLs suppliers as per

the latters request, cost overrun and attorneys fees.

The CIAC found COJCOLDS liable to BTL for 98% of the contract price, based on

the percentage of completion of the project, less previous payments, and for the cost

of additional works and attorneys fees. On the other hand, BTL was ordered to pay

COJCOLDS liquidated damages pursuant to the contract due to delay.

On appeal, the CA modified the CIACs ruling by requiring COJCOLDS to return the

10% retention money to BTL, in addition to the balance of the contract price. The

CA, however, deleted the award in favour of BTL for additional works, ruling that it

should properly deemed as part of the original works, considering that it was not

covered by any change order. In addition, the CA deleted the award for Attorneys

fees in favour of BTL as COJCOLDS was not in bad faith. Both parties filed their

respective MRs, which were both denied. Hence, this Petition for Review on

Certiorari.

ISSUES: (1) Whether or not COJCOLDS is liable for the "additional works"

performed by BTL that were not covered by an approved change order NO

(2) Whether or not BTL is entitled to the return of the Retention money, on top of the

balance of the Contract Price NO

(3) Is either party entitled to an award for Attorneys fees?

HELD: (1) Article 1724 of the Civil Code governs the recovery of additional costs in

contracts for a stipulated price (such as fixed lump-sum contracts), as well as the

increase in price for any additional work due to a subsequent change in the original

plans and specifications. Based on the same provision, such added costs can only

be allowed upon the: (a) written authority from the developer or project owner

ordering or allowing the written changes in work; and (b) written agreement of

parties with regard to the increase in price or cost due to the change in work or

design modification. Case law instructs that compliance with these two (2) requisites

is a condition precedent for recovery. The absence of one or the other condition thus

bars the claim of additional costs. Notably, neither the authority for the changes

made nor the additional price to be paid therefor may be proved by any evidence

other than the written authority and agreement as above-mentioned.

In this case, records reveal that there is neither a written authorization nor

agreement covering the additional price to be paid for the concrete retaining wall.

This confirms the CAs finding that the construction of the perimeter wall of the

Medina Project, which is included in the original plans and specifications for the

same, already subsumes the construction of the concrete retaining wall.43

Accordingly, COJCOLDS should not pay the amount claimed by BTL as additional

cost for the same.

(2) As to Retention Money - In H.L. Carlos Construction, Inc. v. Marina Properties

Corp. (466 Phil. 182, 2004) the Court had held that in the construction industry, the

10% retention money is a portion of the contract price automatically deducted from

2 | Page

DIGEST OF SUPREME COURT CASES INVOLVING THE CONSTRUCTION INDUSTRY

the contractors billings, as security for the execution of corrective work if any

becomes necessary. As such, the 10% retention money should not be treated as a

separate and distinct liability of COJCOLDS to BTL as it merely forms part of the

contract price. While COJCOLDS is bound to eventually return to BTL the retention

money, the said amount should be automatically deducted from BTLs outstanding

billings.

FULL TITLE:

CASE No.:

DATE:

PONENTE:

(3) The general rule is that attorneys fees cannot be recovered as part of damages

because of the policy that no premium should be placed on the right to litigate. They

are not to be awarded every time a party wins a suit. The power of the court to

award attorneys fees under Article 2208 of the Civil Code demands factual, legal,

and equitable justification. Even when a claimant is compelled to litigate with third

persons or to incur expenses to protect his rights, still attorneys fees may not be

awarded where no sufficient showing of bad faith could be reflected in a partys

persistence in a case other than an erroneous conviction of the righteousness of his

cause. In this case, the Court observes that neither party was shown to have acted

in bad faith in pursuing their respective claims against each other. The existence of

bad faith is negated by the fact that the CIAC, the CA, and the Court have all found

the parties original claims to be partially meritorious. Thus, absent no cogent reason

to hold otherwise, the Court deems it inappropriate to award attorneys fees in favor

of either party. Finally, in view of their legitimate claims against each other, each

party should bear its own arbitration costs and costs of suit.

FACTS:

DOCTRINE:

ISSUE:

HELD:

[SHORT TITLE]

FULL TITLE:

CASE No.:

DATE:

PONENTE:

DOCTRINE:

FACTS:

==oOo==

[SHORT TITLE]

FULL TITLE:

CASE No.:

DATE:

PONENTE:

ISSUE:

HELD:

FACTS:

[SHORT TITLE]

FULL TITLE:

CASE No.:

DATE:

PONENTE:

ISSUE:

DOCTRINE:

HELD:

FACTS:

DOCTRINE:

ISSUE:

[SHORT TITLE]

HELD:

3 | Page

You might also like

- UK Visas & Immigration: Personal InformationDocument10 pagesUK Visas & Immigration: Personal InformationJovana CarrascoNo ratings yet

- Occupancy Permit Violation SourcesDocument6 pagesOccupancy Permit Violation SourcesBobby Olavides SebastianNo ratings yet

- Code of Ethics ComparisonDocument8 pagesCode of Ethics Comparisonsmith1282100% (1)

- Corpo Law Case Digest No. 50 51 52Document4 pagesCorpo Law Case Digest No. 50 51 52yetyetNo ratings yet

- Legal Forms1 - 161915-2008-Dela - Cruz - v. - Dimaano - JR DigestDocument1 pageLegal Forms1 - 161915-2008-Dela - Cruz - v. - Dimaano - JR DigestRene BalloNo ratings yet

- Transpo Codal SummaryDocument3 pagesTranspo Codal SummaryJosiah DavidNo ratings yet

- Torts Cases 2Document32 pagesTorts Cases 2Janice DulotanNo ratings yet

- 14 - Western Guaranty, Corp. v. Court of Appeals - GMSGDocument2 pages14 - Western Guaranty, Corp. v. Court of Appeals - GMSGGeorge Mitchell S. GuerreroNo ratings yet

- Chapter 11 TAXDocument10 pagesChapter 11 TAXnewa944No ratings yet

- Esio, Lawrence 4A (CivRev) .Document36 pagesEsio, Lawrence 4A (CivRev) .Lawrence EsioNo ratings yet

- Pci Vs NLRCDocument9 pagesPci Vs NLRCBryan Nartatez BautistaNo ratings yet

- Delos Reyes Vs CA AGENCYDocument8 pagesDelos Reyes Vs CA AGENCYEmma SchultzNo ratings yet

- Murillo, Paul Arman Succession-Quiz-August-25-2020Document2 pagesMurillo, Paul Arman Succession-Quiz-August-25-2020Paul Arman MurilloNo ratings yet

- Taxation Ii-Reviewer PDFDocument31 pagesTaxation Ii-Reviewer PDFMisc Ellaneous0% (1)

- Atiko Trans vs. PgaDocument2 pagesAtiko Trans vs. PgaKat MirandaNo ratings yet

- Ainiza Vs Spouses Padua (Digest)Document1 pageAiniza Vs Spouses Padua (Digest)fcnrrsNo ratings yet

- Cases For Agency - Atty. Prime RamosDocument60 pagesCases For Agency - Atty. Prime RamosRoxanne PeñaNo ratings yet

- Torts FinalsDocument55 pagesTorts FinalsCGNo ratings yet

- PHILAM Life v. PaternoDocument2 pagesPHILAM Life v. PaternoPatricia SulitNo ratings yet

- Fireman - S Fund Insurance Company and Firestone Tire and Rubber Company of The PhilippinesDocument3 pagesFireman - S Fund Insurance Company and Firestone Tire and Rubber Company of The PhilippinesWayneNoveraNo ratings yet

- TORTS - 36. Schmitz Transport and Brokerage Corp. v. Transport Venture, Inc.Document14 pagesTORTS - 36. Schmitz Transport and Brokerage Corp. v. Transport Venture, Inc.Mark Gabriel B. MarangaNo ratings yet

- Torts ReviewerDocument21 pagesTorts ReviewerJoannie JlaNo ratings yet

- Goya Inc VS Goya Employees UnionDocument7 pagesGoya Inc VS Goya Employees UnionChing GonzalesNo ratings yet

- Ingusan Vs Heirs of ReyesDocument11 pagesIngusan Vs Heirs of ReyesMark AnthonyNo ratings yet

- Labor Standards ReviewerDocument99 pagesLabor Standards ReviewerSamantha Lei Rivera Bernal-FranciaNo ratings yet

- Emma - Asian Design and Manufacturing Corp V CallejaDocument2 pagesEmma - Asian Design and Manufacturing Corp V CallejaEmma GuancoNo ratings yet

- Ong Lim Sing, Jr. vs. FEB Leasing & Finance CorporationDocument19 pagesOng Lim Sing, Jr. vs. FEB Leasing & Finance CorporationArya StarkNo ratings yet

- MGM Studios Inc vs. Grokster LTDDocument10 pagesMGM Studios Inc vs. Grokster LTDLai LingNo ratings yet

- 3) Tadeo-Matias Vs Republic of The Phil.Document30 pages3) Tadeo-Matias Vs Republic of The Phil.Elizabeth Jade D. CalaorNo ratings yet

- J. Bersamin TaxDocument14 pagesJ. Bersamin TaxJessica JungNo ratings yet

- Provisional Remedies - Codal - CoDocument22 pagesProvisional Remedies - Codal - CoAira Kristina AllasNo ratings yet

- San Beda College of Law: Contract of Transportation/ CarriageDocument43 pagesSan Beda College of Law: Contract of Transportation/ CarriageMae Jansen DoroneoNo ratings yet

- Transportation Law Case Digests and SynthesisDocument10 pagesTransportation Law Case Digests and SynthesisDessa ReyesNo ratings yet

- G.R. No. 149240 July 11, 2002 With Case DigestDocument7 pagesG.R. No. 149240 July 11, 2002 With Case Digestkick quiamNo ratings yet

- Security Bank V Great Wall CommercialDocument1 pageSecurity Bank V Great Wall CommercialCj GarciaNo ratings yet

- Full Text Evidence. Module 1 CasesDocument102 pagesFull Text Evidence. Module 1 CasesCarla CariagaNo ratings yet

- 5-Rizal Surety Vs Manila RailroadDocument3 pages5-Rizal Surety Vs Manila RailroadJoan Dela CruzNo ratings yet

- SIAO Finals Compilation PDFDocument184 pagesSIAO Finals Compilation PDFKendrick SiaoNo ratings yet

- Manahan v. Manahan, G.R. No. 38050, September 22, 1933 (58 Phil 448)Document3 pagesManahan v. Manahan, G.R. No. 38050, September 22, 1933 (58 Phil 448)ryanmeinNo ratings yet

- Coleongco Vs ClaparolsDocument2 pagesColeongco Vs ClaparolsMichael C. PayumoNo ratings yet

- Bar Questions For Agency Trust and PartnDocument4 pagesBar Questions For Agency Trust and PartnSahira Macaombao IbrahimNo ratings yet

- Transportation-Cases-36-55 Digested - Chestercaro - Oct12Document30 pagesTransportation-Cases-36-55 Digested - Chestercaro - Oct12Mai MomayNo ratings yet

- 04 San Juan Structural V CADocument29 pages04 San Juan Structural V CAeieipayadNo ratings yet

- 17 FGU Insurance vs. CA, G.R. No. 137775Document19 pages17 FGU Insurance vs. CA, G.R. No. 137775blessaraynesNo ratings yet

- Transportation Law 1994 Bar Questions by LubayDocument10 pagesTransportation Law 1994 Bar Questions by LubayAngelo CastilloNo ratings yet

- 8 - Catan V NLRCDocument6 pages8 - Catan V NLRCKar EnNo ratings yet

- Fgu VS GPDocument3 pagesFgu VS GPjoel ayonNo ratings yet

- Tri-C V MatutoDocument2 pagesTri-C V MatutoLouie SalazarNo ratings yet

- FGU Insurance Corporation vs. G.P. Sarmiento Trucking Corporation and Lambert ErolesDocument65 pagesFGU Insurance Corporation vs. G.P. Sarmiento Trucking Corporation and Lambert ErolesernestbenzdavilaNo ratings yet

- Transportation Law WILLIAMS V YANGCODocument4 pagesTransportation Law WILLIAMS V YANGCOGracia Sullano100% (1)

- Third Division: Notice NoticeDocument3 pagesThird Division: Notice NoticeervingabralagbonNo ratings yet

- 364 Lorenzo V GSISDocument2 pages364 Lorenzo V GSISNN DDLNo ratings yet

- 27 Felicilda v. Uy, G.R. No. 221241, Sept. 14, 2016 VILLAMORA 2ADocument2 pages27 Felicilda v. Uy, G.R. No. 221241, Sept. 14, 2016 VILLAMORA 2AMichelle VillamoraNo ratings yet

- Araneta V BaDocument2 pagesAraneta V BaVianca MiguelNo ratings yet

- Trademark-E.Y. Industrial Sales vs. Shien Dar Electricity and Machinery Co.Document6 pagesTrademark-E.Y. Industrial Sales vs. Shien Dar Electricity and Machinery Co.Tea AnnNo ratings yet

- Universal v. ResourcesDocument2 pagesUniversal v. ResourcesKalliah Cassandra CruzNo ratings yet

- September 3Document24 pagesSeptember 3Eisley SarzadillaNo ratings yet

- Partnership and Corporation by de LeonDocument2 pagesPartnership and Corporation by de LeonblahblahblueNo ratings yet

- CONUNDRUM: The Doctrine of Last Clear ChanceDocument48 pagesCONUNDRUM: The Doctrine of Last Clear ChanceCyndall J. Walking100% (1)

- Insurance Last CasesDocument6 pagesInsurance Last CasesADNo ratings yet

- 48 Pioneer Concrete V TodaroDocument2 pages48 Pioneer Concrete V TodaroKenzo RodisNo ratings yet

- Chung vs. UlandayDocument20 pagesChung vs. UlandayPia Christine BungubungNo ratings yet

- Digest Deiparine V CADocument3 pagesDigest Deiparine V CAKym HernandezNo ratings yet

- BSP Warning Advisory On Virtual CurrenciesDocument2 pagesBSP Warning Advisory On Virtual CurrenciesBobby Olavides SebastianNo ratings yet

- Film Financing and Television Programming - PhilippinesDocument20 pagesFilm Financing and Television Programming - PhilippinesBobby Olavides SebastianNo ratings yet

- BSP Circular No. 944-2017 (Guidelines For Virtual Currency (VC) Exchanges)Document6 pagesBSP Circular No. 944-2017 (Guidelines For Virtual Currency (VC) Exchanges)Bobby Olavides SebastianNo ratings yet

- SEC MSRD Request For Comments On The Updated Proposed Rules On Initial Coin OfferingDocument46 pagesSEC MSRD Request For Comments On The Updated Proposed Rules On Initial Coin OfferingBobby Olavides SebastianNo ratings yet

- SEC Advisory PluggleDocument3 pagesSEC Advisory PluggleBobby Olavides SebastianNo ratings yet

- SEC Advisory Secret2SuccessDocument3 pagesSEC Advisory Secret2SuccessBobby Olavides SebastianNo ratings yet

- SEC Advisory Re MiningDocument3 pagesSEC Advisory Re MiningBobby Olavides SebastianNo ratings yet

- SEC Advisory OnecashDocument2 pagesSEC Advisory OnecashBobby Olavides SebastianNo ratings yet

- SEC Advisory Public Participation in Initial Coin OfferingDocument2 pagesSEC Advisory Public Participation in Initial Coin OfferingBobby Olavides SebastianNo ratings yet

- SEC Advisory PHILIPPINE GLOBAL COINDocument2 pagesSEC Advisory PHILIPPINE GLOBAL COINBobby Olavides SebastianNo ratings yet

- SEC Advisory PhilcrowdDocument2 pagesSEC Advisory PhilcrowdBobby Olavides SebastianNo ratings yet

- Atc 12 RRDDocument5 pagesAtc 12 RRDBobby Olavides SebastianNo ratings yet

- UTPRAS Guidelines (HTTP://WWW - Tesda.gov - ph/About/TESDA/42)Document5 pagesUTPRAS Guidelines (HTTP://WWW - Tesda.gov - ph/About/TESDA/42)Bobby Olavides SebastianNo ratings yet

- Guidelines On VideoconferencingDocument23 pagesGuidelines On VideoconferencingBobby Olavides SebastianNo ratings yet

- Regulatory Framework For The Accreditation of Gaming SystemDocument8 pagesRegulatory Framework For The Accreditation of Gaming SystemBobby Olavides SebastianNo ratings yet

- PC Express Dealers Pricelist July 4 2020 PDFDocument2 pagesPC Express Dealers Pricelist July 4 2020 PDFBobby Olavides SebastianNo ratings yet

- SB 1564Document59 pagesSB 1564Bobby Olavides SebastianNo ratings yet

- TESDA - Program Registration Forms Land-BasedDocument26 pagesTESDA - Program Registration Forms Land-BasedBobby Olavides SebastianNo ratings yet

- RMC 66-03 (Taxability of PAL)Document4 pagesRMC 66-03 (Taxability of PAL)Bobby Olavides SebastianNo ratings yet

- All POGOs SPs - Compliance With The 60-40 Foreign Equity RequirementDocument1 pageAll POGOs SPs - Compliance With The 60-40 Foreign Equity RequirementBobby Olavides SebastianNo ratings yet

- Republic of The Philippines: Scale Projects Are Defined As Those Construction Projects That Are Intended For PurelyDocument12 pagesRepublic of The Philippines: Scale Projects Are Defined As Those Construction Projects That Are Intended For PurelyBobby Olavides SebastianNo ratings yet

- Cheaper Medicines Act of 2008Document28 pagesCheaper Medicines Act of 2008Bobby Olavides SebastianNo ratings yet

- RR No. 20-2020 PDFDocument2 pagesRR No. 20-2020 PDFBobby Olavides SebastianNo ratings yet

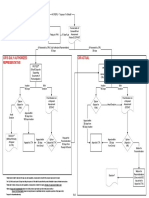

- Assessment Flow ChartDocument1 pageAssessment Flow ChartBobby Olavides SebastianNo ratings yet

- BIR Ruling 359-17Document5 pagesBIR Ruling 359-17Bobby Olavides SebastianNo ratings yet

- DOF-RO Form 91Document6 pagesDOF-RO Form 91Bobby Olavides SebastianNo ratings yet

- TIN Card As ID For Notarization PurposesDocument9 pagesTIN Card As ID For Notarization PurposesBobby Olavides SebastianNo ratings yet

- TWA 100818 Delisted IndividualDocument1 pageTWA 100818 Delisted IndividualBobby Olavides SebastianNo ratings yet

- 11 People Vs Bautista, G.R. No. 113547, Feb. 9, 1995Document3 pages11 People Vs Bautista, G.R. No. 113547, Feb. 9, 1995Perry YapNo ratings yet

- S2 Lecture 2 - The Bill of RightsDocument9 pagesS2 Lecture 2 - The Bill of RightsSamantha Joy Angeles0% (1)

- Carl M. Brown v. The Governor Baxter School For The Deaf, 960 F.2d 143, 1st Cir. (1992)Document2 pagesCarl M. Brown v. The Governor Baxter School For The Deaf, 960 F.2d 143, 1st Cir. (1992)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Afp v. CaDocument3 pagesAfp v. CaErikha AranetaNo ratings yet

- 9 - Philcomsat V SandiganbayanDocument5 pages9 - Philcomsat V SandiganbayanJohn YeungNo ratings yet

- 030 - Compounding A Non-Compoundable Offences - Judicial Pragmatism - Neither Activism Nor Absolutism (437-454) PDFDocument18 pages030 - Compounding A Non-Compoundable Offences - Judicial Pragmatism - Neither Activism Nor Absolutism (437-454) PDFKalyaniNo ratings yet

- UK Home Office: Ecaa3Document11 pagesUK Home Office: Ecaa3UK_HomeOfficeNo ratings yet

- Consti 1 Case ListDocument9 pagesConsti 1 Case ListTin PascuaNo ratings yet

- Nominal DamagesDocument16 pagesNominal DamagesCharlie PeinNo ratings yet

- Final Draft IPCDocument17 pagesFinal Draft IPCSachika VijNo ratings yet

- Savvy Criminals 1Document3 pagesSavvy Criminals 1Marie EginaNo ratings yet

- Microsoft WordDocument3 pagesMicrosoft Wordishuch24No ratings yet

- Export LicenseDocument3 pagesExport LicenseRoshaniNo ratings yet

- Safeguarding of Adults at Risk of Abuse and Neglect Policy V7 CM 004 March 2021Document13 pagesSafeguarding of Adults at Risk of Abuse and Neglect Policy V7 CM 004 March 2021dlukowskaNo ratings yet

- Eileen David vs. Glenda MarquezDocument2 pagesEileen David vs. Glenda MarquezAreeya ManalastasNo ratings yet

- R.C. Cooper CaseDocument8 pagesR.C. Cooper CaseGourav LohiaNo ratings yet

- Jurisprudence in Scotland Lecture NotesDocument36 pagesJurisprudence in Scotland Lecture NotesElenaNo ratings yet

- 45 MER INDUSTRIES, INC., Petitioner, vs. Insurance Co., Inc., RespondentDocument16 pages45 MER INDUSTRIES, INC., Petitioner, vs. Insurance Co., Inc., RespondentMirzi Olga Breech SilangNo ratings yet

- Interflow NDA Systech Products 2020Document3 pagesInterflow NDA Systech Products 2020Saad IqbalNo ratings yet

- Droit AdministratifDocument2 pagesDroit AdministratifRaja Sanmanbir Singh100% (3)

- Uttar Pradesh State Legal Services Authority: Final Draft OnDocument22 pagesUttar Pradesh State Legal Services Authority: Final Draft OnAnkur BhattNo ratings yet

- Obligation and Contract Art 1162 CasesDocument56 pagesObligation and Contract Art 1162 CasesMaricar BautistaNo ratings yet

- Rangos PolicialesDocument7 pagesRangos PolicialesFederico CampanaNo ratings yet

- Litton Mills, Inc. Vs CA (Case Digest)Document2 pagesLitton Mills, Inc. Vs CA (Case Digest)Kristine Lingayo100% (1)

- Ca2 ReviewerDocument5 pagesCa2 ReviewerRAIZZA MAE BARZANo ratings yet

- Department of Education Schools Division Office of Isabela: Republic of The Philippines Region 02 City of IlaganDocument2 pagesDepartment of Education Schools Division Office of Isabela: Republic of The Philippines Region 02 City of Ilaganmardee justoNo ratings yet

- Legal Pluralism in Theory and Practice: Analytical EssayDocument25 pagesLegal Pluralism in Theory and Practice: Analytical EssayintemperanteNo ratings yet

- Agency and Partnership BarbriDocument2 pagesAgency and Partnership BarbriDorimar MoralesNo ratings yet